Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

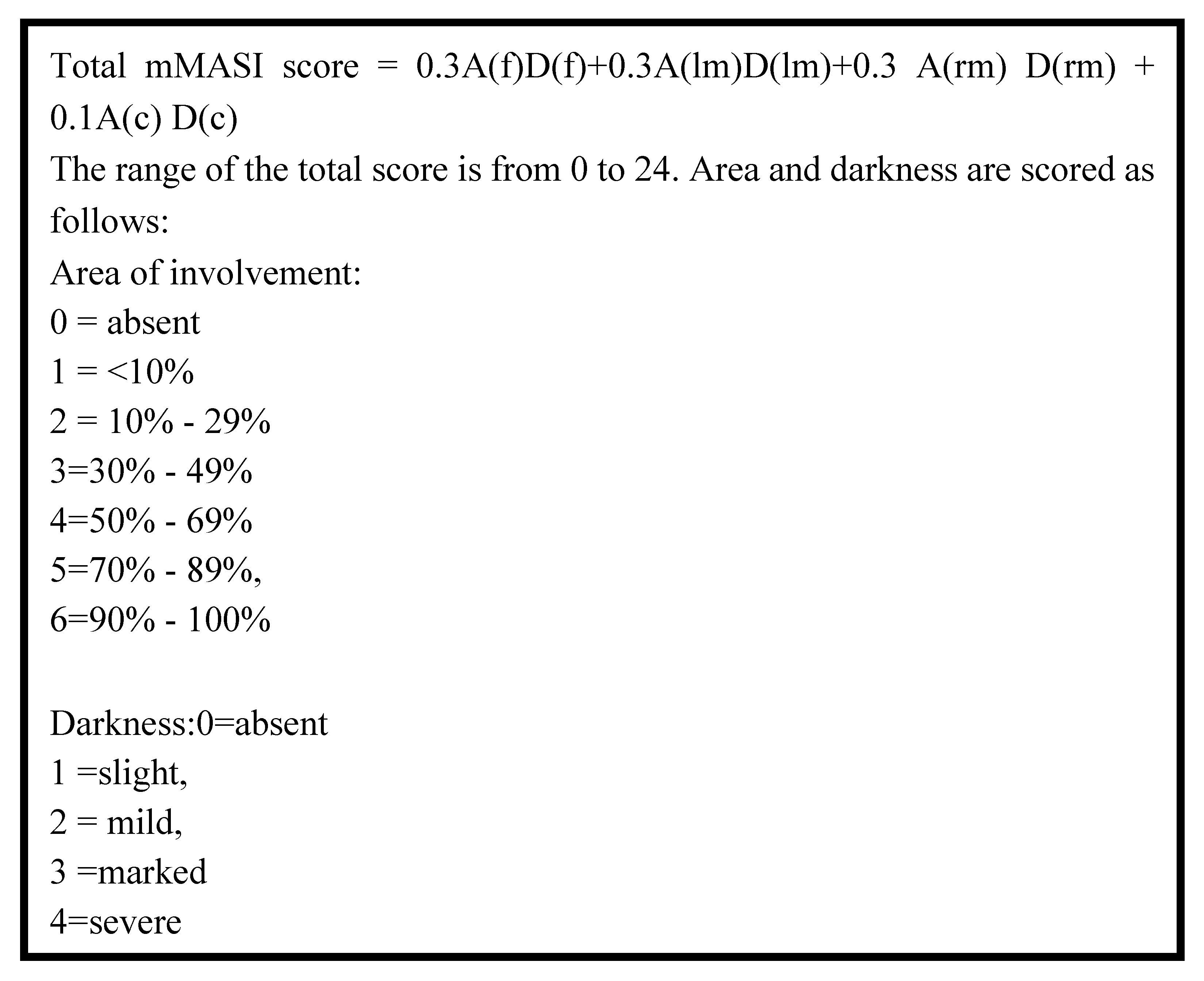

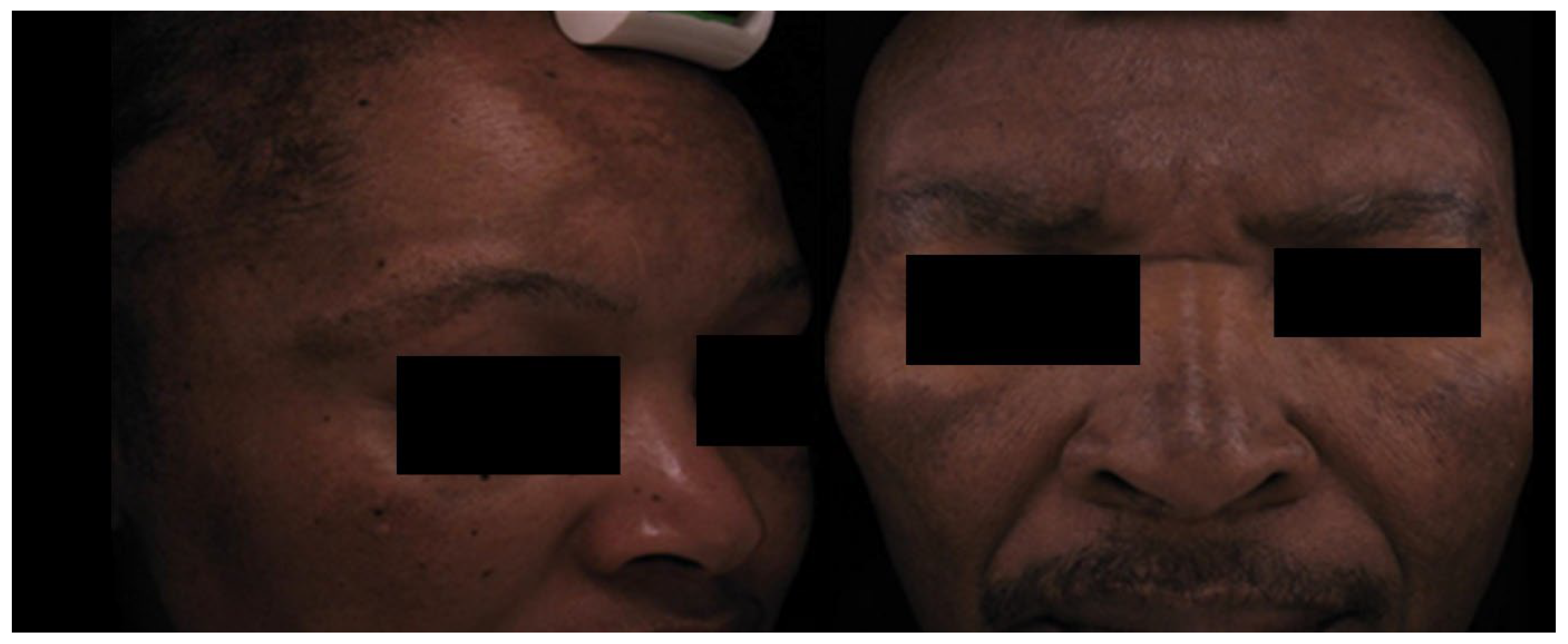

Melasma is a chronic skin disorder characterized by hypermelanosis, predominantly affecting women of African descent. This study explores the association between genetic variants of the genes SLC45A2, TYR, HERC2, and SLC24A and the severity of melasma in women of reproductive age with darker skin types. Forty participants were divided into two groups: 20 with facial melasma and 20 without. DNA was extracted from blood samples and genotyped using TaqMan assays to determine allele frequencies and genotype distributions. Statistical analyses, including Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium tests and odds ratios, were conducted to evaluate the associations between SNPs and melasma severity. The results showed significant differences in allelic frequencies of rs1042602 SNP (TYR gene) for codominant alleles [AA vs CC; (OR=21.00; 95% Cl (1.799–284.1); adjusted p=0.0320*); AC vs CC (OR= 56.00; 95%Cl (6.496–618.4); adjusted p<0.0001****)]; recessive alleles [(AA+AC vs CC; adjusted p<00001****)] and over dominant alleles [(AA+CC vs AC: adjusted p=0.0449)] between the melasma and control groups. There was significant differences in distribution frequencies for genotypes CC vs CT [(OR= 46.75; 95% Cl (5.786–270.8); adjusted p<0.0001****)]; and dominant alleles [(CC vs CT+TT; adjusted p=0.0022**)], recessive alleles [(CC+CT vs TT: adjusted p=0.0436*)] and over dominant alleles [(CC+TT vs TC: adjusted p <0.0001****)] between the two groups for the rs1129038 SNP (HERC2 gene). Additionally, there was significant association of codominant alleles AA vs GG [(OR=0.03571; 95% Cl (0.005866–0.3303); adjusted p=0.0010**] and AA vs AG [(OR= 0.05714; 95% Cl (0.01078 –0.3499); adjusted p=0.0022**)] and for recessive alleles AA+AG vs GG (adjusted p=0.0002***) in the rs1426654 SNP (SLC24A gene) in both groups. These findings form this study underscores the necessity for tailored treatment approaches that take genetic variations into account.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Clinical Features

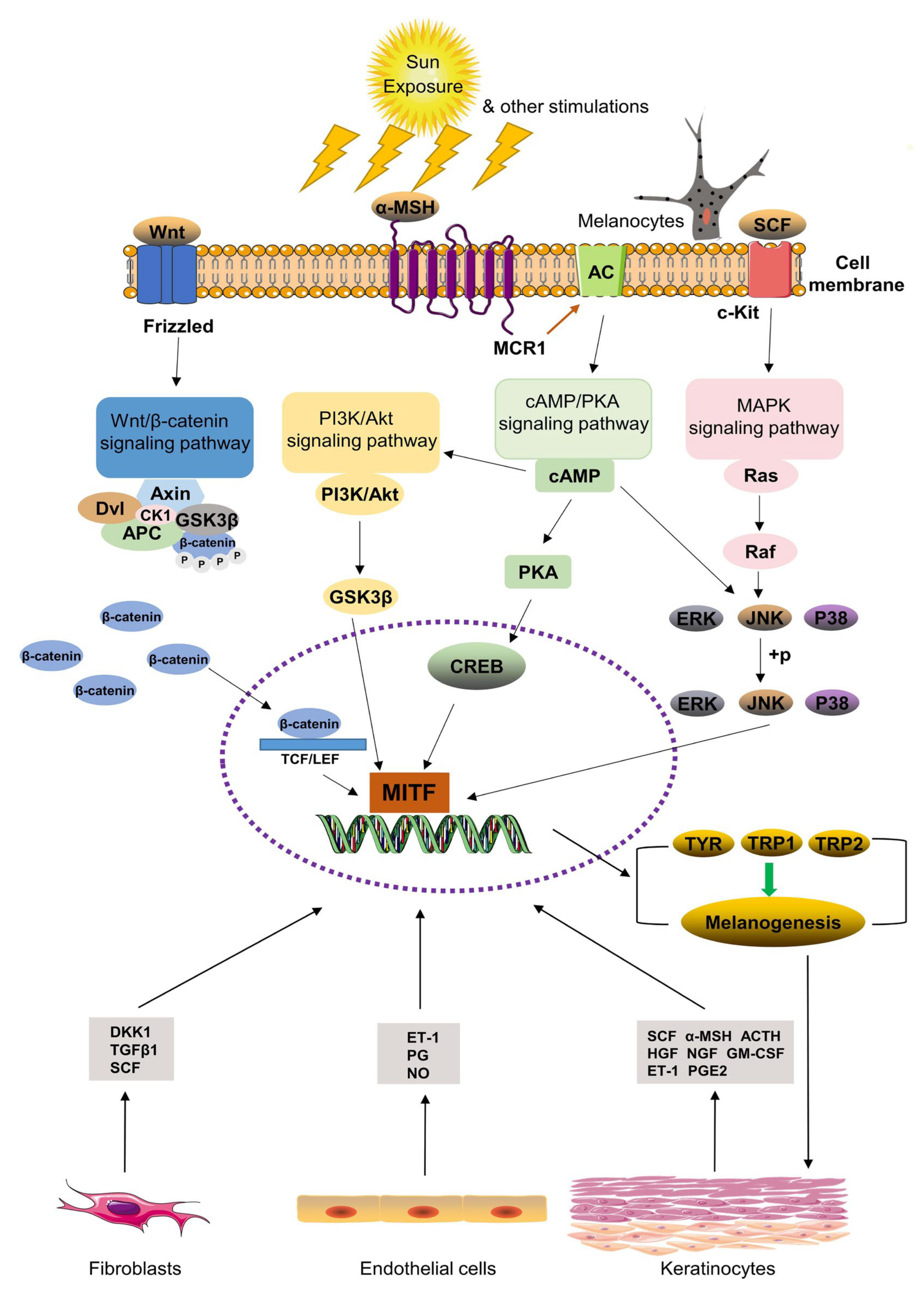

Key Molecular Pathways in Melasma

2. Results

Melasma vs Control Groups

3. Discussion

Limitations and Significance of the Study

4. Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

Study Participants and Clinical Examination

DNA Extraction and Genotyping

Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D’Elia, M.P.B. , et al. , African ancestry is associated with facial melasma in women: a cross-sectional study. BMC medical genetics 2017, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mpofana, N.; Chibi, B.; Visser, T.; Paulse, M.; Finlayson, A.J.; Ghuman, S.; Gqaleni, N.; Hussein, A.A.; Dlova, N.C. Treatment of Melasma on Darker Skin Types: A Scoping Review. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, I. and S. Journal of Skin and Stem Cell 2021, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Espósito, A.C.C. , et al. , Update on melasma—Part I: pathogenesis. Dermatology and Therapy 2022, 12, 1967–1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hernando, B.; Ibarrola-Villava, M.; Fernandez, L.P.; Peña-Chilet, M.; Llorca-Cardeñosa, M.; Oltra, S.S.; Alonso, S.; Boyano, M.D.; Martinez-Cadenas, C.; Ribas, G. Sex-specific genetic effects associated with pigmentation, sensitivity to sunlight, and melanoma in a population of Spanish origin. Biol. Sex Differ. 2016, 7, 17–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofana, N.; Abrahamse, H. The Management of Melasma on Skin Types V and VI Using Light Emitting Diode Treatment. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2018, 36, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, A.G.; Hynan, L.S.; Bhore, R.; Riley, F.C.; Guevara, I.L.; Grimes, P.; Nordlund, J.J.; Rendon, M.; Taylor, S.; Gottschalk, R.W.; et al. Reliability assessment and validation of the Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) and a new modified MASI scoring method. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 64, 78–83.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamega, A.; Miot, L.; Bonfietti, C.; Gige, T.; Marques, M.; Miot, H. Clinical patterns and epidemiological characteristics of facial melasma in Brazilian women. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2012, 27, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.Y.; Bahadoran, P.; Suzuki, I.; Zugaj, D.; Khemis, A.; Passeron, T.; Andres, P.; Ortonne, J. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy detects pigmentary changes in melasma at a cellular level resolution. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, e228–e233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofana, N. , Effectiveness of Light Emitting Diode Treatment for Melasma on Skin Types V-VI. 2017: University of Johannesburg (South Africa).

- Hexsel, D. , et al. , Epidemiology of melasma in B razilian patients: a multicenter study. International journal of dermatology 2014, 53, 440–444. [Google Scholar]

- Amatya, B. Evaluation of Dermoscopic Features in Facial Melanosis with Wood Lamp Examination. Dermatol. Pr. Concept. 2022, 12, e2022030–e2022030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathi, S.K.; Achar, A. Melasma: A clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J. Dermatol. 2011, 56, 380–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddaleno, A.S.; Camargo, J.; Mitjans, M.; Vinardell, M.P. Melanogenesis and Melasma Treatment. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, S.A. , et al. , Signaling pathways in melanogenesis. International journal of molecular sciences 2016, 17, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passeron, T. and M. Picardo, Melasma, a photoaging disorder. Pigment cell & melanoma research 2018, 31, 461–465. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W., Q. Chen, and Y. Xia, New mechanistic insights of melasma. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology 2023, 429–442.

- Roider, E.; Lakatos, A.I.T.; McConnell, A.M.; Wang, P.; Mueller, A.; Kawakami, A.; Tsoi, J.; Szabolcs, B.L.; Ascsillán, A.A.; Suita, Y.; et al. MITF regulates IDH1, NNT, and a transcriptional program protecting melanoma from reactive oxygen species. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, J.J.; Fisher, D.E. The roles of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor and pigmentation in melanoma. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 563, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, A.; Fisher, D.E. The master role of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor in melanocyte and melanoma biology. Lab. Investig. 2017, 97, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiriyasermkul, P.; Moriyama, S.; Nagamori, S. Membrane transport proteins in melanosomes: Regulation of ions for pigmentation. 1862, 1833; 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.; Kayser, M.; Palstra, R.-J. HERC2 rs12913832 modulates human pigmentation by attenuating chromatin-loop formation between a long-range enhancer and the OCA2 promoter. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Koofee, D.A. and S.M. Mubarak, Genetic polymorphisms. The Recent Topics in Genetic Polymorphisms, 2019, 1-10.

- Sherry, S.T.; Ward, M.; Sirotkin, K. dbSNP—Database for Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Other Classes of Minor Genetic Variation. Genome Res. 1999, 9, 677–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, O., N. Khan, and A. Ullah, Unlocking Rare Diseases Genetics: Insights from Genome-Wide Association Studies and Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. International Journal of Molecular Microbiology 2024, 7, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bin, B.-H.; Bhin, J.; Yang, S.H.; Shin, M.; Nam, Y.-J.; Choi, D.-H.; Shin, D.W.; Lee, A.-Y.; Hwang, D.; Cho, E.-G.; et al. Membrane-Associated Transporter Protein (MATP) Regulates Melanosomal pH and Influences Tyrosinase Activity. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0129273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. Association of pigmentation related-genes polymorphisms and geographic environmental variables in the Chinese population. Hereditas 2021, 158, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fracasso, N.C.d.A.; de Andrade, E.S.; Wiezel, C.E.V.; Andrade, C.C.F.; Zanão, L.R.; da Silva, M.S.; Marano, L.A.; Donadi, E.A.; Castelli, E.C.; Simões, A.L.; et al. Haplotypes from the SLC45A2 gene are associated with the presence of freckles and eye, hair and skin pigmentation in Brazil. Leg. Med. 2017, 25, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorgaleleh, S.; Naghipoor, K.; Barahouie, A.; Dastaviz, F.; Oladnabi, M. Molecular and biochemical mechanisms of human iris color: A comprehensive review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 8972–8982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.; Escobar, I.E.; Ho, T.; Lefkovith, A.J.; Latteri, E.; Haltaufderhyde, K.D.; Dennis, M.K.; Plowright, L.; Sviderskaya, E.V.; Bennett, D.C.; et al. SLC45A2 protein stability and regulation of melanosome pH determine melanocyte pigmentation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2020, 31, 2687–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.L. , et al. , Analysis of cultured human melanocytes based on polymorphisms within the SLC45A2/MATP, SLC24A5/NCKX5, and OCA2/P loci. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2009, 129, 392–405. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, Y.; Tamiya, G.; Nakamura, T.; Hozumi, Y.; Suzuki, T. Association of melanogenesis genes with skin color variation among Japanese females. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2012, 69, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudjashov, G.; Villems, R.; Kivisild, T. Global Patterns of Diversity and Selection in Human Tyrosinase Gene. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e74307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bitsue, H.K.; Yang, Z. Skin colour: A window into human phenotypic evolution and environmental adaptation. Mol. Ecol. 2024, 33, e17369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, S. , et al. , Direct evidence for positive selection of skin, hair, and eye pigmentation in Europeans during the last 5,000 y. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 4832–4837. [Google Scholar]

- GENE, Z.G. , Oral Presentations (OP001–OP129). Cell. Biol 2003, 23, 5245–5255. [Google Scholar]

- Durso, D.F.; Bydlowski, S.P.; Hutz, M.H.; Suarez-Kurtz, G.; Magalhães, T.R.; Pena, S.D.J. Association of Genetic Variants with Self-Assessed Color Categories in Brazilians. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e83926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainger, S.A.; Jagirdar, K.; Lee, K.J.; Soyer, H.P.; Sturm, R.A. Skin Pigmentation Genetics for the Clinic. Dermatology 2017, 233, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokowski, R.P.; Pant, P.K.; Dadd, T.; Fereday, A.; Hinds, D.A.; Jarman, C.; Filsell, W.; Ginger, R.S.; Green, M.R.; van der Ouderaa, F.J.; et al. A Genomewide Association Study of Skin Pigmentation in a South Asian Population. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 1119–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Sturm, R.; Duffy, D.L. Human pigmentation genes under environmental selection. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarrola-Villava, M.; Hu, H.-H.; Guedj, M.; Fernandez, L.P.; Descamps, V.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Bagot, M.; Benssussan, A.; Saiag, P.; Fargnoli, M.C.; et al. MC1R, SLC45A2 and TYR genetic variants involved in melanoma susceptibility in Southern European populations: Results from a Meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 2183–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, H.; Kraft, P.; Hunter, D.J.; Han, J. Genetic variants in pigmentation genes, pigmentary phenotypes, and risk of skin cancer in Caucasians. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aponte, J.L.; Chiano, M.N.; Yerges-Armstrong, L.M.; A Hinds, D.; Tian, C.; Gupta, A.; Guo, C.; Fraser, D.J.; Freudenberg, J.M.; Rajpal, D.K.; et al. Assessment of rosacea symptom severity by genome-wide association study and expression analysis highlights immuno-inflammatory and skin pigmentation genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 2762–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, C. , Elucidating the mechanisms or interactions involved in differing hair color follicles. 2016, Purdue University.

- Dimisianos, G.; Stefanaki, I.; Nicolaou, V.; Sypsa, V.; Antoniou, C.; Poulou, M.; Papadopoulos, O.; Gogas, H.; Kanavakis, E.; Nicolaidou, E.; et al. A study of a single variant allele (rs1426654) of the pigmentation-related gene SLC24A5 in Greek subjects. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 18, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonnalagadda, M.; Faizan, M.A.; Ozarkar, S.; Ashma, R.; Kulkarni, S.; Norton, H.L.; Parra, E. A Genome-Wide Association Study of Skin and Iris Pigmentation among Individuals of South Asian Ancestry. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019, 11, 1066–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, F.d.A.; Gonçalves, F.d.T.; Fridman, C. SLC24A5 and ASIP as phenotypic predictors in Brazilian population for forensic purposes. Leg. Med. 2015, 17, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, R. , et al. , Prediction model validation: normal human pigmentation variation. J Forensic Res 2011, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jonnalagadda, M.; Norton, H.; Ozarkar, S.; Kulkarni, S.; Ashma, R. Association of genetic variants with skin pigmentation phenotype among populations of west Maharashtra, India. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2016, 28, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, C. , et al. Skin Pigmentation. Nova Science Publishers 2013, 89–119. [Google Scholar]

- Lamason, R.L.; Mohideen, M.-A.P.; Mest, J.R.; Wong, A.C.; Norton, H.L.; Aros, M.C.; Jurynec, M.J.; Mao, X.; Humphreville, V.R.; Humbert, J.E.; et al. SLC24A5, a Putative Cation Exchanger, Affects Pigmentation in Zebrafish and Humans. Science 2005, 310, 1782–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Pathway Influence | Role in Melanogenesis | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLC45A2 | Melanin synthesis and transport | Maintains melanosome pH; essential for tyrosinase activity; mutations lead to reduced pigmentation (OCA4) | 21 |

| TYR | Melanin biosynthesis | Encodes tyrosinase, the key enzyme for melanin biosynthesis; mutations affect pigmentation levels | 18 |

| HERC2 | Regulates OCA2 expression | Regulates OCA2 expression; The interaction between HERC2 and OCA2 influences melanosome function (affects melanosomal pH) function and pigmentation traits (overall melanin production) | 22 |

| SLC24A5 | Melanosome maturation | Involved in ion transport for melanosome maturation and sensitivity to UV exposure | 21 |

| Characteristics | Melasma group (n=20) |

Control group (n=20) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years); (mean± standard deviation) | 36–63; (47.25 ± 7.99) | 35–58; (46.80 ± 7.52) |

|

History of pregnacy and number of children Children (%) Yes No |

16 (84.21%) 3 (15.79%) |

12 8 |

|

Use of Contracptives/hormone therapy (n; %) Yes No |

20 (100%) 0 (0%) |

20 (100%) 0 (%) |

| Malar | 2 (10%) | - |

| Cetrofacial | 9 (45%) | - |

| Manibular | 9 (45%) | - |

|

Duration of melasma (%) 2 years 5 years 10 years More than 10 years |

5 (25%) 7 (35%) 4 (20%) 4 (20%) |

- |

|

Family history (first degree relative) Yes No |

12 (60%) 8 (40%) |

- |

| mMASI Score category | - | |

| Mild | 5 (25%) | - |

| Modertae | 7 (35%) | - |

| Severe | 8 (40%) | - |

| SNP ID | Patient | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Melasma group | Control group | ||

|

rs11568737 G>T |

|||

| Codominant | GG | 1 (5%) | 2 (10%) |

| GT | 8 (40%) | 2 (10%) | |

| TT | 11 (55%) | 16 (80%) | |

| Allele | G Major | 10 (25%) | 6 (15%) |

| T Minor | 30 (75%) | 36 (90%) | |

|

rs28777 A>C |

|||

| Codominant | AA | 2 (10%) | 6 (30%) |

| AC | 15 (75%) | 12 (60%) | |

| CC | 3 (15%) | 2 (10%) | |

| Allele | A Major | 19 (48%) | 24 (60%) |

| C Minor | 21 (53%) | 16 (40%) | |

|

rs1042602 A>C |

|||

| Codominant | AA | 3 (15%) | 2 (10%) |

| AC | 16 (80%) | 4 (20%) | |

| CC | 1 (5%) | 14 (70%) | |

| Allele | A Major | 22 (55%) | 8 (20%) |

| C Minor | 18 (45%) | 32 (80%) | |

|

rs1126809 G>A |

|||

| Codominant | GG | 15 (75%) | 14 (70%) |

| GA | 2 (10%) | 4 (20%) | |

| AA | 3 (15%) | 2 (10%) | |

| Allele | G Major | 33 (83%) | 30 (75%) |

| A Minor | 7 (18%) | 10 (25%) | |

|

rs1129038 C>T |

|||

| Codominant | CC | 11 (55%) | 2 (10%) |

| CT | 2 (10%) | 17 (85%) | |

| TT | 7 (35%) | 1 (5%) | |

| Allele | C Major | 24 (60%) | 21 (53%) |

| T Minor | 16 (40%) | 19 (48 %) | |

|

rs1426654 A>G |

|||

| Codominant | AA | 2 (10%) | 14 (70%) |

| AG | 10 (50%) | 4 (20%) | |

| GG | 8 (40%) | 2 (10%) | |

| Allele | A Major | 14 (35% | 32 (80%) |

| G Minor | 26 (65%) | 8 (20%) | |

| Allele | G Major | 10 (25%) | 6 (15%) |

| T Minor | 30 (75%) | 36 (90%) | |

| SNP | Melasma vs control OR (95% CI), p–value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

rs11568737 G>T Genotype |

||||

| Codominant | AA vs TT | 0.7273 (0.04641–6.922) p>0.9999 |

||

| GG vs GT | 0.1250 (0.007879–1.793) p=0.2028 |

|||

| GT vs TT | 5.818 (1.197–29.87) p=0.0625 |

|||

| Dominant | GG vs GT+TT | 0.5263 (0.03471–4.882) p>0.9999 |

||

| Recessive | GG+ GT vs TT | 3.682 (0.9184–12.49) p=0.0956 |

||

| Over dominant | AA+CC vs AC | 0.1667 (0.03278–0.8302) p=0.0648 |

||

|

Allele (Major vs minor) |

G vs T | 1.771 (0.5885–5.690) p=0.4066 |

||

|

rs28777 A>C Genotype |

||||

| Codominant | AA vs CC | 0.2222 (0.02725–1.978) p=0.2929 |

||

| AA vs AC | 0.2667 (0.04972–1.485) p=0.2285 |

|||

| AC vs CC | 0.9444 (0.1501–5.220) p>0.9999 |

|||

| Dominant | AA vs AC+CC | 0.2593 (0.04908–1.366) p=0.2351 |

||

| Recessive | AA+ AC vs CC | 0.1111 (0.02356–0.4805) p=0.0033** |

||

| Over dominant | AA+CC vs AC | 0.4412 (0.1185–1.707) p=0.3200 |

||

|

Allele (Major vs minor) |

A vs C | 0.6667 (0.2834–1.697) p=0.4949 |

||

|

rs1042602 A>C Genotype |

||||

| Codominant | AA vs CC | 21.00 (1.799–284.1) p=0.0320* |

||

| AA vs AC | 0.3750 (0.06110–2.784) p=0.5623 |

|||

| AC vs CC | 56.00 (6.496–618.4) p<0.0001**** |

|||

| Dominant | AA vs AC+CC | 1.412 (0.2581–8.679) p>0.9999 |

||

| Recessive | AA+AC vs CC | 44.33 (4.824–487.8) p<0.0001**** |

||

| Over dominant | AA+CC vs AC | 0.1667 (0.03149–0.9046) p=0.0449* |

||

|

Allele (Major vs minor) |

A vs C | 4.889 (1.882–13.78) p=0.0024** |

||

|

rs1126809 G>A Genotype |

||||

| Codominant | GG vs AA | 2.143 (0.4153–12.37) p=0.6581 |

||

| GG vs GA | 0.3571 (0.02590–2.718) p=0.6074 |

|||

| GA vs AA | 0.7500 (0.03569–11.03) p>0.9999 |

|||

| Dominant | GG vs GA+AA | 0.6429 (0.1501–3.368) p=0.7013 |

||

| Recessive | GG+GA vs AA | 2.250 (0.4530–12.80) p=0.6614 |

||

| Over dominant | GG+AA vs GA | 0.6296 (0.1032–3.432) p>0.9999 |

||

|

Allele (Major vs minor) |

G vs A | 1.473 (0.5158–4.004) p=0.5892 |

||

|

rs1129038 C>T Genotype |

||||

| Codominant | CC vs TT | 0.6111 (0.03839–6.044) p>0.9999 |

||

| CC vs CT | 46.75 (5.786 –270.8) p<0.0001**** |

|||

| CT vs TT | 0.2857 (0.01344–7.970) p=0.4909 |

|||

| Dominant | CC vs CT +TT | 12.38 (2.162–61.41) p=0.0022** |

||

| Recessive | CC+CT vs TT | 0.09774 (0.008320–0.7323) p=0.0436* |

||

| Over dominant | CC+TT vs CT | 51.00 (6.786–262.2) p<0.0001**** |

||

|

Allele (Major vs minor) |

C vs T | 1.357 (0.5434–3.117) p=0.6525 |

||

|

rs1426654 A>G Genotype |

||||

| Codominant | AA vs GG | 0.03571 (0.005866–0.3303) p=0.0010** |

||

| AA vs AG | 0.05714 (0.01078–0.3499) p=0.0022** |

|||

| AG vs GG | 0.6250 (0.1010–3.827) p>0.9999 |

|||

| Dominant | AA vs AG+GG | 0.1667 (0.03278–0.8302) p=0.0648 |

||

| Recessive | AA+ AG vs GG | 0.04762 (0.009685–0.2782) p=0.0002*** |

||

| Over dominant | AA+GG vs AG | 0.2500 (0.07356–1.000) p=0.0958 |

||

|

Allele (Major vs minor) |

A vs G | 0.1346 (0.05049–0.3585) p<0.0001**** |

||

| OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence Intervals; Asterisks (*) denote significance: ∗p<0.05 and ∗∗p<0.01 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).