1. Introduction

Recent advances in pharmaceutical technology have led to the development of nanopharmaceutics as a new innovative field (Souto et al. 2020) (Wang and Yang 2023). The advances of fundamental science put on the agenda the problem of the quality, efficacy and safety of nanopharmaceuticals for use in practical medicine (Bisso and Leroux 2020). To weigh the benefits and risks of their medical application, the most comprehensive examination of the biological activity of nanopharmaceuticals in vitro and in vivo must be performed. Minerals are good candidates as nanopharmaceuticals because they exhibit a wide variety of physicochemical properties and surface nanostructures that can be used to actively manipulate the biomolecules (Valdre et al. 2013) (Tan et al. 2021). Toxicity and long-term effects on genes are of particular importance especially for hardly biodegradable and difficult-to-remove nanodrugs (Cimen et al. 2024). Safety assessment is important not only in relation to patients, but also in relation to medical personnel and, more generally, to the environment. Inorganic nanoparticles remain in the environment for a long time and could affect humans and animals. In this case, inhalation is the main route of entry of nanoparticles into the human body.

Nanoscale cerium dioxide (nanoceria) is promising for biomedical application due to its ability to participate in reactions with ROS (Saifi et al. 2021). The metabolism of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is the very ancient regulatory mechanisms involved in the key processes in health and diseases (Sun et al. 2020). ROS are involved in cell proliferation and death, immune response, carcinogenesis, and inflammation (Sies and Jones 2020). Nanoceria is especially effective in scavenging the superoxide anion radical like superoxide dismutase (SOD), which makes it a promising anti-inflammatory agent and regulator of ROS metabolism (Tarnuzzer et al. 2005) (Korsvik et al. 2007). Next, its peroxidase-like (Ivanov et al. 2009), catalase-like (Pirmohamed et al. 2010), oxidase-like (Asati et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2016), and phosphatase-like activities (Yao et al. 2019) have been proven. Today, these nanozyme properties are complemented by the discovery of fundamentally new types of biochemical activity, including photolyase- (Tian et al. 2019), phospholipase- (K Khulbe et al. 2020), and nuclease-like (Xu et al. 2019) activities.

Despite the promising nanozyme effects, studies on gene expression are mainly performed using animal models (Cai et al. 2014) (Ould-Moussa et al. 2014) (Schwotzer et al. 2018) (Mohamed 2022). For human cells, the study of the toxicity of cerium dioxide for potential cancer treatment was carried out mostly on malignant cells: cultures of human lung cancer (Lin et al. 2006), hepatoma (Cheng et al. 2013), neuroblastoma (Kumari et al. 2014), lung adenocarcinoma (Mittal and Pandey 2014), skin melanoma (Ali et al. 2015), ovarian cancer (Vassie et al. 2017), leukemia cells (Montazeri et al. 2018), (Patel et al. 2018). To sum, nanoceria exhibits toxic properties towards cancer cells. On the other hand, nanoceria exhibits protective properties for normal cells, for example, as a neuroprotector (Das et al. 2007) or a protector of photoreceptors (Chen et al. 2006). There are numerous studies on non-tumor cells such as skin keratinocytes (Ngoc et al. 2019) and retinal pigment epithelial cells (Ma et al. 2021). Human embryonic lung fibroblasts present a useful in vitro model for toxicity studies due to their sensitivity and involvement in inflammation. Lord et al. (2016) studied effects of hyaluronan-coated nanoceria on these cells (Lord et al. 2016).

Citrate anion is widely used as a nanoparticle stabilizer (Andrade et al. 2022) (Arsalani et al. 2023) (Nimi et al. 2018). Though biological activity of ammonium citrate is low, when associated with nanoparticles it can significantly affect their toxicity. For example, silver nanoparticles stabilized with citrate are more toxic than nanoparticles stabilized with polyethylene glycol (Bastos et al. 2016). On the other hand, silver nanoparticles stabilized with citrate and polyethylene glycol showed comparable toxicity towards hepatoma cells (Bastos et al. 2017). The toxicity of citrate-stabilized nanoparticles is also affected by the method of preparation. (Park et al. 2014). Stabilization with citrate had various concentration-depending effects on gold nanoparticles (Epanchintseva et al. 2018) (Freese et al. 2012). For mouse fibroblasts, citrate-stabilized nanoceria was more toxic than polyacrylic acid coating (Ould-Moussa et al. 2014). All this indicates the need to study the effects of citrate on the properties of nanoparticles towards human cells.

To sum, nanoceria exhibits an exceptionally wide range of useful biomedical properties due to its ability to participate in reactions with ROS. Depending on the stabilizers, nanoceria can provide cytotoxic or cytoprotective properties. Here, we aimed to study the effects of citrate-coated nanoceria compared with bare nanoceria on oxidative metabolism genes in human embryonic lung fibroblasts by examining: (1) cell viability, (2) intracellular oxidative stress, (3) expression of NOX4, NRF2, and NF-κB, (4) oxidative DNA damage/repair, (5) cell proliferation, apoptosis, and autophagy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Citrate-Coated Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles

CeO2 nanoparticles modified with ammonium citrate was prepared with a two-step procedure. Pristine nanoscale CeO2 was synthesized with a thermal hydrolysis of ammonium hexanitratocerate(IV) (#215473, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) (Shcherbakov et al. 2017). Briefly, the precursor aqueous solution was kept at 95℃ for a day. The precipitate formed was washed at least three times with isopropanol and redispersed in deionized water. The residual amount of isopropanol was removed by boiling. This solution of unmodified nanoceria was used as a reference sample to identify the effects of citrate stabilizer. The modifier solution was prepared by dissolving a weighed portion of ammonium citrate (#247561, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in deionized water. The modification of CeO2 nanoparticles was performed by gradual addition (dropwise) with continuous stirring at least 30 min of an aqueous solution of bare CeO2 nanoparticles to the ligand solution.

The concentration of the CeO2 sol was determined by the thermogravimetric method. Diffraction patterns of dried nanoscale CeO2 were recorded on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (CuKα radiation, θ–2θ geometry) (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). Electron images were obtained with a Leo 912 AB Omega transmission electron microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) at an accelerating voltage of 100 kV. UV-Vis spectra of CeO2 sols were recorded at room temperature using a Cary 4000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in 1.0 cm quartz cuvettes. The hydrodynamic diameter of the nanoparticles was measured with a Photocor Complex analyzer (radiation power 25 mW, diode laser, λ = 650 nm) (Photocor, Moscow, Russia). The measurements were carried out at room temperature and at the scattering angle of 90°. To measure zeta-potentials, a Nano ZS Zetasizer (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK) was used according to ISO/TR 19997:2018. Fluorescence spectra (λex = 280 nm, slit width 5 nm) were recorded by a FluoroLog 3 spectrofluorometer (HORIBA Jobin Yvon SAS, Kyoto, Japan).

2.2. Cell Culture

The fourth cell passage of human embryonic lung fibroblasts (HELF) were obtained from the Research Centre for Medical Genetics. HFLFs were seeded at 1 7 × 104 cell/mL in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Paneco, Moscow, Russia) with 10% fetal calf serum (PAA, Vienna, Austria), 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, and 10 μg/mL gentamycin. The cells were cultured at 37°C for 24 h. Next, citrate-coated nanoceria was added to the medium. The cells with nanoceria were incubated for 1, 3, 24, and 72 h.

2.3. MTT Test and TMRM Test

MTT test (the test with 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was used to examine cell viability. An EnSpire Plate Reader (EnSpire Equipment, Turku, Finland) was used to measure fluorescence at 550 nm. Cells incubated with culture medium and citrate solution in deionized water were used as negative control. As positive control, the incubation with dimethyl sulfoxide (0.0001%–50%) was used as described elsewhere (Savinova et al. 2023). In MTT-test, the cells were incubated with nanoceria for 72 hours. The TMRM test was carried out using a membrane-voltage-dependent dye, tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). TMRM is a cell-permeant, cationic, red-orange fluorescent dye that is readily sequestered by active mitochondria.

2.4. ROS Visualization with Fluorescence Microscopy

An AxioImagerA2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) was used for fluorescent microscopy of cells. The cells were cultured in slide flasks. After incubation with citrate-coated nanoceria, the medium was removed, cells were washed with PBS, and dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate was added (a stock solution 2 mg/mL was diluted with PBS 1: 200 before using). After incubation for 15 min, the cells were washed with PBS and immediately photographed. No less than 100 fields of view were analyzed; fluorescence intensity per a cell and the total fluorescence were analyzed using microscope software.

2.5. Antibodies

Primary antibodies DyLight488-γH2AX (pSer139) (nb100-78356G, NovusBio, Centennial, CO, USA), FITC-NRF2, (bs1074r-fitc, Bioss Antibodies Inc. Woburn, USA ), FITC-BRCA1 (Nb100-598F, NovusBio, Centennial, CO, USA), PE-8-oxo-dG (sc-393871 PE, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) CY5.5-NOX4 (bs-1091r-cy5-5, Bioss Antibodies Inc. Woburn, USA), A350-BCL2 (bs-15533r-a350, Bioss Antibodies Inc. Woburn, MA, USA), NFKB (bs-0465r-cy7, Bioss Antibodies Inc. Woburn, MA, USA), LC3 (NB100-2220 NovusBio, Centennial, CO, USA), BAX (Nb120-7977, NovusBio, Centennial, CO, USA), PCNA (ab2426, Abcam plc, UK), and secondary anti-rabbit IgG-FITC (sc-2359, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), were used.

2.6. Flow Cytometry Analysis

Flow cytometry was used to quantify intracellular ROS in unfixed cells suspension. The samples were incubated with 10 μM solution of H2DCFH-DA in PBS (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) 15 min in the dark, washed PBS, resuspended in PBS and analyzed by flow cytometer in FITC channel (CytoFlex S, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

To quantify proteins, cells were washed with Versene solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), treated with 0.25% trypsin (Paneco, Moscow, Russia), washed with the culture medium, then suspended in PBS (pH 7.4) (Paneco, Moscow, Russia). Next, the cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde (PFA, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, USA) at 37°C for 10 min, washed three times with 0.5% BSA-PBS, treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min at 20°C or with 90% methanol at 4°C, and washed 3 times with 0.5% BSA-PBS. Next, the cells were stained with conjugated antibodies (1 μg/mL) for 2 hours at room temperature, washed with PBS and analyzed by flow cytometer (CytoFlex S, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). For BAX quantitation, the cells were incubated with the unconjugated primary antibodies (1 μg/mL) overnight (+4°C), washed with 0.5% BSA-PBS and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with secondary antibodies (1 μg/mL), washed three times with 0.5% BSA–PBS and analyzed by flow cytometer (CytoFlex S, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

2.7. mRNA Quantitation

Total mRNA was isolated with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), treated with DNAse I, and then reverse transcribed by the Reverse Transcriptase kit (Sileks, Moscow, Russia). The qRT-PCR method with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used for obtaining expression profiles. The mRNA was quantified using StepOnePlus (Applied Biosystems) with TBP as a reference gene. The primers were used (Sintol, Moscow, Russia): BAX (F: CCCGAGAGGTCTTTTTCCGAG, R: CCAGCCCATGATGGTTCTGAT); BCL2 (F: TTTGGAAATCCGACCACTAA; R: AAAGAAATGCAAGTGAATGA); NF-κB1 (F: CAGATGGCCCATACCTTCAAAT; R: CGGAAACGAAATCCTCTCTGTT); NRF2 (NFE2L2) (F: TCCAGTCAGAAACCAGTGGAT, R: GAATGTCTGCGCCAAA AGCTG); NOX4 (F: TTGGGGCTAGGATTGTGTCTA; R: GAGTGTTCGGCACATGGGTA); BRCA1 (F: TGTGAGGCACCTGTGGTGA, R: CAGCTCCTGGCACTGGTAGAG); CCND1 (F: TTCGTGGCCTCTAAGATGA AGG; R: GAGCAGCTCCATTTGCAGC); and TBP (reference gene) (F: GCCCGAAACGCCGAATAT, R: CCGTGGTTCGTGGCTCTCT).

2.8. Statistics

The experiments were performed in triplicates; the data are given as mean and standard deviation (SD). The differences were considered significant when p < 0.01 (non-parametric Mann-Whitney test). For data analysis, the StatPlus2007 software (AnalystSoft Inc., Walnut, USA) was used.

3. Results

3.1. Citrate-Coated Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles

According to the thermogravimetric analysis, the concentration of the colloidal solution of cerium dioxide was 17 g/L (0.09 M). The prepared sample contained single-phase cerium dioxide (PDF2 34-0394) with a particle size of 3 nm as determined by the Scherrer equation. The results of transmission electron microscopy and electron diffraction confirmed the data on the particle size and phase composition of the obtained material. Ammonium citrate was used to functionalize the surface of CeO2 nanoparticles (1:1 molar ratio). According to dynamic light scattering data, the average hydrodynamic diameters of bare CeO2 nanoparticles and citrate-coated CeO2 were 11.3 ± 1.1 and 16.2 ± 1.0 nm, respectively. Electrokinetic properties of the aqueous CeO2 sol proves good stability of this colloidal system (ζ-potential is equal to +40.1 ± 1.3 mV) (Schramm 2005). Modification of CeO2 nanoparticles with ammonium citrate ions caused a decrease in the ζ potential to +13.1 ± 0.7 mV.

3.2. Cell Viability

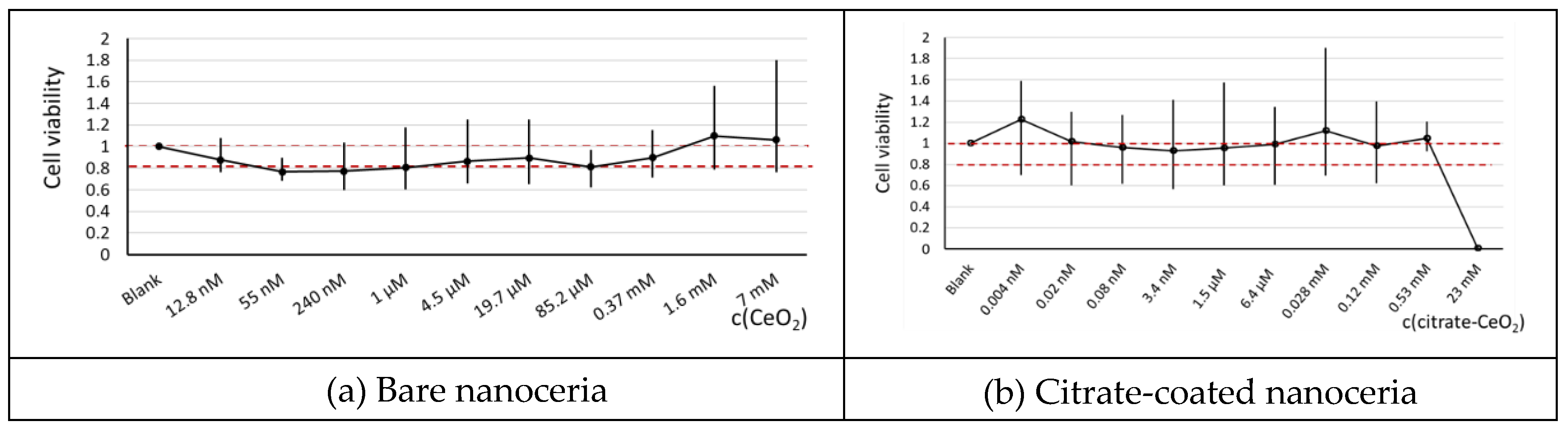

According to the MTT test, bare nanoceria showed no toxicity in a wide concentration range, but in 55 nm–1 µM range, cell viability was slightly lower than 80%. Citrate-coated nanoceria was non-toxic for HELFs up to 0.53 mM (

Figure 1). In general, citrate coating makes nanoceria substance less toxic towards HELFs. For next experiments, a 1.5 μM concentration of bare and citrate-coated nanoceria was chosen.

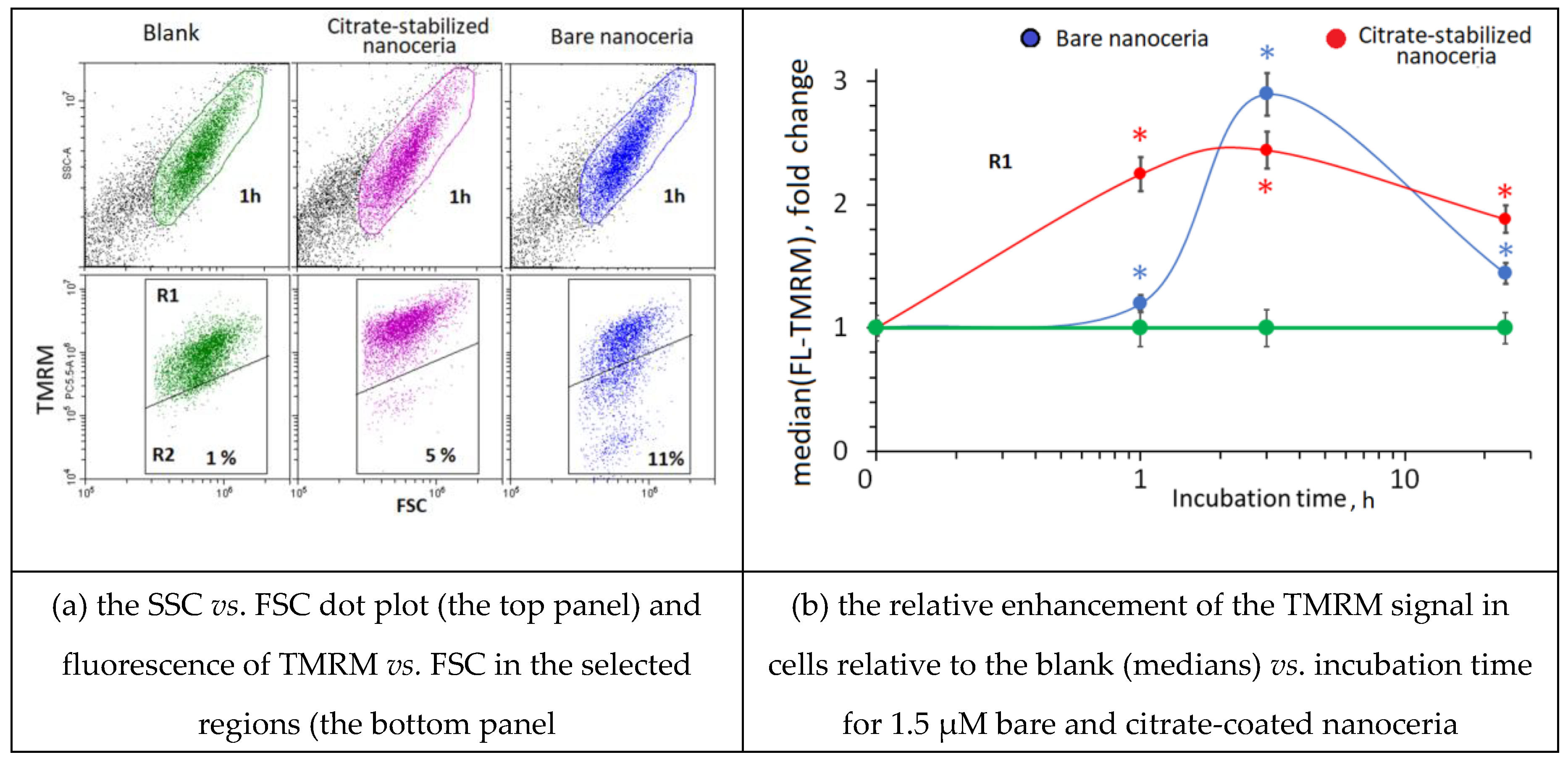

3.3. Mitochondrial Potential with the TMRM Test

We tested the response of HFLF mitochondria to the exposition with bare nanoceria and citrate-coated nanoceria using The TMRM (tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester) test and flow cytometry. The TMRM fluorescence increased after 1–3 h of incubation. After 24 h of incubation, the fluorescence decreased but remained higher than the control values (

Figure 2).

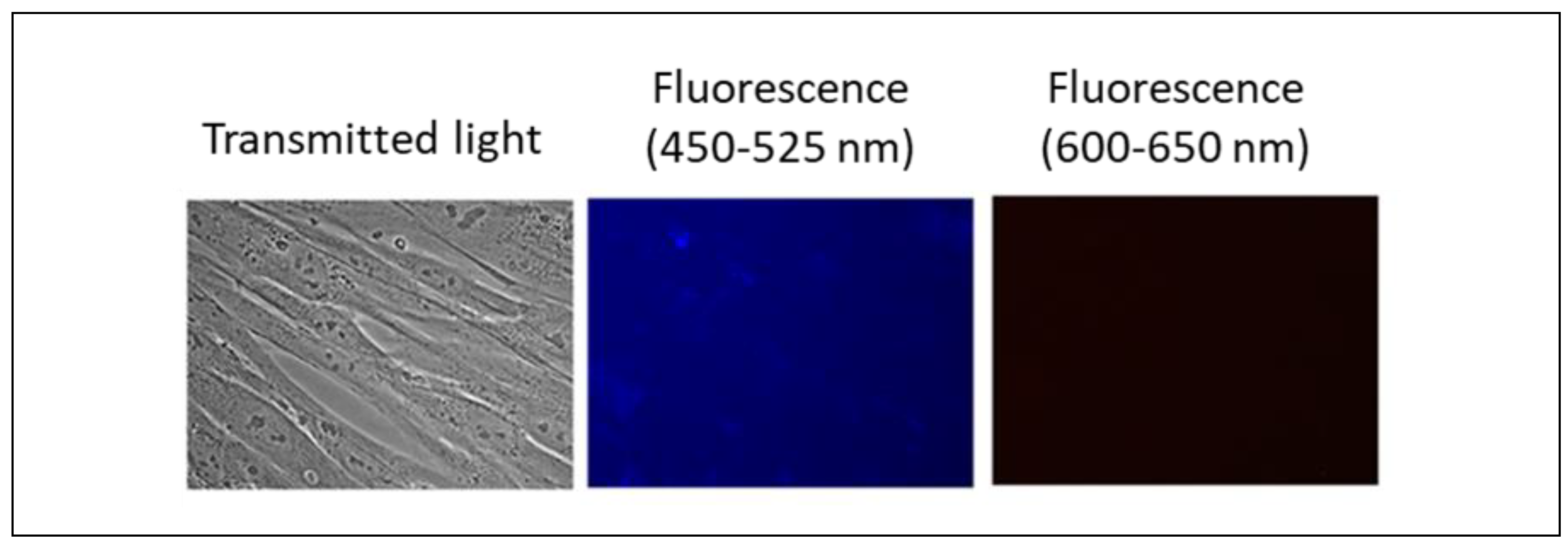

3.4. Penetration into Cells

Nanoceria does not exhibit intrinsic fluorescence, as confirmed by photographs of HELF cells after incubation with bare and citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 μM) for 3 hours (

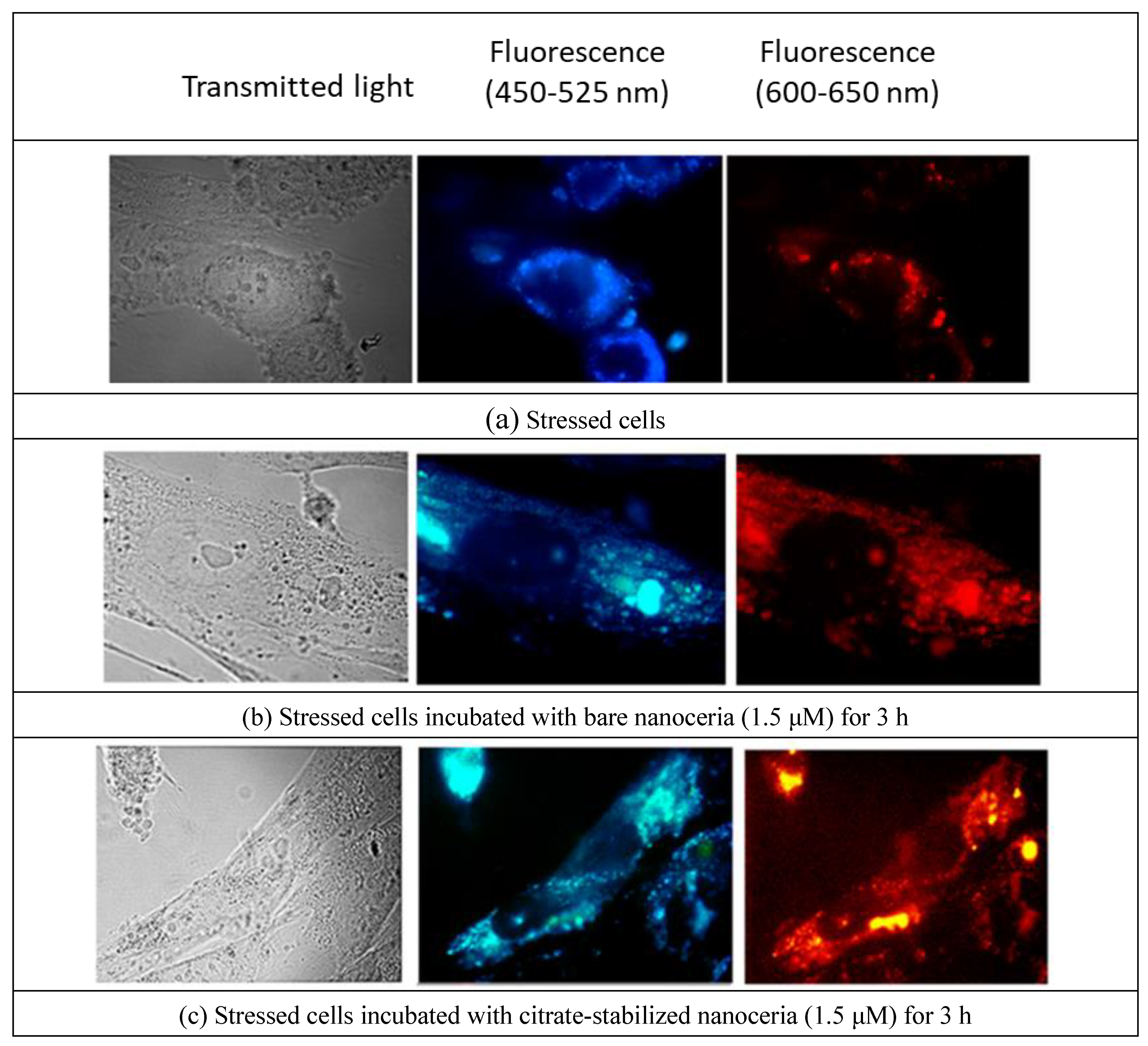

Figure 3). To reveal the effect of nanoparticles on cells, we stressed HELFs by adding 10 μM H

2O

2. The stressed cells possess autofluorescence (

Figure 4(a)). These cells were incubated with 1.5 µM bare nanoceria (

Figure 4(b)) and 1.5 µM citrate-stabilized nanoceria (

Figure 4(c)).

The autofluorescence of stressed cells incubated with bare nano-CeO2 and, to an even greater extent, of citrate-stabilized nano-CeO2 increased. Notably, the fluorescence of the nucleoli occurs, which is, presumably, due to nanoceria that has entered the nuclei.

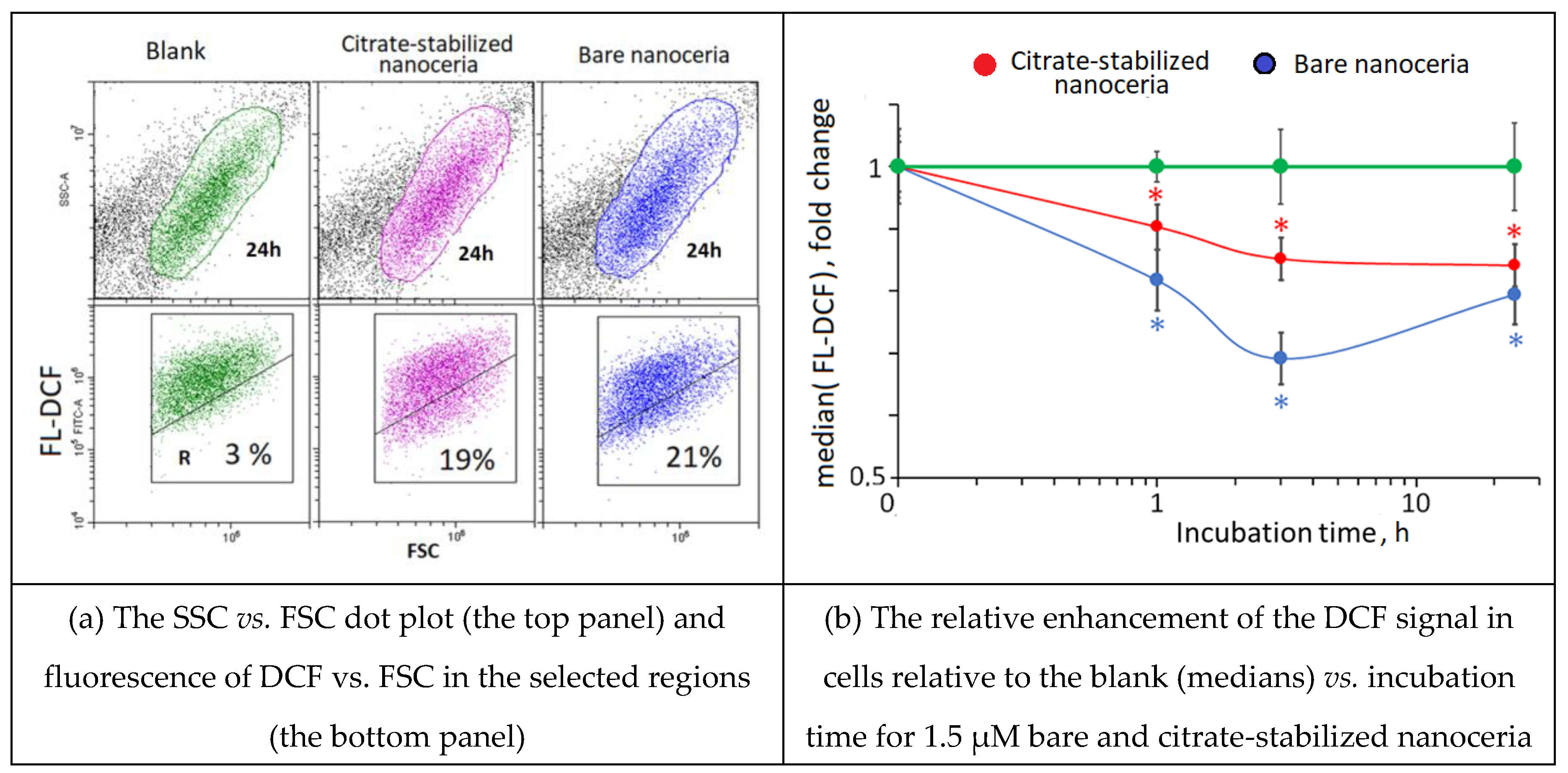

3.5. Intracellular ROS

HELFs were incubated with 1.5 μM bare and citrate-coated nanoceria for 1, 3, 24 and 72 hours. The data are presented in arbitrary units relative to the control (cells cultured without nanoceria). To assess the level of intracellular ROS, H2DCF-DA (2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate) was used as it penetrates quickly through cell membranes and becomes hydrolyzed in the cytosol to non-fluorescent DCFH, which is oxidized by ROS to fluorescent DCF.

The addition of bare nanoceria to cells results in a decrease in intracellular ROS level after 1 hour and a slight increase in ROS levels during 24 hours (

Figure 5(a)). The addition of citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 µM) to cells results in a decrease in intracellular ROS level after 24 hours (

Figure 5(b)).

Thus, bare and citrate-stabilized nanoceria added to cells during 1–24 hours act as ROS scavengers. As in the TMRM test, citrate-stabilized nanoceria has a more moderate effect.

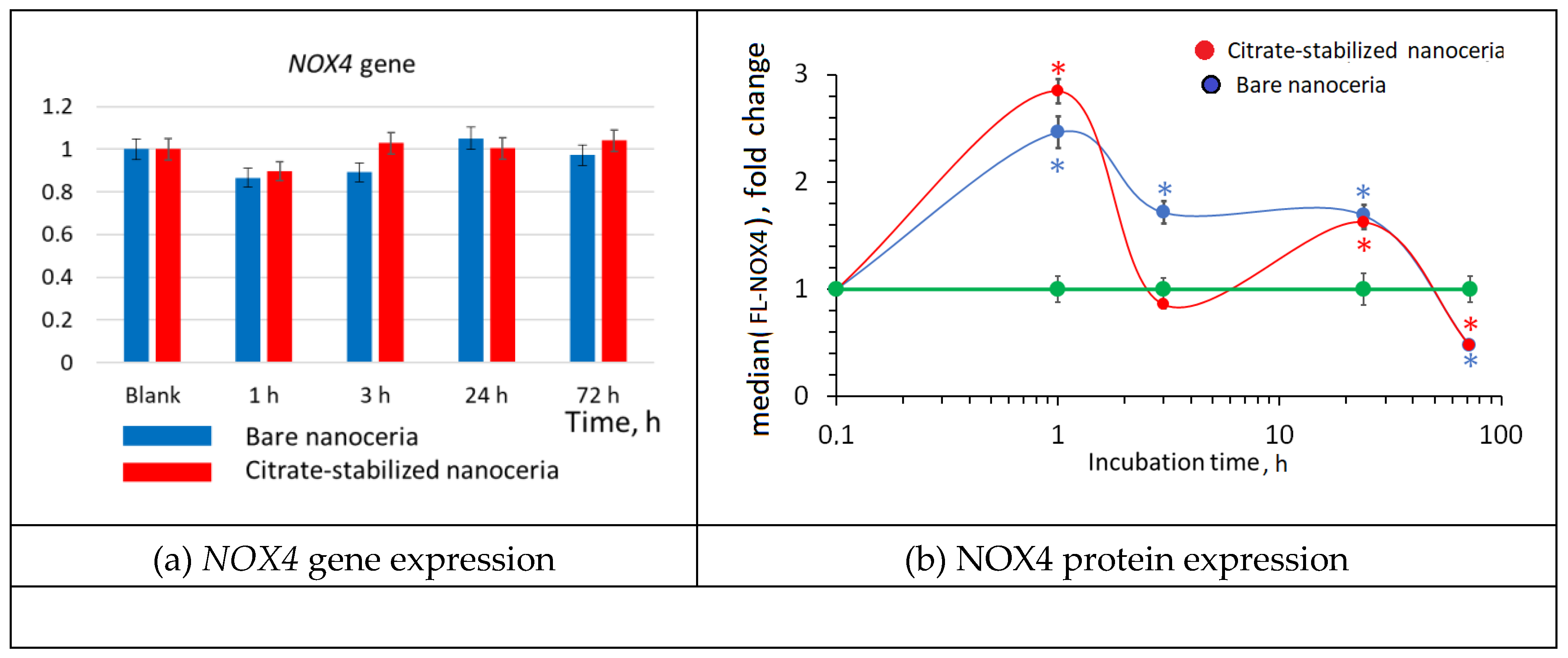

3.6. NOX4 Expression

NADPH oxidases are key sources of ROS in cells. Within 1–3 hours after adding nanoceria, the expression of the

NOX4 gene decreased slightly, returning to the control value after 24 hours (

Figure 6(a)). Protein expression increased sharply after 1 hour, then decreased, and after 72 hours, the expression of NOX4 was significantly lower than the control value (

Figure 6(b)). Probably, the activation of NOX4 is a compensatory response to the antioxidant effect of nanoceria (see

Figure 5). Note that the NOX4 response is like double-humped wave with a dip at 3 hours of exposition.

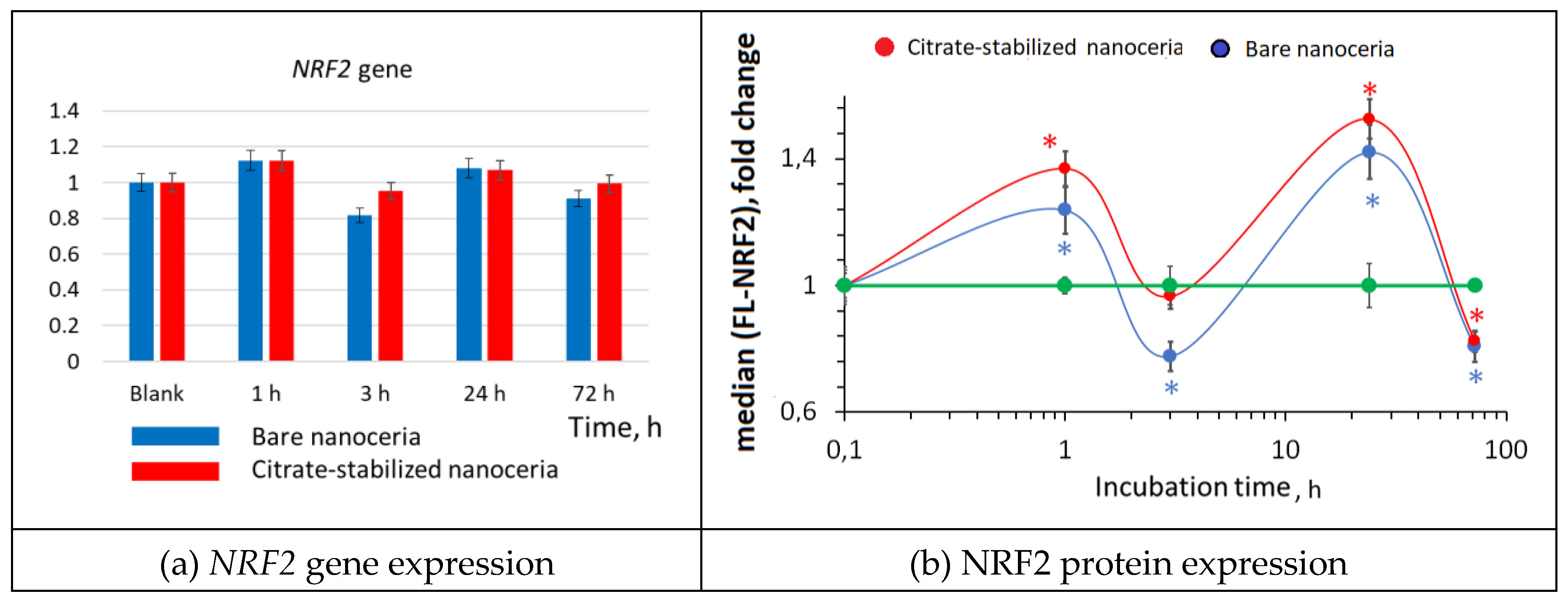

3.7. NRF2 Expression

The NRF2 transcription factor is involved in the antioxidant response. For bare and citrate-coated nanoceria, gene expression tends to increase after an hour, decrease after 3 hours, and increase again after 24 hours. However, these changes are not statistically significant (

Figure 7(a)). For protein expression there is similar wave-like dynamics with two humps, but the changes are statistically significant (

Figure 7(b)). The amount of the phosphorylated NRF2 increased by 1.2–1.4 times after 1 hour and by 1.4–1.5 times after 24 hours. The short-term activity of the NRF2 factor is most likely associated with the release it from protein complexes with KEAP1 and phosphorylation of NRF2 deposited in cells. Compared to bare nanoceria, citrate-coated nanoceria is “more antioxidative”.

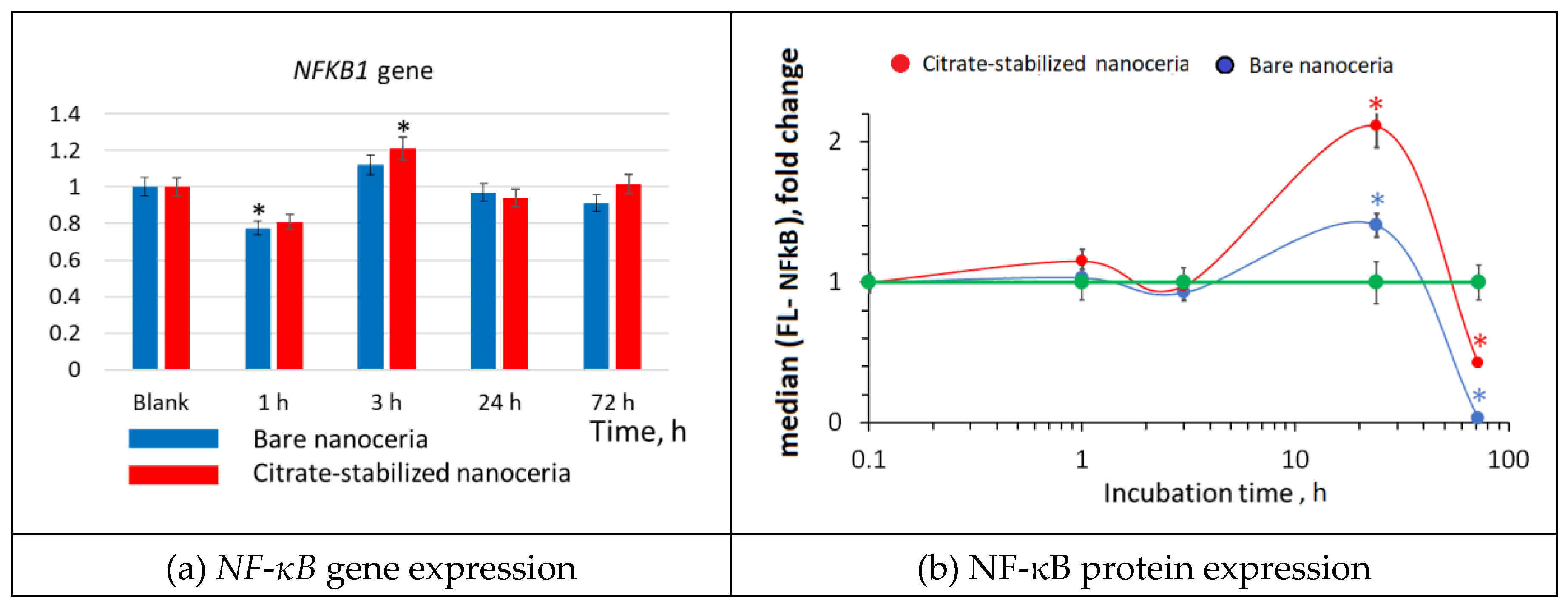

3.8. NF-κB Expression

Changes in the transcriptional activity of the

NFR2 gene are usually inversely related to the activation of transcription of the

NF-κB1 gene. The NF-κB transcription factor translocates to the nucleus and triggers the NF-κB signaling pathway in response to external influences, which leads to the synthesis of cytokines, adhesion molecules, and factors aimed at cell survival. The expression of the

NF-κB gene for bare and citrate-stabilized nanoceria had similar wave-like dynamics, it decreased after 1 hour, then increased after 3 hours and returned to the control level after 24–72 hours (

Figure 8 (a)). Protein expression increased significantly after 24 hours of incubation and decreased below the control values after 72 hours (

Figure 8(b)).

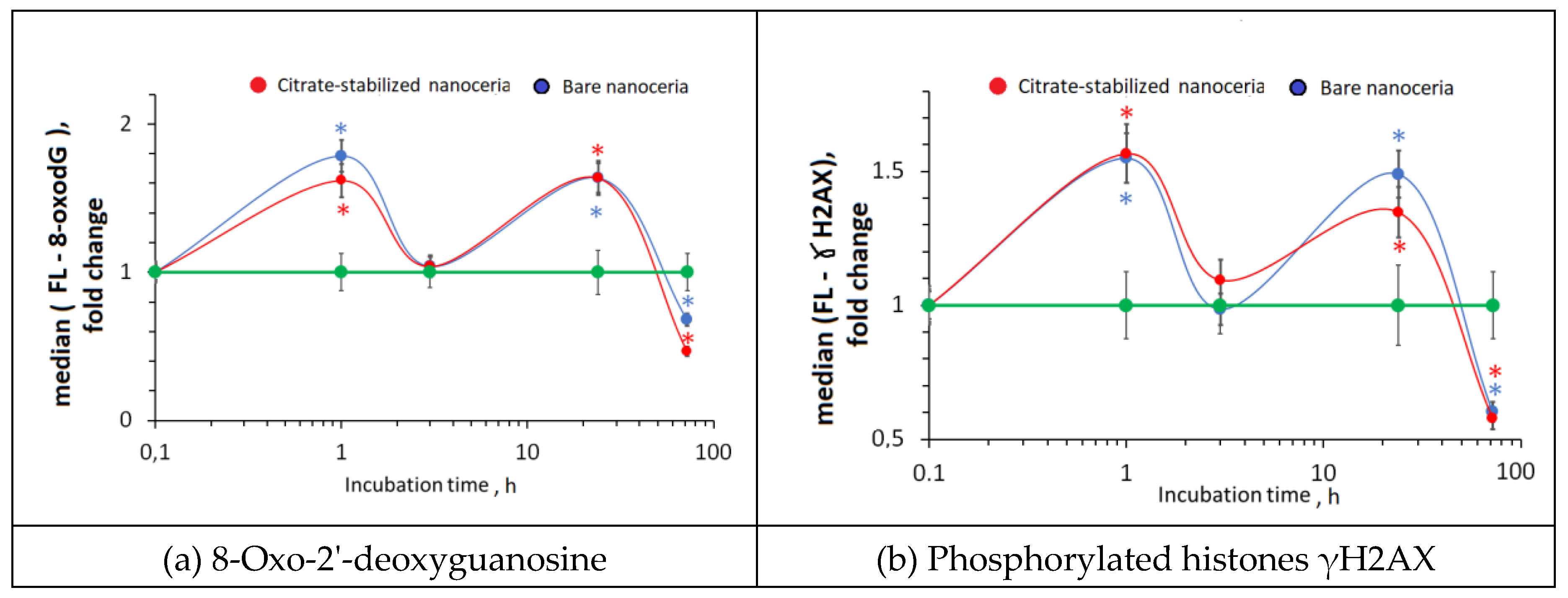

3.9. DNA Oxidative Damage and Double-Strand Breaks

Excessive ROS can lead to DNA oxidation and breaks. After 1 hours of incubation with nanoceria, the content of 8-oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG) that is a marker of oxidative DNA damage increased by 1.6–1.8 times. After 3 hours, the content of 8-oxo-dG decreased to the control values, then increased and decreased after 72 hours below the control values (

Figure 9 (a)). An increase in 8-oxo-dG may cause DNA breaks. We assessed DNA double-strand breaks using the γH2AX assay. After 1 hour of exposition with nanoceria, phosphorylated γH2AX increased by 1.5 times, which correlates with the increase in 8-oxo-dG. After 3 hours, the level of double-strand breaks decreased. After 24 hours, it increased that decreased below the control values (

Figure 9(b)). In general, the “oscillatory” dynamics of changes in 8-oxo-dG and γH2AX are similar.

In general, the dynamics of oxidative DNA damage corresponds to the dynamics of changes in NOX4, NRF2 and NF-κB.

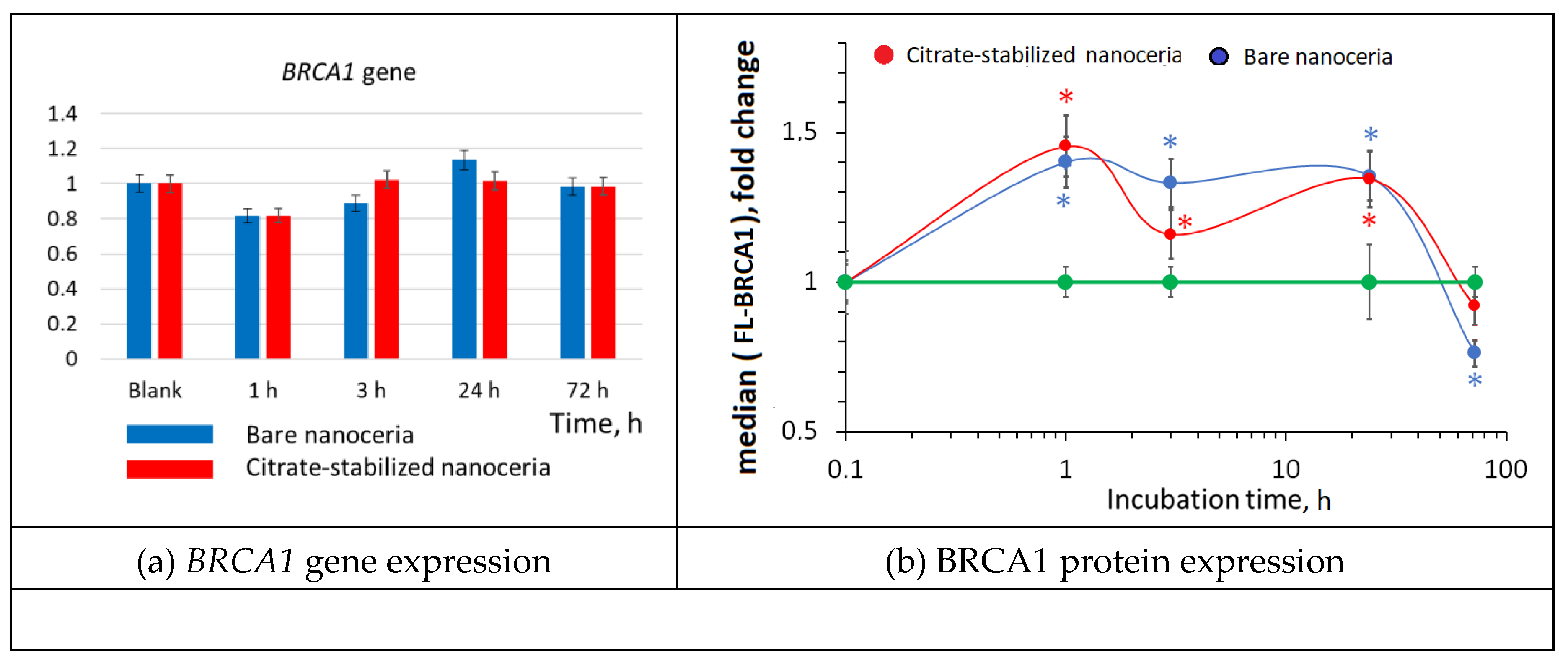

3.10. DNA Repair

A decrease in DNA breaks may be due to the activation of genes involved in DNA repair. The key repair gene is the

BRCA1 gene. Changes in the

BRCA1 gene expression are wave-like but not statistically significant (

Figure 10(a)). Changes in protein expression have the same oscillatory dynamics, but the changes are significant. Ater 1 hour, expression of the BRCA1 protein increased by 1.5 times (

Figure 10(b)). The increased expression of the BRCA1 protein lasts for up to 24 hours.

Thus, an increase in the expression of genes and proteins involved in repair in response to DNA breaks neutralizes the negative effect of nanoceria added to the cells.

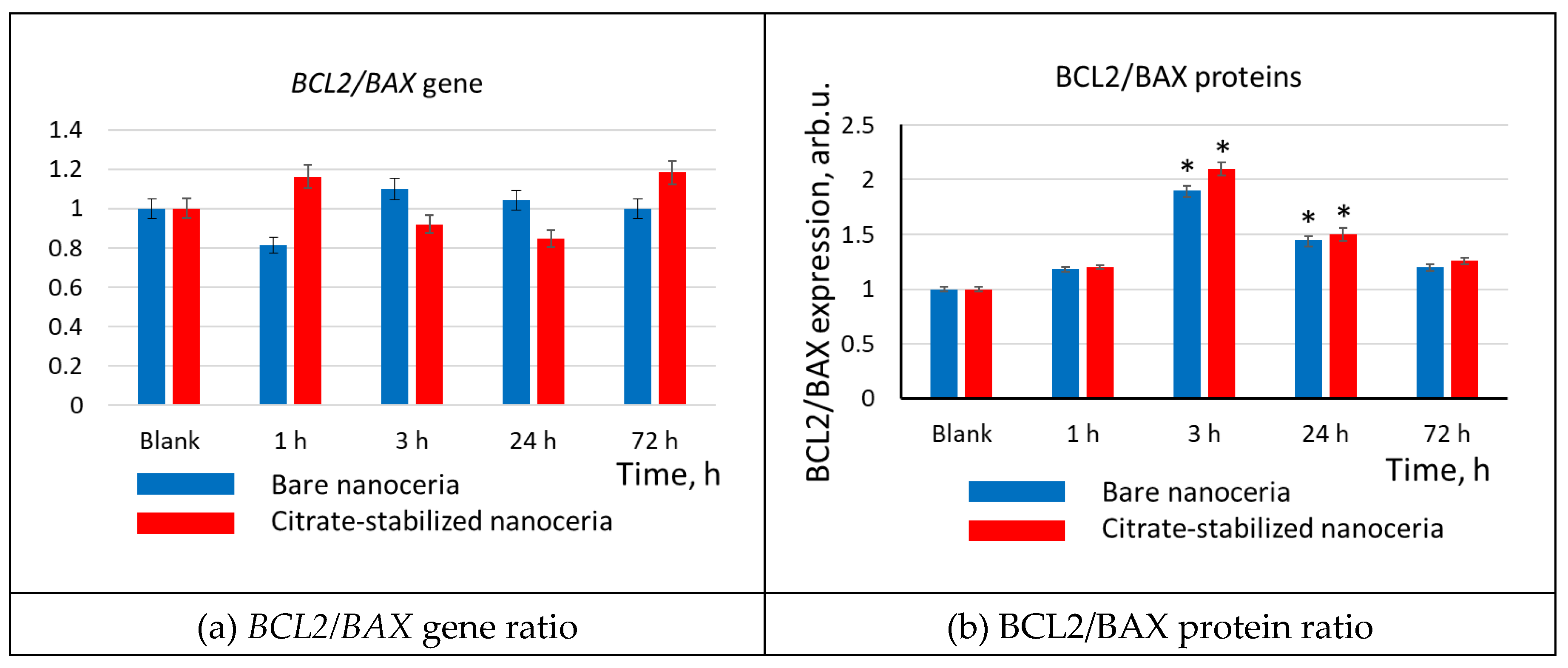

3.11. Apoptosis

The number of cells in the population depends on the balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis. Thus, we assessed the expression of pro-apoptotic (BAX) and anti-apoptotic (BCL2) genes and proteins. The BCL2/BAX gene/protein ratio is the most adequate and frequently used index of apoptosis.

After 3–24 hours of incubation with bare and citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 µM), the

BCL2/BAX gene ratio did not change significantly (

Figure 11(a)), but BCL2/BAX protein ratios increased by 1.5–2.3 times (

Figure 11(b)). This indicates a decrease in apoptosis, which resulted in an increase in the cell number after 24–72 hours of incubation.

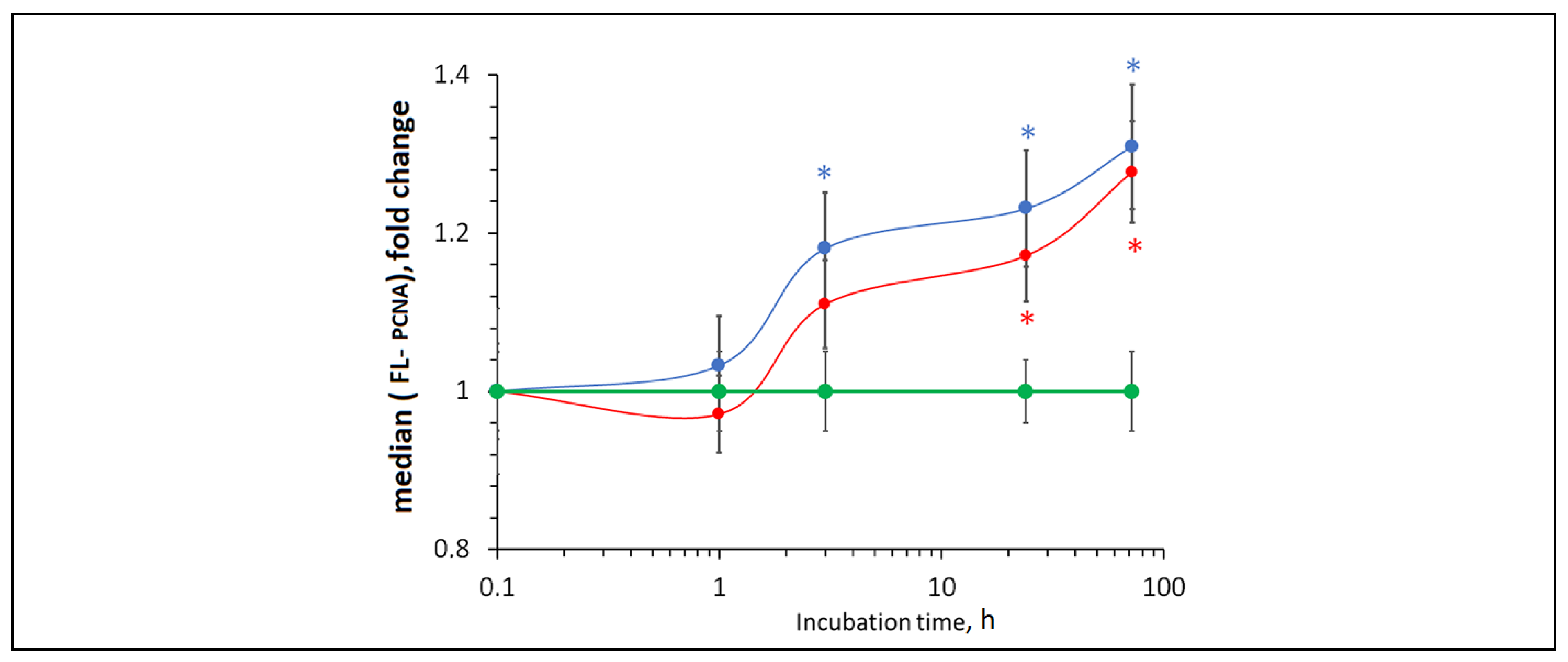

3.12. Cell Proliferation

The addition of bare and citrate-coated nanoceria to HELFs led to an increase in the expression of the PCNA proliferation protein after 3–72 hours by approximately 30% (

Figure 12).

Thus, both bare and citrate-coated nanoceria have a proliferative effect.

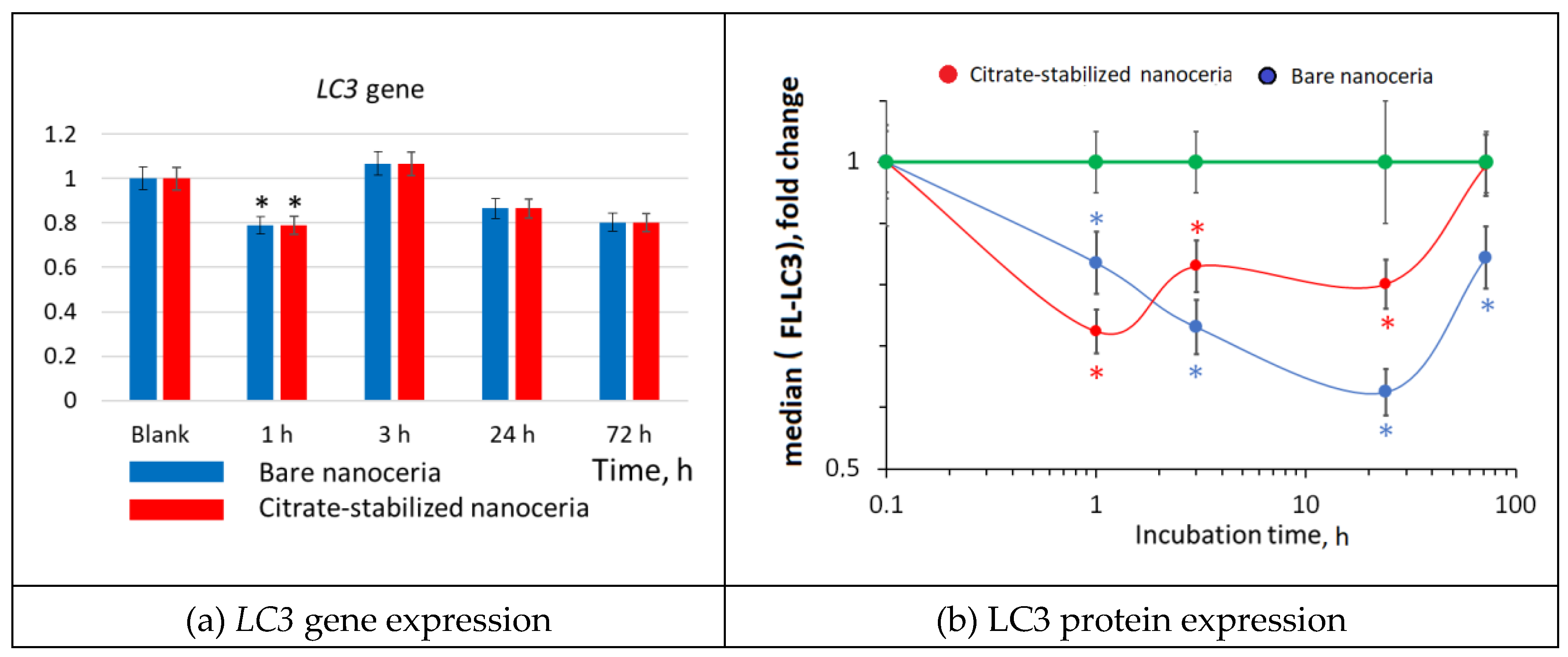

3.13. Autophagy

Besides apoptosis, cells may undergo autophagy. Bare and citrate-coated nanoceria (1.5 µM) caused a significant decrease in the expression of the LC3 autophagy protein by approximately 40% (

Figure 13).

Comparing bare and citrate-coated nanoceria, the effect of citrate-stabilized nanoceria had already disappeared after 72 hours, while effect of bare nanoceria still remained.

4. Discussion

The main results of the study can be summarized as follows (

Table 1): 1) both bare and citrate-coated nanoceria are non-toxic for human embryonic lung fibroblasts in a wide range of concentrations up to millimolar range; 2) both bare and citrate-coated nanoceria acts as an antioxidant reducing intracellular ROS in HELFs; 3) we observed a two-wave (“oscillatory”) dynamics in the expression of the oxidative proteins and markers of oxidative damage (NOX4, NRF2, NF-κB, 8-oxo-dG, phos-γH2AX, BRCA1), in which the content of proteins and markers increases within the first hour, decreases to the control values after 3 hours, increases again after 24 hours and drops below the control value after 72 hours; 4) apoptosis was inhibited after 3–24 hours of incubation; proliferation was activated and autophagy was inhibited within 3–72 hours; 5) the dynamics for bare and citrate-coated nanoceria were similar, however, the stabilization with citrate improved survival according to the MTT-test and caused a more moderate effect for intracellular ROS and expression of NF-κB, BRCA1, PCNA, and LC3.

Citrate-anion is a widely used nanoparticle stabilizer (Andrade et al. 2022) (Arsalani et al. 2023) (Nimi et al. 2018). Ammonium citrate is a neutral substance, but as a coating on nanoparticles, it can affect their toxicity. For example, silver nanoparticles coated with citrate turned out to be more toxic to human keratinocytes than those stabilized with polyethylene glycol (Bastos et al. 2016). However, on hepatoma cells, silver nanoparticles stabilized with citrate and polyethylene glycol exhibited similar toxicity (Bastos et al. 2017). Moreover, the method of preparation of the suspension also affects the toxicity (Park et al. 2014). This indicates the need to study nanoparticles with a specific stabilizer on each cell line. Citrate coating did not interfere with the binding of oligonucleotides to gold nanoparticles (Epanchintseva et al. 2018). However, a large amount of citrate on the surface of the gold particles increased their toxicity, although it did not affect the penetration into endothelial or epithelial cells (Freese et al. 2012). Citrate coating had no effect on cell viability in the case of Fe3O4 nanoparticles (Srivastava et al. 2011). Currently there are no reports devoted to the toxicity evaluation of citrate-coated nanoceria on human cells or they are extremely scarce. On mouse fibroblasts, citrate-coated nanoceria exhibited toxic properties compared to polyacrylic acid coating (Ould-Moussa et al. 2014). Previously, we studied the effect of citrate-coated nanoceria on mouse fibroblasts and showed that the expression of antioxidant genes increased, and citrate-coated nanoceria had a proliferative effect (Popov et al. 2016). According to this study, citrate-coated CeO2 generally exhibits cytoprotective and even regenerative properties with respect to human lung fibroblasts. Since nanoceria penetrates the cell membranes rather quickly (within 1 hour), the citrate coating does not interfere with penetration to fibroblasts. Stabilization with citrate improved survival according to the MTT-test and caused a more moderate effect for intracellular ROS and expression of NF-κB, BRCA1, PCNA, and LC3.

The fact that cerium dioxide entering the cell immediately provides an antioxidant effect is consistent with its pronounced SOD-like activity (Korsvik et al. 2007). Cerium dioxide acts not only as superoxide dismutase, converting the superoxide anion radical into hydrogen peroxide, but also exhibits catalase-like properties, neutralizing hydrogen peroxide (Pirmohamed et al. 2010). This explains the shift of ROS metabolism inside cells to the antioxidant scales. Antioxidant shift activates NOX4 gene expression (Guo and Chen 2015). The NOX4 enzyme catalyzes the production of the superoxide anion radical and hydrogen peroxide, which puts it among the most important redox regulators (Montezano et al. 2011). NOX4, in particular, stimulates the proliferation of various cells and apoptosis, performing both positive and negative roles (Przybylska and Mosieniak 2014). Increased NOX4 activity leads to the activation of the anti-inflammatory response NRF2 (Brewer et al. 2011) thus protecting the cell from damage (Schroder et al. 2012). Activation of NRF2 leads to activation of the pro-inflammatory NF-κB pathway. The negative role of NOX4 expression is manifested in oxidative DNA damage and double-strand breaks (Avci et al. 2019; Ekin et al. 2021). In turn, the response to DNA damage was the activation of repair systems (D'Errico et al. 2008). According to our results, changes in NOX4, NRF2, NF-kB, oxidative DNA damage and double-strand breaks, and DNA repair were characterized by similar two-wave dynamics, which confirms the deep relationship of these processes.

Of interest is the two-wave dynamics of the expression of oxidative proteins and markers (NOX4, NRF2, NF-κB, 8-oxo-dG, phos-γH2AX, BRCA1), namely, an increase after 1 hour, a decrease after 3 hours, a further increase after 24 hours and a final decrease after 72 hours. There can be at least two hypotheses here. First, this effect may be caused by a decrease in the number of cells after 3 hours. However, we monitored the cell number using a microscope and specifically conducted a 3-hour MTT test, which confirmed that the cell survival was close to 100%. Another hypothesis is that nanoceria changes the oxidation state. Self-oscillatory kinetics (the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction) has long been known for the Ce(III)/Ce(IV) system (Kasuya et al. 2005). Malyukin et al. observed the switching of oxidation state between Ce(III) and Ce(IV) in nanoceria in aqueous colloidal solutions (Malyukin et al. 2017). They hypothesized that Ce(III)→Ce(IV) reaction inside nanoceria is triggered by the diffusing oxygen originated from the water splitting on oxidized nanoceria surface. The kinetics of this reaction depends on the redox conditions. Lin et al. performed studies on a culture of human lung cancer cells (A549) with bare nanoceria, measuring the levels of intracellular ROS, lactate dehydrogenase, glutathione, malondialdehyde, and alpha-tocopherol. They found a monotonous increase in oxidative stress over three days, but their first measurement point was 24 hours , while oscillatory effect in our experiments was realized within 1 – 3 hours (Lin et al. 2006). Rubio et al. also studied the antioxidant and anti-genotoxic properties of cerium dioxide on human bronchial epithelial cells, but they used a preliminary incubation with nanoceria for 24 hours followed by adding KBrO3 (Rubio et al. 2016). Suarez et al. studied the effect of nanoceria (that is, protein expression of NO-synthase, superoxide dismutase, NOX4) on isolated human saphenous vein during 30 min (Guerra-Ojeda et al. 2022). Biomarkers of aging and oxidative stress were studied in synoviocytes, but incubation was also carried out for 24 hours (Ren et al. 2023). Thus, there is little information about the short-term effect of nanoceria on human cell culture, but the phenomenon of short-term oscillatory expression of oxidative proteins and markers is interesting and requires separate study.

In our experiments, cerium dioxide caused inhibition of apoptosis, which can be the reason for the regenerative properties of CeO2 nanoparticles (Marino et al. 2017; Qian et al. 2019). In many cases, scientists are concerned about the induction of apoptosis by nanoparticles, which can proceed in different ways (Ma and Yang 2016; Chen et al. 2018). The ability of nanoparticles to induce apoptosis gives grounds to consider them as anticancer drugs (Taheriazam et al. 2023) (Naseer et al. 2022) (Iqbal et al. 2021) (Paunovic et al. 2020). Suppression of apoptosis may raise concern in terms of carcinogenic effects (Solano-Galvez et al. 2018), which necessitates a more thorough study of the effect of apoptosis inhibitors on cells. The short duration of the proliferative effects of nanoceria can be considered as a beneficial feature of this material.

Regarding the toxicity and safety of nanoceria, there are contradictory data in the literature. Studies of bare nanoceria in cultures of type II alveolar epithelial cells of rats indicate its pro-inflammatory and oxidative stress effects (Schwotzer et al. 2018). In relation to lung cancer cells, nanoceria caused pronounced oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation and membrane damage (Lin et al. 2006). Similarly, Cheng et al. showed that CeO2 nanoparticles induce damage and apoptosis in human hepatoma cells through oxidative stress and activation of MAPK signaling pathways (Cheng et al. 2013). Nanoscale ceria exhibit toxicity to human neuroblastoma cells (Kumari et al. 2014). The toxic effect of CeO2 on lung adenocarcinoma cells was demonstrated by Mittal et al. They proved ROS-mediated DNA damage and apoptotic cell death under the action of CeO2 (Mittal and Pandey 2014). CeO2 exhibited ROS-mediated toxicity to melanoma cells (Ali et al. 2015). Cerium dioxide nanoparticles are an effective radiosensitizer of DNA damage caused by ionizing radiation in HL-60 cells (Montazeri et al. 2018). In contrast, in a study on human ovarian and colon cancer cells, CeO2 showed antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. The authors believe that these nanoparticles can be used to minimize the inflammatory effects of cancer (Vassie et al. 2017). The antioxidant effect of cerium dioxide in human monocytic leukemia cells is also considered beneficial (Patel et al. 2018). The combined administration of CeO2 and lead acetate suppresses genotoxicity, inflammation, and ROS formation and restores the integrity of genomic DNA (Mohamed 2022).

5. Conclusions

Summing up, in human embryonic lung fibroblasts, both bare and citrate-coated nanoceria have a short-term wave-like effect on the regulation of expression of oxidative metabolism genes and proteins. The two-wave “oscillatory” dynamics of oxidative proteins and markers may be associated with changes in the oxidation state of nanoceria in cells. The medium- and long-term effects of nanoceria on HELFs lead to proliferation and regeneration of HELFs. Bare and citrate-coated nanoceria provide similar effects, but stabilization with citrate leads to a more moderate action of nanoceria on HELFs.

Acknowledgements

The research described in this paper was financially supported by the Russian Science Foundation, project No. 24-25-00088.

References

- Ali, D., Alarifi, S., Alkahtani, S., AlKahtane, A.A. and Almalik, A. (2015), "Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Induce Oxidative Stress and Genotoxicity in Human Skin Melanoma Cells", Cell Biochem Biophys, 71(3), 1643-1651. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.G.D., Ferreira, D., Veloso, S.R.S., Santos-Pereira, C., Castanheira, E.M.S., Corte-Real, M. and Rodrigues, L.R. (2022), "Synthesis and Cytotoxicity Assessment of Citrate-Coated Calcium and Manganese Ferrite Nanoparticles for Magnetic Hyperthermia", Pharmaceutics, 14(12). [CrossRef]

- Arsalani, S., Arsalani, S., Isikawa, M., Guidelli, E.J., Mazon, E.E., Ramos, A.P., Bakuzis, A., Pavan, T.Z., Baffa, O. and Carneiro, A.A.O. (2023), "Hybrid Nanoparticles of Citrate-Coated Manganese Ferrite and Gold Nanorods in Magneto-Optical Imaging and Thermal Therapy", Nanomaterials (Basel), 13(3). [CrossRef]

- Asati, A., Santra, S., Kaittanis, C., Nath, S. and Perez, J.M. (2009), "Oxidase-like activity of polymer-coated cerium oxide nanoparticles", Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 48(13), 2308-2312. [CrossRef]

- Avci, V., Ayengin, K. and Alp, H.H. (2019), "Oxidative DNA Damage and NOX4 Levels in Children with Undescended Testes", Eur J Pediatr Surg, 29(6), 545-550. [CrossRef]

- Bastos, V., Ferreira-de-Oliveira, J.M.P., Carrola, J., Daniel-da-Silva, A.L., Duarte, I.F., Santos, C. and Oliveira, H. (2017), "Coating independent cytotoxicity of citrate- and PEG-coated silver nanoparticles on a human hepatoma cell line", J Environ Sci (China), 51, 191-201. [CrossRef]

- Bastos, V., Ferreira de Oliveira, J.M., Brown, D., Jonhston, H., Malheiro, E., Daniel-da-Silva, A.L., Duarte, I.F., Santos, C. and Oliveira, H. (2016), "The influence of Citrate or PEG coating on silver nanoparticle toxicity to a human keratinocyte cell line", Toxicol Lett, 249, 29-41. [CrossRef]

- Bisso, S. and Leroux, J.C. (2020), "Nanopharmaceuticals: A focus on their clinical translatability", Int J Pharm, 578, 119098. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, A.C., Murray, T.V., Arno, M., Zhang, M., Anilkumar, N.P., Mann, G.E. and Shah, A.M. (2011), "Nox4 regulates Nrf2 and glutathione redox in cardiomyocytes in vivo", Free Radic Biol Med, 51(1), 205-215. [CrossRef]

- Cai, X., Yodoi, J., Seal, S. and McGinnis, J.F. (2014), "Nanoceria and thioredoxin regulate a common antioxidative gene network in tubby mice", Adv Exp Med Biol, 801, 829-836. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Patil, S., Seal, S. and McGinnis, J.F. (2006), "Rare earth nanoparticles prevent retinal degeneration induced by intracellular peroxides", Nat Nanotechnol, 1(2), 142-150. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Wu, L.Y. and Yang, W.X. (2018), "Nanoparticles induce apoptosis via mediating diverse cellular pathways", Nanomedicine (Lond), 13(22), 2939-2955. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G., Guo, W., Han, L., Chen, E., Kong, L., Wang, L., Ai, W., Song, N., Li, H. and Chen, H. (2013), "Cerium oxide nanoparticles induce cytotoxicity in human hepatoma SMMC-7721 cells via oxidative stress and the activation of MAPK signaling pathways", Toxicol In Vitro, 27(3), 1082-1088. [CrossRef]

- Cimen, I.C.C., Danabas, D. and Ates, M. (2024), "Some nanotoxicity effects of copper (60-80 nm) and copper oxide (40 nm) nanoparticles on Artemia salina", Advances in Nano Research, 16(5), 501-508. [CrossRef]

- D'Errico, M., Parlanti, E. and Dogliotti, E. (2008), "Mechanism of oxidative DNA damage repair and relevance to human pathology", Mutat Res, 659(1-2), 4-14. [CrossRef]

- Das, M., Patil, S., Bhargava, N., Kang, J.F., Riedel, L.M., Seal, S. and Hickman, J.J. (2007), "Auto-catalytic ceria nanoparticles offer neuroprotection to adult rat spinal cord neurons", Biomaterials, 28(10), 1918-1925. [CrossRef]

- Ekin, S., Yildiz, H. and Alp, H.H. (2021), "NOX4, MDA, IMA and oxidative DNA damage: can these parameters be used to estimate the presence and severity of OSA?", Sleep Breath, 25(1), 529-536. [CrossRef]

- Epanchintseva, A., Vorobjev, P., Pyshnyi, D. and Pyshnaya, I. (2018), "Fast and Strong Adsorption of Native Oligonucleotides on Citrate-Coated Gold Nanoparticles", Langmuir, 34(1), 164-172. [CrossRef]

- Freese, C., Uboldi, C., Gibson, M.I., Unger, R.E., Weksler, B.B., Romero, I.A., Couraud, P.O. and Kirkpatrick, C.J. (2012), "Uptake and cytotoxicity of citrate-coated gold nanospheres: Comparative studies on human endothelial and epithelial cells", Part Fibre Toxicol, 9, 23. [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Ojeda, S., Marchio, P., Rueda, C., Suarez, A., Garcia, H., Victor, V.M., Juez, M., Martin-Gonzalez, I., Vila, J.M. and Mauricio, M.D. (2022), "Cerium dioxide nanoparticles modulate antioxidant defences and change vascular response in the human saphenous vein", Free Radic Biol Med, 193(Pt 2), 694-701. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S. and Chen, X. (2015), "The human Nox4: gene, structure, physiological function and pathological significance", J Drug Target, 23(10), 888-896. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S., Jabeen, F., Chaudhry, A.S., Shah, M.A. and Batiha, G.E. (2021), "Toxicity assessment of metallic nickel nanoparticles in various biological models: An interplay of reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress, and apoptosis", Toxicol Ind Health, 37(10), 635-651. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, V.K., Usatenko, A.V. and Shcherbakov, A.B. (2009), "Antioxidant activity of nanocrystalline ceria to anthocyanins ", Russian Journal of Inorganic Chemistry, 54(10), 1522-1527. [CrossRef]

- K Khulbe, K Karmakar, S Ghosh, K Chandra, D Chakravortty and Mugesh, G. (2020), "Nanoceria-Based Phospholipase-Mimetic Cell Membrane Disruptive Anti-Biofilm Agents", ACS Applied Bio Materials, 1-36.

- Kasuya, M., Hatanaka, K., Hobley, J., Fukumura, H. and Sevcikova, H. (2005), "Density changes accompanying wave propagation in the cerium-catalyzed Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction", J Phys Chem A, 109(7), 1405-1410. [CrossRef]

- Korsvik, C., Patil, S., Seal, S. and Self, W.T. (2007), "Superoxide dismutase mimetic properties exhibited by vacancy engineered ceria nanoparticles", Chem Commun (Camb),(10), 1056-1058. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M., Singh, S.P., Chinde, S., Rahman, M.F., Mahboob, M. and Grover, P. (2014), "Toxicity study of cerium oxide nanoparticles in human neuroblastoma cells", Int J Toxicol, 33(2), 86-97. [CrossRef]

- Lin, W., Huang, Y.W., Zhou, X.D. and Ma, Y. (2006), "Toxicity of cerium oxide nanoparticles in human lung cancer cells", Int J Toxicol, 25(6), 451-457. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Huang, Z. and Liu, J. (2016), "Boosting the oxidase mimicking activity of nanoceria by fluoride capping: rivaling protein enzymes and ultrasensitive F(-) detection", Nanoscale, 8(28), 13562-13567. [CrossRef]

- Lord, M.S., Farrugia, B.L., Yan, C.M., Vassie, J.A. and Whitelock, J.M. (2016), "Hyaluronan coated cerium oxide nanoparticles modulate CD44 and reactive oxygen species expression in human fibroblasts", J Biomed Mater Res A, 104(7), 1736-1746. [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.D. and Yang, W.X. (2016), "Engineered nanoparticles induce cell apoptosis: potential for cancer therapy", Oncotarget, 7(26), 40882-40903. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Li, P., Zhao, L., Liu, J., Yu, J., Huang, Y., Zhu, Y., Li, Z., Zhao, R., Hua, S., Zhu, Y. and Zhang, Z. (2021), "Size-Dependent Cytotoxicity and Reactive Oxygen Species of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles in Human Retinal Pigment Epithelia Cells", Int J Nanomedicine, 16, 5333-5341. [CrossRef]

- Malyukin, Y., Klochkov, V., Maksimchuk, P., Seminko, V. and Spivak, N. (2017), "Oscillations of Cerium Oxidation State Driven by Oxygen Diffusion in Colloidal Nanoceria (CeO(2 - x) )", Nanoscale Res Lett, 12(1), 566. [CrossRef]

- Marino, A., Tonda-Turo, C., De Pasquale, D., Ruini, F., Genchi, G., Nitti, S., Cappello, V., Gemmi, M., Mattoli, V., Ciardelli, G. and Ciofani, G. (2017), "Gelatin/nanoceria nanocomposite fibers as antioxidant scaffolds for neuronal regeneration", Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj, 1861(2), 386-395. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S. and Pandey, A.K. (2014), "Cerium oxide nanoparticles induced toxicity in human lung cells: role of ROS mediated DNA damage and apoptosis", Biomed Res Int, 2014, 891934. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.R.H. (2022), "Acute Oral Administration of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Suppresses Lead Acetate-Induced Genotoxicity, Inflammation, and ROS Generation in Mice Renal and Cardiac Tissues", Biol Trace Elem Res, 200(7), 3284-3293. [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, A., Zal, Z., Ghasemi, A., Yazdannejat, H., Asgarian-Omran, H. and Hosseinimehr, S.J. (2018), "Radiosensitizing Effect of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles on Human Leukemia Cells", Pharm Nanotechnol, 6(2), 111-115. [CrossRef]

- Montezano, A.C., Burger, D., Ceravolo, G.S., Yusuf, H., Montero, M. and Touyz, R.M. (2011), "Novel Nox homologues in the vasculature: focusing on Nox4 and Nox5", Clin Sci (Lond), 120(4), 131-141. [CrossRef]

- Naseer, F., Ahmed, M., Majid, A., Kamal, W. and Phull, A.R. (2022), "Green nanoparticles as multifunctional nanomedicines: Insights into anti-inflammatory effects, growth signaling and apoptosis mechanism in cancer", Semin Cancer Biol, 86(Pt 2), 310-324. [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, L.T.N., Bui, V.K.H., Moon, J.Y. and Lee, Y.C. (2019), "In-Vitro Cytotoxicity and Oxidative Stress Induced by Cerium Aminoclay and Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles in Human Skin Keratinocyte Cells", J Nanosci Nanotechnol, 19(10), 6369-6375. [CrossRef]

- Nimi, N., Saraswathy, A., Nazeer, S.S., Francis, N., Shenoy, S.J. and Jayasree, R.S. (2018), "Biosafety of citrate coated zerovalent iron nanoparticles for Magnetic Resonance Angiography", Data Brief, 20, 1829-1835. [CrossRef]

- Ould-Moussa, N., Safi, M., Guedeau-Boudeville, M.A., Montero, D., Conjeaud, H. and Berret, J.F. (2014), "In vitro toxicity of nanoceria: effect of coating and stability in biofluids", Nanotoxicology, 8(7), 799-811. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W., Oh, J.H., Kim, W.K. and Lee, S.K. (2014), "Toxicity of citrate-coated silver nanoparticles differs according to method of suspension preparation", Bull Environ Contam Toxicol, 93(1), 53-59. [CrossRef]

- Patel, P., Kansara, K., Singh, R., Shukla, R.K., Singh, S., Dhawan, A. and Kumar, A. (2018), "Cellular internalization and antioxidant activity of cerium oxide nanoparticles in human monocytic leukemia cells", Int J Nanomedicine, 13(T-NANO 2014 Abstracts), 39-41. [CrossRef]

- Paunovic, J., Vucevic, D., Radosavljevic, T., Mandic-Rajcevic, S. and Pantic, I. (2020), "Iron-based nanoparticles and their potential toxicity: Focus on oxidative stress and apoptosis", Chem Biol Interact, 316, 108935. [CrossRef]

- Pirmohamed, T., Dowding, J.M., Singh, S., Wasserman, B., Heckert, E., Karakoti, A.S., King, J.E., Seal, S. and Self, W.T. (2010), "Nanoceria exhibit redox state-dependent catalase mimetic activity", Chem Commun (Camb), 46(16), 2736-2738. [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.L., Popova, N.R., Selezneva, II, Akkizov, A.Y. and Ivanov, V.K. (2016), "Cerium oxide nanoparticles stimulate proliferation of primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts in vitro", Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl, 68, 406-413. [CrossRef]

- Przybylska, D. and Mosieniak, G. (2014), "[The role of NADPH oxidase NOX4 in regulation of proliferation, senescence and differentiation of the cells]", Postepy Biochem, 60(1), 69-76.

- Qian, Y., Han, Q., Zhao, X., Li, H., Yuan, W.E. and Fan, C. (2019), "Asymmetrical 3D Nanoceria Channel for Severe Neurological Defect Regeneration", iScience, 12, 216-231. [CrossRef]

- Ren, X., Zhuang, H., Jiang, F., Zhang, Y. and Zhou, P. (2023), "Ceria Nanoparticles Alleviated Osteoarthritis through Attenuating Senescence and Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype in Synoviocytes", Int J Mol Sci, 24(5). [CrossRef]

- Rubio, L., Annangi, B., Vila, L., Hernandez, A. and Marcos, R. (2016), "Antioxidant and anti-genotoxic properties of cerium oxide nanoparticles in a pulmonary-like cell system", Arch Toxicol, 90(2), 269-278. [CrossRef]

- Saifi, M.A., Seal, S. and Godugu, C. (2021), "Nanoceria, the versatile nanoparticles: Promising biomedical applications", J Control Release, 338, 164-189. [CrossRef]

- Savinova, E.A., Salimova, T.A., Proskurnina, E.V., Rodionov, I.V., Kraevaya, O.A., Troshin, P.A., Kameneva, L.V., Malinovskaya, E.M., Dolgikh, O.A., Veiko, N.N. and Kostyuk, S.V. (2023), "Effect of Water-Soluble Chlorine-Containing Buckminsterfullerene Derivative on the Metabolism of Reactive Oxygen Species in Human Embryonic Lung Fibroblasts", Oxygen, 3, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Schramm, L. 2005. Emulsions, foams, and suspensions: fundamentals and applications. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.

- Schroder, K., Zhang, M., Benkhoff, S., Mieth, A., Pliquett, R., Kosowski, J., Kruse, C., Luedike, P., Michaelis, U.R., Weissmann, N., Dimmeler, S., Shah, A.M. and Brandes, R.P. (2012), "Nox4 is a protective reactive oxygen species generating vascular NADPH oxidase", Circ Res, 110(9), 1217-1225. [CrossRef]

- Schwotzer, D., Niehof, M., Schaudien, D., Kock, H., Hansen, T., Dasenbrock, C. and Creutzenberg, O. (2018), "Cerium oxide and barium sulfate nanoparticle inhalation affects gene expression in alveolar epithelial cells type II", J Nanobiotechnology, 16(1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakov, A.B., Teplonogova, M.A., Ivanova, O.S., Shekunova, T.O., Ivonin, I.V., Baranchikov, A.Y. and Ivanov, V.K. (2017), "Facile method for fabrication of surfactant-free concentrated CeO2 sols", Materials Research Express, 4(5), 055008. [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. and Jones, D.P. (2020), "Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents", Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 21(7), 363-383. [CrossRef]

- Solano-Galvez, S.G., Abadi-Chiriti, J., Gutierrez-Velez, L., Rodriguez-Puente, E., Konstat-Korzenny, E., Alvarez-Hernandez, D.A., Franyuti-Kelly, G., Gutierrez-Kobeh, L. and Vazquez-Lopez, R. (2018), "Apoptosis: Activation and Inhibition in Health and Disease", Med Sci (Basel), 6(3). [CrossRef]

- Souto, E.B., Silva, G.F., Dias-Ferreira, J., Zielinska, A., Ventura, F., Durazzo, A., Lucarini, M., Novellino, E. and Santini, A. (2020), "Nanopharmaceutics: Part I-Clinical Trials Legislation and Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) of Nanotherapeutics in the EU", Pharmaceutics, 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S., Awasthi, R., Gajbhiye, N.S., Agarwal, V., Singh, A., Yadav, A. and Gupta, R.K. (2011), "Innovative synthesis of citrate-coated superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles and its preliminary applications", J Colloid Interface Sci, 359(1), 104-111. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Lu, Y., Saredy, J., Wang, X., Drummer Iv, C., Shao, Y., Saaoud, F., Xu, K., Liu, M., Yang, W.Y., Jiang, X., Wang, H. and Yang, X. (2020), "ROS systems are a new integrated network for sensing homeostasis and alarming stresses in organelle metabolic processes", Redox Biol, 37, 101696. [CrossRef]

- Taheriazam, A., Abad, G.G.Y., Hajimazdarany, S., Imani, M.H., Ziaolhagh, S., Zandieh, M.A., Bayanzadeh, S.D., Mirzaei, S., Hamblin, M.R., Entezari, M., Aref, A.R., Zarrabi, A., Ertas, Y.N., Ren, J., Rajabi, R., Paskeh, M.D.A., Hashemi, M. and Hushmandi, K. (2023), "Graphene oxide nanoarchitectures in cancer biology: Nano-modulators of autophagy and apoptosis", J Control Release, 354, 503-522. [CrossRef]

- Tan, G., llk, S., Foto, F.Z., Foto, E. and Saglam, N. (2021), "Antioxidative and antiproliferative effects of propolis-reduced silver nanoparticles", Advances in Nano Research, 10(2), 139-150. [CrossRef]

- Tarnuzzer, R.W., Colon, J., Patil, S. and Seal, S. (2005), "Vacancy engineered ceria nanostructures for protection from radiation-induced cellular damage", Nano Lett, 5(12), 2573-2577. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z., Yao, T., Qu, C., Zhang, S., Li, X. and Qu, Y. (2019), "Photolyase-Like Catalytic Behavior of CeO2", Nano Lett, 19(11), 8270-8277. [CrossRef]

- Valdre, G., Moro, D. and Ulian, G. (2013), "Interaction at the nanoscale of fundamental biological molecules with minerals", Advances in Nano Research, 1(3), 133-151. [CrossRef]

- Vassie, J.A., Whitelock, J.M. and Lord, M.S. (2017), "Endocytosis of cerium oxide nanoparticles and modulation of reactive oxygen species in human ovarian and colon cancer cells", Acta Biomater, 50, 127-141. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. and Yang, F. (2023), "Nano-medicine effectiveness in pediatric patients: An artificial intelligence investigation", Advances in Nano Research, 15(2), 129-139. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F., Lu, Q., Huang, P.J. and Liu, J. (2019), "Nanoceria as a DNase I mimicking nanozyme", Chem Commun (Camb), 55(88), 13215-13218. [CrossRef]

- Yao, T., Tian, Z., Zhang, Y. and Qu, Y. (2019), "Phosphatase-like Activity of Porous Nanorods of CeO2 for the Highly Stabilized Dephosphorylation under Interferences", ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 11(1), 195-201. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

MTT test for 72 h as absorbance at 570 nm related to the control vs concentration of CeO2; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria. Red dashed lines indicate a viability range (80%–100%).

Figure 1.

MTT test for 72 h as absorbance at 570 nm related to the control vs concentration of CeO2; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria. Red dashed lines indicate a viability range (80%–100%).

Figure 2.

The TMRM test using flow cytometry. In blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria.

Figure 2.

The TMRM test using flow cytometry. In blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria.

Figure 3.

Images of citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 μM) in human fetal lung fibroblasts after 3 h of incubation; excitation wavelength, 370 nm; magnification, 40×.

Figure 3.

Images of citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 μM) in human fetal lung fibroblasts after 3 h of incubation; excitation wavelength, 370 nm; magnification, 40×.

Figure 4.

Transmitted light and fluorescence images of bare nanoceria and citrate-stabilized nanoceria in stressed with 10 μM H2O2 human fetal lung fibroblasts; magnification, 100×.

Figure 4.

Transmitted light and fluorescence images of bare nanoceria and citrate-stabilized nanoceria in stressed with 10 μM H2O2 human fetal lung fibroblasts; magnification, 100×.

Figure 5.

Intracellular ROS assessed with flow cytometry, in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 5.

Intracellular ROS assessed with flow cytometry, in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 6.

NOX4 expression as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-coated nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the TBP gene was used as an internal reference gene, the mean RNA amount was calculated from three experiments relative to control, the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 6.

NOX4 expression as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-coated nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the TBP gene was used as an internal reference gene, the mean RNA amount was calculated from three experiments relative to control, the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 7.

NRF2 expression as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-coated nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the TBP gene was used as an internal reference gene, the mean RNA amount was calculated from three experiments relative to control, the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 7.

NRF2 expression as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-coated nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the TBP gene was used as an internal reference gene, the mean RNA amount was calculated from three experiments relative to control, the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 8.

NF-κB expression as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-coated nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the TBP gene was used as an internal reference gene, the mean RNA amount was calculated from three experiments relative to control, the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 8.

NF-κB expression as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-coated nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the TBP gene was used as an internal reference gene, the mean RNA amount was calculated from three experiments relative to control, the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 9.

Biomarkers of oxidative damage and double-strand breaks relative to control (the cells with no nanoceria added) quantified with flow cytometry as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-coated nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours; the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 9.

Biomarkers of oxidative damage and double-strand breaks relative to control (the cells with no nanoceria added) quantified with flow cytometry as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-coated nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours; the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 10.

BRCA1 expression as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the TBP gene was used as an internal reference gene, the mean RNA amount was calculated from three experiments relative to control, the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 10.

BRCA1 expression as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the TBP gene was used as an internal reference gene, the mean RNA amount was calculated from three experiments relative to control, the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 11.

BCL2/BAX ratio as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours. The mean RNA amount was calculated from three experiments relative to control (the cells with no nanoceria added); the TBP gene was used as an internal reference gene). Protein expression was assessed by flow cytometry. The significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 11.

BCL2/BAX ratio as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours. The mean RNA amount was calculated from three experiments relative to control (the cells with no nanoceria added); the TBP gene was used as an internal reference gene). Protein expression was assessed by flow cytometry. The significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 12.

Cell number vs. BRCA1 fluorescence in cells relative to the blank (medians) vs. incubation time for 1.5 μM bare and citrate-coated nanoceria; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 12.

Cell number vs. BRCA1 fluorescence in cells relative to the blank (medians) vs. incubation time for 1.5 μM bare and citrate-coated nanoceria; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 13.

LC3 expression as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the TBP gene was used as an internal reference gene, the mean RNA amount was calculated from three experiments relative to control, the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Figure 13.

LC3 expression as a result of incubation of HELFs with bare and citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 μM) within 1–72 hours; in blank experiments, cells were incubated without nanoceria; the TBP gene was used as an internal reference gene, the mean RNA amount was calculated from three experiments relative to control, the significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) is marked with ‘*’.

Table 1.

The effects of bare and citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 µM) on human embryonic lung fibroblasts.

Table 1.

The effects of bare and citrate-stabilized nanoceria (1.5 µM) on human embryonic lung fibroblasts.

| Parameter |

1–3 hours (short-term effects) |

24 hours (middle-term effects) |

72 hours (long-term effects) |

| Intracellular ROS (DCF fluorescence) |

↓ |

↓ |

↓ |

| NOX4 protein |

↑↓ |

↑ |

↓ |

| NRF2 protein |

↑↓ |

↑ |

↓ |

| NF-κB protein |

↑↓* |

↑ |

↓ |

| Oxidative DNA modification (8-oxo-dG) |

↑↓ |

↑ |

↓ |

| DNA double-strand breaks (phos-γH2AX protein) |

↑↓ |

↑ |

↓ |

| DNA repair (BRCA1 protein) |

↑↓ |

↑ |

↓ |

| Apoptosis (BCL2/BAX protein ratio) |

↓ |

↓ |

0** |

| Proliferation (PCNA protein) |

↑ |

↑ |

↑ |

| Autophagy (LC3 protein) |

↓ |

↓ |

↓ |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).