Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Musculoskeletal injury (MSI) risk screening has gained significant attention in rehabilitation, sports, and fitness due to its ability to predict injuries and guide preventive interventions. This review analyzes the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) and the Y-Balance Test (YBT) landscape. Although these instruments are widely used because of their simplicity and ease of access, their accuracy in predicting injuries is inconsistent. Significant drawbacks include reliance on broad scoring systems, varying contextual relevance, and neglecting individual characteristics such as age, gender, fitness levels, and past injuries. Meta-analyses reveal that the FMS and YBT overall scores often lack clinical relevance, exhibiting significant variability in sensitivity and specificity among different groups. New findings point to multifactorial models' effectiveness that consider modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors—like workload ratios, injury history, and fitness data—for better prediction outcomes. Advances in machine learning (ML) and wearable technology, including inertial measurement units (IMUs) and intelligent monitoring systems, show promising potential by capturing dynamic and personalized high-dimensional data. Such approaches enhance our understanding of how biomechanical, physiological, and contextual injury aspects interact. This review emphasizes the shortcomings of conventional movement screens, highlights the necessity for workload monitoring and personalized evaluations, and promotes the integration of technology-driven and data-centered techniques. Moving towards tailored, multifactorial models could significantly improve injury prediction and prevention across varied populations. Future research should refine these models to enhance their practical use in clinical and field environments.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What are the theoretical underpinnings of movement screens?

- Are movement screens effective in predicting injury risk?

- What factors affect the predictive value of movement screens?

- Are the underlying premises of current movement screens valid?

- What other factors affect injury risk?

- Where do we go from here?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Underpinnings

4.2. Current Evidence on the Predictive Value of Field-Expedient Movement Screens

4.2.1. Star Excursion Balance Test/Y-Balance Test

4.2.2. The Functional Movement Screen

4.3. Factors Affecting Predictive Validity of Movement Screens

4.3.1. Age and Sex

4.3.2. Injury Definitions

4.3.3. Injury History

4.4. Can Movement Screens Predict Future Injury?

4.5. Other Injury Factors

4.5.1. Occupational Risk Factors

4.5.2. Joint Laxity

4.5.3. Sleep

4.5.4. Multifactorial Injury Risk Models

4.5.5. Workloads and Injury

4.6. Emerging Approaches in Injury Prediction

4.7. Summary & Key Takeaways

- Field-expedient movement screens like FMS and YBT show inconsistent ability to predict injuries, with mixed results across studies.

- Variables such as sex, age, sport type, injury history, and physical fitness significantly impact the validity of these screens.

- Scoring systems for movement screens often need to account for individual differences, and arbitrary criteria can obscure meaningful findings.

- While useful in specific scenarios, risk screens often generalize limitations across contexts where specificity is critical.

- Familiarity with movement tests can improve scores, questioning whether higher scores reflect true injury prevention capability.

- Acute-to-chronic workload ratios are more consistently linked to injury risk, emphasizing the importance of monitoring and balancing workloads.

- Factors like repetitive motions, poor recovery (e.g., shift work), and sleep disturbances are critical in injury risk assessments.

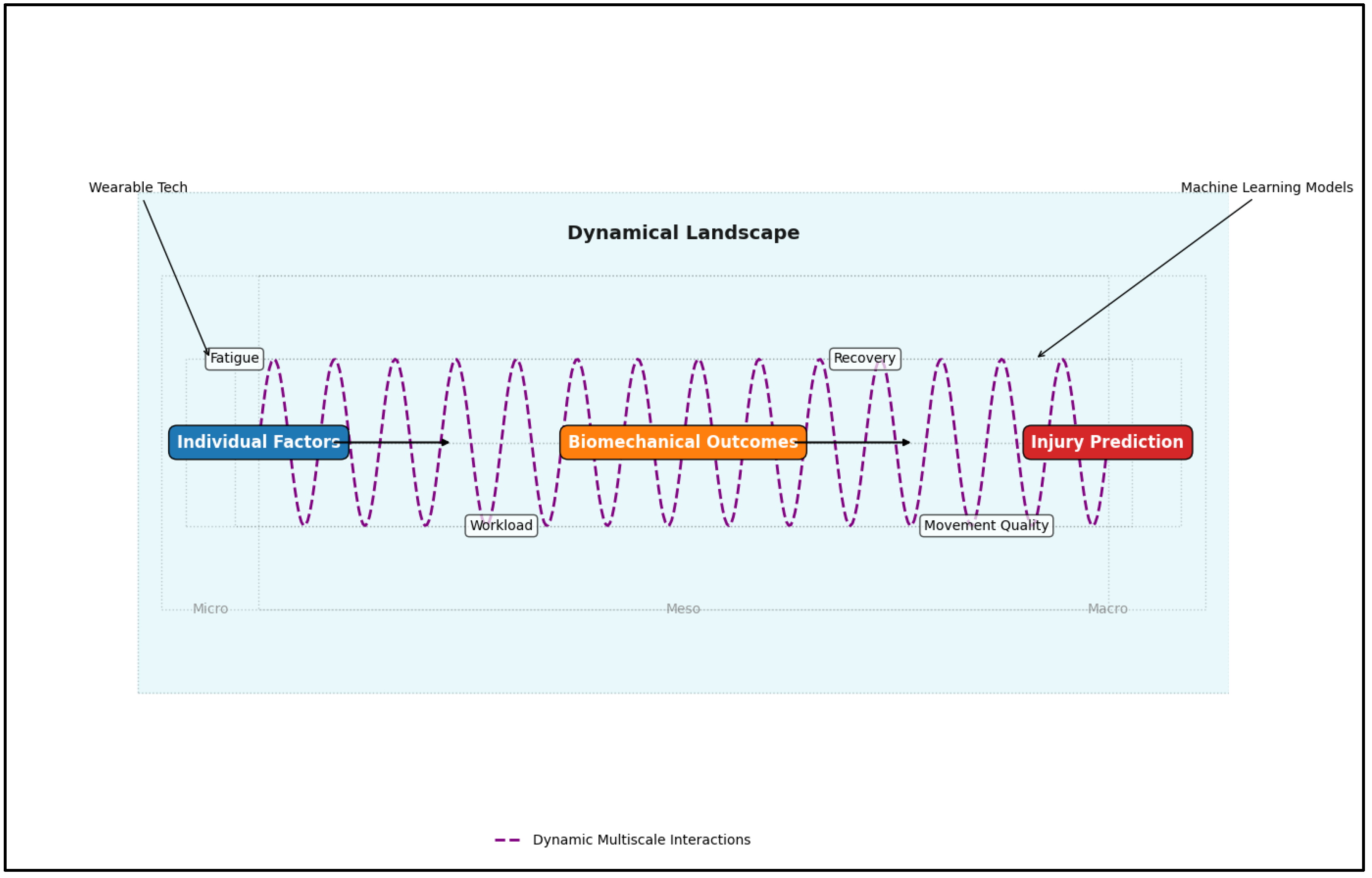

- Machine learning and wearable devices, like IMUs, offer more accurate and dynamic ways to predict injury risk through multifactorial models.

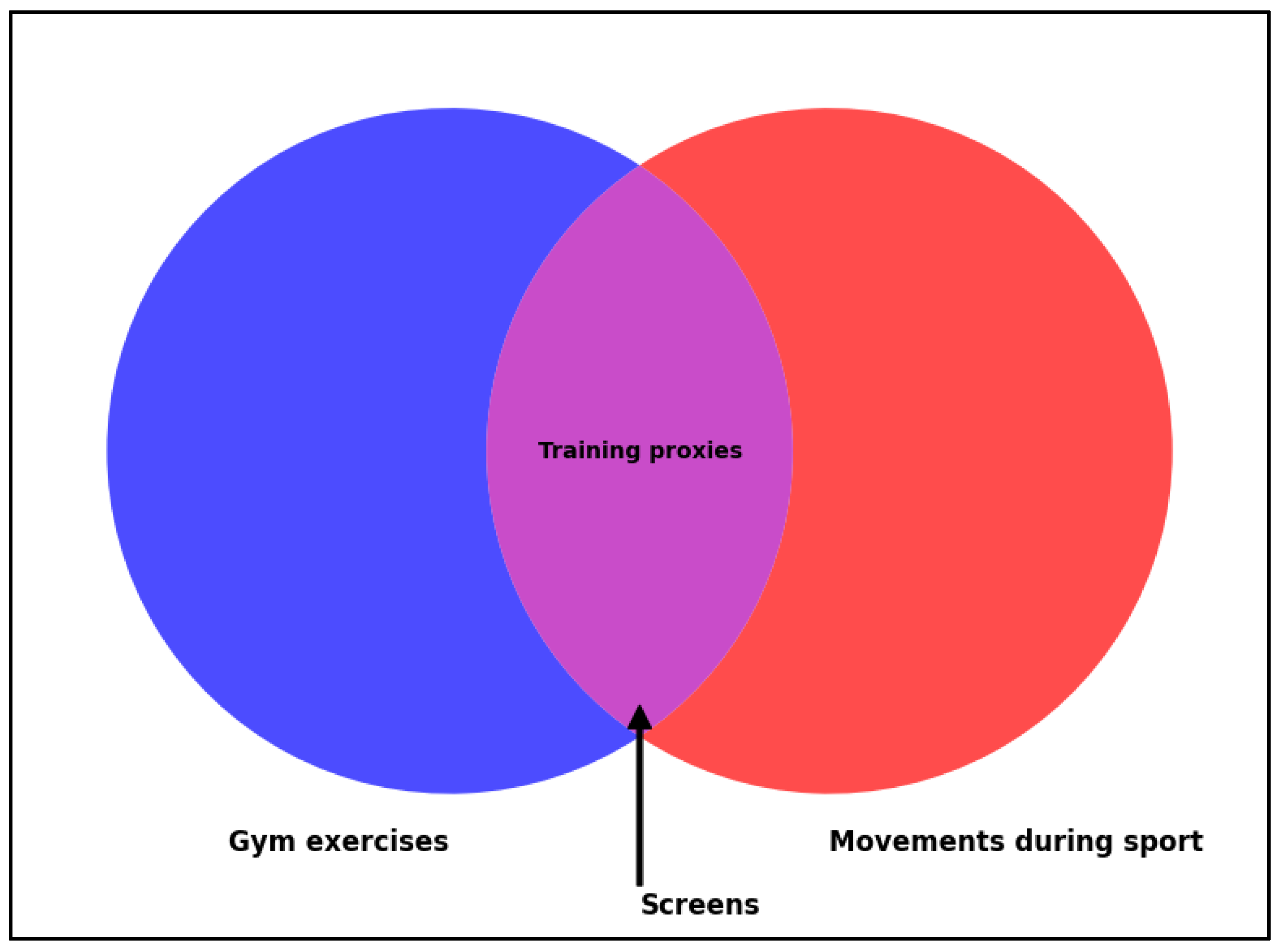

- Tailored approaches that combine relevant movements/activities assessments with broader risk factors, such as relative workloads, recovery measures, and previous injuries, will improve injury prediction.

- Adopting multifactorial and dynamic assessment models, supported by advanced technologies, is key to improving injury prediction and prevention strategies.

4.8. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kraus K, Schütz E, Taylor WR, Doyscher R. Efficacy of the functional movement screen: A review. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2014;28(12):3571-84.

- Beardsley C, Contreras B. The functional movement screen: A review. Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2014 Oct 1;36(5):72-80.

- Rinaldi VG, Prill R, Jahnke S, Zaffagnini S, Becker R. The influence of gluteal muscle strength deficits on dynamic knee valgus: A scoping review. Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics. 2022;9(1):81. [CrossRef]

- Maniar N, Cole MH, Bryant AL, Opar DA. Muscle force contributions to anterior cruciate ligament loading. Sports Medicine. 2022 Aug;52(8):1737-50. [CrossRef]

- Welsh C, Hanney WJ, Podschun L, Kolber MJ. Rehabilitation of a female dancer with patellofemoral pain syndrome: applying concepts of regional interdependence in practice. North American journal of sports physical.

- Wainner RS, Whitman JM, Cleland JA, Flynn TW. Regional interdependence: a musculoskeletal examination model whose time has come. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2007 Nov;37(11):658-60. [CrossRef]

- Ting LH, Macpherson JM. A limited set of muscle synergies for force control during a postural task. Journal of neurophysiology. 2005 Jan;93(1):609-13. [CrossRef]

- Horn CC, Zhurov Y, Orekhova IV, Proekt A, Kupfermann I, Weiss KR, Brezina V. Cycle-to-cycle variability of neuromuscular activity in Aplysia feeding behavior. Journal of neurophysiology. 2004 Jul;92(1):157-80.

- Bull HG, Atack AC, North JS, Murphy CP. The effect of attentional focus instructions on performance and technique in a complex open skill. European Journal of Sport Science. 2023 Oct 3;23(10):2049-58. [CrossRef]

- Gribble PA, Hertel J, Plisky P. Using the Star Excursion Balance Test to assess dynamic postural-control deficits and outcomes in lower extremity injury: a literature and systematic review. Journal of athletic training. 2012;47(3):339-57. [CrossRef]

- Plisky PJ, Rauh MJ, Kaminski TW, Underwood FB. Star Excursion Balance Test as a predictor of lower extremity injury in high school basketball players. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2006 Dec;36(12):911-9. [CrossRef]

- Plisky P, Schwartkopf-Phifer K, Huebner B, Garner MB, Bullock G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the Y-balance test lower quarter: Reliability, discriminant validity, and predictive validity. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2021;16(5):1190. [CrossRef]

- Chimera NJ, Smith CA, Warren M. Injury history, sex, and performance on the functional movement screen and Y balance test. Journal of athletic training. 2015 May;50(5):475-85. [CrossRef]

- Smith CA, Chimera NJ, Warren ME. Association of y balance test reach asymmetry and injury in division I athletes. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2015 Jan 1;47(1):136-41. [CrossRef]

- Lai WC, Wang D, Chen JB, Vail J, Rugg CM, Hame SL. Lower quarter Y-balance test scores and lower extremity injury in NCAA division I athletes. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. 2017 Aug 8;5(8):2325967117723666. [CrossRef]

- Cook G, Burton L, Hoogenboom B. Pre-participation screening: the use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function-part 1. North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy: NAJSPT. 2006;1(2):62-72.

- Kiesel, K., Plisky, P.J. and Voight, M.L., 2007. Can serious injury in professional football be predicted by a preseason functional movement screen?. North American journal of sports physical therapy: NAJSPT, 2(3), p.147. Kazman JB, Galecki JM, Lisman P, Deuster PA, O'Connor FG. Factor structure of the functional movement screen in marine officer candidates. J Strength Cond Res 28: 672–678, 2014.

- Kazman JB, Galecki JM, Lisman P, Deuster PA, O'Connor FG. Factor structure of the functional movement screen in marine officer candidates. J Strength Cond Res 28: 672–678, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wang X, Chen X, Dai B. Exploratory factor analysis of the functional movement screen in elite athletes. J Sports Sci 33: 1166–1172, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Koehle MS, Saffer BY, Sinnen NM, MacInnis MJ. Factor structure and internal validity of the functional movement screen in adults. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2016 Feb 1;30(2):540-6. [CrossRef]

- Dorrel BS, Long T, Shaffer S, Myer GD. Evaluation of the functional movement screen as an injury prediction tool among active adult populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports health. 2015 Nov;7(6):532-7.

- Bonazza NA, Smuin D, Onks CA, Silvis ML, Dhawan A. Reliability, validity, and injury predictive value of the functional movement screen: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of sports medicine. 2017 Mar;45(3):725-32. [CrossRef]

- Moore E, Chalmers S, Milanese S, Fuller JT. Factors influencing the relationship between the functional movement screen and injury risk in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine. 2019 Sep;49(9):1449-63. [CrossRef]

- Asgari M, Alizadeh S, Sendt A, Jaitner T. Evaluation of the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) in Identifying Active Females Who are Prone to Injury. A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine-Open. 2021 Dec;7(1):1-0. [CrossRef]

- Moran RW, Schneiders AG, Mason J, Sullivan SJ. Do Functional Movement Screen (FMS) composite scores predict subsequent injury? A systematic review with meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine. 2017 Dec 1;51(23):1661-9. [CrossRef]

- Plisky P, Schwartkopf-Phifer K, Huebner B, Garner MB, Bullock G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the Y-balance test lower quarter: Reliability, discriminant validity, and predictive validity. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2021;16(5):1190. [CrossRef]

- Eckart AC, Ghimire PS, Stavitz J. Predictive validity of multifactorial injury risk models and associated clinical measures in the US population. Sports. 2024 Apr 28;12(5):123. [CrossRef]

- Silverwood V, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Jinks C, Jordan JL, Protheroe J, Jordan KP. Current evidence on risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 2015 Apr 1;23(4):507-15. [CrossRef]

- Wáng YX, Wáng JQ, Káplár Z. Increased low back pain prevalence in females than in males after menopause age: evidences based on synthetic literature review. Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery. 2016 . [CrossRef]

- Rhon DI, Molloy JM, Monnier A, Hando BR, Newman PM. Much work remains to reach consensus on musculoskeletal injury risk in military service members: a systematic review with meta-analysis. European Journal of Sport Science. 2022 Jan 2;22(1):16-34. [CrossRef]

- Matzkin E, Garvey K. Sex differences in common sports-related injuries. NASN school nurse. 2019 Sep;34(5):266-9. [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer CE, Sacko RS, Ortaglia A, Monsma EV, Beattie PF, Goins J, Stodden DF. Functional movement screen™ in youth sport participants: evaluating the proficiency barrier for injury. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2019 Jun;14(3):436. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong R, Greig M. Injury identification: the efficacy of the functional movement screen™ in female and male rugby union players. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2018 Aug;13(4):605. [CrossRef]

- Knapik JJ, Cosio-Lima LM, Reynolds KL, Shumway RS. Efficacy of functional movement screening for predicting injuries in coast guard cadets. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2015 May 1;29(5):1157-62.

- Gnacinski SL, Cornell DJ, Meyer BB, Arvinen-Barrow M, Earl-Boehm JE. Functional movement screen factorial validity and measurement invariance across sex among collegiate Student-Athletes. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2016 Dec 1;30(12):3388-95. [CrossRef]

- Fulton J, Wright K, Kelly M, Zebrosky B, Zanis M, Drvol C, Butler R. Injury risk is altered by previous injury: a systematic review of the literature and presentation of causative neuromuscular factors. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2014 Oct;9(5):583.

- Toohey LA, Drew MK, Cook JL, Finch CF, Gaida JE. Is subsequent lower limb injury associated with previous injury? A systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine. 2017 Dec 1;51(23):1670-8. [CrossRef]

- Clifton DR, Grooms DR, Hertel J, Onate JA. Predicting injury: challenges in prospective injury risk factor identification. Journal of athletic training. 2016 Aug 1;51(8):658-61. [CrossRef]

- Chorba RS, Chorba DJ, Bouillon LE, Overmyer CA, Landis JA. Use of a functional movement screening tool to determine injury risk in female collegiate athletes. N Am J Sports Phys Ther 5: 47–54, 2010.

- Parchmann CJ, McBride JM. Relationship between functional movement screen and athletic performance. J Strength Cond Res 25: 3378–3384, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Frost DM, Beach TA, Callaghan JP, McGill SM. FMS™ scores change with performers' knowledge of the grading criteria—Are general whole-body movement screens capturing “dysfunction”? J Strength Cond Res, 2013. Epub ahead of print.

- Aleixo P, Atalaia T, Bhudarally M, Miranda P, Castelinho N, Abrantes J. Deep squat test–Functional movement Screen: Convergent validity and ability to discriminate subjects with different levels of joint mobility. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2024 Jan 30. [CrossRef]

- Hincapié CA, Tomlinson GA, Hapuarachchi M, Stankovic T, Hirsch S, Carnegie D, Richards D, Frost D, Beach TA. Functional Movement Screen Task Scores and Joint Range-of-motion: A Construct Validity Study. International journal of sports medicine. 2022 Jun;43(07):648-56. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong R. The relationship between the functional movement screen, star excursion balance test and the Beighton score in dancers. The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 2020 Jan 2;48(1):53-62. [CrossRef]

- Teyhen D, Bergeron MF, Deuster P, Baumgartner N, Beutler AI, Sarah J, Jones BH, Lisman P, Padua DA, Pendergrass TL, Pyne SW. Consortium for health and military performance and American College of Sports Medicine Summit: Utility of functional movement assessment in identifying musculoskeletal injury risk. Current sports medicine reports. 2014 Jan 1;13(1):52-63.

- Teyhen DS, Shaffer SW, Butler RJ, Goffar SL, Kiesel KB, Rhon DI, Williamson JN, Plisky PJ. What risk factors are associated with musculoskeletal injury in US Army Rangers? A prospective prognostic study. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2015 Sep;473(9):2948-58. [CrossRef]

- Dzakpasu FQ, Carver A, Brakenridge CJ, Cicuttini F, Urquhart DM, Owen N, Dunstan DW. Musculoskeletal pain and sedentary behaviour in occupational and non-occupational settings: a systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2021 Dec . [CrossRef]

- Coenen P, Willenberg L, Parry S, Shi JW, Romero L, Blackwood DM, Maher CG, Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Straker LM. Associations of occupational standing with musculoskeletal symptoms: a systematic review with meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine. 2018 Feb 1;52(3):176-83. [CrossRef]

- Macedo LG, Battié MC. The association between occupational loading and spine degeneration on imaging–a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2019 Dec;20:1-5. [CrossRef]

- Nambiema A, Bertrais S, Bodin J, Fouquet N, Aublet-Cuvelier A, Evanoff B, Descatha A, Roquelaure Y. Proportion of upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders attributable to personal and occupational factors: results from the French Pays de la Loire study. BMC Public Health. 2020 Dec;20(1):1-3. [CrossRef]

- Hulshof CT, Pega F, Neupane S, Colosio C, Daams JG, Kc P, Kuijer PP, Mandic-Rajcevic S, Masci F, van der Molen HF, Nygård CH. The effect of occupational exposure to ergonomic risk factors on osteoarthritis of hip or knee and selected other musculoskeletal diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environment International. 2021 May 1;150:106349. [CrossRef]

- Fischer D, Lombardi DA, Folkard S, Willetts J, Christiani DC. Updating the “Risk Index”: A systematic review and meta-analysis of occupational injuries and work schedule characteristics. Chronobiology International. 2017 Nov 26;34(10):1423-38. [CrossRef]

- Clari M, Godono A, Garzaro G, Voglino G, Gualano MR, Migliaretti G, Gullino A, Ciocan C, Dimonte V. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among perioperative nurses: a systematic review and META-analysis. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2021 Dec;22:1-2. [CrossRef]

- Du J, Zhang L, Xu C, Qiao J. Relationship between the exposure to occupation-related psychosocial and physical exertion and upper body musculoskeletal diseases in hospital nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian nursing research. 2021 Aug 1;15(3):163-73. [CrossRef]

- Lietz J, Kozak A, Nienhaus A. Prevalence and occupational risk factors of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals in Western countries: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2018 Dec 18;13(12):e0208628. [CrossRef]

- Epstein S, Sparer EH, Tran BN, Ruan QZ, Dennerlein JT, Singhal D, Lee BT. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among surgeons and interventionalists: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA surgery. 2018 Feb 1;153(2):e174947-.

- Pacey V, Nicholson LL, Adams RD, Munn J, Munns CF. Generalized joint hypermobility and risk of lower limb joint injury during sport: a systematic review with meta-analysis. The American journal of sports medicine. 2010 Jul;38(7):1487-97.

- Liaghat B, Pedersen JR, Young JJ, Thorlund JB, Juul-Kristensen B, Juhl CB. Joint hypermobility in athletes is associated with shoulder injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2021 Dec;22:1-9.

- Konopinski MD, Jones GJ, Johnson MI. The effect of hypermobility on the incidence of injuries in elite-level professional soccer players: a cohort study. The American journal of sports medicine. 2012 Apr;40(4):763-9.

- Singh H, McKay M, Baldwin J, Nicholson L, Chan C, Burns J, Hiller CE. Beighton scores and cutoffs across the lifespan: cross-sectional study of an Australian population. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017 Nov 1;56(11):1857-1864. [CrossRef]

- Malek, S., Reinhold, E. J., & Pearce, G. S. (2021). The Beighton score as a measure of generalised joint hypermobility. Rheumatology International, 41(10), 1707–1716. [CrossRef]

- Chennaoui M, Vanneau T, Trignol A, Arnal P, Gomez-Merino D, Baudot C, Perez J, Pochettino S, Eirale C, Chalabi H. How does sleep help recovery from exercise-induced muscle injuries?. Journal of science and medicine in sport. 2021 Oct 1;24(10):982-7. [CrossRef]

- Uehli K, Mehta AJ, Miedinger D, Hug K, Schindler C, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Leuppi JD, Künzli N. Sleep problems and work injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep medicine reviews. 2014 Feb 1;18(1):61-73. [CrossRef]

- Lisman P, Ritland BM, Burke TM, Sweeney L, Dobrosielski DA. The association between sleep and musculoskeletal injuries in military personnel: a systematic review. Military medicine. 2022 Nov;187(11-12):1318-29. [CrossRef]

- Ruan Y, Yu X, Wang H, et al. : Sleep quality and military training injury during basic combat training: a prospective cohort study of Chinese male recruits. Occup Environ Med 2021; 78(06): 433–7. [CrossRef]

- Abeler K, Bergvik S, Sand T, Friborg O. Daily associations between sleep and pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Journal of Sleep Research. 2021 Aug;30(4):e13237. [CrossRef]

- Bahr R. Why screening tests to predict injury do not work—and probably never will…: a critical review. British journal of sports medicine. 2016 Jul 1;50(13):776-80. [CrossRef]

- Lehr ME, Plisky PJ, Butler RJ, Fink ML, Kiesel KB, Underwood FB. Field-expedient screening and injury risk algorithm categories as predictors of noncontact lower extremity injury. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2013 Aug;23(4):e225-32. [CrossRef]

- Teyhen DS, Shaffer SW, Goffar SL, Kiesel K, Butler RJ, Rhon DI, Plisky PJ. Identification of risk factors prospectively associated with musculoskeletal injury in a warrior athlete population. Sports Health. 2020 Nov;12(6):564-72. [CrossRef]

- Stroud T, Bagnall NM, Pucher PH. Effect of obesity on patterns and mechanisms of injury: Systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Surgery. 2018 Aug 1;56:148-54. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Bunn P, de Oliveira Meireles F, de Souza Sodré R, Rodrigues AI, da Silva EB. Risk factors for musculoskeletal injuries in military personnel: a systematic review with meta-analysis. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2021 Aug;94(6):1173-89. [CrossRef]

- Wang D, Chen J, Lai W, Vail J, Rugg CM, Hame SL. Predictive value of the functional movement screen for sports-related injury in NCAA division I athletes. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017 Mar 31;5(3_suppl3):2325967117S00132. [CrossRef]

- O'connor FG, Deuster PA, Davis J, Pappas CG, Knapik JJ. Functional movement screening: predicting injuries in officer candidates. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2011 Dec 1;43(12):2224-30.

- Silverwood V, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Jinks C, Jordan JL, Protheroe J, Jordan KP. Current evidence on risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 2015 Apr 1;23(4):507-15. [CrossRef]

- Evans KN, Kilcoyne KG, Dickens JF, Rue JP, Giuliani J, Gwinn D, Wilckens JH. Predisposing risk factors for non-contact ACL injuries in military subjects. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy. 2012 Aug;20(8):1554-9 . [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer CE, Beattie PF, Sacko RS, Hand A. Risk factors associated with non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2018 Aug;13(4):575. [CrossRef]

- Dauty M, Crenn V, Louguet B, Grondin J, Menu P, Fouasson-Chailloux A. Anatomical and neuromuscular factors associated to non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injury. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022 Mar 3;11(5):1402. [CrossRef]

- Verschueren J, Tassignon B, De Pauw K, Proost M, Teugels A, Van Cutsem J, Roelands B, Verhagen E, Meeusen R. Does acute fatigue negatively affect intrinsic risk factors of the lower extremity injury risk profile? A systematic and critical review. Sports medicine. 2020 Apr;50:767-84 . [CrossRef]

- Eckard TG, Padua DA, Hearn DW, Pexa BS, Frank BS. The relationship between training load and injury in athletes: a systematic review. Sports medicine. 2018 Aug;48:1929-61. [CrossRef]

- Stern BD, Hegedus EJ, Lai YC. Injury prediction as a nonlinear system. Phys Ther Sport. 2020 Jan 1;41:43-8. [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt NF, Meeuwisse WH, Mendonça LD, Nettel-Aguirre A, Ocarino JM, Fonseca ST. Complex systems approach for sports injuries: moving from risk factor identification to injury pattern recognition—narrative review and new concept. British journal of sports medicine. 2016 Nov 1;50(21):1309-14. [CrossRef]

- Saxby DJ, Killen BA, Pizzolato C, Carty CP, Diamond LE, Modenese L, Fernandez J, Davico G, Barzan M, Lenton G, da Luz SB. Machine learning methods to support personalized neuromusculoskeletal modelling. Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology. 2020 Aug;19:1169-85. [CrossRef]

- Rommers N, Rössler R, Verhagen E, Vandecasteele F, Verstockt S, Vaeyens R, Lenoir M, D’Hondt E, Witvrouw E. A machine learning approach to assess injury risk in elite youth football players. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2020;52(8):1745-51. [CrossRef]

- Rossi A, Pappalardo L, Cintia P, Iaia FM, Fernández J, Medina D. Effective injury forecasting in soccer with GPS training data and machine learning. PloS one. 2018 Jul 25;13(7):e0201264. [CrossRef]

- Tixier AJ, Hallowell MR, Rajagopalan B, Bowman D. Application of machine learning to construction injury prediction. Automation in construction. 2016 Sep 1;69:102-14. [CrossRef]

- Bogaert S, Davis J, Van Rossom S, Vanwanseele B. Impact of gender and feature set on machine-learning-based prediction of lower-limb overuse injuries using a single trunk-mounted accelerometer. Sensors. 2022 Apr 8;22(8):2860. [CrossRef]

- Jauhiainen S, Kauppi JP, Leppänen M, Pasanen K, Parkkari J, Vasankari T, Kannus P, Äyrämö S. New machine learning approach for detection of injury risk factors in young team sport athletes. International journal of sports medicine. 2021 Feb;42(02):175-82. [CrossRef]

| Authors | Topic | Study type | Year | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uehli et al. | Sleep problems and work injuries | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2014 | Occupational workers |

| Toohey et al. | Association of previous injury and lower limb injury | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2017 | Athlete populations |

| Stroud et al. | Obesity and mechanisms of injury | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2018 | Injury patients |

| Snoeker et al. | Meniscal tear risk factors | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2013 | Older adults |

| Silverwood et al. | Risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in older adults | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2015 | Older adults |

| Rhon et al. | Musculoskeletal injury risk in military service members | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2022 | Military personnel |

| Plisky et al. | Validity and reliability of Y-balance test lower quarter | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2021 | Athletes |

| Pacey et al. | Generalized joint hypermobility and risk of lower limb joint injury | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2010 | Athletes |

| Moran et al. | Predicting injury with FMS | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2017 | Athletes, military, firefighters, police |

| Moore et al. | Predicting injury with FMS | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2019 | Athlete populations |

| Macedo et al. | Occupational loading and spine degeneration | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2019 | Occupational workers |

| Lietz et al. | Risk factors of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2018 | Dental professionals |

| Liaghat et al. | Joint hypermobility and shoulder injuries | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2021 | Athletes and military personnel |

| Hulshof et al. | Occupational risk factors and osteoarthritis | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2021 | Occupational workers |

| Fischer et al. | Occupational injuries and work schedule | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2017 | Occupational workers |

| Epstein et al. | Musculoskeletal disorders among surgeons and interventionalists | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2018 | Surgeons |

| Dzakpasu et al. | Musculoskeletal pain and sedentary behavior | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2021 | Adults |

| Du et al. | Occupational exposures and musculoskeletal diseases | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2021 | Nurses |

| dos Santos Bunn et al. | Risk factors for musculoskeletal injuries in military personnel | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2021 | Military personnel |

| Dorrel et al. | Predicting injury with FMS | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2015 | Active adults |

| Coenen et al. | Occupational exposures and musculoskeletal diseases | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2018 | Adults |

| Clari et al. | Musculoskeletal disorders among perioperative nurses | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2021 | Nurses |

| Bonazza et al. | Predicting injury with FMS | Systematic review, meta-analysis | 2017 | College sports teams, military personnel |

| van der Horst et al. | Nordic hamstring exercise and hamstring injuries | Randomized-controlled trial | 2015 | Soccer players |

| Verschueren et al. | Acute fatigue and injury risk | Systematic review | 2020 | Athletes, active adults |

| Van Eetvelde et al. | Predicting injury with machine learning | Systematic review | 2021 | Athletes |

| Pfeifer et al. | Risk factors for ACL injury | Systematic review | 2018 | NCAA athletes |

| Lisman et al. | Sleep and musculoskeletal injuries in military personnel | Systematic review | 2022 | Military personnel |

| Gribble et al. | SEBT and lower extremity injury | Systematic review | 2012 | Active populations |

| Fulton et al. | Previous injury an injury risk | Systematic review | 2014 | Active adults |

| Eckard et al. | Training load and injury | Systematic review | 2018 | Athlete, military, first responders |

| Bullock et al. | Methods of predicting sports injuries | Systematic review | 2022 | Active populations |

| Asgari et al. | Predicting injuries in females with FMS | Systematic review | 2021 | Active female adults |

| Wang et al. | Predictors of low back pain | Review | 2016 | NA |

| Virgile & Bishop | Task specificity in fitness testing | Review | 2021 | NA |

| Rinaldi et al. | Strength deficits in dynamic knee valgus | Review | 2022 | NA |

| Quatman & Hewett | ACL injury and valgus collapse | Review | 2009 | NA |

| McDevitt et al. | Regional interdependence | Review | 2015 | NA |

| Matzkin & Garvey | Sex differences in injuries | Review | 2019 | NA |

| Kraus et al. | Predicting injuries with FMS | Review | 2014 | NA |

| Eckart et al. | Injury risk models in the US population | Case control | 2024 | Active US citizens |

| Chennaoui et al. | Sleep and injury recovery | Review | 2021 | NA |

| Beardsley & Conteras | Predicting injuries with FMS | Review | 2014 | NA |

| Bahr | Predicting injury with screens | Review | 2016 | NA |

| Wang et al. | Predicting injuries with FMS | Prospective cohort | 2017 | Division I college athletes |

| Uhorchak et al. | Risk factors for ACL injury | Prospective cohort | 2003 | Cadets |

| Teyhen et al. | Risk factors for injury | Prospective cohort | 2015 | US Army Rangers |

| Teyhen et al. | Risk factors for injury | Prospective cohort | 2020 | US Army soldiers |

| Svensson et al. | Performance tests and injury risk | Prospective cohort | 2018 | Athletes |

| Smits-Engelsman et al. | Beighton score and generalized joint laxity | Prospective cohort | 2011 | Youth |

| Smith et al. | YBT and injury | Prospective cohort | 2015 | Division I athletes |

| Ruan et al. | Sleep quality and injuries | Prospective cohort | 2021 | Military personnel |

| Robles-Palazon et al. | Predicting injuries with machine learning | Prospective cohort | 2023 | Youth athletes |

| Plisky et al. | Predicting injuries with SEBT | Prospective cohort | 2006 | Basketball players |

| Pfeifer et al. | Predicting injuries with FMS | Prospective cohort | 2019 | Youth athletes |

| O'Connor et al. | Predicting injuries with FMS | Prospective cohort | 2011 | Marine officer candidates |

| Nambiema et al. | Occupational factors and upper body injuries | Prospective cohort | 2020 | Occupational workers |

| Lehr et al. | Predicting injuries with field-expedient screens | Prospective cohort | 2013 | Physically active adults |

| Konopinski et al. | Hypermobility and injuries | Prospective cohort | 2012 | Soccer players |

| Knapik et al. | Predicting injuries with FMS | Prospective cohort | 2015 | Coast Guard cadets |

| Kiesel et al. | Predicting injuries with FMS | Prospective cohort | 2007 | Professional football players |

| Evans et al. | Risk factors for ACL injury | Prospective cohort | 2012 | Military personnel |

| Chorba et al. | Predicting injuries with FMS | Prospective cohort | 2010 | Female, Division II athletes |

| Armstrong & Greig | Predicting injuries with FMS | Prospective cohort | 2018 | Rugby players |

| Abeler et al. | Pain and sleep | Prospective cohort | 2021 | Patients with sleep problems |

| Karnuta et al. | Predicting injuries with machine learning | Epidemiological | 2020 | Professional baseball players |

| Whitehead et al. | Beighton score and shoulder laxity | Cross-sectional | 2018 | Patients with no history of shoulder pain |

| Singh et al. | Beighton score cut-offs | Cross-sectional | 2017 | Australian population |

| Sell et al. | Predictors of proximal tibia anterior shear force | Cross-sectional | 2007 | Athletes |

| Scott et al. | Risk factors for injury | Cross-sectional | 2015 | Cadets |

| Perry & Koehle | FMS normative data | Cross-sectional | 2013 | Middle-aged adults |

| Parchmann & McBride | FMS and athletic performance | Cross-sectional | 2011 | Athletes |

| Li et al. | FMS factor analysis | Cross-sectional | 2015 | Elite athletes |

| Koehle et al. | FMS factor analysis | Cross-sectional | 2016 | Adults |

| Kazman et al. | FMS factor analysis | Cross-sectional | 2014 | Marine officer candidates |

| Kazman et al. | Physical fitness and injuries | Cross-sectional | 2015 | National Guard/Reserve |

| Hincapié et al. | FMS and joint range of motion | Cross-sectional | 2022 | College athletes |

| Gnacinski et al. | FMS factor analysis | Cross-sectional | 2016 | College athletes |

| Frost et al. | FMS and practice effect | Cross-sectional | 2013 | Firefighters |

| Dauty et al. | Risk factors for ACL injury | Cross-sectional | 2022 | Athletes |

| Chimera et al. | Effect of injury history, sex, and performance on FMS, YBT | Cross-sectional | 2015 | Division I athletes |

| Aleixo et al. | Deep squat and joint mobility | Cross-sectional | 2024 | College students |

| Lai et al. | Predicting injuries with YBT | Case-control | 2017 | Athletes |

| Kramer et al. | Risk factors for ACL injury | Case-control | 2007 | Female athletes |

| Jauhiainen et al. | Predicting ACL injuries with machine learning | Case-control | 2022 | Elite female athletes |

| Dasgupta et al. | Joint laxity and injury | Case-control | 2024 | Indian population |

| Welsh et al. | Regional interdependence approach to rehab | Case report | 2023 | Dancer |

| Ting & Macpherson | Muscle synergies during postural task | Animal study | 2005 | Cats |

| Horn et al. | Central program generators | Animal study | 2004 | Intact animals |

| Teyhen et al. | Predicting injuries with FMS | Theoretical framework | 2014 | NA |

| Stern et al. | Non-linear nature of injury prediction | Theoretical framework | 2020 | NA |

| Malek et al. | Beighton score for generalized joint laxity | Theoretical framework | 2021 | NA |

| Cook et al. | Fundamental movement screening | Theoretical framework | 2006 | NA |

| Clifton et al. | Challenges in injury prediction | Theoretical framework | 2016 | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).