1. Introduction

Integrity is a crucial evaluation criterion for localization systems, complementing traditional metrics such as accuracy [

1,

2]. Integrity is a concept widely utilized in the literature to quantify the degree of confidence that can be placed in a localization system. Although this is an informal definition, it highlights the importance of integrity, which is further elaborated in

Section 3. For example, achieving high levels of automation as defined by SAE [

3] in autonomous driving systems (ADS) requires not only highly accurate localization, but also a guarantee of integrity.

The estimated state of a localization system is affected by different types of errors, as detailed in

Section 2.1. To address these errors, methods are needed for both qualifying (see

Section 6 and

Section 7) and quantifying (see

Section 4) their impact on state estimation. The integrity criterion assesses the influence of these errors on the state estimate and provides a quantitative measure of the variation in the estimation error.

The importance of integrity spans various domains. Primarily, safety is paramount. In the United States, motor vehicle crashes result in over 40,000 deaths annually and injuries to over 2 million people [

4]. Localization errors can have dire consequences, including incorrect navigation decisions and collisions [

5]. In addition, integrity fosters consumer confidence, which is critical for the widespread acceptance of self-driving vehicles [

6]. Integrity provides users and stakeholders with a measure of confidence in autonomous systems, enhancing operational efficiency through precise navigation, route planning, and vehicle control. This results in more efficient and seamless road operations. Furthermore, integrity is essential in challenging environments, quantifying system performance and safety in scenarios such as extreme weather or limited vision.

Robotic systems, including autonomous vehicles, consist of sensors, electromechanical components, and algorithms. This survey focuses on methods addressing sensor and algorithm failures, which compromise localization integrity. Due to the diversity of failures, various techniques have been developed to mitigate their effects, as no single approach can handle all faults effectively, see

Section 6,

Section 7 and

Section 8.

Several surveys have reviewed integrity monitoring (IM) methods for GNSS and related systems. For example, [

7] is dedicated to GNSS technologies and exposes the so-called "Receiver Autonomous Integrity Monitoring" (RAIM) methods. It classifies integrity techniques, including fault detection, exclusion methods, and protection level computation formulas, as seen in

Section 2.2. Similarly, [

8] addresses GNSS integrity, focusing on urban transport applications, and highlights challenges and differences between aviation and urban environments while noting open research areas.

The survey [

9] reviews IM methods for GNSS, INS, map-assisted, and wireless signal-augmented navigation systems. It covers measurement errors, faults from various data sources, and the integration of sensors with GNSS to improve navigation reliability. The review identifies challenges and highlights the need for advances in fault detection, exclusion, error modeling, and real-time processing. It also explores IM techniques for GNSS/INS with map-matching, discussing map/map-matching errors handling and map constraints.

In contrast, our survey focuses on a wider spectrum of localization systems. We include techniques such as SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping), fusion algorithms, and optimization-based algorithms. We categorize integrity methods into Fault Detection and Exclusion (FDE), Protection Level (PL), and Robust Modeling. Our detailed analysis covers a wide range of sensors, including LiDAR, cameras, HD maps, INS, and others, offering a broader scope compared to the aforementioned surveys that focus primarily on GNSS. Our review emphasizes integrity in perception-based localization systems and highlights gaps in the literature regarding PL methods for these sensors.

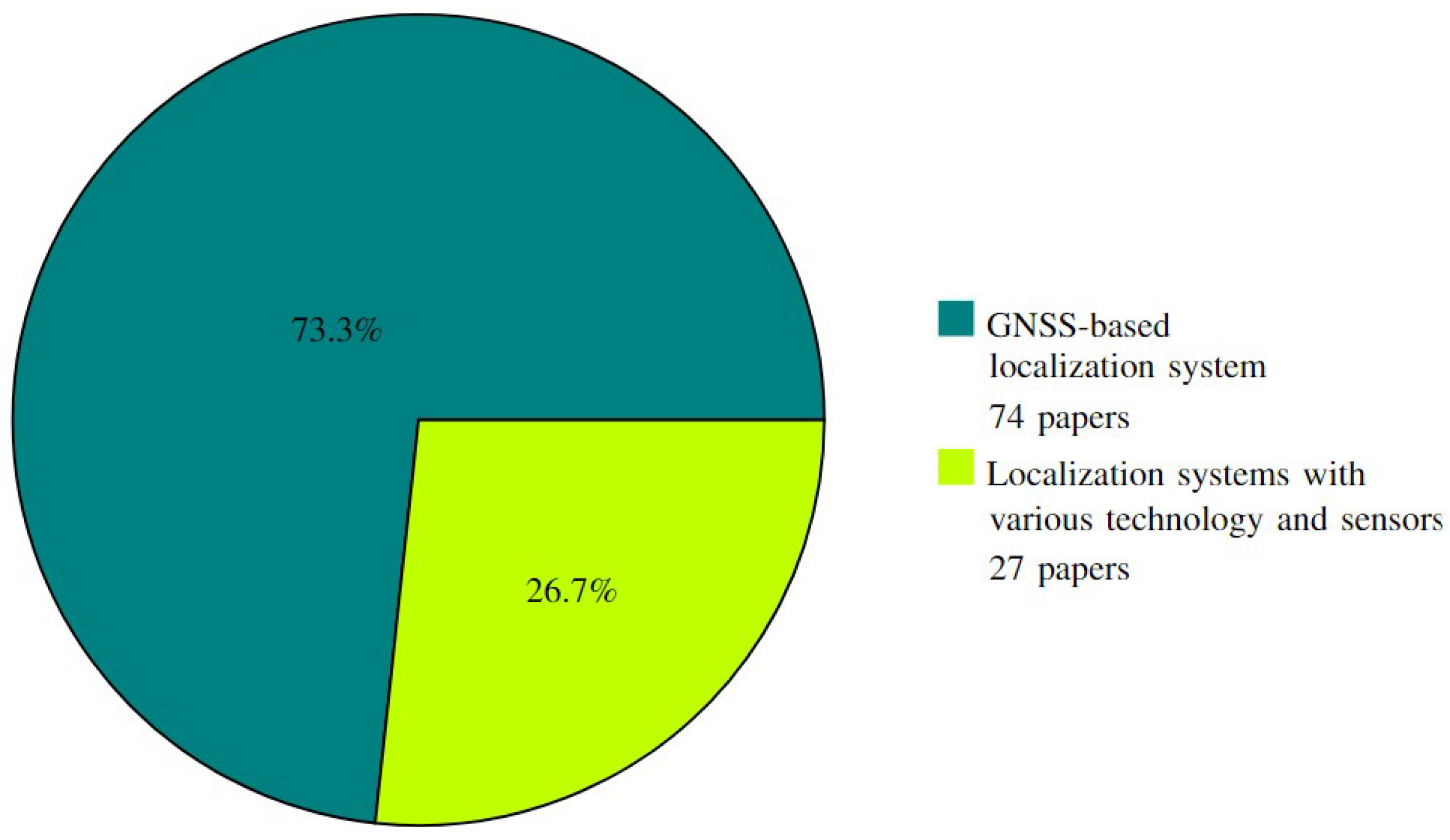

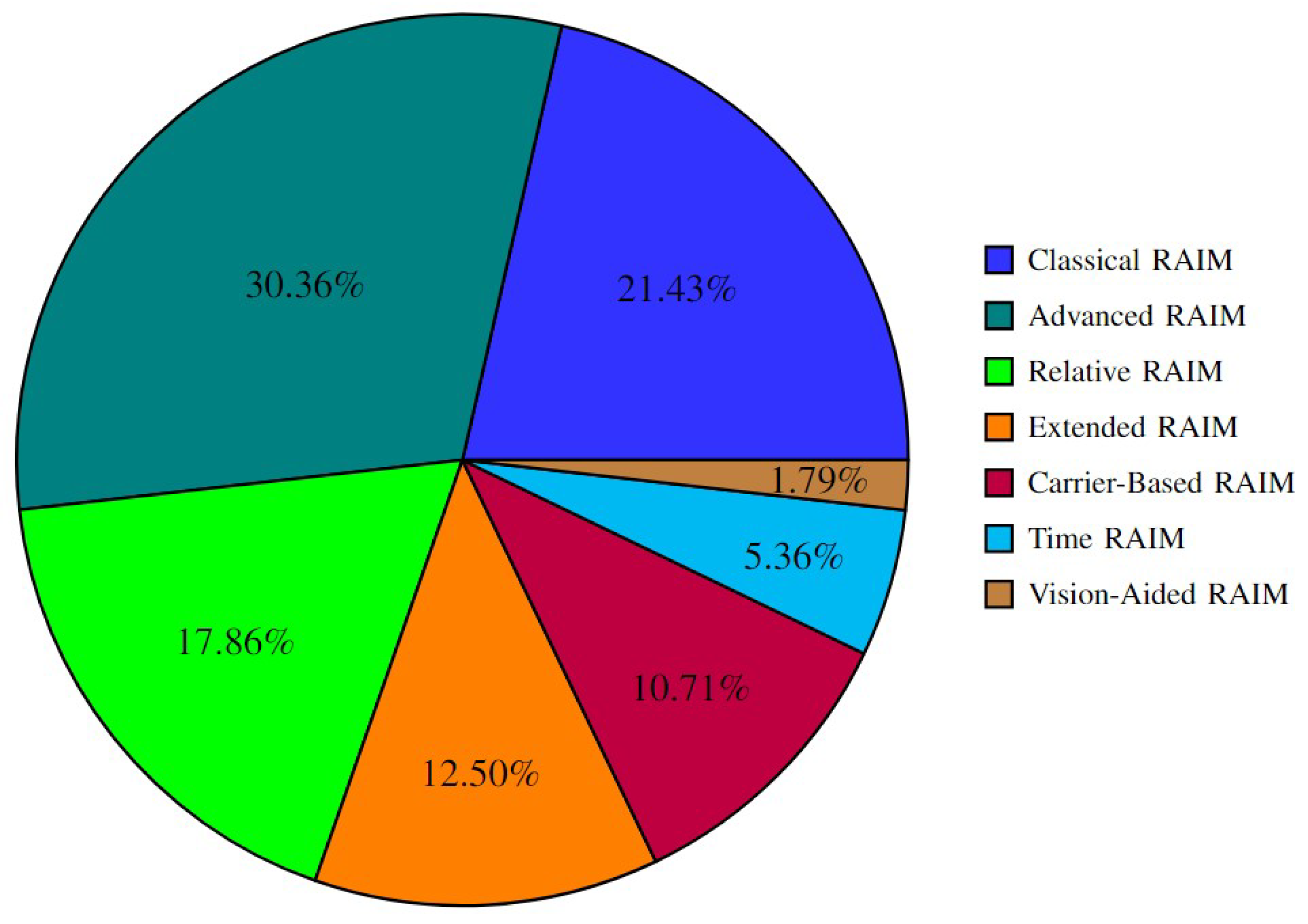

Figure 1 compares GNSS-based integrity methods with other localization systems integrity methods, based on data from [

7,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] for GNSS-based localization method and localization systems with other sensors and technologies that appeared in

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 8. The pie chart shows the percentage of research focused on GNSS versus other localization systems. This limited percentage of work on localization systems with different sensors and techniques underscores the need for further exploration in this area.

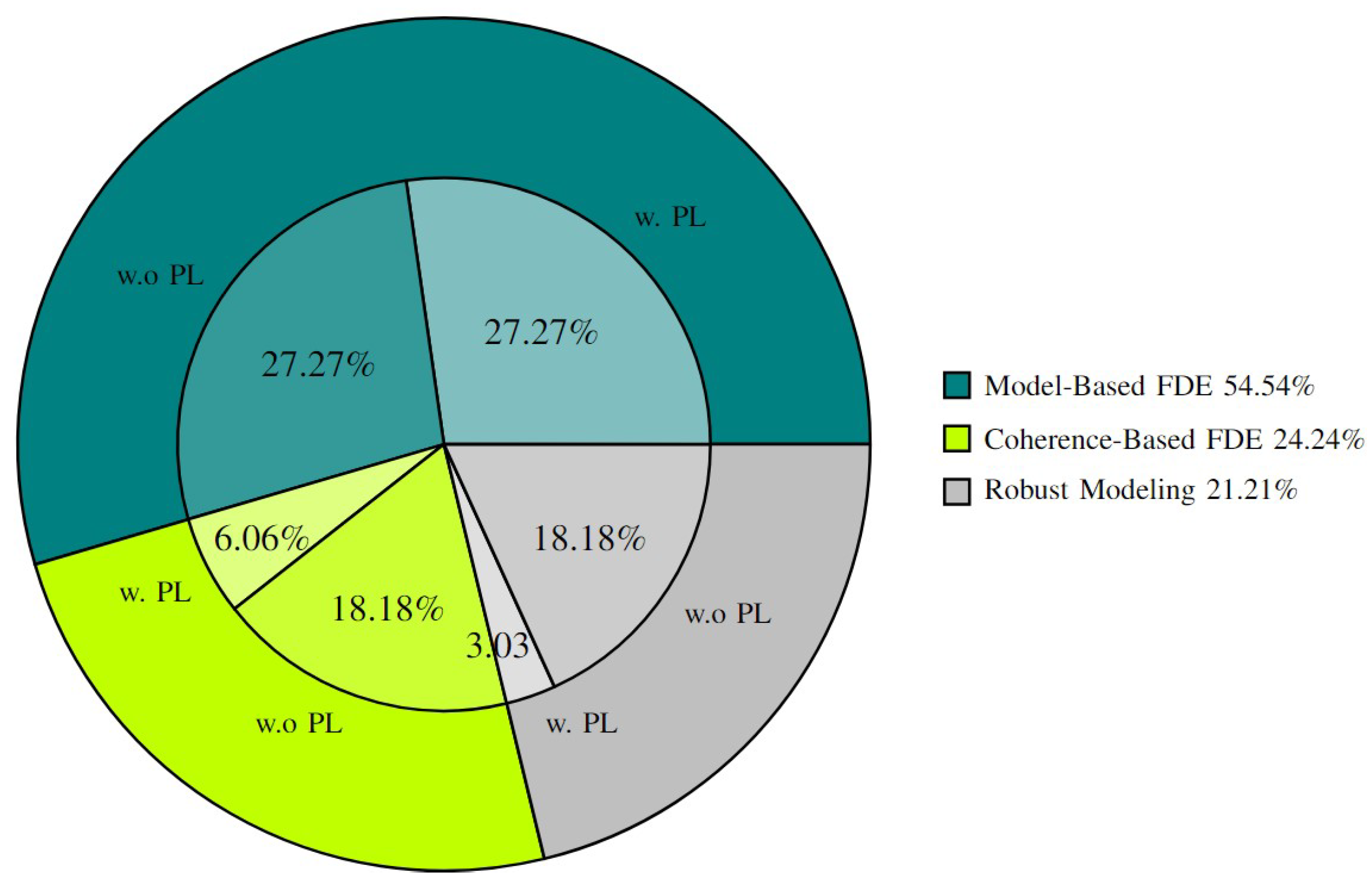

Figure 2 shows the distribution of surveyed papers and reveals a significant gap in PL methods for perception-based localization.

The review aims to:

Redefine integrity

Redefine integrity of localization systems

Redefine protection level

Introduce robust modeling as a new integrity method

These concepts are redefined because no single, accepted definition exists. The new definitions provide a universal view, helping researchers understand and apply integrity concepts.

Current definitions often overlook important aspects of the integrity of localization systems. Many focus on warnings, trust, or accuracy but miss how integrity should be used as an evaluation criterion. The new definition includes both qualitative and quantitative aspects.

In conclusion, the survey shows the importance of integrity methods in localization systems beyond GNSS. The lack of focus on PL methods in perception-based localization reveals a major research gap. This work offers a clear framework and redefines key concepts to advance the field and create more reliable and robust localization systems.

In brief, the following contributions have been made:

Comprehensive Overview of Integrity Methods: Provides a thorough review of integrity methods applied to localization systems, covering a wider range of sensors, including LiDAR, cameras, HD maps, INS, and others

A new Classification Framework: Introduces a new classification framework for integrity methods

Refined Definitions: Offers updated definitions of integrity and protection levels specific to localization systems, clarifying key concepts and metrics

An in-depth review and comparative analysis of robust modeling, PL computations, and FDE techniques

A detailed comparison based on the employed techniques or algorithms, evaluation metrics, data types, sensors, and integrity enhancement.

The subsequent sections of this paper are structured to comprehensively explore the integrity methods for localization systems in autonomous vehicles. Beginning with

Section 2, the reader is provided with essential background information explain diverse error types and integrity definitions, including a new definition of integrity. Subsequently,

Section 3 systematically introduces a spectrum of integrity methods, offering a potential framework for their categorization. In

Section 4, the focus shifts towards addressing various protection level definitions found in the literature, accompanied by the proposal of a new definition. Additionally, in

Section 2.3, we review key concepts and parameters used to understand the protection level.

Section 6,

Section 7 and

Section 8 examines techniques aimed at enhancing localization system accuracy, delving into fault detection and exclusion methodologies alongside robust modeling strategies.

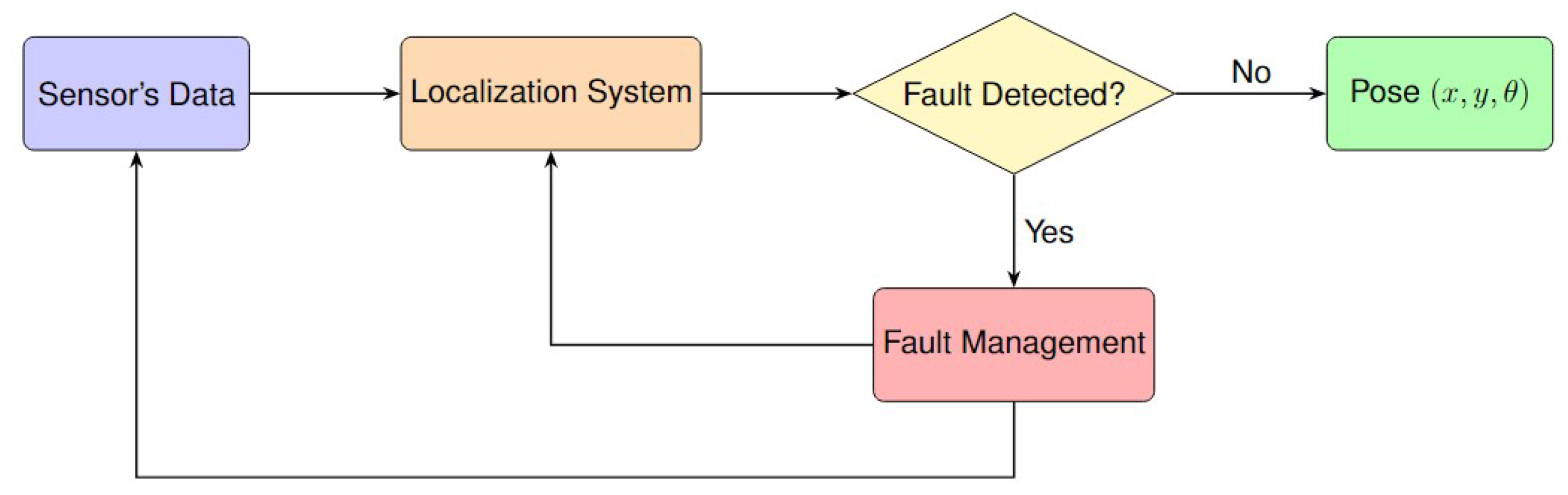

2. Background and Foundational Concepts

This section defines the vocabulary used to describe the integrity of localization systems. First of all, this section introduces various error types that localization systems encounter. Then, the different perspectives on the integrity definition appears in the literature are discussed. Finally the section concludes with a proposed integrity definition that encompasses the different dimensions of the definitions found in the literature.

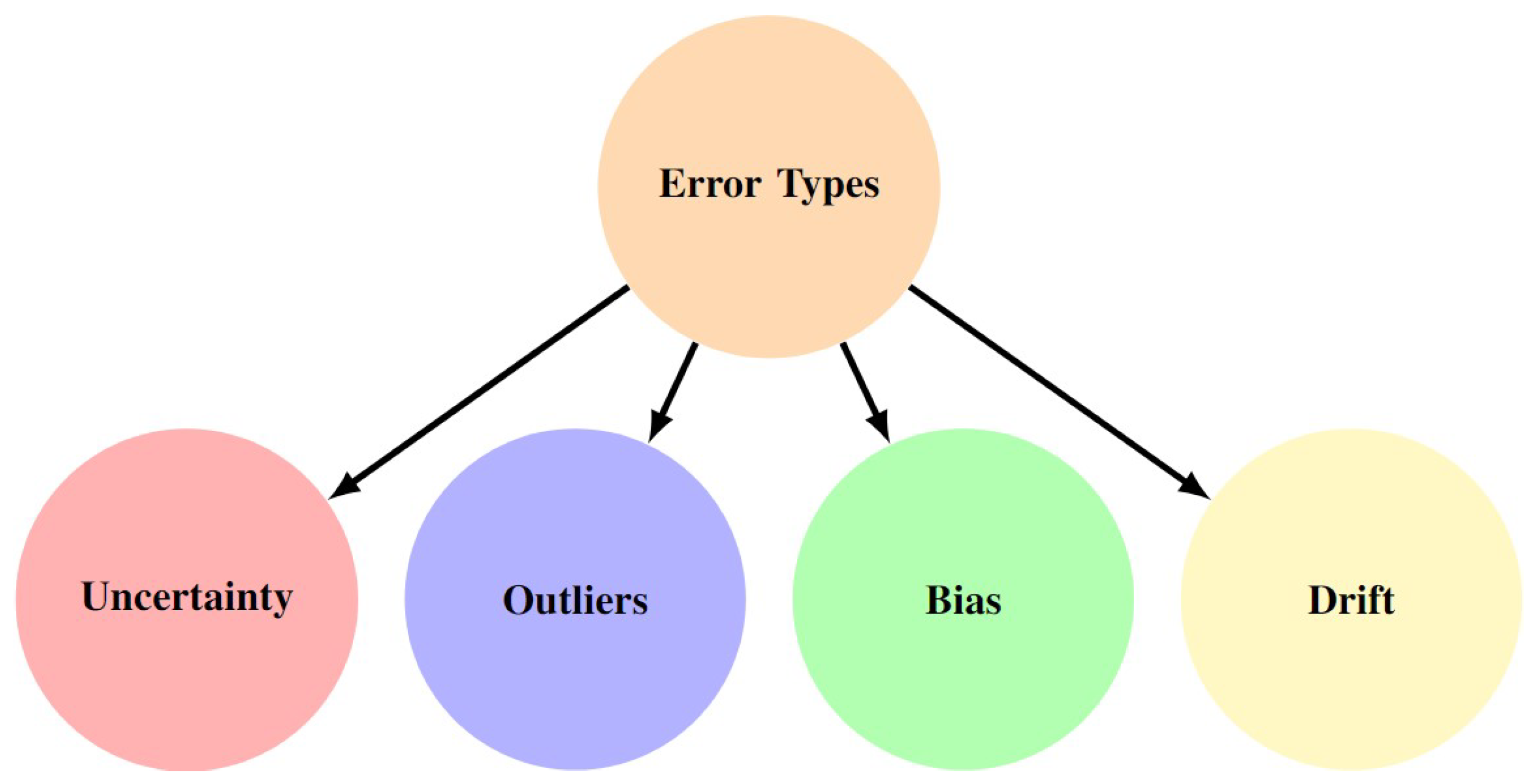

2.1. Errors Types

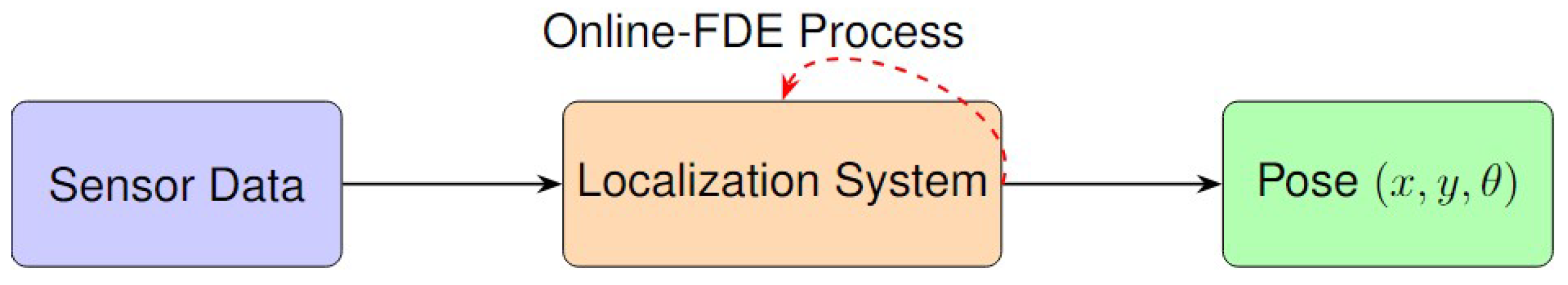

A localization system can be affected by several types of errors as depicted in

Figure 3. These different types of errors jeopardize the integrity of localization systems. The following is a brief overview of each error’s type:

2.1.1. Uncertainty

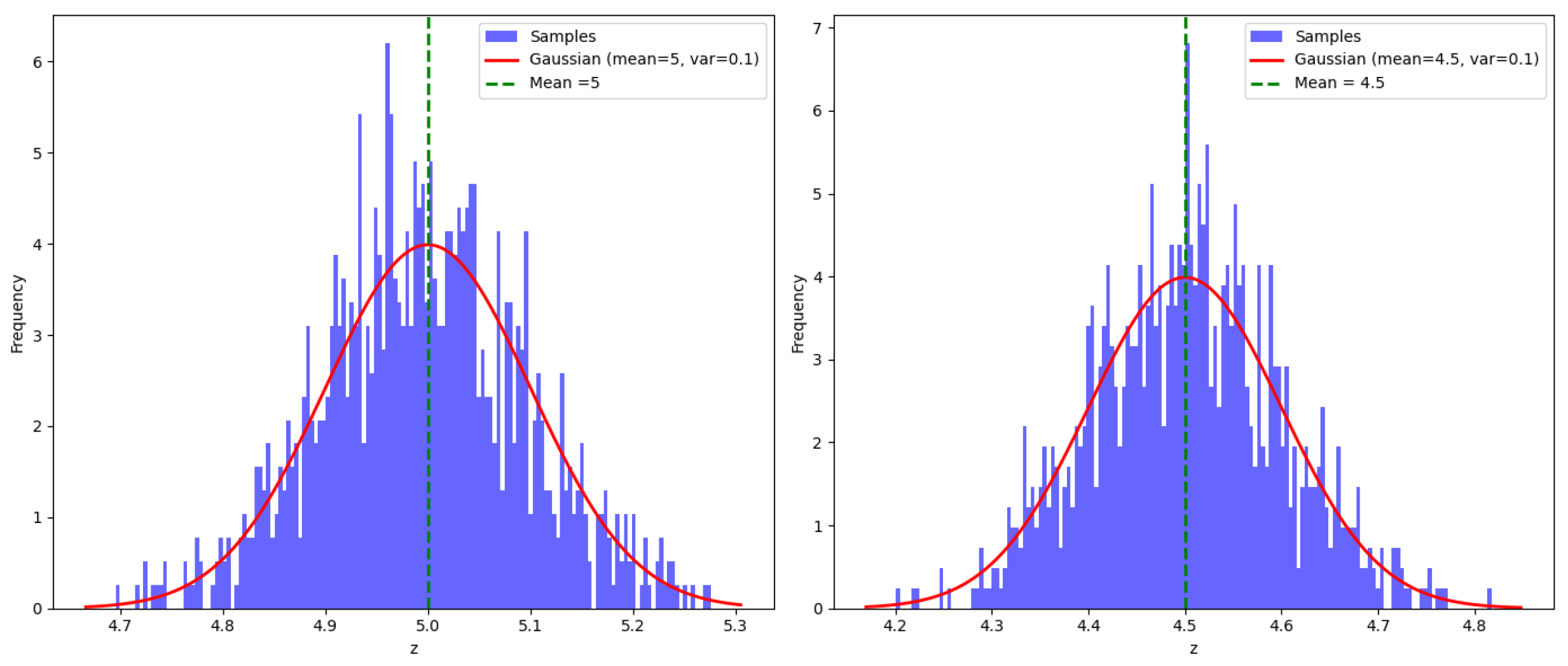

Uncertainty or random error, (left image in

Figure 4), is defined as "a short-term scattering of values around a mean value" [

15]. These errors usually expressed using a probabilistic density function such as Gaussian.

2.1.2. Bias

Bias or systematic error, (right image in

Figure 4), is defined as " a permanent deflection in the same direction from the true value" [

15].

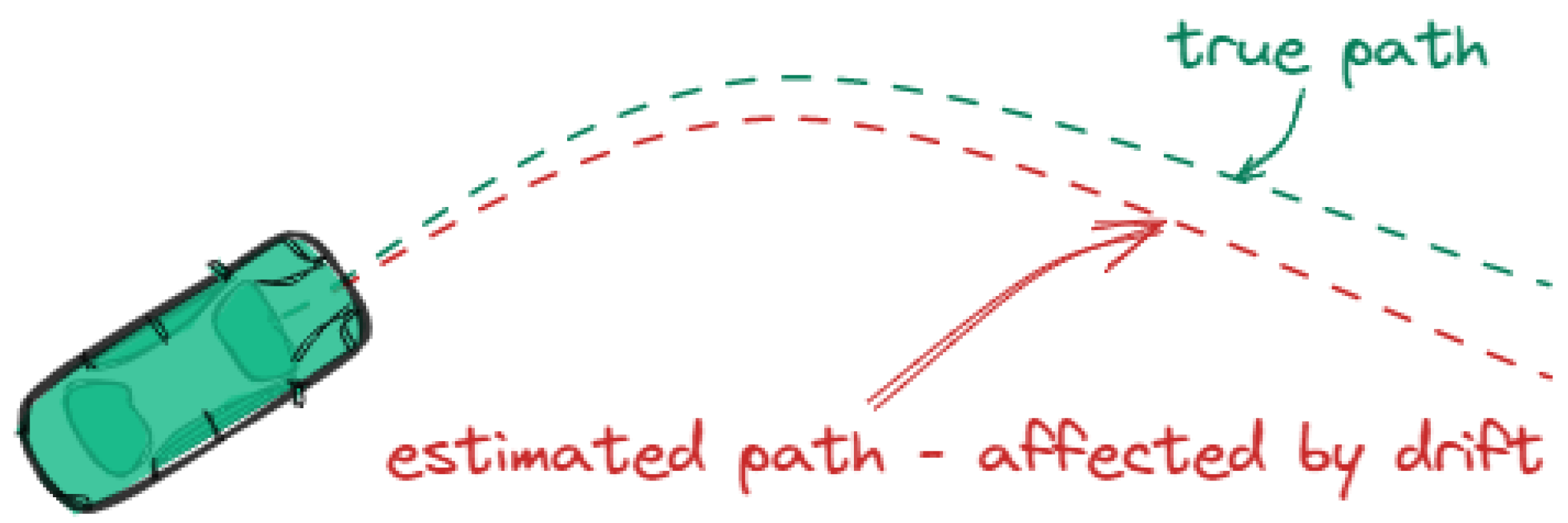

2.1.3. Drift

Drift is defined as "errors that grow slowly over time" [

9], see

Figure 5.

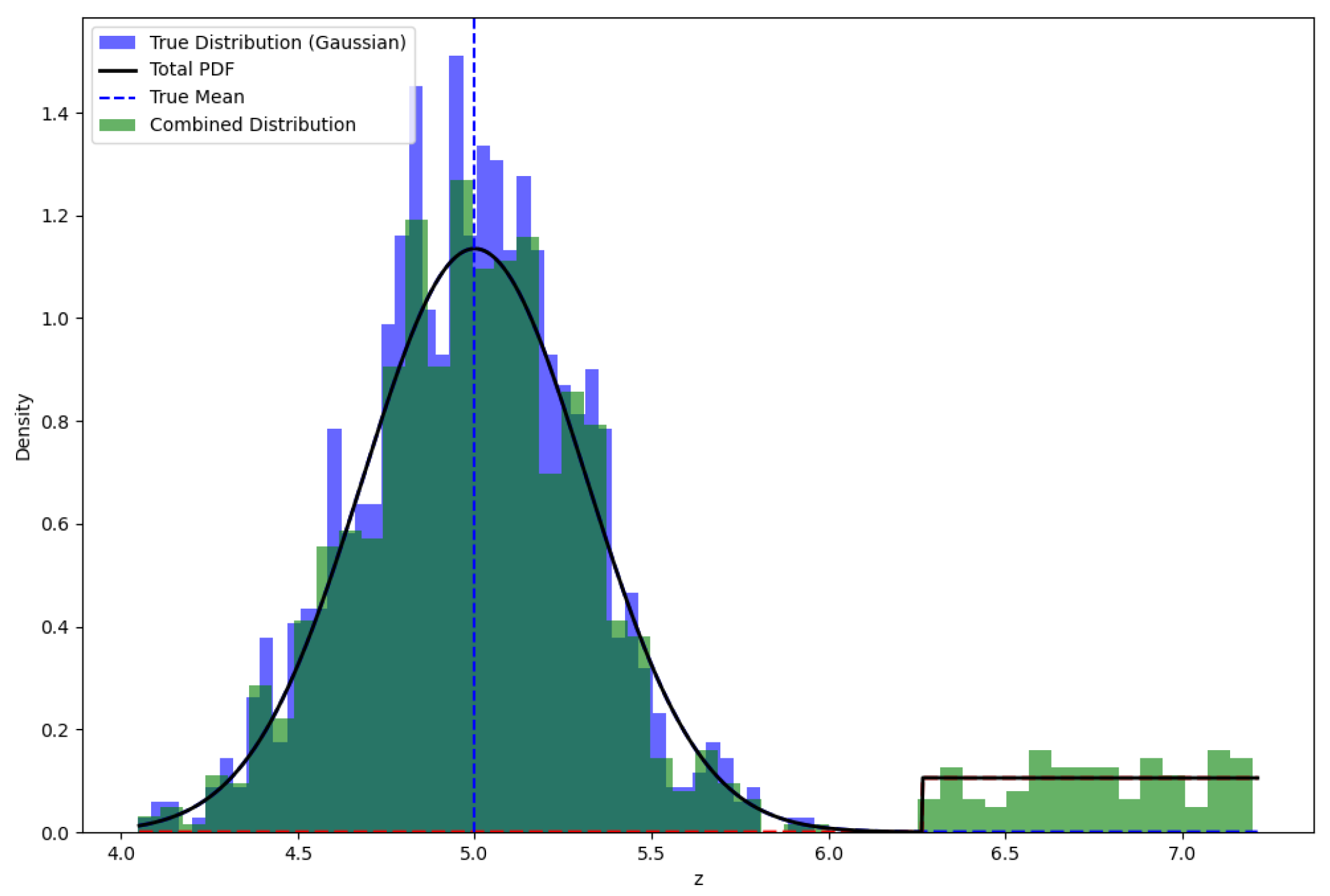

2.1.4. Outlier

Outlier is defined as "an observation which deviates so much from other observations as to arouse suspicions that it was generated by a different mechanism" [

16], see

Figure 6. This indicates that it is produced by a population different from the one we initially assumed. Consider a point cloud data observation from a LiDAR at time

t,

, where

N is the number of LiDAR beams. This observed point cloud does not contain only the true point cloud data,

, but also different types of errors. In order to incorporate all the previous types of errors into a mathematical model, let us consider only one beam, the

k-th beam. The previous errors types, except the outlier, can be incorporated in the following mathematical expression:

The PDF for the

is given as a

. Assuming that the outlier generated with a probability

from an unknown PDF given as

[

16]. Thus, the distribution of an arbitrary LiDAR beam would be :

This model describes all different types of errors that a measured value might experienced.

In localization systems, no one integrity enhancement method can handle all errors types illustrated in Equations (1) and (2).

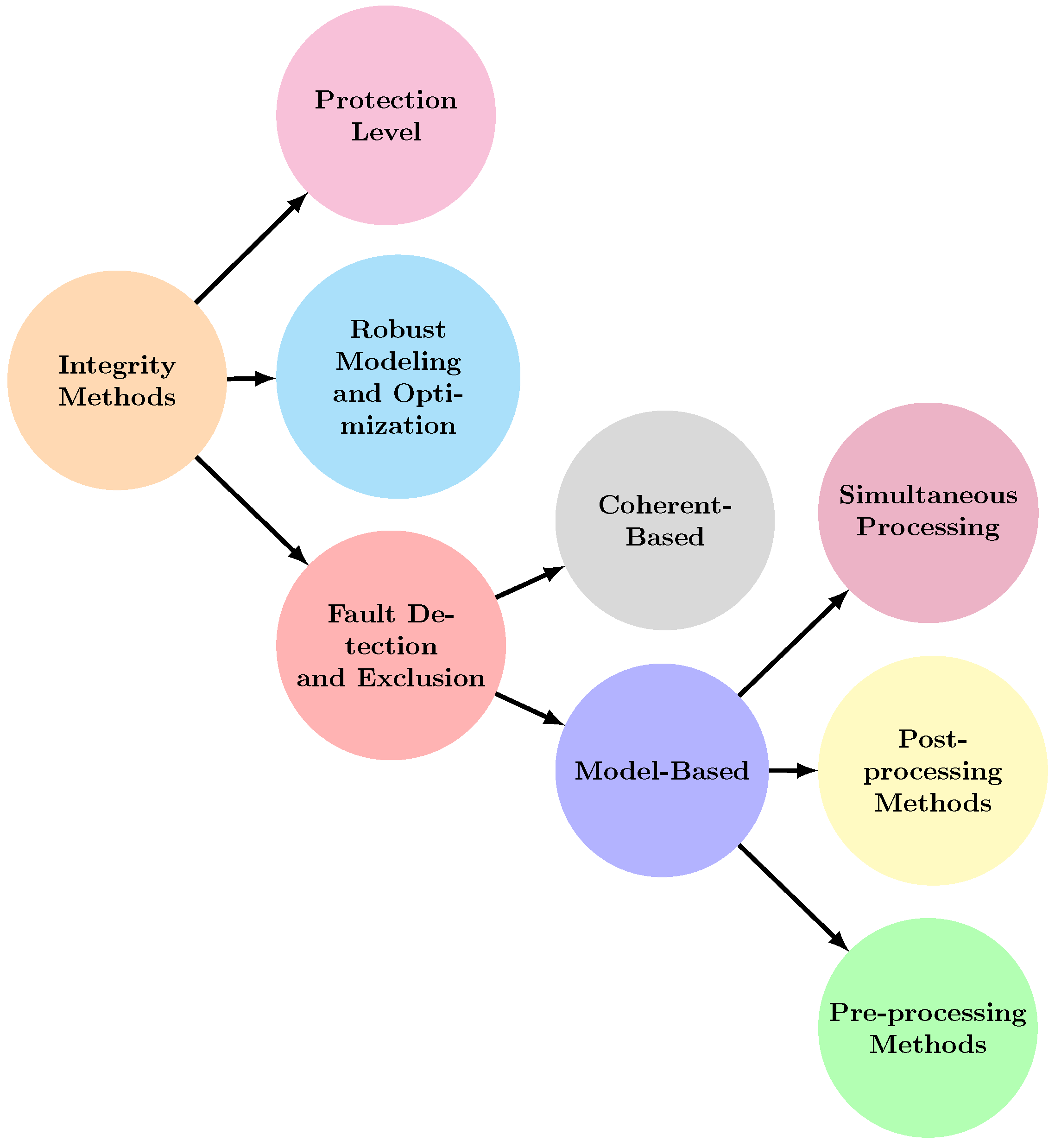

Figure 7.

Classification of Integrity Methods.

Figure 7.

Classification of Integrity Methods.

2.2. Integrity Methods in GNSS Systems

Understanding and ensuring integrity in localization systems is critical across various applications. While this paper primarily focuses on perception-based systems, many of the foundational methods for achieving integrity originate from the field of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS). To provide a brief overview, this section presents key integrity methods used in GNSS systems. This review highlights foundational techniques and concepts. This overview is not exhaustive and does not cover all aspects of GNSS integrity in detail. For a comprehensive review, readers are encouraged to consult the surveys [

7,

8].

GNSS systems use various integrity methods, mainly categorized into Receiver Autonomous Integrity Monitoring (RAIM) and Protection Level (PL) calculation.

RAIM checks the consistency of multiple satellite signals by computing the position using different subsets of satellites and comparing the results. It requires a minimum of five satellites to detect faults but is typically limited to handling only one faulty satellite at a time.

Different RAIM variants use various measurements, like code or carrier measurements. They also differ in their fault detection capabilities. Advanced RAIM, for instance, can handle multiple faults more effectively compared to traditional RAIM. For a detailed comparison of measurement types and fault detection capabilities in these variants, refer to the surveys [

7,

8]. In this section, the results from these surveys are summarized and illustrated in

Figure 8, with a focus on the RAIM variants.

Protection Level (PL) indicates the potential deviation between the true and estimated positions provided by a GNSS receiver. PL depends on satellite-user geometry and expected pseudorange error. For example, in SBAS (Satellite-Based Augmentation System), PL is calculated as [

17]:

where

K is an inflation constant and

represents the confidence in the estimated position, measured in meters. Accurate PL computation requires knowledge of the distribution of residual position or range errors [

18,

19,

20]. While PL has several formal definitions, discussed in

4, this informal description captures its essence and primary use in GNSS systems.

2.3. Protection Level Related Parameters

To facilitate the understanding of the PL concept, some terms and vocabulary will be introduced. The section will conclude with a proposed definition of PL.

2.3.1. Position Error

Let

x represent the estimated pose, and

denotes a true pose. The position error, or simply the error, is the difference between the estimated pose and the true pose,

. Typically, systems such as RTK-GNSS [

21,

22] provide an accurate estimation of the true pose. However, the localization system lacks knowledge of the correct path. Position errors are represented by a probability distribution,

, which gets altered by numerous types of errors and approximations. In an ideal scenario with a linear system, Gaussian assumptions, and no errors of any types, the final probability distribution function (PDF) would be Gaussian density function, i.e

.

2.3.2. Alarm Limit

According to [

8], Alarm Limit (AL) "Represents the largest position error allowable for safe operation". Or put it differently it is the maximum value,

. Beyond the AL the localization system considered unsafe to rely on.

2.3.3. Integrity Risk (IR)

Or the loss of integrity, it is the probability that the

E will exceeds the AL or

[

8,

23,

24]. This can be shown mathematically as:

Because the AL changes with time and context, as noted in [

25], the PL is used as a more stable alternative. Consequently, in [

26,

27,

28], the Integrity Risk (IR) is defined as:

IR could be intuitively understood as the number of times that the

E exceeds the AL, usually per-hour or per-mile. Thus, IR is the probability that a localization system might provide inaccurate poses without alerting the user. It quantifies the likelihood of undetected failures in the system that could result in dangerous or misleading outputs.

2.3.4. Target Integrity Risk (TIR)

TIR Is defined as the accepted level of risk [

26,

27,

28], thus it is an upper bound on the IR.

TIR is the minimum acceptable level of IR that a system must meet to be considered safe and integer within a specific scenario. Where it is specified by industry standards and regulatory agencies, often based on historical data and safety studies. IR is continuously monitored to ensure the system remains within safe limits. Furthermore, IR is measured using system performance data, error models, and operating conditions.

2.3.5. Accuracy

As stated by [

8,

9], accuracy is the degree to which the estimated position of the system approaches the actual position.

3. Revisiting Integrity: Review, Enhancement, and New Definition

In this section, various definitions of "integrity" as presented in the literature on localization systems are reviewed and analyzed. Each definition’s approach to integrity is examined, where strengths and limitations are highlighted.

Tossaint et al. (2007) [

29] define integrity for GNSS-based localization as "the system’s ability to provide warnings to the user when the system is not available for a specific operation." This definition is highly dependent on user application and requirements and limits the measure of integrity to its ability to provide "warnings," which is vague as an indicator. Thus, it requires more specific indicators than just warnings.

Similarly, Ochieng et al. (2003) [

30] and Larson (2010) [

31] define integrity as "the navigation system’s ability to provide timely and valid warnings to users when the system must not be used for the intended operation or phase of flight". These definitions, while emphasizing warnings, do not address the need for detailed information about issues and potential consequences, allowing them to make informed decisions.

In contrast, AlHage et al. (2021, 2022, 2023) [

26,

27,

28] define integrity as "the ability to estimate error bounds in order to address uncertainty in the localization estimates in real-time." This definition emphasizes the necessity to calculate error bounds that include the real position. Even though the definition does not explicitly mention it, they perform a Fault Detection and Exclusion method, referring to it as internal integrity to enhance the overall system integrity. However, the definition itself is not explicit enough to indicate all these aspects.

Li et al. (2019, 2020) [

32,

33] describe integrity as "the degree of trust that can be placed on the correctness of the localization solution, and compared it with the

used in visual navigation". While this provides a useful measure, it lacks clarity on whether this comparison is specific to vision-based systems or can be generalized to other types of localization systems.

Arjun et al. (2020) [

34] define integrity as the measures of overall accuracy and consistency of data sources. However, this definition does not address how faults impact the system. While it focuses on data source consistency, it fails to account for the quantification of fault effects, which is essential for a thorough evaluation of system integrity.

Bader et al. (2017) [

35] define integrity as "the absence of improper system alterations". This perspective is quite rigid, treating any fault as a complete loss of integrity. It does not account for the varying impacts of different faults, failing to distinguish between their effects on the system. A clearer approach would involve measuring the impact of faults to better assess system integrity.

Wang et al. (2022) [

36] describe integrity as "an important indicator for ensuring the driving safety of vehicles", but do not explain how it relates specifically to localization systems. This definition is too vague and lacks detail on what integrity means in the context of localization.

Quddus et al. (2006) define integrity as "the degree of trust that can be placed in the information provided by the map matching algorithm for each position." This definition focuses exclusively on the map matching algorithm and neglects other aspects of localization systems.

Marchand et al. (2010) [

37,

38] define integrity as "the measure of trust which can be placed in the correctness of the information supplied by the total system." Similarly, Sriramya (2021) [

39] describes it as "the measure of trust that can be placed in the correctness of the estimated position by the navigation system," and Shubh (2023) [

40] refers to it as "the measure of trust that can be placed in the accuracy of the information supplied by the navigation system." While these definitions focus on the concepts of trust and correctness, they do not clearly address integrity as an evaluation criterion for the entire localization system. The terms "correctness" and "trust" are used without clear definitions or explanations, leaving a gap in understanding how these concepts relate to a comprehensive assessment of system performance. Thus, these definitions overlook the broader need for evaluating how well the system manages errors and deviations, which are crucial for a full evaluation of its integrity. After reviewing various definitions of integrity, the following definition is proposed to address the gaps in the existing ones:

Definition 3.1 (Integrity).

Integrity refers to the quality of a system being coherent with reality.

Definition 3.2 (Integrity for Localization Systems).

In the context of a localization system, integrity serves as an important evaluation criterion, encompassing both qualifying and quantifying aspects:

Qualifying aspect: Integrity represents the system’s ability to remain unaltered and effectively handle outliers and errors

Quantifying aspect: Integrity also involves providing an overbounding measure of how far the system’s outputs can deviate from reality

The term how far will be formally quantified in Section 4.

The reviewed definitions of integrity offer various perspectives but often miss a comprehensive view of localization systems. Many focus narrowly on aspects like warnings, trust, or accuracy, lacking a holistic evaluation criterion. The proposed definition addresses these gaps by combining qualitative and quantitative dimensions. It defines integrity as the system’s alignment with reality, involving robustness, outlier management, and deviation measures.

This framework evaluates localization systems’ robustness and reliability more thoroughly. It includes qualifying methods to ensure system reliability and efficient outlier handling, with Fault Detection and Exclusion (FDE) (

Section 6 and

Section 7) methods being crucial for error mitigation. Quantifying methods, such as PL

Section 4, measure deviations from reality.

New robust modeling techniques, discussed in

Section 8, see

Figure 7, are introduced for their ability to handle outliers and provide probabilistic error interpretations. The paper also examines integrity methods across various localization techniques and sensors, ensuring a comprehensive review and defining protection level in line with the paper’s integrity definition.

Quantifying methods measure how far the system’s outputs can deviate from reality, with protection level (PL) providing this overbounding measure. Additionally, this paper introduces robust modeling techniques as new integrity method, see

Figure 7 and

Section 8. These techniques are chosen for their ability to handle outliers and provide probabilistic interpretations for the error distribution.

4. Protection Level: Current Definitions and New Perspectives

In the following discussion, multiple definitions of PL found in the literature will be outlined. These definitions capture various meanings and applications of PL in the context of integrity for localization systems. Following this review, a proposed definition of PL will be presented to broaden and enhance our understanding of this crucial topic.

Li et al. (2019, 2020) [

32,

33] describe PL as "the highest translational error results from an outlier that outlier detection systems cannot detect". This definition is limited to translational errors and does not fully address how PL should encompass all types of uncertainties, including those from various sources beyond undetected outliers. Moreover, this definition does not capture the complete error region within which the true position is guaranteed. It also falls short of considering the full scope of errors from all system components and algorithms.

Marchand et al. (2010) [

37,

38] define PL as "the result of a single undiscovered fault on the positioning error". Similar to the previous definition, this one is confined to undetected faults and does not account for multiple faults or the broader uncertainty inherent in sensor measurements.

The importance of PL as "a statistical bound on position error,

E, that guarantees that IR does not exceed TIR" is highlighted by AlHage et al. (2021, 2022, 2023) [

26,

27,

28]. In a similar way, Arjun et al. (2020) [

34] and Sriramya (2021) [

39] define PL as "an error bound linked to a pre-defined risk". These definitions connect PL to the requirement of a localization system, where TIR is used to check if the system has undetected faults. However, these definitions do not fully address how PL should account for all uncertainties from various system components.A more comprehensive definition of PL should encompass the entire error region, considering all types of uncertainties and limitations of the localization system and its algorithms.

Shubh (2023) [

40] defines PL as "the range within which the true position lies with a high degree of confidence," while Wang et al. (2022) [

36] describe it as "an upper bound on positioning error". Larson (2010) [

31] states PL as "ensuring that position errors remain within allowable boundaries, even with faults". Wang’s use of "upper bound" is too general, while Larson’s focus on error boundaries relates more to system error minimization and handling and does not clearly separate PL from the system’s accuracy.

Overall, current definitions of PL provide useful insights but lack a comprehensive view that includes all uncertainties from various system components and the limitations of the implemented algorithms. To ensure effective use in real-world scenarios, a unified definition of PL is necessary. Therefore, the proposed definition of PL is:

Definition 4.1 (Protection Level).

Protection Level is the real-time estimate or calculation of the error region within which the true position is guaranteed to lie.

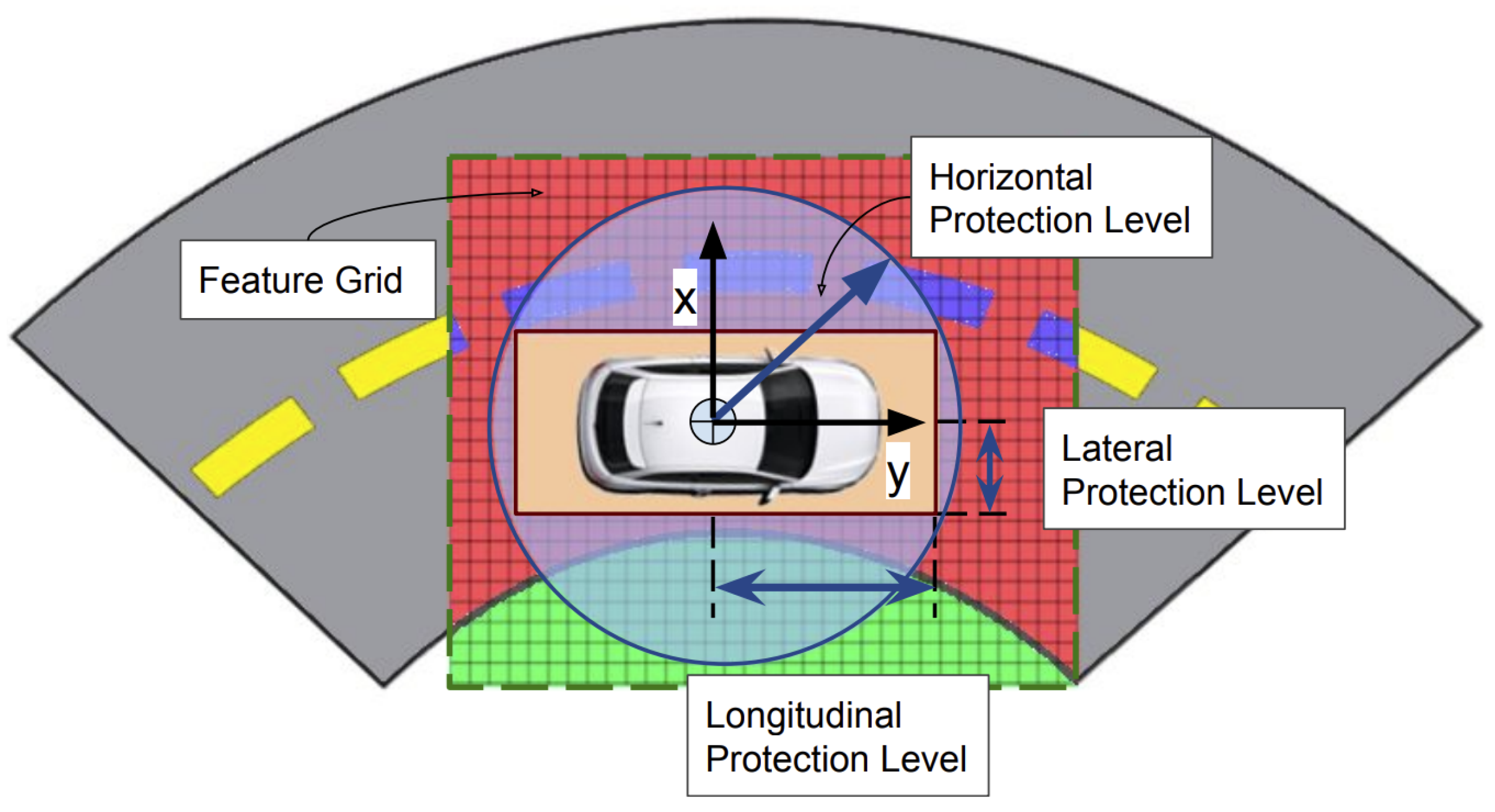

By assigning PL to each state estimate, the localization system can effectively adjust to changing environments, sensor conditions, and vehicle dynamics. As a result, system integrity is properly assessed and maintained in real-time.

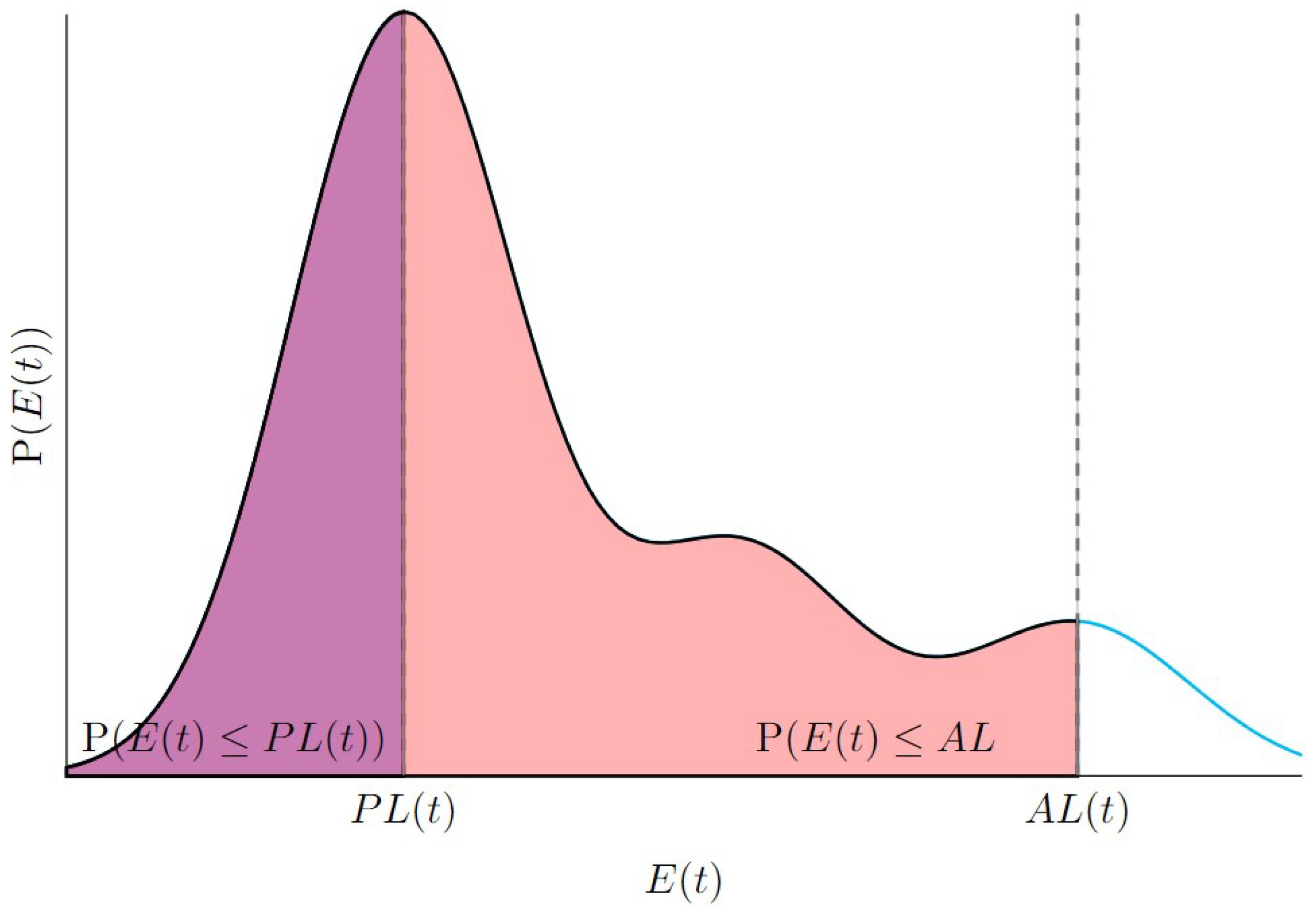

Figure

Figure 9 illustrates how the PL is evaluated at a specific time

t. For a given PL, we can compute the probability that the error is below this level based on its probability distribution at time

t. Similarly, if we have an AL, we can determine the probability that the error is below the AL. This enables us to calculate the Integrity Risk for the PL,

or the AL,

.

This is the forward approach: we use a given PL to check if it satisfies the integrity risk criterion. However, the main goal is to determine the PL that meets a specified integrity risk for a given context and period of time. This is done based on the error distribution at that moment of time. Thus, finding the PL that ensure the desired level of integrity risk.

Usually, TIR is used to refine and adjust the PL by tuning its parameters to fit the entire trajectory of the localization system. This is typically done offline, using a learning approach with training and validation data sets, as described in [

27]. The goal is to find the parameters that best fit the whole trajectory. In contrast, our focus is on estimating the PL in real-time at each time step based on the current error distribution for a given Integrity Risk.

5. Fault Detection and Exclusion

FDE is crucial for enhancing the integrity of localization system. FDE ensures accurate outputs despite faults or deviations in sensors or algorithms intended behavior. It works by identifying and removing faulty data. "Faults," "failures," and "outliers" often refer to deviations that can negatively impact estimation accuracy. FDE process addresses the qualifying aspect of integrity by making the localization resilient to various error types.

The literature distinguishes between FDE and Fault Detection and Isolation (FDI). FDE focuses on detecting and excluding anomalies to maintain integrity, while FDI aims to identify the specific cause of the problem, which is more relevant in the control engineering and software industries. For localization systems, the key objective is detecting and excluding abnormalities, regardless of their cause. Therefore, this discussion considers all approaches under the category of FDE.

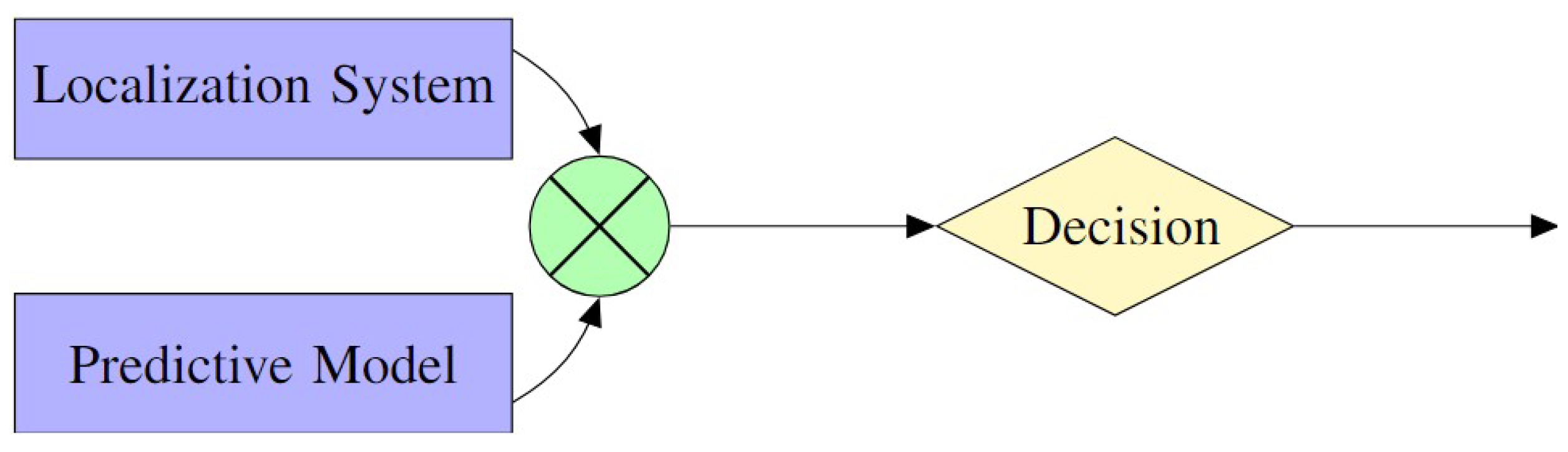

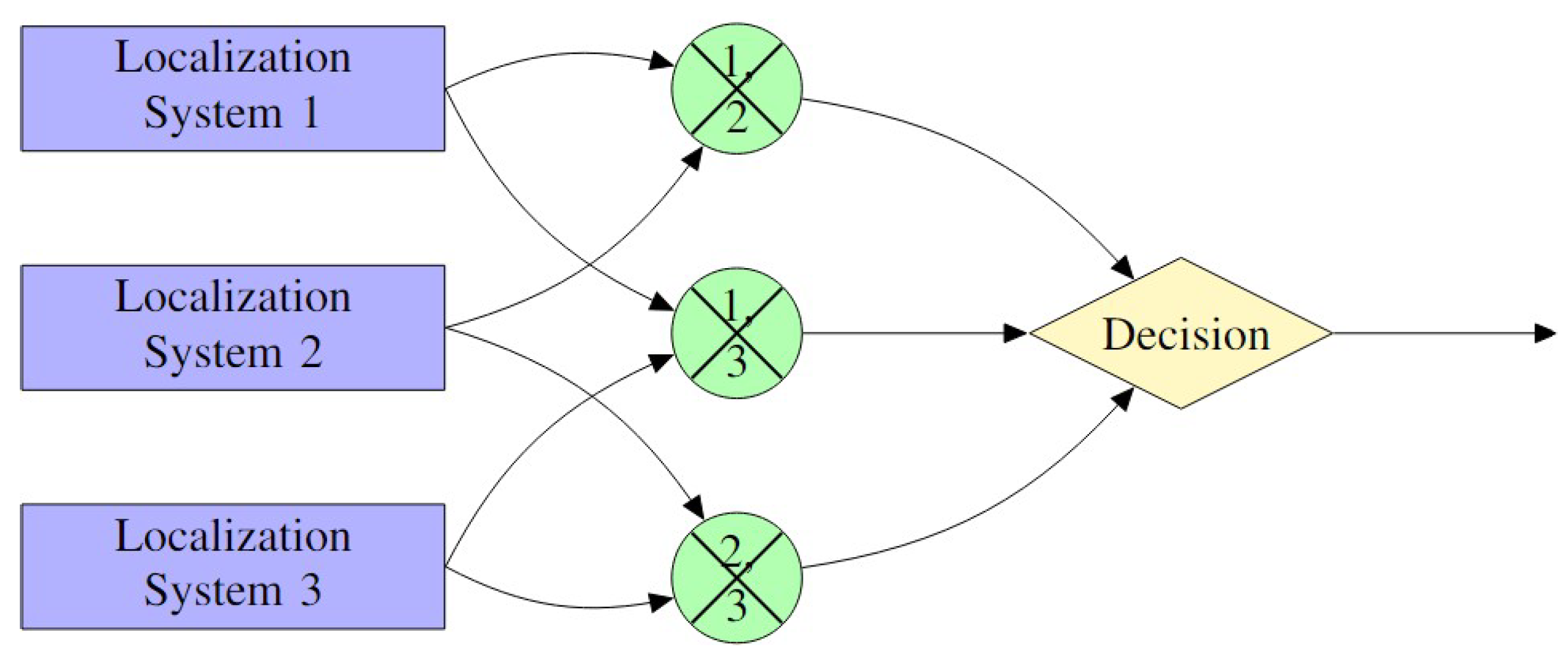

Extensive literature analysis reveals two possible main categories of FDE techniques: model-based and coherence-based approaches. Model-based techniques,

Figure 10, utilize mathematical models to predict the system’s behavior, identifying deviations as potential faults. Coherence-based techniques,

Figure 11, leverage the consistency among various sensors or measurements of the same quantity, flagging incoherent data points as potential faults.

The following sections explore each category in detail, including methods for computing the protection level. We will use some illustrative figures from the reviewed references. Not all figures will be included; only those that help clarify the process will be selected.

6. Model-Based FDE

In the field of FDE in localization and navigation systems, Model-Based FDE, or MB-FDE, is a vital component, providing reliable solutions through the use of predictive models of system behavior, see

Figure 10. These predictive models could be sensor models, system models, or machine learning models like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). MB-FDE techniques identifies discrepancies between expected and observed value to detect and exclude faulty data. In the process of this review, a wide range of techniques will be examined, each of which will provide special insights for improving the integrity and PL calculation.

Based on the surveyed paper, MB-FDE is further categorized into three types:

Post-processing MB-FDE

Pre-processing MB-FDE

Simultaneous MB-FDE

6.1. Post-Processing MD-FDE

In the post-processing scheme, detection and exclusion occur after the system state is computed, such as the pose. First, the localization algorithm performs data fusion, Bayesian updates, or optimization. Then, faults or outliers are detected. This means measurements are used as they are, known as the sensor level, and fault detection happens at the system level, like the state or pose. Therefore, detection of faults or outliers happens after the localization processing is complete, see

Figure 12. The following provides an in-depth review of post-processing FDE methods found in the literature.

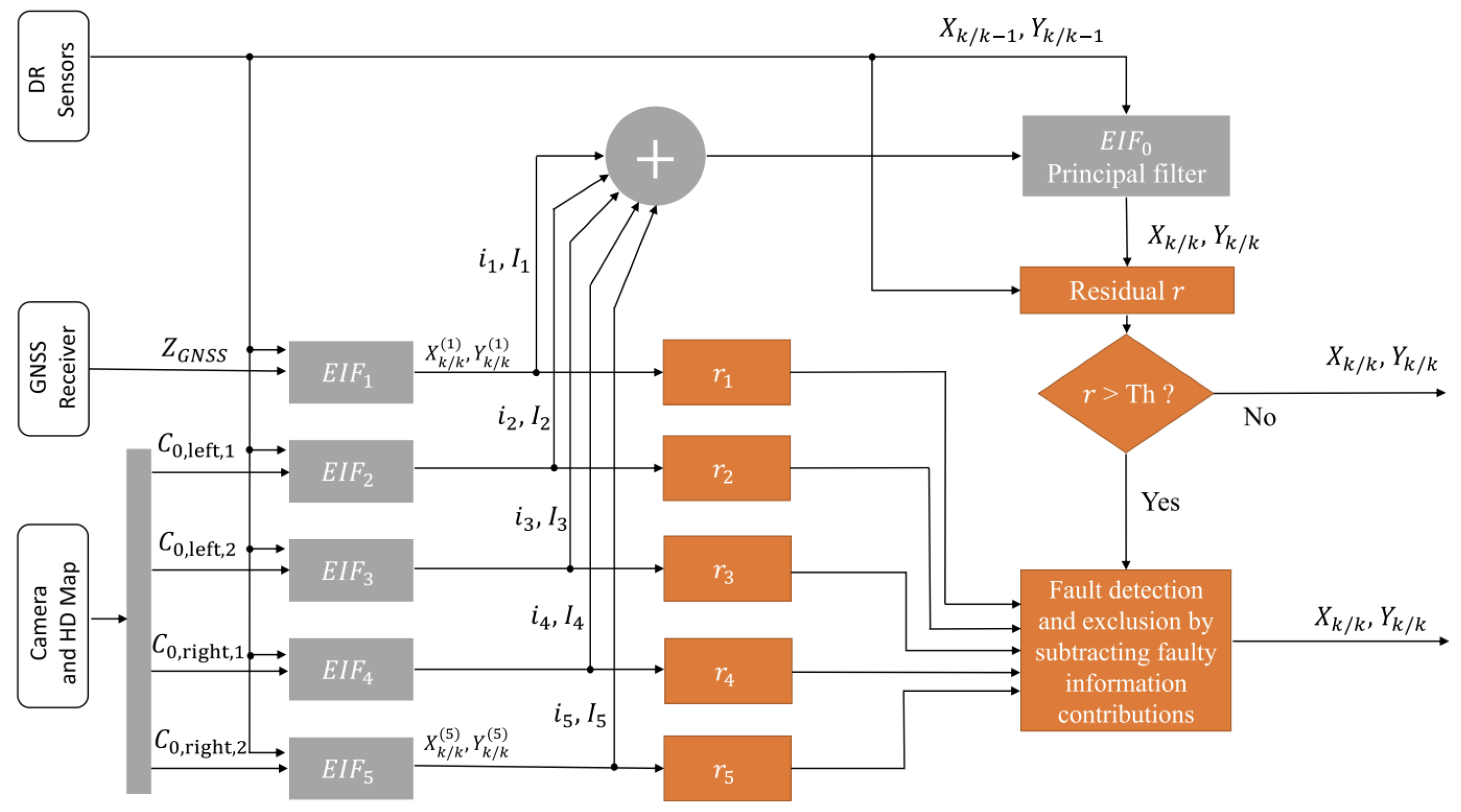

In [

26,

27,

28], an Extended Information Kalman Filter (EIF) is introduced. Banks of EIFs estimate the state using sensors like GNSS, camera, and odometry. Each filter’s output is compared to a main filter that combines, fuse, all outputs. Residuals, calculated as the Mahalanobis distance, used to identify and exclude deviant filters and their sensor data.

PL is calculated by over-bounding the EIF error covariance with a Student’s t-distribution. The degree of freedom for this distribution is adjusted offline during a training phase. However, this method has limitations. It assumes Gaussian noise, which doesn’t accurately represent noise during faults or outliers. The thresholding also depends on this assumption, using Mahalanobis distance compared to a Chi-square distribution. Additionally, the PL calculation is adjusted offline to find the best degree of freedom for the t-distribution for a specific trajectory or scenario.

In [

41], a Student

t-distribution EIF (t-EIF) is utilized, akin to [

26,

27,

28], but with different residual generation methods. Instead of Mahalanobis distance, it employs Kullback-Leibler Divergence (KLD) between updated and predicted distributions. Residual values adaptively adjust the

t-distribution’s degree of freedom, enhancing robustness against outliers. Larger residuals indicate noisy measurements, necessitating thicker tails and lower degrees of freedom, while smaller residuals justify higher degrees of freedom. This adaptation is governed by a negative exponential model, ensuring flexibility and optimization for various measurement conditions. PL calculation depends on degrees of freedom at the prediction and update steps. Errors are adjusted based on the minimum degrees of freedom between these steps. The final PL formula mirrors that of [

26,

27,

28].

Figure 13 shows a general diagram of how the EIF is applied for FDE.

A multirobot system with an FDE step is addressed in [

57]. The approach utilizes an EIF-based multisensor fusion system. The Global Kullback-Leibler Divergence (GKLD) between the a priori and a posteriori distributions of the EIF is computed as a residual. This residual, dependent on mean and covariance matrices, is utilized to detect and exclude faults from the fusion process. First, the GKLD is used to detect faults. Next, an EIF bank is designed to exclude faulty observations. The Kullback-Leibler Criterion (KLC) is then used to optimize thresholds in order to achieve the optimal false alarm and detection probability.

In [

58], a multirobot system uses EIF for localization. Each robot performs local fault detection based on its updated and predicted states. The Jensen-Shannon divergence (JSD) applied to generate the residuals between distributions. Fault detection thresholds are set using the Youden index from ROC curves. When a fault is detected, JSD is computed for predictions versus corrections from Gyro, MarvelMind, and LiDAR. Residuals are categorized based on their sensitivity to different error types and errors from nearby vehicles. If thresholds are exceeded, residuals are activated using a signature matrix, which helps detect and exclude faults and detects simultaneous errors. Faulty measurements are then removed from the fusion process.

In [

52,

56], the setup is extended with a new FDE approach and batch covariance intersection informational filter (B-CIIF). Fault detection and exclusion are based on JSD between predicted and updated states from all sensors.

In [

52], a decision tree is employed for fault detection, while a random forest classifier is used for fault exclusion. Both methods use JSD residuals and a prior probability of the no-fault hypothesis for training. In contrast, [

56] employs two Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP) models. One for fault detection and the other for fault exclusion. The input to the MLPs includes residuals and the prior probability of the no-fault hypothesis. Training data for these machine learning techniques includes various fault categories like gyroscope drift, encoder data accumulation, Marvelmind data bias, and LiDAR errors. However, the limitation of generalizability remains significant. Since the training data is specific to certain scenarios, the models may struggle to detect and address faults in new or unfamiliar environments. This limitation can compromise the overall reliability and integrity of the system when deployed beyond the scope of the training data.

6.2. Pre-Processing MB-FDE

In the preprocessing scheme, fault detection happens at the sensor level. Sensor measurements, such as from LiDAR, cameras, odometry, or GNSS, are first checked for faults or outliers. This means faults are detected and excluded before the data is used in the localization system, whether it involves fusion, Bayesian updates, or optimization, see

Figure 14. An in-depth review of pre-processing FDE methods from the literature is presented next.

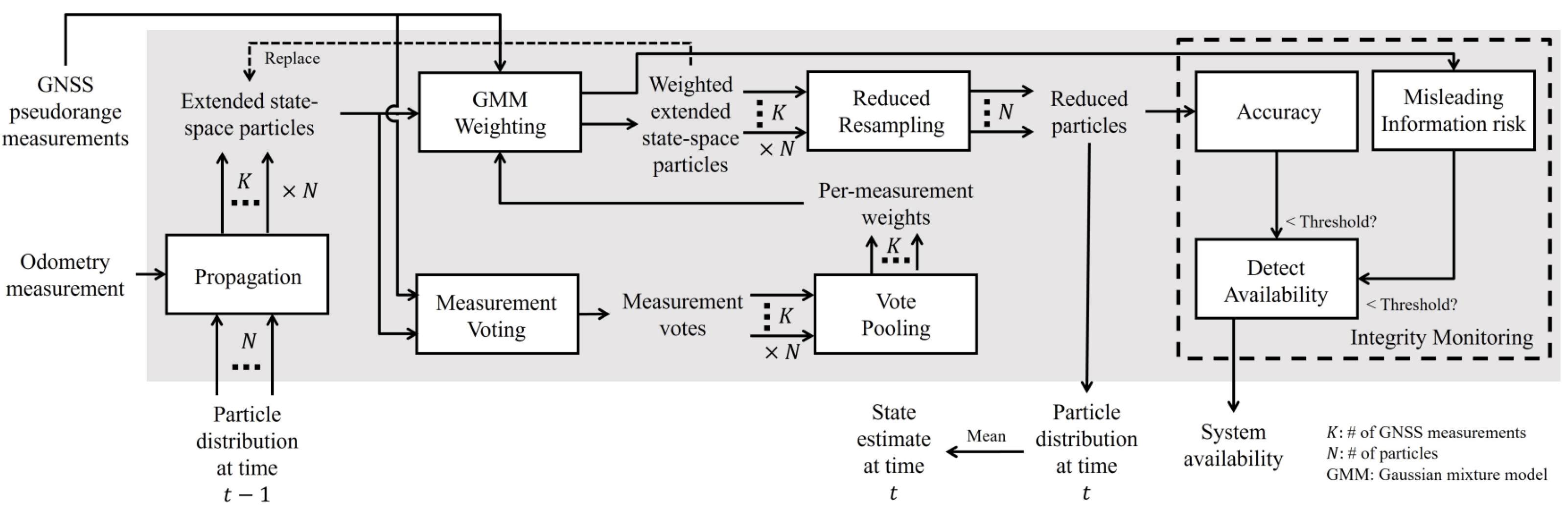

In GNSS systems, [

42] presents a method to reduce residuals between predicted and measured pseudo-range data from satellites. They use a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) to handle errors that have multiple modes. Instead of a single linearization point, they use a distribution over this point, managed by a particle filter. Each particle has a vector indicating the weight from each satellite. The particle with the highest total weight is favored, this is called the voting step. This method relies on data from multiple satellites and GNSS receiver correlations over time. If any data is missing, the method’s accuracy declines. Integrity is measured by calculating the likelihood that the estimated pose exceeds the AL region.

Figure 15 illustrates the framework adopted in this work.

Integrity is assessed using two metrics: hazardous operation risk and accuracy. Accuracy measures the probability that the estimated pose is outside the AL, while hazardous operation risk examine if the estimated position has at least a probability of containing the true position. An alarm is triggered if either metric exceeds a set threshold, indicating a loss of integrity.

In [

32,

33], a vision-based localization system enhances ORB-SLAM2 with FDE techniques. It uses a parity space test to detect faults, addressing one fault at a time by comparing expected and observed measurements. Faulty features are removed iteratively until the error hits a threshold. An adaptive residual error calculation accounts for uncertainties. The modular design allows easy integration with existing SLAM techniques. PL considers noise from observations and maximum deviation from undetected faults, calculated as a weighted sum of covariance elements. Improved covariance matrix elements boost computation accuracy by removing inaccurate features or outliers iteratively. A threshold ensures a sufficient number of inliers for SLAM operations; if not met, the location estimate is deemed unsafe.

The technique used for FDE in the image-based navigation system described in [

31] is similar to that of GPS RAIM [

59,

60,

61], which is based on performing a parity test for FDE as in [

32,

33]. PL is calculated based on the maximum slope of the worst-case failure model, similar to concepts discussed in in[

43,

44]. The author of this work uses a feature-based tracking method for localization.

[

37,

38] present a method to reduce errors by treating GNSS and odometry data separately. They improve state estimation by using trajectory monitoring and a short-term memory buffer instead of relying on the standard Markovian assumption. Their technique estimates states over a finite horizon and uses sensor residuals and variances to weight GNSS and odometry data.

For fault detection, they calculate sensor residuals, squared errors, and variances. They then weight GNSS and odometry data based on the ratio of each residual to its standard deviation. A Chi-square distribution threshold used for detecting faults. The sensor with the highest weight is prioritized for exclusion.

This approach relies on hyperparameters for its operation. These include the misdetection probability for the protection level calculation and the Chi-square distribution for fault detection. Additionally, the size of the state buffer is a hyperparameter that should be selected based on the environment and scenario.

The technique presented in [

36] is customized for FDE in real-time within LiDAR mapping and odometry algorithms. This technique uses a feature-based sensor model to compute the mean and variance of the latest

k innovations for the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) setting. This technique adaptively establishes a threshold for fault detection by using the Chi-square distribution. Thus, the technique can adapt to environmental changes and sensor conditions. Feature-based FDE technique, dynamic thresholding, and real-time noise estimates are combined in this technique to effectively detect and exclude faults in LiDAR odometry and mapping algorithms. The technique lacks a particular formula for estimating the protection level. Its integrity is, however, evaluated by analyzing critical parameters, including error boundaries, missed detection rate, and false alarm rate. Among these parameters, the error bound stands out as a critical signal for integrity assessment, showing the maximum possible pose error.

In [

45], each sensor’s output is evaluated using Hotelling’s

test, based on expected sensor output and covariance. This allows for accurate fault detection by examining the correlation within the same sensor’s data. By employing the Student

t-distribution to overbound measurement noise and measurement innovation sample covariance to inflate it, where measurement noise is adaptively updated. The adaptive updating of the measurement noise covariance is similar to [

36]. It takes into account faults and other outliers adaptively. This application uses a UKF localization-based methodology.

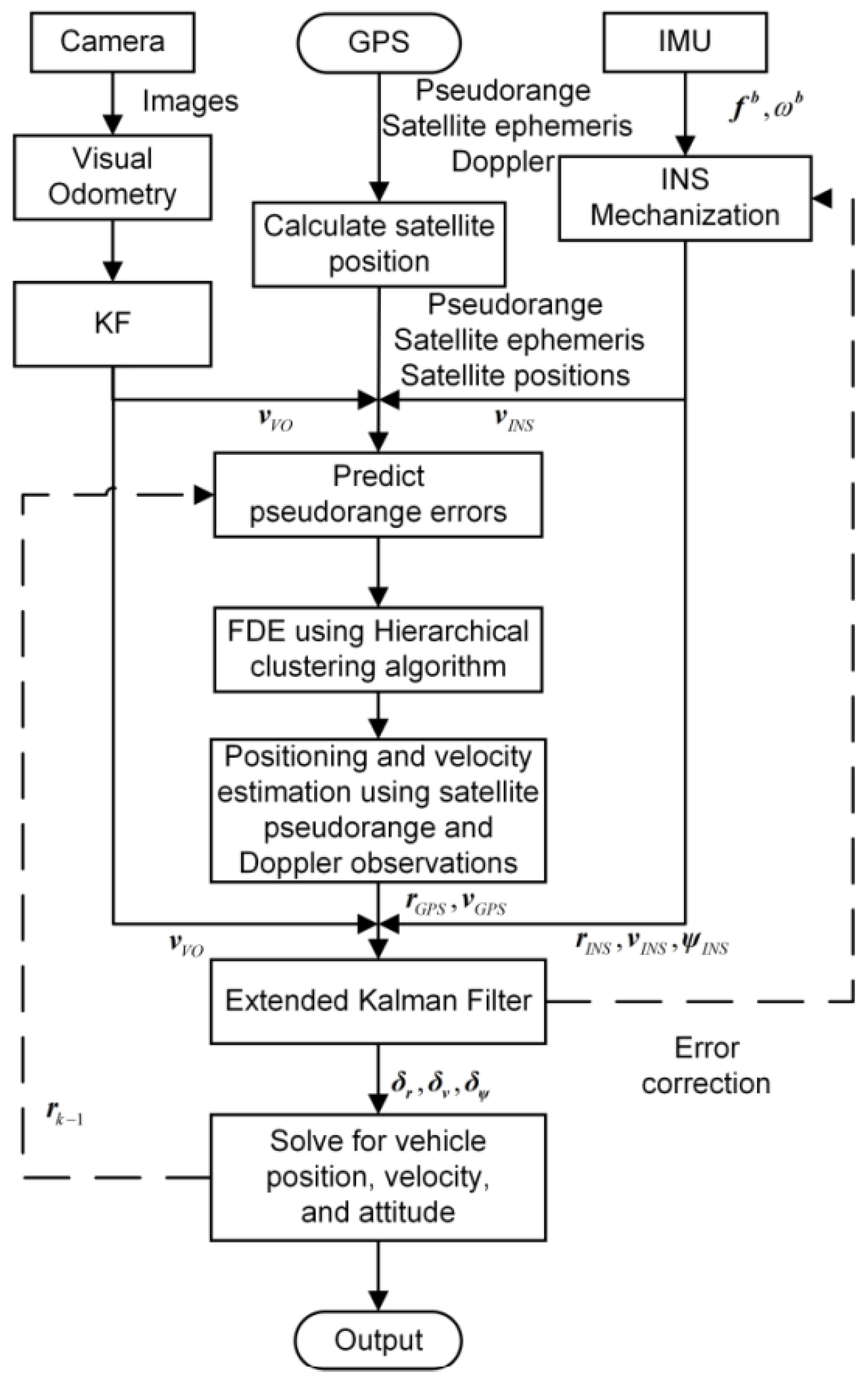

The method in [

51] uses raw GNSS measurements for FDE, see

Figure 16. Vehicle pose is predicted using IMU and Visual Odometry (VO). The error between this prediction and the GPS receiver pose estimate is computed. FDE is implemented using Hierarchical Clustering [

62] to detect and exclude faulty satellite signals. Satellites are divided into three clusters based on estimated errors: multi-path, Non-Line of Sight (NLOS), and Line of Sight (LOS) without errors. Initially, each satellite signal is considered a cluster, which is then clustered based on similarity. The three resulting clusters represent the main types of GPS errors. The LOS cluster, presumed to have the most samples, is used to compare expected pseudo-range errors. If this error exceeds a preset threshold, the associated satellite is excluded. The remaining measurements are used to calculate the GPS receiver’s position and velocity. However, selecting and adjusting thresholds lacks standardization, and the method to calculate the threshold in [

51] is not specified.

6.3. Simultaneous MB-FDE

In the simultaneous FDE scheme, fault detection is integrated into the real-time processing of sensor data during localization, such as in SLAM-Based localization. As sensor data is collected, it is immediately checked for faults or outliers, often using a weighting or selection method, before being used for localization. This means that the system continuously adjusts how each measurement affects the final output, such as the pose. For example, if a sensor reading is found to be unreliable, it is down-weighted or ignored during the data fusion or optimization steps. Unlike preprocessing or post-processing methods, which handle faults before or after main processing, simultaneous FDE handles faults dynamically as data is processed, see

Figure 17. Next, a detailed examination of simultaneous FDE methods in the literature is provided.

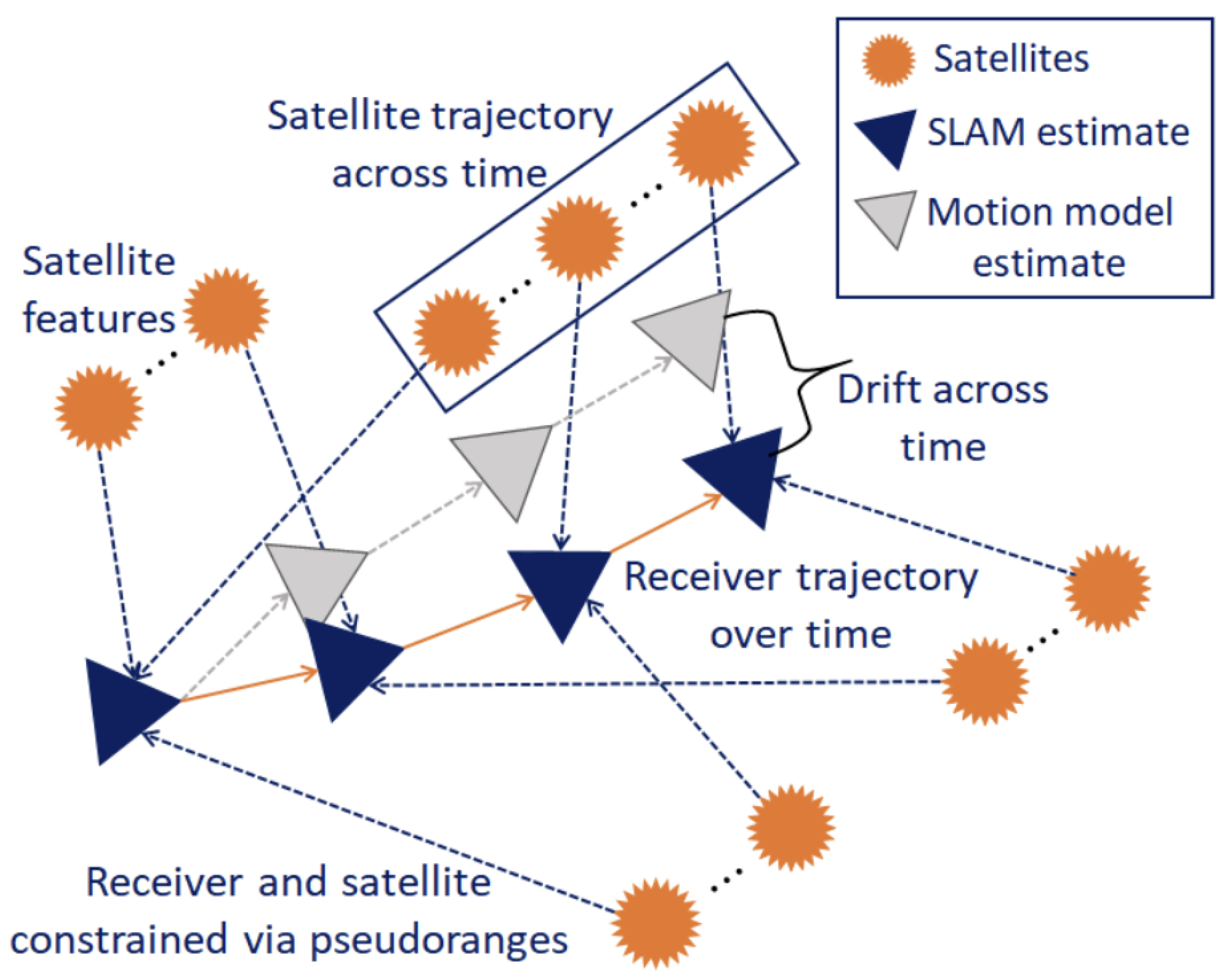

A GraphSLAM-based FDE technique is used in [

63]. GPS satellites are treated as 3D landmarks by combining GPS data with the vehicle motion model in the GraphSLAM framework, see

Figure 18. The algorithm creates a factor graph using pseudo-ranges, a motion model, and broadcast signals. The difference between predicted and measured pseudo-ranges is used to compute residuals, which are weighted in the graph optimization to detect and reject faulty measurements. The sample mean and covariance of these residuals form an empirical Gaussian distribution, used for FDE. New residuals must fall within a

region of this distribution to update the mean and covariance. The algorithm iteratively localizes the vehicle and satellites, eliminating faulty measurements, and updates the 3D map through local and global optimization steps.

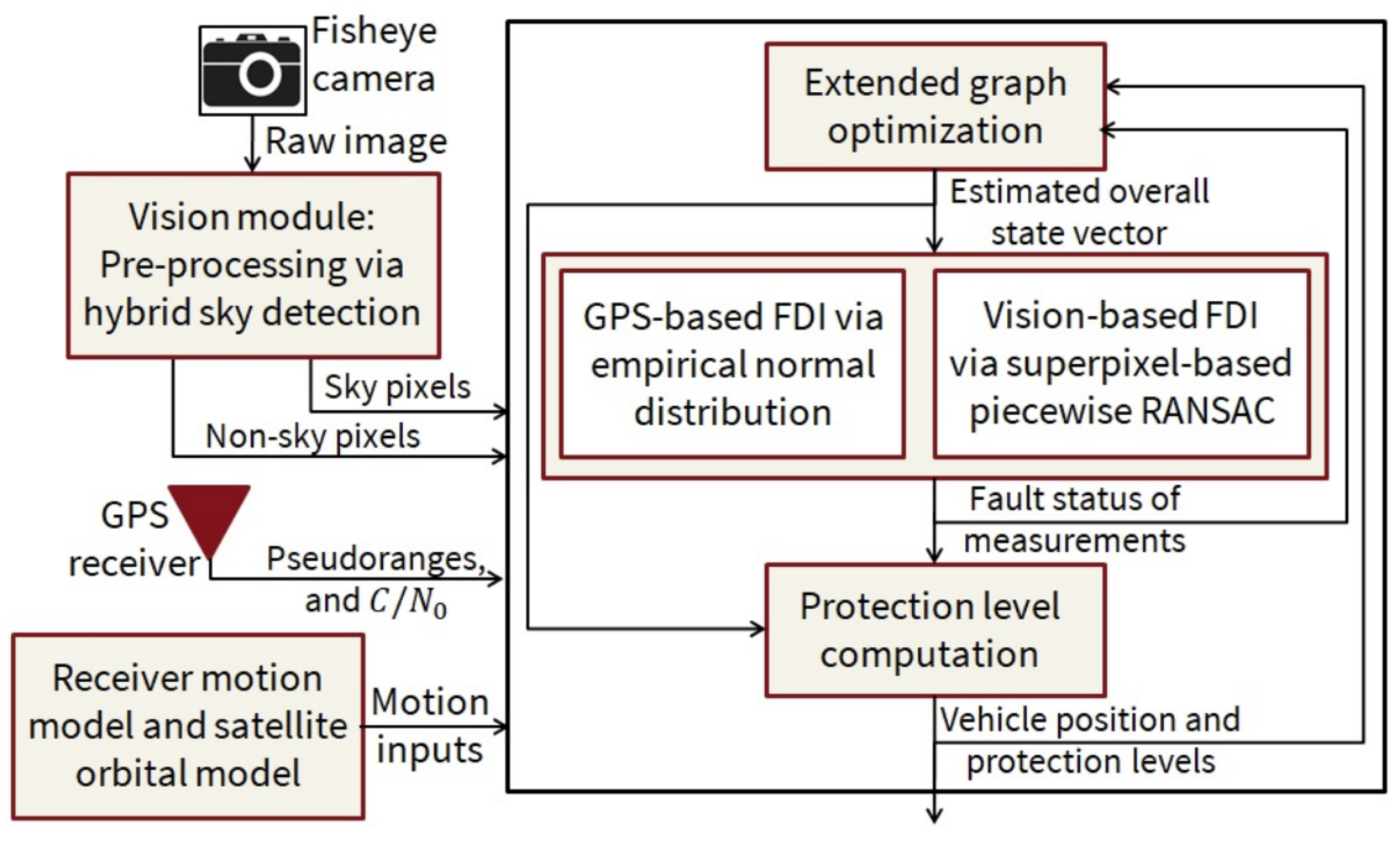

Building on the previous technique, the authors of [

43,

44] combine GPS and visual data for integrity monitoring in a GraphSLAM framework. They use GPS pseudoranges, vision pixel intensities, vehicle motion models, and satellite ephemeris to construct a factor graph. Temporal analysis of GPS residuals and spatial analysis of vision data are performed. Superpixel-based intensity segmentation [

64,

65], using RANSAC [

66,

67], labels pixels as sky or non-sky to remove vision faults. Residuals for all inputs are included in the graph optimization, with weights to detect faults and/or outliers. GPS FDE relies on temporal correlation, while vision FDE uses spatial correlation. A batch test statistic, the sum of weighted squared residuals, is computed to assess integrity. This statistic follows a Chi-squared distribution, and the protection level is calculated using the non-centrality parameter and the worst-case failure mode slope. This approach is illustrated in

Figure 19.

The method in [

48] enhances system integrity by estimating both the robot’s position and its reliability. According to [

48], reliability is defined as the probability that the estimated pose error falls within an acceptable range. A modified CNN from [

68] identifies localization failures by learning from successful and failed localizations. It converts CNN output into a probabilistic distribution using a Beta distribution [

69], based on a reliability variable.

The conventional Dynamics Bayesian Network (DBN) model is updated with two new variables,

Figure 20: the reliability variable and the CNN output. The DBN uses a Rao-Blackwellized Particle Filter (RBPF) to estimate both reliability and position. Over time, the reliability variable decays if no observations are made. To improve efficiency, [

49] introduces a Likelihood-Field Model (LFM) for calculating particle likelihoods. The CNN output uses a sigmoid function to indicate localization success. Positive and negative decisions are modeled with Beta and uniform distributions, respectively, with constants optimized experimentally.

Despite the LFM’s efficiency benefits, it may reduce data representation, affecting failure detection accuracy. The method also faces challenges due to the computational demands of visual data analysis. Domain-specific knowledge and computational resources are needed to determine the constants for optimal performance.

In [

50], a more advanced method extends pose and reliability estimation by incorporating observed sensor measurements’ class. This approach includes three latent variables: localization state (successful or failed), measurement class (mapped or unmapped), and vehicle state. A modified LFM is used for observation sensors, and the proposed model integrates information about observed obstacles using conditional class probability [

70].

In contrast to the previous methods [

48,

49], which employed a CNN to make decisions, this strategy uses a basic classifier based on the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of the residual errors. The residual is the difference between the observed beams and the closest obstacle in the occupancy grid map. The final decision is computed using a threshold. This method includes both global localization using the free-space feature proposed in [

71] and local pose tracking using the MCL presented in [

55]. As such, it can perform relocalization due to pose tracking failure. The method in [

72] is used to fuse the local and global localization approaches via importance Importance Sampling (IS).

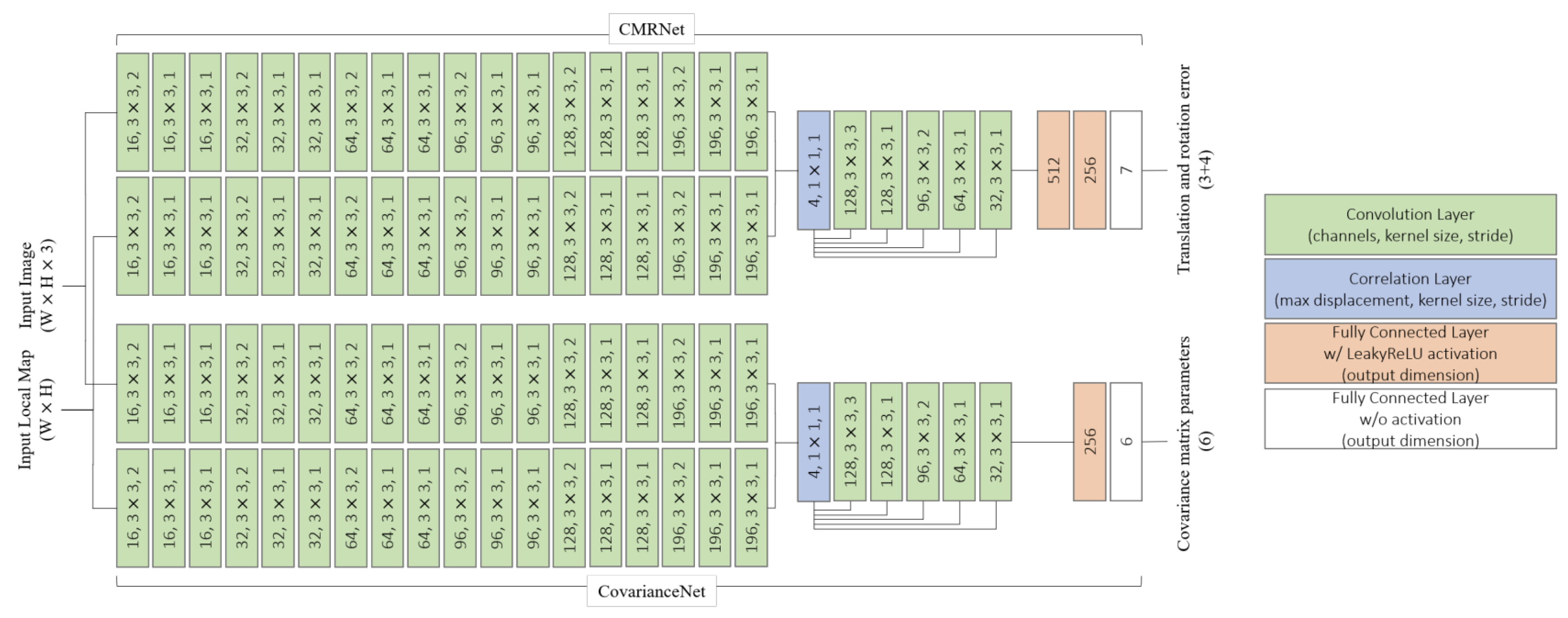

In [

40,

46], a method is proposed to enhance camera-based localization in GNSS-limited areas by improving PL calculations. The approach leverages CNNs and 3D point cloud maps from LiDAR to estimate location error distributions, capturing both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties [

73,

74].

The CNN has two components,

Figure 21: one estimates position error, and the other calculates covariance matrix parameters. It uses CMRNet [

75] with correlation layers [

76] for error estimation, and a model similar to [

77] for covariance.

To handle CNN fragility, the method applies outlier weighting using robust Z-scores. A GMM is built from weighted error samples to represent position errors and calculate PL from the GMM’s cumulative distribution function.

However, the method’s effectiveness is limited by the need for large, high-quality training datasets, which can be labor-intensive and affect accuracy due to variability in input data and dataset quality.

6.4. Model-Based FDE Methods: Summary and Insights

MB-FDE algorithms are promising for fault handling in localization systems but face scalability and reliability challenges. The reliance on correct sensor data, as well as the assumption of specific noise distributions, may limit their application in real-world scenarios with a wide range of environments and sensors. Practical implementation is further complicated by the computational complexity of analyzing several failure hypotheses and the combinatorial explosion in the number of measurements. Furthermore, the efficiency of these strategies is strongly reliant on the proper modeling of temporal and spatial correlations, which is not always simple or precise. Overall, while these FDE techniques are significant advances in maintaining the integrity of localization systems, more research is needed to overcome their shortcomings and increase their robustness in a variety of operating environments.

7. Coherence-Based Techniques

These techniques use the consistency of data from various sensors or localization systems to perform FDE. Fundamentally, coherence-based FDE, or CB-FDE, techniques take advantage of the idea that, in typical operational environments, several estimates of the same quantity should show coherence or agreement. These estimates can be acquired by different sensors, systems, or algorithms. Usually, the coherency check is carried out by weighing the estimates from each source and accepting the set of estimates that satisfy a threshold test. Alternatively, a test between each pair of estimate sources can be performed to check for inconsistencies. This in-depth analysis will examine a wide range of algorithms and approaches, each providing unique perspectives and techniques for identifying and eliminating faults.

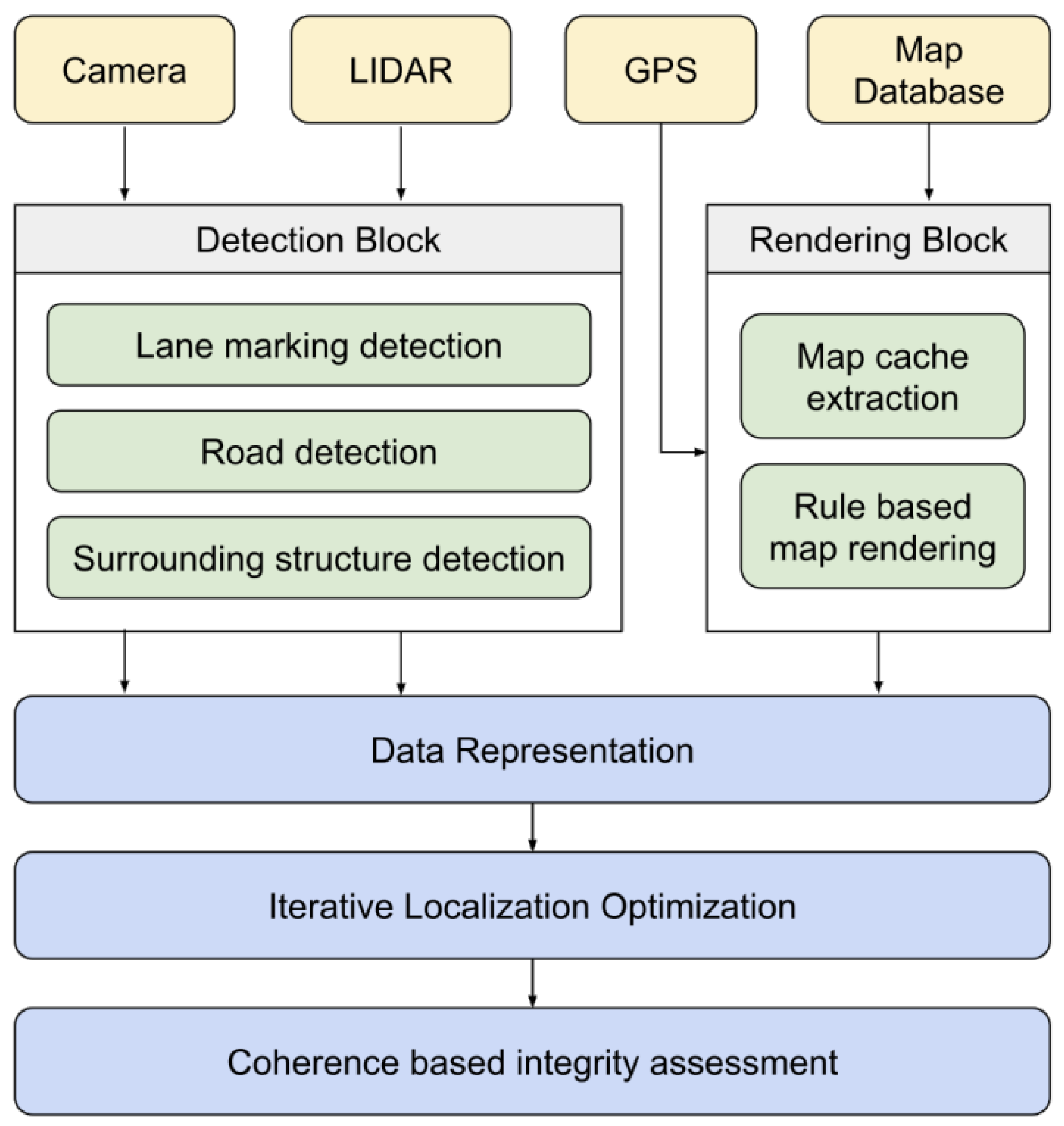

An innovative approach for detecting localization failures is introduced by [

78]. It examines the coherency between sensor readings and the map by analyzing latent variables. The model uses Markov Random Fields (MRF) [

79,

80] with fully connected latent variables [

81] to find misalignments. These latent variables can be aligned, misaligned, or unknown, based on residual errors between measurements and the map.

The method integrates with the localization module and uses the 3D Normal Distribution Transform (3D-NDT) scan-matching technique [

82,

83]. It estimates the posterior distribution of latent variables from residual errors and applies a probabilistic likelihood model. The model includes a hyperparameter and selection bias. Failure probability is approximated using sample-based methods, though the precision of this approximation is not verified. The model’s multimodality, due to latent variables, may not capture all possible outcomes. The technique from [

34] integrates data from LiDAR, cameras, and maps into a unified model, as shown in

Figure 22. It maintains data consistency through redundancy and weighting. The method aligns sensor data with map data using GPS positions. A Feature Grid (FG) is used to label physical areas and assign weights based on distance. This FG model overcomes limitations of traditional geometrical models by representing different features with labels and evaluating coherence between feature grids, see

Figure 23.

The particle filter from [

84] is adapted for map matching, creating a uniform integrity testing framework. This approach avoids specific thresholds and does not rely on particular error noise models. The PL, including the Horizontal Protection Level (HPL), is calculated using the variances of particle distributions from sensor combinations, focusing on average standard deviation.

The technique in [

85] uses multiple localization systems to detect and recover from faults. It combines an EKF with a Cumulative Sum (CUSUM) test [

86] to detect faults and estimate the time when they occur. The EKF tracks outputs from various systems, comparing them to find deviations. The CUSUM test helps reduce false alarms by monitoring these deviations. When a fault is detected, the system uses stored sensor data for position estimation based on the fault time. This method does not need a specific fault model, simplifying implementation. However, it lacks the ability to exclude faults and relies on assumptions about system consistency, which may lead to false alarms or missed detections.

The approach in [

87] uses EKF for sensor fusion in SLAM. It integrates multiple sensors, including MarvelMind for localization, gyroscopes, encoders, and LiDAR, with two EKFs: EKF-SLAM1 processes encoder and LiDAR data, while EKF-SLAM2 handles encoder and gyro data. Faults are detected by comparing Euclidean distances between EKF positions and MarvelMind data against a threshold. A large residual indicates a fault if it exceeds this threshold. Faults are identified by specific residual subsets, simplifying fault exclusion in sensors like gyroscopes and indoor GPS. When both encoder and laser rangefinder fail, angular velocities are compared to find the faulty sensor. This method requires a global position estimate from MarvelMind to function correctly.

Research by [

35] introduces a method for enhancing fault tolerance in multisensor data fusion systems. It uses two separate data fusion systems to ensure that only one fault occurs at a time. When a fault is detected, the system compares outputs from duplicated sensors and data fusion blocks. It measures the Euclidean distance between two EKF outputs and checks it against a preset threshold. If the distance is too high, it indicates a fault. The process involves two steps: comparing residuals and sensor outputs. Hardware faults are identified by comparing sensor outputs, while faulty localization systems are detected through residual comparison. The system recovers by using error-free localization values. However, setting detection thresholds can be expensive and context-specific.

In [

88], a combined approach of model-based and hardware redundancy addresses drift-like failures in wheels and sensors. Model-based redundancy uses a mathematical model to mimic component behavior. The technique employs a bank of EKF and three gyroscopes, each assigned to specific faults, producing distinct residual signatures for fault detection. Residuals are used to identify faults in wheels, encoders, and gyroscopes. A fault is flagged if the residual exceeds three times its standard deviation for a set number of times. Simulations demonstrate the technique’s effectiveness in detecting sensor and actuator failures. However, the initial thresholds for fault detection, based on the three-sigma rule, do not adapt well to varying conditions. This can lead to false alarms or missed detections, affecting the system’s accuracy in dynamic environments.

In [

89], a process model predicts the initial pose by integrating data from stereoscopic systems, LiDAR, and GPS for vehicle localization. GPS provides the absolute position, while stereoscopic systems and LiDAR estimate ego-motion. The method uses the extended Normalized Innovation Squared (NIS) test to ensure sensor coherence before data fusion. Faulty sensor observations are removed before integration. LiDAR accuracy is improved with Iterative Closest Point (ICP) and outlier rejection. Sensor coherence is checked using the extended NIS test. An Unscented Information Filter (UIF) integrates data from multiple sensors, minimizing error accumulation. Parity relations [

90], calculated with Mahalanobis distance, help detect faults.

However, this method assumes only one fault occurs at a time, which may not reflect real-world scenarios. It also assumes Gaussian sensor readings, which may not be accurate in complex situations. Moreover, the Gaussian assumption may not handle noise or outliers efficiently, potentially leading to incorrect fault detection. Accurate sensor modeling and calibration are challenging, and computational costs increase with more sensors.

In [

91,

92], the maximum consensus algorithm localizes the vehicle. [

91] uses LiDAR data, while [

92] converts 3D LiDAR point clouds into 2D images. An approximate pose is aligned with a georeferenced map point cloud. The search for the vehicle’s position is limited to a predefined range, ensuring the true position is within it. Candidate positions are discretized, and a consensus set is created for each cell by counting matches between map points and sensor scan points, using a distance threshold and classical ICP cost function [

93,

94,

95,

96].

An exhaustive search finds the global optimum by identifying the transformation with the highest consensus. Despite the exponential cost with more dimensions, the search becomes constant with fixed dimensions. The algorithm covers the entire objective function distribution, and parallel processing is facilitated by simple count operations. Real-time applications benefit from discrete optimization techniques like branch-and-bound [

97,

98], which speed up computations.

However, [

91,

92] have limitations due to its simplistic counting approach. It does not fully account for the importance of correspondences in vehicle pose estimation, especially in urban environments where most matches are from the ground and facades. [

92] introduces a new objective function that uses normal vectors for point-to-surface matching, improving constraints, especially longitudinally. Errors are measured using the covariance matrix of position parameters, with a smaller trace

1 indicating fewer errors. Helmert’s point error, the inverse of the matrix trace, scores solution quality, guiding localization. The algorithm uses a physical beam model [

55] to create a probability grid from LiDAR data, defining the PL from grid cells with a probability

. A significant drawback is the grid-based search constraint, which limits precision to the resolution of the search space. Handling irregular point cloud distributions remains challenging, even with point-to-surface mapping.

7.1. Coherence-Based FDE Methods: Summary and Insights

CB-FDE techniques have a number of shortcomings. As the number of sources rises, scalability problems occur, and comparisons grow quadratically. For example, 10 sources require 45 comparisons, whereas 20 sources demand 190. This leads to increased computational complexity, making real-time problem detection difficult owing to processing delays. Additionally, these techniques rely on redundancy, which is less successful in systems with fewer sources because it requires multiple sources to provide the same value. Furthermore, as CB-FDE performs best with errors that consistently affect all sources, it is less effective with irregular error patterns.

Table 4 summarizes all MB-FDE methods and compares them using various criteria.

8. Robust Modeling and Optimization

FDE methods primarily focus on qualifying system integrity by detecting and managing faults and outliers. Qualification in this context means determining whether the system is functioning correctly by identifying when and where things go wrong. However, FDE methods often fall short in the quantification of integrity, which involves measuring the extent or impact of these faults. Without quantification, it is difficult to assess how errors affect the overall system performance. To address this gap, additional techniques, such as PL, are required to provide a numerical measure of system integrity.

Robust modeling and optimization techniques address both qualification and quantification. These methods do not depend on specific fault models; instead, they use general approaches to handle a wide variety of faults and noise. This allows for both a thorough assessment of whether the system is performing correctly (qualification) and a measurement of how well it is performing (quantification). By providing probabilistic interpretations of error distributions, robust methods give a more complete picture of system integrity.

In localization tasks, the common assumption that errors follow a Gaussian distribution often fails. This is not only because of linear approximations in algorithms like factor graphs and Bayesian methods, but also due to other factors such as the presence of unknown outlier distributions, see

Section 2.1.4.

These outliers can arise from various front-end [

100] processes involved in building the factor graph, such as:

Image or LiDAR Scan Matching Errors [

101,

102,

103]: In odometry, mismatches in image sequences or LiDAR scans can introduce significant outliers

Loop Closure Detection [

104]: In SLAM-based localization, incorrect identification of loop closures can distort the graph and lead to substantial errors

Erroneous Map Queries [

105,

106,

107]: In map-based localization, errors can occur during the process of querying the map, particularly in the absence of accurate GPS data.

Mapping Errors [

103,

108,

109,

110]: Outliers can also arise due to inaccuracies in the map itself, which may result from errors accumulated during the map generation process. These mapping errors can propagate through the system, leading to further mismatches during map matching and adding additional outliers.

These front-end issues, if not properly handled, can weaken both the qualification and quantification of system integrity.

Robust modeling techniques are particularly valuable in these scenarios because they can manage diverse sources of error without needing detailed models of every possible fault. Unlike traditional methods, robust algorithms dynamically adapt to uncertainties in real-time, which is crucial in complex, changing environments. These algorithms effectively mitigate the impact of various uncertainties, making them essential for both qualifying and quantifying system performance.

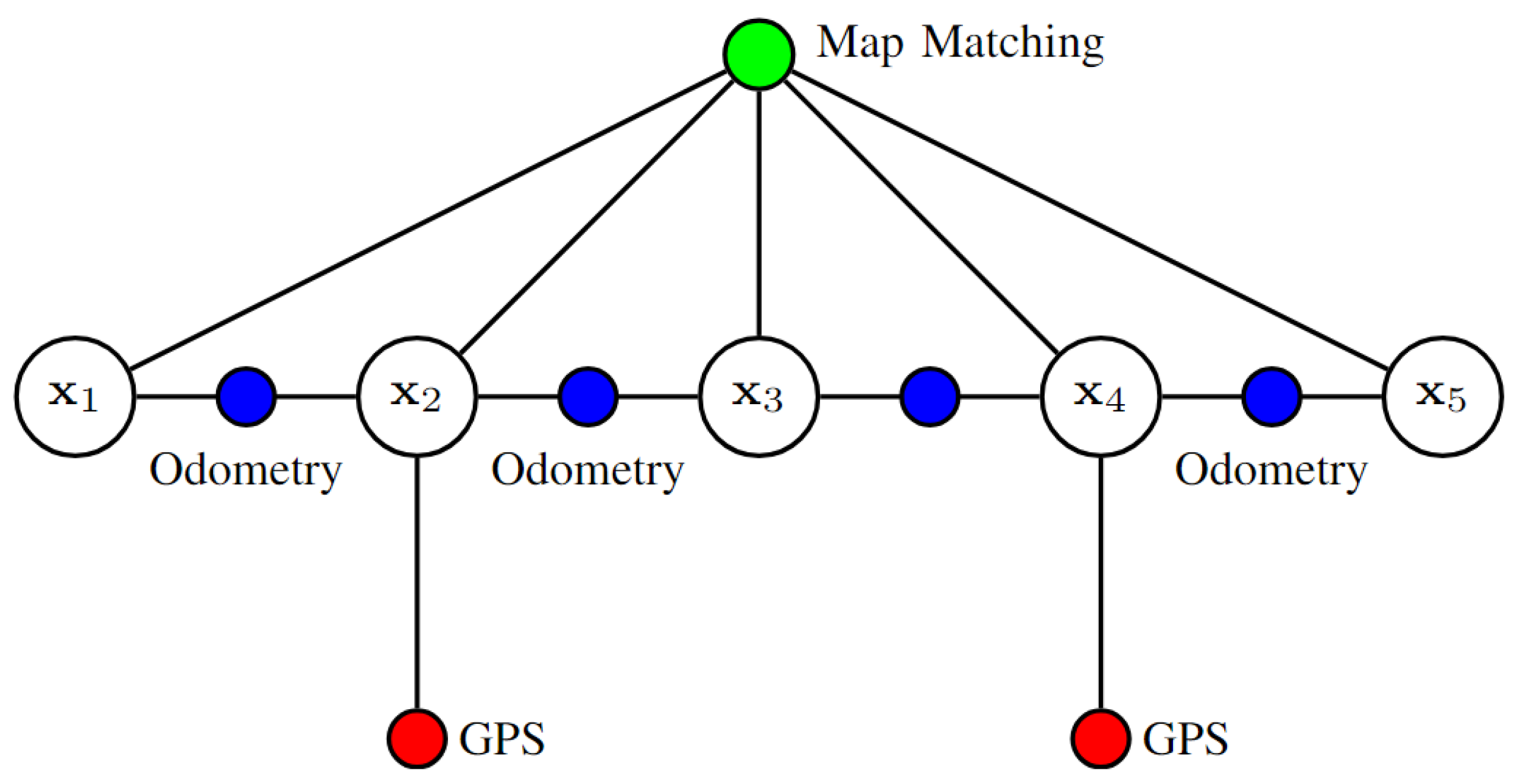

In localization, robust modeling is often applied using a factor graph model[

111,

112,

113], as shown in

Figure 24. In this model, a graph representation is adopted, where nodes correspond to different states or poses, and edges represent constraints between them. These constraints can come from various sources, such as:

Odometry: Using methods like ICP from image sequences or LiDAR scans, or motion models from IMU data

GPS: Providing positional constraints based on satellite data

Map Matching: Aligning sensor data with a known map

Landmarks Observations: Constraints from observing known landmarks

Calibration Parameters: Constraints related to sensor calibration

These constraints generate residuals, and the sum of these residuals represents the total energy or loss of the graph. The goal of optimization is to minimize this loss, thereby refining the graph’s configuration to best fit the sensory information. Factor graph optimization can be performed either online, as data is received, or offline, using a batch of data.

By addressing both the qualification and quantification of errors, robust modeling ensures that the system not only identifies faults but also accurately measures their impact, leading to a resilient and precise localization system. This approach is particularly crucial in environments where the quality of the sensor’s data can significantly influence the overall performance.

This section reviews the primary algorithms and techniques used to create robust localization algorithms.

8.1. Analysis of Robust Modeling and Optimization Techniques

Current localization methods often use least squares optimization but face challenges when dealing with outliers like data association errors and false positive loop closures.

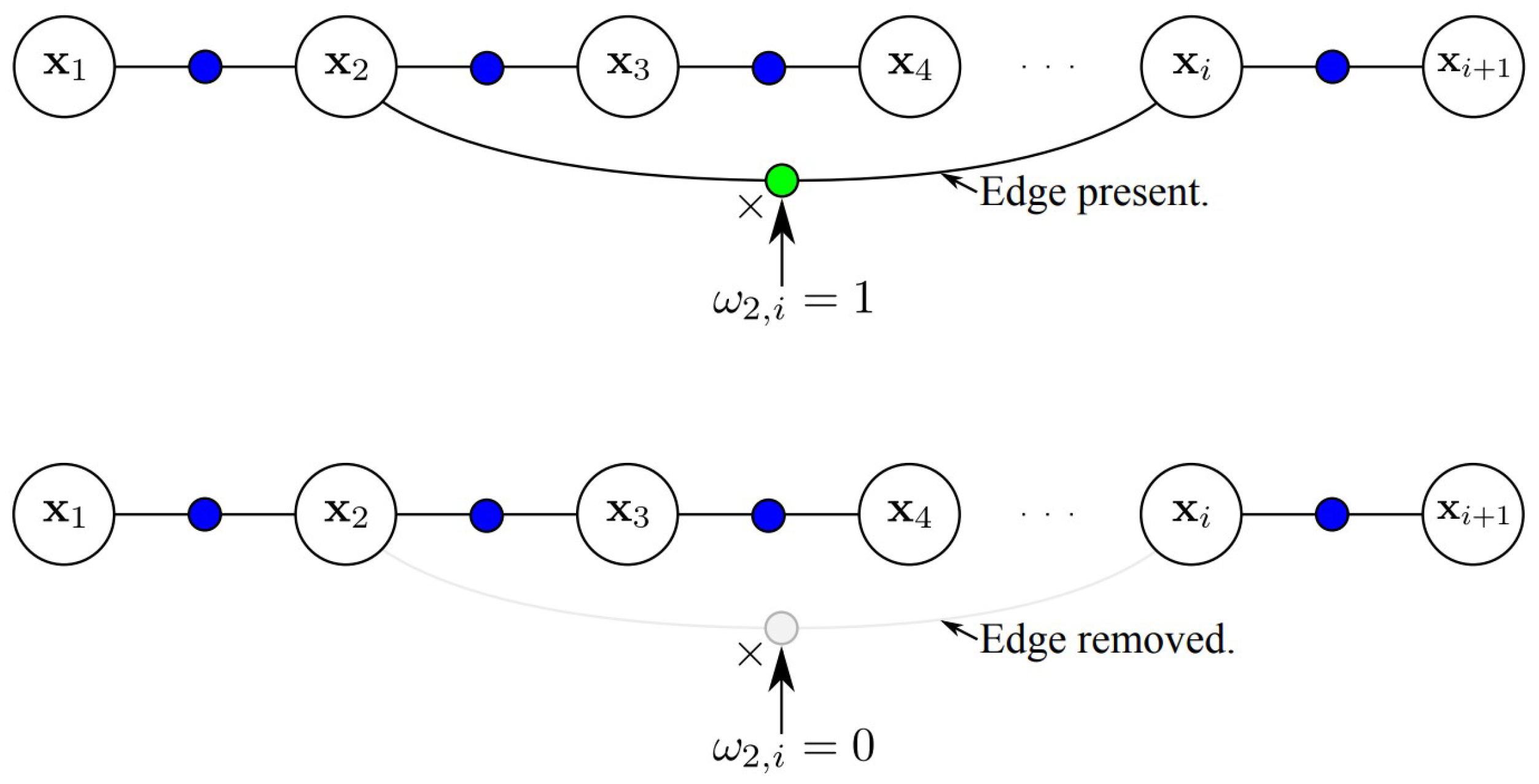

To address these issues, [

114] introduced a solution that improves the back-end optimization process. Instead of keeping the factor graph structure or topology fixed, this method allows the graph topology to change dynamically during optimization. This flexibility helps the system detect and reject outliers in real-time, making SLAM more robust. The method uses

switch variables, see

Figure 25, for each

potential outlier constraint or edge. These variables help the system decide which constraints to include or exclude based on their accuracy. Essentially, switch constraints (SC) act as adjustable weights for each factor in the factor graph. These weights are optimized along the map for SLAM [

114] and the pose for GNSS-based localization [

115,

116].

This approach is similar FDE because it automatically identifies and removes erroneous data associations or pseudo measurements, ensuring the system uses only reliable data [

114,

115,

116]. However, this approach introduced extra switch variables for each potential outlier, which increased both the computational cost and complexity of each iteration. As a result, the system could become less efficient and slower to converge.

In contrast, Dynamic Covariance Scaling (DCS) [

118,

119,

120,

121] offers a more efficient method for managing outliers in SLAM without adding extra computational load. DCS adjusts the covariance of constraints based on their error terms, changing the information matrix without needing additional variables. This makes the optimization process more efficient and speeds up convergence. The scaling function in DCS is determined analytically and is related to weight functions in

M-estimation [

122], which reduces the number of parameters to estimate compared to the SC approach, since DCS does not require iterative optimization of the scaling function.

The earlier methods using SC and DCS had challenges with tuning the scaling function based on error, and also required manual adjustment of parameters [

123]. The method in [

124] addresses this issue with self-tuning M-estimators. This approach directly adjusts the parameters of M-estimator cost functions, which simplifies the tuning process.

The self-tuning M-estimators method connects M-estimators with elliptical probability distributions, as introduced in [

124]. This means that M-estimators can be chosen based on the assumption that errors follow an elliptical distribution. The algorithm then automatically adjusts the parameters of the M-estimators during optimization, selecting the best one based on the data’s likelihood.

A broader approach to robust cost functions is introduced in [

125]. This method improves algorithm performance for tasks like clustering and registration by treating

robustness as a continuous parameter. The robust loss function in this framework can handle a wide range of probability distributions, including normal and Cauchy distributions, by using the negative log of a univariate density.

By incorporating robustness as a latent variable in a probabilistic framework, this approach automatically determines the appropriate level of robustness during optimization, which eliminates the need for manual tuning and provides a more flexible solution.

Building on this, [

126] presents a method that dynamically adjusts robust kernels based on the residual distribution during optimization. This dynamic tuning improves performance compared to static kernels and previous methods. The key difference from [

125] is that the new method covers a wider range of probability distributions by extending the robust parameter’s range. The shape of the robust kernel is controlled by a hyperparameter that adjusts in real-time, enhancing both performance and robustness.

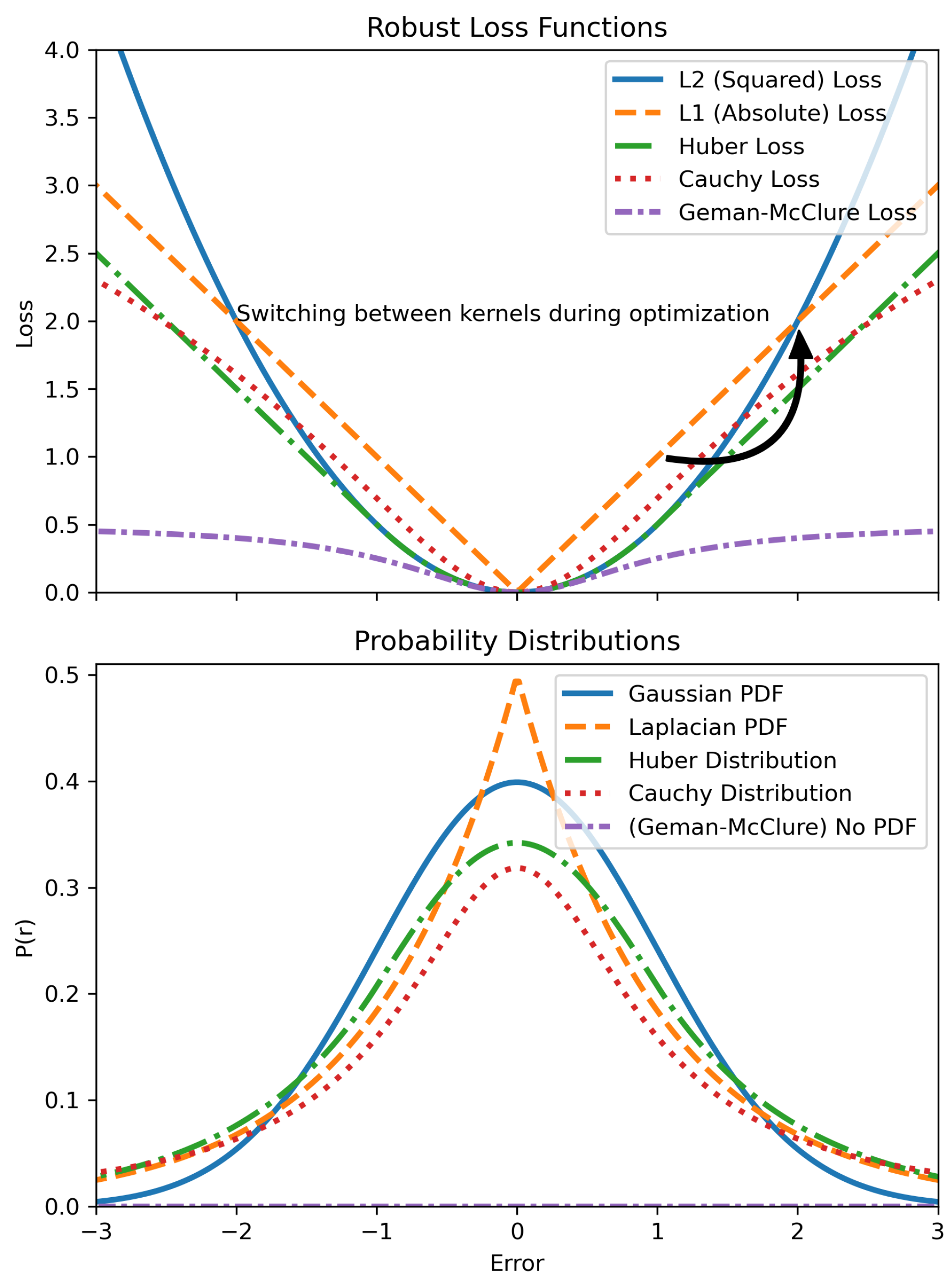

Figure 26 represents various robust kernels and the switching between them during optimization.

The switching between these kernels during optimization occurs due to the fact that robustness is modeled by an optimizable latent variable.

In contrast, [

127] introduces a probabilistic approach to improve convergence. This method fits the error distribution of a sensor fusion problem using a multimodal GMM. In real-time applications like GNSS localization, the adaptive mixing method adjusts to the actual error distribution and reduces reliance on prior knowledge. This approach effectively handles non-Gaussian measurements by accurately accounting for their true distribution during estimation. In sensor fusion, where asymmetric or multimodal distributions are common, this method provides a probabilistically accurate solution. It uses a factor graph-based sensor fusion approach and optimizes the GMM adaptation with the Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm [

128,

129].

In [

40,

130], a robust multisensor state estimation method combines a Particle Filter (PF) with a robust Extended Kalman Filter (R-EKF) using RBPF. It replaces the Gaussian likelihood with robust cost functions like Huber or Tukey biweight loss [

122] to better handle non-Gaussian errors and outliers unlike standard EKF methods [

131,

132]. The approach uses PF for linearization points and R-EKF for state estimation, integrating estimates across points with resampling [

133]. Position error bounds are estimated using a GMM and Monte Carlo integration [

55], addressing orientation uncertainty and providing robust probabilistic bounds. Limitations include sensitivity to initial parameters, potential convergence to local optima, and added complexity in tuning and balancing loss terms, which can introduce biases or errors.

8.2. Robust Modeling and Optimization: Summary and Insights

In conclusion, this section underscores the importance of both FDE techniques and robust modeling approaches for enhancing the integrity of localization systems. FDE qualifies system integrity by managing faults and deviations but doesn’t measure their impact on performance. Robust modeling qualifies and quantifies integrity by handling errors and providing probabilistic error bounds. Specifically, robust modeling offers two key features: it associates a probabilistic distribution over the error and dynamically accounts for variations in system uncertainty as described in [

125,

126]. Thus, to fully address the integrity of localization system, integrating FDE or robust modeling with PL is essential.

Lastly, while PL quantifies integrity, the evaluation of integrity varies across applications. This typically involves computing the Integrity Risk (IR) and comparing it with the Total Integrity Risk (TIR) to determine the likelihood of the true position exceeding the provided PL, as described in

Section 4.

Table 5 summarizes all the robust methods and compares them using various criteria.

9. Conclusion

In conclusion, this survey paper presents several significant contributions to the field of integrity methods in localization systems. It identifies a crucial gap in the research on integrity methods for non-GNSS-based systems, highlighting the need for more efforts in this area.

While of surveyed literature focuses on GNSS-based systems, only covers non-GNSS systems that use various sensors and approaches, such as cameras, LiDAR, fusion, optimization, or SLAM. Furthermore, among these, only a small fraction specifically explores protection level calculations.

This paper introduces a unified definition of integrity that encompasses both qualitative and quantitative aspects, cf.

Section 3. The new definition integrates robustness, outlier management, and deviation measures, providing a holistic evaluation of localization systems. The proposed framework improves upon existing definitions by offering a comprehensive view that includes the system’s alignment with reality and detailed error handling.

The survey reviews and refines the definitions of Protection Level (PL), cf.

Section 4. It points out that current definitions do not account for all uncertainties and limitations from system components and algorithms. The new definition of PL provided here addresses these gaps by requiring a real-time estimate of PL. This definition facilitates effective adjustment to changing environments and sensor conditions, ensuring real-time system integrity assessment.

The survey provides a detailed review of Fault Detection and Exclusion (FDE) methods. The FDE techniques are categorized into model-based and coherence-based approaches, examining their applications, effectiveness, and limitations. Model-based FDE methods are further divided into post-processing, pre-processing, and simultaneous-processing categories. While these methods are promising for fault handling, they face challenges related to scalability, reliability, computational complexity, model selection and accurate modeling. Coherence-based FDE techniques also encounter issues with scalability and effectiveness, particularly with irregular error patterns.

Moreover, the paper introduces robust modeling and optimization as essential methods for integrity. Unlike traditional FDE methods that focus primarily on qualification, robust modeling addresses both qualification and quantification. It provides probabilistic error bounds and adapts to variations in system performance, offering a more comprehensive view of integrity. This approach allows for a thorough assessment of system performance and measurement of how well it is functioning.

Finally, the survey includes comparative tables that summarize and evaluate various integrity methods, highlighting their strengths and limitations. This comparative analysis provides a clearer understanding of how different methods can be applied across various localization systems.

Overall, this paper offers a valuable reference for researchers and practitioners, presenting a detailed review of integrity methods, new definitions, and a comprehensive classification framework. It sets a foundation for future research and development, aiming to enhance the safety and efficiency of localization technologies by addressing key gaps and offering a more complete understanding of integrity and protection levels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Maharmeh, Alsayed, and Nashashibi; formal analysis, Maharmeh; visualization, Maharmeh, Alsayed, and Nashashibi; writing—original draft preparation, Maharmeh and Alsayed; writing—review and editing, Maharmeh; supervision, Nashashibi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allen, M.; Baydere, S.; Gaura, E.; Kucuk, G. Evaluation of localization algorithms. In Localization Algorithms and Strategies for Wireless Sensor Networks: Monitoring and Surveillance Techniques for Target Tracking; IGI Global, 2009; pp. 348–379.

- Shan, X.; Cabani, A.; Chafouk, H. A Survey of Vehicle Localization: Performance Analysis and Challenges. IEEE Access 2023. [CrossRef]

- SAE, J. 3016-2018, taxonomy and definitions for terms related to driving automation systems for on-road motor vehicles. Society of Automobile Engineers, sae. org 2018.

- Wansley, M.T. Regulating Driving Automation Safety. Emory Law Journal 2024, 73, 505.

- Patel, R.H.; Härri, J.; Bonnet, C. Impact of localization errors on automated vehicle control strategies. 2017 IEEE Vehicular Networking Conference (VNC). IEEE, 2017, pp. 61–68.

- Bosch, N.; Baumann, V. Trust in Autonomous Cars. I: Seminar Social Media and Digital Privacy, 2019.

- Zabalegui, P.; De Miguel, G.; Pérez, A.; Mendizabal, J.; Goya, J.; Adin, I. A review of the evolution of the integrity methods applied in GNSS. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 45813–45824.

- Zhu, N.; Marais, J.; Bétaille, D.; Berbineau, M. GNSS position integrity in urban environments: A review of literature. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2018, 19, 2762–2778. [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Gao, Y.; Shahbeigi, S.; Dianati, M. Integrity monitoring of GNSS/INS based positioning systems for autonomous vehicles: State-of-the-art and open challenges. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, 23, 14166–14187. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, F.A.C.; Torres, F.S.; García-Ortiz, A. Recent advances in sensor integrity monitoring methods—A review. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 10256–10279.

- Hassan, T.; El-Mowafy, A.; Wang, K. A review of system integration and current integrity monitoring methods for positioning in intelligent transport systems. IET Intelligent Transport Systems 2021, 15, 43–60. [CrossRef]

- Hewitson, S.; Wang, J. GNSS receiver autonomous integrity monitoring (RAIM) performance analysis. Gps Solutions 2006, 10, 155–170. [CrossRef]

- Angrisano, A.; Gaglione, S.; Gioia, C. RAIM algorithms for aided GNSS in urban scenario. 2012 Ubiquitous Positioning, Indoor Navigation, and Location Based Service (UPINLBS). IEEE, 2012, pp. 1–9.

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Gebre-Egziabher, D. Kalman filter–based RAIM for GNSS receivers. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2015, 51, 2444–2459.

- Hofmann, D. 48: Common Sources of Errors in Measurement Systems 2005.

- Hawkins, D.M. Identification of outliers; Vol. 11, Springer, 1980.

- SC, R. Minimum Operational Performance Standards for Global Positioning System/Wide Area Augmentation System Airborne Equipment. RTCA DO-229 1996.

- Brown, R.G. GPS RAIM: Calculation of thresholds and protection radius using chi-square methods; A geometric approach; Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics, 1994.

- Walter, T.; Enge, P. Weighted RAIM for precision approach. Proceedings of Ion GPS. Institute of Navigation, 1995, Vol. 8, pp. 1995–2004.

- Young, R.S.; McGraw, G.A.; Driscoll, B.T. Investigation and comparison of horizontal protection level and horizontal uncertainty level in FDE algorithms. Proceedings of the 9th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GPS 1996), 1996, pp. 1607–1614.

- Fredeluces, E.; Ozeki, T.; Kubo, N.; El-Mowafy, A. Modified RTK-GNSS for Challenging Environments. Sensors 2024, 24, 2712. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Kim, B.; Yang, D.W.; Kim, J.; Parkinson, T.; Billingham, J.; Park, C.; Yoon, J.; Lee, D.Y. A compact RTK-GNSS device for high-precision localization of outdoor mobile robots. Journal of Field Robotics 2024.

- EGA. Report on the performance and level of integrity for safety and liability critical multi-applications 2015.

- Mink, M. Performance of receiver autonomous integrity monitoring (RAIM) for maritime operations. PhD thesis, Dissertation, Karlsruhe, Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT), 2016, 2016.

- Bonnifait, P. Localization Integrity for Intelligent Vehicles: How and for what? 33rd IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV 2022), 2022.

- Hage, J.A.; Xu, P.; Bonnifait, P.; Hage, J.A.; Xu, P.; Bonnifait, P.; Integrity, H.; With, L.; Hage, J.A.; Xu, P.; Bonnifait, P. High Integrity Localization With Multi-Lane Camera Measurements To cite this version : HAL Id : hal-02180609 High Integrity Localization With Multi-Lane Camera Measurements 2021.