1. Introduction

The pivotal role of metabolic reprogramming in the onset and rapid recurrence of urothe lial carcinoma [

1,

2,

3] is affirmed by the genomics of resected tumor and by metabolomics of patient’s urine. The overexpression of genes driving glycolysis [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] and fatty acid metabolism in tumor [

6] predicted the urinary detection of 12-19 metabolites [

7] and glycogen depletion [

8] coupled with fatty acid accumulation in tumor cells shed into urine by patients, converse of the metabolomics for normal urothelial cells shed into the urine.

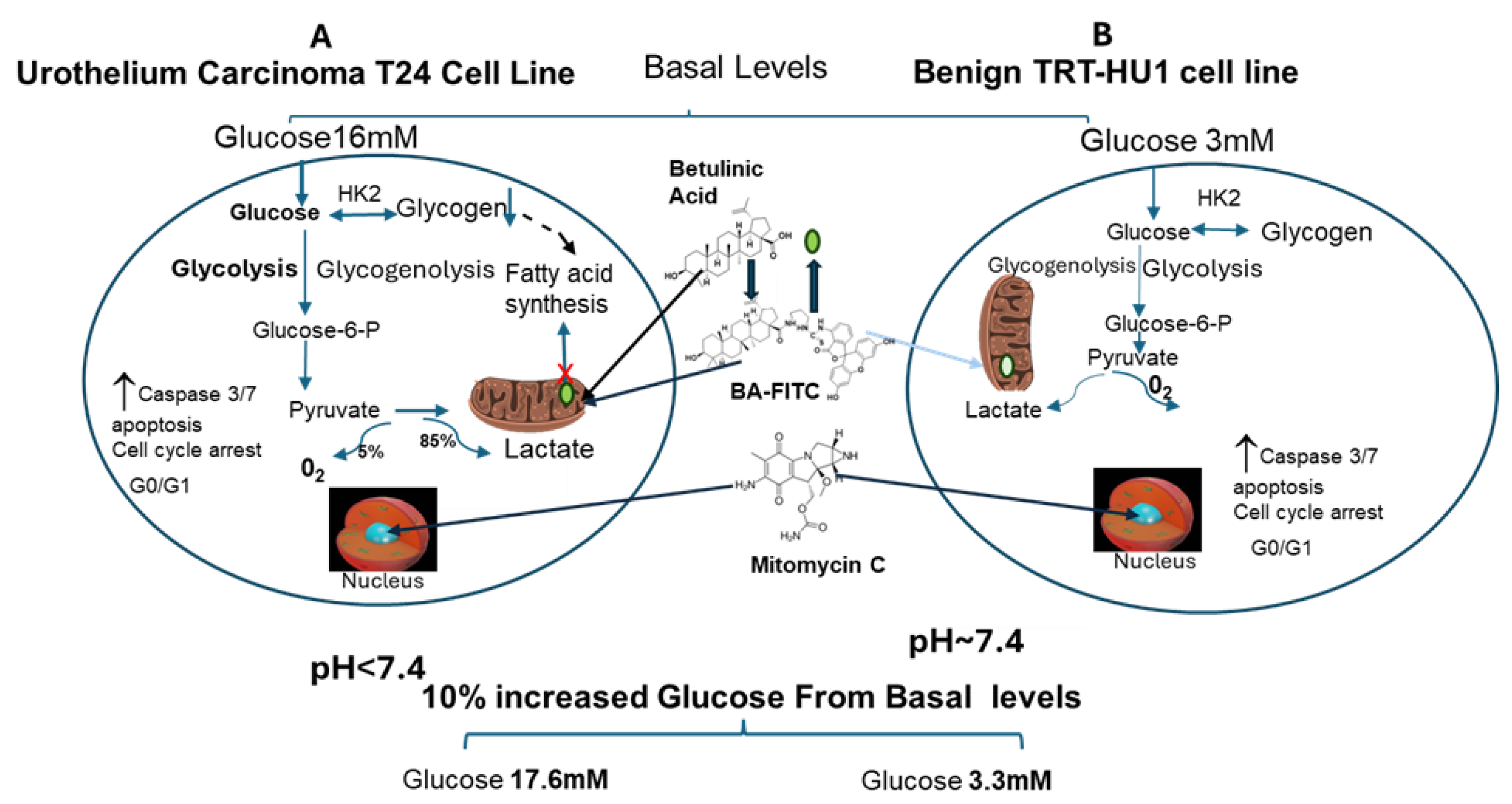

The multi-omics of resected tumors are attested by the dependence of two-fold faster proliferation [

9] of urothelial carcinoma cell line T24 relative to benign urothelial cell line TRT-HU1 on five-fold higher glucose levels of 16mM and 3mM in McCoy’s 5A media and Keratinocyte Serum Free media, respectively (basal) (

Figure 1). Here, we hypothesized that if rapid proliferation of urothelial carcinoma (T24) is fueled by fatty acid synthesis and oxidation, then a 10% increase in glucose from basal levels, would decrease the intracellular accumulation of the fatty acid mimetic, Betulinic Acid (BA) as well opposes the pharmacological effect of BA on proliferation, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. We arrived at the paradigm of 10% increase in glucose from basal levels to mimic the effect of hyperglycemia on lower sensitivity of antibody drug conjugates, Enfortumab vedotin in bladder cancer [

10] and higher risk of urothelial carcinoma in diabetic patients [

11,

12]. However, the confounding effect of hypertonic stress on cell viability[

13] discouraged any further increase in glucose above 10% from basal levels.

Past research highlighted the anticancer effect of BA at basal glucose levels via depolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] and induction of apoptosis via caspase dependent cell death and cell cycle arrest [

18,

19,

20,

21]. The anticancer activity of topical BA on horse melanoma [

22] even merited the registration of a pilot clinical study (NCT00346502). However, the role of metabolic reprogramming in the anticancer action of BA and in higher uptake of BA by cancer cells is not known. While prior research supports the premise of BA conjugates [

14] as a theragnostic, BA is also one of the many active ingredients [

23] in the anti-inflammatory Oleogel S-10 approved recently in Europe for the treatment of Dystrophic Epidermolysis bullosa [

24] and urothelial carcinoma is also amenable to topical treatment [

25].

To test our hypothesis, we chemically conjugated BA [

14] with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (

Figure S3-supplementary) for determining the confocal co-localization of BA-FITC with Mito-tracker Red labelled mitochondria in T24 and TRT-HU1 cell lines of human urothelium. We determined the cytotoxicity and safety of BA relative to the standard chemotherapeutic drug, Mitomycin C (MC) [

25] on T24 and TRT-HU1 cell lines grown in McCoy’s 5A media and Keratinocyte Serum Free media containing 16mM and 3mM glucose (basal), respectively and 10% increase from respective basal levels. We compared the effect of BA and MC on cell cycle arrest and caspase-3/7 mediated apoptosis and only investigated the glucose-sensitive BA by determining the effect of BA on gene expressions involved in apoptosis [

15,

16,

18,

19,

20], glycolysis, glycogenolysis [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

8] and pH decline amidst glucose scarcity [

26] (

Figure 1).

3. Discussion

A pivotal role of metabolic reprogramming in carcinogenesis [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] is substantiated by the significant decrease in the doubling time of T24 cells growing at 10% increase in glucose from the basal level of 16mM in commercially available McCoy’s 5A media. The glucose sensitive localization of BA-FITC, a fatty acid mimetic, in the mitochondria of T24 cells corroborates fatty acid accumulation [

8,

27,

28] in cancer cells shed into urine by urothelial carcinoma patients. Moreover, the fatty acid accumulation coupled with glycogen depletion in cancer cells aligns with the aberrant expression of glycolysis genes in resected tumors aligns with urine metabolomics [

7]. Higher lethality of BA-FITC than of BA on T24 cells mirrors the past results of BA conjugated bis-arylidene oxindole [

14] and underlies that BA conjugation increases the lethality of polar dyes FITC, towards cancer cells compared to BA alone.

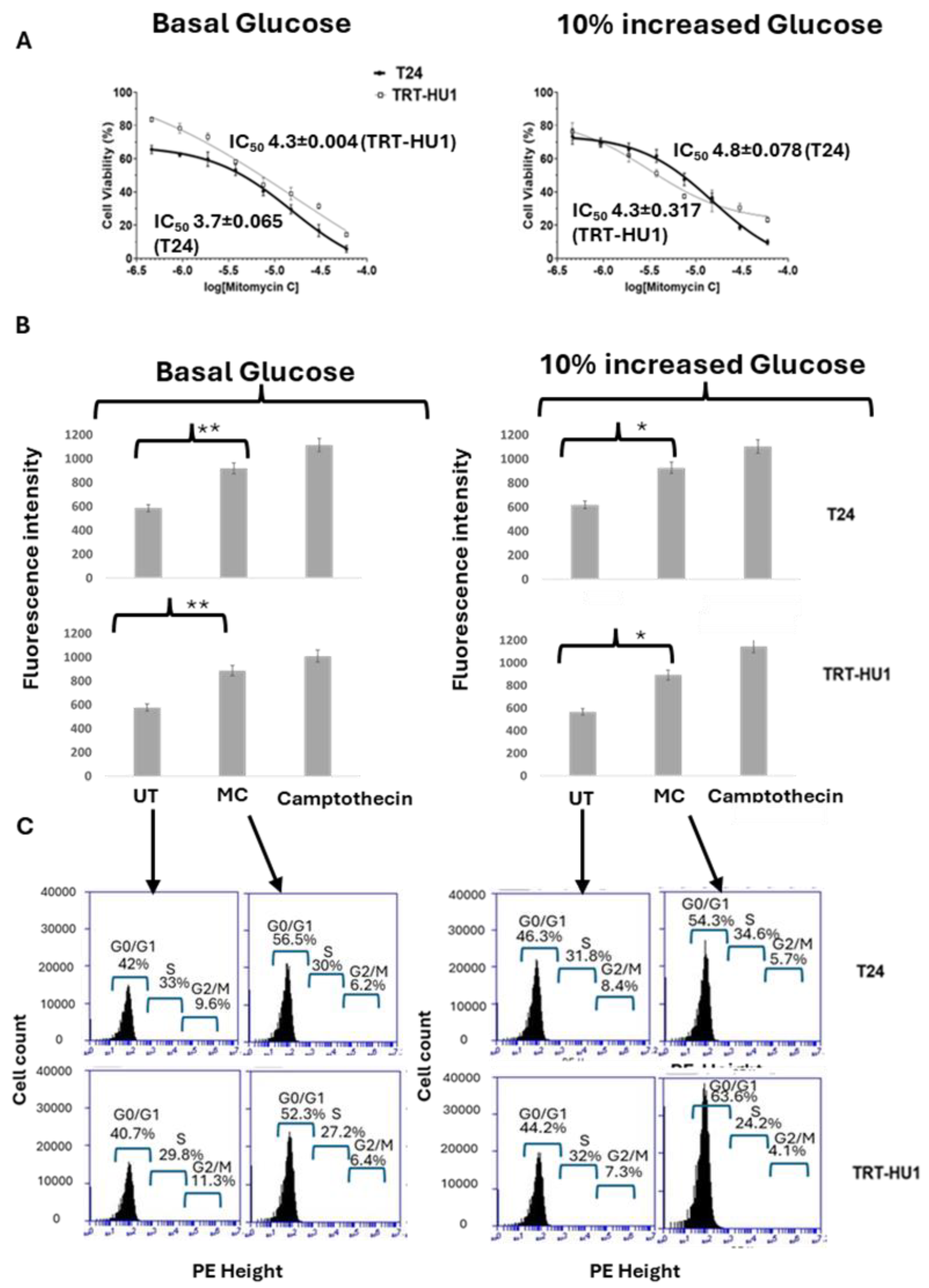

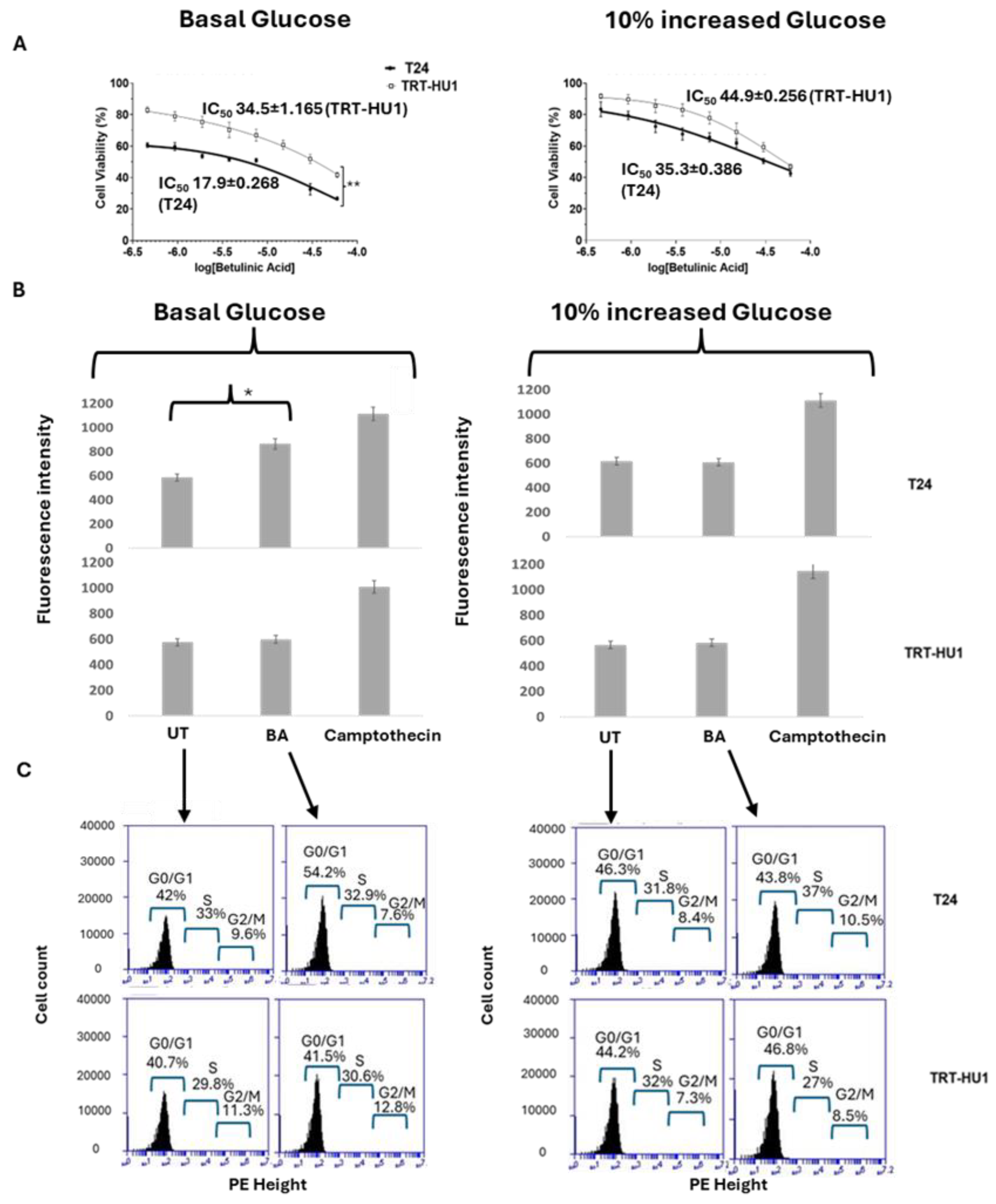

Unlike glucose insensitive intercalation of MC with nuclear DNA [

29], we found that the glucose sensitive mitochondrial localization of BA is deterministic in BA evoked cell cycle arrest and caspase-3/7 mediated apoptosis [

15,

18,

23]. We analyzed the effect of MC and BA on cell cycle after cell synchronization via double thymidine block, which arrests the cells at G1 phase. Upon release of thymidine block, the G0/G1 phase lasts 9-10 h, nearly the midpoint of the doubling time of 18 h for T24 cells. The caveats of doubling time and cell synchronization are relevant in interpreting BA evoked cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase as opposed to arrest in S or G2/M phase [

20] seen in other cancer cell lines hallmarked by different doubling times. As opposed to the arrest of nearly an identical percentage of T24 and TRT-HU1 cells by MC at basal and at 10% increased glucose, BA arrested a higher percentage of T24 cells grown at basal glucose than TRT-HUI cells in G0/G1 phase.

While the mechanism of action and gene expression involved in the anticancer effect of MC is well known, the same is not the case for BA. Therefore, we probed whether BA selectively targets metabolic reprogramming of urothelial carcinoma in causing minimal harm to normal urothelial cells, TRT-HU1 [

16]. T24 cells grown at 10% increased glucose not only successfully resisted the mitochondrial localization of FITC conjugated BA but also reversed the BA induced gene expression [

19]. A lower mitochondrial localization of BA-FITC in T24 grown at 17.6mM glucose resulted in two-fold higher IC50 than the IC50 of BA-FITC measured in T24 cells grown at 16mM glucose. The glucose sensitive localization of BA-FITC in mitochondria of T24 cells is consistent with the past reports on BA depolarizing the mitochondrial potential of cancer cells, and inhibiting topoisomerase 1B, involved in mitochondrial translation and carcinogenesis [

20].

T24 cells grown at 17.6mM glucose, mere 10% higher than basal level of 16mM recapitulated the glycogen depletion [

8] noted in tumor cells isolated from urine of patients, likely resulting from glycogenolysis for fatty acid synthesis, decreased glycogenesis [

30] and oxidative phosphorylation [

26]. To assess the effect of BA on glycogen and pH decline amidst glucose scarcity, we replaced the buffered growth media containing 16mM or 17.6mM glucose with unbuffered isotonic solution at pH 7.4 after cells had reached their log growth phase in 8h. The absence of the buffering effect from the bicarbonate buffer in the isotonic solution enables detection of pH decline ensuing from rapid proliferation amidst glucose scarcity. BA evoked cell cycle arrest [

18,

31,

32,

33] in 54.2% of T24 cell grown at basal glucose sheds light on slower decline in pH and glycogen content amidst glucose scarce conditions for 3h [

34]. Thus, innately faster proliferation of T24 cells at basal glucose levels of 16mM is fueled by “Warburg effect” [

26,

27,

35] hallmarked by glycogenolysis [

30], accelerated glycolysis, faster formation of pyruvate [

27], and lactate conversion [

27,

28], which lowers pH of the extracellular space [

36]. Hence, we expected rapid proliferation of T24 cells amidst glucose scarcity to enhance lactic acid production, raise assembly and export of acid equivalents into extracellular space [

36]. Importantly, the rationale for tumor detection by pH-sensitive Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) probes [

37,

38] and by pH-sensitive fluorescent probes is dependent on acidic pH of cancer cells due to lactate production.

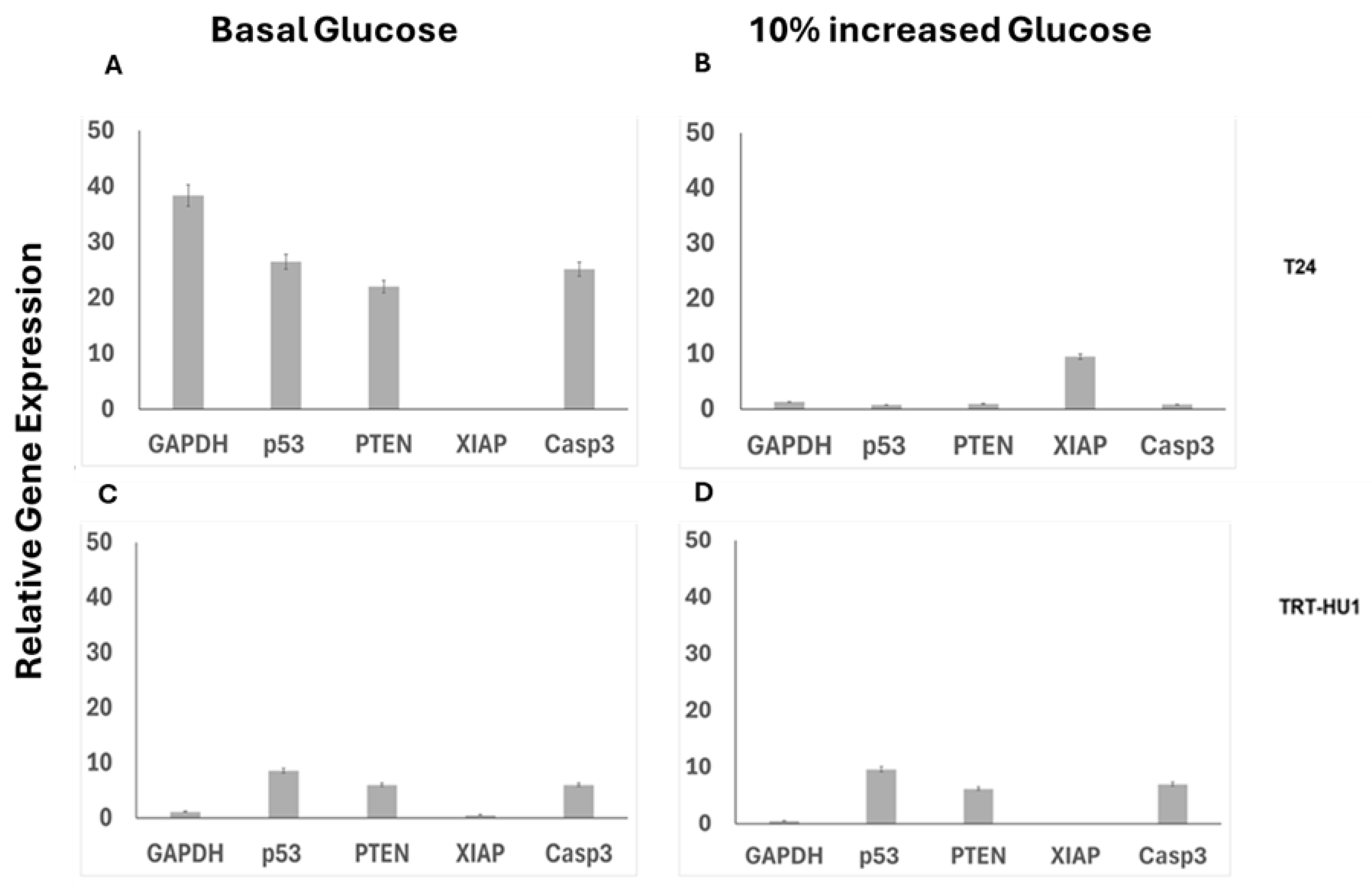

Based on our findings, we reason that cancer cells internalizing Betulinic acid, a fatty acid mimetic, is likely to inhibit enzymes involved in

de novo synthesis of fatty acids by pentose phosphate pathway amidst glucose scarcity, which warrants further investigation in future studies. Accordingly, we inferred that lower IC50 of BA as well as BA-FITC in T24 cells [

16] grown at basal glucose is dependent on the glucose scarcity dependent upregulation of pro-apoptotic genes:

Caspase 3, p53, PTEN and the downregulation of anti- apoptotic

XIAP [

39] gene along with metabolic marker

GAPDH. The caspase 3/7 apoptotic assay substantiated 10% increase in glucose reverses the

Caspase 3 upregulation induced by BA at basal levels.

A faster proliferation of T24 cells with 10% increase from basal glucose also corroborates the higher risk of urothelial carcinoma in diabetic patients[

11,

12] and the arrest of carcinogenesis with drugs that inhibits glycolysis [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. A dramatic rise in IC50 of BA and BA-FITC on T24 cells grown at 17.6mM glucose mimics the lower sensitivity of diabetic bladder cancer patients to antibody drug conjugates, Enfortumab vedotin [

10], which was ascribed to the lactate overproduction in presence of hyperglycemia. We could also draw an intriguing parallel between the decline in the mitochondrial localization of FITC tagged BA in T24 cells grown at 10% increased glucose and reduced tumor uptake of 2- Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-FDG) in PET scan performed without lowering the blood glucose levels [

40]. We posit that any potential impairment of BA action by hyperglycemia can be averted by combining BA with newer Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists [

41]. Likewise, the influence of hyperglycemia in PET scan of diabetic cancer patients [

42] can be mitigated by the acceleration of glucosuria [

43] with the use of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2(SGLT-2) inhibitors which may incur hypoglycemia risk and retrospective studies on diabetic bladder cancer patients treated with SGLT-2 inhibitors [

44] can answer whether the high risk of urothelial carcinoma in diabetic patients stems from hyperglycemia or glucosuria. Interestingly, BA induced GAPDH upregulation in T24 cancer cells [

9] may offer a potential alternative mechanism for raising FDG uptake into tumor without triggering the hypoglycemia risk [

40]. Overall, our findings demonstrate that the anticancer action of BA is dependent on metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

Betulinic Acid (Catalog no. B8936; 456.7 Daltons), Mitomycin C (Catalog no. M4287; 334.3 Daltons) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Catalog no. 46950; 389.38 Daltons) were procured from Sigma Aldrich whereas Mito-tracker red (Catalog no. M22425) was procured from Invitrogen. The conjugation of Betulinic acid with FITC was confirmed by the rise in molecular weight (supplementary data). TRT-HU1 (Catalog no. CVCL_M720) and Keratinocyte Serum Free media (Catalog no.10724011) were procured from Cellosaurus and Gibco, respectively whereas T24 (Catalog no. HTB-4) and McCoy’s 5A media (Catalog no.16600082) were purchased from ATCC and Gibco, respectively. Thymidine (Catalog no. T1895) and Propidium Iodide (Catalog no. 81845) for cell synchronization in cell cycle analysis were procured from Sigma-Aldrich. Caspase3/7 assay kit (Catalog no. C10430) was procured from Invitrogen.

4.2. Cell Culture

Urothelial carcinoma T24 cells and non-cancerous human urothelial TRT-HU1 were grown in respective media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37˚C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. TRT-HU1- KSFM Medium was supplemented with Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) and Bovine Pituitary Extract (Invitrogen). Cells were used within 5 passages after initial thawing. Basal and 10% increased glucose levels in media for T24 cells were 16mM and 17.6mM, respectively whereas basal and 10% increased glucose for TRT-HU1 were 3mM and 3.3mM, respectively. Doubling time was measured after first two passages using the formula, [ T × (ln2)] / [ ln (Xe / Xb)], where T = Time in hrs., Xe is number of cells at the end and Xb is the number of cells in the beginning. Hemocytometer was used for cell counting.

4.3. Cell Viability Assay (MTT)

After two passages, 5,000 cells (T24 and TRT-HU1) were plated in each well of 96 well plates and incubated overnight before 18h exposure to increasing concentrations of BA or MC and concentration reducing cell viability by 50%, (IC50) was determined by plotting MTT assay readings taken at 570nm using TECAN Spark 20M spectrophotometer.

4.4. Cell Cycle Analysis After Cell Synchronization by Double Thymidine Block

T24 and TRT-HU1 cells were grown in T25 flasks in basal and at 10% increased glucose from basal until confluency. Both the cell lines were sub-cultured in 1:3 flasks and incubated overnight at 37ºC and then subjected to double thymidine (2mM) block for 18 h each. After first block, cells were washed with 1x PBS after removing thymidine and then allowed to grow for 9h on fresh pre warmed media (basal and 10% increased) before the second thymidine block for 18 h. After again removing thymidine, cells were treated at respective IC50 of BA (20µM) and MC (4µM) for 12 h and analyzed by propidium iodide method using BD Accuri C6 plus flow cytometer, BD, USA.

4.5. Caspase 3/7 Apoptotic Assay

Cells were plated as described in MTT assay. Cells were then either left untreated or treated with BA (20µM), and MC (4µM) for 12 h using camptothecin (5µM) as positive control. Caspase 3/7 assay was performed according to manufacturer’s protocol and the fluorescence intensity was measured at excitation/emission wavelength of 590/610 nm.

4.6. Quantitative PCR

Untreated T24 and TRT-HU1 cells or cells treated with BA (20µM) for 12 h were washed with 1X PBS before lysing with 1 ml Trizol (Invitrogen) for total RNA extraction, as per manufacturer’s instructions. RNA purity and concentration was determined using nanodrop 2000 (Thermofisher Scientific, USA). cDNA was created using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit from Applied Biosystems (now Invitrogen) with 1 μg of total RNA. PCR was performed with a HotStarTaq Master Mix Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, U) using sequence specific primers for the Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH), Caspase 3, p53, Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog deleted on Chromosome 10 (PTEN) and, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), designed in-house using previously published sequences (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, USA) on online primer design tool of Primer3;

http://biotools.umassmed.edu/bioapps/primer3_www.cgi). The primers were: GAPDH, Caspase 3 (NM_004346.4) L: 5’-ACTGGACTGTGGCATTGAGA -3’; R: 5’-GCACAAAGCGACTGGATGAA-3’, p53 L: 5’- TGGCCATCTACAAGCAGTCA-3’; R: 5’-GGTACAGTCAGAGCCAACCT-3’, PTEN (NM_000314.8) L: 5’-ACCGGCAGCATCAAATGTTT-3’; R: 5’-AGTTCCACCCCTTCCATCTG-3’, XIAP (NM_001167.4) L: 5’- TGCTCACCTAACCCCAAGAG-3’; R: TCCGGCCCAAAACAAAGAAG-3’. Quantitative PCR (CFX Connect Real Time system, BIORAD, USA) was performed as per manufacturer’s instructions.

4.7. Confocal Microscopy

Pre heated 18mm coverslips (Warner’s instruments) were placed in each well of 6-well plates before plating 1.2x106 cells/well and allowed to grow overnight before 2h exposure to media with or without 20 µM BA-FITC. Cells were then washed with 1X PBS before 15 min treatment with 25nM Mito tracker Red (Invitrogen). The cells were again washed with 1X PBS before mounting coverslips on slides under Confocal Microscope (Olympus Fluoview FV1000). Z-stack images were taken at 60x magnification with Laser HV454v, 2x Gain and 13% offset.

4.8. Glycogen and pH Assay

5,000 T24 and TRT-HU1 cells were plated in each well of 96 well plates and allowed to grow for 8h in respective growth media with basal or 10% increased glucose, with and without BA treatment at 37ºC and 5% CO2. Media was subsequently replaced with unbuffered, isotonic solution of pH 7.4 to create glucose scarcity for glycogen assay by fluorometric Glycogen assay kit ab65620, Abcam, as per manufacturer’s instructions using glycogen standard and excitation/emission of 535/587nm at 30, 60 and 120 mins, respectively. Cell proliferation amidst scarcity determined the rate of lactic acid production and pH decline from initial pH of 7.4, which was measured by Accumet 950 pH/ion meter (Thermofisher Scientific, USA) at 0,30,60,120 and 180 mins.

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Time dependent decline in glycogen and pH of cell lines relative to isotonic solution of pH 7.4 was plotted and significance analyzed by two-way ANOVA using Graph pad Prism version 10 software. Pearson’s coefficient was determined for colocalization, and significant difference assessed by student’s t-test. Results were considered significant at p<0.05.

Author Contributions

CRediT authorship contribution statement Anirban Ganguly: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Keara Healy: Cell culture, Media preparation Stephanie Daugherty: Software, Methodology Aratrika Halder: Preparation of BA-FITC conjugate, Chemistry methodology Shingo Kimura: Cell culture Rajkumar Banerjee: Intellectual input regarding chemistry methodology Jonathan Beckel: Intellectual inputs, Review & editing and primer design, Funding Acquisition Pradeep Tyagi: Intellectual inputs, Review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition

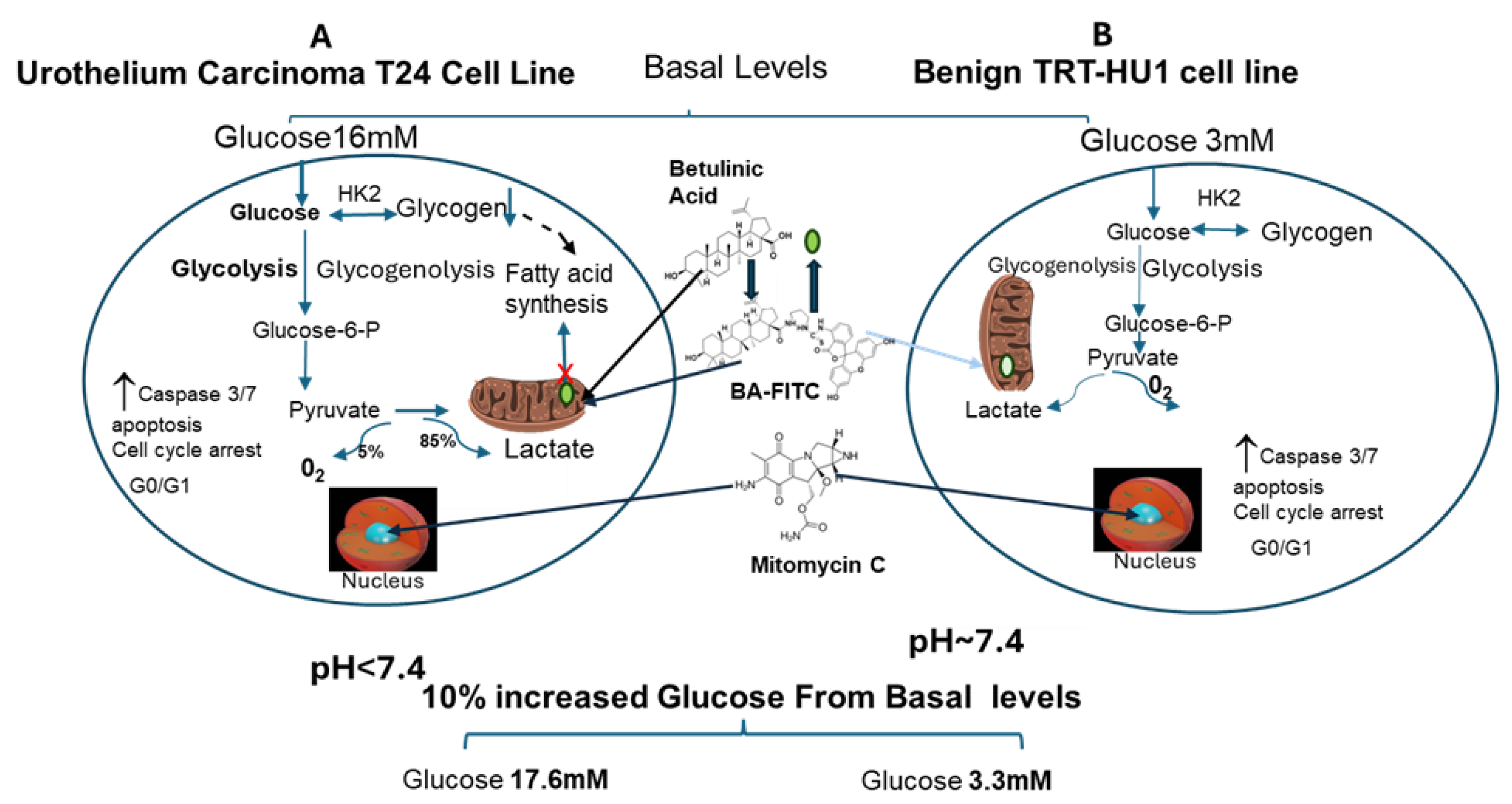

Figure 1.

Two-fold faster proliferation of urothelial carcinoma (T24) cell line relative to benign urothelial cells (TRT-HU1) is fueled by “Warburg effect”, which is sustained >5fold higher 16mM glucose in McCoy’s 5a medium (panel A) of relative to 3mM glucose in Keratinocyte Serum Free media for TRT-HU1(panel B). A 10% increase from basal levels to 17.6mM and 3.3mM for T24 and TRT-HU1 cell lines shortens the doubling time by 3h and 1h, respectively, and lowers confocal co-localization of natural fatty acid mimetic, Betulinic Acid (BA-FITC) with Mito-tracker red (mitochondrial marker) which coincides with slower decline of glycogen stores and of pH amidst glucose scarcity. Findings highlight that BA does not mimic nuclear DNA binding of mitomycin (MC) to evoke non-selective, glucose-insensitive cell cycle arrest and caspase-3/7 apoptosis of T24 and TRT-HU1 cells. (HK2- hexokinase 2). Because faster proliferation of T24 cells amidst glucose scarcity is fueled by mitochondrial accumulation of fatty acids, hallmarked by faster glycogen depletion and lactic acid production (pH decline), mitochondrial accumulation of a fatty acid mimetic (BA) inhibits fatty acids synthesis from glycogen, as indexed by slower glycogen decline amidst glucose scarcity. A mere 10% increase in glucose to 17.6mM from basal level of 16mM for T24 doubled IC50 of BA and BA-FITC relative to TRT-HU1 by reversing the upregulation of caspase 3, p53, PTEN, GAPDH and XIAP gene expression induced by BA in T24 at basal glucose (16mM).

Figure 1.

Two-fold faster proliferation of urothelial carcinoma (T24) cell line relative to benign urothelial cells (TRT-HU1) is fueled by “Warburg effect”, which is sustained >5fold higher 16mM glucose in McCoy’s 5a medium (panel A) of relative to 3mM glucose in Keratinocyte Serum Free media for TRT-HU1(panel B). A 10% increase from basal levels to 17.6mM and 3.3mM for T24 and TRT-HU1 cell lines shortens the doubling time by 3h and 1h, respectively, and lowers confocal co-localization of natural fatty acid mimetic, Betulinic Acid (BA-FITC) with Mito-tracker red (mitochondrial marker) which coincides with slower decline of glycogen stores and of pH amidst glucose scarcity. Findings highlight that BA does not mimic nuclear DNA binding of mitomycin (MC) to evoke non-selective, glucose-insensitive cell cycle arrest and caspase-3/7 apoptosis of T24 and TRT-HU1 cells. (HK2- hexokinase 2). Because faster proliferation of T24 cells amidst glucose scarcity is fueled by mitochondrial accumulation of fatty acids, hallmarked by faster glycogen depletion and lactic acid production (pH decline), mitochondrial accumulation of a fatty acid mimetic (BA) inhibits fatty acids synthesis from glycogen, as indexed by slower glycogen decline amidst glucose scarcity. A mere 10% increase in glucose to 17.6mM from basal level of 16mM for T24 doubled IC50 of BA and BA-FITC relative to TRT-HU1 by reversing the upregulation of caspase 3, p53, PTEN, GAPDH and XIAP gene expression induced by BA in T24 at basal glucose (16mM).

Figure 2.

Standard chemotherapeutic drug, Mitomycin C (MC), exhibited non-selective cytotoxicity on carcinoma cell line T24 and benign urothelial cell TRT-HU1 at basal (panel A) as well as at 10 % increased glucose from basal levels. The glucose-insensitive IC50 of MC determined after 18h exposure to MC is mirrored by caspase3/7 apoptotic activity (panel B) at basal (p value ≤0.01) and at 10% increased glucose (p value ≤0.05) and cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase determined after 12h exposure to MC (panel C). .

Figure 2.

Standard chemotherapeutic drug, Mitomycin C (MC), exhibited non-selective cytotoxicity on carcinoma cell line T24 and benign urothelial cell TRT-HU1 at basal (panel A) as well as at 10 % increased glucose from basal levels. The glucose-insensitive IC50 of MC determined after 18h exposure to MC is mirrored by caspase3/7 apoptotic activity (panel B) at basal (p value ≤0.01) and at 10% increased glucose (p value ≤0.05) and cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase determined after 12h exposure to MC (panel C). .

Figure 3.

Betulinic Acid (BA) exhibited significantly lower IC50 in T24 compared to TRT-HU1 grown at basal glucose (p value ≤0.01, panel A) and the IC50 difference was abolished by 10% increase in glucose from basal levels, which mirrored the results of Caspase 3/7 apoptotic assay (p value ≤0.05; panel B). The doubling of BA IC50 with 10% increase in glucose in T24 cells was determined by significantly lower apoptosis and lower cell cycle arrest as opposed to 13% higher cell cycle arrest (41.5% vs 54.2%) in G0/G1 phase of T24 cells grown at basal glucose (panel C). IC50 was determined by concentration dependent antiproliferative action of BA after 18h exposure and cell cycle arrest and apoptosis were determined after 12h exposure and Camptothecin was used as positive control in Caspase 3/7 apoptotic assay.

Figure 3.

Betulinic Acid (BA) exhibited significantly lower IC50 in T24 compared to TRT-HU1 grown at basal glucose (p value ≤0.01, panel A) and the IC50 difference was abolished by 10% increase in glucose from basal levels, which mirrored the results of Caspase 3/7 apoptotic assay (p value ≤0.05; panel B). The doubling of BA IC50 with 10% increase in glucose in T24 cells was determined by significantly lower apoptosis and lower cell cycle arrest as opposed to 13% higher cell cycle arrest (41.5% vs 54.2%) in G0/G1 phase of T24 cells grown at basal glucose (panel C). IC50 was determined by concentration dependent antiproliferative action of BA after 18h exposure and cell cycle arrest and apoptosis were determined after 12h exposure and Camptothecin was used as positive control in Caspase 3/7 apoptotic assay.

Figure 4.

Lower IC50 of BA in T24 cells grown at basal glucose (panel A) is dependent on BA induced up-regulation of pro-apoptotic genes: Caspase 3(Casp3) (p value ≤0.01), p53(p value ≤0.01), PTEN (p value ≤0.01) and GAPDH (p value ≤0.001) and the downregulation of XIAP gene (p value ≤0.05). While 10% increase in glucose (panel B) from basal levels reversed BA induced upregulation of p53, Casp3 in T24 cells, TRT-HU1 cells were resistant to any BA evoked gene alterations with or without increase in glucose (panels C-D). Gene expression was calculated relative to untreated controls at basal and 10 % increased glucose using 18s as a housekeeping gene.

Figure 4.

Lower IC50 of BA in T24 cells grown at basal glucose (panel A) is dependent on BA induced up-regulation of pro-apoptotic genes: Caspase 3(Casp3) (p value ≤0.01), p53(p value ≤0.01), PTEN (p value ≤0.01) and GAPDH (p value ≤0.001) and the downregulation of XIAP gene (p value ≤0.05). While 10% increase in glucose (panel B) from basal levels reversed BA induced upregulation of p53, Casp3 in T24 cells, TRT-HU1 cells were resistant to any BA evoked gene alterations with or without increase in glucose (panels C-D). Gene expression was calculated relative to untreated controls at basal and 10 % increased glucose using 18s as a housekeeping gene.

Figure 5.

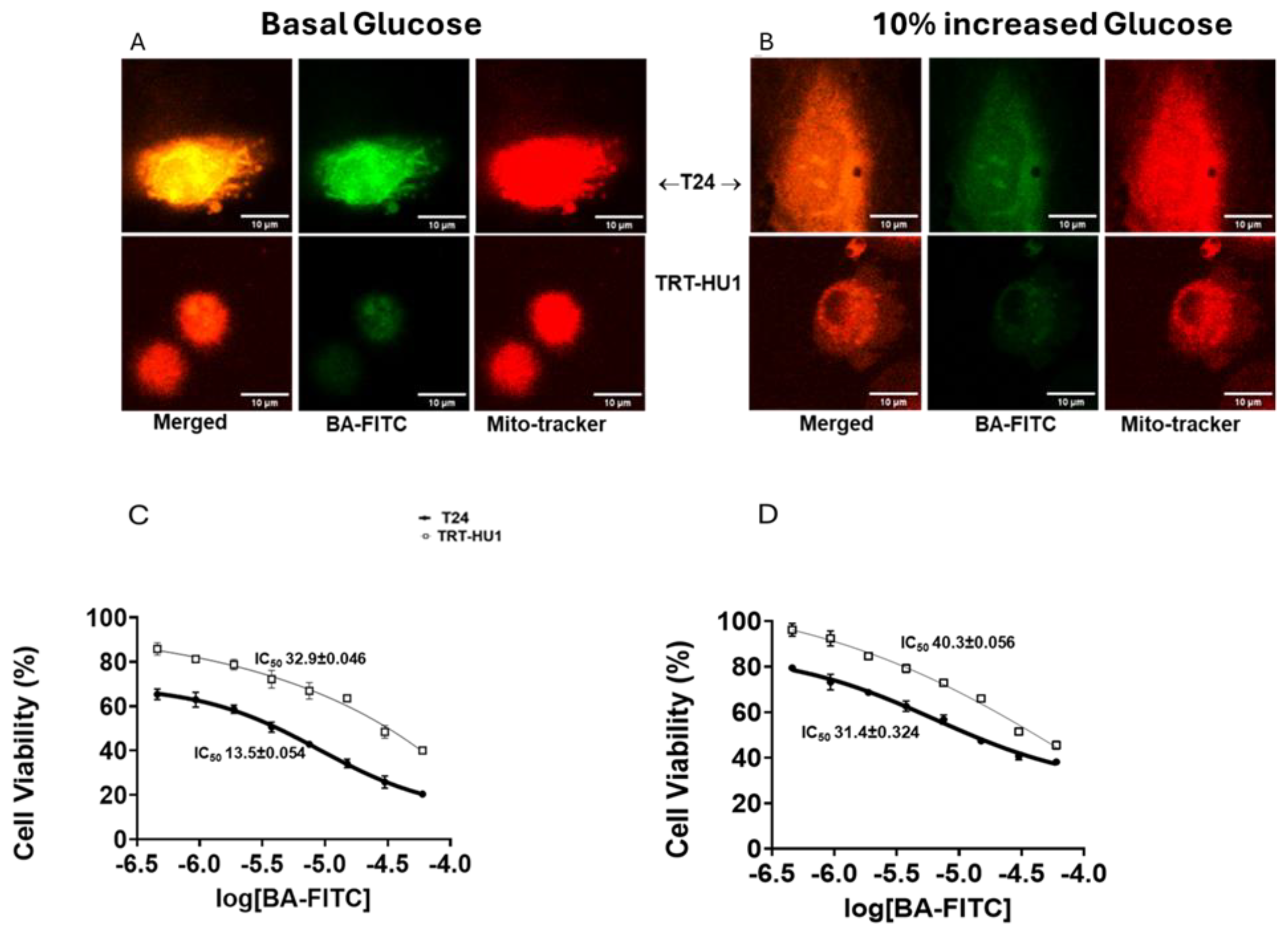

Glucose scarcity dependent colocalization of the green fluorescence emitted by FITC conjugated to Betulinic acid (BA-FITC; 20µM for 2h) with the red fluorescence emitted by Mito-tracker red in T24 cells (A) is evident from a ~15% decline in Pearson’s correlation coefficient from 0.91 to 0.75 (graph shown in supplementary data) for the colocalization of fluorescence at basal glucose (A) and 10% increased glucose (B), respectively, p value ≤0.01. The coefficient for colocalization, 0.66 and 0.63 in TRT-HU1 benign urothelial cells remained unchanged with 10% increase in glucose from basal levels. Lower mitochondrial localization of BA-FITC in T24 at higher glucose resulted in two- fold higher IC50 of BA-FITC (D) relative to IC50 of BA-FITC at basal glucose(C). .

Figure 5.

Glucose scarcity dependent colocalization of the green fluorescence emitted by FITC conjugated to Betulinic acid (BA-FITC; 20µM for 2h) with the red fluorescence emitted by Mito-tracker red in T24 cells (A) is evident from a ~15% decline in Pearson’s correlation coefficient from 0.91 to 0.75 (graph shown in supplementary data) for the colocalization of fluorescence at basal glucose (A) and 10% increased glucose (B), respectively, p value ≤0.01. The coefficient for colocalization, 0.66 and 0.63 in TRT-HU1 benign urothelial cells remained unchanged with 10% increase in glucose from basal levels. Lower mitochondrial localization of BA-FITC in T24 at higher glucose resulted in two- fold higher IC50 of BA-FITC (D) relative to IC50 of BA-FITC at basal glucose(C). .

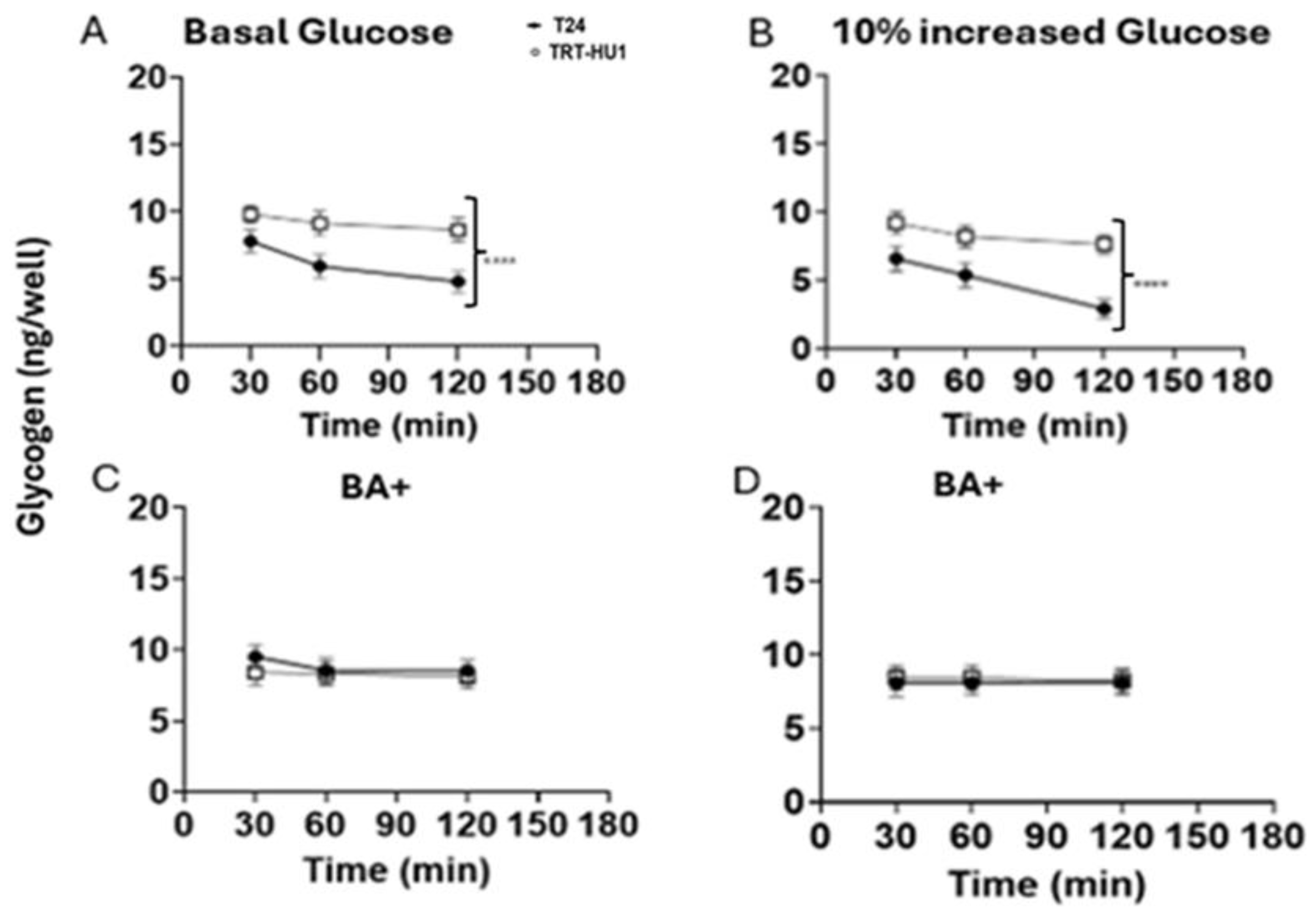

Figure 6.

Brief glucose scarcity was evoked by replacing growth media containing basal or basal+10% increased glucose with unbuffered isotonic solution of pH 7.4. Innately faster proliferation of T24 cell line [ ] than TRT-HUI cells [ ] at basal and basal +10% increased glucose resulted in steeper glycogen depletion (panel A-B) at 60- and 120-min (***p value <0.0001) whereas fatty acid mimetic (BA) slowed glycogen depletion by inhibiting the conversion of glycogen stores into fatty acids at basal (panel C) and at basal+10% increased glucose (panel D). BA evoked cell cycle arrest also slowed proliferation amidst glucose scarcity.

Figure 6.

Brief glucose scarcity was evoked by replacing growth media containing basal or basal+10% increased glucose with unbuffered isotonic solution of pH 7.4. Innately faster proliferation of T24 cell line [ ] than TRT-HUI cells [ ] at basal and basal +10% increased glucose resulted in steeper glycogen depletion (panel A-B) at 60- and 120-min (***p value <0.0001) whereas fatty acid mimetic (BA) slowed glycogen depletion by inhibiting the conversion of glycogen stores into fatty acids at basal (panel C) and at basal+10% increased glucose (panel D). BA evoked cell cycle arrest also slowed proliferation amidst glucose scarcity.

Figure 7.

Brief glucose scarcity was evoked by replacing growth media containing basal or basal+10% increased glucose with unbuffered isotonic solution of pH 7.4. An innately faster proliferation of T24 cell line compared to TRT-HU1cell line resulted in steeper pH decline at 60 and 180 min, p<0.01(panel A). Steeper slope for pH decline in T24 cells [ ] grown at basal +10% increased glucose, p value <0.0001 (panel B) indexes that rapid proliferation amidst glucose scarcity increases lactic acid production (pH decline) in a feed-forward manner whereas flatter slope of pH decline in BA treated T24 and TRT-HU1 cells grown at basal (panel C) and basal+10% increase glucose (panel D) is consistent with reduced glycogenolysis and BA evoked cell cycle arrest reducing lactic acid production.

Figure 7.

Brief glucose scarcity was evoked by replacing growth media containing basal or basal+10% increased glucose with unbuffered isotonic solution of pH 7.4. An innately faster proliferation of T24 cell line compared to TRT-HU1cell line resulted in steeper pH decline at 60 and 180 min, p<0.01(panel A). Steeper slope for pH decline in T24 cells [ ] grown at basal +10% increased glucose, p value <0.0001 (panel B) indexes that rapid proliferation amidst glucose scarcity increases lactic acid production (pH decline) in a feed-forward manner whereas flatter slope of pH decline in BA treated T24 and TRT-HU1 cells grown at basal (panel C) and basal+10% increase glucose (panel D) is consistent with reduced glycogenolysis and BA evoked cell cycle arrest reducing lactic acid production.

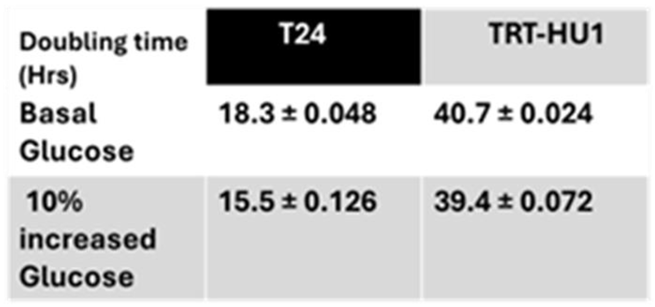

Table 1.

Two-fold faster doubling time of T24 than TRT-HU1 is dependent on 5-fold higher basal glucose levels of 16mM and 3mM in McCoy’s 5A growth media and Keratinocyte Serum Free media, respectively as an additional 10% glucose increase from basal levels to 17.6mM and 3.3mM significantly decreased the doubling time by >2.8h vs ~ 1h for T24 and TRT-HU1, respectively.

Table 1.

Two-fold faster doubling time of T24 than TRT-HU1 is dependent on 5-fold higher basal glucose levels of 16mM and 3mM in McCoy’s 5A growth media and Keratinocyte Serum Free media, respectively as an additional 10% glucose increase from basal levels to 17.6mM and 3.3mM significantly decreased the doubling time by >2.8h vs ~ 1h for T24 and TRT-HU1, respectively.