Introduction

Preterm birth is delivering a live baby before 37 completed weeks of pregnancy according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). It is further classified into four categories: extremely preterm (<28 weeks), very preterm (28 to <32 weeks), and moderate (32 to <34 weeks) and late preterm (34 to <37 weeks). It can occur spontaneously or initiated by labour induction or after a recommended elective caesarean section, usually for medical reasons [

1] .

In the literature, it is well documented that infection is a leading cause of preterm birth (PTB) among the other factors and is more so for deliveries that take place at the earliest phases of gestations [

2,

3,

4]. Currently, intrauterine infection/inflammation is the only provoking disease process resulting in spontaneous preterm labor/delivery for which a lucid causal correlation has been established [

5] .

Goldenberg et al, in 2008, published a review of the epidemiology and causes of PTB , the authors came up with four major pathways of, in what way microbial organisms can get to and invade the uterine cavity [

3] . They suggested a vertical ascension from the vagina, retrograde through the abdominal cavity via the fallopian tubes, introducing the microorganisms through invasive intervention such as amniocentesis and haematogenous pathway (via blood stream from the placenta). Although the vertical ascension route through the vagina is considered the most common pathway, the haematogenous route has been proposed playing a significant role as a route of bacterial infection of the pregnant uterine cavity via the maternal blood stream [

6] . Studies of this mode of infection in animal models by Han et al provided captivating evidence supporting the fact that hematogenous route is the pathway for oral bacteria to reach the uterine cavity. They further showed this phenomenon in human subjects [

6,

7,

8].

The traditional known view that the foetus develops in a sterile intrauterine environment was first brought into question when bacteria was cultured from amniotic fluid obtained from caesarean section deliveries by Harris and Brown in 1927 [

9].

In 2014, Combs et al. set out to explore the impact of microbial invasion of the amniotic fluid by culture method or detection of microbial 16S ribosomal DNA and/or inflammation by measuring the levels of IL-6 in amniotic fluid. They found that amniotic fluid samples from most cases of preterm labour, especially in the earlier phases of pregnancy (<28weeks), had evidence of presence of microorganisms in the amniotic cavity and/or inflammation. Increased IL-6 even in the absence of microorganisms in amniotic fluid had similar impact of pregnancy outcome, indicating that inflammation (chorioamnionitis) even in the absence of them had a deleterious effect on pregnancy [

10,

11].

Aagaard et al , in their study of placental microbiome applied cutting edge Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) methodology to explore the placental bacterial microbiota as well as delineated a unique microbiome that bore similarity to oral taxa from non-pregnant subjects, specifically to the bacterial microbiota of the tongue, tonsils, and gingival plaques as previously described by the Human Microbiome Project consortium [

4,

12,

13].

Onderdonk et al, in 2008, published a study related to detection of bacteria in placental tissues obtained from extremely low gestational age neonates. The authors reported positive cultures for 696/1365 placentas from pregnancies of 23–27 weeks gestational ages [

14].

Actinomyces sp. was one of the organisms noted in this study, which also included numerous other bacteria including

Streptococcus sp. In most published data, however,

Ureaplasma sp. are considerably the most commonly encountered microorganism in amniotic fluid (AF) from preterm pregnancies [

11].

Actinomyces infections are rare in pregnancy and are usually linked to preterm delivery in reported instances of intrauterine infection in pregnancy. These organisms are commensals which occur in many parts of the body without causing clinical problems. In 2016, Estrada et al set out to investigate if there are documented evidence in published data of Actinomyces infection in pregnancy being a threat to the obstetric patient and if that infection causes unfavourable pregnancy outcomes [

15]. These authors noted the rarity of Actinomyces infections in pregnancy in association primarily with preterm delivery. They reviewed all published literature on the subject in English language found on Pubmed up to April 2016 and identified 154 articles on the subject. From these published data, the rarity of Actinomyces as an aetiologic agent in chorioamnionitis leading to preterm birth was noted and reported in ten cases, while in seven cases there was no concurrent chorioamnionitis. Of this total number of cases reported, the primary origin of the infection was documented in 12 cases from sources such as cervical cerclage, periodontal infection, appendicitis, renal actinomycosis, and ovarian abscesses [

15] .

Actinomyces is a gram-positive rod, with low virulence and often a harmless commensal. Some are anaerobic while others are facultative anaerobes. The organism is often present in the oral cavity and is often seen in tonsils removed for histopathological examination. These organisms may also cause infection of the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and uterus, and in the female genital tract the microorganism may be part of the normal bacteria flora that inhabits the vagina and can result in infection independent of intrauterine device (IUD) use [

16].

The placenta is crucial to the wellbeing of the foetus in utero and provides both structural and functional connections between the mother and foetus. Its adequacy and functional capacity ensure the birth of a healthy baby. The placenta carries the structural evidences of the intrauterine life diary of the baby [

17,

18] and as such a careful macroscopic and microscopic pathologic examination is important and should be mandatory in all cases of the placentae from pregnancies resulting in preterm birth, babies with features of intrauterine growth retardation, still births and in situations of maternal or foetal complications related to pregnancy.

It is unusual to identify Actinomyces in the placenta by histopathologic examination and when present can be mistaken for bacteria clusters or overlooked. Therefore, a careful search for the offending organism is important in cases of chorioamnionitis, although this does not often yield a positive identification. Microbiologic correlation is best advised in cases of chorioamnionitis.

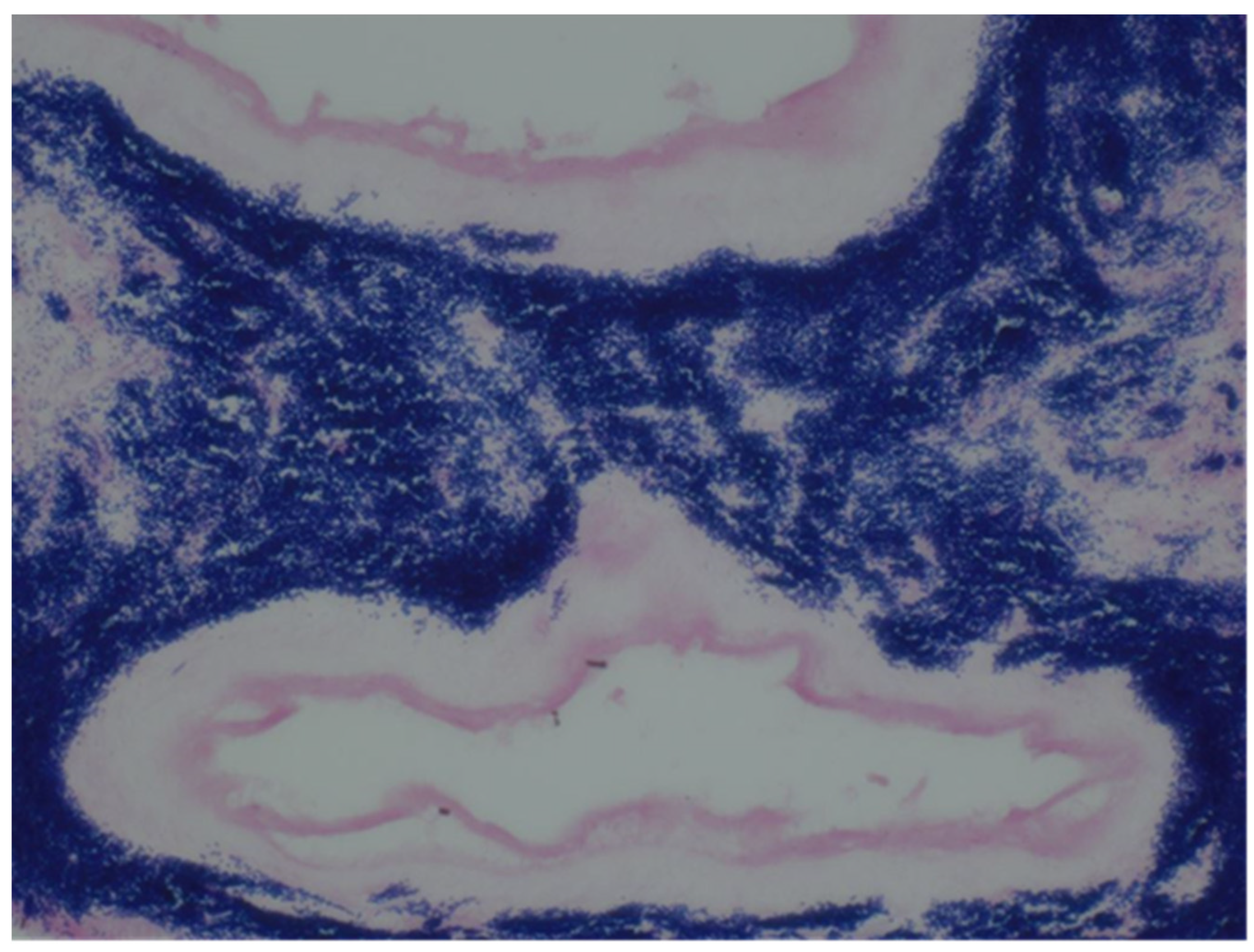

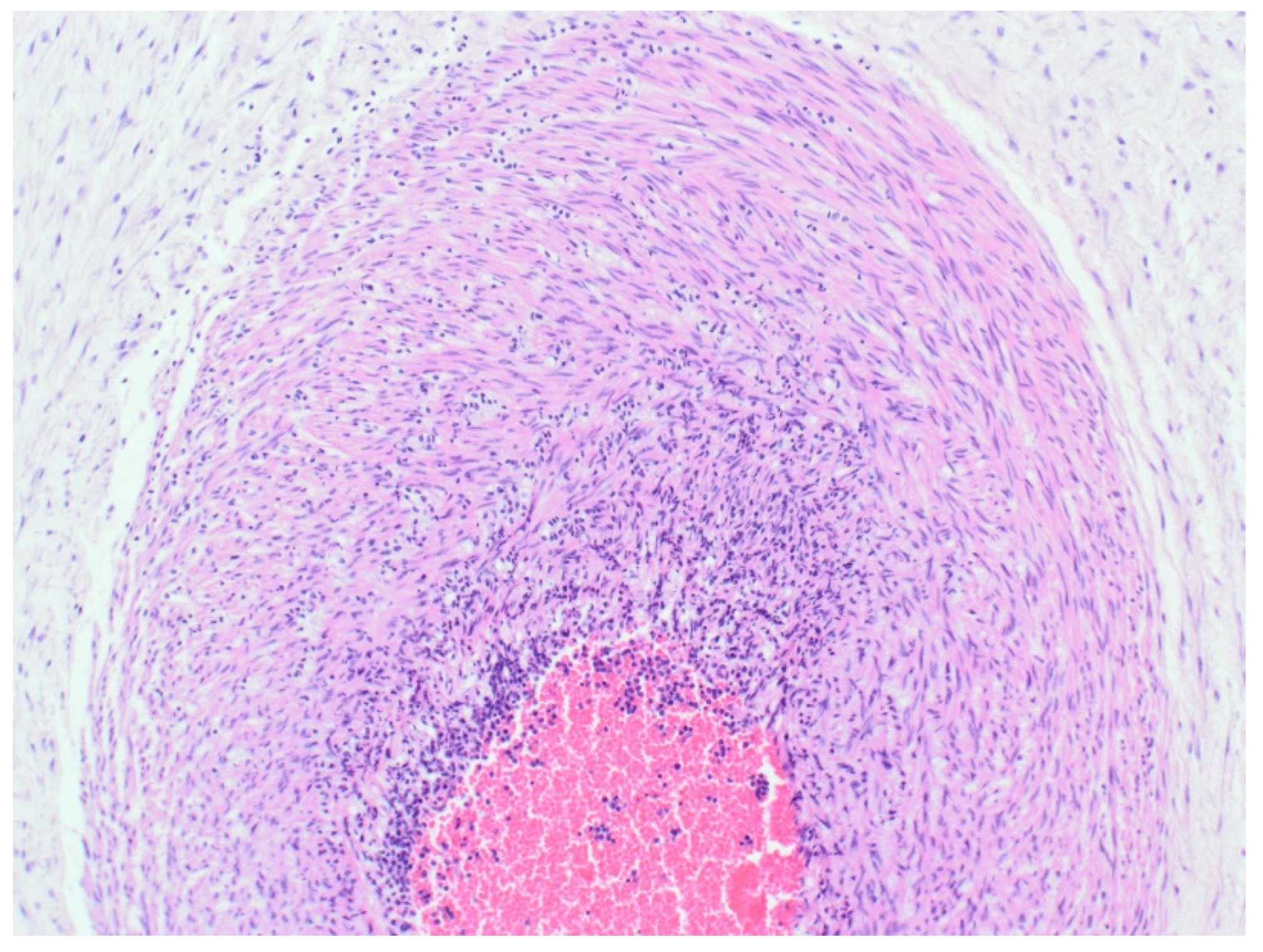

The histopathologic examination to identify Actinomyces as the causative organism include the use of routine Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and special stains including Grams, PAS, and Grocott’s Methenamine silver stain (GMS) of formalin fixed, paraffin embedded sections. The GMS will highlight the presence of branching bacteria filaments. It is rare to identify the well-described sulphur granules of actinomycosis as these are not always present.

Actinomycosis is sometimes recognised by the presence of characteristic sulfur granules, which are named for their yellow colour, which represent tangled filaments of

Actinomyces species [

19]. These granules represent Actinomyces filaments admixed with dead tissue debris and inflammatory exudates. Microscopic examination with routine Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining, these granules are a composite of round, oval, or horseshoe-shaped basophilic masses. Special staining with Gomori methenamine-silver stain (GMS) highlights the filamentous nature of the organism and histopathological examination has been found to be superior to bacteriological examination in biopsy samples [

20,

21].

The case presented in this report showed no clinical features of underlying infection in the mother, and spontaneous rupture of the membrane was quickly followed within hours of presentation in the hospital with established labour. It is therefore hypothesised that this case was of subclinical Actinomyces invasion of the amniotic cavity with subsequent development of chorioamnionitis and extreme preterm birth. It is therefore important to pay attention to the microbiological profile of pregnant women, including the presence of Actinomyces Spp in at-risk patients as part of the antenatal management plan and should include full dental examination.

Case Summary

A 33year lady, Para1 (0+0) who was registered for antenatal care presented at 20 weeks plus 4 days gestation with a history of bleeding, par, virginal abdominal pain, and premature spontaneous rupture of membrane. She was in established labour within three hours of membrane rupture and the liquor was clear. There was no unusual colour or odour to the liquor. There was no evidence of fever in the patient. She was delivered of a live male baby weighing 0.35kg (350gms), who died soon after birth. The placenta was sent for histopathological examination in line with the established protocol for such deliveries. She was discharged home on Co-amoxiclav. She had no history of miscarriages, and her antenatal care was uneventful.

Microscopy

The sample received in the histopathology department was a disc of placenta and membranes with an eccentrically inserted umbilical cord. The membrane appeared complete and were mostly translucent but with patchy areas of opacity. Microscopy revealed patchy severe acute Chorioamnionitis and a prominent cluster of Gram-positive filamentous bacteria which were also noted in routine H&E (

Figure 1) as well as with Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) staining (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 &

Figure 4). Aggregates of Splendore-Hoeppli reaction which are sulfur granules formed of masses of gram-positive bacteria with branching filaments are seen in the following micrographs (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 &

Figure 4).

Sections of the umbilical cord revealed acute inflammation (funisitis), but no organisms were seen in the umbilical cord (

Figure 7).

Discussion

Human actinomycosis is a well-established endogenous infection known to cause chronic, granulomatous infectious disease and has been well-known for a long time, being first described in 1896 by Kruse [

22]. Several Actinomyces species have been described, up to 25 in total and in the human body is present most commonly in the oral cavity as a commensal. Könönen and Wade, in 2015, published a paper with a study showing that, one third of the infants at age of 2 months, were already colonized with Actinomyces [

22]. As mentioned earlier, Actinomyces is also one of the components of the normal vaginal flora and can result in infection independent of intrauterine device (IUD) use, but chorioamnionitis due to Actinomyces has been reported previously, but is exceptionally rare [

16]. The organism is considered to have a low virulence potential and evidence shows that it seldom gives rise to infection in children younger than 10 years old [

23]

.

In our case, the infection was not suspected clinically and therefore microbiological testing was not requested. Microscopic examination of the placenta showed necrotizing acute chorioamnionitis in addition to the presence of microorganisms with a filamentous growth pattern. The findings were consistent with Actinomyces spp.

As prescribed in

Table 1, two previous case reports by Mann et al and Knee et al of neonatal sepsis due to actinomyces were preterm births at 27 weeks and 29 weeks gestations, respectively, and cultures of amniotic fluid revealed presence of the organism [

24,

25] . These authors argued that the true prevalence of Actinomyces infection might be underestimated or undervalued. This is due to the majority of the cases of premature deliveries and miscarriages that might be due to Actinomyces infection have had no microbiological analysis of amniotic fluid samples. Actinomyces invasion of the intrauterine cavity is a known complication of intrauterine devices (IUD) [

16,

26], and use of uterine cervical cerclage in the management of cervical weakness leading to preterm deliveries [

25]. Alsohime et al noted the association of Actinomyces in pregnancy with placement of cervical cerclage in a case of premature labour in the presence of a specific specie of Actinomyces; Actinomyces

neuii [

23] .

Subclinical infection is a recognised and important aetiologic trigger of preterm labour. In such instances, there is no clinically manifest evidence of maternal infection. Infection/inflammation in such cases is only discovered at the histopathological examination of the placental of such preterm births. Confirmation of this thinking is linked to the presence of the following: detection of histological chorioamnionitis rate is increased in preterm birth; clinical infection rate is increased after preterm birth; there is a significant association of some lower genital tract organisms and infections with preterm births or preterm premature rupture of the membranes; positive cultures of amniotic fluid or membranes in some patients with preterm labour and preterm birth [

3]. Moreover, laboratory markers of infection have been noted in preterm birth; as well as bacteria or their products which have been used to induce preterm birth in animal models [

2,

3,

34] .

Approximately 15 million babies are born preterm annually worldwide, indicating a global preterm birth rate of about 11%. With up to 1 million children dying from complications related to preterm birth before the age of 5 years, diseases related to preterm birth lead as the preeminent cause of death among children, accounting for 18% of mortality among children aged under 5 years and as much as 35% of all deaths among new-borns (aged <28 days) [

1,

3]. About two-thirds of preterm deliveries are due to spontaneous onset of preterm labour or preterm premature rupture of membranes. Preterm birth with the attendant high neonatal mortality and morbidity marks a traumatic psychological burden on families. It also constitutes a large burden on healthcare budgets. There is therefore a compelling need to gain a better understanding of its aetiologic factors. These factors are best studied by careful examination of the placenta as well as review of the maternal clinical and antenatal records to derive a complete picture of the preceding events. The pathologist therefore should be well informed in the macroscopic and microscopic examination of the placenta, and the interpretation/correlation of findings with clinical history to map management plans for patient [

18,

34] .

Chorioamnionitis

Preterm birth contributes considerably to the incidence of perinatal mortality and associated long-term morbidity. Chorioamnionitis is a recognisable pathological sequalae of infection leading to preterm birth. Acute chorioamnionitis has been consistently reported as the most frequent encountered pathology of the placenta in patients who had a spontaneous preterm delivery with intact or ruptured membranes [

35]. Chorioamnionitis is not always clinically apparent and features such as maternal fever, tachycardia, uterine tenderness, and preterm rupture of membranes, are rarely present. However, subclinical/histologic chorioamnionitis is more commonly identified through placental microscopic examination when inflammation of the chorion, amnion, and decidua is seen [

35]. This scenario is commoner in delivery prior to 30 weeks of gestation and usually associated with clearly identifiable histological chorioamnionitis, together with inflammatory cells in the umbilical cord (in cross-section), and placental disc. A foetal inflammatory response is often seen in cases of Chorioamnionitis. The foetal inflammatory response syndrome (FIRS) is defined by increased systemic inflammatory cytokine concentrations, funisitis, and foetal vasculitis [

35,

36].

Close by the end of 2019, the sudden outburst of coronavirus disease triggered a worldwide pandemic [

37]. Researchers investigated the impact of coronavirus on pregnancy, the evidences suggest that intrauterine vertical transmission to fetuses was rare however it did happen. In a review by Wong et al in 2021, it was mentioned that the published data related to chorioamnionitis in COVID-19 positive patients revealed placental non-specific histopathological features, which include inflammation, maternal vascular malformation, and fetal vascular malperfusion [

38].

The incidence of uterine cavity inflammation is contrarily related to gestational age, such that it is implicated in most extremely preterm births and 16% of preterm births at 34 weeks [

39]. It is noted as one of the most common causes of premature birth and will thus appear that since Louis Pasteur first linked microorganisms with human disease when he identified the streptococcal aetiology of puerperal sepsis, microbes continue to play significant roles in outcome of pregnancies

[3,39,40].

In view of the major health care challenge posed by premature birth as the leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide, it is important for pathologists to be aware of the importance of this finding in placenta examination. It is also the leading cause of chronic debilitating healthcare challenges in the young such as cerebral palsy and neurologic handicap

[41,42].

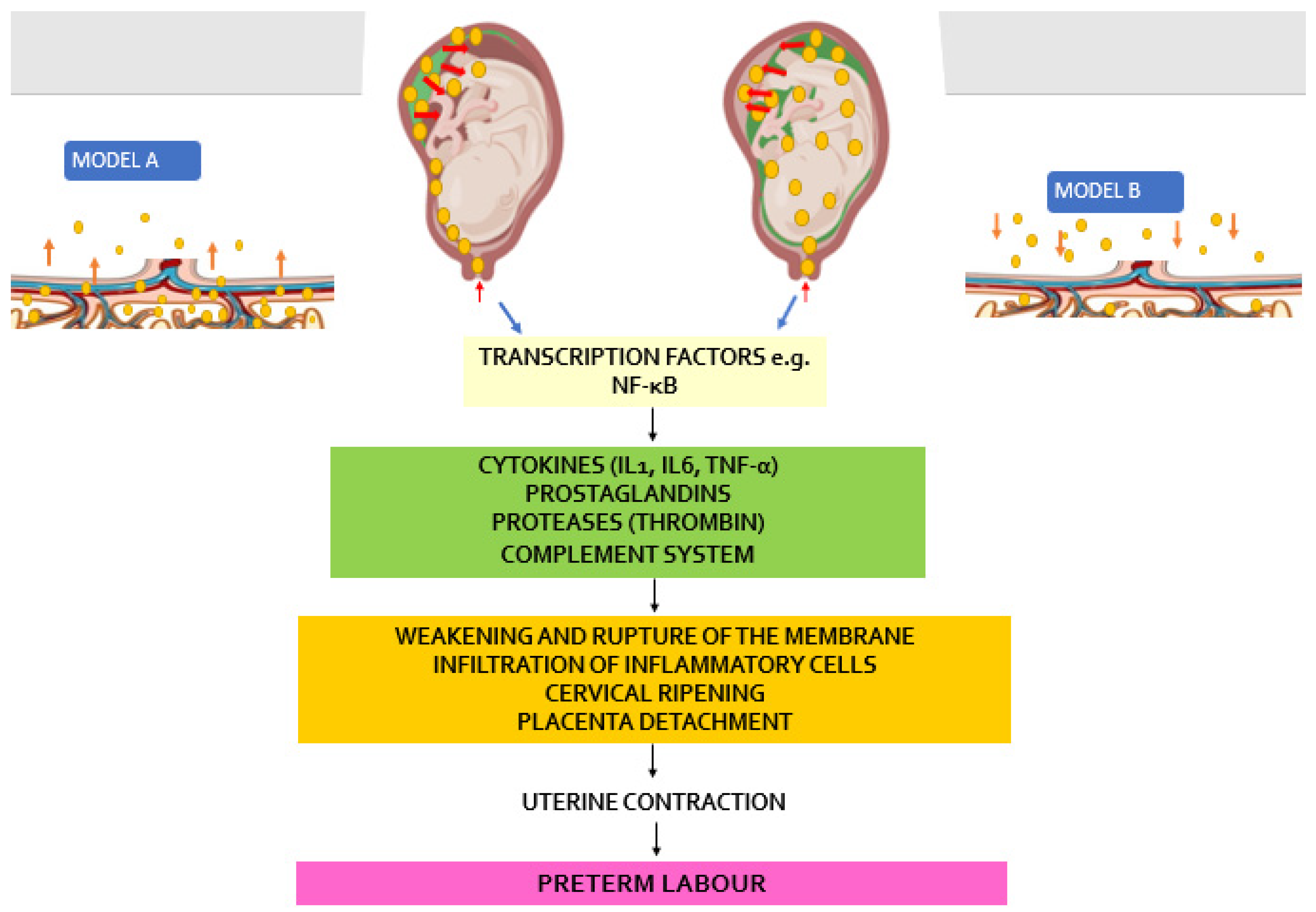

Pathogenesis of Chorioamnionitis and Inflammatory Cascade Leading to Preterm Birth

Two pathways have been proposed as possible routes of microbial invasion of the uterine cavity in pregnancy. The most stated involves microorganisms first invading choriodecidual tissue, provoking an inflammatory reaction leading to uterine and cervical responses leading to preterm birth [

3]. The second, a more recently argued hypothesis proposes microbial invasion of the amniotic fluid compartment, proliferating within this space with an associated inflammatory reaction before invading the choriodecidual tissue [

5] . In both scenarios it is thought that there is release of microbial endotoxins and exotoxins. These are recognised by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) housed on the surfaces of leukocytes, dendritic, epithelial, and trophoblast cells, These TLRs are thought to activate the release of a number of transcription factors which further engineer the production and release of cytokines and chemokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1

α, IL-1

β, IL-8, and tumour necrosis factor-

α (TNF

α) downstream within the decidua and the foetal membranes. The molecular end point of these series of molecular activity is the stimulation of prostaglandins and uteroactive chemokine production (

Figure 8). The inflammatory cascade can also lead to neutrophil chemotaxis, infiltration, and activation, resulting in the synthesis and release of metalloproteases [

35,

40,

43,

44].

Prostaglandins are known to be uteroactive with the capacity to stimulate uterine contractions and this activity occurs simultaneously as the metalloproteases induce a ripening effect on the cervix and degradation of the amniotic membrane exerts enough pressure to cause membrane rupture with onset of preterm labour [

38]

.

Two hypothesised models of upward bacteria migration to invade the intraamniotic cavity leading to the development of chorioamnionitis.

Model A: Bacterial trafficking is primarily along the chorioamniotic or choriodecidual planes before invading the Chorioamniotic cavity. This is the more commonly held view of bacterial invasion of the amniotic cavity.

Model B: Kim et al however argued that contrary to the idea proposed in the model A, bacteria gain access and invade the amniotic cavity via very restricted regions in the intact or ruptured membranes, then proliferate in the amniotic fluid, before the bacteria invade the chorioamniotic and/or choriodecidual planes [

5].

In both models, however, the final common pathway is the release of cytokines, chemokines, prostaglandins, and proteases which modulate uterine contraction and cervical ripening leading to preterm labour/birth.

Route of Bacteria Spread into the Amniotic Cavity in Pregnancy

The amniotic cavity was considered a sterile environment in the past as first reported by Harris and Brown in 1927, and any finding of microbes in amniotic fluid obtained through amniocentesis was considered a pathological finding [

9]. The use of molecular testing tools including PCR, FISH assay for levels of IL-6 reveals the presence of organisms that were otherwise non culturable as well as evidence of intra-amniotic fluid inflammation even in the absence of a positive traditional culture positive samples. This is consistent with the idea of subclinical intraamniotic fluid infection/inflammation in PTB. In these instances, the use of standard microbiology culture methods represents gross under reporting of actual state of bacteria/microbial invasion of amniotic cavity [

5,

8,

11] .

Mendez et al in 2013 noted the significance of infection-related causes of preterm birth, undertook a systematic review of data published between 1995 and 2013 about intrauterine microbiome; molecular information available and summaries of species found in healthy individuals and in women with diagnosed infections. The authors wanted to provide a detailed database of the documented intrauterine microbiome. This would be a powerful tool as a baseline tool to understand microbial populations in the intra-amniotic space, their contribution to preterm birth, clinical scenarios, and foetal outcome, particularly regarding infant mortality and morbidity. The outcome with this extensive review of published works on the subject in the English literature was the conclusion that the commonest offending organisms were those usually present in the vagina, oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract and the airways. They therefore concluded that ascending route from the vagina was probably the commonest mode of microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity [

11].

In terms of the distribution of bacteria noted in 761 women represented in the various studies reviewed, one case of Actinomyces was reported, emphasising the rarity of this organism as a cause of intrauterine infection in pregnancy and with resultant PTB [

11].

Potential role of Screening

There have been proponents for routine screening of amniotic fluid for actinomyces particularly in clinically predisposed women; namely, those with history of IUD use, history of miscarriages or vaginal discharges [

9,

23,

35]. A high index of suspicion may be key as in our case, in which there was no clinical evidence of chorioamnionitis.

Kim et al suggested that developing and/or deploying clinical strategies to prevent ascending microbial invasion could provide a possible solution. Similarly, the availability of rapid diagnostic tools such the use of molecular techniques and effective treatment of bacteria/microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity holds the key to preventing preterm birth with its unwholesome sequelae [

5].

Future Research Focus

Clinical programmes to minimise the feasibility of microbes gaining access to and proliferating in the amniotic cavity should be a focus of future research. Moreover, where this is unavoidable or could have occurred, an intrauterine infection screening programmes for the early detection of subclinical microbial invasion of the amniotic fluid/cavity should also be an area of active research.

It is to be emphasised that recent evidence points to microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity preceding widespread infection of the chorioamniotic membrane, rather than infection starting from choriodecidual tissue before spreading into and proliferating in the amniotic fluid. Rather, the reverse appears to be the case [

45] .

There is a need for a well-articulated universal approach to the appropriate management of foetuses in bacteria-infected amniotic fluid environment. This uniform approach will minimise the present glooming statistic of bacterial infection of the amniotic cavity (BIAC) as the chief cause of neonatal mortality worldwide [

46].

Conclusion

This case is important because of the rarity of actinomycosis as a cause of subclinical intrauterine bacterial infection in pregnancy. Clinicians and pathologists alike should be aware of this possibility even in the absence of intrauterine device use or cervical cerclage.

As low and very low birth weight neonates suffer a higher rate of mortality and serious neonatal morbidity, and with the consistent evidence of intrauterine infection in pregnancy as a major contributor to this dire condition, there is a need for bench-to-bedside focused research in obstetrics about preventive approaches to bacterial invasion of the amniotic cavity (BIAC). This approach will speed up the aggregation of the current state of knowledge on this subject and therefore the development of applications and techniques to detect subclinical BIAC and the selection of safe therapies to reduce the impact of both subclinical and clinical bacterial invasion of the amniotic cavity (BIAC) on the baby.

References

- WHO. Preterm Birth. Facts sheeths 2018 [cited 2023 08 October]; Updates related to preterm labour].

- Payne, M.S.; Bayatibojakhi, S. Exploring preterm birth as a polymicrobial disease: an overview of the uterine microbiome. Frontiers in immunology 2014, 5, 595–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, R.L.; et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet (London, England) 2008, 371, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagaard, K.; et al. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Science translational medicine 2014, 6, 237ra65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J.; et al. Widespread microbial invasion of the chorioamniotic membranes is a consequence and not a cause of intra-amniotic infection. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology 2009, 89, 924–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.W.; et al. Transmission of an uncultivated Bergeyella strain from the oral cavity to amniotic fluid in a case of preterm birth. Journal of clinical microbiology 2006, 44, 1475–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.W.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces premature and term stillbirths in pregnant mice: implication of oral bacteria in preterm birth. Infection and immunity 2004, 72, 2272–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.W.; et al. Term stillbirth caused by oral Fusobacterium nucleatum. Obstetrics and gynecology 2010, 115, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.W.; Brown, J.H. Bacterial content of the uterus at cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1927, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, C.A.; et al. Amniotic fluid infection, inflammation, and colonization in preterm labor with intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014, 210, 125.e1–125.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendz, G.L.; Kaakoush, N.O.; Quinlivan, J.A. Bacterial aetiological agents of intra-amniotic infections and preterm birth in pregnant women. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2013, 3, 58–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Methé, B.A.; et al. A framework for human microbiome research. Nature 2012, 486, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Huttenhower, C.; et al. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Onderdonk, A.B.; et al. Detection of bacteria in placental tissues obtained from extremely low gestational age neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008, 198, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, S.M.; Magann, E.F.; Napolitano, P.G. Actinomyces in Pregnancy: A Review of the Literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2017, 72, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzhugh, V.A.; Pompeo, L.; Heller, D.S. Placental invasion by actinomyces resulting in preterm delivery: a case report. J Reprod Med 2008, 53, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Evans, C.; Cox, P. Tissue pathway for histopathological examination of the placenta. 2019, RCPath: UK.

- Jaiman, S. Gross Examination of the Placenta and Its Importance in Evaluating an Unexplained Intrauterine Fetal Demise. Journal of Fetal Medicine 2015, 2, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.H.; et al. Imaging of actinomycosis in various organs: a comprehensive review. Radiographics 2014, 34, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smego, R.A., Jr.; Foglia, G. Actinomycosis. Clin Infect Dis 1998, 26, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrara, J.; Hervy, B.; Dabi, Y.; Illac, C.; Haddad, B.; Skalli, D.; Miailhe, G.; Vidal, F.; Touboul, C.; Vaysse, C. Added-Value of Endometrial Biopsy in the Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategy for Pelvic Actinomycosis. Journal of clinical medicine 2020, 9, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Könönen, E.; Wade, W.G. Actinomyces and related organisms in human infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015, 28, 419–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsohime, F.; Assiri, R.A.; Al-Shahrani, F.; Bakeet, H.; Elhazmi, M.; Somily, A.M. Premature labor and neonatal sepsis caused by Actinomyces neuii. J Infect Public Health 2019, 12, 282–284. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2018.04.001. Epub 2018 Apr 26. PMID: 29706318.Fitzhugh VA, Pompeo L, Heller DS. Placental invasion by actinomyces resulting in preterm delivery: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2008 Apr;53(4):302-4. PMID: 18472656.

- Mann, C.; Dertinger, S.; Hartmann, G.; et al. Actinomyces neuii and Neonatal Sepsis. Infection 2002, 30, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knee, D.; Christ, M.; Gries, D.; et al. Actinomyces Species and Cerclage Placement in Neonatal Sepsis: A Case Report. J Perinatol 2004, 24, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westhoff, C. IUDs and colonization or infection with Actinomyces. Contraception 2007, 75, S48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakut, H.; Achiron, R.; Treschan, O.; Kutin, E. Actinomyces invasion of placenta as a possible cause of preterm delivery. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 1987, 14, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.R., Jr.; Stinson, D.; Wade, A.; Haldane, D.; Heifetz, S.A. Necrotizing funisitis associated with Actinomyces meyeri infection: a case report. Pediatr Pathol. 1994, 14, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.A.; Abadi, J. Actinomyces chorioamnionitis and preterm labor in a twin pregnancy: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996, 175, 1391–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghamdi, A.; Tabb, D.; Hagan, L. Preterm Labor Caused by Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes, Low Platelet Count (HELLP) Syndrome and Postpartum Infection Complicated with Actinomyces Species: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2018, 19, 1350–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giron de Velasco-Sada, P.; Peinado, H.; Romero-Gómez, M.P. Neonatal sepsis secondary to chorioamnionitis by Actinomyces neuii in a 25 weeks pregnant woman. Med Clin (Barc) 2018, 150, 407–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, H.C.; Ling, A.C.; Ng, D.S.; Ng, R.X.; Wong, P.L.; Omar, S.F.S. Case report : Actinomyces naeslundii complicating preterm labour in a trisomy-21 pregnancy. IDCases 2021, 23, e01051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, M.S.; Hefter, Y.; Stone, B.; Hahn, A.; Jantausch, B. A Premature Infant With Neonatal Actinomyces odontolyticus Sepsis. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021, 10, 533–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faye-Petersen, O.M. The placenta in preterm birth. J Clin Pathol 2008, 61, 1261–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinsky, R.; et al. The consequences of chorioamnionitis: preterm birth and effects on development. J Pregnancy 2013, 2013, 412831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotsch, F.; et al. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2007, 50, 652–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, A.S.; Asaad, A.; Fisher, R.; Clayton, G.; Syed, A.; Barron, M.; Idaewor, P.; Salih, A.; Elamass, M.; Aladili, Z.; Menon, J.; Uddin, A.; Gee, H.; Bonner, D.; Merron, H.; Duncombe, K.; Campaner, G.; Alkistawi, F.; Targett, J.; Eleti, S.R.; Comez, T.; Smith, S.; Thomas, H.; Lovett, B.; Chicken, W. The Challenge of COVID-19: The Biological Characteristics and Outcomes in a Series of 130 Breast Cancer Patients Operated on During the Pandemic. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2020, 115, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Y.P.; Khong, T.Y.; Tan, G.C. The Effects of COVID-19 on Placenta and Pregnancy: What Do We Know So Far? Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahra, M.M.; Jeffery, H.E. A fetal response to chorioamnionitis is associated with early survival after preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004, 190, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Evans, T.W.; Finney, S.J. Bench-to-bedside review: sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock - does the nature of the infecting organism matter? Crit Care 2008, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, B.H.; Park, C.W.; Chaiworapongsa, T. Intrauterine infection and the development of cerebral palsy. Bjo 2003, 110 (Suppl 20), 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, W.W.; et al. Early preterm birth: association between in utero exposure to acute inflammation and severe neurodevelopmental disability at 6 years of age. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008, 198, e1–e466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V.; Hirsch, E. Intrauterine infection and preterm labor. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2012, 17, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aishah, A.; Saeed, M.; Mohammed, A. Intrauterine infection as a possible trigger for labor: the role of toll-like receptors and proinflammatory cytokines. Asian Biomedicine 2015, 9, 727–739. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert, D.H.; et al. Recurrent High-Flow Arterio-Venous Malformation of the Thyroid Gland. Thyroid 2015, 25, 1060–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, L.F.; Chaiworapongsa, T.; Romero, R. Intrauterine infection and prematurity. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002, 8, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).