1. Introduction

The world's population increasingly needs food products that not only provide nutritional value, but also contribute to improved health, reduced disease and increased life expectancy ([

1]; Baslam et al., 2013). Research from the Cancer Institute has shown a correlation between increased vegetable consumption and a reduced risk of chronic diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and age-related decline in activity in older adults ([

2,

3]; Hung et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2018). Micronutrient deficiencies are a major global public health problem in many countries, with some authors noting that infants and pregnant women are particularly at risk of not receiving essential nutrients ([

2,

4]; Hung et al., 2004; Soetan et al., 2010). Particular attention should be paid to the nutrition of children, since sufficient amounts of macro- and micronutrients are necessary for their full development. It is believed that these health-promoting compounds are associated with adequate intake of macronutrients and bioactive compounds present in vegetables. Several studies have found that fruits and vegetables are rich sources of antioxidant nutrients and bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, which are involved in neurodegenerative processes ([

5]; Huot, 2014). Dietary intake of vitamins E and C for 3 years maintains cognitive abilities and slows down their deterioration. It has been found that levels of vitamin E in food and human blood plasma can reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease (AD). Dietary intake of vitamin C, carotenoids, and flavonoids also reduces the risk of AD. Dietary intake of flavonoids provides a 50% reduction in the risk of dementia ([

2,

6]; Hung et al., 2004; Shi et al., 2022).

Lettuce is one of the most well-known leafy vegetables in the world, with many uses in both cooking and science. In addition, lettuce is an excellent source of bioactive compounds such as polyphenols, carotenoids and chlorophyll with associated benefits for human health ([

3]; Kim et al., 2018). There are many different varieties of lettuce, with colors ranging from green and yellow to deep red, which is due to the different concentrations of chlorophyll and anthocyanins in the leaves ([

7,

8]; Mou, 2005; López et al., 2014).

Lettuce (

Lactuca sativa L., family Asteraceae) is one of the most popular vegetables, consumed fresh or in salad mixtures and has high production and economic value ([

9,

10]; Mampholo et al., 2016; Das et al., 2024). The crop is unpretentious and can be grown both in open and closed ground. In addition, lettuce can be grown in various traditional ways on soil and soilless methods in containers or on vertical rack systems ([

11]; Assefa et al., 2021). Consumer interest in lettuce is growing due to its superior visual quality, low calorie content, low disease incidence, and high content of beneficial phytochemicals. According to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations ([

12]; Mekouar, 2023), the production of lettuce in the world increases annually, while it is noted that the main supplier is China (~56%), and in second and third place are the United States (~12%) and India (~4.3%), respectively. Cultivated lettuces come in different types, and can differ in the shape and size of the stalk, stem, and can form different heads: oily, crispy (iceberg or cabbage).

The nutritional or nutraceutical properties of lettuce vary depending on growing conditions and abiotic factors. However, a number of studies show that the variety, i.e. its genetic makeup, also greatly influences the properties of lettuce. For example, romaine and leaf lettuce varieties contain higher amounts of ascorbic acid, vitamin A, carotenoids, and folate, while crispheads contain relatively low amounts of these compounds ([

11]; Assefa et al., 2021). Differences in the content of primary and secondary metabolites in red and green lettuce leaves were observed between head and leaf types of lettuce ([

13]; Altunkaya et al., 2009). In addition to growing conditions, genetic variation influences the nutritional and phytochemical properties of lettuce ([

3]; Kim et al., 2018).

Anthocyanins are a family of naturally occurring flavonoids responsible for variations in the color of leaves, fruits, and flowers of many plants, particularly the red, purple, and bluish colors of lettuce ([

10]; Das et al., 2024). Red pigmented lettuce accumulates large amounts of anthocyanins. Anthocyanins are typically present in the form of anthocyanidin glycosides and acylated anthocyanins (

Figure 1) ([

13]; Altunkaya et al., 2009).

Anthocyanin pigments extracted from plants have been traditionally used as dyes and food colorings to treat various diseases ([

14]; Khoo et al., 2017). The most common anthocyanidins in nature are pelargonidin, cyanidin, delphinidin, peonidin, petunidin, and malvidin. Hydroxylation and methylation of the B-ring control the color and stability of anthocyanins.

Table 1 lists most of the anthocyanidins and other coloring substances that contribute to the increase in red color under the influence of abiotic factors. Blueness increases with the increase in the number of hydroxyl groups, while redness increases with the increase in methylation in the B-ring ([

15,

16]; Alappat and Alappat, 2020; Anum et al., 2024).

There are many studies confirming the fact that anthocyanins participate in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases and have shown a connection between the level of anthocyanins in lettuce and the manifestation of antioxidant, antidiabetic, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antitumor, antimutagenic effects ([

1,

19,

20,

21]; Baslam et al., 2013; Petroni and Tonelli, 2011; Morais et al., 2016; Giampieri et al., 2023). However, quantitative data on the main health-promoting metabolites of red pigmented lettuce are clearly lacking.

It was found in early studies that red lettuce had higher total anthocyanin and phenolic content and antioxidant capacity than green lettuce ([

22,

23,

24]; Ferreres et al., 1997; Stintzing et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2005). The main difference between red and green lettuce was the anthocyanin content. Mulabagal et al. ([

25]; 2010) compared

in vitro biological activity of green and red lettuce and showed that the aqueous extract of red lettuce has a higher biological activity and contains more anthocyanins compared to green varieties. In addition, the presence of only one major anthocyanin was shown by HPLC analysis of the red lettuce extract, and it was characterized as cyanidin-3-O-6-malonyl-β- glucopyranoside. Subsequent glycosylation results in a red shift in the color of the anthocyanin with increased stability. While 3-glycosides increase stability, 5-glycosides tend to decrease stability. Moreover, attachment of 5-glycosides to anthocyanidin can also lead to the formation of colorless pseudobases since the loss of the hydroxyl group at position 5 makes the anthocyanin more susceptible to hydration reaction. Sugar residues in anthocyanins are often acylated with aromatic or aliphatic acids. Common aliphatic and aromatic acids involved in acylation reactions result in color changes (blue shift) and increased stability due to intra- and intermolecular copigmentation reactions. In addition to the biosynthetic genes involved in anthocyanin pigment formation, vacuolar pH and cell shape have a negative effect on anthocyanin pigments. For example, in petunia flowers, acidification of the vacuole causes a red color change, while mutations affecting pH result in a blue color change. Even with high pigment accumulation, plants may appear colorless due to the shape of their cells. This is due to differences in reflected light between conical and flat cells ([

26]; Grotewold, 2006).

It was found that the variety, agricultural practices and growing conditions can change the content of phytocomponents, leaf color and quality of lettuce ([

27,

28]; Liu and Yang, 2012; Tsormpatsidis et al., 2008). The diversity of physiological characteristics of lettuce tissues, pigment forms and the characteristics of their distribution in cells contribute to the fact that phytochemicals and the antioxidant capacity of a given crop can differ even in the outer and inner leaves of plants. Thus, it was found in ([

29]; Viacava et al., 2014) that total soluble solids (TSS) and color values of green and red lettuce cultivars were significantly dependent on leaf position on the plant: internal leaves showed significantly higher levels of PTB than average, and the outer leaves of lettuce are both red and green. The average RTV content in green varieties was significantly higher than that of red varieties. The color of the leaves can also vary depending on their position for each lettuce variety, which occurs as a result of the breakdown of chlorophyll and the accumulation of anthocyanins: the values indicating the lightness of the color gradually decreased from the inner to the outer leaf. Similar patterns were recorded for the indices indicating

the color when the leaf color changes from green to red: the outer leaves of green varieties showed lower (more negative) values due to high chlorophyll content with a darker green color, while the outer leaves of red varieties showed higher values of this indicator due to the increased content of anthocyanins with a red color.

The influence of leaf position on antioxidant activity was demonstrated for the first time in ([

30]; Ozgen and Sekerci, 2011). The nutrient content of several anthocyanin-rich red and green lettuce varieties was compared and quantified: green and red lettuce varieties showed different characteristics, mainly due to the presence of anthocyanins in red varieties. It was shown that in red lettuce leaves, the outer leaves have the highest content of phytonutrients and antioxidant properties. The results of the studies have practical and scientific value, including the use of the identified patterns in drawing up breeding programs aimed at creating new varieties and developing functional human nutrition systems, as well as for the pharmaceutical industry.

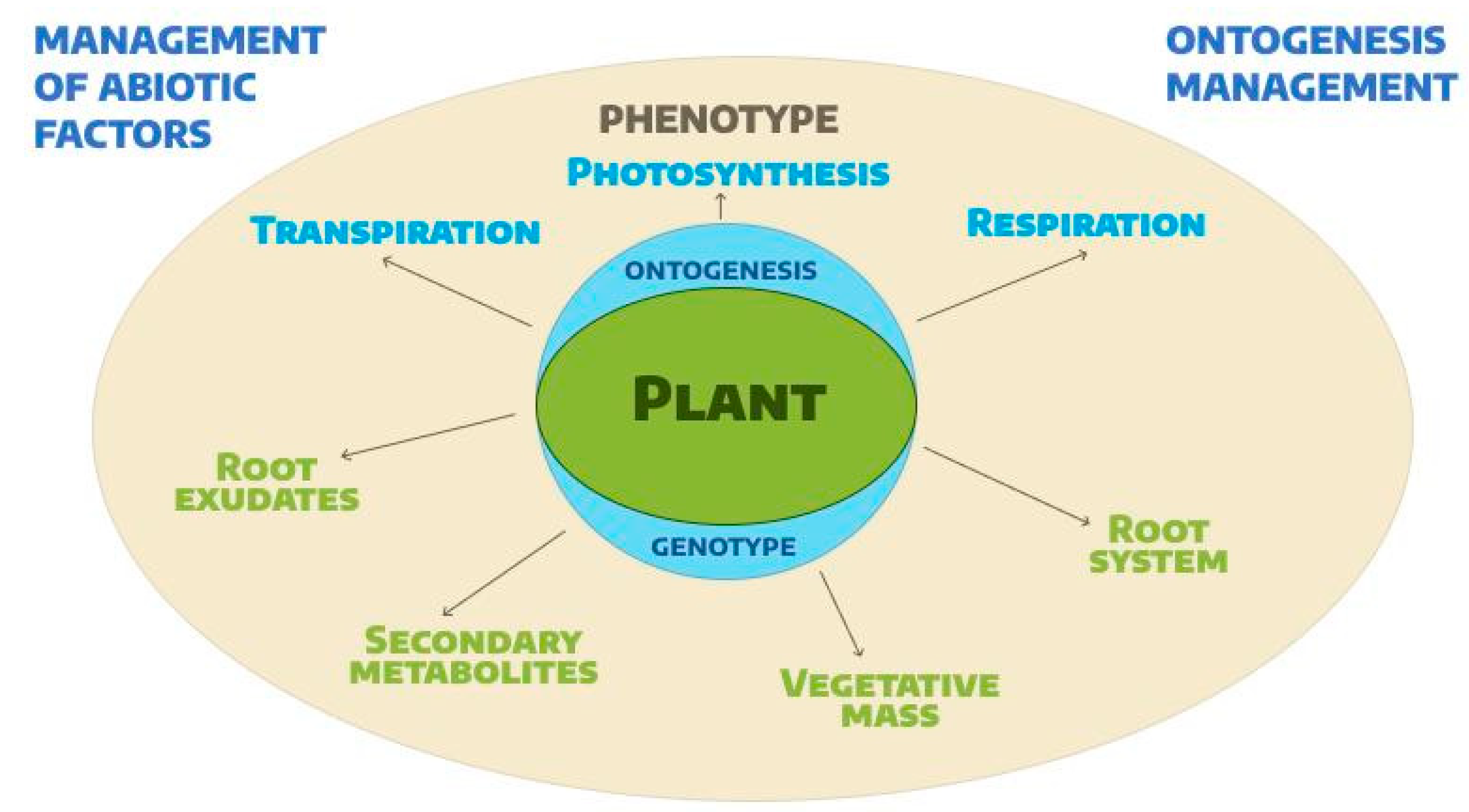

Thus, the food significance and nutritional value of red-leaved plants have been identified and studied quite well. The results of a number of studies ([

9,

16,

31,

32,

33]; Mampholo et al., 2016; Anum et al. 2024; Liang et al., 2024; Bunning et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2007) are schematically generalized in

Figure 2, which shows that the individual development of each separate species or variety of lettuce is determined by the genetic characteristics of the individual, which are manifested in the activity of the main biological processes of plants - respiration, photosynthesis, transpiration, metabolic processes and accumulation of nutrients in tissues and different parts of the plant. In addition, all processes are also under the influence of abiotic and biotic factors that determine their growth and development, the change of phenophases, the rate of seed maturation, and the quality of plant products for various purposes.

2. The Influence of Light on Leaf Color and Antioxidant Activity of Lettuce

It is known that light controls photosynthesis and regulates the morphology, physiology and phytochemical composition of plants. Plants use light as an energy source for photosynthesis, signaling and many other fundamental processes; therefore, primary and secondary metabolism are regulated by the quantity and quality of light entering the leaf blade ([

10]; Das et al., 2024).

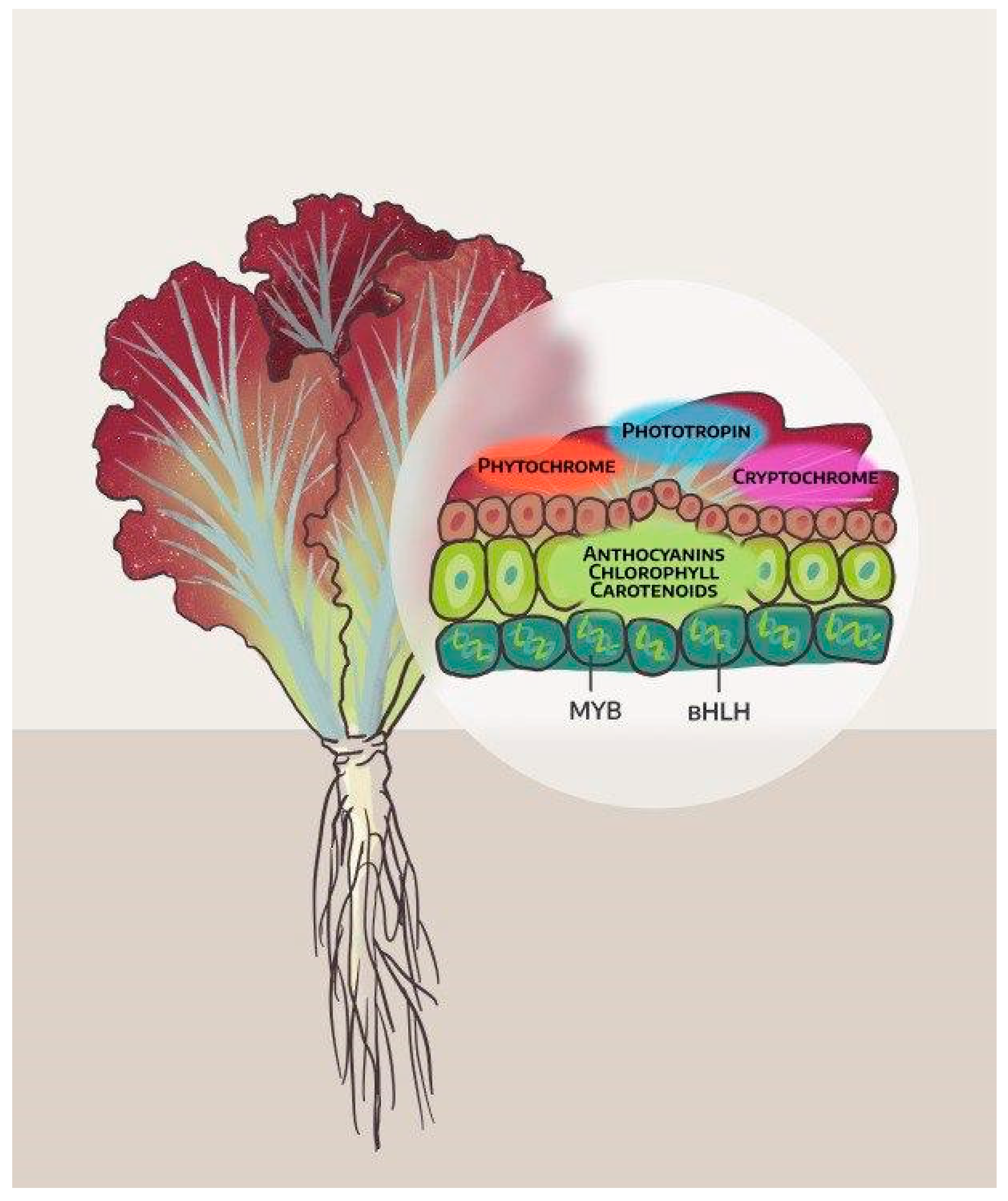

According to modern concepts, plants have at least five groups of photoreceptors that perceive information not only about lighting conditions and daylight hours, but also about ambient temperature, the presence of pathogens or competing neighbors, the direction of the gravity vector, and other factors ([

34,

35]; Pierik and de Wit, 2014; Lee et al., 2016). These receptors include red (RL) and far red (FRL) receptors – phytochromes; receptors that perceive ultraviolet A radiation, blue (BL) and green (GG) light – cryptochromes, phototropins, proteins of the ZEITLUPE family; as well as a receptor for ultraviolet B radiation (UVB) – the UVR8 protein ([

36]; Briggs and Christie, 2002).

Using light-emitting diodes (LEDs), it is possible to create individual spectra, including a spectrum simulating sunlight, which allows for significant changes in the course of ontogenesis, growth and development of crops. Considering the fact that the spectrum of light can influence the physiological reactions of plants, it is already possible today to influence different stages of plant growth by means of several “fixed” spectra, which makes it possible for dynamic spectral manipulation, including changes in the mechanisms of functioning of light recipes throughout the growth cycle of lettuce

Figure 3.

As has been established previously and confirmed by modern methods, plants use photosynthetic pigments in their leaves to capture the photosynthetic active radiation (PAR) to initiate the synthesis of sugar molecules. These photosynthetic pigments are present around the thylakoid membranes of chloroplasts and serve as the primary electron donors in the electron transport chain ([

37]; Anderson, 1986). Specifically, photosynthetic pigments absorb light and transfer energy via resonance energy transfer to a specific chlorophyll pair in the reaction center of photosystem II P680 or photosystem I P700. In this light-dependent reaction, water molecules are broken down to generate ATP and NADPH and release oxygen molecules as a byproduct. It has been established that in a subsequent light-independent reaction in the chloroplast stroma, the energy from ATP and electrons from NADPH are used to convert carbon dioxide into glucose and other products via the Calvin cycle.

In ([

27,

38]; Liu and Yang, 2012; Spalholz et al., 2020) the results of studies on the assessment of growth, development and phytochemical composition of green red and green crops grown hydroponically under different exposition spectra are presented. One of spectra simulated the sun (SUN), and six others were conventional light spectra used in indoor growing systems: 5% ultraviolet-A (UV-A), 20% blue (B), 26% green (G), 26% red (R), and 23% far-red (FR) light as percentage photon flux density (PFD). Fluorescent white light (FL - 6500 K) was used as a control. Plants received 200 ± 0.7 μmol m

-2 s

-1 of biologically active radiation (300-800 nm) for 18 h and were grown at a temperature of 20.0 ± 0.2 °C. The results indicate that the dry mass of plants under SUN treatment was not significantly different from that under red-blue light treatment at all harvest times: the dry mass of plants at day 17, the leaf area of lettuce grown under B+R conditions was 15–39% larger than that of those grown under blue and fluorescent white. The leaf area at day 42 was 39–78% larger in the 100B, SUN, and FL treatments than in the B+R treatment. The increase influence of LED-simulated solar resulted in bolting and flowering of lettuce in the SUN treatment. In addition, the authors noted that both total phenolic and anthocyanin concentrations in lettuce leaves were higher in the B+R treatments than in the SUN, 100R, and 100B treatments. These studies further confirm the basic information on lettuce responses to LED-simulated solar spectrum compared to conventional B+R treatments and provide insight into lettuce growth change and morphology under different spectra.

As the authors note, amid the flood of studies on the effects of light spectra on lettuce growth, photoperiod is a relatively unexplored parameter in studies determining the effect of lighting on indoor leafy greens. This is likely due to the less pronounced effect of photoperiod on growth and nutrient accumulation in leaves compared to the quality and quantity of light received by the plant. It is noted that photoperiods of 14–18 hours of illumination are usually used when growing green crops, which is already an optimal level. Thus, any deviation from this established norm does not bring significant benefits during the vegetative growth of leafy greens. Despite the fact that all tested daylight integrals are only a fraction of full sunlight, leafy greens grow well in these so-called low-light conditions. Yudina et al. ([

39]; 2023) developed a model to predict plant productivity to answer the question: does increasing light duration stimulate plant productivity without causing changes in photosynthesis and respiration. The results of the study showed that increasing light duration can stimulate dry weight accumulation and that this effect can also be caused by increasing the photoperiod with decreasing light intensity. Therefore, the authors showed that increasing light duration is an effective approach to stimulating lettuce production under artificial lighting.

As shown by the above studies, higher illumination can lead to higher biomass, but phytonutrient accumulation can be active at lower illumination. Furthermore, electric lighting can represent a significant portion of production costs, and therefore there is little incentive to use high PPFD or long photoperiod in a closed production agroecosystem to make such a system economically viable and environmentally sustainable ([

10,

40]; Das et al., 2024; Wong et al., 2020).

Every year, more and more research is being conducted in the field of photobiology and photomorphogenesis, but the answer to the question of producers by what mechanisms to obtain a redder or greener lettuce that would simultaneously have increased antioxidant capacity and nutritional value for the consumer has not been received. A number of authors (e.g., [

28,

41]; Tsormpatsidis et al., 2008; Samuolienė et al., 2011) noted that plant growth, including lettuce, occurs as a result of biomass accumulation following the trajectory of a sigmoid curve. The choice of the plant growth stage for experiments with the light spectrum can significantly affect the reaction, and vice versa, the light spectrum can be used to create the desired morphological characteristics. Lettuce seedlings should be compact plants with a good root system and a large leaf mass area. After rooting of the seedlings, when treated with light emitters, rapid leaf growth occurs to increase light capture ([

16]; Anum et al., 2024).

Low light intensity affects the dormancy of the anthocyanin pathway in red-leaf lettuces, and conversely, high light intensity enhances the expression of genes associated with anthocyanin biosynthesis, including regulatory genes (

PAP1 and

PAP2) and structural genes (

CHS, F3H, DFR, and

LDOX). The accumulation of anthocyanins was negatively affected by switching from fluorescent to LED lighting: the molecules decreased under white and red-blue LED illumination. Red light and UV-C radiation can inhibit the accumulation of anthocyanins or cause their degradation. At the same time, studies have shown that both blue and red light effectively stimulate the formation of anthocyanins in strawberry fruits ([

42,

43]; Inoue and Kinoshita, 2017; Fylladitakis, 2023).

Thus, lettuce responds positively to changes in the light spectrum and photoperiod, and it is noted that due to these parameters it is possible to change not only the aboveground biomass and morphometry, but also agronomically important traits, such as dry matter, the content of photosynthetic pigments, primarily anthocyanins, and antioxidant activity. In lettuce grown at an increased level of irradiation in the range from 250 to 300 μmol /m

2, an increase in the concentration of anthocyanins was obtained ([

28,

44]; Tsormpatsidis et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2018). The effect of spectrum on growth and taste depends on the lettuce variety. By using only red light, it is possible to control the absorption of nutrients, and therefore the quality and taste of the grown produce. Using wavelengths of light emitters in the range from 620 nm to 700 nm has several positive effects on the nutritional value of lettuce: the concentration of ascorbic acid decreases, antioxidant properties increase, and the absorption of N, K, Ca and Mg by the plant root system is stimulated, which immediately affects the accumulation of sugars and other components. Both far-red and blue LEDs have promising prospects for use as supplemental lighting and for controlling quality and growth. However, the influence of lettuce varietal characteristics on the efficiency of anthocyanin and other nutrient synthesis under modified artificial lighting conditions remains poorly understood ([

16]; Anum et al. 2024), which means that studying the effect of photon flux density on the accumulation of anthocyanins is very promising and useful.

3. Effect of Temperature on Leaf Color and Antioxidant Activity of Lettuce

Plant growth and development are influenced by various environmental factors, including light, temperature, CO

2, water availability, and pathogens. External, environmental factors often trigger abiotic and biotic stress responses in plants, including the production of secondary metabolites, which play a key role in stress tolerance. However, additional production of secondary metabolites requires energy expenditure for synthetic processes, and these costs can lead to a decrease in plant growth and development ([

11]; Assefa et al., 2021). Mutant plants responding to constitutive biotic stress showed a smaller size and weight of aboveground biomass due to the activation of adaptation reactions and resistance development through the synthesis of salicylic acid, including the production of antimicrobial secondary metabolites ([

45]; Blokhina et al., 2003). This process is very important in the development of mechanisms for controlling plant growth processes and color. Accordingly, to increase the production of metabolites by a plant through responses to the environment, it is necessary to take into account most of the abiotic factors that affect plant growth and development, one of which is the ambient temperature of both roots and aboveground biomass. It was found that the optimal temperature for anthocyanin biosynthesis is in the range of 15-30 C°. However, plants can actively synthesize anthocyanins at lower and higher temperatures. For example, under low-temperature stress (4 C°) regulation of the expression of

FaMYB10 and

FaMYB1 genes was noted, which significantly increased the activity of structural genes and led to increased accumulation of anthocyanins in strawberry leaves ([

16,

46]; Anum et al., 2024; Noda et al., 1994).

Analyzing the data obtained by a number of scientists, it is possible to identify another mechanism for regulating the growth and amount of plant pigments, and minimizing crop losses - by changing the temperature of the root zone of plants (RZT) at different stages of their growth. This suggests that RZT control may be a relevant method, especially in vertical farms and greenhouse complexes where flood tables or a flooding system are used. For instance, Levine et al. ([

47]; 2023) showed that exposure of red lettuce roots to low temperature significantly reduced leaf area, stem diameter, and above- and below-ground fresh weight. The results suggest that low-temperature root treatment triggers stress responses throughout the plant, resulting in reduced leaf and root growth.

However, in another study, heating the root zone by heating the solution in the root zone did not result in significant changes in plant biomass ([

48]; He et al., 2013) Cooling the root zone to 20˚C increased the biomass of aeroponic lettuce compared to plants under ambient conditions (24–38˚C) in a tropical greenhouse ([

49]; Paulsen, 1994).

The production of various plant metabolites is influenced by root zone temperature in many plants. Studies conducted in ([

47,

50]; Levine et al., 2023; Porter and Gawith, 1997) showed that human-preferred compounds, such as anthocyanin, phenolics, and sugars, increased significantly in red lettuce leaves when their roots were exposed to low temperature. Sugar accumulation was observed in spinach, cotton, and tomato when roots were exposed to low temperature. In contrast, exposure of roots to high temperature did not change the anthocyanin, phenolics, and sugars in leaves. However, increasing soil temperature using electric heating cables suppressed anthocyanin and sugar accumulation in lettuce leaves under field experimental conditions.

Root stress such as drought or salinity causes plant growth limitation followed by a reduction in leaf photosynthetic capacity (see Box 1 in [

51]; Allen and Ort, 2001). Reduced plant growth and photosynthesis were observed when plants were exposed to low root temperatures ([

52,

53]; Akula and Ravishankar, 2011; Bumgarner et al., 2012). Low root temperature treatment resulted in decreased water uptake by lettuce, which resulted in a reduction in photosynthesis in the shoot growth zones. However, sugar content in both lettuce leaves and roots increased following low root temperature treatment, while nitrate concentrations, for example, changed significantly only in leaves where the temperature was reduced to 40% of that in plants under ambient conditions. Considering that photosynthetic nitrate uptake is likely not increased in leaves due to low root temperature stress, the suppression of nitrate transport from roots to leaves may be responsible for the decrease in nitrate concentration in the leaves themselves ([

48]; He et al., 2013).

RZT can also significantly affect the plant metabolite contents in both leaves and roots ([

53]; Bumgarner 2011). Comparing the results obtained in an experiment on lettuce whose root system was maintained at a solution temperature of 25 °C, the concentrations of 19 amino acids (isoleucine, serine, tyrosine, valine, methionine, leucine, cysteine, phenylalanine, threonine, homoserine, histidine, pyroglutamate, alanine, glutamate, glutamine, ornithine, glycine, β-alanine, and asparagine) were significantly increased in the roots under the 15 °C treatment. At the same time, the morphometry of the leaves was not significantly changed. In contrast, compared with the 25 °C treatment, the 35 °C treatment significantly affected the metabolite contents in both roots and leaves. The roots showed significant increases in seven sugars (glucose, fructose, sucrose, turanose, lactose, ribose, and maltose), 21 amino acids (arginine, phenylalanine, lysine, glycine, histidine, proline, cysteine, isoleucine, threonine, tyrosine, glutamine, valine, asparagine, pyroglutamate, β-alanine, 3-cyanoalanine, leucine, tryptophan, ornithine, serine, and methionine), and five metabolites in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) (isocitric acid, 2-xoglutaric acid, citric acid, fumaric acid, and malic acid).

In

Arabidopsis, overexpression of a plasma membrane water channel protein mitigated the low root temperature-induced decline in hydraulic activity and plant growth, suggesting a role for water uptake in root temperature stress. Since drought stress triggers various secondary metabolic pathways, the accumulation of anthocyanins, phenolics, and sugar in leaves in the experiment may be a response to drought stress: a study in green crops showed that drought stress applied to roots can lead to accumulation of phenolics and sugar in hydroponically grown lettuce seedlings ([

54,

55]; Park et al., 2008; Boo et al., 2011).

It was noted in ([

32,

47]; Bunning et al., 2019; Levine et al., 2023) that photosynthesis impairment caused by abiotic stress often accompanies oxidative stress. Plants exposed to drought, salinity, and low temperature experience oxidative stress, which is followed by a decrease in photosynthetic capacity and oxygen emission, which is associated with the functioning of cofactors in photosystem II (PSII), and as a consequence, this leads to limitation of plant biomass production. Salinity stress induces oxidative stress in leaves, such as the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), activation of antioxidant enzymes, and leaf chlorosis. As shown in ([

56]; Rivas -San Vicente, 2011), low-temperature treatment of lettuce roots causes the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide in leaves, accompanied by lipid peroxidation. This finding indicated that low-temperature stress in the root zone induces oxidative stress in leaves, presumably by limiting photosynthesis. Plants cope with oxidative stress by producing antioxidant metabolites, including phenolic compounds such as anthocyanin. As a result of stress, anthocyanin and phenolic content in leaves increases when roots are exposed to low temperature, indicating an antioxidant role for these metabolites in response to elevated hydrogen peroxide levels in leaves.

It was found that lettuce exposed to low air temperature at a level of 10-15 degrees showed increased production of anthocyanins and polyphenols, which led to a change in the intense color of lettuce leaves, and also showed an increased ability to remove DPPH radicals. The

Arabidopsis MYB transcription factor AtMYB60 functions as a transcriptional repressor of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes in lettuce ([

32]; Bunning et al., 2019). Given that MYB family proteins are common regulators of the anthocyanin synthesis pathway in many plants ([

57]; Chadwick et al., 2024), anthocyanin accumulation in lettuce leaves induced by low root zone temperature is also regulated by intrinsic MYB transcription factors. To enhance the levels of secondary metabolites, regulation of these transcription factors may be important for the production of crops with improved product quality.

It was shown in ([

58,

59]; Takahashi and Murata, 2008; Sairam et al., 2020) that treatment with a solution with a high RZT contributed to the improvement of pigment content, but negatively affected plant growth. In this experiment, plants were grown in five temperature variants of RZT: 25 °C; HT1 (12 days at 25 °C, then 4 days at 35 °C); HT2 (8 days at 25 °C, then 8 days at 35 °C); HT3 (4 days at 25 °C, then 8 days at 35 °C); and 35 °C at an air temperature of 22 °C. It was observed that an increase in the duration of RZT treatment at 35 °C led to a decrease in the dry weight of shoots and roots, and an increase in the content of chlorophyll, carotenoids, and anthocyanins. In addition, the chlorophyll content increased significantly when treated with RZT at 35 °C for more than 4 days, while the carotenoid and anthocyanin contents increased significantly when treated with RZT at 35 °C for more than 8 days. It was also found that RZT treatment at 35 °C compared with 25 °C limited plant growth in roots and leaves due to decreased root growth, but increased the pigment contents including anthocyanin, chlorophyll, and carotenoids. This was probably due to the typical response to heat stress. The longer the period of exposure of the root zone to high temperature (35 °C), the more the anthocyanin, carotenoid and chlorophyll contents increased, while the shoot dry weight decreased, indicating gradual plant mortality before harvest. However, increasing the pigment levels may be an effective mechanism for controlling leaf color in lettuce. Plants typically accumulate ROS under stressful conditions, and plant stress tolerance is often associated with increased activity of antioxidant enzymes. The increase in anthocyanins and carotenoids in leaves at RZT 35 °C is due to the formation of ROS in leaves as a response to high-temperature stress and an increase in antioxidants to remove them.

In addition, the authors noted that carotenoids are produced from β-alanine via acetyl- CoA, but the leaves of plants in the 35 °C experiment were enriched in β-alanine, and it is possible that β-alanine metabolism influenced carotenoid accumulation. The root zone temperature significantly affected the concentrations of elements in both leaves and roots. Compared with the 25 °C treatment, plants in the 15 °C treatment experienced a significant decrease in Ca, Mn, As, and Cd in the roots, with a significant increase in P, K, Li, and Rb and a significant decrease in Cu and Cs in the leaves. Compared with the 25 °C treatment, the 35 °C treatment resulted in a significant increase in Fe, Zn, Mo, Cu, Ni, Co, Li, Se, and Cd and a significant decrease in Ca, S, Mn, As, and Sr in the roots. Simultaneously with 35 °C treatment, there was a significant decrease in P, K, Ca, Mg, S, Fe, Mn, Zn, Mo, Cu, Na, Ge, As, Se, Rb, Sr, and Cs in the leaves.

In summary, low and high temperatures in the root zone limit plant growth through various internal mechanisms, and growing at high temperatures in the root zone 4 days before harvesting can slightly reduce the production process, but lead to the accumulation of pigments, which in turn contributes to an increase in the added value of lettuce and color. However, in general, this direction and its practical application remain poorly understood and should be more studied.

4. Effect of pH on Leaf Color and Antioxidant Activity of Lettuce

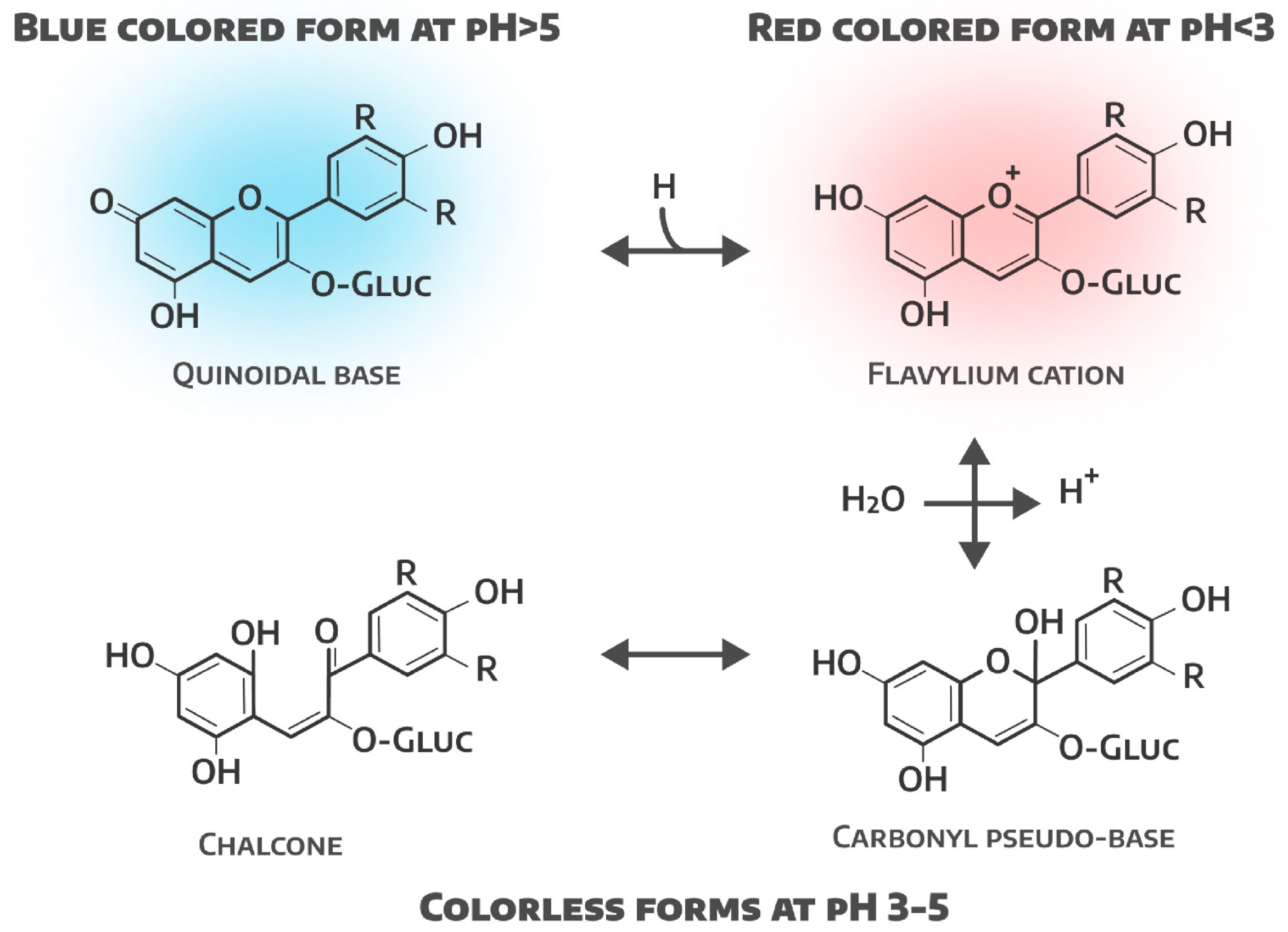

Anthocyanins are potent antioxidants in plants and maintain optimal cellular redox equilibrium by neutralizing free radicals with their hydroxyl groups to reduce oxidative damage ([

60]; Naing and Kim, 2021). Anthocyanins are derived from anthocyanidins, which are structurally based on the flavylium ion (2-phenylchromenylium). This flavylium ion is responsible for the red color of anthocyanins at low pH. At neutral pH, the flavylium cation undergoes deprotonation to form a resonance-stabilized quinoid base, which appears purple. With further increase in pH, the quinoid base can form anionic species that appear blue. The predicted values of the acid dissociation constant (pK

a) for these transitions are about 1–3 for the flavylium cation, 4–5 for the quinoid base, and 7.5–8 for the quinoid monoanion ([

14]; Khoo et al., 2017). In addition, the specific color of the anthocyanin also depends on the substituents in the B-ring, with hydroxyl groups tending to shift the color toward blue, and methoxyl groups toward red. For example, delphinidin (with three hydroxyl groups) appears blue, while pelargonidin (with one hydroxyl group) appears red ([

15]; Alappat and Alappat 2020).

Anthocyanins are water soluble. However, they exhibit a very interesting chemistry in aqueous solutions, and can present four main interconvertible species with different relative amounts at a given pH (

Figure 4).

At low pH, the flavylium cation is most prominent and has a deep red color. As the pH increases, the anthocyanins are converted to colorless forms such as pseudobases and chalcones, and at pH > 5, the anthocyanin changes to a blue quinoid form. These anthocyanidins are further attached to sugars such as glucose, galactose, and rhamnose via an α/β linkage exclusively at position 3 of the aglycone. Alternatively, they can also be acylated with cinnamic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, malic acid, oxalic acid, and succinic acid, to name a few ([

62]; Jung et al., 2014).

It has been established that in an acidic environment, the color of red-leafed lettuces changes due to internal rearrangements of pigments, but in parallel with this, an oppositely directed process occurs, in which the antioxidant activity of the lettuce extract increases with increasing pH, which can be used in practice when growing red-leafed lettuces with given parameters of color and quality.

5. Bioactive Phytochemicals and Metabolites of Lettuce

Lettuce is an important dietary source of bioactive phytochemicals. Screening and identification of health-promoting metabolites and assessing relationships with phenotypic traits may help consumers adjust their preferences for lettuce plant types. Modern metabolomics analysis methods allow the investigation of key health-promoting individual metabolites and antioxidant potential of agricultural plants. Assefa et al. ([

63]; 2018) using UPLC-DAD-QTOF/MS (TQ/MS) and UV-visible spectrometry instruments identified and quantified three anthocyanins, four hydroxycinnamoyl derivatives, two flavonols and one flavone in 113 samples of germplasm and commercial cultivars of lettuce at the mature stage. Total phenolic content (TPC) and 2,2-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical absorbance potentials were estimated, and the relationships between biochemical and phenotypic traits of 113 lettuces were investigated. The metabolite contents varied significantly among the lettuce samples: cyanidin 3-O-(6-O- malonyl) glucoside (4.7-5013.6 μg/g DW), 2,3-di-O-caffeoyltartaric acid (337.1-19,957.2 μg/g DW), and quercetin 3-O-(6-O- malonyl) glucoside (45.4-31,121.0 μg/g DW) were the most dominant in the red pigmented lettuce samples, and hydroxycinnamoyl and flavonol derivatives were the most abundant anthocyanins, respectively. Lettuces with dark to very dark red pigmented leaves, round leaf shape, strong leaf waviness and very tight leaf cuts were found to have high levels of flavonoids and hydroxycinnamoyl derivatives. Key variables were identified that could make a major contribution to plant breeders developing varieties with improved bioactive compounds and to nutraceutical companies developing nutrient-dense foods and pharmaceutical formulations.

Assefa et al., ([

63]; 2018) systematized the traits and quality of lettuces grown in the field and laboratory. Morphological traits were assessed based on the modified International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV) descriptors for lettuce: leaf length, width, and lettuce plant weight. Other qualitative morphological traits such as cotyledon color, plant growth type, leaf shape, leaf position, leaf blade (degree of edge waviness and density of marginal notches on the apical part), and intensity of red coloration of outer leaves were also investigated. About 76% of the samples contained red color at the cotyledon stage, while the remaining lettuce samples did not contain red color. Another important characteristic was the intensity of red coloration of the outer leaves. The intensity of red coloration was assessed on the outer leaf and ranked from 1 to 5 (very light, light, medium, dark, and very dark, respectively). Most of the samples had medium and light intensity, accounting for 37.2% and 31.9% of the total resources. The remaining 16.8%, 10.6%, and 3.5% of the samples had dark, very light, and very dark red color intensity, respectively. Total phenolic content (TPC) and antioxidant potential were quantified using spectrophotometry. As noted by the authors of the study, significant variations in the radical reduction potentials of TPC and ABTS were observed among genetic varieties ([

63]; Assefa et al., 2018).

Llorach et al. ([

64]; 2008) reported TPC contents ranging from 18.2 to 571.2 mg/100 g FW and ABTS antioxidant potential ranging from 61.3 to 647.8 mg TEAC/100 g FW for five lettuce and escarole ‘’frisseґ” cultivars. In another study, TPC contents assessed in five lettuce cultivars ranged from 13,900 to 46,900 μg GAE/g DW; red leaf cultivars showed the highest amounts. Differences were found between green and red lettuce and escarole: caffeic acid derivatives were the main polyphenols in green varieties, while flavonols were observed in higher amounts in red varieties and escarole, and anthocyanins were present only in red-leafed varieties. Moreover, lettuce and escarole showed differences in flavonol composition, as quercetin derivatives were observed only in lettuce samples, while kaempferol derivatives were found only in escarole samples. In general, red-leafed vegetables showed higher levels of both flavonol and caffeic acid derivatives than green lettuce and escarole varieties. Regarding vitamin C, red-leafed lettuces showed higher contents than green salad vegetables, with the exception of the continental variety, which showed the highest levels.

Low phosphorus and low nitrogen often cause anthocyanin accumulation in plants. Under phosphorus and nitrogen limitation, plants adapt to environmental stress by modulating nutrient partitioning and metabolic pathways, including increased anthocyanin synthesis.

Various factors including genotype, cultivar, growth stage and other cultivation conditions influence the total phenolic content and antioxidant potential of lettuce ([

3,

8,

65]; Kim et al., 2018; López et al., 2014; Pérez-López et al., 2014). The phenotypic properties of lettuce showed significant differences in antioxidant capacity and phenolic content. For example, the mean TPC and antioxidant potential of light and very light red pigmented samples were significantly lower than those of medium and dark or very dark samples. Broadly elliptical and round leaf-shaped samples were found to be superior to medium elliptical and broadly ovate leaf shapes. The mean TPC and ABTS values were also significantly higher in highly wavy leaf samples compared to those with medium and slightly wavy leaf margins. The high levels of antioxidants and total polyphenols in the lettuce samples significantly enhance their nutritional value.

Three anthocyanins (cyanidin 3-O-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-(3-O- malonyl)glucoside, and cyanidin 3-O-(6-O- malonyl)glucoside), four hydroxycinnamoyl derivatives (3-O-caffeoylquinic acid, 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid, 3,5-diO-caffeoylquinic acid, and 2,3-di-O-caffeoyltartaric acid), two flavonols (quercetin 3-O-glucuronide and quercetin 3-O-(6-O- malonyl)glucoside), and a flavone (luteolin 7-O-glucuronide) were identified and quantified in red pigmented lettuce samples in ([

66]; Su et al., 2020). In addition, TPC and antioxidant activity were evaluated. A huge diversity of biochemical traits was observed among the lettuce samples. Cyanidin 3-O-(6-O- malonyl) glucoside, 2,3-di-O- caffeoyltartaric acid and quercetin 3-O-(6-O- malonyl) glucoside were the most dominant in the red pigmented lettuce samples among the metabolite groups.

The genetic potential was explored for the health-beneficial metabolites in baby leaves of 23 diverse lettuce cultivars in ([

3]; Kim et al., 2018). The study revealed significant variations in metabolite composition and content among lettuce cultivars, primarily influenced by leaf color. Red-leaf cultivars were notably rich in carotenoids (especially all-E-lutein, all-E-violaxanthin, and all-E-lactucaxanthin), polyunsaturated fatty acids (mainly α-linolenic and linoleic acids), total phenolic content, and antioxidant potential. Cyanidin and other phenolic compounds emerged as the strongest radical scavengers based on PCA analysis. Additionally, total folate content ranged from 6.51 to 9.73 μg/g (DW), depending on the cultivar. These findings highlight red-leaf lettuce as a nutrient-rich food with a unique phytochemical profile.

Thus, several factors may contribute to the large variations in the phytochemical composition and color of lettuce, including the genotype of the cultivar. The intensity of red color, leaf shape, plant growth type, incision density, and leaf margin waviness have been found to influence the concentration of metabolites. Lettuce plants with high intensity of red color in leaves, round leaf shape, high leaf waviness, and very dense leaf incisions were found to accumulate the highest concentration of flavonoids and hydroxycinnamic acids. Overall, a number of studies have shown that red lettuce may be one of the main dietary sources of antioxidants such as caffeic acid and its derivatives.

6. Genetic Control of Anthocyanin in Lettuces

The molecular genetic basis of anthocyanin biosynthesis has been studied quite thoroughly, which has been greatly facilitated by mutants of various plant species with altered coloration. Anthocyanin biosynthesis, and consequently coloration, is affected by mutations in three types of genes: the first are genes that code for enzymes involved in the chain of biochemical transformations (structural genes); the second are genes that determine the transcription of structural genes at the right time in the right place (regulatory genes); and the third are genes of transporters that carry anthocyanins into vacuoles. It is known that anthocyanins are oxidized in the cytoplasm and form bronze-colored aggregates that are toxic to plant cells ([

46]; Noda et al., 1994).

As shown in ([

66]; Su et al., 2020), when grown under optimal conditions, wild lettuce typically develops green leaves with intermittent accumulation of anthocyanins near the leaf margin. Stress, such as drought, promotes anthocyanin accumulation, resulting in a noticeable red coloration of wild lettuce leaves. However, some lettuce cultivars have lost this stress response due to loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding bHLH. On the other hand, some lettuce cultivars develop red leaves when grown under optimal conditions.

Recent studies have shown that light signals regulate anthocyanins through CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1), which is a negative regulator and mediates the degradation of positive regulators of anthocyanins such as PAP1 and PAP2 in

Arabidopsis or MdMYB1 in apple ([

67,

68]; Lee et al., 2012; Hong et al., 2016). Most experiments conducted to study light signal transmission are analyzed by excluding light. However, in was shown in ([

44,

69]; Zhang et al. 2018; Yang et al., 2018) that the COP1/SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA (SPA) complex may not be completely inactivated at low light intensity, suggesting the existence of some other light intensity-induced mechanism in anthocyanin accumulation.

Leaf color is an important factor influencing consumer acceptance of red leaf lettuce, and light significantly influences leaf color ([

46]; Noda et al., 1994). It was shown in ([

70,

71]; de Pascual-Teresa and Sanchez-Ballesta, 2008; Khan and Abbas, 2023) that red leaf lettuce had greener leaf color when grown under controlled conditions at a light intensity of 40 mmol m

-2 s

-1, whereas increasing the light intensity to 100 mmol m

-2 s

-1 resulted in lettuce with a redder leaf color. This red color is known to be due to increased anthocyanin accumulation ([

72]; Kumar et al., 2022). However, the molecular mechanisms governing light-induced anthocyanins in red leaf lettuce are still not fully understood.

Anthocyanin biosynthesis has been studied quite extensively in

Arabidopsis, and more than 29 anthocyanin molecules have been identified in

Arabidopsis ([

71]; Khan and Abbas, 2023), which are regulated by strong light alone or in combination with low temperature exposure. However, the regulation of phytochemical biosynthesis and its accumulation, as well as the underlying molecular mechanisms of light-induced phytochemical biosynthesis, are poorly understood in lettuce.

Constitutive up-regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis is mediated by a gain-of-function mutation in the gene encoding the MYB transcription factor and loss-of-function mutations in two negative regulators ([

66,

73]; Su et al., 2020; Khusnutdinov et al. 2021). Thus, green-leaf and red-leaf lettuce cultivars have been selected both during domestication and in modern breeding programs, demonstrating typical artificial disruptive selection, i.e., selection favoring extreme values over intermediate values ([

6,

31]; Shi et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2024). Varieties lacking anthocyanins may have reduced ability to withstand biotic and abiotic stress. On the other hand, varieties with high concentrations of anthocyanins in epidermal cells will block light penetration and, therefore, reduce photosynthesis and plant growth. But such selection based on green and/or red vegetable leaves is carried out by humans, and this is artificial selection.

Using gene annotation and phylogenetic analysis, putative structural genes involved in anthocyanin synthesis and transport were identified (

Table 2 adapted from

Table 1 in ([

44]; Zhang et al., 2018). NCBI GenBank accession numbers were MF579543–MF579560. The authors of the study identified nine key genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis: seven anthocyanin structural genes, including

CHS, CHI, F3H, F3′H, DFR, ANS, and

3GT, and two anthocyanin transport genes,

GST and

MATE. Besides of this, six anthocyanin regulatory genes were identified: five MYBs and one bHLH gene.

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants is mainly controlled by some structural anthocyanin biosynthesis genes, which are divided into two groups: early biosynthetic genes (EBGs, such as

CHS,

CHI, and

F30H) and late biosynthetic genes (LBGs, such as DFR

LDOX,

UF 3 GT,

UGT 75 C 1, and

3 AT 1) ([

44]; Zhang et al., 2018). EBGs encode key enzymes for the synthesis of precursors common to flavonoids or other phenolics, while LBGs encode enzymes specific to anthocyanins ([

17]; Belwal et al., 2020). Thus, it can be concluded that anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants is mainly regulated by the MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) complex ([

44,

74]; (Zhang et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2023). The

HY5 gene was discovered, which can respond to light signals and regulate the structural genes of anthocyanins. These genes were significantly overexpressed (log2FC = 2.7–9.0) under high irradiance and were confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR ([

44]; Zhang et al., 2018).

Although biosynthesis of anthocyanins is regulated mainly by the MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) complex, it is also greatly influenced by various environmental factors (e.g., light, salinity, drought, cold) and phytohormones (e.g., jasmonate, abscisic acid, and auxin). Advances in understanding these regulatory networks highlight anthocyanins' potential applications in agriculture, horticulture, and the food industry ([

73]; (Shi et al., 2023).

8. Conclusions

This review presents a comprehensive analysis of modern approaches to studying the uniqueness and value of red-leaf lettuces, highlighting their practical application and potential for advancing cultivation technologies. Red-leaf lettuces stand out due to their exceptional aesthetic and functional properties, offering a rich source of bioactive phytometabolites such as anthocyanins, flavonoids, and carotenoids. These compounds not only contribute to the vibrant red coloration but also play a significant role in improving human health by boosting immunity and reducing the risks of oxidative stress-related diseases. The ability to manipulate plant traits such as color, taste, size, and productivity by leveraging cultivation technologies underscores the versatility and adaptability of red-leaf lettuce as a crop. The summarized findings are presented in

Table 3, which outlines the genetic and environmental factors influencing leaf coloration and phytochemical content.

The cultivation of red-leaf lettuces in controlled environments, such as vertical farms, offers significant advantages for meeting consumer and market demands. Technologies like LED lighting enable precise control over phenotypic traits, allowing growers to optimize color intensity, antioxidant content, and nutritional value. Low root-zone temperatures and carefully tailored light spectra have been shown to enhance the accumulation of anthocyanins and other valuable compounds, while maintaining acceptable levels of plant productivity. These insights are crucial for developing high-value products tailored to the preferences of consumers and the requirements of industrial partners, such as LLC “Zelen,” which aims to commercialize red-leaf lettuce production in vertical farming systems.

Furthermore, the review emphasizes the importance of promoting a dietary culture that includes green crops, particularly red-leaf lettuces, due to their health benefits and rich phytochemical profiles. Consumers, breeders, and nutraceutical companies are encouraged to focus on key phenotypic traits—such as color intensity, leaf shape, and phenophase transitions—as well as abiotic conditions like temperature, pH, and light spectrum. These factors provide opportunities to enhance the genotype’s potential and produce crops with superior nutrient content and functional qualities.

The prospective studies should integrate these findings into practical agronomy to address both consumer preferences and market demands. As an example of such studies is the research that is planned to be conducted in the City Farming Laboratory of the Gastronomy Institute at Siberian Federal University (Krasnoyarsk, Russia;

https://www.sfu-kras.ru/en/news/26285, assessed on December 15, 2024). This initiative aims to establish sustainable production technologies for red-leaf lettuces in vertical farming systems, creating innovative solutions for the restaurant industry and promoting functional foods in everyday diets. This approach combines cutting-edge cultivation practices with a deeper understanding of genetic and environmental factors, delivering high-quality products for modern agriculture and gastronomy.