1. Introduction

Today, defining food as a cultural object may seem almost self-evident, akin to the possibility of developing research related to the socio-cultural aspects of food production and consumption. Over the past two decades, a new way of perceiving and understanding food has solidified worldwide [

1]. However, a purely functionalist approach, which views food merely as "material consisting essentially of protein, carbohydrate, and fat used in the body of an organism to sustain growth, repair, and vital processes and to furnish energy"—as one of the leading English-language dictionaries defines it [

2]—has yet to fade entirely. Cultural anthropology, particularly the branch called the “anthropology of food”, has been a pioneering discipline in exploring and conceptualising this new understanding of food as a prism to examine a community’s culture and its socio-cultural transformations [

3]. Cultural anthropology studies human societies, cultures, and their development, with a focus on understanding the customs, beliefs, practices, and social structures that define human groups through a qualitative approach involving long-term fieldwork, participant observation, and interviews to collect detailed, firsthand accounts of people's lives [

4]. It has provided crucial insights into human diversity and how cultural forces shape social behaviour and worldviews. In this effort, food became one of the objects of research used to understand how communities managed their life, interacted with the environment, and shaped interpersonal relationships [

5].

This article, which grew from discussions at the 2024 conference of the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) and a panel on the future of food anthropology, aims to outline how anthropology has explored food, beginning with the early contributions of the early 20th century. It also offers insights into sources that can be used for further study and highlights emerging trajectories in the debate, supported by brief case studies that exemplify ongoing research. Overall, it provides novel insight into this field of research and the state of the art of the research within the EASA Anthropology of Food Network, one of the largest professional networks of specialists in this field.

2. Methodology

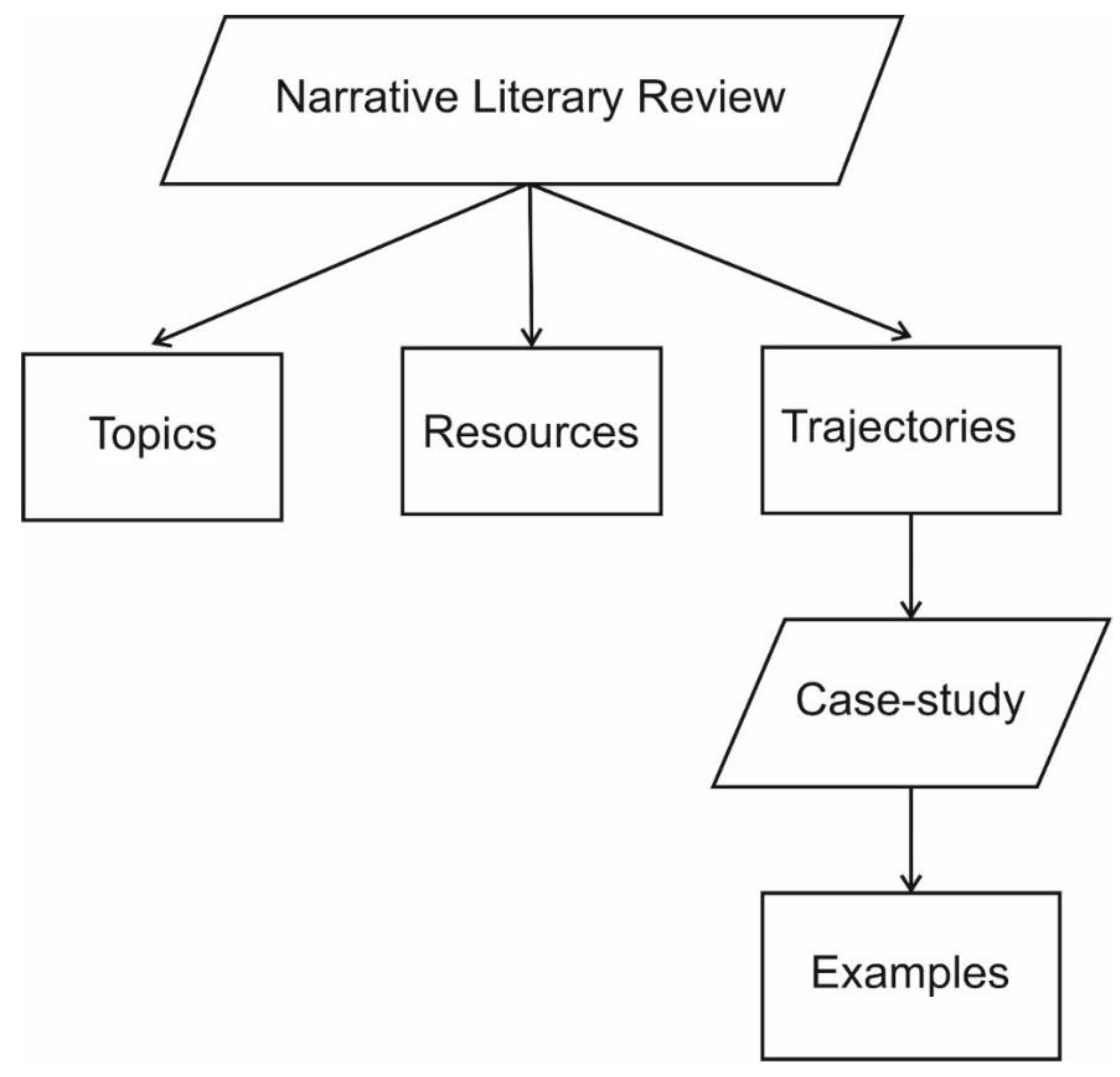

This article is based on multilayered research that combines a narrative review with case-study analysis (

Figure 1). The combination of these two methodologies offers breadth and depth in the exposition: the narrative review offers a broad understanding of the literature. At the same time, the case studies provide detailed, context-specific insights that can inform and enrich broader theoretical discussions.

A narrative review is a qualitative synthesis of existing research and literature to comprehensively overview a specific topic following an interpretive analysis without the rigid schematism of a systematic review [

6]. For this article, the narrative review was used for developing an outline of this cultural anthropology sector's development as well as its key topics, resources and trajectories. This work builds on the seminal contribution of Mintz and Du Bois [

3], who produced a first historical account of the origins and trajectories of food anthropology. In so doing, the article extended the range of bibliographic sources to consider the more recent decades and contemporary and emerging global challenges of relevance to anthropology. Relevant sources have been identified using citation databases, such as Scopus, Google Scholar, and the Anthropological Index Online.

By trajectory, we mean a consistent focus on specific topics that recur in the literature and are subjects of current research. Specifically, the article focuses on the following: post-colonialism and indigenous rights; heritage transformation and its socio-economic use; food security and social marginalisation/inclusion; diet signification and change; sensorial understanding and its use; food and post-humanism. For each of the trajectories, we identify specific case studies of current, ongoing research to shed light on the recent developments in the field. These researches are presented to provide a concrete example of the ethnographic strategies and results emerging from the field and the new theoretical challenges the anthropological community is tackling.

We note that this piece is not a complete catalogue of all the work in the anthropology of food—fortunately, it is now far too broad and lively a field to be contained in a single article—but, rather, is a tool for understanding the broad-scale intellectual history and development of an important anthropological sub-discipline. Moreover, our emphasis is on the social anthropology of food and not the biosocially-grounded approach of the closely intertwined discipline of nutritional anthropology; readers wishing for an overview of nutritional anthropology may find Ulijaszek [

7] a useful starting point.

Proofreading was completed with Grammarly and ChatGPT softwares, which assisted the authors in polishing and steamlining the text.

3. Untangle the Trajectories

3.1. The Beginning of a Journey

Food is not merely ‘simple matter.’ Using a well-known pair of opposites, nature and culture [

8], food represents a synthesis of these two aspects: on the one hand, the materiality and natural quality of its ingredients; on the other, the intangibility of knowledge tied to methods of sourcing raw materials, techniques of transformation and preparation, and practices associated with consumption. Given this distinctive nature—and the need for all cultures everywhere to eat—, it is no surprise that the anthropological community has repeatedly turned its focus to food and subsistence methods throughout the history of the discipline.

The modern history of cultural anthropology is conventionally marked by the works of Franz Boas and Bronislaw Malinowski, scholars born in the second half of the nineteenth century. Their scientific contributions in the early decades of the twentieth century defined the trajectories of cultural anthropology's theory and methods [

9]. Their works are also relevant to the debate on food and food culture.

In their writings, one finds meticulous descriptions of the food systems within the communities they studied. In particular, Boas [e.g. 10] examined food as part of his broader ethnographic work with indigenous communities, predominantly among Native American groups in the Polar regions and Pacific Northwest. He observed how food practices—such as fishing, foraging, and food preservation—were adapted to their environment and encoded cultural knowledge related to sustainability and social organization. For Boas, these practices were essential to understanding these communities’ cultural systems and social roles. His work emphasized how food practices are intertwined with myths, rituals, and social relations, thereby reflecting broader cultural meanings and values.

Following this example of cultural relativism and holistic analysis, Malinowski [

11,

12] used food, specifically yams, as a lens to explore the systems of material and immaterial exchanges among the communities of the Trobriand Islands. His analysis of the cultivation, distribution, and consumption (or non-consumption) of this vital tuber demonstrated that food is not simply a means of sustenance; it also serves as a medium for building reciprocity, alliances, and social prestige, with each exchange carrying both symbolic and social significance. In this respect, the work of the anthropologist was able to demonstrate the multiplicity of uses and meanings of food, opening the field for anthropology to explore food from different perspectives and angles.

In the years following the publications of Boas and Malinowski, a new generation of scholars continued to point the ethnographic lens on food and alimentation, situating these studies within a broader interest in the structure of local cultural systems and their social frameworks. Among these, Margaret Mead’s work in Papua New Guinea, presented in

Growing Up in New Guinea [

13], provides a notable example. Mead demonstrated how food gathering, preparation, and consumption were intricately linked to gender roles and social organization. Moreover, she showed how material and symbolic access to food played a fundamental role in children’s socialization, shaping their development and social learning.

British-trained anthropologists conducted more in-depth studies on the structure of food systems. One well-known example is Evans-Pritchard’s research with the Nuer in Sudan [

14], where he described how cattle herding was central to Nuer economy, diet, and social organization, underpinning much of their social structure and cultural identity. Specifically, he showed that cattle were not merely economic resources but the fulcrum of social life and cultural practices, including marriage, political alliances, and spiritual beliefs, being a cultural symbol rather than just a source of sustenance. On the other hand, Audrey Richards’ work with the Bemba in Zambia in the 1930s offers another key study. In

Land, Labour and Diet in Northern Rhodesia [

15], Richards takes what today would be considered a holistic food systems approach in analysing the connections between agricultural practices, food scarcity, and nutritional issues and how these were closely tied to the development of Bemba social structures. As a functionalist, Richards primarily saw the practices and ideas surrounding food as satisfying the needs for survival and ensuring individual and social continuity, yet also recognized that food needed to be understood as part of a total social system.

3.2. From Structuralism to Materialism and Beyond

These pioneering studies helped establish food systems and practices as essential for understanding the interplay between food and society. They laid the basis for future research concerning the interplay between food production and environmental adaptation. However, while food entered the anthropological discourse, anthropologists paid limited attention to culinary aspects, such as culinary tradition, meal structure, and ingredient selection.

Between the 1950s and 1970s, a new generation of researchers, following the hermeneutic approach known as structuralist anthropology, significantly shaped the analysis of cuisine and food by highlighting how culinary practices reflect deep cultural structures. Starting from his famous article ‘The Culinary Triangle’ [

16], then in his book

The Raw and the Cooked [

17], Claude Lévi-Strauss, one of the most prominent figures in structuralism, argued that food preparation and culinary practices reveal binary oppositions fundamental to human thought, such as raw versus cooked, nature versus culture, and fresh versus rotten. More broadly, the French anthropologist suggested that food transformations symbolize the broader cultural process of shaping nature into culture. On the same line, Mary Douglas further expanded structuralist perspectives in food studies, particularly in her influential essay ‘Deciphering a Meal’ [

18]. Douglas applied structural analysis to meal patterns, arguing that what societies consider food and how they organize meals reflect their social structures and belief systems. Her work emphasized that meals and food taboos are not casual but structured systems of symbols and codes, helping to order social relations and reinforce boundaries of purity and pollution.

Overall, structural anthropology revealed that food practices are deeply embedded in societies' cultural logic, shaping how people understand their world and social relationships through structured, often unconscious, symbolic systems. This indicated the crucial importance of the symbolic dimension of food, which will be one of the key levels of anthropological analysis in the next decades [

3].

While structural anthropology explored the symbolic value of food, between the 1960s and the 1970s, a new wave of studies was drawing attention to the interconnection between the material characteristics of local food systems and social organizations and practices. Works by Roy Rappaport, Yehudi Cohen, and Marvin Harris exemplified this approach, representing the emerging of so-called materialist anthropology. In effect, Roy Rappaport, in his influential study

Pigs for the Ancestors [

19], examined the ritualistic use of pigs in New Guinea highland societies to demonstrate how food-related rituals regulate population size, manage environmental impact, and stabilize ecological systems. On the other hand, Yehudi Cohen, in his

The Human Adaptation [

20], proposed that food practices and subsistence strategies are adaptive responses to environmental conditions, forming part of the broader system of social organization in order to maximize resource use, ensuring survival and social stability. Finally, Marvin Harris, in his influential work

Good to Eat: Riddles of Food and Culture [

21], argued that dietary practices are often rooted in practical, resource-based decisions so that food preferences and taboos emerge from the need to increase energy efficiency and resource use.

Largely, the materialist approach to the cultural study of food represented a response and an antithesis of the contribution provided by structuralist anthropology. While the latter suggests foodways are shaped based on the community’s or the individual’s beliefs, the former suggests food practices are not only shaped by cultural beliefs but are grounded in adaptive strategies essential for ecological survival and social cohesion, underscoring the role of material conditions in the shaping of human behaviour [

22].

Starting from the late 1970s, while the debate between structuralists and materialists was still raging, the perimeter of food anthropology was further expanded thanks to the contributions from the emerging feminist anthropology. This approach to anthropological analysis stemmed from the broader debate about women’s rights, examining how gender shapes human experiences, social structures, and cultural practices. While feminist anthropologists were studying how gender intersects with power, inequality, identity, and other social factors, their contribution significantly impacted the study of food and food systems by foregrounding the roles, labour, and cultural meanings associated with women’s work in food production and consumption.

Anthropology of Food and Body [

23], a collection of articles published by Carole Counihan in the 1980s and 1990s, shed light on the development of this investigation, focusing on how food operates as a cultural medium through which women express identity, status, and relationships. Similarly, in her ethnography

Food, Gender, and Poverty in the Ecuadorian Andes [

24], Mary Weismantel explores how food preparation, consumption, and sharing practices in Ecuadorian communities reflected and reproduced gender identities and social hierarchies.

Alongside this debate, during the same period, reflections on the socio-cultural reproduction underlying forms of food and gastronomy also intensified. Key contributions in this area are those of Pierre Bourdieu and Jack Goody. In his

Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste [

25], Pierre Bourdieu demonstrated how food choices are deeply entwined with social structures, class distinctions, and cultural capital. Specifically, he argued that tastes in food, as in art, music, and other cultural realms, are not merely individual preferences but are shaped by social positioning and reinforce class boundaries. On a different note, Jack Goody, in his

Cooking, Cuisine, and Class: A Study in Comparative Sociology [

26], examined the role of food preparation and cuisine in reinforcing social hierarchies. While Bourdieu exclusively focused on France, Goody uses a comparative approach to analyse food practices in European and African societies, challenging the assumption that all societies follow the same evolutionary path in their culinary developments. He argued that the emergence of complex cuisines—marked by refined cooking techniques, specialised ingredients, and elaborate dining rituals—were historically tied to social stratification and the availability of surplus resources, making food a symbol of social status and power, with the upper classes adopting sophisticated cuisines that reflect and reinforce their privileged positions.

3.3. New Venues for Debate

The debates that marked the 1970s had placed food at the centre of the anthropological stage, moving from scattered contributions to a more institutional and cohesive form. This process was driven by the organization of associations, events, and specialized journals, designed to foster shared moments and tools for developing the field. The first organization established was the Society for the Anthropology of Food and Nutrition in the United States in 1974. This association is a section of the American Anthropological Association and focuses on research related to food, nutrition, and agriculture from an anthropological perspective. Just a few years later, in 1979, The Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery emerged. This prestigious annual event brings together scholars, chefs, writers, and food enthusiasts to discuss historical, cultural, and scientific aspects of food, creating a transdisciplinary space for debates on topics such as food heritage, culinary traditions, and food as a cultural practice. In 1980, The International Commission on the Anthropology of Food and Nutrition was also established as part of the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences. This organization represents the first attempt of a global organization of anthropologists interested in food and was aimed at promoting cross-cultural and comparative research on food and nutrition, fostering collaboration among food anthropologists worldwide.

These were only the first initiatives, later joined by other notable organizations, such as the Association for the Study of Food and Society (1985), the EASA Anthropology of Food Network (2012), and more recently, the International Society for Gastronomic Sciences and Studies (2020). These organizations periodically organize events and initiatives that mobilize the international anthropological community, fostering the debate and creating the outlet for new research.

Alongside these aggregative entities, specialized journals played a crucial role in defining the contours of the debate. Among the pioneering publications were Digest: A Journal of Food and Culture (launched in 1979), Appetite (1980), and Food and Foodways (1985), the latter being the only journal explicitly dedicated exclusively to anthropological studies of food. From these early publications, the field has expanded to include interdisciplinary journals such as Food, Culture & Society (1996), Journal of the Anthropology of Food (AOF) / Journal de l’Anthropologie des Aliments (1999), Gastronomica: The Journal of Critical Food Studies (2001), and, more recently, Gastronomy (2023).

Taken together, these institutions represent a strengthening scientific infrastructure supporting the expansion of the field of the anthropology of food.

3.4. Food in a Globalized World

As anthropological debate on food continued to gain strength through new platforms for discussion and dissemination, the 1980s marked a growing focus on the transnational dimensions of food. In this context, the voice of food anthropology began integrating into a broader economic anthropology debate that started exploring the socio-cultural and political meanings of international relations.

Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History [

27] by Sidney W. Mintz brought this new sensitivity to food studies, cantering its analysis on one of the most-used food products: sugar. In this volume, Mintz explored the historical trajectory of sugar from a rare luxury to a common commodity, connecting its production and consumption to the broader systems of global capitalism and colonialism. This investigation traced the profound social and economic shifts driven by the sugar trade, particularly its role in slavery and imperialism, delineating the power dynamics between colonizing and colonized nations, showing how a quotidian food can be a prism through which unfold grand histories.

Sweetness and Power opened a critical line of inquiry for subsequent years—namely, the study of the phenomena and impacts of globalization, and continues to serve as a reference text for a methodological approach of tracing a single foodstuff across time and place. Globalization refers to the process by which people, cultures, goods, and ideas increasingly move across borders, creating interconnected systems that influence social, economic, and cultural life globally; specifically, it shapes local identities, transforms social structures, and leads to the blending or clash of cultural practices [

28]. While the globalization debate has seen anthropologists tackle these transformations from diverse perspectives [

29], one facet of this reflection also includes the transformation of food practices. A foundational contribution in this area came from Arjun Appadurai . Although his work—

Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization [

30]—is often cantered on its modelling of global cultural flows and their impact on identity, migration, and media, it also provides analytical insights for viewing globalization as a process that affects local and national food practices. By focusing on the transformation and the diffusion of Indian cuisine, Appadurai provided an analytical framework for examining culinary hybridization, exploring the interpretive processes behind the diffusion of ethnic cuisines and the emergence of new fusion cuisines.

While Appadurai offers a broad view of globalization processes, Richard Wilk examined the phenomenon from a local perspective. His

Home Cooking in the Global Village: Caribbean Food from Buccaneers to Ecotourists [

31] demonstrated how globalization shapes Caribbean foodways, focusing on the dynamic interaction between local food traditions and global forces. The book investigates how food became an instrument through which the cultural identity of a place is constructed, and historical meaning is redefined in a dialogical process between present-day global market demands (such as tourism) and the public use of local history and heritage. This process is expressed in new culinary forms that blend the local and the global, creating new forms of perceived authenticity.

Further exploring the emic perspective on globalization, James L. Watson explored the process of appropriation and transformation of a global gastronomic model into the specificities of the local society. His

Golden Arches East: McDonald's in East Asia [

32] studied how McDonald’s has been adapted in East Asia and, tackling issues such as cultural adaptation, and resistance, this book illuminates broader questions about how global food corporations impact local food cultures and how communities push back to maintain cultural values, indicating the dynamic and unpredictable dimension of the relationship between the local and the global.

3.5. Activism, Heritage and Sustainability at Large

This interest in globalization one among many topics that anthropologists were exploring through the lens of food. Throughout its history, the anthropology of food has developed by expanding its horizons and adding dimensions to the debate in response to emerging sensitivities of the time, increasingly integrating its voice with those of other disciplines interested in the social and cultural study of food. In the 2000s, this process continued, responding to a new sensitivity toward food aimed at appreciating and valuing the specificities of local food heritage and increasingly viewing food as a platform for political struggle. This new era was initiated at the international level by the success of political and cultural movements such as Slow Food, which aims to support, defend, and promote small local productions and raise awareness about food's economic, aesthetic, and cultural value [

33].

Interpreting this period, the anthropological debate began to investigate food's ethical and political dimensions. In this journey, the research of Donna R. Gabaccia began to define an initial agenda for the debate. For example, her work

We Are What We Eat: Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans [

34]explores how immigration and ethnic cuisines have shaped American foodways, emphasizing the importance of cultural diversity in the U.S. food landscape. In particular, she discusses food as a site of cultural expression and activism, where communities can assert their identities and resist assimilation pressures. From this early contribution, new works have explored various forms of activism. This includes, for example, Margaret Gray's

Labor and the Locavore: The Making of a Comprehensive Food Ethic [

35], which examines the locavore movement’s impact on agricultural labour in New York, and Cristina Grasseni's

Beyond alternative food networks : Italy's solidarity purchase groups [

36] that explores the reality of alternative food networks in Italy.

Alongside these experiences, and in response to the broader debate revitalized by the establishment of the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage and the inclusion of food and cuisines among potential heritage of interest, anthropology has begun to investigate the heritage dimension of food more closely, exploring the specificities of individual products and the processes of heritage-making. In this sense, Ulin's work has been pioneering. In his

Vintages and Traditions [

37], he deconstructs the viticultural image of prestigious regions such as Bordeaux and Médoc, challenging the widespread assumption that the area's elite wines enjoy especially favourable conditions of climate and soil by indicating the crucial historical and social factors that created this imaginary. On a different note, Amy Trubek problematized the concept of terroir, which is often used to define and explain the interlink between food products, communities, and places. In her

The Taste of Place: A Cultural Journey into Terroir [

38], she articulated how terroir can be considered an ethnographic category to express the embodiment of the cultural, environmental, and historical factors that influence food production by the local communities and the sensory experiences of finished food products. In this respect, it describes the role of food in expressing local identity, a local identity that appears threatened by the processes of standardization brought along by globalization.

Like Trubek, other researchers have emphasized the risk of losing local specificities and the biocultural diversity tied to food due to the globalization and modernization of the global food system. At the same time, as local dynamics aimed at protecting and enhancing local gastronomic heritage have developed in response to the disappearance of these specificities, anthropologists have sought to deconstruct the often overly rosy view of these processes. They highlight the implicit exclusion and marginalization that promotion can entail, and the macro- and micro-political dynamics tied to them. A particularly significant contribution in this regard comes from Cristina Grasseni [

39], who has explored the complexities surrounding authenticity certification for dairy production in Northern Italy. Grasseni’s work underscores how efforts to protect traditional products through certification often involve preserving cultural heritage and navigating power dynamics, social tensions, and debates over the true meaning of ‘authentic’ food. This perspective brings attention to the stakes of heritage preservation, showing that while it can protect cultural identity, it also introduces questions of access, representation, and control over these prized food traditions.

While anthropology of food has mainly investigated the aspects of cultural and socio-economic sustainability, in the past decades, the discipline has provided significant contributions to the broader debate on sustainability by exploring how food practices, production systems, and consumption patterns intersect with ecological and social resilience [

40]. Anthropologists have investigated traditional and indigenous food systems, highlighting their sustainable practices and their potential lessons for contemporary food challenges [

41]. For instance, research on agroecological practices and traditional ecological knowledge demonstrates how localized food systems often embody sustainability principles through biodiversity, resource conservation, and cyclical use of natural inputs [

42]. Additionally, the concept of food sovereignty, as explored by scholars like Annette Desmarais, Nettie Wiebe, and Hannah Wittman [

43], ties sustainability to the rights of communities to control their food systems, resisting industrial agriculture's environmental degradation and fostering social equity . Anthropologists have also critiqued the industrial food system, examining the socio-cultural consequences of industrial food production and its ecological impacts, such as soil depletion, water overuse, and greenhouse gas emissions, while highlighting the need for systemic change [

44]. Through these varied lenses, the anthropology of food delved into the complexity of the present times, providing a holistic interpretation and showing that sustainability and resilience can be crucial keywords for research in the next future.

4. Contemporary Development

From this account, it emerges clearly how the anthropological debate on food has expanded and deepened over the course of a century,, exploring various aspects that encompass not only the products themselves but also the production systems and the consumption practices surrounding them. This exploration consistently prioritizes understanding the emic perspectives—that is, the insider viewpoints—that emerge and evolve through food. When looking at the more recent past, we enter an area that is still evolving, marked by research that is often ongoing. We therefore turn to a focus on these active research efforts and the key terms that define them. In this regard, this paragraph presents a selection of research representative of the ongoing debate at EASA and demonstrates a variety of theories and methods in the current anthropology of food. While each leans heavily on participant observation as a methodological pillar, they each also reveal adaptations to specific contexts, research questions, and diverse theoretical landscapes. The case studies have been selected to illustrate major themes in the contemporary anthropology of food and are drawn from scholars originating from across the globe and who are working in diverse research settings. They develop trajectories that are growing in relevance in the debate; the following case-studies shed light on them.

4.1. Postcolonial Food Heritage in Southern Africa

Understanding and reckoning with colonial legacies and postcolonial realities is a major theme in anthropology today, including within the anthropology of food. A particular concern within the anthropology of food is how communities marginalized through colonial processes and the logics of modernity/coloniality [

45] can reclaim and redefine their cultural narratives through the preservation and transmission of food heritage. The preservation and revitalisation of community foodways represent not merely culinary traditions but a reclamation of cultural identity which has often been threatened, silenced, or sidelined [

46]though colonialism and Apartheid coupled with globalized food practices and often has salient implications for human dietary health [

47].

Research undertaken by Jessica Leigh Thornton [

48] in communities across Namibia and South Africa has focused on the sensory conceptualisations of food heritage and heritage’s role in shaping identity within local food cultures. By investigating how traditional culinary practices, recipes, and food related rituals serve as markers of cultural identity and continuity, this work has sought to understand the way that oral revalorisation of these food traditions has played out, exploring how they are transmitted across generations and the impact of disrupted foodways due to colonisation and social upheaval. South Africa’s colonial legacy has deeply affected the cultures and identities of its First Nations Peoples, who face ongoing socio-economic challenges [

49]. Efforts to revitalise Indigenous knowledge systems and rights are hindered by the homogenisation of cultural identities and limited participation in creating intangible cultural heritage [

50]. Food heritage initiatives have been identified as a productive path to addressing these impacts by preserving and promoting traditional culinary practices, as Intangible Cultural Heritage, thereby countering cultural homogenisation and enhancing participation in heritage creation [

51]. In emphasising food as a cultural practice that links the past to the present, marginalised communities are enabled to reclaim and revitalise their identities amidst historical and contemporary challenges [

52]. Food heritage thus becomes a marker of cultural continuity, illustrating the resilience and pride of First Nation communities impacted by colonisation and apartheid [

53].

Photo 1.

Roots and herbs consumed for medicinal practises amongst First Nations People (Photo by

Francois Du Plessis in Kalk Bay, South Africa, 2023).

Photo 1.

Roots and herbs consumed for medicinal practises amongst First Nations People (Photo by

Francois Du Plessis in Kalk Bay, South Africa, 2023).

Photo 2.

Participant preparing medicinal drink before healing ritual. (Photo by Francois Du Plessis in

Blanco, South Africa, 2023).

Photo 2.

Participant preparing medicinal drink before healing ritual. (Photo by Francois Du Plessis in

Blanco, South Africa, 2023).

Photo 3.

Participant preparing !Nara seeds after the pulp has been rendered. (Photo by: Francois Du

Plessis in Gobabeb, Namibia 2023).

Photo 3.

Participant preparing !Nara seeds after the pulp has been rendered. (Photo by: Francois Du

Plessis in Gobabeb, Namibia 2023).

4.2. Indigenous Being and Eating in Honduras

Moradel, in northern Honduras, is a village of the indigenous Pesh people, situated in a contact zone in which imperial projects, violent dispossession, and indigenous life-worlds meet and mix. Within the cosmos inhabited by the Pesh—as with other indigenous groups, particularly across the Americas—being is not genetically predetermined, but a process of becoming with others through the circulation of substance [

54]. As one of the fundamental ways in which substance circulates between beings, eating becomes a fraught space in which questions of identity, being, ethics, epistemology and ontology are contested [

55,

56].

The work of Juan Mejia Lopez [

57] explores being and personhood through a focus on a Pesh dish called

sasal, a white, sticky and sour dish made of cassava. Its ubiquity in everyday discussions of Pesh identity, as well as on the table, lent it weight as a central object of inquiry through which relations could be traced and the sensorially-mediated more-than-human cosmos explored. Discussions around cassava’s cultivation,

sasal’s preparation, and the act of eating it together appear not only as the synchronization of multiple human and more-than-human actors, but as a process of consubstantiation. In this manner, to eat, is to become.

Mejia attempts to answer this deceptively simple question of ‘how are we to eat?’ through an ethnographic exploration of the ways in which indigenous philosophical approaches to eating are articulated in contact zones historically marked by violent dispossession and forced assimilation. This endeavour involves not only bringing into attention historically marginalized or rendered invisible epistemologies as part of wider calls for the decolonization of anthropology and social thought in general [

58,

59,

60], as well as allowing indigenous modes of thought to the multiply one’s own world [

61]. Pesh modes of knowing appear not as isolated remnants as of the past, or idle rumination, but as voices that might destabilize hegemonic epistemologies regarding nature and food.

Photo 4.

‘Tortilla style’ in a plantain life (Photo by Meija Honduras. 2021).

Photo 4.

‘Tortilla style’ in a plantain life (Photo by Meija Honduras. 2021).

4.3. Hungry Ghosts in Hong Kong

While crises like food insecurity and famine have profound biological, political and geographical consequences, they also leave social and cultural traces related to food practices, which anthropologists are well-poised to study. Coping and survival strategies [

62], changes in food practices and preferences [

63], and relationships with and circulation of power are some strands of research related to acute food shortages, while hunger as both a category itself and metaphor has also been ethnographically elaborated in other contexts [

64,

65,

66].

The work of Tyffany Choi [

67] looks at the afterlives of the Second World War-era famine in Hong Kong by historically examining the thriving local traditions of feeding ghosts through folk-religious rituals. As locally understood, hungry ghosts are the desperate, fearsome dead, who died unjust deaths. Unless regularly placated with offerings, these ghosts relieve their hunger by siphoning the vitality of the living in horrifying manners. Taking a hauntological approach, which, as first suggested by Jacques Derrida [

68] and further developed by others [

69], is the practice of illuminating the spectral pasts and phantom futures that shape the present, Choi explores what the ghosts are, why they are hungry, why and how they are fed, and, ultimately, what is created through the practices of feeding ghosts. By investigating Hungry Ghost Festivals, makeshift shrines during the 2019 anti-Extradition Law Bill Amendment protests, and the narratives and urban legends that circulate within communities, the work maps the tentacular ways that memories of wartime hunger and cannibalism live on in contemporary cultural imagination. Food anthropology is not always just about the presence of food: it can be about the reverberations of its absence as well. Tracing the way that locally- and culturally-specific ideas of hunger have travelled and changed over time through different societal shifts, Choi finds that feeding ghosts is a trans-rational, nonmodern act of care [

70], which offers a path to nurture hauntological ties, heal collective traumas, and build communities across a fractured local population [

71] and the living and the dead [

72].

4.4. Food Security and Sustainability in South Africa

Studies on food can be approached from an applied anthropological perspective, as seen from early in the development of the anthropology of food through Margaret Mead’s work with the US National Research Council’s Committee on Food Habits and the sustained work of anthropologists across nutrition and public health programmes worldwide [

73]. Applied anthropologists working with and through food have an important role today in engaging with questions of sustainability and climate change and responding to instability in the global food system alongside rising rates of food insecurity [

74,

75].

The increasing consolidation of the food value chain—both vertically and horizontally—makes equitable distribution of power and profit within the food system nearly impossible [

76], and government and policy actions to address inequalities within the food system are often high-level, generalized, and not based on the experience of those individuals who encounter these systems on a day-to-day basis [

77]. Applied anthropologists working on questions of reducing food insecurity, such as Memory Reid et al. [

78], often take a sustainability approach, focusing on the intersection of environmental sustainability, social inequality, and cultural practices, and their ethnographic grounding provides space for the essential inclusion of those who have lived experience of food insecurity. Such work contributes to understanding the debates on the complex relationships between food systems, cultural practices, and societal change, focusing on how traditional knowledge and community-based solutions address contemporary food insecurity [

79,

80,

81,

82].

Reid’s work explores sustainable approaches to improving food security by asking ‘in what ways can the reduction of food waste contribute to enhancing food access and security in urban environments?’ Working in Johannesburg, South Africa, the team investigated the potential of natural food preservation techniques such as drying and fermenting to extend the shelf life of food and repurpose food that would otherwise be discased or destined for landfills. A wealth of multi-generational wisdom exists in natural preservation techniques, offering a valuable opportunity for knowledge sharing and transfer. Drying is the most cost-effective method, requiring minimal water, energy, ingredients, and time.

4.5. Social Inclusion During Times of Change in Tunisia

During times of change and instability, food is often a concern. This includes both nutritional aspects and the practical questions of how to address food insecurity occasioned by crises [

83], but also how policy and power are negotiated and how the social and symbolic aspects of diets and the acts of eating and feeding change in uncertain times [

84,

85]. The ways in which food practices are lived every day in contexts of instability such as war [

86], natural disasters [

87], and within unstable political and economic regimes [

88] have been of particular interest to anthropologists.

More than a decade ago, Tunisians came together to reclaim ‘bread and dignity’ in the spark of the Arab Spring. Nowadays, facing uncertain political transition and exploitative trade agreements with the northern shores of the Mediterranean, Tunisia remains one of the most food-insecure countries in the region [

89]. Against this backdrop, the work of Sara Pozzi observes Tunisians’ mundane struggles around producing, processing, trading and consuming food, interrogating how revolutionary claims were differently articulated in her informants’ quests for normal lives

(ḥayāt ʿādīyya). Placing food at the centre of analysis and observing the social relations it intersected with served a lens to illuminate people’s social, moral, and political battles for social inclusion in times of major change, revealing the multiple and unstable meanings underpinning the idea of a good life and their integration with social transformation.

Building on recent scholarship discussing the Tunisian ‘economy of indebtedness’ [

90] and literature investigating how people construct good lives in situations of uncertainty [

91,

92,

93], the account demonstrates how people’s everyday negotiations around their food affairs went beyond matters of material sufficiency or accumulation and were instead objects of ethical reflection and moral scrutiny. Through a flexible methodological approach that followed the social lives of food—specifically cereals—across their everyday relations (within families, neighbourhoods, the market, agriculture, and the state), the way people’s seemingly-mundane choices around food contributed to reconstructing situated social spaces and people’s positions within them were revealed.

Photo 5.

Couscous drying for the annual food stock. (Photo taken by Pozzi,Tunisia 2024).

Photo 5.

Couscous drying for the annual food stock. (Photo taken by Pozzi,Tunisia 2024).

4.6. Health, Kinship, and the State in Scotland

Questions around sweetness and sugar have occupied a central place in the anthropology of food for decades thanks to Sidney Mintz’s seminal work

Sweetness and Power [

27]. Today, sugar is also a potent object of public health scrutiny and action, and researchers have since explored how people navigate their relationships to sugar in the context of societal concerns about links between sugar, obesity and diabetes [

94,

95,

96]. Contemporary approaches are often critical of the ‘cultures of nutrition’ [

97] that depoliticize sugar and render it a seemingly straightforward object to regulate.

Approaching sugar as an ethnographic object in contemporary Edinburgh, Imogen Bevan uses it as a lens onto processes of kinship and relatedness [

54]. She explores relations between individual members within families, and between families and the state. Finding that sugar is used to signal love and intimacy, authority and control, naughtiness and indiscipline, guilt and comfort, closeness and distance, Bevan reveals the complex and often contradictory meanings of a foodstuff and how they vary across contexts. Working across schools and homes in a demographically diverse neighbourhood, Bevan noted the way in which sugar was used as an effective tool for the socialization of children—through the promotion of responsible and conscious consumption--while also a source of anxiety for parents who are responsible for ‘domesticating’ public health messaging from the state.

For example, children received different messages about sugar consumption not only between home and school, or between relationships with parents, grandparents, and teachers, but within these same places and relationships. Within a single primary school, children learnt that sugar could be a public health object and food group to avoid, a special reward or celebration, or a more mundane substance of pastoral care [

95]. Whilst sweets and sodas were often viewed as problematic by school staff, hot chocolate and home-baked cakes were provided in specific contexts. This depended both on the kind of school policy being enacted in that moment (aimed at improving physical health, affective wellbeing, or discipline and behaviour), the school setting (classroom, dining hall, playground), and on the social class background of those involved in children’s feeding. Between the children, meanwhile, sweets could be traded to solidify friendships, to express belonging, or to exclude others. Between kin, sugar sparked and revealed tensions surrounding responsibilities for children’s health and for managing their pleasures, in a context where public health messages have come to permeate people’s homes. Food disputes between mothers and in-laws revealed how grandparents use sugar to forge close, non-authoritative special relationships with grandchildren, and their fears about grandparental ties being more fragile than parental ones. Disagreements between parents revealed deeper discords about what it means to be a caring parent and people’s ongoing navigation of gendered forms of labour.

4.7. Vegan Ethics and Activism in the United Kingdom

One concern within the anthropology of food and ethics are the relations we have with food animals—what creatures are edible under what circumstances and how we treat them [

98,

99]. Such relations may be explored in the context of traditional, small-scale systems of production [

100] or intensive industrial farming [

101]. The practise of veganism is a growing response in the United Kingdom, as elsewhere, to industrial scale production and consumption of meat and dairy [

102]. In recent decades, a visible vegan activist presence has emerged to confront the public about their meat eating, representing a form of activism that differs to the longer standing and more radical animal rights movement. While the radical animal rights activists tend to focus on the social relations of capitalism, the vegan activist project is more focussed on developing the self into a morally consistent vegan.

The research of Therese M. Kelly [

103] concerns how these activists differ among themselves in their approach to the problem of meat and its consumption, and in turn, how they differ in persuading others to turn from meat to a vegan diet. This is done through exploring the ethical work [

104] of vegan and radical animal rights activists in Bristol, UK by following the claim that an anthropology of ethics [

105,

106] can elucidate how subjects ‘make themselves’, through particular technologies of the self, or the strategies through which individuals create and understand their own ethics. Through these explorations, Kelly’s work raises important questions about the role of ethics in everyday life for vegan and radical animal rights activists seeking to tackle and change human relations with the animals we eat.

In their work, the activists reflect how they see meat-eating culture through concepts such as carnism [

107], defined as “the belief system that conditions us to eat certain animals” [

108], and speciesism [

109], where moral worth depends solely on one’s species. Examining these narratives within their activist contexts forms an important part of how anthropologists question the cultural orthodoxy of meat consumption when it is clear that beliefs and habits around eating meat are changing [

110,

111].

4.8. Sensing and Communicating Coffee in Brazil

Sensory anthropology focuses on the sensory dimensions of food, such as taste, smell, and texture, and how these experiences are tied to memory, identity, and cultural meaning [

112,

113,

114]. The visceral, sensory nature of food makes it an ideal subject for study through a sensory anthropology lens, wherein the embodied experience of food and how it is linked to sensory perception and memory is frequently emphasized [

115,

116].

How do we come to have our own internal ‘flavour lexicons’, or reference knowledge of what a specific flavour and taste is or should be? Is what I understand a strawberry to taste like the same as what you understand? And is this standard or variable across cultures? Using the case of the international coffee market, Sabine Parrish is looking at the ways that individual knowledge of flavour varies among coffee professionals of different cultural backgrounds [

117]—yet who are expected to grade and assess coffee in a standardized manner—and what impact this may have on selling coffee to international markets. For instance, most of the sensory reference tools used in professional coffee quality control settings, such as the Coffee Taster’s Flavour Wheel and Sensory Lexicon [

118] are based on taste references common to North America and Western Europe, but which may not reflect flavours commonly found in coffee-producing nations. This research takes forward the research of David Howes [

119] on the work of sensory professionals by asking how they are made and how they learn.

The coffee industry globally is highly inequitable [

120,

121], tied as it is to legacies of colonialism and slavery, and even dominant supply-side actors like Brazil—the world’s largest coffee producer and exporter—must work to communicate what is special and unique about a given coffee and, consequently, worth a higher price from potential buyers [

122]. As a form of applied sensory anthropology carried out in conjunction with a wider project involving sensory scientists, the work reveals how differences in sensory language and flavour references impact the value positioning of a coffee on the market and is developing strategies that might be deployed to better align sensory language between coffee traders to communicate the value and characteristics of a given coffee.

4.9. Fermenting the Posthuman in Barcelona

The Anthropocene, or the current geological period in which humans are the primary force in shaping impacting planetary changes, has become an important ethnographic backdrop and object of anthropological inquiry in its own right [

123,

124]. The setting of the Anthropocene, which calls for understanding human impact on the world, has also occasioned an interest in human impacts on and our relationships and entanglements with non-human entities, or the shape of our multispecies interrelatedness. Interspecies perspectives in anthropology frequently consider elements of the natural world such as plants, animals, and microbes, but those linking with food are still scarce [

125], as contemporary anthropology of food is rather centred on the human subject [

126].

Fermentation practices, wherein microbes play a crucial role in food preservation, are found in cultures across the globe and are a vivid example of the ways in which humans are entwined with other species through food [

127,

128,

129]. Moving from the results of her previous research [

130], Aranza Begueria uses urban food activism centred around fermentation as a political and artistic practice which pushes back on local and global environmental and societal crises in Barcelona, Spain. There, fermentation is not only a healthy consumer trend, but also a tool used by activists and artists to engage multispecies relations to confront the challenges of local and global crises by activating groups and initiatives of community care and urban experimentation, and creating spaces for debates around political and economic issues such as food sovereignty, globalization, feminism, or the uses of urban space, among others. Several artists also use the metaphors of the fermentation process to reflect on broader issues such as death, care and affect, or social normativity. By situating this research within a lens of posthumanism—a philosophical stance which decentres the human being from social analysis to focus on the social relevance of spaces, objects, temporalities, technologies and both organic and inorganic beings [

131]—we can begin to reflect on/situate the anthropology of food in a context of multispecies relationships within the Anthropocene.

Photo 6.

Participants at a fermentation festival (Photograph taken by Begueria, Spain 2024).

Photo 6.

Participants at a fermentation festival (Photograph taken by Begueria, Spain 2024).

5. Conclusions

This article has presented an overview of the development of major theories and trends in the sub-discipline of the anthropology of food, a critical object of inquiry for the anthropological endeavour of understanding the beliefs, actions, and organization of human cultures across the globe. Studies of food played important roles in providing ethnographic support to the development of anthropological theories and approaches within functionalist, structuralist, and materialist schools. The study of food and feeding practices also provided a key throughline for beginning to unpick gender norms and understand the division of labour across cultures. The study of food through approaches grounded in political economy have helped us to understand recent and current processes of globalization and neoliberalism, as well as issues pertaining to sustainability, activism, and cultural heritage.

The case studies presented herein were drawn from anthropological research into food cultures, customs, and practices in Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas, showing not only the global relevance of the anthropology of food, but also the diversity of approach and theory therein. From ethics to the sensory, human to more-than-human, from making to doing, exchanging, relating, and eating, food is everywhere within our daily lives no matter where we are in the world and is a useful mirror through which to understand others—and ourselves.

This contribution did not presume to define the entirety of the field of study, but rather to sketch its contours so that anyone approaching it may begin to navigate and orient themselves. In doing so, the article, thus, outlining the trajectories of past and present research, invite emerging and established researchers in moving forward the enquiry, furthering the understanding of food and its entanglement with human and non-human beings as well as its role in transforming the world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SP and MFF; methodology, MFF; investigation: §3 MFF, §4.1 JLT, §4.2. JM, §4.3 TC, §4.4 MR, §4.5 SP, §4.6 IB, §4.7 TMK, §4.8 SP, §4.9 AB; writing—original draft preparation, SP (§4,5) and MFF (§1, 2, 3).; writing—review and editing, all the authors.; visualization, MFF; supervision, SP and MFF; funding acquisition, MFF All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Gastronomic Sciences (protocol code 5/2020, 4 December 2020). The research was conducted according to the ethical guidelines of the American Anthropological Association (Principles of Professional Responsibility). In this article, the names of the research participants, their sensitive data, as well as the names of places have been anonymized.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Corvo, P. Food Culture, Consumption and Society; Palgrave Mcmillan: London, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster. Food. Merriam-Webster.com, 2024.

- Mintz, S.W.; Du Bois, C.M. The Anthropology of Food and Eating. Annual Review Anthropology 2002, 31, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, T.H. Small Places, Large Issues, Third edition; London - New York: Pluto Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, K.E. Piccola etnologia del mangiare e del bere; Il Mulino: Bologna, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.D.; Adams, A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2006, 5, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulijaszek, S. Nutritional anthropology in the world. Journal of Physiological Anthropology 2024, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorel, F. Nature vs. Culture? ELOHI 2012, 1, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, F.; Parking, R.; Gingrich, A.; Silveramn, S. One discipline, four ways : British, German, French, and American anthropology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, Ill, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boas, F. Contributions to the ethnology of the Kwakiutl; Columbia University Press: New York, 1925; pp. vi, 357. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, B. Argonauts of the western Pacific: an account of native enterprise and adventure in the archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea; Routledge: London, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, B. Coral gardens and their magic : a study of the methods of tilling the soil and of agricultural rites in the Trobriand Islands; Allen & Unwin: [S.l.], 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, M. Growing up in New Guinea; a study of adolescence and sex in primitive societies; Blue Ribbon Books: New York, 1930; pp. vi, 7-215 p. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Pritchard, E.E. The Nuer : a description of the modes of livelihood and political institutions of a Nilotic people; Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1940; p. 271 p. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, A.I. Land, labour and diet in Northern Rhodesia; an economic study of the Bemba tribe; Pub. for the International institute of African languages & cultures by the Oxford university press: London, New York etc, 1939; pp. xiv, 2 , 423, 421 p. [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Strauss, C. Le triangle culinaire. L'Arc 1965, 26, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Strauss, C. Mythologiques. 1. Le Cru et le cuit. 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. Deciphering a Meal. Daedalus 1972, 101, 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, R.A. Pigs for the ancestors: ritual in the ecology of a New Guinea people; Yale University Press: New Haven ; London, 1967.

- Coen, Y.A. , (Ed.) Human Adaptation: The Biosocial Background. Routledge: New York, 2017.

- Harris, M. Good to eat : riddles of food and culture; Allen & Unwin, 1986: London, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Counihan, C.; Van Esterik, P. Food and culture, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Counihan, C. The anthropology of food and body : gender, meaning, and power; Routledge: New York, 1999; pp. viii, 256 p. [Google Scholar]

- Weismantel, M.J. Food, gender, and poverty in the Ecuadorian Andes; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, 1988; pp. xii, 234 p. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction : a social critique of the judgement of taste; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, 1984; pp. xi,613p. [Google Scholar]

- Goody, J. Cooking, cuisine and class : a study in comparative sociology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz, S.W. Sweetness and power : the place of sugar in modern history; Penguin, 1986: New York ; Harmondsworth, 1985.

- Hannerz, U. ; MyiLibrary. Transnational connections culture, people, places. 1996, ix, 201 p.

- Inda, J.X.; Rosaldo, R. The anthropology of globalization : a reader; Blackwell Publishers: Malden, Mass, 2002; pp. xii, 498 p. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, A. Modernity at large: cultural dimensions of globalization; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, Minn, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wilk, R.R. Home cooking in the global village : Caribbean food from buccaneers to ecotourists, English ed.; Berg: Oxford ; New York, 2006; pp. x, 286 p.

- Watson, J.L. , (Ed.) Golden Arches East: McDonald's in East Asia. Stanford University Press: Stanford, 2006.

- Siniscalchi, V. «Food activism» en Europe : changer de pratiques, changer de paradigmes. Anthropology of food 2015, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaccia, D.R. We are what we eat : ethnic food and the making of Americans; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Mass, 1998; 278. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. Labor and the locavore : the making of a comprehensive food ethic; University of California Press: Berkeley, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grasseni, C. Beyond alternative food networks : Italy's solidarity purchase groups; Bloomsbury: London, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ulin, R.C. Vintages and traditions : an ethnohistory of southwest French wine cooperatives; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC ; London, 1996; pp. xi,300p,[308]p of plates. [Google Scholar]

- Trubek, A.B. The taste of place : a cultural journey into terroir; University of California Press: Berkeley, 2008; pp. xx, 296 p. [Google Scholar]

- Grasseni, C. The heritage arena : reinventing cheese in the Italian Alps; Berghahn: New York - Oxford, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Collinson, P. Food and sustainability in the twenty-first century : cross-disciplinary perspectives. The anthropology of food and nutrition volume 9 online resource. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, K.; Ryan, P. Lessons from the past and the future of food. World Archaeology 2019, 51, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, D.; Moussouri, T.; Alexopoulos, G. The Social Ecology of Food: Where Agroecology and Heritage Meet. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, N.; Desmarais, A.A.l.; Wittman, H. Food sovereignty : reconnecting food, nature & community; Fernwood Pub.

- Food First: Halifax.

- Oakland, 2010; pp. xii, 212 p.

- Chiffoleau, Y.; Dourian, T. Sustainable Food Supply Chains: Is Shortening the Answer? A Literature Review for a Research and Innovation Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignolo, W. Epistemic disobedience, independent thought and decolonial freedom. Theory, Culture & Society 2009, 26, 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, T.; Thorell, K. Cultural Heritage Preservation: The Past, the Present and the Future; Halmstad University Press: Halmstad, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kesselman, B. Transforming South Africa’s unjust food system: an argument for decolonization. Food, Culture & Society 2024, 27, 792–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, J.L. The Elemental Feast: A taste of nature: Cameroon; Langaa RPCIG: Bamenda, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mawere, J.; Walter, T. Exploring the impact of colonialism on South Africa with a focus on the Venda community: Examining the role of traditional knowledge systems in achieving restorative justice; IntechOpen: London, 2023; pp. 115–142. [Google Scholar]

- Mthethwa, N. A cultural revival towards celebrating our African unity. Available online: https://www.gov.za/blog/cultural-revival-towards-celebrating-our-african-unity (accessed on.

- Carr, G.; Sorensen, M.L.; Viejo-Rose, D. Food as Heritage; McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research: Cambridge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Becuţ, A.; Lurbe Puerto, K. Food history and identity: Food and eating practices as elements of cultural heritage, identity and social creativity. International Review of Social Research 2017, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapelari, S.; Alexopoulos, G.; Moussouri, T.; Sagmeister, K.; Stampfer, F. Food heritage makes a difference: The importance of cultural knowledge for improving education for sustainable food choices. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsten, J. The Substance of kinship and the heat of the hearth: Feeding, personhood, and relatedness among Malays in Pulau Langkawi. American Ethnologist 1995, 22, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, P. The perverse child: Desire in a native Amazonian subsistence economy. Man 1989, 24, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, C. Making Real People: Gender and Sociality in Amazonia; Berg: Oxford, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mejia Lopez, J. The anthropology of food in more-than-human Pech worlds In Proceedings of the EASA 2024: Undoing to redoing food anthropology [Anthropology of Food Network] Barcelona, 2024.

- Gupta, A.; Stoolman, J. Decolonizing US anthropology. American Anthropologist 2022, 124, 778–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, A. Coloniality of power, eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from the South 2000, 1, 533–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa Santos, B. Una epistemología del sur: La reinvención del conocimiento y la emancipación social; Siglo XXI: México, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros de Castro, E. Who is afraid of the ontological world? Some comments on an ongoing anthropological debate. The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 2015, 33, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal, A. Famine that Kills; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Trapp, M.M. You-will-kill-me-beans: Taste and the politics of necessity in humanitarian aid. Cultural Anthropology 2016, 31, 412–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, S. Hunger as more-than-human communicative modality on the West Papuan oil palm frontier. American Anthropologist 2024, 126, 679–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, T. Antiretroviral therapy and nutrition in Southern Africa: Citizenship and the grammar of hunger. Medical Anthropology 35, 433–446.

- Vogel, E. Hungers that need feeding: On the normativity of mindful nourishment. Anthropology & Medicine 2017, 24, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, T. Feeding hungry ghosts in Hong Kong: Thinking with food and hauntology. In Proceedings of the 5th EASA Award for a Postgraduate Student Paper in the Anthropology of Food, London; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, J. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International; Routledge: New York and London, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Good, B.; Chiovenda, A.; Rahimi, S. The Anthropology of Being Haunted: On the Emergence of an Anthropological Hauntology. Annual Reviews 2022, 51, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. We have never been modern; Harvester Wheatsheaf: New York, 1993; 157p. [Google Scholar]

- Sinn, E.; Wong, W.L. Place, identity and immigrant communities: The organisation of the Yulan Festival in post-war Hong Kong. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 2005, 46, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.L. Feeding hungry ghosts: Grief, gender and protest in Hong Kong. Critical Asian Studies 2022, 54, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Himmelgreen, D.A.; Crooks, D.L. Nutritional Anthropology nd its Appliction to Nutritional Issues and Problems. In Applied Anthropology: Domains of Application, Kedia, S., van Willigen, J., Eds.; Praeger Publishers: Westport, CT, 2005; pp. 149–188. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver-Smith, A. Disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation: The view from applied anthropology. Human Organization 2013, 72, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wutich, A.; Brewis, A. Food, water, and scarcity: Toward a broader anthropology of resource insecurity. Current Anthropology 2014, 55, 444–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, S. Corporate power in the agro-food system and the consumer food environment in South Africa. The Journal of Peasant Studies 2017, 44, 467–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, C.; Gallagher-Squires, C.; Spires, M.; Hawkins, N.; Neve, K.; Brock, J.; Isaacs, A.; Parrish, S.; Coleman, P. The full picture of people’s realities must be considered to deliver better diets for all. Nature Food 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adom, R.K.; Simatele, M.D.; Reid, M. Addressing the challenges of water-energy-food nexus programme in the context of sustainable development and climate change in South Africa. Journal of Water and Climate Change 2022, 13, 2761–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aworh, O.C. African traditional foods and sustainable food security. Food Control 2023, 145, 109393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britwum, K.; Demont, M. Food security and the cultural heritage missing link. Global Food Security 2022, 35, 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, G.; Wang, Z.; Maundu, P.; Hunter, D. The role of traditional knowledge and food biodiversity to transform modern food systems. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 130, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Delormier, T.; Marquis, K. Building healthy community relationships through food security and food sovereignty. Current Developments in Nutrition 2019, 3, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, C. Advancing food is medicine: Lessons from medical anthropology for public health nutrition. Perspectives in Public Health 2024, 144, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonini, D.M. The local-food movement and the anthropology of global systems. American Ethnologist 2013, 40, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taussig, M. Nutrition, development, and foreign aid: A case study of US-directed health care in a Colombian plantation zone. International Journal of Social Determinants of Health and Health Services 1978, 8, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, M.M. ‘Never had the hand’: Distribution and inequality in the diverse economy of a refugee camp. Economic Anthropology 2018, 5, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentworth, C. Unhealthy aid: Food security programming and disaster responses to Cyclone Pam in Vanuatu. Anthropological Forum 2019, 30, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garth, H. Food in Cuba: The Pursuit of a Decent Meal; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ayeb, H.; Bush, R. Food Insecurity and Revolution in the Middle East and North Africa: Agrarian Questions in Egypt and Tunisia; Anthem Press: London, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pontiggia, S. Il Bacino Maledetto: Disuguaglianza, Marginalita e Potere nella Tunisia Postrivoluzionaria. Ombre Corte 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mohammad, H. Towards an ethics of being-with: Intertwinements of life in post-invasion Basra. Ethnos 2010, 75, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de l’Estoile, B. Money is good but a friend is better: Uncertainty, orientation to the future, and the economy. Current Anthropology 2014, 55, S62–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, J. Beyond the suffering subject: Toward an anthropology of the good. JRAI 2013, 19, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglar, R. ‘Oh God, save us from sugar’: An ethnographic exploration of diabetes mellitus in the United Arab Emirates. Medical Anthropology 2013, 32, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, I. Sugar, a morally ambiguous substance: Responsibility, social class and pleasure in Scotland’s state primary schools. Medicine Anthropology Theory 2024, 11, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran-Thomas, A. Travelling with Sugar: Chronicles of a Global Epidemic; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cuj, M.; Grabinsky, L.; Yates-Doerr, E. Cultures of Nutrition: Classification, Food Policy, and Health. Medical Anthropology: Cross Cultural Studies in Health and Illness 2021, 40, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, M. Purity and danger : an analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin, E. Knowing cows: Transformative mobilizations of human and non-human bodies in an emotionography of the slaughterhouse. Gender, Work & Organization 2019, 26, 322–342. [Google Scholar]

- Fausto, C. Feasting on people: Eating animals and humans in Amazonia. Current Anthropology 2007, 48, 487–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, A. Porkopolis: American Animality, Standardized Life, and the Factory Farm; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, A.E.; Garnett, T.; Lorimer, J. Framing the future of food: The contested promises of alternative proteins. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 2019, 2, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, T. Carnism and the anthropology of meat. In . In Proceedings of the EASA 2024: Undoing to redoing food anthropology [Anthropology of Food Network] Barcelona; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, W. Varieties of Ethical Stance; HAO Books: Chicago, 2015; pp. 127–174. [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw, J. The Subject of Virtue: An Anthropology of Ethics and Freedom; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zigon, J. Moral breakdown and the ethical demand: A theoretical framework for an anthropology of moralities. Anthropological Theory 2007, 7, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, M. Why we Love Dogs, Eat Pigs and Wear Cows; Conari Press: San Francisco, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, M. Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows: An Introduction to Carnism; Conari Press: Newburyport, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, P. Animal Liberation; Pimlico: London, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fiddes, N. Meat: A Natural Symbol; Routledge: London, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Staples, J.; Klein, J.A. Consumer and Consumed. Ethnos 2017, 82, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, D.; Classen, C. Ways of Sensing: Understanding the Senses in Society; Routledge: London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pink, S. Doing Sensory Ethnography; Sage Publications: London, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stoller, P. The Taste of Ethnographic Things: The Senses in Anthropology; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, D.E. Food and the senses. Annual Review of Anthropology 2010, 39, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahne, J.; Trubek, A.B. A little information excites us: Consumer sensory experience of Vermont artisan cheese as active practice. Appetite 2014, 78, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, S. Caffeinated aspirations: social mobilities and specialty coffee baristas in Brazil. Food, Culture & Society 1–25. [CrossRef]

- World Coffee, R. Sensory Lexicon (second edition); World Coffee Research: College Station, TX, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Howes, D. The science of sensory evaluation: An ethnographic critique; Bloomsbury: London, 2015; pp. 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- West, P. From Modern Production to Imagined Primitive: The Social World of Coffee from Papua New Guinea; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, E.F. Quality and inequality: Creating value worlds with Third Wave coffee; 2021; Volume 19, pp. 111–131.

- Reichman, D.R. Big coffee in Brazil: Historical origins and implications for anthropological political economy. The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 2018, 23, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de La Bellacasa, M.P. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tsing, A.L.; Bubandt, N.; Gan, E.; Swanson, H.A. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kirksey, E. The Multispecies Salon; Duke University Press: Durham, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, A. Eating in Theory; Duke University Press: Durham, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.; Lorimer, J. Fermentation fetishism and the emergence of a political zymology. SSRN 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, J.; Rest, M.; Aldenderfer, M.; Warinner, C. Cultures of fermentation: Living with microbes: An introduction to supplement 24. Current Anthropology 2021, 62, S197–S206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, M. Attunement and multispecies communication in fermentation. Feminist Philosophy Quarterly 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begueria, A. Un equilibrio imperfecto. Alimentación ecológica, cuerpo y toxicidad.; Barcelona, 2016.

- Braidotti, R. The Posthuman; Polity Press: Cambridge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

|