1. Introduction

The agroforestry system is an excellent three-dimensional agriculture, which can make full use of resources and space, has high ecological and economic benefits, can effectively alleviate the contradiction between agriculture and forestry ‘competition for land’, and increase farmers' income, and has been widely applied in the Loess Plateau of China [

1,

2]. China is the world's largest apple producer [

3], and the Loess Plateau is one of China's two main apple-producing regions, which faces a number of water resource challenges common to other semi-arid areas, including sloppy farm management, seasonal drought, and inefficient water use [

4].

Polygonatum sibiricum is a crop with a high potential for development. It is suitable for extensive planting in subtropical, temperate, and cold temperate zones, especially under-forest planting. It does not occupy the fertile agricultural land, does not compete with forest land, can solve the problem of obvious hunger and hidden hunger, but there is a problem of under-forest cultivation of high quality but not high yield [

5,

6]. Apple–crop intercropping is one of the typical agroforestry practices in the Loess Plateau region, which has the advantages of preventing soil erosion, restoring ecological balance and increasing farmers' incomes [

2]. Apple trees provide a plenty range of shade [

7], and cooling and humid microclimate [

8].

Polygonatum sibiricum is a shade-loving, cold-tolerant, and drought-tolerant plant, native to the undergrowth, thickets and shady areas of mountain slopes, suitable for planting under forests [

6]. Therefore, the development of apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping may provide complementary benefits. However, the intercropping of apple and

Polygonatum sibiricum has not yet been reported. The findings of this study can contribute to the expansion of the planting pattern of the agroforestry system on the Loess Plateau.

The key to increasing the productivity of agroforestry systems is to maximize the use of resources and minimize interspecific competition [

9]. Competition between trees and crops for soil water and nutrients in agroforestry systems is often more intense than is competition for light [

10,

11]. Soil moisture is the main object of competition between trees and crops in agroforestry systems in arid and semi-arid regions [

12]. According to theoretical ecology, competition occurs under conditions of an interspecific insufficient supply of resources and niche overlap [

13,

14]. Therefore, measures need to be taken to mitigate interspecific water competition in apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping systems and to improve the productivity of intercropping systems.

The most prevalent methods employed to alleviate interspecific water competition in apple0crop intercropping systems are agronomic measures and supplementary irrigation during critical growth periods [

15]. Straw mulching is widely used as a water conservation technique in agricultural systems and has the potential to improve crop water use efficiency and yield [

15,

16]. Film mulching is one of the key measures to solve the long-term water shortage of crops in arid and semi-arid areas of China, with the role of raising temperature and protecting business, strengthening seedlings and increasing production [

17]. Root barriers are a means of managing tree root systems to reduce or isolate tree and crop root systems from competition for soil resources, improve crop growth and increase crop yields [

11,

18]. Increasing the distance between crops and trees reduces the overlap of their ecological niches and reduces competition [

11,

19]. Supplemental irrigation, especially during critical stages of crop growth, is an effective way to improve water productivity for crop yield [

15]. The effects of different agronomic practices and supplemental irrigation on the growth and yield of the components of the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system on the arid and semi-arid Loess Plateau are currently unknown. Further research is needed in order to determine the optimal agronomic practices and supplemental irrigation strategies for the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system.

In this study, we used different agronomic measures (straw mulching, film mulching, root barriers, increased spacing) and supplemental irrigation measures to investigate the effects of different agronomic measures and supplemental irrigation strategies on the growth and yield of each component of the apple–Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system, and to propose optimal techniques for water regulation and management of the apple–Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system. The results of this study can provide theoretical basis and technical support for the agronomic measures and supplementary irrigation management of the apple–Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system in the Loess Plateau.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

The field experiments were conducted at the Modern Apple Planting Technology Innovation Centre (35°25′55″~35°51′11″N, 107°27′42″~107°52′48″ E, altitude: 1421m) in Qingyang City, Gansu Province, China. The experimental site is located in the hinterland of the Loess Plateau of Longdong, for the Loess Plateau gully area, temperate continental semi-arid climate, the average annual precipitation of 541.7mm, precipitation is mainly concentrated in June–August, the average annual temperature of 10 ℃, the annual frost-free period of 170d, the total number of hours of sunshine hours per year 2,400~2,600h, the soil type was dark loessal soil, the soil bulk density and field capacity are 1.30 g/cm3 and 22.01%, respectively, for the effective rooting depth (1 m). The pH of the soil in the apple orchard is 8.1. The main economic tree species in the area are apple (Malus pumila M.), walnut ((Juglans regia L.), apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.), etc. The main intercrops are peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.), soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.), maize (Zea mays L.), etc.

2.2. Experimental Design

The experiment was conducted in 2022 and 2023. The apple trees were planted at a spacing of 4.0 × 4.0 m in an east-west direction in 2018. Agronomic management including weeding, insecticide spraying, pruning flowers, and fruit thinning were conducted according to the local standardized orchard. Polygonatum sibiricum seedlings were taken from the demonstration base of Chinese herbal medicine planting at the Gansu Key laboratory of Conservation and Utilization of Biological Resources and Ecological Restoration in Longdong, and fresh Polygonatum sibiricum tubers were selected and planted at a spacing of 0.3×0.4m, and were situated at 0.4 m from the apple tree row, and planted in the first half of April in 2022 and 2023, respectively. Each plot measured 12.0 x 12.0 m and contained 16 apple trees and intercropped Polygonatum sibiricum. According to the local fertilization practice and the empirical fertilization rate, the N/P/K compound fertilizer was evenly spread before the soil was turned over and the application rate was N 416.4 kg/hm2 + P2O5 170.4 kg/hm2 + K2O 170.4 kg/hm2. Each plot was subjected to the same agricultural management practices.

The apple–Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system was set up with straw mulching (SM), film mulching (FM), root barrier treatment (RB), increased spacing treatment (IS) and control treatment (CK) at Polygonatum sibiricum planting in 2022. For the SM treatment, the wheat straw was cut into segments of a maximum length of 5.0 cm to cover the entire intercrop area and under the tree discs at a thickness of 5.0 cm. For the FM treatment, 0.005 mm polythene plastic film was used to cover the rows of Polygonatum sibiricum before sowing. For the RB treatment, a trench 0.3m wide, 1.0m deep and 4.0m long was dug at a distance of 0.7m from the rows of apple trees one year before the experiment, and 0.12mm thick plastic film was laid along the wall of the trench and the soil was filled back in as it was afterwards. For the IS treatment, Polygonatum sibiricum was planted at a distance of 1.2 m from the apple tree rows. In the CK treatment, no agronomic management practices were applied in the apple–Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system. There were three replications for each treatment. A total of 15 experimental plots were created. All plots were subjected to the same agricultural management practices, including fertilization, weeding, insecticide spraying, flower pruning and fruit thinning.

Three supplementary irrigation levels, representing 55% (M1), 70% (M2) and 85% (M3) of the field's water holding capacity, were implemented at three key stages of

Polygonatum sibiricum growth: Seedling–flowering stage (14 May), flowering–fruiting stage (10 July) and fruiting–mature stage (17 September) in 2023. The irrigation scheme wetted depth was 1.0m. Nine treatments (T1–T9) were set at different levels of supplemental irrigation at different reproductive stages of

Polygonatum sibiricum. Additionally, conventional rainfed apple trees were used as the control (CK), making a total of 10 treatments (

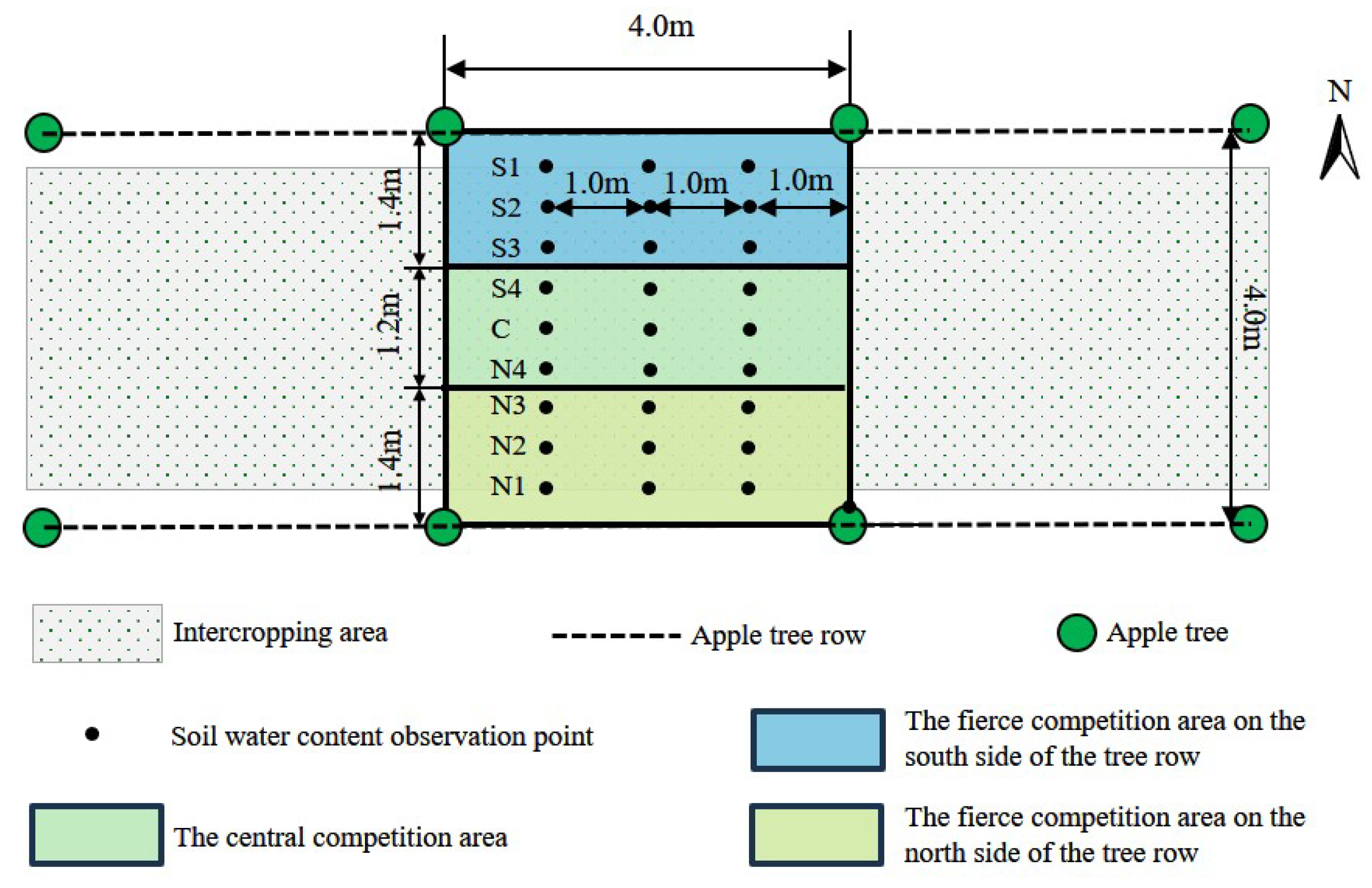

Table 1). Each treatment was replicated three times. A total of 30 experimental plots were established. All plots were mulched with films, and the management measures of each plot was the same. To avoid potential interactions between the plots, they were positioned at a distance of 4.0 m apart, in accordance with a completely randomized block group design. Based on the results of our previous studies on apple–crop intercropping systems, interspecific competition was fiercer in the area 1.3 m from the rows of apple trees in intercropping systems with apple trees 5 years old [

19]. Therefore, in this study, a ridge was established 1.4 m from the north and south sides of the apple tree rows, and the plots of the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system were divided into three zones for supplemental irrigation (

Figure 1), which were the fierce competition area on the south side of the tree row (1.4 × 4.0 m), the central competition area (1.2 × 4.0 m), and the fierce competition area on the north side of the tree row(1.4 × 4.0 m), respectively. All plots were irrigated by border irrigation, with the irrigation water coming from rainfall collected in the apple orchard cellar, and tap water was used for irrigation when the cellar water was insufficient, and the amount of irrigation water was controlled by a water meter (Dipuer, SDB–002, Shandong Kaili Meter Technology Co., Ltd., Linyi, China).

2.3. Rainfall Measurements

A rain gauge (RG3–M, Onset Computer Corporation, Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA) was installed in an open area approximately 100 m from the apple orchards to measure measuring rainfall. A single rainfall event greater than 5 mm was considered as the effective rainfall.

2.4. Soil Water Measurements

Three soil water monitoring sample lines were laid perpendicular to the direction of the apple tree rows (

Figure 1), with an interval of 1.0 m between the sample lines. Additionally, soil water monitoring points were laid along the lines at intervals of 0.4 m from the apple tree rows, resulting in a total of 27 soil water monitoring points in each plot. Soil samples were taken in layers using an auger at a depth of 1.0m, 0.2m per layer, and the oven-drying method was used to determine the soil mass water content. The Soil water content was measured at each fertility stage of

Polygonatum sibiricum in 2022. In the year 2023, the soil water content was measured on three occasions: prior to the planting of

Polygonatum sibiricum, prior to the implementation of supplementary irrigation, and following the completion of the harvest.

2.5. Apple Growth and Yield Measurements

The relative chlorophyll content and new branch growth of apple trees were determined at the fruiting–mature stage of Polygonatum sibiricum. Four apple trees situated within the core area of the apple–Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system were selected for analysis. From each tree, eight newborn branches were selected from different directions in the middle of the canopy. Subsequently, the growth of the new branches was quantified through the use of a measuring tape, with each branch undergoing three measurements. The resulting mean value was then calculated. Additionally, three mature leaves exhibiting health were randomly selected from each branch for the determination of relative chlorophyll content using the SPAD–502PLUS (Konica Minolta Optics, Japan). The front, middle, and back regions of the leaves were each measured once, and the resulting average value was recorded. The yield of apple trees was not considered in this study due to the absence of fruit production or a lower fruit production in the fourth and fifth years.

2.6. Polygonatum sibiricum Growth and Yield Measurements

The plant height and aboveground biomass of Polygonatum sibiricum were determined at the fruiting–mature stage. In the intercropping system, 20 Polygonatum sibiricum plants were randomly selected and a measuring tape was used to determine the height of the plants. As the Polygonatum sibiricum stalks are overhanging, soft and easily breakable, the height of the plant was initially gauged with a string, and then the comparative length of the string, which is the height of the plant, was measured with a ruler. Once the Polygonatum sibiricum had reached maturity, the entire intercropping system area (4.0 × 4.0 m) was harvested. The plants were removed from the plots, the aboveground parts were cut and placed in archival bags, and then the underground tubers were removed from the root system, cleaned and air-dried before being placed in archival bags. The aboveground biomass and yield of each plant were then measured using the oven-drying method.

2.7. Data Analysis

2.7.1. Irrigation Amount

The quantity of irrigation was ascertained through the utilization of the upper and lower limit method, whereby irrigation was initiated when the soil water content fell below the specified lower limit. The quantity of irrigation was calculated using the following formula:

Where

A is the amount of irrigation (mm);

h is the planned wetting depth (cm), which was set at 100 cm;

r is the bulk density of the soil (g/cm

3);

W is the lower limit of irrigation (%), which is 55%, 70% and 85% of the field's water holding capacity; and

W0 is the mass water content of the soil (%) measured before irrigation.

2.7.2. Water Consumption

The water consumption (ET) during the growth of intercropped

Polygonatum sibiricum was estimated using the water balance approach, as follows:

Where

ET is the water consumption (mm) of the growth stage of the intercropped

Polygonatum sibiricum,

I is the irrigation amount (mm) during the stage,

P is the amount of effective rainfall (mm) during the stage,

U is the amount of groundwater recharge (mm), the groundwater burial depth was approximately 30 m, and thus, the recharge from the surface layer of groundwater was also assumed to be 0.

R is the amount of surface runoff (mm). As the test site was flat, the visible surface runoff was 0.

F is the amount of deep seepage (mm). As the soil mass water content at 80–100 cm after each irrigation round or rainfall was less than the field capacity, so the deep seepage was assumed to be 0.

ΔW is the difference in the consumption of water stored in the 0–100 cm soil at the beginning and at the end of the stage.

2.7.3. Water Use Efficiency (WUE)

The water use efficiency (WUE) of the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system was calculated as the ratio of

Polygonatum sibiricum yield to the total volume of water consumed over the entire intercropped area (4.0 × 4.0 m). The WUE was calculated by the formula:

where

WUE is the water use efficiency (kg·hm

-2·mm

-1),

Y is the yield of

Polygonatum sibiricum (kg·hm

-2), and

ET is the water consumption (mm).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The graphs were generated using Origin 2021 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA). Experimental data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the IBM SPSS statistical software package (version 27.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Multiple comparisons were conducted using the least significant difference (LSD) method at a significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Responses of Growth and Yield of the Intercropping System to Agronomical Measures

3.1.1. Soil Water Content

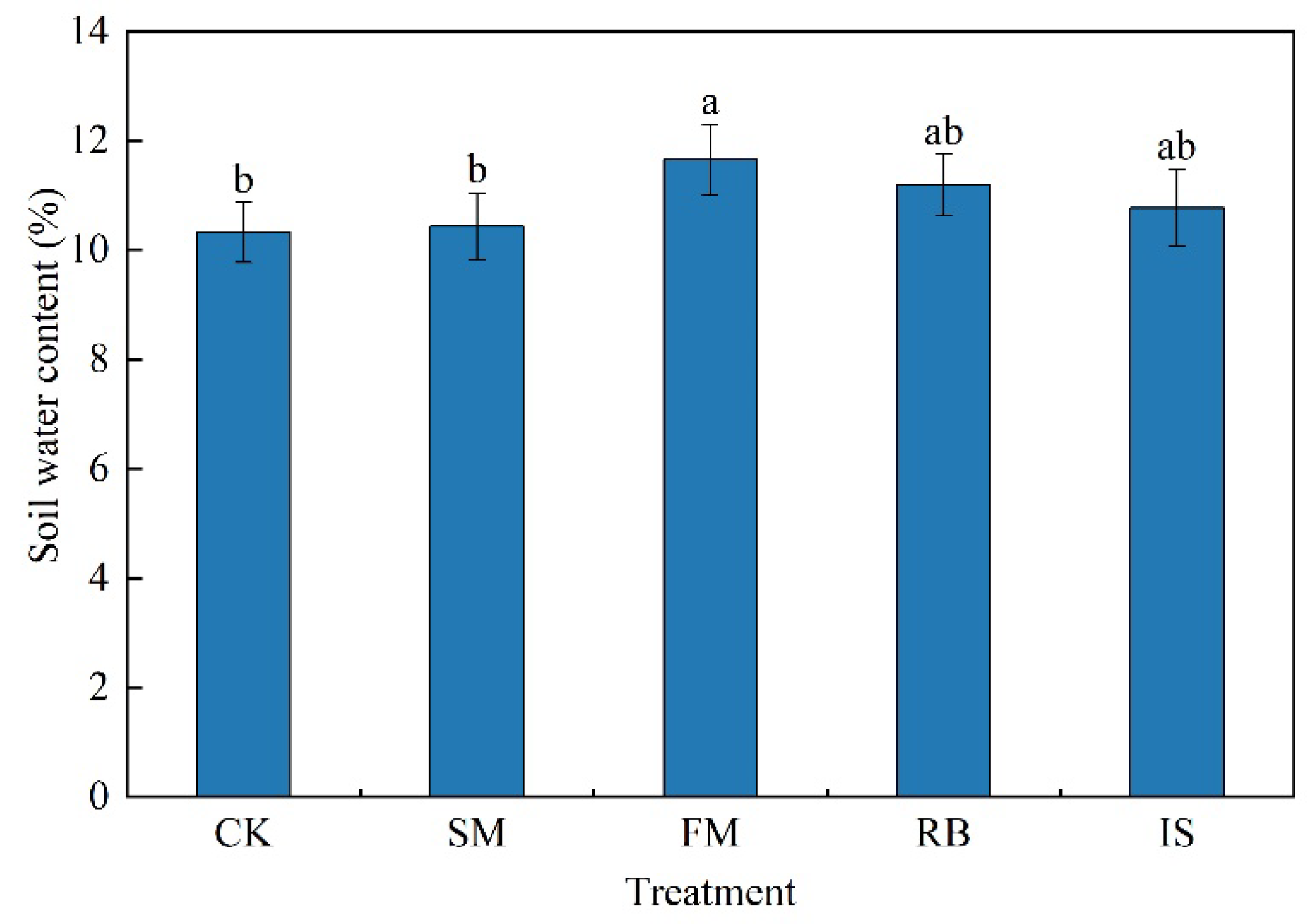

The soil water content of the SM, FM, RB and IS treatments was higher than that of the CK treatment (

Figure 2). The soil water content of the FM treatment was significantly increased (by 1.33%;

p < 0.05) than that of the CK treatment. Furthermore, the soil water content of the SM, RB and IS treatments was not significantly increased (

p > 0.05) than that of the CK treatment with a difference of 0.11%, 0.87% and 0.45%, respectively.

3.1.2. Apple Tree Growth

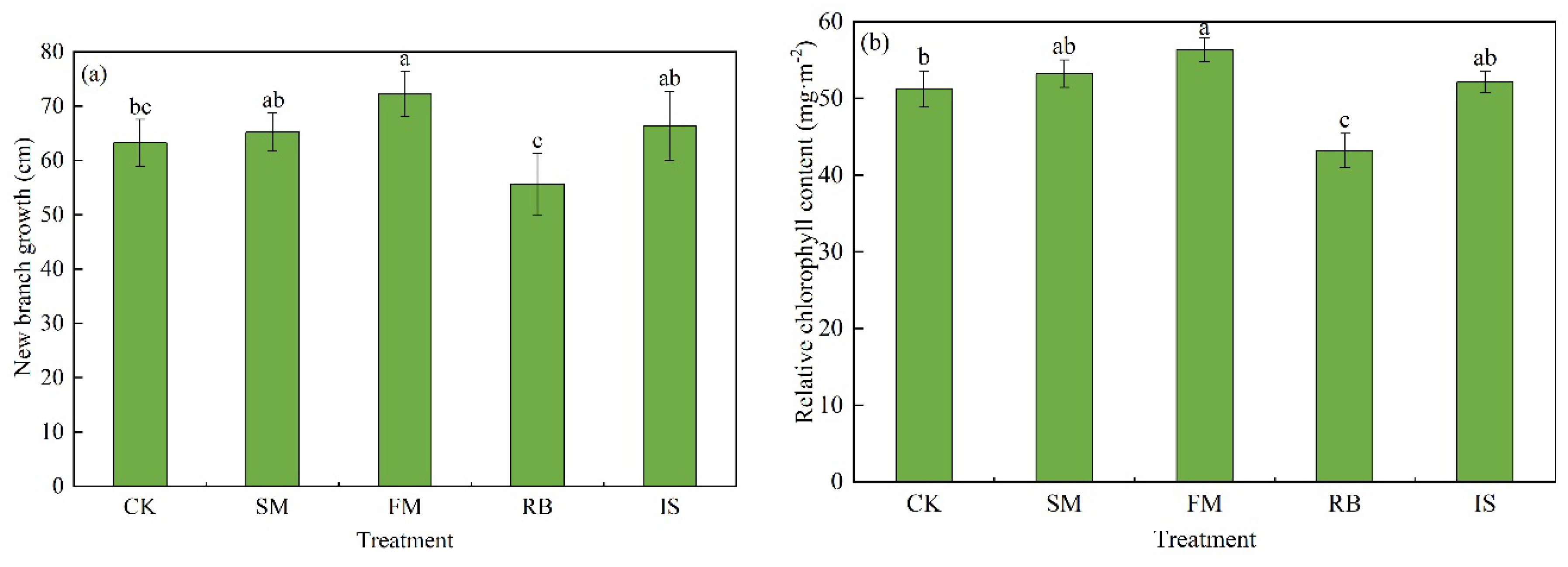

The new branch growth of apple trees in the SM, FM and IS treatments was 3.20%, 14.29% and 4.97% higher than that of the CK treatment, respectively (

Figure 3). However, the new branch growth of apple trees in the RB treatment was 11.98% lower than that of the CK treatment. The relative chlorophyll content of apple trees in the SM, FM and IS treatments was 3.88%, 9.99% and 1.78% higher than that of the CK treatment, respectively (

Figure 3). However, the relative chlorophyll content of apple trees of the RB treatment was significantly lower (by 15.65%;

p < 0.05) than that of the CK treatment. In addition, new branch growth and relative chlorophyll content of apple trees in the FM treatment were significantly increased (p < 0.05) compared to the CK treatment.

3.1.2. The Growth and Yield of Polygonatum sibiricum

The plant height of

Polygonatum sibiricum of the SM, FM, RB and IS treatments was 3.70%, 25.37%, 15.88% and 9.67% higher than that of the CK treatment, respectively (

Figure 4). Moreover, the aboveground biomass of

Polygonatum sibiricum of the SM, FM, RB and IS treatments was 5.12%, 31.71%, 13.39% and 8.27% higher than that of the CK treatment, respectively (

Figure 4). In addition, the plant height and above-ground biomass of

Polygonatum sibiricum of the FM treatment were significantly increased compared to the CK treatment (

p < 0.05), while the others showed an insignificant change (

p > 0.05).

The yield of

Polygonatum sibiricum for each treatment is shown in

Table 2. Compared with the yield of

Polygonatum sibiricum of the CK treatment, the FM treatment showed a significant increase of 28.71% (

p < 0.05), while the SM treatment showed an insignificant increase of 4.54% (

p > 0.05). However, compared to the

Polygonatum sibiricum yield of the CK treatment, the RB treatment showed an insignificant decrease of 9.96% (

p > 0.05), while the IS treatment showed a significant increase of 37.89% (

p < 0.05).

3.2. Responses of Growth and Yield of the Intercropping System to Supplemental Irrigation

3.2.1. Effective Rainfall

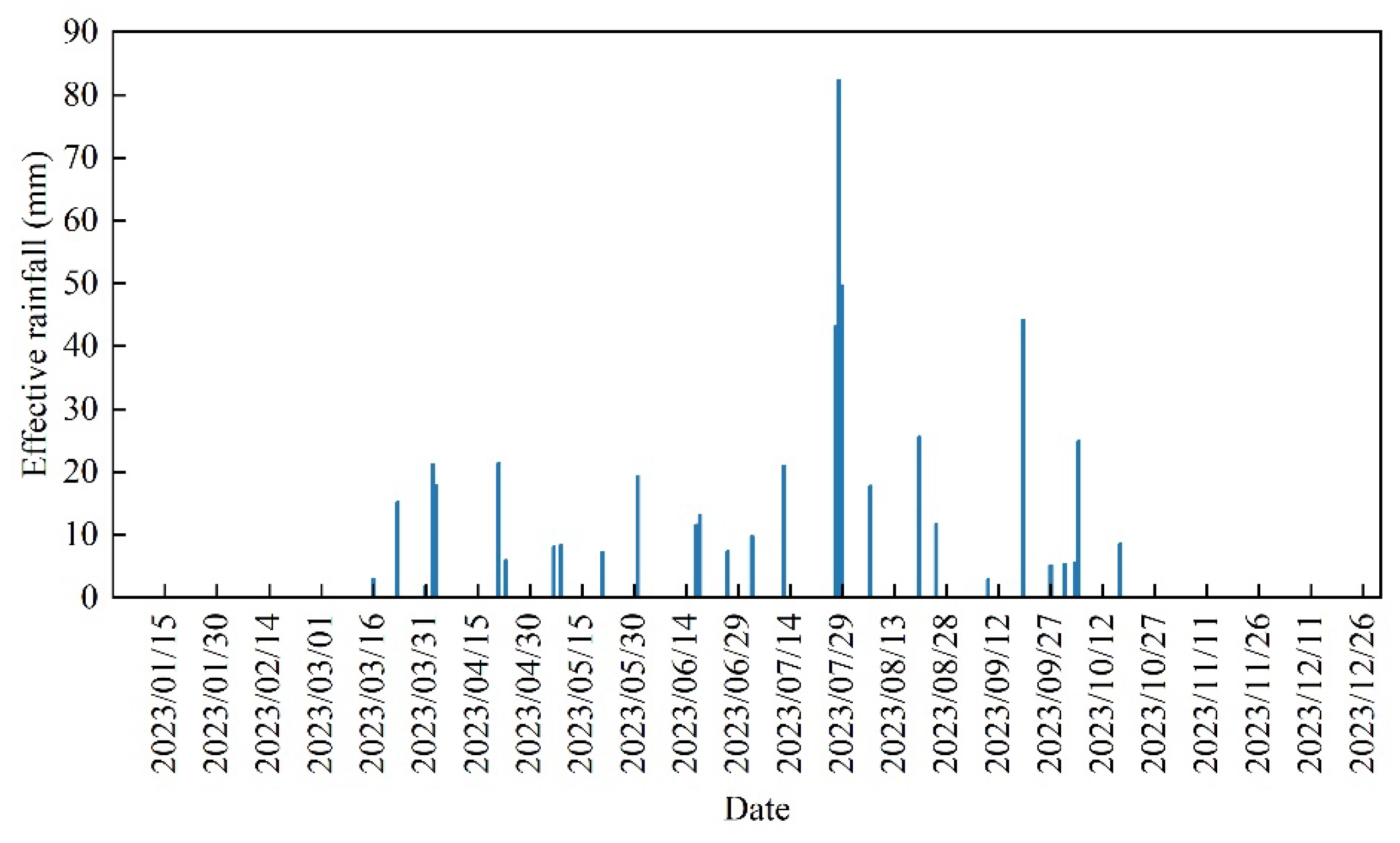

The effective rainfall amount was 520.36mm in 2023 (

Figure 5). The effective rainfall amount during the growing season (April to October) of

Polygonatum sibiricum was 500.36mm, with the most of the effective rainfall occurring in July, which accounted for 39.62% of the total annual effective rainfall amount. Furthermore, the effective rainfall amount of August and September accounted for 10.60% and 10.07% of the total annual effective rainfall amount, respectively.

3.2.2. Apple Tree Growth

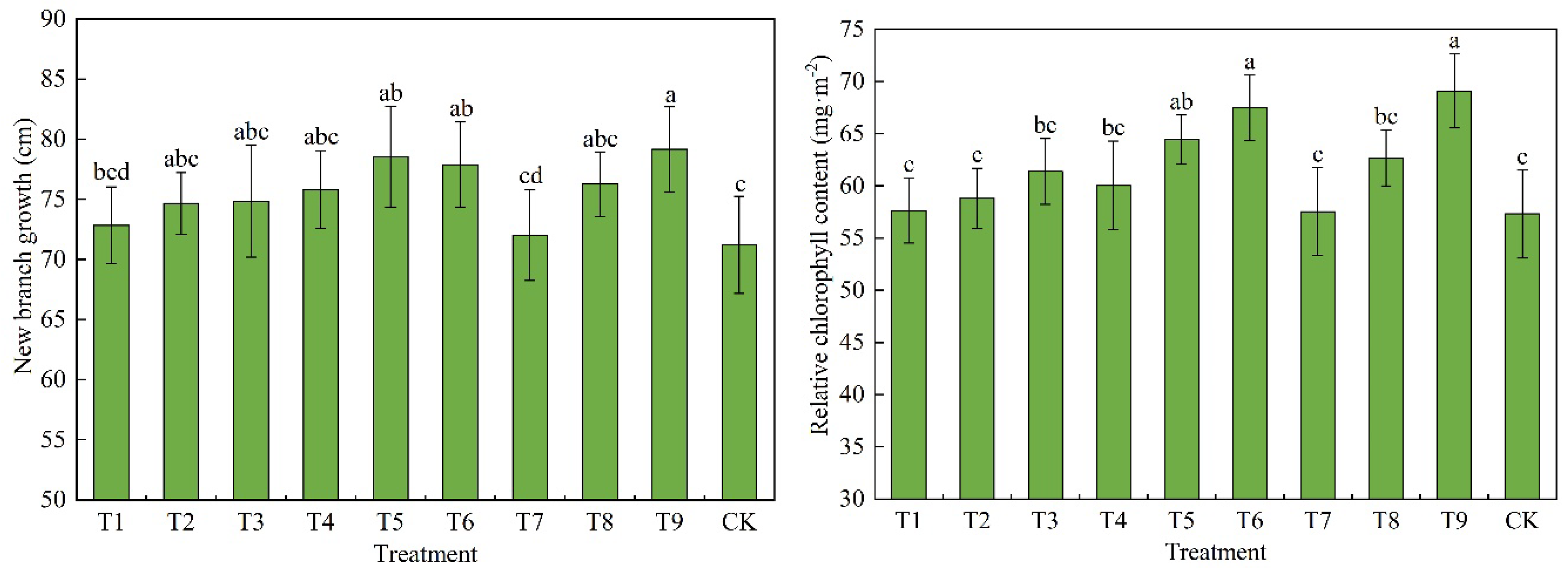

The new branch growth of the apple trees was T9, T5, T6, T8, T4, T3, T2, T1, T7, CK from high to low in the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system (

Figure 6). The new branch growth of apple trees in each supplemental irrigation treatment was longer than that of the CK treatment. In addition, compared to the new branch growth of apple trees in the CK treatment, that of the T9, T5, and T6 treatments was significantly increased (

p < 0.05) by 11.15%, 10.28% and 9.37%, respectively.

The relative chlorophyll content of the apple trees was T9, T6, T5, T8, T3, T4, T2, T1, T7 and CK from high to low in the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system (

Figure 6). The relative chlorophyll content of apple trees in all supplemental irrigation treatments except T7 was higher than in the CK treatment (

Figure 6). Furthermore, compared to the relative chlorophyll content of apple trees in the CK treatment, the T9, T6 and T5 treatments showed a significant increase (

p < 0.05) of 20.53%, 17.76% and 12.46%, respectively. In addition, the relative chlorophyll content of apple trees in the T7 treatment was the same as that of CK.

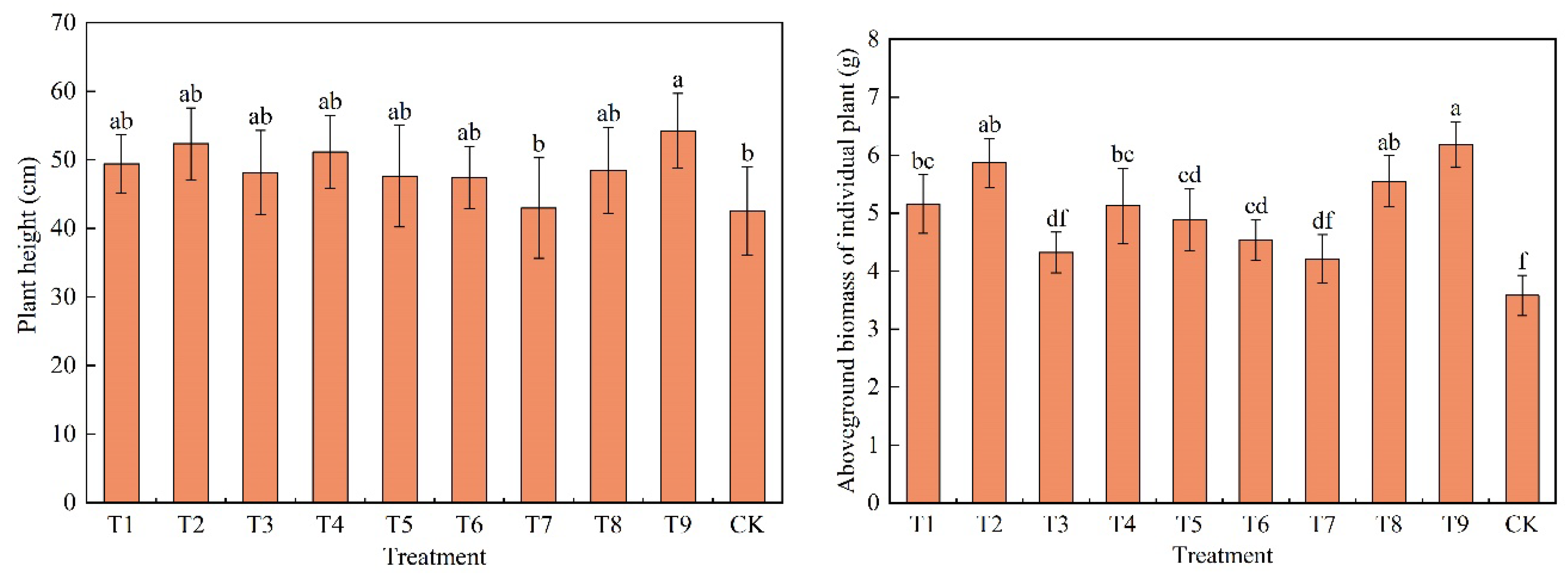

3.2.3. The Growth and Yield of Polygonatum sibiricum

The plant height and aboveground biomass of

Polygonatum sibiricum of each supplemental irrigation treatment were higher than those of the CK treatment (

Figure 7). The plant height of

Polygonatum sibiricum was T9, T2, T4, T1, T8, T3, T5, T6, T7 and CK from high to low in the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system. Moreover, the plant height of

Polygonatum sibiricum of T9, T2 and T4 treatments was 27.57%, 23.17% and 20.37% higher than that of the CK treatment, respectively, and the T9 treatment increased significantly (

p < 0.05) compared to the CK treatment.

The aboveground biomass of

Polygonatum sibiricum was T9, T2, T8, T1, T4, T5, T6, T3, T7 and CK from high to low in the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system (

Figure 7). Furthermore, compared to the aboveground biomass of

Polygonatum sibiricum of the CK treatment, the T9, T2, T8, T1, T4, T5, and T6 treatments increased significantly (

p < 0.05) by 72.91%, 63.97%, 55.03%, 44.13%, 43.30%, 36.59% and 26.82%, respectively. In general, compared to the above ground biomass of

Polygonatum sibiricum of the CK treatment, the T9, T2 and T8 treatments showed an increase of more than 50%.

The yield of

Polygonatum sibiricum in the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system was T9, T2, T1, T8, T4, T5, T3, T6, T7 and CK from high to low (

Table 3). In addition, the yield of

Polygonatum sibiricum in the intercropping system was significantly increased (

p < 0.05) in all supplemental irrigation treatments except T7 compared to the CK treatment. In general, compared to the yield of

Polygonatum sibiricum in the intercropping system of the CK treatment, the T9 and T2 treatments showed an increase of more than 50% and the difference between T9 and T2 was not significant (

p > 0.05).

The WUE of

Polygonatum sibiricum in the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system was T2, T8, T1, T4, T5, T9, T7, CK, T3 and T6 from high to low (

Table 3). Furthermore, compared to the WUE of

Polygonatum sibiricum of the CK treatment, the T2, T8, T1, T4 and T5 treatments increased significantly (

p < 0.05) by 25.42%, 17.68%, 14.86%, 14.58% and 10.35%, respectively. However, compared to the WUE of the

Polygonatum sibiricum of the CK treatment, the T3 and T6 treatments showed an insignificant decrease (

p > 0.05) of 1.13% and 4.79%, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Responses of Growth and Yield of the Intercropping System to Agronomical Measures

Soil moisture is the main object of competition between trees and crops in agroforestry systems in arid and semi-arid regions [

12]. According to theoretical ecology, competition occurs under conditions of an interspecific insufficient supply of resources and niche overlap [

13,

14]. Consequently, the alleviation of interspecific soil moisture competition in apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping systems may be achieved through the enhancement of soil moisture status, and a reduction in root ecological niche overlap. In arid and semi-arid areas, soil moisture is a major factor limiting crop growth and development. The results of this study showed that straw mulch, film mulch, root barrier and increased spacing treatments increased the soil water content in the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system, and that film mulch performed significantly better than others (

Figure 2). Similarly, many studies have shown that mulching can inhibit soil evaporation and improve the soil moisture environment, and the soil moisture preservation capacity of film mulch is better than that of straw mulch [

20,

21]. Film mulching can effectively reduce the intensity of soil evaporation, optimize soil structure, promote rainfall infiltration, reduce surface runoff and prevent soil moisture loss [

22]. Straw has a high water-absorption capacity, a semi-closed structure and a cooling effect, which can reduce the intensity of soil evaporation, increase rainfall infiltration and improve soil water-holding capacity [

23]. Root barriers can reduce or isolate competition for soil water from the root systems of trees and crops in intercropped systems and improve soil is water conditions in intercropped areas [

18,

24]. The planting distance from the apple tree rows was greater in the increased spacing treatment (1.2 m) than that in the control treatment (0.4 m), which reduced the competition between apple trees and

Polygonatum sibiricum for soil moisture in the intercropping system, and improved the soil moisture conditions.

The application of film mulching has been demonstrated to significantly promote the growth of new branches and the relative chlorophyll content of apple trees, as well as increasing plant height, aboveground biomass and yield of

Polygonatum sibiricum (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4,

Table 2). Consequently, film mulching represents an excellent l agronomic measure for apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping systems. The practice of film mulching has been demonstrated in numerous studies to enhance the growth and yield of apple trees and crops [

21,

25,

26]. The application of straw mulching also facilitated the growth of apple trees and the growth and yield of

Polygonatum sibiricum (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4,

Table 2). However, the increase was not statistically significant. This may be attributed to the fact that although straw mulching can enhance soil conditions, including moisture, temperature and nutrient conditions [

15,

27], its capacity to retain moisture is not substantial. Therefore, the observed improvement in the growth of apple trees and the growth and yield of

Polygonatum sibiricum was not statistically significant. A substantial body of research has reached similar conclusions that straw mulching increases the growth and yield of apple trees and crops [

15,

17]. In addition, many studies have shown that film mulching gives better results than straw mulching in terms of crop yield [

17,

21,

28,

29]. The implementation of root barriers and increased spacing treatments both facilitated the growth of

Polygonatum sibiricum (

Figure 4). However, the utilization of root barriers had a considerable impact on the horizontal extension of the root system of the apple trees, which in turn affected the uptake of soil resources by the trees. This resulted in a considerable negative impact on the amount of new branch growth and the relative chlorophyll content of the apple trees. It can be concluded that the implementation of root barriers is not conducive to the healthy and sustainable development of the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system. It is therefore recommended that root barriers be employed as a research instrument and not as a management practice for apple–crop intercropping systems. The increased spacing treatments were found to have a beneficial impact on the growth of apple trees and

Polygonatum sibiricum. However, the yields of both the root barrier and increased spacing treatments in the intercropping system were found to be inferior to that of the control treatment (

Table 2). Moreover, the yield of

Polygonatum sibiricum in the increased spacing treatment was found to be significantly reduced. This was due to the fact that the root barrier and increased spacing treatments, respectively, comprised two and four fewer rows of

Polygonatum sibiricum in the entire apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum system than the other treatments. It can be posited that the implementation of root barriers, increased spacing and straw mulching measures is not an optimal strategy for enhancing the growth and productivity of the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system. It is therefore recommended that film mulching be applied to the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system, with a view to improving the growth and productivity of the components of the system.

4.2. Responses of Growth and Yield of the Intercropping System to Supplemental Irrigation

The application of supplemental irrigation has been demonstrated to result in enhanced growth of new branches and an increase in the relative chlorophyll content of apple trees (

Figure 6). There is a general consensus that the irrigation of apple trees on the Loess Plateau is conducive to their growth [

15,

30,

31]. The new branch growth and relative chlorophyll content of apple trees demonstrated that the T9 treatment resulted in superior growth outcomes, followed by T8 and then T7 (

Figure 6). This suggests that the growth of intercropped apple trees with higher supplemental irrigation was more favorable. The application of supplemental irrigation treatments T5, T6, and T9 resulted in a notable enhancement in relative chlorophyll content and new branch growth in apple trees, with the most pronounced improvement observed in T9 (

Figure 6). The lower limit of supplemental irrigation for both T5 and T6 treatments was set at 85% of the field water holding capacity at the seedling–flowering stage of

Polygonatum sibiricum. This indicates that setting a higher lower limit of supplemental irrigation at the seedling–flowering stage of

Polygonatum sibiricum is highly beneficial for the branching and the relative chlorophyll content of apple trees. This may be attributed to the fact that the period between early May and early June represents the peak of new growth for apple trees. This period is typified by robust growth and elevated transpiration, which gives rise to a considerable imbalance between the supply and demand of water by apple trees [

32,

33]. This period coincides with the seedling–flowering stage of

Polygonatum sibiricum. In consideration of the factors of new branch growth and the relative chlorophyll content of apple trees, the T9 treatment was determined to be the optimal choice.

The results demonstrated that both plant height and aboveground biomass of

Polygonatum sibiricum in the supplemental irrigation treatment were greater than that of the control (

Figure 7), thereby indicating that the application of supplemental irrigation had a positive effect on the growth of the intercropped

Polygonatum sibiricum in the Loess Plateau region. The results demonstrated a pattern whereby the plant height and aboveground biomass of the

Polygonatum sibiricum exhibited a hierarchy of decreasing values from T9 to T8 to T7 (

Figure 7). This suggests that the growth of the

Polygonatum sibiricum was enhanced by an increased amount of supplementary irrigation throughout the growth period. This may be attributed to the fact that the experimental settings for supplementary irrigation in this study were set within the range of positive effect. The T9 and T2 treatments resulted in a statistically significant increase in

Polygonatum sibiricum yield, with an increase of over 50% compared to the control treatment. Additionally, the water use efficiency of the T2 treatment was significantly higher than that of T9, while the difference in water use efficiency between T9 and the control treatment was not statistically significant (

Table 3). These findings suggest that a moderate water deficit may be a more conducive factor for enhancing water use efficiency in apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping systems. The flowering–fruiting stage of

Polygonatum sibiricum consumes the greatest quantity of water, followed by the fruiting–mature stage and the seedling–flowering stage [

34]. Consequently, T2 is more closely aligned with the water consumption pattern in

Polygonatum sibiricum.

The supplementary irrigation treatments T5, T6, and T9 were found to significantly enhance new branch growth and relative chlorophyll content in apple trees (

Figure 6). Additionally, T5 and T6 were observed to significantly increase the aboveground biomass of intercropped

Polygonatum sibiricum, although the plant height and yield of

Polygonatum sibiricum were found to be insignificantly enhanced (

Figure 7). Nevertheless, the water use efficiency of T5 was markedly inferior to that of T2, while that of T6 was less than that of the control. The T9 treatment was observed to significantly enhance the chlorophyll and new branch growth of apple trees in the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system. However, the water use efficiency of the T9 treatment was found to be significantly smaller than that of the T2 treatment, and the difference between the T9 and control treatments was not significant (

Table 3). It can be concluded that the supplemental irrigation design for T9 is not an appropriate solution given the current status of water scarcity in the area. In contrast, the supplemental irrigation T2 treatment resulted in enhanced relative chlorophyll content and new branch growth of apple trees in the apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system. Moreover, the supplemental irrigation T2 treatment resulted in a significantly increased yield of

Polygonatum sibiricum. Furthermore, the T2 treatment demonstrated the highest water use efficiency among all the treatments. In conclusion, the establishment of a lower irrigation limit at 55%, 85% and 75% of the field water holding capacity at the flowering–fruiting stage, fruiting–mature stage and seedling–flowering stage of

Polygonatum sibiricum in apple–

Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping systems, respectively, can assist in alleviating interspecies soil water competition in the intercropping system and enhance the growth, yield and water use efficiency of the intercropping systems.

It should be noted that this study is not without limitations. Firstly, Polygonatum sibiricum possess both medicinal and culinary properties. This study focused on the Polygonatum sibiricum was studied only as a crop, and further research is required to investigate the content of medicinal substances in Polygonatum sibiricum under different mulching and supplemental irrigation conditions. Secondly, apple–crop intercropping systems are typically selected from apple trees that are less than or equal to seven years of age on the Loess Plateau of China. The present study was conducted for only two years, which may be considered a relatively brief research period. Thirdly, the irrigation method in this study is diffuse irrigation, which mainly focuses on the situation of inadequate of water supply facilities in the orchard. Further research is required to investigate a range of irrigation techniques, including drip and sprinkler irrigation, as well as the deployment of irrigation belts. Fourthly, interspecific competition for soil water and nutrients is intense in apple–crop intercropping systems. Consequently, comprehensive research on the regulation of water and fertilizer is required in apple–Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping systems. Further research is recommended to investigate the efficacy of measures such as biodegradable mulch film and green manure in apple–Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping systems.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study revealed that straw mulch, film mulch, root barrier and increased spacing treatments increased the soil water content in the apple–Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system, and that film mulch performed significantly better than others. The application of straw mulch did not significantly facilitate the growth of apple trees and the growth and yield of Polygonatum sibiricum. The implementation of root barriers and increased spacing treatments both facilitated the growth of Polygonatum sibiricum. However, the utilization of root barriers had a detrimental impact on the amount of new branch growth and the relative chlorophyll content of the apple trees. Furthermore, the yields of both the root barrier and increased spacing treatments in the intercropping system were found to be inferior to that of the control treatment. The application of film mulching has been demonstrated to significantly promote the growth of new branches and the relative chlorophyll content of apple trees, as well as increasing plant height, aboveground biomass and yield of Polygonatum sibiricum. In the Loess Plateau region, where precipitation resources are scarce, we conducted an analysis of the growth, yield and water use efficiency of the components of an apple–Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system. The film mulching measure was employed in the context of the apple–Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system. Moreover, supplemental irrigation was implemented in three distinct areas of the intercropping system: the fierce competition area on the south side of the tree row, the central competition area and the fierce competition area on the north side of the apple tree row. And the lower irrigation limits of the Polygonatum sibiricum at the flowering–fruiting stage, fruiting–mature stage and seedling–flowering stage of Polygonatum sibiricum were set at 55%, 85% and 70% of the field water holding capacity, respectively. These measures can assist in alleviating interspecies soil water competition in the apple–Polygonatum sibiricum intercropping system and enhance the growth, yield and water use efficiency of the intercropping system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; methodology, Y.S. and W.M.; software, W.M. and H.L.; validation, Y.S., C.L. and D.W.; formal analysis, Y.S., B.Q. and R.X.; investigation, D.W. B.Q. and R.X.; resources, Y.S.; data curation, Y.S. and C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.S. and H.L.; visualization, Y.S.; supervision, Y.S. and H.L.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province of China (21JR11RM042), the Education Department of Hunan Province of China (2021B–273 and 2023B–216) and the Doctoral Fund of Longdong University (XYBY202002).

Data Availability Statement

Data related to the research are reported in the paper. Any additional data may be acquired from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support from the Gansu Key Laboratory of Conservation and Utilization of Biological Resources and Ecological Restoration in Longdong, Qingyang, Gansu, China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

WUE: water use efficiency.

References

- Meng, P.; Zhang, J.; Fan, W. Research on Agroforestry in China, 1rd ed.; Chinese Forestry Press: Beijing, China, 2003; pp. 1–4.

- Bi, H.; Yun, L.; Zhu, Q. Study on the Interspecific Relationships of Agroforestry Systems in the Loess Area of Western Shanxi Province, 1rd ed.; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2011; pp. 20–109.

- Xing, L.; Zhao, L.; Cui, N.; Liu, C.; Guo, L.; Du, T.; Wu, Z.; Gong, D.; Jiang, S. Apple tree transpiration estimated using the Penman-Monteith model integrated with optimized jarvis model. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 276, 108061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2022.108061. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wen, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Liao, Y. Mulching practices altered soil bacterial community structure and improved orchard productivity and apple quality after five growing seasons. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 172, 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2014.04.010. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Han, Z.; Si, J. Huangjing (Polygonati rhizoma) is an emerging crop with great potential to fight chronic and hidden hunger. Sci. China Life Sci. 2021, 64, 1564–1566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-021-1958-2. [CrossRef]

- Si, J.; Qiu, H.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, D.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, J. Development strategy of Huangjing industry. Strategic Stu. CAE 2024, 26, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bi, H.; Guo, M.; Sun, Y.; Duan, H.; Peng, R. The spatial and temporal distribution of shade under apple trees with conventional intercropping system in west Shanxi Loess area. Agric. Res. Arid Areas 2019, 37, 185–191.

- Xu, H.; Bi, H.; Gao, L.; Liao, W.; Chen, J.; Yun, L.; Bao, B.; Yang, Z. Microclimate and its effects on crop productivity in the Malus pumila and Glycine max intercropping systems on the Loess Plateau of West Shanxi Province. Sci. Soil Water Conserv. 2014, 12, 9–15.

- Cannell, M.G.R.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Ong, C.K. The central agroforestry hypothesis: The tree must acquire resources that the crop would not otherwise acquire. Agroforestry Syst. 1996, 34, 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00129630. [CrossRef]

- Huxley, P.A.; Pinney, A.; Akunda, E.; Muraya, P. A tree/crop interface orientation experiment with a Grevillea robusta, hedgerow and maize. Agroforestry Syst. 1994, 26, 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00705150. [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Xu, H.; Bi, H.; Xi, W.; Bao, B.; Wang, X.; Bi, C.; Chang, Y. Intercropping competition between apple trees and crops in agroforestry systems on the Loess Plateau of China. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70739. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070739. [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.K.; Corlett, J.E.; Singh, R.P; Black, C.R. Above and below ground interaction in agroforestry systems. For. Ecol. Manag. 1991, 45, 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1127(91)90205-A. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, B.D.; Riha, S.J.; Ong, C.K. Light interception and evapotranspiration in hedgerow agroforestry systems. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1996, 81, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1923(95)02303-8. [CrossRef]

- May, R.; McLean, A.R. In Theoretical Ecology: Principles and Applications, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 84–97.

- Yang, Y.; Yin, M.; Guan, H. Responses of soil water, temperature, and yield of apple orchard to straw mulching and supplemental irrigation on China’s Loess Plateau. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14071531. [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Liu, R.; Li, H.; Gao, X.; Wu, P.; Zhang, C. Optimizing soil moisture conservation and temperature regulation in rainfed jujube orchards of China’s Loess hilly areas using straw and branch mulching. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2121. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13082121. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-Y.; Turner, N.C.; Gong, Y.-H.; Li, F.-M.; Fang, C.; Ge, L.-J.; Ye, J.-S. Benefits and limitations to straw- and plastic-film mulch on maize yield and water use efficiency: A meta-analysis across hydrothermal gradients. Eur. J. Agron. 2018, 99, 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2018.07.005. [CrossRef]

- Wanvestraut, R.H.; Jose, S.; Nair, P.K.R.; Brecke B.J. Competition for water in a pecan (Carya illinoensis K. Koch)-cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) alley cropping system in the southern United States. Agroforestry Syst. 2004, 60, 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:AGFO.0000013292.29487.7a. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Bi, H.; Xu, H.; Duan, H.; Peng, R.; Wang, J. Below-ground interspecific competition of apple (Malus pumila M.)–soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) intercropping systems based on niche overlap on the Loess Plateau of China. Sustainability 2018, 10(9), 3022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093022. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Pan, X.; Gao, C.; Wang, Y.; He, F. Effects of tillage and mulching measures on soil moisture and temperature, photosynthetic characteristics and yield of winter wheat. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 201, 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2017.11.003. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Ma, J.; Chai, Y.; Song, W.; Han, F.; Huang, C.; Cheng, H.; Chang, L. Mulching improves the soil hydrothermal environment, soil aggregate content, and potato yield in dry farmland. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2470. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14112470. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Wu, P.; Ye, X.; Zhang, P.; Jia, Z. Continuous years of biodegradable film mulching enhances the soil environment and maize yield sustainability in the dryland of northwest China. Field Crops Res. 2022, 288, 108698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2022.108698. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Cao, X.; Li, J.; Cao, R.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z.; Dong, Z. Response of soil moisture and water use efficiency to straw mulching amount and mulching period in black soil zone of northeast China. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2023, 103, 634–641. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjss-2023-0018. [CrossRef]

- Zamora D S, Jose S, Nair P K R. Morphological plasticity of cotton roots in response to interspecific competition with pecan in an alley cropping system in the southern United States. Agroforestry Syst. 2007, 69(02): 107-116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-006-9022-9. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Wang, R.; Dou, X.; Luo, C.; Wang, X.; Xiao, W.; Wan, Q. Soil moisture, nutrients, root distribution, and crop combination benefits at different water and fertilizer levels during the crop replacement period in an apple intercropping system. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2706. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13112706. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Xue, X.; Kamran, M.; Ahmad, I.; Dong, Z.; Liu, T.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, P.; Han, Q. Plastic film mulching stimulates soil wet-dry alternation and stomatal behavior to improve maize yield and resource use efficiency in a semi-arid region. Field Crops Res. 2019, 233, 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2019.01.002. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lövdahl, L.; Grip, H.; Tong, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q. Effects of mulching and catch cropping on soil temperature, soil moisture and wheat yield on the Loess Plateau of China. Soil Tillage Res. 2009, 102, 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2008.07.019. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, C.; Liang, M.; Chen, P.; Anwar, S.; Fan, M.; Xie, G.; Wang, C. Exploring the influence of planting densities and mulching types on photosynthetic activity, antioxidant enzymes, and chlorophyll content and their relationship to yield of maize. Plants 2024, 13, 3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13233423. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Wang, R.; Zhou, X.; Li, C.; Dou, X. Photosynthetic and growth characteristics of apple and soybean in an intercropping system under different mulch and irrigation regimes in the Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 266, 107595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2022.107595. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, L.; Niu, X.; Qin, L.; Xiang, Y.; Guo, J.; Wu, Q. Effect of water-fertilizer coupling on the growth and physiological characteristics of young apple trees. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2506. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13102506. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Cao, H.X.; Xue, W.K.; Liu, X. Effects of the combination of mulching and deficit irrigation on the soil water and heat, growth and productivity of apples. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 243, 106482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106482. [CrossRef]

- Meng, P. Characteristics of apple tree transpiration and models for prediction and diagnosis of water stress. PhD Thesis, Central South Forestry University, Changsha Hunan, China, 2005.

- Geng, B. Law of transpiration and water consumption in apple orchard in Shandong hilly area. PhD Thesis, Shandong Agricultural University, Tai’an Shandong, China, 2013.

- Xu, X. Research on photosynthetic characteristics and water consumption of Polygonatum sibiricum Red. Master Theses, Northwest A&F University, Yangling Shanxi, China, 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).