1. Introduction

Muconic acid is a natural organic acid that can be used as a synthetic precursor for raw materials, such as terephthalic acid [

1], which is used to make PET bottles and poly-ethylene, adipic acid [

2], which is used to make nylon-6,6, and ε-caprolactam [

3,

4], which is used to make nylon 6 [

5,

6,

7]. Due to the expected growth in demand for textiles and plastic products, the market size of muconic acid is estimated to range from US

$102.32 million to US

$111.27 million in 2023. The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) is expected to range from 7.11% to 8.72%, which is expected to take the market size of muconic acid from US

$183.77 million to over US

$179.96 million by 2030 [

8,

9]. A low-cost process for producing muconic acid for commercial use is currently being investigated but has not yet been established [

10]. A biological synthesis of

cis,cis-muconic acid (ccMA) by metabolizing natural raw materials such as glucose, xylose [

11,

12], and lignin [

13,

14] by modified

E. coli has also been reported. These biochemical syntheses are considered a sustainable approach. However, there are some problems in applying biochemical synthesis to industrial large-scale production, such as the need to use low-concentration culture media to prevent toxicity to microorganisms, and the difficulty of the extraction and purification process of the ccMA produced [

15]. Therefore, chemical methods are advantageous for the industrial synthesis of muconic acid.

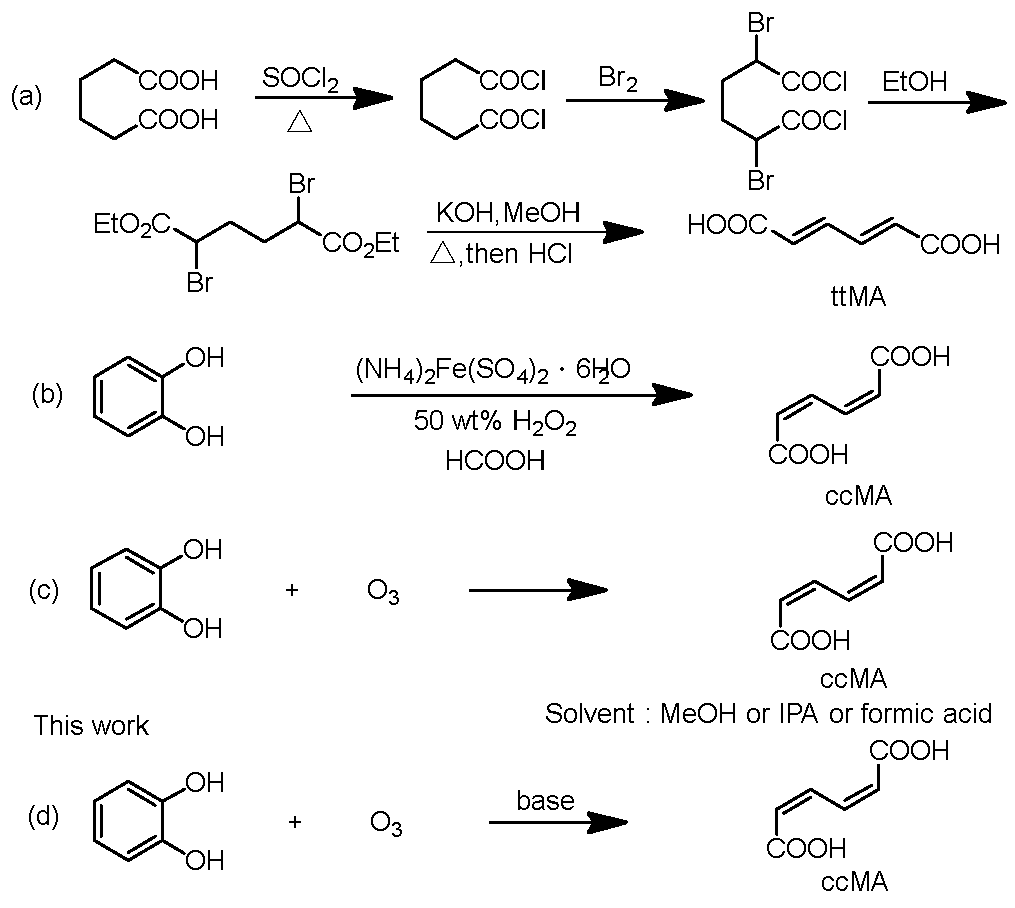

A

trans,trans-muconic acid (ttMA), which is a thermo-chemically stable, was synthesized by a elimination reaction using adipic acid as a starting material (

Scheme 1a)[

16]. However, this method requires the use of thionyl chloride and bromine, which raises concerns regarding environmental toxicity and hazards during synthesis. And due to multi-step synthesis process, it is also undesirable from the perspective of green chemistry. On the other hand, there have been several reports on the synthesis of ccMA by ring-opening reaction of catechol as a starting material [

15]. The reaction in a 50% hydrogen peroxide and formic acid mixture in a solvent yields ccMA in a high yield of about 80% (

Scheme 1b)[

15]. However, this method is not widely practical because of the difficulty of obtaining 50% hydrogen peroxide and the risk of explosive decomposition or chemical reaction explosions at ambient temperature and pressure, which pose significant storage, transport, and handling concerns [

17]. In addition, chemical synthesis methods for ccMA and its derivatives have also been reported [

18,

19]. However, since these methods used metal catalysts, post-treatment was complicated for industrial synthesis, and the use of dichloromethane and the large amount of pyridine required were of concern.

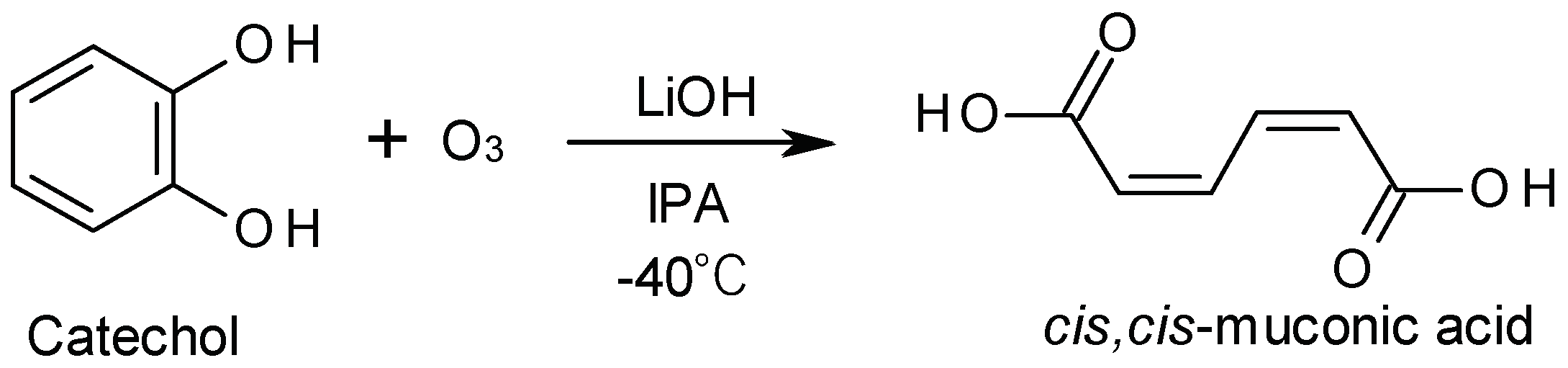

In general, the oxidative decomposition reaction of double bonds with ozone is a clean and effective option because it is easy to perform [

20]. In two patents by Siggel and Spengler, it was claimed that the yield of ccMA based on ozonolysis of catechol (

Scheme 1c) was between 28.2% and 54.9% [

21,

22]. However, the actual yields reported in the academic paper ranged from only 0.9% to 31.5%, much lower than the values claimed in the patents [

23]. This discrepancy suggests that the reaction conditions described in the patents may not reliably achieve the claimed yields. The reasons for the low yield in the reaction with ozone may be that the ccMA produced is decomposed to glyoxylate, oxalic acid, and other acids by excessive reaction with ozone [

24,

25].

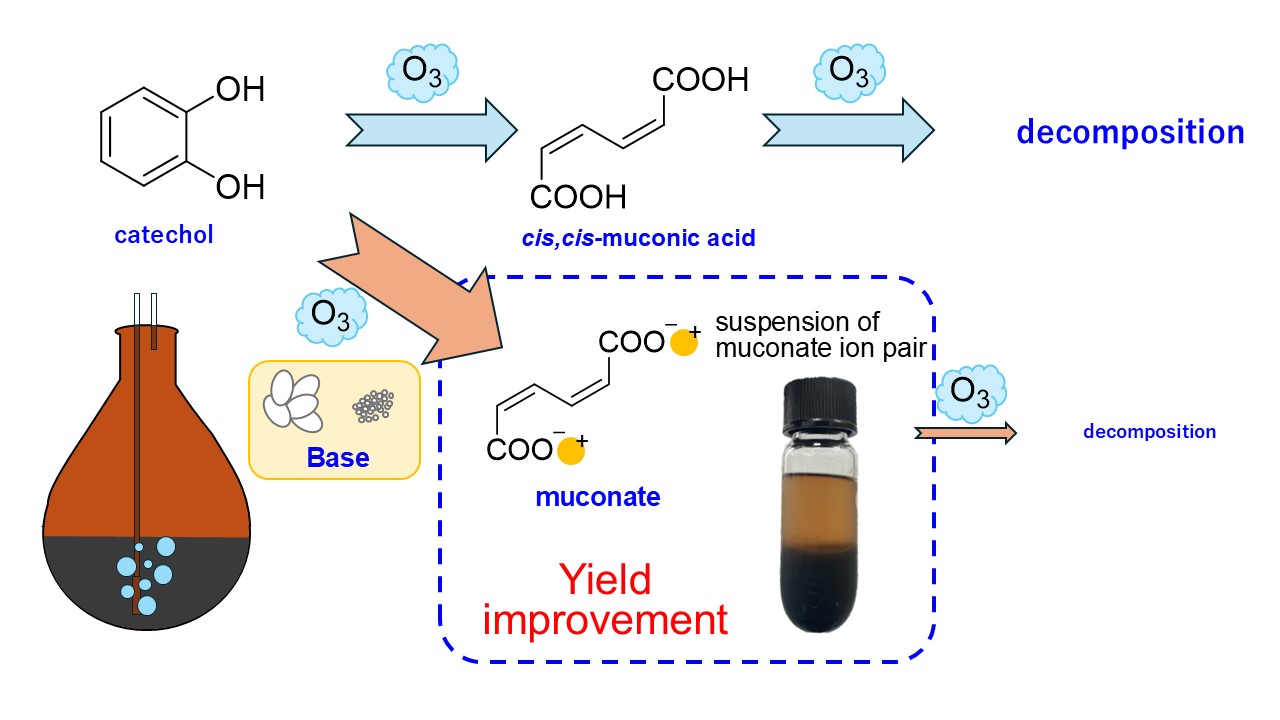

In contrast, we have developed, in this study, a new method for synthesizing ccMA sodium salt with a high yield of 56% by employing the approach of adding a hydrophilic base to the reaction solution (

Scheme 1d). This method enabled an efficient one-step synthesis of ccMA from catechol, which significantly reduced the amount of reagents, time, and labor compared to conventional methods. This new approach offers significant advantages not only from an economic perspective but also in terms of sustainable manufacturing, aligning with the principles of green chemistry.

2. Results and Discussion

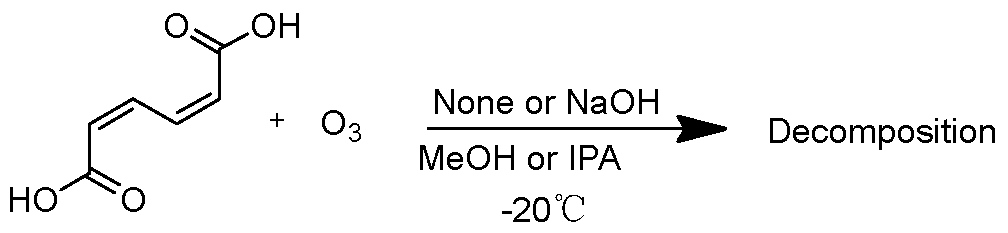

2.1. Decomposition of ccMA by Ozone

At first, oxidative decomposition of ccMA by ozone was evaluated. ccMA was dissolved in IPA or MeOH, and oxygen gas containing ozone was bubbled through the solution, either with or without the addition of granulated NaOH (its particle size was less than 0.7 mm) (

Scheme 2).

A 1.4 g (10 mmol) of commercially available ccMA was added to a brown colored flask. IPA or MeOH 100 mL was added and dissolved. A 1.2 g (30 mmol) of NaOH was added to the flask and stirred at room temperature for 10 minutes. The flask was placed in a cooling bath at −20°C and stirred for 10 minutes. Oxygen (standard condition) containing 27 mg L−1 ozone was bubbled into the flask at a rate of 1 L min−1. During the reaction with ozone, the solution was stirred by a magnetic stirrer and the bubbling. After 15 minutes, the ozone generator was turned off and bubbling continued for 5 minutes at room temperature to remove remaining ozone gas from the reaction system. Distilled water was added to the reaction solution to dissolve the product precipitate and undissolved sodium hydroxide. The solution was diluted to 1 L in a measuring flask. This diluted solution was further diluted 10-fold, and the solution was analyzed by HPLC system and in the chromatogram, the peak areas at 257 nm and 277 nm were calculated for the determination of ccMA.

It has been reported that ozone does not react significantly with MeOH when the ozone-reactive olefin is dissolved in MeOH, and the solution temperature is maintained at −20 °C [

27]. The data are shown in

Table 1.

From the results of entries 1 and 3, the amount of ccMA remaining in the IPA solution after 1 hour of reaction was greater than that in the MeOH solution, meaning that oxidation of ccMA by ozone occurred slower in IPA because the solubility of ozone is lower in IPA than in MeOH. In contrast, the addition of NaOH significantly increased the percentage of ccMA remaining for both solvents. In this case, there was no difference in the amount of ccMA remaining in IPA and MeOH (compare entries 2 with 4). A white suspension was observed in the reaction flask when NaOH was added. These results suggest that the addition of NaOH during the synthesis of ccMA may create a suspension of the sodium muconate ion pair in the solution during the reaction, making it less likely to react with ozone.

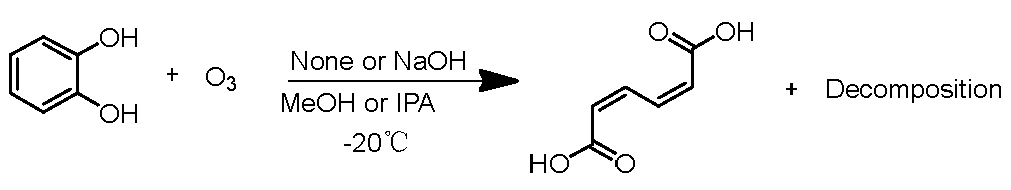

2.2. Decomposition Rate of Catechol by Ozone and Formation Rate of ccMA

Next, the decomposition rate of catechol and the production rate of ccMA were evaluated (

Scheme 3).

A 1.1 g (10 mmol) of catechol was added to a brown-colored flask. 100 mL of IPA or MeOH was added, dissolving the catechol. Either 1.2 g (30 mmol) of NaOH was added to the flask, or it was omitted, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 minutes. The flask was then placed in a cooling bath at −20°C and stirred for an additional 10 minutes. Oxygen gas containing 27 mg L−1 of ozone was bubbled into the flask at a rate of 1 L/min. During the reaction with ozone, the solution was stirred by a magnetic stirrer. After 15 minutes, the ozone generator was turned off, and bubbling with oxygen gas continued for 5 minutes at room temperature to remove any remaining ozone from the system. Distilled water was added to the reaction solution to dissolve any product precipitate and undissolved sodium hydroxide. The solution was diluted to 1 L in a measuring flask, further diluted 100-fold, and analyzed by an HPLC system. In the chromatogram, the peak areas at 257 nm and 277 nm at 2.8 minutes were calculated to determine the concentration of ccMA.

The results were listed in

Table 2. Along with differences of the solvent, differences due to the addition of granulated NaOH were also compared. The catechol concentration (%) is shown as a ratio to the starting concentration, while the ccMA percentage was determined as a ratio of the maximum ccMA production assumed from the initial moles of catechol. When comparing entries 1 and 3 (or 2 and 4), the decomposition rate of catechol was faster in MeOH than in IPA. The slower production rate of ccMA relative to the decomposition rate of catechol may be due to further oxidation of the ccMA by ozone. Comparing entries 1 and 2 (or 3 and 4) showed that the addition of NaOH leads to a more rapid decomposition of catechol. There are two possible reasons for this. One, the redox potential of catechol shifts to the negative side in alkaline solution, making it easily oxidized. Another, the chemical equilibrium was biased more toward the product side because the reaction products precipitated as ion pair, disodium muconate.

The addition of NaOH increased the ratio of ccMA to the amount of catechol decomposed. In this case, NaOH was added three times the moles of catechol. Therefore, NaOH did not completely dissolve at the beginning of the reaction, but gradually dissolved as ccMA was produced. When IPA was used as a solvent, the decomposition rate of catechol was slower but the conversion ratio to ccMA was higher. This was consistent with re-ports that muconic acid was formed at a faster rate in low dielectric constant solvents [

23]. It was believed that sodium salt of ccMA precipitate was more likely to form in IPA, which is more hydrophobic. Thus, undesirable oxidation of ccMA by ozone was prevented, and the oxidation of catechol proceeded more effectively.

2.3. Optimization of Reaction Conditions for ccMA Synthesis

The addition of a hydrophilic base to precipitate ccMA as ion-pair was found to be effective in preventing excessive oxidation of ccMA and improving yield. It was also found that IPA was more suitable for precipitation. Therefore, the type of base and the ozone concentration in the reaction solution were further examined (

Scheme 4).

An 11 g (0.1 mol) of catechol was weighed and transferred to a brown round-bottomed flask. 150 mL of IPA was added to the flask, and stirred with a magnetic stirrer to dissolve the catechol. 12 g (0.3 mol) of NaOH was added to the flask. The flask was stirred for 10 min at room temperature under light-shielded conditions, and the solution was cooled by setting the flask in a low-temperature thermostatic bath and stirred for an additional 10 min. Oxygen (standard condition) containing 27 mg L

−1 of ozone was bubbled into the flask at a rate of 1 L min

−1. During the reaction with ozone, the solution was stirred by a magnetic stirrer. After the reaction time, the ozone generator was turned off, and bubbling by oxygen gas continued for 5 min at room temperature to remove the remaining ozone gas from the reaction system. Distilled water was added to the reaction solution to dissolve the product precipitate and undissolved sodium hydroxide. The solution was diluted to 1 L in a measuring flask. This diluted solution was further diluted 100-fold, and the solution was analyzed by an HPLC system. In the chromatogram, the peak areas at 257 nm and 277 nm at 2.8 min were calculated for the determination of ccMA. Production efficiencies of ccMA under each condition are shown in

Table 3.

Measurements were taken every 3 hours until the catechol disappeared. From Entry 1-6, there was no change in yield for less than 6 hours, but the yield increased at lower temperatures after 9 hours. By decreasing the temperature to −40 °C, the ozone concentration was increased, but the reaction rate slowed down, so the decomposition of catechol was probably at the same level. The solubility of the disodium muconate was further decreased, suggesting that the ccMA was efficiently synthesized. Experiments using granular LiOH (particle size less than 0.7 mm) instead of NaOH were expected to yield higher efficiency due to the lower solubility of Li+ ion-pair formation, but the results were obtained with almost the same efficiency.

In addition, reactivity was examined when the flow rate of ozone was increased to 50 mg L−1 in order to increase the ozone concentration in the solution. From entries 7 to 9, increasing the ozone concentration to 50 mg L−1 increased the rate of ccMA formation over a reaction time of 3 hours, yielding 56% ccMA in 4.5 hours (entry 8). This was the highest yield in this study, and repeated experiments confirmed its reproducibility. The yield was decreased when the reaction time was lengthened to 6 h. This might be due to that decomposition of the suspension of disodium muconate was accelerated by the high concentration of ozone.

When the reaction was performed under the same conditions as in entry 8, but with 1-butanol as a solvent, the yield of ccMA was low at only 4.7%. This may be due to the low solubility of NaOH in 1-butanol, which made it difficult for the ionic pairs of ccMA to be suspended.

The product was obtained as a sodium salt of ccMA, but the acid form was easily obtained by precipitation with acid in aqueous solution. A ccMA in acid form was crystallized according to literature [

28] and

1H NMR spectrum was measured (see S7, S8).

3. Materials and Methods

Catechol, methanol, 2-propanol (IPA), ammonia solution, NaOH (granular, Special grade), lithium hydroxide monohydrate (Special grade), Formic Acid (LC/MS grade) and Acetonitrile (HPLC grade) were purchased from Fujifilm Wako Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan, used as received. A cis,cis-muconic acid (ccMA) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA.

The apparatus consisted of a 300 mL brown flask placed in a low-temperature thermostatic bath equipped with a magnetic stirrer (see page S2 in Supporting Information). The ozone generator used was a LOG-LC15G manufactured by Eco Design Corporation in Saitama, Japan (see S3). The solution was diluted and ccMA produced was determined by HPLC system (Waters Alliance 2695 Separations Module with PDA detector) based on the absorbance at 257 nm (ε = 17,300 for ccMA [

26]) (see S4). ODS separation column (Inert Sustain C18, 5 μm, GL Science, Tokyo, Japan) was used (see S5, S6). Reaction yields were determined by the concentration of ccMA and assuming a 1:1 molar ratio of formation from catechol.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have discovered a method to suppress the decomposition of ccMA produced in the catechol oxidation by ozone, and as a result, increasing the yield from the conventional about 30% to more than 50% have been succeeded. It was found that the addition of a hydrophilic base increases the rate of reaction between catechol and ozone and produces a suspension of the reaction product. This prevents the excessive decomposition of ccMA. The yield of ccMA depended on reaction conditions such as solvent, reaction temperature, and ozone concentration. Further research on improving reaction conditions for higher efficiency and industrial scale production methods are currently under investigation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Funding

This work was supported by JST SPRING, Grant Number JPMJSP2148.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Matthiesen, J. E.; Carraher, J. M.; Vasiliu, M.; Dixon, D. A.; Tes-sonnier, J.-P. Electrochemical Conversion of Muconic Acid to Bi-obased Diacid Monomers. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 3575–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averesch, N. J. H.; Krömer, J. O. Metabolic Engineering of the Shi-kimate Pathway for Production of Aromatics and Derived Com-pounds—Present and Future Strain Construction Strategies. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, Article–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carraher, J. M.; Pfennig, T.; Rao, R. G.; Shanks, B. H.; Tessonnier, J.P. cis,cis-Muconic Acid Isomerization and Catalytic Conversion to Biobased Cyclic-C6-1,4-Diacid Monomers. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 3042–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, I.; Quintens, G.; Junkers, T.; Dusselier, M. Muconic Acid Isomers as Platform Chemicals and Monomers in the Biobased Economy. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 1517–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draths, K. M.; Frost, J. W. Environmentally Compatible Synthesis of Adipic Acid from D-Glucose. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. T.; Kim, J. K.; Cha, H. G.; Kang, M. J.; Lee, H. S.; Khang, T. U.; Yun, E. J.; Lee, D.-H.; Song, B. K.; Park, S. J.; Joo, J. C.; Kim, K. H. Biological Valorization of Poly(ethylene terephthalate) Monomers for Upcycling Waste PET. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 19396–19406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Sun, X.; Yuan, Q.; Yan, Y. Extending Shikimate Pathway for the Production of Muconic Acid and its Precursor Salicylic Acid in Escherichia Coli. Metab. Eng. 2014, 23, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research and Markets. Global Muconic Acid Market by Derivative (Adipic Acid, Caprolactam), End-User (Agriculture, Chemicals, Food & Beverage) - Forecast 2024-2030. https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5890026/global-muconic-acid-market-derivative-adipic#src-pos-2 (accessed 2024-08-05).

- Maximize Market Research. Muconic Acid Market – Global Indus-try Analysis and Forecast (2024-2030). https://www.maximizemarketresearch.com/market-report/global-muconic-acid-market/55164/ (accessed 2024-08-05).

- Wang, G.; Tavares, A.; Schmitz, S.; França, L.; Almeida, H.; Caval-heiro, J.; Carolas, A.; Øzmerih, S.; Blank, L. M.; Ferreira, B. S.; Borodina, I. An Integrated Yeast-Based Process for cis,cis-Muconic Acid Production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2022, 119, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, R.; Noda, S.; Tanaka, T.; Kondo, A. Metabolic Engineering of Escherichia coli for Shikimate Pathway Derivative Production from Glucose–Xylose Co-Substrate. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Peabody, G. L.; Salvachúa, D.; Kim, Y.-M.; Kneucker, C. M.; Calvey, C. H.; Monninger, M. A.; Munoz, N. M.; Poirier, B. C.; Ramirez, K. J.; John, P. C. S.; Woodworth, S. P.; Magnuson, J. K.; B.Johnson, K. E.; Guss, A. M.; Johnson, C. W.; Beckham, G. T. Muconic Acid Production from Glucose and Xylose in Pseudomo-nas putida via Evolution and Metabolic Engineering. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4925. [CrossRef]

- Vardon, D. R.; Rorrer, N. A.; Salvachúa, D.; Settle, A. E.; Johnson, C. W.; Menart, M. J.; Cleveland, N. S.; Ciesielski, P. N.; Steirer, K. X.; Dorgan, J. R.; Beckham, G. T. cis,cis-Muconic Acid: Separation and Catalysis to Bio-Adipic Acid for Nylon-6,6 Polymerization. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 3397–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonoki, T.; Takahashi, K.; Sugita, H.; Hatamura, M.; Azuma, Y.; Sato, T.; Suzuki, S.; Kamimura, N.; Masai, E. Glucose-Free cis,cis-Muconic Acid Production via New Metabolic Designs Correspond-ing to the Heterogeneity of Lignin. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupé, F.; Petitjean, L.; Anastas, P. T.; Caijo, F.; Escande, V.; Darcel, C. Sustainable Oxidative Cleavage of Catechols for the Synthesis of Muconic Acid and Muconolactones Including Lignin Upgrading. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 6204–6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, P. C.; Sankaran, D. K. Muconic Acid. Org. Synth. 1946, 26, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankston, D. Oxidative Cleavage of an Aromatic Ring: cis,cis-Monomethyl Muconate from 1,2-Dihydroxybenzene. Org. Synth. 1988, 66, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooti, M.; Jorfi, M. Mild and Efficient Oxidation of Aromatic Alco-hols and Other Substrates Using NiO2/CH3COOH System. J. of Chem. 2008, 5, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ornum, S. G.; Champeau, R. M.; Pariza, R. Ozonolysis Applica-tions in Drug Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 2990–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siggel, E.; Spengler, G. Verfahren zur Herstellung von cis-cis-Muconsaeure und deren Derivaten. DE 870 096 B, 1953.

- Siggel, E.; Spengler, G. Verfahren zur Gewinnung von cis-cis-Muconsaeure und ihren Homologen. DE 814 740 B, 1951.

- Wingard, L. B., Jr.; Finn, R. K. Oxidation of Catechol to cis,cis-Muconic Acid with Ozone. Prod. R&D 1969, 8, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rudie, A. W.; Hart, P. W. Understanding the Risks and Rewards of Using 50% vs. 10% Strength Peroxide in Pulp Bleach Plants. Tappi J. 2018, 17, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, E. Reaction of Ozone with trans,trans-Muconic Acid in Aqueous Solution. Water Res. 1980, 14, 1637–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillar-Little, E. A.; Camm, R. C.; Guzman, M. I. Catechol Oxidation by Ozone and Hydroxyl Radicals at the Air−Water Interface. Envi-ron. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 14352–14360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistrom, W. R.; Stanier, R. Y. The Mechanism of Formation of β-Ketoadipic Acid by Bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 1954, 210, 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, P. S. The Reactions of Ozone with Organic Compounds. Chem. Rev. 1958, 58, 925–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, D.; Wu, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, J.; Su, Z. One Step Recovery of Succinic Acid from Fermentation Broths by Crys-tallization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010; 72, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Scheme 1.

(a) Synthesis of trans,trans-muconic acid (ttMA) via a condensation reaction, (b) synthesis of cis,cis-muconic acid (ccMA) by oxidative cleavage of catechol with peracids, (c) synthesis of ccMA from catechol oxidation by ozone, and (d) synthesis of ccMA from catechol oxidation by ozone in the presence of a hydrophilic base.

Scheme 1.

(a) Synthesis of trans,trans-muconic acid (ttMA) via a condensation reaction, (b) synthesis of cis,cis-muconic acid (ccMA) by oxidative cleavage of catechol with peracids, (c) synthesis of ccMA from catechol oxidation by ozone, and (d) synthesis of ccMA from catechol oxidation by ozone in the presence of a hydrophilic base.

Scheme 2.

Reaction of ccMA with ozone in alcohol.

Scheme 2.

Reaction of ccMA with ozone in alcohol.

Scheme 3.

Reaction of muconic acid in alcohol with ozone.

Scheme 3.

Reaction of muconic acid in alcohol with ozone.

Scheme 4.

Preparation of ccMA.

Scheme 4.

Preparation of ccMA.

Table 1.

Decomposition of ccMA by ozone.

Table 1.

Decomposition of ccMA by ozone.

| Entry |

base |

temp./ °C |

Solvent |

time / h |

ccMA remaining (%) |

| 1 |

None |

−20 |

IPA |

1 |

36 |

| 2 |

NaOH |

−20 |

IPA |

1 |

92 |

| 3 |

None |

−20 |

MeOH |

1 |

2.0 |

| 4 |

NaOH |

−20 |

MeOH |

1 |

92 |

Table 2.

Decomposition rate of catechol by ozone and formation rate of ccMA.

Table 2.

Decomposition rate of catechol by ozone and formation rate of ccMA.

| Entry |

base |

temp./ °C |

Solvent |

time / min |

Yield(%) |

| 1 |

None |

−20 |

IPA |

15 |

0.38 |

| 2 |

NaOH |

−20 |

IPA |

15 |

15 |

| 3 |

None |

−20 |

MeOH |

15 |

0.73 |

| 4 |

NaOH |

−20 |

MeOH |

15 |

15 |

Table 3.

Reaction yields of catechol oxidation by ozone at different reaction temperatures in the presence of various hydrophilic bases.

Table 3.

Reaction yields of catechol oxidation by ozone at different reaction temperatures in the presence of various hydrophilic bases.

| Entry |

base |

temp./ °C |

Ozone Conc.

/ mg L-1

|

time / h |

Yield(%) |

| 1 |

NaOH |

−20 |

27 |

3 |

24 |

| 2 |

NaOH |

−20 |

27 |

6 |

26 |

| 3 |

NaOH |

−20 |

27 |

9 |

22 |

| 4 |

NaOH |

−40 |

27 |

3 |

23 |

| 5 |

NaOH |

−40 |

27 |

6 |

28 |

| 6 |

NaOH |

−40 |

27 |

9 |

37 |

| 7 |

NaOH |

−40 |

50 |

3 |

25 |

| 8 |

NaOH |

−40 |

50 |

4.5 |

56a

|

| 9 |

NaOH |

−40 |

50 |

6 |

33 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).