1. Introduction

With its peculiar structure and composition, the skin is an organ that acts both as a barrier and an interface of the human body with the external environment. From blocking outer hazards into entering or affecting the organism to granting humans the ability to sense the world around them and adapt to it, this organ, the largest of the human body, possesses functions and mechanisms essential for life. However, it is necessary to highlight the vulnerability of this tissue to damage. A wound is a damage to the natural structure, integrity and functions of the skin caused by a mechanical, chemical or physical agent. The injury modifies the communication skills within the cutaneous tissue itself and with the surrounding environment. This can potentially expose the organism to infections, loss of mobility, pain and non-healing of the wounds, dramatically affecting the patients’ quality of life [

1]. In the four stages of the healing process (haemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, remodeling), a key role is played by several factors released by the cells present and attracted at the site of the injury, such as cytokines involved in the inflammatory process and chemokines for the recall of immunity cells, GFs which stimulate the proliferation of the epithelial and endothelial cells and remodeling enzymes like the MMPs to re-elaborate the ECM after the damage to the skin [

2].

Due to the current lack of effective treatment options, part of the research for possible stimulating agents of the wound healing process shifted to natural products. The choice for this change is justified by the significant pharmacological properties they show, conferred by their components and phytocomplexes [

3]. The employment of medicinal herbs and plant-derived substances in wound healing has the aim of reducing the onset of complications such as infection or chronicization of the wound [

4]. Undoubtedly, the specific composition of every medicinal plant/natural substance influences the effects on the illness or physiological pathway under study. The response variability, also observable in the same categories of plants/materials, is often due to differences in the quantity of single components, each one of them with distinct levels of bioactivity.

Propolis, a mixture of substances gathered by bees from a variety of plant sources, is one of the most used plant-derived products for topical application since ancient times. Its antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties make it a perfect example of a natural substance useful to enhance the wound healing process.

Given the considerable weight of the local flora in propolis composition, it is possible to classify distinct types of propolis based on the geographical area. An example is the poplar-type propolis from temperate zones rich in flavonoids and phenolic acid esters, essential molecules for the properties of the mixture. Furthermore, it is not unusual to observe differences in the quantity of single molecules in propolis of the same class. It should also be noted the variability in composition of the subsequent formulation based on the extraction method used [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

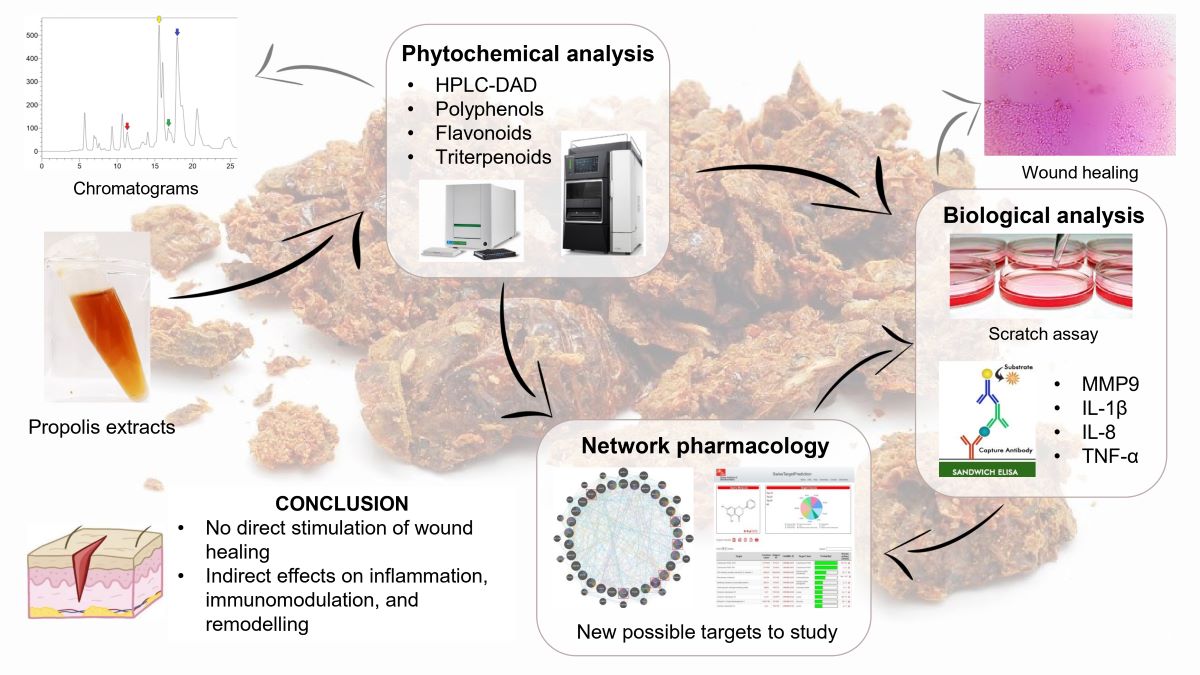

In this work the differences between four poplar-type propolis will be evaluated chemically and biologically, focusing on the different stimulation of the wound healing process on both keratinocytes and fibroblast, with the objective of highlight the importance of the composition of various propolis formulations on the healing of injuries, while also evaluating the influence of extraction methods.

2. Results

2.1. Phytochemical Analysis

The results of the Folin-Ciocâlteu assay, expressed as GAE ± SD, were 21.13 ± 1.17% (Sample 1), 14.25 ± 0.57% (Sample 2), 18.50 ± 0.90% (Sample 3), and 0.50 ± 0.06% (

Table 1). Except for Sample 4, the obtained data have confirmed that phenolic molecules are one of the main components of propolis. The notable discrepancy of Sample 4 compared to the other ones might be due to the nature of this specific sample, which may have requested a particular type of extraction to bring out the molecules of interest.

The obtained total flavonoids concentration, expressed as Galangin Equivalents ± SD, were 19.68 ± 0.36% (Sample 1), 9.55 ± 0.23% (Sample 2), 13.09 ± 0.46% (Sample 3), and 0.25 ± 0.20% (Sample 4) (

Table 2). The concentration of flavonoids in the different samples not only reflects the trend of total phenolics shown in

Table 1, but also represents almost all of the phenolic molecules in Sample 1 (~ 93%) and more than two thirds in Sample 2 (~ 67%) and 3 (~ 71%), confirming that flavonoids represent the major part of the total phenolic fraction of propolis.

The determined triterpenoid contents, expressed as β-sitosterol Equivalents ± SD, were 61.19 ± 0.60% (Sample 1), 43.15 ± 0.31% (Sample 2), 65.00 ± 0.64 (Sample 3), and 2.74 ± 0.14% (Sample 4) (

Table 3). The elevated quantities of triterpenes found in the analyzed samples highlight the resinous nature of propolis.

Compared to Samples 1 and 3, Sample 2 exhibited an inferior triterpenes concentration, probably due to the industrial procedures of removal of waxes, extraction and purification to which it was subjected. Also in this case, Sample 4 showed the lowest concentration of triterpenes, differing greatly from the other three propolis.

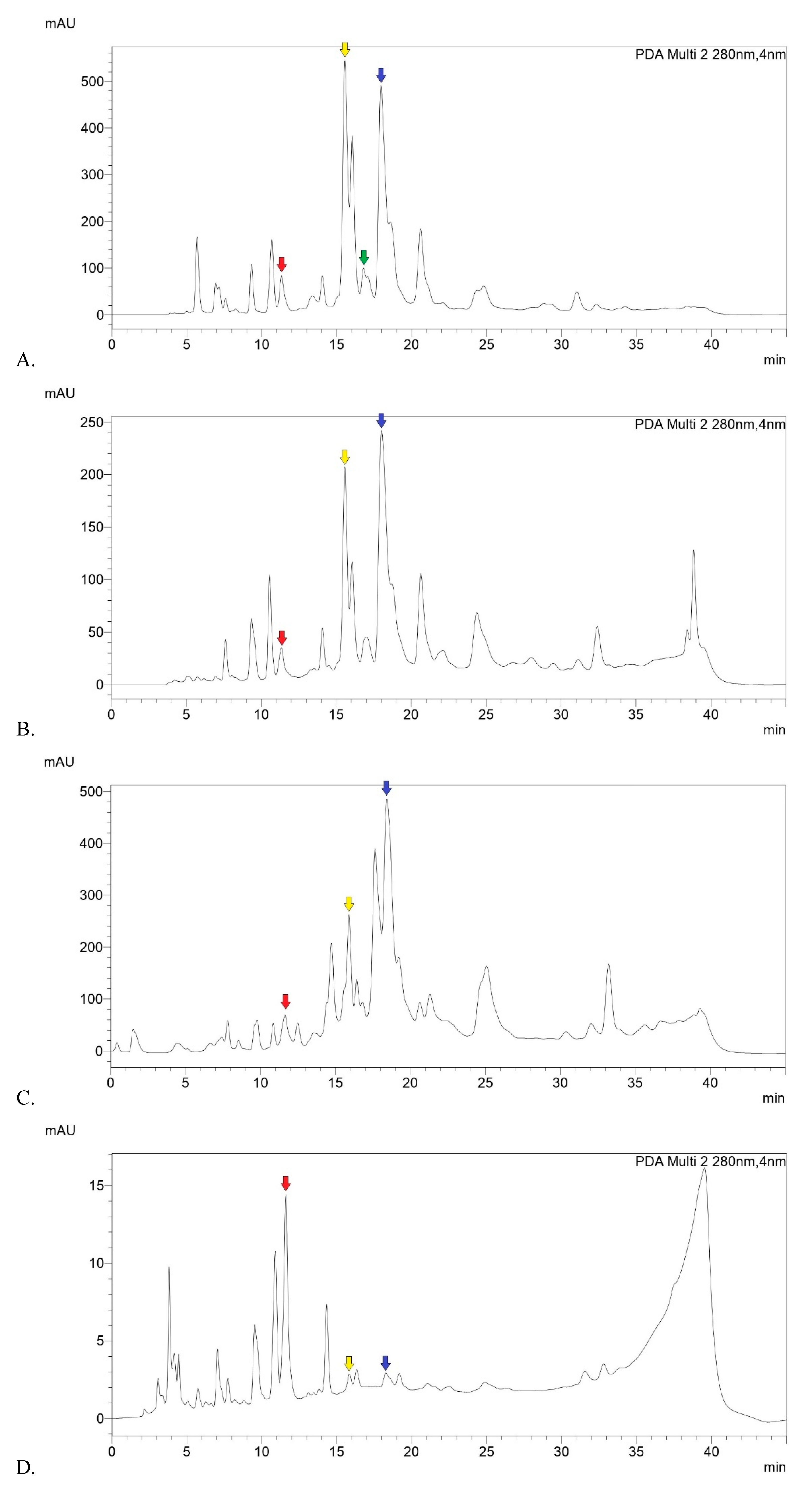

The HPLC-DAD analysis of the samples produced the following results for the concentrations of the five main molecules of interest, expressed as %

w/

w ± SD (except for Sample 4, expressed as %

w/

w). Sample 1: 1.46 ± 0.27% (pinobanksin), 8.14 ± 1.40% (pinocembrin), 1.93 ± 0.34% (CAPE), 13.22 ± 2.25% (galangin + chrysin). Sample 2: 0.66 ± 0.08% (pinobanksin), 2.88 ± 0.42% (pinocembrin), < 0.01% (CAPE), 8.60 ± 2.76% (galangin + chrysin). Sample 3: 1.29 ± 0.05% (pinobanksin), 3.68 ± 0.81% (pinocembrin), < 0.01% (CAPE), 12.68 ± 2.23% (galangin + chrysin). Sample 4: 0.31% (pinobanksin), 0.03% (pinocembrin), < 0.01% (CAPE), 0.02% (galangin + chrysin) (

Table 4).

Is worth noting that CAPE was only detectable in Sample 1, maybe due to the industrial processes which the other samples were subjected to. The peaks of chrysin and galangin could not be separated and were considered as one. Taking into account the coelution of these two molecules, pinocembrin showed to be the main constituent of the poplar propolis under study, followed by chrysin and galangin.

Below the registered chromatograms (

Figure 1). On a qualitative level, it can be noted that chromatograms of Sample 1, 2 and 3 showed a similar peak profile, reflecting the similar composition of the starting material of the samples (raw poplar propolis). The chromatogram of Sample 4 showed to be the most different, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

2.2. Biological Analysis and Network Pharmacology

The results obtained from the DPPH assay (IC

50 expressed as μg/mL ± SD) are 26.09 ± 1.30 (Sample 1), 54.38 ± 2.72 (Sample 2), 45.50 ± 2.28 (Sample 3), and > 1 000 (Sample 4) (

Table 5), while those of the ORAC assay, expressed as mM/g ± SD of Trolox Equivalents, are 8.89 ± 1.50 (Sample 1), 4.93 ± 2.21 (Sample 2), 6.96 ± 2.05 (Sample 3), and 3.01 ± 1.79 (Sample 4) (

Table 6). For each sample, both the radical scavenging capacity and the antioxidant power, are in line with the respective concentrations of total phenolics and flavonoids.

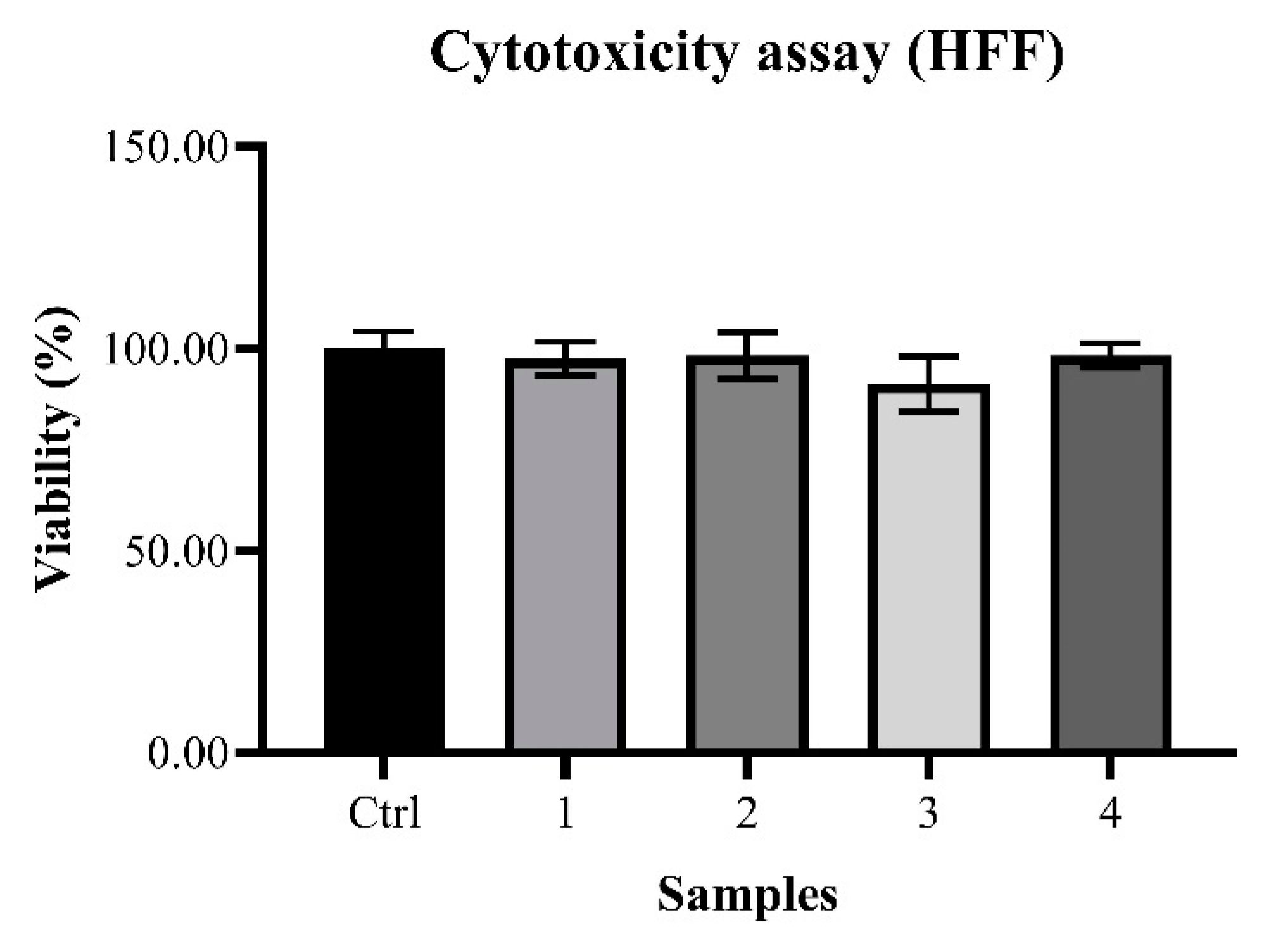

The observed cytotoxicity assay outcomes on HFF cells were 100.00 ± 6.23% (Control), 97.50 ± 4.16% (Sample 1), 98.28 ± 5.78% (Sample 2), 91.17 ± 6.82% (Sample 3), and 98.26 ± 3.04% (Sample 4) (

Graph 1), basically showing an absence of toxicity in all propolis samples at the tested concentrations.

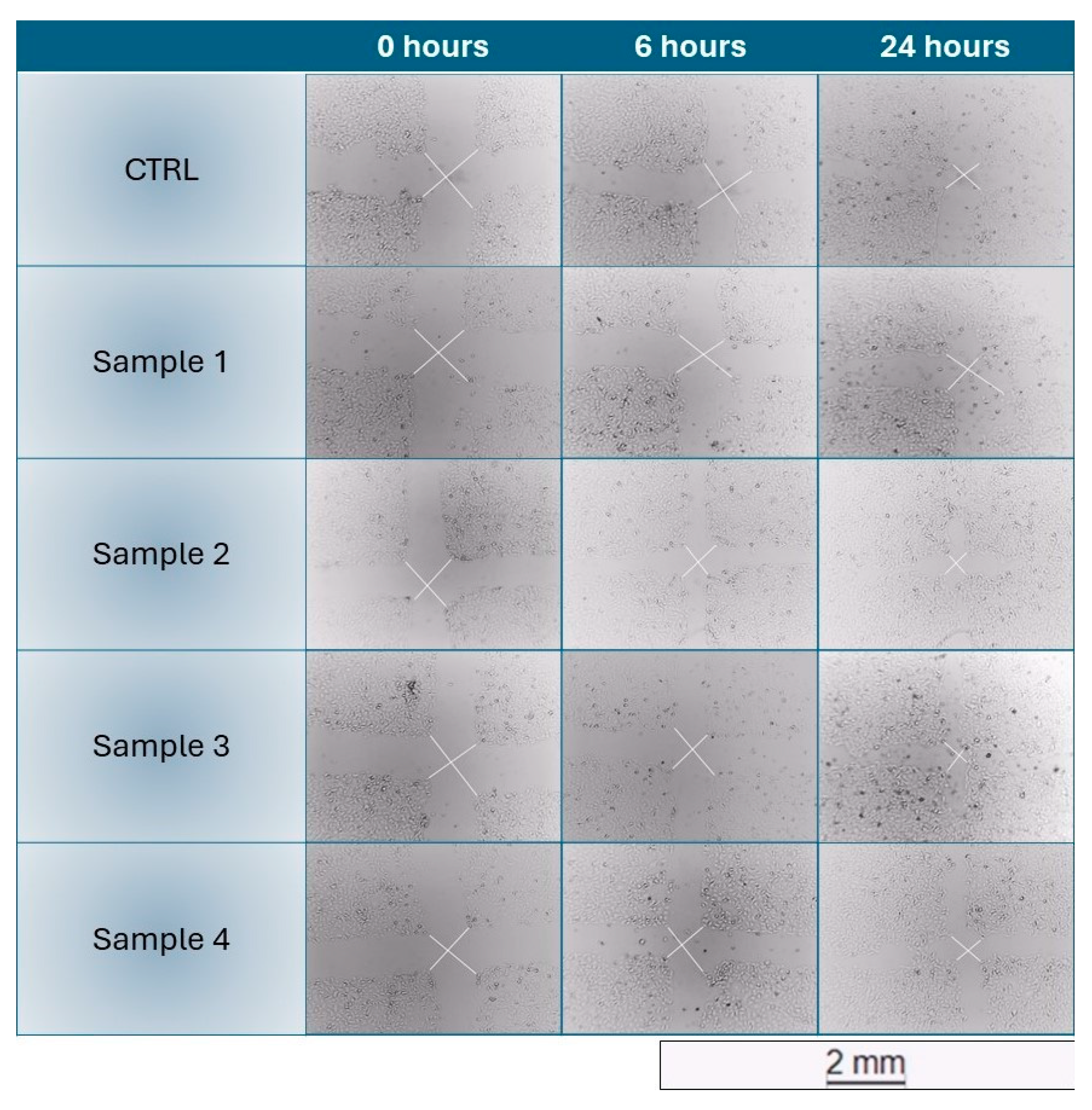

The scratch wound healing assays carried out resulted in no improvement of the healing process by the samples (mean relative healing of samples < mean relative healing of Control), with sporadic exceptions that were not significant (example of HaCaT healing in

Figure 2). These results suggested that propolis may not have a direct effect on the healing of wounds by stimulating the proliferation or the migration of the epithelial cells.

The study proceeded with the quantification of two of the main GFs responsible for the epithelial cell proliferation and growth: FGF and TGF-β.

The quantification of FGF-7 produced the following relative results: 1.004 ± 0.088 (Control), 0.986 ± 0.054 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 1), 1.037 ± 0.085 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 2), 1.024 ± 0.066 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 3), and 1.122 ± 0.075 with

p< 0.001 (Sample 4). Those obtained for LAP are: 1.002 ± 0.070 (Control), 0.989 ± 0.059 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 1), 1.020 ± 0.046 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 2), 1.007 ± 0.051 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 3), and 1.094 ± 0,078 with

p< 0.01 (Sample 4) (

Graph 2).

These null outcomes line with those of the scratch wound healing assays, pointing to the same conclusion: propolis has a healing effect on wounds confirmed by traditional use, but this may not be due to a direct effect on the epithelial cells through the stimulation of their proliferation and/or migration. The opposite results from the treatment with Sample 4 could be explained by the sugary nature of this sample, which may have invigorated the cells metabolism and viability.

The inclusion of the 5 molecules analyzed and recognised by HPLC-DAD (pinobanksin, pinocembrin, CAPE, galangin, chrysin) as input in SwissTargetPrediction led to an important convergence of prediction towards the MMP enzyme family: in particular, as shown in

Table 7, 4 matches for MMP2 (mean probability 0.1128), 4 matches for MMP9 (mean probability 0.1128), 4 matches for MMP12 (mean probability 0.1422) and 3 matches for MMP13 (mean probability 0.1480) were highlighted.

Although the matching probabilities are significantly lower than the standard references reported by the developers of molecular prediction software (Combined-Score higher than 0.5) [

11], this finding was nevertheless taken into account, considering that in the heterogeneity of the propolis phytocomplex, most of the five molecules taken into account and analyzed with SwissTargetPrediction share the MMP target, suggesting a plausible increase in the probability of prediction in reality due to the matrix effect.

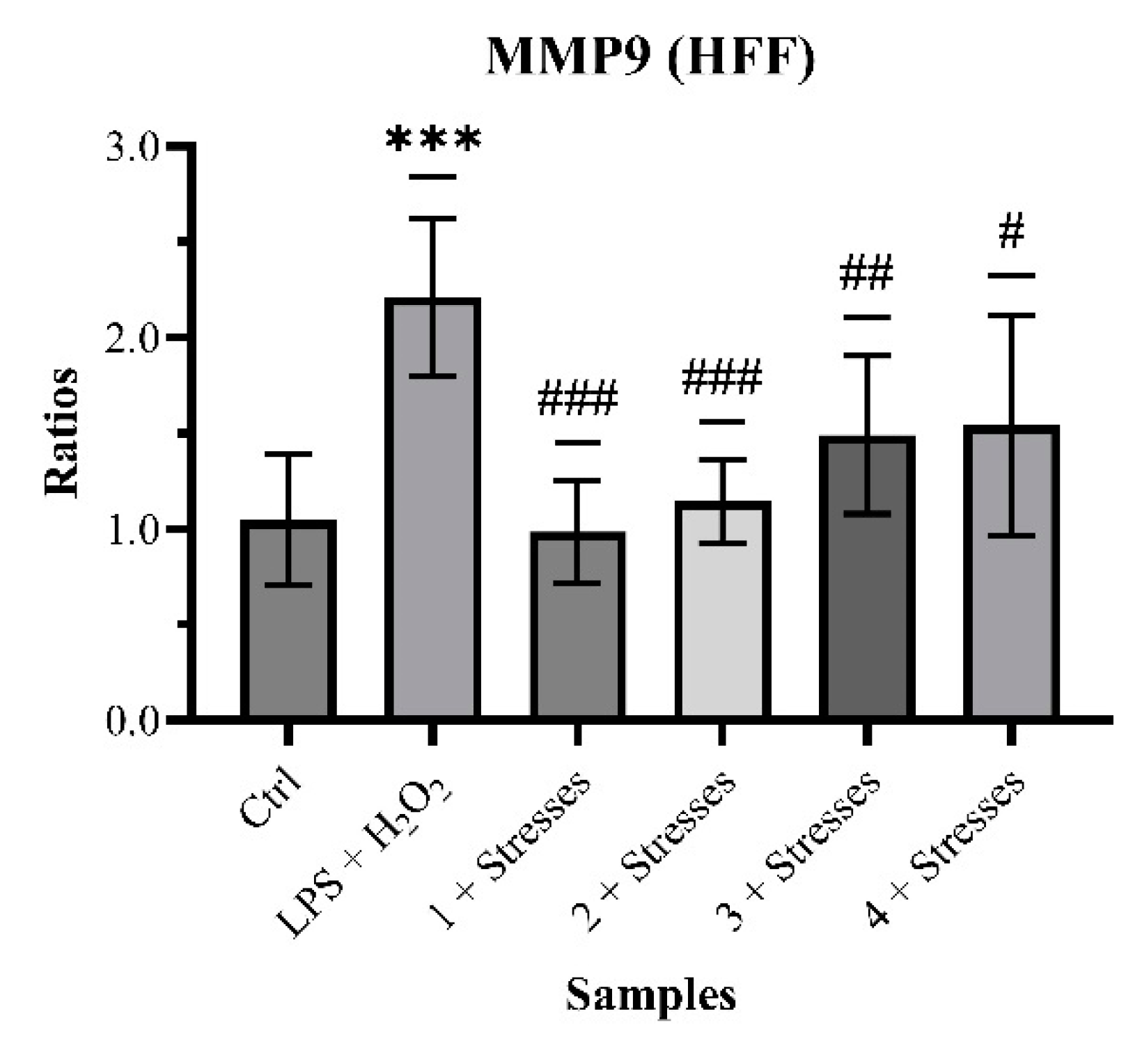

Quantification of MMP9 gave the following results: 1.047 ± 0.342 (Control), 2.211 ± 0.413 with

p< 0.001 (LPS + H

2O

2), 0.983 ± 0.267 with

p< 0.001 (Sample 1 + Stresses), 1.146 ± 0.218 with

p< 0.001 (Sample 2 + Stresses), 1.490 ± 0.413 with

p< 0.01 (Sample 3 + Stresses), and 1.541 ± 0.577 with

p< 0.05 (Sample 4 + Stresses) (

Graph 3).

The clear outcomes of this experiment show propolis possible ability to modulate one of the main phases of the wound healing process, the remodeling, by limiting the over-production of MMP9 in response to a damaging stimulus (here both inflammatory and oxidative stress).

Another step was to evaluate propolis direct activity on the ECM-degrading enzymes. The collagenase inhibition assay results (IC

50 expressed as μg/mL ± SD) are 41.61 ± 2.08 (Sample 1), 113.96 ± 5.70 (Sample 2), 51.57 ± 2.58 (Sample 3), and > 200 (Sample 4) (

Table 8).

Together with the results on MMP9 synthesis, these outcomes point to a probable action of propolis on the whole remodeling phase of wound healing, by simultaneously decreasing the overproduction of MMPs after a damage and inhibiting the enzymes already in the site.

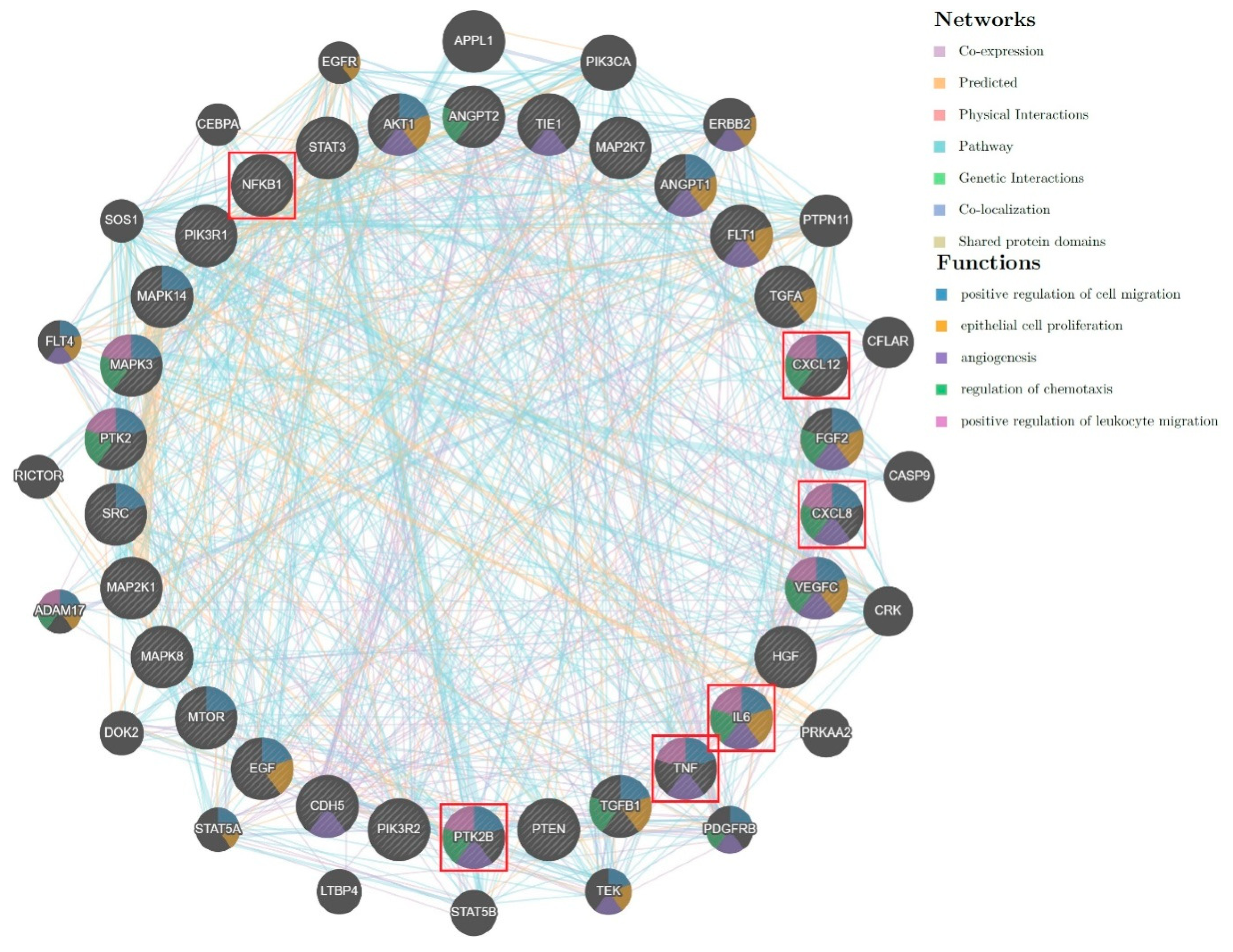

To expand the pool of possible targets of propolis involved in the wound healing process, the research moved on to other in silico target prediction tools.

By inserting twenty-four targets (see Chapter 2.5) derived from the analysis of the five marker molecules for poplar propolis with SwissTargetPrediction, thirty new targets were proposed by GeneRecommender AI engine as output (

Figure 3). Among these possible targets, some of them were pointing to a possible influence of poplar propolis main constituents on both inflammation and immunomodulation.

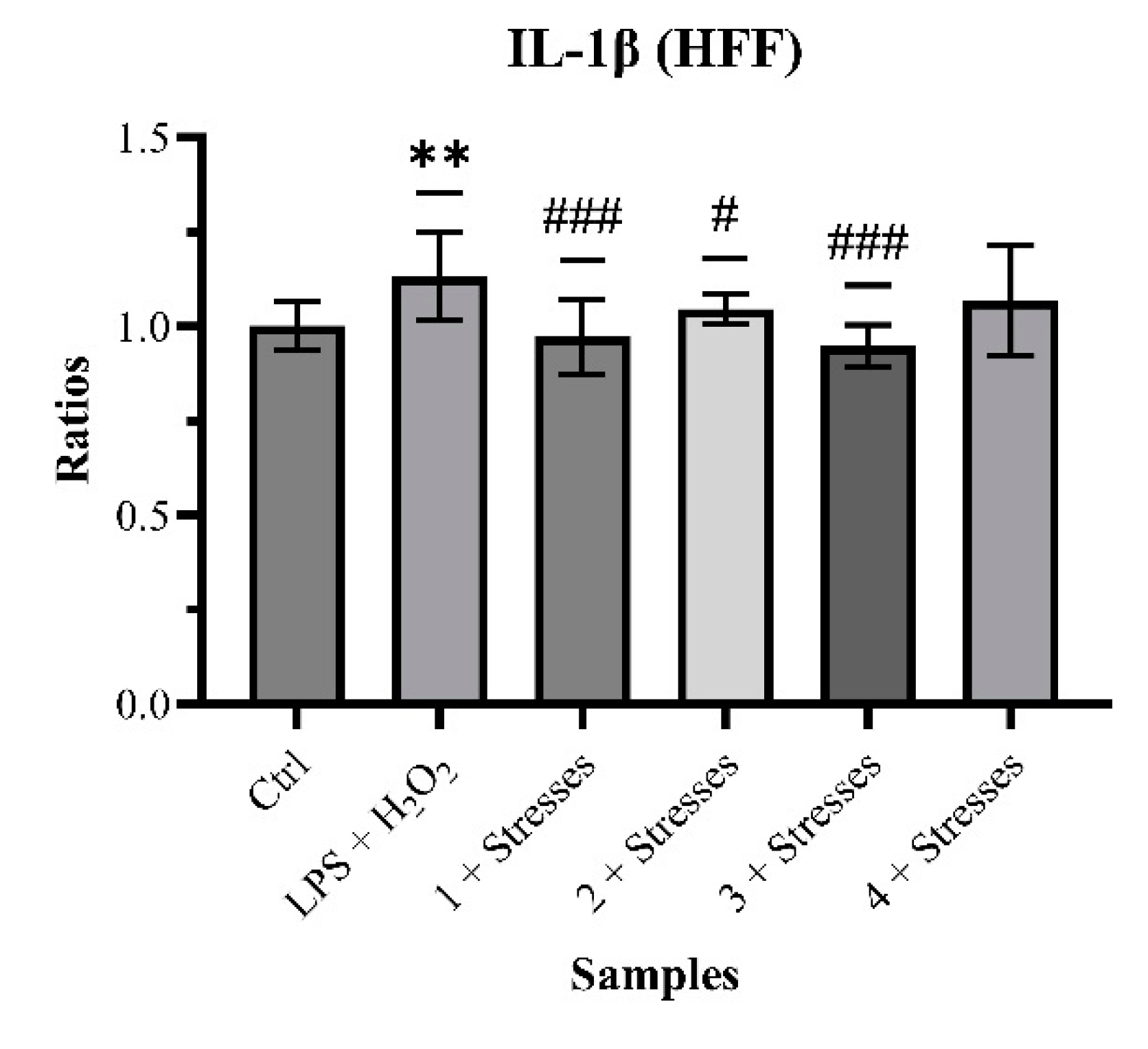

The possible anti-inflammatory activity during wound healing was firstly evaluated on stimulated fibroblasts.

Quantification of IL-1β produced, as relative results, 1.002 ± 0.064 (Control), 1.133 ± 1.117 with

p< 0.01 (LPS + H

2O

2), 0.973 ± 0.099 with

p< 0.001 (Sample 1 + Stresses), 1.046 ± 0.041 with

p< 0.05 (Sample 2 + Stresses), 0.948 ± 0.056 with

p< 0.001 (Sample 3 + Stresses), and 1.069 ± 0.146 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 4 + Stresses) (

Graph 4).

Even if the stresses did not produce an impressive response on the cells, the co-treatments showed a statistically significant reduction in the production of IL-1β, one of the main pro-inflammatory cytokines.

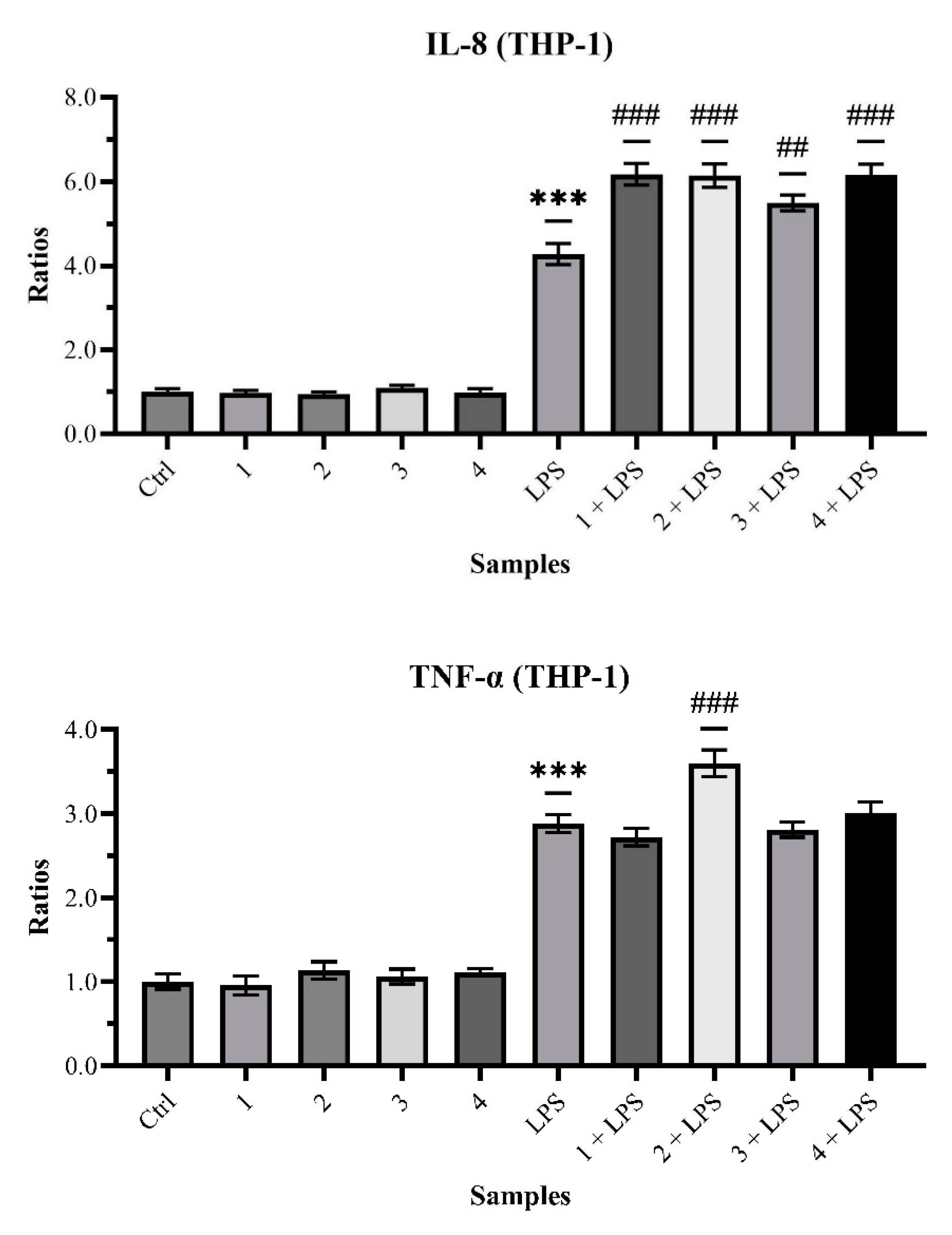

A great part in the wound healing process is played by the immune cells already present in the damaged skin or summoned from the bloodstream. In addition to the anti-inflammatory effect of propolis on immunity cells, it was also studied its immunomodulatory activity.

The quantification of IL-8 in treated THP-1 gave the following relative outcomes: 1.002 ± 0.080 (Control), 0.982 ± 0.057 with p> 0.05 (Sample 1), 0.949 ± 0.055 with p> 0.05 (Sample 2), 1.095 ± 0.064 with p> 0.05 (Sample 3), 0.991 ± 0.089 with p> 0.05 (Sample 4), 4.344 ± 0.343 with p< 0.001 (LPS), 6.172 ± 0.258 with p< 0.001 (Sample 1 + LPS), 6.140 ± 0.276 with p< 0.001 (Sample 2 + LPS), 5.494 ± 0.187 with p< 0.01 (Sample 3 + LPS), and 6.154 ± 0.261 with p< 0.001 (Sample 4 + LPS).

Those obtained from the quantification of TNF-α are: 1.002 ± 0.091 (Control), 0.956 ± 0.115 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 1), 1.132 ± 0.105 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 2), 1.061 ± 0.087 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 3), 1.113 ± 0.044 with

p< 0.05 (Sample 4), 2.879 ± 0.108 with

p< 0.001 (LPS), 2.722 ± 0.105 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 1 + LPS), 3.598 ± 0.159 with

p< 0.001 (Sample 2 + LPS), 2.811 ± 0.094 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 3 + LPS), and 3.003 ± 0.137 with

p> 0.05 (Sample 4 + LPS) (

Graph 5).

While the results on TNF-α are inconclusive to ascertain the anti-inflammatory action of propolis on immune cells, those on IL-8 highlight its obvious immunomodulatory activity.

The outcomes of the various experiments could provide a deepened understanding of the mechanisms of action of propolis on the wound healing process.

The scratch wound healing assays and the quantifications of the GFs proved that propolis do not have a direct positive influence on the healing by promoting cell proliferation or migration. Instead, it showed to be able to act on two of the main phases of the process: the inflammation, by both decreasing the epithelial release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enhancing the recall of immune cells, hastening the resolution of the phase and thus reducing the risks of chronicization; the remodeling, by both inhibiting the activity of ECM-degrading enzymes and reducing their synthesis, improving the settlement of the new cells and ECM and avoiding the excessive degradation of the matrix.

3. Discussion

As regards the phytochemical analysis, the obtained data have confirmed that phenolic molecules are one of the main components of propolis. Albeit propolis composition, including TPC, is heavily influenced by a number of factors (mainly botanic and geographic) which cause a high variability in the quantities of its constituents [

12], the measured values are along the lines of those of common poplar-type samples.

Among the phenolic secondary metabolites of plants that are transferred in propolis, flavonoids represent the majority of them in propolis from temperate zones, such as the poplar type, and the obtained data proved this observation for the samples under study.

Being propolis a resinous substance, it is simple to understand why terpenes constitute the main class of molecules of the mixture, with the lighter ones (mono- and sesqui-terpenes) constituting the essential fraction and the heavier ones (di- and tri-terpenes) the resinous one. The experimentation data are relatable to the percentages that can be found in literature (~ 50% resins, ~ 10% essential oils) [

13,

14], with only Sample 2 that exhibited an inferior concentration, probably due to the industrial procedures of removal of waxes, extraction and purification to which it was subjected.

The quantification by means of HPLC-DAD of some of the marker molecules of poplar propolis (pinobanksin, pinocembrin, CAPE, chrysin and galangin) acknowledge the profound influence on the TFC of pinocembrin, chrysin and galangin while confirming the presence of pinobanksin, typical of the poplar class together with pinocembrin.

CAPE was detected only in Sample 1. This can be justified by the possible hydrolysis of the phenethyl group from the CAPE molecules induced by the purification and other processes which Samples 2 and 3 were exposed to. Galangin and chrysin have very close retention times (RTs) (~ 18.2 min and ~ 18.6 min, respectively, obtained by using external standards), and have therefore been quantified as a single peak. Taking into account the coelution of these two molecules, pinocembrin can be considered the main constituent of the poplar propolis under study.

The particularly low results shown by Sample 4 in the various assays can be ascribed to its pharmaceutical form. The sample is thought as an oral supplement to support immune and respiratory health, so its form was adapted to allow the greatest absorption of polyphenols to occur in the gastrointestinal tract. The simple extraction methodology used to prepare the sample for the experiments of this work (water solution in ultrasound bath for 30 minutes) proved to be inadequate to obtain a solution of most characteristic constituents of propolis.

Shifting to biological experimentation, the results of the DPPH and ORAC assays (scavenging/antioxidant capacity) are correlatable to the TPC (R

2 = 0.88). Indeed, the samples with higher phenolic content (1 > 3 > 2) are also the ones with higher scavenging activity and TAC. The DPPH values are also comparable to those that can be found in literature [

15].

The cytotoxicity assay tested the concentrations of interest of the four samples of propolis on fibroblasts cultures. The experiment proved no significant effect, concluding that there are no cytotoxic effects on cells given by the samples.

The wound healing properties of propolis are widely reported in literature and are one of the main reasons for its common application in the pharmaceutical field. The purpose of the scratch wound healing assays carried out was to evaluate the possible induction of proliferation and migration by propolis on keratinocytes (HaCaT) and fibroblasts (HFF) pure cell lines. The experiments led to the conclusion that the samples did not invoke a direct response on the cells to alter the healing process. The treated cells healed the groove normally as the untreated control ones.

To confirm the results of the scratching assays on the main epithelial cells, the following step was to evaluate the possible variation in the synthesis/release of GFs, as fundamental components of the proliferation process, in HFF cultures treated with the propolis under study. The chosen GFs to be quantified were FGF-7 and TGF-β. Specifically, the latter one was determined through LAP, a homodimer relevant in regulating the activity of TGF-β and contained in the synthetized precursor of TGF-β.

The quantification experiments results showed no statistically significant variation in the levels of both FGF-7 and LAP. The only statistical increments, noted for the readings with HFF treated with Sample 4, did not reach a particularly high point and can be plausibly ascribed, at least in part, to the maltodextrin and sugars content of the sample, as they may trigger skin cells receptors and upregulate their metabolism (as already known, for example, for aloe gel or honey). A rise in the supply of nutrients to the cells can be easily connected to the enhancement of metabolic processes of the cells themselves, synthesis of proliferation and growth factors included.

Accordingly to the data obtained from the scratching and quantification assays, it was possible to conclude that the propolis samples did not have a direct effect on the proliferation capacity of the main epithelial cell lines, pointing to the fact that the wound healing properties already confirmed by many sources in literature should be attributed to indirect outcomes of the treatment with propolis on other phases of the healing process.

To test other mechanisms of action of propolis on the healing process and to, consequently, expand the pool of possible targets to put under test, the NP analysis was introduced in the study.

The first software used was SwissTargetPrediction. By inserting the compound of interest, the web-based application provides up to one hundred possible macromolecular targets which should interact with the molecule added as input, each associated with a probability calculated based on the similarity of the molecule with a database of known small molecules that surely interact with that target.

For this study, the molecules analyzed with SwissTargetPrediction were the five representative phytoconstituents of poplar propolis (pinobanksin, pinocembrin, CAPE, chrysin, and galangin). Among the numerous targets obtained, MMPs were one class which occurred quite frequently as output.

Recognizing it from the literature as one of the key participants in wound healing, MMP9 was chosen as the next objective of the experiments for this study. In the context of an inflammatory and oxidative stress, typical of any common wound, HFF cultures were treated with the samples of propolis for 24 hours and then the levels of MMP9 were quantified through an ELISA. All co-treatments induced a statistical reduction in the levels of MMP9.

Having recognized the properties of propolis to induce a decrease in MMP9 expression in fibroblasts, the following test expanded the experimentation to more MMPs. Among the various enzymes which operate on ECM components, collagenases represent one of the main types involved in the restoration of damaged tissues. Their abnormal induction and/or inhibition could significantly alter the finely coordinated mechanism of wound healing.

The assay, based on the evaluation of the capacity of substances to inhibit the activity of different collagenases, was paired with the previous one to establish a global effect of the samples on the ECM-degrading enzymes. Its results show that even low concentrations of propolis are capable of inhibiting the activity of collagenases.

To explore other possible pathways by which propolis could affect the healing process, another software, GeneRecommender, was employed to further analyze the results obtained with SwissTargetPrediction. By adding the target outputs of the latter application, selected based on their connection with wound healing, as input in GeneRecommender, up to fifty new targets (both genes and proteins) closely connected to the query are suggested by its AI engine.

After inserting twenty-four targets derived from the previous analysis of the five marker molecules for poplar propolis with SwissTargetPrediction, thirty new targets were proposed by GeneRecommender AI engine as output. Besides different outputs associated with signaling pathways, GFs and their receptors, various targets (e.g., CXCL12, CXCL8, IL6, TNF, PTK2B) were comprised into the inflammatory and/or immunomodulatory fields, a connection well justified by literature due to the proven anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties of propolis.

Given the firm relationship between the four phases of wound healing, which all contributes to a fast and healthy recovery, the study moved towards the second phase of the healing process, the inflammation, heavily influenced by the cytokines and chemokines released by the epithelial cells and by the immunity cells summoned in the site of the injury.

In this regard, it was tested the anti-inflammatory activity of the samples on stressed fibroblasts and monocytes and the immunomodulatory properties on the latter ones. Specifically, quantification assays were carried out for IL-1β on HFF and for IL-8 and TNF-α on THP-1.

Even if the production of IL-1β in stressed fibroblasts was not particularly high, Samples 1, 2, and 3 all statistically decreased its synthesis, confirming their anti-inflammatory action on epithelial cells.

In reverse, the same activity in the immunity cells with TNF-α showed inconclusive results.

On the immunomodulatory side, instead, all the sample co-treatments proved to significantly influence the synthesis of IL-8, increasing its levels compared to the sole LPS treatment.

4. Materials and Methods

The experimental part of this work included the phytochemical characterization of the four poplar-type propolis samples, followed by their in vitro testing using HaCaT, HFF and THP-1 as cell lines, together with cell-free assays, to evaluate the effects on the wound healing process. All the assays, both the phytochemical and biological analyses, were performed in triplicate.

4.1. Samples

“Sample 1” has been chosen as a representative of an Italian, poplar-type propolis among thirty-two samples, all of them produced in spring 2020 in various Italian regions and provided by local beekeepers. Major debris and waxes have already been removed when the propolis were supplied. The samples were solubilized in EtOH 80% v/v to a 100 mg/mL concentration and stocked. For the analysis and experiments carried out, aliquots of Sample 1 were further diluted to a 10 mg/mL concentration with EtOH 80% v/v.

“Sample 2” is a chemically characterized commercial liquid extract provided by an Italian company and made from Chinese poplar propolis. It was the only liquid extract of all the ones tested. It is a EtOH 70% v/v solution made with 400 mg/mL of raw propolis that was further diluted with EtOH 80% v/v to a 10 mg/mL concentration.

“Sample 3” is a dry extract supplied by a second Italian company. It was dissolved in EtOH 80% v/v with an ultrasonic bath (30 minutes sonication) to obtain a 10 mg/mL concentrated solution.

“Sample 4” is a dry extract provided by a third Italian company with the peculiarity of being water soluble. It was diluted in water to a 10 mg/mL concentration, dissolved with an ultrasonic bath (30 minutes sonication).

All samples were filtered with syringe filters with pore size 0.45 μm and 0.2 μm before chemical and biological experiments respectively.

4.2. Phytochemical Analysis

Standard procedures were used to determine both the qualitative and quantitative phytochemical composition of the samples.

4.2.1. Total Phenolic Content

The Folin-Ciocâlteu (FC) colorimetric assay was used to determine the TPC, as described in Finetti et al, (2020) [

16]. Briefly, 20 μL of Samples 1, 2 and 3 and 100 μL of Sample 4 were diluted with distilled water to a final volume of 3 mL. 500 μL of FC reagent (Sigma-Aldrich

®, Milan, Italy), previously diluted 1:10 in distilled water, were added and the mixture was gently stirred; then, 1 mL of a 30%

w/

v aqueous solution of sodium carbonate was added. Mixtures were kept in the dark at room temperature for 15 minutes to stabilize the reaction, then poured into cuvettes. Pure ethanol and distilled water were used as blanks. The absorbance of the samples was determined at a wavelength of 760 nm with Shimadzu UV-Vis Spectrophotometer UV-1900i [

17].

The total phenolic content was determined using a calibration curve constructed with gallic acid (Sigma-Aldrich®; 0.25 – 5 mg/mL, R2 = 0.998). Results were expressed as % of total phenolics as GAE.

4.2.2. Total Flavonoid Content

The evaluation of the TFC was based on the absorbance of 250 μL of the diluted samples (1:200 EtOH 80%

v/

v) in a 96-wells plate at a wavelength of 353 nm, the maximum absorption wavelength of galangin which was used as standard. EtOH 80%

v/

v was used as blank. The absorbance reading was made with PerkinElmer VICTOR

® Nivo

TM Multimode Microplate Reader (Waltham, MA, USA)[

18].

The total flavonoid content was determined using a calibration curve constructed with galangin (0 – 20 µg/mL, R2 = 0.99). Results were expressed as % of total flavonoids as galangin equivalents.

4.2.3. Triterpenoid Content

A colorimetric assay based on the reaction of the samples with a vanillin solution in acetic acid and perchloric acid was employed to estimate the triterpenoids concentration. 10 μL of each sample were diluted with 190 μL of their extraction solvent and added of 300 μL of a 5%

w/

v solution of vanillin in glacial acetic acid. After stirring the mixture, 1 mL of perchloric acid was added, then the tubes were incubated at 60 °C for 45 minutes and later let to cool down at room temperature. The solutions were then added of 3.5 mL of glacial acetic acid and, after transferring 250 μL of each solution into a 96-wells plate, the absorbance was read at a wavelength of 540 nm with SAFAS Monaco microplate absorbance reader SAFAS MP96 [

19].

The triterpenoid content was calculated using a calibration curve constructed with β-sitosterol (Sigma-Aldrich®; 0 – 10 mg/mL, R2> 0.99). Results were expressed as % of terpenoids as β-sitosterol equivalents.

4.2.4. Chemical Characterization by HPLC-DAD

A more in-depth analysis of the phenolic and flavonoid contents of the four samples, focused on the main phytoconstituents of interest (pinobanksin, pinocembrin, CAPE, chrysin, and galangin), was carried out via HPLC-DAD using a Shimadzu Prominence-i LC-2030C 3D Plus instrument equipped with a Bondapak® C18 column, 10 µm, 125 Å, 3.9 mm × 300 mm (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA).A mixture of the solutions A) Formic acid 0.1% v/v in water and B) Formic acid 0.1% v/v in methanol were used as a mobile phase. The analysis method applied was: B) from 40% at 0.01 min to 65% at 12.00 min, 70% at 25.00 min, 75% at 30.00 min, 85% at 35.00 min, 40% at 39.00 min and stop at 45.00 min. Flow rate was set at 0.75 mL/min. Chromatograms were recorded at 280 nm.

Various quantities (0.5 – 5 μg) of the chosen standards (100 μg/mL diluted solutions) were used to obtain calibration curves to quantify the associated peaks in each sample (30 and 50 μg, 5 mg/mL diluted solutions). Compounds peaks were identified by comparing their retention times and UV spectra with those of the corresponding standards.

4.3. Biological Analysis

Excluding the assays concerning the antioxidant/scavenging activity and the ECM-degrading enzymes (cell-free), the biological tests carried out on the samples evaluated their toxicity and effects on cell lines of interest in the healing process. The final concentration of samples for the assays on cell lines was of 10 μg/mL for Samples 1, 2 and 3 and 100 μg/mL for Sample 4. Incubation of the cells used during the experiments took place in a humidified incubator at 37.0 °C and 5.0% CO2.

4.3.1. Scavenging Activity and Total Antioxidant Capacity

The DPPH and the ORAC assays allowed the evaluation of the scavenging and antioxidant activities of the samples, respectively.

In this study, the DPPH assay protocol already published in Bonetti et al. (2021) [

20] was employed, and PerkinElmer VICTOR

® Nivo

TM Multimode Microplate Reader to read the absorbance values.

The percentage of DPPH neutralization/inhibition was calculated from the absorbance data of the various concentrations of each sample using the formula % DPPH inhibition = [(A0 – A1)/A0] ∙ 100, where A0 and A1 are the absorbances of the control and the sample respectively. The scavenging activity was expressed as IC50, determined through linear regression.

The ORAC Antioxidant Capacity Assay Kit (KF01004, BQC Redox Technologies, Oviedo Asturias, Spain) was used to evaluate the TAC of the samples in this study. The experiment followed the protocol provided with the kit. The fluorescence (Ex.: 485 nm/Em.: 528 nm) was read for 30 minutes in intervals of 3 minutes using PerkinElmer VICTOR® NivoTM Multimode Microplate Reader.

The TAC was expressed as TEAC, determined using a calibration curve constructed with the Trolox from the assay kit.

4.3.2. Cell Lines

Aneuploid immortal keratinocytes from adult human skin (HaCaT) and Human Foreskin Fibroblasts (HFF) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) High glucose supplemented with 10% v/v Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% v/v penicillin/streptomycin solution. Media and material for cell cultures was supplied by Merck. Cells were maintained under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Human monocytic cell line (THP-1) was cultured using RPMI-1640 medium treated as the DMEM one (10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution). Viable cells count was performed using a hemocytometer after staining with Trypan Blue dye.

4.3.3. Cytotoxicity Assay

The Cell Counting Kit – 8 (CCK-8, 96992, Sigma-Aldrich®) was used to evaluate cell viability of HFF in response to the samples. The protocol of the assay was the one supplied with the kit.

Cells were seeded at a density of 5 ∙ 10

3 cells/well in 96-well plates. After 24 hours of incubation at 37 °C in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere, the medium was replaced with fresh DMEM containing 1% FBS and the designated treatments, including samples solution (10 μg/mL for Samples 1, 2, and 3, 100 μg/mL for Sample 4). The plates were then incubated again at 37 °C in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere for an additional 24 hours. After this period, the medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium containing 10%

v/

v CCK-8. The absorbance was measured, after ~ 30 minutes of incubation with the CCK-8 solution, using PerkinElmer VICTOR

® Nivo

TM Multimode Microplate Reader [

21].

4.3.4. Cell Migration and Proliferation Assay (Scratch Wound Healing Assay)

The procedure is a modified version of the one from Cappellucci et al. (2024) [

22]. In detail, HaCaT and HFF cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 50 000 cells/well with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and pre-incubated for 24 hours until ~ 80% confluence as a monolayer. Using a 1 ml pipette tip, the monolayer was scratched to create a cross in each well, then the medium and the detached cells were removed and DMEM supplemented with 3% FBS and the samples (10 μg/mL for Samples 1, 2, and 3, 100 μg/mL for Sample 4) were added in the wells. Photos of the crosses in each well were taken 0, 2, 6 and 24 hours after treatment by using a Leica DMIL microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

The size of the gap was evaluated using IC Measure software (The Imaging Source LLC, Version 2.0.0.286 [

23]. Accessed on 10 September 2024) by calculating the average of the diagonals of each cut. Confrontations were made between treated cuts with the healing of non-treated ones. The percentage of wound closure was calculated using the formula

% wound closure = [(

S0 –

St)/

S0] ∙ 100, where

S0 and

St are the areas of the wound at the beginning and after the time

t, respectively.

4.3.5. Quantifications through ELISAs

For the assays involving FGF-7 (RAB0188, Sigma-Aldrich®) and LAP (TGF-β1) (BMS2065, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), HFF cells (10 000 cells/well) were seeded into 24-well plates. After 24 hours of incubation, the cells were treated with 10 μg/mL of Samples 1, 2, and 3, and 100 μg/mL of Sample 4.

For the MMP9 (BMS2016-2, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) and IL-1β (88-7261, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) assays, HFF cells (10 000 cells/well) were also seeded into 24-well plates and incubated for 24 hours. Subsequently, the cells were co-treated with 10 μg/mL of Samples 1, 2, and 3, and 100 μg/mL of Sample 4, along with stimulation by LPS (1 µg/mL) and H2O2 (1.96 × 10⁻⁴ M) for 24 hours.

In the TNF-α (88-7346-22, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) and IL-8 (88-8086-22, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) assays, cytokine and chemokine quantification was performed using THP-1 cell cultures. The cells were co-treated with 10 μg/mL of Samples 1, 2, and 3, and 100 μg/mL of Sample 4, along with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 hours.

All treated and untreated cells underwent three freeze-thaw cycles at − 80 °C/+ 20 °C. ELISA assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A PerkinElmer VICTOR® NivoTM Multimode Microplate Reader was used for the analysis. (Governa et al., 2019; Cappellucci et al., 2024; Pressi et al., 2023)

4.3.6. Inhibition of ECM-Degrading Enzymes

The Collagenase Activity Colorimetric Assay Kit (MAK293, Sigma-Aldrich®) was used to determine the inhibition activity of the samples on these enzymes. Different volumes of each sample, corresponding to specific predetermined concentrations, were tested in this study. The samples were prepared by transferring each volume into two wells and adding 10 µL of provided Collagenase, while the positive control (2 wells) by inserting only 10 µL of Collagenase. The volume in each well was then adjusted to 100 µL with Collagenase Assay Buffer. The protocol was the one provided with the kit. The absorbance was read using a PerkinElmer VICTOR® NivoTM Multimode Microplate Reader.

The inhibition activity was determined using the differences in absorbance between the last and first measurements for each sample referred to the one of the non-treated enzymes. Through regression curves constructed for every sample, an approximate value of IC50 was calculated.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were conducted using either the unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA, with a significance level of p< 0.05. Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied for multiple comparisons where appropriate. All analyses and figures were generated using GraphPad Prism version 10.1 (San Diego, CA, USA).

4.5. In Silico Target Prediction

Computational analysis used for prediction and evaluation of possible molecular targets was based on the use of two free platforms available on the web.

SwissTargetPrediction is a platform developed by the Molecular Modeling Group of the SIB that based on the chemical and physical characteristics of the input, the similarities of the compounds and the data provided, the trained algorithm provides a functionality and relevance score, allowing the combination of query terms and providing relevant literature, on which the matching is based, also evaluating Tanimoto similarity calculations based on the compound annotations derived from ChEMBL [

11,

26].

Throughout the research process for this study, SwissTargetPrediction was used by inserting as query molecules the five main phenols of interest in propolis: pinobanksin, pinocembrin, CAPE, galangin, and chrysin.

GeneRecommender (TheProphetAI S.r.l. [

27]. Accessed on 10 September 2024) is a platform that makes use of a proprietary neural network called DeepProphet and relies on other prediction platforms such as GenaMANIA [

28], an interactive and visual online protein interaction prediction tool. GeneMANIA requires a list of gene queries to use available genomics and proteomics data to search for functionally similar genes to predict interacting genes for the target gene [

29,

30].

In this work, the chosen input genes, obtained from the previous analysis with SwissTargetPrediction, were: FLT4, PIK3CB, FGFR1, MMP2, MAPK1, HIF1A, MMP9, IKBKB, PIK3CG, MET, VEGFA, PDGFRB, PGF, PIK3CA, KDR, PDGFRA, IGF1R, EGFR, KIT, CXCR1, PIK3CD, MMP1, ELANE, and TLR9.

5. Conclusions

This work purpose was first to evaluate the chemical differences between four samples of poplar-type propolis deriving from different matrices. Then, moving onto the experimentation in the biological field, gauge the variability of the wound healing property of propolis, well established by literature, based on the composition of the samples material, while also confirming the main mechanisms of action underlying this activity.

The phytochemical analyses performed on the propolis samples showed the high variability due to various factors (mainly botanic and geographic), the high TPC in poplar propolis and the preponderance of flavonoids in it, which class represented more than two thirds of all the polyphenols complex in each matrix.

Pinocembrin was established, according to the literature, as the principal indicator of poplar propolis, followed by galangin and chrysin [

12,

15], while in other samples (2 and 3) the presence of CAPE was not detected, which absence can be explained by the hydrolysis of the molecule induced by industrial processes of extraction and purification. As a last thing about the chemical characterization, the experiments also highlighted the importance of adapting the extraction methodology based on the matrix of the starting material.

The first assays related to the biological field showed that propolis exhibited significant antioxidant activity, closely and easily linked to its high TPC.

The evaluation of the possible cytotoxicity of the in vitro tested concentration of the samples revealed that the propolis under study did not cause any particular disturbance in fibroblasts cultures, with differences in the recorded viability attributable to the intrinsic variability of the biological model. The scratching assay to evaluate the proliferative stimulation showed that, surprisingly, in both keratinocytes and fibroblasts cultures the treatments with propolis did not induce any particular improvement or degeneration of the healing process. The results of these experiments led to the conclusion that propolis has no direct effect on wound healing by stimulating the proliferation of major epithelial cells. On the other hand, interestingly, propolis showed indirect wound-healing properties by mitigating inflammation and remodeling (reduced IL-1β and MMP9) and potentially modulating the immune response (upregulated IL-8). In vitro studies confirmed these effects, demonstrating decreased MMP9 production and collagenase inhibition when cells were co-treated with propolis and a stressor. Propolis also suppressed IL-1β release in fibroblasts, although its impact on TNF-α was inconclusive. Notably, co-treatment upregulated IL-8 in monocytes, suggesting a potential immunomodulatory role. Therefore, we deduced that poplar propolis may not directly stimulate cell proliferation during wound healing, while its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties could suggest an indirect contribution to the process.

In conclusion, from a phytochemical point of view, this research work on four kinds of poplar-type propolis, derived from different varieties of matrices, confirmed the peculiar composition of this class regarding its TPC, TFC and presence of characteristic marker molecules, while also reflecting on the possible alterations caused by industrial processing and complications derived from the choice of the right extraction method. The biological side, instead, showed how the well-known wound healing activity of this substance is not related to a direct action as a stimulating agent on the proliferation of the epithelial cells, but instead can be traced back to an acceleration of the upstream inflammatory phase and a modulation of the downstream remodeling phase. Even so, it should be explored further the probable indirect stimulus on epithelial proliferation from the action of propolis on immunity and endothelial cells, possible sources of growth factors and other stimulating agents active on keratinocytes and fibroblasts, physiologically always in communication with each other.

Author Contributions

Elisabetta Miraldi: phytochemical analysis, project administration supervision, writing-original draft, review and editing. Alessandro Giordano: conceptualization and collection of the samples, phytochemical and biological analysis, writing original draft, review and editing. Giorgio Cappellucci: methodology, molecular docking investigation, writing original draft; review and editing. Federica Vaccaro: phytochemical analysis, validation, review and editing. Marco Biagi: conceptualization, formal analysis, original draft preparation. Giulia Baini: data curation, biological analysis, writing original draft, review and editing.

Funding

The research did not receive any financial support from external agencies.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

| CAPE |

Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| DPPH |

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ECM |

Extracellular matrix |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| FBS |

Fetal Bovine Serum |

| FGF-7 |

Keratinocytes growth factor |

| GAE |

Gallic Acid Equivalent |

| GF |

Growth factor |

| HPLC-DAD |

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode-Array Detection |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| LAP |

Latency Associated Peptide |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharides |

| MMP |

Matrix metalloprotease |

| NP |

Network Pharmacology |

| ORAC |

Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity |

| PBS |

Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| RPMI |

Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| RT |

Retention time |

| TAC |

Total Antioxidant Capacity |

| TEAC |

Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity |

| TFC |

Total Flavonoid Content |

| TGF |

Transforming Growth Factor |

| TNF |

Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| TPC |

Total Phenolic Content |

References

- Tottoli, E.M.; Dorati, R.; Genta, I.; Chiesa, E.; Pisani, S.; Conti, B. Skin Wound Healing Process and New Emerging Technologies for Skin Wound Care and Regeneration. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioce, A.; Cavani, A.; Cattani, C.; Scopelliti, F. Role of the Skin Immune System in Wound Healing. Cells 2024, 13, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governa, P.; Carullo, G.; Biagi, M.; Rago, V.; Aiello, F. Evaluation of the In Vitro Wound-Healing Activity of Calabrian Honeys. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sherbeni, S.A.; Negm, W.A. The wound healing effect of botanicals and pure natural substances used in in vivo models. Inflammopharmacol, 2023; 31, 755–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahri, G.; Badran, A.; Hijazi, A.; Daou, A.; Baydoun, E.; Nasser, M.; Merah, O. The Therapeutic Wound Healing Bioactivities of Various Medicinal Plants. Life 2023, 13, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criollo-Mendoza, M.S.; Contreras-Angulo, L.A.; Leyva-López, N.; Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Jiménez-Ortega, L.A.; Heredia, J.B. Wound Healing Properties of Natural Products: Mechanisms of Action. Molecules 2023, 28, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Pintado, M.; Tavaria, F.K. A systematic review of natural products for skin applications: Targeting inflammation, wound healing, and photo-aging. Phytomedicine 2023, 115, 154824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monavarian, M; Kader, S; Moeinzadeh, S; Jabbari, E. Regenerative Scar-Free Skin Wound Healing. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2019, 25, 294–311. [CrossRef]

- Moses, R.L.; Prescott, T.A.K.; Mas-Claret, E.; Steadman, R.; Moseley, R.; Sloan, A.J. Evidence for Natural Products as Alternative Wound-Healing Therapies. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Juan, Pi, Anjuan, Yan, Lele, Li, Juan, Nan, Sha, Zhang, Jing, Hao, Yuhui, Research Progress on Therapeutic Effect and Mechanism of Propolis on Wound Healing, Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2022, 5798941, 15 pages. [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, W357–W364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasote, D.; Bankova, V.; Viljoen, A.M. Propolis: chemical diversity and challenges in quality control. Phytochem Rev, 2022; 21, 1887–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, S.I.; Ullah, A.; Khan, K.A.; Attaullah, M.; Khan, H.; Ali, H.; Bashir, M.A.; Tahir, M.; Ansari, M.J.; Ghramh, H.A.; Adgaba, N.; Dash, C.K. Composition and functional properties of propolis (bee glue): A review. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2019, 26, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, R.; Quispe, C.; Khan, R.A.; et al. Propolis: An update on its chemistry and pharmacological applications. Chin Med 2022, 17, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezmirean, D.S.; Paşca, C.; Moise, A.R.; Bobiş, O. Plant Sources Responsible for the Chemical Composition and Main Bioactive Properties of Poplar-Type Propolis. Plants 2021, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finetti, F.; Biagi, M.; Ercoli, J.; Macrì, G.; Miraldi, E.; Trabalzini, L. Phaseolus vulgaris L. var. Venanzio Grown in Tuscany: Chemical Composition and In Vitro Investigation of Potential Effects on Colorectal Cancer. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, M.; Manca, D.; Barlozzini, B.; Miraldi, E.; Giachetti, D. Optimization of extraction: Of drugs containing polyphenols using an innovative technique. Agro Food Industry Hi Tech. 2014, 25, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sberna, G.; Biagi, M.; Marafini, G.; Nardacci, R.; Biava, M.; Colavita, F.; Piselli, P.; Miraldi, E.; D'Offizi, G.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Amendola, A. In vitro Evaluation of Antiviral Efficacy of a Standardized Hydroalcoholic Extract of Poplar Type Propolis Against SARS-CoV-2. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 799546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamponi, S.; Baratto, M.C.; Miraldi, E.; Baini, G.; Biagi, M. Chemical Profile, Antioxidant, Anti-Proliferative, Anticoagulant and Mutagenic Effects of a Hydroalcoholic Extract of Tuscan Rosmarinus officinalis. Plants 2021, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, A.; Faraloni, C.; Venturini, S.; Baini, G.; Miraldi, E.; Biagi, M. Characterization of phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of the leaves of the forgotten medicinal plant Balsamita major grown in Tuscany, Italy, during the growth cycle. Plant Biosystems - An International Journal Dealing with All Aspects of Plant Biology, 2020, 155, 908–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellucci, G.; Baini, G.; Miraldi, E.; Pauletto, L.; De Togni, H.; Raso, F.; Biagi, M. Investigation on the Efficacy of Two Food Supplements Containing a Fixed Combination of Selected Probiotics and β-Glucans or Elderberry Extract for the Immune System: Modulation on Cytokines Expression in Human THP-1 and PBMC. Foods 2024, 13, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellucci, G.; Paganelli, A.; Ceccarelli, P.L.; Miraldi, E.; Biagi, M. Insights on the In Vitro Wound Healing Effects of Sedum telephium L. Leaf Juice. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.theimagingsource.com/en-us/support/download/icmeasure-2.0.0.286/.

- Governa, P.; Cusi, M.G.; Borgonetti, V.; Sforcin, J.M.; Terrosi, C.; Baini, G.; Miraldi, E.; Biagi, M. Beyond the Biological Effect of a Chemically Characterized Poplar Propolis: Antibacterial and Antiviral Activity and Comparison with Flurbiprofen in Cytokines Release by LPS-Stimulated Human Mononuclear Cells. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressi, G.; Rigillo, G.; Governa, P.; Borgonetti, V.; Baini, G.; Rizzi, R.; Guarnerio, C.; Bertaiola, O.; Frigo, M.; Merlin, M.; et al. A Novel Perilla frutescens (L.) Britton Cell-Derived Phytocomplex Regulates Keratinocytes Inflammatory Cascade and Barrier Function and Preserves Vaginal Mucosal Integrity In Vivo. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigillo, G.; Cappellucci, G.; Baini, G.; Vaccaro, F.; Miraldi, E.; Pani, L.; Tascedda, F.; Bruni, R.; Biagi, M. Comprehensive Analysis of Berberis aristata DC. Bark Extracts: In Vitro and In Silico Evaluation of Bioaccessibility and Safety. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.generecommender.com/.

- http://www.genemania.org/.

- Brambilla, D.; Giacomini, D.M.; Muscarnera, L.; Mazzoleni, A. DeepProphet2 – a deep learning gene recommendation engine. arXiv (Cornell University). [CrossRef]

- Hu, LT.; Deng, WJ.; Chu, ZS.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of CXCR family members in lung adenocarcinoma with prognostic values. BMC Pulm Med 2022, 22, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

HPLC-DAD chromatograms (detection wavelength 280 nm) of A. Sample 1, B. Sample 2, C. Sample 3, and D. Sample 4. The arrows show the peaks of the main phytoconstituents of interest (red – pinobanksin; yellow – pinocembrin; green – CAPE; blue – galangin and chrysin).

Figure 1.

HPLC-DAD chromatograms (detection wavelength 280 nm) of A. Sample 1, B. Sample 2, C. Sample 3, and D. Sample 4. The arrows show the peaks of the main phytoconstituents of interest (red – pinobanksin; yellow – pinocembrin; green – CAPE; blue – galangin and chrysin).

Graphs 1.

Results of the cytotoxicity assay performed with CCK-8. Samples 1, 2, and 3 concentration 10 μg/mL, Sample 4 100 μg/mL.

Graphs 1.

Results of the cytotoxicity assay performed with CCK-8. Samples 1, 2, and 3 concentration 10 μg/mL, Sample 4 100 μg/mL.

Figure 2.

Microscopic images documenting the in vitro healing effect of the different samples (10 μg/mL for Sample 1, 2, and 3, 100 μg/mL for Sample 4) in human keratinocytes (HaCaT) through the scratch test.

Figure 2.

Microscopic images documenting the in vitro healing effect of the different samples (10 μg/mL for Sample 1, 2, and 3, 100 μg/mL for Sample 4) in human keratinocytes (HaCaT) through the scratch test.

Graphs 2.

Quantification of FGF-7 and LAP. Samples 1, 2, and 3 concentration 10 μg/mL, Sample 4 100 μg/mL. ** :p< 0.01 vs CTRL; *** : p< 0.001 vs CTRL.

Graphs 2.

Quantification of FGF-7 and LAP. Samples 1, 2, and 3 concentration 10 μg/mL, Sample 4 100 μg/mL. ** :p< 0.01 vs CTRL; *** : p< 0.001 vs CTRL.

Graphs 3.

Quantification of MMP9. Samples 1, 2, and 3 concentration 10 μg/mL, Sample 4 100 μg/mL, LPS 1 μg/mL, H2O2 1,96 ∙ 10-4 M. “Stresses” indicates the treatment with both LPS and H2O2. *** :p< 0.001 vs CTRL; # : p< 0.05 vs LPS + H2O2; ## : p< 0.01 vs LPS + H2O2; ### : p< 0.001 vs LPS + H2O2.

Graphs 3.

Quantification of MMP9. Samples 1, 2, and 3 concentration 10 μg/mL, Sample 4 100 μg/mL, LPS 1 μg/mL, H2O2 1,96 ∙ 10-4 M. “Stresses” indicates the treatment with both LPS and H2O2. *** :p< 0.001 vs CTRL; # : p< 0.05 vs LPS + H2O2; ## : p< 0.01 vs LPS + H2O2; ### : p< 0.001 vs LPS + H2O2.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the results obtained from the analysis with GeneMANIA.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the results obtained from the analysis with GeneMANIA.

Graphs 4.

Quantification of IL-1β. Samples 1, 2, and 3 concentration 10 μg/mL, Sample 4 100 μg/mL, LPS 1 μg/mL, H2O2 1,96 ∙ 10-4 M. “Stresses” indicates the treatment with both LPS and H2O2. ** :p< 0.01 vs CTRL; # : p< 0.05 vs LPS + H2O2; ### : p< 0.001 vs LPS + H2O2.

Graphs 4.

Quantification of IL-1β. Samples 1, 2, and 3 concentration 10 μg/mL, Sample 4 100 μg/mL, LPS 1 μg/mL, H2O2 1,96 ∙ 10-4 M. “Stresses” indicates the treatment with both LPS and H2O2. ** :p< 0.01 vs CTRL; # : p< 0.05 vs LPS + H2O2; ### : p< 0.001 vs LPS + H2O2.

Graphs 5.

Quantification of IL-8 and TNF-α. Samples 1, 2, and 3 concentration 10 μg/mL, Sample 4 100 μg/mL, LPS 100 ng/mL. *** :p< 0.001 vs CTRL; ## : p< 0.01 vs LPS; ### : p< 0.001 vs LPS.

Graphs 5.

Quantification of IL-8 and TNF-α. Samples 1, 2, and 3 concentration 10 μg/mL, Sample 4 100 μg/mL, LPS 100 ng/mL. *** :p< 0.001 vs CTRL; ## : p< 0.01 vs LPS; ### : p< 0.001 vs LPS.

Table 1.

Total Phenolic Content (TPC) of analyzed samples of propolis.

Table 1.

Total Phenolic Content (TPC) of analyzed samples of propolis.

| Sample |

GAE

(% w/w ± SD) |

| 1 |

21.13 ± 1.17 |

| 2 |

14.25 ± 0.57 |

| 3 |

18.50 ± 0.90 |

| 4 |

0.50 ± 0.06 |

Table 2.

Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) of analyzed samples of propolis.

Table 2.

Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) of analyzed samples of propolis.

| Sample |

Galangin Equivalents

(% w/w ± SD) |

| 1 |

19.68 ± 0.36 |

| 2 |

9.55 ± 0.23 |

| 3 |

13.09 ± 0.46 |

| 4 |

0.25 ± 0.20 |

Table 3.

Triterpenoid content of analyzed samples of propolis.

Table 3.

Triterpenoid content of analyzed samples of propolis.

| Sample |

β-sitosterol Equivalents

(% w/w ± SD) |

| 1 |

61.19 ± 0.60 |

| 2 |

43.15 ± 0.31 |

| 3 |

65.00 ± 0.64 |

| 4 |

2.74 ± 0.14 |

Table 4.

HPLC quantification of main flavonoids/phenols in samples.

Table 4.

HPLC quantification of main flavonoids/phenols in samples.

| Sample |

Pinobanksin

(% w/w± SD) |

Pinocembrin

(% w/w± SD) |

CAPE

(% w/w± SD) |

Galangin + chrysin

(% w/w± SD) |

| 1 |

1.46 ± 0.27 |

8.14 ± 1.40 |

1.93 ± 0.34 |

13.22 ± 2.25 |

| 2 |

0.66 ± 0.08 |

2.88 ± 0.42 |

< 0.01 |

8.60 ± 2.76 |

| 3 |

1.29 ± 0.05 |

3.68 ± 0.81 |

< 0.01 |

12.68 ± 2.23 |

| 4 |

0.31 |

0.03 |

< 0.01 |

0.02 |

Table 5.

DPPH test results.

Table 5.

DPPH test results.

| Sample |

IC50

(μg/mL ± SD) |

| 1 |

26.09 ± 1.30 |

| 2 |

54.38 ± 2.72 |

| 3 |

45.50 ± 2.28 |

| 4 |

> 1 000 |

Table 6.

ORAC assay results.

Table 6.

ORAC assay results.

| Sample |

Trolox Equivalents

(mM/g ± SD) |

| 1 |

8.89 ± 1.50 |

| 2 |

4.93 ± 2.21 |

| 3 |

6.96 ± 2.05 |

| 4 |

3.01 ± 1.79 |

Table 7.

SwissTargetPrediction MMPs matches.

Table 7.

SwissTargetPrediction MMPs matches.

| MMPs |

N° of matches with query molecules |

| MMP2 |

4 |

| MMP9 |

4 |

| MMP12 |

4 |

| MMP13 |

3 |

Table 8.

Collagenase inhibition activity.

Table 8.

Collagenase inhibition activity.

| Sample |

IC50

(μg/mL ± SD) |

| 1 |

41.61 ± 2.08 |

| 2 |

113.96 ± 5.70 |

| 3 |

51.57 ± 2.58 |

| 4 |

> 200 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).