2. An Alternative Definition of an Assembly Space

An assembly space

is defined in [

1] (cf. Definition 8) as an acyclic directed graph

, where

is the set of vertices and

is the set of edges together with an edge labeling map

.

contains a finite and non-empty set of vertices

that form the basis of

, each reachable only from itself. All remaining vertices of

are reachable from a vertex in

. The edge labeling map

cleverly defines the assembly step. Namely

allowing to write

,

, and

However, the commutativity of the relation (

2) cannot imply the commutativity of the string concatenation. If all assembly

objects in

are strings

does not imply

, as might be expected for string concatenation, but it actually implies also

. Therefore, a string assembly space is endowed in [

1] with the additional property (cf. [

1], Definition 18 and Eq. (10))

and likewise for the edge

.

However, this conclusion and, thus, the inevitability of the property (

3) it entails makes the string associated with the terminating vertex

z unresolvable if

. Here, we provide an alternative definition of the assembly space, noting that vertices

x,

y, or

z of the assembly space are not the same as strings

,

, or

they are associated with.

Definition 1 (Assembly Space).

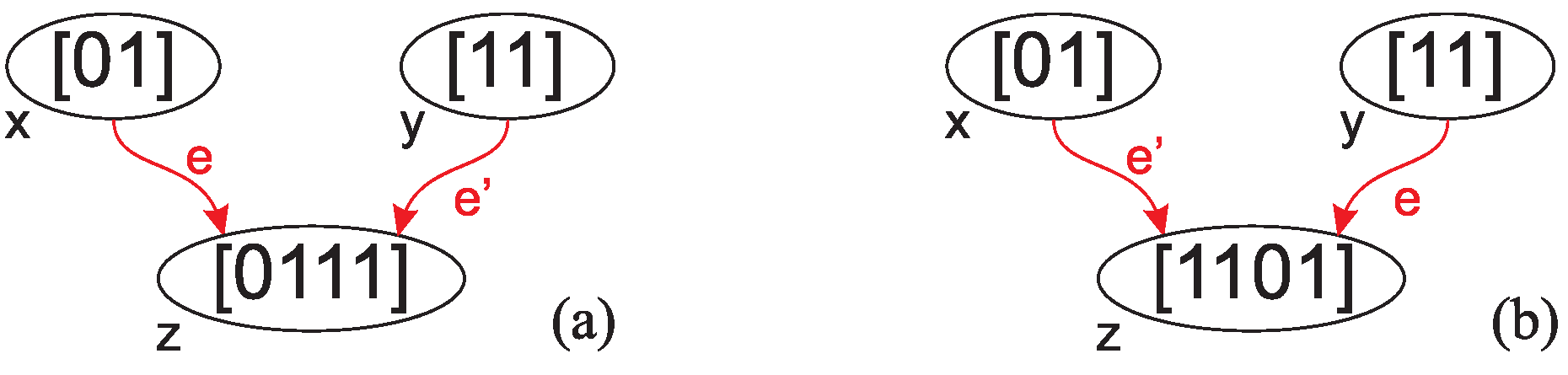

An assembly space is an acyclic, 2-in-regular digraph , where V is a set of vertices associated with strings with b inaccessible vertices associated with different basic symbols c of unit length, and the edge labeling map defined as:

that defines the concatenation order of the strings , associated respectively with vertices x, y in the string associated with the vertex z being the endpoint of both edges e and .

The set of

b inaccessible vertices forms the initial assembly pool

[

3] and is equivalent to the basis

(cf. [

1], Eq. (7)). We note that the definition of edge labeling map (

4) is possible if only

, i.e., the initial assembly pool contains more than one distinct basic symbol, as in that case we can say that a given symbol is the 1

st one in the initial assembly pool, another is the 2

nd one, and so on; we can sort them. Otherwise, the notion of a

concatenation direction is pointless for one symbol only. The relation (

4) preserves the commutativity of the assembly step in terms of the vertices labels, that is

, but defines the order of concatenation of the strings associated with those labels, as for different strings

. This is shown in

Figure 1.

In an acyclic, 2-in-regular digraph, each accessible vertex has exactly two incoming edges corresponding to the assembly step. This definition extends the previous definition of the assembly space as a quiver [

4]; the notion of self-reachability of vertices of an assembly space is misleading as it suggests some

self-assembly. Hence, basis

objects are inaccessible, not

self-reachable (cf. [

1], Definition 7).

3. The Assembly Steps Problem is NP-Complete

In order to show that any instance of Vertex Cover Problem

, where

is a graph,

is the set of vertices and

is the set of edges and

k is the cardinality of a set of vertices that includes at least one vertex of every edge of

G, which is known to be NP-Hard, can be reformulated in polynomial time as an instance of the Assembly Index Problem, the following procedure is offered (cf. [

1], Section 4.2). For a given instance of the Vertex Cover Problem

, where

, and

is the vertex cover number (the size of a minimum vertex cover), an instance of the Assembly Index Problem

is constructed, where

is a constructed assembly space, and

is the target string for which the assembly index

is to be determined. It is then claimed that a certificate for the Vertex Cover Problem

containing a subset

of vertices of

G that includes at least one vertex of every edge of

G can be used to produce a certificate

for the Assembly Index Problem and vice versa, where

is a rooted subspace (cf. [

1] Definition 15) of the assembly space

containing only a proper subset

of the strings of the form

. Hence, such an instance of the Assembly Index Problem would be logically equivalent to an instance of the Vertex Cover Problem from which it was constructed.

The construction of

(cf. [

1], Section 4.2) begins with forming the basis of the assembly space

(cf. Eqs. (17), (50))

containing

symbols of vertices

, and a special symbol that here we call 0 (it is defined as # in [

1]). Hence,

. Then, a set of

strings

is assembled (Eq. (18)) Subsequently, a set of

strings

is assembled (Eq. (19)). The last step of the construction of

is a sequence of

strings

and

strings

defined in [

1] by Eqs. (20)-(25), where the target string

is defined as the last string of this sequence and

Finally ([

1], Section 4.2.3) it is claimed that given

is a certificate for the Assembly Index Problem if the set (

5) is a vertex cover of

G with size

k, i.e. a certificate for the Vertex Cover Problem is given, wherein

is the assembly index of string

and

which depends on

k and is minimal if

.

By construction, the basic symbols (

6), the edge strings (

8), and the sequence strings (

9a) and (

9b) contained in

must also be contained in

(certificate). However, the vertex strings (

7) of the form

are the exception, as each of the edge strings (

8) can be assembled from strings (

7) in one of the two mutually exclusive steps (cf. [

1] Eqs. (53), (54))

leaving some of the strings

or

redundant. It can be seen by comparing the cardinalities of the spaces

(

10) and

(

11), which - as expected - leads to

.

By construction (

9a), (

9b), the target string has the form

where the

is a vertex-specific part of

depending solely on

and its explicit form is given by the formula (

9a), and the

is an edge-specific part of

, generated by the formula (

9b), and depending both on

, edge vertex assignments and the order of labeling of the edges of graph

G. However,

, as the length of each edge string (

8) is five and there are

such strings in

and

. Therefore, the length of the target string is

Furthermore, by construction

contains two copies of the string

of length

having the assembly index equal to

as it does not contain any repetitions of substrings. We can take advantage of the fact that each

m copies of an

n-plet

contained in a string decrease the assembly index of this string at least by

[

3], where

is the assembly index of this

n-plet, to estimate the upper bound for the assembly index of

reduced by the presence of these two copies of

. Furthermore, excluding the degenerate cases of empty and disjoint graphs

G, we can further infer some information about

. That is, since any vertex

is a part of some edge

,

contains at least two repetitions of doublets

(or

), with

as the string

also contains

such doublets, and each repetition decreases the assembly index by one. Hence, the upper bound must be further decreased by

. Finally, each string

contains

repetitions of a doublet

and, hence, the upper bound must be further decreased by

. Therefore, the initial upper bound on the assembly index that amounts to

[

5] if

[

3] decreases to

which, in contrast to

(

11), is independent of

k.

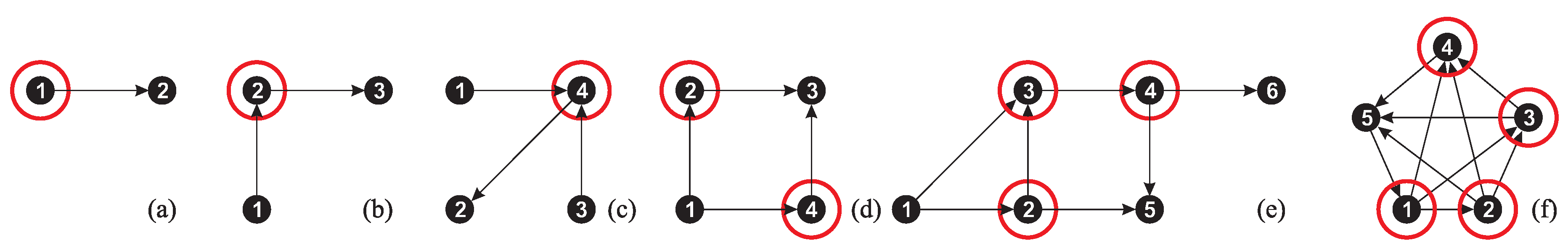

We have examined a few simple graphs, shown in

Figure 2, obtaining the results listed in

Table 1.

As an example, consider the trivial graph

, shown in

Figure 2(b) having two edges connected at one vertex. Hence, its vertex cover number is

. In this case,

and the target string generated by sequences (

9a) and (

9b) has the form

As the vertex cover of the graph

G is the vertex 2, the subspace

(the certificate) is devoid of triplets

and

, since the edges

and

share the vertex 2, and the edge strings (

8) could be assembled as

and

. Therefore, the number of steps on the assembly pathway of

defined by

, given by the relation (

11), amounts to

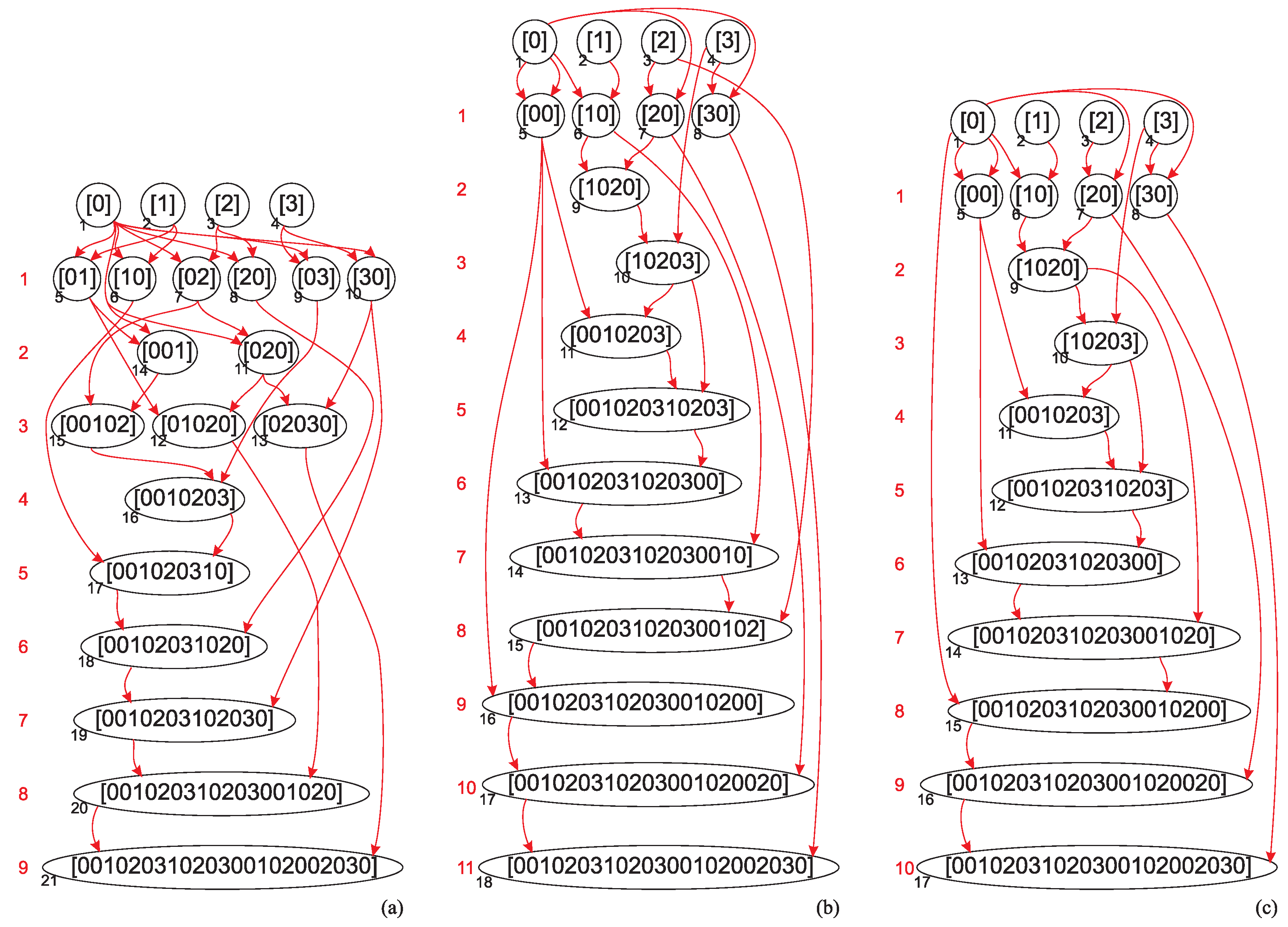

, as shown in

Figure 3(a) also illustrating the assembly depth [

6] (

) of this string: 7 steps (5-11) for vertex strings (

7), 2 steps (12,13) for edge strings (

8), 6 steps (14-19) for sequence strings (

9a), and 2 steps (20,21) for sequence strings (

9b)) which corresponds to the vertex cover number

, if only the string (

16) is assembled using the set of allowed assembly operations defined by the equations Eqs. (38)-(45) of [

1].

However, imposing such a set of allowed assembly steps deviates from the principles of assembly theory that assume the possibility of assembling any

object from any two

objects in the assembly pool. Even if we assume that only some steps are allowed and some are not due to peculiarities of the assembled data structures, this is certainly not the case for strings, considered in [

1] in the proof of Lemma 3. All strings are possible and mathematically well defined [

7]. The evolution of information became possible as soon as a first bit, not a first

particle or

object, became accessible [

2,

3,

8,

9].

Therefore, the assembly index of the string (

16) is

. One of the shortest pathways of the string (

16) is shown in

Figure 3(c) with

. A quadruplet

present in two independent copies is assembled in step 5, 5-plet

present in two copies is assembled in step 6. Furthermore,

contains two independent copies of

,

, and

. A slightly longer pathway leading to the string of length (

15) is shown in

Figure 3(b).