1. Introduction

The increased incidence of fungal infections in humans, particularly among immunocompromised individuals, is a major public health issue [

1,

2]. Dermatophytosis is among the most common fungal infections, primarily caused by

Trichophyton rubrum, in keratinized tissues such as the skin and nails [

3,

4].

Treating fungal diseases is generally protracted and expensive, with the risk of developing antifungal resistance [

5,

6], a critical evolutionary phenomenon in fungi to adapt to extreme conditions [

6,

7]. Moreover, although genetic mutations in fungi occur at a relatively low frequency, the selective pressure exerted by the continuous use of antifungal agents favors the emergence of resistant strains, which eventually dominate the population [

3]. Furthermore, only a few drugs can combat these pathogens owing to the limited number of cellular targets [

1,

8].

Repurposing of sertraline (SRT), an antidepressant with antifungal activity, is a promising therapeutic strategy for various fungal diseases. Owing to its established safety profile and mechanisms of action, the use of SRT decreases the duration and cost associated with the development of novel therapeutics. SRT is effective as both a monotherapy and in combination with other antifungal agents [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

The antifungal efficacy of SRT was first reported in 2001, which indicated its potential as a therapeutic agent. Specifically, SRT was used to treat three patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder and recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, eliminating symptoms of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis and exhibiting antifungal activities against

Candida albicans,

C. glabrata, and

C. tropicalis. These findings underscore broad-spectrum antifungal properties of SRT [

15]. In mammals, SRT selectively impedes serotonin reuptake by blocking the 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter [

16].

In yeast cells, SRT targets the phospholipid membranes of acidic organelles [

17]. Furthermore, SRT exerts antifungal effects against

Cryptococcus neoformans by obstructing translation, thereby inhibiting protein synthesis [

18]. SRT also impedes the transition of

C. auris from yeast to the hyphal form, reducing biofilm formation by 71 % and causing significant cellular membrane damage [

19]. Understanding the intricate mechanisms of action of SRT in

T. rubrum and the mechanism by which it reacts to different conditions is essential for its clinical use against dermatophytes.

Several factors contribute to

T. rubrum adaptation, including alternative splicing (AS) [

3], a post-transcriptional regulatory mechanism that generates different mRNAs from a single gene. AS is a complex phenomenon and enhances protein diversity and non-coding RNA production in response to factors such as host conditions, drug exposure, and nutrient availability [

20]. This mechanism has been reported in various clinical important pathogens, such as

C. albicans and

C. neoformans [

21,

22]. Intron retention (IR) is the most common AS event in

T. rubrum and other filamentous fungi [

23,

24].

Protein kinases play crucial roles in fungi, serving as part of evolutionarily conserved adaptation mechanisms shared across species from yeast to humans [

25]. Serine/arginine protein kinases (CMGC/SRPKs) represent a distinct protein cohort vital for post-translational modifications. The CMGC kinases include cyclin-dependent, mitogen-activated protein, glycogen synthase, and CDC-like kinases. These kinases are essential for cellular signal transduction pathways and regulate cell cycle, growth, and specialization. SRPKs are involved in serine/arginine protein phosphorylation, a vital process governing constitutive splicing and AS in

C. albicans and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae [

26].

In this study, we investigated the changes in global AS events in the transcripts of T. rubrum cultivated with sub-inhibitory SRT concentrations, with a particular example of the modulation of IR events in the SRPK transcripts (TERG_07061).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Alternative Splicing Analysis

We analyzed RNA-seq data [

27] from the Gene Expression Omnibus [

28], database (accession number: GSE218521) to detect AS events in

T. rubrum cultivated in SRT. The sequencing reads from the RNA-seq data were aligned to the

T. rubrum reference genome using STAR aligners [

29]. ASpli package was used to identify AS events using the R software version 4.3.1 [

30]. Differential expression analysis was performed using the Bioconductor DESeq package [

31]. The Benjamin–Hochberg adjusted p-value was set to 0.05, and a cut-off of ±1.0 log2 fold-change was used to assess the significant expression differences [

32].

2.2. Strain and Growth Conditions

The

T. rubrum strain CBS118892, obtained from the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute (Utrecht, Netherlands), originated from a patient with onychomycosis. The strain was grown on malt extract agar (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for 21 d at 28 °C, as previously described [

27]. Conidial concentration was estimated using the Neubauer chamber with 0.9 % NaCl. Approximately 1 × 10

6 conidia were added to 100 mL of liquid Sabouraud medium (Becton Dickinson), followed by pre-cultivation at 28 °C for 96 h under continuous shaking. The resulting mycelia were transferred to 100 mL of liquid Sabouraud medium containing either a sublethal dose of SRT (70 mg/L; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) or no drug (control) and incubated at 28 °C with shaking (120 rpm) for 3 and 12 h. The minimum inhibitory concentration of SRT for

T. rubrum was determined following the recommendations of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, as previously reported [

14].

2.3. Reverse Transcription-Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) and Conventional PCR

We evaluated the

TERG_07061 gene, which encodes a CMGC/SRPK protein kinase and exhibited IR3 events in RNA-seq assays at 3 and 12 h of SRT exposure. Gene expression was quantified via qPCR using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). Both qPCR and conventional PCR were performed using specific primer pairs designed with the Prime3Plus software (

https://www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/primer3plus/primer3plus.cgi). The primers used for qPCR assays targeted specific regions of the transcripts, either including or excluding IR3 [

24], whereas those for conventional PCR assays were designed to flank the intronic region [

33] (Supplementary

Figure 1). All primer sequences are shown in Supplementary

Table 1. Genes encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II served as endogenous controls for qPCR [

34]. The thermocycler conditions for qPCR were as follows: an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min [

14]. PCR products were visualized on a 2 % agarose gel, as previously described [

33].

2.4. In Silico Analysis of SRPK Isoforms

The

TERG_07061 gene sequence was identified using the Ensembl Fungi database (

https://fungi.ensembl.org), using the coordinates for the retained intron (start: 209028 and end: 209083). Using the BLAST tool [

35], we searched for sequence similarity between the two SRPK isoforms (conventional and IR3). Then, the domains within the two isoforms were identified using the Interpro database [

36]. To predict and align the three-dimensional models of the two isoforms, we used AlphaFold2 and PyMOL, respectively. Subsequently, the Illustrator for Biological Sequences (IBS 1.0) was used to represent each isoform graphically [

37].

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Gene expression levels were calculated using the comparative 2

−∆∆CT method [

38]. A paired Student’s

t-test was used to compare the gene expression levels between the treatment and control groups at each time point (3 and 12 h). Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent biological replicates. One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to compare the treatment and control groups. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Prism v. 5.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to generate graphs for statistical analysis.

3. Results

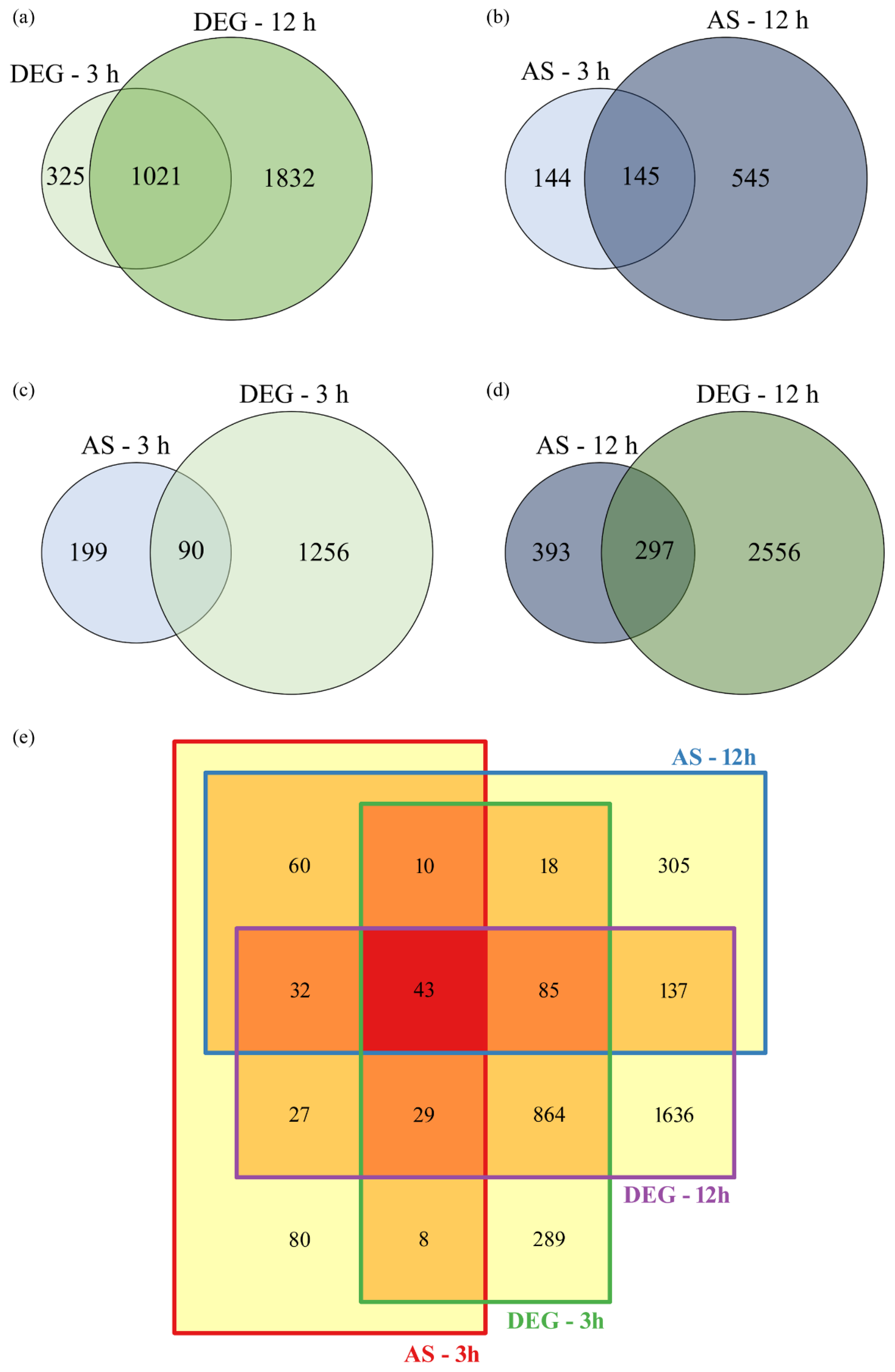

The

T. rubrum transcriptome revealed 1,346 and 2,853 differentially expressed genes (DEG) after 3 and 12 h of SRT treatment, respectively (

Figure 1A). Notably, 1,021 genes exhibited differential expression independent of the culture time. Additionally, AS events were identified in 289 and 690 genes after 3 h and 12 h of SRT treatment, respectively. Of these, 145 genes did not show time-dependence (

Figure 1B).

Several genes exhibited differential expression and AS events simultaneously at 3 h (

Figure 1C) and 12 h (

Figure 1D) of SRT treatment. The 289 genes that underwent AS after 3 h of SRT treatment corresponded to approximately 21 % of all DEGs (

Figure 1C). This percentage increased to 24 % after 12 h of treatment (

Figure 1D). Transcriptome analysis also revealed 43 genes that were simultaneously modulated, exhibiting differential expression and AS events at 3 h and 12 h (

Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Venn diagrams illustrating the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and the genes that underwent alternative splicing (AS) after Trichophyton rubrum exposure to sub-lethal doses of sertraline (SRT) for 3 and 12 h. (a) DEGs at 3 and 12 h. (b) AS at 3 and 12 h. Relationship between the number of genes undergoing AS and DEGs at 3 h (c) and 12 h (d). (e) Total DEGs and AS modulated at 3 and 12 h.

Figure 1.

Venn diagrams illustrating the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and the genes that underwent alternative splicing (AS) after Trichophyton rubrum exposure to sub-lethal doses of sertraline (SRT) for 3 and 12 h. (a) DEGs at 3 and 12 h. (b) AS at 3 and 12 h. Relationship between the number of genes undergoing AS and DEGs at 3 h (c) and 12 h (d). (e) Total DEGs and AS modulated at 3 and 12 h.

A peculiar expression pattern was observed in these genes: the induction of differential expression downregulated AS events, and vice versa. This trend persisted in genes involved in multidrug resistance, transcription factors, and one gene involved in eukaryotic translation initiation (

Supplementary Table 2). Using the ASpli package, IR was identified as the most common AS event in

T. rubrum cultivated in the presence of SRT. IR events primarily occurred at 12 h, with over 1,000 detected events. At 3 h, nearly 100 % of all AS events were of the IR type (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Alternative splicing events observed in response to sertraline.

Table 1.

Alternative splicing events observed in response to sertraline.

| Time |

AS genes |

Intron retention events |

Others AS events |

Total events |

| 3 h |

289 |

349 |

2 |

351 |

| 12 h |

690 |

1025 |

26 |

1051 |

We observed a large proportion of protein kinase-encoding genes among the differentially expressed genes in RNA-seq analysis. At 3 h, 63 protein kinase-encoding genes were modulated, increasing to 132 at 12 h [

27]. Therefore, we analyzed AS events in protein kinase-encoding transcripts. In total, 16 protein kinase-encoding transcripts underwent AS at 3 h and 41 underwent AS at 12 h in the SRT group compared to those in the control group. In addition, some genes exhibited more than one AS event (

Supplementary Table 3).

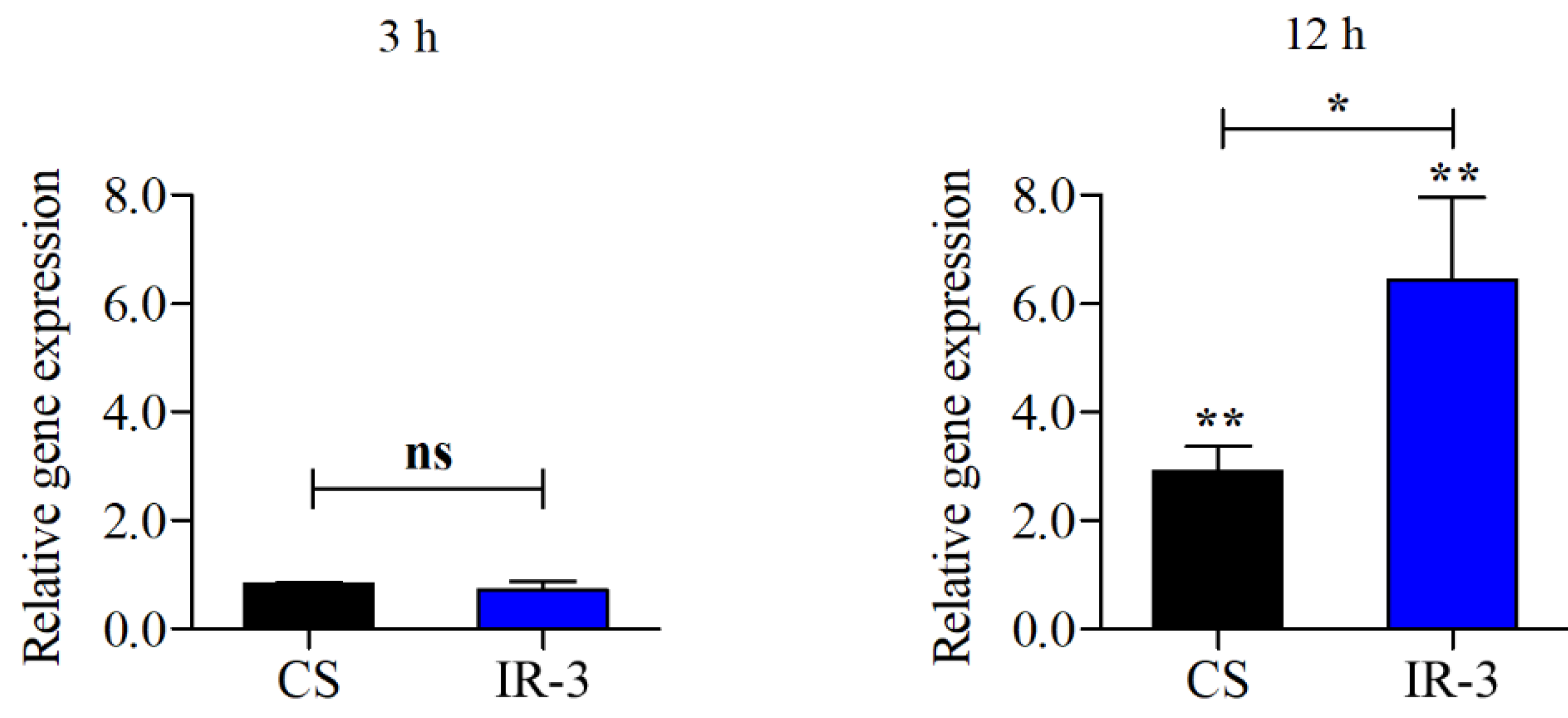

TERG_07061, which encodes a CMGC/SRPK protein kinase, exhibited distinct behavior among the protein kinase-encoding genes. RNA-seq data revealed that this gene was repressed in response to SRT exposure. In contrast, IR3 was induced after 3 and 12 h of SRT treatment (

Supplementary Table 2). Therefore,

TERG_07061 was selected for subsequent validation of AS events, initially through RT-PCR (Supplementary

Figure 1). The relative expression levels of the conventional isoform and the variant containing IR3 were quantified using RT-qPCR. The IR3 variant levels were significantly higher after 12 h of SRT exposure than that for the control without SRT (

Figure 2).

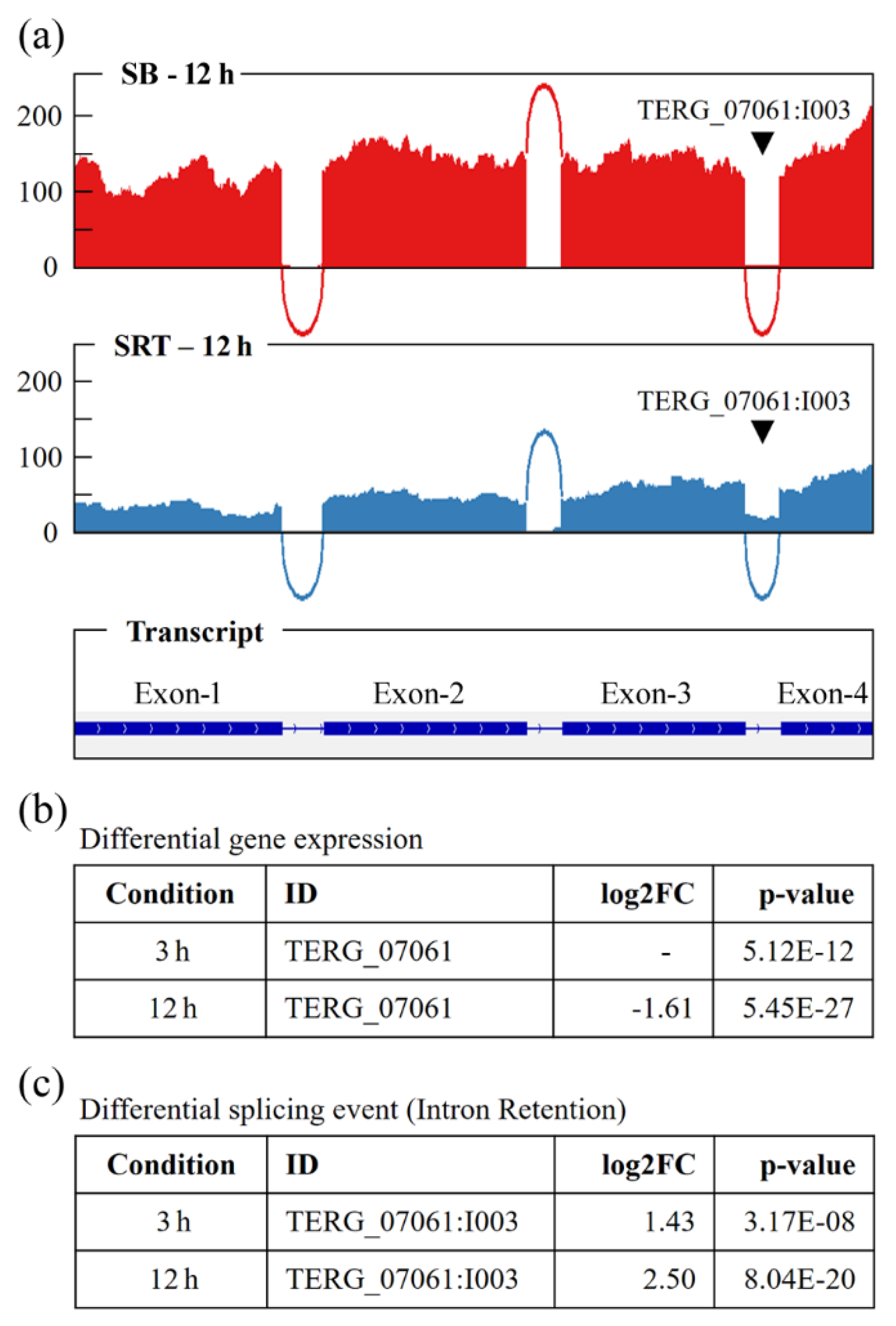

Figure 3 shows the Sashimi plots of IR3 in the

TERG_07061 gene, with the alignment of readings obtained from RNA-seq analyses of the 12-h SRT treatment group, differential expression data, and IR3 events.

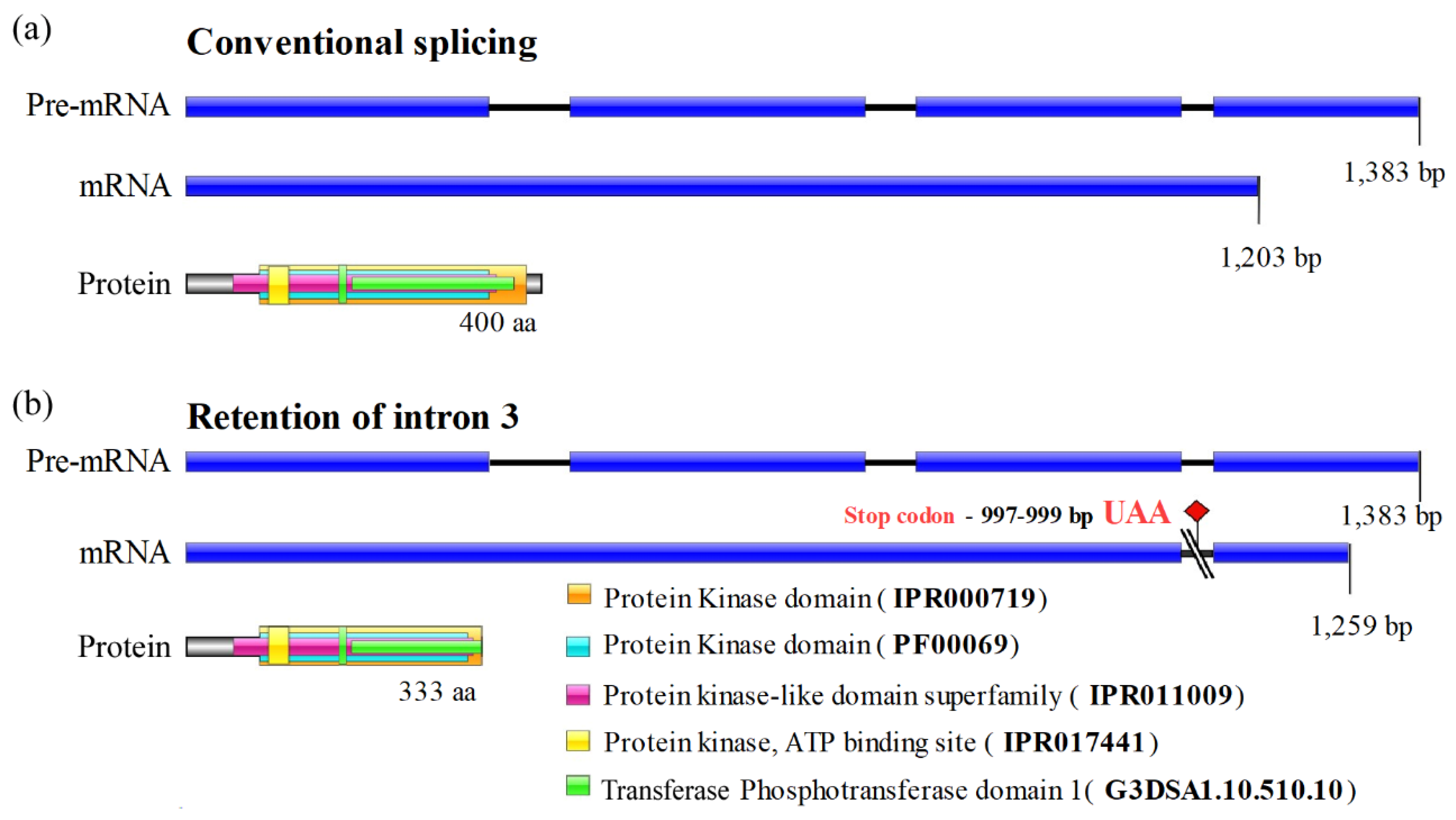

Usually,

TERG_07061 gene processing results in an mRNA of 1,203 bp, yielding a single protein isoform with 400 amino acids. The pre-mRNA transcript contains three introns, as shown in

Figure 4 and in the Ensembl Fungi database. When intron 3 was retained, a premature stop codon (UAA) was generated at bases 997–999 downstream of the start codon, resulting in an alternative isoform with 333 amino acids (

Figure 4).

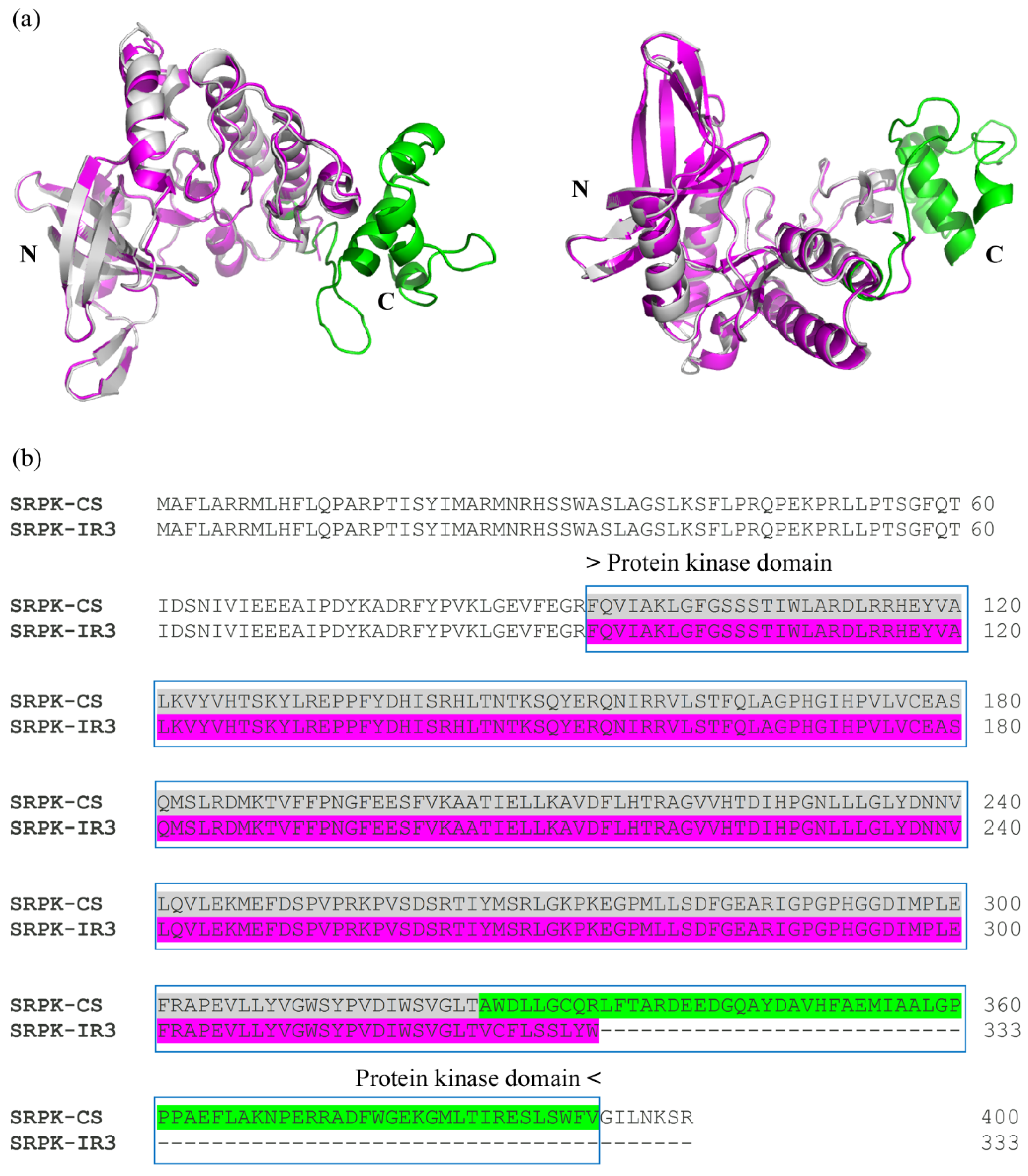

Using InterPro, a database that facilitates functional protein analysis via classification into families and prediction of domains and crucial sites, we found that the IR3 isoform preserved all CMGC/SRPK protein domains. However, alterations were observed in the transferase (phosphotransferase) domain, which lost part of its terminal region. Alignment of the protein kinase domains of both isoforms (conventional and IR3) indicated perfect identity up to the C-terminal region, where the amino acids of the IR3 isoform corresponded to part of intron 3 (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

AS events are associated with many biological processes, including development, drug resistance, adaptation to biotic and abiotic stress, response to pH changes, and virulence [

24,

33,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. This study revealed IR as the most common AS event in

T. rubrum challenged with SRT, which is consistent with previous reports, including those by our research group [

20,

40,

44,

45].

IR induces both adaptation and resistance to drugs by modulating gene expression, creating proteomic diversity, and facilitating rapid phenotypic changes. These responses enhance the organism’s ability to survive and thrive under drug-induced stress [

21,

45,

46]. Some isoforms are active only under drug-induced stress, helping the organism adapt using alternative metabolic pathways [

44]. In this study, we observed the modulation of AS events in multidrug resistance and transcription factor transcripts, reflecting the intricate mechanisms developed by fungi to adapt to drug-induced stress, possibly conferring drug resistance.

This study also highlights the role of SRT exposure time in the incidence of AS events in T. rubrum. The longer the exposure time, the greater the number of genes exhibiting AS events, which correlating the with fungal adaptation mechanisms. These findings reveal the potential of targeting splicing events in drug therapy against fungi, paving the way for developing novel antifungal drugs.

Modulation of AS to overcome drug stress was previously identified in

C. albicans using RNA-sequencing data from isogenic pairs of azole-resistant and -sensitive isolates [

22].

In S. cerevisiae, IR governs cellular survival under starvation conditions, highlighting the significance of this mechanism in nutrient-deprived environments [

47]. We previously demonstrated that the protein kinase encoded by the PAKA/STE20 gene, which plays a crucial role in mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction, retains intron 1 after exposure to undecanoic acid [

33]. Moreover, we showed that the modulation of AS in genes encoding heat shock proteins facilitates adaptation to various stressors [

41].

Different pre-mRNA isoforms may coexist in

T. rubrum, and in the presence of SRT, the fungus modulates the expression of each isoform according to cellular requirements. We hypothesized that the induction of the SRPK IR3 isoform in

T. rubrum in response to SRT is an adaptive strategy to counteract the repression of this gene caused by the drug. This repression likely triggers the activation of alternative pathways, such as the expression of non-canonical isoforms integrated into a regulatory network that maintains cellular equilibrium and homeostasis. Consequently, the selective production of isoforms underlies specific cellular functions in response to distinct stimuli [

22,

48,

49].

However, the SRPK IR3 isoform encodes a putative kinase that loses part of the phosphotransferase domain, which probably alters its three-dimensional structure and affects its ability to interact with the substrate. Alternatively, the SRPK IR3 isoform may be involved in regulatory functions. For example, IR is essential for the mRNA accumulation of some genes in

C. neoformans [

21]. IR regulation could also be a mechanism to adjust gene expression levels in response to environmental factors, supporting pathogen survival and proliferation under various conditions [

21,

50].

5. Conclusions

In summary, SRT affects both transcriptional and post-transcriptional events in T. rubrum. Our investigation revealed the modulation of AS events, particularly IR, in several genes of T. rubrum in response to SRT. This finding, along with the observation that the number of AS events increases with drug exposure time, and that some genes undergo both AS and expression modulation simultaneously, presents a promising area for further exploration. Notably, SRT does not induce these AS events directly; rather, they are modulated by its presence, likely as an adaptive mechanism. Our study confirmed the existence of a new isoform of the SRPK gene containing IR3, although there was no evidence that the putative protein would be functional. However, this isoform could assume distinct functionalities, such as gene regulation or altered kinase activity, compared with the conventional isoform. This discovery underscores the need for further research to better understand the potential implications of the isoforms revealed by RNA-seq analysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1. Validation of alternative splicing event. Table S1. Primer sets used in conventional PCR and RT-qPCR assays. Table S2. List of 43 differentially expressed genes modulating alternative splicing events in response to sertraline. Table S3. Alternative splicing events in the pre-mRNA of kinase genes in response to sertraline.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and N.R.; Methodology, C.R., F.R. and P.S.; Validation, C.R. and F.R.; Formal Analysis, C.R., F.R. and P.S.; Investigation, C.R., F.R. and P.S.; Software, P.S.; Visualization, C.R., F.R. and P.S.; Data Curation, P.S.; Supervision, A.R. and N.R.; Project Administration, N.R.; Funding Acquisition, A.R. and N.R.; Writing – review & editing, C.R., A.R. and N.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) [grant number 2019/22596-9]; National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) [grant numbers 307871/2021-5 and 307876/2021-7]; Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) - Finance Code 001; and Fundação de Apoio ao Ensino, Pesquisa e Assistência (FAEPA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with approval from the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Ribeirao Preto Medical School, USP, Brazil (HCFMRP-USP), under Protocol No. 4.304.317/2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article and the accompanying Supplementary Data.

Acknowledgments

We thank V. M. Oliveira, M. Mazzucato, and M. D. Martins for their invaluable technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wiederhold, N.P. Emerging Fungal Infections: New Species, New Names, and Antifungal Resistance. Clin Chem. 2021, 68, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lass-Flörl, C.; Steixner, S. The changing epidemiology of fungal infections. Mol. Aspects Med. 2023, 94, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Peres, N.T.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Martins, M.P.; Rossi, A. State-of-the-art Dermatophyte infections: Epide miology aspects, pathophysiology, and resistance mechanisms. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.H.S.; Santos, R.S.; Martins, M.P.; Peres, N.T.A.; Trevisan, G.L.; Mendes, N.S.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Rossi, A. Relevance of Nutrient-Sensing in the Pathogenesis of Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton interdigitale. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 858968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Peres, N.T.; Lang, E.A.; Gomes, E.V.; Quaresemin, N.R.; Martins, M.P.; Lopes, L.; Rossi, A. Dermatophyte resistance to antifungal drugs: Mechanisms and prospectus. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins-Santana, L.; Rezende, C.P.; Rossi, A.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Almeida, F. Addressing Microbial Resistance Worldwide: Challenges over Controlling Life-Threatening Fungal Infections. Pathogens 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schikora-Tamarit, M.; Gabaldón, T. Recent gene selection and drug resistance underscore clinical adaptation across Candida species. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 284–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, N.; Samaranayake, L. Emerging and future strategies in the management of recalcitrant Candida auris. Med. Mycol. 2022, 60, myac008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossato, L.; Loreto, É.S.; Zanette, R.A.; Chassot, F.; Santurio, J.M.; Alves, S.H. ; In vitro synergistic effects of chlorpromazine and sertraline in combination with amphotericin B against Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 2016, 61, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadab, A.A.; Rhein, J.; Tugume, L.; Musubire, A.; Williams, D.A.; Abassi, M.; Nicol, M.R.; Meya, D.B.; Boulware, D.R.; Brundage, R.C. Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of sertraline as an antifungal in HIV-infected Ugandans with cryptococcal meningitis. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2019, 46, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, A.; Martins, M.P.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Peres, N.T.A.; Rocha, C.H.L.; Rocha, F.M.G.; Neves-da-Rocha, J.; Lopes, M.E.R.; Sanches, P.R.; Bortolossi, J.C.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M. Reassessing the Use of Undecanoic Acid as a Therapeutic Strategy for Treating Fungal Infections. Mycopathologia 2021, 186, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breuer, M.R.; Dasgupta, A.; Vasselli, J.G.; Lin, X.; Shaw, B.D.; Sachs, M.S. The Antidepressant Sertraline Induces the Formation of Supersized Lipid Droplets in the Human Pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Fungi (Basel) 2022, 8, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donlin, M.J.; Meyers, M.J. Repurposing and optimization of drugs for discovery of novel antifungals. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 2008–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.H.L.; Rocha, F.M.G.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Martins, M.P.; Sanches, P.R.; Rossi, A.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M. Synergism between the Antidepressant Sertraline and Caspofungin as an Approach to Minimise the Virulence and Resistance in the Dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum. J. Fungi (Basel) 2022, 8, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lass-Florl, C.; Dierich, M.P.; Fuchs, D.; Semenitz, E.; Ledochowski, M. Antifungal activity against Candida species of the selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor, sertraline. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, E135–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangkuhl, K.; Klein, T.E.; Altman, R.B. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors pathway. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 2009, 19, 907–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, M.M.; Korostyshevsky, D.; Lee, S.; Perlstein, E.O. The antidepressant sertraline targets intracellular vesiculogenic membranes in yeast. Genetics 2010, 185, 1221–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, B.; Wu, C.; Wang, L.; Sachs, M.S.; Lin, X. The antidepressant sertraline provides a promising therapeutic option for neurotropic cryptococcal infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3758–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowri, M.; Jayashree, B.; Jeyakanthan, J.; Girija, E.K. Sertraline as a promising antifungal agent: Inhibition of growth and biofilm of Candida auris with special focus on the mechanism of action in vitro. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 128, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzafar, S.; Sharma, R.D.; Chauhan, N.; Prasad, R. Intron distribution and emerging role of alternative splicing in fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2021, 368, fnab135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Hilarion, S.; Paulet, D.; Lee, K.T.; Hon, C.C.; Lechat, P.; Mogensen, E.; Moyrand, F.; Proux, C.; Barboux, R.; Bussotti, G.; Hwang, J.; Coppée, J.Y.; Bahn, Y.S.; Janbon, G. Intron retention-dependent gene regulation in Cryptococcus neoformans. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzafar, S.; Sharma, R.D.; Shah, A.H.; Gaur, N.A.; Dasgupta, U.; Chauhan, N.; Prasad, R. Identification of Genomewide Alternative Splicing Events in Sequential, Isogenic Clinical Isolates of Candida albicans Reveals a Novel Mechanism of Drug Resistance and Tolerance to Cellular Stresses. mSphere 2020, 5, e00608–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, N.S.; Silva, P.M.; Silva-Rocha, R.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Rossi, A. Pre-mRNA splicing is modulated by antifungal drugs in the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. FEBS Open Bio 2016, 6, 358–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Santana, L.; Petrucelli, M.F.; Sanches, P.R.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Rossi, A. Peptidase Regulation in Trichophyton rubrum Is Mediated by the Synergism Between Alternative Splicing and StuA-Dependent Transcriptional Mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 930398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahn, Y.S.; Xue, C.; Idnurm, A.; Rutherford, J.C.; Heitman, J.; Cardenas, M.E. Sensing the environment: Lessons from fungi. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luther, C.H.; Brandt, P.; Vylkova, S.; Dandekar, T.; Müller, T.; Dittrich, M. Integrated analysis of SR-like protein kinases Sky1 and Sky2 links signaling networks with transcriptional regulation in Candida albicans. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1108235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvão-Rocha, F.M.; Rocha, C.H.L.; Martins, M.P.; Sanches, P.R.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Sachs, M.S.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Rossi, A. The Antidepressant Sertraline Affects Cell Signaling and Metabolism in Trichophyton rubrum. J. Fungi (Basel) 2023, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clough, E.; Barrett, T. The Gene Expression Omnibus Database. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1418, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, E.; Rabinovich, A.; Iserte, J.; Yanovsky, M.; Chernomoretz, A. ASpli: Integrative analysis of splicing landscapes through RNA-Seq assays. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2609–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. ; Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, Y.; Benjamini, Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat. Med. 1990, 9, 811–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, E.V.; Bortolossi, J.C.; Sanches, P.R.; Mendes, N.S.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Rossi, A. STE20/PAKA Protein Kinase Gene Releases an Autoinhibitory Domain through Pre-mRNA Alternative Splicing in the Dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, T.R.; Peres, N.T.; Persinoti, G.F.; Silva, L.G.; Mazucato, M.; Rossi, A.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M. rpb2 is a reliable reference gene for quantitative gene expression analysis in the dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum. Med. Mycol. 2012, 50, 368–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, S.; Apweiler, R.; Attwood, T.K.; Bairoch, A.; Bateman, A.; Binns, D.; Bork, P.; Das, U.; Daugherty, L.; Duquenne, L.; Finn, R.D.; Gough, J.; Haft, D.; Hulo, N.; Kahn, D.; Kelly, E.; Laugraud, A.; Letunic, I.; Lonsdale, D.; Lopez, R.; Madera, M.; Maslen, J.; McAnulla, C.; McDowall, J.; Mistry, J.; Mitchell, A.; Mulder, N.; Natale, D.; Orengo, C.; Quinn, A.F.; Selengut, J.D.; Sigrist, C.J.; Thimma, M.; Thomas, P.D.; Valentin, F.; Wilson, D.; Wu, C.H.; Yeats, C. InterPro: The integrative protein signature database. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2009, 37, D211–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Xie, Y.; Ma, J.; Luo, X.; Nie, P.; Zuo, Z.; Lahrmann, U.; Zhao, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Ren, J. IBS: An illustrator for the presentation and visualization of biological sequences. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3359–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez, Y.; Brown, J.W.; Simpson, C.; Barta, A.; Kalyna, M. Transcriptome survey reveals increased complexity of the alternative splicing landscape in Arabidopsis. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1184–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, N.S.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Sanches, P.R.; Silva-Rocha, R.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Rossi, A. Transcriptome-wide survey of gene expression changes and alternative splicing in Trichophyton rubrum in response to undecanoic acid. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves-da-Rocha, J.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Oliveira, V.M.; Sanches, P.R.; Rossi, A.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M. Alternative Splicing in Heat Shock Protein Transcripts as a Mechanism of Cell Adaptation in Trichophyton rubrum. Cells 2019, 8, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.Z.; Li, F.; Cheng, S.T.; Xu, Y.; Deng, H.J.; Gu, D.Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, W.X.; Zhou, Y.J.; Yang, M.L.; Ren, J.H.; Zheng, L.; Huang, A.L.; Chen, J. DDX17-regulated alternative splicing that produced an oncogenic isoform of PXN-AS1 to promote HCC metastasis. Hepatology 2022, 75, 847–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Song, K. The splicing factor WBP11 mediates MCM7 intron retention to promote the malignant progression of ovarian cancer. Oncogene 2024, 43, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, M.E.R.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Sanches, P.R.; Martins, M.P.; Oliveira, V.M.; Rossi, A.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M. Alternative Splicing in Trichophyton rubrum Occurs in Efflux Pump Transcripts in Response to Antifungal Drugs. J. Fungi (Basel) 2022, 8, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Santana, L.; Petrucelli, M.F.; Sanches, P.R.; Almeida, F.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Rossi, A. The StuA Transcription Factor and Alternative Splicing Mechanisms Drive the Levels of MAPK Hog1 Transcripts in the Dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum. Mycopathologia 2024, 189, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabski, D.F.; Broseus, L.; Kumari, B.; Rekosh, D.; Hammarskjold, M.L.; Ritchie, W. Intron retention and its impact on gene expression and protein diversity: A review and a practical guide. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2021, 12, e1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.T.; Fink, G.R.; Bartel, D.P. Excised linear introns regulate growth in yeast. Nature 2019, 565, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieber, P.; Voigt, K.; Kammer, P.; Brunke, S.; Schuster, S.; Linde, J. Comparative Study on Alternative Splicing in Human Fungal Pathogens Suggests Its Involvement During Host Invasion. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjer-Hansen, P.; Weatheritt, R.J. The function of alternative splicing in the proteome: Rewiring protein interactomes to put old functions into new contexts. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2023, 30, 1844–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M.; Kiuchi, Y.; Nara, K.; Kanda, Y.; Morinobu, S.; Momose, K.; Oguchi, K.; Kamijima, K.; Higuchi, T. Identification of a novel splice variant of heat shock cognate protein 70 after chronic antidepressant treatment in rat frontal cortex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 261, 541–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).