1. Introduction

Cervical cancer ranks among the most prevalent malignant neoplasms affecting women. The global incidence and mortality rates of cervical cancer are experiencing a significant increase, posing a substantial threat to women's health. Despite advancements in current therapeutic modalities for cervical cancer, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, the propensity for recurrence and metastasis in advanced stages of the disease continues to yield suboptimal treatment outcomes. Consequently, the development of targeted therapeutic agents with minimal toxicity is essential for enhancing patient survival rates.

Cancer cells exhibit fourteen distinct characteristics that differentiate them from normal cells, serving as potential targets for cancer treatment [

1]. Exploiting these targets facilitates the selective eradication of tumor cells while minimizing damage to normal cells. Notably, metabolic abnormality is a significant characteristic of tumor cells. Consequently, targeting tumor metabolism emerges as an effective therapeutic strategy, as it impedes the proliferation and survival of cancer cells by disrupting their metabolic processes [

2]. Cancer cells exhibit distinct metabolic characteristics compared to normal cells, notably by favoring glucose uptake over its mitochondrial oxidation, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect. Therefore, the use of glycolysis inhibitors such as 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) could disrupt the glycolysis process and induced cell death [

3]. However, due to the fact that the microenvironment in which tumors are located in vivo is nutrient-deficient, tumor cells in proximity to blood vessels predominantly depend on oxidative phosphorylation for energy metabolism [

4], making glycolysis-targeted drugs unable to completely kill tumor cells [

5]. More and more studies showed that mitochondria also played an important role in the metabolic reprogramming of malignant tumors. The growth of melanoma B16 cells did not depend on the Warburg effect, but rather on mitochondrial metabolism [

6,

7]. Study from Knoblich revealed that during the formation of brain tumors in Drosophila, mitochondrial membranes underwent fusion. This notable alteration in mitochondrial morphology enhances the efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation, subsequently resulting in elevated levels of NAD

+ and NADH [

7]. In summary, the remodeling of metabolism due to low glucose availability in the tumor microenvironment, characterized by a shift towards oxidative phosphorylation, presents a strategic target for cancer therapy. By focusing on mitochondrial metabolism, we can develop innovative treatment modalities that may improve patient outcomes and overcome resistance to conventional therapies [

8].

Approximately 90% of cellular energy is produced in the form of ATP through OXPHOS process of mitochondria [

9]. In recent years, an increasing number of small-molecule drugs that efficiently and selectively inhibited OXPHOS have been developed [

10,

11]. EVT-701 was a novel small-molecule inhibitor for diffuse B-cell lymphoma, showing good efficacy in vitro and in vivo [

11]. In addition, Kazuki Heishima et al. found that petasin, a plant extract, was an inhibitor that mainly inhibited mitochondrial complex I in tumors. Mubritinib, a human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2) inhibitor, exhibited its anticancer properties by inhibiting complex I [

12]. Recent studies have shown that Nebivolol, a β-adrenergic receptor blocker, limited the growth of tumor cells by inhibiting the activity of mitochondrial complex I and ATP production [

13].

Gboxin is a novel small molecule that has emerged as a promising therapeutic agent specifically targeting glioblastoma, a highly aggressive form of brain cancer. The compound inhibited the growth of GBM by suppressing the activity of mitochondrial ATP synthase, yet it did not inhibit the growth of mouse embryonic fibro blasts or neonatal astrocytes [

14]. However, the role and mechanism of action of Gboxin in cervical cancer cells within a low-glucose microenvironment require further clarification, and its specific anticancer mechanism has yet to be fully elucidated. In this study, we found that Gboxin significantly inhibited survival of cervical cancer cell by promoting autophagy, apoptosis, and ferroptosis under low-glucose conditions. Mechanistic analysis revealed that Gboxin inhibited ATP synthesis and activated the AMPK pathway by targeting mitochondrial complex V, which promoted autophagy and lowered p62 protein levels. This reduction in p62 facilitated Nrf2 degradation via the p62-Keap1-Nrf2 axis, decreasing antioxidant capacity and inducing apoptosis and ferroptosis in cervical cancer cells. Our study will provide new potential therapeutic targets and strategies for the treatment of cervical cancer.

3. Discussion

Cervical cancer is one of the major malignant tumors in the female reproductive system [

20]. Searching for novel compounds characterized by low toxicity and high selectivity in targeting cervical cancer is of great significance for improving patient survival rates. Studies have shown that mitochondria play a key role in tumor formation and development [

9]. Given that the rate of vascularization is typically slower than the proliferation rate of tumor tissues, and nutrient deficiency is the main characteristic of the tumor microenvironment [

21]. It has been reported that the glucose metabolism pattern of tumor cells undergoes a shift from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation in the microenvironment, and the cells in the tumor microenvironment rely more on the functions of mitochondria to survive [

23]. Therefore, targeting mitochondria may be a better way to treat cancers. Studies has found that Gboxin inhibited the growth of GBM by inhibiting the activity of mitochondrial complex, and had no inhibitory effect on normal cells. However, until now, its role and mechanism in a low-glucose microenvironment are still unclear. This study explored the inhibitory effect and mechanism of Gboxin on the survival of cervical cancer cells under low-glucose conditions, aiming to provide new theoretical basis for the application of Gboxin in the treatment of cervical cancer.

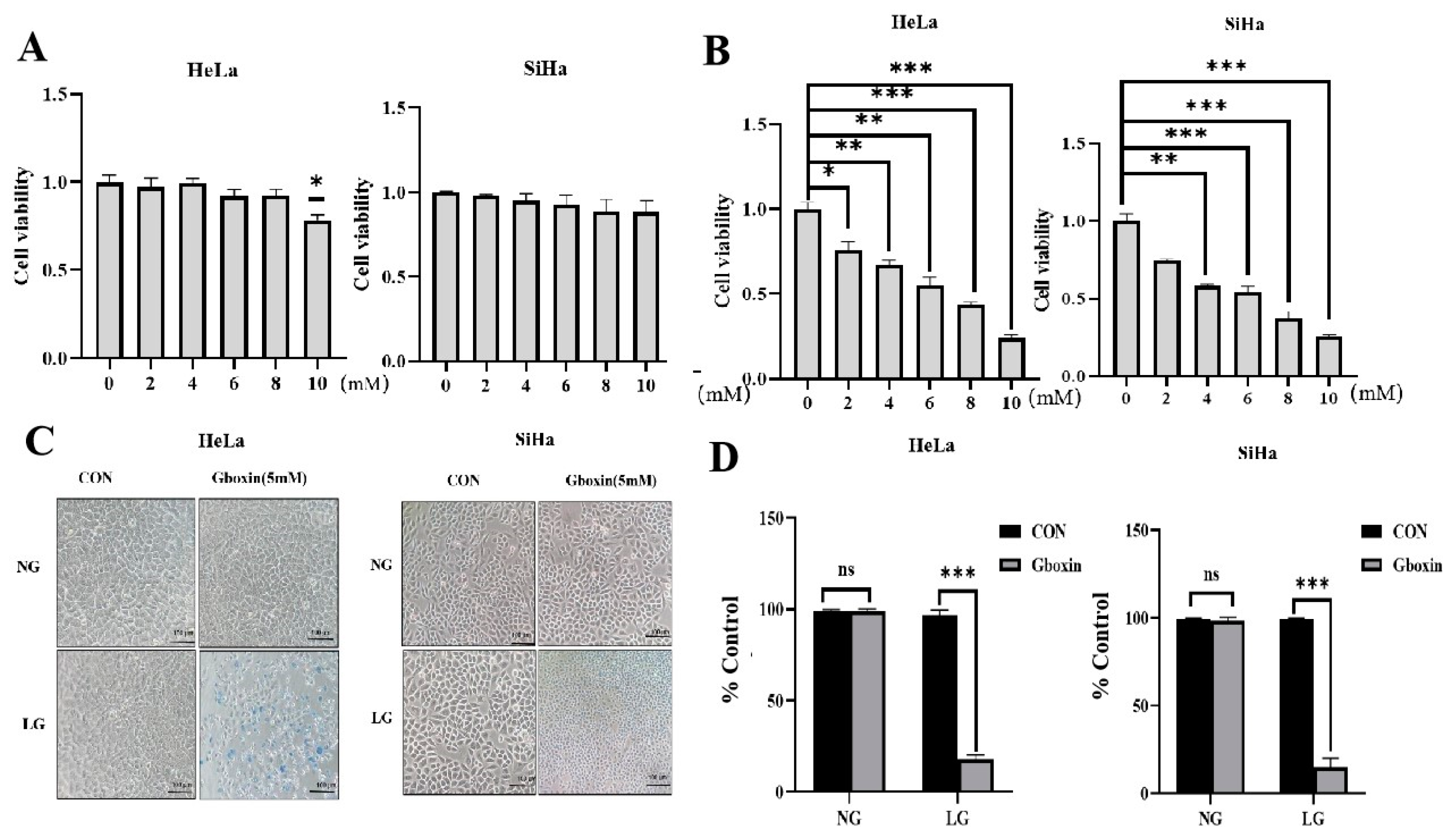

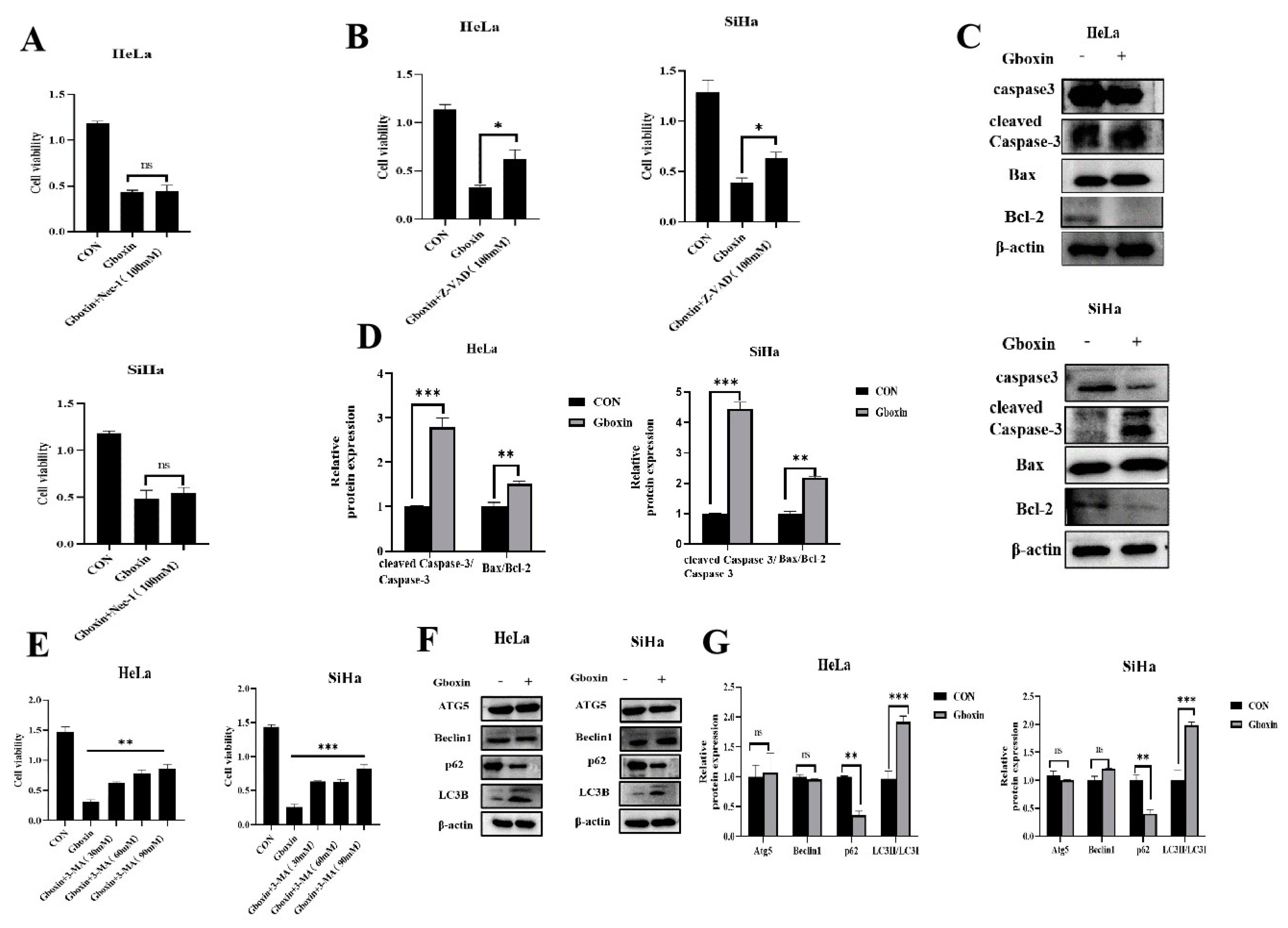

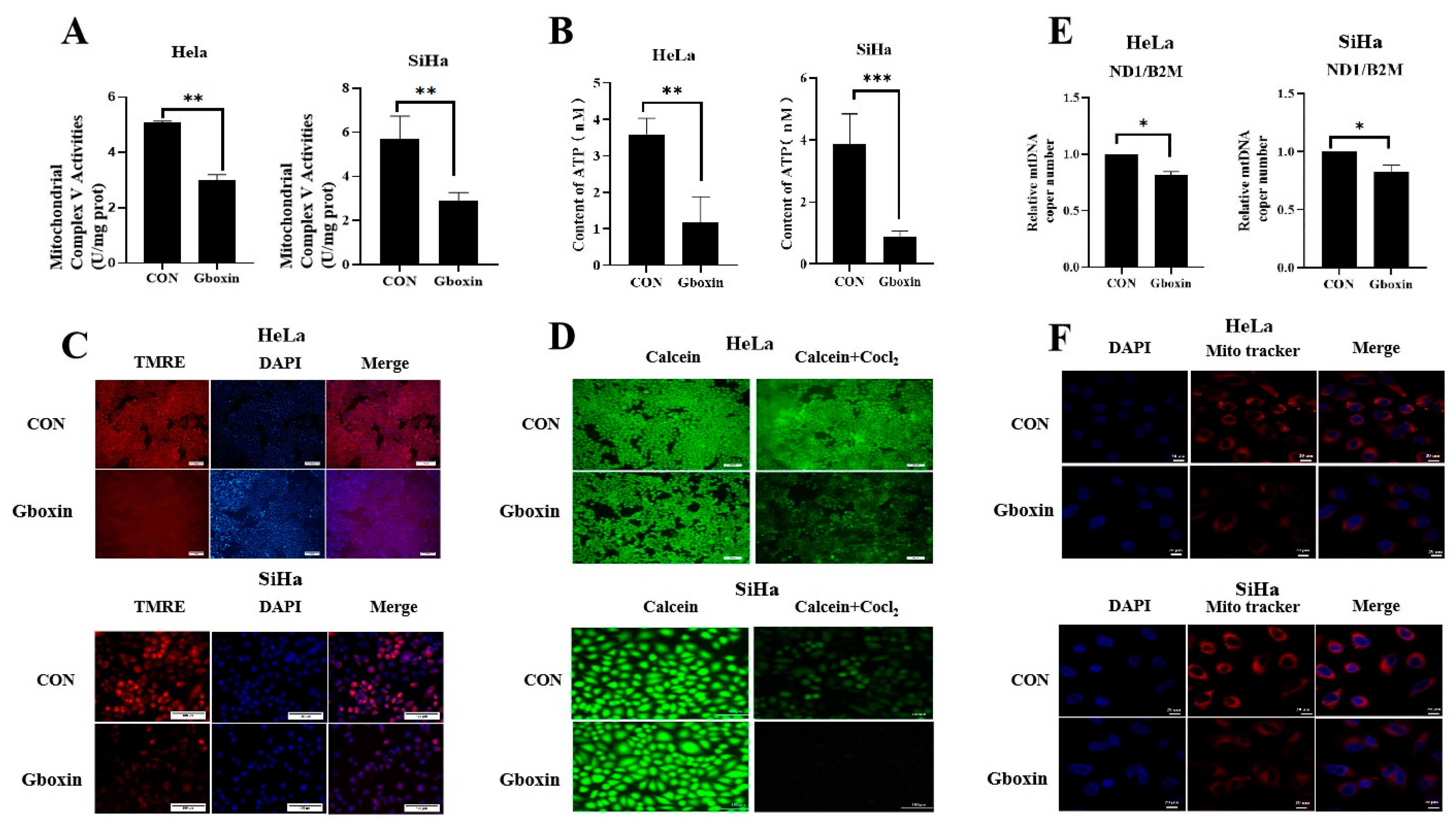

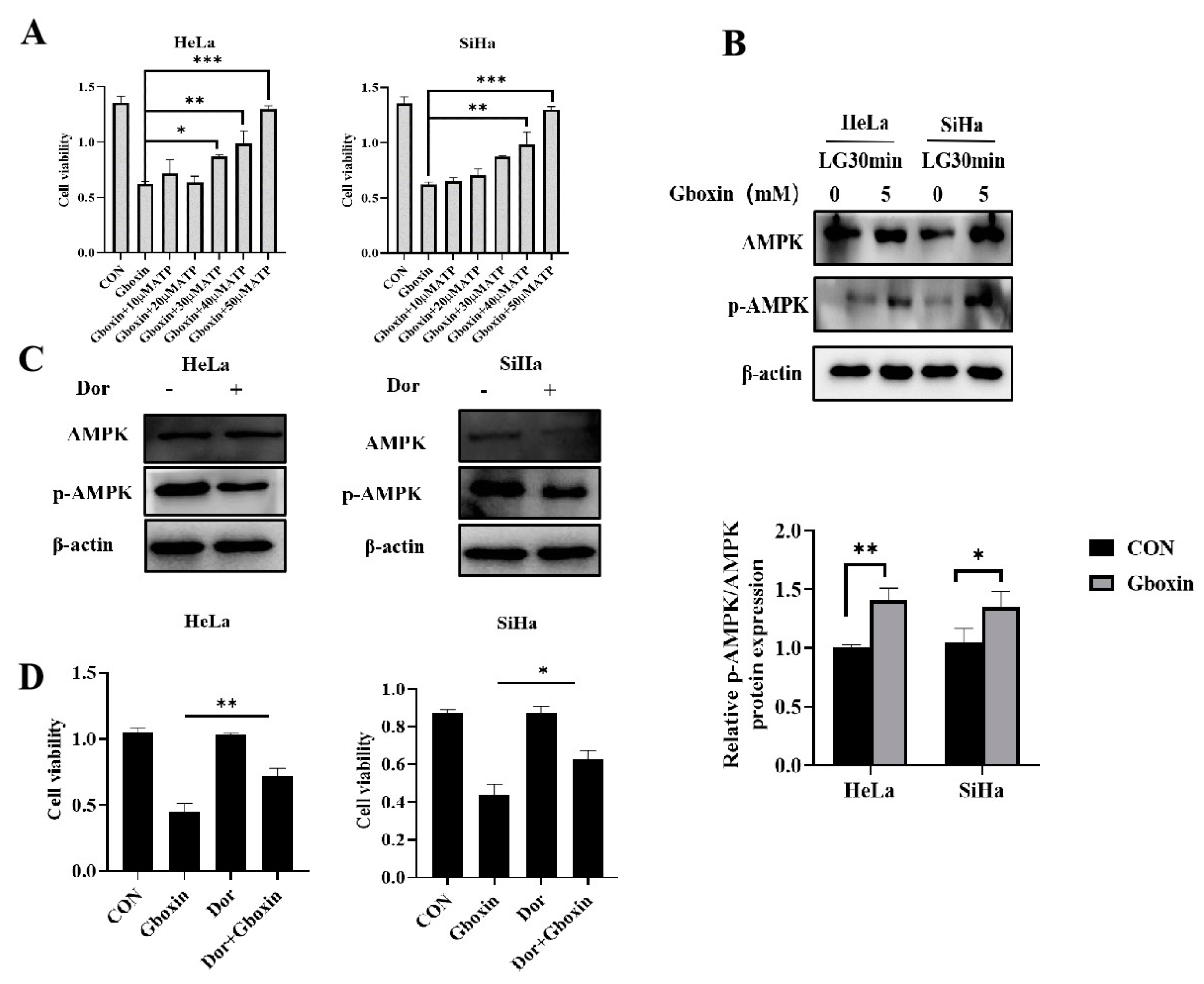

The glucose concentration in the low-glucose medium we used is 1 mM in our study. In contrast to normal glucose concentrations, Gboxin markedly decreased the viability of cervical cancer cells under low-glucose conditions. The potential mechanisms underlying this observation are as follows: Firstly, low glucose levels impaired the glycolytic capacity of cervical cancer cells, prompting a metabolic shift towards mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, a phenomenon corroborated by our previous research. Secondly, Gboxin inhibited mitochondrial complex V, thereby impeding oxidative phosphorylation in cervical cancer cells and disrupting their primary energy supply pathway.

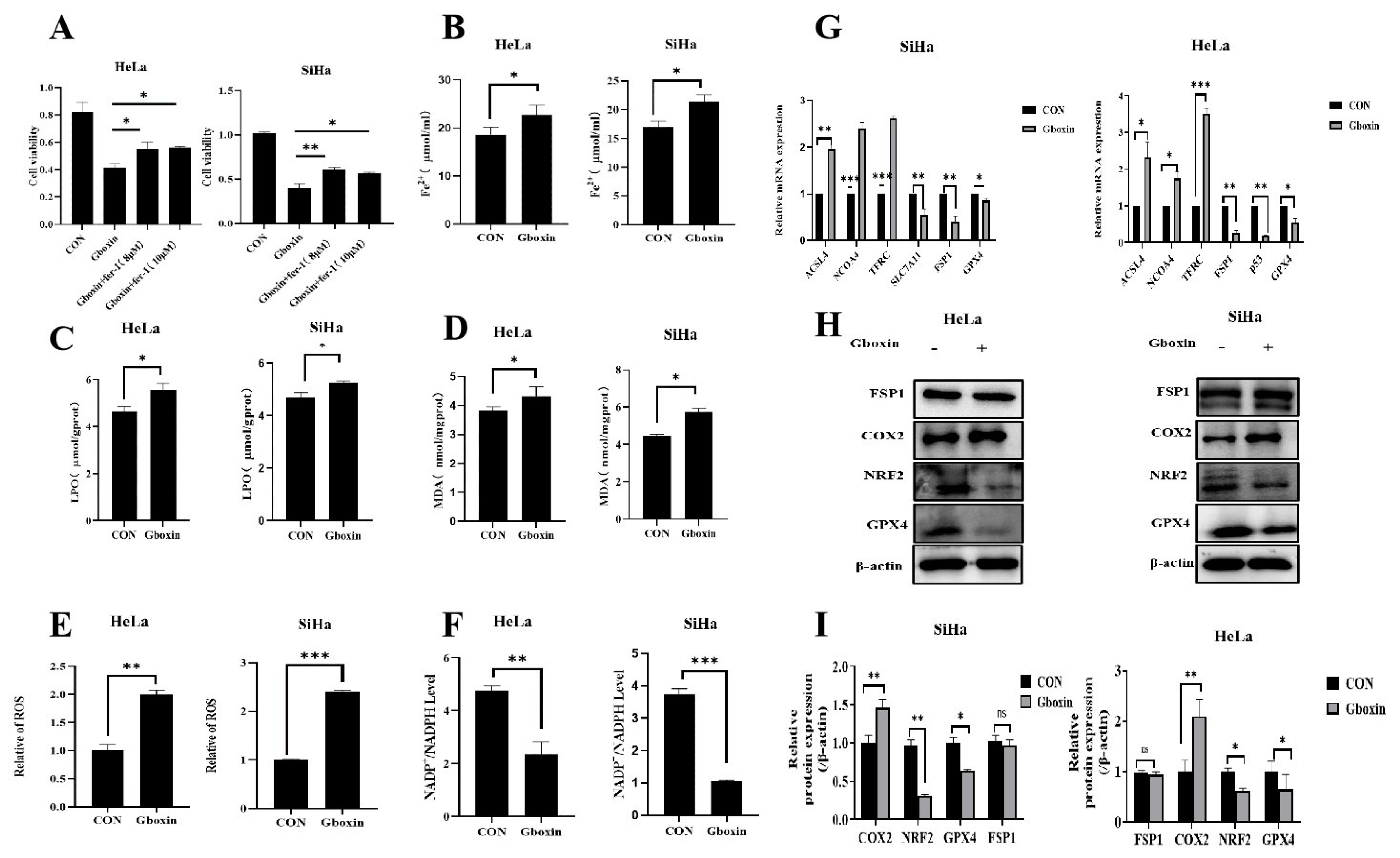

Studies has demonstrated a close association between mitochondrial dysfunction and ferroptosis [

22]. The iron in mitochondria is mainly involved in several critical biological processes, including energy metabolism, the synthesis of iron-sulfur clusters, and the regulation of ROS production. After the accumulation of mitochondrial ROS, it can react with the polyunsaturated fatty acids on the mitochondrial membrane, leading to lipid peroxidation. A series of studies have shown that the abnormal mitochondria function can produce a sufficient amount of ROS, which is necessary for initiating ferroptosis. This study found that Gboxin inhibited the activity of mitochondrial complex V, disrupted the function of mitochondria, and produced a large amount of ROS. In addition, Gboxin reduced the expressions of GPX4 and Nrf2 in cervical cancer cells under low-glucose conditions, and these two proteins not only regulated ferroptosis but also played key roles in inhibiting cell apoptosis [

23,

24].

This study has confirmed that Gboxin induced cell apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis under low-glucose culture conditions. However, the interrelationships among these three processes remain to be elucidated. Studies have found that ferroptosis greatly increased the sensitivity of cells to apoptosis-inducing agents [

25]. Apoptosis signals also participated in the regulation of ferroptosis, and apoptosis can be converted into ferroptosis under certain conditions [

26]. For example, the p53 protein facilitated cellular apoptosis through the direct activation of apoptosis-related genes, such as Bax. Concurrently, p53 downregulated the expression of SLC7A11, which impeded the synthesis of glutathione (GSH), subsequently inhibiting the activity of GPX4, ultimately leading to ferroptosis. Conversely, recent research has demonstrated that the deletion of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2 enhanced the expression of ACSL4 and PEBP1, thereby facilitating ferroptosis .

Autophagy may promote cell survival by degrading damaged organelles and proteins, or it can facilitate cell death under certain conditions [

27]. For instance, in the context of ferroptosis, autophagy has been shown to regulate the degradation of key proteins such as GPX4, which is essential for preventing lipid peroxidation, indicating that autophagy promoted ferroptosis under specific circumstances [

28]. Moreover, the interplay between autophagy and apoptosis is complex. Autophagy can influence the apoptotic process by modulating the levels of ROS and mitochondrial function [

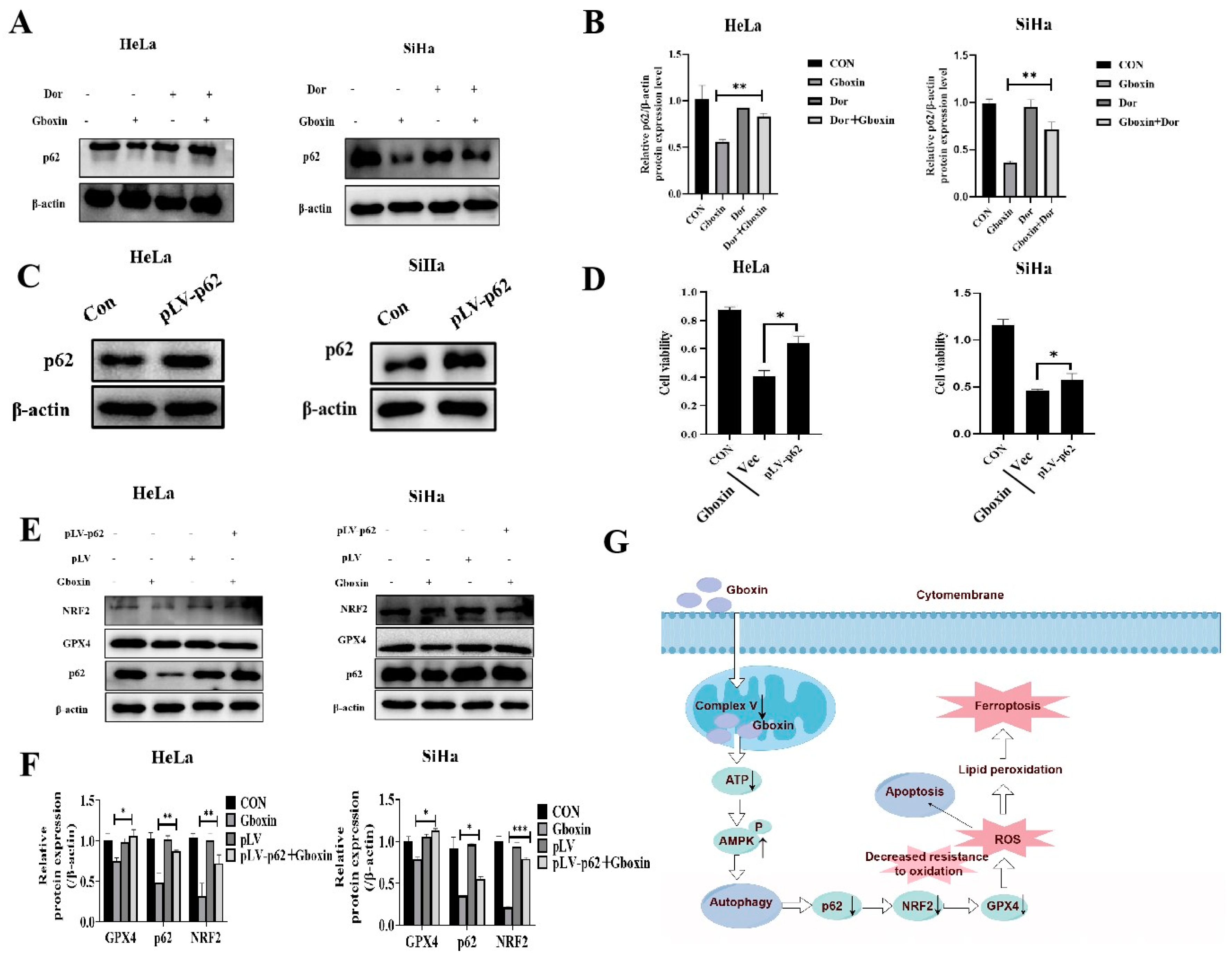

29]. Here, Gboxin was found to activate the AMPK signaling pathway and enhance autophagy through its interaction with mitochondrial complex V. The upregulation of AMPK activity subsequently facilitated autophagy and resulted in a reduction of p62 protein levels. The diminished p62 protein levels promoted the degradation of Nrf2 by modulating the p62-Keap1-Nrf2 axis, thereby reducing the antioxidant capacity and induced ferroptosis of cervical cancer cells.

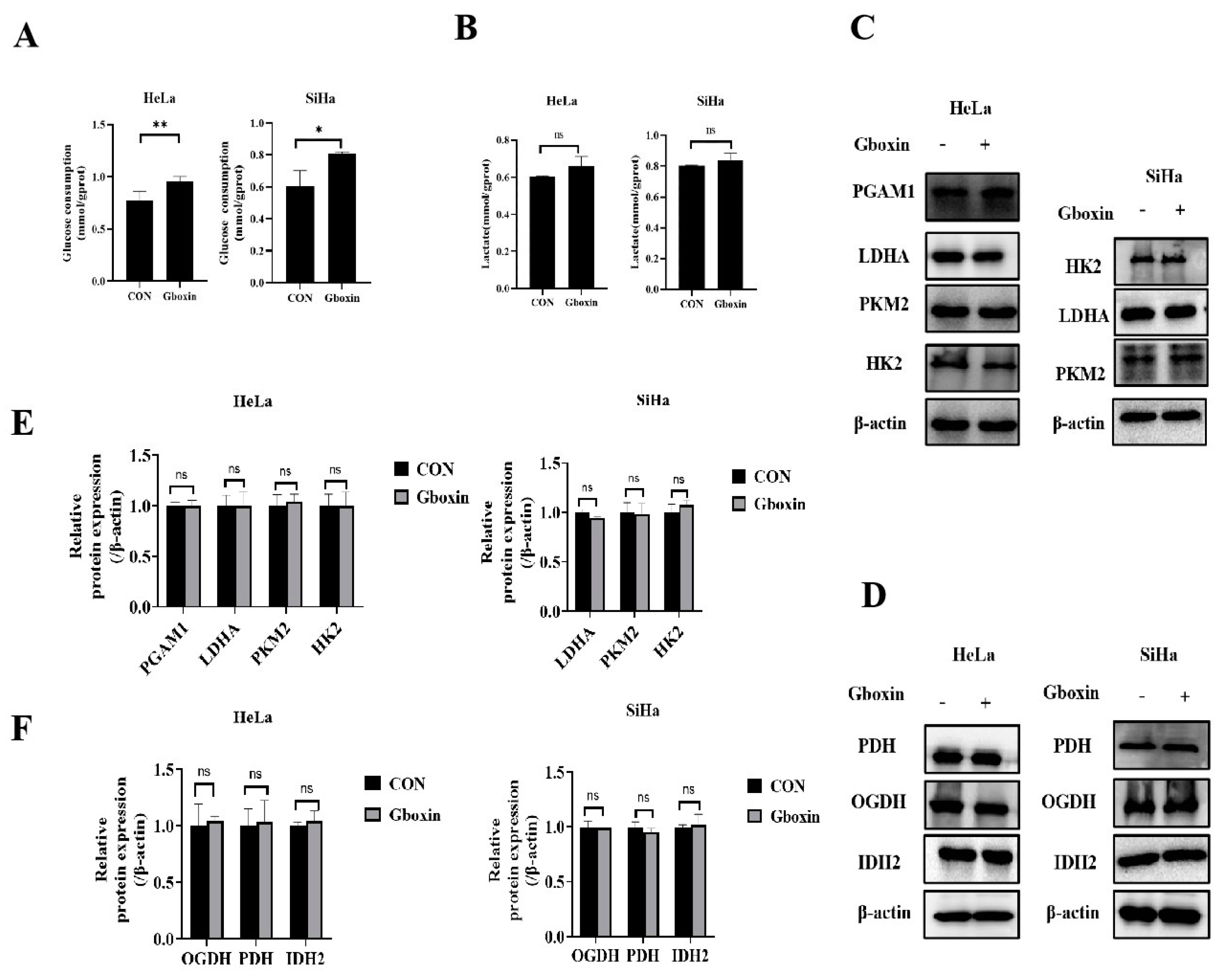

This study found that Gboxin promoted the glucose uptake of cells under low- glucose culture conditions. We hypothesize that inhibition of the mitochondrial OXPHOS by Gboxin led to an energy deficit, which compelled cells to increase glucose uptake to meet their energy requirements. It has been reported that inhibition of mitochondrial complexⅠ, Ⅲ, and Ⅴ promoted the glucose uptake of cancer cells [

30]. However, our investigation revealed no significant alterations in the expression of key glycolytic enzymes. This observation may be attributed to variations in the levels of other molecules, such as the GLUT1 transporter, or modifications in the epigenetic regulation of certain enzymes, potentially leading to enhanced enzymatic activity. Further research is required to elucidate these mechanisms.

The intricate network of mitochondrial functions not only supports energy production but also integrates various signaling pathways that are crucial for cellular homeostasis and survival. We found that Gboxin greatly reduced the mitochondrial membrane potential of cervical cancer cells under low-glucose conditions, thereby impairing mitochondrial function. The mitochondrial membrane potential serves as the driving force for ATP synthesis, and a diminished mitochondrial membrane potential can decrease the activity of the respiratory chain, potentially resulting in disruptions to energy metabolism. A large number of studies have shown that the decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential is related to autophagy, apoptosis, or ferroptosis, etc. [

31]. MPTP selectively allows small-molecule substances to penetrate under normal conditions, which helps to balance the Ca

2+concentration in mitochondria and reduce the generation of free radicals to maintain the physiological activities of cells. Continuous opening of the MPTP can result in mitochondrial swelling and rupture, ultimately initiating the process of cell death [

32]. Our findings indicate that under conditions of low glucose, the MPTP exhibits a high degree of opening in the Gboxin-treated group, potentially leading to impaired mitochondrial function and subsequently death of cervical cancer cells.

The findings from this study highlighted the potential of Gboxin as a novel therapeutic agent for cervical cancer, particularly in conditions of metabolic stress. Furthermore, the study underscored the importance of targeting Nrf2 signaling as an important strategy for cervical cancer treatment.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

HeLa, SiHa, and HEK-293T cell lines were procured from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Comprehensive identification and screening were conducted to ensure the absence of mycoplasma contamination. HeLa and SiHa cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (M30150; Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; FND500; ExCell). HEK-293T cells were cultured in H-DMEM medium (M22650; Corning) with an addition of 10% FBS. All culture media were further supplemented with 1% penicillin and 1% streptomycin (P1400; Solarbio, Beijing, China). All cells were maintained in an incubator at 37°C with a 5% CO2. Two distinct culture conditions were established: (1) normal culture conditions, utilizing RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, and (2) low-glucose culture conditions, employing L-DMEM medium (11966025; Gibco) containing 1 mM glucose, supplemented with 10% glucose-free dialyzed FBS (26400-036, Invitrogen). The low-glucose treatment protocol involved initially culturing the cells under normal conditions until a density of 70%-80% was achieved, at which point the original medium was discarded. Cells were then washed with PBS and cultured in the low-glucose cultured conditions and then placed in a constant temperature incubator at 5% CO2 with 37°C.

4.2. Cell Transfection

The plasmid pGreenPuro-p62 (2 µg) was co-transfected into HEK-293T cells together with packaging vectors psPAX2 (1.5 µg) and envelop plasmids pMD2.G (1 µg). 48 hours post-transfection, the viral supernatant was collected and filtered using a 0.45 µm filter. Subsequently, HeLa and SiHa cells were cultured with the viral supernatant at 37°C for 24 hours, after which the medium was replaced with fresh medium. Following an additional 24-hour incubation, the medium was substituted with fresh medium containing 2 µg/ml puromycin. The cells were maintained at 37°C for two weeks to establish stable cell lines.

4.3. Cell Protein Extraction and Western Blotting Analysis

Cells inoculated in 6-well plates were harvested for analysis. Following the removal of the culture medium and subsequent washing with PBS, the cells were lysed to facilitate protein extraction. Protein concentrations were quantified using the BCA Enhanced Protein Assay Kit (P0012; Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Subsequently, separation and stacking gels were prepared for electrophoresis, and proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Roche) using the wet transfer technique. The PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk and incubated with diluted primary antibodies at 4°C, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies at room temperature. The final immunoblot was visualized utilizing an ECL luminescent solution (Tanon, Shanghai, China). The ECL reagent was applied to the PVDF membrane and permitted to react for a duration of 1-2 minutes. The film exposure time ranged from 10 seconds to 1 minute, with adjustments made based on varying light intensities. β-actin (1:1000, 81115-1-RR, Proteintech) served as the loading control.

4.4. Trypan Blue Staining

The cells were harvested and seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1×104 cells per well, with three replicate wells established for each experimental group. Following cell adhesion, the medium for the low-glucose group was substituted with a low-glucose medium supplemented with Gboxin (T15373; Topsience, Shanghai, China). Subsequently, the medium was removed, and a 0.04% trypan blue staining solution was applied for 4 minutes. After discarding the staining solution and washing the cells with PBS, cell morphology was examined using electron microscopy.

4.5. MTT Assay

The cells were harvested and seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1×104 cells per well, with three replicate wells established for each experimental group. Following cell adhesion, the medium for the low-glucose group was substituted with a low-glucose medium supplemented with Gboxin. Subsequently, 20 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) was introduced into each well, and the cells were incubated for an additional 4 hours. The medium was then removed, and 100 µL of DMSO (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) was added to each well. MTT uptake was quantified according to the manufacturer's protocol.

4.6. Antibodies

Antibodies for western blotting were as follows: Anti-β-Actin antibody(1:1000, 20536-1-AP,Proteintech), Anti-Cleaved Caspase3 antibody(1:1000, 9661T, CST), Anti-Caspase3 antibody(1:1000, 19677-1-AP, Proteintech), Anti-Bax antibody(1:1000, 50599-2-Ig, Proteintech), Anti-Bcl2 antibody(1:1000, 12789-1-AP, Proteintech), Anti-LC3 antibody(1:1000, 4108S, CST), Anti-p62 antibody(1:1000, 18420-1-AP, Proteintech), Anti-Beclin1 antibody(1:1000, 11306-1-AP, Proteintech), Goat anti-Rabbit lgG(1:1000, 35401S, CST), Goat anti-Mouse lgG(1:1000,91996,CST), Anti-AIFM2/FSP1 antibody(1:1000, 20886-1-AP, Proteintech), Anti-GPX4 antibody(1:1000, 30388-1-AP, Proteintech), Anti-Nrf2 antibody(1:1000, ab137550, Abcam), Anti-Cox2 antibody(1:1000, 501253, Zenbio), Anti-Keap1antibody(1:1000, ab139729, Abcam), Anti-PDH antibody(1:1000, 18068-1-AP, Proteintech), Anti-IDH2 antibody(1:1000, 15932-1-AP, Proteintech), Anti-OGDH antibody(1:1000, 15212-1-AP, Proteintech), Anti-PGK1 antibody(1:1000, 17811-1-AP, Proteintech), Anti-PKM2 antibody(1:1000, 15822-1-AP, Proteintech), Anti-PFKM antibody(1:1000, 30326-1-AP, Proteintech), Anti-LDHA antibody(1:1000, 14824-1-AP, Proteintech).

4.7. Measurement of NADP+/NADPH Ratio

The cells were seeded into 6-well plates, and once adherence was achieved, the low-glucose group was treated with a low-glucose medium supplemented with Gboxin and incubated for 24 hours. Subsequently, the NADP+/NADPH ratio was determined using the NADP+/NADPH Assay Kit with WST-8 (S0179, Beyotime), following the manufacturer's instructions. All measurements were normalized to protein content.

4.8. Measurement of Lipid Peroxidation(LPO) and Malondialdehyde(MDA)

The cells were seeded into 6-well plates, and upon adherence, the medium for the low-glucose group was replaced with a low-glucose medium containing Gboxin, followed by a 24-hour incubation period. Lipid peroxide and malondialdehyde levels were quantified using the Lipid Peroxidation Assay Kit (A106-1-1) and the Cell Malondialdehyde (MDA) Assay Kit (A003-4-1), both procured from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. All measurements were normalized to protein concentrations.

4.9. Intracellular Fe2+ Assay

The cells were seeded into 6-well culture plates, and upon adherence, the low-glucose group was treated with a low-glucose medium supplemented with Gboxin and incubated for 24 hours. The Fe2⁺ content was subsequently measured using a tissue Fe2⁺ assay kit (A039-2-1; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) following the manufacturer's instructions. All measurements were normalized to protein concentrations.

4.10. Intracellular ROS Measurement

The cells were seeded into 6-well plates, and upon adherence, the medium for the low-glucose group was substituted with a low-glucose medium supplemented with Gboxin, followed by continuous culture for 24 hours. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 5 μM DCFH-DA (S0033M, Beyotime, China) for 30 minutes at 37°C. The cells were then collected and analyzed using flow cytometry for imaging.

4.11. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Detection

Primers for RT-PCR were designed utilizing Primer 5.0 gene primer design software, and all primers were synthesized by Genewiz Co., Ltd. The cells were seeded in 6-well plates, and upon cell adherence, the medium for the low-glucose group was replaced with a low-glucose medium supplemented with Gboxin, followed by continuous culture for 24 hours. Subsequently, the medium was discarded, and the cells were washed with PBS. Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), and complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were synthesized using an RT-PCR Kit (Takara Bio Inc., Dalian, China). The mRNA expression levels were quantified in triplicate utilizing the SYBR Green I dye method (Takara Bio Inc.). β-actin served as the reference gene. The RT-PCR reaction mixture comprised 2 ng of cDNA, 5 μL of SYBR Green I, 0.3 μL of forward primer (PCR-F-Primer), 0.3 μL of reverse primer (PCR-R-Primer), and 2.4 μL of RNase-free H2O, resulting in a total reaction volume of 10 μL. The final concentration of cDNA was 1000 ng/μL, and the final concentration of primers was 500 nmol/L. The RT-PCR protocol was executed under the following conditions: an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 5 minutes, succeeded by 40 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 5 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 5 seconds, and extension at 60°C for 30 seconds. Upon completion of the amplification process, a melting curve analysis was performed over the temperature range of 60-95°C. The reaction products were subsequently stored at 4°C. Data analysis was conducted utilizing the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Table 1.

Primers used for RT-PCR.

Table 1.

Primers used for RT-PCR.

| T |

Title 2 |

Title 3 |

| β-actin |

F-Primer |

CGTGCGTGACATTAAGGAGAAG |

| R-Primer |

GGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAGAGTG |

| p53 |

F-Primer |

CAGCACATGACGGAGGTTGT |

| R-Primer |

TCATCCAAATACTCCACACGC |

| ACSL4 |

F-Primer |

CATCCCTGGAGCAGATACTCT |

| R-Primer |

TCACTTAGGATTTCCCTGGTCC |

| NCOA4 |

F-Primer |

GAGGTGTAGTGATGCACGGAG |

| R-Primer |

GACGGCTTATGCAACTGTGAA |

| GPX4 |

F-Primer |

GAGGCAAGACCGAAGTAAACTAC |

| R-Primer |

CCGAACTGGTTACACGGGAA |

| FSP1 |

F-Primer |

AGACAGGGTTCGCCAAAAAGA |

| R-Primer |

CAGGTCTATCCCCACT ACTAGC |

| TFRC |

F-Primer |

ACCATTGTCATATACCCGGTTCA |

| R-Primer |

CAATAGCCCAAGTAGCCAATCAT |

| SLC7A11 |

F-Primer |

TCTCCAAAGGAGGTTACCTGC |

| R-Primer |

AGACTCCCCTCAGTAAAGTGAC |

| ND1 |

F-Primer |

CCCTAAAACCCGCCACATCT |

| R-Primer |

GAGCGATGGTGAGAGCTAAGGT |

| B2M |

F-Primer |

TGCTGTCTCCATGTTTGATGTATCT |

| R-Primer |

TCTCTGCTCCCCACCTCTAAGT |

4.12. Lactate Production Assay

The cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1×104 cells per well. Upon cell adherence, the medium for the low-glucose group was replaced with a low-glucose medium, and Gboxin was administered, with three replicate wells established for each group. Lactate content was quantified using a lactate assay kit (A019-2-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. All measurements were normalized to protein levels.

4.13. ATP Production Assay

The ATP levels were quantified using the ATP Assay Kit (S0026, Beyotime, China). Cells were seeded into 6-well plates, followed by replacement of the medium with a low-glucose medium supplemented with Gboxin, and cultured for 24 hours. Subsequently, cell lysis was performed using the lysis buffer provided in the kit at 4°C. The resulting lysate suspension was collected, diluted, and combined with 100 µL of ATP detection solution. ATP concentrations were measured using a CLARIOstar Microplate Reader (BMG LABTECH, Ortenberg, Germany), with quantification based on a standard curve generated from known ATP concentrations.

4.14. Glucose Consumption Assay

The supernatant from the cell cultures was collected and analyzed using a glucose assay kit (F006-1-1; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), following the manufacturer's instructions. After a 10-minute incubation at 37°C, the OD was measured using a Bio-Rad microplate reader. Glucose consumption was subsequently calculated, and all values were normalized to the protein concentrations.

4.15. Measurement of Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Complex V Activity

The cells were harvested, and the activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex V was assessed using a micro mitochondrial respiratory chain complex V activity assay kit (BC1445; Solarbio, Beijing, China), following the manufacturer's instructions. Absorbance at 660 nm was determined using a spectrophotometer (Thermo). All measurements were normalized to protein concentrations.

4.16. Membrane Potential Measurement

The cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1×104 cells per well. Following cell attachment, the medium for the low-glucose group was replaced with a low-glucose medium supplemented with Gboxin, and the cells were incubated for 24 hours. Subsequently, the medium was removed, and the cells were incubated with 2 mM TMRE (C2001S, Beyotime, China) for 30 minutes. The cells were then washed with PBS, and their fluorescence was observed and imaged using laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSM800, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

4.17. MPTP Assay

The cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1×104 cells per well. Following cell attachment, the medium for the low-glucose group was replaced with a low-glucose medium supplemented with Gboxin, and the cells were incubated for 24 hours. Subsequently, the cells were stained with Calcein AM (C1367S, Beyotime, China) for 30 minutes, washed with PBS, and then observed and imaged using laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSM800, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

4.18. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) Copy Number Detection

The cells were inoculated into 6-well cell plates, and after the cells were attached, the medium in the low-glucose group was replaced with low-glucose medium, and the cells were cultured for 24 hours. We used the Mammalian genomic DNA extraction kit (S0026, Beyotime, China) for DNA extraction, and the amount of mitochondria was determined from the mtDNA copy number. The relative quantity of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) compared to nuclear DNA was assessed through quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) employing primers specific to ND1 (mitochondrial genome) and B2M (nuclear genome). The levels of mtDNA were measured in triplicate utilizing the SYBR Green I dye method (Takara Bio Inc.). The relative mtDNA copy number was analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

4.19. Tumor Xenograft Studies

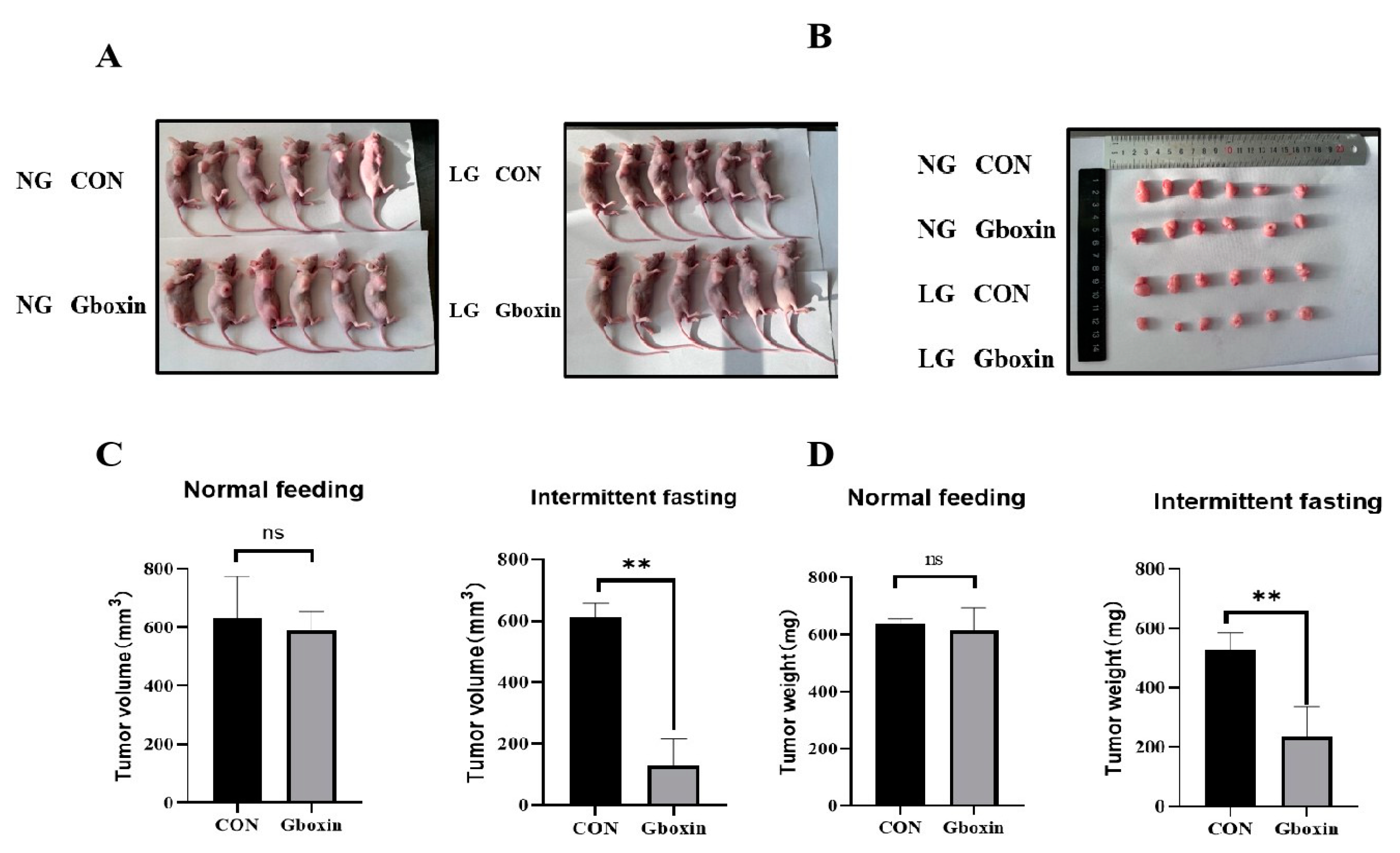

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (NENU/IACUC, AP20231225) at Northeast Normal University, China. Female BALB/c nude mice, aged 4 weeks, were procured from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology, Beijing, China. For the purpose of the study, the mice were randomly allocated into four distinct groups: (1) a normal feeding group, (2) a normal feeding group receiving Gboxin treatment at a dosage of 10 mg/kg, (3) an intermittent feeding group, and (4) an intermittent feeding group receiving Gboxin treatment. The feeding regimen for the intermittent feeding group was established as a 24-hour fasting-feeding cycle. During the fasting phase, food was completely removed while water remained freely accessible for 24 hours, after which food was replenished. HeLa cells were harvested and subcutaneously inoculated into the left dorsal region of nude mice. Ten days post-inoculation, the mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation, and the xenografts were excised and weighed. The volume of the xenografts was determined using vernier calipers and calculated using the formula: V = L × W2× 0.52, where L represents the length and W the width of the xenograft. The tumor volume and weight were quantified using a Vernier caliper and an electronic balance (Mettler Toledo), respectively.

4.20. Statistical Analysis

The data obtained from this experiment were analyzed and processed using GraphPad and Excel software, with results presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance between two groups was assessed using the Student's paired t-test, while one-way ANOVA was employed for comparisons involving more than two groups. Statistical significance was denoted by *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.