Introduction: Looking large or Looking Fine?

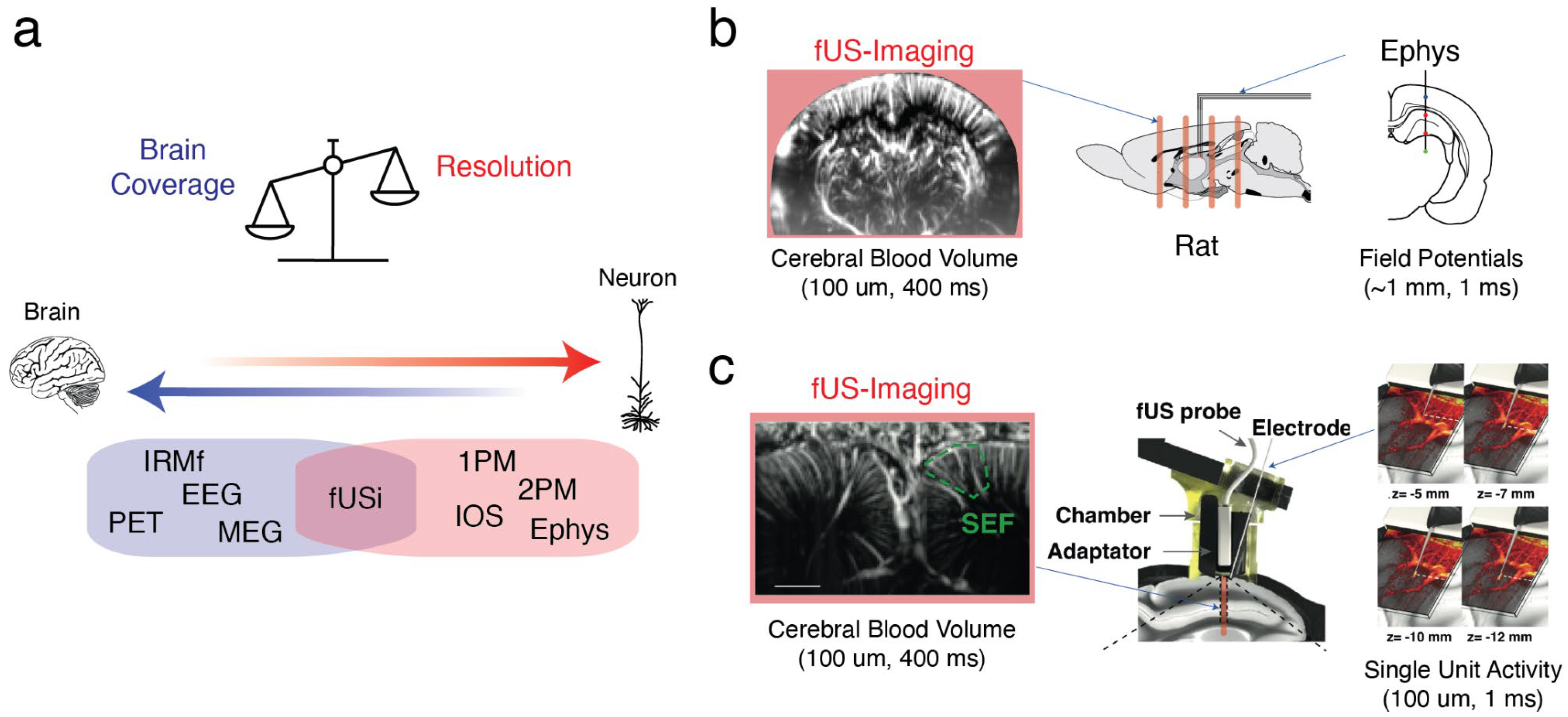

Monitoring the activity of billions of brain cells at once is not possible, except in very specific cases [Ahrens et al 2013], so neuroscientists must fix their gaze and look in detail. But because most brain processes occur at the system level and involve multiple brain structures at the same time, they also must keep looking everywhere. How does one deal with this antagonism? What is the best strategy when one wants to record brain activity during a complex cognitive process such as memory, without risking missing key information? Over the past decades, the neuroscience community has witnessed many technological advances in terms of computing power, spatial and temporal resolutions. This has considerably increased the amount of data produced [Sejnowski et al 2014], but neuroscientists keep facing the same dilemma: to look fine or to look large.

Multimodal (or cross-modal) approaches, hence named because they combine “modes” or techniques, offer the best hope to solve this problem. The prime motivation for these is that operate at different spatial and temporal scales and thus complement each other: BOLD fMRI can record whole-brain activity in a behaving subject, but its low temporal dynamics impede the study of transient events, unless it is coupled to electrophysiological recordings. Similarly, wide-field optical imaging can reveal brain-wide patterns invisible in smaller field of views, but understanding their mechanisms requires cellular-resolutions techniques or sensors of sub-threshold dynamics. Second, because the brain is a complex dynamical system, observing it from different angles is key. So, what first appeared as a constraint – the impossibility to record neurons over the whole brain at once – can also be seen as an opportunity, because different recording approaches monitor different physiological processes. While electrophysiological signals sense the electrical properties of neurons and astrocytes, optical imaging can detect the changes in vessel diameter or oxygenation in a live tissue. Multimodal approaches have this unique property: they capture intricate processes that influence one another, yielding a more complete vision of brain mechanisms than any recording approach alone.

Over the past decade, functional ultrasound imaging has emerged as an innovative technology that uses the emission and reception of ultrasound plane waves at high pulse repetition frequency. This allows for the monitoring of cerebral blood volume (CBV) and cerebral blood flow (CBF) with unprecedented resolutions. The key advantages of functional imaging include: 1- **Imaging deep brain networks**: Unlike light waves, ultrasound waves maintain their coherence while traveling through brain tissue, reducing signal loss due to scattering. This enables imaging of distributed networks deep within the brain 2- ** Lightweight probes**: the relatively low weight of the recording probes (made of piezoelectric transducers) allows for the design of lightweight holders. This makes it possible to implant them in animals, to capture images during ecological, unconstrained behaviors, as well as in head-fixed setups 3- **Extended recording duration**: There are virtually no constraints on the duration of recordings, which can last several hours within a single session and extend across sessions for several weeks or months. This makes functional ultrasound imaging an ideal tool for longitudinal studies. 4- **Compatibility with other techniques**: The technology can be combined with other recording methods, enhancing its versatility and applicability in research.

The combination of functional ultrasound imaging (fUSi) and electrophysiology (ephys) (see

Figure 1) is particularly interesting, because it takes advantage of both methods, namely the large field of view of fUSi and the temporal resolution of electrophysiology. Over the past decade, it has demonstrated its potential for investigating the large-scale correlates of epileptic seizures in vivo [Macé et al 2011, Sieu et al 2015]. This approach can also be used to study brain rhythms that reflect coordinated neural activity [Bergel et al 2018, 2020] or single-unit activity in non-human primates engaged in cognitive tasks [Claron et al 2023].

Notably, fUS imaging provides access to hemodynamics with greater sensitivity and resolutions than fMRI scanners. It can be utilized in various setups, including head-fixed, sleeping and freely-running animals. Therefore, the fUS-Ephys approach has the potential to significantly enhance our understanding of neurovascular coupling, which is the fundamental biological process underlying neuroimaging data in humans and is impaired in many pathological conditions.

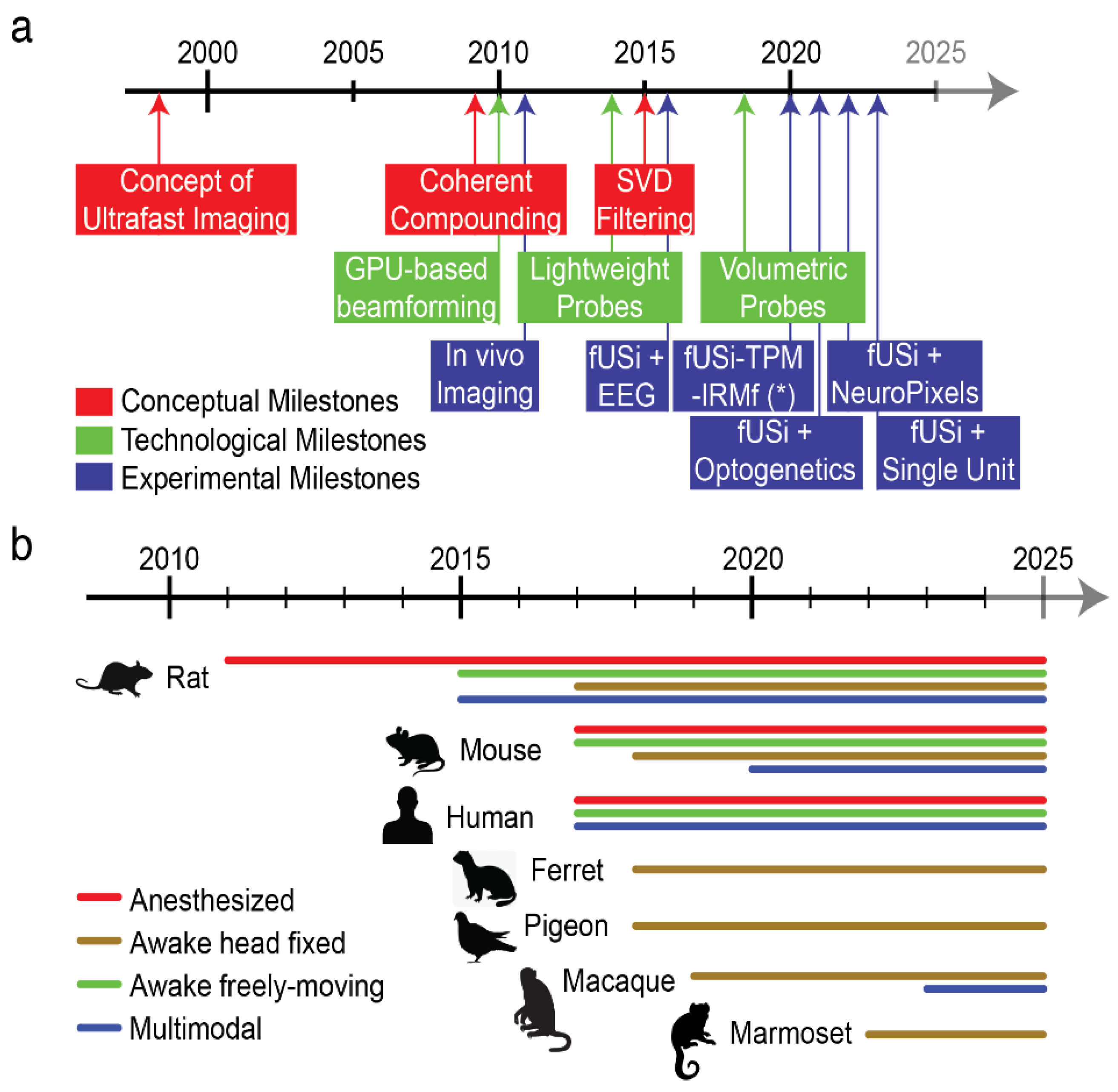

A Brief History of Functional Ultrasound Imaging – Significant Milestones

The Advent of Functional Ultrasound Imaging

The evolution of brain imaging has led to the development of various modalities designed to provide increasingly detailed views of living bodies. Early in the 1950s, Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound (TCD), was applied through the temporal bone and shown to effectively monitor blood flow in large basal intracerebral arteries [Aaslid et al. 1982]. However, its limited sensitivity made detecting slower blood flow in smaller vessels challenging. Interestingly, identifying slow blood flow became possible by significantly increasing the frame rate of ultrasound scanners to thousands of frames per second, compared to the standard rate of 20-50 frames per second used in conventional ultrasound systems. The clinical potential of ultrafast ultrasound was first highlighted in elastography and cancer diagnosis [Tanter et al 2008]. Subsequently, it was used to detect changes in cerebral blood flow during whisker stimulation in a rat model, where Ultrafast Doppler successfully captured subtle alterations induced by neurovascular coupling, leading to functional ultrasound imaging (fUSi) [Macé et al 2011].The fUSi signal is directly proportional to cerebral blood volume (CBV) and correlates with local dendritic calcium concentration.

Since its initial image acquisitions, functional ultrasound imaging (fUSi) has proven to be a powerful technique for a variety of applications in both animal models and clinical settings. It has successfully been applied to the mapping of resting-state networks in the brain in lightly sedated mice, providing evidence for task-induced deactivation and disconnection of a major default mode network hub [Ferrier et al 2020]. Additionally, fUSi has been used to study alterations in brain connectomes under diverse conditions, such as fetal growth restriction and models of arthritis-related pain [Rahal et al 2020]. This technique has also shown effectiveness in pharmacological studies and drug discovery, and it has recently expanded to include functional imaging of the spinal cord [Claron et al 2021]. Furthermore, fUS imaging has been employed to map sensory cortical regions related to olfaction, audition, vision, and nociception, as well as to track spreading depression waves [Rabut et al 2019]. In non-human primates, fUS imaging has demonstrated the ability to provide single-trial imaging during complex tasks, yielding valuable insights into movement control and planning [Dizeux et al 2019]. In human applications, fUS imaging has capitalized on unique clinical situations where the skull is absent, such as during functional cortical mapping in intra-operative craniotomy procedures [Imbault et al 2017] and through the anterior fontanelle window in newborns during seizures or while observing resting-state spontaneous activity [Demene et al 2017].

The Physics of Functional Ultrasound Imaging

Several excellent reviews have been published focusing on the physical principles underlying ultrafast ultrasound imaging [Tanter and Fink 2014, Deffieux et al 2018, Montaldo et al 2022]. Briefly, fUSi takes advantage of the combination of (1) plane wave emission/reception rather than Pulsed-Doppler line-by-line image reconstruction typically used in conventional echography to maintain a very high frame rate (up to 1KHz) at each location in the imaging field (2) coherent summation of beamformed images, known as compound imaging, and post-hoc signal processing to separate tissue clutter signal from echoes back-propagated by red blood cells [Mace et al 2013, Demene et al 2015] to generate maps of cerebral blood volume (CBV) over a single plane or volume. fUSi can image deep into the body due to the lesser interactions and scattering-related distortions of ultrasound wavefronts as they travel into the body. However, as for any wave, there is a trade-off between frequency and penetration. In practical terms, it basically means that fUS users must decide between the size of the imaging field or the spatial resolution they typically need, with one parameter constraining the other. A typical frame rate of 2.5 Hz is commonly-used in the community, with a depth of 2 mm with 100-150 microns resolution in rodents, and a maximal imaging depth of 1 cm at 500 microns resolution in non-human primates. Similarly, the frame rate can be increased by increasing the pulse repetition frequency at the expense of image quality, particularly in small vessels. With a spatial resolution of 100 µm, a typical temporal resolution of 100 milliseconds, and a blood flow sensitivity of ~1 mm·s⁻¹, fUSi stands out as a highly competitive neuroimaging modality in neuroscience.

Opportunities in Combined fUS-Ephys Recordings

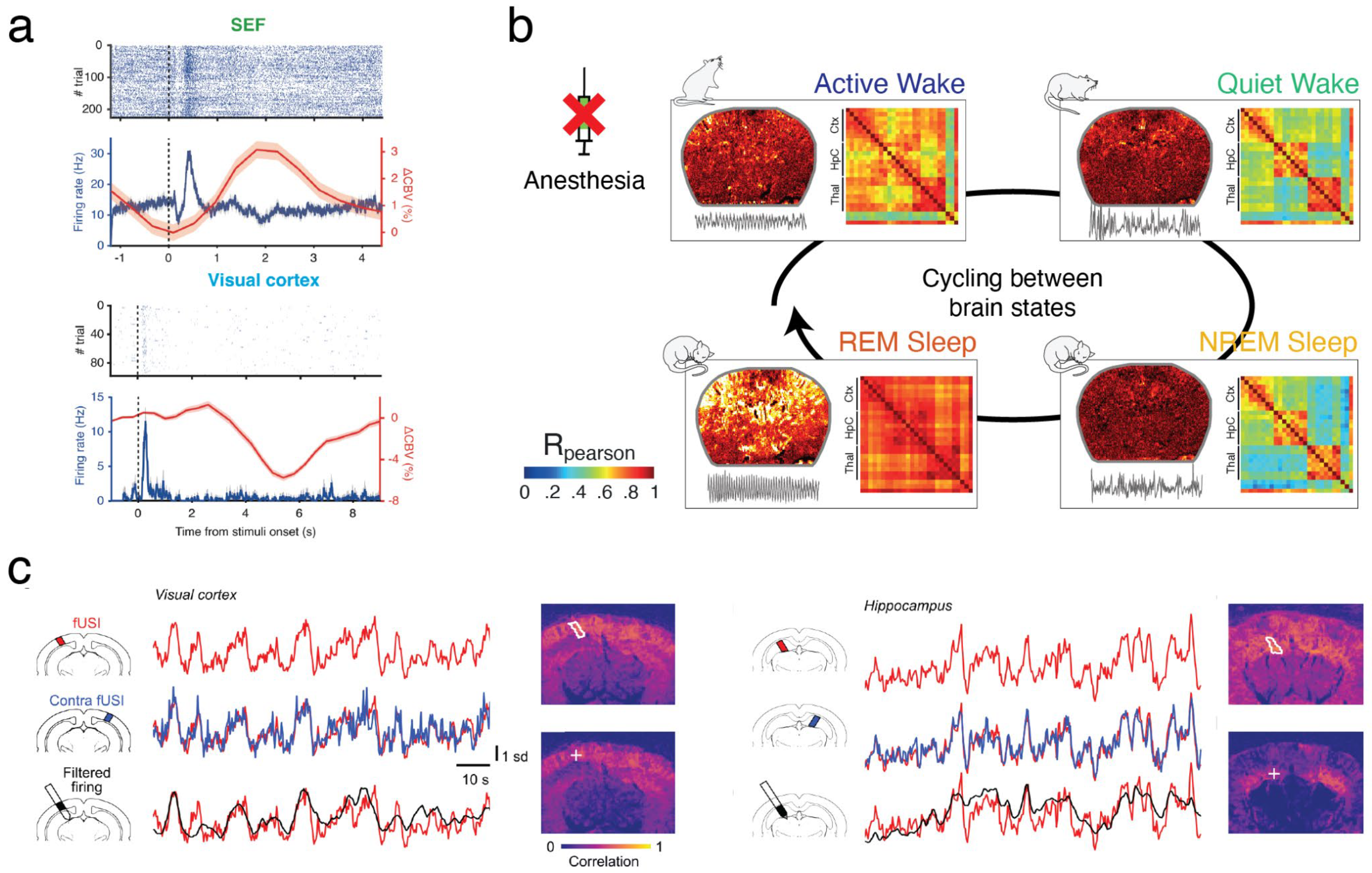

Revealing the Large-Scale Correlates of Brain Rhythms

Brain rhythms have been observed as early as 1929 concurrent with the discovery of electro-encephalography [Berger, 1929]. They emerge from the collective coordinated firing of neurons in response to a specific behavior (attention, locomotion, decision making) or spontaneously across different brain states (drowsiness, NREM sleep, REM sleep) and call also be the hallmark of pathological conditions (epilepsy, narcolepsy). Brain rhythms arise from neuronal firing but, in turn, also affect it, because the fluctuation in extracellular potential modulates the excitability of neurons. Observing the neural correlates of brain rhythms is crucial to understand their generative mechanisms and their mechanical effects, but this is very hard to do in practice due to the invasive nature of electrophysiology or the poor spatial resolution of EEG.

The combination of fUS and electrophysiology is particularly well-suited to solve these issues and thus better characterize brain states. It has been successfully used to reveal the correlates of theta rhythm (7-9 Hz), a prominent oscillation observed in the hippocampus of mammals during active behavior such as locomotion and REM sleep. Interestingly, theta rhythm is coupled with higher frequency rhythms such as gamma oscillations (80-120 Hz) especially prominent in the dentate gyrus of rodents. These oscillations precede and correlate with local cerebral blood volume (CBV) in many brain regions, with a consistent delay of 1.0 to 1.5 seconds during REM sleep [Bergel et al 2018] and wake [Bergel et al 2020]. This approach is not limited to theta and can be generalized to study the spatiotemporal dynamics of any brain rhythm, with the assumption that hemodynamics are faithful proxies of neuronal activity. Though this relationship is complex, a recent study has demonstrated that the spatiotemporal match of fUSi signals tightly correlates with neural activity [Lambert et al. 2024].

Studying Neurovascular Coupling Across Brain States

In chronic rat models, techniques such as thinned-skull procedures or the implantation of acoustically transparent cranial windows have been proposed to maintain imaging quality and perform longitudinal recordings extending the scope of fUSi to non-acute preparations. Additionally, the introduction of microbubble contrast agents and nanometric gas vesicles has enhanced the fUS signal, facilitating non-invasive imaging in rats. One major advantage of fUS imaging over functional MRI (fMRI) is its capacity for deep brain imaging in awake or freely moving animal models. This crucial capability stems from the miniaturization of ultrasonic probes mounted on the animal's head, enabling whole-brain imaging in actively behaving rodents during various activities such as absence seizures, operant tasks, different states of sleep, and locomotion in mazes. Awake imaging also allows for dynamic monitoring of functional connectivity without the potential confounding effects of anesthesia (see

Figure 3). In adult humans, the portability of fUS imaging positions it as a suitable modality for developing minimally invasive brain-machine interfaces, especially when ultrasonic transducers are implanted within the skull to image through the intact dura. This approach has recently been demonstrated for decoding movement intentions in the posterior parietal cortex of macaques.

An important avenue for further studies will be to evaluate the impact of diffuse neuromodulator systems on fUSi signals for instance acetylcholine and noradrenaline which are known to be modulated across the sleep-wake cycle and have potent effects on cerebral perfusion and can modify neurovascular coupling [Lecrux and Hamel 2016]. Even during a supposedly homogenous state such as wake, fUSi responses have been demonstrated to differ dramatically within the same recording session in freely moving rats [Bergel et al 2020] and in non-human primates performing cognitive tasks, where fUSi signal “drops” could predict performance, in relation to evolution of pupil diameter [Claron et al 2022]. It is thus probably that neuromodulator systems shape wake into several substates, with different neurovascular responses that may explain behavioral variability.

Studying Neurovascular Coupling Across Brain Regions

The sensitivity provided by fUSi enables researchers to not only investigate how vascular dynamics evolve during state transitions but also how specific brain regions contribute to these changes. By facilitating simultaneous comparisons across regions, fUSi can illuminate the interactions between cortical and subcortical structures under varying conditions. In animal studies, its minimally invasive nature and capacity for chronic imaging allow for long-term observation of neurovascular dynamics, yielding valuable insights into processes such as learning, aging, and disease progression [Brunner et al 2024]. This comprehensive approach supports robust, cross-validated findings, offering deeper insights into functional connectivity, causal interactions, and pathophysiological mechanisms. For example, integrating fUSi with functional MRI (fMRI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) can demonstrate how structural disconnections contribute to functional deficits in stroke or neurodegenerative diseases [Rabut et al 2020]. Additionally, multimodal imaging during learning processes can shed light on how structural plasticity underlies functional adaptation. Ultimately, these advancements are transforming our ability to study and understand the brain in health and disease.

In healthy human subjects, neurovascular coupling is the cornerstone of most neuroimaging modalities such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), intrinsic optical imaging (IOS) or two-photon laser-scanning microscopy (TPLSM) which monitor changes in hemodynamic parameters. Such parameters like blood-oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal or total hemoglobin concentration are used to infer whether a region is ‘activated’ or ‘deactivated’. How this relates to neuronal activity, firing rate and cell type is however unclear. Importantly, most BOLD-fMRI studies rely on a canonical hemodynamic response function, that was historically computed in the monkey primary visual cortex in response to visual gratings [Ogawa, 1990]. Recent studies have shown that NVC is both region-dependent, state-dependent and very sensitive to the methodological approach used (anesthesia for instance) [Gao et al., 2017], which advocates for a cautious revisiting and reinterpretation of neuroimaging data.

Longitudinal Recordings

Ultrasonic plane waves can travel deep into the body with limited interaction with the live tissue and limited energy dissipation by heat. Compared to fMRI where prolonged sequences can generate or optical imaging where phototoxicity of bleaching are strong constraints, these limitations are relatively absent in fUSi recordings, leaving virtually no constraint on recording duration and repetitions. This is interesting in developmental studies where plasticity processes occur over the course of weeks or months, or to assess the impact of circadian rhythms where continuous recordings for more than 24 hours are extremely valuable. One still has to take into account that prolonged recording in freely-moving conditions (even more for head restraint studies) induce stress and exhaustion as the total weight of the fUSi probe and the electrophysiology apparatus is significant.

Challenges in Combined fUS-Ephys Recordings

Technical and Methodological Challenges

We review the significant challenges one will face for fUSi recordings combined with electrophysiology, which are also present to a lesser extent in unimodal fUSi studies. Good practices in surgical preparation and data collection increase the reproducibility of research results and provide a solid ground for collaborative projects within an expanding community.

Designing long-lasting implants

Despite its rapid advancement, fUSi faces significant challenges related to the transcranial propagation of ultrasonic waves. This propagation is severely obstructed by the strong attenuation and diffraction effects caused by the skull bone, an obstacle that ultrasound waves must cross once after emission and again after backpropagation. Fortunately, the skull thickness in mice, which are a key animal model for neuropathological studies, and in young rats allows for transcranial fUS imaging through the intact skull [Tiran et al 2017]. As a result, transcranial fUS imaging in mice has become widely utilized, particularly in pharmacological research.

In adult rats and larger species, researchers must decide between thinned-skull approaches, which limit tissue damage but do not prevent bone regrowth and cranial windows which cause inflammation and modify intracranial pressure. Fortunately, replacing the bone with molded biocompatible polymers such as polymethyl-pentene (TPX) has proven very valuable to acquire quality images for up to 8 weeks in rats. Sealing this polymer with dental cement is a critical step to ensure no bubbles can form between brain tissue and the prosthesis, as well as to prevent infection. Thinned-skull preparations typically last for several days before bone regrowth.

“Real-estate considerations”

Electrophysiological recordings often require bulky boards or connectors to be fixed onto the animal’s head, particularly for silicon-probe or neuropixels recordings where electrodes are costly, fragile and not flexible. This has strongly precluded the generalization of combined fUSi recordings with silicon-probe in rodents except in acute setups where the electrode is removed between recording sessions [Nunez-Elizalde et al 2022, Lambert et al 2024]. An alternative in freely-moving is to use flexible electrodes such as foldable local field potential electrodes that can be bundled together and inserted into a fixed cannula anchored to the skull [Sieu et al 2015]. Because these electrodes are static and thin they do not interfere with the ultrasound emission/reception. Conversely, electrodes need to be properly grounded so that ultrasound waves do not contaminate electrophysiological recordings.

In larger animal models such as primates, there is more room to fit a descending drive with a classical recording electrode next to the ultrasound probe (see

Figure 1). The design of dedicated recording chambers and custom probe holder is key to ensure a compact design. Whereas rodents may not have the strength to remove the recording chamber on their own, larger animals can do so. It is thus critical to favor a compact design and ensure proper habituation, on the days following surgery, for instance with a 3D printed dummy probe.

Maintaining an ecological behavior

The development of lightweight wearable probes has been a game changer for freely-moving studies. In 10 years, the size and weight of the ultrasound probes have been dramatically reduced as well as the flexibility of the recording cable. At present recordings can be performed over one or several planes in freely-moving rats, with a simple pulley/counterweight system, without holding the tether. More complex designs and active involvement of the experimenter are required in freely-moving mice. Cable torsion can be an issue unsolved at present, because rotating commutators like the ones used in electrophysiology have not yet been adapted to fUSi probes.

As opposed to linear transducer arrays used in planar recordings, two-dimensional matrix arrays used to acquire volumetric data have a thick stiff cable, forcing animals to be head-restrained during data acquisition which may generate stress. Regular handling and habituation sessions are necessary. Of note, daytime recordings and nighttime recordings may yield different results as well as room temperature in particular for sleep studies, it is therefore critical to recording animals in a standardized manner to increase reproducibility.

Finally, movement artifacts can be minimized in both setups by designing probe holders that maintain a mechanical contact between the fUSi probe and the animal skull. This is typically achieved by implanting a permanent wearable probe holder on the animal during surgery and by designing a second part (sleeve) that maintains mechanical contact with the probe, either with magnets, screws or a guide pole.

Data visualization and atlas registration

One of the final obstacles to a widespread use of fUSi in the future is the lack of tools to visualize ultrasound data, particularly when coupled to other recordings techniques that may have been acquired with different computers. Synchronizing acquisition systems such as video, electrophysiology, optogenetic stimulations can either be done upon acquisition by using a master clock and trigger pulses to start acquisition simultaneously or a posteriori by collecting “trigger out” pulses for each recording apparatus and re-synchronizing post-hoc. Closed-loop systems require the first option. Several custom softwares have been designed by different teams but there is a dire need for a simple tool and a standardized viewer, for instance to pre-process and normalize imaging data.

The second major challenge one faces is to properly localize brain regions on functional ultrasound images, because no standard vascular atlas is yet available, let alone in non-rodent species. A first approach is to use a digitized version of a standard atlas [Paxinos and Watson 1982, Mikula et al 2007, Papp et al 2014] and manually register coronal or sagittal sections using prominent vascular landmarks, such extra-hippocampal arteries and Willis’s circle. This fails to register non-coronal planes (diagonal for instance) and may introduce conflicts between different regions in the image, if the section is not truly coronal or sagittal. A second approach is to project the fUS image or volume into a 3D reference/template atlas and find the best fit, which allows for the registration of more complex planes but also increases the complexity of the process and poses computational issues. Acquiring a reference volume for each animal before experiments is gaining popularity to mitigate inter-individual variability and ensure automatic registration onto this template, requiring a single registration per animal [Nouhoum et al 2021].

Conceptual Challenges

Physiological basis of the fUS signal

Previous studies have established that the fUS signal arises from ultrasound echoes generated by echogenic particles moving at different speeds along different orientations over a typical time window of 200 milliseconds (the duration of a rat’s cardiac cycle). In practice, the fUS signal is influenced by multiple factors: number and size of vessels contained in a voxel, vessel orientation, scatterers’ velocity and variations in vessel diameter. These parameters are not directly accessible and influence each other, meaning that absolute values of CBV and CBF are difficult to estimate. However, once a baseline image has been acquired, the number, size and orientation of vessels can be considered constant. Upon local vasodilation or constriction, only red blood cell (RBC) speed and changes in vessel diameter influence the fUS signal. These two parameters (RBC speed and diameter change) affect the Doppler spectrum differently: 1 - Variations in RBC velocity shift the mean value of the Doppler spectrum (leaving its global power unaffected), a parameter used to build Color Doppler images. 2- Variations in vessel diameter change the number of scatterers inside a voxel and directly increase or decrease the full energy of the Doppler spectrum, a parameter used to build Power Doppler images. Importantly, this is the case because most vessels are smaller than the size of a voxel, otherwise vessel diameter changes would affect several voxels, but not a single one.

A recent study using concurrent recordings of neural activity, individual blood vessel dynamics and functional ultrasound signal in vivo demonstrated that fUS signal can be predicted from calcium recordings and single vessel hemodynamic through robust transfer functions in a wide set of stimulation paradigms, thus establishing the neural and vascular underpinnings of the fUS signal [Aydin et al 2020]. This nicely complements another study [Boido et al 2019] by the same group where they acquired fMRI signal, fUS signal and single vessel dynamics in the same animal in response to different odors. Importantly, they found short time lags (on the order of the second) for vascular responses measured by two-photon laser-scanning microscopy (TPLSM) and fUS, whereas BOLD responses were found to be slower and peaked later on the order of tens of seconds. These two studies, though limited to the olfactory bulb of anesthetized animals, clearly establish the transfer functions between neural activity and single vessel hemodynamics and the fUS signal. Additional work is required to establish the same transfer functions in other structures, ideally in awake animals.

Relation with BOLD-fMRI studies

The fact that increased neural activity is responsible for subsequent increases in local cerebral blood flow – the so-called phenomenon of functional hyperemia – has been demonstrated in seminal works in the late 19th century [Mosso, 1880; Roy & Sherington 1890]. Since then, concurrent with the advent of fMRI as the gold-standard in neuroimaging, there has been a major effort to describe its mechanisms. One key question is whether brain hemodynamics reflect synaptic activity or firing rate of local neurons. Studies conducted in the primary visual cortex of monkeys demonstrated that positive BOLD signals tightly correlate with local field potential (LFP) recordings while spiking activity was either absent or reduced [Mathiesen et al. 1998, Logothetis et al. 2001].

A second line of research has focused on the frequency-specificity of the LFP signals preceding hemodynamic activation. Most studies have reported that fast synchronized activity – namely gamma oscillations – provide the best correlations with brain hemodynamics and that gamma band activity could be used as a regressor to reliably predict the subsequent BOLD responses. This was first observed in the primary visual cortex of anesthetized monkeys [Logothetis 2001] and consistent findings were found in the anesthetized cat’s visual cortex where the coupling between hemodynamic response amplitude and LFP was strongest for trials containing sustained fast gamma oscillations [Niessing et al. 2005]. Mateo and colleagues then demonstrated that optogenetically-elicited gamma oscillations were sufficient to entrain arteriole diameter change and generate pO2 changes that were detectable in the BOLD signal in awake mice [Mateo et al. 2017]. This finding suggests that the “default-mode network” (DMN) could indeed arise from variations in gamma-band activity between synaptically connected regions [Drew et al. 2020].

As of today, it is hard to infer neural activity from vascular data. The quest for a ‘transfer function’ or canonical ‘hemodynamic response’ between neuronal activity and brain hemodynamics is complex because anesthesia, which is often a requirement for BOLD-fMRI studies in animals, is known to strongly affect hemodynamics [Pisauro et al. 2013, Gao et al. 2017]. Another significant obstacle comes from the fact that NVC is known to be brain-region dependent [Devonshire et al, 2010] like in the primary motor cortex of rodents which shows an inverse relationship between LFP and cerebral blood flow from that of neighboring cortices [Huo et al. 2014, Bergel et al. 2020]. Functional Ultrasound solves both issues at once. Its ease-of-use and lightweight head-mounted probe allows for an easy ‘plug-and-play’ approach in a wide range of species, circumventing the need for anesthesia and allowing large-scale imaging during spontaneous behavior such as spontaneous rest, foraging, complex cognitive tasks, sleep and even running. The wider adoption of the fUS-ephys approach would considerably accelerate our mechanistic understanding of neurovascular interactions in both health and disease.

Future Directions

This review highlights that ultrasound imaging can now be concerned as versatile and non-invasive technology with significant potential for future innovations. In the coming years, advancements in ultrasound techniques may enable us to uncover the internal structures of individuals and populations by applying deep learning methods. Neuroscientists might utilize real-time neurofeedback to investigate the causal relationships between these internal states and modify brain pattern dynamics accordingly. At a functional level, these approaches aim to bridge neuro-behavioral temporal timescales, focusing on hierarchically nested structures that connect micro (milliseconds), meso (minutes), and macro (hours) scales. Additionally, this research on ultrasound imaging may link brain states (including sleep) to bodily states (including physical exercises), emphasizing the interactions among the brain, heart, gut, and immune system. A key area of investigation is understanding how internal brain states relate to individual subjective experiences in humans and animals.

Aside from this structural level of innovation, the sonogenetic approach stands out. This method uses ultrasound to stimulate or manipulate cells, like optogenetics but employing sound waves instead of light. It could facilitate the targeted delivery of therapeutic agents, enhancing precision in genetic activation for specific outcomes, such as drug release or initiating biological processes. These advancements will require the exploration of volumetric imaging, adding a temporal dimension to achieve 4D imaging in real-time. Future developments aim to push the boundaries of high-resolution. Additionally, molecular imaging presents a promising opportunity to visualize biological processes at the molecular level through ultrasound, allowing for real-time tracking of these processes to dynamically evaluate the effectiveness of therapies [for review, see Heiles et al. 2021]

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101023337 (AB).

References

- Aaslid, R.; Markwalder, T.-M.; Nornes, H. Noninvasive transcranial Doppler ultrasound recording of flow velocity in basal cerebral arteries. J. Neurosurg. 1982, 57, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, M.B.; Orger, M.B.; Robson, D.N.; Li, J.M.; Keller, P.J. Whole-brain functional imaging at cellular resolution using light-sheet microscopy. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergel, A.; Deffieux, T.; Demené, C.; Tanter, M.; Cohen, I. Local hippocampal fast gamma rhythms precede brain-wide hyperemic patterns during spontaneous rodent REM sleep. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergel, A.; Tiran, E.; Deffieux, T.; Demené, C.; Tanter, M.; Cohen, I. Adaptive modulation of brain hemodynamics across stereotyped running episodes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, H. Über das elektrenkephalogramm des menschen. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 1929, 87, 527–570. [Google Scholar]

- Bimbard, C.; Demene, C.; Girard, C.; Radtke-Schuller, S.; Shamma, S.; Tanter, M.; Boubenec, Y. Multi-scale mapping along the auditory hierarchy using high-resolution functional UltraSound in the awake ferret. eLife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaize, K.; Arcizet, F.; Gesnik, M.; Ahnine, H.; Ferrari, U.; Deffieux, T.; Pouget, P.; Chavane, F.; Fink, M.; Sahel, J.-A.; et al. Functional ultrasound imaging of deep visual cortex in awake nonhuman primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 14453–14463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunner, C.; Denis, N.L.; Gertz, K.; Grillet, M.; Montaldo, G.; Endres, M.; Urban, A. Brain-wide continuous functional ultrasound imaging for real-time monitoring of hemodynamics during ischemic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2024, 44, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claron, J.; Hingot, V.; Rivals, I.; Rahal, L.; Couture, O.; Deffieux, T.; Tanter, M.; Pezet, S. Large-scale functional ultrasound imaging of the spinal cord reveals in-depth spatiotemporal responses of spinal nociceptive circuits in both normal and inflammatory states. Pain 2021, 162, 1047–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claron, J.; Provansal, M.; Salardaine, Q.; Tissier, P.; Dizeux, A.; Deffieux, T.; Picaud, S.; Tanter, M.; Arcizet, F.; Pouget, P. Co-variations of cerebral blood volume and single neurons discharge during resting state and visual cognitive tasks in non-human primates. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claron, J.; Royo, J.; Arcizet, F.; Deffieux, T.; Tanter, M.; Pouget, P. Covariations between pupil diameter and supplementary eye field activity suggest a role in cognitive effort implementation. PLOS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deffieux, T.; Demene, C.; Pernot, M.; Tanter, M. Functional ultrasound neuroimaging: a review of the preclinical and clinical state of the art. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2018, 50, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demene, C.; Baranger, J.; Bernal, M.; Delanoe, C.; Auvin, S.; Biran, V.; Alison, M.; Mairesse, J.; Harribaud, E.; Pernot, M.; et al. Functional ultrasound imaging of brain activity in human newborns. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demene, C.; Deffieux, T.; Pernot, M.; Osmanski, B.-F.; Biran, V.; Gennisson, J.-L.; Sieu, L.-A.; Bergel, A.; Franqui, S.; Correas, J.-M.; et al. Spatiotemporal Clutter Filtering of Ultrafast Ultrasound Data Highly Increases Doppler and fUltrasound Sensitivity. IEEE Trans. Med Imaging 2015, 34, 2271–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devonshire, I.M.; Papadakis, N.G.; Port, M.; Berwick, J.; Kennerley, A.J.; Mayhew, J.E.; Overton, P.G. Neurovascular coupling is brain region-dependent. NeuroImage 2012, 59, 1997–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizeux, A.; Gesnik, M.; Ahnine, H.; Blaize, K.; Arcizet, F.; Picaud, S.; Sahel, J.-A.; Deffieux, T.; Pouget, P.; Tanter, M. Functional ultrasound imaging of the brain reveals propagation of task-related brain activity in behaving primates. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drew, P.J.; Mateo, C.; Turner, K.L.; Yu, X.; Kleinfeld, D. Ultra-slow Oscillations in fMRI and Resting-State Connectivity: Neuronal and Vascular Contributions and Technical Confounds. Neuron 2020, 107, 782–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, J.; Tiran, E.; Deffieux, T.; Tanter, M.; Lenkei, Z. Functional imaging evidence for task-induced deactivation and disconnection of a major default mode network hub in the mouse brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 15270–15280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-R.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Winder, A.T.; Liang, Z.; Antinori, L.; Drew, P.J.; Zhang, N. Time to wake up: Studying neurovascular coupling and brain-wide circuit function in the un-anesthetized animal. NeuroImage 2017, 153, 382–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiles, B.; Terwiel, D.; Maresca, D. The Advent of Biomolecular Ultrasound Imaging. Neuroscience 2021, 474, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, B.-X.; Smith, J.B.; Drew, P.J. Neurovascular Coupling and Decoupling in the Cortex during Voluntary Locomotion. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 10975–10981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbault, M.; Chauvet, D.; Gennisson, J.-L.; Capelle, L.; Tanter, M. Intraoperative Functional Ultrasound Imaging of Human Brain Activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert T, Niknejad HR, Kil D, Brunner C, Nuttin B, Montaldo G, Urban A. Functional ultrasound imaging and neuronal activity: how accurate is the spatiotemporal match? bioRxiv: 2024.07.10.602912, 2024.

- Lecrux, C.; Hamel, E. Neuronal networks and mediators of cortical neurovascular coupling responses in normal and altered brain states. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logothetis, N.K.; Pauls, J.; Augath, M.; Trinath, T.; Oeltermann, A. Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature 2001, 412, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macé, E.; Montaldo, G.; Cohen, I.; Baulac, M.; Fink, M.; Tanter, M. Functional ultrasound imaging of the brain. Nat. Methods 2011, 8, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mace, E.; Montaldo, G.; Osmanski, B.-F.; Cohen, I.; Fink, M.; Tanter, M. Functional ultrasound imaging of the brain: theory and basic principles. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2013, 60, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macé. ; Montaldo, G.; Trenholm, S.; Cowan, C.; Brignall, A.; Urban, A.; Roska, B. Whole-Brain Functional Ultrasound Imaging Reveals Brain Modules for Visuomotor Integration. Neuron 2018, 100, 1241–1251.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paz, J.M.M.; Macé, E. Functional ultrasound imaging: A useful tool for functional connectomics? NeuroImage 2021, 245, 118722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matei, M.; Bergel, A.; Pezet, S.; Tanter, M. Global dissociation of the posterior amygdala from the rest of the brain during REM sleep. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo, C.; Knutsen, P.M.; Tsai, P.S.; Shih, A.Y.; Kleinfeld, D. Entrainment of Arteriole Vasomotor Fluctuations by Neural Activity Is a Basis of Blood-Oxygenation-Level-Dependent “Resting-State” Connectivity. Neuron 2017, 96, 936–948.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiesen, C.; Caesar, K.; Akgören, N.; Lauritzen, M. Modification of activity-dependent increases of cerebral blood flow by excitatory synaptic activity and spikes in rat cerebellar cortex. J. Physiol. 1998, 512, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikula, S.; Trotts, I.; Stone, J.M.; Jones, E.G. Internet-enabled high-resolution brain mapping and virtual microscopy. NeuroImage 2007, 35, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaldo, G.; Urban, A.; Macé, E. Functional Ultrasound Neuroimaging. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 45, 491–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosso, A. Sulla circolazione del sangue nel cervello dell’uomo : ricerche sfigmografiche [Online]. Royal College of Surgeons of England. Roma : Coi tipi del Salviucci. http://archive.org/details/b2239347x [12 Sep. 2016].

- Niessing, J.; Ebisch, B.; Schmidt, K.E.; Niessing, M.; Singer, W.; Galuske, R.A.W. Hemodynamic Signals Correlate Tightly with Synchronized Gamma Oscillations. Science 2005, 309, 948–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouhoum, M.; Ferrier, J.; Osmanski, B.-F.; Ialy-Radio, N.; Pezet, S.; Tanter, M.; Deffieux, T. A functional ultrasound brain GPS for automatic vascular-based neuronavigation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunez-Elizalde, A.O.; Krumin, M.; Reddy, C.B.; Montaldo, G.; Urban, A.; Harris, K.D.; Carandini, M. Neural correlates of blood flow measured by ultrasound. Neuron 2022, 110, 1631–1640.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, S.; Lee, T.M.; Kay, A.R.; Tank, D.W. Brain magnetic resonance imaging with contrast dependent on blood oxygenation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1990, 87, 9868–9872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, E.A.; Leergaard, T.B.; Calabrese, E.; Johnson, G.A.; Bjaalie, J.G. Waxholm Space atlas of the Sprague Dawley rat brain. NeuroImage 2014, 97, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paxinos, G.; Watson, C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates; Academic Press, 1982.

- Pisauro, M.A.; Dhruv, N.T.; Carandini, M.; Benucci, A. Fast Hemodynamic Responses in the Visual Cortex of the Awake Mouse. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 18343–18351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabut, C.; Correia, M.; Finel, V.; Pezet, S.; Pernot, M.; Deffieux, T.; Tanter, M. 4D functional ultrasound imaging of whole-brain activity in rodents. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 994–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabut, C.; Ferrier, J.; Bertolo, A.; Osmanski, B.; Mousset, X.; Pezet, S.; Deffieux, T.; Lenkei, Z.; Tanter, M. Pharmaco-fUS: Quantification of pharmacologically-induced dynamic changes in brain perfusion and connectivity by functional ultrasound imaging in awake mice. NeuroImage 2020, 222, 117231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahal, L.; Thibaut, M.; Rivals, I.; Claron, J.; Lenkei, Z.; Sitt, J.D.; Tanter, M.; Pezet, S. Ultrafast ultrasound imaging pattern analysis reveals distinctive dynamic brain states and potent sub-network alterations in arthritic animals. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, C.S.; Sherrington, C.S. On the Regulation of the Blood-supply of the Brain. J. Physiol. 1890, 11, 85–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sans-Dublanc, A.; Chrzanowska, A.; Reinhard, K.; Lemmon, D.; Nuttin, B.; Lambert, T.; Montaldo, G.; Urban, A.; Farrow, K. Optogenetic fUSI for brain-wide mapping of neural activity mediating collicular-dependent behaviors. Neuron 2021, 109, 1888–1905.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejnowski, T.J.; Churchland, P.S.; Movshon, J.A. Putting big data to good use in neuroscience. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 1440–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieu, L.-A.; Bergel, A.; Tiran, E.; Deffieux, T.; Pernot, M.; Gennisson, J.-L.; Tanter, M.; Cohen, I. EEG and functional ultrasound imaging in mobile rats. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 831–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanter, M.; Bercoff, J.; Athanasiou, A.; Deffieux, T.; Gennisson, J.-L.; Montaldo, G.; Muller, M.; Tardivon, A.; Fink, M. Quantitative Assessment of Breast Lesion Viscoelasticity: Initial Clinical Results Using Supersonic Shear Imaging. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2008, 34, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanter, M.; Fink, M. Ultrafast imaging in biomedical ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2014, 61, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Takahashi, D.Y.; El Hady, A.; Liao, D.A.; Ghazanfar, A.A. Active neural coordination of motor behaviors with internal states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2201194119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Ma, X.; Deng, W.; Zhang, J.; Tang, S.; Pak, O.S.; Zhu, L.; Criado-Hidalgo, E.; Gong, C.; Karshalev, E.; et al. Imaging-guided bioresorbable acoustic hydrogel microrobots. Sci. Robot. 2024, 9, eadp3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).