Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

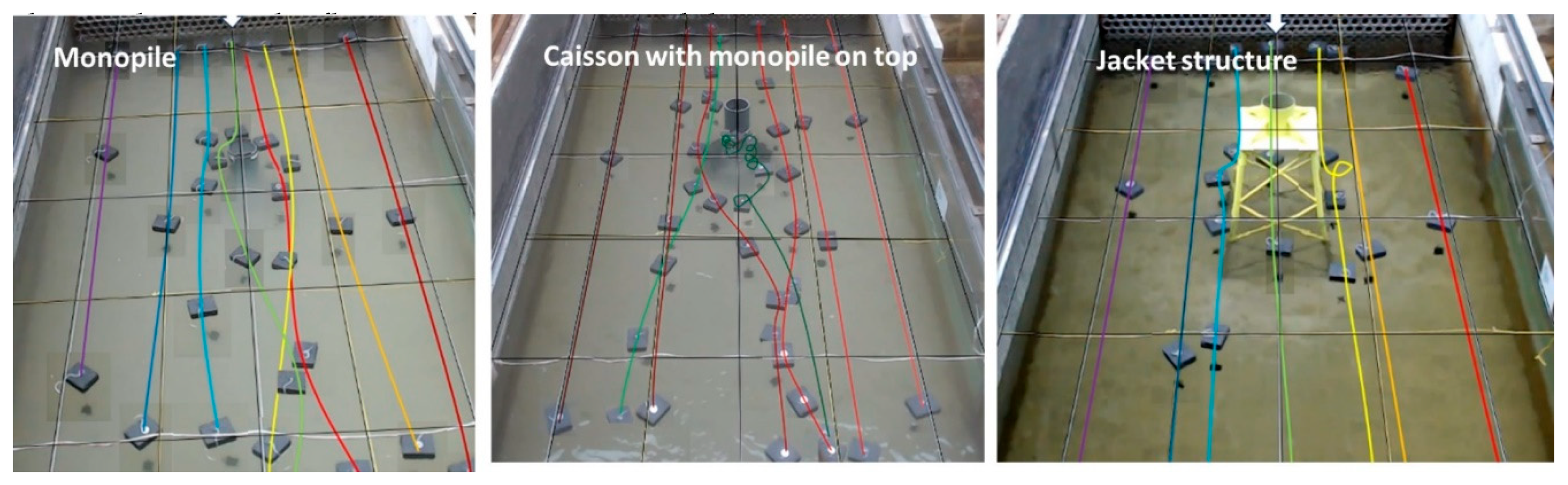

Scour near various offshore structures (monopile, caisson foundation, jacket structure) was studied by performing laboratory flume tests and numerical solutions with a semi-empirical model (SEDSCOUR) and a sophisticated 2DV-model (SUSTIM2DV). The laboratory test results show that the maximum free scour depth around a monopile without bed protection is slightly higher than the pile diameter. The maximum scour consisting of pile scour and global scour around an open jacket structure standing on 4 piles is much lower than the scour near the other structures (monopile and caisson). The maximum scour depth along a circular caisson foundation is found to be related to the base diameter of the structure. The main cause of the scour near these types of structures is the increase of the velocity along the flanks of the structure. Six cases have been used for validation: 2 laboratory cases (A, B) and 4 field cases (C,D,E,F). The measured scour values of the new physical model tests with the monopile and the open jacket structure presented in this paper are in reasonably good agreement with other laboratory and field scour data from the Literature. The semi-empirical SEDSCOUR-model proposed in this paper can be used for the reliable prediction of free scour, edge scour and global scour near monopiles and jacket structures in a sandy bed (even with a small percentage of mud, up to 30%). The maximum scour depth along a large-scale caisson structure is more difficult to predict because the scour depth depends on the precise geometry and dimensions of the structure and the prevailing flow and sediment conditions. A detailed 2DV-model with a fine horizontal grid (2 m) along a stream tube following the contour of the caisson is explored for scour predictions. The 2DV-model simulates the flow and sediment transport in 50 to 100 points over the depth along the stream tube and can be run a time-scale of 1 year.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. General

1.2. Scour Around Monopiles

1.3. Scour Around Gravity-Based Structures

1.4. Scour Around Jacket-Type Structures

2. Experimental and Numerical Methods

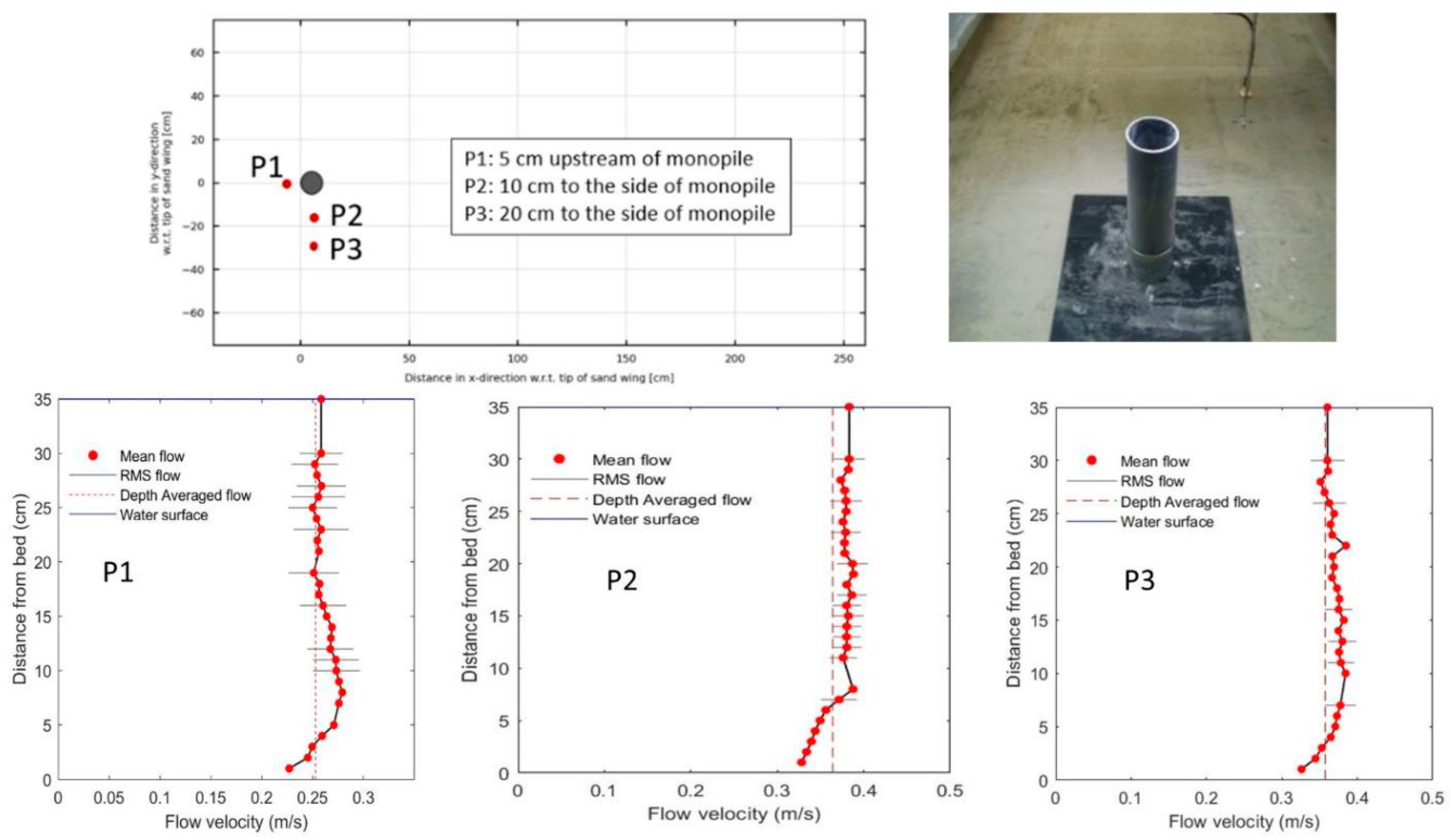

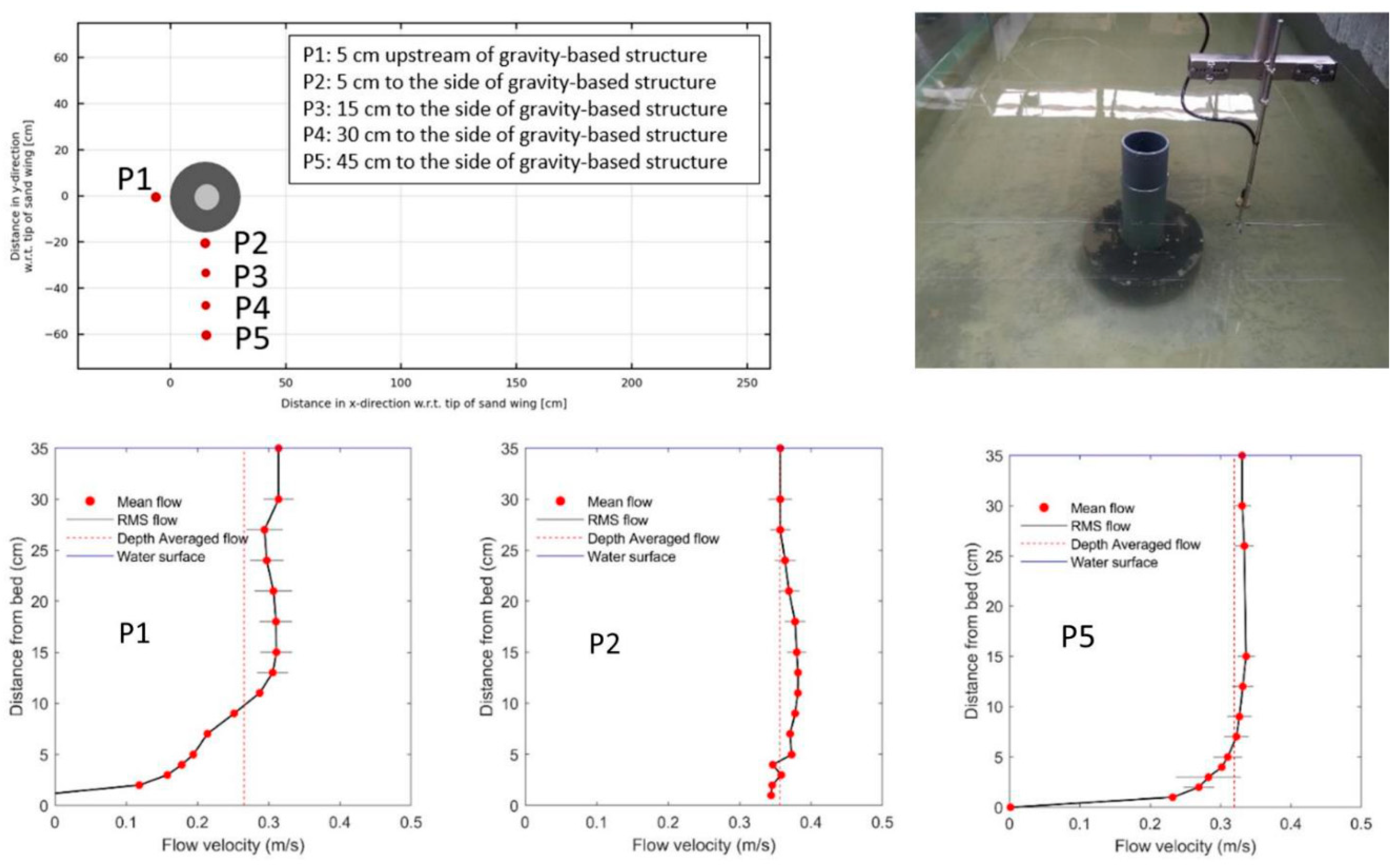

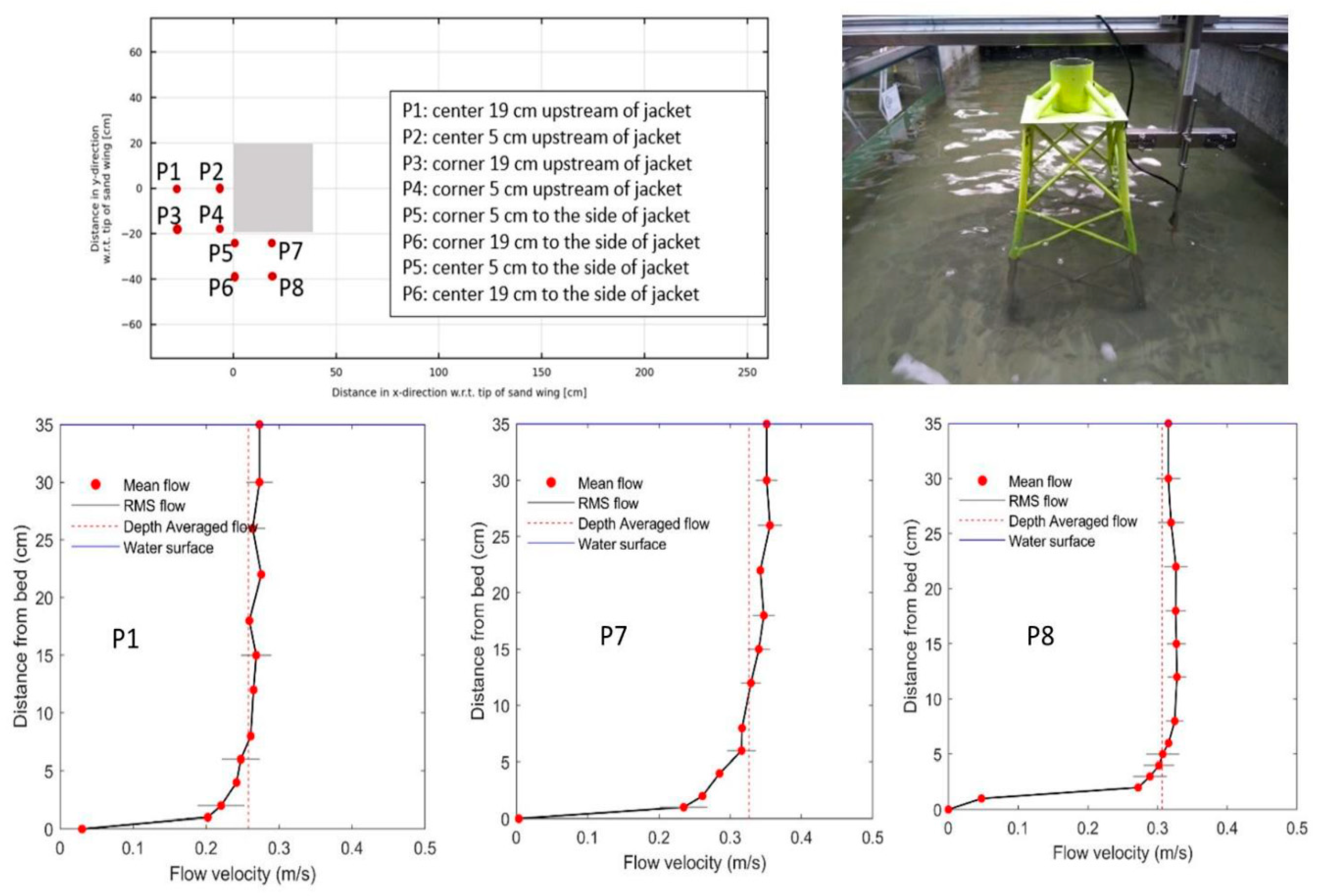

3. Experimental Results of Flow Around Monopile, Jacket Structure and Gravity-Based Structure

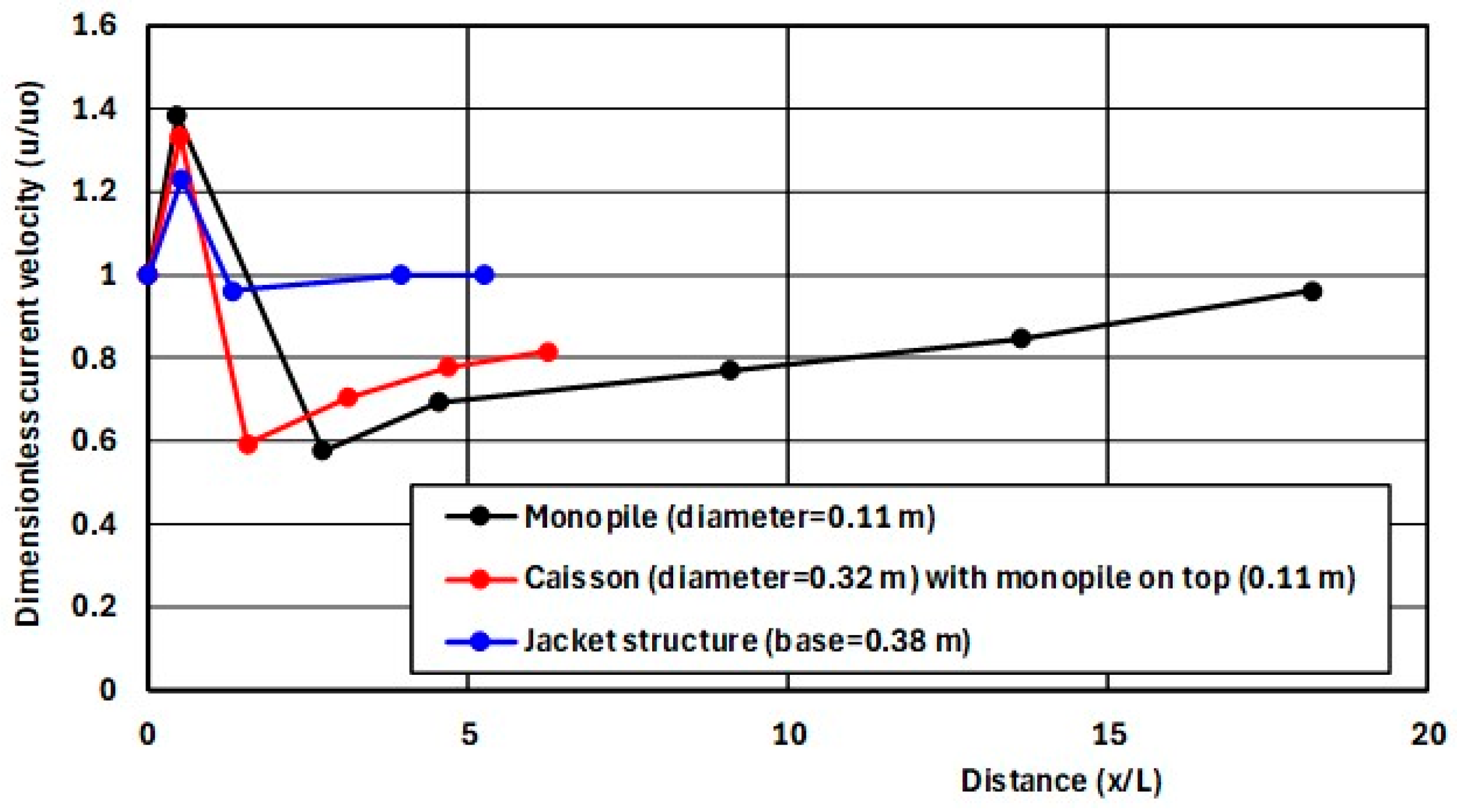

- monopile: significant increase of the approach depth-averaged flow velocity from 0.26 m/s at P1 to about 0.35 m/s at the flanks of the pile at P2 and P3; velocity profile is quite uniform over depth (accelerated flow);

- caisson with monopile on top: significant increase of the approach depth-averaged flow velocity from 0.26 m/s at P1 to about 0.35 m/s on the flank of the caisson at P2; in turn, decreasing for larger lateral distances (0.32 m/s at P5); the velocity profile is rather uniform at P2, the velocity profile at P1 is slightly distorted, most likely due to effect of the downward-directed flow at the base of the structure.

- jacket structure: increase of approach depth-averaged flow velocity from 0.26 m/s at P1 to about 0.30-0.33 m/s at P7 and P8, lateral of the structure; the vertical distribution of the flow velocities is rather similar.

4. Experimental Results of Scour near Monopile, JACKET structure and Gravity-Based Structure

4.1. Experimental Scour Results

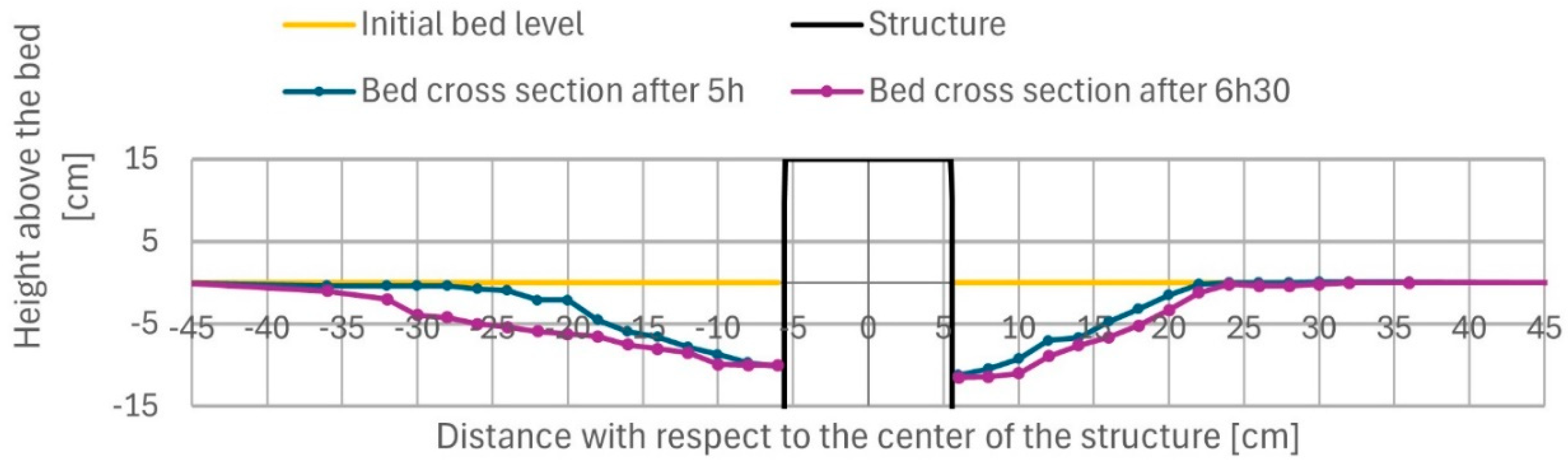

- monopile: maximum scour depth is ds,max≅1.1Dpile after 5 hours with a maximum scour length Ls,max≅3Dpile at both sides;

- caisson with monopile on top: maximum scour depth is ds,max≅1 hcaisson (height of caisson) after 6.5 hours (at which the structure tipped over due to scour undermining, see Figure 6); maximum scour length Ls,max≅1 Dcaisson at both sides;

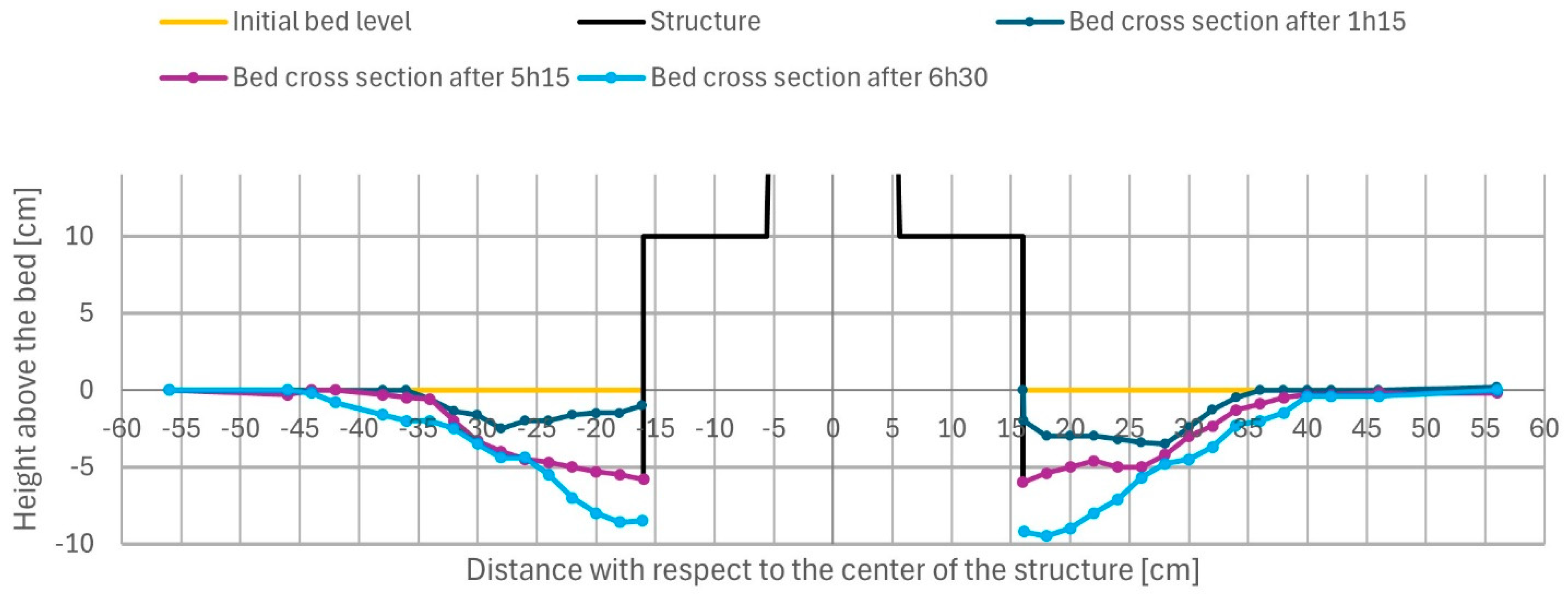

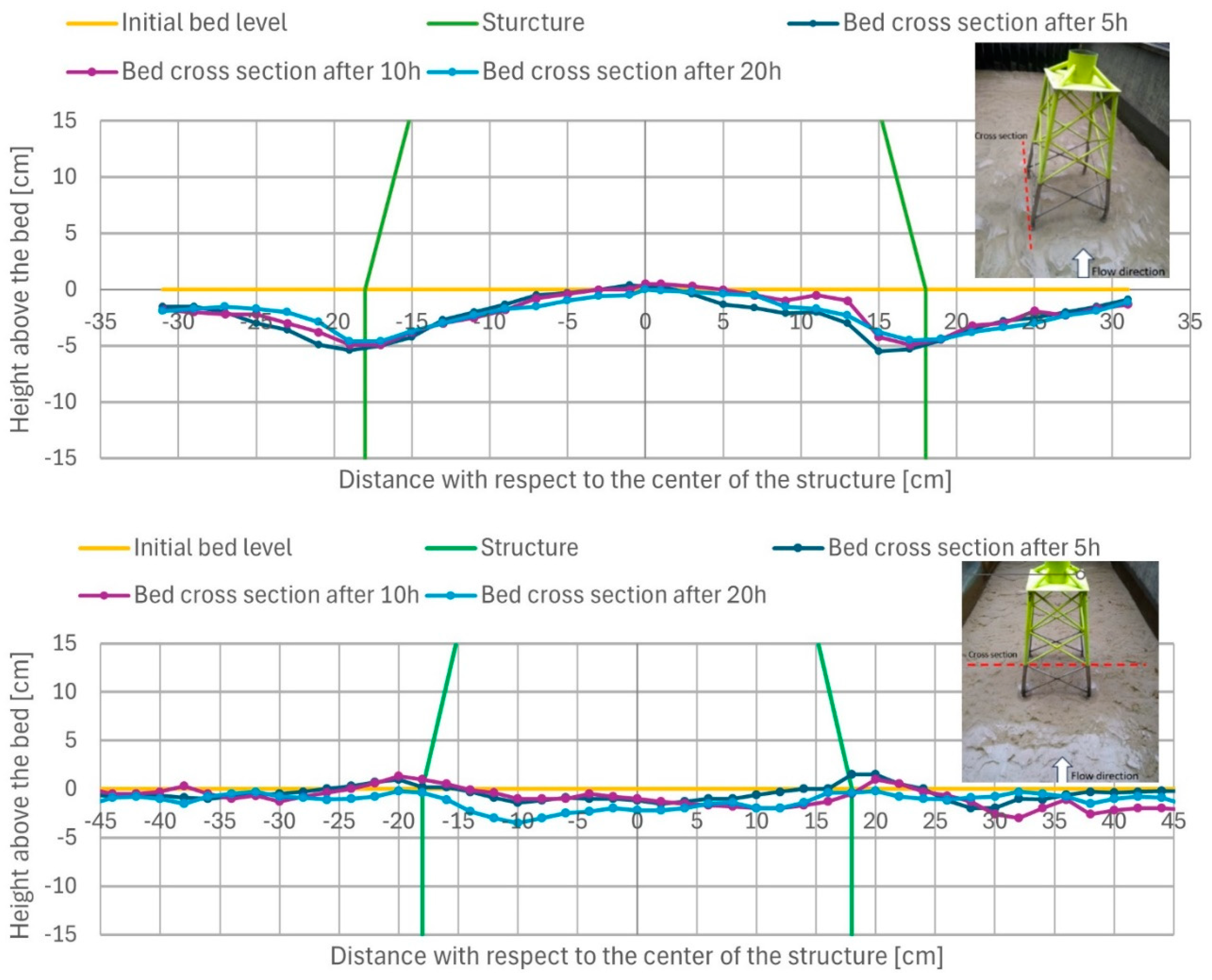

- jacket structure: maximum scour depth near legs is ds,max≅ 2.5Dleg after 20 hours; maximum scour length Ls,max≅10 Dleg at both sides; scour in center part under structure is lower (≅ 50% of scour depth near legs).

| Parameter | Monopile | Caisson with monopile (GBS) | Jacket structure |

| Maximum scour depth | 0.12 m (≅1.1Dpile) | 0.10 m (≅1.0 hcaisson) (0.3 Dcaisson) |

0.05 m near legs (≅ 2.5 Dleg) 0.03 m (≅ 1.5 Dleg) in middle structure |

| Maximum scour length | 0.35 m (≅3 Dpile) on both sides of pile | 0.3 m (1Dcaisson) on both sides | 0.20 m (≅10Dleg) on both sides of leg |

4.2. Discussion

5. Scour Modelling and Results

5.1. General

5.2. Scour near Monopile and Jacket Structure; Description of SEDSCOUR-Model

5.2.1. General Schematization

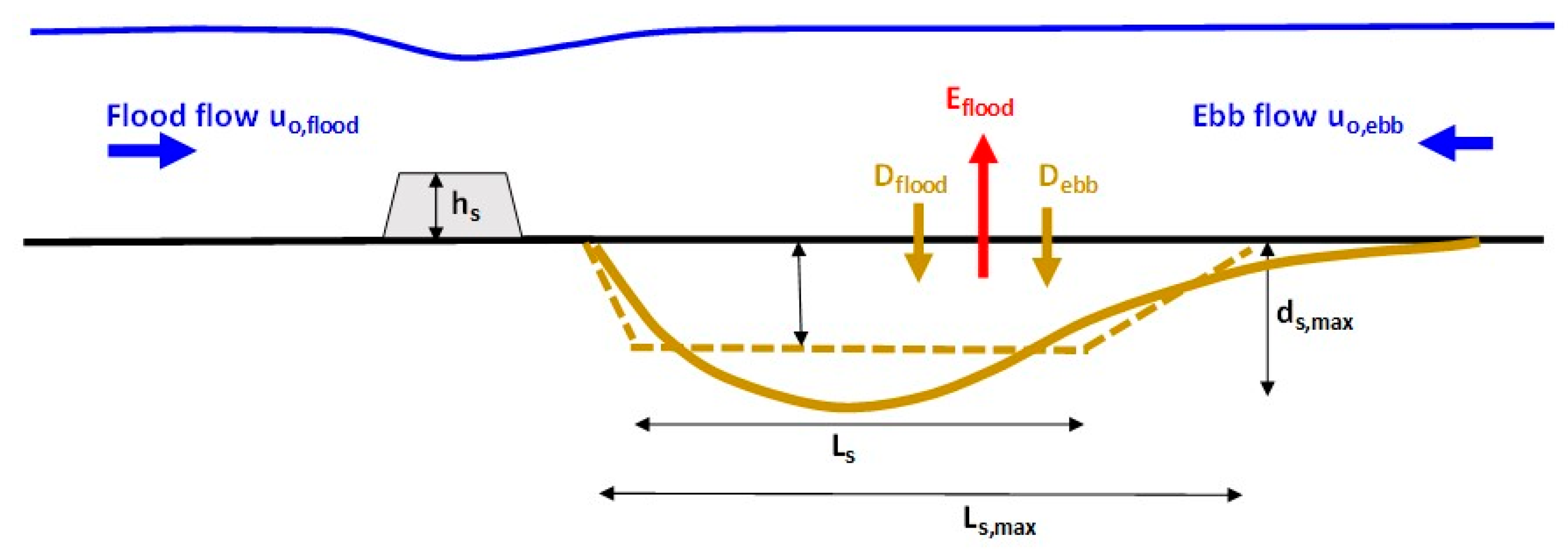

- flood: erosion of sand (Eflood) from the bed in the lee of the pile due to flow accelerations and increased turbulence levels; and deposition of sand (Dflood) from the incoming flood flow;

- ebb: deposition of sand (Debb) from the incoming ebb flow (after reversal of the tidal current).

5.2.2. General Model Equations

- qb,flood,o=flood-averaged equilibrium bed load transport outside pit based on undisturbed velocity uflood,o;

- qs,flood,o=flood-averaged equilibrium suspended load transport outside pit based on undisturbed uflood,o;

- qb,ebb,o=ebb-averaged equilibrium bed load transport outside pit based on undisturbed velocity uebb,o;

- qs,ebb,o=ebb-averaged equilibrium suspended load transport outside pit based on undisturbed uebb,o;

- qb,flood,pit=flood-averaged equilibrium bed load transport in scour pit area based on uflood,pit;

- qs,flood,pit=flood-averaged equilibrium suspended load transport in scour pit area on uflood,pit;

- αP= pickup coefficient of equilibrium suspended load transport (αp<1 for suspended load); αp=1 for bed load;

- αD,b= trapping coefficient of equilibrium bed load transport (αD=1 for bed load transport);

- αD,s= trapping coefficient of equilibrium suspended load transport (αD<1);

- tanα=downstream slope gradient of near-field scour pit (1 to 7);

- Δttide = αtide Ttide=effective time step of 1 tide; Ttide=duration of tidal cycle (≅ 12 hours); αtide =efficiency coefficient (velocities around slack tide are too small to cause substantial erosion; αtide≅ 0.4-0.6; this coefficient only affects the short term scour depth; it does not affect the long term scour depth).

- ; qs= suspended load transport (kg/m/s); D*=dimensionless particle size; ν=kinematic viscosity coefficient; γs=calibration factor (default=1).

- ; αu= velocity increase factor related to structure (range 1-1.3; input value);

- n=exponent (range 0.5-1; continuity gives n=1; lower n-value gives higher velocity in pit and thus more pickup);

- αr= turbulence factor related to structure; ro= initial turbulence effect close to structure (input); r decreases weakly for increasing scour depth (ro=0.1, 0.2, 0.3 for Dpile/ho or hstructure/ho=0.1, 0.3, 0.5; ro,max=0.3); αs=coefficient influencing turbulence factor (ro≅0.3 reduction in scour pit; ro=0=turbulence factor is constant).

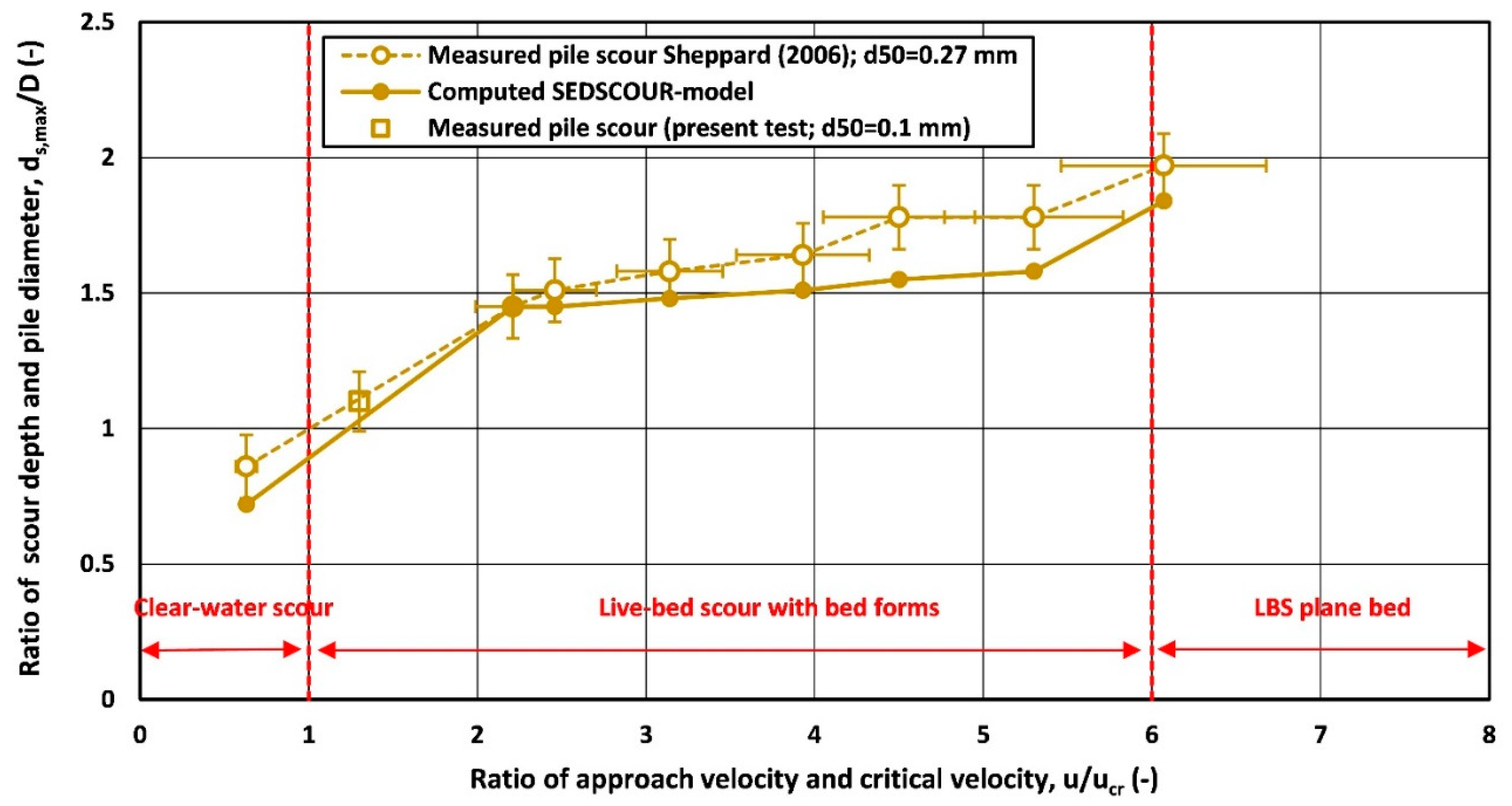

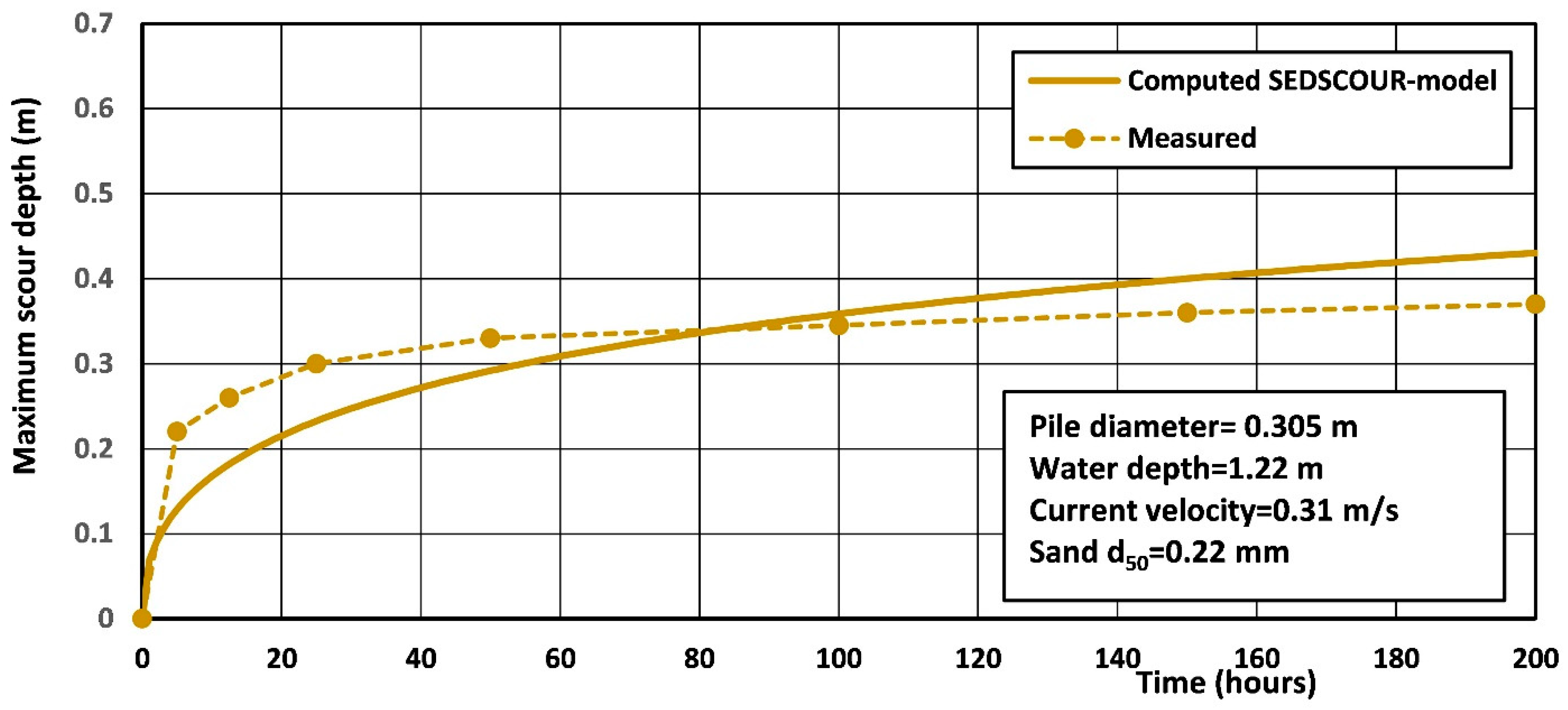

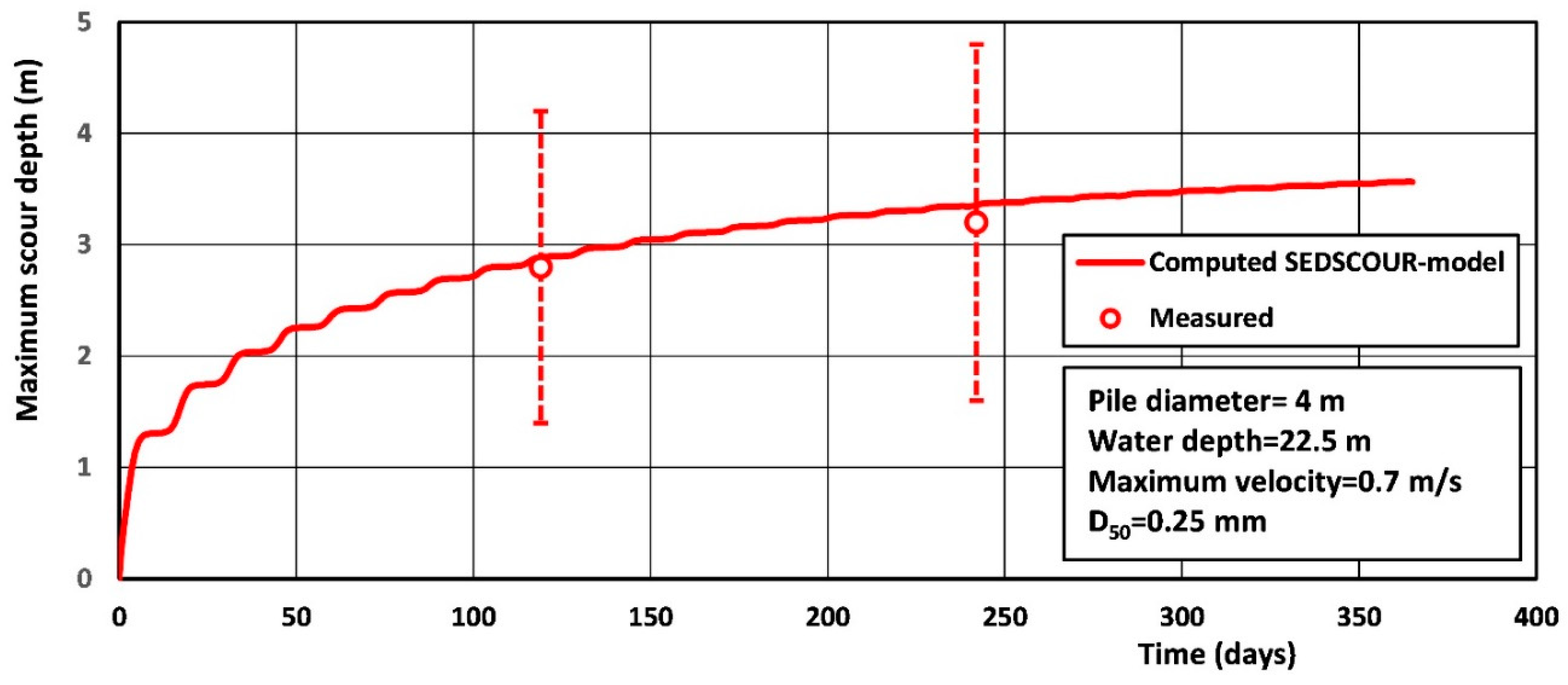

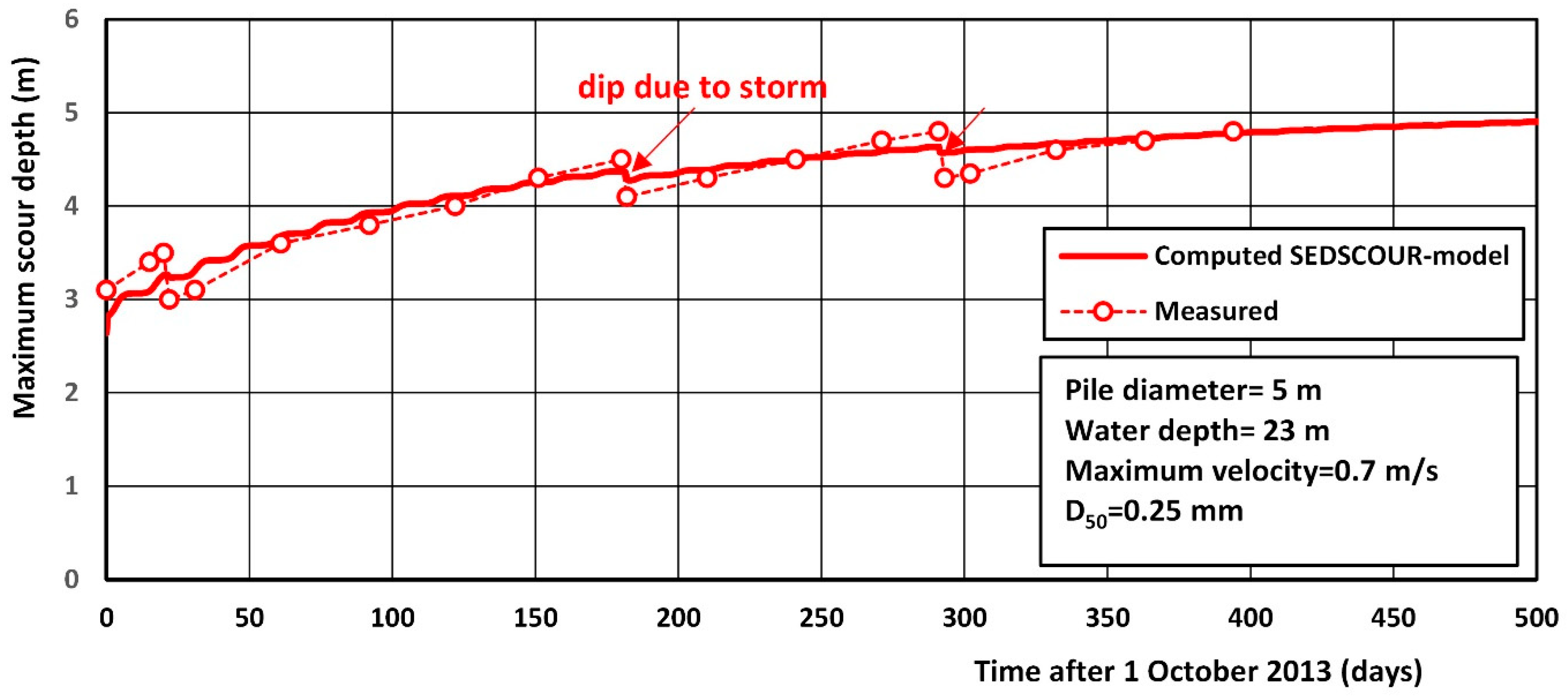

5.3. Free Scour near Monopile; SEDSCOUR-Model Results (Case A to D)

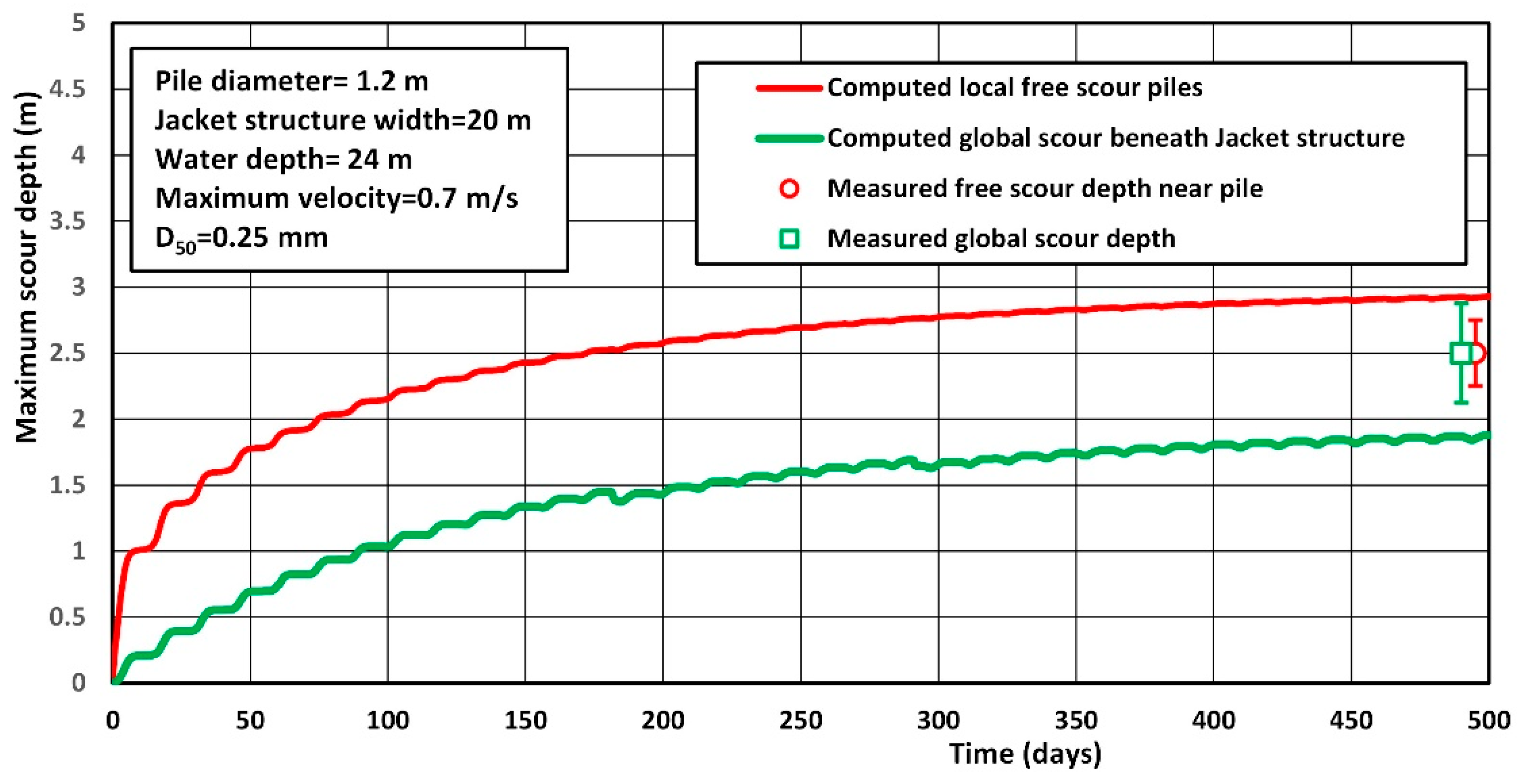

5.4. Free Scour near jacket Structure; SEDSCOUR-Model Results (Case E)

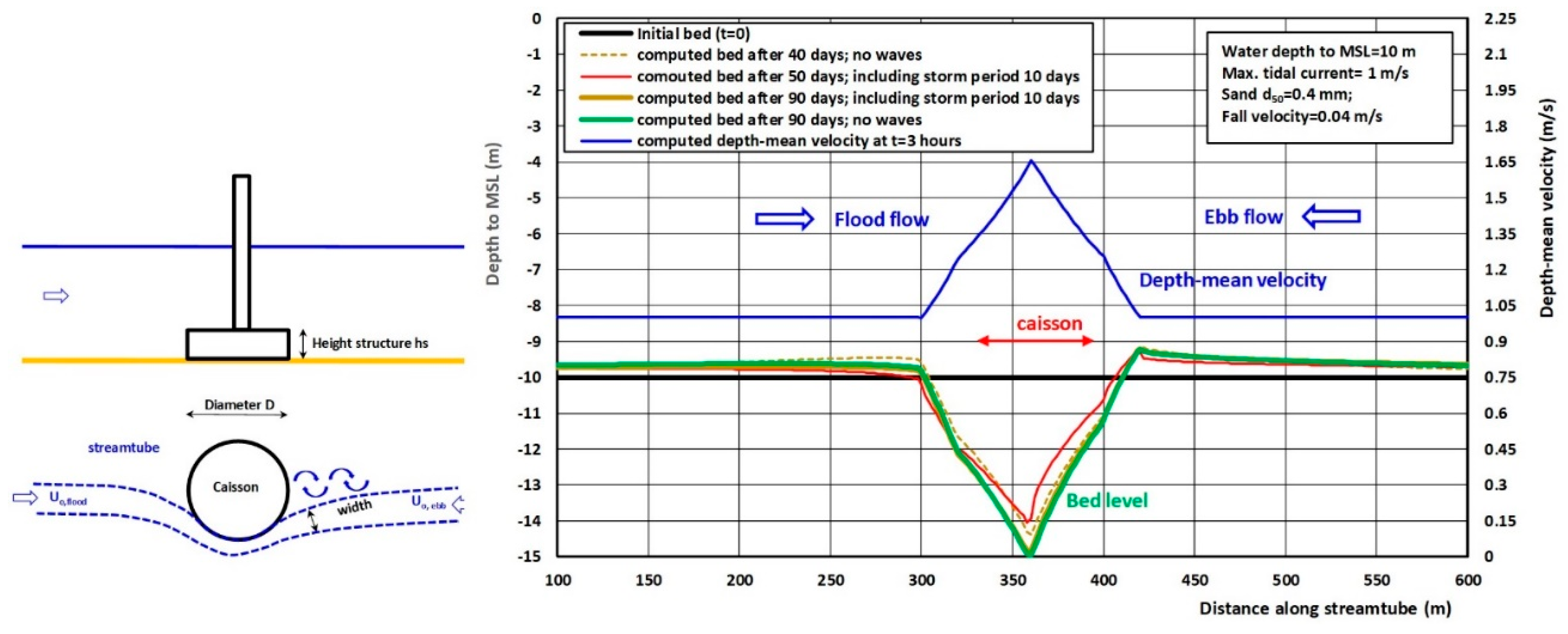

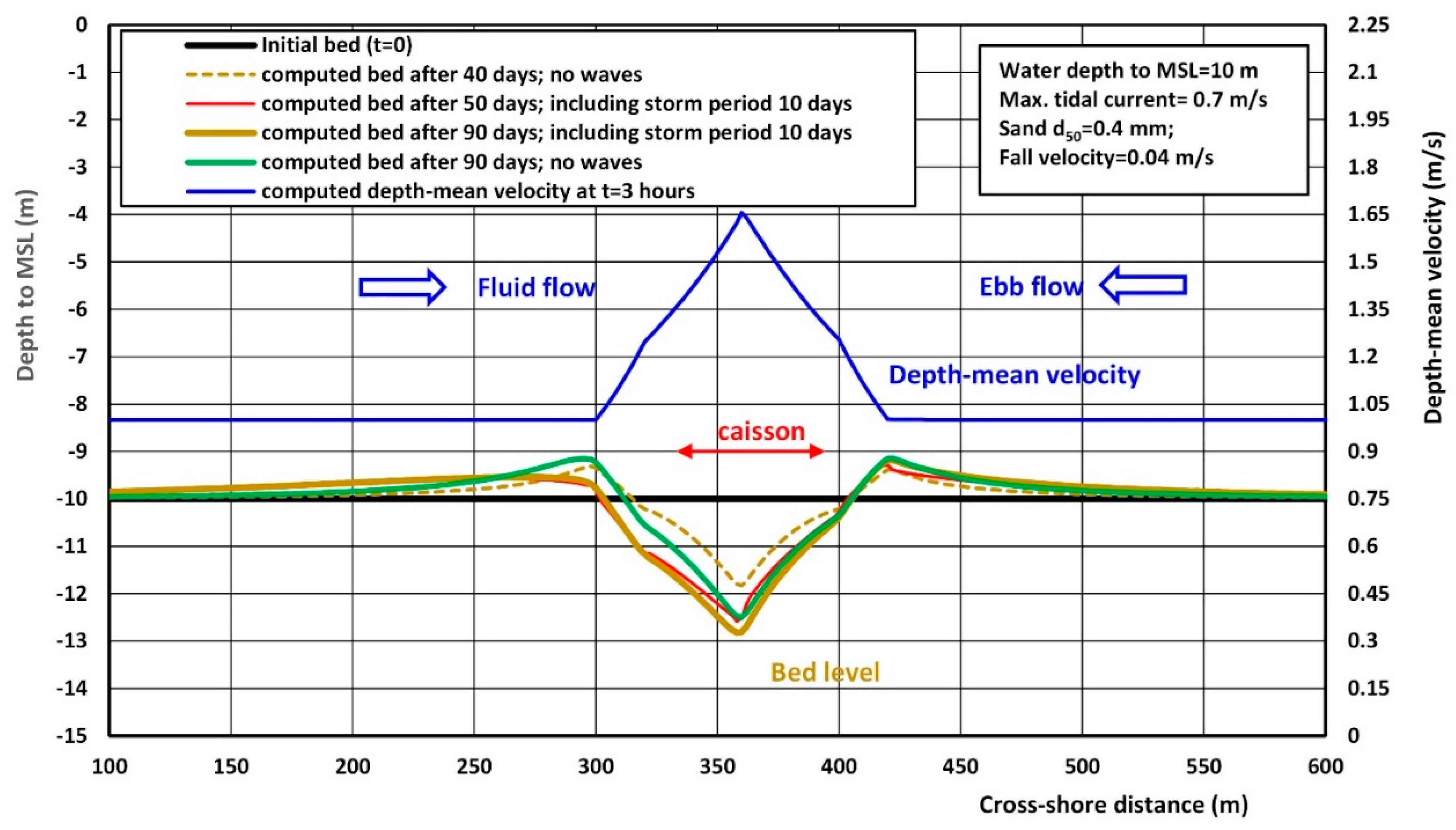

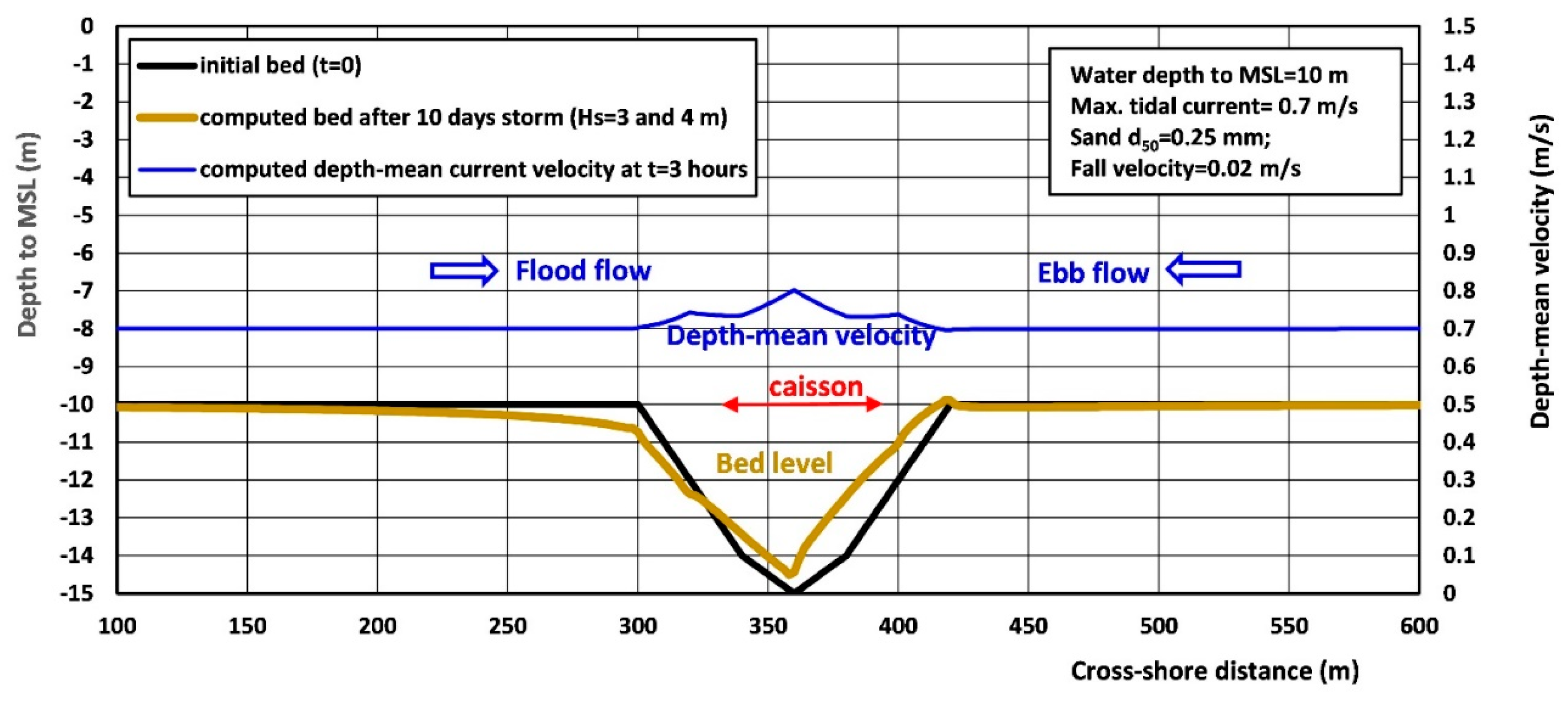

5.5. Free Scour Along Caisson Type Structure; SUSTIM2DV-Model Results (Case F)

5.5.1. General

5.5.2. Computed Flow Field of DELFT3D-Model

5.5.3. Computed Erosion in Stream Tube along Flank of Caisson

6. Summary and Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breusers, H.N.C., Nicollet, G. and Shen, H.W., 1977. Local scour around cylindrical piers. J.. Hydr. Res. Vol. 15. [CrossRef]

- Melville, B.W., 1988. Scour at bridge sites., p. 327-362. Technomic Publishing Company, USA, Civil Engineering Practice, 2.

- Melville, B.W. and Sutherland, A.J., 1988. Design method for local scour at bridge piers. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, ASCE, Vol. 114, No. 10. [CrossRef]

- Kothyari, U.C. et al., 1992. Live-bed scour around cylindrical bridge piers. J. of Hydr. Res., IAHR, Vol. 30 (5). [CrossRef]

- Melville, B.W., 1997. Pier and abutment scour: integrated approach. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, Vol. 123 (2). [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.Y., 1997. Equilibrium clear-water scour around an abutment. J. of Hydraulic Engineering, Vol. 123, No. 3. [CrossRef]

- Melville, B.W. and Coleman, S.E., 2000. Bridge scour. Water resources Publications. Littleton, Colorado, USA.

- Cefas, 2006. Scroby sands offshore wind farm; coastal processes monitoring. Cefas Lowestoft Laboratory, UK.

- Rudolph, D., Raaijmakers, T. and Stam, C.J., 2008. Time-dependent scour development under combined current and wave conditions; hindcast of field measurements. 4th International Conference on scour and erosion, Tokyo.

- Raaijmakers, T.C., Van Velzen, G. and Riezebos, H.J., 2014. Dynamic scour prediction for offshore monopiles. Proceedings of 7th Int. Conf. Scour and Erosion. 2-4 December 2014, Perth, Australia.

- Whitehouse, R.S.J., 2004. Marine scour at large foundations. 2snd Int.l Conference on Scour and Erosion, Singapore.

- Whitehouse, R., Harris, J., Sutherland, J. and Rees, J., 2008. An assessment of field data for scour at offshore wind turbine foundations. Fourth International Conference on scour and erosion, Tokyo.

- Whitehouse, R., Harris, J. and Sutherland, J., 2012. Evaluating scour at marine gravity structures. HR Wallingford; ICE-Maritime Engineering, Vol. 164, 143-157.

- Simons, R.R., Weller, J. and Whitehouse, R.J.S. 2009. Scour development around truncated cylindrical structures. Coastal Structures 2007, Proceedings of the 5th Coastal Structures International Conference, CSt07, Venice, Italy, 2-4 4 July 2007, (Eds) Franco, L., Tomasicchio, G.R. and Lamberti, A., 1881-1891. World Scientific.

- Tavouktsoglu, N.S., 29017. Scour and scour protection around offshore gravity-based foundations. Doctoral Thesis, University College, London,UK.

- Sarmiento, J., Guanche, R., Losada, I.J. and Serna, J. 2024.Experimental analysis of scour around an offshore wind gravity base foundation. Ocean Engineering Vol. 308, Doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.118330. [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, R., Bos, K.J., Luijendijk, A.P., Rietema, K. and Out, J.M.M., 2004. Scour around offshore structures; analysis of field measurements, Deltares, Delft, The Netherlands.

- Bolle, A., de Winter, J., Goossens, W., Haerens, P. and Dewaele, G., 2012. Scour monitoring around offshore jackets and gravity based foundations. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Scour and Erosion, ICSE 6, Paris, France, 27–31 August 2012.

- Baelus, L., Bolle, A. and Szengel, V., 2018 Long term scour monitoring around offshore jacket foundations on a sandy seabed. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Scour and Erosion, ICSE 9, Taipei, Taiwan, 5–8 November 2018.

- Welzel, M., Schendel, A., Schlurmann, T. and Hildebrandt, A., 2019. Volume-based assessment of erosion patterns around a hydrodynamic transparent offshore structure. Energies, Vol. 12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Zhang, P., Guo, Y., Ji, Y. and Fu, R., 2025. Large eddy simulation of the flow field characteristics around a jacket foundation under unidirectional flow actions. Ocenan Engineering, Vol. 137. [CrossRef]

- Chambel, J., Fazeres-Ferradosa, T., Miranda, F., Bento, A.M, Taveiro-Pinto, F. and Lomonaco, P., 2024. A Comprehensive Review on Scour and Scour Protections for Complex Bottom-Fixed Offshore and Marine Renewable Energy Foundations. Ocean Engineering, Vol. 304 (8). [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn, L.C., Meijer, K., Dumont, K. and Fordeyn, J.,2024a. Practical 2DV modelling of deposition and erosion of sand and mud in dredged channels due to currents and waves. Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal and Ocean Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn, L.C., Meijer, K., Dumont, K. and Fordeyn, J., 2024b. Simulation of sand and mud transport processes in currents and waves by time-dependent 2DV model. International Journal of Sediment Reserch. [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn, L.C., 1993, 2012. Principles of sediment transport in rivers, estuaries and coastal seas. Aqua Publications, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Available online: www.aquapublications.nl.

- Van Rijn, L.C., 2007a. Unified view of sediment transport by currents and waves, I: Initiation of motion, bed roughness, and bed-load transport. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, Vol. 133 (6),649-667. [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn, L.C., 2007b. Unified view of sediment transport by currents and waves, II: Suspended transport. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, Vol. 133 (6), 668-389. [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.M. and Miller, W., 2006. Live-Bed local pier scour experiments. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, ASCE, Vol. 132, No.7 , 635-642. [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.M., 2003. Large scale and live bed local pier scour experiments (phase 1). Final Report Florida Department of Transportation FDOT, USA.

- Deltares 2017. Scour and scour mitigation; Hollandse Kust Zuid Wind Farm Zone. Delft, The Netherlands.

| Parameter | Monopile | Caisson with monopile (GBS) | Jacket structure |

| Structure dimensions | Dpile=0.11 m (pile diameter) |

Dcaisson=0.32 m; Dpile=0.11 m hcaisson=0.1 m; hskirt=0.035 m (caisson was placed on top of bed; skirt was in the bed) |

Dleg=0.02 m Dcrossmember=0.01 m Lbase=0.365 m (distance legs) |

| Water depth | 0.35 m | 0.35 m | 0.35 m |

| Upstream current | 0.26 m/s | 0.27 m/s | 0.26 m/s |

| Test |

Cur rent (m/s) |

Mea sured scour depth ds,max (m) |

Com puted scour depth ds,max (m) |

Bed and suspended load coefficients γb, γs (-) |

Bed rough ness ks (m) |

Turbu lence coeffi cient ro (-) |

Velocity increase coeffi cient αu (-1) |

Pickup coeffi cient αP (-) |

Trap ping coeffi cient αD (-) |

Scour length coeffi fcient αL (-) |

Time scale (hours) |

| 1 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.1 | default=1 | 0.03 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | 200 |

| 2 | 0.62 | 0.22 | 0.21 | default=1 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | 2 |

| 8 | 0.69 | 0.23 | 0.22 | default=1 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | 1 |

| 3 | 0.88 | 0.24 | 0.23 | default=1 | 0.02 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | <1 |

| 4 | 1.10 | 0.25 | 0.255 | default=1 | 0.01 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | <1 |

| 5A | 1.26 | 0.27 | 0.26 | default=1 | 0.005 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | <1 |

| 5B | 1.43 | 0.27 | 0.275 | default=1 | 0.003 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | <1 |

| 6 | 1.64 | 0.3 | 0.3 | default=1 | 0.003 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | <1 |

| Test |

Cur rent (m/s) |

Mea sured scour depth ds,max (m) |

Com puted scour depth ds,max (m) |

Bed and suspended load coefficients γb, γs (-) |

Bed rough ness ks (m) |

Turbu lence coeffi fcient ro (-) |

Velocity increase coeffi fcient αu (-) |

Pickup coeffi cient αP (-) |

Trap ping coeffi cient αD (-) |

Scour length coeffi cient αL (-) |

Time scale (hours) |

| 12 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.43 | default | 0.03 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 3 | 200 |

| Parameter |

Wind park Q7 North Sea (NL) Case C |

Luchterduinen North Sea (NL) Case D |

Global and free scour L9 Jacket North Sea (NL) Case E |

| Pile diameter (m) | 4 | 5 | 1.2 |

| Water depth to Mean Sea level (m) | 22.5 | 23 | 22.5 |

| Maximum tidal velocity Spring (m/s) Maximum tidal velocity Neap (m/s) |

0.7 0.3 |

0.7 0.3 |

0.7 0.3 |

| Tidal range (m) | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Significant wave height Hs (m) and peak period Tp (s) |

1; 7 | 1; 7; 3 storms | 1; 7 |

| Sand diameter d50 (mm) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Percentage fines/mud < 63 μm (%) | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Fall velocity sand ws (m/s) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Critical velocity ucr (m/s) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Bed roughness ks (m) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Velocity increase coefficient αu (-) | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Turbulence coefficient ro (-) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Pickup coefficient αP (-) | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1 |

| Trapping coefficient suspended sand transport αD (-) |

0.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Pit length coefficient αL (-) | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Calibration factor bed and suspended load γb, γs (-) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).