1. Introduction

Wound healing is an intricate process with interactions among various cells, extracellular compositions, and structures[

1]. Different types of wounds require different care needs, such as accelerating wound healing, preventing pathogen infections, decreasing pain, and avoiding excessive tissue fluid leakage from the wound. Although medications have been combined with dressings for wound care for many years, these medications often have side effects[

2]. Therefore, developing novel wound-healing agents from natural sources has become a popular focus in recent years.

Marine algae are an unexploited reservoir of biologically active substances due to their abundant biodiversity[

3]. However, their chemical constituents and bioactivities are still rarely studied, but would provide high potential for further research. Recent studies demonstrated that extracts from algae provide specific biological functions such as antioxidation[

4], antimicrobial properties[

5], and antiviral abilities[

6], and could be helpful for issues such as high blood pressure[

7], obesity problems[

8], cardiac diseases[

9], and specific cancers[

10]. These biofunctions may arise from various types of bioactive molecules, such as proteins, compounds, polysaccharides, and peptides[

11,

12]. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate the functions and health benefits of different crude extracts within specific disease models, with the ultimate goal of isolating a purified bioactive molecule in alga-related research.

When applying marine algae for wound healing, most studies focused on fabricating wet wound dressings using algal polysaccharides[

13,

14], which form the structure of dressing materials and provide a surface for cell adhesion or attachment to promote wound healing. In addition, bioactive compounds from marine algae also participate in the wound-healing process and skin tissue regeneration by regulating transduction of related signals[

15]. Given the high potential for the use of marine algae to promote wound healing, a number of ongoing studies are attempting to identify and isolate ideal materials for wound healing, especially through various types and rare seaweeds as research targets.

Botryocladia leptopoda is a kind of marine red alga that has been used as feed, fertilizer, and in food manufacturing at an industrial level[

16]. Due to limited research on medical applications of

B. leptopoda, in this study, we obtained various extracts of

B. leptopoda to investigate their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Finally, cell-based experiments were conducted to assess the cytotoxicity, cell adhesion, and cell proliferation for evaluating their potential for wound-care applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

RAW 264.7 macrophage and L929 fibroblast cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). EDTA, trypsin, and antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin) were obtained from GE Healthcare Life Science (Logan, UT, USA). Vivaspin 15R and Vivaspin Turbo 15 were obtained from Sartorius Stedim Biotech (Goettingen, Germany). Cell culture media (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), supplemented with high glucose, phenol red, sodium pyruvate, and L-glutamine) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were procured from Hyclone Laboratories (Logan, UT, USA). All chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade and purchased from Merck (Burlington, MA, USA). The Cell Proliferation ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) BrdU kit was purchased from Roche Applied Science (Mannheim, Germany).

2.2. Extraction of B. leptopoda

Raw material of B. leptopoda was obtained from the Eastern Marine Fishery Research Center of the Ministry of Agriculture (Taitung, Taiwan). After being thoroughly washed, the alga was dried and pulverized. B. leptopoda powder was then extracted at 25 °C using sodium hydroxide (alkaline extract, AE), at 25 °C using ethanol (FE extract), at 70 °C using ethanol (HE extract), and at 100 °C using deionization and distilled (dd)H2O (HW extract).

2.3. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

The TPC was used according to a method described by Pérez, et al. [

17] with slight modification: 0.25 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was mixed with 0.25 mL of an extract (volume ratio of 1:1), and the mixture was thoroughly mixed for 3 min at room temperature. Fifty milliliters of a 20% Na

2CO

3 solution was slowly added and incubated at 40 °C for 20 min. The absorbance of the mixture was determined at 755 nm. The TPC was calculated using a gallic acid standard curve, and results are expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per milliliter (mg GAE/mL).

2.4. Antioxidation Ability

Different concentrations of extracts (2, 5 and 10 mg/mL) were prepared using 80% methanol, and were shaken and abstracted at 150 rpm and 25 °C for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 8000 ×g and 4 °C for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected and used in the following experiment. L-Ascorbic acid (2, 5, and 10 mg/mL) was used as the positive control in the antioxidation ability assays.

In the diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical-scavenging activity assay[

18], 0.1 mM methanolic DPPH as a reaction solution was mixed with an extract (volume ratio of 1:1) at 25 °C in the dark for 30 min, and the absorbance value at 517 nm was measured. Results were expressed as the scavenging activity (%) using Eq. (1):

where Anc, Asample, and Ablank are the absorbance at 517 nm for the negative control (0.1 mM methanolic DPPH, without the addition of sample), sample (0.1 mM methanolic DPPH, with the addition of extract at a specific concentration), and blank (sample with ddH2O), respectively. Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethyl chroman-2-carboxylic acid) was used as the standard antioxidant for the assay.

In the ferrous ion-chelating activity (FICA) assay[

19], 1 mL of extract was mixed with 0.1 mL of a 2 mM FeCl

2 solution for 30 s, and reacted with 0.2 mL of 5 mM ferrous hydrazine at room temperature for 10 min. The absorbance value at 562 nm was measured. Results are expressed as ferrous ion-chelating activity (%) using Eq. (2):

where A

nc, A

sample, and A

blank are the absorbance at 562 nm for the negative control (2 mM FeCl

2 solution, with ddH

2O), sample (2 mM FeCl

2 solution, with the addition of extract at specific concentration), and blank (sample with ddH

2O). respectively.

2.5. Detection of Anti-Inflammatory Ability

To confirm the ability of inflammatory inhibition by B. leptopod extracts, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated RAW 264.7 macrophages were used as the detection cell model. A 96-well plate coated with capture antibodies of interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α was washed with washing buffer, and 1× assay diluent (200 μL/well) was added at room temperature for 1 h. The assay diluent, extracts (62.5, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 µg/mL), and RAW 264.7 macrophage cells (106 cells/mL) with or without LPS treatment (1 µg/mL) were mixed at room temperature for 1 h. After washing buffer treatment, avidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (100 μL/well) was added, and incubated for 30 min. After washing buffer treatment, the 3,3,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (100 μL/well) was added and incubated for 15 min in a dark room. The reaction was stopped by adding a stop solution (50 μL/well), and the OD value at 450 nm was detected.

2.6. Cell Cytotoxicity, Proliferation, and Migration

For the cell cytotoxicity assay, L929 fibroblast cells were cultured in 90% DMEM and 10% FBS for 3 days in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 airflow. L929 fibroblasts at a concentration of 106 cell/mL were plated in a 96-well plate with culture medium containing different concentrations of B. leptopoda extracts for 4 h of incubation. Treated cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then 120 μL of 10-fold diluted MTS reagent was added to each well. Cells were left for 1 h in an incubator at 37 °C in the dark. The number of viable cells was measured at a wavelength of 490 nm. The diluted MTS reagent was used as a blank, and wells containing cells without extract addition were used as a negative control. Cell viability was calculated by comparing absorbance values of treated groups to that of the control group, which was set to 100%.

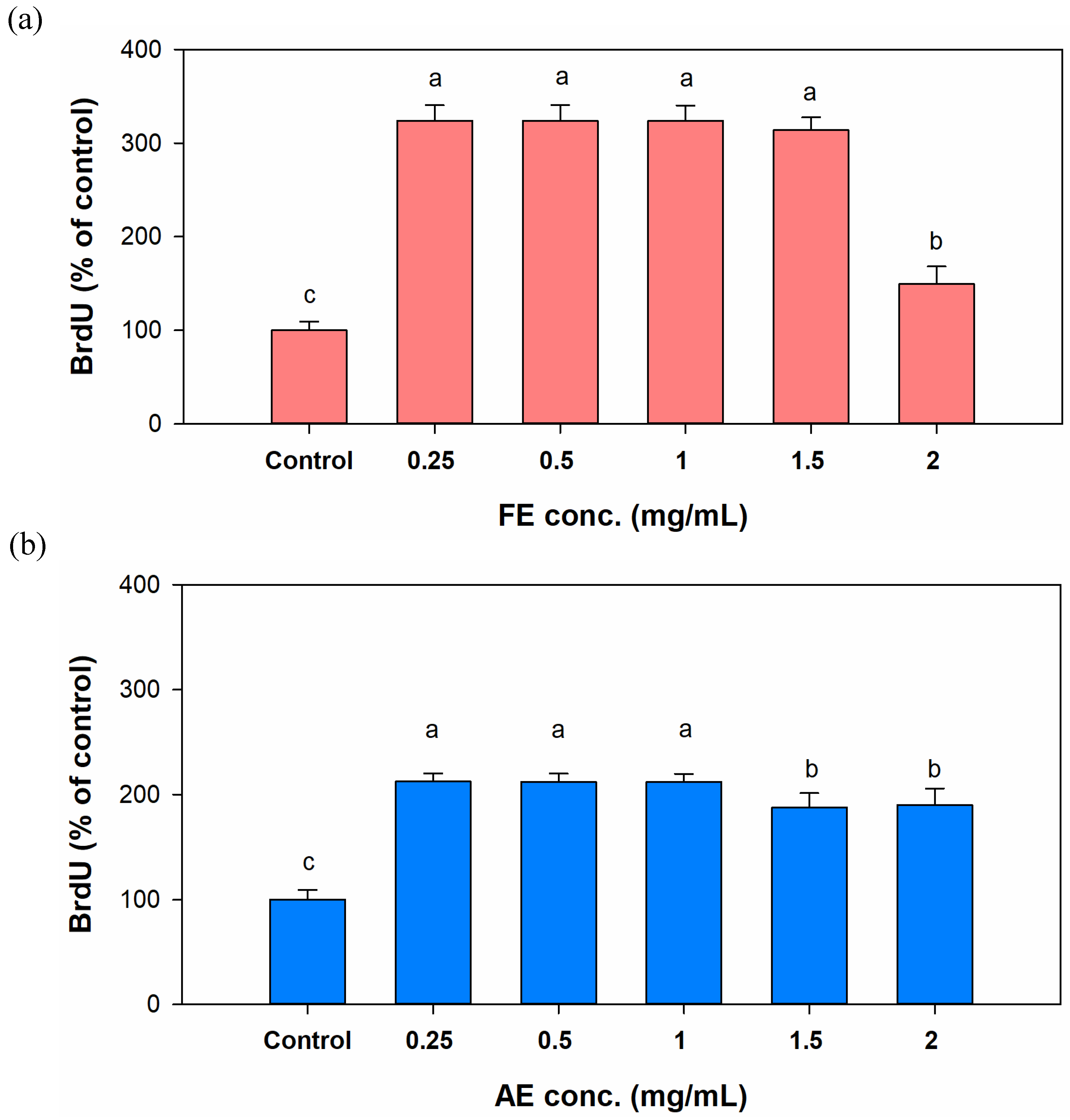

In the cell proliferation assay, L929 fibroblasts at a concentration of 2×105 cells/mL were plated in a 96-well plate with culture medium containing different concentrations of B. leptopoda extracts for 24 h of incubation and mixed with a BrdU solution (10 μL/well, 10 μM) for 4 h at 37 °C. After the medium was removed, cells were fixed and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. A solution of a BrdU antibody conjugated with peroxidase was added (100 μL/well) for 90 min of treatment. Wells were washed with washing solution (200 μL/well), and a substrate solution (100 μL/well) was added. The absorbance was monitored at 370 nm. The proliferation ability was calculated by comparing absorbance values of treated groups to that of the control group, which was set to 100%.

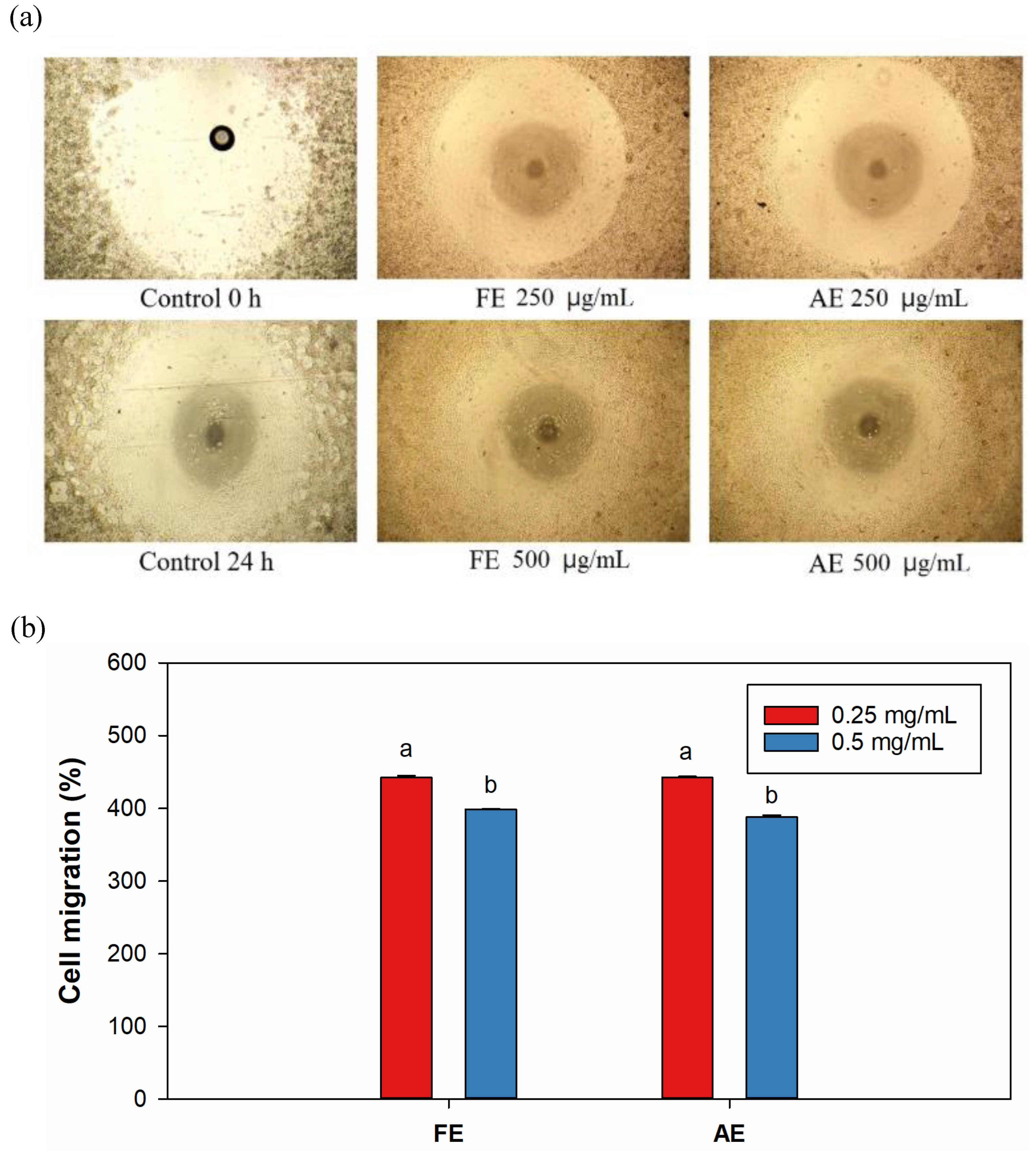

In the cell-migration assay, L929 cells were inoculated in a culture dish with a central void and incubated until 80%~90% cell confluency was reached. Cells migrated directly from the surroundings into the central void, and cell fragments were cleaned with PBS. Different concentrations of extracts were added to the serum-free medium. The central void was measured under an inverted microscope at 24 h. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to calculate the area of the void area, and the migration rate was calculated using Eq. (3):

where A

0 and A

24 are areas of the void area at 0 and 24 h, respectively, after treatment with the extract.

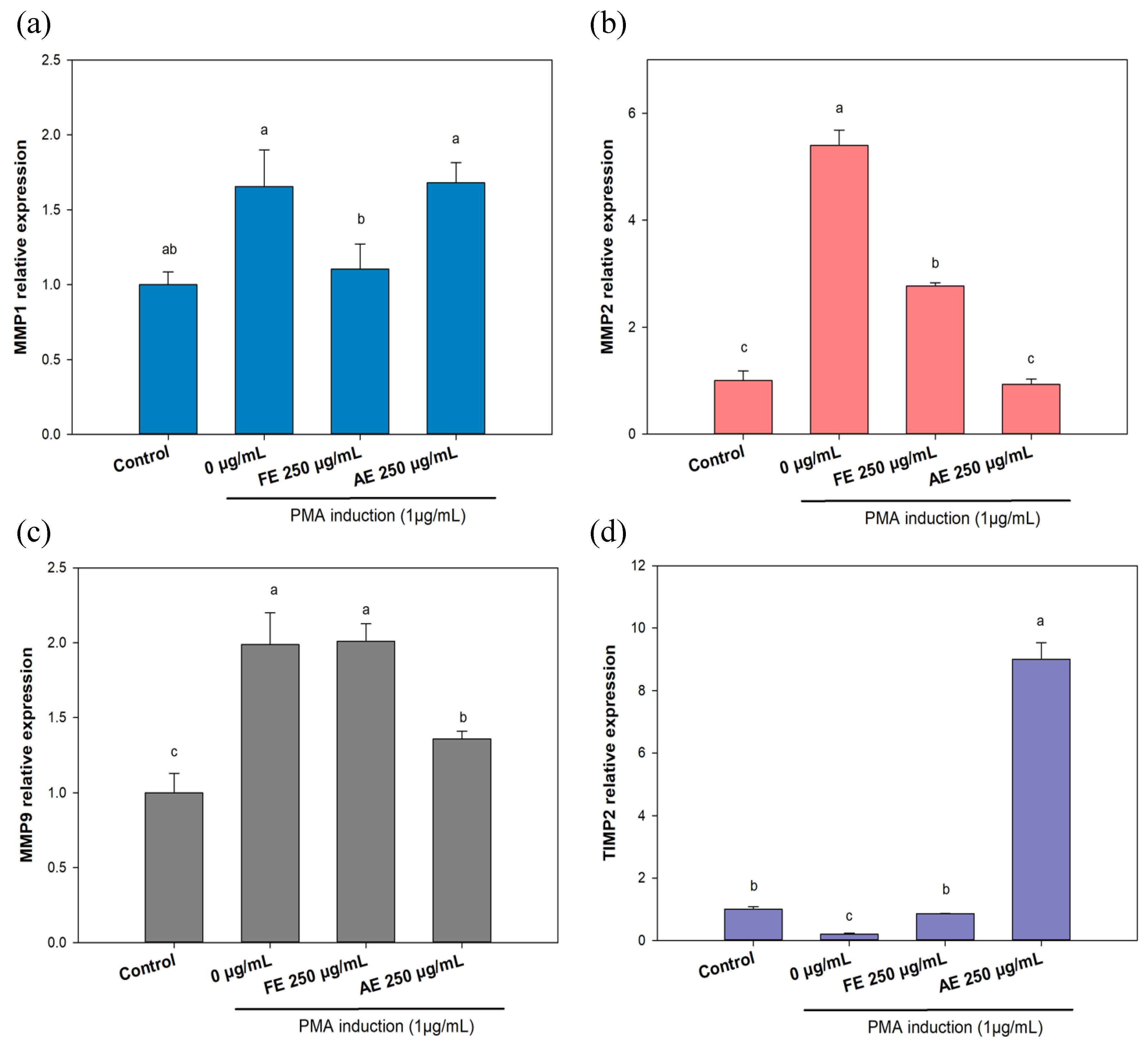

2.1. Scar Inhibition in a Cell-Based Experiment

To detect the anti-scarring effects of different B. leptopoda extracts, messenger (m)RNA expressions of genes including matrix metalloproteinase genes (MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-9) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP-2) were investigated. L929 cells (6×105 cell/mL) were seeded inT25 flasks for 4 h. Medium with extract was added and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (1 μg/mL) was also added to the medium before incubation to induce MMP-related gene activation.

Total RNA extracted from cell samples was converted to complementary (c)DNA using an iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). A reverse-transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis was carried out using iScript RT-qPCR Sample Preparation Reagent (Bio-Rad).

The qPCR conditions were 2 min at 50 °C and then 10 min at 95 °C. Afterward, conditions were set to 40 cycles of 15 s in which the temperature was kept at 95 °C and subsequently dropped to 60 °C for 60 s. The qPCR analysis involved the use of specific forward (F) and reverse (R) primers, namely MMP-1 RNA-F (5′-GCTAACCTTTGATGCTATAACTACGA-3′) and MMP-1 RNA-R (5′-TTTGTGCGCATGTAGAATCTG-3′) for the MMP-1 RNA gene, MMP-9 RNA-F (5′-CCAGCCAGTCTGATTTGATG-3′) and MMP-9 RNA-R (5′-TCCAGTACCAAGACAAAGC-3′) for the MMP-9 RNA gene, MMP-2 RNA-F (5′-ATCGCAGACTCCTGGAATG-3′) and MMP-2 RNA-R (5′-CCAGCCAGTCTGATTTGATG-3′) for the MMP-2 RNA gene, and TIMP-2 RNA-F (5′-GGTAGCCTGTGAATGTTCCT-3′) and TIMP-2 RNA-R (5′-ACGAAAATGCCCTCAGAAG-3′) for the TIMP-2 gene. Expression levels were standardized to those of the housekeeping gene, GAPDH RNA-F (5′-TGTTGCCATCAATGACCCCTT -3′) and GAPDH RNA-R (5′-CTCCACGACGTACTCAGCG-3′) for the mouse GAPDH gene. Calculation formulas were as follows: ΔCT=CT (target gene) - CT (reference gene). ΔΔCT=ΔCt (control target gene) - ΔCt (treatment target gene). Relative expression of gene=2ΔΔCT.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were independently repeated at least three times, and the obtained data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical data analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test was applied to determine significant differences (p<0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. TPC and Antioxidant Capacity of B. leptopoda Extracts

In the past, many plants have been used for wound care and were later found to be rich in polyphenolic compounds[

20]. These polyphenols exhibit strong anti-inflammatory effects[

21], reduce oxidative stress[

22], promote collagen regeneration[

23], enhance re-epithelialization[

24], and effectively accelerate wound healing[

25]. Therefore, analyzing the TPC can aid in evaluating the potential of extracts from

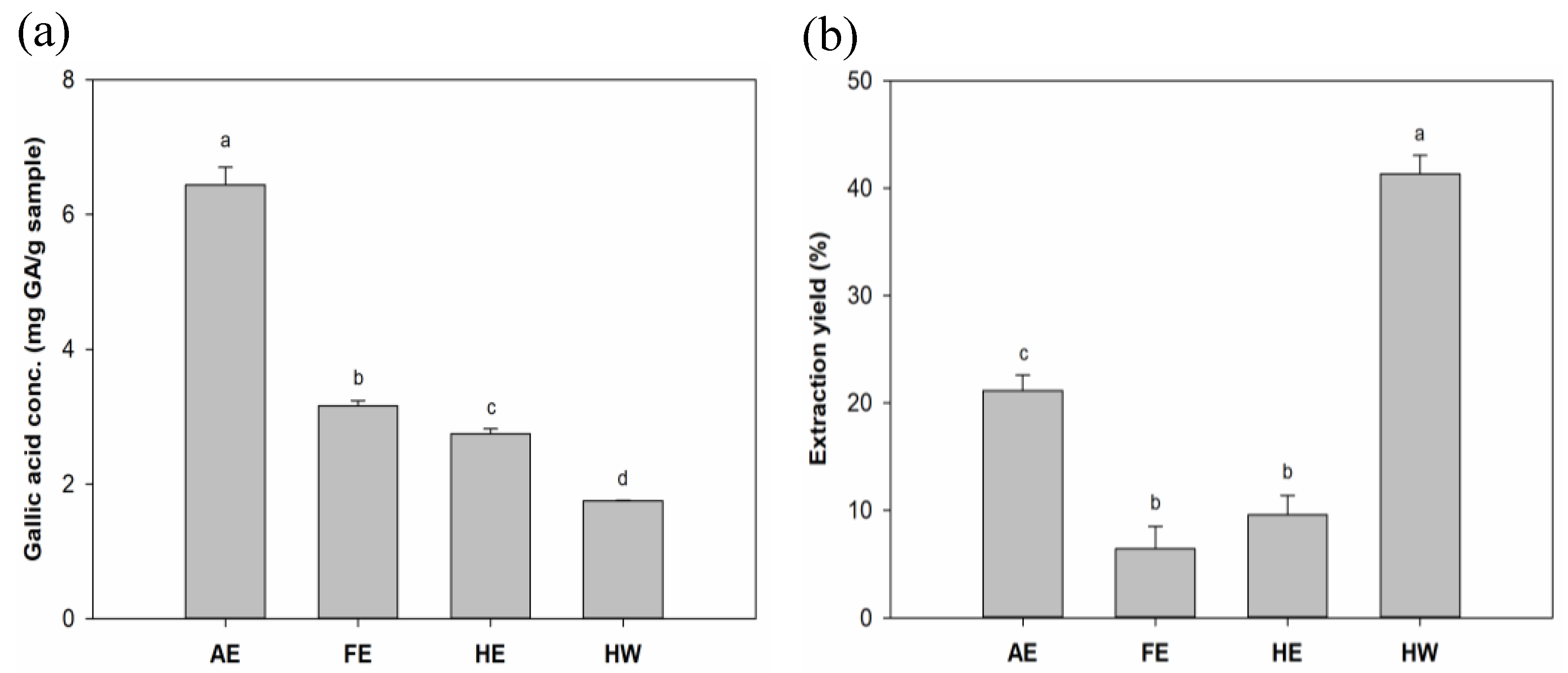

B. leptopoda as wound-care agents. Results (

Figure 1a) indicated that phenolic compounds from

B. leptopoda extracts were much more soluble in alkaline solvents than in water or weak polar organic solvents. The AE presented the highest TPC content of 6.44 mg GA/g, compared to FE, HE, and HW (at 3.16, 2.75, and 1.75 mg/GA/g, respectively). Sun

, et al. [

26] compared water, acidic, and alkaline solvent extracts and found the highest bioactive components were achieved in an alkaline environment. This may have been due to alkaline extraction helping break down algal cell walls composed of cellulose leading to release of components out of the algae. Results from Peasura

, et al. [

27] also showed a similar trend of alkaline extraction yielding higher sulfated polysaccharides compared to water and acidic extraction, which provided higher antioxidation abilities.

In results of the extraction efficiency (

Figure 1b), the HW group showed the highest yield, reaching 41.32%. Concentrations in descending order were the AE group (21.15%), HE group (9.57%), and FE group (6.43%). Harb

, et al. [

28] found that water extraction showed 3–13-fold higher yields compared to methanolic extraction, which was similar to our results. Owing to high polysaccharide contents in algae, the water extraction method was used to facilitate polysaccharide extraction, which may explain the results.

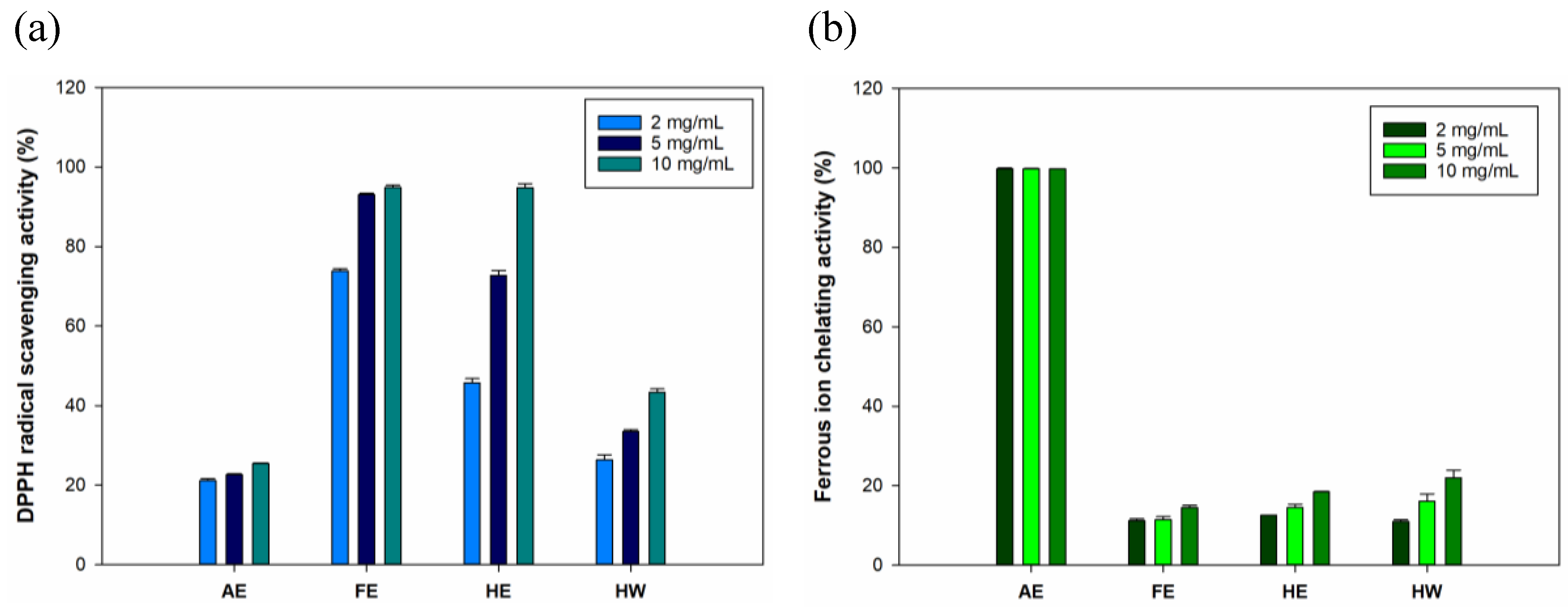

Free radical-scavenging properties were proven to promote wound-healing processes[

29]. Therefore, evaluating the antioxidative abilities is crucial for biological ingredients applied to wound care, especially specific wounds such as diabetic wounds[

30]. Results for DPPH (

Figure 2a) showed that both the FE and HE groups exhibited strong antioxidation at 73.8%~94.8% and 45.7%~94.7%, respectively. These results suggested that the FE and HE samples contained significantly higher amounts of lipophilic antioxidants due to extraction with ethanol. In the AE and HW groups, hydrophilic solvents proved inadequate to extract lipophilic antioxidants, thereby resulting in reduced DPPH radical-scavenging activities (of 21.1%~25.4% and 26.3%~43.3%, respectively). In the results of ferrous iron-chelating activity (

Figure 2b), the AE group exhibited the highest ferrous iron-chelating capacity compared to the other groups. Interestingly, the iron-chelating activity followed a trend similar to that observed for TPC. This suggested that phenolic compounds in the AE may contributed to its high metal-chelating capacity. Previous studies showed that specific polyphenols derived from seaweeds possess ferrous iron-chelating properties[

31,

32]. Although the AE group demonstrated saturated ferrous iron-chelating activity, this finding confirmed its strong antioxidant potential. Subsequent experiments further assessed its wound-healing efficacy using different extract doses in cellular assays. Based on the potential of AE and FE in demonstrating antioxidant properties, these two groups were selected as the primary experimental groups for subsequent experiments.

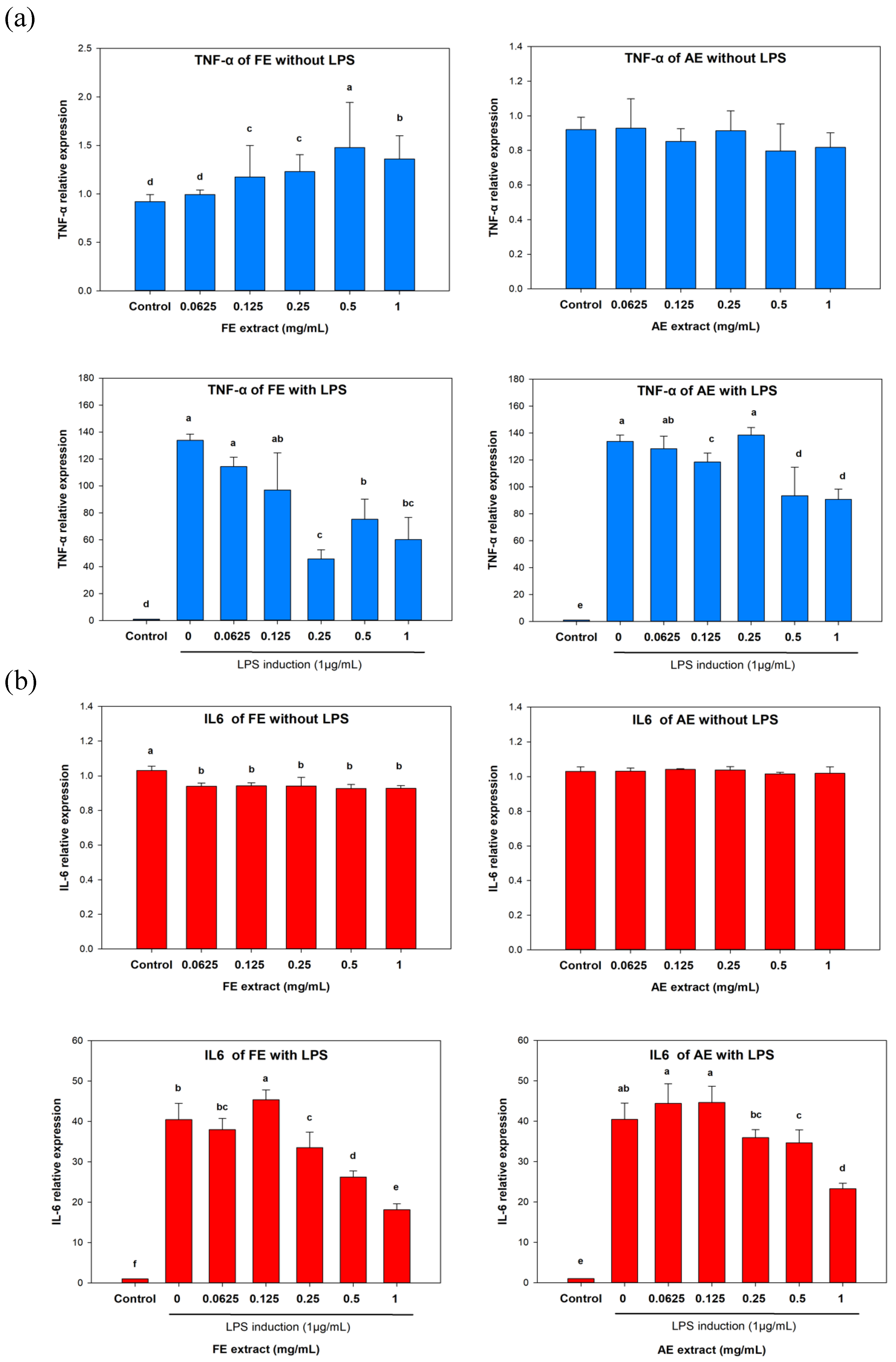

3.1. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of B. leptopoda Extracts in Macrophages

In the non LPS-induced inflammation of TNF-α expression (

Figure 3a), the

TNF-α RNA level was found to have slightly increased or remained unchanged with increasing FE and AE treatment concentrations. Compared to the untreated group (92%), the highest treatment concentrations (1 mg/mL) reached 136% (in the FE group) and 81.75% (in the AE group). However, in the LPS-induced inflammation group, expression levels of TNF-α decreased from 13,376% to 6006.5% and 9072.2%, respectively.

Interestingly, a similar trend was also observed in the analysis of IL-6 (

Figure 3b). In the LPS-induced inflammation group, the highest treatment concentrations of FE and AE (1 mg/mL) suppressed IL-6 expression from 4042.9% to 1811.5% and 2327%, respectively. These results indicated that both the FE and AE exhibited anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting TNF-α and IL-6 expressions. These proinflammatory cytokines are involved in different types of inflammation, which lead to apoptosis and cell death at the wound. Apoptosis of dermal keratinocytes was considered to have delayed the wound-healing process[

33]. Furthermore, the over-inflammation of a wound also causes release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) resulting in the formation of granulation tissues[

34]. Therefore, the anti-inflammatory properties of an extract can help the wound-healing processes of proliferation and remodeling.

3.1. Cell Cytotoxicity, Proliferation, and Migration of Fibroblast Cells

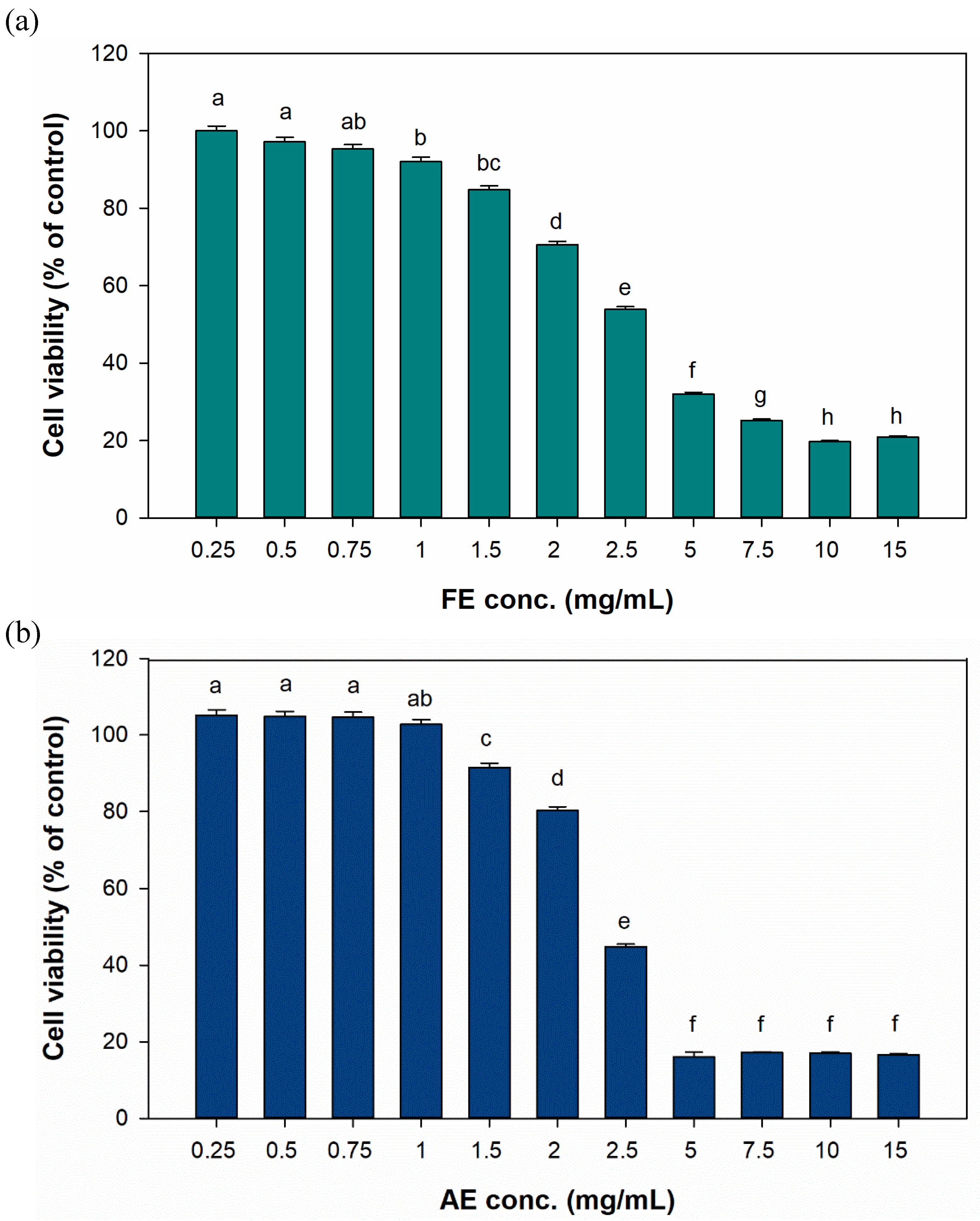

In the cytotoxicity results (

Figure 4), the FE and AE groups both maintained at least 80% cell viability at treatment concentrations below 1.5 mg/mL. However, at 2 mg/mL, cell viability significantly decreased to 70.59% and 80.3%, respectively. Therefore, test concentrations of < 2 mg/mL were utilized in subsequent cell-based experiments.

In the late stage of wound healing such as proliferation and remodeling, fibroblasts will adhere and migrate to the wound to release various signaling factors to enhance angiogenesis and granulation tissue formation[

35]. Hence, proliferation and migration abilities are crucial to evaluate the potential of wound-healing agents and dressings[

36]. In

Figure 5a, the FE group demonstrated a similar increase in proliferation effects following treatment with concentrations ranging from 0.25 to 1.5 mg/mL; however, a significant reduction in proliferation was observed at a concentration of 2 mg/mL. With AE treatment (

Figure 5b), although treatment with concentrations exceeding 1.5 mg/mL showed a slight reduction in their ability to enhance the proliferation ability, the overall treatment effects still promoted cell proliferation, ranging from approximately 112.3% to 87.7%. The observed results may be associated with cytotoxicity. By comparing cytotoxicity results with proliferation outcomes, it was evident that treatment groups showing a decline in the differentiation capacity exhibited a significant upward trend in cytotoxicity. Therefore, lower treatment concentrations of extracts (0.25 and 0.5 mg/mL) were used in the migration experiment. In addition, the observation that lower concentrations of the extract promoted cell migration may also have resulted from other potential mechanisms such as the involvement of bioactive compounds exhibiting biphasic effects. For instance, endostatin is known to enhance cell migration at specific concentrations, yet inhibits this process at higher concentrations, reflecting its dual functional characteristics[

37]. To confirm these effects, it is essential to isolate and characterize the active compounds for targeted validation through subsequent studies.

In

Figure 6a, all treatment groups exhibited significant cell migration, with cells moving from the seeding area to the central void within 24 h. Interestingly, in both the FE and AE groups, 0.25 mg/mL treatment (442.2% and 535.6%, respectively) demonstrated superior migration performance compared to 0.5 mg/mL treatment (398.7% and 387.8%, respectively) (

Figure 6b).

3.4. Evaluation of Scar Inhibition In Vitro

To evaluate the effect of

B. leptopoda extracts on scar inhibition

in vitro, a PMA-induced L929 cell model was utilized to investigate the RNA-level overexpression of MMPs, specifically

MMP1,

MMP2, and

MMP9 (

Figure 7a-c).

MMP1, classified as a collagenase, plays a critical role in collagen hydrolysis; however, its overactivity may lead to degradation of collagen fibers, contributing to reduced skin elasticity and wrinkle formation[

38]. MMP2 is a kind of gelatinase which is involved in matrix remodeling, but its overexpression was implicated in delayed wound healing and tissue degradation[

39]. MMP9 is essential for maintaining the dynamic equilibrium of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and is a key participant in wound-healing processes, serving as an important biomarker for anti-aging and skin regeneration[

40]. Nevertheless, aberrant upregulation of MMP9 was associated with excessive granulation tissue formation[

34], impaired healing, and the potential development of keloids[

41].

Figure 7a shows that PMA induction stimulated RNA expression of

MMP1 (166%). With FE treatment,

MMP1 RNA expression decreased to 110%. In results of

MMP9 RNA expression (

Figure 7b), the AE group exhibited a decrease in RNA expression from 199% to 136%. Interestingly, results for MMP2 (

Figure 7c) showed that both the FE and AE inhibited

MMP2 RNA expression from 540% to 277% and 93%, respectively. These results suggested that the FE can inhibit MMP1 and MMP2 overexpression to avoid skin elasticity decrease and wrinkle formation. Jung

, et al. [

42] reported that matrine can inhibit PMA-induced

MMP-1 mRNA expression by utilizing inhibition of activating protein (AP)-1 promoter activation, which may be helpful for anti-inflammation of dermatitis.

Results also showed that the AE greatly repressed MMP2 and MM9, which may lead to acceleration of wound healing and wrinkle formation caused by collagen degradation. However, this still needs to be further proven utilizing animal experiments. In addition,

TIMP-2 (the repressor gene of MMP2) RNA expression was also investigated (

Figure 7d). Results indicated that AE treatment strongly enhanced TIMP-2 expression, which suggests that the AE can downregulate expression levels of MMP2 by modulating TIMP-2 activity. A previous study also demonstrated similar results that the

Davallia bilabiate water extract decreased PMA-induced MMP2 expression by upregulating the

TIMP-2 RNA level, which provided a potential anti-angiogenic effect[

43].

In the other study from our research group[

44], the compositional analysis of AE and FE was conducted, revealing a similar constituent profile between the two. Both were found to primarily exhibit functions associated with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory activities. However, variations in the proportional distribution of these components were observed, which may account for the comparable effects of AE and FE in these functional domains. Furthermore, these findings provide additional evidence supporting their potential to promote wound healing.

Table 1.

B.

leptopoda extracts (FE and AE) composition analysis. [

44]

Table 1.

B.

leptopoda extracts (FE and AE) composition analysis. [

44]

| Proportion (%) |

Compound |

Potential skin care related function |

| FE extraction |

|

|

| 5.96 |

4-Hydroxyquinoline |

Antioxidant |

| 3.97 |

Phytosphingosine |

Skin protection |

| 1.44 |

1-Methylindole-3-carboxamide |

Improve skin barrier |

| 1.26 |

Docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) |

Anti-inflammatory |

| 1.25 |

Indole-5-carboxylic acid ethyl ester |

Immune regulation |

| AE extraction |

|

|

| 9.39 |

4-Hydroxyquinoline |

Antioxidant |

| 5.62 |

Phenylalanine betaine |

Anti-melanogenic properties |

| 2.95 |

Indole-5-carboxylic acid ethyl ester |

Immune regulation |

| 1.55 |

γ-Aminobutyric acid |

Skin repair |

| 1.25 |

1-Methylindole-3-carboxamide |

Improve skin barrier |

4. Conclusions

In summary, different B. leptopoda extracts were investigated for their in vitro antioxidation, proliferation, migration, and scar-inhibition activities. Result for the TPC showed that the AE had the highest phenolic compound contents. As to the antioxidative ability, the FE and HE presented the greatest DPPH-scavenging activities, and the AE exhibited an excellent FITA antioxidant ability. The FE and AE blocked LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 macrophages via suppressing proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 in concentration-dependent manners. As to proliferation, the FE and AE both presented an ability to enhance cell proliferation and migration at a low concentration of 0.25 mg/mL. Last but not least, the FE and AE suppressed MMP2 overexpression, while further respectively inhibiting MMP1 and MMP9. This may help prevent wrinkle formation and the loss of skin elasticity, and promote wound healing. In the future, further studies will focus on exploring the effects of specific compounds within the extracts on wound healing. Additionally, animal experiments will be conducted to validate the biological efficacy of these extracts in promoting wound healing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-K. Y., Y.-F. K. and H.-J. C.; methodology, T.-K. Y., Y.-F. K., M.-C. T. and H.-J. C.; validation, C.-C. H., Y.-C. C., S. -P. S. and J.-J. L.; data curation, S.-P. L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-C.H., J.-J.L., Y.-C.C. and S.-P.L.; writing—review, and editing, S.-P.L., C.-C.H., and K.-C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (NSTC-109-2628-E-002-007-MY3, NSTC-113-6819-002-300, NSTC113-2221-E-038-002 and NSTC 110-2320-B-158-001); Fisheries Research Institute, Ministry of Agriculture, Taiwan (111AS-6.3.1-AI-A1 & 112AS-6.3.1-AI-A1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gouripriya, D.; Adhikari, J.; Debnath, P.; Ghosh, S.; Ghosh, P.; Thomas, S.; Ghandilyan, E.; Gorbatov, P.; Kuchukyan, E.; Gasparyan, S. 3D printing of bacterial cellulose for potential wound healing applications: Current trends and prospects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 135213. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, G.; Abbott, J.; Sussman, G. The negative impact of medications on wound healing. Wound Pract Res 2024, 32, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, T.; Riazunnisa, K.; Vijaya Lakshmi, D.; Anu Prasanna, V.; Veera Bramhachari, P. Exploration of Bioactive Functional Molecules from Marine Algae: Challenges and Applications in Nutraceuticals. Marine Bioactive Molecules for Biomedical and Pharmacotherapeutic Applications 2024, 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Pruteanu, L.L.; Bailey, D.S.; Grădinaru, A.C.; Jäntschi, L. The biochemistry and effectiveness of antioxidants in food, fruits, and marine algae. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imchen, T.; Singh, K.S. Marine algae colorants: Antioxidant, anti-diabetic properties and applications in food industry. Algal Res. 2023, 69, 102898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Ki, J.-S. Biological activity of algal derived carrageenan: A comprehensive review in light of human health and disease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 238, 124085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Y.K.; Chang, J.-S. Proteins and bioactive peptides from algae: Insights into antioxidant, anti-hypertensive, anti-diabetic and anti-cancer activities. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2024, 104352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.; Martins, R.; Barbosa, M.; Valentão, P. Algae-Based Supplements Claiming Weight Loss Properties: Authenticity Control and Scientific-Based Evidence on Their Effectiveness. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurika, N.; Montuori, E.; Lauritano, C. Marine Microalgal Products with Activities against Age-Related Cardiovascular Diseases. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minhas, L.A.; Kaleem, M.; Farooqi, H.M.U.; Kausar, F.; Waqar, R.; Bhatti, T.; Aziz, S.; Jung, D.W.; Mumtaz, A.S. Algae-derived bioactive compounds as potential nutraceuticals for cancer therapy: A comprehensive review. Algal Res. 2024, 103396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chénais, B. Algae and microalgae and their bioactive molecules for human health. 2021, 26, 1185.

- Mimouni, V.; Ulmann, L.; Pasquet, V.; Mathieu, M.; Picot, L.; Bougaran, G.; Cadoret, J.-P.; Morant-Manceau, A.; Schoefs, B. The potential of microalgae for the production of bioactive molecules of pharmaceutical interest. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2012, 13, 2733–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, T.A.; Andryukov, B.G.; Besednova, N.N.; Zaporozhets, T.S.; Kalinin, A.V. Marine algae polysaccharides as basis for wound dressings, drug delivery, and tissue engineering: A review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, D.; Garg, Y.; Mahmood, S.; Chopra, S.; Bhatia, A. Marine-derived polysaccharides and their therapeutic potential in wound healing application - A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandika, P.; Ko, S.-C.; Jung, W.-K. Marine-derived biological macromolecule-based biomaterials for wound healing and skin tissue regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 77, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthan, P. Secondary Metabolites Screening, In vitro Antioxidant and Antidiabetic activity of Marine Red Alga Botryocladia leptopoda (J. Agardh) Kylin. Orient. J. Chem. 2022, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.; Dominguez-López, I.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. The Chemistry Behind the Folin–Ciocalteu Method for the Estimation of (Poly)phenol Content in Food: Total Phenolic Intake in a Mediterranean Dietary Pattern. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 17543–17553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, K.; Fujikawa, K.; Yahara, K.; Nakamura, T. Antioxidative properties of xanthan on the autoxidation of soybean oil in cyclodextrin emulsion. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1992, 40, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis, T.C.; Madeira, V.M.; Almeida, L.M. Action of phenolic derivatives (acetaminophen, salicylate, and 5-aminosalicylate) as inhibitors of membrane lipid peroxidation and as peroxyl radical scavengers. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994, 315, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mssillou, I.; Bakour, M.; Slighoua, M.; Laaroussi, H.; Saghrouchni, H.; Amrati, F.E.-Z.; Lyoussi, B.; Derwich, E. Investigation on wound healing effect of Mediterranean medicinal plants and some related phenolic compounds: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 298, 115663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Huang, J.; Lin, M.; Xie, T.; You, T. Quercetin promotes diabetic wound healing via switching macrophages from M1 to M2 polarization. J. Surg. Res. 2020, 246, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Ou, Q.; Xin, P.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J. Polydopamine/puerarin nanoparticle-incorporated hybrid hydrogels for enhanced wound healing. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 4230–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, M.; Vaez, A.; Naseri-Nosar, M.; Farzamfar, S.; Ai, A.; Ai, J.; Tavakol, S.; Khakbiz, M.; Ebrahimi-Barough, S. Naringin-loaded poly (ε-caprolactone)/gelatin electrospun mat as a potential wound dressing: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Fibers Polym. 2018, 19, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponrasu, T.; Veerasubramanian, P.K.; Kannan, R.; Gopika, S.; Suguna, L.; Muthuvijayan, V. Morin incorporated polysaccharide–protein (psyllium–keratin) hydrogel scaffolds accelerate diabetic wound healing in Wistar rats. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 2305–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Wu, J.-Q.; Fan, R.-Y.; He, Z.-H.; Li, C.-Y.; He, M.-F. Isoliquiritin promote angiogenesis by recruiting macrophages to improve the healing of zebrafish wounds. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 100, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Hou, S.; Song, S.; Zhang, B.; Ai, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, N. Impact of acidic, water and alkaline extraction on structural features, antioxidant activities of Laminaria japonica polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peasura, N.; Laohakunjit, N.; Kerdchoechuen, O.; Wanlapa, S. Characteristics and antioxidant of Ulva intestinalis sulphated polysaccharides extracted with different solvents. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 81, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, T.B.; Pereira, M.S.; Cavalcanti, M.I.L.; Fujii, M.T.; Chow, F. Antioxidant activity and related chemical composition of extracts from Brazilian beach-cast marine algae: opportunities of turning a waste into a resource. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 3383–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joorabloo, A.; Liu, T. Recent advances in reactive oxygen species scavenging nanomaterials for wound healing. In Proceedings of the Exploration; 2024; p. 20230066. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Shen, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, T.; Huang, Q.; Shen, M.; Xu, S.; Li, Y. A multilayer hydrogel incorporating urolithin B promotes diabetic wound healing via ROS scavenging and angiogenesis. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 496, 153661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, Y.L.; Lim, Y.Y.; Omar, M.; Khoo, K.S. Antioxidant activity of three edible seaweeds from two areas in South East Asia. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2008, 41, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Jónsdóttir, R.; Ólafsdóttir, G. Total phenolic compounds, radical scavenging and metal chelation of extracts from Icelandic seaweeds. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secor, P.R.; James, G.A.; Fleckman, P.; Olerud, J.E.; McInnerney, K.; Stewart, P.S. Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm and Planktonic cultures differentially impact gene expression, mapk phosphorylation, and cytokine production in human keratinocytes. BMC Microbiol. 2011, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, L.; Larjava, H.; Koivisto, L. Granulation tissue formation and remodeling. Endod Topics. 2011, 24, 94–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S.; Grose, R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol. Rev. 2003, 83, 835–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-P.; Kung, H.-N.; Tsai, Y.-S.; Tseng, T.-N.; Hsu, K.-D.; Cheng, K.-C. Novel dextran modified bacterial cellulose hydrogel accelerating cutaneous wound healing. Cellulose 2017, 24, 4927–4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, I.; Sürücü, O.; Dietz, C.; Heymach, J.V.; Force, J.; Höschele, I.; Becker, C.M.; Folkman, J.; Kisker, O. Therapeutic efficacy of endostatin exhibits a biphasic dose-response curve. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 11044–11050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledwoń, P.; Papini, A.M.; Rovero, P.; Latajka, R. Peptides and peptidomimetics as inhibitors of enzymes involved in fibrillar collagen degradation. Mater. 2021, 14, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caley, M.P.; Martins, V.L.; O’Toole, E.A. Metalloproteinases and wound healing. Advances in wound care 2015, 4, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, R.; Chintala, S.K.; Jung, J.C.; Villar, W.V.; McCabe, F.; Russo, L.A.; Lee, Y.; McCarthy, B.E.; Wollenberg, K.R.; Jester, J.V. Matrix metalloproteinase gelatinase B (MMP-9) coordinates and effects epithelial regeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 2065–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanriverdi-Akhisaroglu, S.; Menderes, A.; Oktay, G. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and-9 activities in human keloids, hypertrophic and atrophic scars: a pilot study. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2009, 27, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.; Lee, J.; Huh, S.; Lee, J.; Hwang, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.W.; Park, D.; Yo Byun, S. Matrine inhibits PMA-induced MMP-1 expression in human dermal fibroblasts. Biofactors 2008, 33, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-T.; Bi, K.-W.; Huang, C.-C.; Wu, H.-T.; Ho, H.-Y.; Pang, J.-H.S.; Huang, S.-T. Davallia bilabiata exhibits anti-angiogenic effect with modified MMP-2/TIMP-2 secretion and inhibited VEGF ligand/receptors expression in vascular endothelial cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 196, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-C.; Yi, T.-K.; Kao, Y.-F.; Lin, S.-P.; Tu, M.-C.; Chou, Y.-C.; Lu, J.-J.; Chai, H.-J.; Cheng, K.-C. Comparative Efficacy of Botryocladia leptopoda Extracts in scar inhibition and skin regeneration: A study on UV protection, collagen synthesis, and fibroblast proliferation. Molecules 2024, 29, 5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).