1. Introduction

Pilot fatigue constitutes a well-acknowledged risk to aviation safety. Regulatory organizations around the world such as the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) have imposed rules to address ways in which fatigue can be limited during operations [

1,

2]. The bulk of research on fatigue in aviation has concentrated on long haul (L-H) operations, during which pilots must cross multiple time zones [

3,

4,

5]. Because jet lag and nighttime operations are major fatigue factors for L-H [

6], fatigue in aviation is routinely viewed as an issue resulting solely from sleep deprivation or circadian disruption.

Recent research has begun to investigate sources of fatigue during short haul (S-H) or medium haul (M-H) operations as well [

7,

8,

9]. M-H operations are typified by multiple flight segments per day lasting longer than 3 hours but less than 8 hours each, and crossing less than three time zones [

10,

11]. The typical pattern of M-H operations can vary depending on the region of operation or routes provided by a specific airline. For example, M-H operations in the United States may routinely include east/west travel that crosses multiple time zones whereas M-H operations in European carriers may be predominantly north/south routes that do not cross time zones. In these cases, fatigue may be due to factors such as schedule timing and workload factors rather than jet lag [

6,

10,

11,

12].

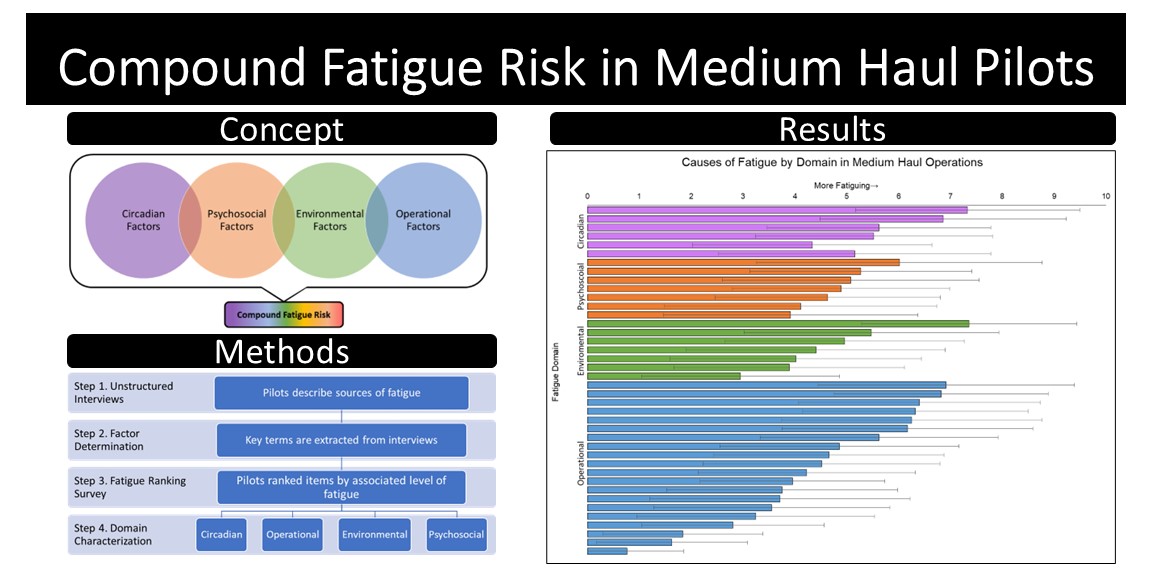

Fatigue factors from different domains are not mutually exclusive. As an example, a pilot may experience fatigue in the circadian domain when schedules include work that overlaps with periods of low circadian arousal, such as early mornings, late evenings, or overnight flights. Pilots may experience operational fatigue when schedules involve long duty hours, multiple flight legs, or short sit times. Environmental fatigue may arise from foul weather conditions or the ambient environment within the cockpit, including noise or temperature. Finally, psychosocial fatigue can occur because of stress, frustration, or human relations, such as working with an uncooperative co-pilot. The COVID-19 pandemic impacted flight operations and could have constituted a significant source of fatigue independently from infection with the virus, for example, stress related to wearing an uncomfortable face mask for hours on end in the cockpit.

Incremental amounts of fatigue from each fatigue domain may combine to create a greater overall compound fatigue risk in M-H aviation, but the impact of compound fatigue risk on operational safety has not been addressed. Prospective fatigue evaluation tools like biomathematical models of fatigue (BMMF) historically have predicted risk within the circadian domain (in addition to sleep history) but do not consider fatigue arising from the other domains, or compound fatigue risk. Most BMMFs used for schedule evaluation in aviation predict fatigue as a function of the three-process model (TPM), with the three processes being sleep duration, time of day, and sleep inertia [

13,

14]. Some BMMF software allow users to model operational workload [

15], but currently, there is no standardized method for modeling fatigue risk in the environmental or psychosocial domains, or to account for the possibility of compound fatigue. The current project describes the first steps taken to identify which factors M-H pilots found most fatiguing from across four discrete domains: 1) circadian factors; 2) operational or scheduling factors; 3) environmental factors and; 4) psychosocial, COVID mandate-related, or interpersonal factors. To our knowledge, this is the first survey asking pilots to report sources of fatigue associated specifically with M-H operations across multiple domains.

2. Materials and Methods

Subjects provided written informed consent for their participation. All mission crew were considered eligible for inclusion regardless of gender, ethnicity, age (over 18), sleep habits, or health status. Secondary use of de-identified data for research purposes was deemed non-human subjects research by Salus IRB on October 11, 2024 (Study ID: 23446) and these analyses were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

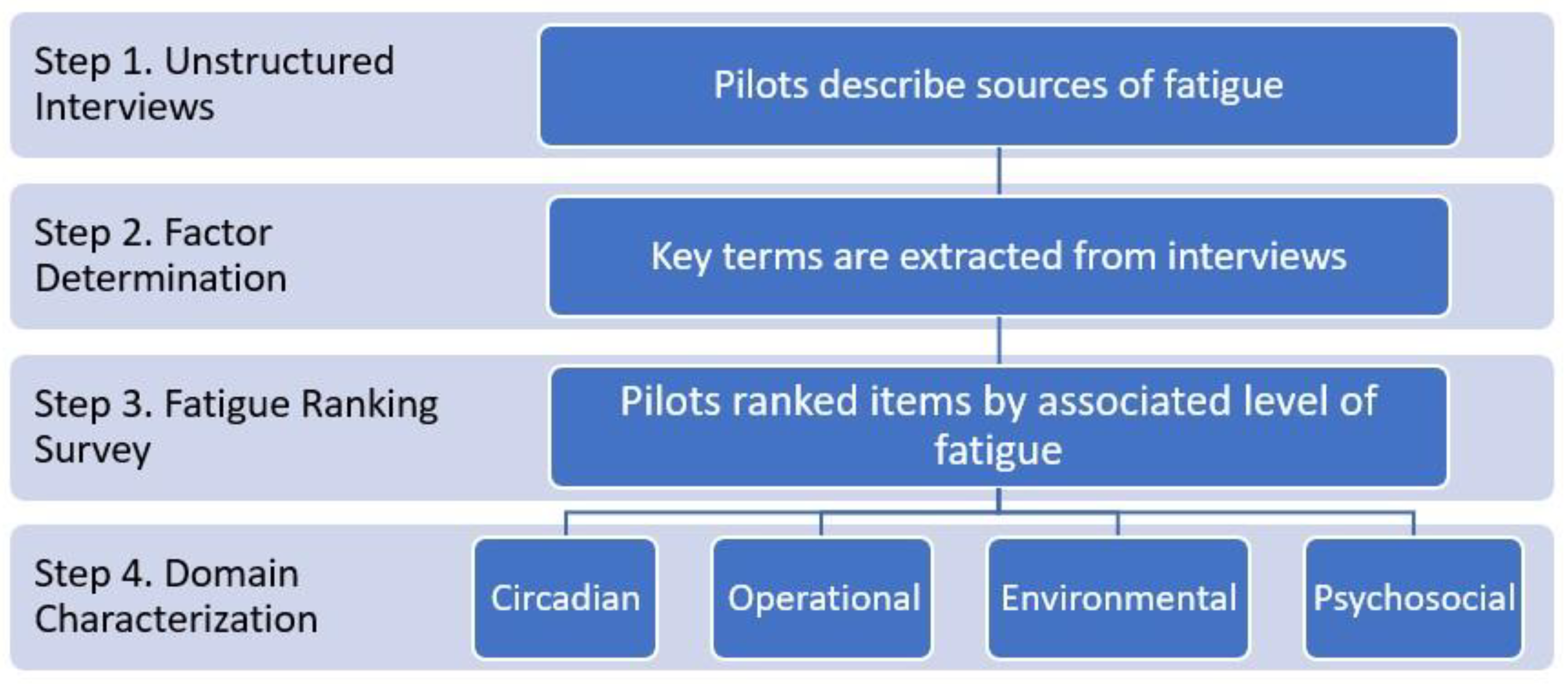

Study procedures took place in four parts as demonstrated in

Figure 1. As a first step, a preliminary sample of 8 pilots (7 men, mean age = 41) were recruited offline for unstructured interviews using convenience sampling. Pilots were asked to describe fatigue during M-H operations in their own words. The aim of the interviews was to identify common sources of fatigue within the MH fleet to ensure that the content of the final fatigue survey would be relevant to the target population. Each interview transcript was analyzed independently by the research team. Key terms that summarized a fatigue factor were extracted from the interview transcripts. Duplicate, idiosyncratic, or poorly worded items were removed.

In total, 40 items were identified as common fatigue factors as identified by the interview process. The 40 items were compiled into an anonymous online survey which asked pilots to rate each factor on a scale of Not at All Fatiguing (0) to Extremely Fatiguing (10). Survey items were categorized based on fatigue domain (Circadian, Operational, Environmental, Psychosocial). Survey items are listed by domain in

Table 1 below. Pilots were also asked to provide demographic information about their age, years of experience and rank, and sleep behavior. Survey items were displayed randomly to pilots rather than by domain to avoid order effects.

All analyses were done in Excel 2013 and STATA MP 15. The Excel 13 Rank function was used to calculate weighted mean rank order for all 40 fatigue factors independently from domain. Fatigue rank was furthermore investigated within domains: 1) Circadian; 2) Environmental; 3) Operational; and 4) Psychosocial. Linear regression was used to examine the influence of habitual sleep duration on pilots’ overall rating fatigue, as well as average fatigue ratings within each domain.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Pilot demographics are summarized in

Table 2. N=223 medium-haul pilots (90 Captains; 133 First Officers) completed the online survey. Pilots were 43 years old on average, with over 8000 hours of flight time. For reference, the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) limits commercial pilots’ total flight time to 1000 hours/year 7, suggesting that survey participants had approximately 8 or more years’ commercial pilot experience. Pilots indicated that they normally slept 7 hours on average, which is in line with the National Sleep Foundation’s recommendations that adults receive 7-9 hours of sleep per night8. Habitual sleep duration did not predict higher fatigue ratings overall or fatigue within domains (all p>0.05).

3.2. Fatigue Rank Order

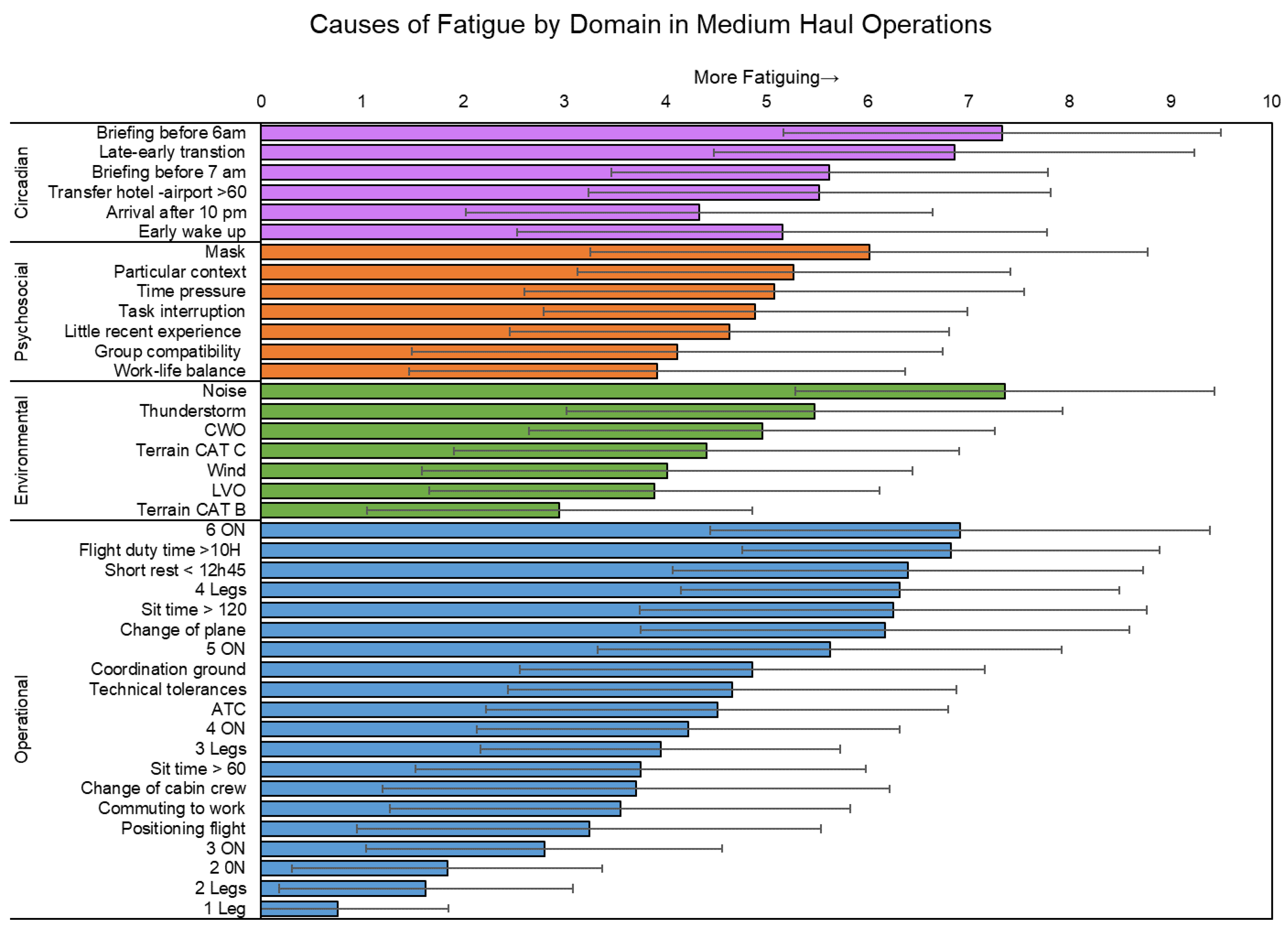

Fatigue rating for each item by domain are depicted in

Figure 2. Items are ranked top to bottom from most fatiguing to least fatiguing within domains. Domains are organized from most fatiguing (top) to least fatiguing (bottom). The average fatigue rating across all 5 items in the Circadian domain was 5.7±1.7 out of a maximum rating of 10. The average fatigue rating across all 7 items in the Psychosocial domain was 4.8±1.5 while the average rating across all 7 items in Environmental domain was 4.7±1.7 and the average rating across all 21 items in the Operational domain was 4.4±1.2. Pilots rated “Noise” from the Environmental domain as more fatiguing than any other item, with an average rating of 7.4±2.1 followed by: “Briefing before 6AM” (7.3±2.2) and “Late-early transition” (6.9±24) in the Circadian domain; working 6 consecutive days, or “6 ON” (6.9±2.5); and “Flight duty time >10 H” (6.8±2.1) in the Operational domain. The most fatiguing item in the Psychosocial domain was wearing a mask to prevent the spread of COVID-19, or “Mask” (6.0±2.8).

4. Discussion

Commercial airline pilots M-H pilots (N=223) completed an anonymous online survey reporting their subjective level of fatigue associated with 40 separate items across four domains. To our knowledge, this is the first study to focus specifically on sources of fatigue in M-H operations (flight segments between 3- 8 hour each, crossing less than 3 times zones). The target population conducted north-south operations predominantly in Europe, and thus, did not regularly cross time zones as part of the duty day. M-H pilots in this study returned to their base airport by the end of the duty day and slept in their home environment. Perhaps because of this, pilots reported regularly receiving an average amount of sleep for healthy adults (~7 hours/night). Habitual sleep duration did not predict higher subjective report of fatigue. This finding is in line with the expectation that M-H pilots do not experience circadian misalignment or sleep deprivation related to travel across time zones or sleeping in hotel environments.

Pilots reported receiving sufficient sleep but found circadian-related survey items (i.e., early start times, late finishes, and transitioning between a late finish to an early start) as more fatiguing overall compared to items in other domains. This finding supports what is known about the biological circadian rhythm—namely that humans are less alert in the early morning or late at night [

16,

17,

18]. These schedule features may also limit opportunities for sleep, which would additionally result in fatigue due to sleep restriction [

5]. Importantly, sleep and circadian factors cannot be ignored when investigating M-H or short-haul operations even though pilots may regularly sleep a healthy duration in the home environment. Sleep deprivation and circadian misalignment can occur in the absence of multi-day travel across time zones, as is the case with social jet lag [

19,

20].

The average fatigue rating for items in the Psychosocial and Environmental domains was higher than the average fatigue rating for items in the Operational domain. However, it should be noted that the Operational domain contained three times as many items (21 versus 7 items) as either the Psychosocial and Environmental domains, including items that would reasonably be expected to be less fatiguing, such as operating only 1 flight leg per duty day or working 2 days consecutively as opposed to 3 or more days in a row. Operational factors comprise a wide range of scheduling activities and thus, are related to a wide range of subjective report of fatigue. Generally, ratings from the Operational items suggest that longer working hours with fewer breaks was related with higher fatigue. This commonsensical finding provides an ideal target with regards to predicting area of compound fatigue risk using a BMMF. BMMFs traditionally predict fatigue as a function of time of day and prior sleep history in relation to the work schedule. Workload triggers can be set within the BMMF software SAFTE-FAST to indicate that fatigue will increase with longer time on task independently of time of day or opportunities for sleep [

15]. Future applications for the findings reported here include adapting SAFTE-FAST predictions of fatigue risk to account for known workload factors in addition to sleep history and circadian rhythmicity in order to identify areas of high compound fatigue risk.

The workload triggers in SAFTE-FAST could be applied to some of the Environmental fatigue factors as well. Cockpit noise, landing terrain at the destination airport, cold weather conditions, and some types of low visibility (e.g., landing after nightfall) may be predicted by information about the aircraft type, time of year, time of day, and geographical locations of the airports within a given roster. However, modelers should be cautious when factoring in environmental fatigue since weather is generally unpredictable. It should also be noted that extreme weather patterns related to climate change could increase pilot fatigue or independently create a safety risk in aviation [

21].

Importantly, pilots reported moderate levels of fatigue (4-6 out of a maximum 10) associated with psychosocial factors. Psychosocial fatigue cannot currently be accounted for by BMMFs but can contribute to performance deficits [

22,

23]. Aviation can be a stressful work environment, particularly in the midst of global changes to daily operations and travel [

24]. A successful fatigue risk management system (FRMS) should therefore consider ways to support aviation worker wellbeing at the organizational level [

25]. Wearing a mask to prevent the spread of COVID-19 was listed as the most fatiguing psychosocial factor during this survey. A 2022 survey conducted by Çarikci et al. also found that prolonged mask-wearing is related with temporomandibular dysfunction and physical fatigue [

26]. Taken together, these findings suggest that fatigue related to wearing a mask can be substantial. As the writing of this report, mask mandates are in decline. However, it is possible that mask wearing may be required again during future waves of COVID-19 or other pandemics. Mask-wearing could be incorporated as a predictable workload factor in SAFTE-FAST under mandated circumstances. However, an individual’s choice to wear a mask on any given workday cannot currently be anticipated.

Pilots in this survey worked M-H operations for a European carrier and were recruited through the company. This constitutes a limitation to generalizability as well as a potential for participation bias when interpreting the survey’s results. The survey was administered in one language, which may constitute a participation bias as well. Pilots were allowed to complete the survey at their convenience and this study did not collect objective sleep or fatigue data. It is therefore possible that fatigue ratings may have been influenced by a pilots’ recent experience or level of sleep deprivation in a manner that cannot be accounted for within the context of this analysis. Despite these limitations, the results of this survey can help inform not only future directions for understanding the impact of compound fatigue risk on aviator performance, but also highlight areas for improvement in biomathematical modeling of fatigue and fatigue risk management initiatives beyond the use of BMMFs.

5. Conclusions

Fatigue in M-H operations arises from multiple domains. Sleep deprivation may not be a driving factor for fatigue accumulation in M-H but should not be ignored whenever the goal is to understand fatigue. Circadian factors such as waking early or working late may interact with environmental, operational, or psychosocial factors to result in compound fatigue risk. Fatigue risk management systems may benefit by accounting for compound fatigue risk through modeling initiatives. Unpredictable fatigue factors, particularly in the Psychosocial and Environmental domains, may be mitigated by providing support beyond scheduling or biomathematical modeling.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, J.B.; methodology, J.K.D., S.R.H., and J.B.; software, J.K.D., and S.R.H.; formal analysis, J.K.D., S.R.H., and J.B.; investigation, J.B.; data curation, J.K.D., and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K.D.; writing—review and editing, J.K.D., S.R.H., and J.B.; visualization, J.K.D.; supervision, S.R.H., and J.B.; project administration, J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved for secondary use by Salus IRB on October 11, 2024 (Study ID: 23446).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the pilot participants for dedicating their time to provide meaningful feedback about fatigue in medium-haul aviation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no direct conflicts of interest. The Institutes for Behavior Resources provides sales of SAFTE-FAST, software that uses a biomathematical model of fatigue. Authors J.K.D., and S.R.H. are affiliated with the Institutes for Behavior Resources. Author S.R.H. is the inventor of the SAFTE-FAST biomathematical model and a fraction of his compensation is based on sales of the software.

References

- FAA, Flightcrew member duty and rest requirements.. In Federal Aviation Administration. US Department of Transportation: Washington DC, 2012; Vol. FAA-2009-1093.https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/rulemaking/recently_published/media/2120-aj58-finalrule.

- EASA welcomes new flight time limitations rules. In European Union Aviation Safety Agency, 2013.https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/newsroom-and-events/press-releases/easa-welcomes-new-flight-time-limitations-rules.

- Cosgrave, J.; Wu, L.J.; van den Berg, M.; Signal, T.L.; Gander, P.H., Sleep on long haul layovers and pilot fatigue at the start of the next duty period. Aerosp. Med. Hum. Perform. 2018, 89, 19–25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, G.D.; Petrilli, R.M.; Dawson, D.; Lamond, N. Impact of layover length on sleep, subjective fatigue levels, and sustained attention of long-haul airline pilots. Chronobiol. Int. 2012, 29, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gander, P.H.; Mulrine, H.M.; van den Berg, M.J.; Smith, A.A.T.; Signal, T.L.; Wu, L.J.; Belenky, G., Pilot fatigue: relationships with departure and arrival times, flight duration, and direction. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2014, 85, 833–840. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, D.; Spencer, M.B.; Holland, D.; Broadbent, E.; Petrie, K.J., Pilot fatigue in short-haul operations: Effects of number of sectors, duty length, and time of day. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2007, 78, 698–701.

- Hilditch, C.J.; Gregory, K.B.; Arsintescu, L.; Bathurst, N.G.; Nesthus, T.E.; Baumgartner, H.M.; Lamp, A.C.; Barger, L.K.; Flynn-Evans, E.E., Perspectives on fatigue in short-haul flight operations from US pilots: A focus group study. Transp. Policy 2023, 136, 11–20. [CrossRef]

- Arsintescu, L.; Chachad, R.; Gregory, K.B.; Mulligan, J.B.; Flynn-Evans, E.E., The relationship between workload, performance and fatigue in a short-haul airline. Chronobiol. Int. 2020, 37, 1492–1494. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, C.; Mestre, C.; Canhão, H.; Gradwell, D.; Paiva, T., Sleep complaints and fatigue of airline pilots. Sleep Sci. 2016, 9, 73–77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, G.D.; Sargent, C.; Darwent, D.; Dawson, D. Duty periods with early start times restrict the amount of sleep obtained by short-haul airline pilots. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 45, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gander, P.H.; Gregory, K.B.; Graeber, R.C.; Connell, L.J.; Miller, D.L.; Rosekind, M.R., Flight crew fatigue II: short-haul fixed-wing air transport operations. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 1998.

- Alcéu, P.M. d. M. Managing fatigue in a regional aircraft operator: fatigue and workload on multi-segment operations. 2015.

- Mallis, M.M.; Mejdal, S.; Nguyen, T.T.; Dinges, D.F., Summary of the key features of seven biomathematical models of human fatigue and performance. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2004, 75, A4–A14.

- Akerstedt, T.; Folkard, S., Predicting duration of sleep from the three process model of regulation of alertness. Occup. Environ. Med. 1996, 53, 136–141. [CrossRef]

- Workload Calculator. In SAFTE-FAST, 2020.https://www.saftefast.

- Folkard, S.; Hume, K.I.; Minors, D.S.; Waterhouse, J.M.; Watson, F.L., Independence of the circadian rhythm in alertness from the sleep/wake cycle. Nature 1985, 313, 678–679. [CrossRef]

- Monk, T.H.; Moline, M.L.; Fookson, J.E.; Peetz, S.M., Circadian determinants of subjective alertness. J. Biol. Rhythm. 1989, 4, 393–404. [CrossRef]

- Van Dongen, H.P.; Dinges, D.F., Circadian rhythms in fatigue, alertness, and performance. Princ. Pract. Sleep Med. 2000, 20, 391–399.

- Wittmann, M.; Dinich, J.; Merrow, M.; Roenneberg, T., Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol. Int. 2006, 23, 497–509. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebl, J.T.; Velasco, J.; McHill, A.W., Work Around the Clock: How work hours induce social jetlag and sleep deficiency. Clin. Chest Med. 2022, 43, 249–259.

- Ryley, T.; Baumeister, S.; Coulter, L., Climate change influences on aviation: A literature review. Transp. Policy 2020, 92, 55–64. [CrossRef]

- Starcke, K.; Brand, M., Decision making under stress: a selective review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012, 36, 1228–1248. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vine, S.J.; Uiga, L.; Lavric, A.; Moore, L.J.; Tsaneva-Atanasova, K.; Wilson, M.R., Individual reactions to stress predict performance during a critical aviation incident. Anxiety Stress Coping 2015, 28, 467–477. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, B.-L.; Al-Ansi, A.; Kim, S.; Wong, A.K.F.; Han, H., Examining airline employees’ work-related stress and coping strategies during the global tourism crisis. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 3715–3742. [CrossRef]

- Cahill, J.; Cullen, P.; Gaynor, K., The case for change: aviation worker wellbeing during the COVID 19 pandemic, and the need for an integrated health and safety culture. Cogn. Technol. Work 2022, 1–43.

- Çarikci, S.; Ateş Sari, Y.; Özcan, E.N.; Baş, S.S.; Tuz, K.; Ünlüer, N.Ö. An Investigation of temporomandibular pain, headache, and fatigue in relation with long-term mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic period. CRANIO® 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).