1. Introduction

2.3 million women were diagnosed with breast cancer in 2022, and 670,000 deaths occur globally every year. Breast cancer is mostly affected by mutations in the BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2 genes. If a particular woman has a mutation in this gene, it can be cured by removing both breasts or by chemoprevention. To treat breast cancer, the strategies available are surgery to remove the breast, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. If the cancer cell is oestrogen receptor positive (ER) or progesterone receptor (PR), then it can be treated with endocrine therapy. But if the cancer is ER or PR-negative, then it can only be cured with chemotherapy if it is in the early stages. The above-mentioned treatments not only target the cancer cell itself but also kill normal cells [

1,

2,

3]. For the treatment of cancer, nanotechnology plays a major role. Due to their smaller size and charged surface, bio-compatibility nanoparticles are used to treat cancer.

The copper oxide nanoparticle has photoconductive and photothermal applications [

4]. It is used in power-saving batteries. Copper nanoparticles have a lot of applications in the healthcare industry. It has the ability to kill 99% of both grammeme-positive and grammeme-negative bacteria. It has the ability to induce the autophagy. [

5,

6]

MgO nanoparticles are the most promising candidate compared to other metal oxide nanoparticles. Because it has excellent optical, thermal, mechanical, and electrical properties. Its different shapes, such as platelets, flowers, stars, spheres, rods, and cubes, make these nanoparticles suitable for different applications. MgO nanoparticles are also used in the fields of tissue regeneration and wound healing.

A similar study was used with the copper oxide nanoparticle to inhibit autophagy in the Michigan Cancer Foundation- 7 (MCF-7) cell line by autophagosome formation. It can be confirmed with different tests, and a treated nanoparticle was observed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) [

7]. Like that, the magnesium-doped copper spinel ferrite superparamagnetic nanoparticles can be tested in the MCF-7 cell line with different concentrations under UV irradiation [

8]. In a recent research study, the magnesium oxide nanoparticle synthesized with

Saussurea costus was tested in the MCF-7 cell line. It shows the prominent cytotoxicity and efficient dye degradation of methylene blue dye [

8].

In this study, the copper and magnesium oxide nanoparticles were synthesized by the sol-gel method, and both nanoparticles were characterized by different methods: FTIR, SEM, and UV-visible spectrophotometer. The antimicrobial activity of copper and magnesium oxide was studied in grammeme-positive and grammeme-negative bacteria. Finally, the nanoparticles of copper and magnesium oxide were mixed in a 1:1 ratio, and then they were tested in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. The cytotoxicity of the nanoparticle mixer showed better activity.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Copper Oxide Nanoparticle

For the synthesis of copper oxide and magnesium oxide nanoparticle the copper sulphate pentahydrate act as a starting material. 0.1 M copper sulphate pentahydrate was weighted and dissolved in 100 ml of distilled water. Using magnetic stirrer to make a homogenous solution. 0.1 M of sodium hydroxide prepared separately. The sodium hydroxide solution was filled in the burette, it was added to drop wise into the copper sulphate solution. The entire process was kept at 80°C. stop the reaction once the blue colour solution was change into black colour and it was stand to settle at room temperature. It was sonicated to reduce the size of the nanoparticle and washed with methanol 3 times to remove the ironic contaminants. Then it was dried at 60°C and calcined at 400°C for 2 hrs. [

9,

10,

11,

12]

2.2. Synthesis of Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticle

Magnesium oxide nanoparticle was synthesized by sol-gel method. 0.1M sodium hydroxide solution was dropwise into 0.1 M magnesium sulphate heptahydrate solution. The white colour precipitate was started to form. Stop the reaction once the pH of the solution reaches 10-12. The formed magnesium hydroxide was sonicated and washed with methanol to remove the ironic impurities and it was dried and calcined in muffle furnace at 400 °C for 2 hrs. [

12,

13]

2.3. Characterisation

Standard analytical methods are used to study the morphological features of the synthesised copper and magnesium oxide nanoparticles. The initial confirmation of the formation of the nanoparticles can be done using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Lamda 35). For the analysis of the sample in the UV-visible spectrophotometer, the samples were ultrasonicated to disperse the particles before scanning. The size, PDI, and zeta potential of the nanoparticle can be identified using (Micromeritics, Nano Plus) [

15]. The surface morphology of the formed nanoparticles can be studied by (CAREL ZEISS, EVO 18). The functional group present in the sample and molecular interactions are studied using (Perkin Elmer, Spectrum two). [

15]

2.4. Antimicrobial Activity

It is a test used to determine the zone of inhibition and measure the antimicrobial activity of the nanoparticle. In a 250-ml conical flask, add 100 ml of distilled water and 2.8 g of nutrient agar. Keep it for sterilization for 20 minutes at 120 °C and 15 psi. The autoclaved nutrient agar medium was poured into the sterile Petri dish. After solidification of the agar, add 100 µl of both E. coli (gram-negative) and Bacillus subtilis (gram-positive) overnight culture, then spread with an L rod. Using a well puncher, the well was punched on the plate. Add 50 µl of different concentrations (20, 30, 40 mg/ml) of copper and magnesium oxide nanoparticles and a 1:1 ratio of both nanoparticles in the well. Once the samples were added, the plates were placed in the incubator at 37 °C. [

16,

17]

2.5. Cytotoxicity Assay

The monolayer cell culture was trypsinized, and using the appropriate media containing 10% FBS, the cell count was adjusted to 1.0 × 105 cells/ml. In the 96-microtiter plate, add 100 µl of cell suspension (50,000 cells/well). After 24 hours of incubation, the monolayer was formed. Remove the supernatant and wash it once with media. Then 100 µl of different concentrations of nanoparticle samples were added to each well. All the plates were incubated at 37

oC for 24 hours in a 5% CO

2 incubator. 100 µl of MTT reagent (5 mg/10 ml in PBS) was added to the well. The plates were incubated for 4 hours at 37

o C in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere. After incubation, 100 µl of DMSO was added to solubilize the formazan. A microtiter reader was used to measure the absorbance at 590 nm. The procedure was repeated three times, and the average value was taken. [

18,

19]

3. Results

3.1. Copper Oxide Nanoparticle

Once the sodium hydroxide was added to the copper sulphate pentahydrate solution, the blue colour changed to b black. The metal precursor solution is shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 2 shows the copper hydroxide solution after adding NaOH to the copper sulphate solution. This black precipitate was further washed, dried, and calcined at 400 °C in a muffle furnace.

3.2. Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticle

The white precipitate formation indicates the formation of magnesium hydroxide nanoparticles. It was further dried and calcined at 400 °C in a muffle furnace to reduce the magnesium hydroxide to magnesium oxide. The white magnesium hydroxide precipitate is shown in

Figure 4.

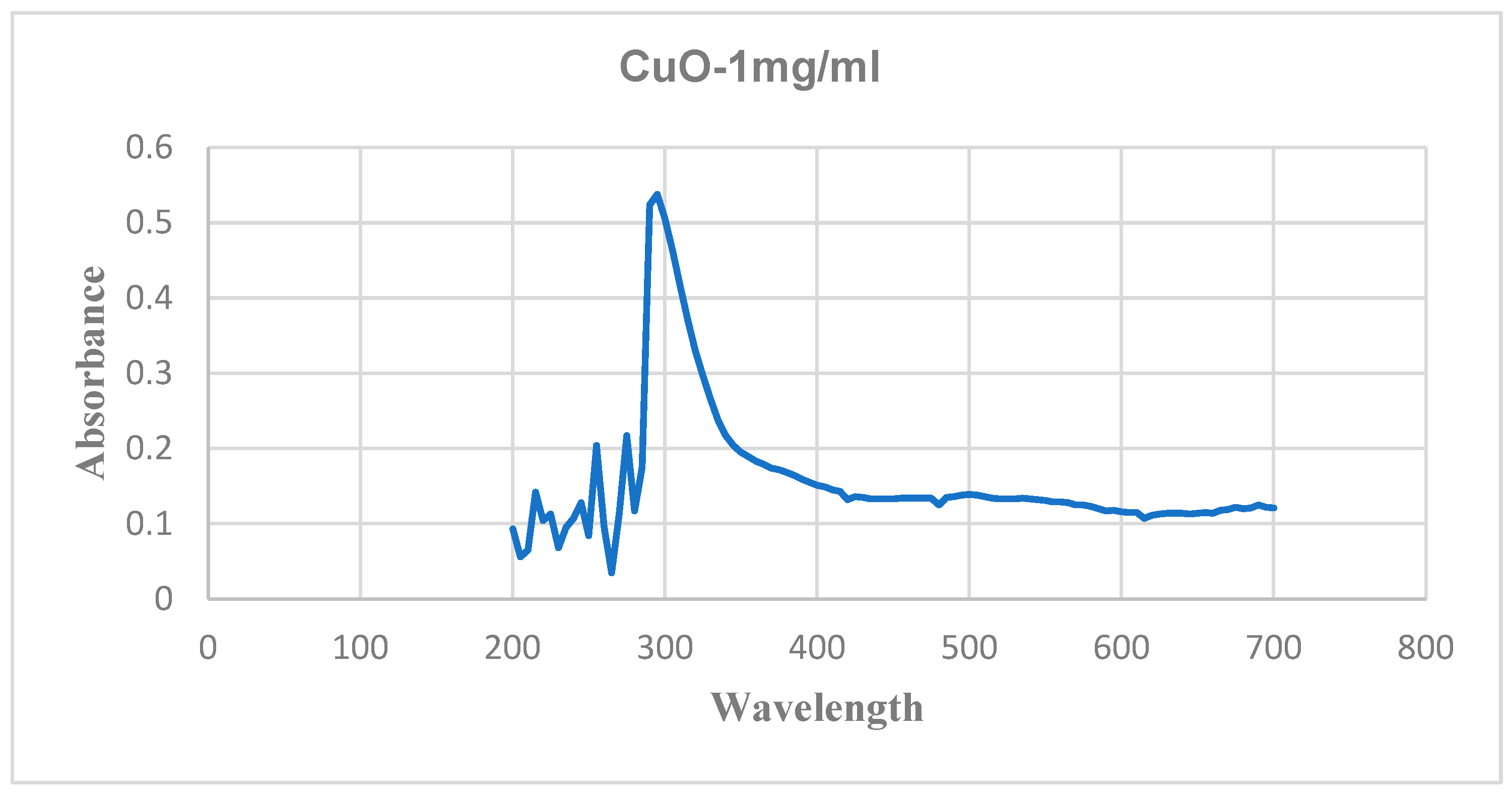

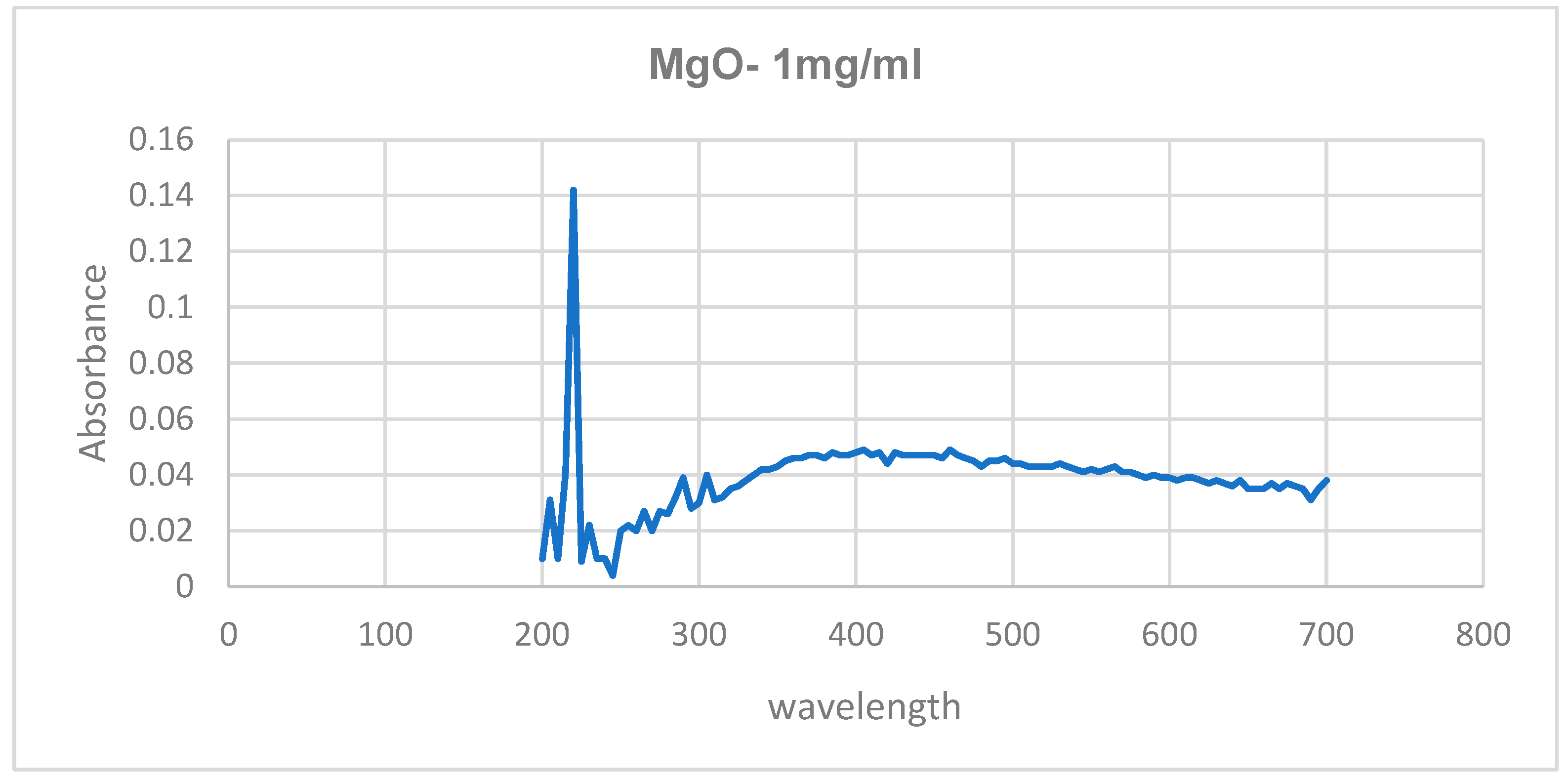

3.3. UV Visible Spectral Analysis

Initial confirmation was done using UV-visible analysis. The absorption peaks were obtained at 300 nm and 220 nm for copper oxide and magnesium oxide nanoparticles, respectively.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the UV-visible spectra of copper and magnesium oxide nanoparticles.

3.4. Particle Size Analysis

In the dynamic light scattering instrument, the particles are scanned in the range of 3 nm to 10 nm by fluctuation in the intensity of scattered light. The nanoparticles of copper and magnesium oxide are 80 and 83 nm.

3.5. Zeta Potential Analysis

The synthesized nanoparticles of copper oxide and magnesium oxide had charges of -13.4 mV and -11.7 mV, respectively, indicating moderate stability. The Zeta potential is used to measure the charge of the particle in order to determine the stability of the colloid or dispersion. The dispersion is stable when the charge of the particle ranges from -25 to 25 mV.

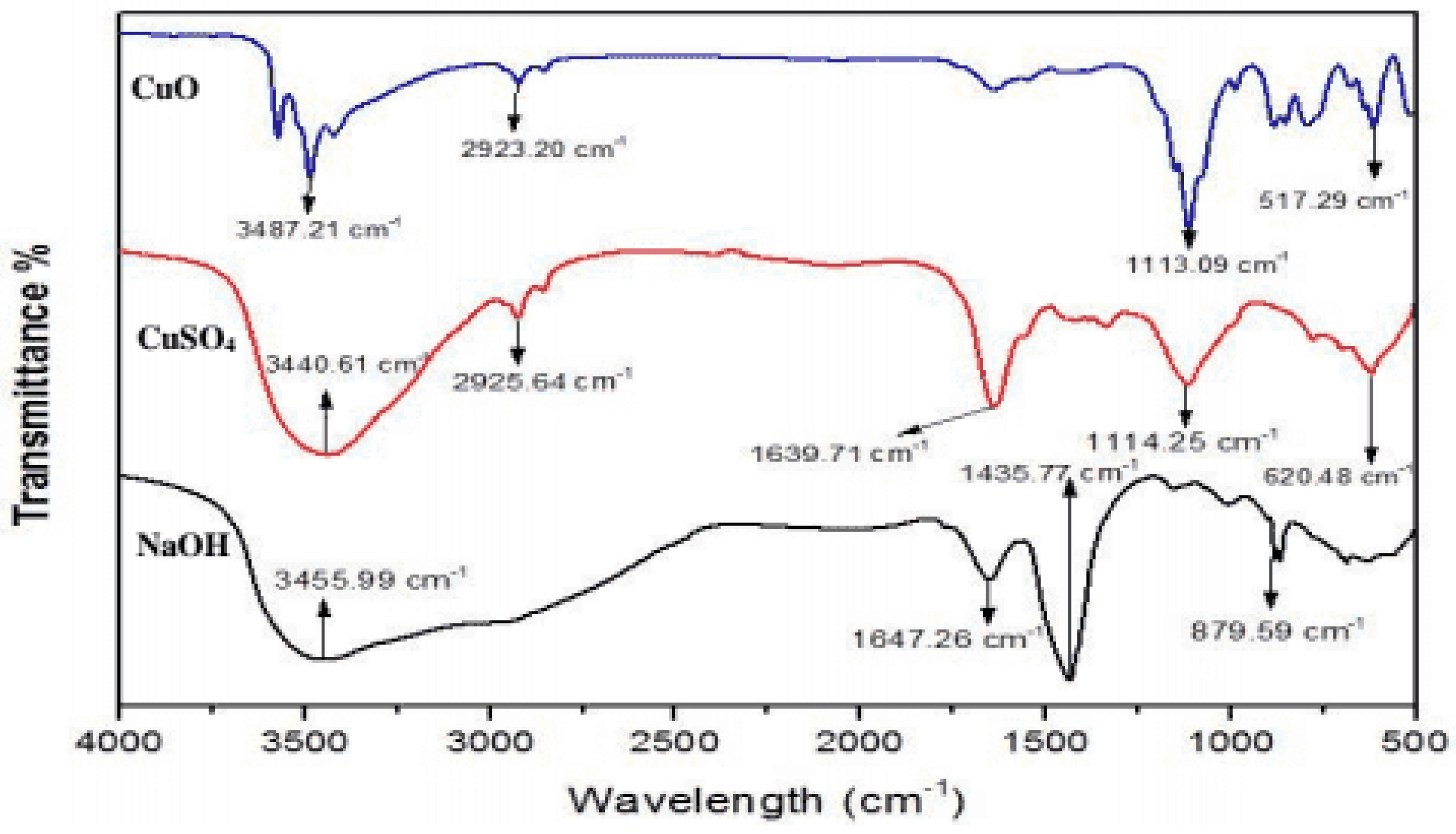

3.6. FTIR Analysis

The intensity peak between 400 and 600 cm

−1 corresponds to the stretching vibrations of the Cu-O bonds. But based on the crystal structure, the exact wavenumber can vary. A strong peak around 500–600 cm⁻

1 is considered characteristic of Cu-O bond formation in CuO nanoparticles. The O-H stretching vibrations are observed around 3400cm

−1. It is associated with atmospheric moisture in the surroundings. The band observedat1638.6 cm

−1 is due to amide bond.

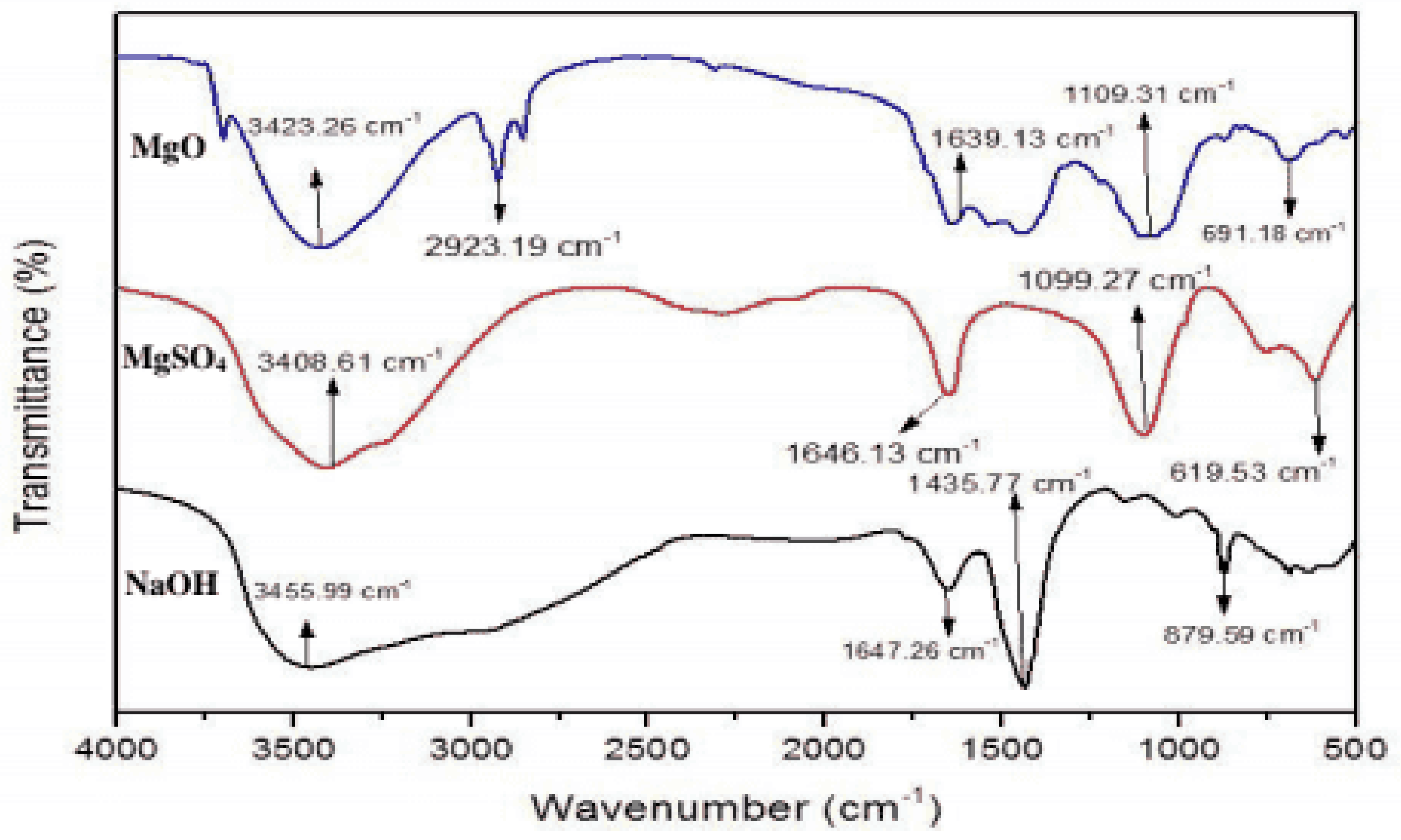

For magnesium oxide nanoparticles, the O-H stretching vibration is observed around 3400 cm

−1. The peak between 600-900 cm

−1 associated with Mg-O stretching. 1400–1600 cm–1 Peaks in this range may be related to carbonate ions or carboxylate groups, among other functions. These could result from air pollution or leftover organic compounds used in the production.

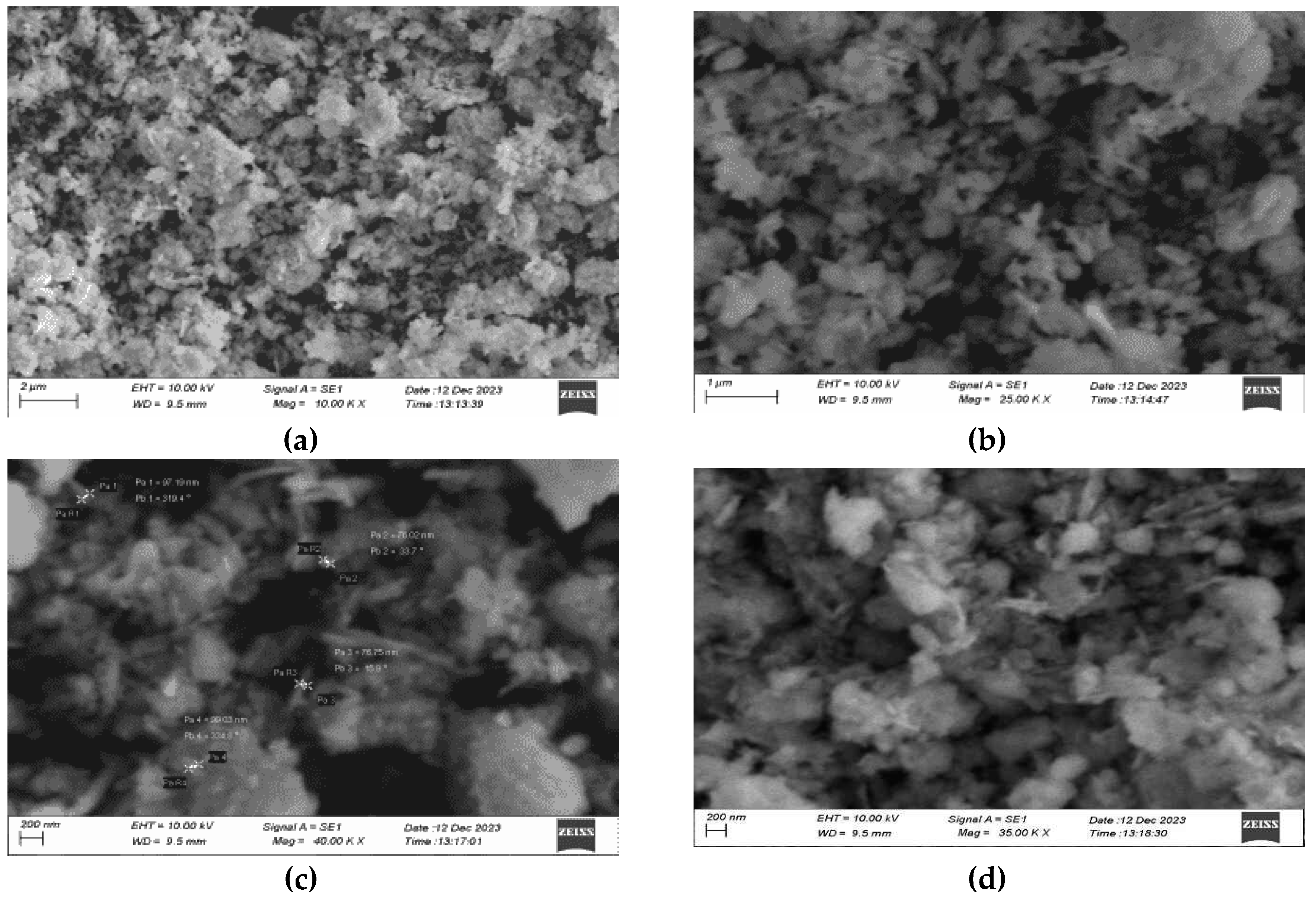

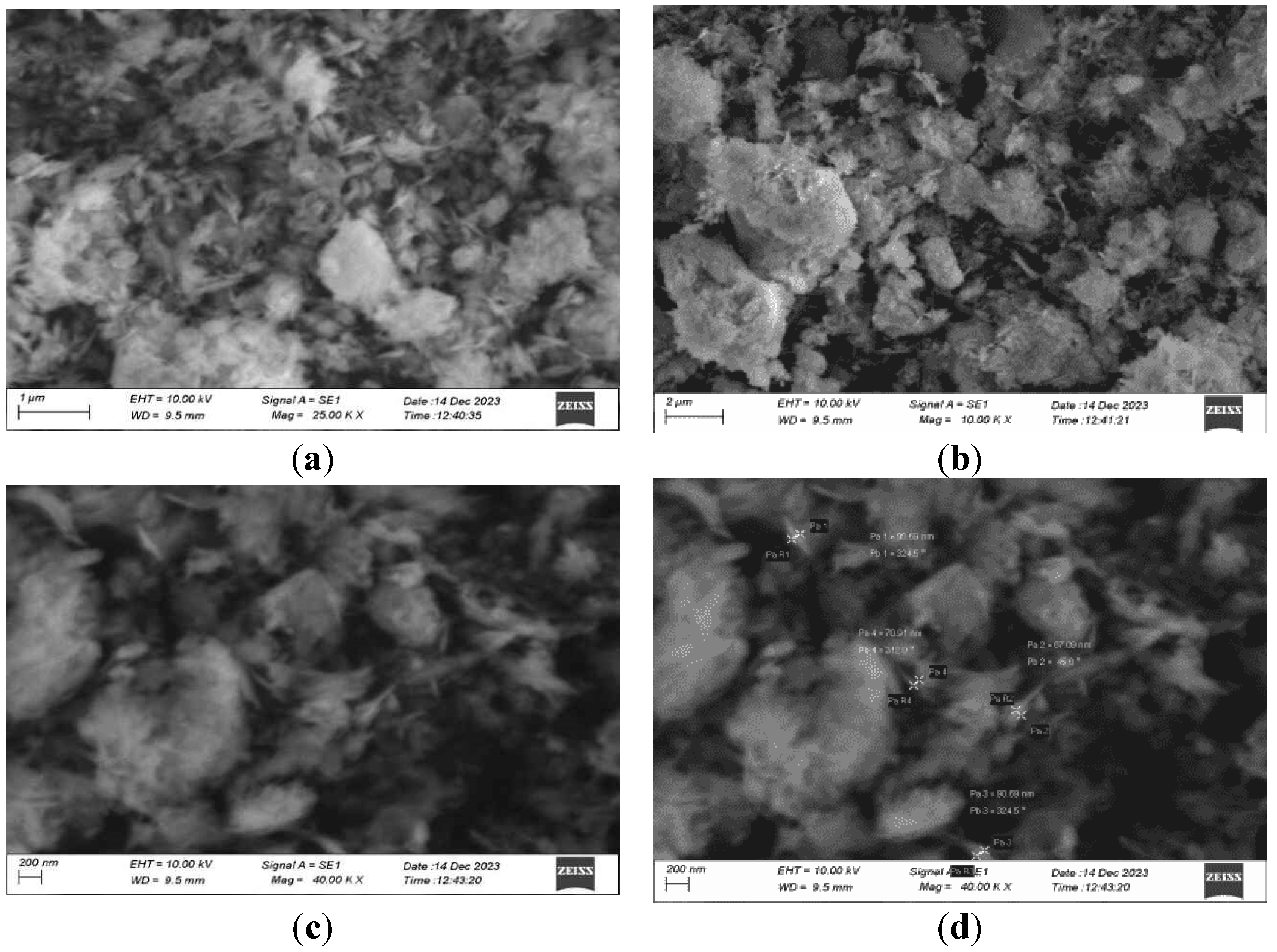

3.7. SEM Analysis

Scanning electron microscopy is used to study the surface morphology and size of the nanoparticles. The size distribution of the synthesized nanoparticles ranges from 70 to 100 nm. The average size of the nanoparticles was 80 nm. In the below images, the nanoparticles were agglomerated and colloidal in nature due to the drying and calcination processes.

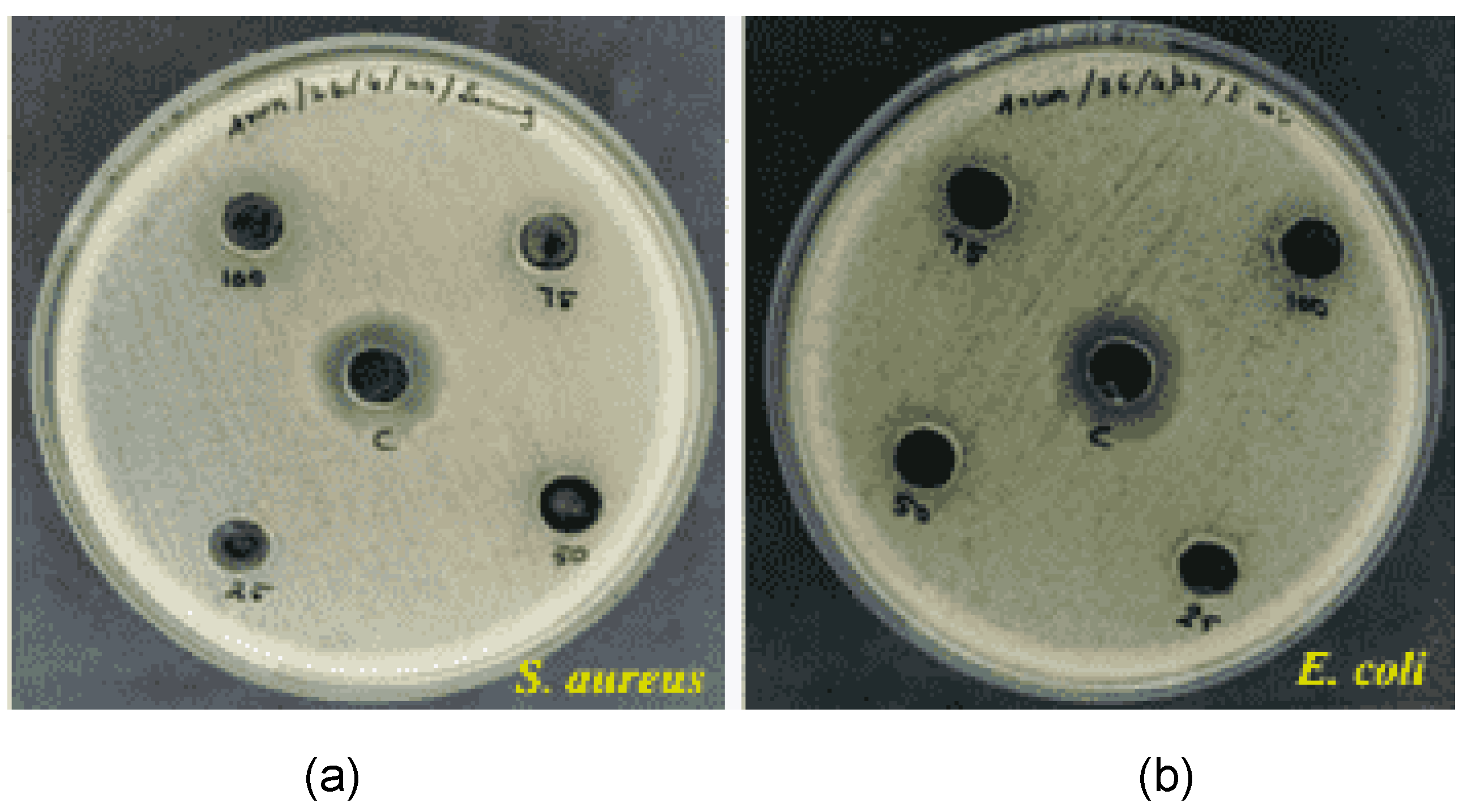

3.8. Antimicrobial Activity

We evaluated the antimicrobial activity of nanocomposite (1:1 ratio of copper and magnesium oxide), and tested it on S

taphylococcus aureus and

E. coli. Different concentrations of nanocomposite (25,50,75,100 mg/ml) were tested. The large zone was obtained in the higher concentration. The diameter of zone was decreased with increased with increasing concentrations of nanocomposite.

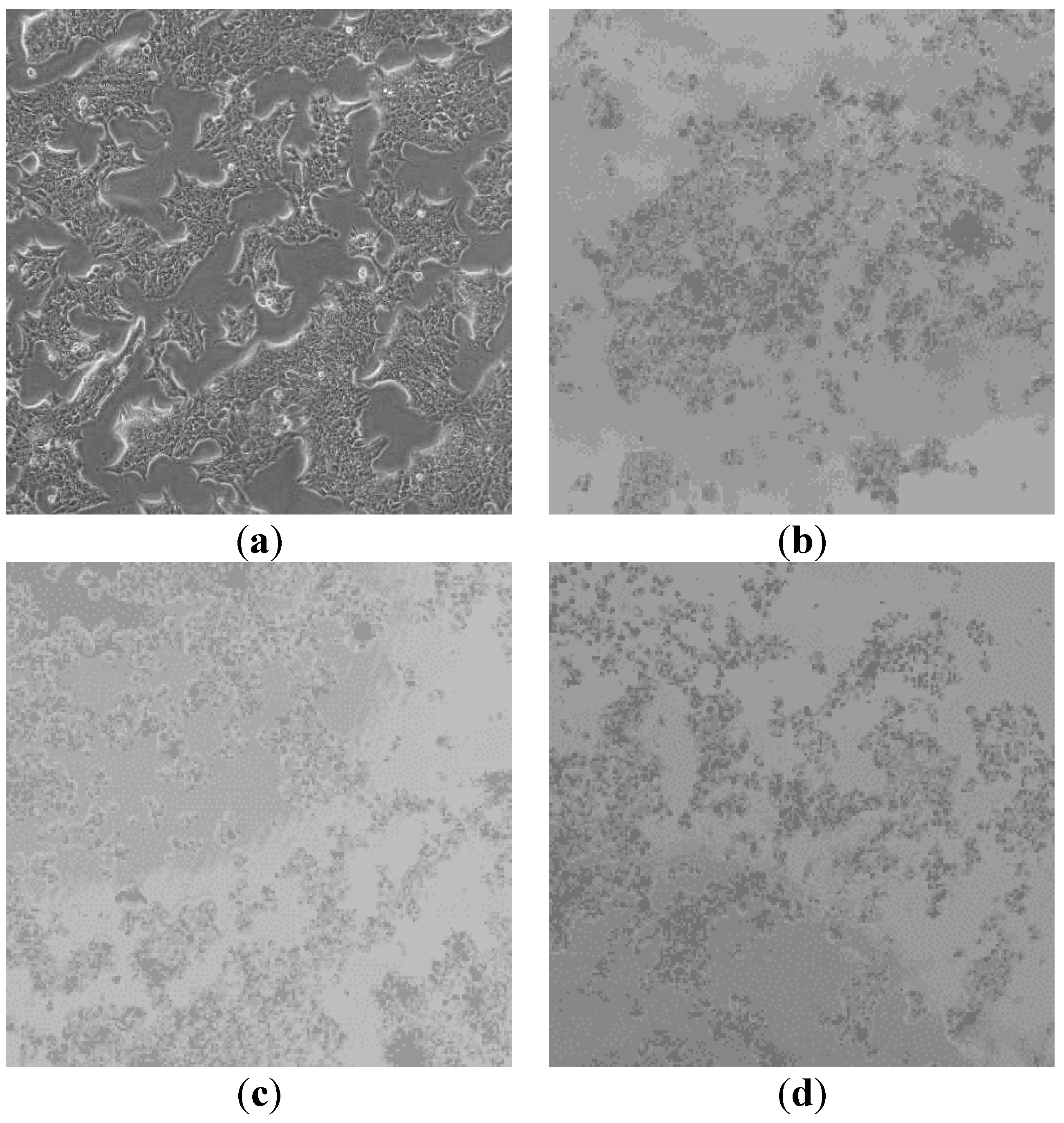

3.9. Cytotoxicity Study (MTT Method)

Using the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line, a copper and magnesium oxide nanoparticle nanocomposite was investigated. The MCF-7 cell count in

Table 1 steadily decreases as copper and magnesium oxide nanoparticle concentrations increase. The graph showing nanocomposite concentration vs. cell viability demonstrates that the nanocomposite increases as the number of cells decreases. The above figures are microscopic images of MCF-7 cells treated with different concentrations. Each figure has a different cell count according to the concentration of the nanocomposite. In the control image, there are a lot of cells. Because it is not treated with any samples. The other three figures (Figure 4.9.3,4,5) show decreasing cell counts. The concentration of 100 µg/mL shows the highest activity.

The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) can be calculated from the formula

The half-maximum inhibitory concentration of nanocomposite in the MCF-7 cell line is 53.06±0.9 µg.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the cytotoxic effects of copper and magnesium oxide nanoparticle composites against MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Our findings demonstrate that these nanocomposites exhibit significant anticancer properties, suggesting their potential as promising therapeutic agents. Previous research has established the individual capabilities of copper and magnesium oxide nanoparticles in inducing apoptosis and inhibiting autophagy in cancer cells. In this study, we hypothesized that the synergistic combination of these nanoparticles would enhance their cytotoxic effects. Our results support this hypothesis, as we observed a dose-dependent decrease in MCF-7 cell viability with increasing concentrations of the copper-magnesium oxide nanocomposite. The small size of the nanoparticles (80 nm) is likely a contributing factor to their enhanced bioactivity. Nanoparticles of this size can penetrate cell membranes more easily, facilitating their interaction with intracellular targets. Moreover, their high surface area-to-volume ratio increases the number of potential binding sites for cellular components, enhancing their biological activity. The observed antimicrobial properties of the nanocomposite are also noteworthy. Antimicrobial activity is often associated with oxidative stress, which can lead to cell death. The ability of the nanocomposite to induce oxidative stress in cancer cells may contribute to its cytotoxic effects. While our in vitro results are promising, further studies are necessary to validate the efficacy of the copper-magnesium oxide nanocomposite in vivo. Animal models can provide valuable insights into the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and toxicity of the nanoparticles. Additionally, studies investigating the mechanisms of action of the nanocomposite can help to identify potential targets for therapeutic intervention. In conclusion, this study demonstrates the potential of copper-magnesium oxide nanocomposites as effective anticancer agents. The synergistic combination of these nanoparticles, coupled with their small size and antimicrobial properties, suggests that they may be promising candidates for future therapeutic development. Further research is warranted to fully elucidate their in vivo efficacy and safety profiles.

5. Conclusion

In this study, copper oxide and magnesium oxide nanoparticles were synthesized by the sol-gel method using copper sulphate pentahydrate and magnesium sulphate heptahydrate as starting materials. Sodium hydroxide acts as a reducing and capping agent. Calcination is carried out to reduce the copper hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide into copper oxide and magnesium oxide at 400 °C in a muffle furnace. The average size of the synthesized nanoparticle is in the 80 nm range. The zeta potential value of the nanoparticles was in the range of -11 mV to -13 mV. This shows that the dispersion is stable due to the hydrophobicity of the nanoparticle. The initial confirmation of synthesized nanoparticles was tested in the UV visible spectrophotometer. Using FTIR analysis, the functional group of the nanoparticle was identified. The antimicrobial activity of the nanoparticle was tested using the spread plate technique. Copper oxide nanoparticles show maximum activity, but magnesium oxide nanoparticles were not able to diffuse in the well, so the antimicrobial activity was minimum. The best zone of inhibition for the nanocomposite of copper and magnesium was observed. SEM analysis is performed to check the surface morphology of the nanoparticle. The anticancer activity of metal nanocomposite was tested in the MCF-7 cell. The nanocomposite was showing better cytotoxicity activity in the MCF-7 cell line. The inhibition concentration of the nanocomposite in the MCF-7 cell line is 53.06±0.9 µg.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. A step by step description of the experimental procedure, including equipment, reagents, and controls. The tables summarizing the results of the absorbance of the end material. Additional graphs or images showing the raw data, control groups, and experimental replicates.

Author Contributions

A.K.M.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Review and editing, T.P.R.; Validation, Investigation, Project administration, Validation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks to Dr. P. Suresh Kumar, Head, Department of Biotechnology, Bharathidasan Institute of Technology, Anna University, Tiruchirappalli for providing lab facilities and constant support to pursue new goals. I whole heartedly thank my project guide Dr. T. P. Rajesh., Assistant Professor, Department of Biotechnology for his guidance, enterprising and valuable suggestions, encouragement and inspiration offered throughout the project. I convey my sincere gratitude to the Faculty members of Department of Biotechnology for their remarkable help in completing this project.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

References

- Witt, B.L.; Tollefsbol, T.O. Molecular, Cellular, and Technical Aspects of Breast Cancer Cell Lines as a Foundational Tool in Cancer Research. Life 2023, 13, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S. Cancer Cell Lines: Its Implication for Therapeutic Use. InCancer Diagnostics and Therapeutics: Current Trends, Challenges, and Future Perspectives 2022 Apr 16 (pp. 407-427). Singapore: Springer Singapore.Folic acid functionalized starch encapsulated green synthesized copper oxide nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery in breast cancer therapy Arokia Vijaya Anand Mariadoss.

- Woźniak-Budych, M.J.; Staszak, K.; Staszak, M. Copper and Copper-Based Nanoparticles in Medicine—Perspectives and Challenges. Molecules 2023, 28, 6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, S.; Kena, S.; Chewaka, M. Studies of Structural and Optical Properties of Copper oxide (CuO) Nanoparticles. Journal of Science, Technology and Arts Research. 2022 Dec 27;11(4):1-8.

- Mohanarangan, J.; Balakrishnan, G. Synthesis and Characterization of Copper oxide nanoparticles as Photocatalyst.

- Ghosh, D.; Majumder, S.; Sharma, P. Anticancerous activity of transition metal oxide nanoparticles. NanoBioMedicine. 2020:107-37.

- DESHMUKHSA Bionanocomposites drugs with medicinal plants for virology applications. Nanotechnology Applications in Medicinal Plants and their Bionanocomposites: An Ayurvedic Approach. 2024 May 2:241.

- Meidanchi, A. Mg (1-x) CuxFe2O4 superparamagnetic nanoparticles as nano-radiosensitizer agents in radiotherapy of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Nanotechnology. 2020 May 28;31(32):325706.

- Amina, M.; Al Musayeib, N.M.; Alarfaj, N.A.; El-Tohamy, M.F.; Oraby, H.F.; Al Hamoud, G.A.; Bukhari, S.I.; Moubayed, N.M.S. Biogenic green synthesis of MgO nanoparticles using Saussurea costus biomasses for a comprehensive detection of their antimicrobial, cytotoxicity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells and photocatalysis potentials. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0237567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Sagboye, P.A.; Umenweke, G.; Ajala, O.J.; Omoarukhe, F.O.; Adeyanju, C.A.; Ogunniyi, S.; Adeniyi, A.G. CuO nanoparticles (CuO NPs) for water treatment: A review of recent advances. 2021, 15, 100443. [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Gul, A.; Zia, M.; Javed, R. Synthesis, biomedical applications, and toxicity of CuO nanoparticles. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2023 Feb;107(4):1039-61.

- Mariadoss, A.V.A.; Saravanakumar, K.; Sathiyaseelan, A.; Venkatachalam, K.; Wang, M.-H. Folic acid functionalized starch encapsulated green synthesized copper oxide nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery in breast cancer therapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 2073–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.M.; Qaseem, S.; Shah, S.N.; Ali, S.R.; Bibi, Y.; Tahir, A.; Wahab, A. Tailoring the Magnetic and Optical properties of MgO Nanoparticles by Cobalt doping. J. NANOSCOPE (JN) 2022, 3, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, H.M.; El-Hakim, M.H.; Nady, D.S.; Elkaramany, Y.; Mohamed, F.A.; Yasien, A.M.; Moustafa, M.A.; Elmsery, B.E.; Yousef, H.A. Review on MgO nanoparticles multifunctional role in the biomedical field: Properties and applications. Nanomedicine Journal. 2022 Jan 1;9(1).

- Kishore, K.; Pandey, A.; Wagri, N.K.; Saxena, A.; Patel, J.; Al-Fakih, A. Technological challenges in nanoparticle-modified geopolymer concrete: A comprehensive review on nanomaterial dispersion, characterization techniques and its mechanical properties. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clogston JD, Crist RM, Dobrovolskaia MA, Stern ST, editors. Characterization of nanoparticles intended for drug delivery. Humana Press; 2024.

- Waris, A.; Din, M.; Ali, A.; Ali, M.; Afridi, S.; Baset, A.; Khan, A.U. A comprehensive review of green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and their diverse biomedical applications. 2020, 123, 108369. [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, R.; Yaya, A.; Mensah, B.; Nbalayim, P.; Apalangya, V.; Bensah, Y.; Damoah, L.; Agyei-Tuffour, B.; Dodoo-Arhin, D.; Annan, E. Synthesis and characterization of zinc and copper oxide nanoparticles and their antibacteria activity. Results Mater. 2020, 7, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Alafaleq, N.O.; Ramu, A.K.; Alhosaini, K.; Khan, M.S.; Zughaibi, T.A.; Tabrez, S. Evaluation of biogenically synthesized MgO NPs anticancer activity against breast cancer cells. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 31, 103874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amina, M.; Al Musayeib, N.M.; Alarfaj, N.A.; El-Tohamy, M.F.; Oraby, H.F.; Al Hamoud, G.A.; Bukhari, S.I.; Moubayed, N.M.S. Biogenic green synthesis of MgO nanoparticles using Saussurea costus biomasses for a comprehensive detection of their antimicrobial, cytotoxicity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells and photocatalysis potentials. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0237567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, A.; Saini, S.; Rai, A.K.; Pawar, S. Structural, optical, cytotoxicity, and antimicrobial properties of MgO, ZnO and MgO/ZnO nanocomposite for biomedical applications. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 19515–19525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).