Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strain Identification

2.2. Phage Isolation and Propagation

2.3. Phage Plaques and Phage Particles Morphology

2.4. Host Range Analysis of the Phage KlebP_265

2.5. Molecular Serotyping of K. pneumoniae Strains

2.6. Hypermucoidity and Antibiotic Resistance of Host Strains of the KlebP_265

2.7. Biological Properties of Phage KlebP_265

2.9. Thermal and pH Stability of KlebP_265

2.10. Phage DNA Purification and Complete Genome Sequencing

2.11. Analysis of Phage Genome

3. Results

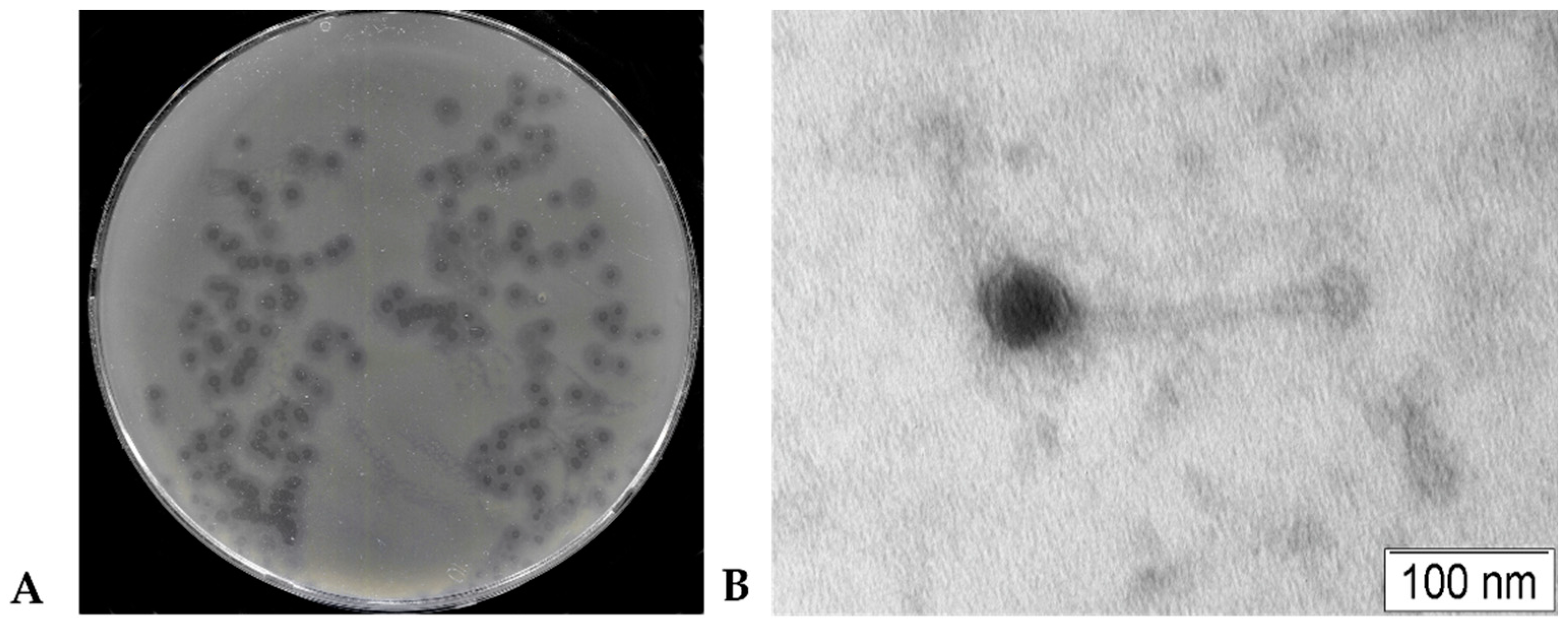

3.1. Phage KlebP_265 plaques and Phage Particles Morphology

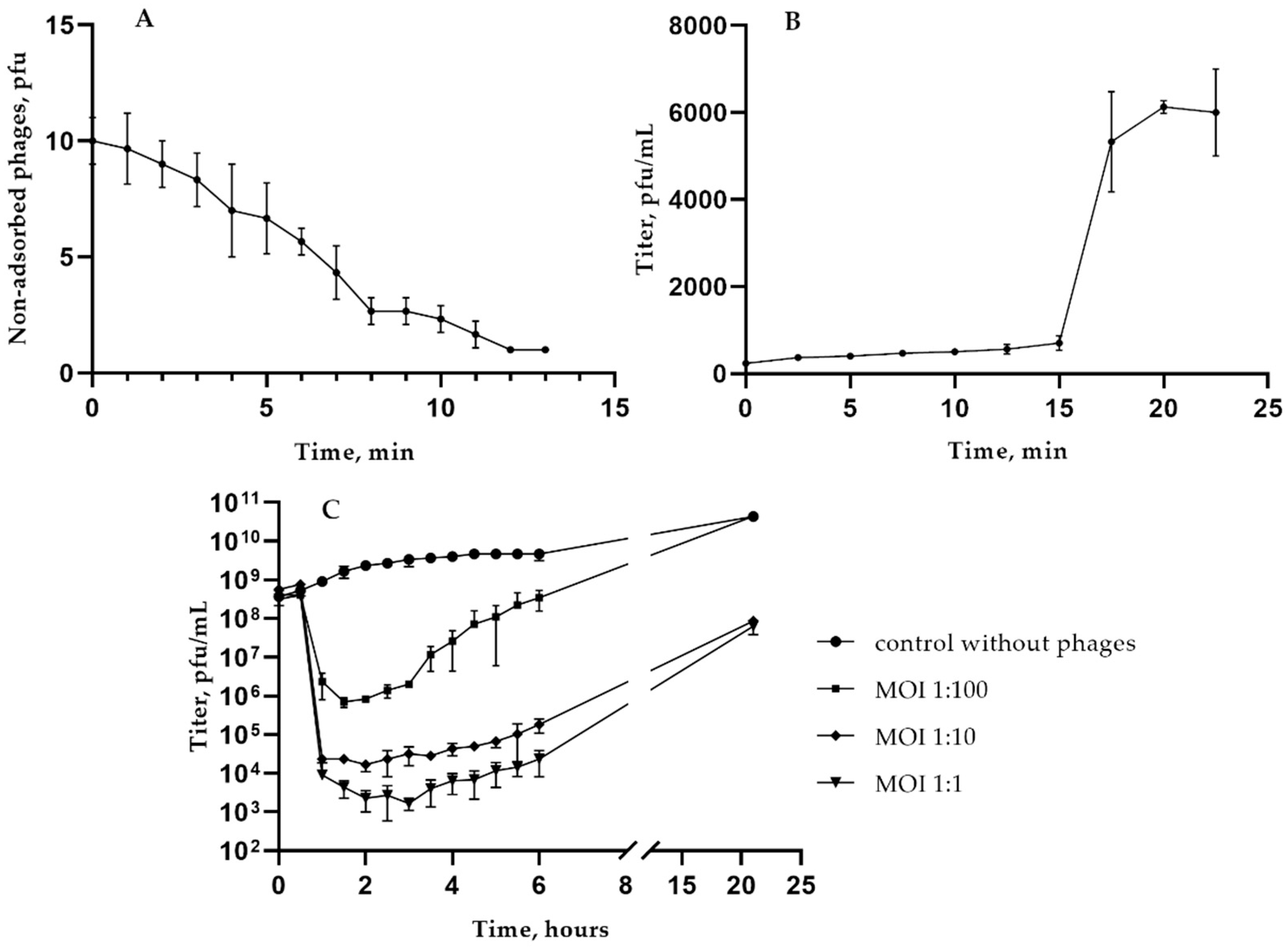

3.2. Biological Properties of KlebP_265

3.3. Host Range for the Phage KlebP_265

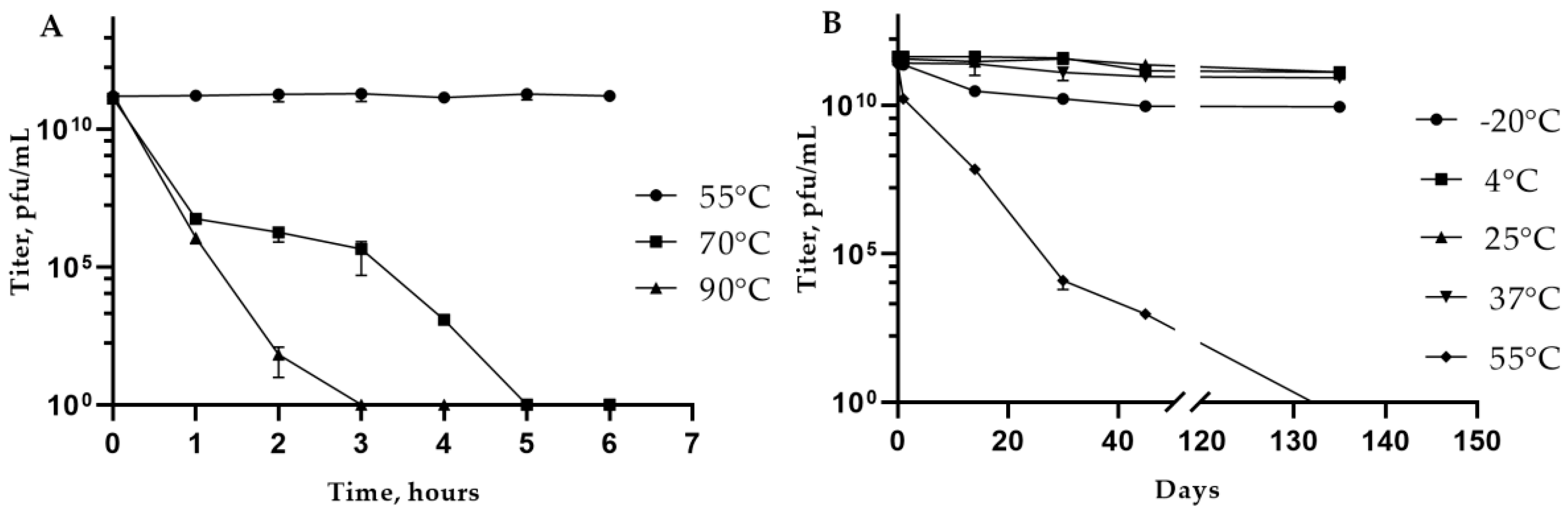

3.4. Phage KlebP_265: Temperature and pH Stability

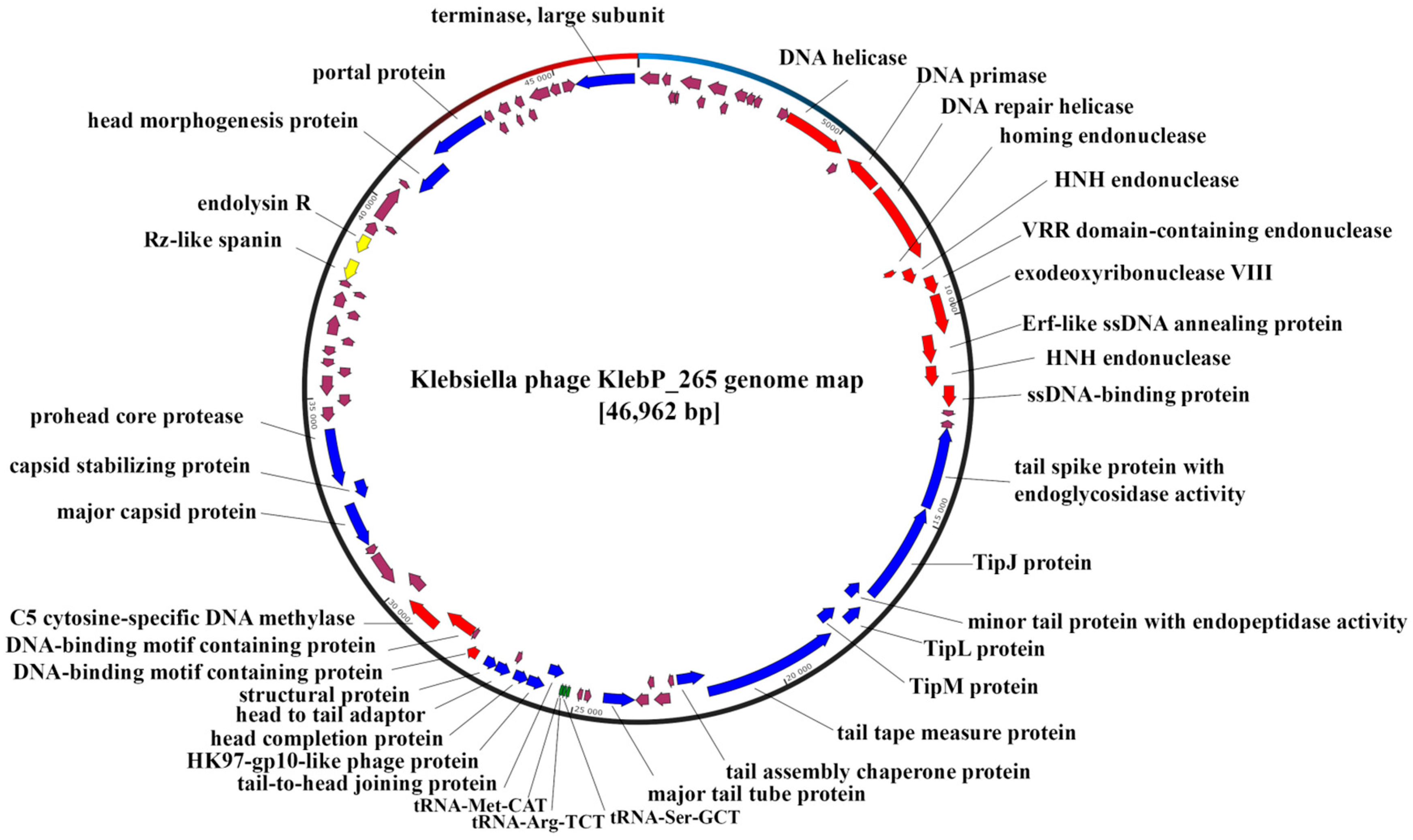

3.5. Annotation and Characterization of the KlebP_265 Genome

3.6. KlebP_265 Lytic Lifestyle Confirmation

3.7. Comparative Analysis of the Genome and Estimated Taxonomy of the KlebP_265 Phage

3.8. Phylogenetic Analysis of KlebP_265 Proteins

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, N.; Yang, X.; Chan, E.W.; Zhang, R.; Chen, S. Klebsiella species: Taxonomy, hypervirulence and multidrug resistance. EBioMedicine 2022, 79, 103998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, S.; Tang, L.; Chen, M.; An, Q. Proposal for reunification of the genus Raoultella with the genus Klebsiella and reclassification of Raoultella electrica as Klebsiella electrica comb. nov. Res Microbiol 2021, 172(6), 103851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyres, K.L.; Lam, M.M.; Holt, K.E. Population genomics of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat Rev Microbiol 2020, 18, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Priority List of Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics. Geneva: World Health Organization 2017.

- Navon-Venezia, S.; Kondratyeva, K.; Carattoli, A. Klebsiella pneumoniae: a major worldwide source and shuttle for antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2017, 41, 252–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederman, E.R.; Crum, N.F. Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: an emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol 2005, 100, 322–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.T.; Lai, S.Y.; Yi, W.C.; Hsueh, P.R.; Liu, K.L.; Chang, S.C. Klebsiella pneumoniae genotype K1: an emerging pathogen that causes septic ocular or central nervous system complications from pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Infect Dis 2007, 45, 284–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomakova, D.K.; Hsiao, C.B.; Beanan, J.M.; et al. Clinical and phenotypic differences between classic and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumonia: an emerging and under-recognized pathogenic variant. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012, 31, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guo, J. Characteristics of ventilator-associated pneumonia due to hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae genotype in genetic background for the elderly in two tertiary hospitals in China. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2018, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, T.A.; Marr, C.M. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Rev 2019, 32(3), e00001-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choby, J.E.; Howard-Anderson, J.; Weiss, D.S. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae - clinical and molecular perspectives. J Intern Med 2020, 287(3), 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, R.; Lambert, L.; Frazee, B. Invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae infections, California, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2010, 16, 1490–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, L.K.; Yeh, K.M.; Lin, J.C.; Fung, C.P.; Chang, F.Y. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 2012, 12, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.L.; Liu, Y.C. Yen, M.Y.; Liu, C.Y.; Wang, R.S. Septic metastatic lesions of pyogenic liver abscess. Their association with Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in diabetic patients. Arch Intern Med 1991, 151, 1557–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.S.; Chen, Y.S.; Tsai, H.C.; et al. Predictors of septic metastatic infection and mortality among patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess. Clin Infect Dis 2008, 47, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.T.; Chuang, Y.P.; Shun, C.T.; Chang, S.C.; Wang, J.T. A novel virulence gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains causing primary liver abscess and septic metastatic complications. J Exp Med 2004, 199, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, P.Y. Conservative fragments in bacterial 16S rRNA genes and primer design for 16S ribosomal DNA amplicons in metagenomic studies. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorodnichev, R.B.; Kornienko, M.A.; Kuptsov, N.S.; Efimov, A.D.; Bogdan, V.I.; Letarov, A.V.; Shitikov, E.A.; Ilyina, E.N. Comparison of purification methods of phage lysates of gram-negative bacteria for personalized therapy. Virology (Article in Russian) 2021, 23(3), 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, V.; Kozlova, Y.; Jdeed, G.; Tikunov, A.; Ushakova, T.; Bardasheva, A.; Zhirakovskaia, E.; Poletaeva, Y.; Ryabchikova, E.; Tikunova, N.V. A Novel Aeromonas popoffii Phage AerP_220 proposed to be a member of a new Tolavirus genus in the Autographiviridae family. Viruses 2022, 14, 2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutter, E. Phage host range and efficiency of plating. In: Clokie M.R.J., Kropinski A.M., editors. Bacteriophages: Methods and Protocols. Volume 1. Humana Press; New York, NY, USA: 2009, pp. 141–149.

- Fanaei, P.R.; Wagemans, J.; Kunisch, F.; Lavigne, R.; Trampuz, A.; Gonzalez, M.M. Novel Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bacteriophage as potential therapeutic agent. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisse, S.; Passet, V.; Haugaard, A.B.; Babosan, A. ; Kassis-Chikhani. N.; Struve, C.; Decré, D. Wzi gene sequencing, a rapid method for determination of capsular type for Klebsiella strains. J Clin Microbiol 2013, 51, 4073–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, L.P.P.; Sudhakar, K.U.; Rathinavelan, T. K-PAM: a unified platform to distinguish Klebsiella species K- and O-antigen types, model antigen structures and identify hypervirulent strains. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 16732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardasheva, A.V.; Fomenko, N.V.; Kalymbetova, T.V.; Babkin, I.V.; Chretien, S.O.; Zhirakovskaya, E.V.; Tikunova, N.V.; Morozova, V.V. Genetic characterization of clinical Klebsiella isolates circulating in Novosibirsk. Vavilovskii Zhurnal Genet Selektsii 2021, 25, 234–245, Russian. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropinski, A.M.; Mazzocco, A.; Waddell, T.E.; Lingohr, E.; Johnson, R.P. Enumeration of bacteriophages by double agar overlay plaque assay. In Bacteriophages: Methods and Protocols; Clokie, M.R.J., Kropinski, A.M., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Morozova, V. V, Yakubovskij, V.I.; Baykov, I.K.; Kozlova, Y.N.; Tikunov, A.Y.; Babkin, I.V.; Bardasheva, A.V.; Zhirakovskaya, E.V.; Tikunova, N.V. StenM_174: A Novel podophage that infects a wide range of Stenotrophomonas spp. and suggests a new subfamily in the family Autographiviridae. Viruses 2023, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, V. , Kozlova, Y., Shedko, E. et al. Lytic bacteriophage PM16 specific for Proteus mirabilis: a novel member of the genus Phikmvvirus. Arch Virol 2016, 161, 2457–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, M.; Han, P.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, F.; Li, M.; An, X.; Song, L.; Chen, Y.; Fan, H.; Tong, Y. Characterization and comparative genomics analysis of a new bacteriophage BUCT610 against Klebsiella pneumoniae and efficacy assessment in Galleria mellonella larvae. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes de novo assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overbeek, R.; Olson, R.; Pusch, G.D.; Olsen, G.J.; Davis, J.J.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Gerdes, S.; Parrello, B.; Shukla, M.; et al. The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, D206–D214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevillon, E.; Silventoinen, V.; Pillai, S.; Harte, N.; Mulder, N.; Apweiler, R.; Lopez, R. InterProScan: Protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33, W116–W120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söding, J.; Biegert, A.; Lupas, A.N. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33, W244–W248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, P.P.; Lin, B.Y.; Mak, A.J.; Lowe, T.M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49(16), 9077–9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garneau, J.R.; Depardieu, F.; Fortier, L.C.; Bikard, D.; Monot, M. PhageTerm: A tool for fast and accurate determination of phage termini and packaging mechanism using next-generation sequencing data. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Kuronishi, M.; Uehara, H.; Ogata, H.; Goto, S. ViPTree: the viral proteomic tree server. Bioinformatics 2017, 33(15), 2379–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraru, C.; Varsani, A.; Kropinski, A.M. VIRIDIC – a novel tool to calculate the intergenomic similarities of prokaryote-infecting viruses. Viruses 2020, 12(11), 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.; Seto, D.; Mahadevan, P. CoreGenes5.0: An Updated User-Friendly Webserver for the Determination of Core Genes from Sets of Viral and Bacterial Genomes. Viruses 2022, 14, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Moreira, B.; Vinuesa, P. GET_HOMOLOGUES, a versatile software package for scalable and robust microbial pangenome analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013, 79(24), 7696–7701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemm, P.; Stadler, P.F.; Lechner, M. Proteinortho6: pseudo-reciprocal best alignment heuristic for graph-based detection of (co-)orthologs. Front Bioinform 2023, 3, 1322477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018, 35(6), 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hockenberry, A.J.; Wilke, C.O. BACPHLIP: predicting bacteriophage lifestyle from conserved protein domains. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropinski, A.M. Measurement of the rate of attachment of bacteriophage to cells. In Bacteriophages: Methods and Protocols; Clokie, M.R.J., Kropinski, A.M., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, W.; Pell, L.G.; Bona, D.; Tsai, A.; Dai, X.X.; Edwards, A.M.; Hendrix, R.W.; Maxwell, K.L.; Davidson, A.R. Tail tip proteins related to bacteriophage λ gpL coordinate an iron-sulfur cluster. J Mol Biol 2013, 425(14), 2450–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinga, I.; Dröge, A.; Stiege, A.C.; et al. The minor capsid protein gp7 of bacteriophage SPP1 is required for efficient infection of Bacillus subtilis. Molecular Microbiology 2006, 61(6), 1609–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaban, Y.; Lurz, R.; Brasilès, S.; Cornilleau, C.; Karreman, M.; Zinn-Justin, S.; Tavares, P.; Orlova, E.V. Structural rearrangements in the phage head-to-tail interface during assembly and infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2015, 112(22), 7009–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Yao, X.; Han, G.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yong, K.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ren, M.; Cao, S. Isolation of Klebsiella pneumoniae phage vB_KpnS_MK54 and pathological assessment of endolysin in the treatment of pneumonia mice model. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 854908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, M.; Li, Y.; Han, P.; Lin, W.; Geng, R.; Qu, F.; An, X.; Song, L.; Tong, Y.; Zhang, S.; Cai, Z.; Fan, H. Genomic characterization of a new phage BUCT541 against Klebsiella pneumoniae K1-ST23 and efficacy assessment in mouse and Galleria mellonella larvae. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 950737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayez, M.S.; Hakim, T.A.; Zaki, B.M.; Makky, S.; Abdelmoteleb, M.; Essam, K.; Safwat, A.; Abdelsattar, A.S.; El-Shibiny, A. Morphological, biological, and genomic characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae phage vB_Kpn_ZC2. Virol J 2023, 20(1), 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, B.M.; Fahmy, N.A.; Aziz, R.K.; Samir, R.; El-Shibiny, A. Characterization and comprehensive genome analysis of novel bacteriophage, vB_Kpn_ZCKp20p, with lytic and anti-biofilm potential against clinical multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1077995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Dai, X.; Xiang, L.; Qiu, Y.; Yin, M.; Fu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L. Isolation and characterization of three novel lytic phages against K54 serotype carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1265011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Shen, M.; Ma, W.; Zhou, X.; Shen, J. ; LysZX4-NCA, a new endolysin with broad-spectrum antibacterial activity for topical treatment. Virus Res 2024, 340, 199296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickard, D.; Thomson, N.R.; Baker, S.; Wain, J.; Pardo, M.; Goulding, D.; Hamlin, N.; Choudhary, J.; Threfall, J.; Dougan, G. Molecular characterization of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi Vi-typing bacteriophage E1. J Bacteriol. [CrossRef]

- Paradiso, R.; Lombardi, S.; Iodice, M.G.; Riccardi, M.G.; Orsini, M.; Bolletti Censi, S.; Galiero, G.; Borriello, G. Complete Genome Sequences of Three Siphoviridae Bacteriophages Infecting Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis. Genome Announc 2016, 4(6), e00939-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yente, L.; Fang, L.; Xincheng, S.; Robert, L.; Vivian, W. Complete Genome Sequence of Escherichia coli Phage vB_EcoS Sa179lw, Isolated from Surface Water in a Produce-Growing Area in Northern California. Genome Announcements 2018, 6(27). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doore, S.M.; Schrad, J.R.; Dean, W.F.; Dover, J.A.; Parent, K.N. Shigella Phages Isolated during a Dysentery Outbreak Reveal Uncommon Structures and Broad Species Diversity. J Virol 2018, 92(8), e02117-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Shi, J.; Ma, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Isolation, characterization, and application of a novel specific Salmonella bacteriophage in different food matrices. Food Res Int 2018, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohren, M.; Xie, Y.; O'Leary, C.; Kongari, R.; Gill, J.; Liu, M. Complete Genome Sequence of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Siphophage Skate. Microbiol Resour Announc 2019, 8(27), e00541-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, I.Y.; Lee, C.; Song, W.K.; Jang, S.J.; Park, M.K. Lytic KFS-SE2 phage as a novel bio-receptor for Salmonella Enteritidis detection. J Microbiol 2019, 57(2), 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Mi, L.; Mi, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, X.; Tong, Y.; Bai, C. Complete Genome Sequence of IME207, a Novel Bacteriophage Which Can Lyse Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Salmonella. Genome Announc 2016, 4(5), e01015-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, N.S.; Lametsch, R.; Wagner, N.; Hansen, L.H.; Kot, W. Salmonella phage Akira, infecting selected Salmonella enterica Enteritidis and Typhimurium strains, represents a new lineage of bacteriophages. Arch Virol 2022, 167(10), 2049–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodea, M.G.E.; González-Villalobos, E.; Espinoza-Mellado, M.D.R.; Hernández-Chiñas, U.; Eslava-Campos, C.A.; Balcázar, J.L.; Molina-López, J. Genomic analysis of a novel phage vB_SenS_ST1UNAM with lytic activity against Salmonella enterica serotypes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2024, 109(3), 116305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Wang, X.; Huang, H.; Sun, Y.; Qian, X.; Xue, F.; Ren, J.; Dai, J.; Tang, F. Novel host recognition mechanism of the K1 capsule-specific phage of Escherichia coli: Capsular polysaccharide as the first receptor and lipopolysaccharide as the secondary receptor. J Virol 2021, 95, e0092021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Sun, H.; Ren, H.; Liu, W.; Li, G.; Zhang, C. LamB, OmpC, and the core lipopolysaccharide of Escherichia coli K-12 function as receptors of bacteriophage Bp7. J Virol 2020, 94, e00325-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Kropinski, A.M.; Adriaenssens, E.M. A Roadmap for genome-based phage taxonomy. Viruses 2021, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No | CEMTC number |

Species, GenBank ID |

wzi-allele (K-type), GenBank ID |

String test | Phage titer, pfu/mL | Relative EOP1 |

Resistance to antibiotics2 |

| 1 | 2067 |

K. pneumoniae, MT439057 |

2 (K2), MN371471 |

hpmuc | 1 × 105 | low | R |

| 2 | 2291 |

K. pneumoniae, MT439061 |

72 (K2), MN371475 |

hpmuc | 1.2 × 104 | low | R |

| 3 | 2335 |

K. pneumoniae, MT436848 |

N.d.3 | hpmuc | 1.1 × 103 | low | S |

| 4 | 2531 |

K. pneumoniae, MT436839 |

N.d.3 | – | 2 × 103 | low | R |

| 5 | 2554 |

K. pneumoniae, MT439068 |

2 (K2), MN371486 |

– | 9 × 103 | low | MDR |

| 6 | 2573 |

K. pneumoniae, MT439069 |

2 (K2), MN371483 |

– | 1.6 × 106 | low | MDR |

| 7 | 2945 |

K. pneumoniae, MT439080 |

2 (K2), MN371498 |

– | 4 × 106 | low | MDR |

| 8 | 3729 |

K. pneumoniae, MT489346 |

2 (K2), MT447747 |

– | 1 × 106 | low | R |

| 9 | 4065 |

K. pneumoniae, PQ571727 |

2 (K2), PQ609952 |

hpmuc | 4.5 × 1011 | high | MDR |

| 10 | 4087 |

K. pneumoniae, PQ571728 |

2 (K2), PQ609953 |

hpmuc | 7 × 109 | high | R |

| 11 | 4090 |

K. pneumoniae |

2 (K2) |

hpmuc | 3.5 × 1011 | high | R |

| 12 | 4117 |

K. pneumoniae, PQ571729 |

2 (K2), PQ69954 |

hpmuc | 4 × 105 | low | R |

| 13 | 4123 |

K. pneumoniae, |

2 (K2), PQ679255 |

– | 2.6 × 1011 | high | R |

| 14 | 4124 |

K. pneumoniae, |

2 (K2), PQ679256 |

hpmuc | 3.4 × 1011 | high | S |

| 15 | 4128 |

K. pneumoniae, PQ571730 |

2 (K2), PQ609955 |

– | 5.8 × 1011 | high | S |

| 16 | 4162 |

K. pneumoniae, PQ571731 |

2 (K2), PQ609956 |

hpmuc | 1.1 × 108 | medium | S |

| 17 | 4163 |

K. pneumoniae, OR544438 |

2 (K2), |

hpmuc | 1 × 104 | low | R |

| 18 | 4169 |

K. pneumoniae, PQ671057 |

72 (K2), PQ609957 |

– | 2 × 1011 | high | S |

| 19 | 52324 |

K. pneumoniae, PQ571733 |

2 (K2), PQ609958 |

– | 3.2 × 1011 | 1 | S |

| 20 | 5234 |

K. pneumoniae |

2 (K2) |

hpmuc | 3.7 × 1011 | high | S |

| 21 | 6827 |

K. pneumoniae, PQ571734 |

173 (-)5, PQ609959 |

– | 2 × 1011 | high | MDR |

| 22 | 6846 |

K. pneumoniae, PQ571735 |

2 (K2), PQ679259 |

– | 2 × 108 | low | MDR |

| 23 | 6848 |

K. pneumoniae, PQ571736 |

173 (-)5, PQ609960 |

– | 2 × 108 | low | MDR |

| 24 | 9609 |

K. pneumoniae, PQ571737 |

2 (K2), PQ609961 |

hpmuc | 3 × 1011 | high | R |

| 25 | 9874 |

K. pneumoniae, PQ571738 |

2 (K2), PQ609962 |

– | 4 × 104 | low | MDR |

| No | Protein (gene product1) | PutativeRoufvirinae | PutativeSkatevirinae | PutativeSkateviridae | |||

| Coregenes 5.0 (24)4 |

Protein- Otho6 (35)5 |

Coregenes 5.0 (20)4 |

Protein- Otho6 (27)5 |

Coregenes 5.0 (13)4 |

Protein- Otho6 (20)5 |

||

| 1 | HP2 (gp2) | + | |||||

| 2 | HP (gp7) | + | |||||

| 3 | HP (gp9) | + | + | ||||

| 4 | HP (gp10) | + | + | ||||

| 5 | DNA repair helicase (gp16) | + | + | + | + | ||

| 6 | VRR domain-containing protein (gp19) | + | + | + | |||

| 7 | ssDNA-binding protein (gp23) | + | |||||

| 8 | TipJ protein (gp27) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 9 | Minor tail protein with endopeptidase activity (gp28) | + | |||||

| 10 | TipL protein (gp29) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 11 | TipM protein (gp30) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 12 | Tape measure protein (gp31) | + | + | ||||

| 13 | Tail assembly chaperone (gp32) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 14 | HP (gp33) | + | |||||

| 15 | Major tail tube protein (gp37) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 16 | Tail-to-head joining protein (gp43) | + | + | + | + | ||

| 17 | HK97-gp10-like protein (gp44) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 18 | Head completion protein (gp45) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 19 | Head to tail adaptor (gp47) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 20 | Structural protein (gp48) | + | + | + | + | ||

| 21 | HP (gp55) | + | + | + | + | ||

| 22 | Major capsid protein (gp56) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 23 | Capsid stabilizing protein (gp57) | + | + | ||||

| 24 | Prohead core protease (gp58) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 25 | HP (gp59) | + | + | ||||

| 26 | HP (gp60) | ||||||

| 27 | HP (gp61) | + | + | ||||

| 28 | Lar-like restriction alleviation protein (gp62) | + | |||||

| 29 | HP (gp63) | + | |||||

| 30 | HP (gp64) | + | + | ||||

| 31 | HP (gp65) | + | + | + | + | ||

| 32 | DUF6378 domain-containing protein (gp66) | + | + | ||||

| 33 | Endolysin R (gp72) | + | + | + | + | ||

| 34 | HP (gp73) | + | + | ||||

| 35 | HP (gp74) | + | |||||

| 36 | Head morphogenesis protein (gp77) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 37 | Portal protein (gp78) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 38 | InsA C-terminal domain protein (gp86) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 39 | Phosphatase (gp87) | + | + | ||||

| 40 | Lipoprotein (YP_010053329.1)3 | + | |||||

| 41 | Holin (YP_010053300.1) 3 | + | + | ||||

| 42 | Endolysin (YP_010053299.1)3 | + | + | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).