1. Introduction

The product design industry is a high-value sector driven by style, quality, and customization. The evolving market paradigm and the progressive development of industrial processes [

1] demand solutions that actively involve customers in selecting and customizing increasingly complex products with intrinsic emotional value.

VR configurators are designed to address these needs by offering a virtual platform to enhance product awareness and provide a flexible purchasing experience. These tools allow users to naturally visualize, manipulate, and interact with complex content firsthand [

2], while also experiencing product functionalities interactively.

The spatial perception provided by VR [

3] can potentially be a game-changer in complex product configuration for those industries demanding a high level of comfort and ergonomic requirements in tight spaces, with applications spanning sectors such as automotive, interior design, camping equipment, and nautical.

Collaboration is another feature enabled by VR technologies, allowing shared and remote presence for support from professionals, sales assistants, and/or other users (e.g., relatives, partners, etc.), fostering a more dynamic and comprehensive configuration process (

Figure 1).

This approach also allows foreign customers to access an easy-to-use remote configuration tool, avoiding the cost and inconvenience of international travel while enabling a realistic preview and more confident decisions.

Moreover, the increasing demand for eco-sustainability encourages the search for low-impact remote solutions [

4] to support the competitiveness of large and heavy products (camper, boat, houses) manufactured by SMEs with limited access to logistics infrastructure and located far from major industry trade fairs.

Despite the potential of VR technology, the literature concerning the collaborative customization of design products (e.g., yachts) associated with emotional impact [

5] is limited.

Furthermore, only a few VR software solutions provide tools for multi-user configuration with photorealistic graphics. Yet, these are often prohibitively expensive and poorly optimized, restricting accessibility on lower-performance hardware. Indeed, advanced graphics are crucial for delivering a convincing product preview and an immersive and coherent environment, highlighting the need for scalable and flexible technical approaches to overcome these challenges.

In response to these limitations, we present MAGIC (Multi-user Advanced Graphic Immersive Configurator), a novel collaborative software solution (VR/Desktop) with realistic, optimized graphics for highly valuable design product configuration.

MAGIC is validated in a local shipyard, an industrial sector that still relies on non-immersive 2D visualization systems that limit customer involvement in customizing the final product. In addition, the marine industry faces challenges in assisting consumers by sharing CAD designs, often resulting in misunderstandings caused by technical inexperience and the absence of immersive visualization tools.

This research contributes to the scientific literature and promotes eco-sustainability by:

Developing MAGIC, a proprietary, standalone collaborative system with photorealistic rendering

Evaluating MAGIC in a shipyard as a real use case scenario and acquiring final user impressions.

2. Related Works

The state-of-the-art VR multi-user configuration is addressed on two levels, one in the scientific literature and the second in a commercial context.

2.1. Scientific Literature

Scientific research addresses multi-user collaboration in VR predominantly from a social perspective, emphasizing its role in design review associated with group decision-making dynamics, ultimately leading to greater efficiency in the process.

A case study in the textile sector [

6] highlights the effectiveness of VR/AR platforms in facilitating collaborative design and product customization to provide shared virtual spaces for communication among users, making processes faster. Similarly, Mixed Reality [

7] has proven valuable in multi-user prototyping by actively involving designers, ergonomists, and end users to collaborate for effective and reliable design.

In the nautical industry, a noteworthy example is BoatAR [

8], an AR-based configurator that simplifies the remote customization of boats. BoatAR reduces logistics and inventory costs while showcasing the potential of immersive technologies to address operational and economic needs. Moreover, an interesting study addresses the functional arrangement of maneuvering areas, particularly the layout of cockpit instrumentation [

9], supported by evaluations of operational, ergonomic, and anthropometric aspects.

Despite these advancements, the topic of VR solutions specifically designed for multi-user product configuration remains relatively underexplored in the literature, with eco-sustainability issues receiving limited attention. Moreover, the potential of advanced graphics in enhancing emotional impact and user engagement has not been sufficiently explored throughout the configuration process.

Challenges persist due to high hardware costs and the lack of standardized user interfaces (UI) to ensure accessibility and intuitiveness for a broad audience [

10]. Despite technological progress in VR devices, the general complexity of tools requires specialized expertise to be effectively integrated into complex workflows, such as those typical of the nautical industry [

11].

The literature research underscores the need for new collaborative approaches to configuration that integrate realistic graphics and avatar support to explore spatial perception challenges related to ergonomic aspects. In addition, further experimentation is needed for proper validation in realistic industrial scenarios.

2.2. Commercial Solutions

We conducted a Google search with Gemini artificial intelligence (AI) [

12] to identify the most significant commercial products. The query is “a list of software responding to the keywords Configuration, VR, Product Review, and Multi-user.” The results were then reviewed and filtered to narrow the search to the most relevant solutions.

Five software are found: Autodesk VRED [

13], EyeCad VR [

14], Keyshot Studio VR [

15], Mindesk [

16] and VR Sketch [

17].

A technical analysis was conducted to assess the operational focus of these applications, evaluating the following parameters:

Accessibility: Navigation method, quick-access PoV and UI user-friendliness

Configuration: Management of aesthetic and geometric variants

Object manipulation: Real-time tools for geometry modification and customization.

Interaction and Inspection: Integrated tools such as measurements, clipping planes, annotation, and screenshots.

Immersiveness: Visualization method, animations, and dynamic environmental features.

Multi-User: Technical requirements for collaborative configuration and communication.

Synchronization: VR-CAD bidirectionality.

The following is a summary of the commercial analysis:

VRED Pro (Autodesk) [

13] : Prototyping software for photorealistic scenes and collaborative reviews. It offers robust variant management and tools for inspection, such as clipping planes and measurements. However, it lacks intuitive workflows for creating configuration variants and does not support object editing in VR. Multi-user functionalities are supported, but high costs, a steep learning curve, and demanding hardware requirements limit accessibility.

Mindesk [

16] : A VR plug-in integrated with CAD software, enabling real time objects manipulation and updates with bidirectional synchronization. It features intuitive navigation but lacks collision detection. While it does not provide tools for aesthetic configuration, it supports multi-user for co-design in real time. Mindesk emphasizes technical precision over immersive rendering, enhancing CAD workflows in VR.

EyeCad VR [

14] : A standalone, user-friendly software designed for immersive presentations and design approvals. It offers intuitive navigation, aesthetic and functional configuration tools, and realistic rendering with a wide material library. It lacks multi-user collaboration but excels in interactivity, featuring dynamic scene animations and landscape contextualization.

Keyshot Studio VR [

15]: An extension of Keyshot, designed for immersive VR experiences. It provides versatile navigation and advanced configuration tools for material and geometric variants. Features include precise geometry manipulation and photorealistic rendering with ray tracing. Although it supports collaborative sessions, it requires high-performance hardware for effective use.

VR Sketch [

17]: A standalone VR application for Oculus integrated with SketchUp. Though not focused on photorealistic rendering, it enables real time CAD modeling, ergonomic evaluations with collision detection, and dynamic tools like section planes and measurements. With mid-tier hardware compatibility, VR Sketch extends CAD tools into VR, balancing flexibility and usability.

A comparative table of commercial software aligned with the scouting parameters mentioned above is presented here (

Figure 2).

VRED and Keyshot Studio VR prioritize rendering quality and collaboration but face challenges in optimizing graphical resources for mid-tier hardware. Collaboration is also costly, as clients must purchase expensive licenses to participate in remote configurations. While variants are effective and flexible, their implementation is complex and requires significant effort. Mindesk and VR Sketch provide precise interactive manipulation tools for modeling in VR and inspecting spaces with a strong technical focus. VR-CAD synchronization is also supported, enhancing workflow efficiency. However, since they are not designed for configuration, their graphical capabilities are limited. EyeCad offers a balance between immersion and ease of use, with advanced graphical settings that make scenes dynamic and engaging. However, it entirely lacks collaborative tools.

Overall, proprietary VR software for product configuration are often associated with high licensing costs, limited user participation due to demanding sharing requirements, and impractical solutions for efficient configuration.

3. Implementation

We developed MAGIC to provide proprietary and specialized software for the collaborative configuration of design products. To implement collaboration, the users are embodied with digital avatars and provided with synchronized tools. A maximum of 10 participants can simultaneously use the following interactive features (Viewer Menu, see

Figure 3 left):

Transform: Allows selecting an object or assembly prepared for mobility, dragging in 3D space, and repositioning it.

Measurement: Allows performing measurements to support space evaluation.

3D Cut Volume: Allows modeling, moving, rotating, and scaling a cutting volume to dynamically inspect cross sections of the model.

XRAY: Allows selecting objects to make them transparent, enabling inspection of hidden geometries (

Figure 3 right).

Bookmark: Allows creating quick-access points to the scene, facilitating access to key elements of the model.

User Scale: Manages the avatar scale to access an overall view of the model or move quickly through space.

Annotation: Allows creating 3D text boxes for comments and annotations.

Snapshot: Allows taking snapshots to validate the arranged configuration.

Unreal Engine 5 (UE5) is chosen for the VR implementation due to its versatility, scalability, and advanced integrated programming tools. With technologies like Nanite and Lumen, this game engine can provide high-quality visual experiences and manage complex, high-resolution geometries with dynamic lighting.

Graphical settings such as Single Pass Stereoscopic Rendering and Stereo Foveation are enabled in the project to optimize the VR experience, improving system fluidity by halving the computational load on each lens of the HMD and by focusing the maximum resolution at the center of the user’s field of view (FoV).

MAGIC is an extension of Collab Viewer, a cross-platform template provided by UE5 and designed for collaborative experiences, with excellent flexibility for integrating custom controls through Blueprint (BP) programming.

Specific BP logic is integrated to allow the configuration of aesthetic variants, supported by photorealistic materials and algorithms for simulating interior furniture components, aimed at validating the ergonomics of the yacht’s confined loft spaces.

Using a ray-cast targeting logic and activating the command with the dedicated button on the controller, the user can easily cycle through material variants (

Figure 4) and interact with the yacht’s internal and external components, without the need for an overlaying menu. This approach is chosen to prioritize the usability and simplicity of the interface.

In the scene, the user can move using the teleportation metaphor (

Figure 5 left) or quick access points (Bookmarks) to explore the model and access off-board PoV for an overview of the configured yacht. (

Figure 5 right).

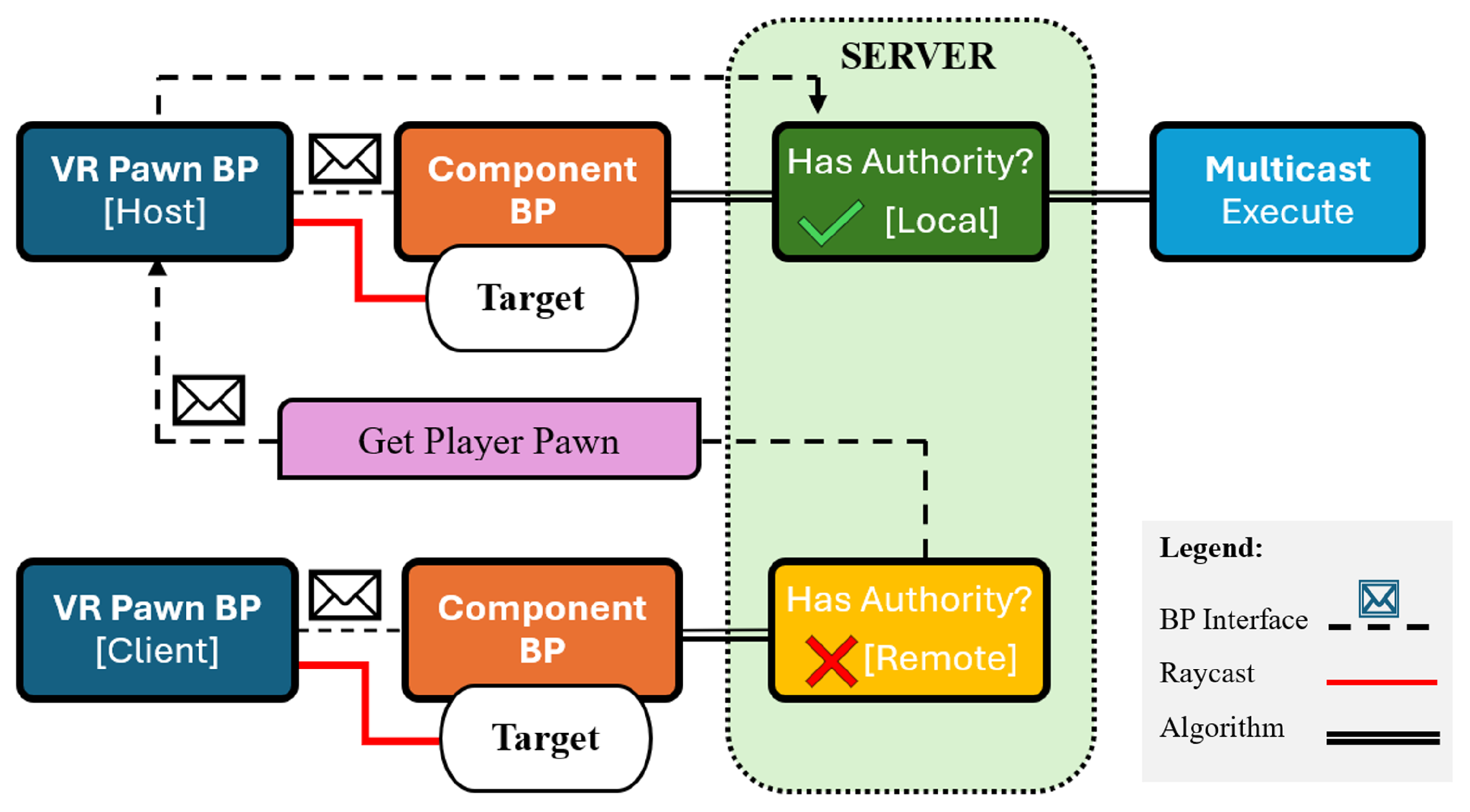

At the start of a collaborative session, the initial user (Host) enables the server, allowing participants (Clients) to access the shared scene. Each Client, equipped with their own headset and computer, can join the session remotely by connecting to a shared network (Wi-Fi or VPN).

In basic multiplayer solutions, only the Host has the authority to edit the scene on the server and share it with Clients. Although default template features are provided with appropriate programming measures, implemented functionalities (e.g., material changes, animations, etc.) require tailored multi-user logic to allow all users to actively interact with the scene during the session.

To address this, we developed dedicated algorithms for Replication and Multicast to support multi-directional synchronization between the actions of the Host and the Clients. This ensures a seamless collaborative experience with reduced latency and no constraints related to user authority.

When a command is activated, the server evaluates in real time the authority of the user who triggered the function, following two distinct logical paths (

Figure 6):

If the user is the Host, the server automatically transmits the command to all participants, and the algorithm is executed in multicast.

If the user is a Client, the remote VR Pawn is temporarily promoted to Host, receives authorization to access the server, and can then transmit the algorithm in multicast to the participants.

Immersive elements such as spatial sound effects and dynamic environmental content (e.g., wave sound, boats in motion (

Figure 7) can be added to enhance emotional engagement and the overall quality of the experience. By means of volumetric sound occlusion, the pitch of waves and motor noises is reduced when an object is positioned between the sound source and the avatar, allowing users to experience a quieter and cozier environment once inside the loft. In addition, automatic exposure is enabled in the scene to ensure a smooth and realistic transition between the yacht’s interior and exterior, where sunlight might otherwise appear overly bright or dazzling.

Lastly, users can adjust the rendering quality through a graphic management tool designed and implemented by our team to access the Game User Settings (GUS) directly from the launch menu. This feature ensures MAGIC is compatible with both current and future hardware with varying graphical capabilities.

4. Case Study: Race-Cruise Yacht Configurator

As a case study, we selected Neo Yachts&Composites [

18], an Italian shipyard specialized in high-performance carbon fiber sailing yachts since 2013. These boats are designed for recreational cruising but are also capable of racing. This represents an ideal showcase for the potential of MAGIC, as these yachts are large and difficult to transport, highly customizable in terms of aesthetics and technical elements, and require careful configuration of limited spaces.

A focus group with the company’s head and the technical and commercial staff highlighted the need for virtualization tools to reduce transportation costs and environmental impact related to trade fairs and client visits. Additionally, customers – generally non-Italian – ask for a remote configuration tool that is easy to use and avoids the time, cost, and burden of international travel. A configurator provides a more realistic idea of the result, enabling a more engaging and confident decision-making process.

Customer involvement relies on static 2D renderings and regular visits to monitor construction progress and support key decisions, often aided by disposable rapid prototypes, samples, and models. However, 2D desktop tools fail to effectively convey the perception of onboard spaces, lack ergonomic immersion, and prevent active interaction with environmental elements. For instance, the commercial team reported losing an oversized client because they could not fully demonstrate the accessibility of the final result.

Neo 430 Roma

1, an innovative full-carbon design, is chosen to showcase MAGIC’s capabilities. We imported the CAD models from Rhinoceros and modeled missing parts and components, materials, and setup. All variants available to define the aesthetic and functional aspects of the yacht’s features (e.g., hull, deck, rigging, furniture, lighting) are implemented to ensure flexibility in customization and immersive support to evaluate spaces within the cabin and on the deck.

In addition, we designed and implemented realistic and dynamic environments, such as breathtaking marine scenarios, including open seas

Figure 8, ports, and coastlines to enhance user engagement and create an emotional impact during the purchase process.

We address the following Research Questions (RQs) with a user test in a controlled setting:

RQ1: Does MAGIC ensure an adequate level of usability?

RQ2: Can MAGIC enhance sailing yacht configuration and provide realistic spatial perception?

RQ3: Do advanced graphics impact immersion and realism for the configuration process?

RQ4: Do environmental scenarios and additional content contribute to user engagement?

RQ5: Does demographic data or prior VR experience affect the system’s usability?

4.1. Participants

Participants were recruited through a social call. Thirty volunteers participated in the tests (age of 24.20±4.62, min=18, max=32), with a gender distribution of 63.3% male (19 users) and 36.7% female (11 users). The male prevalence is in line with the current preference of real clients, while the age is younger to provide insights into future customers. To create a multi-user scenario, the subjects were divided into 15 couples according to booking order, with the members of each couple not necessarily knowing each other.

4.2. Setup

The tests were conducted in a controlled environment at the VR3Lab research laboratory of the Polytechnic of Bari using Oculus Meta Quest 2 and 3 HMDs connected to two side-by-side laptops with different technical specifications:

Asus ROG with an Intel Core i7-7700HQ processor, 16GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1070 graphics card

Acer Aspire 5 with an AMD Ryzen 7 5700U processor, 16GB of RAM, and an AMD Radeon RX Vega 8 graphics card.

These two different setups allowed the feasibility and compatibility of devices with varying system specifications and operational conditions. During the collaborative session, users were co-present in the same laboratory and connected to the same Wi-Fi network.

4.3. Procedure

Before the test, users are introduced to the research topic and provided with training on the main VR commands. The participants are asked to role-play as potential customers of the Neo 430 Roma model in an interactive and consensual configuration (

Figure 9 left). The couples are connected to the same shared scene (

Figure 9 right) using two synchronized hardware systems on a server.

The users define materials, the nautical components, and interior furniture, analyze spaces using the inspection tools, and interact with dynamic elements of the scene to explore the model and assess the ergonomic suitability. The test time is 30 minutes, with a scientist monitoring users’ actions to ensure safety and assistance. Users could interrupt the test at any moment and for any reason.

4.4. Metrics

The configuration experience for each pair enabled the collection of data through the following qualitative metrics:

User Age, User Gender, User Previous VR Experience (yes/no):

SUS [

19]: Standard questionnaire for evaluating system usability

Open-ended Feedback: Evaluation of the implemented features, the level of immersion, graphical rendering, and emotional impact, including any improvement suggestions.

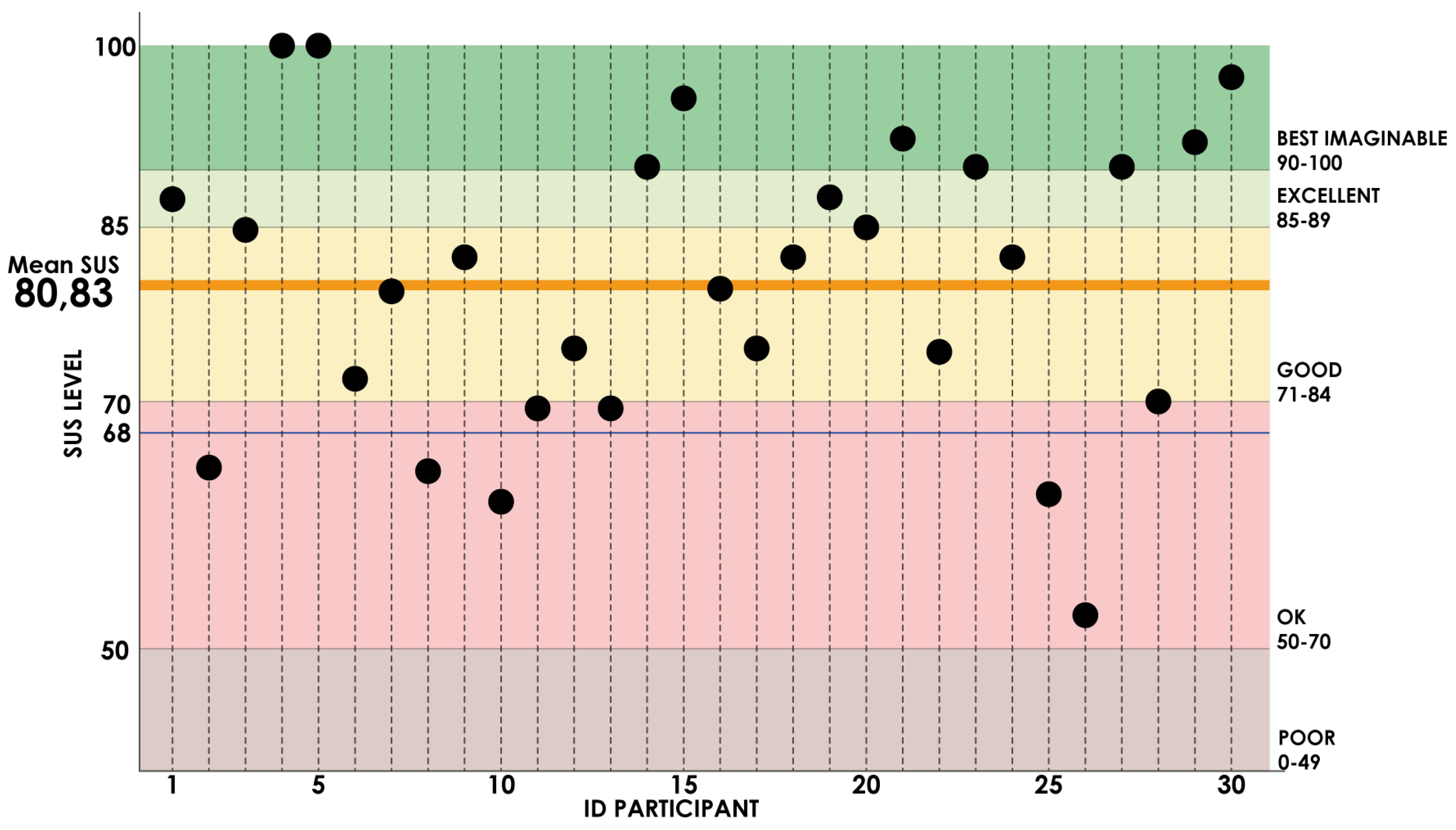

5. Results

Most of the participants (63.3%) declared having no prior experience with virtual reality, while the remaining indicated they were familiar with VR (36.7%).

5.2. User Feedback

User feedback (detailed in the appendix, see

Table A1) gives us a deeper understanding of the system’s strengths and weaknesses and highlights key areas for improvement.

Graphics and immersion are among the most appreciated aspects, with users emphasizing the high level of detail contributing to the experience. One participant remarked: “The graphics exceeded my expectations… it is an excellent way to customize and imagine your boat before purchasing it". Many users felt they were truly aboard the yacht, thanks to the high-quality visuals of objects and materials. One participant noted: “The integrated details were so well done, it felt like I was actually inside a yacht…”. However, some users suggested improving material reflections and expanding the environment to make it more engaging (e.g., a nearby island).

The ability to interact with, customize, and move objects in real time was widely praised for being intuitive, making the experience practical and independent. Another participant stated: “I particularly liked interacting with the objects and making changes on my own, without needing someone else’s help.” However, users desired a wider variety of materials, colors, and textures with more realistic and practical options.

Although the controls were generally intuitive, 7 out of 30 participants expressed a desire for greater freedom of movement and alternatives to teleportation, which was often inaccurate or challenging in tight spaces. Additionally, selecting smaller objects remotely with ray-cast was challenging. Also, some right-handed users found the placement of the configuration controls on the left controller uncomfortable.

Other suggestions for improvement include a more precise locomotion system, clearer training, and haptic feedback to indicate an avatar-object collision. 2 out of 30 participants also reported physical fatigue and dizziness caused by the headset weight and occasional lag.

6. Discussion

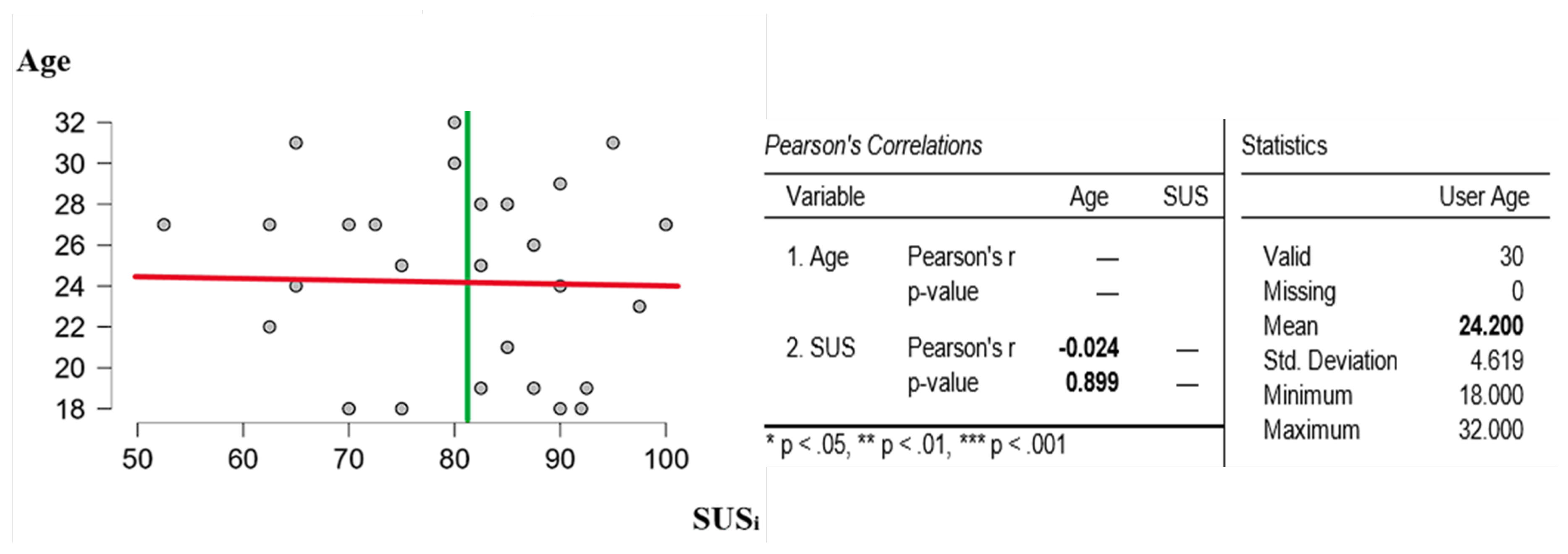

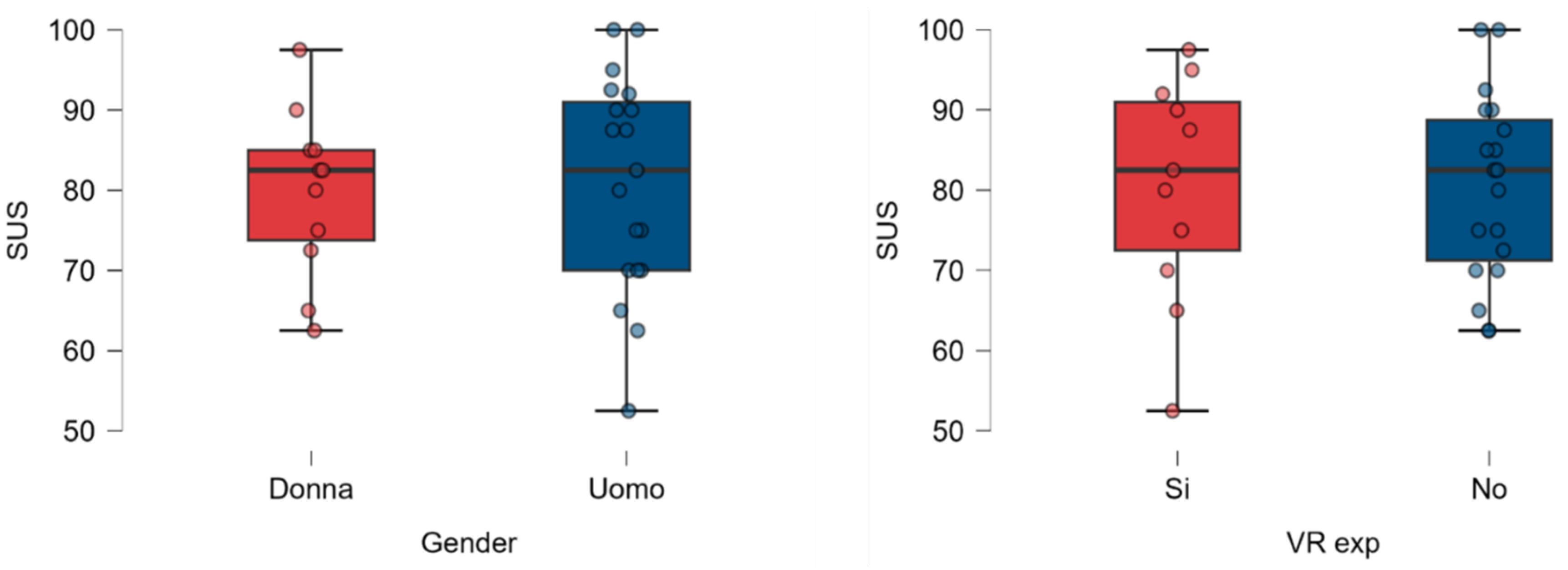

The test provides significant results regarding the usability of MAGIC. In addition, to further investigate the distribution of individual SUS scores, potential correlations are analyzed to provide a comprehensive examination of their relationship with sample parameters such as age, gender, and prior experience with VR devices.

No significant correlation is found between users’ demographic data and the distribution of usability scores, which appear largely random, thus ruling out a functional dependency between these two parameters (

Figure 11).

The slope (r = -0.024) of the regression line indicates a weak, negative correlation, showing that as participants’ age increases, the SUS score tends to decrease slightly.

However, since the p-value=0.899 >> *p (< 0.05), it can be concluded that this correlation does not hold statistical significance.

Similarly, the correlation between gender and SUS scores is negligible (

Figure 12 left), with a percentage difference of 1.38% between the average values assigned by each category. However, male participants’ scores exhibit greater deviation.

Regarding VR familiarity (

Figure 12 right), experienced users provided scores within a broader range compared to non-experienced participants, even though the average results are remarkably similar (percentage difference < 0.3%). This might indicate that experienced users conducted more technical and informed evaluations, while non-experienced participants offered valuable insights into the system’s impact on end-users without specific expertise.

The feedback indicates that the experience was generally perceived as immersive, engaging, and well-executed, with a graphical and interactive system that exceeded users’ expectations. However, targeted improvements in customization, navigation, and technical optimization could address the issues that emerged, making the overall experience even smoother and more satisfying. With a greater variety of options, a more intuitive control system, and a more dynamic environmental context, this application could reach an even higher level.

Following the results analysis, it is possible to attempt to answer the RQs:

RQ1: Supported – MAGIC’s usability falls within the "acceptable" range on the SUS metric.

RQ2: Partially supported – MAGIC is feasible for sailing yacht configuration, but improvements in navigation and collision systems are required for effective space evaluation.

RQ3: Supported – Photorealistic graphics are essential for a convincing digital preview.

RQ4: Supported – Additional content significantly enhances the experience.

RQ5: Not supported - Demographic data or VR experience does not significantly affect the SUS score, but further investigation with a wider sample is needed.

7. Limitations and Future Works

The tests revealed several limitations but also opportunities for improvement that could guide more targeted and informed future development. The user sample has a relatively young average age, highlighting the need for expansion along with a greater gender balance. Additionally, pair relationships could be further investigated as an alternative to the current semi-random couple generation approach.

The current teleportation and exploration methods may not fully accommodate all users. A controller-based locomotion system offers a potential solution, but its implementation must carefully mitigate the risk of motion sickness. Additionally, introducing a parametric avatar tailored to the user’s height and body type could enhance spatial perception, creating a more natural and immersive experience.

An interesting perspective is the integration of shared Co-Design tools, which introduce a virtual space where clients and designers can collaborate in real time to create customized solutions beyond pre-configured options. Users would actively participate in designing interior layouts and structural components, making the process more interactive and engaging. However, achieving this will require overcoming technical challenges, such as synchronizing the VR environment with CAD files and managing objects within the scene.

With these developments, MAGIC could evolve into an even more flexible and powerful tool capable of meeting the technical needs of designers and the expectations of end users.

8. Conclusion

This study examines the applicability of Industry 4.0 technologies in complex product configurations. Despite growing interest, only a few studies and commercial products have investigated multi-user tools for remote configuration purposes. Moreover, the potential of advanced graphics to enhance emotional engagement remains relatively unexplored, while existing software solutions often lack optimization and affordability.

To overcome these limitations, we developed MAGIC, a multi-user VR standalone prototype, leveraging the advanced graphical and programming capabilities of UE5.

As a case study, MAGIC was applied to the sailing yacht sector to contribute to recreational boating by providing a VR solution aligned with the needs of Neo Yachts, offering collaborative functionalities, immersive graphics, and virtual support for spatial evaluation. The project also integrated eco-sustainable and social aspects through the dematerialization of concepts and supporting the competitiveness of the manufacturing sector.

Validation confirmed the software’s high usability, with a SUS score of 80.83, above the acceptable threshold. User feedback highlighted strengths and areas for improvement, providing valuable insights to further enhance the configuration experience.

The research demonstrated the feasibility of VR for realistic yacht configuration, though challenges with navigation methods and spatial perception remain to be further investigated. Despite this, VR technology is not yet mature enough to effectively integrate into industrial and design processes. However, as innovation progresses, these tools will become increasingly relevant, accessible, and high-performing.

As a final remark, MAGIC provides a foundation for future research projects in other industrial fields, with promising positive economic, commercial, and environmental impacts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paolo Semeraro and NeoYacth Srl. staff for the technical and practical support of this project design and experiments.

Appendix A. User Feedback

The supplementary material includes feedback from each participant (). As four participants did not provide relevant comments, only 26 out of 30 are listed below.

Table A1.

Participant feedback summary with positive comments and suggestions for improvement.

Table A1.

Participant feedback summary with positive comments and suggestions for improvement.

| Participant |

Positive Comments |

Suggestions for Improvement |

| P1 |

Graphics and interaction with objects were good. |

Preferred more materials for customization. |

| P2 |

Realism, navigation, and details were interesting. |

Teleportation issues; add land/island context; enhance sail textures. |

| P3 |

The scene felt real and well-designed. |

Desired better interaction with the environment. |

| P4 |

Liked object interaction and independence. |

- |

| P5 |

Intuitive, immersive experience. |

Difficult selecting smaller objects from a distance. |

| P6 |

Object representation enhanced configuration. |

Suggested boat motion for added interest. |

| P7 |

Interaction and fluid animations were appreciated. |

Reflections seemed unrealistic. |

| P8 |

Graphics suited product design. |

Pointing system could be more precise. |

| P9 |

Immersive for VR beginners. |

Teleportation sometimes failed. |

| P10 |

Graphics exceeded expectations. |

Experienced fatigue and dizziness. |

| P11 |

Enjoyed interactive elements. |

Moving often resulted in passing through boat walls. |

| P12 |

Positive interaction with elements. |

Unsatisfactory color range; a suggested interface for selecting shades. |

| P13 |

Integrated details felt realistic. |

Suggested haptic feedback, collision script, and addressing lag. |

| P14 |

System was engaging and responsive. |

Left-handed controls were challenging for right-handed users. |

| P15 |

Appreciated customization and intuitiveness. |

Teleportation often triggered the menu accidentally. |

| P16 |

Felt like objective reality and easy to use. |

Suggested a greater variety of colors. |

| P17 |

Highly realistic immersion; useful for decision-making. |

Suggested a command guide for better function understanding. |

| P18 |

Simple main controls made the experience enjoyable. |

Desired more freedom of movement inside the boat. |

| P19 |

Optimized interface; provided 360-degree view. |

- |

| P20 |

Fantastic, lifelike experience. |

- |

| P21 |

Enjoyed opening doors, picking objects, and free movement. |

- |

| P22 |

Excellent movement fluidity and realistic images. |

Teleportation issues were noted. |

| P23 |

High-quality graphical rendering in an immersive environment. |

Interaction was complex and needed simplification. |

| P24 |

Realistic setting with simple controls. |

Menu occasionally closed unexpectedly. |

| P25 |

Liked real time product change observation. |

not satisfied by limited fluidity in movement. |

| P26 |

Realistic textures and animations. |

Teleportation sometimes worked poorly. |

References

- Pantano, E. Innovation drivers in retail industry. International Journal of Information Management 2014, 34, 344–350. [CrossRef]

- Kan, H.; Duffy, V.G.; Su, C.J. An Internet virtual reality collaborative environment for effective product design. Computers in Industry 2001, 45, 197–213. [CrossRef]

- Azarby, S.; Rice, A. Understanding the Effects of Virtual Reality System Usage on Spatial Perception: The Potential Impacts of Immersive Virtual Reality on Spatial Design Decisions. Sustainability 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Scurati, G.W.; Bertoni, M.; Graziosi, S.; Ferrise, F. Exploring the Use of Virtual Reality to Support Environmentally Sustainable Behavior: A Framework to Design Experiences. Sustainability 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Diemer, J.; Alpers, G.W.; Peperkorn, H.M.; Shiban, Y.; Mühlberger, A. The impact of perception and presence on emotional reactions: a review of research in virtual reality. Frontiers in Psychology 2015, 6. [CrossRef]

- Smparounis, K.; Mavrikios, D.; Pappas, M.; Xanthakis, V.; Viganò, G.P.; Pentenrieder, K. A virtual and augmented reality approach to collaborative product design and demonstration. 2008 IEEE International Technology Management Conference (ICE) 2008, pp. 1–8, [https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:26058925].

- Wang, L.; Yoon, K.J. CoAug-MR: An MR-based Interactive Office Workstation Design System via Augmented Multi-Person Collaboration, 2020, [arXiv:cs.HC/1907.03107]. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1907.03107.

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, S.; Fu, W.T. BoatAR: a multi-user augmented-reality platform for boat. Proceedings of the 24th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Favi, C.; Moroni, F.; Manieri, S.; Germani, M.; Marconi, M. Virtual reality-enhanced configuration design of customized workplaces: A case study of ship bridge system. Computer-Aided Design and Applications 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ververidis, D.; Nikolopoulos, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. A review of collaborative virtual reality systems for the architecture, engineering, and construction industry. Architecture 2022, 2, 476–496. [CrossRef]

- Cassar, C.; Simpson, R.; Bradbeer, N.; Thomas, G. Integrating virtual reality software into the early stages of ship design. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Computer Applications in Shipbuilding ICCAS, The Royal Institution of Naval Architects, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2019, pp. 24–25.

- Google. GEMINI, [https://gemini.google.com]. Accessed: 2024-09-01.

- Autodesk. Vred, [https://www.autodesk.com/it/products/vred/overview]. Accessed: 2024-09-01.

- Autodesk. Eyecad VR, [https://eyecadvr.com]. Accessed: 2024-09-01.

- KeyShot. Keyshot VR, [https://www.keyshot.com]. Accessed: 2024-09-01.

- KeyShot. Mindesk, [https://mindeskvr.com]. Accessed: 2024-09-01.

- VRSketch. VRSketch, [https://vrsketch.eu]. Accessed: 2024-09-01.

- Neo yachts and composites. Neo yachts and composites, [https://neoyachts.com/]. Accessed: 2024-09-01.

- Bangor, A.; Kortum, P.T.; Miller, J.T. Determining what individual SUS scores mean: adding an adjective rating scale. Journal of Usability Studies archive 2009, 4, 114–123, [https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:7812093].

Figure 1.

Multi-user VR configuration of a highly customizable yacht using MAGIC in a three-person shared session: Yellow and Red users evaluate the optimal distance between the helms (left), while the Blue user observes the deck from the hatchway (right).

Figure 1.

Multi-user VR configuration of a highly customizable yacht using MAGIC in a three-person shared session: Yellow and Red users evaluate the optimal distance between the helms (left), while the Blue user observes the deck from the hatchway (right).

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of features and functionalities across selected commercial VR platforms.

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of features and functionalities across selected commercial VR platforms.

Figure 3.

3D menu widget for collaborative and inspection tools (left); Example of XRAY application in the yacht loft (right).

Figure 3.

3D menu widget for collaborative and inspection tools (left); Example of XRAY application in the yacht loft (right).

Figure 4.

Material variant permutation example in real time: from striped marine fabric (left) to petrol leather (right).

Figure 4.

Material variant permutation example in real time: from striped marine fabric (left) to petrol leather (right).

Figure 5.

Teleport ray cast (left), position Bookmarks (right) for quick access to key locations (e.g. off-board tender view)

Figure 5.

Teleport ray cast (left), position Bookmarks (right) for quick access to key locations (e.g. off-board tender view)

Figure 6.

Multi-user authoring management algorithm path.

Figure 6.

Multi-user authoring management algorithm path.

Figure 7.

Environmental and narrative content: moving trawler with spherical engine noise (left); Cargo ship in the background (right).

Figure 7.

Environmental and narrative content: moving trawler with spherical engine noise (left); Cargo ship in the background (right).

Figure 8.

Photorealistic dynamic environment provided by MAGIC in runtime: showcasing a photorealistic yacht view from afar (left) and an immersive onboard perspective toward a vibrant sunset (right).

Figure 8.

Photorealistic dynamic environment provided by MAGIC in runtime: showcasing a photorealistic yacht view from afar (left) and an immersive onboard perspective toward a vibrant sunset (right).

Figure 9.

Double setup paired test (left image), collaborator visualization in the shared scene; the field of view of the female participant (right image).

Figure 9.

Double setup paired test (left image), collaborator visualization in the shared scene; the field of view of the female participant (right image).

Figure 10.

Distribution of individual SUS scores, indicating the SUS mean (orange line), the “Acceptable threshold” =68 (blue line), and the range covered by the scores (min=52.2, max=100).

Figure 10.

Distribution of individual SUS scores, indicating the SUS mean (orange line), the “Acceptable threshold” =68 (blue line), and the range covered by the scores (min=52.2, max=100).

Figure 11.

SUS-Age Correlation diagram with a negative slope (r = -0.024) (Regression line shown in red, and the SUS mean=80,82 marked in green).

Figure 11.

SUS-Age Correlation diagram with a negative slope (r = -0.024) (Regression line shown in red, and the SUS mean=80,82 marked in green).

Figure 12.

Distribution of SUS scores based on user gender (left image) and prior experience with virtual reality (right image).

Figure 12.

Distribution of SUS scores based on user gender (left image) and prior experience with virtual reality (right image).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).