1. Introduction

Osseointegration is defined as a functional and structural link between living bone tissue and the surface of an implant without fibrous tissue [

1]. Osseointegrated dental implant-aided dentures are widely used and scientifically applied in the therapy of complete and partial toothlessness[

1]. The quality and quantity of the implanted bone are important in dental implant-aided prosthetic therapy[

1]. Therefore, low bone quality in patients reduces the success rate of treatment[

1]. To solve this problem, various recent studies have sought to increase the bone-implant connection (BIC) during and after implant surgery[

2,

3,

4].The survival and success of dental implants are directly related to the primary stability. Primary stabilization (PS) is defined asinitial rigid stability during the surgical placement of an implant and is necessary for successful osseointegration. Primary stabilization depends on the quality of the bone tissue in which the implant is placed, the implant thread design and the surgical technique. However, it is quite difficult to achieve PS, especially in cases where the bone quality and quantity are inadequate[

2,

3,

4]. It has become necessary to develop effective treatment options to improve implant osseointegration in patients who actively need dental implants and where primary stabilization cannot be achieved.

Studies have shown that strontium ranelate has positive effects on osteoblast production and has an inhibitory effect on osteoclasts[

5,

6].Due to these desirable properties, we proposed that strontium ranelate could be used to increase osseointegration and improve dental treatment[

5,

6].

Strontium ranelate consists of ranelic acid and two stable strontium ions. Strontium is similar to calcium in its ionic properties and participates in bone mineralization[

3,

7,

8,

9]. Strontium ranelate increases the synthesis of collagenous and non-collagenous proteins by stimulating the division of osteoblast precursors and, at the same time, supports bone formation (osteogenesis) by reducing osteoclast differentiation and activity,thereby reducing bone resorption[

3,

7,

8,

9]. The clinical use of strontium ranelate for the therapy and prevention of osteoporosis has shown positive effects, such as a decreased risk of bone fracture and increased bone mineral density[

3,

7,

8,

9].

Strontium ranelate has strong potential for use to treat osteoporosis as an anti-osteoporotic drug[

10,

11].Strontium ions, which have a high affinity for the bone mineral hydroxyapatite, can replace Ca++-ions in the hydroxyapatite crystal structure through ionic substitution or surface interchange[

12,

13,

14]. Strontium ions’ effects on cellular mechanisms, such as the inhibition of osteoclast differentiation and stimulation of osteoblast proliferation, are due to the positive effects of strontium[

15,

16,

17,

18]. Previous studies have shown that strontium ranelate decreases bone resorption by stopping osteoclastic activity in osteoporotic rats and increases the rate of new bone formation, thus preventing bone resorption[

10,

19,

20]. Strontium ranelate has also shown a positive effect during the therapy of women with postmenopausal osteoporosis[

12,

21].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Study Design

The experimental and operational work was carried out at the experimental research center of Firat University, Elazig, Turkiye. The ethical protocol was revised and approved by the Animal Experiments Ethics Committee of Firat University (Date and Protocol No: 04 March 2022, 7301). The experimental animals used in our investigation were taken from the experimental research center atFirat University. The care and welfare of the experimental animals were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

In this investigation, 44 female SpragueDawley rats, which were aged between 1 and 1.5 years, from the same estrus period, and weighing 300-330 g, were used. During the study, these experimental animals were hosted in temperature-monitored cages in a 12-hour dark and 12-hour light environment. All the experimental animals had free access to water and food during the investigation.

The animals were randomly divided into four groups, each with eleven rats. The experimental groups included; a control group with primary stabilization (PS+) (n=11), a strontium ranelate group with primary stabilization (PS+STR) (n=11), a control group without primary stabilization (PS-) (n=11), and a strontium ranelate group without primary stabilization (PS-STR) (n=11).

2.2. Surgical Procedures

All the surgical procedures were performed under sterile conditions and general anesthesia. General anesthesia (with 5 mg/kg/im ketamine hydrochloride and 50 mg/kg/im xylazine) was performed. After the right tibial bone surface of the rats was shaved, the obtained sample was washed with povidone iodine. A linear incision 1.5-2 cm in length was made on the tibial crest. After the marking bur, using a 1.8 mm diameter drill, the sockets of the implants were formed to achieve primary stabilization. In the nonprimary stabilized implants, the sockets were prepared with a point drill, using 1.8 mm, 2.3 mm and 2.8 mm diameter drills. In the implants without primary stabilization, attention was paid to the vertical and rotational movements of the implants in the socket and the implants were placed without force. In the PS+ groups, the implants were placed with a force of 15 N/cm.All the implants(Implance Dental Implant Systems, AGS Medical Corporation, Istanbul, Turkiye) placed into the rat tibias were 2 mm in diameter and 4 mm in length. All the implants had machined surfaces and were made from grade 4 titanium.After implant placement, the muscles, soft tissues and tibial skin were sutured in their original position with 4-0 absorbable sutures (polyglactin). Tramadol hydrochloride (0.1 mg/kg) (analgesic) and penicillin (50 mg/kg) (antibiotic) were administered for 3 days to reduce post-operative pain and prevent infection. In the PS+STR and PS-STR groups, strontium ranelate was administered daily by means of oral gavage during the two week trial, at 625 mg/kg. All the surgical procedures in the study were performed by the same surgeon.

At the end of the fourteen-day experimental treatment, the rats were sacrificed after the implants had been taken from the surrounding soft tissues, and the biomechanical BIC levels were analysed using the reverse torque method.

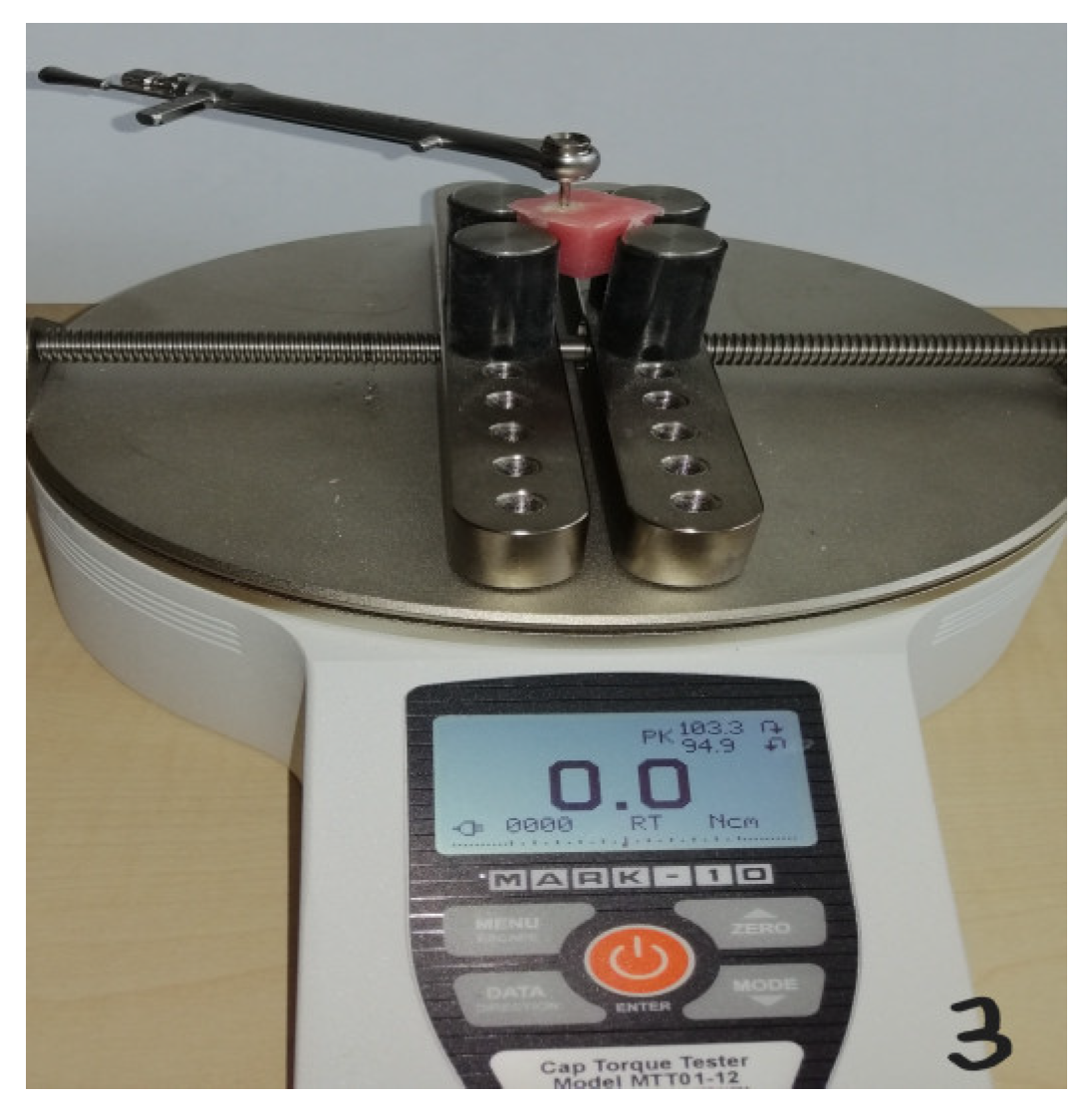

2.3. Biomechanical Analysis

No fatal or nonfatal complications were encountered during the study. The implant parts, along with the surrounding bone tissues(including the entire metaphyseal part of the tibia bone), were prepared as blocks and kept in a 10% buffered formalin solution. All implants were immediately placed in polymethylmethacrylate blocks to prevent dehydration. A rotating apparatus was used to measure the torque of the implants. A digital torque instrument (Mark 10, NY, USA) was used to apply an extraction force manually, slowly, and incrementally counterclockwise. The procedure was completed as soon as the dental implant returned to the bone socket. The maximum torque force (N/cm) measured during the first rotation of the implant in the socket was automatically recorded. Reverse torque analyses were performed assuming that the reverse torque application would reveal objective bone-implant integration after healing.

Figure 1.

Surgical integration of the titanium implants of the tibia after the skin incision.

Figure 1.

Surgical integration of the titanium implants of the tibia after the skin incision.

Figure 2.

Titanium implants and surrounded bone tissues after the samples collection.

Figure 2.

Titanium implants and surrounded bone tissues after the samples collection.

Figure 3.

Biomechanical reverse torque analysis.

Figure 3.

Biomechanical reverse torque analysis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 22 program. The compatibility of the study’s parameters with a normal distribution was checked with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare parameters that were not normally distributed between groups. The difference between the groups was determined using the Mann-Whitney U test. A difference was considered significant at the p<0.05 level.

3. Results

The biomechanical BIC (N/cm) parameters according to the reverse torque analysis for the test and control groups are shown in

Table 1. The mean BIC ratio in the control group with PS+ was 3.73 N/cm, whereas it was 6.9 N/cm in the strontium ranelate group with primary stabilization (PS+STR). The PS+STR group was statistically significantly different compared with the PS+ group (P<0.05). The mean BIC ratio in the control group without primary stabilization (PS-) was 2.02 N/cm, whereas it was 2.84 N/cm in the PS-STR group. The PS-STR group was statistically significantly different compared with the PS- group (P<0.05). It was observed that systemic strontium administration increased the osseointegration levels in both the PS+ and PS- groups compared to the control groups (P<0.05). It was observed that the osseointegration in the samples with primary stabilization was higher than that in the samples without primary stabilization (P<0.05).

4. Discussion

The results of this investigation show that systemic strontium administration moderately improves implant osseointegration and peri-implant bone quality. Similar to thosein the current study, positive effects of strontium application on peri-implant bone tissue and implant osseointegration have been observed in studies conducted on healthy animals and osteoporotic animals using various methods, such as serum analysis, biomechanics, histomorphometry, nanoindentation and microtomography [

9,

11,

12,

13].

In rats, it is not known when strontium treatment should be started and for how long it should last for the strontium ranelate to promote bone healing [

21]. Therefore, the results of these studies may have varied depending on when the strontium treatment was initiated, the duration of the treatment and the dose used [

21]. Previous studies on this subject have shown that strontium can both suppress bone resorption and induce new bone formation [

22,

23]. Recent animal studies have shown that the systemic administration of strontium ranelate can increase implant osseointegration [

22,

23]. Ammann et al.[

22] studied untouched female rats that were treated with varied doses of strontium ranelate (0, 225, 450 and 900 mg/kg/day) for 2 years, and healthy female/male rats cured with strontium ranelate at 625 mg/kg/day for the same period of time. The experiment showed dose-dependent increases in bone strength and bone mass without changes in the bone stiffness of the vertebral body, which predominantly includes trabecular bone, and the mid-shaft femur, which mainly includes cortical bone [

22]. Farlay et al.[

23]studied the links of strontium with bone mineral levels after long-term strontium ranelate therapy and the discontinuation of the therapy for a while in their study on monkeys, where they proved that long-term strontium ranelate therapy did not have a harmful effect on bone mineralization. At the end of the 52 week oral administration of 200, 500 and 1250 mg/kg/day strontium ranelate and 10-week period after discontinuation in parallel groups, the intake and deployment of strontium in iliac bones were investigated [

23]. After the administration of strontium ranelate, dose-dependent strontium intake occurred in the cortical and cancellous bones, being 1.6 times higher in newly formed bone tissue than in the previous bone tissue [

23]. Strontium intake has been reported to decrease by 50% 10 weeks after the discontinuation of the therapy [

23]. This study showed that the long-term administration of strontium ranelate results in a dose-dependent increase in bone strontium intake (mainly in newly formed bone), which protects bone mineral levels and promotes bone mineralization at a crystalline level [

23].

Maimoun et al. [

24] placed titanium implants in the proximal tibias of 30 six-month-old female Sprague Dawley rats. For 8 weeks following the implant surgery, strontium ranelate (625 mg/kg/day) or vehicle with saline was administered orally 5 days per week[

24]. The results showed that strontium ranelate significantly increased the pull-out strength compared to that in the control group (+34%) [

24]. Linderbäck et al. [

25] in an animal study studying the effects of strontium ranelate and bisphosphonate on implant fixation, showed that strontium ranelate did not improve implant fixation compared to that in the control group, but bisphosphonate did markedly improve implant fixation compared to that in the control group [

25].

The same research group studied female rats with ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis(OVX); rats receiving high doses (1000 mg/kg) of strontium ranelate daily showeda higher(1.9 fold)rate of total voxel and bone in direct contact with the implant compared to a non-OVX-supplemented group [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Animals receiving lower doses (500 mg/kg) showed improved implant osseointegration compared to those receiving no strontium ranelate, but there was no improvement in bone quality-associated parameters when compared with a group receing alendronate and zolendronate (bisphosphonates) [

26,

28]. Despite the toxic effects at high doses, in preclinical studies by Ammann et al., significant increases in serum bone-alkaline phosphatase (b-ALP) (+53% p < 0.001), a marker of bone formation, were detected in rats administered 625 and 900 mg/kg/day strontium ranelate for 2 years, accompanied by increases in bone volume and bone strength (maximum load) [

19,

22]. In addition, Bain et al. [

15] reported in their study on ovariectomized rats that strontium ranelate given at a dose of 625 mg/kg per day for 52 weeks prevented OVX-induced deterioration of biomechanical properties and bone loss by affecting the bone strength determinants. The researchers did not detect any osteonecrosis in the rats at the end of the studies.The dose applied in this animal study was also determined by taking the study by Ammann et al. as a reference [

15,

19,

22].

5. Conclusions

In this limited investigation, the lowest osseointegration was observed in the PS- group. It can be stated that primary stabilization is important. This study showed that the application of strontium ranelate may increase the osseointegration of implants with and without initial stabilization. In addition, it was observed that the strontium doses administered in this study did not cause osteonecrosis in any of the experimental animals. It can be considered that data obtained from studies conducted with different clinical scenarios at different doses will reveal the relationship between strontium ranelate-osteonecrosis. Further animal studies are needed to research the mechanisms by which strontium ranelate impacts the BIC and should evaluate the potential risks/benefits of strontium ranelate use.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, I.A. and S.D.; methodology, I.A. and S.D.; software, I.A. and S.D.; validation, I.A. and S.D.; formal analysis,I.A. and S.D.; investigation, I.A. and S.D.; resources, I.A. and S.D.; data curation, I.A. and S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A. ; writing—review and editing, I.A. and S.D.; visualization, I.A. and S.D.; supervision, I.A. and S.D.; project administration, I.A. and S.D.; funding acquisition, I.A. and S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors of the study would like to thank Implance Dental Implant Systems-AGS Medical Corporation located in Istanbul, Turkey

References

- Acikan I, Dundar S. Biomechanical Examination of Osseointegration of Titanium Implants Placed Simultaneously With Allogeneic Bone Transfer. J Craniofac Surg. 2022;33(1):350-353.

- Dundar S, Bozoglan A. Evaluation of the effects of topically applied simvastatin on titanium implant osseointegration. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2020;10(2):149-152.

- Dundar S, Yaman F, Gecor O, Cakmak O, Kirtay M, Yildirim TT, et al. Effects of Local and Systemic Zoledronic Acid Application on Titanium Implant Osseointegration: An Experimental Study Conducted on Two Surface Types. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28(4):935-938.

- Dundar S, Yaman F, Saybak A, Ozupek MF, Toy VE, Gul M, et al. Evaluation of Effects of Topical Melatonin Application on Osseointegration of Dental Implant: An Experimental Study. J Oral Implantol. 2016;42(5):386-389.

- Matvieienko LM, Matvieienko RY, Fastovets OO. Effects of strontium ranelate on alveolar bone in rats wıth experimental diabetes mellitus. Wiad Lek. 2022;75(1 pt 2):151-155.

- Gonçalves FC, Mascaro BA, Scardueli CR, de Oliveira GJPL, Spolidorio LC, Marcantonio RAC. Strontium ranelate improves post-extraction socket healing in rats submitted to the administration of bisphosphonates. Odontology. 2022;110(3):467-475.

- Gusman DJ, Matheus HR, Alves BE, Ervolino E, de Araujo NJ, Piovezan BR, Fiorin LG, de Almeida JM. Influence of systemic strontium ranelate on the progression and as adjunctive therapy for the nonsurgical treatment of experimental periodontitis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2021;13(12):e1239-e1248.

- Falgayrac G, Farlay D, Ponçon C, Béhal H, Gardegaront M, Ammann P, Boivin G, Cortet B. Bone matrix quality in paired iliac bone biopsies from postmenopausal women treated for 12 months with strontium ranelate or alendronate. Bone. 2021;153:116107.

- Marx D, Rahimnejad Yazdi A, Papini M, Towler M. A review of the latest insights into the mechanism of action of strontium in bone. Bone Rep. 2020;12:100273.

- Ammann, P. Strontium ranelate: a physiological approach for an improved bonequality. Bone. 2006;38:15–18.

- Blake GM, Fogelman I. Strontium ranelate: a novel treatment for postmenopausalosteoporosis: a review of safety and efficacy. Clin Interv Aging. 2006;1:367–375.

- Reginster JY, Felsenberg D, Boonen S, Diez-Perez A, Rizzoli R, Brandi ML, et al.Effects of long-term strontium ranelate treatment on the risk of nonvertebral and vertebral fractures in postmenopausal osteoporosis: results of a five-year, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1687–1695.

- Likins RC, Posner AS, Kunde ML, Craven DL. Comparative metabolism of calciumand strontium in the rat. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;83:472–481.

- Dahl SG, Allain P, Marie PJ, Mauras Y, Boivin G, Ammann P, et al. Incorporation anddistribution of strontium in bone. Bone. 2001;28:446–453.

- Bain, S.D. , Jerome C., Shen V., Dupin-Roger I., Ammann P. Strontium ranelate improves bone strength in ovariectomized rat by positively influencing bone resistance determinants. Osteoporos. Int. 2009;20(8):1417–1428. [CrossRef]

- Bonnelye E, Chabadel A, Saltel F, Jurdic P. Dual effect of strontium ranelate: stimulation of osteoblast differentiation and inhibition of osteoclast formation andresorption in vitro. Bone. 2008;42:129–138.

- Canalis E, Hott M, Deloffre P, Tsouderos Y, Marie PJ. The divalent strontiumsalt S12911 enhances bone cell replication and bone formation in vitro. Bone. 1996;18:517–523.

- Quarles, LD. Cation sensing receptors in bone: a novel paradigm for regulatingbone remodeling? J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1971–1974.

- Ammann P, Badoud I, Barraud S, Dayer R, Rizzoli R. Strontium ranelate treatmentimproves trabecular and cortical intrinsic bone tissue quality, a determinant of bone strength. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1419–1425.

- Marie PJ, Hott M, Modrowski D, De Pollak C, Guillemain J, Deloffre P, et al. Anuncoupling agent containing strontium prevents bone loss by depressing bone resorption and maintaining bone formation in estrogen-deficient rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:607–615.

- Meunier PJ, Roux C, Seeman E, Ortolani S, Badurski JE, Spector TD, et al. The effectsof strontium ranelate on the risk of vertebral fracture in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:459–468.

- Ammann P, Shen V, Robin B, Mauras Y, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R. Strontium ranelate improves bone resistance by increasing bone mass and improving architecture in intact female rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2004 Dec;19(12):2012-2020.

- Farlay D, Boivin G, Panczer G, Lalande A, Meunier PJ. Long-term strontium ranelate administration in monkeys preserves characteristics of bone mineral crystals and degree of mineralization of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(9):1569-1578.

- Maimoun L, Brennan TC, Badoud I, Dubois-Ferriere V, Rizzoli R, Ammann P. Strontium ranelate improves implant osseointegration. Bone. 2010;46:1436–1441.

- Linderback P, Agholme F, Wermelin K, Narhi T, Tengvall P, Aspenberg P. Weak effect of strontium on early implant fixation in rat tibia. Bone. 2012;50:350–356.

- Chen B, Li Y, Yang X, Xu H, Xie D. Zoledronic acid enhances bone-implant osseointegration more than alendronate and strontium ranelate in ovariectomized rats. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2115–2121.

- Li Y, Feng G, Gao Y, Luo E, Liu X, Hu J. Strontium ranelate treatment enhances hydroxyapatite-coated titanium screws fixation in osteoporotic rats. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:578–582.

- Li Y, Li X, Song G, Chen K, Yin G, Hu J. Effects of strontium ranelate on osseointegration of titanium implant in osteoporotic rats. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23:1038–1044.

- Glosel B, Kuchler U, Watzek G, Gruber R. Review of dental implant rat research models simulating osteoporosis or diabetes. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2010;25:516–524.

Table 1.

Biomechanical BIC (N/cm) parameters of the groups according the reverse torque analysis.

Table 1.

Biomechanical BIC (N/cm) parameters of the groups according the reverse torque analysis.

| Groups |

N |

Mean (N) |

Minimum (N) |

Maximum |

P* Value |

|

|

| PS+ |

11 |

3.73 |

3 |

5.1 |

0.000 |

|

|

| PS+STRa1 |

11 |

6.9 |

4.1 |

10.1 |

0.000 |

|

|

| PS-a2,b1 |

11 |

2.02 |

0.9 |

2.8 |

0.000 |

|

|

| PS-STRa3,b2,c |

11 |

2.84 |

1.3 |

3.5 |

0.000 |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).