Submitted:

15 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

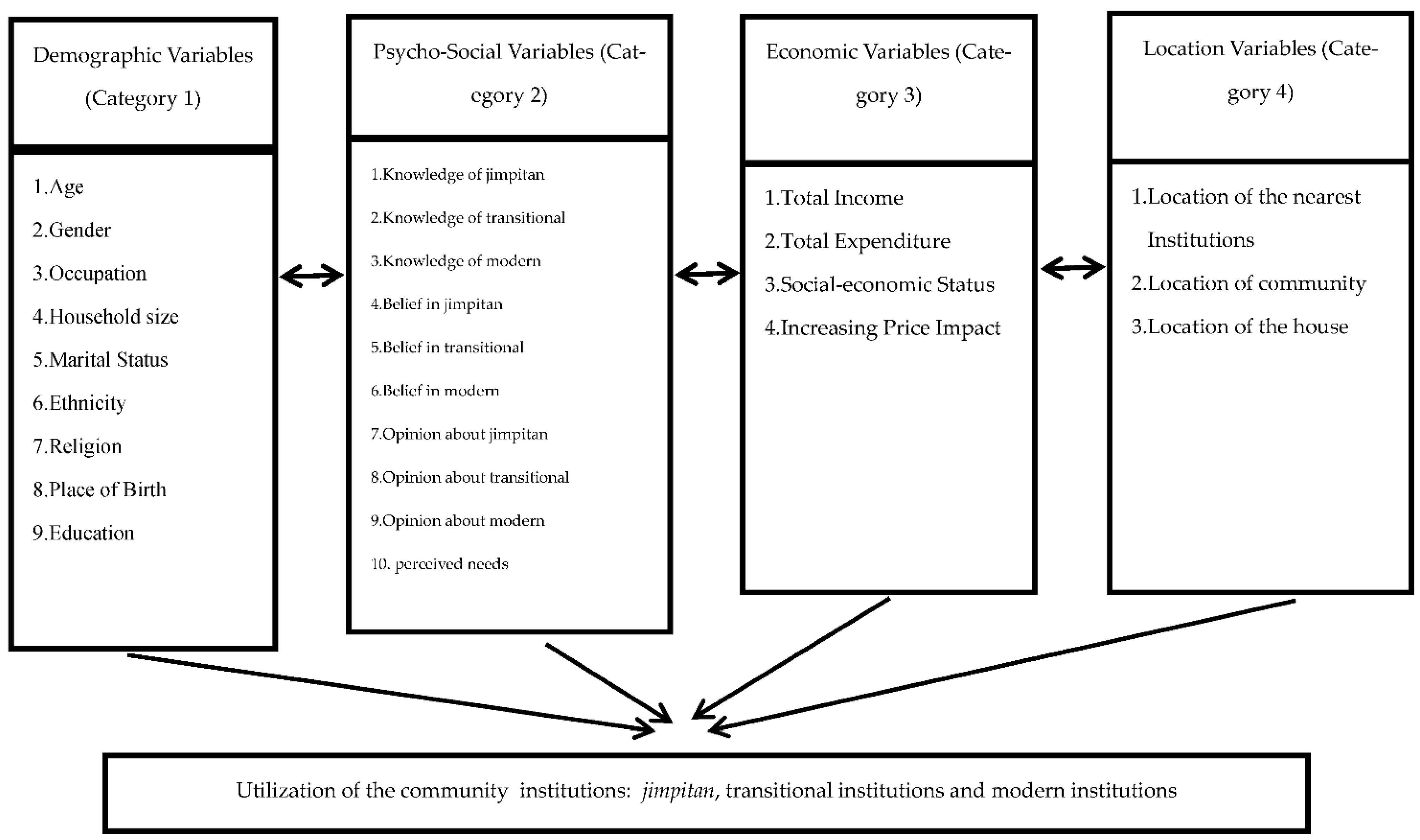

Indigenous institutions may play a vital role in sustainable development at the local level by serving the people’s interests and supporting their livelihood. By spreading structured questionnaires to the households in our research area, this research aims to find the determinant factor of the utilization of community institutions, especially the indigenous institutions. Per household, 26 features, including demographic, psycho-social, economic, and location variables, were collected to study the predictability of the utilization of the community institutions. The results show that the location variables are the most crucial for explaining the utilization of the community institutions in times of need.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Method

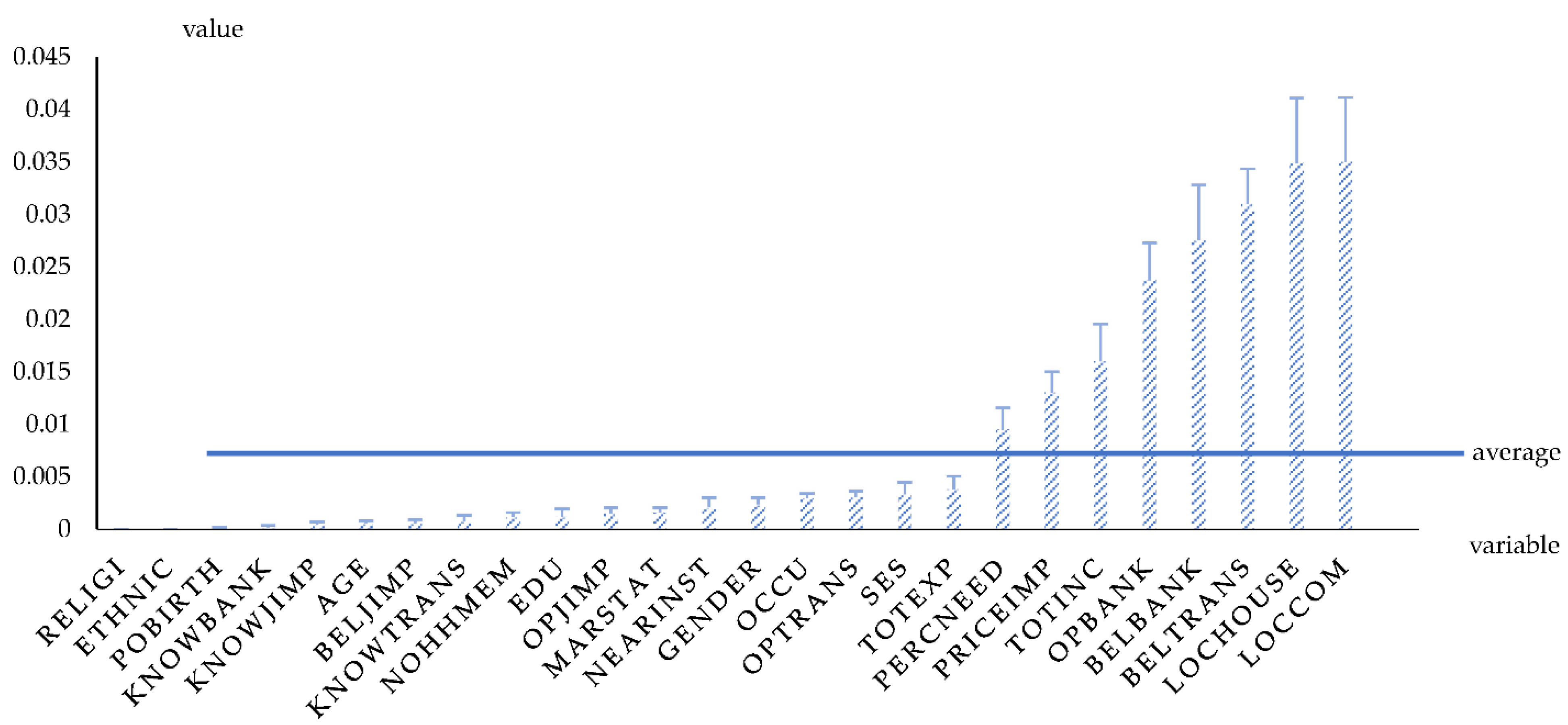

- The importance of independent variables for prediction institutions’ utilization. The Random Forest approach figures out the importance of the variables in predicting the utilization of the community institutions, by calculating the accuracy of the prediction by the Random Forest approach based on all independent variables minus the variable of concern. The difference in accuracy between the prediction of the complete Random Forest and that of Random Forest minus the variable of concern is called the importance value. Variable importance was calculated ten times in order to assess the variability of the importance due to random steps within the Random Forest approach. The independent variables with an importance variance not including zero were regarded as having an importance value that is significantly higher than zero, and were called non-zero variable. The higher the importance value, the larger the predictive power of the variable.

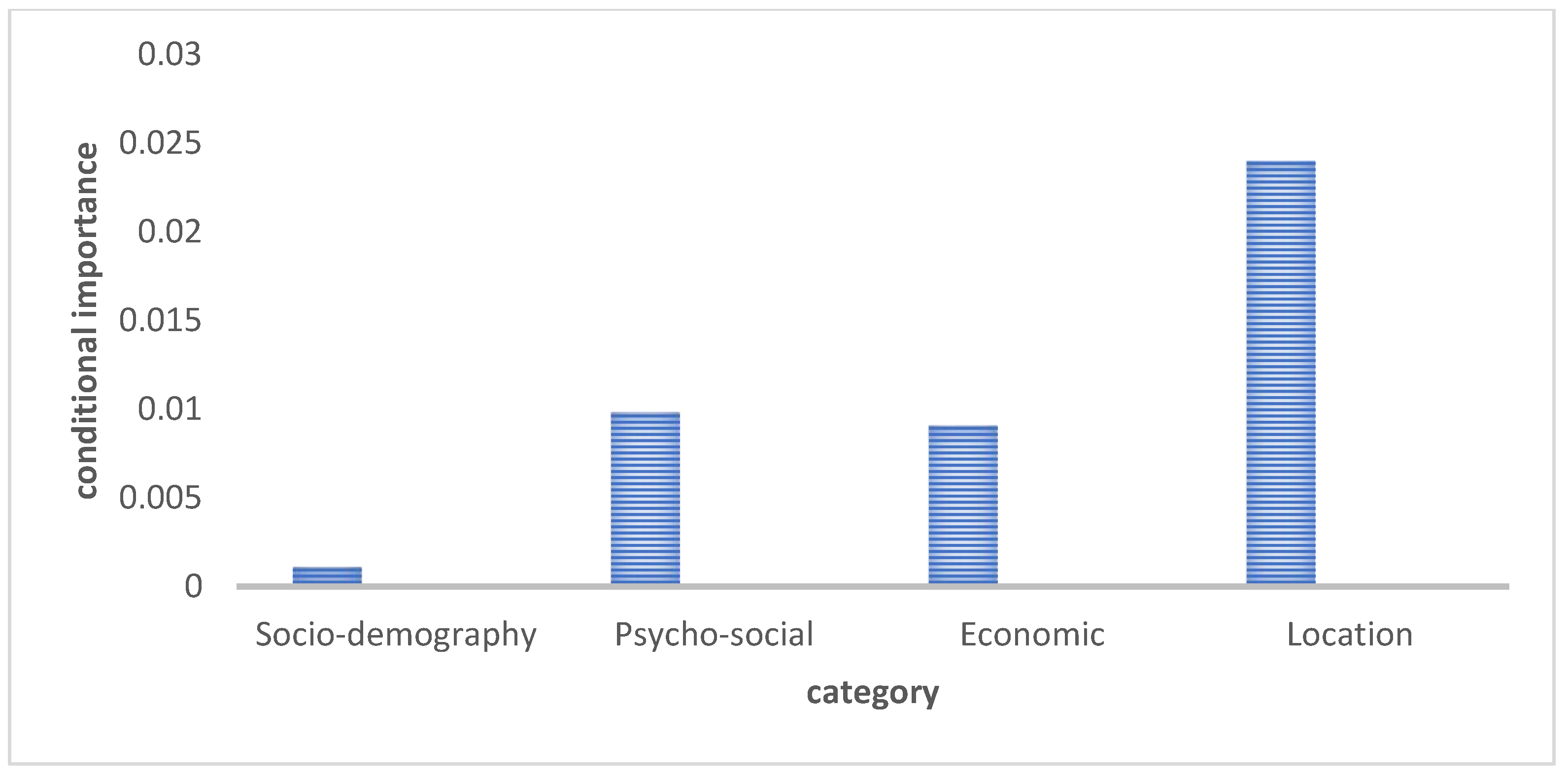

- The average importance per variable category was to capture which category best explained the utilization of institutions. By averaging the importance value of variables in each category and checking with a permutation test whether it is significantly higher than the average of a random sample of the variables, we would know which category significantly influenced the utilization of institutions. The permutation test is conducted by taking a fixed number of variables equal to the number in that category randomly out of all variables (ie., for category one, nine out of 26 variables; for category two, ten out of 26 variables; for category three, four out of 26 variables; and for category four, three out of 26 variables), calculate the average, and repeat this 1000 times to get the distribution of the random average. When the actual average of the importance of the variables in the category is higher than the 95 per-centiles of that distribution, the average is considered significantly higher than the random average. The permutation test in this form is an exact one-sided test.

3. Results

3.1. The Correlation Test (Cramer’s V and Chi-Square)

3.2. The importance of variables for prediction institutions’ utilization

3.3. The average importance per variable category value

4. Discussion

4.1. General Results

4.2. The importance of variables for prediction institutions’ utilization

4.3. The average importance per variable category value

5. Conclusion

References

- WCED. (1987). Our Common Future. . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kohler, J. (2014). Globalisation and Sustainable Development: Case Study on International Transport and Sustainable Development. Journal of Environment & Development, 66–100.

- Barkemeyer, R. , Holt, D., Preuss, L., & Tsang, S. (2014). What happened to the development in ‘Sustainable Development?’. Sustainable Development, 15-32.

- De Graaf, H.J. , Musters, C.J.M., & ter Keurs, W.J. (1995). Sustainable Development: Looking for A New Strategies. Ecological Ecvonomics, 16 (1996), 205-216.

- Uphoff, N. (1992). Local Institutions and Participation for Sustainable Development. UN System Task Team on The Post-2015 UN Development Agenda, Thematic Think Piece.

- . Watson, E. (2003). Examining the Potential of Indigenous Institutions for Development: A Perspective from Borana, Ethiopia. Development Change, 287-310.

- . Whyte, K.P. (2013). On the Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as A Collaborative Concept: A Philosophical Study. Ecological Processes, 1-12.

- FAO. (2009). Pro-Poor Policy Options: Empowering Indigenous Institutions in Indonesia. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/b778a1b2-13ef-4232-91e9-a1aa227fc2f9/.

- Szirmai, A. (2015). Socio-Economic Development (2nd ed). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- . Shohibussirri, M. (2014). Gotong Rotong and Sambatan: Analysis and Comparison of Indonesian and Javanese Cultural Keyword Using NSM. Working Paper ANU, 1-25.

- . Bowen, J.R. (1986). On the Political Construction of Tradition: Gotong Royong in Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Studies, 545-561.

- . Nugroho, H. (2004). Memerangi Delegitimasi Institusi Lokal. Jurnal Pembangunan Pedesaan, 173-186.

- Mukherjee, N. (1999). Consultation With the Poor in Indonesia. Washington: The World Bank.

- Farasonalia, R. (2020). Hadapi Corona, Ganjar minta Desa Hidupkan Lagi Tradisi Jimpitan Untuk Lumbung Pangan. Retrieved from https://regional.kompas.com/read/2020/04/02/23161761/hadapi-corona-ganjar-minta-desa-hidupkan-lagi-tradisi-jimpitan-untuk-lumbung?lgn_method=google.

- Humas jateng. (2020). Warga Perumahan SUPM Tegal Wujudkan Program Jogo Tonggo. Retrieved from https://humas.jatengprov.go.id/detail_berita_gubernur?id=4294.

- Lont, H. (2005). Juggling Money: Financial Self-Help Organizations and Social Security in Yogyakarta. Leiden: KITLV Press.

- FAO. (2004). Statement on the Official Lunch: The International Year of Rice. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/3/Y5167E/y5167e02.htm.

- Rusnandar, N. (2016). Beas Perelek: Pemberdayaan Masyarakat di Kabupaten Purwakarta. Patanjala Journal, 301-316.

- Saefullah, K. (2019). Gintingan in Subang: An Indigenous Institution for Sustainable Community-Based Development in the Sunda Region of West Java, Indonesia. Leiden: Leiden University.

- Yulhendri. , Kurniawati, T. & Susanti, N. (2018). Strategi Investasi Pada Rumah Tangga Petanu Tradisional di Kecamatan Mapattungul Selatan. ( 2018). Strategi Investasi Pada Rumah Tangga Petanu Tradisional di Kecamatan Mapattungul Selatan. Jurnal Ekonomi Pendidikan dan Kewirausahaan, 15–30.

- Esiobu, N.S. , Nkete, G.A., Ejiougu, A.O., & Onubuogu, G.C. (2015). Analysis of Use of Ajo in Financing Cassava Production in Aniocha North Local Government of Delta State, Nigeria. C. ( Investment and Development, 1–21.

- Aredo, D. (1993). The Iddir: A Study of an Indigenous Informal Financial Institution in Ethiopia. Savings and Development, 77-90.

- Ang, G, R. (1979). The Bayanihan Spirit: Dead or Alive? Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, 91-93.

- Ealdama, Y. (2012). Bayanihan: The Indigenous Philipino Strengths Perspective. International Conference on Strengths-Based Practice in Social Work and Human Services (pp. 1-13). Kathmandu: University of Philipine.

- Seibel, H.D. (2001). Mainstreaming Informal Financial Institutions. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 83-95.

- Aliber, M. (2015). The Importance of Informal Finance in Promoting Decent Work Among Informal Operators: A Comparative Study of Uganda and India. Working Paper ILO, 11-30.

- Yami, M. , Vogl, C, & Hausera, M. (2009). Comparing The Effectiveness of Informal and Formal Institutions in Sustainable Common Pool Resources Management in Sub-Saharan Africa. Conservation & Society, Vol. 7, No.

- World Bank. (2009). Improving Access to Financial Services in Indonesia. New York: World Bank.

- Jayanti, A.D. , Agusti, K.S. & Setyawati, Y. (2021). Barriers to Access Formal Financial Services: An Empirical Study from Indonesia. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 97-106.

- Swaningrum, A. (2023). Jimpitan in Wonosobo, Central Java: An Indigenous Institutions in the Context of Sustainable Socio-Economic Development in Indonesia. Leiden: Leiden University.

- (1999). Ethnoscience, ‘TEK’ and its Application to Conservation. In: D.A. Posey (Ed.), Cultural and Spiritual Values of Biodiversity: A Complementary Contribution to the Global Biodiversity Assessment (pp. 196-177). London/Nairobi: Intermediate Technology Publications.

- Musters, C.J.M. & van Bodegom, P.M. (2018). Analysis of Species Attributes to Determine Dominant Environmental Drivers, Ilustrated by Species Decline in the Netherlands since the 1950s. Biological Conversation, 68-77.

- Breiman, L. (2001). Random Forests. Machine Learning, 5-32.

- Cutler, A. , Cutler, D.R. & Stevens, J.R. (2012). Random Forest. In Ensemble machine learning (pp. 157-175). S: New York.

- Strobl, C. , Malley, J. & Tutz, G. (2009). An Introduction to Recursive Partitioning: Rationale, Application and Characteristics of Classification and Regression Trees, Bagging and Random Forests. . Psychol Methods, 323-348.

- Hothorn, T. , Hornik, K., & Zeileis, A. (2006). Unbiased Recursive Partitioning:A Conditional Inference Framework. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statiztics, 15(3), page 651-674.

- Zeileis, A. , Hothorn, T., & Hornik, K. (2008). Model-Based Recursive Partitioning. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 17(2), 492-514.

- Kassambara, A. (2023). Rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests. Computer Science.

- Matsumoto, D. Culture and Psychology: People Around the World. 2nd ed. Wadsworth: Marceline.

- Uphoff, N. (2000). Understanding Social Capital: Learning from The Analysis and Experience of Participation. In: Dasgupta, P. & Serageldin, I (ed.). Social Capital: A multifaceted Perspectives on Development Series (pp. 173-215). Washington D.C: World Bank.

- Beard, V.A. (2007). Household Contribution to Community Development in Indonesia. World Development, 607–625.

- Marsh, R. (2003). Working With Local Institutions to Support Sustainable Livelihoods. Rome: FAO.

- Djankov, S. Djankov, S., Miranda, P., Seira, E., & Sharma, S. (2008). Who Are the Unbanked?. Policy Research Working Paper.

- Kendall, J. Kendall, J., Mylenko, N., & Ponce, A. (2010). Measuring Financial Access Around the World. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper WPS 5253, 1-65.

| Name of the village | Type of area | Geographic area of Wonosobo | Number of households |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kejajar | Highland/Rural | Northern area | 51 |

| Kalibeber | Lowland/Sub-urban | Central area | 50 |

| Wonosobo Barat | Lowland/Urban | Central area | 46 |

| Sojokerto | Lowland/Rural | Western area | 52 |

| Total number of households | 199 | ||

| Village | Utilization of the community institutions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village Name | Indigenous | Transitional | Modern | Total | |||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | |

| Kejajar | 41 | 80.4 | 2 | 3.9 | 8 | 15.7 | 51 |

| Kalibeber | 9 | 18.0 | 31 | 62.0 | 10 | 20.0 | 50 |

| Wonosobo Barat | 1 | 2.2 | 16 | 34.8 | 29 | 63.0 | 46 |

| Sojokerto | 13 | 25.0 | 12 | 23.1 | 27 | 51.9 | 52 |

| Total | 64 | 32.2 | 61 | 30.6 | 74 | 37.2 | 199 |

| Category | 95 percentile | n | Mean | Sign |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-Demography | 0.013497 | 9 | 0.001094 | |

| Psycho-Social | 0.012797 | 10 | 0.009814 | |

| Economic | 0.017877 | 4 | 0.009062 | |

| Location | 0.020554 | 3 | 0.023986 | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).