1. Introduction

Scholars associated with the findings used in this analysis have been involved in more than 60 ethnographic studies with more than 100 participating American Indian Tribes and Pueblos. These scholars conform their commitment to conducing these studies in order to more fully protect the heritage objects, places, and history of the participating contemporary peoples. As outsiders in space and time, we scholars confirm that a full understanding of these heritage issues cannot and perhaps should not be known; however, the broad outlines of their purpose and contemporary importance as ancestral heritage is essential for establishing culturally appropriate preservation methods and land management policies. Today most Native American heritage lands involved in this analysis are managed by USA federal agonies whose lands surround the Indian Creek Study Area (

Figure 1).

Nothing is more sensitive than the terms used to describe these heritage objects, places, and history. This analysis is thus titled

Celestial Light Marker, which is deliberately vague rather than more specific regarding function, time, and cultural affiliation (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

It is not known what kind of light the engineers intended to tell time with the stone marker. The light however is focused directly on the nearby natural sandstone wall with many rock peckings. It is not known if the marker itself changed in structure and function over thousands of years of ceremonial use. Based on past ethnographic studies with Native American representatives conducted at similar places as well as at this study area a few points can be surmised:

Celestial specialists including sky watchers and engineers were needed to produce this complex light marker and associated ceremonial areas,

Either day or night lights could have been marked,

Different celestial sources could have been involved such as stars, patterns of celestial objects, planets, our moon, and our sun.

The documented purpose for marking celestial light usually involves knowing the time and coordinating ceremonies needed to balance the world and help it sustain life.

2. Ethnographic Background Studies

Given the sensitive nature of this study, it is important to understand that the analysis is directly based and in keeping with approved tribal and pueblos who shared cultural information during four Celestial Light Marker studies (1) a solar calendar in Utah, (2) the sandstone arches and hoodoos in Arches NP, (

Figure 4) (3) the light marking structures at Hovenweep NM (Figure. ) and (4) the world famous time marker atop Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Park (Figure. ). These four Celestial Light Marker studies and our National Park Service funded study of Canyonlands NP and the Bureau of Land Management funded Indian Creek studies are the foundation of this analysis. Each of the ethnographic studies provided specific findings that are both illustrated and briefly discussed. The current analysis purports to understand the Indian Creek Celestial Light Marker in terms of (a) what it was, (b) when it was primarily used, and (c) why it was made. This analysis suggests it was a World Balancing geosite.

All studies focused on the traditional Native American uses of their ancestorial lands and why they created Celestial Light Markers. These markers were used to understand time. Such knowledge was needed and used by religious leaders for scheduling and coordinating ceremonies. In all cases, some ceremonials involved the control the weather and climate conditions that most influence agriculture economies that supported large farming populations. The snow and rain were an essential sourced for irrigated farming along streams and rivers; however, the warmer and wetter conditions from 500 AD to 1300 AD provided major support fo dry land farming. The latter style of farming was especially venerable to changes in regular patterns of rain and snow fall as well as the amount of water provided to the otherwise dry lands.

Given the scale of associated weather and climate change, World Balancing ceremonies would have occurred at this geosite location as well as other notable ones such as Sugarloaf Mountain on the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon (Van Vlack et al. 2024), Arches National Park (Arches NP) in Utah, Hovenweep National Monument (Hovenweep NM) in Colorado and Fajada Butte in Chaco Canyon National Park, New Mexico from AD 1200 -1300s.

Earlier human responses to changes in the environment including those associated with climate shifts are documented with mid-Holocene rock art from Patagonia (Villanueva et al 2024), Menhir erection and relocation in Neolithic coastal Britany (Tilley 1997, 2004, Volcanic Eruption from 2360 BP in Southwest Brithish Columbia, Canada (Angelbeck et al. 2023, Wilson, Angelbec, and Jones 2023)., 16,000 year old rivers shifts in the Coso Mountains, Calfornia (Whitley 1997, 2013), and Pleistocene in the Great Basis (Russka 2025). So there is ancient and contemporary documentation regarding the human ceremonial responses to climate change such as documented in this analysis.

2.1. Case One: Solar Calendar in Utah

The solar calendar located in a high narrow sandstone fin on a mountain side above major farming areas along a river has recently been included in a publication, so details are not repeated here. It is important to note, however that both the stream of celestial light passing into the cave and a large sandstone slab where it was marked were engineered to function as markers.

2.2. Case Two: Arches National Park, Utah

The area called Arches National Park contains more than 2000 places where upright sandstone features have eroded to produce what the NPS calls a

window and Native representatives participating in the ethnographic studies call a

portal (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Arches is a term they both uses. The 2,000 arches face all directions and so open to many celestial feature as well regional sky islands. Native people believe the arches were made at Creation to be used to mark the times for ceremonies, as a place for ceremonies, and a portal to other times and dimensions. Again, the complexity of these celestial light markers has been discussed elsewhere, but key for these analyses is that markers include hoodoos as well as arches. Also, the study established that night lights and events were key.

2.3. Case 3: Hovenweep National Monument, Utah and Colorado

Hovenweep National Monument is composed of celestial light markers including engineered walls with holes through them to permit the passage of light, marking relationships between the shadows of buildings, and tall multistoried towers build to both view the sky, pray to distant sky islands, and conducted ceremonies. The seven set of buildings are at canyon heads near springs that flow to streams

Structures associated ceremonial underground kivas were concentrated at spring at the heads of small canyons. Structures at these locations had tall multiple story square towers and were surrounding by square or round towers on the canyon rim. These structures were used, according to tribal representatives, for telling time and praying for rain and snow. Prayers asking for rain and snow were sent into the nearby spring and then descended into small steams where they then flowed to the San Juan River, and then to the Colorado River. The prayers were then carried by the big river to the Pacific Ocean. In the ocean these payers were given to the water and clouds which returned to the Sky Islands and wide dry plains. While beyond this analysis there are useful ethnographic comparisons of the cultural meaning of rocks and springs among the Cherokee (Loubser and Ashcraft 20 262-265)..

Other prayers were sent from the tops of towers directed to the Sky Islands, which were asked to talk with the clouds from the ocean and request that they bring the rain to the mountains and agricultural fields and to do so when most needed by the crops.

Hovenweep itself in all its complexity was a place for the religious leaders to again gain control of the weather as they had in earlier years. Now with more frequent and longer droughts, and rain falling at times when it was least useful for agriculture, the priest class of the Mesa Verde World came together in the AD 1200s to make a ceremonial village like no other. As Hovenweep structures were constructed the buildings and kivas combinations were used to talk with the water and pray for better weather. The structures were among the finest every made. Clearly, they were the produce of both skilled construction engineers, and each was planned by astronomers to capture and mark Celestial Light. Some examples are provided here:

One of the Hovenweep canyons at Cajone spring structures were built on the canyon edge and on a single massive natural stone in the canyon bottom near the spring (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). All structures on the canyon edge have walls containing holes through which emit celestial light that marks time (

Figure 8). The structure has primary outside walls that cast shadows against each other, and in so doing they tell the time.

Nearby the structures on the canyon edge is an engineered small rock shelter located under the canyon rim. This rock shelter has an engineered outside wall that is designed to capture celestial light that shines through it into ground stone depressions each of which represents one of the seven planets in our solar system (

Figure 9). Nearby is a shallow cave with a stone-built wall having a two large, planned holes which cast light on carved holes representing planets.

2.4. Case Four: Fajada Butte, Chaco Culture National Historic Park, New Mexico

In the early 1990s the NPS funded an ethnographic study of a geosite called Fajada Butte which is located in a geoscape (Chaco Canyon), and in a geo-region (the Chaco Cultural Interaction Sphere). Without question based on Native responses, these places are framed by the topography and geology of the area. The geo-trails are primarily for pilgrimage and ceremonial and radiate for hundreds of miles in all direction. All these geo components are now recognized by scholars and Native people alike as contributing to the Chaco Culture World and so therefor the current name Chaco Culture National Historic Park is accurate from multiple perspectives.

Before this ethnographic study of Fajada Butte, it primarily was known as the location of one of the most complex solar and moon light markers in North American (Sofar, Zimmer, and Sinclair 1979, 1982). After seven tribes and pueblos participated in the ethnographic study, Fajada Butte was understood as much more complex than just the Celestial Light Marker. The Native findings were reviewed and approved by all their cultural departments and governments (Stoffle et al. 1994). Among the four Celestial Light Marking studies this one was similar in important ways. It was initially focused on what was then a famous light marker on a charismatic butte. The Native participants agreed that such a marker is only understood by objects, places, and landscapes within which it is culturally and historically imbedded. One cannot understand the geosite of Fajada Butte and the light marker alone.

The following is a list of the top 11 culturally significant components of Fajada Butte according to on-site visits by tribal and pueblo representatives. These components are organized from the top down to the base of Fajada Butte. The Sun Dagger is important but only one among other light markers. For some representatives the rooms for astronomers was the key purpose of the set of components. The contemporary Eagle Nest was generically viewed as a constant between the heritage of the Butte complex from Creation and early times through today. The prayer shrine on top of Fajada Butte is used for contemporary Native communities to transport prayers to other dimensions and places.

prayer shrine on top of Fajada Butte

contemporary ceremonial area on top now used by the Native American Church

eagle's nest edge rim of Butte

Sun Dagger just below top of Butte

rooms where astronomers lived along the edge of upper side

calendars and symbols near roofs of astronomers' rooms

minerals mostly on top

hogan on lower flank of Fajada Butte

petroglyph panel away from the base of Fajada Butte

support family living and cooking quarters - north and south of Fajada Butte

plants used by American Indians are widely distributed around the base of Butte

It is important to note that all of these 11 cultural components were perceived by Native representative to be a part of the reasons Fajada Butte was and is an important heritage geosite for Native American today. A key observation and cultural interpretation of Fajada Buttee is the difficulty to intellectually resolve much less merge the epistemological differences between western science and native science. The following are two examples of this difficulty:

3. Tsa'aktuyga (A Hopi Perspective)

Ta'a, pay nu' yev tuyqat tungway'a, hal owi, pan itam aw wuuwaya kye i' pam

himu papiq oovi piw tu'awi'ytaqw pam himu taawa haqe' qalawmaqw

tsa'lawngwu; himu tiingaviwngwu. Pam songa put aw awiwaniqw paniqw pay

oovi itam panwat tungwayani, Tsa'aktuyga. Papiq pam ang tuvoyla'at pe jryunggw

haqe' taawa pakye', haqe' galawmagw put pant hapi tsa'lawngwu so'onge yaapiq

ooveqa. Pay yan itam son it qa aw oovi panayani, Hopivewat tsa'aktuyga.

Tsa'akmongwit hapi i' tiingappi'ata, tsa'lawpi'at piiwu.

Translated by Hopi Scholar Emory Sekaquaptewa)

Verily, I have given a name to the rock point here, that is to say, we have concluded that this is something that represents the place from which someone [appropriate] makes his announcements giving the positions of the sun [from season to season]; so that preordination of life- giving activities [i.e. ceremonies, planting, harvesting, etc.] can be given. It is undoubtedly used for that purpose, that is the reason we have given it the name, Tsa'aktuyqa. There are line drawings [on the rock] up there for marking sunsets [on the horizon], telling the positions of the sun that he must announce from up there. This is the way we are going to enter it [in the report], that according to Hopi practice this is the announcing point. The Crier Chief uses this as his place of declaring preordinations, his announcements.

Figure 10.

Fajada Butte, NPS Chaco Culture National Historic Park.

Figure 10.

Fajada Butte, NPS Chaco Culture National Historic Park.

4. A Western Science Perspective

At the summer solstice, before midday, the shafts of light illuminating the cliff face interact with the large spiral in a visually striking manner (UCAR 2024). Shortly past 11:00am local solar time, a small spot of sunlight first appears above the large spiral. It lengthens vertically into a very narrow, downward pointing elongated triangle (or "

dagger"). The dagger continues growing and moving downward until, around 11:15am, it cleanly bisects the spiral almost over its entire height. At this point the Sun is high enough in the sky for the overhang above site to begin casting a shadow on the slabs, and in doing so cuts off the upper end of the dagger (

Figure 11).

A lesson from these foundation Celestial Light Marker studies, is that while some commonality can exist between western science and native science these are difficult to resolve. Similarly, while multiple tribes and pueblos often do have a common heritage understanding of a geosite, each cultural group has different interpretation of geosites including their origin, history, and purpose.

5. The Study Area

Some of the tribal and pueblo interpretations used in this analysis are specific to this ethnographic study area, other interpretations are applicable to the surrounding culturally region or geoscape, and still others refer to general Native American epistemology about how these heritage places are temporally related through thousands of years and spatially connected across hundreds of miles. Similarly temporal scales vary in interpretations. Even the concept of time is regularly disputed. These different scales of interpretation occur because Native cultural landscapes exist without regards to western contemporary boundaries of space and time (see discussion later).

In this analysis the broader region is called the American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River (AICC) (

Figure 12). This term reflects an ancient functionally integrated cultural region that has been defined at the request of tribal and pueblo participants who wish that through this designation others will better understand Native cultural heritage objects, history, and places. These Native representatives stipulate that their heritage should be interpreted, understood, and managed holistically as these were done aboriginally.

The AICC region where Native Americans lived and conducted ceremonies for tens of thousands of years includes the Abajo Mountains to the south, the La Sal Mountains to the northeast, 2,000 sandstone arches in Arches National Park to the northeast, the Henry Mountains to the west, and the major traditional trade and travel trail (that is a geotrail) that crosses the Colorado River. This ancient and primary geotrail crosses the geoscape at Moab Valley but it subsequently crosses the Green River to the north, the Mancos and La Plata Rivers to the east near Mesa Verde, and the San Juan River to the South. This ancient geotrail connect the broader region physically and spiritually.

According to hundreds of ethnographic interviews, the AICC and its component features have been culturally important places for all the participating Native American representatives since Time Immemorial or Creation. Both ancient Clovis and Folsom and Clovis spear points have been found in the AICC area, but they do not define the earliest occupation of the AICC. Recent geoarchaeology studies have documented the presence of Native people in an even broader region called the Colorado Plateau of the Southwest United States. Therefore, the broadest temporal frame for this heritage analysis is operationally defined as the late Pleistocene, which occurred between 128,000 BP and 11,700 BP, and the Holocene from 11,700 BP to modern times. Scientific studies document Native Americans by at least 37,000 BP with geoarchaeology dates of 23,000 to 21,000 BP at White Sands, New Mexico (Bennet et al. 2021; Pigati et al. 2023) and 38,900 BP to 36,250 BP at the Hartley locality, a mammoth kill site situated near the Rio Puerco, New Mexico (Rowe et al. 2022). These geoscience dates indicate that Native peoples of this region experienced this environment as both a massive wetland filled with lakes, rivers, and swamps and later as an arid desert with small streams and artesian springs (Grayson 1993). Time keeping and celestial marking would have been adjusted to understand climate changes (Villanueva et al. 2024) and massive geological changes would be remembered with oral history during these periods (Angelbeck et al. 2024; Wilson et al. 2024).

This heritage analysis builds on the burgeoning academic literature that has responded to the United Nations’ call for the identification of geological places and landscapes as cultural heritage deserving preservation (Brocx and Semenluk 2017). The ICUN and the WCPA have a Geoheritage Specialist Group that has documented the need for such new heritage preservation approaches (IUCN WCPA 2024). This need is illustrated by the 20 published peer reviewed papers in the Special Issue of the journal Land entitled Geoparks, Geotrails, and Geotourism – Linking Geology, Geoheritages, and Geoeducation edited by Brocx and Semenluk (2022). This Special Issue included studies from Europe, Australia, USA, Latin America, and Asia. Subsequently, published articles on this topic are illustrated by Geoheritage and Cultural Heritage Overview of the Toba Caldera Geosites, North Sumatr, Indonesia (Muzambiq et al. 2024). These studies (Moretti et al. 2021) document a range of complexities involved in preserving, interpreting, and managing complex geoheritage. The Geology profession through the International Commission on Geoheritage (IUGS 2024) has responded by identifying significant geosites around the world using both their science and humans’ significance as criteria (IUGS 2024).

The current analysis draws on these new Geoheritage approaches for the identification, interpretation, and management Earth Places because the structure and function of the Celestial Light Marker significantly depends on the geology and topography of the lands involved.

All of the participating tribes and pueblos have an ongoing cultural association with the AICC (

Figure 12). They have stipulated that this is a culturally and functionally integrated area that is interlaced with pilgrimage trails and has been so since Time Immemorial. For comparison with the Cherokee people of eastern USA see Loubser and Ashcraft 2023: 252-255). The term geoscape is used for the AICC given the area’s many special topographic features that structured it from a cultural perspective. Participating tribes and pueblos stipulate that they are from this region, even if they live elsewhere today, and that they continue to keep the region and their connections with it alive in their ceremonies and prayers. They maintain that this is a living ceremonial area that was established at Creation for the use of all Native peoples. Like the people themselves, these geological and topographical places remain alive, and all are committed to their original purpose of providing balance to the world.

5.1. The Mesa Verde World

Late 19th Century and early 20th Century scientific efforts to understand the character of the Native American people who lived in this region and made its spectacular stone structures began on a large south sloping mesa with deep canyons that is called Mesa Verde (

Figure 13). These stone cities built in the alcoves of high canyon walls on this isolated forested mesa caught the imagination of the world as expedition after expedition explored the mesa excavating the structures and carrying away human remains and artifacts (

Figure 14). Cliff Palace is pictured here under a canyon rim alcove is surrounding by cedar forests (

Figure 15). The name Cliff Palace reflects the notion that the ceremonial or political elite lived here and elsewhere on the isolated mesa.

Eventually U.S. national concerns that European museums were stealing trainloads of U.S. heritage caused the passage of the Antiquities Act of 1906 (US Congress 2025) which gave the US president the power to define national monuments and regulate archaeological excavation and removal of artifacts. The charismatic Mesa Verde stone cities in fact would become the center of Southwestern Archaeology research and teaching which would stimulate theories and speculation about why Indian people chose to live on this high mesa and build large cities in isolated places.

Today, Mesa Verde and its heritage are managed by the U.S. National Park Service, and the park has become a U.N. World Heritage Site. The isolated mesa top communities and way of life remain wildly popular for millions of tourists. The term Mesa Verde society, however, has become somewhat of a distraction to the emerging story of the much larger and more complex functionally integrated set of communities living elsewhere.

Mesa Verde society was influenced by the diverse geology and topography of the the isolated mesa with steep sides, high elevation, and dense forest. On Mesa Verde farming was a challenge because the mesa lacking large streams and even surface water, so rainfall was essential, and only limited irrigation was possible from springs, small streams, and engineered ponds. Large communities lived in sandstone alcoves, but many people lived in isolated farm homes.

Far away from this isolated mesa people lived in small, dispersed communities or rancherias, in the more open and expansive Great Sage Plain (See

Figure 16) where farming was largely supported by rainfall. A few large rivers such as the San Juan did support larger irrigated farming communities. Archaeological studies such as those associated with the BLM-managed Canyons of the Ancients National Monument (Canyons of the Ancients 2024) in Colorado. The new archaeology studies identified thousands of farming locations beyond Mesa Verde, and it became clear that the people of Mesa Verde were but a portion of a larger and culturally similar interconnected society that existed for hundreds of miles in all directions. Thus, the initial Mesa Verde archaeology studies were temporally and spatially too restrictive for understanding what life was like for the native people of the broader region.

After hundreds of years of population growth, which begin about AD 500, these small farm residences supported by dryland farming were increasingly moved according to the plans of religious leaders to be near Great Houses with large central structures, kivas, and dance grounds. This style of community life began to typify the region about AD 1050.

In order to make more accurate generalizations as well as distinctions in regional archeology, settlement patterns, and ecological variation, Noble (2006) and others (Varien 2006; Wilhusen and Glowacki 2017) reframed earlier theories into a much larger and more complex model of this region as part of a culturally, economically, politically, and religiously integrated society called the

Mesa Verde World (

Figure 16).

The Mesa Verde World model stretched west to east from the Colorado River in Utah, past Mesa Verde proper to east of the present town of Durango, Colorado. For purpose of this analysis, The Mesa Verde World also extended from north along the flanks of the La Sal Mountain Massif to the San Juan River in the south. The archaeologists called the region Mesa Verde World after the famous place name Mesa Verde.

While the isolated Mesa Verde is the term of reference of this archaeology region, most people lived somewhere else and there are no current arguments that it was the center of the region. The Great Sage Plain, for example, is located to the north and east of Mesa Verde and was a place of great agricultural productivity that supported large farming communities having large central ceremonial structures (Wilhusen and Glowacki 2017: 308). These large agricultural communities are located away from Mesa Verde are more typical of ones that existed throughout the broader Mesa Verde World.

Finally, in the early 21st Century archaeology surveys and excavations of the surrounding areas challenge the notion that Mesa Verde was the cultural center and replaced it with research findings that there were many other population centers with large ceremonial areas contain group kivas and dancing grounds. Evidence provides a view of these Great House centers would be concentrates under the guidance of religious leaders who guide the performance of ceremonial activities involving weather control in the hopes that tens of thousands of farming people would have bountiful crops.

Further evidence from four regional ethnographic research studies in Arches NP (Stoffle et al. 2016), Canyonlands NP (Stoffle et al. 2017), Hovenweep NM (Stoffle et al 2018), and Natural Bridges National Monument (Stoffle et al. 2019) document that Native American farmers lived and occupied a region west of the La Sal Mountains and south to Cedar Mesa. These studies now incorporate settlements located north of the Abajo Mountains extending to Salt Creek and Indian Creek in the Canyonlands area and the farm communities in Moab Valley. These populations lived beyond the boundaries posed by archaeologists in the earlier works on the Mesa Verde World, and certain criterial of that designation were not met. However, the communities and lifestyles were culturally similar and by including the communities along Cedar Mesa, the northern slopes of the Abajo Mountains, and the villages along the Colorado River, the population data suggest another 10,000 people lived within these northern areas. It appears that large farming communities situated in a culturally integrated regional society of approximately 80,000 people lived in the western and central Mesa Verde World.

These other population centers, located in open areas where large ceremonial centers with groups of kivas and community dancing grounds, would be concentrate under the guidance of religious leaders to perform ceremonial activities involving weather control. The 800-year period from 500 AD to 1300 AD was fraught with shifts in weather despite a wetter and warmer environment. So, the concentrated Big House settlements and ceremonial areas in the late in this period were occupied in the hopes that tens of thousands of farming people would have bountiful crops. Our data indicated that this was the primary social and environmental setting within which the Celestial Light Marker was a key feature.

In summary then The Mesa Verde World (Noble 2006: xv -xvii) was developed during the 800-year period from approximately AD 500 to AD 1300. The rise of the Mesa Verde World was preceded and built on a thousand years of experimentation with cultigens as a part of a horticultural economy that mostly relied on small scale plant management, natural food gathering and conservation, and hunting. The early portions of this period involved climate changes that included warmer weather and increased rainfall. Such a climate shift occurred throughout North America and thus resulted in dramatically improved dryland and irrigated farming conditions, population growth, and evolving social complexity.

The Post Mesa Verde World period began during the Little Ice Age and continued for hundreds of years from AD 1300 to the mid-1800s. A colder climate, less predictable weather patterns, and less rainfall made greatly reduced or eliminated the dryland and irrigated farming that had supported the earlier rise of populations. So, during the Little Ice Age Native lifestyles and populations sizes were quite different than they had been during the previous 800 years. Native American Indian social, demographic, and cultural responses to the Little Ice Age are contested by some scholars, however, while some speculate that the region was no longer occupied, for example see Leaving Mesa Verde (Kohler, Varien, and Wright 2010). Native American representatives who are involved in our ethnographic studies, however, maintain that they never abandoned this ancestorial homeland, even though some people did move to other areas for their primary residence. Other Native American representatives maintain that they never left their traditional homelands but did change their lifestyles.

In this analysis we argue that the Celestial Light Marker was primarily used in the ceremonial activities of the people in the surrounding AICC and Mesa Verde World. It may also have served similar functions before and after this time but given the centrality of celestial light calendars for helping to structuring weather ceremonies related to agriculture it must have occupied a central position during the period ending the Mesa Verde World.

6. Methods

A total of 522 ethnographic interviews provides the foundation of this Celestial Light Marker analysis including 316 NPS and 206 BLM Native American interviews. Ethnographic studies funded by Federal Agencies were conducted by trained cultural anthropologists from the University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ (Stoffle et al. 2017), Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, and Heritage Lands Collective, Cortez, Colorado (Van Vlack et al. 2024). An Ethnographic Overview and Assessment (EOA) study was funded by the NPS and conducted at Canyonlands National Park. This EOA included Indian Creek and viewscapes from the park. The Bureau of Land Management Ethnographic Partnership study and Moab Ethnographic studies focused on management areas surrounding Canyonlands, especially Indian Creek area and the Abajo Mountains and to the north along the Colorado River.

No confidential information was sought during any of the involved ethnographic studies. Participating tribally appointed representatives, their cultural departments, and governments reviewed, edited, and approved for public use their own chapters in these reports.

6.1. Canyonlands National Park EOA

The Canyonlands NP Ethnographic Overview and Assessment (EOA) occurred from 2015 until 2016 (Stoffle et al. 2016). The study involved 6 tribes and pueblos including the (1) Pueblo of Zuni, (2) Southern Ute Indian Tribe, (3) Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, (4) Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, (5) Navajo Nation, and (6) Hopi Tribe. Representatives of each tribe and pueblo received their own confidential interviews conducted by a trained ethnographer. A total of 316 formal Data Collection Events occurred.

The overall objective of the EOA was to prepare an ethnographic report for Canyonlands NP that documents and evaluates culturally significant American Indian objects, natural resources, places, and cultural landscapes. These ethnographic findings can be used to support public education and park interpretation to increase understanding of American Indian tribes’ and pueblos’ traditional connection with the park. The findings of this report will be available to the public (no sensitive cultural information is being sought) and be used as input into park management plans and environmental assessment work, interpretation planning, and in other park resource related management decisions.

6.2. BLM Utah Monticello Field Office Ethnographic Information Partnership

The two-part study focuses on how to best inform the Monticello Field Office (MFO) officials regarding Native American tribal connections to the Cedar Mesa area and how they have utilized the range of ethnographic resources found within this complex landscape. To accomplish these goals, the BLM funded Van Vlack through the Heritage Lands Collective to design and conduct a two-phased research study. Phase One focused on building an ethnographic literature review of traditional tribal associations with MFO, including the greater Cedar Mesa area (Van Vlack, Yaquinto, and Kelley 2025). Phase Two involve tribal site visits to places within MFO including Indian Creek and Bears Ears National Monument (Van Vlack et al. 2025).

A second BLM funded studies was entitled Moab Ethnographic Study: Southern Paiute and Ute Perspectives (Van Vlack et al. 2023). This study occurred from 2019 until 2023. This study involves Native American cultural landscape perspective of the lands around the town of Moab, Utah and in between Arches and Canyonlands National Parks. Also included were lands to the north such as the Book Cliffs. For this project, HLC brought out traditionally associated tribes to a range of places throughout the study areas and interviewed tribal representatives regarding cultural history meaning, traditional/current use, and management recommendations. The second study involve Southern Paiutes from the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah and Ute Mountain Ute representatives. These appointed cultural experts provided cultural perspectives on several places including those in Indian Creek (Van Vlack et al. 2023) Interviews totaled 102.

6.3. Issues of Ethnographic Analysis

A critical methodology issue raised in this analysis here and elsewhere is getting the analysis complete. In general, there is a tendency in technical reports to get to ‘the answer” and sometimes this is more or less possible. More commonly is the issue of cultural multivocality. Two examples are provided here.

6.4. Group Interpretation Agreement

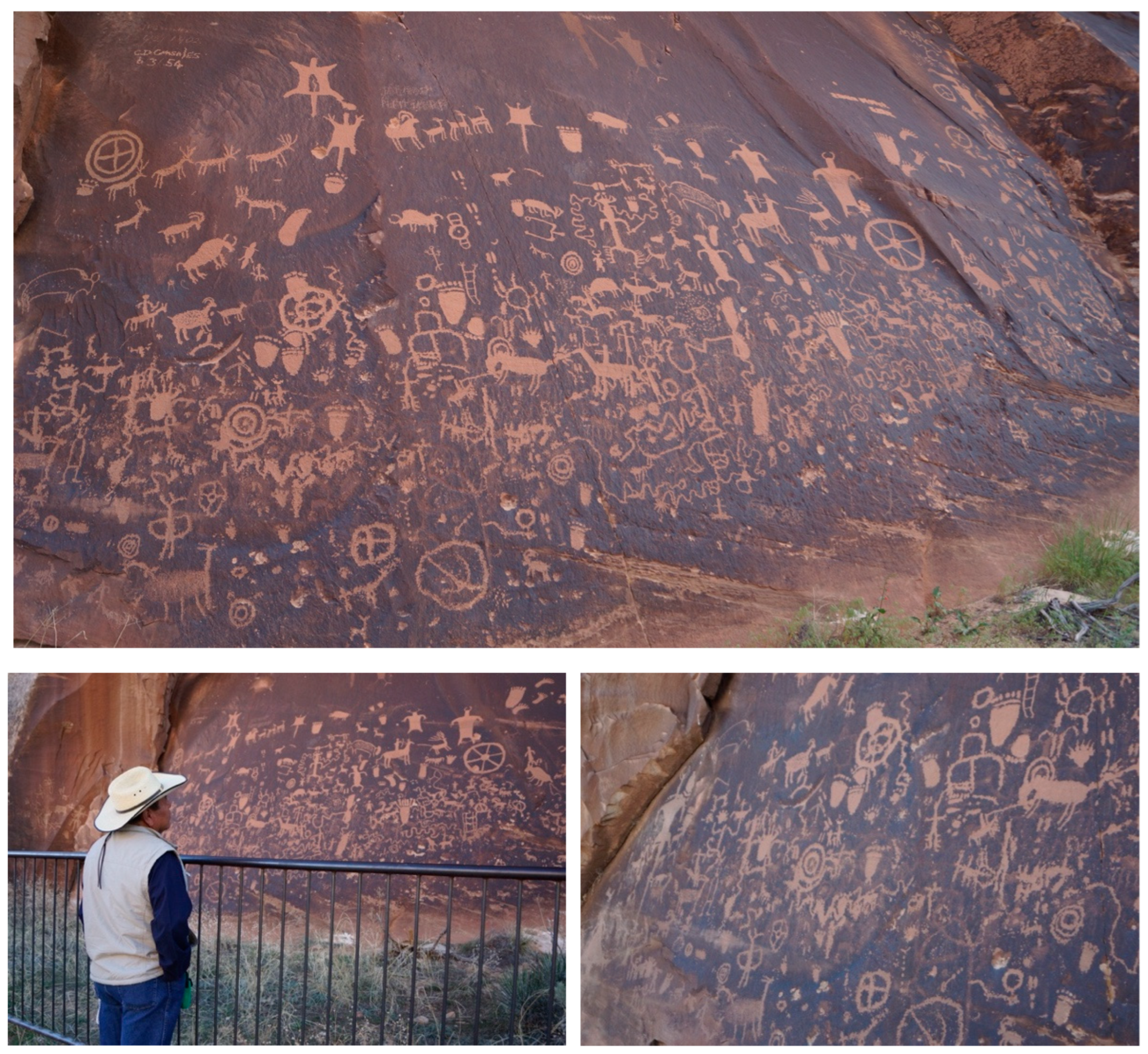

Native representatives identified a pecked spiral and sandal footprints at the Moab Panel as having been left by their migrating clans who returned to their respective pueblos. All American Indian people identified footprint peckings, such as those at Newspaper Rock, as part of their physical and spiritual travel. Similarly, spiral peckings, which are located throughout the greater Arches NP and Canyonlands NP region, were noted as significant cultural features representing travel (

Figure 17).

6.5. Tribal Specific Interpretations

In addition to general agreeing regarding the meanings of some peckings, there were others that had widely different interpretations. At one large pecking panel in Canyonlands the Zuni identified a spatially isolated pecking as representing their origin up a reed (called Phragmites) into the present World (

Figure 18). The reed also grows in the wetlands nearby. The combination of the origin emergence reed pecking and the contemporary presence of the Phragmites reed made the area culturally special to the Zuni (

Figure 18).

At the same rock panel are pecking of people riding horses (

Figure 19). These peckings were interpreted as repressing Utes and both they and the NPS call this the Ute Pannel, and both have no interpretation of the Phragmites pecking.

The issue of “picking a story” from the data is widely discussed by scholars. The best resolution, in our opinion, is to present as generally agreed some interpretations and widely different perspectives by others. The key is having the representatives, and their governments review the multivocal presentation in the report.

7. The Celestial Light Marker

The Celestial Light Marker, which is the focus of this analysis, can only be understood as a functionally integrated component of the land, the people, and the history of this region; referred to above by the term The American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River (or AICC) and Western Mesa Verde World. Native people interviewed in this study viewed this region as a special component of Creation. It has natural elements that made it possible for Native people to thrive, as so their large communities filled the valleys and for 2,000 years it did so with populus irrigated farming communities.

Central here is water and given our operational definition of the analytical these natural features have existed in various forms since the late Pleistocene and through the Holocene. Rivers, lakes, wetlands have always provided habitat for birds, fish, mammals of all sizes and variety including Mastodon, an image of which is pecked into a sandstone wall near the town of Moab. The rapid changes in elevation stimulate a variety of ecozones and the diverse and abundant flora they support. The Colorado River has carved deep, vertical and almost impassible canyons which line its banks for hundreds of miles upstream and downstream. At the AICC there are no canyon walls on either side of the river and the smooth bottom results in quiet water that is easily passible year-round. In the winter today and certainly in the past, the quiet river often freezes over, and it can be easily crossed. The major cross country AICC trail is followed by the Old Spanish Trail, regional roads, and now major highways along the ancient lines of least residence it defined.

Indian Creek has been interpreted by Native representative as an area primarily used for ceremony (

Figure 1). The headwaters of Indian Creek are the Abajo Mountains and Elk Ridge Sky Island and at the river mouth it joins the Colorado River. The neighboring Salt Creek to the west supported massive residential communities based on dryland and irrigated farming. Newspaper rock is an almost unique rock pecking site where Indian Creek Canyon begins and subsequently is lined with almost contestant rock peckings on the canyon rim and walls. Lower down river (upriver to the north) is a Ghost Dance site, which was probably chosen because of being a traditional Round Dance ceremony area. Further downstream there is an area for curing that contains a large medicine rock. The Celestial Light Marker is about a mile further downstream.

The Celestial Light Marker encompasses 12.7 square miles of socially constructed and physically engineered geoscape. This area roughly measures from east to west at 4.02 miles and from north south at 2.73 miles. Elevations are key in defining views and capturing light. From sea level to its top, the north peak is 5,612 feet high. The north peak from its mesa base to its top is 6,242 feet in elevation. The mesa base of south peak is 5,461 above sea level, and its top is 6,074 feet in elevation.

The Celestial Light Marker spans Indian Creek which flows to the north at 5,128 feet above sea level (

Figure 20). The marker sits at a fallen mesa top remnant on a lower ledge at 6,263 feet high. Behind the Celestial Light Marker is a mesa at 6,601 feet above sea level. Some features of the geosite are presented next with minimum interpretation and none that exceeds understandings of this geosite from interviews with Native representatives. The exception to this point is the speculation that the slabs at the marker have been moved and set in place. This is argued based on the presence or lack of presence of desert varnish and lichen which is a hybrid colony of algae or cyanobacteria.

7.1. Fallen Mesa Remnant

The Celestial Light Marker is a component of a nearby mesa (

Figure 21), a portion of which has fallen. The remnant mesa cap rock is isolated on what was once another geological feature but not is a narrow sandstone ledge (

Figure 22). The sand on top of the ledge is smooth and level contributing to the developments of a ceremonial dance ground nearby. The broken piece of mesa cap contains minerals underneath including the purpose clay soil that is valued by several pueblo peoples for ceremony.

7.2. Upturned and Supported Stone Slab

On the south side of the fallen Mesa caprock is a slab of sandstone which has been engineered to capture, guide, and mark celestial light from the peaks to the west (

Figure 23).

It is speculated that at least three of the sandstone slabs have been engineered from a formerly position where they resided for a sufficiently long period that Lichen grew on their upper surfaces (

Figure 24). The light pointer, the rock supporting the pointer, and the slab on which pecking have been placed to received light from the pointer all have surfaces without either weather or lichen.

7.3. Celestial Light Marking Peckings

To the east of the engineered sandstone pointer the light is guided to a flat approximately six feet tall sandstone slab which is a apparently naturel component of the fallen mesa caprock (

Figure 25 and

Figure 26). Light guided to this panel would derive from the west. This large sandstone block appears to have been engineered to be in their current places given the face towards the west that receives the light from the west and contains peckings is covered with Deserts Varnish and the face to the north does not. Desert Varnish occurs when the sun facing surface of a rock or stone remains in place for thousands of years and has been transformed by the constant radiation and heat. The close up of the face documents a sharp line of Desert Varnish that is sharply contrasted with a north facing surface that has no Desert Varnish.

The large boulder containing the west facing peckings is physically touching the larger north facing surface of the mesa remnant (

Figure 27). The west facing face does not have lichen on it but the north face does have lichen. That north facing remnant contains pecking but light from the engineered marker does not currently reach that rock wall. Lichen is growing on the north face but not on the west face, suggesting the latter stone was moved to provide a location to make peckings that can receive light.

7.3. The Dance Grounds

The fallen mesa top remnant sits on a hard resistant sandstone ledge which both fully supports the light marker and a parallel surface that extends out to the north for about 260 feet before it curves to the east thus establishing a corner which defines the dance grounds (

Figure 28). The surface of the dance grounds is solid underneath and flat but generally composed and covered with soft fine sand. The dance ground is covered with chert flakes, pottery pieces, shell bead fragments, chipped stone and yellow ochre pieces (

Figure 29 and

Figure 30).

7.4. The Bracketing Peaks

From all points on the dance grounds there is a clear vista to the south up toward Indian Creek, to the west including the two peaks and the mountains beyond and to the north along the Indian Creek towards the Colorado Rive, and to the east up the sharp face of the mesa. The Celestial Light Marker is connected to light that comes from between or near the two peaks illustrated in

Figure 31.

One elder shared the following when he first viewed the area from the highway:

I am just speculating but, of these two points [Six-Shooter Peaks], I am sure there is something there, a site or something that uses these two as a calendar. Maybe the sun goes far to the left during the summer solstice and comes back during the winter solstice, in between the two. I am sure that it is very significant in some way during that time of the year. There may be something to the west of this area.

Another elder pointed out:

So that [solar panel] is the observation point. When you have something like that, there is probably something like the mounds [in Indian Creek] you guys just passed. When you get to that point, you look west and east. There is going to be something prominent, either a structure or something there, or a shrine that they used in ceremonies. So that would tell them the times of year. When it reaches its point, then certain ceremonies or things would happen.

8. Analysis Summary: Ten Key Features

The following are ten key features of the Celestial Light Marker which adjoins Canyonlands National Park in Utah. These cultural, social, and topographic features have been chosen based on ethnographic interviews of this Celestial Light Marker, its immediate surroundings, and where these are situated in the land-based geoscape termed for this analysis the American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River. These key features are:

Located in a spectacular geological landscape or geoscape.

Involve views of distant sacred Sky Islands, which are snowcapped mountain.

Span Indian Creek, which is a spiritual area that (a) derives from the Abajo Mountains, a sky island, (b) contains miles of continuous rock peckings and paintings, and (c) is a tributary of the Colorado River.

Are visually bracketed to the west by tall and narrow sandstone Six-shooter Peaks.

Receive solar system daytime lights which set in a u-shaped dip between the peaks and solar system night lights which rise and set as planets, stars, patterns of lights, and the Milky Way.

Is built from a fallen remint of a 6,601-foot above sea level mesa but persists and a geosite isolated on a narrow high ledge above Indian Creek.

Associated with a large flat dance and ceremonial area.

Near populus ancient Native American irrigated farming communities

Within the view scape of lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management and the National Park Service.

Touched and valued by millions of national and international tourists including hikers, ecologists, archaeologists, and technical rock climbers.

9. Indian Creek Geoscape

Indian Creek is an integrative geoscape with which we can better explain the Celestial Light Marker that spans it. Indian Creek is considered a spiritual geoscape and thus primarily contains geosites used for ceremony. Currently based on archaeology and ethnographic research the Indian Creak geoscape is known to have the following geosites (1) Newspaper Rock, (2) Shay Canyon Peckings, (3) a Round Dance site probably used as a Ghost Dance Site in 1890, (4) a Medicine Area with a Doctor Rock, (6) a Ceremonial Preparation cliff face with structures, and (6) a ceremonial support community Mound with kivas and structure. Most of these geosites are well known, however only three are analyzed here.

9.1. Geosite One: Newspaper Rock

The pecking location called Newspaper Rock is located in the upper stream portion of Indian Creek as it descends from the Abajo Mountains (

Figure 11 ). Multiple peckings on a single hard rock panel are rare in the region. Native representatives interpreted the whole place but tended to focus on symbols they recognized from their heritage like the Utes responding to the person on horseback. All agreed that this location was culturally important and connected to their tribal heritages.

Medicine and food plants grow in abundance at this location and the former are especially located under the panel behind the tourist fence. The area is wet being near the stream and surrounded by large cotton wood trees. All tribes value the plants of the area and many like the cotton wood trees are used in ceremony.

According to a tribal elder:

The other ones, the circles with asterisks inside of it, some of those represent all edible flowers before they bear fruits. See that is why there is abundance here. And when you see all these associated, next to the baby footprints, it is telling us there is abundance. Especially the left handprint, see that left handprint right there? Left hand is a feminine symbol. It means prosperity, it means longevity everything good is a left symbol. A right-hand symbol is completely the opposite. That means challenges. It is masculine. It also means strength or power. The left hand is everything good. Especially if you see baby footprints or handprints next to that. It is really a good story written on this side.

According to a tribal elder,

[Newspaper Rock] is saying a lot. A lot of activity going on, like hunting buffalo, deer, and bighorn sheep. A lot of it is drawn over old inscriptions. See the dark ones are underneath and the light ones are on top? See the man on the horse? I believe the most recent ones are Ute.

According to a tribal elder, “Those creatures, those are certain dances that have happened. That is my interpretation. Probably a dance.”

According to another tribal elder:

It is a good name, newspaper, but we call them libraries of our history. Our ancestors left this information behind so that in the future, when their children, us, come back, we can identify what they left behind. I am really thankful that our ancestors had the foresight to look into their future and leave information like this behind.

One tribal elder said, “That one up there definitely has his Puha from the deer. See him, deer head? He could have been the buckboss.”

Another tribal elder added:

The footprints and then the handprints, especially the left handprint is a very good symbol. And then baby footprints are a really good sign. There are certain styles of footprints that are modern versus ancient. The one on the left is ancient. This one I think is relatively old. See those baby foots? It symbolizes something, a very good life that they had at that time. A lot of children were born, really good crop and plenty of game, stuffs like that.

9.2. Geosite Two: Medicine Area and Doctor Rock

Along Indian Creek a few miles from Newspaper Rock and the Canyon with the peckings is an area recognized as having been used for medicine. Central to it is a large, isolated Doctor Rock (

Figure 33) On one face of the Doctor rock are a series of peckings (

Figure 34) The top of the rock can be accessed through a series of steps carved into the rock suggesting it was where the medicine occurred.

The Doctor Rock is tall and steep sided. Our ethnographic interviews at other Doctor Rocks such as at (1) Eagle Head in Escalante Valley (Stoffle et al. 2024), (2) the tonal portal engineered flack rock on the Nevada Test Site (Stoffle et al. 2024), and (3) the volcanic plug called Vulcans Anvil located in the middle of the Colorado River, Grand Canyon National Park (Van Vlack et al. 2024), document that doctoring rocks are ceremonially used from their tops. In this Indian Creek Doctor Rock case steps to the top have been cut up one side of the Doctor Rock (

Figure 35). Normally access to the top by a person with a medical or spiritual need requires them to be on the top of the rock and there doctored by multiple persons.

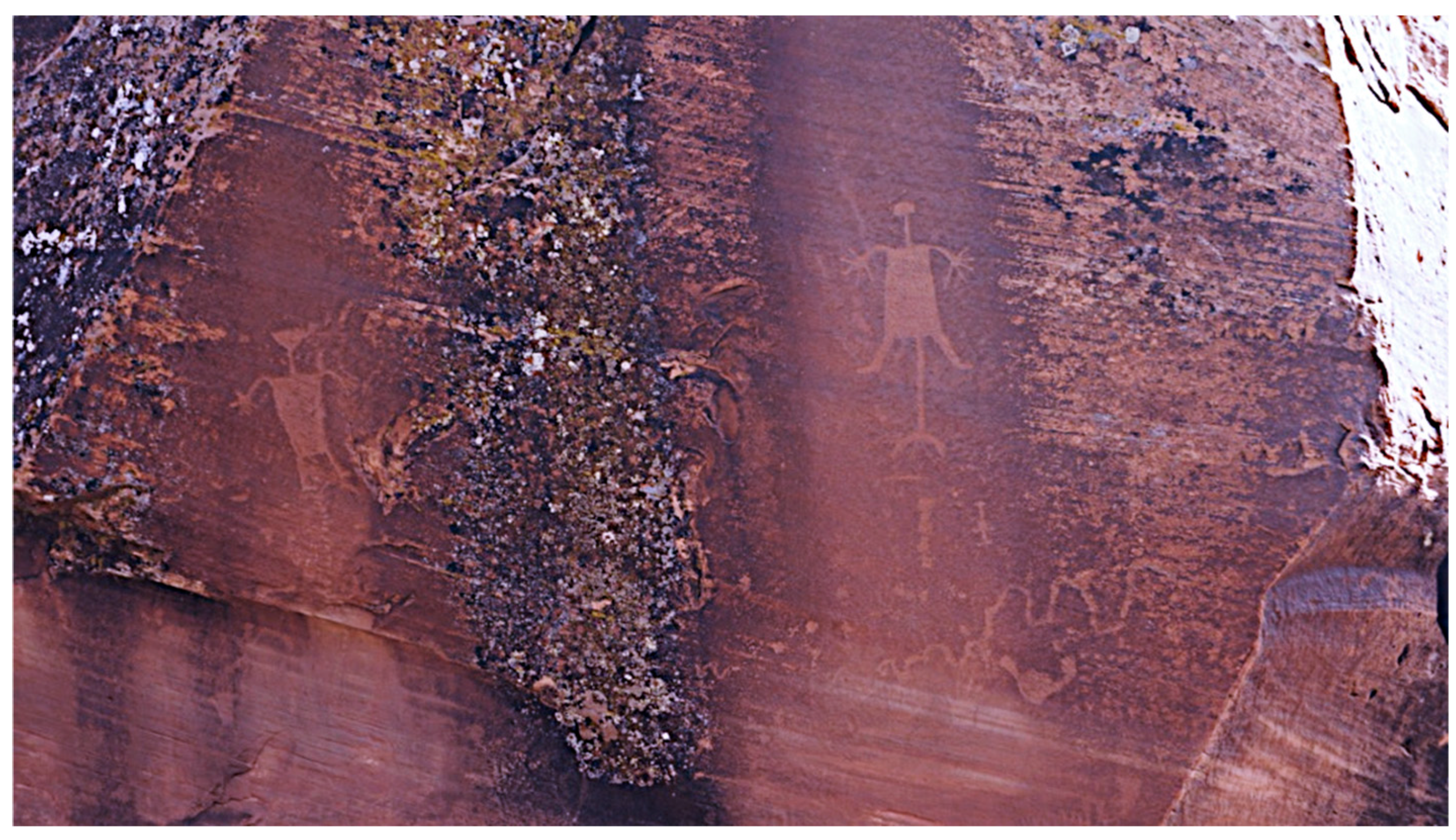

9.3. Geosite Three: Cliff Complex

Doctoring paraphrenia and a place for doctors to prepare themselves is normally nearby, private, and away from any residential areas. The Indian Creek Doctor Rock has a series of multi stories towers located more than 300 feet above the valley bottom on a nearby narrow and steep cliff edge. The tribal representatives argued that is a ceremonial area. Medical paraphrenia could have been stored here and inside and open spaces provided areas for doctors to prepare themselves for doctoring (

Figure 36 and

Figure 37). After doctoring the participants require purification and there is a spring on the ledge near the structures.

Next to the structures on the cliff face is a high smooth sandstone face on which there are number of paintings (

Figure 38) Some figures are painted with red pigment, others are made from white pigment, and still others are pecked into the face of the rock.

Pueblo representatives from Zuni during a site visit said that the nearby Doctor Rock is connected with the cliff face structures, paintings on the high wall, and spring on the narrow ledge of the cliff face. It is argued based on proximity and tribal interpretations that the Dr. Rock is ceremonially connected with the cliff face complex including the spring. The two areas are 1,400 feet apart and the Cliff Complex is 300 feet directly up the face from the valley bottom. The Celestial Light Marker is six miles downstream from these ceremonial features.

10. Heritage of Indian Creek

It has been argued based on Native American interviews (see methods section) that Indian Creek from its head waters in the Abajo Mountains to its mouth where it joins the Colorado River has been a spiritually special geoscape since Time Immemorial. A few geosites along its length have been discussed in this analysis, which of course is centered on the Celestial Light Marker, Dance Grounds, and western twin peaks. The Indian Creek hydrological system is enormously complex in term of topography, ecology, and Native American heritage places, especially geosites. In addition, some ceremonial support places apparently not tied to geology have been left out of the analysis to protect them from intrusion and potential damage. The road to the Canyonlands National Park has been constructed along Indian Creek and so it annually directs hundreds of thousands of tourists, including technical rock climbers and recreational campers, to the area. Our data argues that this culturally special hydrological system warrants special protection from damage or insult to preserve Native American heritage that is shared by dozens of tribes and pueblos.

An example of the range of interpretations provided by pueblo representatives is that from Acoma. At the doctoring rock site, Acoma Pueblo representatives expressed that they felt deep connections with the Indian Creek area, interpreting it as a part of their ancestors’ sacred migration journey to their current home. While detailed symbol-specific interpretations were not provided due to cultural sensitivity issues, Acoma Pueblo representatives shared that some of the symbols on the Dr. Rock boulder narrate the Acoma migration histories or represent landmarks of the migration journeys of the early Acoma people. They also emphasized that such places like the boulder and other similar spots within the Indian Creek area, such as, Newspaper Rock, are alive, being able to remember stories and names that were and are told to them. The Acoma people thus still visit these places of rock in their dreams and prayers to this day and speak to them as is appropriate for living beings..

11. Discussion

The concern for knowing about space and time has been cultural central for all the Native American tribes and pueblos while they were living in the Mesa Verde Word and subsequently for their ancestors wherever they live today. This is a cultural fact born out by every annual ceremony of each Native group today. Of the hundreds of interviews conducted during this research no tribe disputed the notion that they look to the solar system to understand time and subsequently structure their scheduling of what behaviors which ceremonies should occur.

Participating tribal representatives generally agreed that during the peak of the Mesa Verde World people were subject to the advice of a powerful religious elite. They supported this elite by moving their homes near to Big Houses and participating in ceremonies there to balance the world which was becoming less predictable. The droughts were longer. The rains fell at the wrong times. The weather changed but generally became colder. During the 1200s AD these communities were entering what is now called the Little Ice Age and productive agricultural surplus that supported a stable way of life was coming an end. During 70 years in the 1200s at Hovenweep the religious elite worked together to achieve control over the balance of the universe, but by 1270 a long drought would cause their citizens to lose faith and stop supporting the religious elite.

Interesting these Native people today continue to believe in the epistemological principals that guided their balancing behaviors for hundreds of years during the Mesa Verde World, but now performances of balancing ceremonies are primarily accomplished in local kivas by special knowledge groups of experts. The power of the religious elite ended, and they never reemerged, but ancient Native understandings of the universe persisted.

Without a central coordinated religious body of specialists, but with a common epistemological theory that they could effect massive worldwide change, up to 32 Native tribes coordinated two cultural movements to balance the world (Stoffle et al. 2000). These were the 1870 and 1890 Ghost Dance movements. It is not clear whether or not the Indian Creek Celestial Light Marker contributed to ceremonies associated with this movement but there is evidence of a Ghost Dance ceremony occurring in Indian Creek near the Celestial Light Marker.

11.1. The World According to Pimm and Tribal Elders

For more than a year Stoffle served on a National Research Council appointed committee on Marine Protected Areas (NRC 2001) and it afforded an opportunity to work with Stewart Pimm. During our frequent meetings Pimm was observed rapidly reviewing hundreds of ecology research proposals for National Science Foundation and manuscripts for science journals. His speed was impressive, and he explained that scholarly research in ecology was regularly limited by myopia, where (1) the scholar selects too few species or natural variables for study when the explanation of the phonomime involved more key missing ones and (2) the scholar selects an overly narrow temporal frame when what is being studied happens over longer time frames.

From his book the World According to Pimm (Pimm 2001), earlier work (Pimm 1991) and our continued discussions at the NRC meetings, it became clear that similar limits occur in Native American Heritage research. Research by Tilley (1997, 2004) regarding the Phenomenology of Landscapes: Places, Paths, and Monuments also was instructive in our development of landscape interviews. Both Pimm’s biology and Tilley archaeology methods were missing ways to better listen to tribal elders participating in the studies. With the advice of tribal elders, a Native American cultural landscape data collection form was produced. Responding to their recommendations our landscape interviews always used large paper maps to mark the broader ideas of what we now call Geoscapes. The cultural value of places was not lost in this process, instead we began writing about what Native elders define as the functional interrelations between living places in the formation and operation of geoscapes.

Although our research team has authored articles and more than a dozen ethnography reports, a problem of credibility persisted among Federal land managers. The western trained scientists have had personal and scholarly difficulties accepting as either true or real what Native elders have said about the land, animals, plants, and living stone portals as elements of a living Earth. We began to frame this as an Epistemological Divide. Such barriers in environmental communication (Sjolander-Lindqvist, Murin, and Dove 2022) are not easily understood and almost never do the two cultures agree that the opposing view is fully correct. At best, however the two views can be placed side by side and given equal credit in environmental interpretation and management. Some U.S. federal agencies call this Cultural Multivocality.

A major difficulty in environmental communication is that western trained scholars and managers are taught to believe what they can see and systematically document. Native elders work with knowledge that is ancient, and it has been tested over great periods and with many variables considered. This is the foundation of Native Science (Johnson and Arlidge 2024; Stoffle, Arnold, and Van Vlack 2024). Western trained scholars term Native Science a matter of Faith and some ancient knowledge does become imbedded in religious practices. Still Native Science cannot persist unless it provides accurate explanations of Nature and does so for great periods of time. No one uses medicine that does not work, so a Doctor Rock that does not heal become empty and unused.

Author Contributions

Dr. Stoffle was senior Principal Investigator on the Arches NP, Canyonlands NP and Hovenweep NM studies. Van Vlack is the Principal Investigator for the MFO project and served as the Principal Investigator for the Moab Ethnographic Study. Miss Lim served as key research personnel on the projects. All three helped write, edit, and fact check during the production of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

Funding for the referenced research projects were provided by the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management.

References

- (Angelback et al 2024) Angelbeck, Bill, Chris Springer, Johnny Jones/Yaqalatqa, Glyn Williams-Jones , and Michael C. Wilson. 2024.Líĺwat Climbers Could See the Ocean from the Peak of Qẃelqẃelústen: Evaluating Oral Traditions with Viewshed Analyses from the Mount Meager Volcanic Complex Prior to Its 2360 BP Eruption. American Antiquity (2024), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- (Bennett et al. 2021) Bennett, M, Bustos, D, Pigati, J, Springer, K., Urban, T, et al., 2021. Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. Science 373: 1528-1531.

- (Brocx and Semeniuk 2017) Brocx, M. and Vic Semeniuk. 2017. “Towards a Convention on Geological Heritage (CGH) for the Protection of Geological Heritage.” Geophysical Research Abstracts. Vol 19.

- (Brocx and Semeniuk 2022) Brocx, M. and Vic Semeniuk. 2022. “Geoparks, Geotrails, and Geotourism—Linking Geology, Geoheritage, and Geoeducation.” Land: An Open Access Journal by MDPI.

- (Canyons of the Ancients 2024) Canyons of the Ancients. 2024. Canyons of the Ancients National Monument. Cortez Colorado: Bureau of Land Management.https://www.blm.gov/programs/national-conservation-lands/colorado/canyons-of-the-ancients.

- (Grayson 1993) Grayson, D. 1993. The Desert’s Past: A Natural Prehistory of the Great Basin. Washington D.C, USA: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- (IUCN 2024) International Union for Conservation of Nature. World Commission on Protected IUCN 2024. International Union for Conservation of Nature. World Commission on Protected Areas 2021-2025 https://iucn.org/our-union/commissions/iucn-world-commission-protected-areas-2021-2025.

- (Johnson and Arlidge 2024) Johnson, E. A. and Aldridge, S. M. (eds). 2024. Natural Science and Indigenous Knowledge: the Americas Experience. England: Cambridge University Pres. [CrossRef]

- (Kohler et al. 2008) Kohler, T. A., M. D. Varien, A. M. Wright, and K. A. Kuckelman. 2008. “Mesa Verde Migrations: New Archaeological Research and Computer Simulation Suggest Why Ancestral Puebloans Deserted the Northern Southwest United States.” American Scientist 96(2):146-153.

- (Loubser and Ashcraft 2020) Loubser, J. and S. Ashcraft. 2020. Gates Between Worlds: Ethnographically Informed Management and Conservation of Boulders in the Blue Ridge Mountains. In Cognitive Archaeology: Mind, Ethnography, and the Past in South African and Beyond. Pp.247-. 269. D. Whitley, J. Loubser, and Whitelaw (eds.) London: Routledge, Taylor Francis Group.

- (Muzambiq et al. 2024) Muzambiq, S., R. Sibarani, Z. P. Nasution, and G. Gustanto. 2024. “Geoheritage and Cultural Heritage Overview of the Toba Caldera Geosite, North Sumatra, Indonesia.” Smart Tourism Vol 5 (1). [CrossRef]

- (NPS 2024a) National Park Service. “Fajada Butte: Chaco Culture National Historical Park.” https://www.nps.gov/places/fajada-butte-overlook.ht Accessed December 16, 2024.

- (NPS 2024b) National Park Service and Jacob W. Frank. “North Window and Milky Way.” https://www.nps.gov/media/photo/gallery-item.htm?id=264B17EA-155D-451F-67A77ACA100D7BD2&gid=275B0E39-155D-451F-6752DA81D6E6018D Accessed December 16, 2024.

- (Noble 2006) Noble, D. G. 2006. The Mesa Verde World: Explorations in Ancestral Pueblo Archaeology. Santa Fe, N.M.: School of American Research Press.

- (NRC 2001) NRC. 2001. Marine Protected Area: Tools for Sustaining Ocean Ecosystems. National Research Council Committee. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- (Pigati et al. 2023) Pigati, J. S., Springer, K. B., Honke, J. S., Wahl, D., Champagne, M. R., et al. (2023) Independent age estimates resolve the controversy of ancient human footprints at White Sands. Science 382: 73-75.

- (Pimm 1991) Pimm, S. 1991. The Balance of Nature?: Ecological Issues in the Conservation of Species and Communities. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- (Pimm 2001) Pimm, S. 2001. The World According to Pimm.: A Scientist Audits the Earth. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- (Rowe et al. 2022) Rowe T, Stafford, T. W., Fisher, D, Enghild, J, Quigg. J.M., et al. 2022. Human Occupation of the North American Colorado Plateau 37,000 Years Ago. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 10.

- (Ruuska 2025) Ruuska, A. K. 2025. When the Earth was New Memory, Materiality, and the Numic Ritual Life Cycle. Ogdon, UT: University of Utah Press.

- (Sofaer, Zinser and Sinclair 1979) Sofaer, A., V. Zinser, and R. M. Sinclair. 1979. “A Unique Solar Making Construct.” Science 206 (4416): 283-291.

- (Sofaer and Sinclair 1982) Sofaer, A. and R. M. Sinclair. 1982. Astronomical Marking Sites on Fajada Butte. Chaco Canyon Center, New Mexico. NPS, Department of the Interior.

- (Stoffle, Arnold, and Van Vlack 2024) Stoffle, R., Arnold, R. and Van Vlack, K. 2024. Native American Science in a Living Universe: A Paiute Perspective. In Natural Science and Indigenous Knowledge: the Americas Experience. Editors E. A. Johnson and S. M. Aldridge. England: Cambridge University Press.

- (Stoffle et al. 1994) Stoffle, R., M. J. Evans, M. Nieves Zedeno, B. W. Stoffle, and C. J. Kesel. 1994. American Indians and Fajada Butte: Ethnographic Overview and Assessment for Fajada Butte and Traditional (Ethnobotanical) Use Study for Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona.

- (Stoffle et al. 2016) Stoffle, R., E. Pickering, K. Brooks, C. Sittler, K. Van Vlack. 2016. Ethnographic Overview and Assessment for Arches National Park. Department of Anthropology, The University of Anthropology. Tucson, AZ: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology.

- (Stoffle et al. 2017) Stoffle R, E. Pickering, C. Sittler, H. Lim, K/Brooks, K/Van Vlack, C. Forer, and M. Albertie. 2017. Ethnographic Overview and Assessment for Canyonlands National Park. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona.

- (Stoffle et al. 2000) Stoffle, R., L. Loendorf, D. Austin, D. Halmo, and A. Bulletts. 2000. Ghost Dancing the Grand Canyon: Southern Paiute Rock Art, Ceremony, and Cultural Landscapes. Current Anthropology 41(1): 11- 38.

- http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/CA/journal/contents/v41n1.html.

- (Stoffle et al. 2019) Stoffle R. W., C. Sittler, M. Albertie, H. Lim, C. M. Johnson, C. Kays, G. Penry, D. Velasco, and N. Pleshet. 2019. Hovenweep National Monument Ethnographic Overview and Assessment. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona.

- (Stoffle et al. 2021) Stoffle, Richard W., Noah Pleshet, Kathleen Van Vlack, Christopher Sittler, Heather H. Lim, Mariah Albertie, Cameron R. Kays, Christopher M. Johnson, Grace K. Penry, Daniel E. Velasco, and Irene J. Ortiz. 2021. Natural Bridges National Monument Ethnographic Overview and Assessment University of Arizona.

- (Sjolander-Lindqvist, Murin, and Dove 2021) Sjolander-Lindqvist, A., Murin, I., and Dove, M. 2021. Anthropological Perspectives on Environmental Communication. Palgrave Studies in Anthropology of Sustainability. Switzerland: Springer Nature Macmillan. ISBN 9783030780401, 3030780406.

- 32. (Tilley 1997) Tilley, Christopher 1997. A Phenomenology of Landscape Places, Paths and Monuments. T London, England: Berg Publishers.

- (Tilley 2004) Tilley, Christopher 2004. The Materiality of Stone: Explorations in Landscape. London, England: Routledge.https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003087083.

- (U.S. Congress 2025) U.S. Congress. 2025. Antiquities Act of 1906. S. Rept. 106-250 https://www.congress.gov/congressional-report/106th-congress/senate-report/250.

- (UCAR 2024) UCAR. 2024. University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. “Sun Dagger.” https://www2.hao.ucar.edu/education/prehistoric-southwest/sun-dagger.

- (Van Vlack et al. 2023) Van Vlack, K., J. Yaquinto, H. Lim, S. Gantt, and Finch. 2023. Moab Ethnographic Study: Southern Paiute and Ute Perspectives. Cortez, CO: Living Heritage Research Council.

- (Van Vlack et al. 2025) Van Vlack, K., H. Lim, J. Yaquinto, J. Gazing Wolf. 2025. Monticello BLM Ethnographic Partnership: Ethnographic Overview and Assessment of the Cedar Mesa and Bears Ears Region Preliminary Draft. Prepared for the Bureau of Land Management, Monticello Field Office Heritage Lands Collective, Cortez, CO.

- (Van Vlack et al. 2025) Van Vlack, K., J. Yaquinto, S. Kelley. 2025. Tribal Ethnohistories of the Greater Cedar Mesa and Bears Ears Region. Prepared for the Bureau of Land Management, Monticello Field Office Heritage Lands Collective, Cortez, CO.

- (Varien 1999) Varien, M. D. 1999. Sedentism and Mobility in a Social Landscape: Mesa Verde and Beyond. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

- (Villanueva et al. 2024) Villanueva, G. R, M. Sepúlveda, J. Cárcamo-Vega, A. Cherkinsky, M. Eugenia de Porras, and R. Barberena. 2024. Earliest directly dated rock art from Patagonia reveals socioecological resilience to mid- Holocene climate. Science Advances, Research Article: 10: 1-15.

- (Whitley 1998) Whitley, D.S. 1998. Finding Rain in the Desert: Landscape, Gender, and Far Western North American Rock- Art. In P.S.C. Tacon and C. Chippindale (eds), The Archaeology of Rock- Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 11– 29.

- (Whitley 2023) Whitley, D. 2013. Rock Art Dating and the Peopling of the Americas: A Revies. Journal of Archaeology Vol 2013, Article ID 713159, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- (Whitley, Loubser, Whitelaw 2020) Whitley, J., Loubser, and G. Whitelaw. 2020. The Benefits of an Ethnographically Informed Cognitive Archaeology. In Cognitive Archaeology: Mind, Ethnography, and the Past in South African and Beyond. Pp.1-19. Whitley, Loubser, and Whitelaw (eds.) London: Routledge, Taylor Francis Group.

- (Wilshusen and Glowacki. 2017Wilshusen, R. H., and D. M. Glowacki. 2017. An Archaeological History of the Mesa Verde Region. In The Oxford Handbook of Southwest Archaeology, Edited by Barbara Mills and Severin Fowles, 307-322. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Figure 1.

Indian Creek Study Area In the Higley Politicized Bears Ears National Monument, Outlined in Red.

Figure 1.

Indian Creek Study Area In the Higley Politicized Bears Ears National Monument, Outlined in Red.

Figure 2.

Western Frame of the Celestial Light Marker.

Figure 2.

Western Frame of the Celestial Light Marker.

Figure 3.

Engineered Stone Marker.

Figure 3.

Engineered Stone Marker.

Figure 4.

Arch and Hoodoos.

Figure 4.

Arch and Hoodoos.

Figure 5.

Night Sky Through and Around Arch (Source NPS Photo).

Figure 5.

Night Sky Through and Around Arch (Source NPS Photo).

Figure 6.

Square Tower on a Massive Vertical Free-Standing Stone at Head of Canyon.

Figure 6.

Square Tower on a Massive Vertical Free-Standing Stone at Head of Canyon.

Figure 7.

Stone Structures with Celestial Light Marking Holes in Walls.

Figure 7.

Stone Structures with Celestial Light Marking Holes in Walls.

Figure 8.

Stone Structures with walls that mark time with shadows.

Figure 8.

Stone Structures with walls that mark time with shadows.

Figure 9.

Structures with Multiple Holes.

Figure 9.

Structures with Multiple Holes.

Figure 11.

Sun Dagger (Source: UCAR 2024).

Figure 11.

Sun Dagger (Source: UCAR 2024).

Figure 12.

Study Area, The American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River (AICC) and portion of the Mesa Verde World.

Figure 12.

Study Area, The American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River (AICC) and portion of the Mesa Verde World.

Figure 13.

Mesa Verde, the National Park, and Region.

Figure 13.

Mesa Verde, the National Park, and Region.

Figure 14.

Canyons atop Mesa Verde (Photo Stoffle 2018).

Figure 14.

Canyons atop Mesa Verde (Photo Stoffle 2018).

Figure 15.

Cliff Palace on Mesa Verde (Photo Stoffle 2018).

Figure 15.

Cliff Palace on Mesa Verde (Photo Stoffle 2018).

Figure 16.

Archaeologists’ Interpretation Map of Mesa Verde World.

Figure 16.

Archaeologists’ Interpretation Map of Mesa Verde World.

Figure 17.

Sandal Footprint at Moab Panel, Footprints at Newspaper Rock, and Spiral at Solar Calendar along Indian Creek.

Figure 17.

Sandal Footprint at Moab Panel, Footprints at Newspaper Rock, and Spiral at Solar Calendar along Indian Creek.

Figure 18.

Phragmites Pecking and Phragmites Plant.

Figure 18.

Phragmites Pecking and Phragmites Plant.

Figure 19.

The Ute Panel.

Figure 19.

The Ute Panel.

Figure 20.

The Celestial Light Marker (red background tint) as it spans Indian Creek.

Figure 20.

The Celestial Light Marker (red background tint) as it spans Indian Creek.

Figure 21.

Mesa above Celestial Light Marker.

Figure 21.

Mesa above Celestial Light Marker.

Figure 22.

Fallen and Broken Mesa Caprock used to engineer the Celestial Light Marker.

Figure 22.

Fallen and Broken Mesa Caprock used to engineer the Celestial Light Marker.

Figure 23.

Engineered Upright Slab That Focusses the Light.

Figure 23.

Engineered Upright Slab That Focusses the Light.

Figure 24.

Engineered Pointer Support Rock in Carved Notch.

Figure 24.

Engineered Pointer Support Rock in Carved Notch.

Figure 25.

Flat Sandstone Face Orientated to Light From the West.

Figure 25.

Flat Sandstone Face Orientated to Light From the West.

Figure 26.

Close Up Pecking on Flat Sandstone Face Receiving Light from the West, Note the Clean Surface at the North Edge.

Figure 26.

Close Up Pecking on Flat Sandstone Face Receiving Light from the West, Note the Clean Surface at the North Edge.

Figure 27.

North Facing Flat Sandstone Face With Multiple Lichen.

Figure 27.

North Facing Flat Sandstone Face With Multiple Lichen.

Figure 28.

the Dance Grounds to the north of the fallen Mesa Top Remnant.

Figure 28.

the Dance Grounds to the north of the fallen Mesa Top Remnant.

Figure 29.

Dance Ground Covered With “Offerings” of Chert, Pottery Sherds, Yellow Paint Pigment, Chipped Stones, and Apparently Seashells Shell fragments in The Surface of the Dance ground.

Figure 29.

Dance Ground Covered With “Offerings” of Chert, Pottery Sherds, Yellow Paint Pigment, Chipped Stones, and Apparently Seashells Shell fragments in The Surface of the Dance ground.

Figure 30.

Yellow Minerals Often Used in Paint Found on The Dance Grounds.

Figure 30.

Yellow Minerals Often Used in Paint Found on The Dance Grounds.

Figure 31.

Peaks to West of the Marker.

Figure 31.

Peaks to West of the Marker.

Figure 32.

Tribal elder interpretating Newspaper Rock, Indian Creek Utah.

Figure 32.

Tribal elder interpretating Newspaper Rock, Indian Creek Utah.

Figure 33.

Acoma Representatives and Ethnographers at Doctor Rock.

Figure 33.

Acoma Representatives and Ethnographers at Doctor Rock.

Figure 34.

Close up of Two Peckings on Dr Rock.

Figure 34.

Close up of Two Peckings on Dr Rock.

Figure 35.

Cut Steps Extending to Top of the Doctor Rock.

Figure 35.

Cut Steps Extending to Top of the Doctor Rock.

Figure 36.

Cliff Structure.

Figure 36.

Cliff Structure.

Figure 37.

Cliff Structure and Spring.

Figure 37.

Cliff Structure and Spring.

Figure 38.

Rock Peckings and Red Painted Figures Next to Cliff Structure.

Figure 38.

Rock Peckings and Red Painted Figures Next to Cliff Structure.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).