Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Relevance of the Topic and Research Motivation

1.2. Review, Critical Analysis and Systematisation of Current Literature Sources

1.3. Novelty and Main Contributions of the Paper

1.4. Organisation and Structure of the Paper

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Description of Research Methods and Means

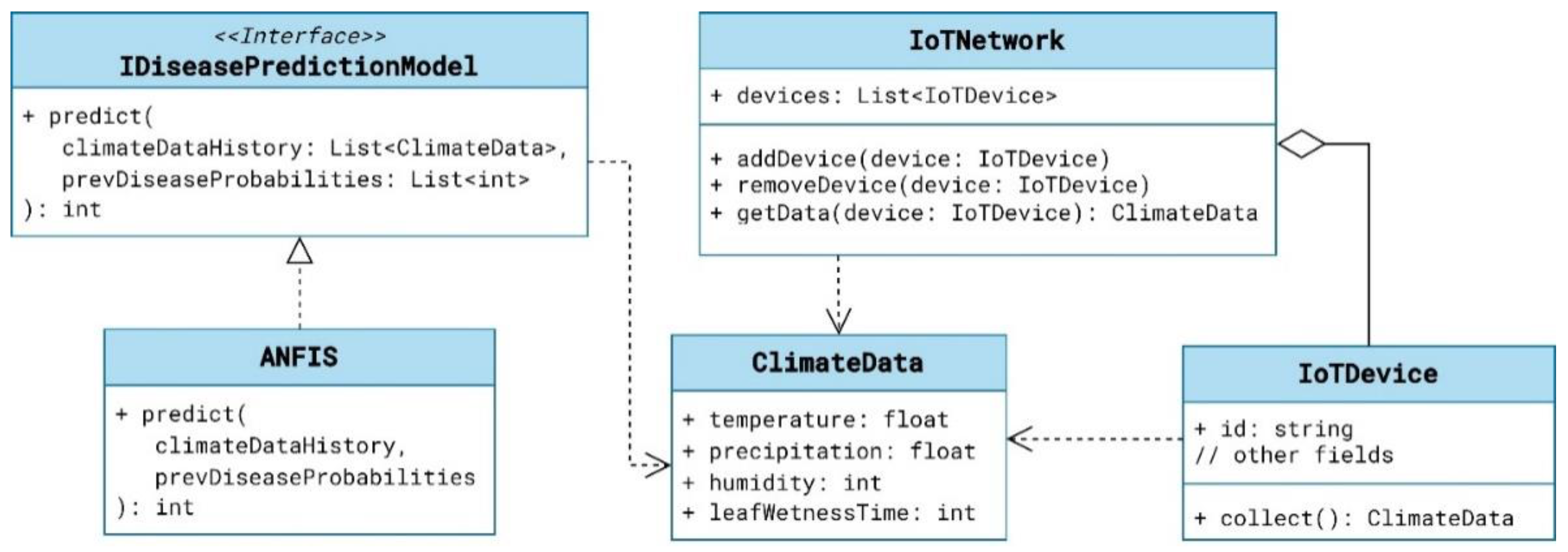

2.2. Generalised Structural Description of Computer-Oriented Model

2.3. Model Limitations

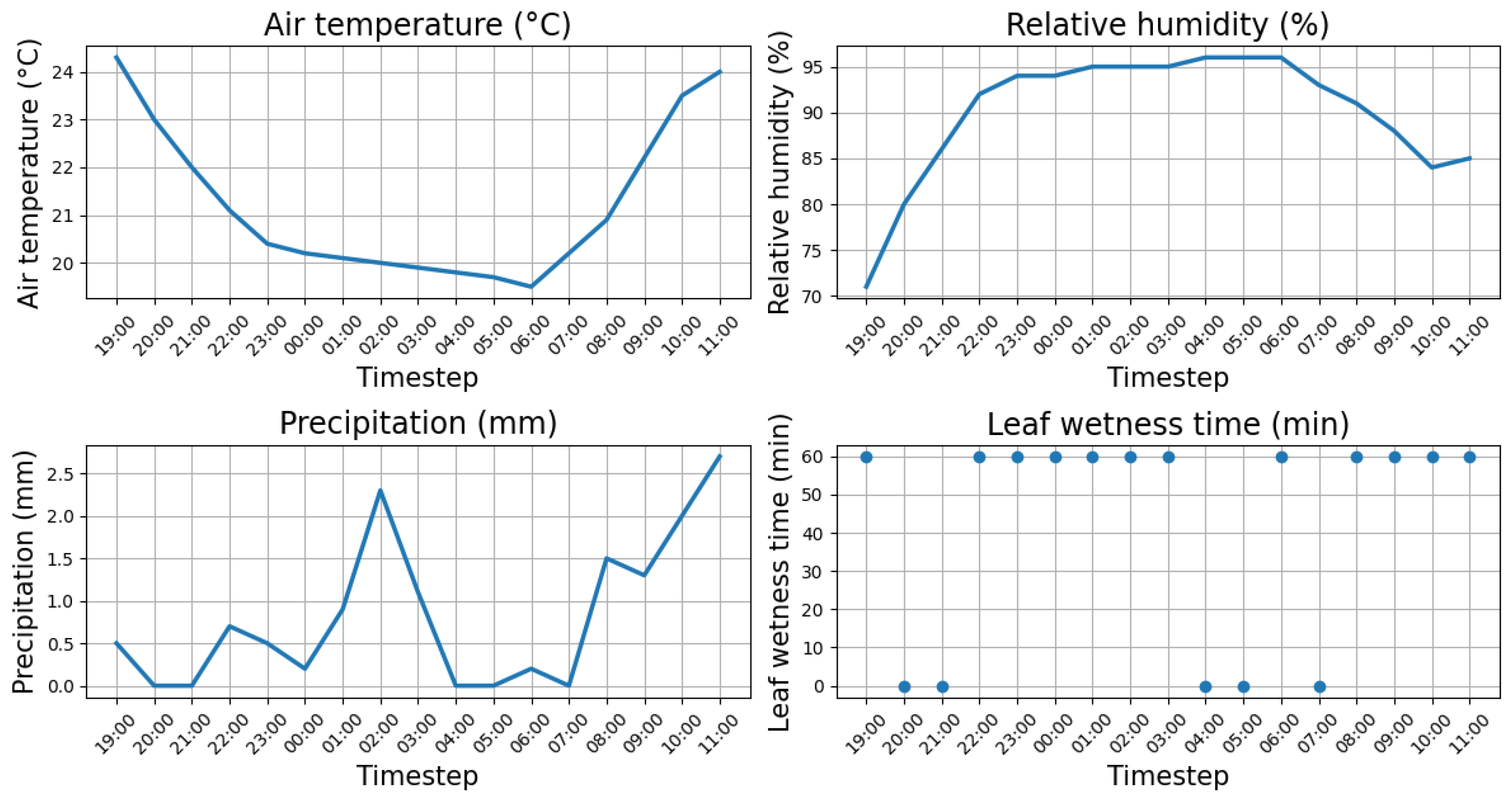

- the dataset (spanning from September 2022 to September 2023) containing climatic parameters was gathered from the Metos by Pessl Instruments weather station, utilising the FieldClimate IoT platform. Access to this platform was granted by Metos Ukraine LLC;

- the agroclimatic zone for data collection was the northern steppe of Ukraine, characterised as arid and warm (with a hydrothermal coefficient ranging from 0.7 to 1.0). The typical annual temperature sum ranges from 2900°С to 3300°С;

- the agricultural crop under study was corn;

- the diagnosed disease of interest was Fusarium Head Blight;

- informative soil and climatic parameters included air temperature (°С), relative humidity (%), precipitation (mm) and leaf wetness time (min).

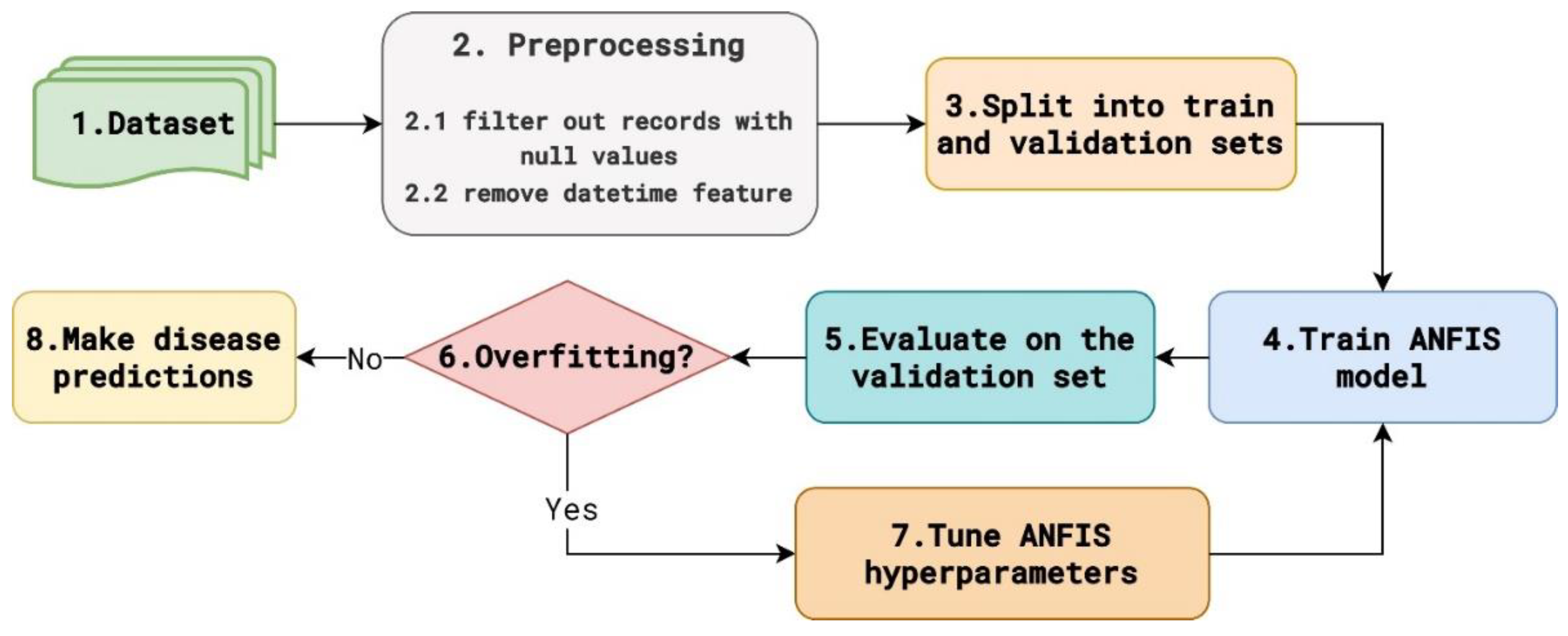

3. Results

3.1. Results of Development and Modelling of Functional Components of the IoT System

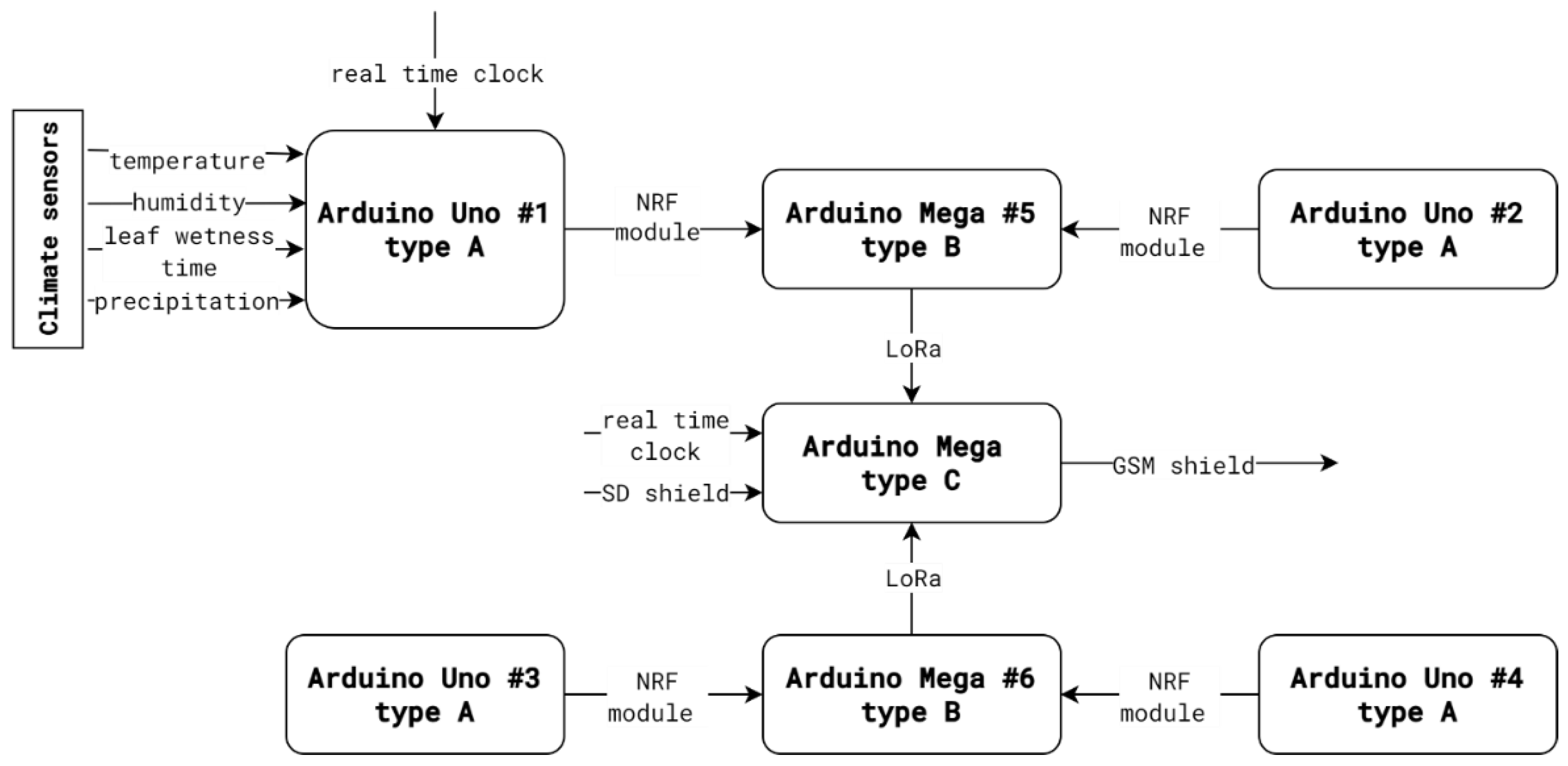

- The ANFIS model acquired in [58] is converted into software code tailored for the Arduino Mega microcontroller platform utilizing a specialized open-source online tool (refer to Appendix A). Subsequently, adjustments were made to the arguments of the software components' functions to ensure alignment with the involved microcontroller pin numbers and the ranges of variation in physicochemical soil and climatic parameters.

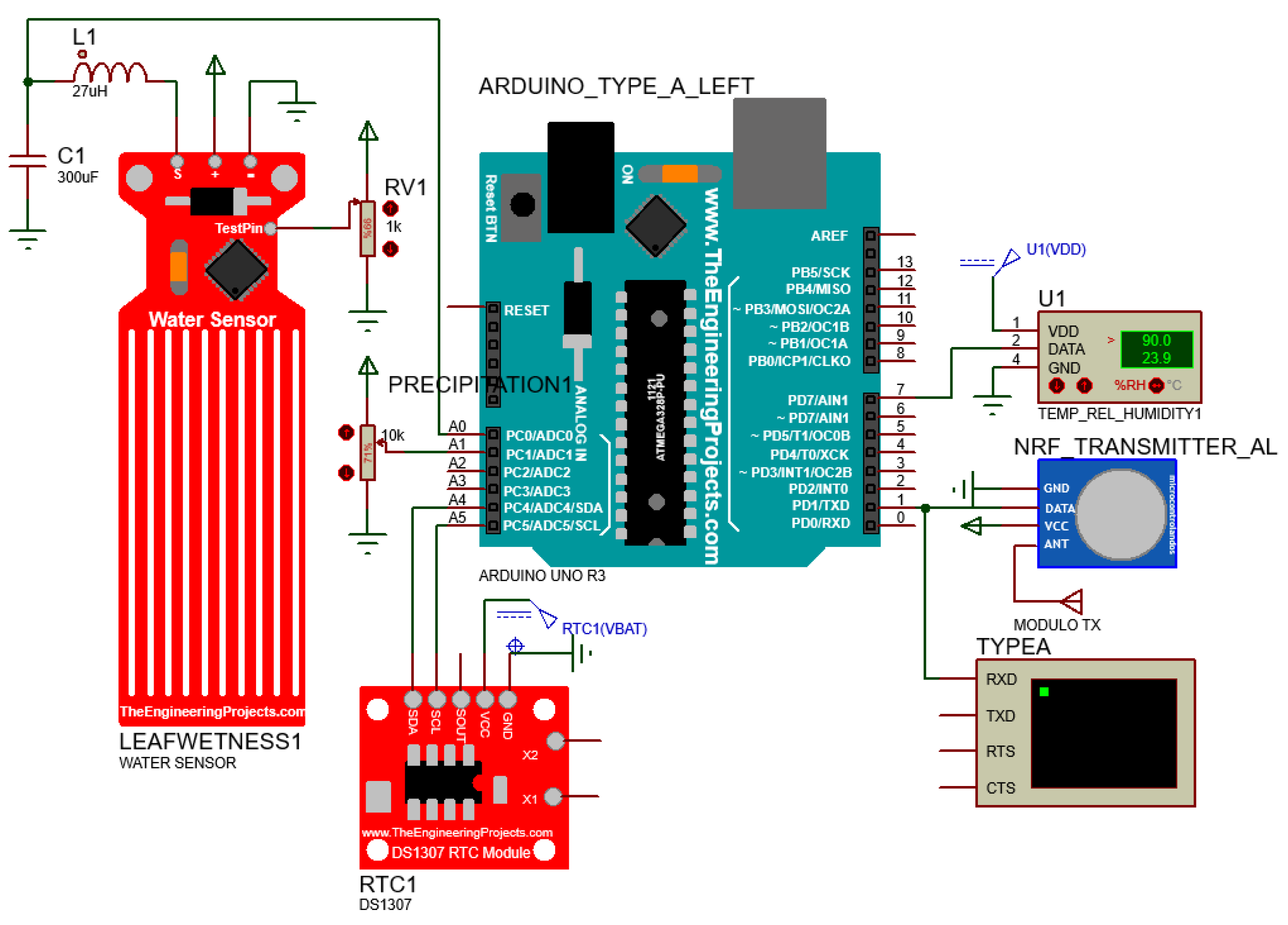

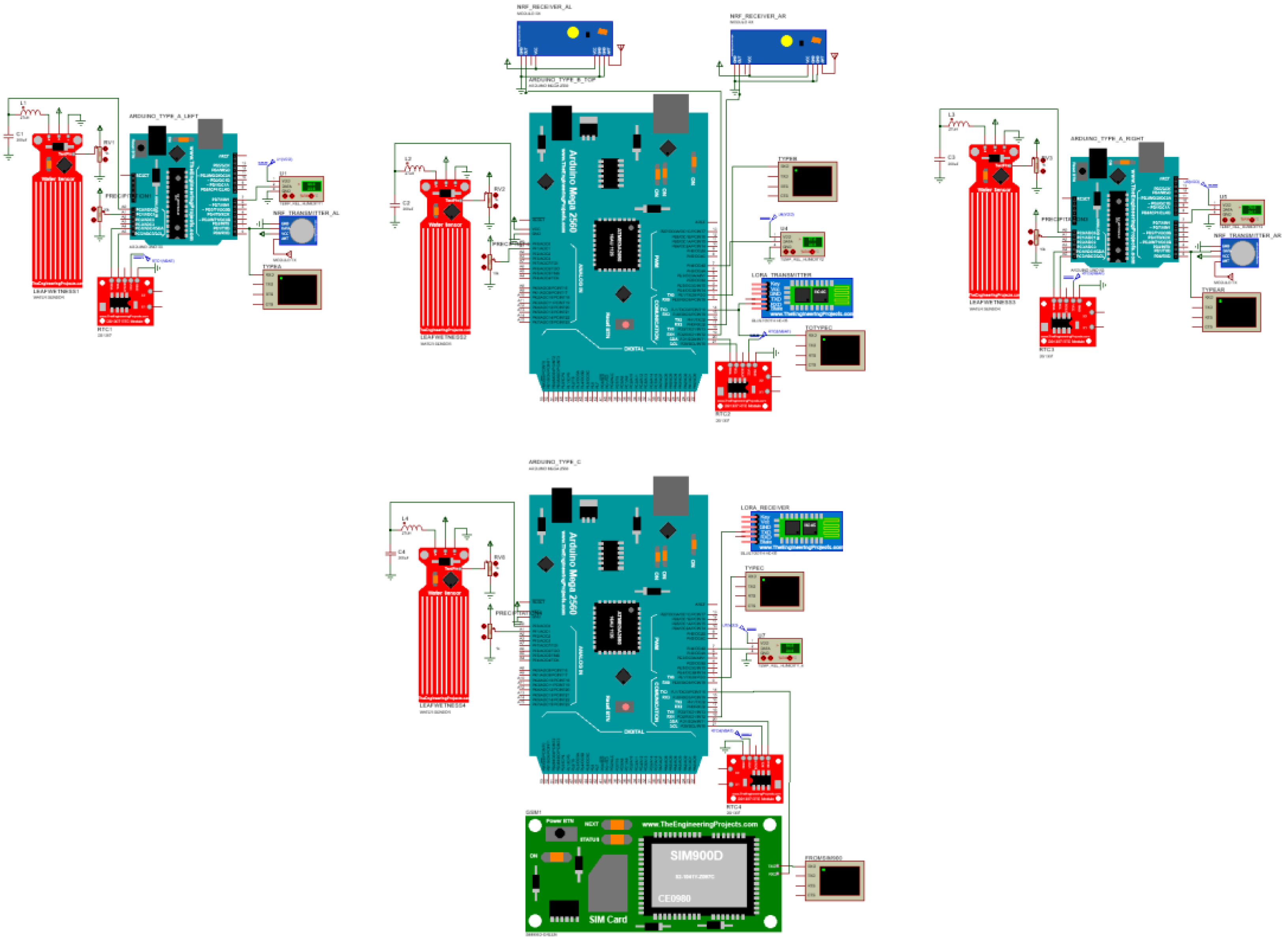

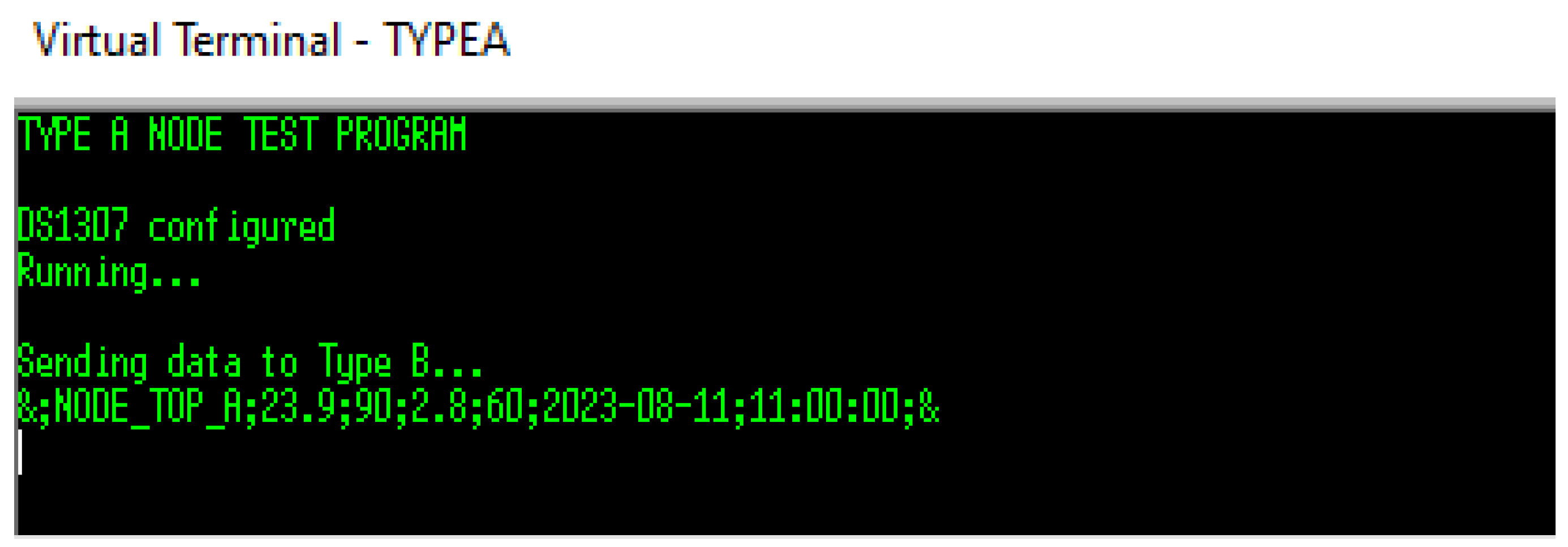

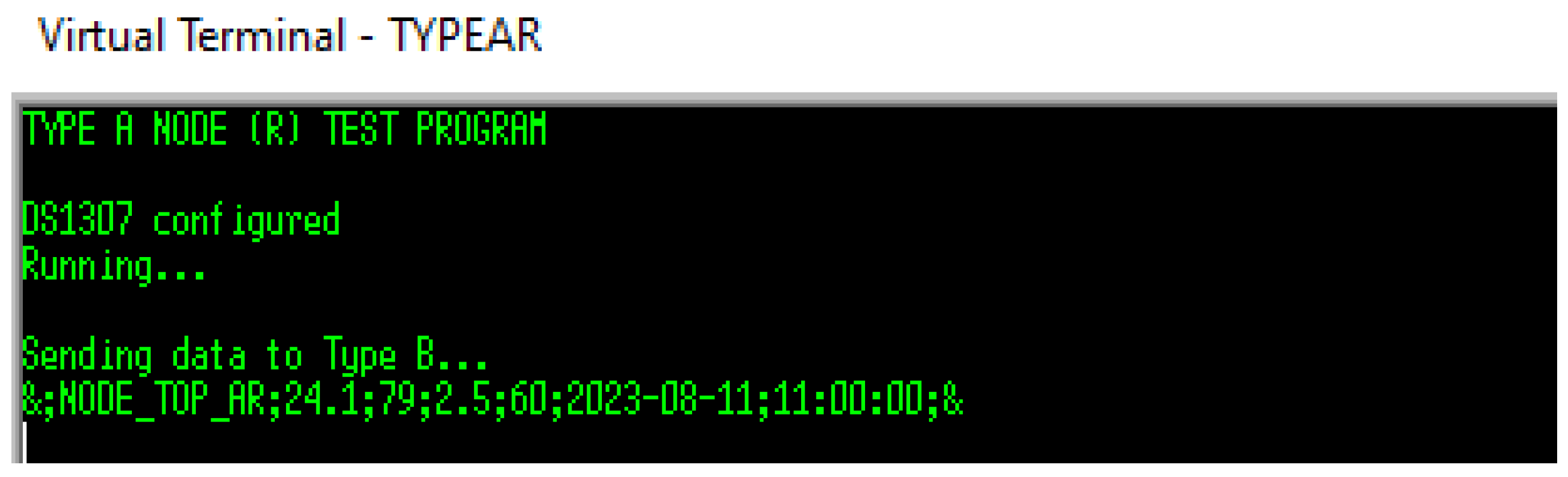

- Development of a simulation model of a Type A network node utilizing Arduino Uno Rev3 within the Proteus environment mentioned in Appendix A, depicted in Figure 6. This simulation model integrates software developed in the Arduino IDE environment (see Appendix A), which implements the acquisition of soil and climate sensors data, preliminary statistical analysis (time and space averaging), and the transmission of measurement data to the Type B network node using the NRF module.

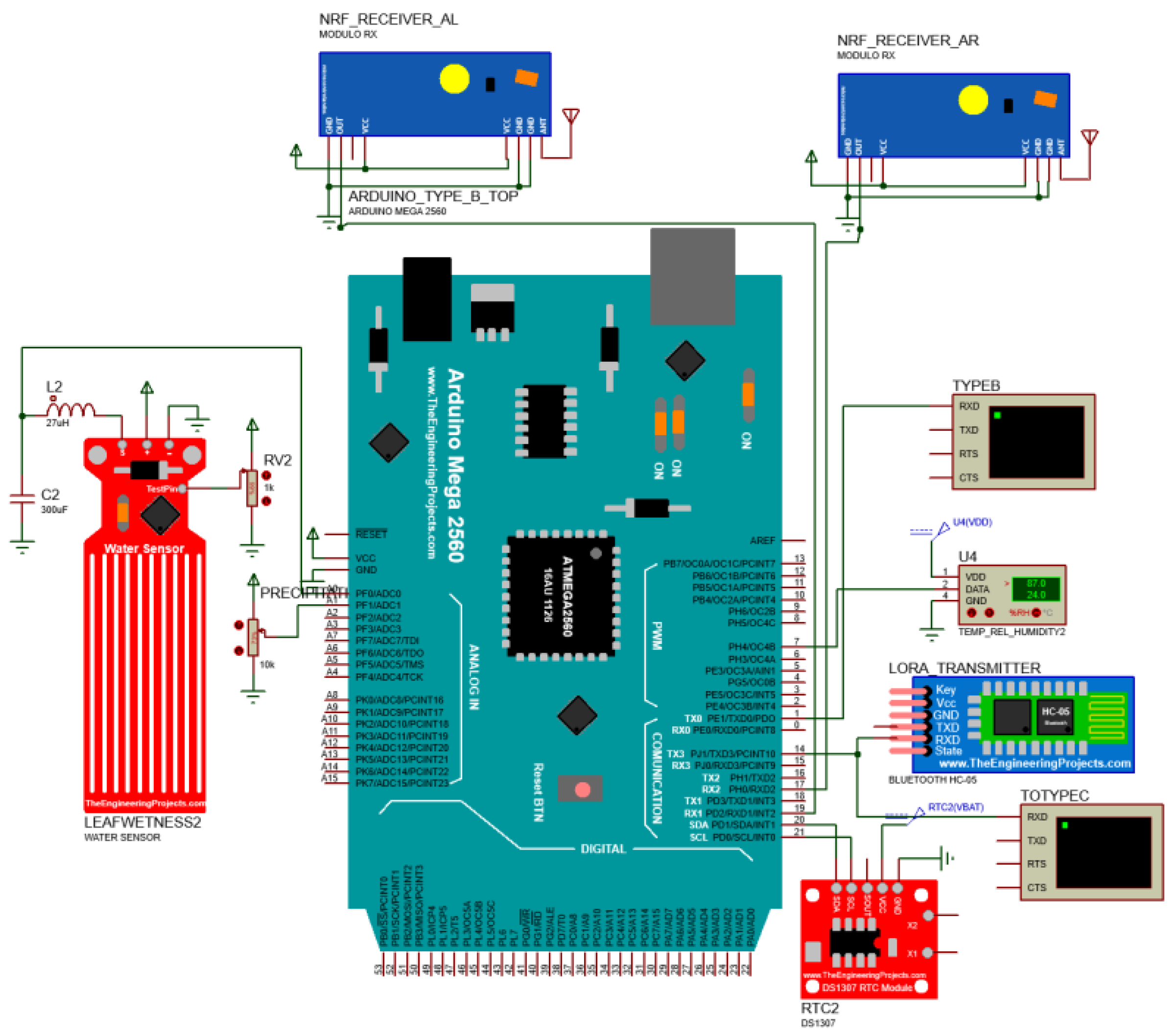

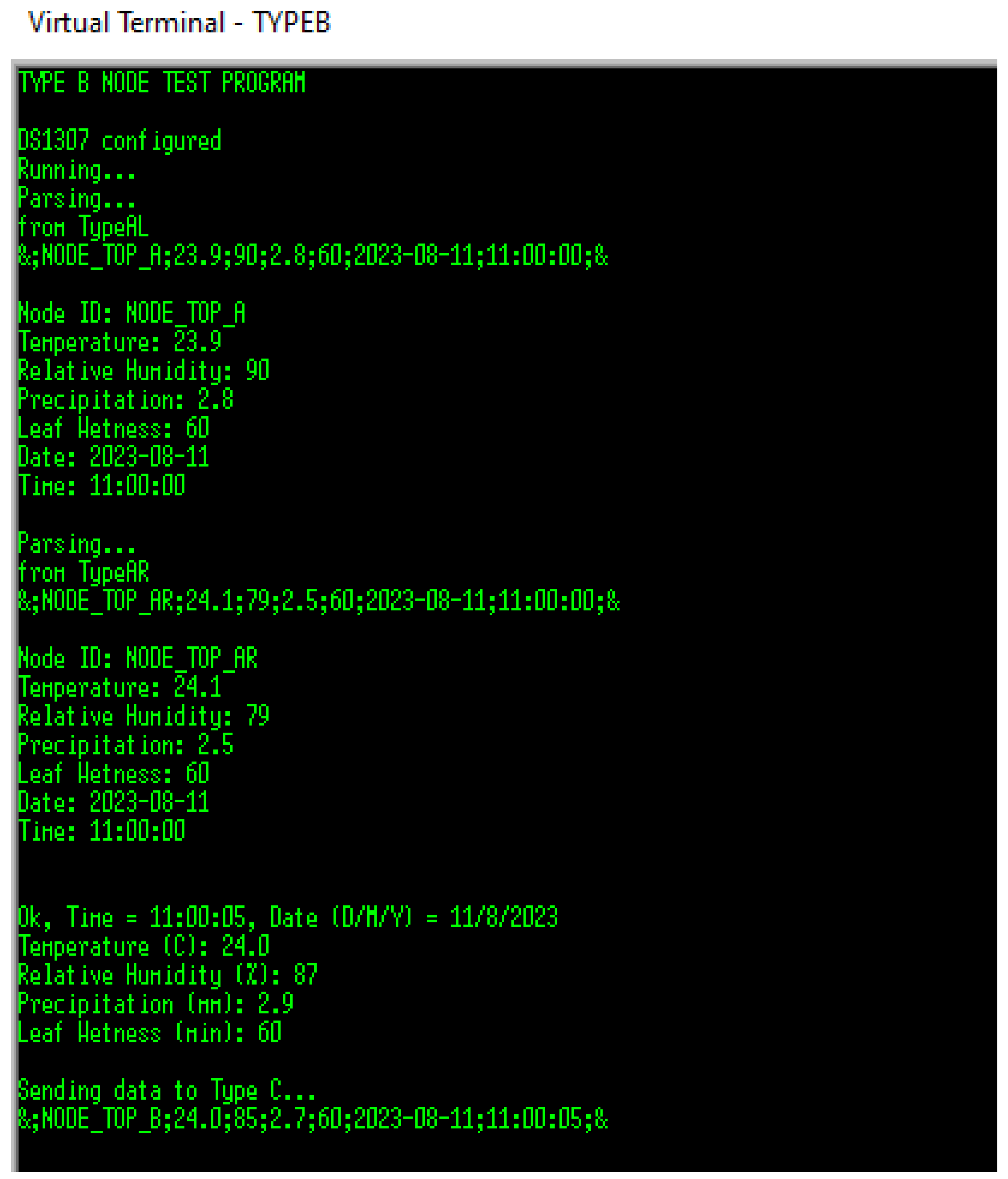

- Development of a simulation model of the Type B network node utilizing Arduino Mega 2560 in the Proteus environment detailed in Appendix A and illustrated in Figure 7. This simulation model integrates software developed in the Arduino IDE (see Appendix A), which aggregates measurement data from Type A network nodes, polls its own soil and climate sensors, performs preliminary statistical analysis (time and space averaging), and transmits the result to the Type C base station using LoRa technology (see Figure 8).

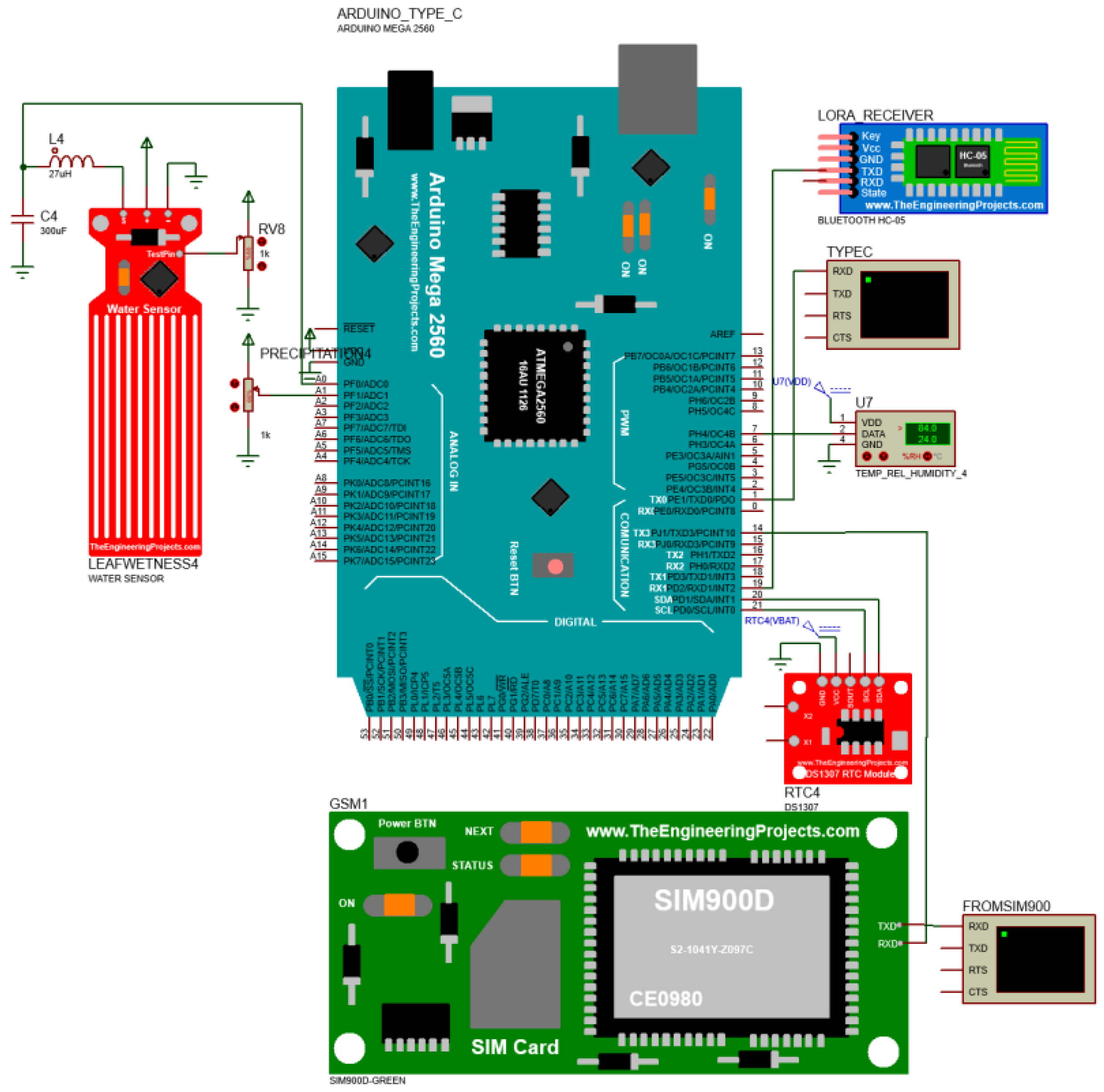

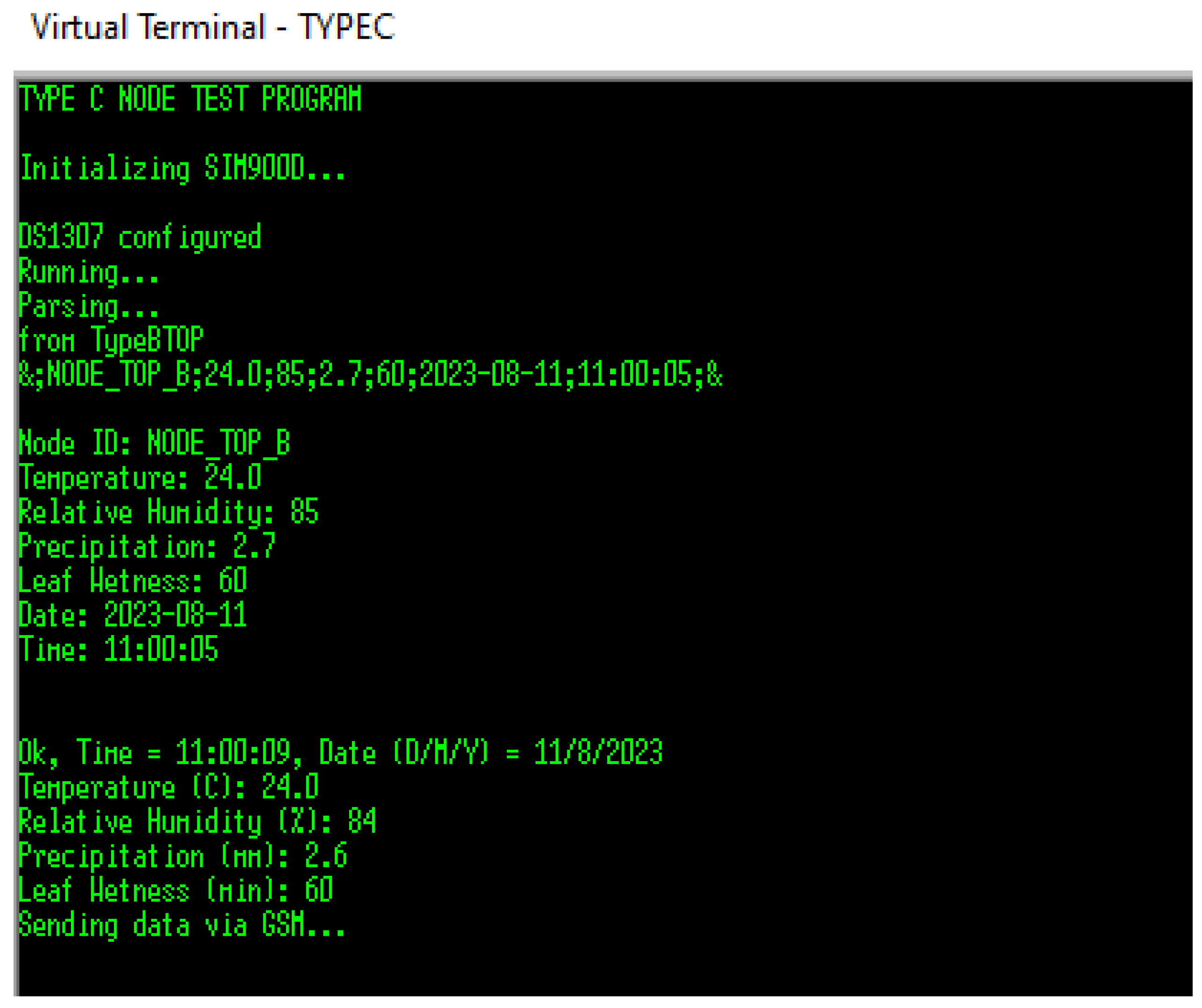

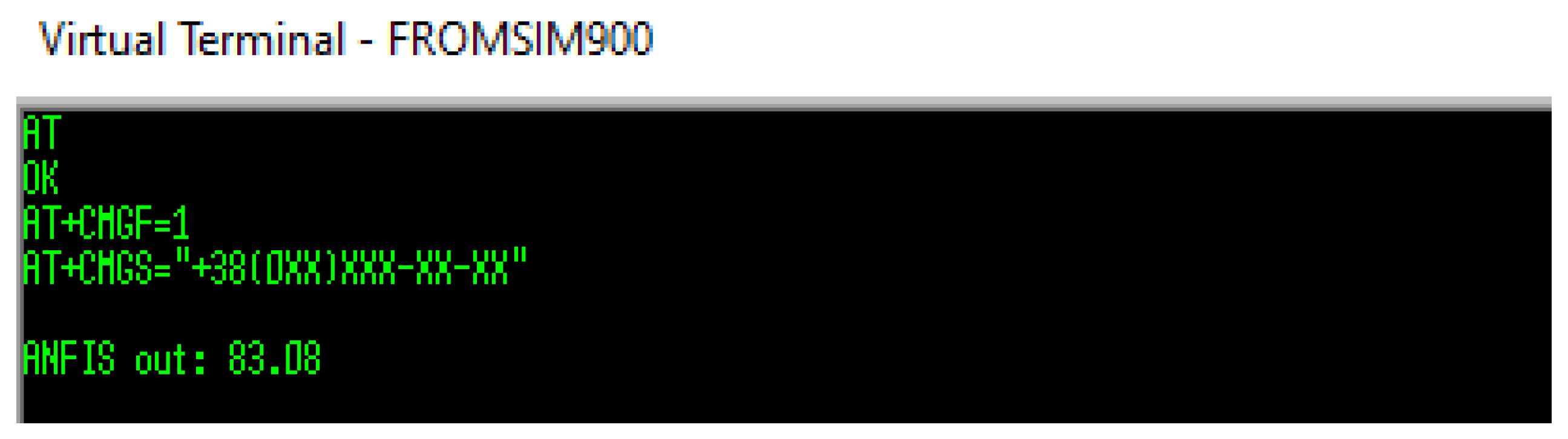

- This simulation model includes software code that aggregates measurement data from Type B network nodes, polls its own soil and climate sensors, performs preliminary statistical analysis (time and space averaging), uses ANFIS to predict the probability of the occurrence of the crop disease, and sends an SMS with the result of the intelligent analysis to a specified number.

- Testing the modes of functioning of the developed computer model by detecting data transmitted as a result of network interaction of various protocols at different architectural levels of the IoT system using a virtual terminal. These steps enabled an evaluation of the accuracy and resilience of the proposed hardware and software solution.

3.2. Results of the Development and Modelling of the Network Organisation of the IoT System

4. Discussion

- Accounting for aggressive environmental conditions requires more thorough research on the reliability of microelectronic components.

- The impact of the battery life of portable power modules on the continuous operation of an IoT system.

- Assessment of the influence of natural and man-made interference on the efficiency of signal transmission over certain distances in real conditions.

5. Conclusions

- A comprehensive analysis of the subject area of digitalisation of agriculture has been carried out, which allowed to localise the directions of perspective research of this article, taking into account modern scientific and applied achievements in the field of IoT systems, approaches to their computer modelling and technology of intelligent analysis of time series of measurement monitoring results.

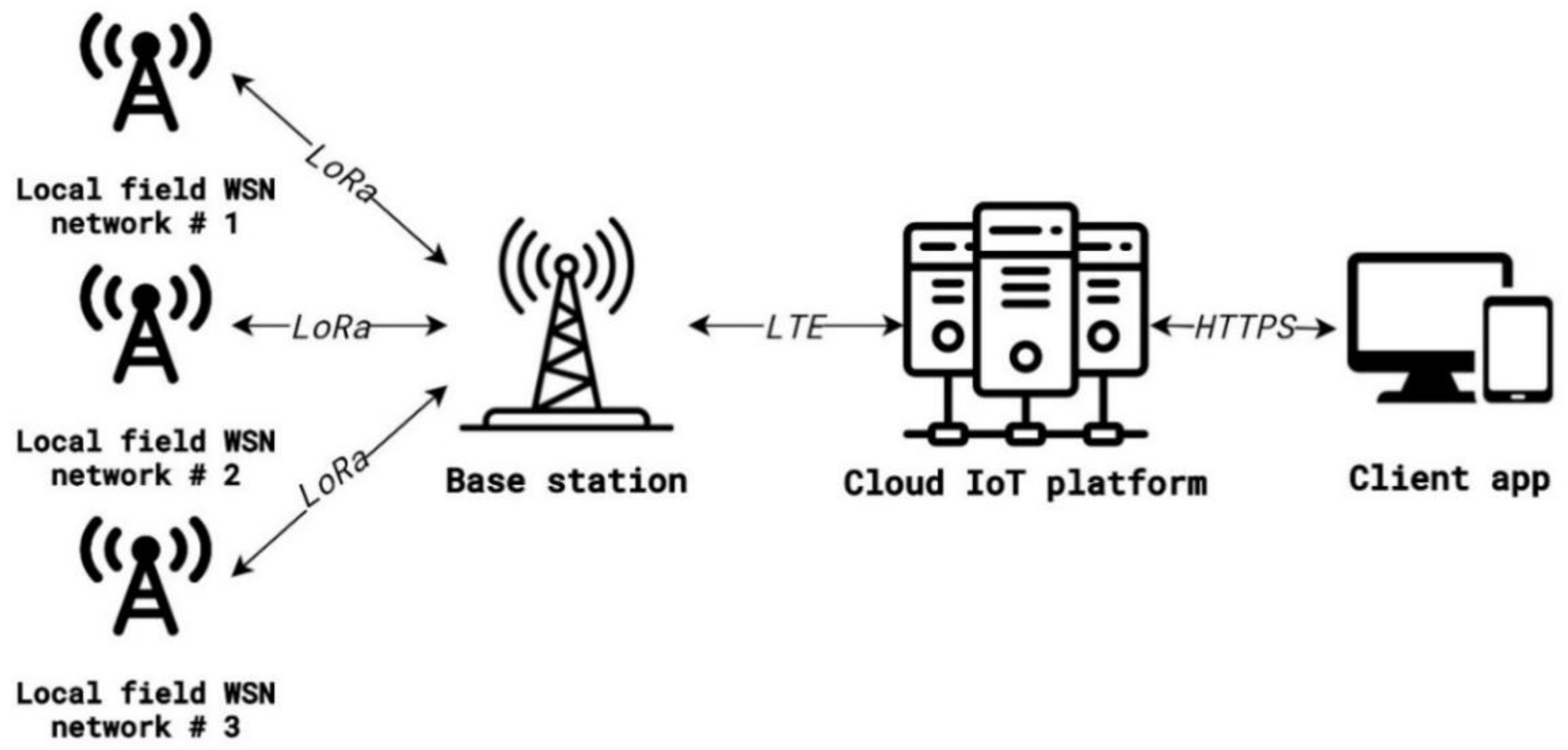

- The structural and algorithmic organisation of the information and communication infrastructure of the agrotechnical monitoring network of the IoT system, which implements the principles of edge computing and takes into account the results of previous studies and reflects their implementation, taking into account the integral influence of the criteria that determine the number of wireless network modules and the reliability of measurement data exchange, has been developed.

- The computer model has been implemented in the Proteus environment, which allowed testing and validating the network interaction of various protocols at different architectural levels of the IoT system according to the criterion of objective testing of algorithms for multi-level data aggregation, processing and transmission.

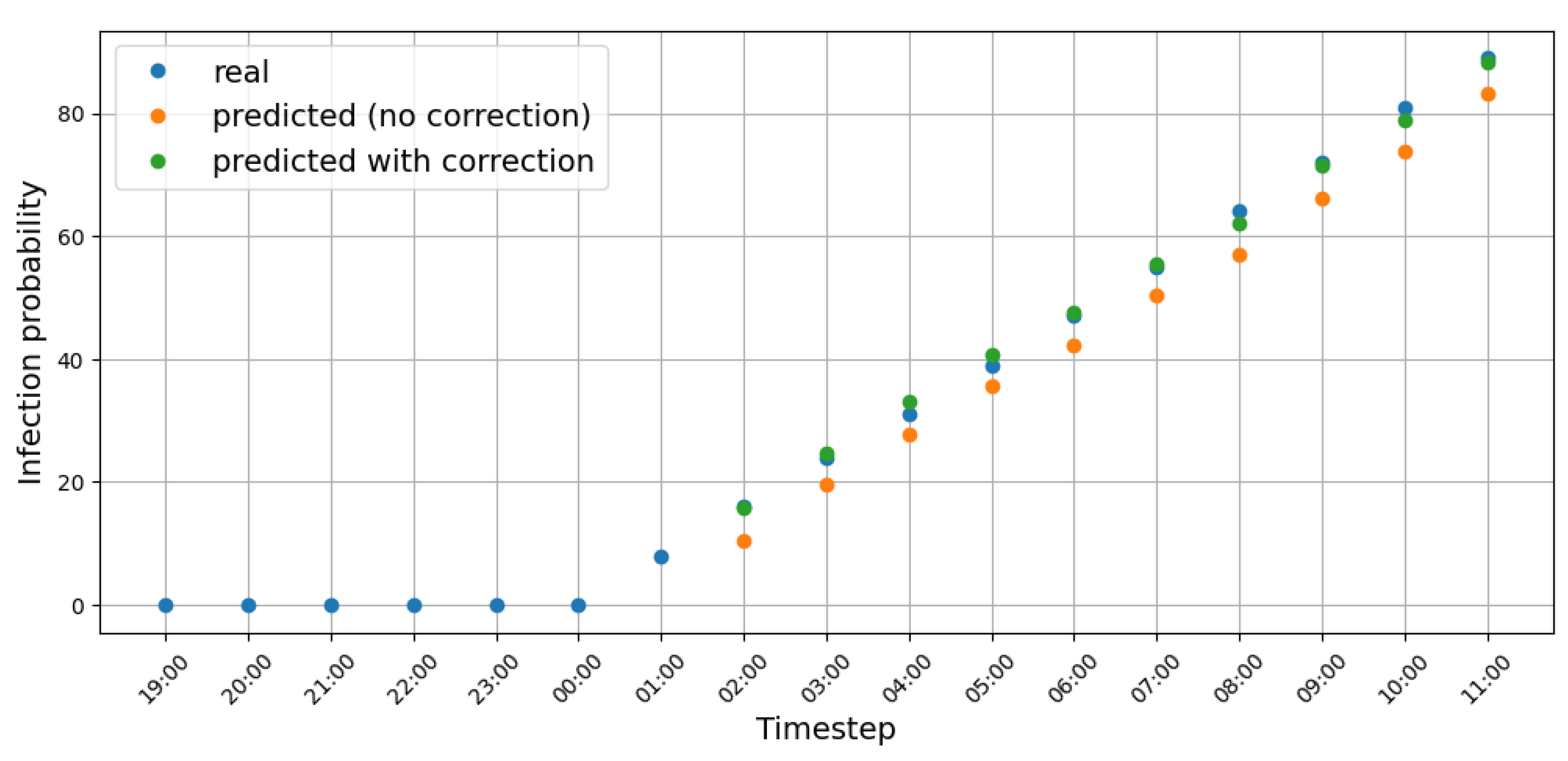

- Data processing software based on ANFIS technology has been developed for the microprocessor unit of the system, which allowed the analysis of the results obtained at the qualitative and quantitative levels.

- The error of data approximation has been estimated at (5.2±1.4)%. As a result, an approach to its reduction has been proposed based on introducing the correction to the prediction results. The value of the error after compensation does not exceed (1.1±0.7)%.

Acknowledgement

Appendix A. The Software Used

- Online training version of software Matlab & Simulink: https://www.mathworks.com/products/matlab-online.html

- Open-source Arduino IDE https://www.arduino.cc/en/software

- Online training version of software Proteus: https://www.labcenter.com/education/

- Open-source tool for converting fis-models into Arduino code: http://www.makeproto.com/projects/fuzzy/matlab_arduino_FIST/index.php

References

- FAO. Climate change and food security: risks and responses. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i5188e/I5188E.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- IFPRI. Research and engagement: Climate change and agrifood systems. Available online: https://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/136977/filename/137188.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Breisinger, C.; Keenan, M.; Mbuthia, J.; Njuki, J. Food systems transformation in Kenya: Lessons from the past and policy options for the future. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), 2023.

- Piot-Lepetit, I. Digitainability and open innovation: how they change innovation processes and strategies in the agrifood sector? Frontiers in sustainable food systems 2023, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lozano, R.; Baruth, B. An evaluation framework to build a cost-efficient crop monitoring system. Experiences from the extension of the European crop monitoring system. Agricultural Systems 2019, 168, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placidi, P.; Morbidelli, R.; Fortunati, D.; Papini, N. ; Gobbi,F.; Scorzoni, A. Monitoring Soil and Ambient Parameters in the IoT Precision Agriculture Scenario: An Original Modeling Approach Dedicated to Low-Cost Soil Water Content Sensors. Sensors, 2021; 21, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, B. The research of IOT of agriculture based on three layers architecture. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Cloud Computing and Internet of Things (CCIOT), Dalian, China, 162-165., 1 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

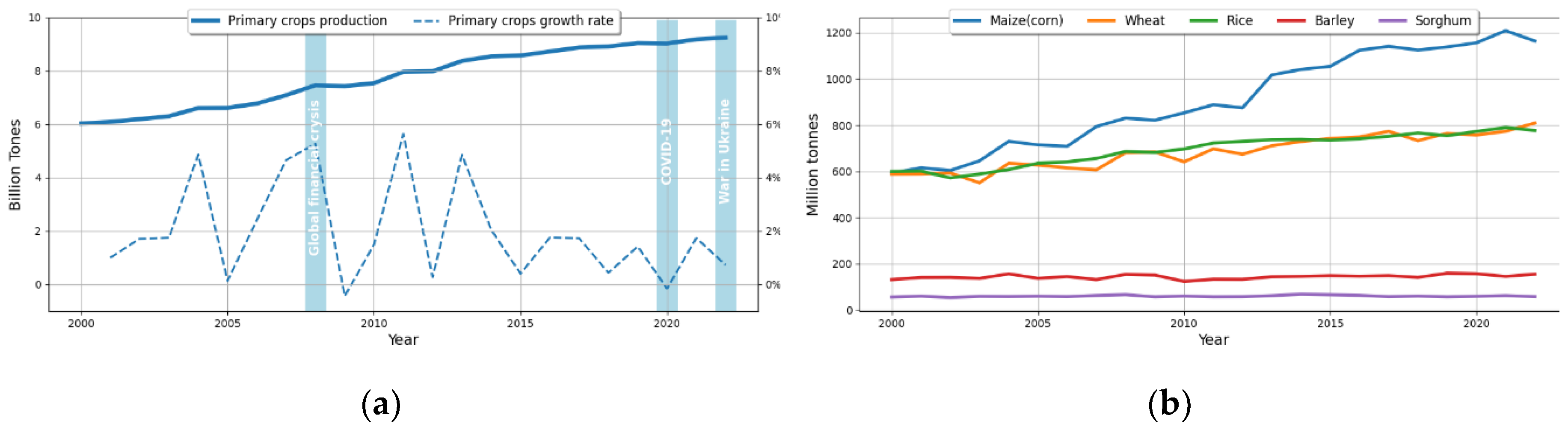

- FAO. Agricultural production statistics 2000-2022, FAOSTAT Analytical Briefs, No. 79, Rome. [CrossRef]

- FAO. Production: Crops and livestock products, In: FAOSTAT, Rome. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- FAO. Food Price Index down again in January led by lower wheat and maize prices, In: FAO News and Media (Rome). Available online: https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/fao-food-price-index-down-again-in-january-led-by-lower-wheat-and-maize-prices/en (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- FAO. Cereal Supply and Demand Brief: Larger coarse grain outputs push up supply and trade prospects. Available online: https://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/csdb/en (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Laktionov, I.; Diachenko, G.; Koval, V.; Yevstratiev, M. Computer-Oriented Model for Network Aggregation of Measurement Data in IoT Monitoring of Soil and Climatic Parameters of Agricultural Crop Production Enterprises. Baltic Journal of Modern Computing 2023, 11, 500–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juniperresearch. IoT Connections to Reach 83 Billion by 2024, Driven by Maturing Industrial Use Cases. Available online: https://www.juniperresearch.com/press/iot-connections-to-reach-83-bn-by-2024 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Industryarc. Massive IoT (MIoT) Market – Forecast (2025-2032). Available online: https://www.industryarc.com/Report/19418/massive-iot-market.html (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Alam, Md.F.B.; Tushar, S.R.; Zaman, S.Md.; Gonzalez, E.D.R.S.; Bari, A.B.M.M.; Karmaker, C.L. Analysis of the drivers of Agriculture 4.0 implementation in the emerging economies: Implications towards sustainability and food security. Green Technologies and Sustainability, 2023; 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt, H.; Bozkurt, M.; Brunsch, R.; Colangelo, E.; Herrmann, A.; Horstmann, J.; Kraft, M.; Marquering, J.; Steckel, T.; Tapken, H.; Weltzien, C.; Westerkamp, C. Challenges for Agriculture through Industry 4.0. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charania, I.; Li, X. Smart farming: Agriculture's shift from a labor intensive to technology native industry. Internet of Things 2020, 9, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.; Frecassetti, S.; Rossini, M.; Portioli-Staudacher, A. Industry 4.0 digital technologies enhancing sustainability: Applications and barriers from the agricultural industry in an emerging economy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2023; 408, 137208. [Google Scholar]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Enhancing smart farming through the applications of Agriculture 4.0 technologies. International Journal of Intelligent Networks 2022, 3, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunathilake, E.M.B.M.; Le, A.T.; Heo, S.; Chung, Y.S.; Mansoor, S. The Path to Smart Farming: Innovations and Opportunities in Precision Agriculture. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffezzoli, F.; Ardolino, M.; Bacchetti, A.; Perona, M.; Renga, F. Agriculture 4.0: A systematic literature review on the paradigm, technologies and benefits. Futures, 2022; 142, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Morchid, A.; Alami, R.E.; Raezah, A.A.; Sabbar, Y. Applications of internet of things (IoT) and sensors technology to increase food security and agricultural Sustainability: Benefits and challenges. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2024, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowla, M.N.; Mowla, N.; Shah, A.F.M.S.; Rabie, K.M.; Shongwe, T. Internet of Things and Wireless Sensor Networks for Smart Agriculture Applications: A Survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 145813–145852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moysiadis, V.; Sarigiannidis, P.; Vitsas, V.; Khelifi, A. Smart Farming in Europe. Computer Science Review 2021, 39, 100345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, M.; Gupta, S.; Chamola, V.; Elhence, A.; Garg, T.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Niyato, D. A survey on the role of Internet of Things for adopting and promoting Agriculture 4.0. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2021, 187, 103107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.C.; Wheeler, R.; Winter, M.; Lobley, M.; Chivers, C.-A. Agriculture 4.0: Making it work for people, production, and the planet. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaerjan, A. Towards Sustainable Distributed Sensor Networks: An Approach for Addressing Power Limitation Issues in WSNs. Sensors 2023, 23, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, H. Role of wireless sensor network in precision agriculture. Computational algorithms and numerical dimensions 2022, 1, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- López-Martínez, J.; Blanco-Claraco, J.L.; Pérez-Alonso, J.; Callejón-Ferre, Á.J. Distributed network for measuring climatic parameters in heterogeneous environments: Application in a greenhouse. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2017, 145, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawandar, N.K.; Satpute, V.R. IoT based low cost and intelligent module for smart irrigation system. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 162, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T. Distributed compressive and collaborative sensing data collection in mobile sensor networks. Internet of Things 2019, 9, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, M.R.; Daely, P.T.; Kim, D.-S.; Lee, J.M. IoT-based adaptive network mechanism for reliable smart farm system. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 170, 105287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, S.; Spachos, P. Wireless technologies for smart agricultural monitoring using internet of things devices with energy harvesting capabilities. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 172, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srbinovska, M.; Gavrovski, C.; Dimcev, V.; Krkoleva, A.; Borozan, V. Environmental parameters monitoring in precision agriculture using wireless sensor networks. Journal of Cleaner Production 2015, 88, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y. Internet-of-Things-Based Multiple-Sensor Monitoring System for Soil Information Diagnosis Using a Smartphone. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, G.; Giovino, I.; Vallone, M.; Catania, P.; Argento, A. A decision support system based on multisensor data fusion for sustainable greenhouse management. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 172, 4057–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrijevi´c, N.; Uroševi´c, V.; Arsi´c, B.; Herceg, D.; Savi´c, B. IoT Monitoring and Prediction Modeling of Honeybee Activity with Alarm, Electronics 2022, 11, 783.

- CropX. CropX System Disease Control. Available online: https://cropx.com/cropx-system/disease-control/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- dos Santos, U.J.L.; Pessin, G.; da Costa, C.A.; da Rosa Righi, R. AgriPrediction: A proactive internet of things model to anticipate problems and improve production in agricultural crops. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 161, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. Watson Decision Platform for Agriculture. Available online: https://worldagritechusa.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Dan-Wolfson-IBM.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Laktionov, I.; Vovna, O.; Kabanets, M. Information Technology for Comprehensive Monitoring and Control of the Microclimate in Industrial Greenhouses Based on Fuzzy Logic. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Soft Computing Research 2023, 13, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chana, I.; Buyya, R. Agri-Info: Cloud Based Autonomic System for Delivering Agriculture as a Service. Internet of Things 2020, 9, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Shrivastava, G.; Kumar, P. Architecting user-centric internet of things for smart agriculture. Sustainable Computing: Informatics and Systems 2019, 23, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ali, R.; Aridhi, E.; Mami, A. Dynamic model of an agricultural greenhouse using Matlab-Simulink environment. In Proceedings of the 12th International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD), 346-350., 1 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Faouzi, D; Bibi-Triki, N.; Draoui B.; Abène, A. Modeling, Simulation and Optimization of agricultural greenhouse microclimate by the application of artificial intelligence and / or fuzzy logic. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research 2016, 7, 204–214.

- Ivanov, D.V.; Hnatushenko, V.V.; Kashtan, V.Yu.; Garkusha, I.M. Computer modeling of territory flooding in the event of an emergency at seredniodniprovska hydroelectric power plant. Naukovyi Visnyk Natsionalnoho Hirnychoho Universytetu 2022, 6, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kephe, P.N.; Ayisi, K.K.; Petja, B.M. Challenges and opportunities in crop simulation modelling under seasonal and projected climate change scenarios for crop production in South Africa. Agric & Food Secur 2021, 10, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Laktionov, I.; Vovna, O.; Cherevko, O.; Kozlovskaya, T. Mathematical model for monitoring carbon dioxide concentration in industrial greenhouses. Agronomy Research 2018, 16, 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Laktionov, I.S.; Vovna, O.V.; Kabanets, M.M.; Derzhevetska, M.A.; Zori, A.A. Mathematical Model of Measuring Monitoring and Temperature Control of Growing Vegetables in Greenhouses. International Journal of Design & Nature and Ecodynamics 2020, 15, 325–336. [Google Scholar]

- Laktionov, I.S.; Vovna, O.V.; Kabanets, M.M.; Sheina, H.O.; Getman, I.A. Information model of the computer-integrated technology for wireless monitoring of the state of microclimate of industrial agricultural greenhouses. Instrumentation Mesure Métrologie, 2021; 20, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalyov, A. ; Hnatushenko,V.; Hnatushenko, V., Ed.; Vladimirska, N. Optimization model lifetime wireless sensor network. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems: Technology and Applications (IDAACS), Warsaw, Poland, 01 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov, S. Optimization of greenhouse microclimate parameters considering the impact of CO2 and light. Journal of Engineering Sciences 2023, 10, G14–G21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.N.; Shaikh, A.J.; Khan, A.; Awais, H.; Bakar, E.A.; Othman, A.R. Smart Sensing with Edge Computing in Precision Agriculture for Soil Assessment and Heavy Metal Monitoring: A Review. Agriculture 2021, 11, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassine, F.Z.; Epule, T.E.; Kechchour, A.; Chehbouni, A. Recent Applications of Machine Learning, Remote Sensing, and IoT Approaches in Yield Prediction: a Critical Review. Preprint 2023, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fenu, G.; Malloci, F.M. Review forecasting plant and crop disease: An explorative study on current algorithms. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2021, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.L.; Ke, Y.X.; Hua, X.D. Application status and prospect of edge computing in smart agriculture. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. (Trans. CSAE), 2022; 38, 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Kashtan, V.; Hnatushenko, V. Deep Learning Technology for Automatic Burned Area Extraction Using Satellite High Spatial Resolution Images; Babichev, S. , Lytvynenko, V., Eds.; Volume 149, Springer, Cham, 664-685. Lecture Notes in Data Engineering, Computational Intelligence, and Decision Making, Babichev, S., Lytvynenko, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham; Volume 149, 664–685.

- Laktionov, I.; Diachenko, G.; Rutkowska, D.; Kisiel-Dorohinicki, M. An Explainable AI Approach to Agrotechnical Monitoring and Crop Diseases Prediction in Dnipro Region of Ukraine. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Soft Computing Research 2023, 13, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, S.; Kühl, R. Acceptance of artificial intelligence in German agriculture: an application of the technology acceptance model and the theory of planned behavior. Precision Agric. 2021, 22, 1816–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Grady, M.J.; Langton, D.; O'Hare, G.M.P. Edge computing: A tractable model for smart agriculture? Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture 2019, 3, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, W.; Qi, L.; Yaqoob, I.; Imran, M.; Rasool, R.U.; Dou, W. Complementing IoT services through software defined networking and edge computing: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2020, 22, 1761–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryo, M. Explainable artificial intelligence and interpretable machine learning for agricultural data analysis. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture 2022, 6, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Li, W.; Kai, Y.; Chen, P.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B. Occurrence prediction of pests and diseases in cotton on the basis of weather factors by long short term memory network. BMC Bioinformatics 2019, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, C.; Heidari, A.A.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, H.; Mafarja, M.; Turabieh, H. Corn Leaf Diseases Diagnosis Based on K-Means Clustering and Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 143824–143835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cao, Z.; Dong, W. Overview of Edge Computing in the Agricultural Internet of Things: Key Technologies, Applications, Challenges. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 141748–141761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, M. A Smart Farming Concept Based on Smart Embedded Electronics. Internet of Things and Wireless Sensor Network, Internet of Things 2020, 9, 100161. [Google Scholar]

- Pamula, A.S.P.; Ravilla, A.; Madiraju, S.V.H. Applications of the Internet of Things (IoT) in Real-Time Monitoring of Contaminants in the Air, Water, and Soil. Engineering Proceedings 2022, 27, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Molodets, B.; Hnatushenko, V.; Boldyriev, D.; Bulana, T. Information System of Air Quality Assessment Based of Ground Stations and Meteorological Data Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Intelligent Information Technologies and Systems of Information Security, Khmelnytskyi, Ukraine, 22-24 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, F.; Karim, F.; Frihida, A. Monitoring system using web of things in precision agriculture. Procedia Computer Science 2017, 110, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.I.; Zorlu Partal, S. Development and performance analysis of a ZigBee and LoRa-based smart building sensor network. Frontiers in Energy Research 2022, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holovatyy, A.; Teslyuk, V.; Kryvinska, N.; Kazarian, A. Development of Microcontroller-Based System for Background Radiation Monitoring. Sensors 2020, 20, 7322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, A.; Kumaravelu, V.B. Scalable and Sustainable Wireless Sensor Networks for Agricultural Application of Internet of Things using Fuzzy-C Means Algorithm. Sustainable Computing: Informatics and Systems 2019, 22, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.-T.; Nayyar, A.; Ahmad Lone, S. System Performance of Wireless Sensor Network Using LoRa–Zigbee Hybrid Communication. Computers, Materials & Continua 2021, 68, 1615–1635. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, S.; Kuchhal, P.; Anita, R.S. ZigBee and Bluetooth Network based Sensory Data Acquisition System. Procedia Computer Science 2015, 48, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holovatyy, А. Development of IoT Weather Monitoring System Based on Arduino and ESP8266 Wi-Fi Module, In Proceedings of the IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Lviv, Ukraine, 26-27 November 2020, 1016, 012014. [Google Scholar]

- Lova Raju, K.; Vijayaraghavan, V. IoT-AgriSens: A LoRa-Based Smart Agriculture Monitoring and Decision-Making System with Amalgamation of IoT and Cloud-Enabled Services. Research Square, 2023; 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Laktionov, I.S.; Vovna, O.V.; Zori, A.A.; Lebedev, V.A. Results of simulation and physical modeling of the computerized monitoring and control system for greenhouse microclimate parameters. International Journal on Smart Sensing and Intelligent Systems 2018, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S.D.; Odoma, D.Y.; Loko, A.Z. Simulation and Construction of a Microcontroller based Plant Water Sprinkler with Weather Monitoring System. International Journal of Computer Applications 2022, 184, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, A.; Limkar, A. IoT Based Machine Learning Weather Monitoring and Prediction Using WSN. International Journal on Recent and Innovation Trends in Computing and Communication 2024, 12, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakthavatchalam, K.; Karthik, B.; Thiruvengadam, V.; Muthal, S.; Jose, D.; Kotecha, K.; Varadarajan, V. IoT Framework for Measurement and Precision Agriculture: Predicting the Crop Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Technologies 2022, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The research subject | Technologies used | Scientific source |

|---|---|---|

| Development of scientifically grounded approaches to improving the efficiency of IoT systems for agrotechnical monitoring based on the optimality criterion, which takes into account the simultaneous influence of factors such as maximum uptime of hardware and software components, maximum network coverage area, and minimum number of wireless sensor modules used.entry 1 | WSN, ZigBee, LoRa, LTE, IoT cloud, CupCarbon |

[12] |

| Development of scientific and applied approaches to improve computer-integrated microclimate monitoring systems for industrial agricultural greenhouses. | GSM / GPRS, IoT Cloud |

[50] |

| Development of a farm management system based on embedded systems, IoT and WSN for agricultural field and livestock farms. | IoT, WSN, GSM, Wi-Fi |

[66] |

| A framework that combines the sensor layer, network layer, and visualisation layer to observe progressive trends in environmental data while being cost-effective. | IoT, EnviroDIY, Python |

[67] |

| Development of an information system for assessing air quality based on data from ground stations and monitoring of meteorological data, which solves the problem of sending out alerts about the danger to people. | Docker, REST, API, CALPUFF, WRF | [68] |

| An alert system for monitoring water deficit in plants using IoT technologies. | IoT cloud, WSN, ZigBee |

[69] |

| WSN using ZigBee and LoRa communication protocols for integration into energy management systems of smart buildings. | WSN, ZigBee, LoRa |

[70] |

| Development of a microcontroller system for monitoring the radiation background using the Arduino Uno board the Geiger counter SBM-20. | Petri nets, Geiger–Mueller counter |

[71] |

| Building an energy-efficient, resilient WSN while maximising node density and coverage using the FCM clustering algorithm. | WSN, FCM | [72] |

| Investigation of the performance of a heterogeneous WSN system using hybrid LoRa-Zigbee communication. | ZigBee, LoRa, MQTT, ThinkSpeak, Blynk |

[73] |

| The system of data collection for factories and industrial enterprises or environmental monitoring is offered, which measures certain parameters, such as temperature, humidity, level of gases present in the atmosphere, movement of any person near the prohibited zone at a certain moment of time and transmits these parameters to the control room wirelessly. | Bluetooth, WSN, ZigBee | [74] |

| Development of hardware and software for an IoT weather monitoring system based on the Arduino Mega2560 board, digital pressure, temperature and humidity sensor BME280, and Wi-Fi module ESP-01 built on the ESP8266 chip. | ThingsBoard IoT, MQTT, Node-RED, Wi-Fi | [75] |

| Development and implementation of a LoRa-based IoT system to monitor five dynamic parameters, including air temperature and humidity, soil temperature and moisture and soil pH. | IoT, LoRa, Wi-Fi, ThinkSpeak | [76] |

| Research on the development and laboratory testing of imitation and physical models of a computerised system for monitoring and controlling microclimate parameters in industrial greenhouses. | Proteus | [77] |

| Testing and modelling of an automatic plant irrigation system based on an Arduino microcontroller with a weather monitoring system. | Proteus | [78] |

| Development of a new approach to real-time meteorological data analysis and forecasting using an integrated system based on IoT, WSN, and ML. | IoT, WSN, RNN, ANN, RF | [79] |

| Development of a model that predicts high crop yields and precision farming. | IoT, WEKA, ML | [80] |

| IoT system components | Type of node | Proteus library equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature sensor | Type A, Type B, Type C | DHT22 |

| Relative humidity sensor | ||

| Precipitation sensor | Type A, Type B, Type C | POT-HG 10 kΩ, POWER, GROUND |

| Leaf wetness sensor | Type A, Type B, Type C | WATER SENSOR, CAP 300 uF, INDUCTOR 27 uH, POT_HG 1 kΩ, GROUND, POWER |

| Real-time clock | Type A, Type B, Type C | DS1307, DC Generator 5 V, GROUND |

| NRF module | Type A, Type B | MODULO RX (modulo rf library), MODULO TX (modulo rf library), GROUND, POWER, |

| LoRa module | Type B, Type C | HC-05 based on Serial Interface |

| GSM shield | Type C | SIM900D-GREEN |

| Arduino Uno Rev3 | Type A | ARDUINO UNO R3 |

| Arduino Mega 2560 Rev3 | Type B, Type C | ARDUINO MEGA 2560, GROUND, POWER |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).