The research questions as they arise from the cinematographic material itself, are: How the historical memory of traumatic events of the previous century such as the exchange of populations according the Treaty of Lausanne is recorded in the cinematographic narrative? What are the historical sources? To what extent did the origin, ethnicity, geographical location of the narrators as participants influence the preservation of historical memory and the historical research? What are the criteria of the approach of the creator, what are the criteria of the participants?

Methodologically, we apply the historic and the socio-semiotic analysis in the field of the public and digital history.

The results: the types of historical sources found in filmic public discourse are the oral narration of testimonies, of experiences and of memories, the director’s historical research in state archives, the material culture objects and the director’s digital research. Thus, historic thematic categories occur, such as a) the specific persons and actions by country in Turkey/Greece, by action as on-site and online research, by type of historical source, as oral testimonies, as research in archives, as objects of material culture. B) Sub-themes such as childhood, localities and kinship also emerge.

Discussion: these cinematic recording of biographical, oral narratives as historical and sociological material helps us to understand the political ideologies of the specific period 1919-1923. The multimodal film material is analyzed as testimonies of oral and digital history and it is utilized to approach the historical reality of the "otherness", seeking the dialogue in cross-border history in order to identify differences, but above all the historic and cultural similarities vs the sterile stereotypes. The historic era and the historic geography as Greek and as Turkish national history concern us for research and teaching purposes a hundred years after the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) which set the official borders of the countries.

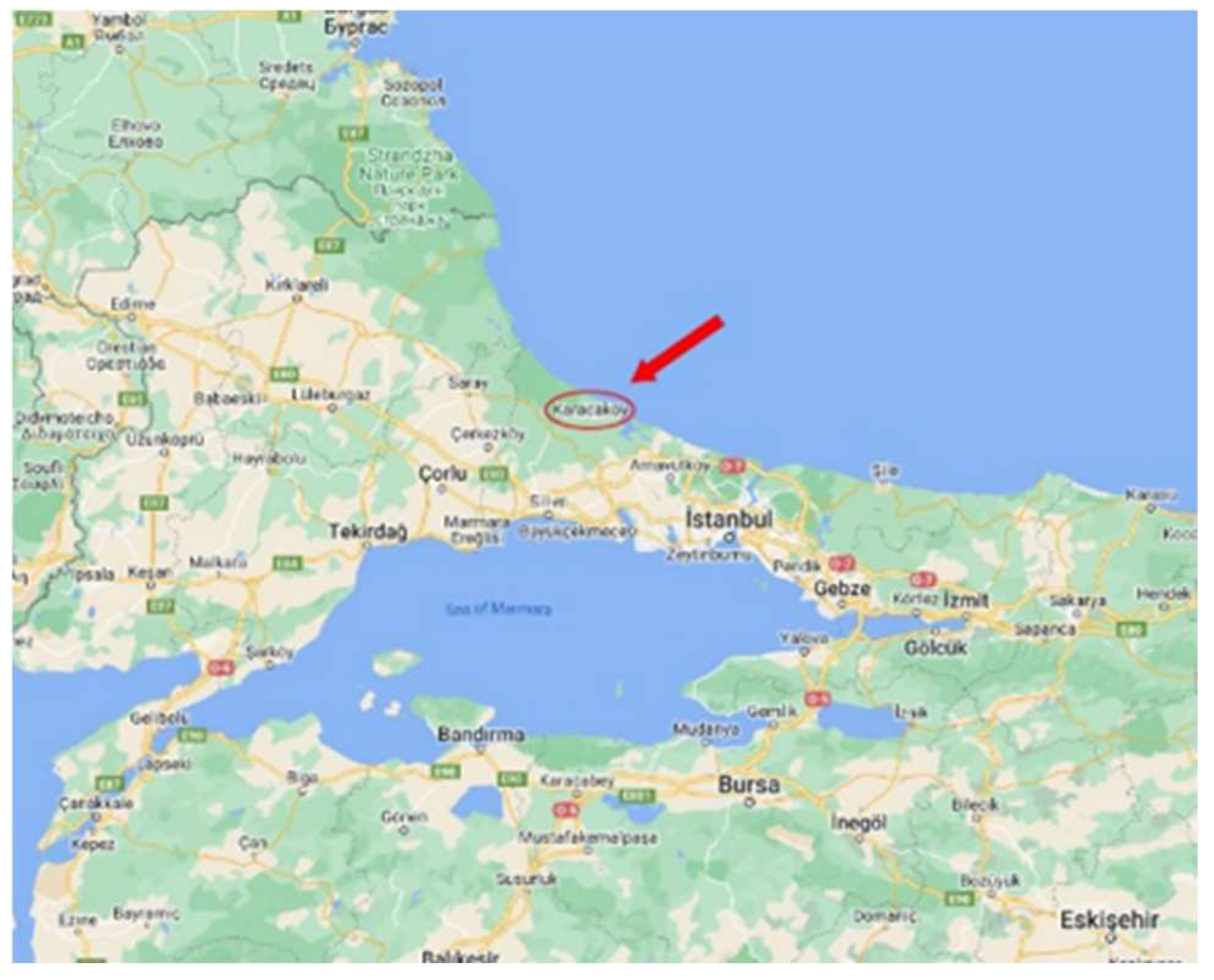

Figure 2.

Google Maps - Karacaköy, location of finding.

Figure 2.

Google Maps - Karacaköy, location of finding.

Instead of a preface

"As for the Others, that's where we probably don't know much: the Other is elsewhere, and he's otherworldly. And as my life is intertwined every moment with Others, how can I achieve a good life when I am ignorant of the nature of Others and my Relationship with them..." (Tassios, 2016).

Introduction to historical methodologies

The positivist approach to historical sources defined the dominance of written sources and especially official records from the 19th-century as German historian Leopold von Ranke had estimated (see in Mavroskoufis, 2016). Today, however, with the introduction of multimodal media and the utilization of the World Wide Web, prospects are opening for a more complete and objective recording of History and for equal access to it (Cohen & Rosenzweig, 2005). The world, as represented by modern electronic media, appears diverse and produces diverse historical and social narratives. Thus the use of visual and oral narratives help us to give meaning in a direct and concrete way to events that happened once and elsewhere and about which we know accordingly the evidence we record and analyze. Film narratives have broadened the 'inside' examination of experiences, thoughts and feelings, so that the historical subjects themselves render the historical interpretation and develop historical criticism.

In this study we follow the renewal of interest in the biographical and narrative approach, after its first appearance at the beginning of the 20th century, that is related to its ability to study social phenomena in their dynamic dimension and historical formation (Tsiolis, 2010). We also accept in historiography, the stream of oral history, which raises the demand for a "history from below" that aims to give voice to anonymous and excluded from the public discourse of the historical process (Thompson as cited in Tsiolis, 2010). Class, race, ethnicity, language, religion, gender, nationality seem to produce differences in how we remember and tell our lives. Cultural values shape the very ordering and ordering of events, while political ideology also shapes the construction of memory (Sangster, 1994). From this point of view, we can say that no story can be innocent, pure, and above all objective. This in itself constitutes, perhaps, the greatest "truth" (Samuel & Thompson et al. in Nazou 2007, p. 678).

The documentary as the filmic narrative that is based on real events and does not use traditional elements of fiction, such as script, actors, costumes, lighting, etc. it records the existing reality, without constructing a reality anew, as in the case of fictional cinema. As a historical source of information about the era and its reference society, the documentary is an object of study, both for the representations of the past that are recorded, and for the revelation of reality as it was experienced by the historical subjects (Vamvakidou, Sotiropoulou, 2011). The historical documentary as a multimodal genre produces with its appearance the signified spectacle of which it is the signifier. The creator, being aware of the ideological representation carried out by the use of the codes, consciously constructs them with the ultimate aim of associativeness and pointing out the desired "truth".

In this methodological context, we perceive the historical documentary as a public historic narrative oriented towards research and practice concerns the public and social relationship with History (Demantowsky 2018, p. 4).

Public History is based on the form and nature of the transmission of historical knowledge to a wider audience (Kean, 2010). The knowledge that public historians gain from working with the public in a variety of settings, the knowledge of how historical knowledge is created, institutionalized, disseminated, and understood, can help revitalize the entire historical profession as it redefines itself both professionally and intellectually in years to come (Glassberg 1996, p. 8).

As a field of study, Public History focuses on the historical culture of a society, on the representations of the past that dominate the minds of citizens. Public History is not only interested in understanding historical culture, it is also interested in changing it (Parasidis, 2020).

The difference between History as we know it and Public History is defined by who asks the questions that must be answered by historians. Academic history serves humanity's general need to understand the past and to impart that understanding through formal education to each generation.

In Public History historians, as expert advisors, answer questions posed by others (Kelley 1978, p. 18), while the public has free access to the findings of historical research (Tosh et al. as cited in Dawson 2012).

In our case as public and digital history we define this particular historical documentary because of the thematic and historical public research it records and captures.

RESEARCH MATERIAL

The film "Searching for Rodakis" is perceived as research material so that the plot and actions, the people, the geographies, the ideologies and policies, the languages and the musics that “happen” between Turkey and Greece, can be analyzed and taught.

It presents the historical investigative and agonizing effort of the film's creator, Kerem Soyylmaz, to locate relatives-descendants of a Greek woman, whose tombstone was found in his grandparents' house in the village of Karacaköy in Turkey, which had a Greek population before the exchange of populations (1922-1923).

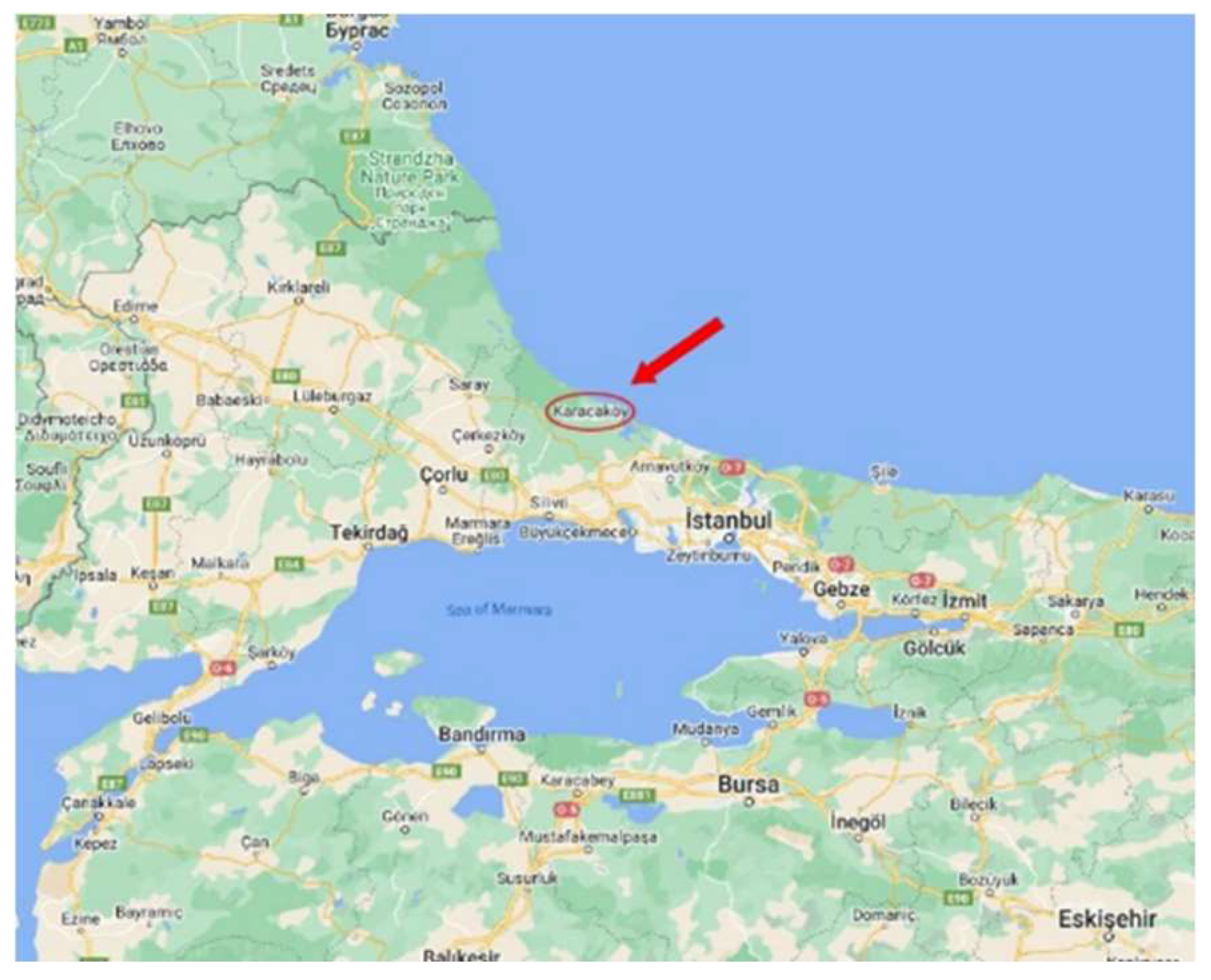

Figure 3.

Google Maps - Karacaköy in Turkey.

Figure 3.

Google Maps - Karacaköy in Turkey.

Kerem Soyyilmaz, seems to apply the "New History" (from the early 80s), which aimed to strike a balance between the transmission of knowledge about the past and the provision of the means that would allow us to develop historical thinking regarding the past. Historians’ engagement with the social sciences, which was promising and multi-dimensional into the 1970s, shriveled soon thereafter. The factors that seemed to justify this turning away appear today to be much less compelling. Times have changed, and both historians and social scientists may now be ready to re-engage with an interrupted project to intensify interdisciplinary dialogue, improve the methods of historical explanation, and construct a more historical body of social theory. Most historical phenomena can be interpreted and reconstructed from a variety of perspectives, which reflect the limitations of the evidence, the subjective interests of those who interpret and reconstruct them, and the changing cultural influences that determine, to some extent, what each new generation considers important in the past.

The multi-prismatic view of the teaching of History, utilizing the promotion of new material productions of public history, such as this particular film, responds to the concerns raised in the new multicultural, multilingual and multinational environment that has been formed worldwide, within which young people are called to coexist harmoniously as "global' citizens (Stradling, n.d.) and this is also the purpose of the present analysis.

Theoretical and Methodological Models

The modern rules of analysis of historical sources incorporate the findings resulting from the systematic examination of the socio-cultural and linguistic-communicative context in which the historical source was created and the creator lived.

In this way, we utilize in inventive ways the theories about the narrative and its reception, as well as the processes of forming mental representations. The relationship between the concepts of historical literacy and historical reasoning is two-way dialectical. Historical reasoning empowers us to understand history in particular, and social life in general, since it is linked to our ability to reason about historical issues, rather than uncritically accepting or rejecting a historical narrative (Barton & Levstik et al. as cited in Mamoura, 2016).

Such processes can lead to our participation in terms of autonomy in a democratic society. Historical reasoning means the ability to judge historical sources, to emphasize the consequences of historical processes and their interpretation, so as to understand the influence of the past on the formation of the present (Rüsen et al. as cited in Mamura, 2016).

This ability thus becomes an important prerequisite for the formation of historical consciousness. In the multimodal material of historical documentary, the ideological/representational meta-function of images as visual modes refers to the ability to represent "aspects of the world as people experience them", to represent "objects and their relationships" (Kress & Van Leeuwen 2010, pp. 98, 99).

The reception of cinema as a new kind of language has evolved into a variety of theoretical descriptions of cinema (Pärn, 2012). In this field, we chose the visual/semiotic analysis of the documentary, with references to the historical and political context.

Similarly, the creator of the specific film focuses on the type of narrative and, by extension, the type of public filmic and ideological discourse that he chooses each time, depending on the evolution of his research and filmic search.

Social-Semiotic Analysis of The Documentary

We follow the "study of signs" as the study of what we call "signs" in everyday language, but also of everything that represents something else and includes, in addition to words, images, sounds and objects, which are studied as part of a semiotic system of signs.

As a manifestation, the literal meaning of the sign is described, while co-manifestation draws from its literal signifier, leading to socio-cultural, but also personal associations (Chandler, 1994). In multimodal film material, manifestation is what is filmed and co-presentation is about how it is rendered (Fiske 1990, p. 86).

The thematic analysis (we also apply to the episodes of the multimodal material concerns the trace of death of the material cultural object, the tombstone with the Greek inscription, which participates in the evolution of the filmic narrative and thus documents the stages of the search and the production of the documentary.

It is about the local stories as the village in Turkey, as childhood, as family ties, as community, as state authorities.

At the same time, we perceive the villages in Greece, the descendants of the refugees, the modern Turkey, the director’s research as tour of geography, as a digital historical research on the Internet, as a research in social media.

The creator of the film, Kerem Soyyilmaz made a public appeal for finding the Greek descendants and finally he managed a historical redemption, by placing the plaque in a museum.

Documentation of the Research Material

"The director knows that beneath the surface of the image there is a subtext, a 'diary' of intentions, feelings and inner processes" (Kazan, 1973).

Similar to a writer, the creator of a film creates his own "book". In this informal art-language coexistence, we find greater freedom in terms of what can be "said", and this "liberation" takes place both on a political-economic level and on an ideological level - a freedom that presupposes a degree of autonomy (Metz, 1974).

The creator of the documentary, "Searching for Rodakis", Kerem Soyyilmaz, was born in 1984 in Besiktas, Istanbul. He studied at the Department of Television and Cinema of Yeditepe University, at the New York Film Academy and has postgraduate studies in Music at Istanbul Technical University. He focuses on creating multimodal content, such as short films, commercials and podcasts, in Copenhagen where he has been living for the last few years and is involved in intercultural programs between Turkey and Denmark.

The documentary "Searching for Rodakis" is the first feature film of the director, who is actively present in intercultural events and is interested in human rights. He participated in documentary festivals around the world. In addition to Greece (Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival) and Turkey, the film has been screened in Canada, Germany and Denmark, countries with a strong Turkish population. The documentary "Searching for Rodakis" Produced by Denmark, Turkey 2023, Screenplay/Director: Kerem Soyyilmaz, Duration: 57', received the awards: Adana Golden Boll FF 2023 Turkey | Best Documentary, Thessaloniki International Doc. Festival 2023 Greece, Los Angeles Greek Film Festival 2023 USA, Documentarist Istanbul Documentary Film Days 2023 Turkey.

We perceive the specific documentary as a historical research material because it visualizes the Treaty of Lausanne: the production year of the film as 2023, coincides with the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, where Turkey's current borders were set and the "population exchange" legally decided.

That is, the violent expulsion of 400,000 Muslims, citizens of Greece, many of whom spoke only Greek, and 200,000 Orthodox citizens of Turkey, most of whom spoke Turkish. At the same time, the Treaty ratified and finalized the expulsion of approximately one million Orthodox who were forced to leave the Ottoman Empire as well as 120,000 Muslims who fled Greece after the beginning of the Balkan wars (Lunardi & Dimoulis, 2023).

About two million people emigrated, lost their citizenship and property, in the context of "national homogenization", with the official states indifferent to the criticisms of lawyers and academics who spoke of violations of constitutional rights, of Greek, but also of international law. The implementation of the mutual and compulsory exchange of the Greek and Turkish populations put an end to the persecution and the ongoing extermination of the Greeks, but it did not take into account other, equally important, factors of the concept of the nation, beyond religion. Mohammedan Greeks, estimated at around 190,000 as early as 1914 based on ecclesiastical statistics in the Pontus region, were not heeded by the provisions of the Treaty of Lausanne even though linguistically and culturally they did not differ in anything from the orthodox Greeks (Fotiadis 1993, p. 222).

In Turkey there was general indifference to the thousands of people who arrived in desperation, with the exception of a few academics and the Lozan Mübadilleri Vakfi (see the official material Lozan Mübadilleri Vakfi

http://www.lozanmubadilleri.org.tr/kisaca-mubadele/#).

Narrative Material as Script-Plot

During renovation work in a Turkish house, a stone tombstone was found under the floor with the engraved inscription in Greek: "The servant of God Chrysoula Rodaki died on the eighteenth of March 1887". The relatives of the documentary maker, who found the plaque in the grandparents' house, inform him of the find and he decides to investigate and learn the history of this woman, but also to document this effort, filming live interviews with the camera in the field of research and using also digital archives, data and social media.

Results

We are watching the actual event in a Turkish house, where a historical, cultural object – an engraved tombstone – is found on the floor. So we identify the following signifiers as the space: private, indoor, the language: Greek, the object: trail of Death, the identity: a Christian woman.

The documentary maker decides to locate the relatives/descendants of the deceased and document this effort as it unfolds. Thus, four historic thematic categories emerge as geographical signifiers, as digital historic archives, as national and family’s signifiers, as historical persons and historical monuments: a) Turkey- Turks, testimonies, narratives, research, state authorities, b) Internet- Appeal, response, information gathering, exploitation, c) Greece- Greeks, locating descendants/relatives, testimonies, stories, d) Turkey- Greeks, visit to ancestral home, placement of tombstone in museum.

Turkey- We perceive the specific episodes as A1. Family "council" with relatives, narratives as memories and descriptions of past and present reactions. A2. The fellow villagers, their narratives as oral contemporary testimonies, the tour of the camera and collaborators to places of historical/religious interest in the village and A3. The official State Authorities in Turkey as censuses as archival entries as property ownership title, as official written historical testimonies of another era. Signifiers are captured as geographic location: Turkey and public external locality, as a linguistic signifier: Turkish and memories from 1922-1923, as different identities: Turks, Muslims, men, women, family/kinship/local ties.

Internet-Episodes-B1.World wide web/social media – post-appeal – response of internet users, B2.On-site contact with a Greek resident of Istanbul, a musician willing to help. Signifiers as World Wide Web/Social Media, as digital Reality and its space, as public linguistic signifier: English and memories of previous identities: Greek, Turkish, Male, Female, Non-kin.

Greece-Episodes-First approach of Greeks-descendants of refugees, visiting them and debating in Greek area.

Turkey-Episodes-D1. Visit of descendants to the ancestral home, D2. Placement of the tombstone in a museum. The signifiers which are involved, as countries, are Turkey: the tenants of the house, the relatives, the members of the local community, the villagers and the employees of the government services and a Greek resident of Istanbul, who volunteered to assist in the research, as did many strangers to the director Kerem Soyyilmaz, following his appeal on the Internet and whose motivations were mainly their origin, but also the subject of their studies. Greece as communities of 2nd and 3rd generation refugees, descendants of refugees, but also natives from Imbros island with knowledge of Turkish. In the geographical space, communities and family ties dominate as contributing forces in the search with dominant emotional, national and historical discourse. In the online space, people unknown to the author are voluntarily mobilized, willingly providing information and advice on good research practices with a dominant bibliographic and digital discourse. The "others" are depicted in Turkey as: the Greeks previous inhabitants of the villages/houses and in Greece as: the Turks who expelled the Greeks from their ancestral homes. Actions are traced as car movement, tour of the tombstone with a repeating zoom pattern as a special angle shot through the trunk of the car in which the director transports the tombstone and foregrounds the reactions of the people to whom he exposes the historical object. Thus the film director orientates our gaze to form an opinion about the cultural significance of the object, as it is shaped by the geographical location and historical background of the participants. Starting from the reactions of his own family of relatives, who identified the plaque and the residents of the village where it was found, he also cites historical facts, which emerge from the stories of the locals. This is followed by archival official public research in government agencies, with the assistance of the director's aunt - current owner and co-leader of the action - about the previous owners of the house, where we are informed that records exist only from the 1950s, so the oral narration of memories by the locals is the only source of information. The appeal to the users of social media, as a research outlet, has a response and people unknown to him provide him with information and advice on search tactics. The geographical localization of the refugee descendants of the specific village and, specifically, the family descendants of the deceased, brings the film maker to the country of relocation of these people, Greece, where he gets to know them and hears the story, this time from the their side. The last step of this effort is the visit of the descendants of Chrysoula Rodakis to their ancestral homes, the approach of the current owners/residents, the contact with the material object-the reason for this trip to Memory for both peoples and its symbolic restoration, with its placement in a museum.

Discussion

The main narrator is the director-historical researcher, who, together with his second narrator and researcher aunt, "guide" us through historical memory, starting with the birthplace of the discovery.

The architecture of the old Thracian house that stands just before the collapse in the new Turkish village, imposes itself on us theatrically, emotionally and mnemonically (Ritzouli 2021, Gavra 2004, Molfetta & Komini 1993).

Thematically and multimodally we listen and watch, almost smell, the narrative unfolding with the memories of the author's childhood in the old Greek home of the Turkish informants, the smell of burning oak for charcoal, the fishing, the stream, the churches that were torn down. We do learn about a Greek granddaughter who was looking for information in the 80s, the Greek visitors of the same era to the villages of their ancestors, the gold-hunting interest of the inhabitants, the questions about the burial of Westerners, Christians.

We do follow the memories of the Turkish informants, mostly men, the comparison with Germany where they immigrated, some younger informants participate in the multiple narratives, with the transition to historical time spiraling from the past (1923-) to the present (2023) and both ways confirming historical events, such as for Christians, Turkish- Greeks (they call them Ruma), who abandoned money and possessions in the hope of return.

We learn about this return which never happened, because the Treaty of Lausanne ratified this forced movement/renunciation of property and citizenship, of these people who were exchanged like objects, a fact that is now disputed historically and politically (Fotiadis, 1993).

The Black Sea, the sound of the clarinet, the village of Karacaköy itself, the etymological and linguistic, bilingual and trilingual signifiers (Karatza means the roe deer), the youthful-temperament European-Turkish co-guide/tour aunt Ayten, structure the cinematic narrative in filmic time.

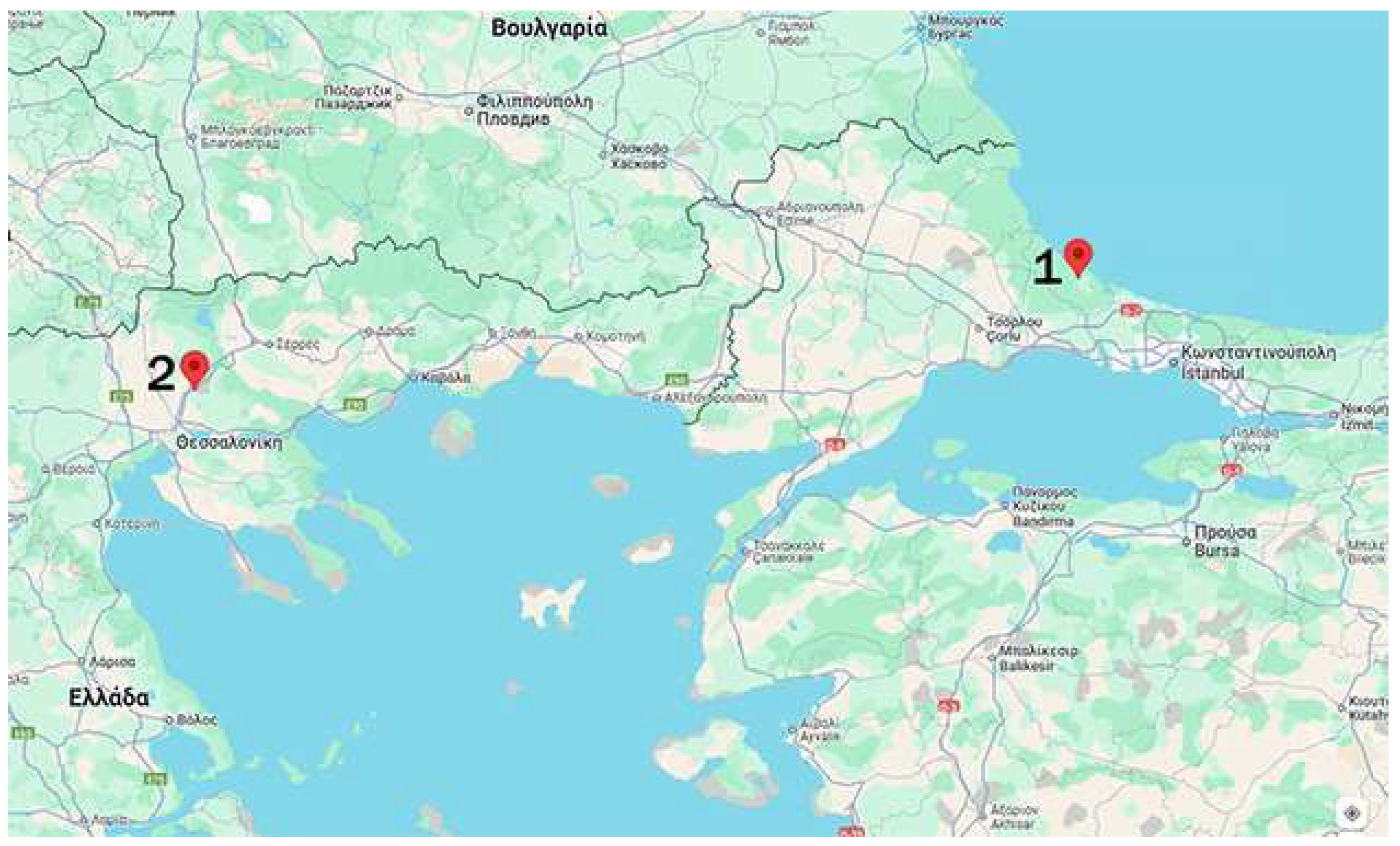

We watch and learn about the Greeks of Turkey, the Turks of Greece, with examples of memory – the oldest uncle Ibrahim from Thessaloniki, the Greek tourists from the new village of Dorkada who cried when they saw how the Christian cemetery in their old village (Karacaköy) evolved.

Figure 4.

Google Maps, 1=Old village in Turkey, 2=New village in Greece.

Figure 4.

Google Maps, 1=Old village in Turkey, 2=New village in Greece.

We meet the Turkish uncle Ali, with early-stage dementia, with the director's critical literacy connotations for the monetary consideration he "bargains" for his contribution to the film. We meet Uncle Ethem, who narrates the visit of a Greek descendant with the connotations of the author's co-narrator aunt, regarding the visitor's attire and the reactions of the couple who welcomed her. We learn about the real family of Theodoros Georgiadis, the descendants of the aunt who was buried in the Christian house in the Turkish village. We experience the trauma of the displacement with a redemptive final scene and the feast as a meal of reconciliation, but also a memorial to Aunt Rodaki, with the dishes of the East that seem Greek and Turkish.

Fictionally and cinematically we experience and enjoy the limits of poetics, which is present when words and their meaning acquire value of their own and of the emotional function-expression of the creator (Jacobson 1998, p. 62, 137).

In this way, the "one-way" cinematic communication is negated in this project, precisely because the codes are already known to Greek and Turkish receivers.

We listen to the Turkish love songs as songs of separation from people and homelands as a farewell and memorial to the Greek Aunt, to the Christian ancestors, to the Muslims, to everybody forced to move without having a choice, to everybody exchanged as being objects, while epoch images/videos enrich the closing credits music.

The documentary features also eponymous women, such as Fani Nitsoglou, Elena Apostolidou from ERT, Tuba Emiroğlu, but also anonymous members of communities. The Turkish women in the yard of the house and some during the tour of the tombstone by car in the Turkish village, the Greek women-descendants of refugees in the cafe of the first Greek village that is approached and who are perspicuously fewer than the Turkish.

The same applies to the men, the Turks who appear and contribute to the research, either as residents of the village in coffee shops and barbershops, or as relatives of the author, are numerous than the Greeks, who are also the descendants of the deceased, while an equaly important person is the bilingual Greek, originating from Imbros island, who facilitates the director's first contact-communication with the Greek descendants by translating.

We also learn from this documentary about the visits of Greeks in the 80s to the paternal/maternal homes in Turkey, which were the first massive and organized visits, and we learn that not all Turks tried to profit from the valuables of the Greeks, who were leaving their properties in a hurry, but some have already saved them.

Finally we see the Foundation of Lausanne Treaty, Turkey's first immigration museum, which was founded with the support of the European Capital of Culture 2010, the collaboration of the Lausanne Treaty Foundation and Municipality of Çatalca and opened in 2010, where the tombstone is placed.

The common reference to the grief of losing a loved one expressed through rain, by the director's twin cousins in the final scene "when a loved one dies, it rains" when the tombstone is placed in its final position "the sky cries" as we say in Greece. The aunt's perception, that many in the village learned History, the History that either as a window or as a mirror we did not face, completes the historical narrative of the modern dialectical and conciliatory director, the European citizen and artist.

More results

Answering the research questions, the following emerge: I. Historical sources as oral histories, as experienced and interpreted by the people of the "other" side, in terms of patterns common to the two peoples, such as the exchange of populations, loss of property and changes in the cultural environment, such as the razing of religious ritual sites - demolished church and school built on ruined Greek cemeteries - but also the stirring up of "old" stories. The reactions of the participants in Turkey range from indifference to empathy and critical historical position. It is indicative that there is no encouragement for this effort because finds from the Greek era were also common in the past and indeed quite a few, but the current residents focused on the finds that could improve their lives, i.e. golden coins and valuables.

A high index of historical empathy is found in the reactions of the inhabitants to the type of find, especially when they learn that it belongs to a young girl, while at the same time we receive the information about this type of burials of the time -1889 the date written on the tomb, when the Greeks buried the dead in their yard, because they were not allowed to be buried in cemeteries, and placed the tombstones inside the house.

The memory emerges effortlessly though not willingly and the collective experience is expressed by the reference of the sociologist, Tuba Emiroğlu, to the Lebanese intellectual Jalal Toufic, who talks about the "haunting" of places with a "heavy" history, places where deaths have taken place, which acts as a deterrent in terms of post-traumatic memory loss, referring to the universal burden of the shadow of wrongful death and collective trauma.

The reactions of the participants in Greece are different and are mainly characterized by a willingness to assist in the research, but also to tell their own story to the "other" who approaches them. The types of historical sources used were: Oral narration of testimonies/experiences/memories• Research in government records• Objects of material culture.

Geographical signifiers emerge as the local area where the director moves which is familiar topographically, sartorially and socially, as the Turkish rural landscape that unfolds during his journey is similar to the Greek one. People's clothes too, as well as items of social culture (utensils, decorations, reference to TikTok).

The resolution of the story/plot occurs as an approach, finally, to the Greek side accompanied by corresponding narratives from the relatives of the deceased, but also the descendants of third generation refugees, who willingly assist in the director's research when he travels in Greece to get to know the descendants of Chrysoula Rodakis. The latter travel in turn to Turkey to visit the place where their ancestors lived. During this interaction, historical, cultural elements that unite us emerge as the architecture of houses, the grandmothers who cooked the same pie, the Greek-Turkish coffee, and the material object-cause for this journey in History is settled in its new place, in the geographical area, where it was located in a migration museum.

The types of history that arise is A) a religious one as the mutual respect for expression of religiosity, respect for the death. B) a cultural history, the international common habitus in everyday life C) Gender history as the Turkish liberated female dress code for some women D) Cross-cultural history as a linguistic marker with similarities in the rendering of common meanings in a different language E) Social history as similarities reflected in the sanctity of death, in the 'haunting', in the collective experience, in the disagreement with state/political decisions such as the leveling of cemeteries.

The similarities emerge effortlessly and even timeless as "cultural disagreements", such as the rendering of the name of our national coffee, Greek or Turkish (?) which are sidelined during the essential approach of the two sides.

The types of literacy that emerge by analyzing the documentary are the Historical as the study of History, questioning stereotypes, the Social as understanding social phenomena and their justification and the Critic as decoding visual "text" and the identities.

We are asked to transfer these results coded to the lessons of modern Greek and European history with the targeted use of film material and multi-literacies (Wilson, Dudley, Dutton et al., 2023).

References

- Chandler, Daniel (1994): Semiotics for Beginners [WWW document] URL http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/S4B/ [Date accessed, 5/12/2024].

- Cohen Dan & Rosenzweig Roy. (2005). Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Dawson, G. (Ed.). (2012). Memory, Narrative and Histories: Critical Debates, New Trajectories: in Working Papers on Memory, Narrative and Histories, 1.

- Demantowsky, M. (2018). What is Public History. In M. Demantowsky (Ed.), Public History and School: in International Perspectives (1st ed., pp. 3–38). De Gruyter. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvbkk2pq.4.

- Fiske, J. (1990). Introduction to Communication Studies. London: Routledge.

- Glassberg, D. (1996). Public History and the Study of Memory: in The Public Historian, 18(2), 7–23.

- Kazan, E. (1973). What makes a director. Wesleyan University.

- Kean, H. (2010). People, Historians, and Public History: Demystifying the Process of History Making: in The Public Historian, 32(3), 25–38.

- Metz, C. (1974). Film language: A Semiotics of the Cinema. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Pärn, K. (2012). Language of cinema and semiotic modelling: in Chinese Semiotic Studies, 6, 324-332.

- Sangster, J. (1994). Telling our stories: feminist debates and the use of Women's History: in Review, 3(1), 5-28.

- Tosh, J. (2008). Why History Matters. Basingstoke. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wilson, K., Dudley, D., Dutton, J., Preval-Mann, R. and Paulsen, E. (2023). A systematic review of pedagogical interventions on the learning of historical literacy in schools: in History Education Research Journal, 20 (1), 9. IN GREEK.

- Vamvakidou, I., Sotiropoulou, E. (2011). Semiotic Reading of Historical Documentary: Democratic Army 1946-1949: in Experience and Transportation. Experience, Transfer and Multimodality: Applications in Communication, Education, Learning and Knowledge, edited by Marios Pourkos and Eleni Katsaros, Ch. 23. Ed. Islands.

- Gavra E. (2004). Cultural stock and architectural heritage in the Balkans, Management in the context of European integration. Thessaloniki: Kyriakidis Brothers.

- Jacobson, R. (1998). Essays on the language of literature. Berlis, A. (transl.). Athens: Hestia.

- Kotsarian Z., Loukaidis L., Brahim A., Shinto M., Toukou O., Feuerstein B., Fotiadis K., Hoffman T. (1993). Multiethnic Turkey. Athens: Gordios.

- Lunardi, S. & Dimoulis, D. (2023, July 23). Treaty of Lausanne: when the victims did not hear an apology. Retrieved from NEWS24|7: https://www.news247.gr/history/sinthiki-lozanis-otan-ta-thimata-den-akousan-mia-singnomi/.

- Mamoura, M. (2016). Developing graduate students' historical literacy during their internship. The role of the learning community: in Early Childhood & School Education, 4(1), 212-225.

- Mavroskoufis, D. (2016). Looking for the traces of History: Historiography, teaching methodology, historical sources. Thessaloniki: Kyriakidis.

- Molfetta, N., Komini, D. (Transl). (1993). Balkan traditional architecture. Athens: Melissa.

- Nazou, P. (2007). Oral history and memory: the mythologizing of a reality: the case of Greek 'consular brides' in Australia. Greek research in Australia: proceedings of the seventh biennial international conference of Greek Studies (pp. 675-688). Flinders University.

- Parasidis, Z. (2020, May 17). Public History is all that makes us disagree on Social Media. Retrieved from Propaganda: https://popaganda.gr/stories/dimosia-istoria-ine-ola-ekina-pou-mas-kanoun-na-diafonoume-sta-social-media/.

- Ritzouli A. (2021). Introduction to the industrial heritage of western Thrace. Xanthi: Pakethra.

- Stradling, R. (n.d.). Council of Europe. Retrieved May 28, 2024, on Multi-Prismatic Perspectives in History Teaching: https://rm.coe.int/1680494155 [Date accessed, 5/12/2024].

- Tasios, Th. (2016). Let us reflect on ourselves and each other. Athens: University Press of Crete.

- Tsiolis, G. (2010). The Timeliness of the Biographical Approach to Qualitative Social Research. In M. Pourkos, & M. Dafermos (Ed.), Qualitative Research in the Social Sciences: Epistemological, Methodological and Ethical Issues (pp. 347-370). Athens.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).