1. Introduction

The concept of a blockchain was first introduced in a 2008 white paper by the pseudonymous person or group known as "Satoshi Nakamoto" [

1]. In that paper, Nakamoto described a decentralized electronic cash system called Bitcoin, which used a blockchain to record and verify transactions. The first blockchain-based cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, was launched in 2009. It used a decentralized network of computers to maintain a shared ledger of transactions, with the blockchain serving as a secure and transparent record of all transactions on the network. Since the launch of Bitcoin, blockchain technology has evolved and been adapted for various applications beyond cryptocurrency.

Blockchain can potentially revolutionize a wide range of industries, including finance, healthcare, and supply chain management. By enhancing security, efficiency, and transparency, blockchain can fundamentally improve various transactions and processes across these sectors [

2,

3,

4]. Since its introduction, blockchain technology has experienced rapid innovation and widespread adoption, continually evolving to meet the needs of the digital age. This evolution has led to the development of diverse blockchain networks, including public, private, and consortium blockchains, each tailored to different use cases and requirements [

5,

6]. Overall, blockchain is poised to transform numerous industries and redefine the way we conduct business in the digital era.

Blockchain and distributed ledger technology (DLT) are often used interchangeably, but they are not the same thing. Blockchain is a type of DLT that uses a decentralized network of computers to maintain a shared ledger of transactions. It is characterized by its use of cryptographic techniques to ensure the integrity and security of the data on the ledger. On the other hand, DLT refers to any technology that enables the maintenance of a shared ledger of transactions across a decentralized network of computers. DLT can include blockchain, but it can also include other types of technologies, such as directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) and distributed hash tables (DHTs) [

7]. So, blockchain is a specific type of DLT, but DLT is a broader term that includes a range of technologies that enable the maintenance of a shared ledger of transactions across a decentralized network. One of the advantages of DLT is that it is more flexible and can be customized to meet the needs of a wide range of applications such as transactions and exchange of medical data or information [

8].

Corda is an open-source DLT platform designed specifically for financial services. It was developed by the Corda Consortium, a group of leading financial institutions and technology companies, to create a more efficient and secure way of managing financial transactions and automating complex business processes [

9]. Corda is built on the principles of privacy, security, and interoperability. It uses a DLT architecture to enable the secure and transparent exchange of data and assets between participants or nodes on the network. Corda uses smart contracts to automate complex business processes and to ensure that transactions are executed consistently and predictably. Further, Corda is designed to be highly scalable and can handle a high volume of transactions without sacrificing performance or reliability [

10]. Although the theoretical foundation of Corda DLT has advanced significantly, research on its feasibility within the healthcare ecosystem remains limited [

11]. This article addresses this gap by conducting a comprehensive study, evaluation, and analysis of Corda’s technological feasibility for implementation in the healthcare sector.

Besides, this work addresses aspects related to the architectural structure of an application based on Corda DLT, as well as a programming paradigm. As a result, a Corda distributed application (CorDapp

1) is developed for the health area where aspects such as integrity, authenticity, confidentiality, traceability, and auditability through obtaining performance metrics are evaluated and analyzed. This CorDapp is designed to facilitate the secure exchange of sensitive medical information among key stakeholders, including doctors, patients, caregivers, and family members. By improving communication, it aims to reduce misunderstandings and ensure that all parties are accurately informed. The application creates formal records of procedures, events, and occurrences, thereby enhancing treatment adherence and continuity of care. It also centralizes the storage of medical data, generating comprehensive reports in one location, which can lead to more accurate diagnoses and better overall patient care. This is particularly beneficial when multiple specialties are involved, allowing doctors to spend more time directly interacting with patients. By integrating all components of the healthcare ecosystem, the Corda application streamlines the management of the medical care cycle, reducing the time required for care, diagnosis, and treatment.

1.1. Contributions

This work contributes to the integration of Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) within the healthcare ecosystem in the following ways:

Development of a Healthcare-Specific CorDapp: ACorda Distributed Application (CorDapp) was designed and developed specifically for managing healthcare information. This CorDapp addresses the specific needs and challenges of the healthcare sector.

Comprehensive Evaluation of CorDapp Attributes: The effectiveness of the CorDapp in ensuring data integrity, authenticity, confidentiality, traceability, and auditability has been analyzed.

Performance Evaluation: A detailed performance evaluation of the CorDapp was conducted, evaluating metrics such throughput, latency, CPU usage, and memory consumption in both local and cloud network environments.

Enhanced Communication and Data Handling: The CorDapp facilitates secure exchanges of sensitive medical information among stakeholders, which improves communication and mitigates misunderstandings within the healthcare ecosystem.

Improved Patient Care: By centralizing and consolidating medical data storage and generating comprehensive reports, the CorDapp contributes to better treatment adherence, continuity of care, and diagnostic precision.

Architectural and Programming Insights: Insightsinto the architectural design and programming paradigm of the CorDapp, offering valuable information for similar applications in different sectors.

The remainder of this work is organized as follows: in

Section 2, a state-of-the-art review of blockchain applications in healthcare is presented. Next,

Section 3 covers the fundamental concepts of Corda.

Section 4 details the structure and development of the CorDapp within the healthcare ecosystem.

Section 5 describes the testing methodology, while

Section 6 analyzes the performance test results of the Corda network. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

This section provides a comprehensive review of the existing literature, highlighting key developments and research trends relevant to this work.

Initiatives for transmitting and storing medical information are varied and have been extensively studied. One common approach is the centralization of medical data within non-distributed systems, where security must be concentrated at a single point to manage and protect all medical information transmitted across the network. [

12,

13]. There are both public and private initiatives that seek to achieve this objective [

14]. However, the user or patient has no guarantees regarding the security of their medical information, and in most cases, it is difficult to prove its origin [

15].

Some initiatives have sought to use DLT [

16,

17,

18] and Blockchain [

19,

20,

21,

22] technologies to carry out communication between health companies and the government. Other initiatives already have greater maturity on the subject. Thus, in 2019, Deloitte published a framework for the use of blockchain (see [

23]), which can be used in the health market to solve problems related to the per capita cost of medical care, improve the health of the population and offer a better experience for the patient [

24,

25]. However, within the blockchain ecosystem, these models are increasingly considered outdated and face significant challenges concerning information confidentiality [

26]. Additionally, many of these initiatives are still in the early stages of experimentation, highlighting the need for a more thorough assessment of their maturity and effectiveness.

On the other hand, the development of integration protocols for medical systems has progressed, with HL7 [

27] emerging as the most commercially valuable medical protocol today. HL7 defines standards and domains for use in healthcare communication, providing a robust solution for interoperability challenges. However, despite its effectiveness in addressing these issues, HL7 alone does not fully ensure the confidentiality of the medical data being transmitted.

Finally, blockchain and DLT have the potential to revolutionize the healthcare industry by improving the security, efficiency, and transparency of healthcare-related processes. As follows, some initiatives to use these technologies are described that could be used in the healthcare industry:

Medical records management: Blockchain and DLT can be used to securely store and manage electronic medical records (EMRs). The decentralized nature and cryptographic security of these technologies make them well-suited for storing sensitive medical data.

Clinical trial management: Blockchain and DLT can be used to track and verify the progress of clinical trials, ensuring that data is accurately recorded and that the trials are conducted ethically.

Supply chain management: Blockchain and DLT can be used to track the movement of pharmaceuticals and other medical supplies through the supply chain, ensuring that they are not tampered with and that they are delivered to the intended recipient.

Medical research: Blockchain and DLT can be used to securely store and share data from medical research, enabling researchers to collaborate more effectively and accelerate the pace of discovery.

Telemedicine: Blockchain and DLT can be used to securely store and access medical data for telemedicine consultations, enabling healthcare providers to deliver care remotely.

Despite the progress in utilizing blockchain and DLT technologies in healthcare, significant gaps remain in the existing literature. Current models and protocols, while addressing interoperability and some security concerns, often fail to fully ensure the confidentiality of medical data. Additionally, many initiatives are still in their experimental stages, with limited evaluation of their technological maturity and real-world applicability. This is where our work contributes by not only evaluating the technological feasibility of Corda DLT within the healthcare sector but also by addressing specific architectural and programming aspects through the development of a CorDapp.

3. Corda Basic Concepts

This section explores the fundamental components of Corda, including its network architecture, states, transactions, smart contracts, flows, and notaries.

As a private distributed ledger technology (DLT), Corda incorporates a workflow messaging network, facilitating the creation of decentralized applications referred to as CorDapps. [

28]. These CorDapps are developed for specific purposes to incorporate the functionalities into the DLT system. In general, blockchain is just one type of DLT [

29].

Corda’s main goal was to help regulated financial institutions with interoperability processes [

28]. Corda also provides dependable scalability, state consistency, transaction privacy, and workflow adaptability, making it suitable for various business applications, including trade finance, supply chain management, healthcare, capital markets, insurance, telecommunications, and governance [

30]. Corda’s architecture follows a "need-to-know" principle. For instance, if node A and node B execute a transaction, node C remains unaware. The Corda Notary validates the transaction, and if approved, an immutable record is created in the separate databases of nodes A and B, reflecting Corda’s decentralized database structure [

28], so in this way, the immutable record of the transaction carried out will be accessible only to the nodes involved, that is, node A and B.

3.1. State

In Corda, a state represents a unit of shared information on the ledger. A state consists of data and a set of rules governing the data, which are known as a smart contract. In general, states are used to track the ownership and transfer of assets on the Corda ledger. For instance, if we want to track the ownership of a financial asset, we can create a state that represents the asset and the current owner. When the ownership of the asset changes, we can create a new state that reflects the new ownership.

Transactions in Corda create and update states. When a transaction is proposed, the nodes on the network verify that it is valid and, if it is, update the ledger to reflect the changes specified in the transaction.

States are stored in a node’s vault, which is a database of states that the node is aware of. The vault is used to track the history of states and to enable the node to access the current state of an asset. Further, states are identified by a unique identifier called a linear identifier, which is assigned by the smart contract when the state is created. The linear identifier is used to track the history of a state and to ensure that a state is not created or updated multiple times.

States can be shared with other nodes on the network by including them as inputs or outputs in a transaction. When a state is included as an input in a transaction, it is consumed and can no longer be used in future transactions. On the other hand, when a state is included as an output in a transaction, it is created and becomes available for use in future transactions.

3.2. Transaction

A transaction is a unit of work that updates the ledger. It consists of one or more inputs (states that are being consumed or modified by the transaction), outputs (new states that are being created by the transaction), and commands (specifying the actions that are being taken by the transaction, such as issuing a new asset or transferring an existing asset).

Transactions are proposed by nodes on the Corda network and are verified by the other nodes on the network before they are committed to the ledger. When a transaction is proposed, the nodes on the network verify that the transaction is valid, which includes checking that the input states are valid and have not been modified and that the output states are valid and comply with the rules specified in the smart contract. Thus, if the transaction is valid, the nodes on the network update the ledger to reflect the changes specified in the transaction, otherwise, if the transaction is not valid, it is rejected and the ledger is not updated.

Transactions in Corda are signed by the parties involved to ensure their authenticity and prevent tampering. The signatures verify the parties’ identities and ensure that the transaction has not been modified. Further, transactions in Corda are recorded on the ledger in an append-only manner, which means that once a transaction is committed to the ledger, it cannot be modified or deleted. This ensures the integrity and immutability of the ledger.

3.3. Smart Contract

In Corda, a smart contract is a set of rules that governs the data in a state. A smart contract defines the conditions that must be satisfied for a state to be valid and the actions that can be taken with the state. For example, consider a smart contract that governs the ownership and transfer of a financial asset. The smart contract might define a rule that the asset can only be transferred to a new owner if the current owner has signed the transaction. Thus, the smart contract would implement this rule by checking that the signature of the current owner is present in the transaction.

Further, smart contracts are used to enforce the rules of the ledger and ensure the integrity of the data on the ledger. When a transaction is proposed, the nodes on the network verify that it is valid and complies with the rules specified in the smart contract. If the transaction is not valid, it is rejected, and the ledger is not updated.

3.4. Flow

A flow is a piece of code that represents a business process or communication between two or more nodes on the network. Flows coordinate the execution of a task or a series of tasks on the Corda ledger. For instance, imagine a flow that coordinates the transfer of a financial asset between two nodes. This flow could involve steps such as verifying the validity of the asset, requesting the current owner’s signature, creating a transaction to transfer the asset, and sending the transaction to the new owner for validation.

Further, flows are used to automate the execution of business processes and to coordinate the communication between nodes on the network. They are an important mechanism for automating the execution of tasks on the Corda ledger and for enabling the nodes on the network to collaborate and achieve a common goal. Finally, flows are executed asynchronously and can be invoked by other flows or by external clients.

3.5. Notary

In Corda, a notary is a node on the network that provides a trusted service to ensure the uniqueness of states on the ledger. The notary is responsible for preventing double-spending of assets and ensuring the ledger’s integrity. Thus, when a transaction is proposed, the notary checks the inputs of the transaction to ensure that they are unique and have not been used in a previous transaction. If the inputs are unique, the notary signs the transaction to confirm their uniqueness, allowing the transaction to be committed to the ledger.

Besides, the notary acts as a gatekeeper for the ledger, ensuring that only valid and unique transactions are committed to it. This helps prevent fraud and maintain the integrity and consistency of the data on the ledger.

4. Design and Development of CorDapp in the Health Ecosystem

This section explores how Corda DLT technology can address the challenges of managing and transferring medical records, proposing a common platform for secure and efficient data sharing across healthcare entities.

In the healthcare ecosystem, medical record systems vary widely, encompassing both paper-based and electronic formats, each with its own standards for data representation and sharing [

13]. However, this vast amount of critical medical information is often scattered across multiple entities, including hospitals, clinics, doctors’ offices, laboratories, pharmacies, and patients themselves. Unfortunately, this information is frequently inaccessible when it is most needed, leading to significant costs and, in some cases, even loss of life. Consequently, the portability and interoperability of medical data present major challenges, as data transfers between different entities or stakeholders often fail. Additionally, medical data is frequently lost by both patients and healthcare providers.

It is often necessary to transfer the medical data of a patient from one hospital or clinic to another for better care, so the question arises as to how medical data can be transmitted safely, with the patient’s permission, without having to regenerate them and without the risk of losing information? To answer this question, the use of Corda DLT technology in the healthcare ecosystem is proposed in this work once Corda is a private DLT that allows transactions only between the participating nodes, which guarantees the privacy of the information.

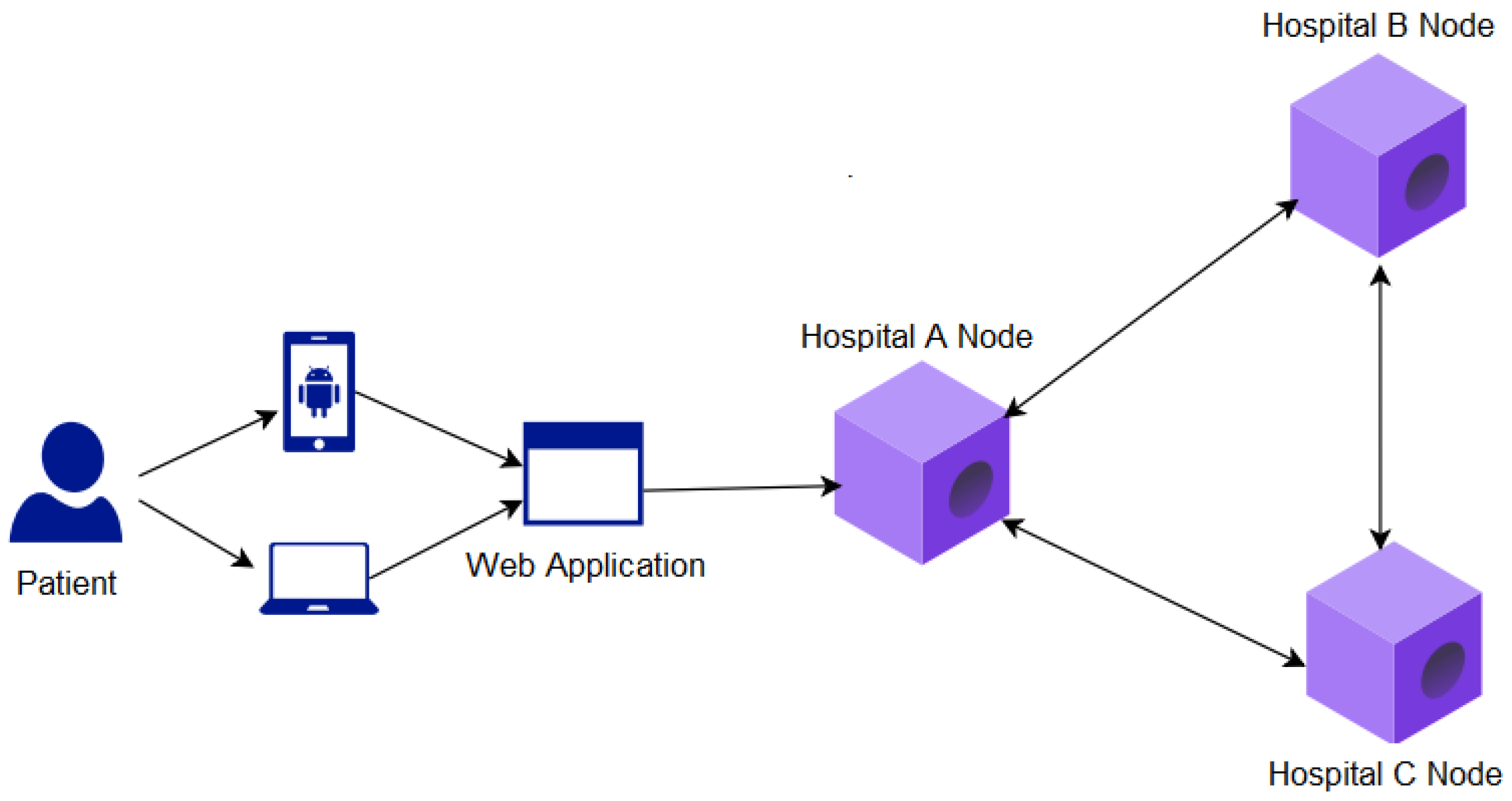

In this way, the present proposal is to create a common platform based on Corda DLT where hospitals, clinics, offices, laboratories, pharmacies, and research institutes can upload and share patient data always with their authorization. Thus, in this proof-of-concept proposal for the use of Corda, a network composed of the following participants has been considered:

Hospital A,

Hospital B and

Hospital C,

where each participant will have their own Corda node hosted in their environment, be it local or in the cloud. These nodes are integrated into the Corda network, which allows the transfer of medical data between the participating nodes; in this way, relevant information can be shared between the nodes quickly without loss of information and duplication. In addition, by inherence, the Corda network provides identity and service verification to ensure that participating nodes can operate on the network in complete safety [

28].

Figure 1 shows the proposed Corda network with the participating nodes.

During the development of CorDapps to be executed on each node within the Corda network, the design of the flows was the initial step. To illustrate this process, consider the following example, which demonstrates how a patient’s flow can be established to enable communication between two or more nodes within the Corda network:

Patient A records his medical history at Hospital A.

Hospital A registers Patient A’s information on the distributed ledger through its node.

Each time Patient A has an appointment with a doctor at Hospital A, the medical data is updated on the ledger.

If a doctor at Hospital A identifies a serious issue and recommends that Patient A undergo tests at the Laboratory of Hospital B and later consult a specialist at Hospital C,

Hospital A, Hospital B’s Laboratory, and Hospital C now have shared information, allowing them to access and update Patient A’s medical history on the ledger.

Patient A can be directly transferred to Hospital C, where they can receive immediate care since all of their medical records are accessible through the decentralized ledger network.

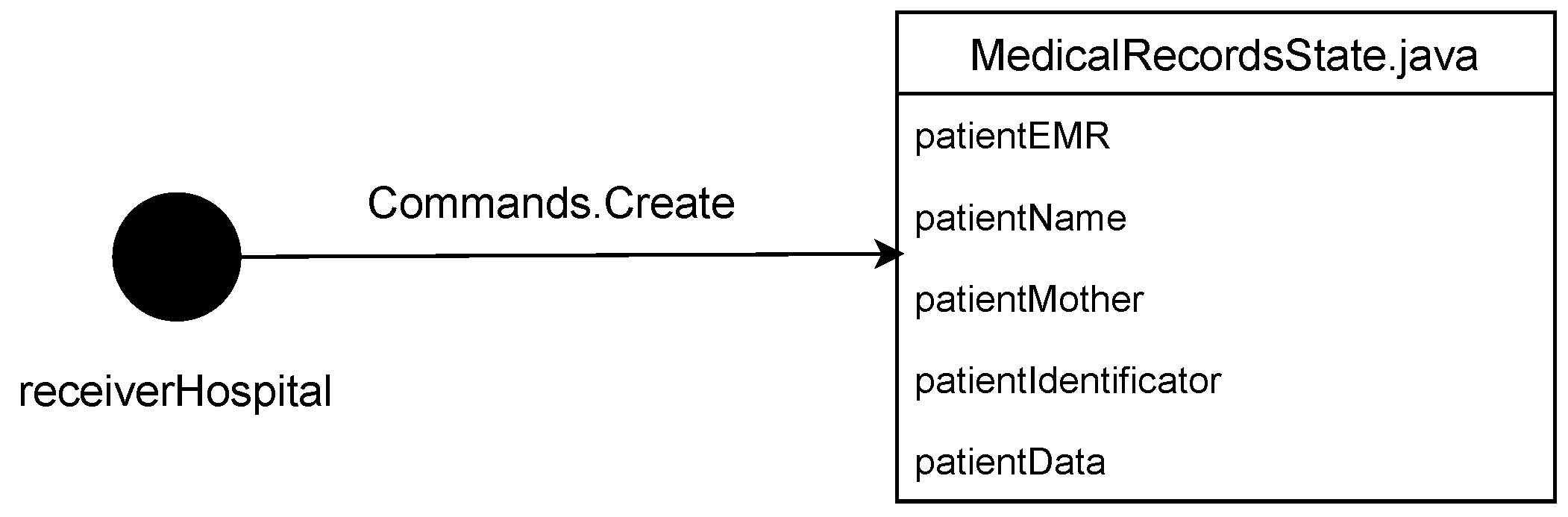

Once the flow of a given patient has been defined in the Corda network, the state MedicalRecordsState is generated, which represents the medical history of a patient and will be shared among the participating nodes of the network. The variables used in the MedicalRecordsState are the following:

patientEMR represents the unique identifier of the patient within the node.

patientName represents the name of the patient.

patientMother represents the name of the patient’s mother.

patientIdentifier represents the patient’s identity document.

patientData represents the patient’s medical data, for example, information about a disease.

receiverHospital It is the participating node of the network that will receive the patient’s information.

requestHospital It is the participating node of the network that requests patient information.

Once the MedicalRecordsState state is defined, the CorDapp will include the flows defined in the following subsections:

4.1. Medical Record Creation Flow

The medical record is created by the flow named FillMedicalRecords, which, when executed by the receiverHospital will create new states of type MedicalRecordsState for each new patient with the variables defined previously. Thus, each node will be able to save the medical history in its respective database and share it with another node through a request.

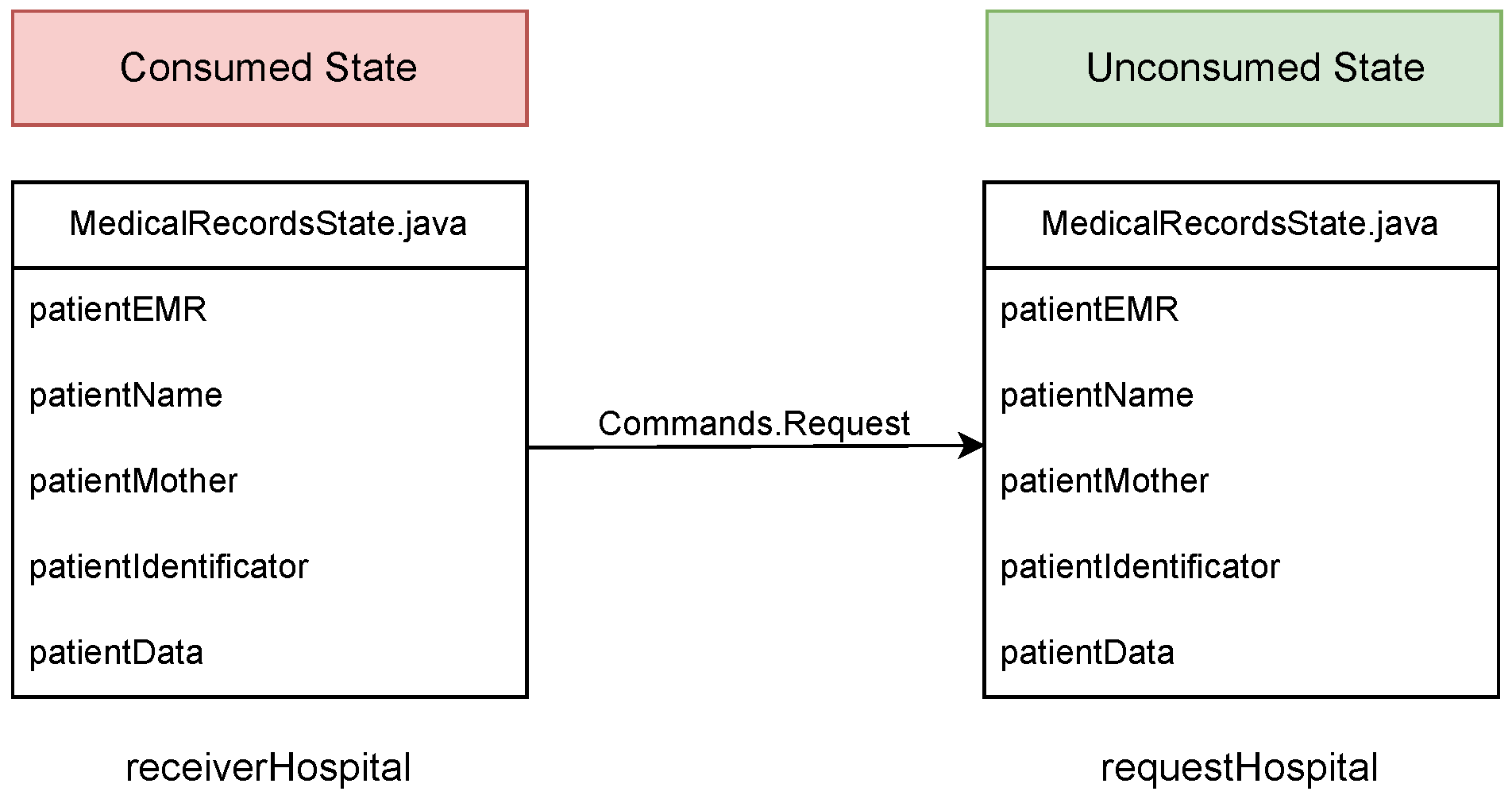

4.2. Medical Record Sharing Flow

It is represented by the flow RequestPatientRecords, and it will always be executed by the requestHospital node, which will request the medical history of a given patient. Once the Request PatientRecords is executed, there will be a response flow named ResponderPatientRecords, within which the following two scenarios are possible:

-

A successful response will result in the patient’s medical history being shared with the request Hospital node. Consequently, both the receiverHospital and the

requestHospital will have the same version of the MedicalRecordsState, stored in their respective databases.

Unsuccessful response where an exception will be thrown indicating the prohibition of sharing the state MedicalRecordsState of the patient.

For nodes participating in a transaction to save a patient’s medical record, represented by the

MedicalRecordsState, in their databases during the execution of flows, certain business rules must be met. These rules are essential to validate whether the consumption and sharing of the

MedicalRecordsState are appropriate and make sense within the context of the transaction. As previously mentioned, in Corda, smart contracts govern the consumption or transition of states and represent sharing validation rules that must be executed by participating nodes [

30]. In this way, the smart contract named

MedicalRecordsContract, which governs the transition of the state

MedicalRecordsState inside a flow, was developed. Note that the execution of the rules of the

MedicalRecordsContract must be deterministic so that the participating nodes can reach the same conclusion.

The smart contract MedicalRecordsContract is composed by the definition of two commands that represent the intention of creating the MedicalRecordsState given by FillMedicalRecords and the sharing of MedicalRecordsState among the nodes when the RequestMedicalRecords flow is executed. Thus, these two commands are described below.

4.3. Create Command

Represented by

Commands.Create and linked to the

FillMedicalRecords flow, this process validates the creation of the

MedicalRecordsState for the first time. As a result, a completely new

MedicalRecordsState is generated for each patient who records their medical history for the first time. This process is illustrated in

Figure 2.

4.4. Requisition Command

Represented by Commands.Request and associated both to the flow

RequestPatientRecords and

ResponderPatientRecords, this command allows to validate whether both

receiverHospital and

requestHospital agree to share the state named as

MedicalRecordsState for which, both nodes must sign the transaction through their respective public keys. Once this validation is complete, the

Medical Records State can be shared and stored in the database of the

receiverHospital and

requestHospital nodes, respectively. A diagram of this command is shown in

Figure 3.

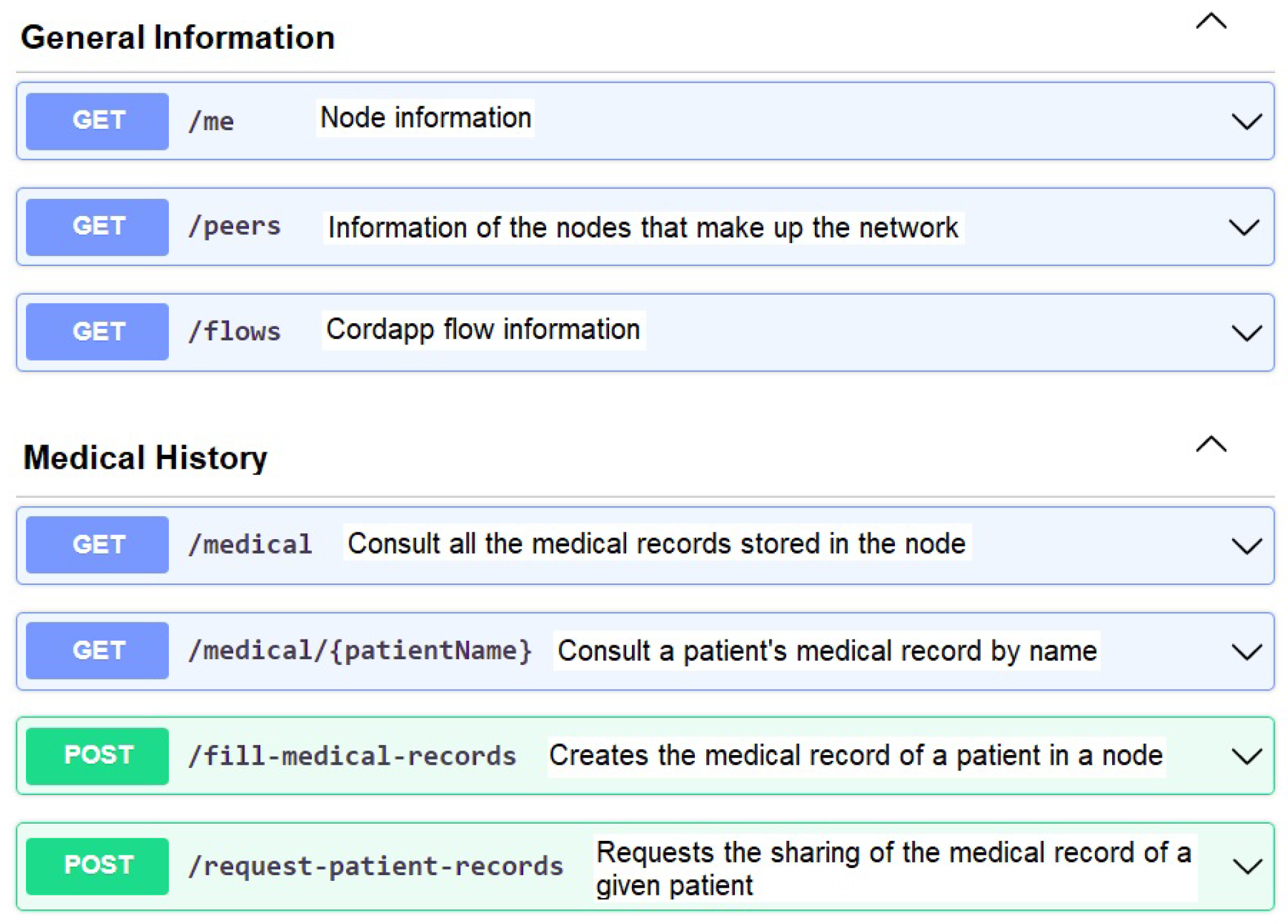

4.5. Web Server

There are three ways to connect to Corda nodes, which are through their shells with Secure Socket Shell (SSH), through a Remote Procedure Call (RPC) client, or a web server. In general, the Corda template, on which the proposed CorDapp was based and created, includes a spring web server and is the one that allows connecting to the node via RPC.

In this way, seven application programming interfaces (API) were developed in Swagger

2, and they are shown in

Figure 4, where it can be seen that three APIs refer to queries (GET) of general information of the nodes and four APIs refer to the medical history within which the query APIs (GET) and the APIs of publication and requisition (POST) of medical records are shown.

4.6. Running the CorDapp on the Corda network

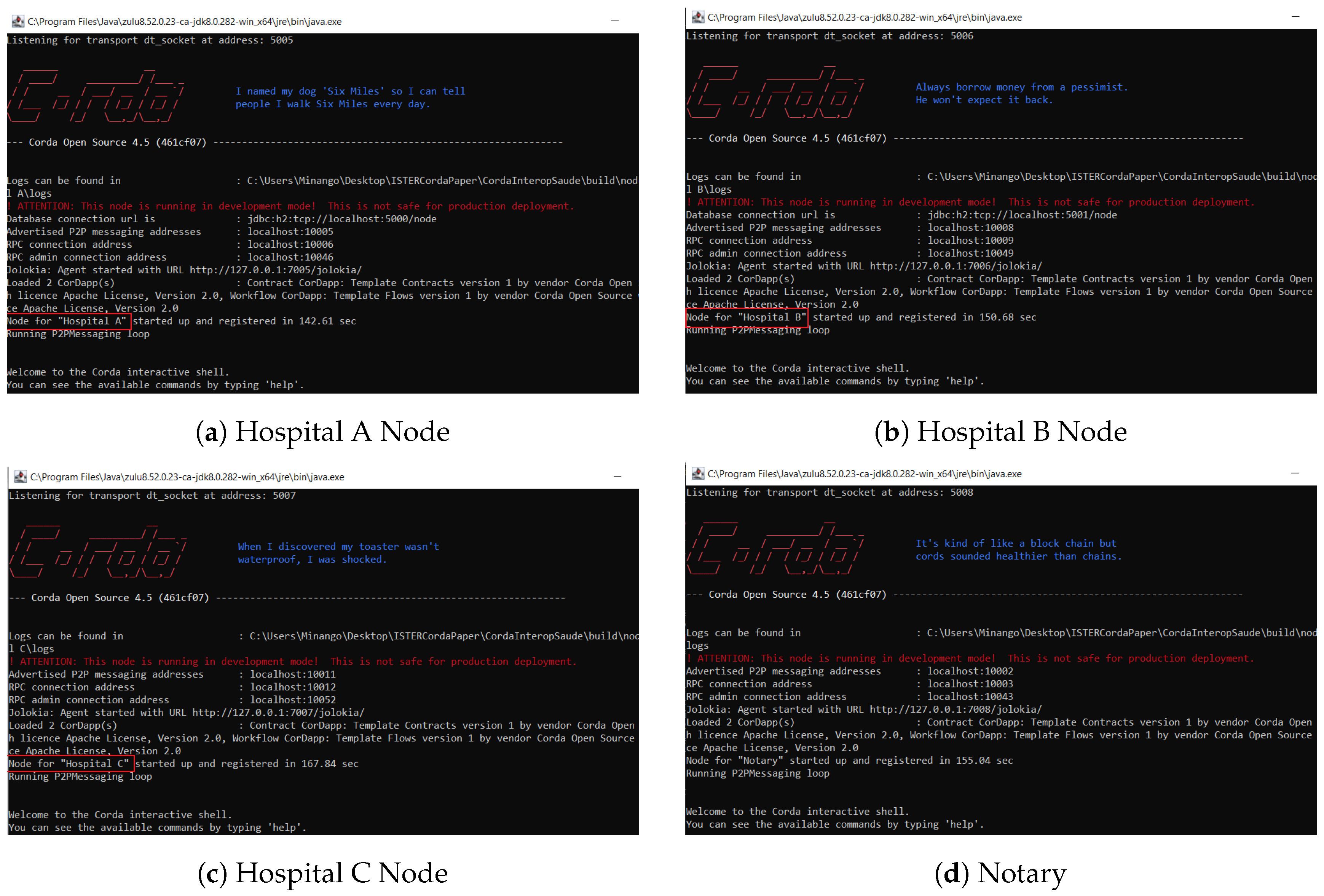

In

Figure 5, four terminal windows corresponding to the nodes of Hospital A, Hospital B, Hospital C, and the Notary are shown. These terminals run on a Java Virtual Machine (JVM), as Corda is built on the JVM, which it uses to execute code and manage the runtime environment. Additionally, the name assigned to each node in the Corda network is highlighted within the red box of each terminal.

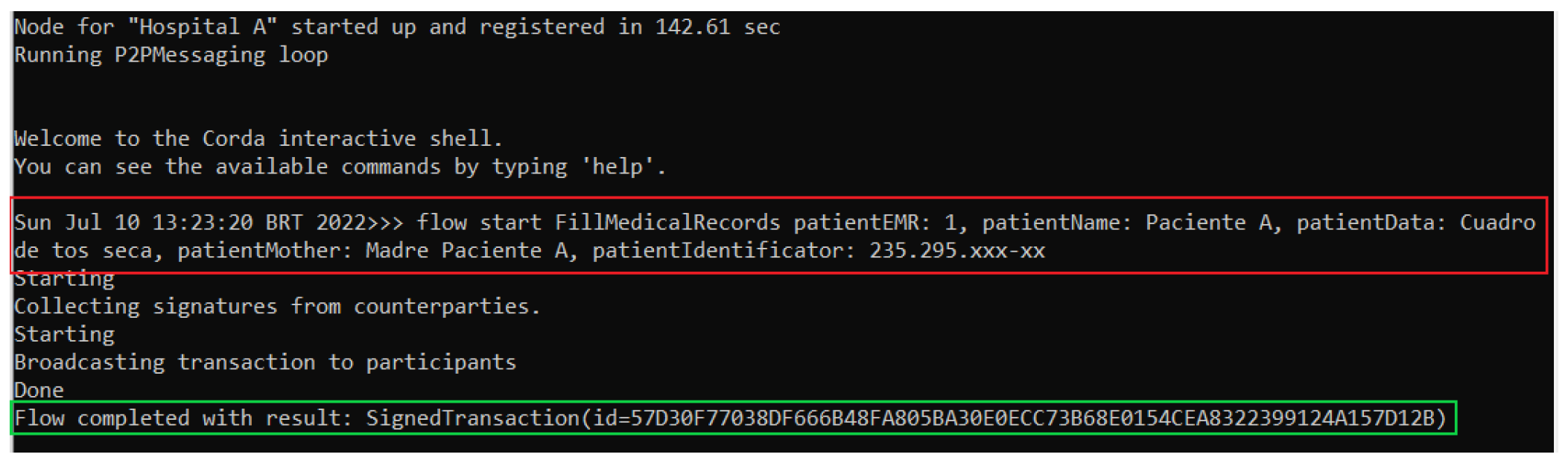

Once each node has started, as seen in

Figure 5, by considering the node corresponding to Hospital A, the

FillMedicalRecords flow can be executed, which will create the

MedicalRecordsState state with the parameters passed in the call to the flow, as can be seen in the red box of

Figure 6. In case the call to the

FillMedicalRecords flow is successful, that is, the

MedicalRecordsState state was created, the ledger will report as a response the hash of the transaction resulting from the

FillMedicalRecords flow as can be observed in the green box in

Figure 6.

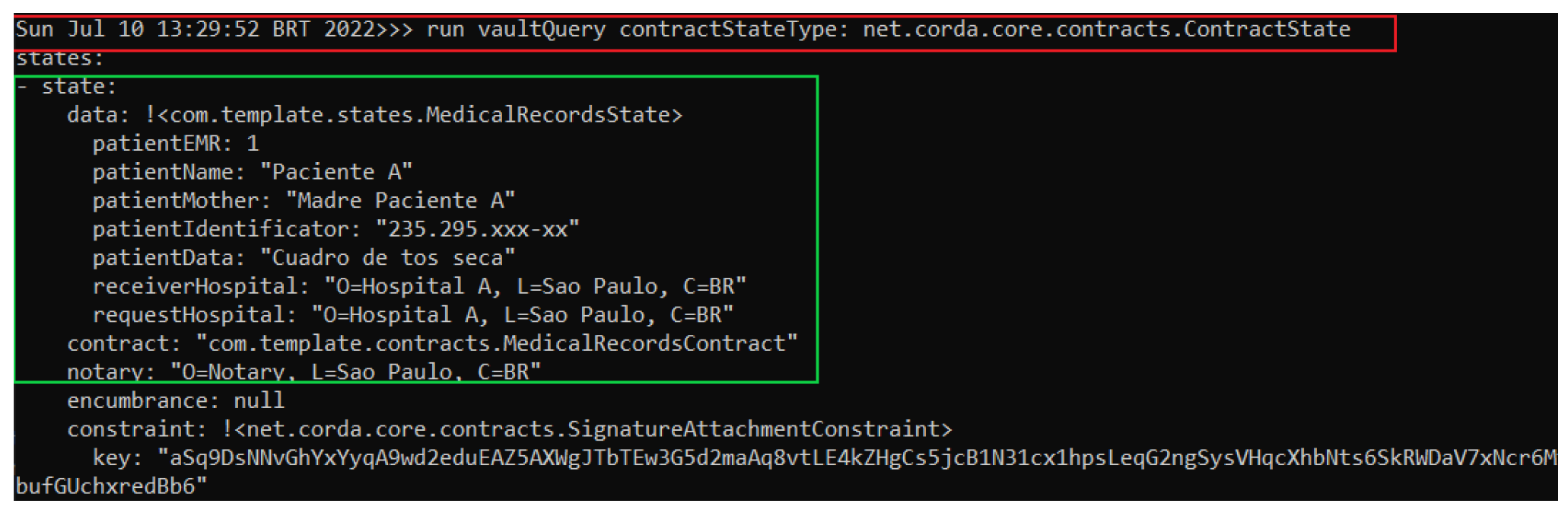

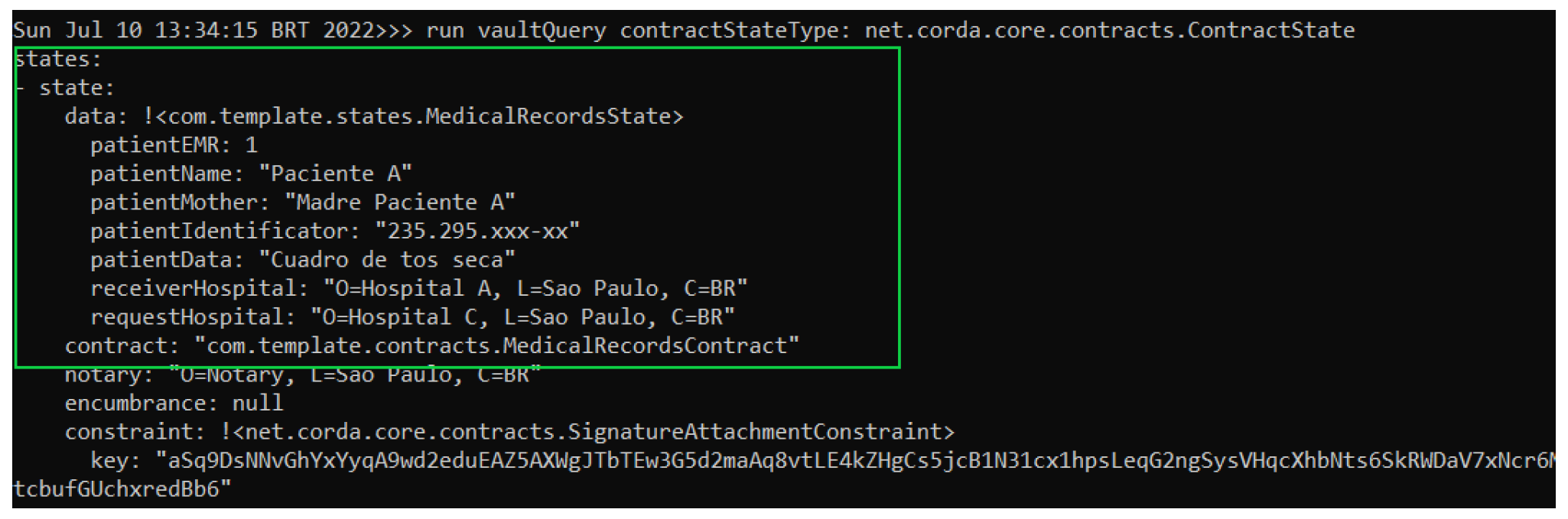

To verify that the

MedicalRecordsState status is already saved in the Hospital A node, we can perform a query in its database with the command in the red box in

Figure 6 and obtain as a result the state

MedicalRecordsState already created and represented in the green box of

Figure 7.

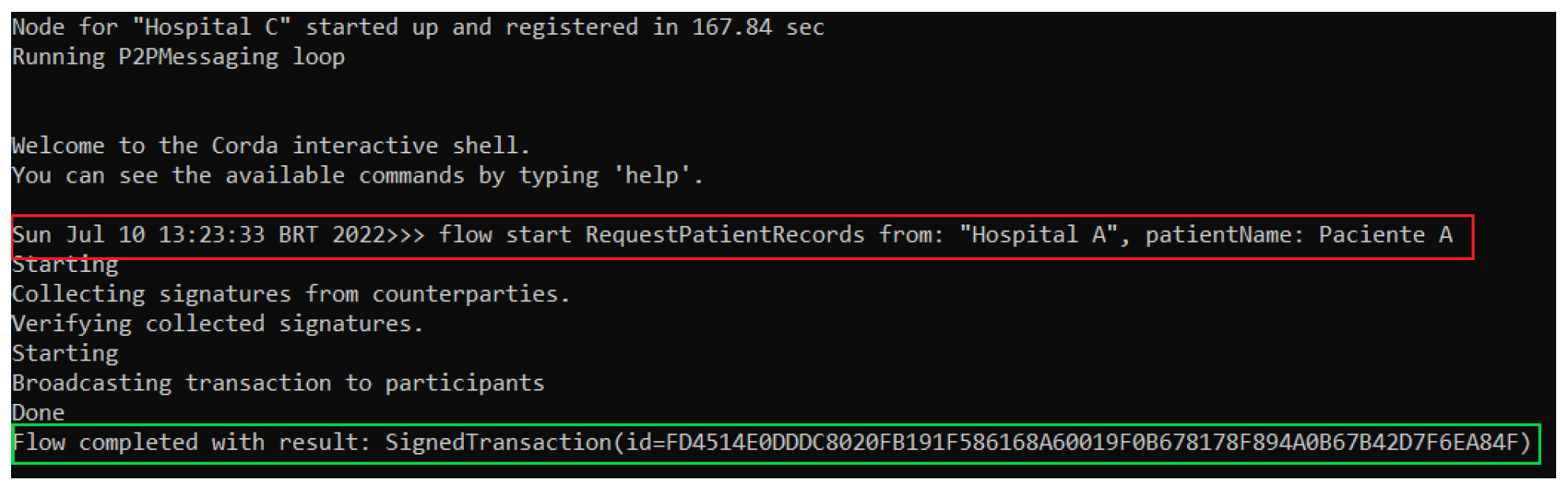

Once Patient A’s medical record, represented by the

MedicalRecordsState, is saved on the Hospital A node, it will be ready for retrieval. Assuming that Hospital C requests the

MedicalRecordsState, the

RequestPatientRecords flow is executed on the Hospital C node. passing as parameters the

requestHospital together with the name of patient A. This call can be seen in the red box of

Figure 8, resulting in the corresponding hash of said transaction shown in the green box of the same figure, which indicates the successful sharing of the

MedicalRecordsState state. In other words, both the Hospital A and Hospital C nodes have in their databases the

MedicalRecordsState without any immutability having existed.

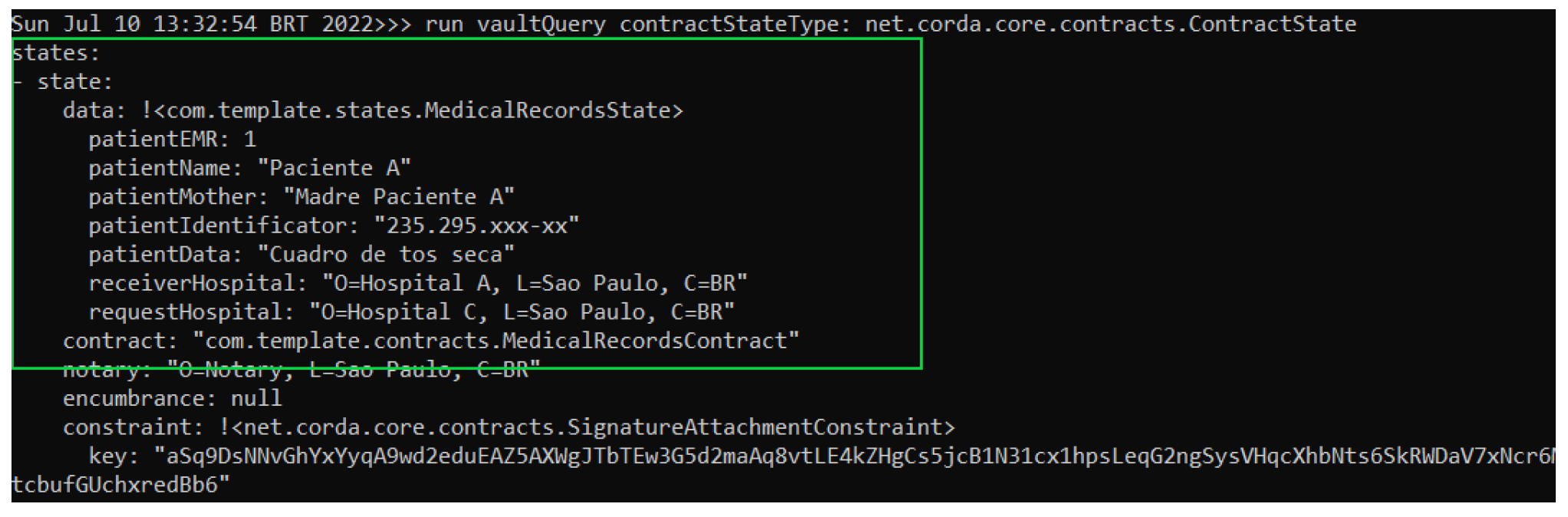

To verify that both the database of Hospital A node and Hospital C node contain the same copy of

MedicalRecordsState, a query was made in their databases. The result of this query can be viewed in the green box of

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 corresponding to the Hospital A and Hospital C nodes, respectively.

5. Testing Methodology

This section describes the performance metrics used to evaluate the proposed CorDapp, which are textitthroughput, response time, latency, error rate, CPU, and memory utilization.

5.1. Throughput

Throughput in Corda refers to the number of transactions that can be processed by the platform in a given period. The throughput of a Corda network depends on several factors, including the hardware and software configuration of the nodes, the size and complexity of the transactions, and the number of nodes participating in the network. Thus, in Corda, throughput is calculated in transactions per second (TPS) and is given by

where the total time is calculated from the sending of the first to the last transaction, including all the intervals between transactions.

Transactions are equivalent to flow calls; typically, one or more transactions are recorded by one or more nodes that make up the Corda network. In other words, TPS is defined as the amount of a certain flow completed per second. The following two types of TPS can be defined:

5.2. Response Time

Response time in Corda refers to the time it takes for a node to process a request and return a response. Thus, it corresponds to the time elapsed between the start (

) and the end (

) of a transaction and is given by

5.3. Latency

The time required to execute a task that can be consensus or communication is measured in seconds.

5.4. Error Rate

The error rate is the number of transactions not accepted by the system, which is given in terms of percentage.

5.5. CPU Utilization

It refers to the amount of CPU usage during a transaction, which may involve queries in the database of each node, creating or updating states, building the transaction, checking the rules (smart contracts) that must be followed during the transaction, signing the transaction, verify the signatures of the corresponding nodes, share the transaction with other nodes involved in the transaction, and save the transaction in the databases of the communicating nodes.

5.6. Memory Usage

Represents the amount of memory used during a transaction based on the number of flows, the number of RPC call connections, and so on.

5.7. Performance Analysis Tool

The JMeter tool, an open-source testing application that analyzes and measures software performance, was used to evaluate the performance metrics of the proposed CorDapp. JMeter is entirely developed in Java and allows load and stress tests to be carried out, to which CorDapp was submitted. Thus, JMeter can be used to test the performance and reliability of the Corda network. JMeter is designed to simulate many users making requests to a system and can be used to measure the system’s response time and throughput under different load conditions.

5.7.1. Load Tests

This test models the expected use of CorDapp through simulations of simultaneous access from several users or patients to CorDapp flows. Load tests can evaluate the performance and reliability of the Corda network under different load conditions. Further, load tests in Corda can be used to identify bottlenecks and optimize the network’s performance.

5.7.2. Stress Tests

Once the nodes have a maximum load capacity, they respond slowly and cause errors when the load exceeds the limit. The purpose of stress tests is to find the maximum load that the node can support.

5.8. Definition of Performance Tests

Two types of requests are utilized in the load and stress tests conducted during the CorDapp performance evaluation, presented in

Figure 11 and described below.

5.8.1. Simultaneous Requests from Multiple Users

In this situation, several users simultaneously execute the

FillMedicalRecords flow, that is, several patients register their medical history simultaneously in a given node as shown in

Figure 11.

5.8.2. Simultaneous Requests Between Nodes

It is performed in the communication among nodes when one requests information from other nodes for a certain period. Thus, the flow

RequestPatientRecords is executed several times, that is, the medical history of a given patient stored in the hospital A node is requested several times by the hospital B node as seen in

Figure 11.

6. Performance Results

This section presents the evaluation of the results. Two scenarios were considered for collecting CorDapp performance metrics: one within a local network and one in the cloud. These scenarios are briefly described below.

6.1. Local Network

It is known that the performance of a computer is limited by its processing power. However, running a Corda network locally allows us to compare and discover some connections between parameters. The Corda network and CorDapp were tested locally on a computer with the characteristics described in

Table 1.

6.2. Cloud Network (Cluster)

A cluster consists of interconnected servers where the computational power of a cluster is highly dependent on the number of computers it contains. The cluster used for benchmarking consists of three fully connected nodes located on the Google Cloud Computing platform

3 (GCP) with the characteristics presented in

Table 1.

6.3. Throughput

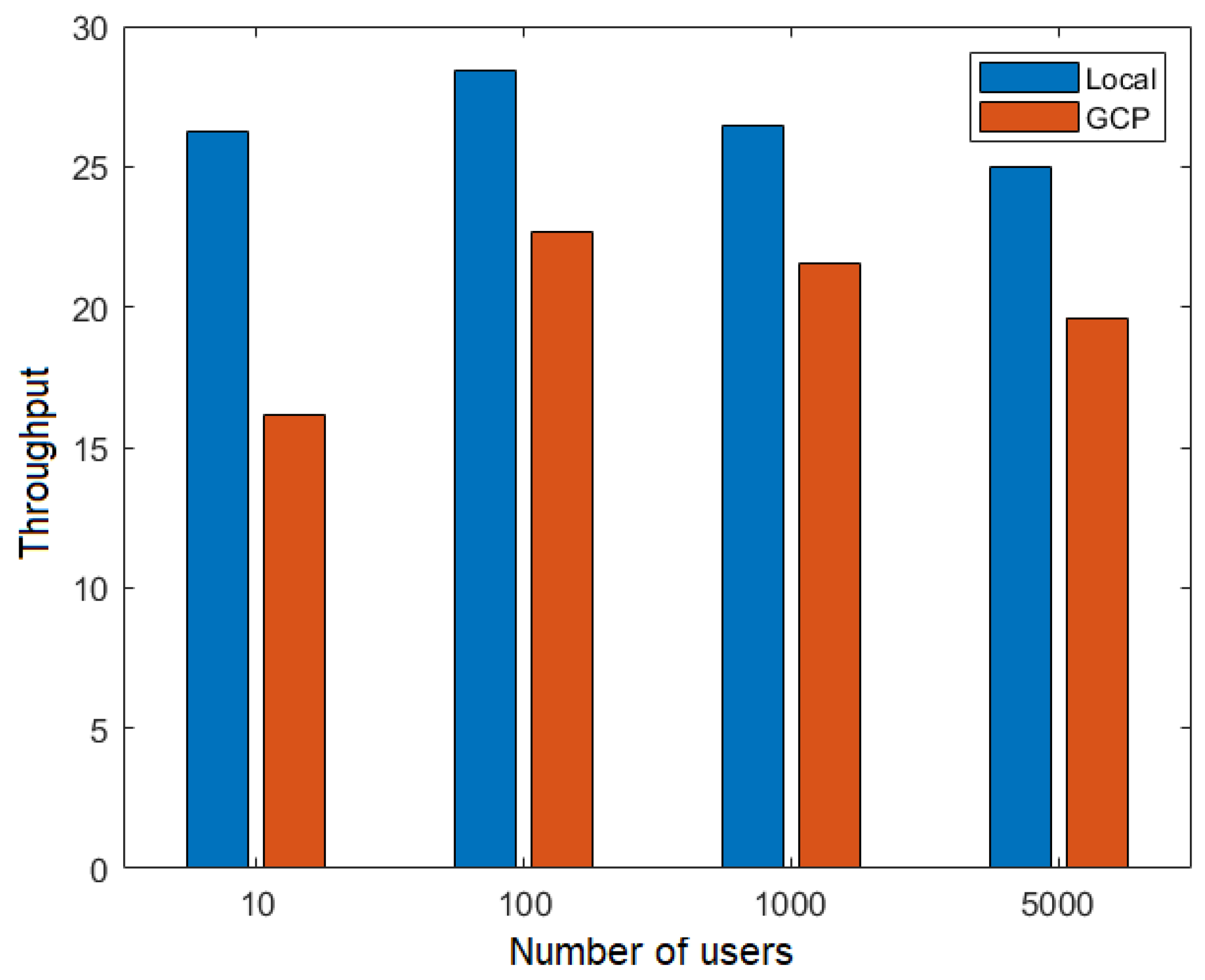

Two throughput scenarios were evaluated: the throughput that a node can achieve (TPS node) during the execution of the flow FillMedicalRecords and the throughput of the network as a whole (TPS network) through the RequestPatientRecords flow.

Figure 12 shows the comparison between the local network and the cloud network (GCP) in terms of throughput for different number of users in the execution of the flow

FillMedicalRecords, that is, TPS node. From this figure, it is evident that the local network achieves higher throughput. However, this comparison is somewhat unfair since the local network operates on the same computer, making it a hypothetical scenario.

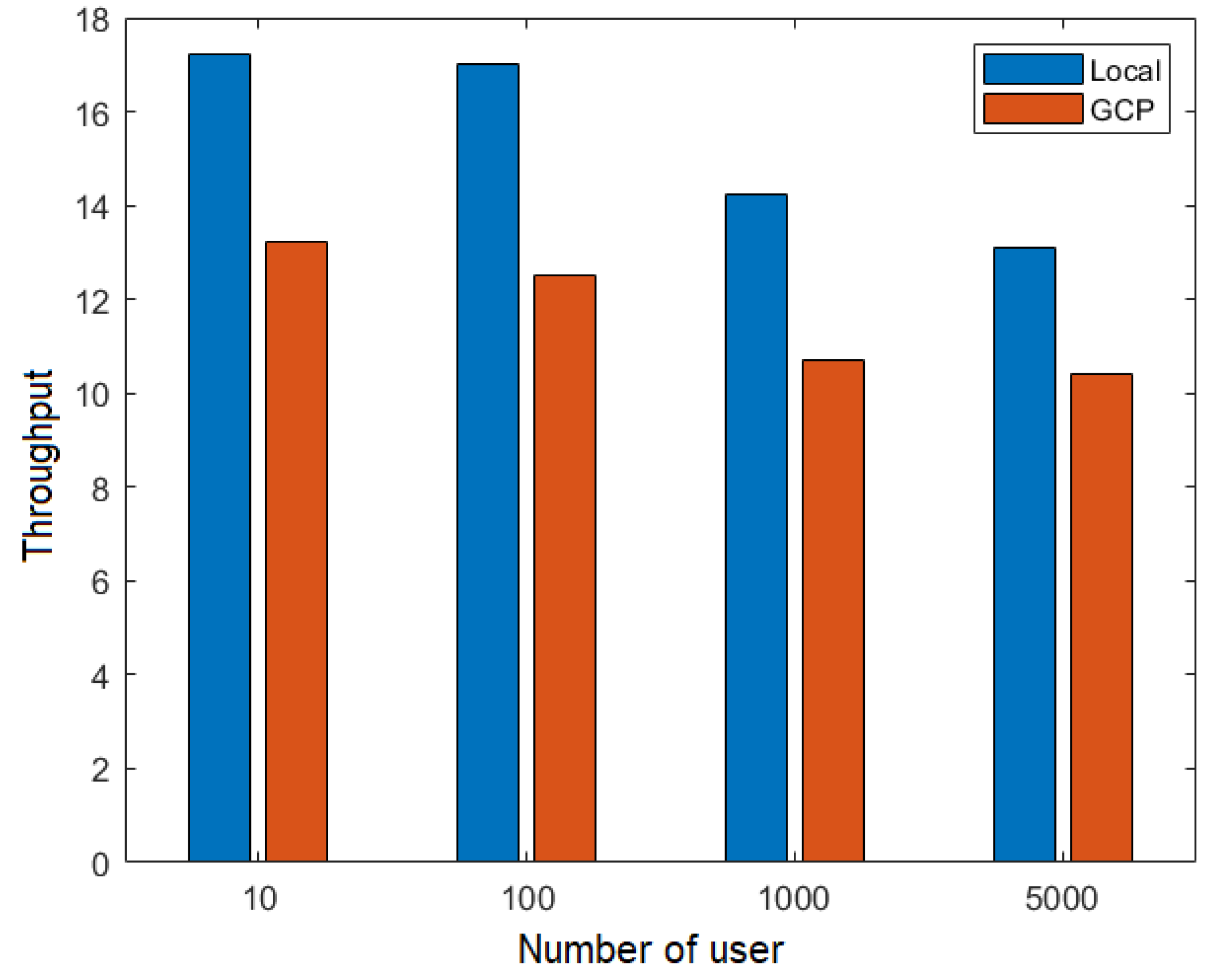

On the other hand,

Figure 13 shows the throughput for different numbers of users in the execution of the flow

RequestPatientRecords, TPS network. Compared with

Figure 12, we observe a reduction in throughput once more than one node participates in the transaction in the TPS network.

Table 2 summarizes the average throughput of the two scenarios, TPS node, and TPS network, previously evaluated.

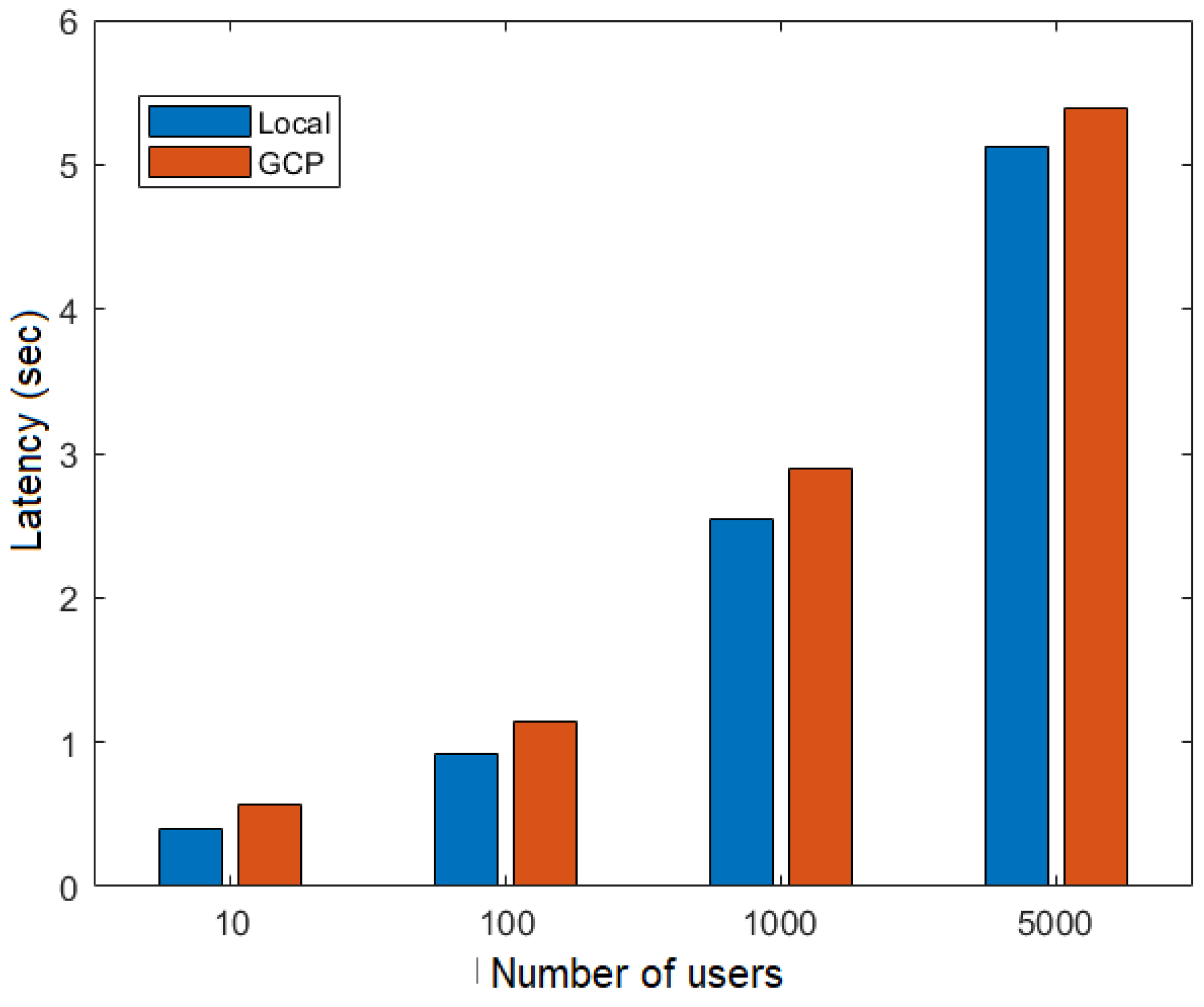

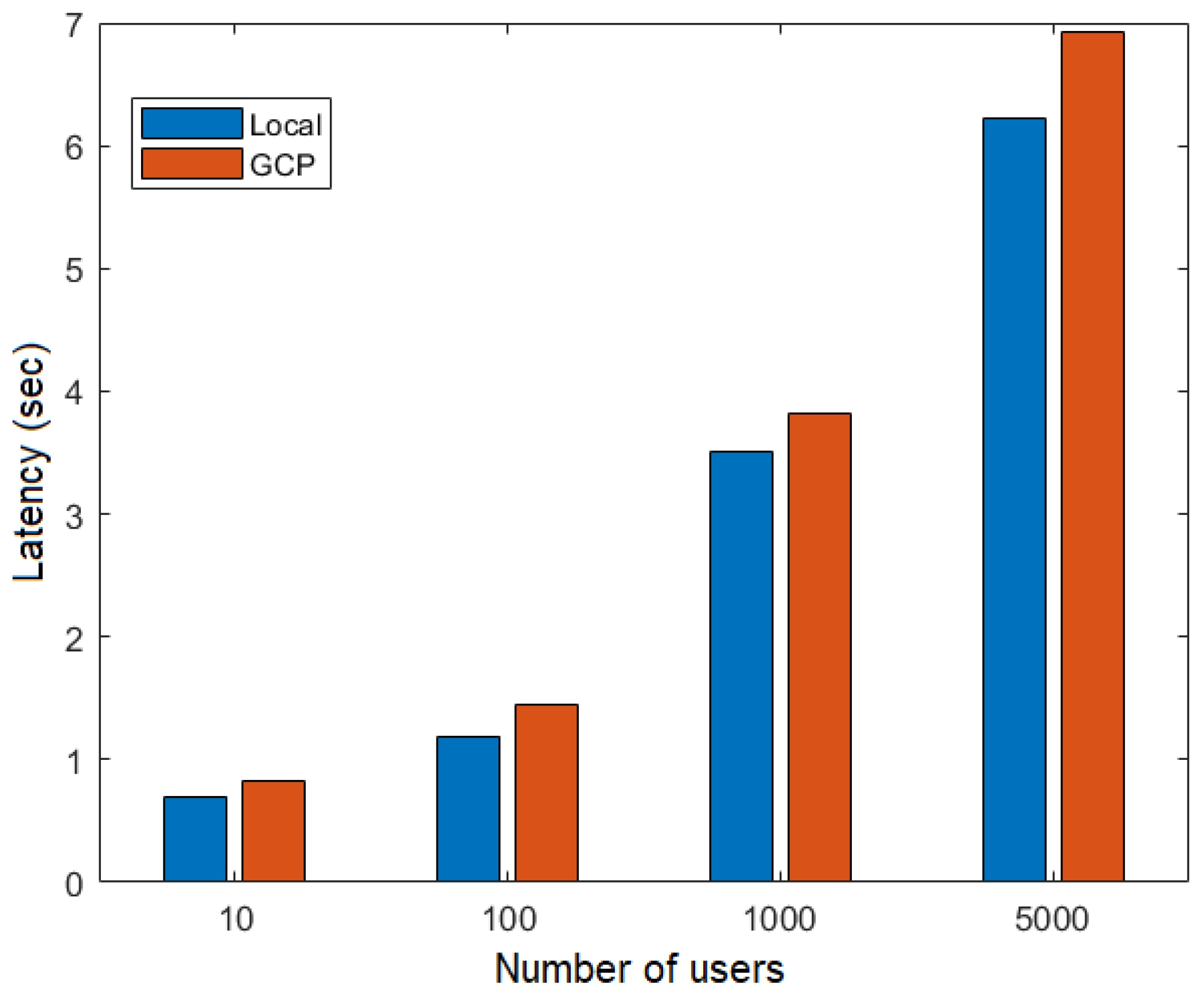

6.4. Latency

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 show the latency as a function of the number of users obtained in the execution of the flow

FillMedicalRecords and

RequestPatientRecords respectively both on the local network and in the cloud (GCP). These figures show that latency increases as more simultaneous users are added to the network. Additionally, latency is higher in the

RequestPatientRecords scenario (

Figure 15), as it involves more than one participating node.

Table 3 summarizes the average latency during the execution of the

FillMedicalRecords and

RequestPatientRecords.

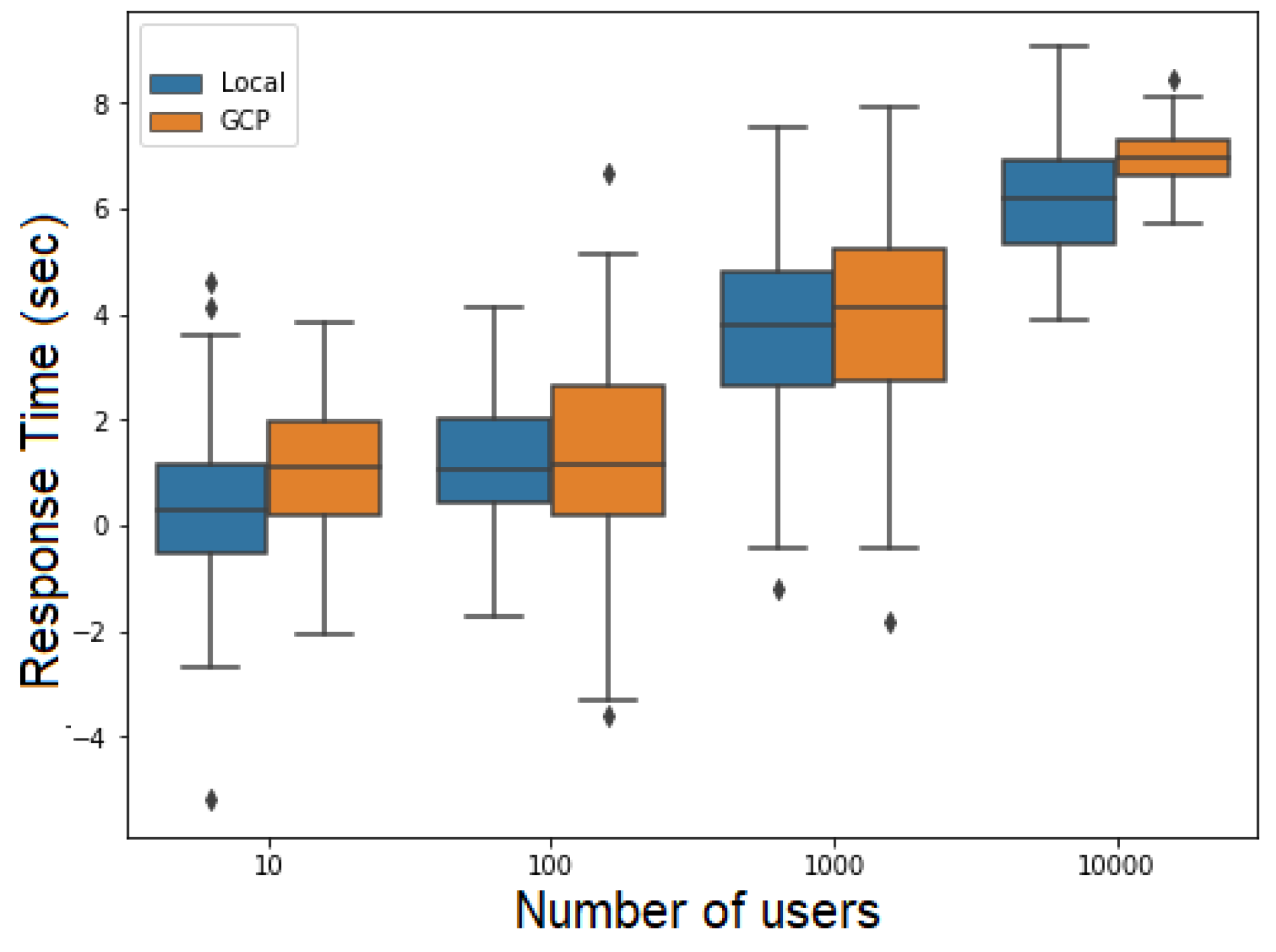

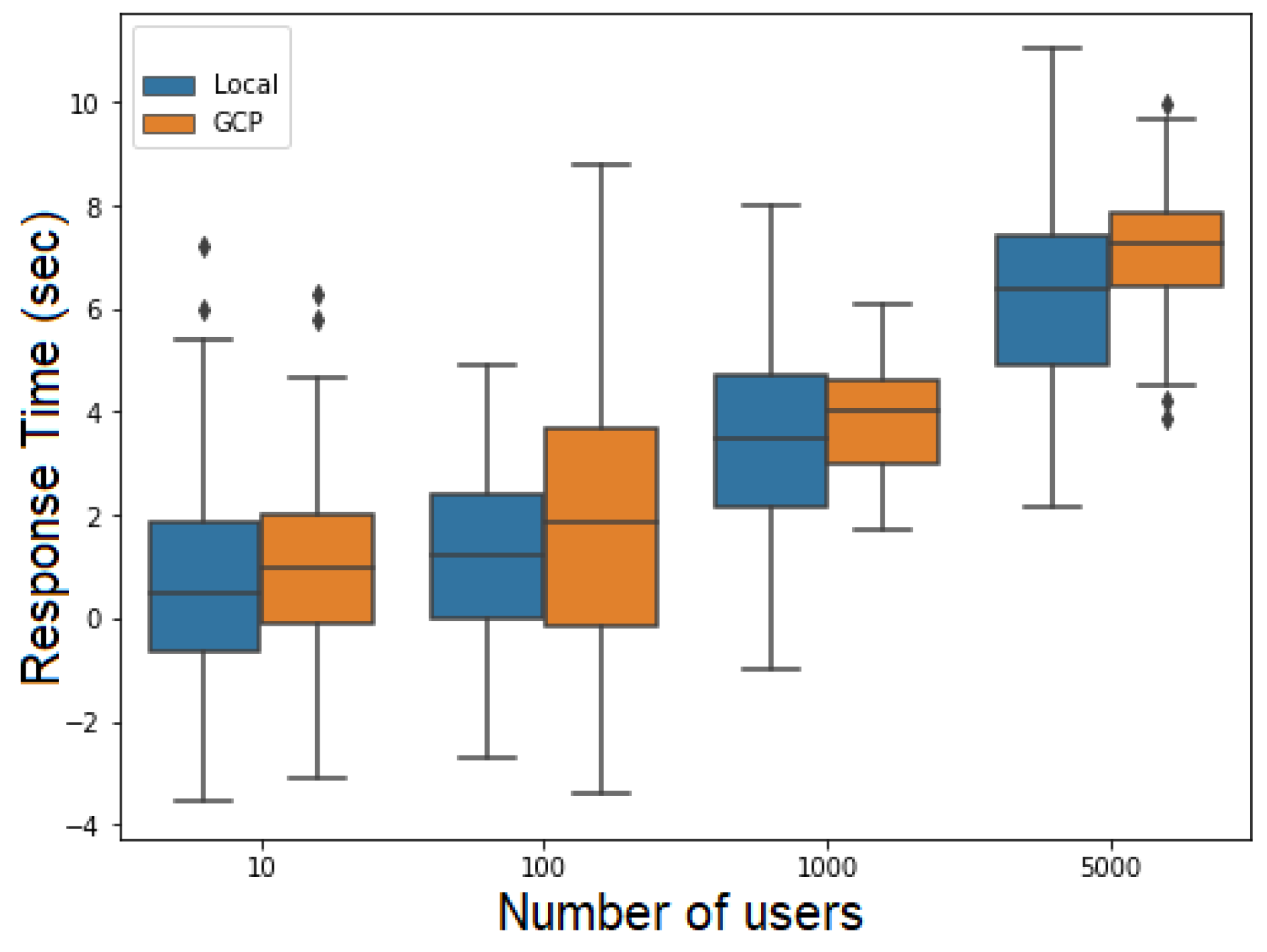

6.5. Response Time

Figurs

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 present the response time depending on the number of users for both the flow of

FillMedicalRecords and

RequestPatientRecords respectively. The response time samples in both figures are centered around their mean values, with only a few outliers. This suggests that the response times follow a Gaussian distribution.

6.6. Error Rate

The error rate was previously defined as the percentage of failed transactions/total number of transactions. This metric was obtained through stress tests.

Table 4 presents the average error rate obtained during the execution of the stress test for the flow

FillMedicalRecords and RequestPatientRecords. From this table, it can be concluded that the GCP network has a higher transaction error rate in both flows. Also, it should be noted that the execution of the RequestPatientRecords is the one that presented a higher error rate compared to the flow FillMedicalRecords.

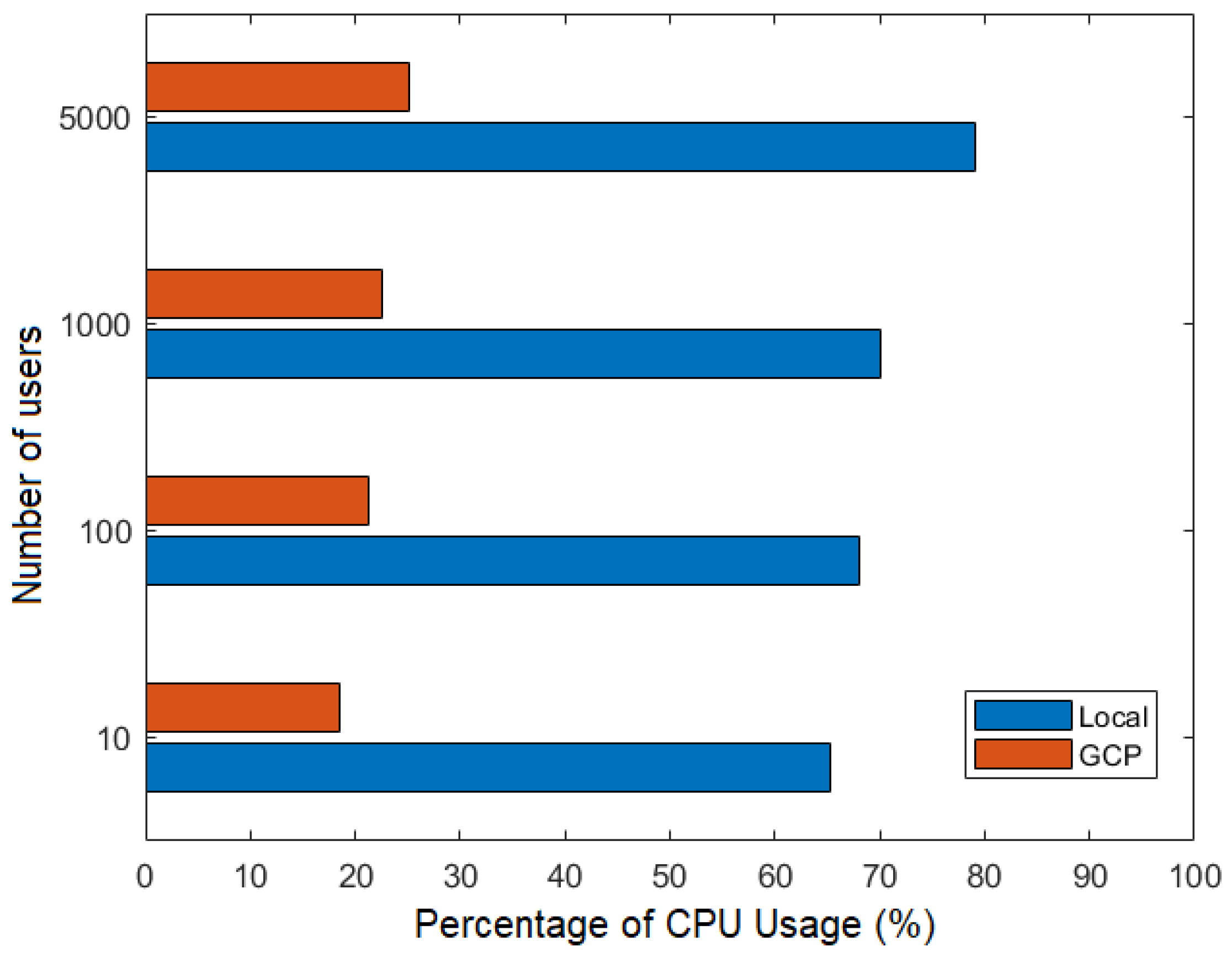

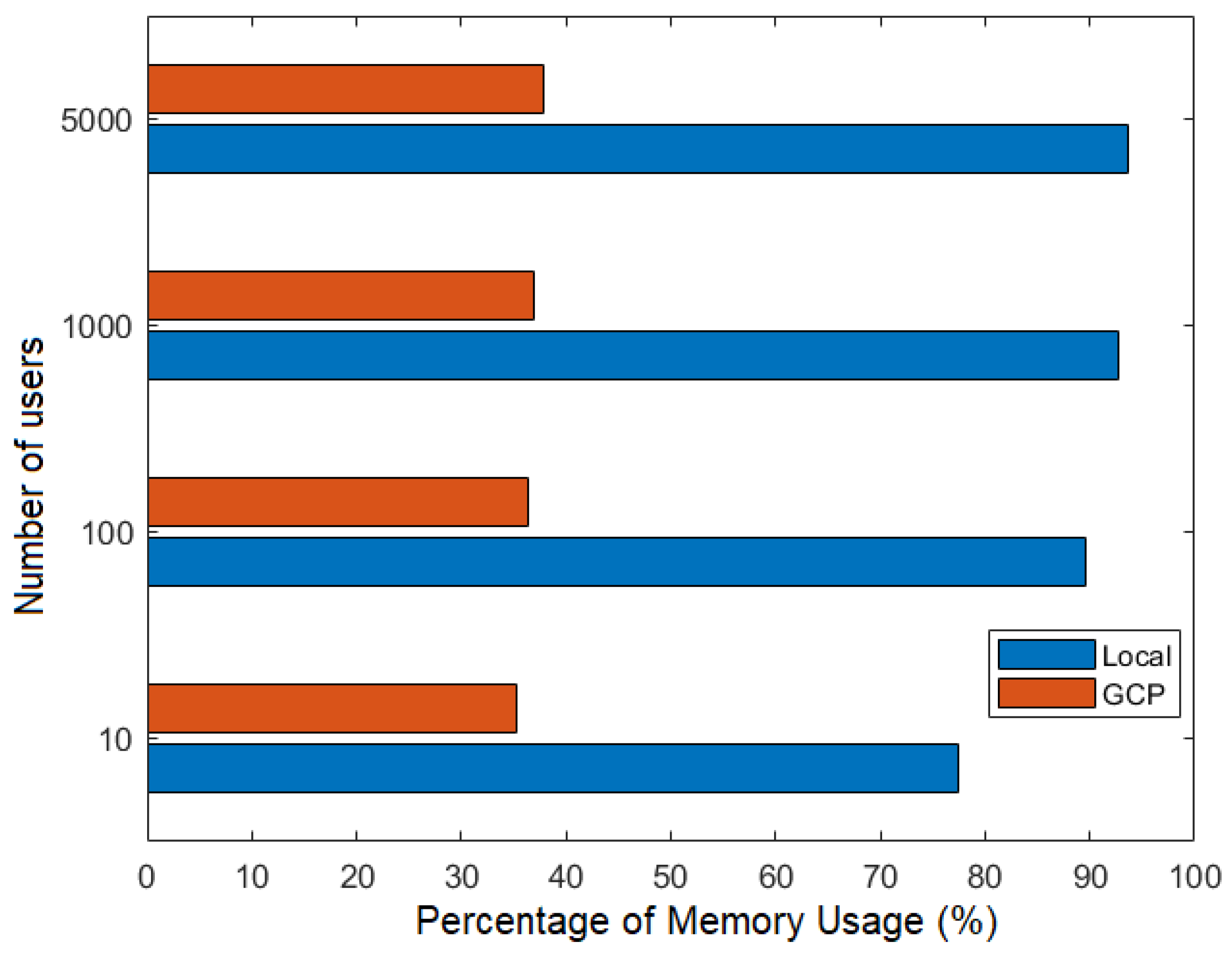

6.7. CPU and Memory Utilization Results

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 show the percentage of CPU and memory usage, respectively, based on the number of users during the joint execution of the flows

FillMedicalRecords and

RequestPatientRecords, that is, the use of CPU and memory was evaluated considering the stages of recording a patient’s medical history in a node and then requesting its delivery to another node participating in the Corda network.

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 illustrate the advantages of using the GCP cloud network. In the GCP scenario, each participating node operates on a separate virtual machine within the cloud, whereas, in the local network, all nodes run on the same machine. This leads to resource saturation, resulting in higher CPU and memory consumption on the local network.

7. Conclusion and Future Works

7.1. Conclusion

In this work, we successfully structured, developed, and tested a Corda network and its corresponding CorDapp as a proof of concept for implementation within the healthcare ecosystem. Our work demonstrates the unique advantages of Corda’s architecture, particularly in enabling only the nodes involved in a transaction to share, store, and track data while registering and retrieving a patient’s medical history. This ensures high privacy and security, which is crucial in medical data management.

Moreover, adopting Corda within the healthcare ecosystem introduces several interesting benefits: it guarantees the immutability of medical data transmission, eliminates the need for reconciliation processes between multiple nodes, and provides real-time visibility during data sharing. These features are critical for ensuring that medical information is handled with the utmost integrity and efficiency.

Through rigorous evaluation of performance metrics, our research confirms that Corda DLT technology is viable and highly effective for medical information transactions. The technology ensures data remains intact, traceable, auditable, confidential, authentic, and interoperable—essential qualities in healthcare.

Finally, the most tangible outcome of this research is the successful construction of the CorDapp, explicitly designed for the secure exchange of health data between medical institutions with patient consent. We validated its functionality in local and cloud environments, underscoring its practical application and scalability in real-world healthcare settings.

7.2. Future Works

In the future, our work can be extended in different aspects:

Specialized Healthcare Functionalities: Expanding the CorDapp to add new functionalities to specific healthcare needs. For example, incorporating tracking of patient medication can significantly enhance the coordination among healthcare providers, ensuring that treatments are administered accurately.

Interoperability through HL7 Standards: Integrating Health Level 7 (HL7) standards into the CorDapp to facilitate interoperability across different healthcare systems. This would enable the seamless exchange of critical medical information, thereby improving communication and collaboration between healthcare institutions.

Predictive Analytics with Machine Learning: Enhancing the CorDapp’s capabilities to support predictive analytics by using machine learning algorithms. This approach would allow for the analysis of network data to identify trends and patterns in patient care, leading to timely interventions and improved healthcare outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Juan Minango and Nathaly Orozco, with a focus on applying blockchain principles within the healthcare ecosystem; methodology, Juan Minango and Marcelo Zambrano, specifically in designing the CorDapp structure; software, Juan Minango, responsible for developing the CorDapp using the Corda framework; validation, Henry Carvajal, Juan Minango, and Marcelo Zambrano, who validated the CorDapp performance in both local and cloud environments; formal analysis, Henry Carvajal and Nathaly Orozco, focusing on metrics like throughput, latency, CPU, and memory usage; investigation, Henry Carvajal and Marcelo Zambrano, who conducted extensive testing on the CorDapp; resources, Francisco Pérez; data curation, Henry Carvajal ; writing—original draft preparation, Juan Minango, Henry Carvajal, and Nathaly Orozco, focusing on blockchain application for healthcare data integrity and confidentiality; writing—review and editing, Francisco Pérez; visualization, Nathaly Orozco; supervision, Francisco Pérez, overseeing the project’s blockchain and healthcare objectives; project administration, Francisco Pérez; funding acquisition, Henry Carvajal and Nathaly Orozco. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received the support of Universidad de Las Américas (UDLA), Ecuador, as part of the research project ERT.NOG.23.13.01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the technical team at the Tecnológico Universitario Rumiñahui for their support in setting up the network infrastructure and testing environments used in this study. We also extend our gratitude to the ETEL Research Group at Universidad de Las Américas (UDLA) for their collaboration in reviewing the methodology and analyzing the results. Finally, we thank the SATRD Lab at the Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV) for providing access to advanced computing resources essential for developing this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System 2009.

- Chen, W.; Xu, Z.; Shi, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J. A Survey of Blockchain Applications in Different Domains. Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Blockchain Technology and Application; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ICBTA 2018; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, T.A.; Khalid, R.; Javaid, N. Solutions, Applications and Future Challenges. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 79626–79651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Ho, N.M.; Loghin, D.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ooi, B.C.; Ta, Q.T.; Zhu, F. Interoperability in Blockchain: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 12750–12769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, P.; Romano, D.; Schmid, G. Beyond Bitcoin - Part I: A critical look at blockchain-based systems. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2015/1164, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Zantalis, F.; Koulouras, G.; Karabetsos, S. Blockchain Technology: A Framework for Endless Applications. IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine 2024, 13, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.N.; Pham, H.A.; Huynh-Tuong, N.; Nguyen, D.H. Leveraging Blockchain to Enhance Digital Transformation in Small and Medium Enterprises: Challenges and a Proposed Framework. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 74961–74978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpin, H.; Piekarska, M. Introduction to Security and Privacy on the Blockchain. 2017 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), 2017, pp. 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Irvin, A.; Kiral, I. Designing for Privacy and Confidentiality on Distributed Ledgers for Enterprise (Industry Track). CoRR 2019, abs/1912.02924. [Google Scholar]

- Opare, E.A.; Kim, K. A Compendium of Practices for Central Bank Digital Currencies for Multinational Financial Infrastructures. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 110810–110847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, A.; Bhatnagar, V. Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT): The Beginning of a Technological Revolution for Blockchain. 2nd International Conference on Data, Engineering and Applications (IDEA), 2020, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Kavitha, C.; Band, S.S.; Mosavi, A.; Hollins, P.; Palanisamy, S. A Recommendation System Based on AI for Storing Block Data in the Electronic Health Repository. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubashar, A.; Asghar, K.; Javed, A.R.; Rizwan, M.; Srivastava, G.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Wang, D.; Shabbir, M. Storage and Proximity Management for Centralized Personal Health Records Using an IPFS-Based Optimization Algorithm. Journal of Circuits, Systems and Computers 2022, 31, 2250010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisimi, T.S.; Chen, R.; Mela, T.; Olshevsky, A.; Paschalidis, I.C.; Shi, W. Federated learning of predictive models from federated Electronic Health Records. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2018, 112, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Bharti, A.K.; Amin, R. Decentralized secure storage of medical records using Blockchain and IPFS: A comparative analysis with future directions. SECURITY AND PRIVACY 2021, 4, e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Decentralized Federated Learning for Electronic Health Records. 2020 54th Annual Conference on Information Sciences and Systems (CISS), 2020, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Bellaj, B.; Ouaddah, A.; Bertin, E.; Crespi, N.; Mezrioui, A. Drawing the Boundaries Between Blockchain and Blockchain-Like Systems: A Comprehensive Survey on Distributed Ledger Technologies. Proceedings of the IEEE 2024, 112, 247–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifat Hossain, M.; Nirob, F.A.; Islam, A.; Rakin, T.M.; Al-Amin, M. A Comprehensive Analysis of Blockchain Technology and Consensus Protocols Across Multilayered Framework. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 63087–63129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselgren, A.; Kralevska, K.; Gligoroski, D.; Pedersen, S.A.; Faxvaag, A. Blockchain in healthcare and health sciences—A scoping review. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2020, 134, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zghaibeh, M.; Farooq, U.; Hasan, N.U.; Baig, I. SHealth: A Blockchain-Based Health System With Smart Contracts Capabilities. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 70030–70043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, G.; Ahad, M.A.; Paiva, S. S2HS- A blockchain based approach for smart healthcare system. Healthcare 2020, 8, 100391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölbl, M.; Kompara, M.; Kamišalić, A.; Nemec Zlatolas, L. A Systematic Review of the Use of Blockchain in Healthcare. Symmetry 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blockchain: Opportunities for Health Care. https://www.colleaga.org/sites/default/files/4-37-hhs_blockchain_challenge_deloitte_consulting_llp.pdf. Accessed: 2023-12-30.

- Chukwu, E.; Garg, L. A Systematic Review of Blockchain in Healthcare: Frameworks, Prototypes, and Implementations. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 21196–21214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdinejad, A.; Srivastava, G.; Parizi, R.M.; Dehghantanha, A.; Choo, K.K.R.; Aledhari, M. Decentralized Authentication of Distributed Patients in Hospital Networks Using Blockchain. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2020, 24, 2146–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, M.; Singh, D.K. Blockchain-based security & privacy for biomedical and healthcare information exchange systems. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQudah, A.A.; Al-Emran, M.; Shaalan, K. Medical data integration using HL7 standards for patient’s early identification. PLOS ONE 2022, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hearn. Corda: A Distributed Ledger. Technical report, R3, 2016.

- Panwar, A.; Bhatnagar, V. Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT): The Beginning of a Technological Revolution for Blockchain. 2nd International Conference on Data, Engineering and Applications (IDEA), 2020, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, J. Mastering Corda: Blockchain for Java Developers; O’Reilly, 2020.

| 1 |

CorDapps are applications that run on the Corda platform. Cordapps are built using the Corda programming languages (Java and Kotlin) and can be used to manage and transfer assets, automate complex business processes, and interact with other Corda nodes. Further, CorDapps are used to implement the logic and business logic of the Corda network and can be customized to meet the specific needs of different service applications and use cases. |

| 2 |

Swagger is a set of tools for developing APIs |

| 3 |

Google Cloud Computing refers to the virtual space through which several tasks that previously required hardware or software can be performed and that now use the Google cloud as the only way to access, store and manage data. |

Figure 1.

Proposed Corda Network Architecture.

Figure 1.

Proposed Corda Network Architecture.

Figure 2.

Create Command.

Figure 2.

Create Command.

Figure 3.

Requisition Command.

Figure 3.

Requisition Command.

Figure 4.

APIs developed in Swagger.

Figure 4.

APIs developed in Swagger.

Figure 5.

Corda nodes executed by the CorDapp developed.

Figure 5.

Corda nodes executed by the CorDapp developed.

Figure 6.

Hospital A node running the FillMedicalRecords flow.

Figure 6.

Hospital A node running the FillMedicalRecords flow.

Figure 7.

Hospital A node performing a query in its database.

Figure 7.

Hospital A node performing a query in its database.

Figure 8.

Hospital C node running the RequestPatientRecords flow.

Figure 8.

Hospital C node running the RequestPatientRecords flow.

Figure 9.

Hospital A node performing a query in its database.

Figure 9.

Hospital A node performing a query in its database.

Figure 10.

Hospital C node performing a query in its database.

Figure 10.

Hospital C node performing a query in its database.

Figure 11.

Considered requests.

Figure 11.

Considered requests.

Figure 12.

Throughput depending on the number of users for TPS node.

Figure 12.

Throughput depending on the number of users for TPS node.

Figure 13.

Throughput depending on the number of users for the TPS network.

Figure 13.

Throughput depending on the number of users for the TPS network.

Figure 14.

Latency versus number of users for the FillMedicalRecords flow.

Figure 14.

Latency versus number of users for the FillMedicalRecords flow.

Figure 15.

Latency versus number of users for the RequestPatientRecords flow.

Figure 15.

Latency versus number of users for the RequestPatientRecords flow.

Figure 16.

Response time versus number of users for the RequestPatientRecords.

Figure 16.

Response time versus number of users for the RequestPatientRecords.

Figure 17.

Response time versus number of users for the RequestPatientRecords.

Figure 17.

Response time versus number of users for the RequestPatientRecords.

Figure 18.

Number of users versus Percentage of CPU Usage.

Figure 18.

Number of users versus Percentage of CPU Usage.

Figure 19.

Number of users versus Percentage of Memory Usage.

Figure 19.

Number of users versus Percentage of Memory Usage.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Local and Cloud Networks.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Local and Cloud Networks.

| |

Local network |

GPC network |

| OS |

Windows 10 Pro 64-bit |

Ubuntu 20.04.3 LTS |

| Processor |

Intel i7-5600U 2.60GHz |

Intel E-2288G 3.7 GHz |

| Core |

4 CPUs |

4 CPU |

| Memory |

8 GB |

8GB |

| Type |

- |

E2 general purpose |

Table 2.

Average throughput.

Table 2.

Average throughput.

| |

TPS Node |

TPS Network |

| Local network |

26.52 |

15.39 |

| GCP network |

20 |

11.71 |

Table 3.

Average latency.

Table 3.

Average latency.

| |

FillMedicalRecords |

RequestPatientRecords |

| Local network |

2.251 |

2.905 |

| GCP network |

2.498 |

3.253 |

Table 4.

Error rate.

| |

FillMedicalRecords |

RequestPatientRecords |

| Local network |

5.71% |

9.52% |

| GCP network |

5.82% |

10.23% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).