Submitted:

15 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

- COVID-19-related terms: “COVID-19,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “coronavirus infection”

- Surgical terms: “emergency surgery,” “urgent surgery,” “general surgery”

- Outcome measures: “mortality,” “complications,” “postoperative outcomes,” “ICU admission,” “mechanical ventilation”

Results

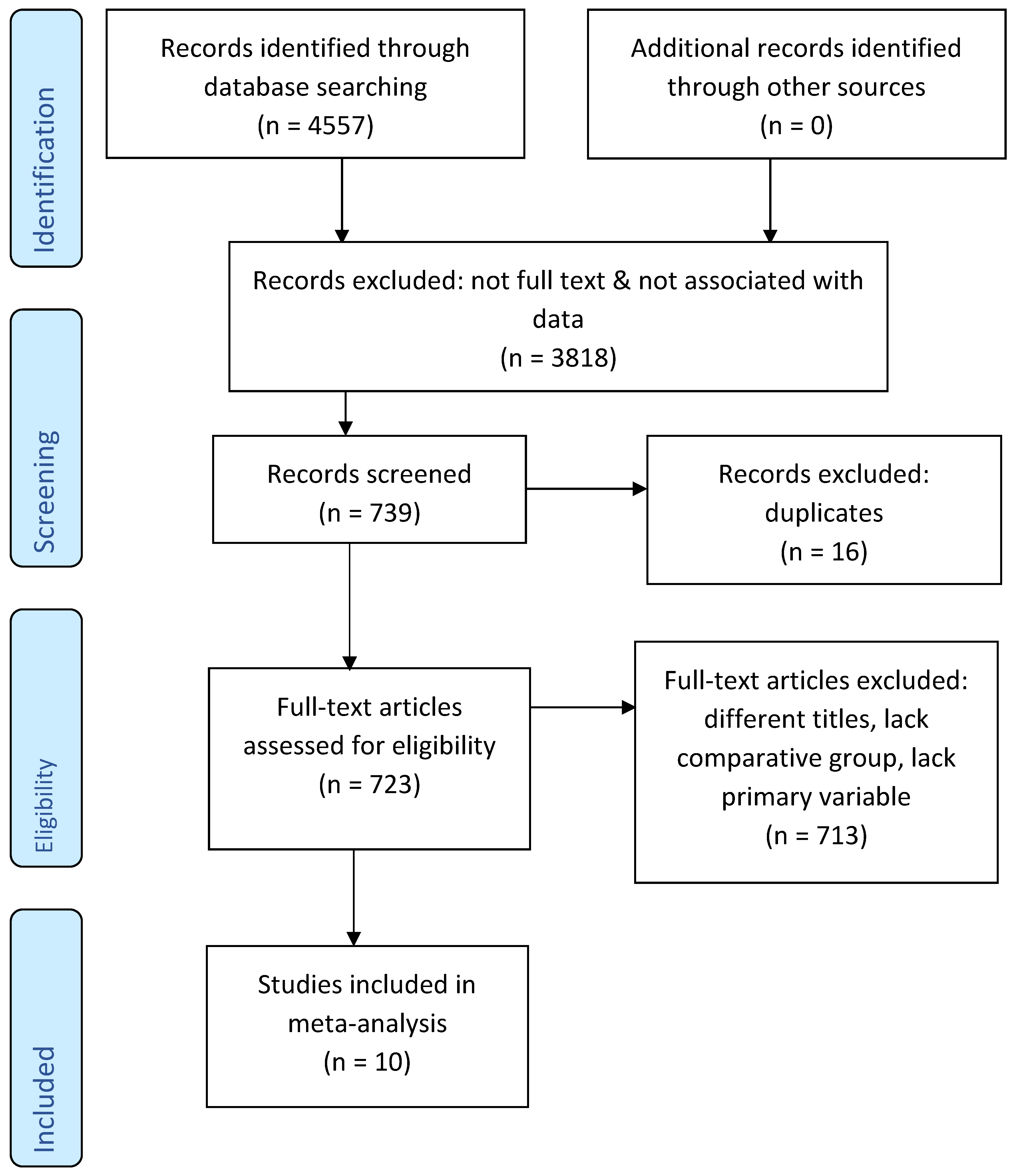

Study Selection and Characteristics

Outcomes Variables

| Study No. | Selection Bias | Reporting Bias | Confounding Bias | Measurement Bias | Generalizability Bias | Information Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 2 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 3 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| 4 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 5 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 6 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 7 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 8 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 9 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 10 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

Discussion

Strengths

- Comprehensive and rigorous methodology adhering to PRISMA guidelines.

- Inclusion of diverse study designs across multiple geographical regions, enhancing generalizability.

- Robust statistical analyses to ensure result reliability.

Limitations

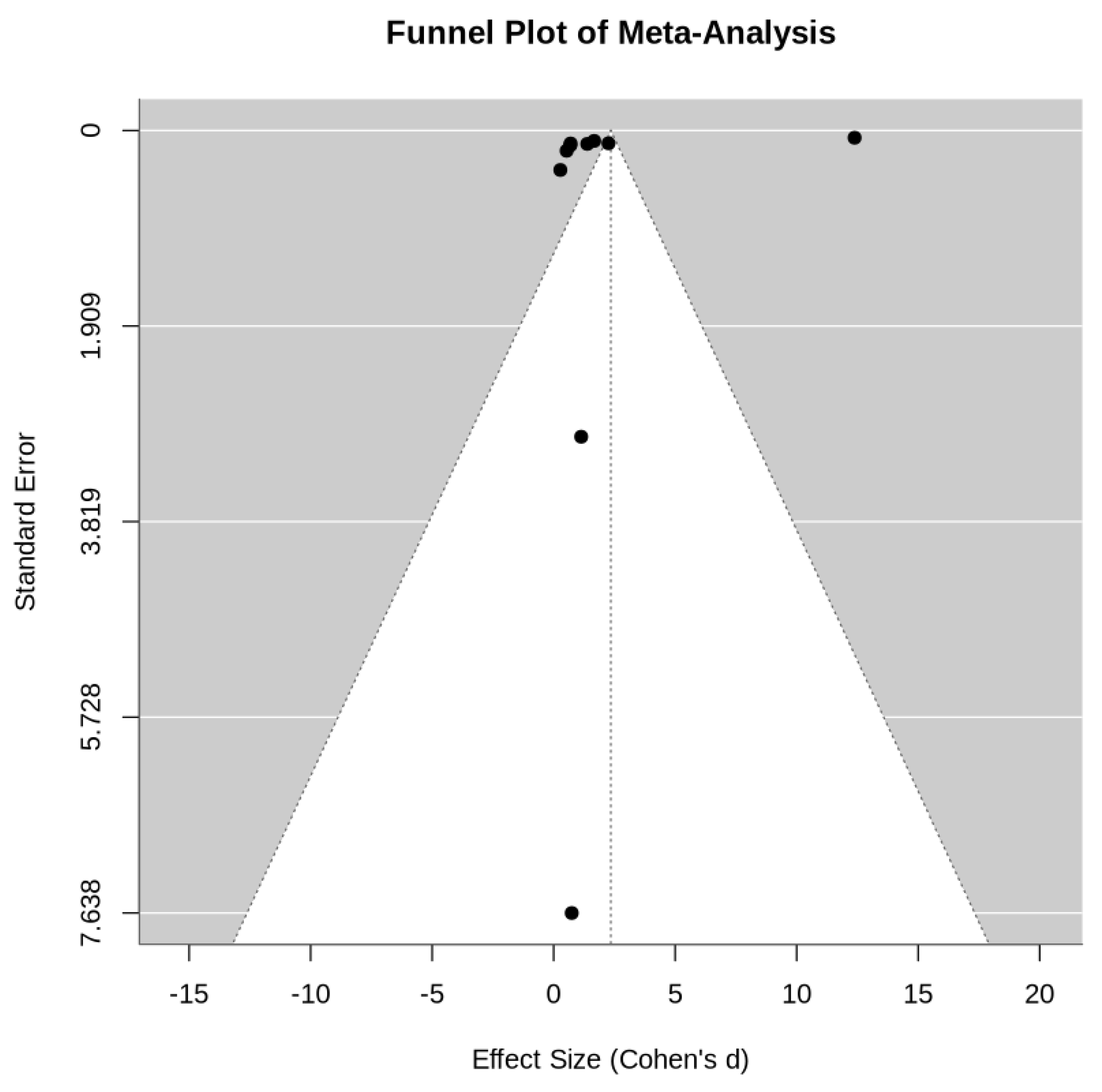

- Markedly high heterogeneity (I2 = 99.86%), likely reflecting variations in healthcare infrastructure, patient populations, and surgical practices.

- Potential publication bias, as suggested by funnel plot asymmetry.

- Limited availability of high-quality randomized controlled trials, with most data derived from observational studies.

Future Directions

- Prospective, multicenter studies to validate these findings and elucidate underlying mechanisms.

- Development of perioperative protocols tailored to COVID-19 patients, emphasizing preoperative optimization and postoperative care.

- Exploration of long-term outcomes, including quality of life and functional recovery in COVID-19 surgical patients.

Conclusion

Acknowledgement

Conflict of interest

References

- Brown, W.A.; Moore, E.M.; Watters, D.A. Mortality of patients with COVID-19 who undergo an elective or emergency surgical procedure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vol. 91, ANZ Journal of Surgery. Blackwell Publishing; 2021. p. 33–41.

- Lescure, F.-X.; Bouadma, L.; Nguyen, D.; et al. Clinical and virological data of the first cases of COVID-19 in Europe: a case series. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machhi, J.; Herskovitz, J.; Senan, A.M.; et al. The natural history, pathobiology, and clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infections. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2020, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020. [Cited 21 Aug 2020.]. Available from URL: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid19—11-march-2020.

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Cardona-Ospina, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Ocampo, E.; et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 34, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stawicki, S.P.; Jeanmonod, R.; Miller, A.C.; et al. The 2019–2020 novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) pandemic: a Joint American College of Academic International MedicineWorld Academic Council of Emergency Medicine Multidisciplinary COVID-19 Working Group consensus paper, J. Glob. Infect. 2020, 12, 47–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate, S.M.; Mantefardo, B.; Basu, B. Postoperative mortality among surgical patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vol. 14, Patient Safety in Surgery. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2020.

- COVIDSurg Collaborative. Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet 2020, 396, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doglietto, F.; Vezzoli, M.; Gheza, F.; et al. Factors associated with surgical mortality and complications among patients with and without coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- María, F.M.; Lorena, M.R.; María Luz, F.V.; Cristina, R.V.; Dolores, P.D.; Fernando, T.F. Overall management of emergency general surgery patients during the surge of the COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of procedures and outcomes from a teaching hospital at the worst hit area in Spain. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery. 2021, 47, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, A.F.; Lourenço, S.F.; Teixeira R da, S.; Barros, F.; Costa, A.; Lemos, P. Urgent/emergency surgery during COVID-19 state of emergency in Portugal: a retrospective and observational study. Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology (English Edition). 2021, 71, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, S.; MacArthur, T.; Fischmann, M.M.; Maroun, J.; Dang, J.; Markos, J.R.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Governmental Restrictions on Emergency General Surgery Operative Volume and Severity. American Surgeon. 2023, 89, 1457–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, M.J.; Harmston, C. The effect of national public health interventions for COVID-19 on emergency general surgery in Northland, New Zealand. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2021, 91, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative. Mortality and pulmonary complications in emergency general surgery patients with COVID-19: A large international multicenter study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022, 93, 59–65, Epub 2022 Feb 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chan, A.; Stathakis, P.; Goldsmith, P.; Smith, S.; Macutkiewicz, C. The reorganisation of emergency general surgery services during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: outcomes of delayed presentation, socio-economic deprivation and Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic patients. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2023, 105, S46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarim, I.A.; Derebey, M.; Özbalci, G.S.; Özşay, O.; Yüksek, M.A.; Büyükakıncak, S.; et al. The impact of the covid-19 pandemic on emergency general surgery: A retrospective study. Sao Paulo Medical Journal. 2021, 139, 53–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willms, A.G.; Oldhafer, K.J.; Conze, S.; Thasler, W.E.; von Schassen, C.; Hauer, T.; Huber, T.; Germer, C.T.; Günster, S.; Bulian, D.R.; Hirche, Z.; Filser, J.; Stavrou, G.A.; Reichert, M.; Malkomes, P.; Seyfried, S.; Ludwig, T.; Hillebrecht, H.C.; Pantelis, D.; Brunner, S.; Rost, W.; Lock, J.F.; CAMIN Study Group. Appendicitis during the COVID-19 lockdown: results of a multicenter analysis in Germany. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021, 406, 367–375, Epub 2021 Feb 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fallani, G.; Lombardi, R.; Masetti, M.; Chisari, M.; Zanini, N.; Cattaneo, G.M.; et al. Urgent and emergency surgery for secondary peritonitis during the COVID-19 outbreak: an unseen burden of a healthcare crisis. Updates in Surgery. 2021, 73, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Caballero, J.; González González, L.; Rodríguez Cuéllar, E.; Ferrero Herrero, E.; Pérez Algar, C.; Vaello Jodra, V.; et al. Multicentre cohort study of acute cholecystitis management during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery. 2021, 47, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarleglio, F.A.; Rigoni, M.; Mereu, L.; Tommaso, C.; Carrara, A.; Malossini, G.; et al. The negative effects of COVID-19 and national lockdown on emergency surgery morbidity due to delayed access. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzati, A.; Rousseau, M.R.; Bartier, S.; Dabi, Y.; Challine, A.; Haddad, B.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on surgical emergencies: Nationwide analysis. BJS Open. 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, C.; Kaman, L.; Shah, A.; Thakur, U.K.; Ramavath, K.; Jaideep, B.; et al. Surgical outcome of COVID-19 infected patients: experience in a tertiary care hospital in India. International Surgery Journal. 2021, 8, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratha, A.R.; Pustela, M.K.; Kaniti, V.K.; Shaik, S.B.; Pecheti, T. Retrospective analysis of outcome of COVID positive patients undergoing emergency surgeries for acute general surgical conditions. International Surgery Journal. 2023, 10, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, F.M.; Amzallag, É.; Lecluyse, V.; Côté, G.; Couture, É.J.; D’Aragon, F.; et al. Postoperative outcomes in surgical COVID-19 patients: a multicenter cohort study. BMC Anesthesiology. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doglietto, F.; Vezzoli, M.; Gheza, F.; Lussardi, G.L.; Domenicucci, M.; Vecchiarelli, L.; et al. Factors Associated with Surgical Mortality and Complications among Patients with and without Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. JAMA Surgery. 2020, 155, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alelyani, R.H.; Alghamdi, A.H.; Mahrous, S.M.; Alamri, B.M.; Alhiniah, M.H.; Abduh, M.S.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown on the Prognosis, Morbidity, and Mortality of Patients Undergoing Elective and Emergency Abdominal Surgery: A Retrospective Cohort Study in a Tertiary Center, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, N.K.; Lake, R.; Englum, B.R.; Turner, D.J.; Siddiqui, T.; Mayorga-Carlin, M.; et al. Increased complications in patients who test COVID-19 positive after elective surgery and implications for pre and postoperative screening. American Journal of Surgery. 2022, 223, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloyan, K.; Harutyunyan, H.; Voskanyan, A. Virology: Current Research Early and Late Complications after Abdominal Surgery in Patients with COVID-19 in Armenia. Virol Curr Res. 2021, 5. [Google Scholar]

- de Luca, M.; Sartori, A.; Vitiello, A.; Piatto, G.; Noaro, G.; Olmi, S.; et al. Complications and mortality in a cohort of patients undergoing emergency and elective surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an Italian multicenter study. Teachings of Phase 1 to be brought in Phase 2 pandemic. Updates in Surgery. 2021, 73, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascella, M.; Rajnik, M.; Cuomo, A.; et al. Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19). Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2020. [Cited 22 September 2020.]. Available from URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554776/.

- Yuki, K.; Fujiogi, M.; Koutsogia nnaki, S. COVID-19 pathophysiology: a review. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 215, 108427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbalai Saleh, S.; Oraii, A.; Soleimani, A.; et al. The association between cardiac injury and outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2020, 15, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, K.; Salunke, A.; Pathak, S.K.; Pandey, A.; Doctor, C.; Puj, K.; et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the impact of various comorbidities on serious events. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews. 2020, 14, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Li, R.; Wang, B. Does comorbidity increase the risk of patients with COVID-19: evidence from meta-analysis. Aging 2020, 12, 6049e57, Epub 2020 Jul 24. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein, N.S.; Venkataramani, R.; Goumas, A.M.; Chapman, N.N.; Deriy, L. COVID-19-related cardiovascular disease and practical considerations for perioperative clinicians. Semin. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2020, 24, 293–303, Epub 2020 Jul 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rieder, M.; Goller, I.; Jeserich, M.; et al. Rate of venous thromboembolism in a prospective all-comers cohort with COVID-19, J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2020, 50, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alazawi, W.; Pirmadjid, N.; Lahiri, R.; Bhattacharya, S. Inflammatory and immune responses to surgery and their clinical impact. Ann. Surg. 2016, 264, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholten, R.; Leijtens, B.; Hannink, G.; Kamphuis, E.T.; Somford, M.P.; van Susante, J.L.C. General anesthesia might be associated with early periprosthetic joint infection: an observational study of 3,909 arthroplasties. Acta Orthop. 2019, 90, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, L.; Costantino, F.; Fiorito, M.; Amodio, S.; Pelosi, P. Respiratory mechanics during general anaesthesia. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenstierna, G.; Edmark, L. Mechanisms of atelectasis in the perioperative period. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2010, 24, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggan, M.; Kavanagh, B.P. Atelectasis in the perioperative patient. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2007, 20, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First Author | Country | Year | Type of Surgery | Comparative/Control Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fernández et al. [11]. | Spain | 2021 | Emergency General Surgery | Present |

| Andreia et al. [12]. | Portugal | 2021 | Urgent/Emergency Surgery | Present |

| Sarah et al. [13]. | USA | 2023 | Emergency General Surgery | Present |

| Matthew et al. [14]. | New Zealand | 2021 | Emergency General Surgery | Present |

| COVIDSurg Collaborative [15] | UK | 2022 | Emergency General Surgery | Present |

| Chan et al. [16]. | UK | 2023 | Emergency General Surgery | Present |

| Ismail et al. [17]. | Turkey | 2021 | Emergency General Surgery | Present |

| Arnulf et al. [18]. | Germany | 2021 | Acute Appendicitis | Present |

| Guido et al. [19]. | Italy | 2021 | Emergency Abdominal Surgery | Present |

| Javier et al. [20]. | Spain | 2021 | Acute Cholecystitis | Present |

| First Author | Total patients Covid vs. Non-covid |

Patients’ Age (year) Covid vs. Non-covid |

Gender M:F Covid vs. Non-covid |

Mortality Rates Covid vs. Non-covid |

Morbidity Rates Covid vs. Non-covid |

Mechanical Ventilation Covid vs. Non-covid |

ICU Admission Covid vs. Non-covid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fernández et al. | 27, 126 | 57.5 ± 21 (total) | 91:62 (total) | 18.5%, 7% | 85.7%, 26.7% | 66%, 0 | 36%, 14% |

| Andreia et al. | 457, 643 | 67, 63 (Median) | 261:196, 368:275 |

11.40%, 5.9% | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| Sarah et al. | 229, 279 | 59.3, 56.7 (Mean) | 102:127, 121:158 | 5%, 4% | 25%, 29% | Not specified | Not specified |

| Matthew et al. | 627, 650 | 57, 57 (Median) |

327:300, 314:336 | 4%, 3% | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| COVIDSurg Collaborative | 344, 701 | 17-70 (total) | 220:124, 406:295) | 40.1%, 2.9% | 72.7%, 0 | 23.9%, 0 | Not specified |

| Chan et al. | 223, 422 | 48.6, 48.5 (Mean) | 114:109, 191:231 | 5.8%, 2.4% | 5.6%, 4.8% | Not specified | 8.5%, 7.1% |

| Ismail et al. | 132, 195 | 50, 53 (Median) | 74:58, 82:113 | 3%, 3.1% | 7%, 1.5% | Not specified | Not specified |

| Arnulf et al. | 888, 1027 | 36 ± 20, 35 ± 19 (Mean) | 468:420, 510:517 | 0.1%, 0.2% | 14.3%, 13.3% | Not specified | 4.5%, 3.9% |

| Guido et al. | 149, 183 | 49 (26.5-70), 44 [24–61] | 94:55, 97:86 | 6%, 4.9% | 35.6%, 18% | Not specified | Not specified |

| Javier et al. | 257, 215 | 69 (52-80), 68 (50-80) (Median) | 146:111, 118:97 | 11.9%, 3.2% | 100%, 26% | Not specified | Not specified |

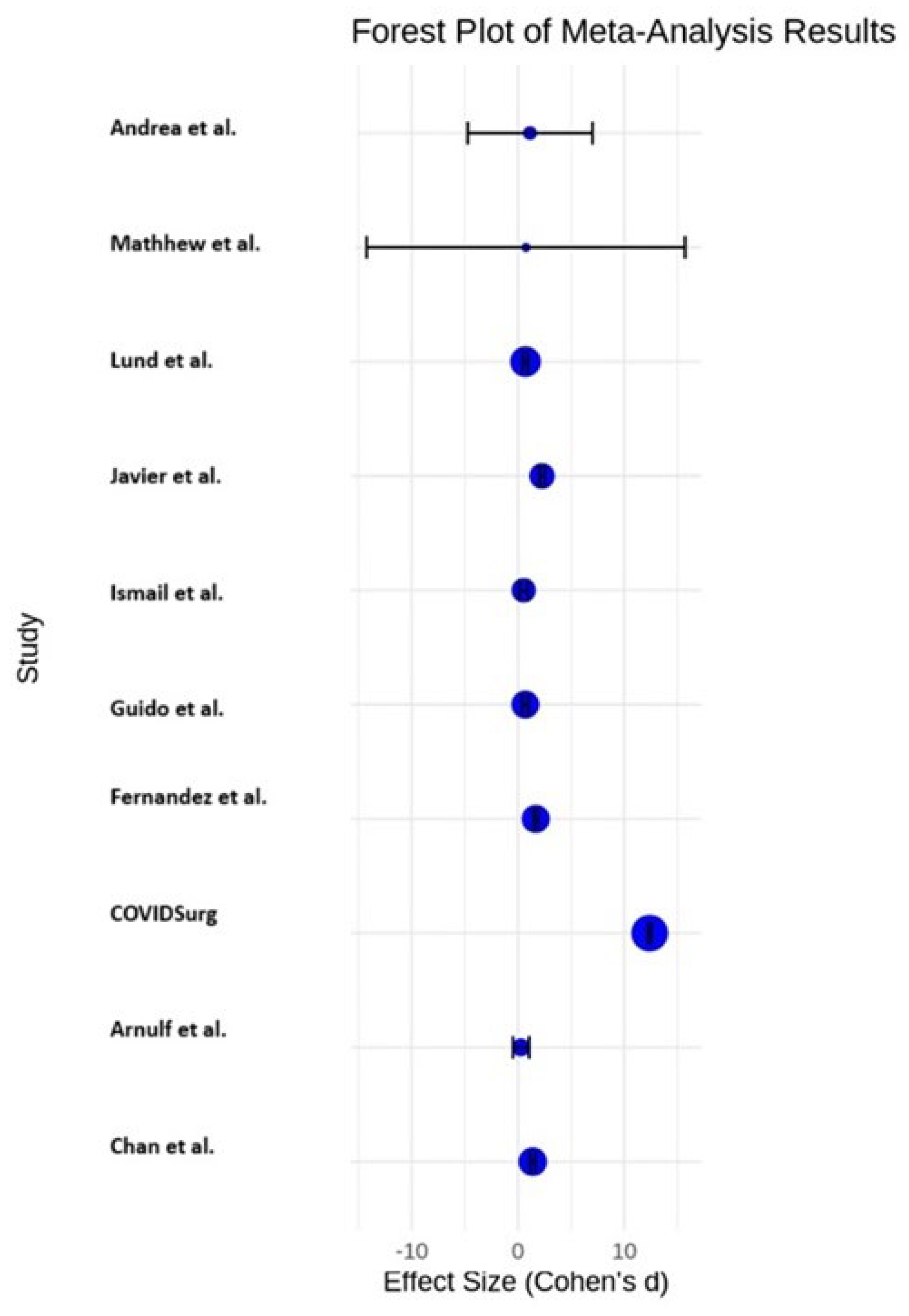

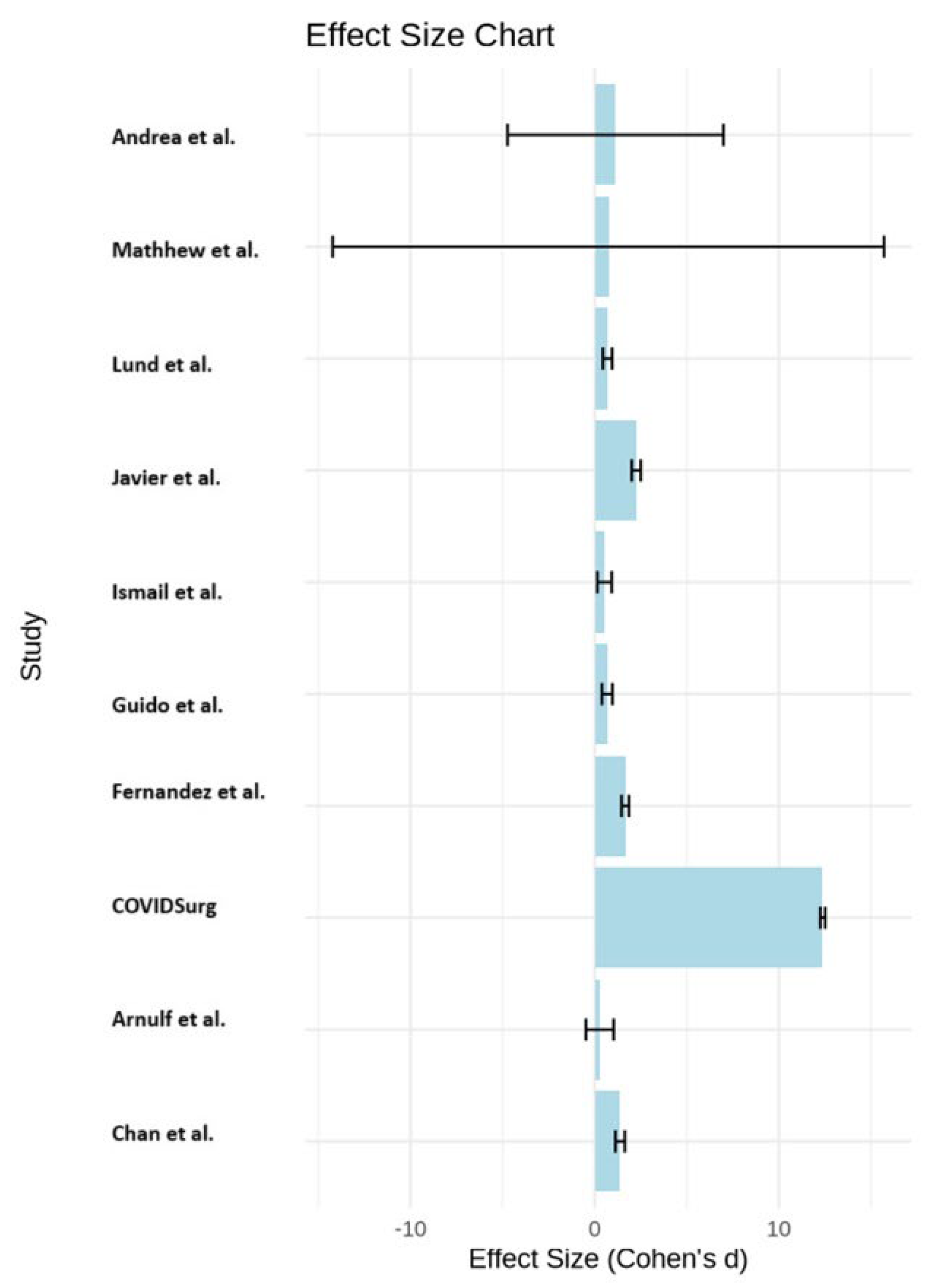

| First Author | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) |

Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% CI | Risk Ratio (RR) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fernández et al. | 1.666187845 | 3.0158 | 0.9191, 9.8958 | 2.6429 | 0.957, 7.2894 |

| Andreia et al. | 1.133756906 | 2.0521 | 1.3258, 3.1763 | 1.9322 | 1.2942, 2.8847 |

| Sarah et al. | 0.697900552 | 1.2632 | 0.5433, 2.9366 | 1.25 | 0.5585, 2.7979 |

| Matthew et al. | 0.744309392 | 1.3472 | 0.7377, 2.4602 | 1.3333 | 0.7454, 2.3849 |

| COVIDSurg Collaborative | 12.3839779 | 22.415 | 13.718, 36.6256 | 13.8276 | 8.8398, 21.6296 |

| Chan et al. | 1.383370166 | 2.5039 | 1.082, 5.7941 | 2.4167 | 1.0792, 5.4119 |

| Ismail et al. | 0.534088398 | 0.9667 | 0.267, 3.5008 | 0.9677 | 0.2779, 3.37 |

| Arnulf et al. | 0.275966851 | 0.4995 | 0.0414, 6.0297 | 0.5 | 0.0416, 6.0162 |

| Guido et al. | 0.68441989 | 1.2388 | 0.4778, 3.2118 | 1.2245 | 0.4975, 3.014 |

| Javier et al. | 2.257458564 | 4.086 | 1.226, 13.6181 | 3.7188 | 1.2336, 11.2104 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).