Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Between 1851 and 1940, the exhibitions were strongly influenced by the idea of material progress and technological inventions. The themes were generally based on the passion to build the future and the importance of national identity, for example: “Agriculture, Art and Industry”, “A Century of Progress”, “Art and Technology in Modern Life”, etc.

- Between 1958 and 2000, they were characterized by the need to put technological innovation to the service of the prosperity of humanity. The interest changes from a unitary, monolithic identity to relationships, emphasizing the interconnection of people, technology, research, and nature. The change in perspective is also reflected in the new themes addressed, namely: “Towards a more humane world”, “Man and his world”, “Progress and harmony for humanity”, “The age of discoveries”, and “Humanity, nature and technology”.

- the environmental conditions of the insertion of the complex and the access infrastructures, reduction of contamination risks, conservation, the establishment of green spaces, and the quality of urban development.

- the reuse of the complex and the infrastructure after the end of the exhibition.

2. Materials and Methods

- THE IBEROAMERICAN EXHIBITION (130 ha): located in the south of the historic area, it took place in 1929. The Great Iberoamerican Exhibition allowed the sudden development of the city towards the South; the exhibition pavilions are currently part of the buildings that serve the city – they are either the headquarters of the embassies of the countries once represented or various centers belonging to the faculties – libraries, exhibition halls, etc.

- EXPO'92 (250 ha): in the North, North-West of the historic area the Great Universal Exhibition of Seville - EXPO'92 took place in 1992, greatly impacting the city.

2.1. Seville and its Urban Planning

2.2. The Iberoamerican Exposition

- Spanish Pavilions and Exhibits:

- United States of America Pavilions:

- Latin American Pavilions:

2.3. The 1992 Exposition

3. Results

3.1. Post-Expo Urban Planning

- Seville Tecnopolis - Cartuja'93 Scientific and Technological Park which reuses much of the infrastructure of Expo'92 (currently, the "Puerta Triana" project - the first office skyscraper in Seville is being developed in this area);

- Monumental Ensemble "Santa Maria de las Cuevas" ;

- Cultural Area;

- Entertainment, Relaxation and Culture Area;

- Entertainment and Relaxation Area (theme park "Isla Magica");

- Hotel;

- Sports Facilities;

- Alamillo Metropolitan Park;

- University Park;

- Spanish Radio Television.

- American Garden – recovery of plant species

- Reuse of the Pavilion of the Future as a science center-museum

- ISLA de TERCIA Ecological Reserve

- Bike paths - proposal

- Alamillo Park – expansion

- Monastery Orchard – recovery

- Aquatic Ecology Center

- San Jeronimo Park

- Nursery – project

- Riverbank forest-park-promenade – proposal

- Meander bank forest-park

- San Jeronimo Meander

3.2. Botanical Garden and Multifunctional Building

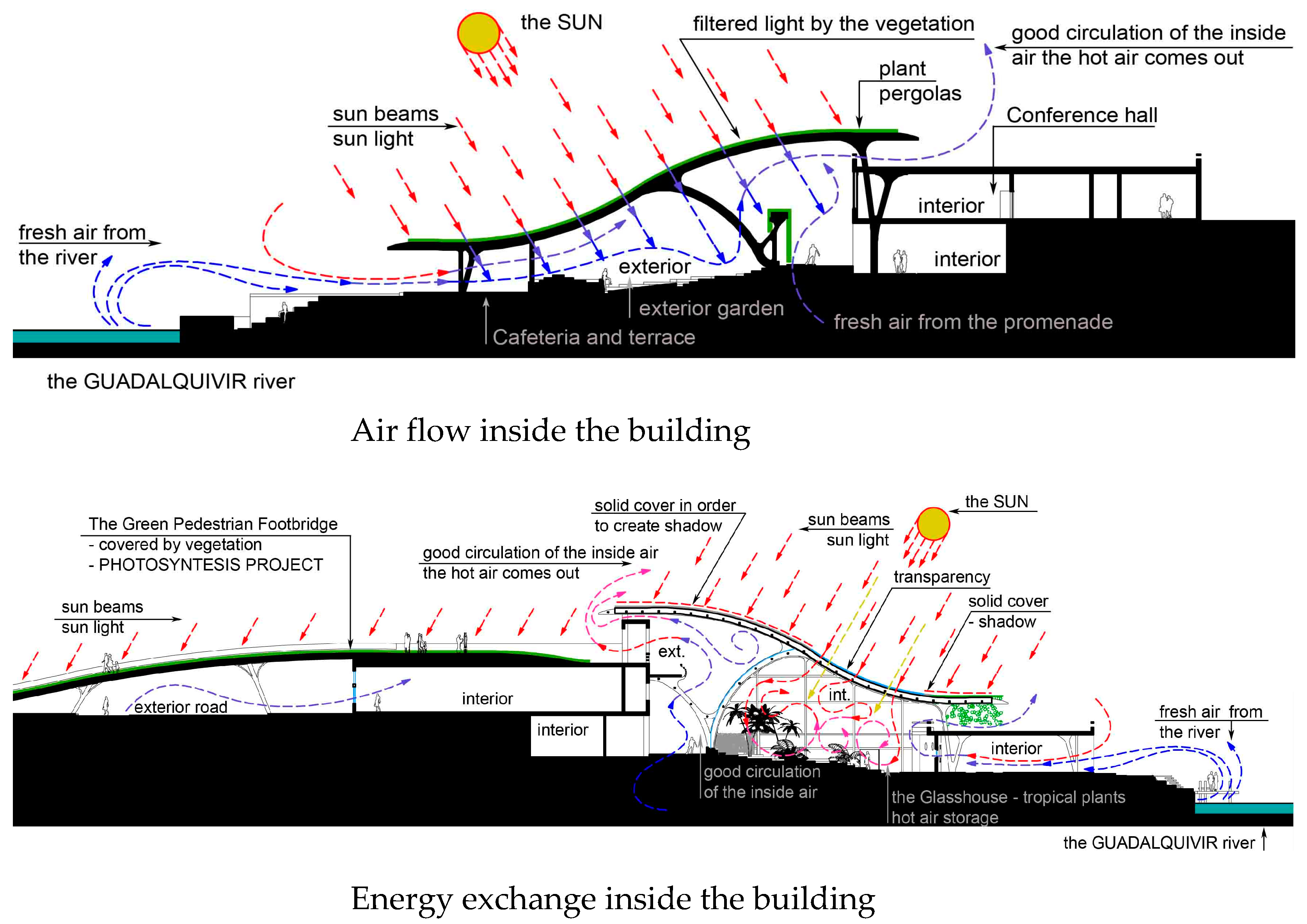

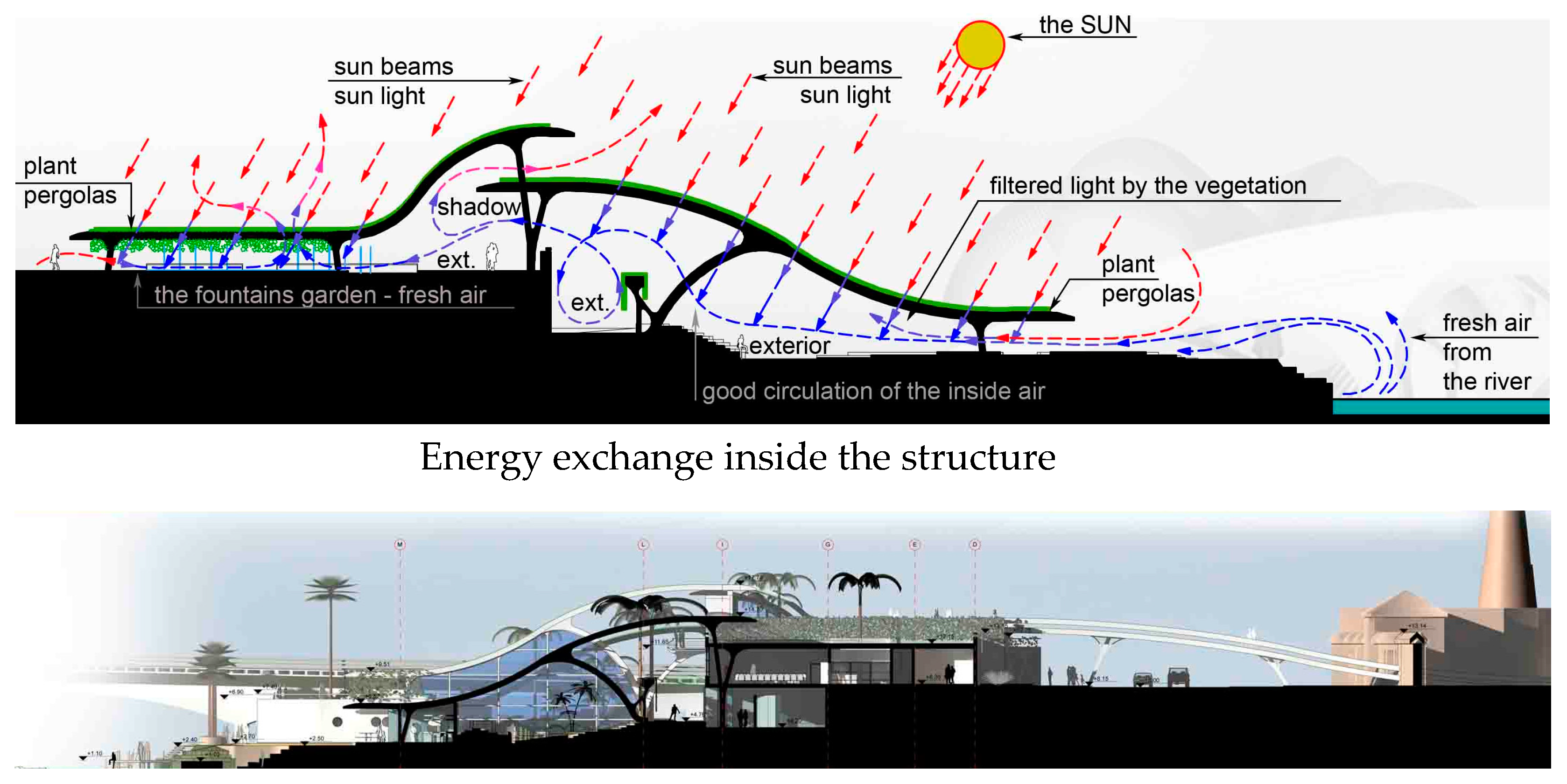

- The outdoor promenade – suitable for outdoor walks, thanks to the pleasant light filtered by the vegetal pergolas.

- The outdoor garden and parks: such as the American Garden with numerous cacti or the aquatic plant garden – are treated differently, with fountains, sprayed water, and filtered light.

- The indoor Botanical Garden – a glass greenhouse for plants that need high, constant temperatures.

- Simulating an Amazon rainforest – a space where it rains very often, which does not need direct light, protected by tensioned translucent canvases, specially designed for reliable use.

- Interior spaces - such as classrooms, exhibition spaces, cafes, conference rooms, shops - positioned near spaces with good air circulation, refreshing the indoor atmosphere.

4. Discussion

- Naturalia XXI which proposes opening the riverbank to the public, with pedestrian and bicycle paths was a very important first step, namely - creating the city-Island Cartuja connection. (existing proposal)

- Step 2 - the revitalization project and creating a coherent Waterfront - by implementing cultural functions (Museum of Contemporary Arts, Naval Museum, Science Museum) along the river, recreational functions - revitalizing the Isla Magica amusement park, relaxation functions - revitalizing the parks along the Guadalquivir riverbank (fictitious proposal)

- Step 3 - new projects for the Island Cartuja, such as the new Pelli tower - an office building with commercial spaces, terraces, and green areas at the base. (existing proposal)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fraga, M. , Javier, F., Exposiciones internacionales y urbanismo. El proyecto Expo Zaragoza 2008, Spain, 2006 - in Spanish.

- Pervolarakis, Z.; Agapakis, A.; Xhako, A.; Zidianakis, E.; Katzourakis, A.; Evdaimon, T.; Sifakis, M.; Partarakis, N.; Zabulis, X.; Stephanidis, C. A Method and Platform for the Preservation of Temporary Exhibitions. Heritage 2022, 5, 2833–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trillo, M. , La Ciudad de las Exposiciones Universales, Monografias de Urbanismo, Gerencia Municipal de Urbanismo, Seville, 1985 in Spanish.

- Ochoa, R. The “Expo” and the Post-“Expo”: The Role of Public Art in Urban Regeneration Processes in the Late 20th Century. Sustainability 2022, 14, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minner, J.S., Zhou, G., Toy, B., Global city patterns in the wake of World Expos: A typology and framework for equitable urban development post mega‐event, Land Use Policy, Volume 119, 2022, 0264‐8377. [CrossRef]

- Bureau International des Expositions, https://www.bie-paris.org/site/en/, (accessed on 02 12 2024).

- Hapenciuc, A.D. , et al The Poetics of Access Apparatuses in Contemporary Lyric Exhibition Spaces, 2020 IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 960 042010, DOI 10.1088/1757-899X/960/4/042010.

- Salas, N. , Sevilla en tiempos de la exposicion Iberoamericana,1905-1930, la Ciudad del siglo XX, RD Editores, Sevilla, 2004 – in Spanish.

- Escolano, V.P. , Sevilla '92: reflexiones arquitectonicas sobre un año extraordinario, Vol. 24, Delegación de Almería del Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Andalucía Oriental, 1993 – in Spanish.

- Zhou, Y.; Sanz-Hernández, A.; Hernández-Muñoz, S.M. Artistic Interventions in Urban Renewal: Exploring the Social Impact and Contribution of Public Art to Sustainable Urban Development Goals. Societies 2024, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, E. , Desde Rumanía para restaurar la Cartuja, Diario de Sevilla, 2008, pg.

- Martin, A., Un regalo de Rumania para la Cartuja, 2008, Expo92.es, http://www.expo92.es/mensaje/1051‐ regalo_rumania_cartuja.

- Vela, J.L. , La arquitectura del 92- Edificacion de caracter permanente en la isla de la Cartuja, Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Sevilla, Sevilla 1990, in Spanish.

- Salagean-Mohora, I.; Anghel, A.A.; Frigura-Iliasa, F.M. Photogrammetry as a Digital Tool for Joining Heritage Documentation in Architectural Education and Professional Practice. Buildings 2023, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercleux, A.-L.; Harfst, J.; Ilovan, O.-R. Cultural Values, Heritage and Memories as Assets for Building Urban Territorial Identities. Societies 2022, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, F.G. , Sautu, C.Z., Paisaje y urbanismo de la expo 92, RD Editores, Sevilla, 2002 – in Spanish.

- Anghel, A.A.; Giurea, D.; Mohora, I.; Hapenciuc, A.-D.; Milincu, O.C.; Frigura-Iliasa, F.M. Green Interactive Installations as Conceptual Experiments towards a New Meaning of Smart Design. Buildings 2022, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cartuja Science and Technology Park, https://www.pctcartuja.es/en, (accessed on 02 12 2024).

- Fundación Naturalia XXI, https://www.upo.es/ceicambio/?p=113&lang=es, (accessed on 02 12 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).