Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Data Sources

Data Analysis

3. Results

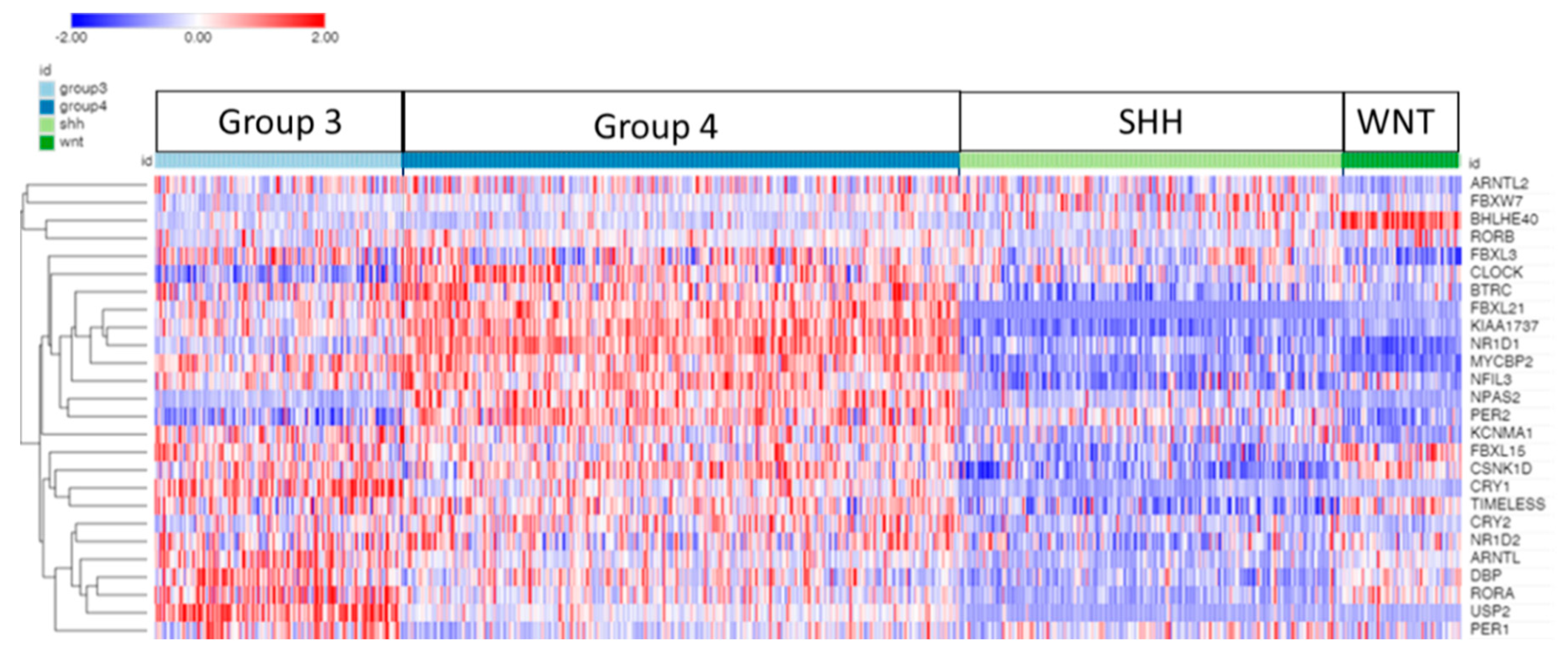

3.1. Clock Gene Expression in Medulloblastoma Subgroups

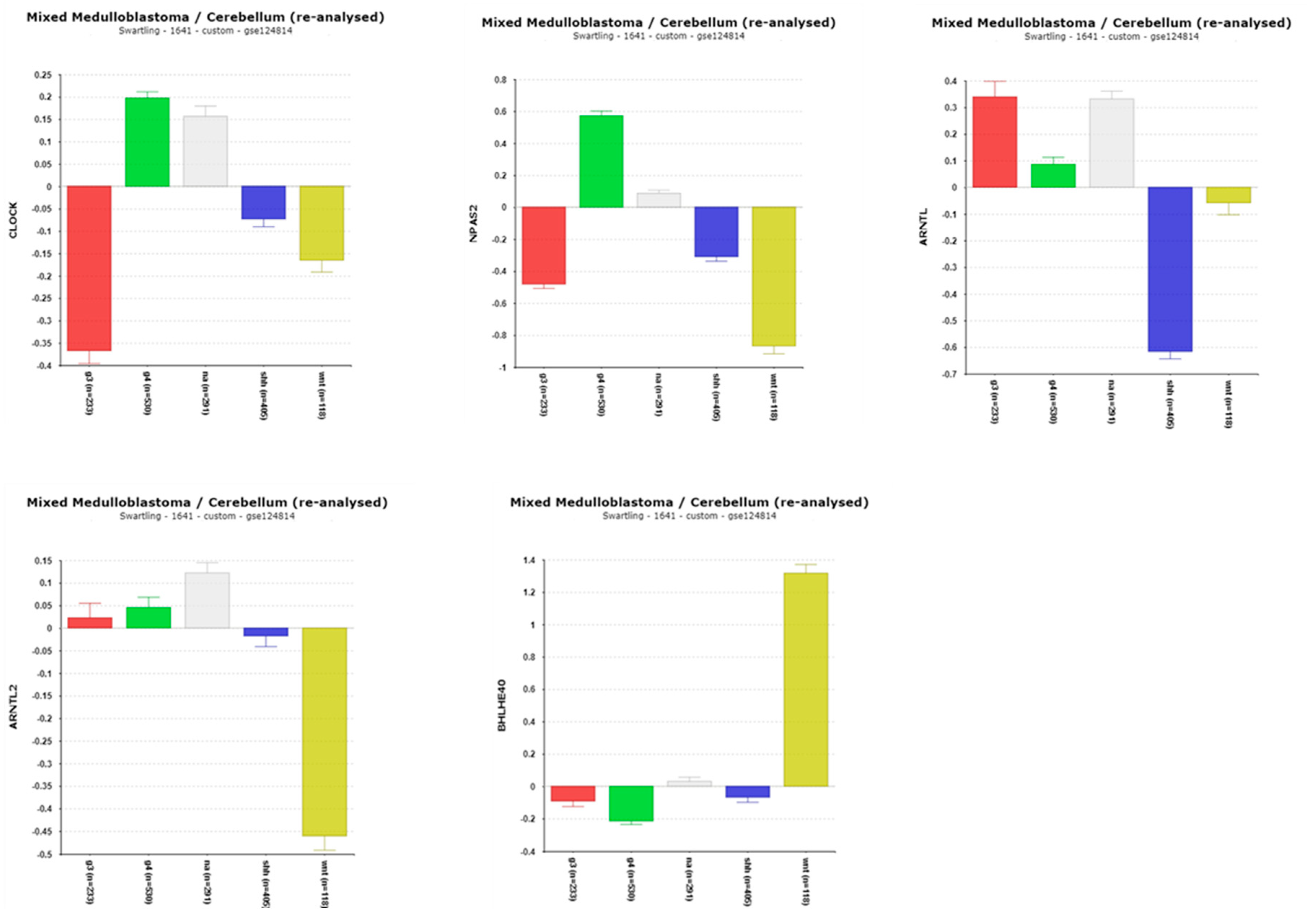

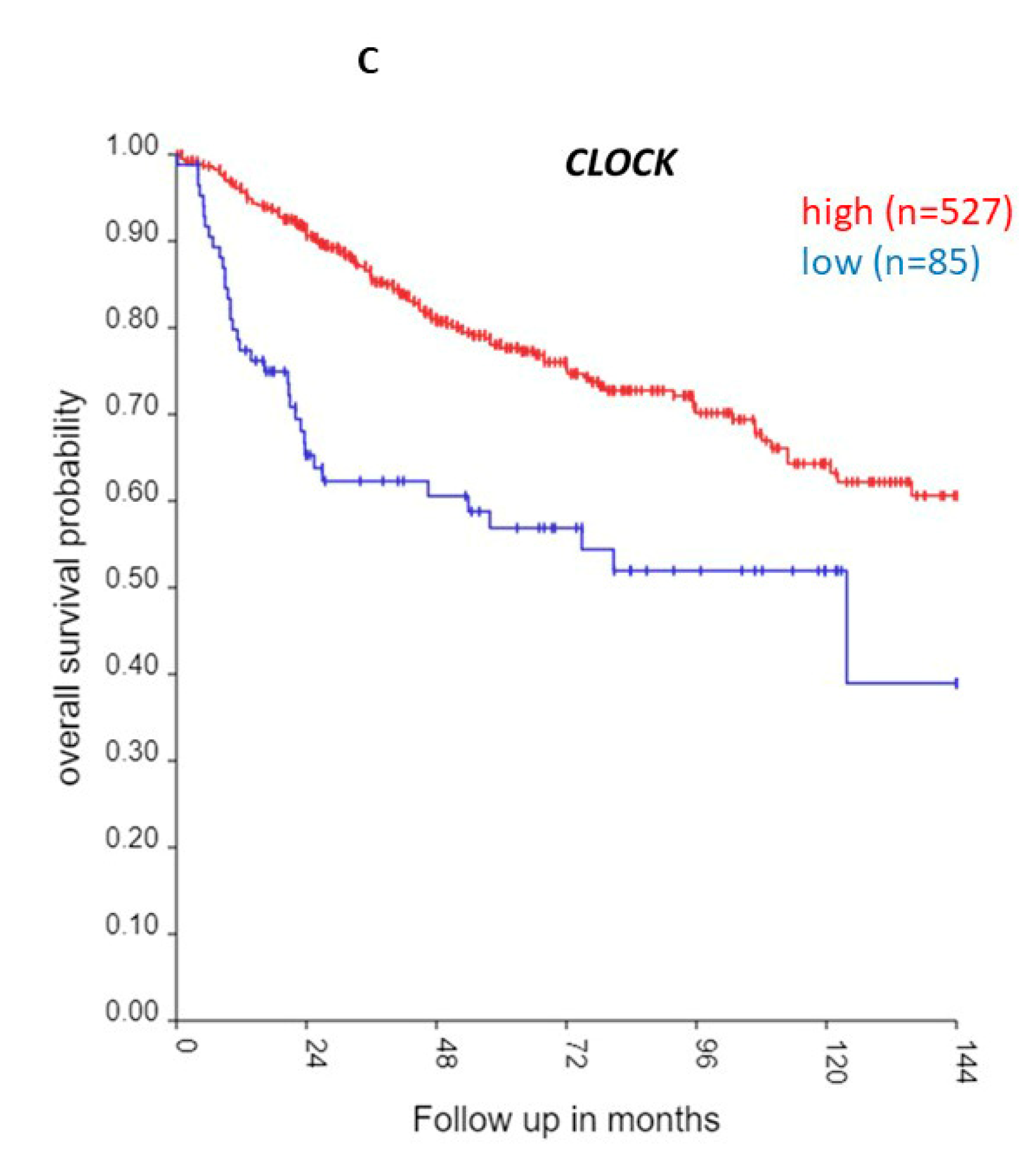

3.1.1. CLOCK and BMAL Expression in MB Subgroups

3.1.2. BHLHE40 and Survival in WNT MBs

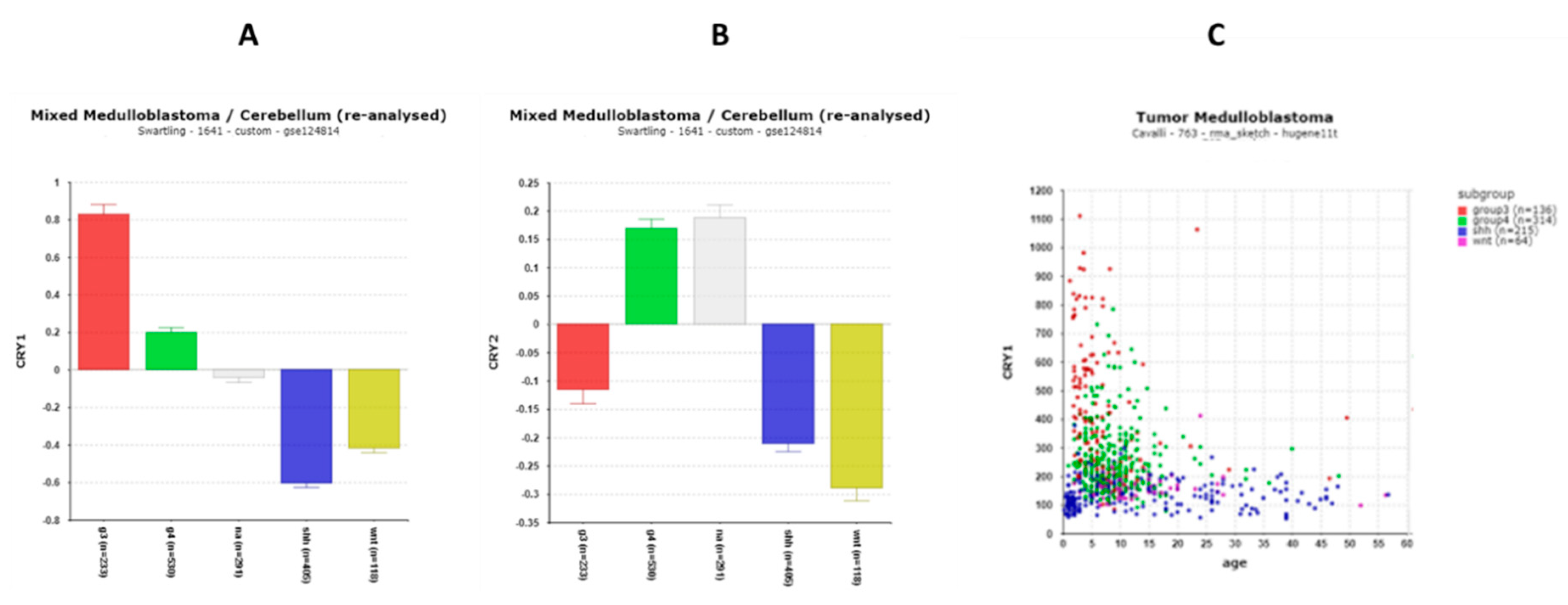

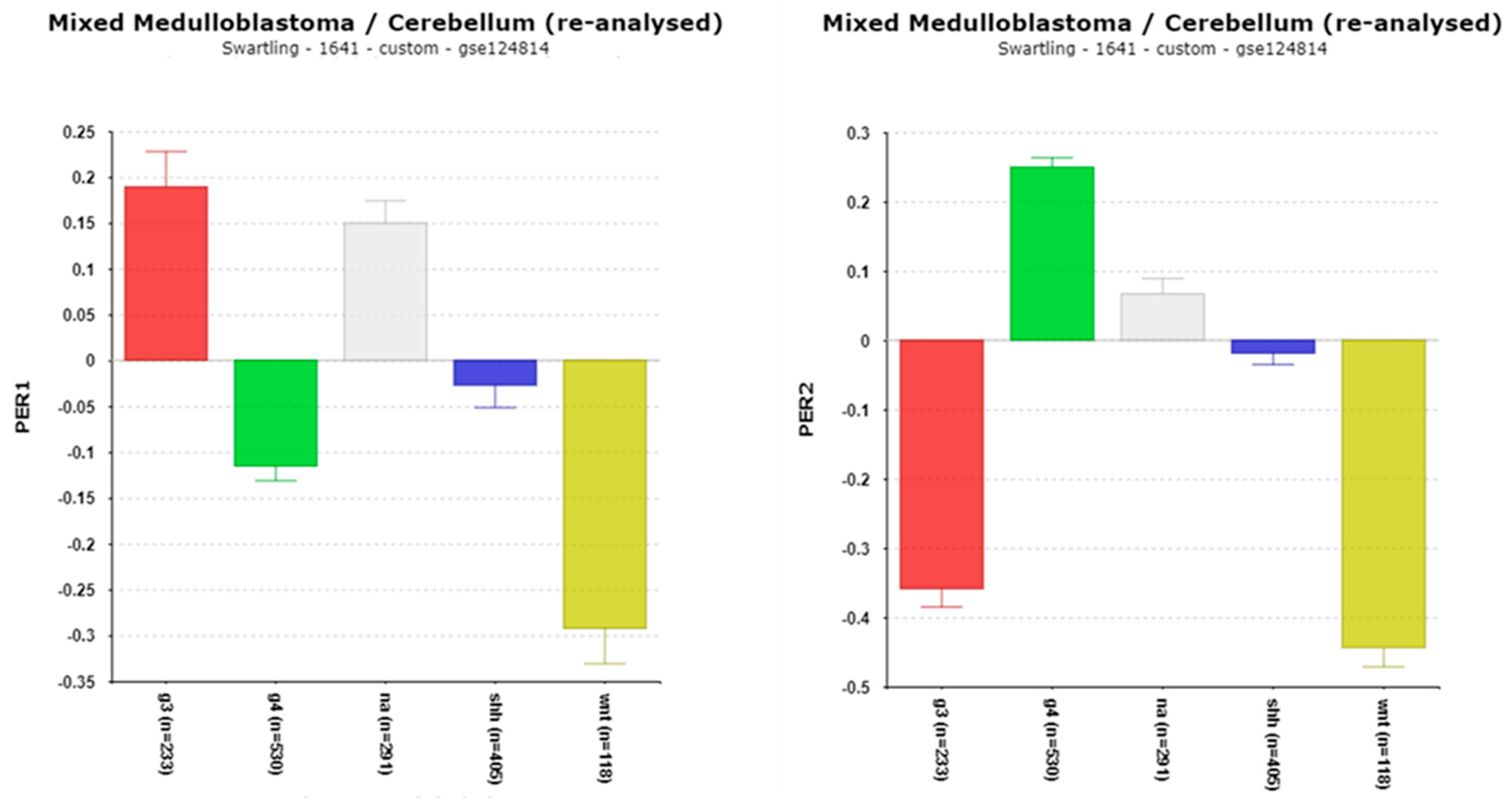

3.1.3. Cryptochrome (CRY) and Period (PER) Gene Expression

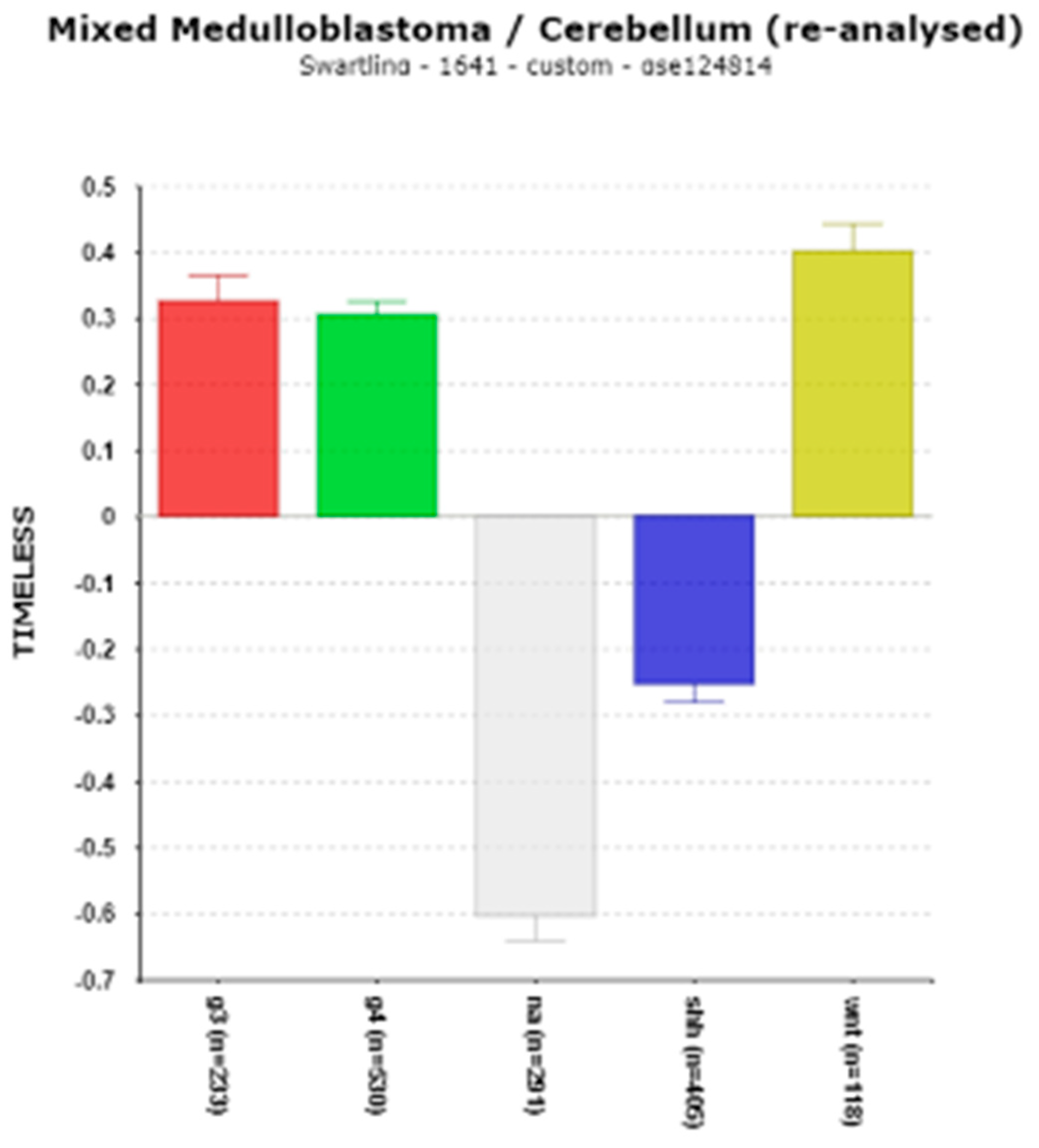

3.1.4. TIMELESS and MB

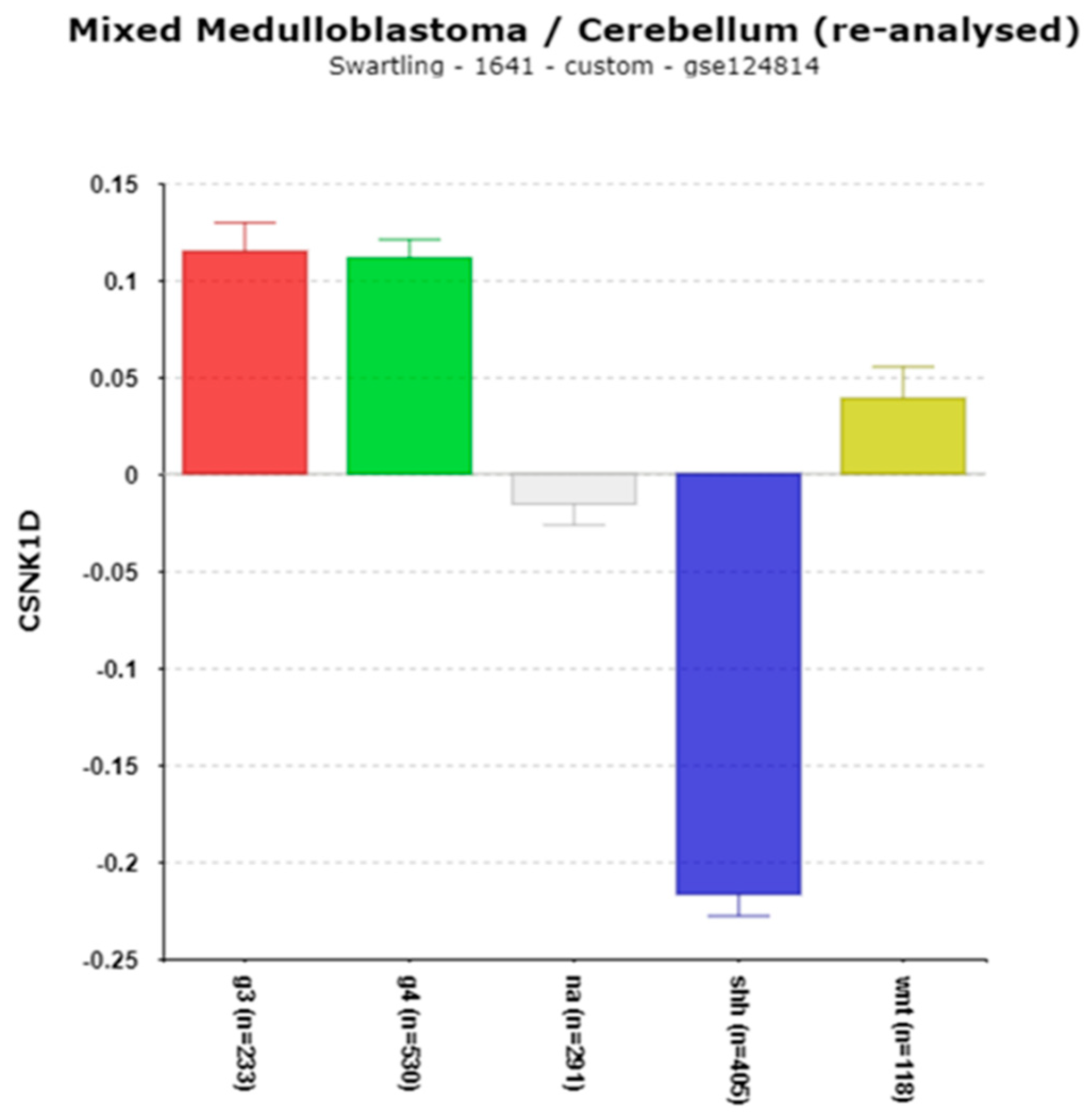

3.1.5. CSNK1D and Chromosome 17q

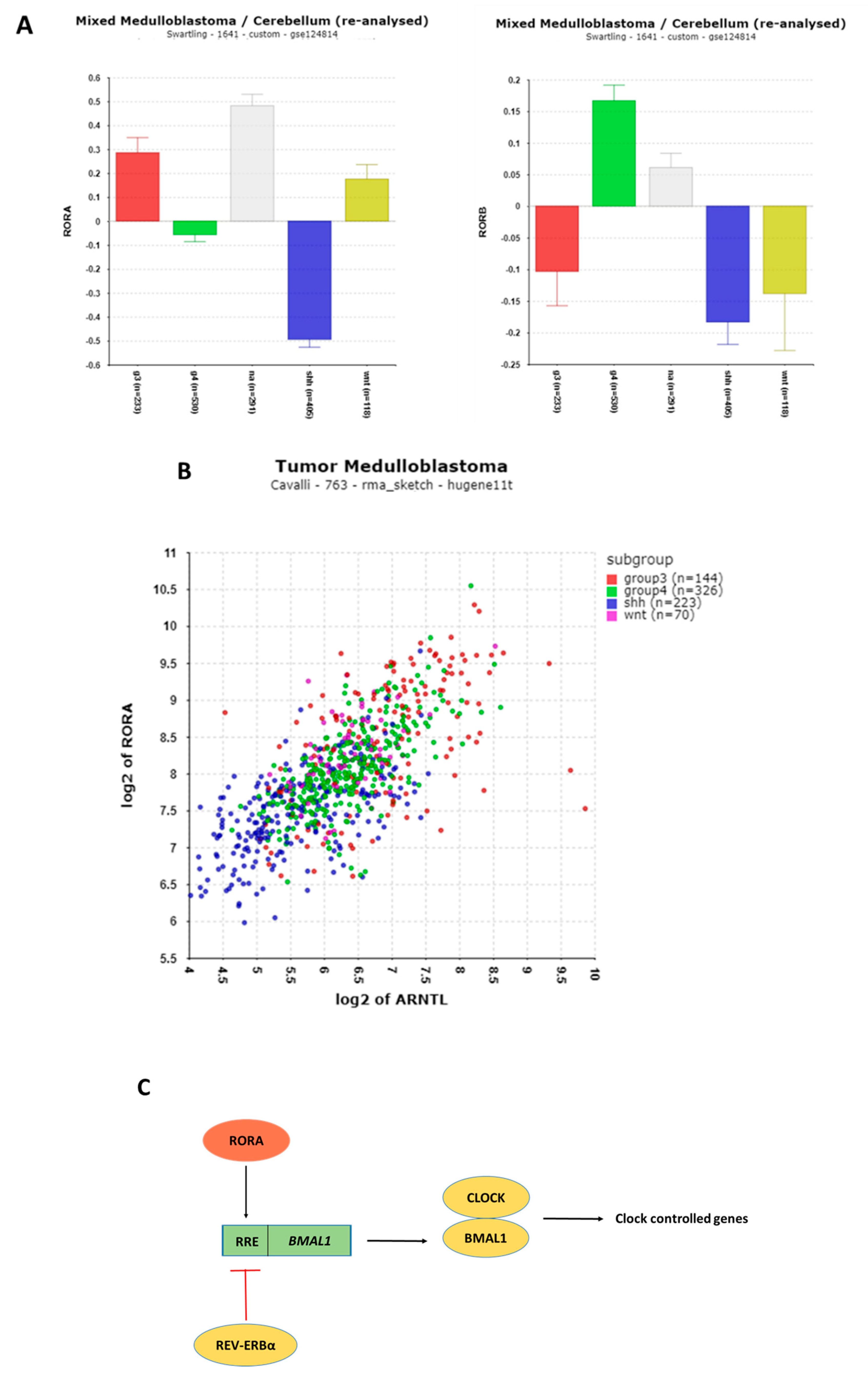

3.1.6. REV-ERB and RORA Expression

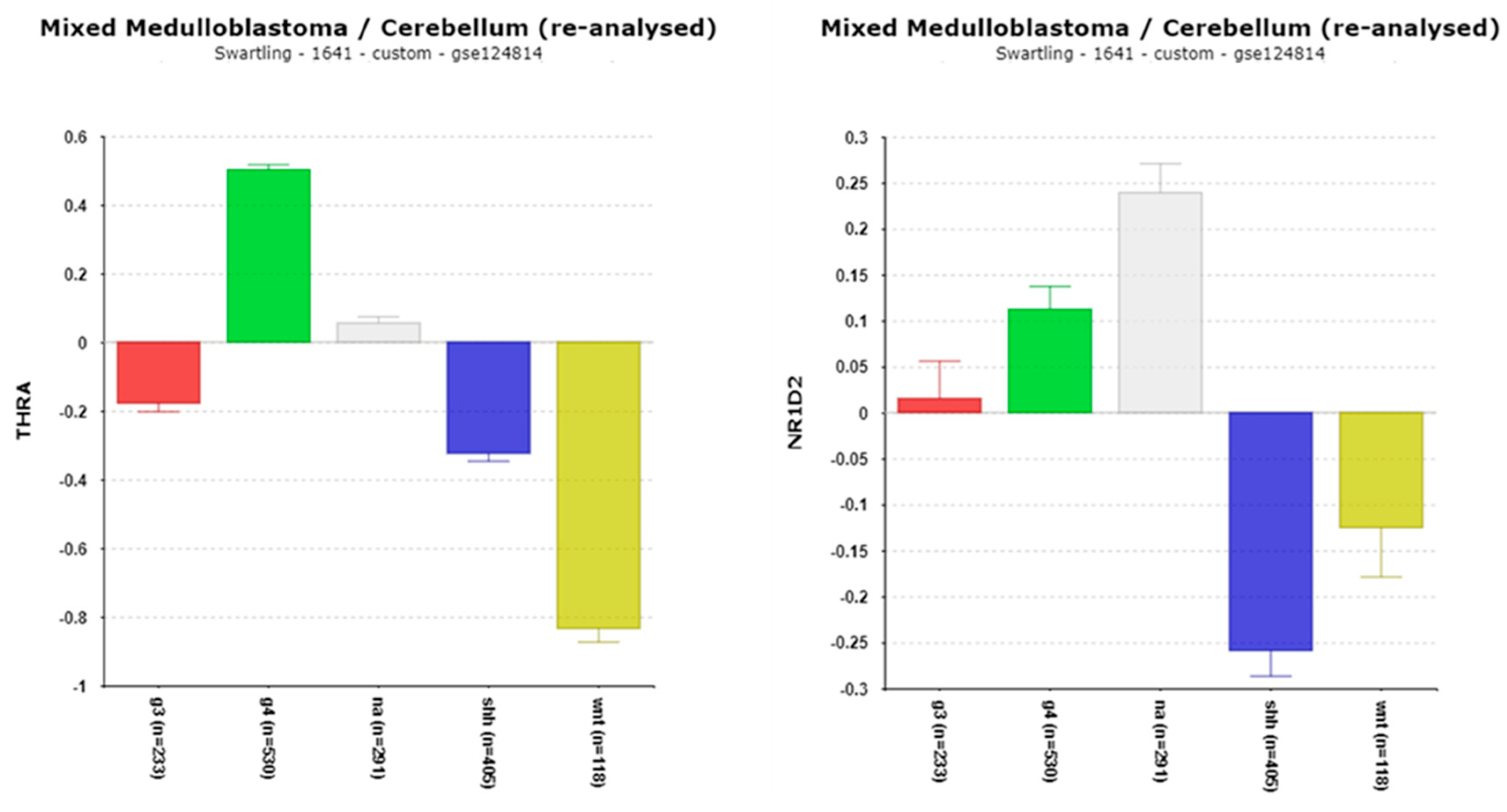

3.1.7. THRA/NR1D1, NR1D2, and Their Implications in Medulloblastoma (MB)

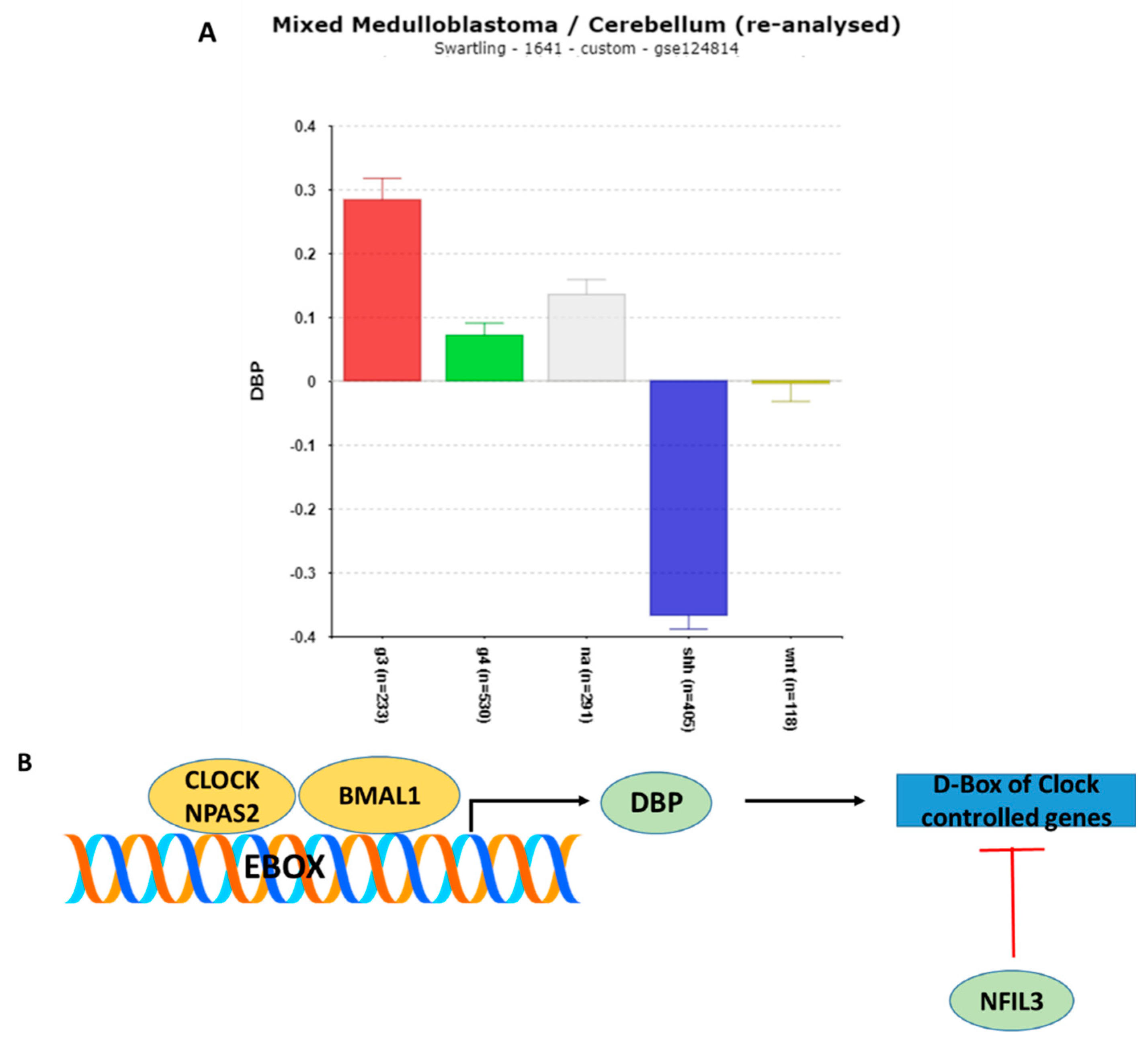

3.1.8. DBP (D-Box of Albumin Promoter) and NFIL3 Gene Expression

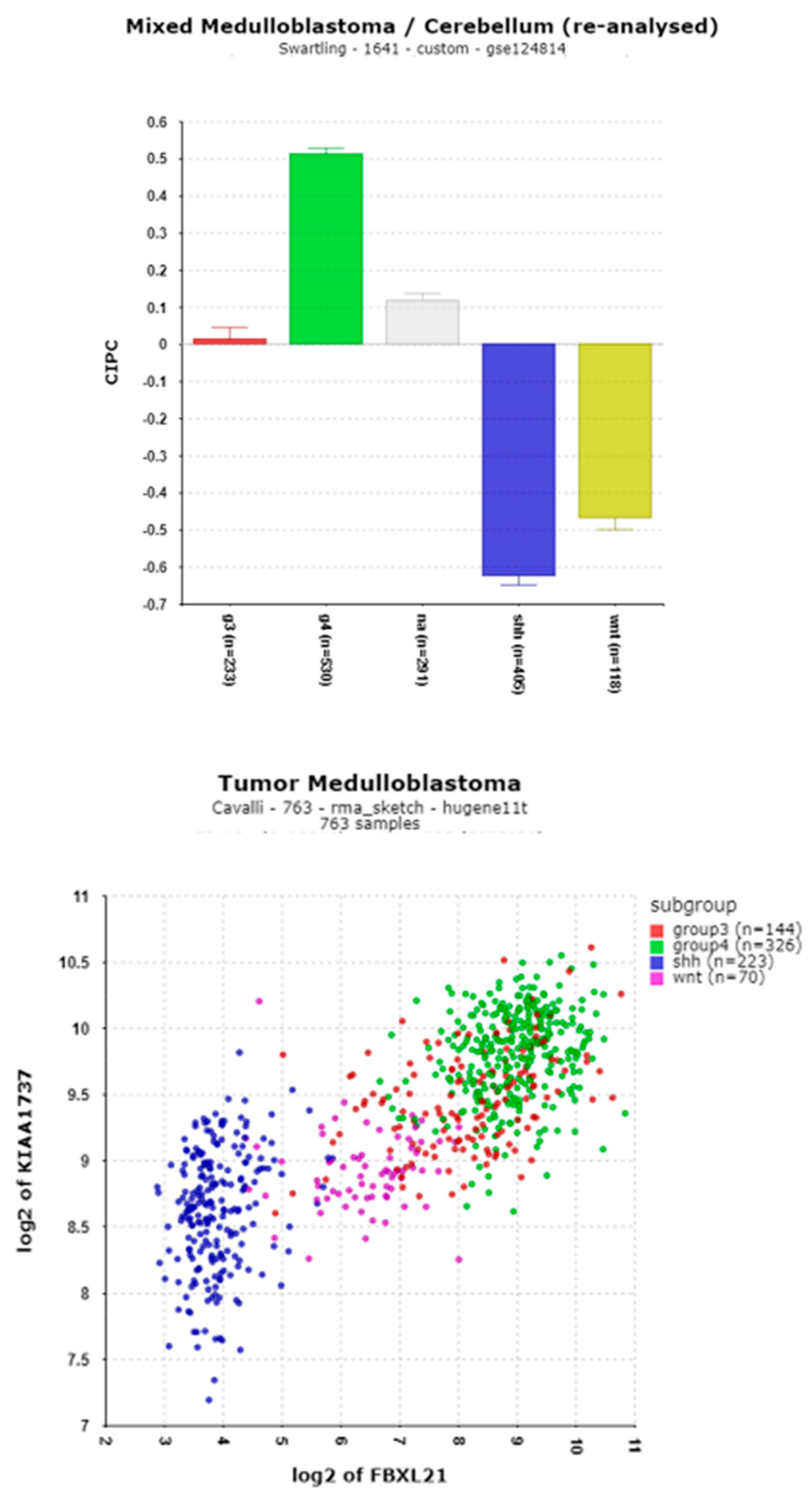

3.1.9. Clock Interacting Pacemaker (CIPC) (aka KIAA1737)

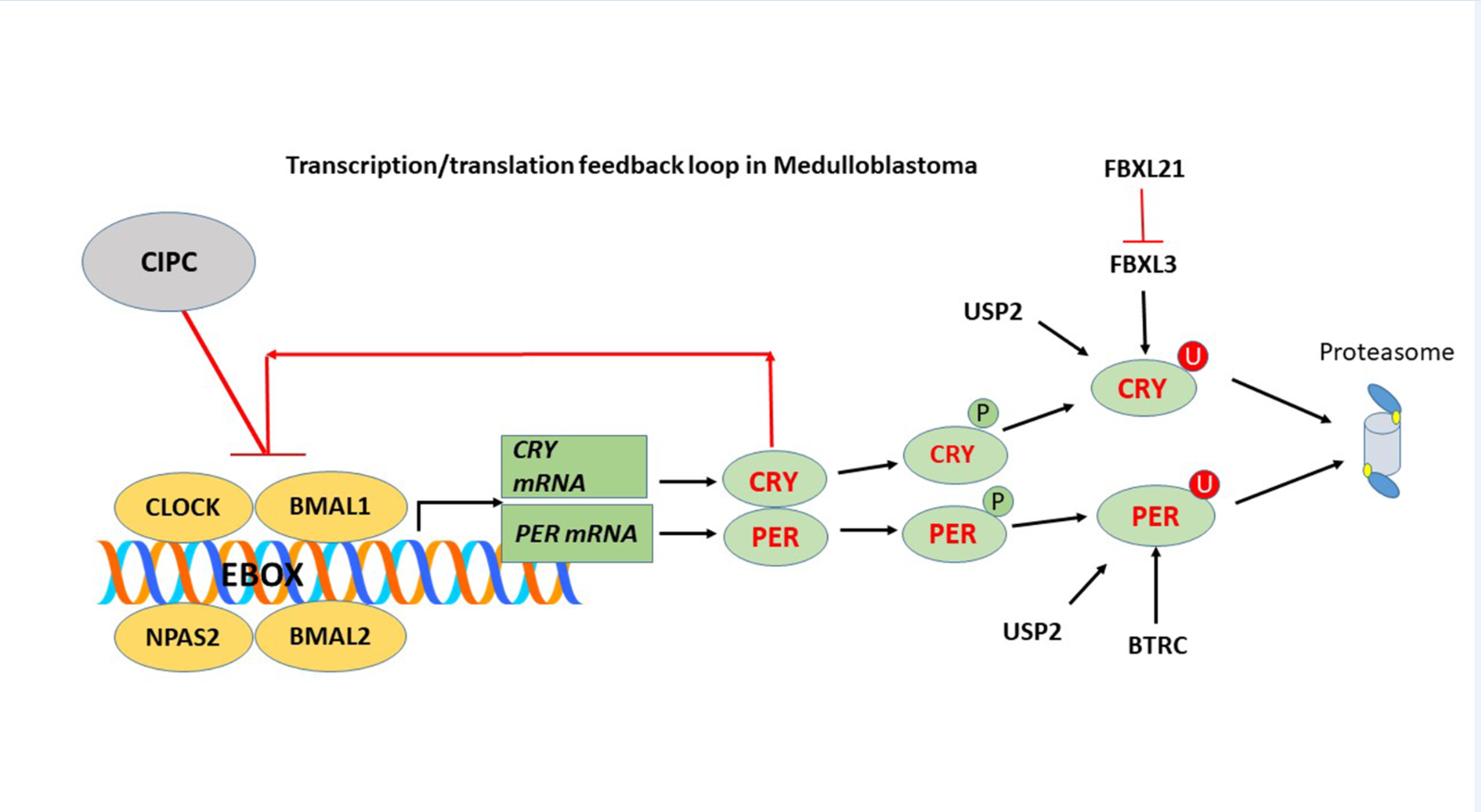

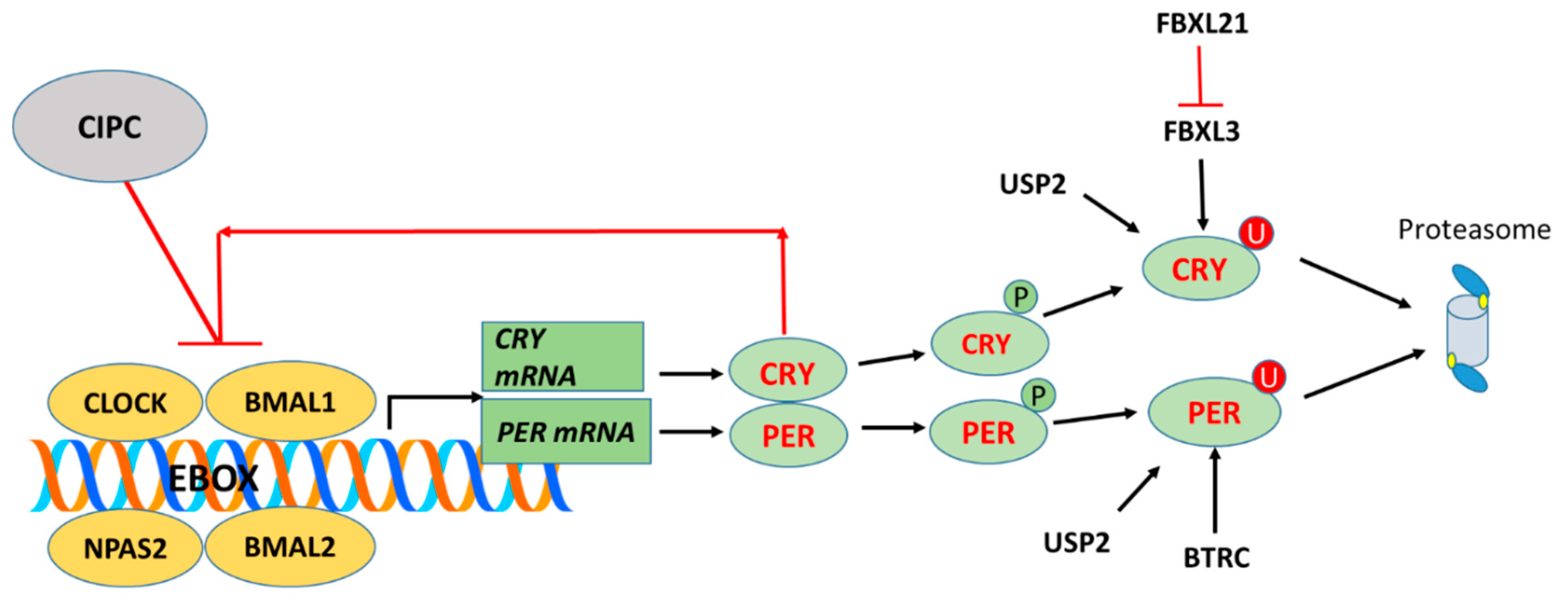

3.2. Ubiquitin Proteasome Pathway Regulation of Clock Genes in MB

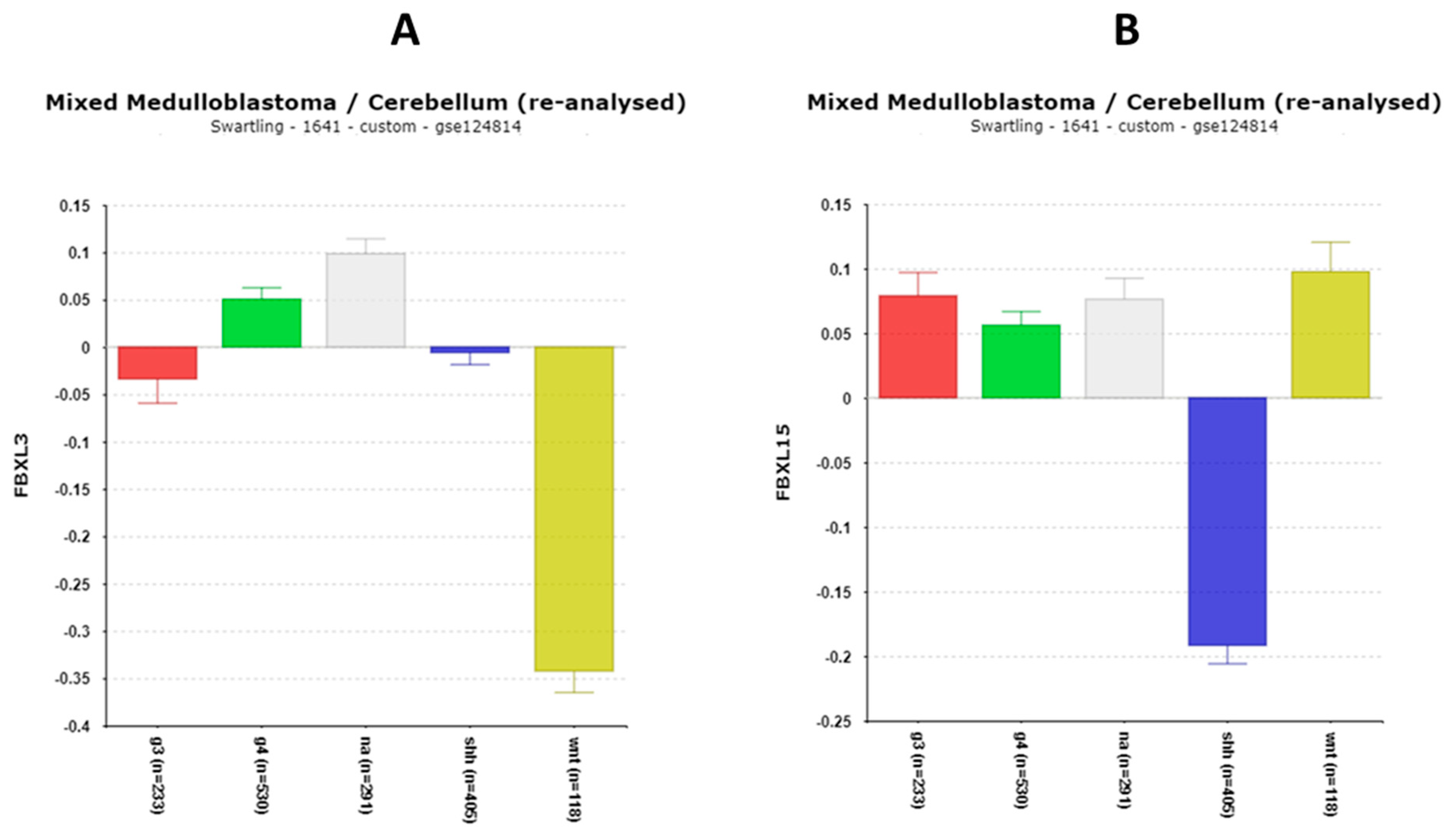

FBXL15

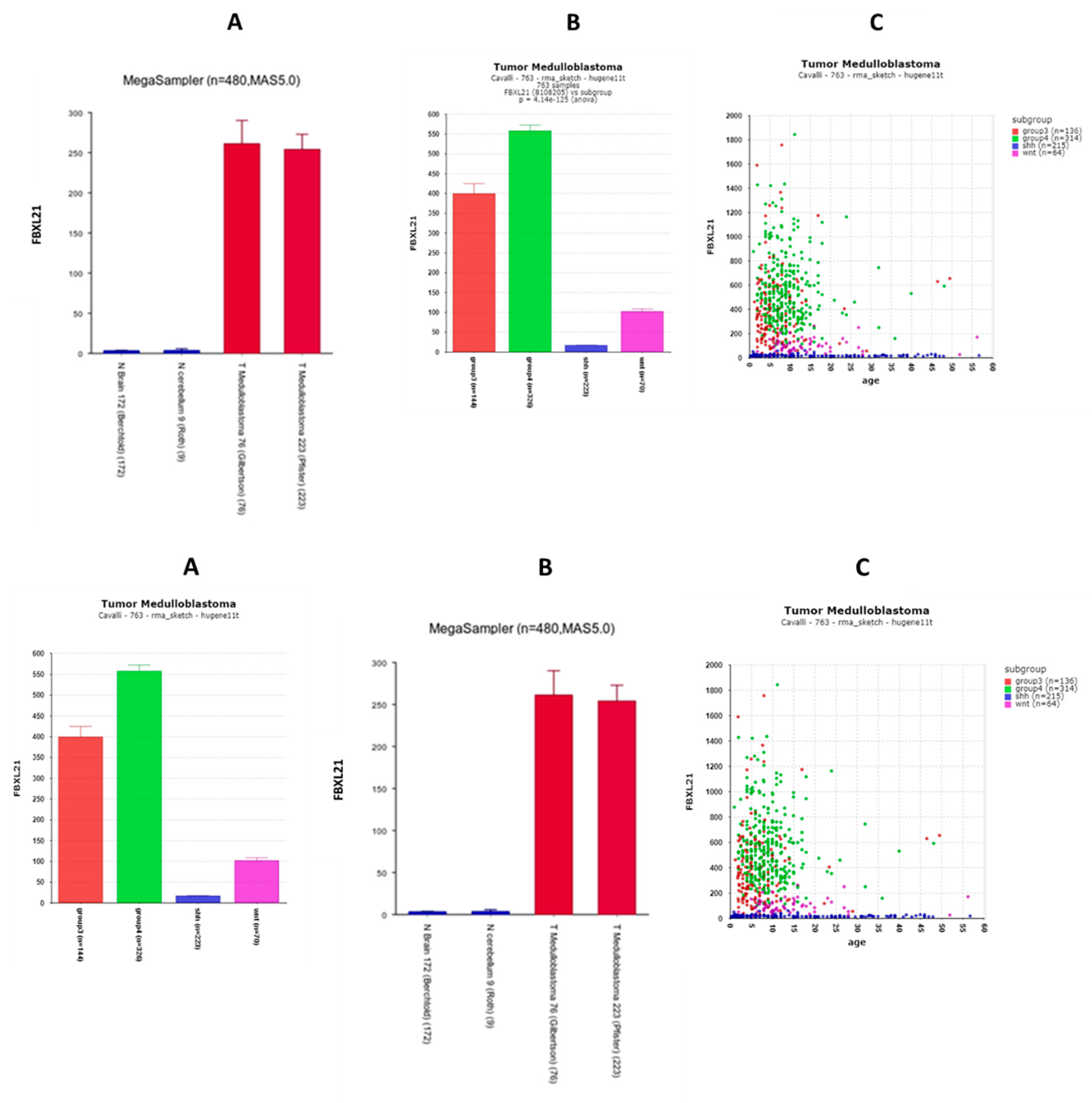

FBXL21

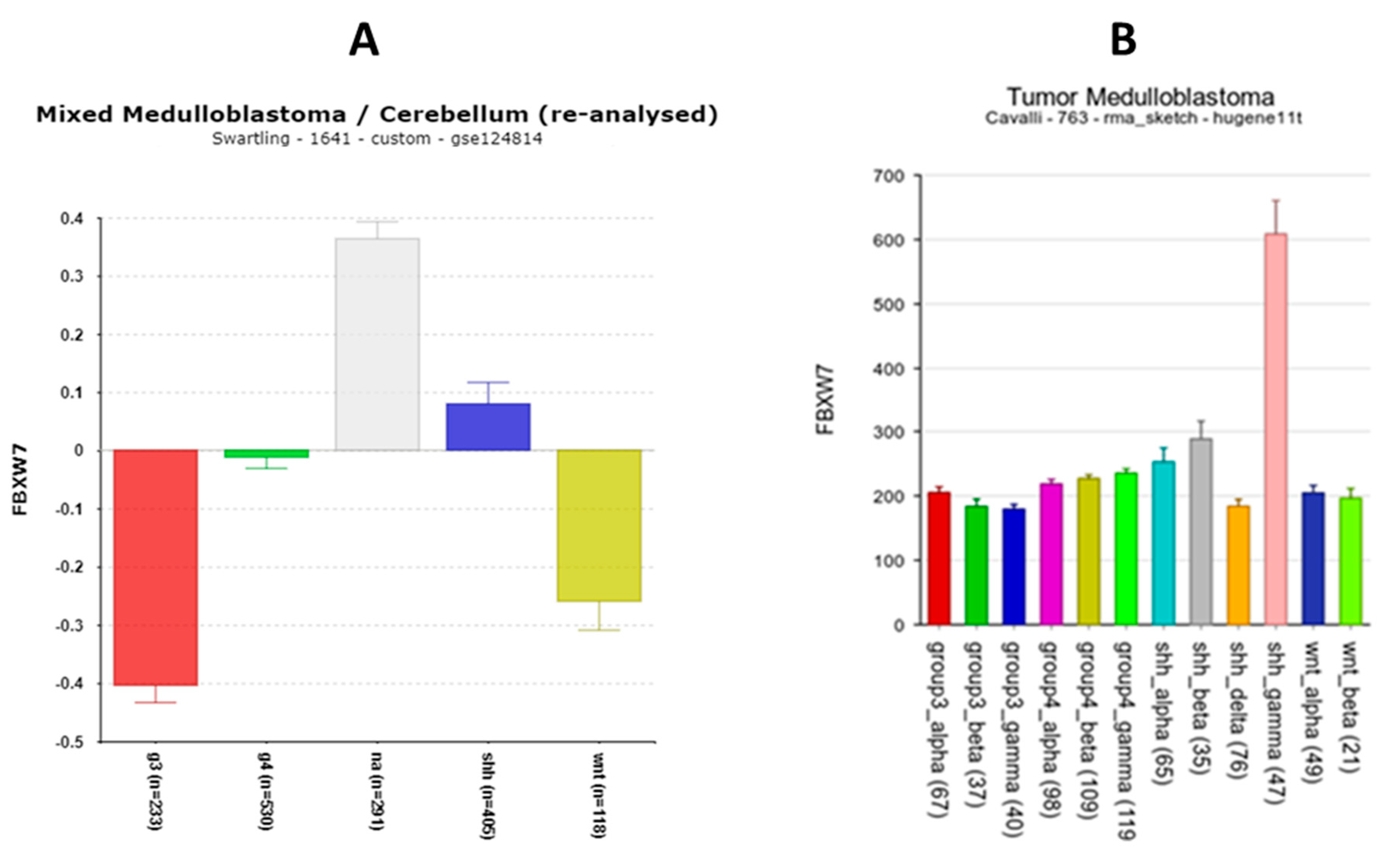

FBXW7

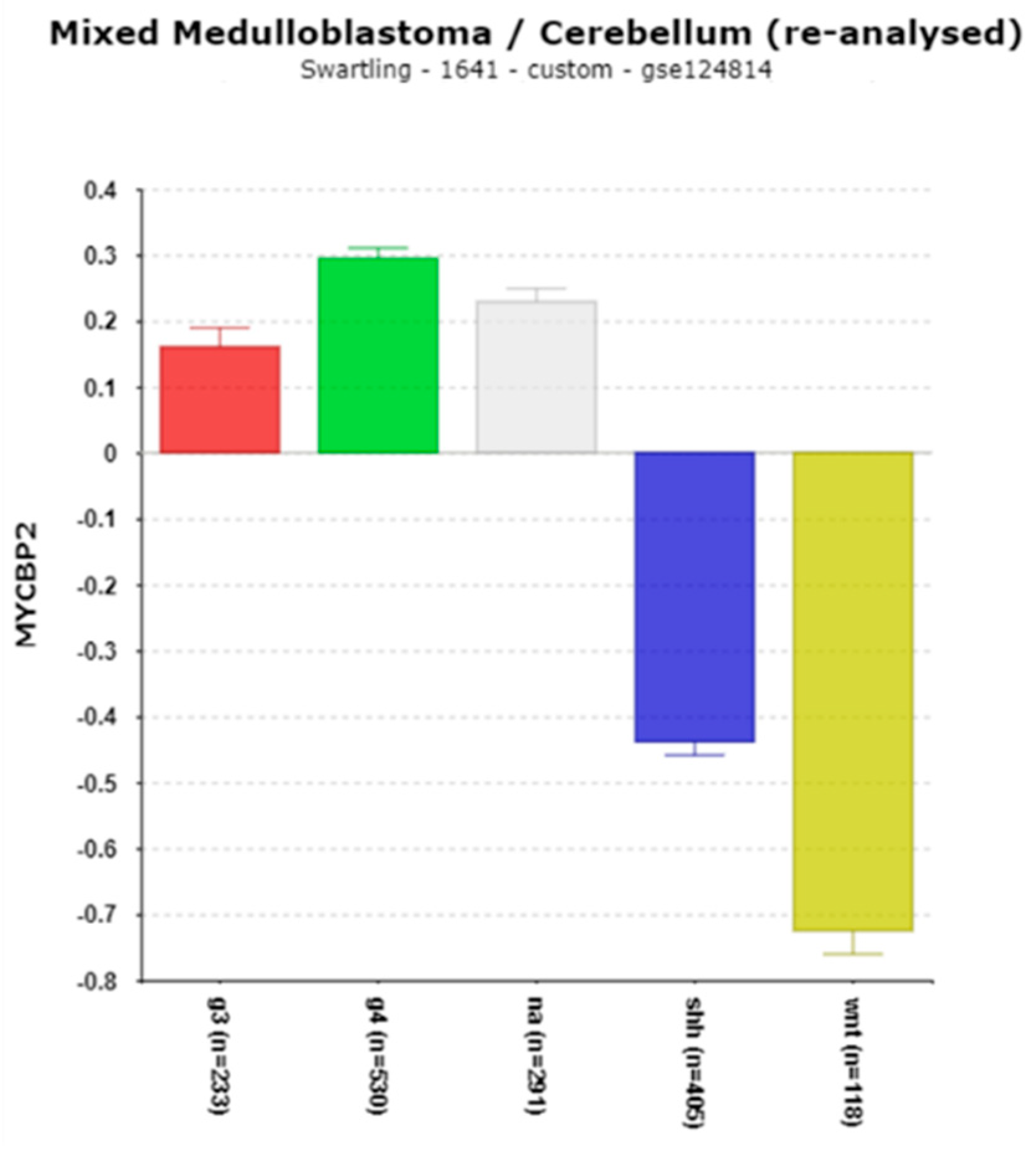

MYCBP2

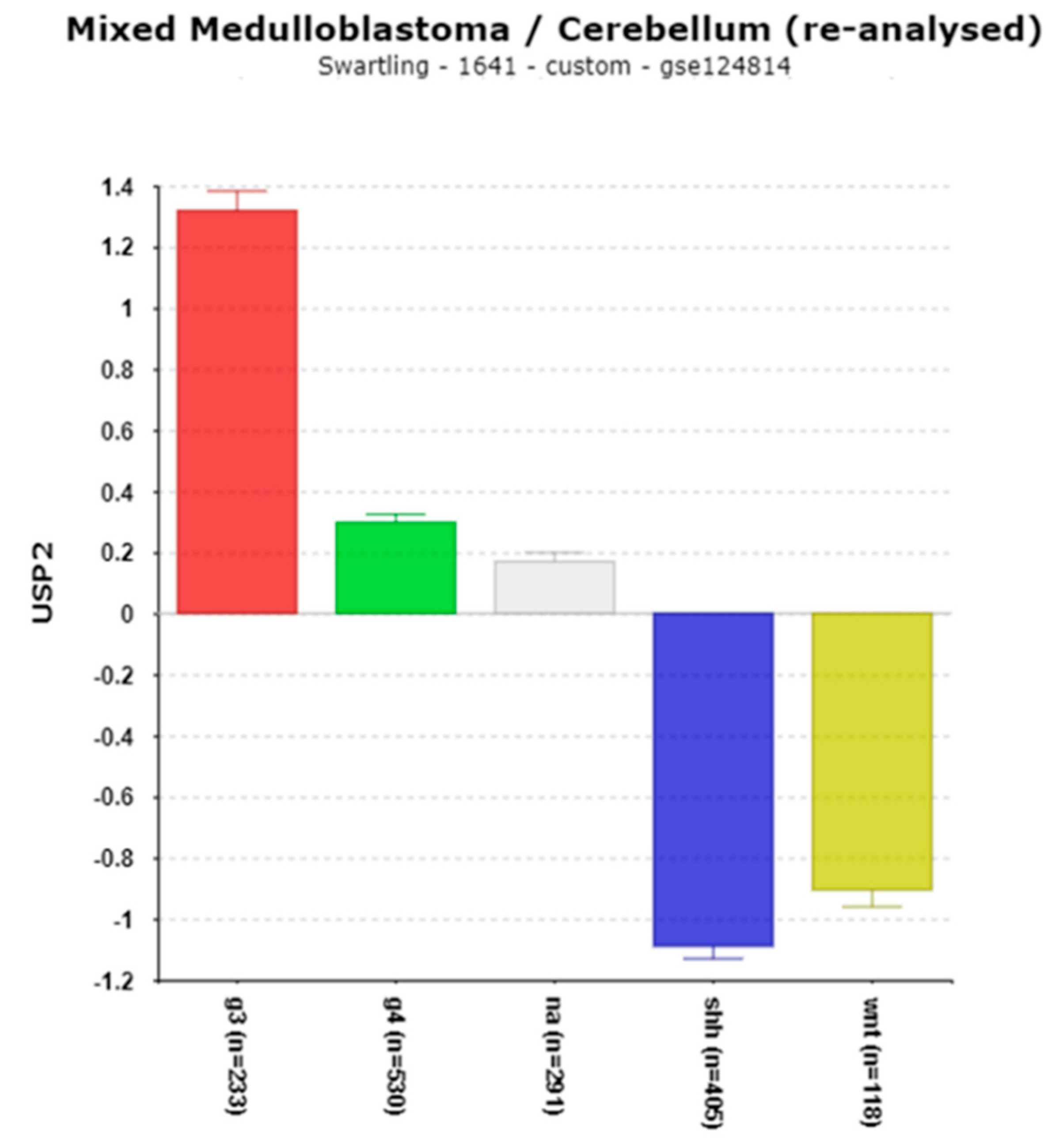

USP2 – A Gene Encoding a Deubiquitinase for Clock Genes

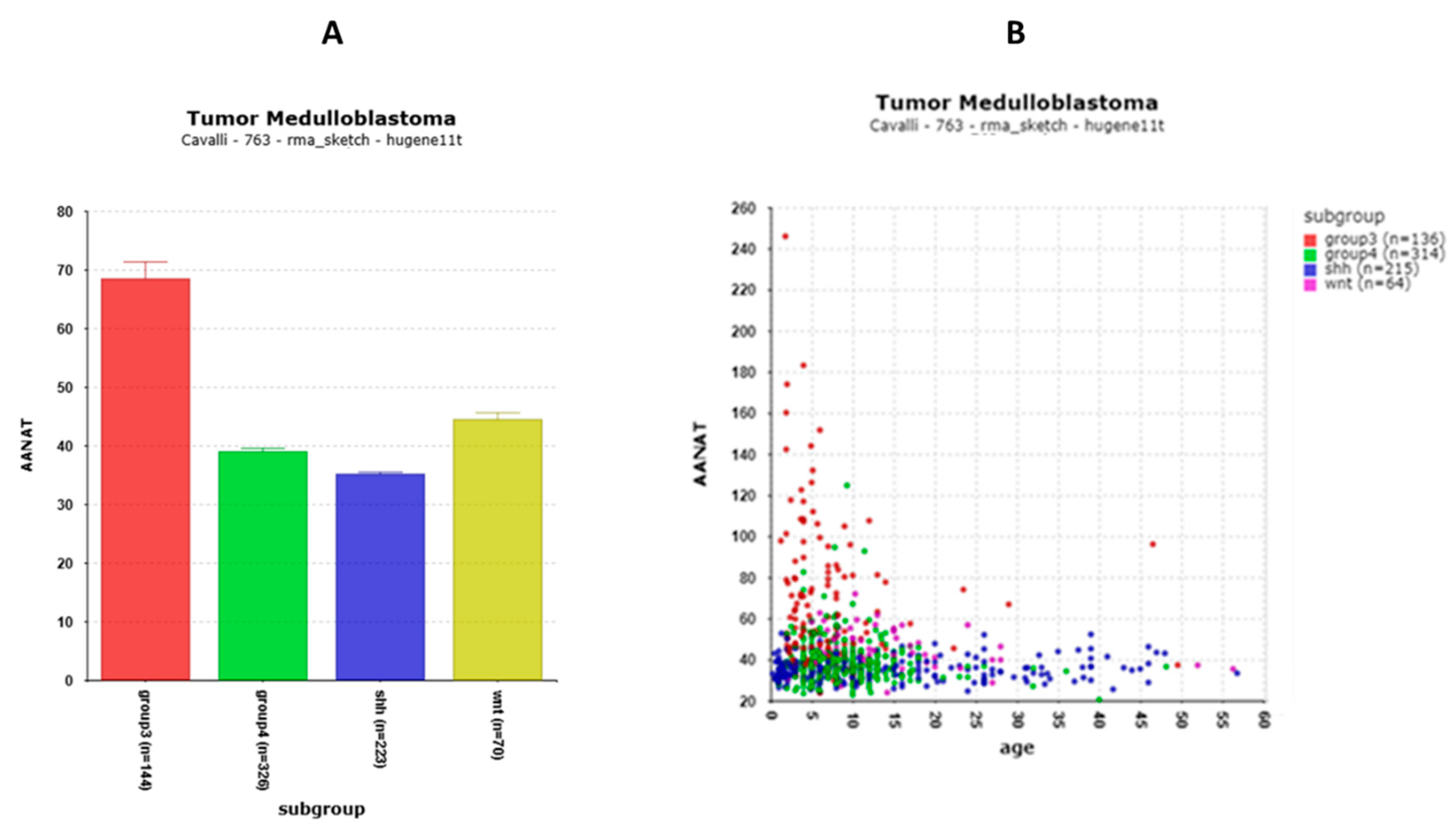

3.3. AANAT Is Over-Expressed in MB Group 3

3.4. Clock Genes and Survival in the Cavalli Dataset

3.5. Clock Genes Correlates: Pathway Analysis in the Cavalli Dataset

3.6. Clock Gene Expression Is Related to Copy Number Gain of Chromosome 17q

4. Discussion

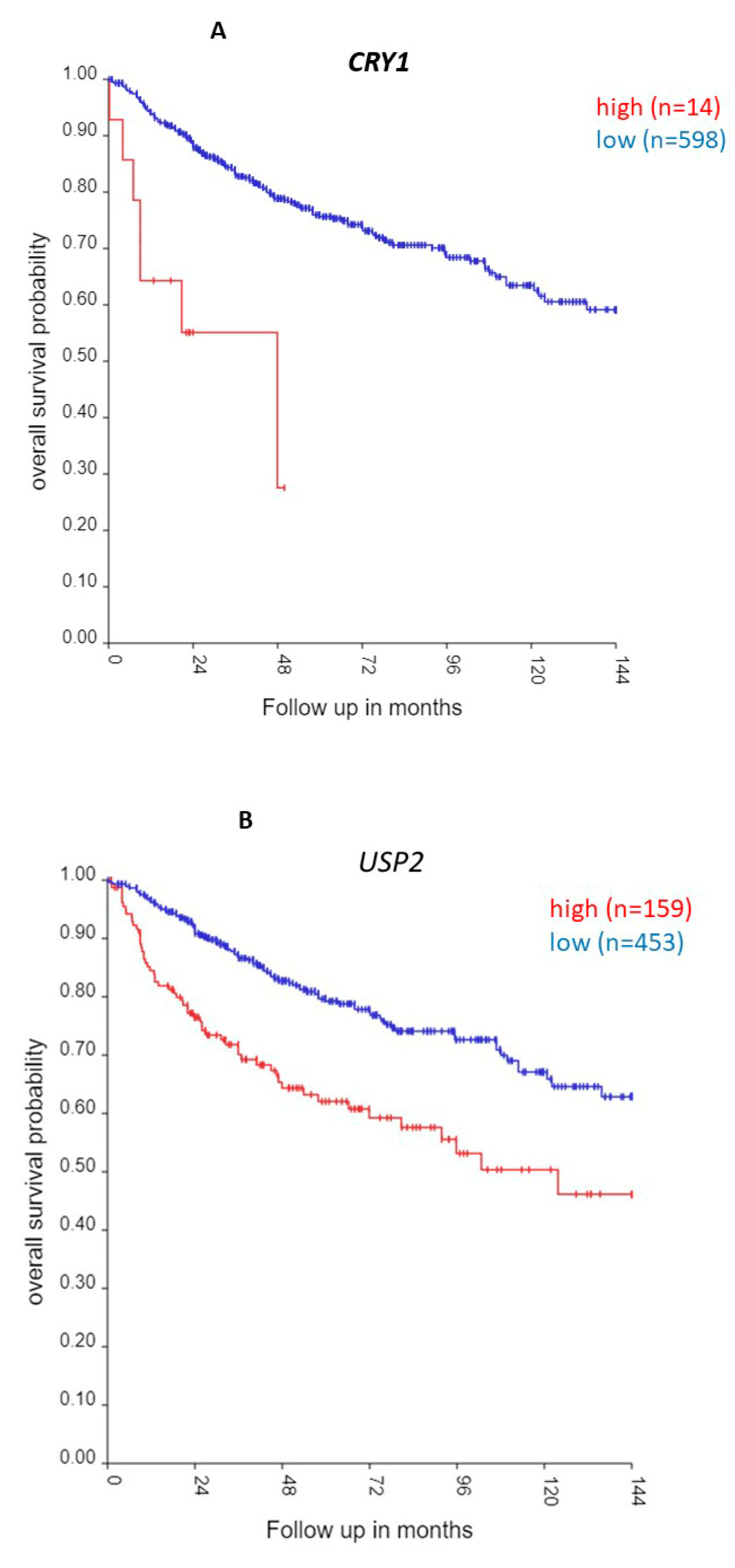

CRY1 and USP2 and Survival in Group 3 MB

PERIOD Genes and CSNK1D in MB: Role of Phosphorylation

The TIMELESS Connection to MB

Clock Genes, Ribosome Connection, and Copy Number Gain of Chromosome 17q

Clock Genes, the Casein Kinase Connection, and Copy Number Gain of Chromosome 17q

AANAT Another Chromosome 17q Gene Associated with Phototransduction

Ubiquitin Proteasome Pathway Regulation of Clock Genes in MB

Summary of Pathway Analysis of Clock Gene Correlates

| CLOCK genes | Number of correlates r > 0.50 | Most significant KEGG pathways over-represented | # of genes representing pathway | p value for pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THRA/NR1D1 | 1041 | ribosome | 59 | 1.44 x 10-80 |

| CIPC (KIAA1737) | 1063 | ribosome | 57 | 1.34 x 10-73 |

| FBXL21 | 605 | ribosome | 44 | 2.32 x 10-74 |

| MYCBP2 | 423 | ribosome | 29 | 1.34 x 10-48 |

| UTS2/PER3 | 18 | circadian rhythm | 3 | 2.62 x 10-43 |

| RORA | 184 | phototransduction | 7 | 2.30 x 10-33 |

| NPAS2 | 85 | synaptic vesicle cycle | 6 | 2.09 x 10-21 |

| CRY2 | 52 | GABAergic synapse | 5 | 4.38 x 10-19 |

| TIMELESS | 31 | Fanconi anemia | 3 | 1.07 x 10-18 |

| BTRC | 34 | Oocyte meiosis | 4 | 5.61 x 10-12 |

| USP2 | 161 | phototransduction | 4 | 1.74 x 10-11 |

| AANAT | 157 | phototransduction | 4 | 1.74 x 10-11 |

| BHLHE40 | 148 | WNT signaling | 10 | 2.47 x 10-09 |

| DBP | 62 | GABAergic synapse | 4 | 3.98 x 10-09 |

| FBXW7 | 88 | morphine addiction | 5 | 3.98 x 10-08 |

| NFIL3 | 82 | Hippo signaling | 5 | 3.28 x 10-06 |

| CSNK1D | 105 | prolactin signaling | 4 | 3.45 x 10-06 |

| CRY1 | 139 | peroxisome | 4 | 1.12 x 10-03 |

| PER2 | 22 | circadian rhythm | 1 | 2.13 x 10-03 |

| FBXL3 | 37 | circadian rhythm | 1 | 4.90 x 10-02 |

| ARNTL (BMAL1) | 8 | * | ||

| ARNTL2 (BMAL2) | 0 | * | ||

| PER1 | 5 | * | ||

| RORB | 0 | * | ||

| LINGO4/RORC | 0 | * | ||

| FBXL15 | 0 | * |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, R.C. The discoveries of molecular mechanisms for the circadian rhythm: The 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Biomed J. 2018, 41, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhr, E.D.; Takahashi, J.S. Molecular components of the Mammalian circadian clock. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2013, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lamia, K.A.; Storch, K.F.; Weitz, C.J. Physiological significance of a peripheral tissue circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008, 105, 15172–15177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre, A. Clock genes in mammalian peripheral tissues. Cell Tissue Res. 2002, 309, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K.H.; Takahashi, J.S. Circadian clock genes and the transcriptional architecture of the clock mechanism. J Mol Endocrinol. 2019, 63, R93–R102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Lahens, N.F.; Ballance, H.I.; Hughes, M.E.; Hogenesch, J.B. A circadian gene expression atlas in mammals: Implications for biology and medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014, 111, 16219–16224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvidis, C.; Koutsilieris, M. Circadian rhythm disruption in cancer biology. Mol Med. 2012, 18, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papagiannakopoulos T, Bauer MR, Davidson SM, Heimann M, Subbaraj L, Bhutkar A; et al. Circadian Rhythm Disruption Promotes Lung Tumorigenesis. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 324–331.

- Sulli, G.; Lam, M.T.Y.; Panda, S. Interplay between Circadian Clock and Cancer: New Frontiers for Cancer Treatment. Trends Cancer. 2019, 5, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reszka, E.; Zienolddiny, S. Epigenetic Basis of Circadian Rhythm Disruption in Cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2018, 1856:173-201.

- Numata M, Hirano A, Yamamoto Y, Yasuda M, Miura N, Sayama K; et al. Metastasis of Breast Cancer Promoted by Circadian Rhythm Disruption due to Light/Dark Shift and its Prevention by Dietary Quercetin in Mice. J Circadian Rhythms. 2021, 19:2.

- Stevens, R.G.; Brainard, G.C.; Blask, D.E.; Lockley, S.W.; Motta, M.E. Breast cancer and circadian disruption from electric lighting in the modern world. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014, 64, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, C.; Cao, Y.; Li, J.; Bi, F. Major roles of the circadian clock in cancer. Cancer Biol Med. 2023, 20, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V; et al. Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting. Lancet Oncol. 2007, 8, 1065–1066.

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, Z.; Nice, E.; Huang, C.; Zhang, W.; Tang, Y. Circadian rhythms and cancers: The intrinsic links and therapeutic potentials. J Hematol Oncol. 2022, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikanta, S.B.; Cermakian, N. To Ub or not to Ub: Regulation of circadian clocks by ubiquitination and deubiquitination. J Neurochem. 2021, 157, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Wu, N.; Lazar, M.A. Nuclear receptor Rev-erbalpha: A heme receptor that coordinates circadian rhythm and metabolism. Nucl Recept Signal. 2010, 8:e001.

- Zhang-Sun ZY, Xu XZ, Escames G, Lei WR, Zhao L, Zhou YZ; et al. Targeting NR1D1 in organ injury: Challenges and prospects. Mil Med Res. 2023, 10, 62.

- Cox, K.H.; Takahashi, J.S. Introduction to the Clock System. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021, 1344:3-20.

- Busino L, Bassermann F, Maiolica A, Lee C, Nolan PM, Godinho SI; et al. SCFFbxl3 controls the oscillation of the circadian clock by directing the degradation of cryptochrome proteins. Science. 2007, 316, 900–904.

- Siepka SM, Yoo SH, Park J, Song W, Kumar V, Hu Y; et al. Circadian mutant Overtime reveals F-box protein FBXL3 regulation of cryptochrome and period gene expression. Cell. 2007, 129, 1011–1023.

- Dardente, H.; Mendoza, J.; Fustin, J.M.; Challet, E.; Hazlerigg, D.G. Implication of the F-Box Protein FBXL21 in circadian pacemaker function in mammals. PLoS ONE. 2008, 3, e3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano A, Yumimoto K, Tsunematsu R, Matsumoto M, Oyama M, Kozuka-Hata H; et al. FBXL21 regulates oscillation of the circadian clock through ubiquitination and stabilization of cryptochromes. Cell. 2013, 152, 1106–1118.

- Wirianto M, Yang J, Kim E, Gao S, Paudel KR, Choi JM; et al. The GSK-3beta-FBXL21 Axis Contributes to Circadian TCAP Degradation and Skeletal Muscle Function. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 108140.

- Reischl S, Vanselow K, Westermark PO, Thierfelder N, Maier B, Herzel H; et al. Beta-TrCP1-mediated degradation of PERIOD2 is essential for circadian dynamics. J Biol Rhythms. 2007, 22, 375–386.

- Takahashi, J.S.; Hong, H.K.; Ko, C.H.; McDearmon, E.L. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: Implications for physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008, 9, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najumuddin, Fakhar M, Gul M, Rashid S. Interactive structural analysis of betaTrCP1 and PER2 phosphoswitch binding through dynamics simulation assay. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018, 651:34-42.

- Zhao X, Hirota T, Han X, Cho H, Chong LW, Lamia K; et al. Circadian Amplitude Regulation via FBXW7-Targeted REV-ERBalpha Degradation. Cell. 2016, 165, 1644–1657.

- Tong X, Buelow K, Guha A, Rausch R, Yin L. USP2a protein deubiquitinates and stabilizes the circadian protein CRY1 in response to inflammatory signals. J Biol Chem. 2012, 287, 25280–25291.

- Stojkovic, K.; Wing, S.S.; Cermakian, N. A central role for ubiquitination within a circadian clock protein modification code. Front Mol Neurosci. 2014, 7:69.

- Yang Y, Duguay D, Bedard N, Rachalski A, Baquiran G, Na CH; et al. Regulation of behavioral circadian rhythms and clock protein PER1 by the deubiquitinating enzyme USP2. Biol Open. 2012, 1, 789–801.

- Scoma, H.D.; Humby, M.; Yadav, G.; Zhang, Q.; Fogerty, J.; Besharse, J.C. The de-ubiquitinylating enzyme, USP2, is associated with the circadian clockwork and regulates its sensitivity to light. PLoS ONE. 2011, 6, e25382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura H, Hashimoto M. USP2-Related Cellular Signaling and Consequent Pathophysiological Outcomes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22.

- Siepka, S.M.; Yoo, S.H.; Park, J.; Lee, C.; Takahashi, J.S. Genetics and neurobiology of circadian clocks in mammals. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2007, 72, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godinho SI, Maywood ES, Shaw L, Tucci V, Barnard AR, Busino L; et al. The after-hours mutant reveals a role for Fbxl3 in determining mammalian circadian period. Science. 2007, 316, 897–900.

- Taylor MD, Northcott PA, Korshunov A, Remke M, Cho YJ, Clifford SC; et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: The current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 123, 465–472.

- Cho YJ, Tsherniak A, Tamayo P, Santagata S, Ligon A, Greulich H; et al. Integrative genomic analysis of medulloblastoma identifies a molecular subgroup that drives poor clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29, 1424–1430.

- Kool M, Koster J, Bunt J, Hasselt NE, Lakeman A, van Sluis P; et al. Integrated genomics identifies five medulloblastoma subtypes with distinct genetic profiles, pathway signatures and clinicopathological features. PLoS ONE. 2008, 3, e3088. [Google Scholar]

- Northcott PA, Korshunov A, Witt H, Hielscher T, Eberhart CG, Mack S; et al. Medulloblastoma comprises four distinct molecular variants. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29, 1408–1414.

- Cavalli FMG, Remke M, Rampasek L, Peacock J, Shih DJH, Luu B; et al. Intertumoral Heterogeneity within Medulloblastoma Subgroups. Cancer Cell. 2017, 31, 737–754.

- Weishaupt H, Johansson P, Sundstrom A, Lubovac-Pilav Z, Olsson B, Nelander S; et al. Batch-normalization of cerebellar and medulloblastoma gene expression datasets utilizing empirically defined negative control genes. Bioinformatics. 2019, 35, 3357–3364.

- Yamanaka, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Todo, T.; Honma, K.; Honma, S. Loss of circadian rhythm and light-induced suppression of pineal melatonin levels in Cry1 and Cry2 double-deficient mice. Genes Cells. 2010, 15, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzezinski, A.; Rai, S.; Purohit, A.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. Melatonin, Clock Genes, and Mammalian Reproduction: What Is the Link? Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(24).

- Sato F, Kawamoto T, Fujimoto K, Noshiro M, Honda KK, Honma S; et al. Functional analysis of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor DEC1 in circadian regulation. Interaction with BMAL1. Eur J Biochem. 2004, 271, 4409–4419.

- Kiss, Z.; Mudryj, M.; Ghosh, P.M. Non-circadian aspects of BHLHE40 cellular function in cancer. Genes Cancer. 2020, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves I, Pokorny R, Byrdin M, Hoang N, Ritz T, Brettel K; et al. The cryptochromes: Blue light photoreceptors in plants and animals. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2011, 62, 335–364.

- Schwartz, W.J.; Tavakoli-Nezhad, M.; Lambert, C.M.; Weaver, D.R.; de la Iglesia, H.O. Distinct patterns of Period gene expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus underlie circadian clock photoentrainment by advances or delays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011, 108, 17219–17224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurien P, Hsu PK, Leon J, Wu D, McMahon T, Shi G; et al. TIMELESS mutation alters phase responsiveness and causes advanced sleep phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019, 116, 12045–12053.

- Sangoram AM, Saez L, Antoch MP, Gekakis N, Staknis D, Whiteley A; et al. Mammalian circadian autoregulatory loop: A timeless ortholog and mPer1 interact and negatively regulate CLOCK-BMAL1-induced transcription. Neuron. 1998, 21, 1101–1113.

- Vipat, S.; Moiseeva, T.N. The TIMELESS Roles in Genome Stability and Beyond. J Mol Biol. 2024, 436, 168206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho F, Cilio M, Guo Y, Virshup DM, Patel K, Khorkova O; et al. Human casein kinase Idelta phosphorylation of human circadian clock proteins period 1 and 2. FEBS Lett. 2001, 489, 159–165.

- Emery, P.; Reppert, S.M. A rhythmic Ror. Neuron. 2004, 43, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiong, Y.; Tao, R.; Panayi, A.C.; Mi, B.; Liu, G. Emerging Insight Into the Role of Circadian Clock Gene BMAL1 in Cellular Senescence. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 915139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, T.D. Evolution of phototransduction, vertebrate photoreceptors and retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2013, 36, 52–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, C.M.; Hawes, S.M.; Kees, U.R.; Gottardo, N.G.; Dallas, P.B. Gene expression analyses of the spatio-temporal relationships of human medulloblastoma subgroups during early human neurogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9, e112909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aninye, I.O.; Matsumoto, S.; Sidhaye, A.R.; Wondisford, F.E. Circadian regulation of Tshb gene expression by Rev-Erbalpha (NR1D1) and nuclear corepressor 1 (NCOR1). J Biol Chem. 2014, 289, 17070–17077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, M.A.; Hodin, R.A.; Darling, D.S.; Chin, W.W. A novel member of the thyroid/steroid hormone receptor family is encoded by the opposite strand of the rat c-erbA alpha transcriptional unit. Mol Cell Biol. 1989, 9, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Preitner N, Damiola F, Lopez-Molina L, Zakany J, Duboule D, Albrecht U; et al. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell. 2002, 110, 251–260.

- Reppert, S.M.; Weaver, D.R. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 2002, 418, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomatou, G.; Karachaliou, A.; Veloudiou, O.Z.; Karvela, A.; Syrigos, N.; Kotteas, E. The Role of REV-ERB Receptors in Cancer Pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda HR, Hayashi S, Chen W, Sano M, Machida M, Shigeyoshi Y; et al. System-level identification of transcriptional circuits underlying mammalian circadian clocks. Nat Genet. 2005, 37, 187–192.

- Keniry, M.; Dearth, R.K.; Persans, M.; Parsons, R. New Frontiers for the NFIL3 bZIP Transcription Factor in Cancer, Metabolism and Beyond. Discoveries (Craiova). 2014, 2, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Chen, D.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Y.; Yang, W. A new border for circadian rhythm gene NFIL3 in diverse fields of cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2023, 25, 1940–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao WN, Malinin N, Yang FC, Staknis D, Gekakis N, Maier B; et al. CIPC is a mammalian circadian clock protein without invertebrate homologues. Nat Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 268–275.

- Mabbitt PD, Loreto A, Dery MA, Fletcher AJ, Stanley M, Pao KC; et al. Structural basis for RING-Cys-Relay E3 ligase activity and its role in axon integrity. Nat Chem Biol. 2020, 16, 1227–1236.

- Yin L, Joshi S, Wu N, Tong X, Lazar MA. E3 ligases Arf-bp1 and Pam mediate lithium-stimulated degradation of the circadian heme receptor Rev-erb alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107, 11614–11619.

- Beker MC, Caglayan B, Caglayan AB, Kelestemur T, Yalcin E, Caglayan A; et al. Interaction of melatonin and Bmal1 in the regulation of PI3K/AKT pathway components and cellular survival. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 19082.

- Ferretti, E.; De Smaele, E.; Di Marcotullio, L.; Screpanti, I.; Gulino, A. Hedgehog checkpoints in medulloblastoma: The chromosome 17p deletion paradigm. Trends Mol Med. 2005, 11, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caster, S.Z.; Castillo, K.; Sachs, M.S.; Bell-Pedersen, D. Circadian clock regulation of mRNA translation through eukaryotic elongation factor eEF-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016, 113, 9605–9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenas C, van de Sandt L, Edlund K, Lohr M, Hellwig B, Marchan R; et al. Loss of circadian clock gene expression is associated with tumor progression in breast cancer. Cell Cycle. 2014, 13, 3282–3291.

- Nelson N, Lombardo J, Matlack L, Smith A, Hines K, Shi W; et al. Chronoradiobiology of Breast Cancer: The Time Is Now to Link Circadian Rhythm and Radiation Biology. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23.

- Li, H.X. The role of circadian clock genes in tumors. Onco Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 3645–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglin F, Chan P, Pan Y, Soni S, Qu M, Spiller ER; et al. Clocking cancer: The circadian clock as a target in cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2021, 40, 3187–3200.

- Shafi AA, McNair CM, McCann JJ, Alshalalfa M, Shostak A, Severson TM; et al. The circadian cryptochrome, CRY1, is a pro-tumorigenic factor that rhythmically modulates DNA repair. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 401.

- Pan Y, van der Watt PJ, Kay SA. E-box binding transcription factors in cancer. Front Oncol. 2023, 13, 1223208.

- Mirza, M.U.; Ahmad, S.; Abdullah, I.; Froeyen, M. Identification of novel human USP2 inhibitor and its putative role in treatment of COVID-19 by inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 papain-like (PLpro) protease. Comput Biol Chem. 2020, 89, 107376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis MI, Pragani R, Fox JT, Shen M, Parmar K, Gaudiano EF; et al. Small Molecule Inhibition of the Ubiquitin-specific Protease USP2 Accelerates cyclin D1 Degradation and Leads to Cell Cycle Arrest in Colorectal Cancer and Mantle Cell Lymphoma Models. J Biol Chem. 2016, 291, 24628–24640.

- Yang Y, Duguay D, Fahrenkrug J, Cermakian N, Wing SS. USP2 regulates the intracellular localization of PER1 and circadian gene expression. J Biol Rhythms. 2014, 29, 243–256.

- Xu P, Ianes C, Gartner F, Liu C, Burster T, Bakulev V; et al. Structure, regulation, and (patho-)physiological functions of the stress-induced protein kinase CK1 delta (CSNK1D). Gene. 2019, 715, 144005.

- Kennaway, D.J.; Varcoe, T.J.; Voultsios, A.; Salkeld, M.D.; Rattanatray, L.; Boden, M.J. Acute inhibition of casein kinase 1delta/epsilon rapidly delays peripheral clock gene rhythms. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015, 398, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu J, Margol AS, Shukla A, Ren X, Finlay JL, Krieger MD; et al. Disseminated Medulloblastoma in a Child with Germline BRCA2 6174delT Mutation and without Fanconi Anemia. Front Oncol. 2015, 5, 191.

- Jouffe C, Cretenet G, Symul L, Martin E, Atger F, Naef F; et al. The circadian clock coordinates ribosome biogenesis. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001455.

- Pelletier, J.; Thomas, G.; Volarevic, S. Ribosome biogenesis in cancer: New players and therapeutic avenues. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018, 18, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, P.; Partch, C.L. New insights into non-transcriptional regulation of mammalian core clock proteins. J Cell Sci. 2020, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackshaw, S.; Snyder, S.H. Developmental expression pattern of phototransduction components in mammalian pineal implies a light-sensing function. J Neurosci. 1997, 17, 8074–8082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamaze, A.; Jepson, J.E.C.; Akpoghiran, O.; Koh, K. Antagonistic Regulation of Circadian Output and Synaptic Development by JETLAG and the DYSCHRONIC-SLOWPOKE Complex. iScience. 2020, 23, 100845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue S, Tang LY, Tang Y, Tang Y, Shen QH, Ding J; et al. Requirement of Smurf-mediated endocytosis of Patched1 in sonic hedgehog signal reception. Elife. 2014, 3.

- Chan, A.B.; Lamia, K.A. Cancer, hear my battle CRY. J Pineal Res. 2020, 69, e12658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crusio, K.M.; King, B.; Reavie, L.B.; Aifantis, I. The ubiquitous nature of cancer: The role of the SCF(Fbw7) complex in development and transformation. Oncogene. 2010, 29, 4865–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh CH, Bellon M, Nicot C. FBXW7: A critical tumor suppressor of human cancers. Mol Cancer. 2018, 17, 115.

- Virdee, S. An atypical ubiquitin ligase at the heart of neural development and programmed axon degeneration. Neural Regen Res. 2022, 17, 2347–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ‘CLOCK’ genes | F (anova) Cavalli 4 groups |

p | F (anova) Swartling 4 MB groups plus NT |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THRA/NR1D1 | 423.43 | 1.43 x 10-161 | 461.14 | 4.34 x 10-263 |

| CIPC (KIAA1737) | 379.47 | 1.67 x 10-150 | 486.84 | 3.39 x 10-273 |

| FBXL21 | 289.07 | 4.14 x 10-125 | Not found* | |

| USP2 | 271.01 | 1.57 x 10-119 | 508.57 | 1.63 x 10-281 |

| MYCBP2 (PAM) | 231.63 | 1.13 x 10-106 | 350.75 | 6..62 x 10-216 |

| CRY1 | 160.65 | 1.29 x 10-80 | 289.27 | 1.69 x 10-186 |

| BHLHE40 | 139.4 | 6.08 x 10-72 | 209.02 | 7.20 x 10-144 |

| CSNK1D | 112.9 | 1.88 x 10-60 | 159.17 | 1.91 x 10-114 |

| NFIL3 | 106.98 | 9.10 x 10-58 | Not found* | |

| PER2 | 101.21 | 4.08 x 10-55 | 118.11 | 6.79 x 10-129 |

| NPAS2 | 92.82 | 3.53 x 10-51 | 283.34 | 1.59 x 10-183 |

| BTRC | 83.47 | 1.11 x 10-46 | 164.35 | 1.26 x 10-117 |

| RORA | 78.39 | 3.52 x 10-44 | 85.84 | 5.18 x 10-66 |

| CLOCK | 77.07 | 1.59 x 10-43 | 126.36 | 1.32 x 10-93 |

| TIMELESS | 67.05 | 1.82 x 10-38 | 188.16 | 7.34 x 10-132 |

| ARNTL (BMAL1) | 59.29 | 1.91 x 10-34 | 140.76 | 6.58 x 10-103 |

| FBXL15 | 57.12 | 2.67 x 10-33 | 72.93 | 9.80 x 10-57 |

| DBP | 55.93 | 1.14 x 10-32 | 109.1 | 4.06 x 10-82 |

| KCNMA1 | 36.6 | 4.23 x 10-22 | Not found* | |

| CRY2 | 35.25 | 2.48 x 10-21 | 115.25 | 2.96 x 10-86 |

| PER3 | 34.22 | 9.45 x 10-21 | 100.54 | 2.81 x 10-76 |

| FBXL3 | 27.84 | 4.37 x 10-17 | 55.21 | 1.31 x 10-43 |

| FBXW7 | 22.21 | 8.55 x 10-14 | 71.21 | 1.74 x 10-55 |

| NR1D2 | 19.64 | 2.87 x 10-12 | 40.21 | 4.14 x 10-32 |

| PER1 | 18.63 | 1.15 x 10-11 | 39.35 | 1.93 x 10-31 |

| ARNTL2 (BMAL2) | 12.57 | 5.01 x 10-08 | 34.48 | 1.26 x 10-27 |

| RORC | 9.86 | 2.20 x 10-06 | Not found | |

| RORB | 2.57 | 0.053 | 19.47 | 1.18 x 10-15 |

| Survival related ‘CLOCK’ genes | Chi squared | Kaplan-Meier p values | HR | Hazard ratio p values |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRY1 | 22.33 | 2.29 x 10-06 | high worse | 1.4 | 0.00094 |

| USP2 | 21.73 | 3.14 x 10-06 | high worse | 1.3 | 0.000035 |

| CLOCK | 20.21 | 6.96 x 10-06 | low worse | 0.61 | 0.024 |

| MYCBP2 (PAM) | 18.29 | 1.90x 10-05 | high worse | 1.5 | 0.018 |

| TIMELESS | 15.23 | 9.53 x 10-05 | high worse | ns | |

| UTS3/PER3** | 14.83 | 1.18 x 10-04 | low worse | 0.75 | 0.013 |

| FBXL21 | 13.63 | 2.23 x 10-04 | high worse | ns | |

| BTRC | 13.1 | 2.96 x 10-04 | low worse | ns | |

| ARNTL2 (BMAL2) | 12.91 | 3.27 x 10-04 | high worse | 1.5 | 0.0035 |

| CSNK1D | 11.5 | 6.95 x 10-04 | high worse | 2.2 | 0.0084 |

| BHLHE40 | 10.65 | 1.10 x 10-03 | low worse | ns | |

| NR1D2 | 10.62 | 1.12 x 10-03 | low worse | ns | |

| THRA/NR1D1** | 9.71 | 1.84 x 10-03 | high worse | ns | |

| RORA | 8.58 | 3.40 x 10-03 | high worse | ns | |

| RORB | 8.39 | 3.78 x 10-03 | high worse | 1.2 | 0.03 |

| PER1 | 8.25 | 4.08 x 10-03 | low worse | ns | |

| KCNMA1 | 6.96 | 8.35 x 10-03 | high worse | ns | |

| PER2 | 6.83 | 8.96 x 10-03 | high worse | ns | |

| NFIL3 | 6.67 | 9.80 x 10-03 | high worse | 1.3 | 0.034 |

| CRY2 | 6.15 | 1.3x 10-02 | high worse | ns | |

| DBP | 6.00 | 1.40 x 10-02 | high worse | ns | |

| FBXW7 | 5.76 | 1.60 x 10-02 | low worse | ns | |

| NPAS2 | 5.12 | 2.40 x 10-02 | high worse | ns | |

| AANAT | 4..95 | 2.60 x 10-02 | high worse | ns | |

| ARNTL (BMAL1) | 4.00 | 4.50 x10-02 | low worse | ns | |

| CIPC (KIAA1737) | 3.99 | 4.60 x10-02 | high worse | ns | |

| FBXL15 | 3.98 | 4.60 x 10-02 | low worse | ns | |

| LINGO4/RORC** | 3.16 | 0.76 x 10-1 | ns | ns | |

| FBXL3 | 2.89 | 8.90 x 10-02 | ns | ns |

| ‘CLOCK’ genes | Chromosomal location |

Means ± s.e. Normal |

Means ± s.e. Gain 17q |

p value for t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THRA/NR1D1 | 17q21.1 | 921.99 ± 16.44 | 1533.30 ± 22.89 | 1.57 x 10-84 |

| CIPC (KIAA1737) | 14q24.3 | 551.55 ± 10.71 | 891.27 ± 13.19 | 7.35 x 10-73 |

| CSNK1D | 17q25.3 | 647.89 ± 5.67 | 793.71 ± 5.70 | 9.19 x 10-60 |

| FBXL21 | 5q31.1 | 178.26 ± 12.47 | 525.69 ± 16.53 | 1.09 x 10-55 |

| MYCBP2/PAM | 13q22.3 | 530.72 ± 10.14 | 693.05 ± 8.66 | 2.08 x 10-29 |

| PER2 | 2q37.3 | 212.53 ± 3.20 | 273.45 ± 4.29 | 8.03 x 10-29 |

| NPAS2 | 2q11.2 | 188.29 ± 8.87 | 355.41 ± 12.84 | 2.41 x 10-26 |

| NFIL3 | 9q22.31 | 123.99 ± 2.75 | 165.33 ± 2.42 | 6.50 x 10-26 |

| CRY2 | 11p11.2 | 193.97 ± 2.33 | 236.28 ± 4.44 | 2.64 x 10-18 |

| BTRC | 10q24.32 | 329.77 ± 4.98 | 390.03 ± 5.61 | 3.80 x 10-15 |

| CLOCK | 4q12 | 425.20 ± 4.43 | 486.90 ± 6.79 | 1.06 x 10-14 |

| TIMELESS | 12q13.3 | 159.39 ± 3.22 | 189.19 ± 2.82 | 3.06 x 10-11 |

| BHLHE40 | 3p26.1 | 250.49 ± 10.80 | 164.57 ± 4.88 | 7.11 x 10-11 |

| DBP | 19q13.33 | 189.32 ± 3.99 | 230.81 ± 5.81 | 2.07 x 10-09 |

| PER1 | 17p13.1 | 137.78 ± 4.05 | 111.29 ± 2.51 | 2.67 x 10-07 |

| CRY1 | 12q23.3 | 224.89 ± 8.22 | 280.67 ± 8.54 | 3.52 x 10-06 |

| NR1D2 | 3p24.2 | 422.73 ± 6.49 | 463.72 ± 8.49 | 1.02 x 10-04 |

| USP2 | 11q23.3 | 276.55 ± 18.90 | 373.71 ± 14.59 | 1.11 x 10-04 |

| FBXL15 | 10q24.32 | 47.39 ± 0.46 | 49.86 ± 0.44 | 1.62 x 10-04 |

| FBXW7 | 4q31.3 | 260.54 ± 9.77 | 222.39 ± 3.97 | 1.08 x 10-03 |

| FBXL3 | 13q22.3 | 387.40 ± 4.54 | 409.41 ± 5.47 | 1.88 x 10-03 |

| ARNTL2 | 12p11.23 | 59.71 ± 1.30 | 64.99 ± 1.70 | 1.23 x 10-02 |

| KCNMA1 | 10q22.3 | 288.29 ± 11.66 | 326.16 ± 10.74 | 2.02 x 10-02 |

| AANAT | 17q25.1 | 45.16 ± 1.35 | 42.35 ± 0.94 | 8.14 x 10-02 ns |

| ARNTL | 11p15.3 | 96.57 ± 4.40 | 89.08 ± 2.77 | 1.78 x 10-01 ns |

| RORA | 15q22.2 | 283.04 ± 8.28 | 299.43 ± 8.91 | 1.81 x 10-01 ns |

| RORB | 9q21.13 | 61.65 ± 3.43 | 60.31 ± 3.03 | 7.76 x 10-01 ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).