Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

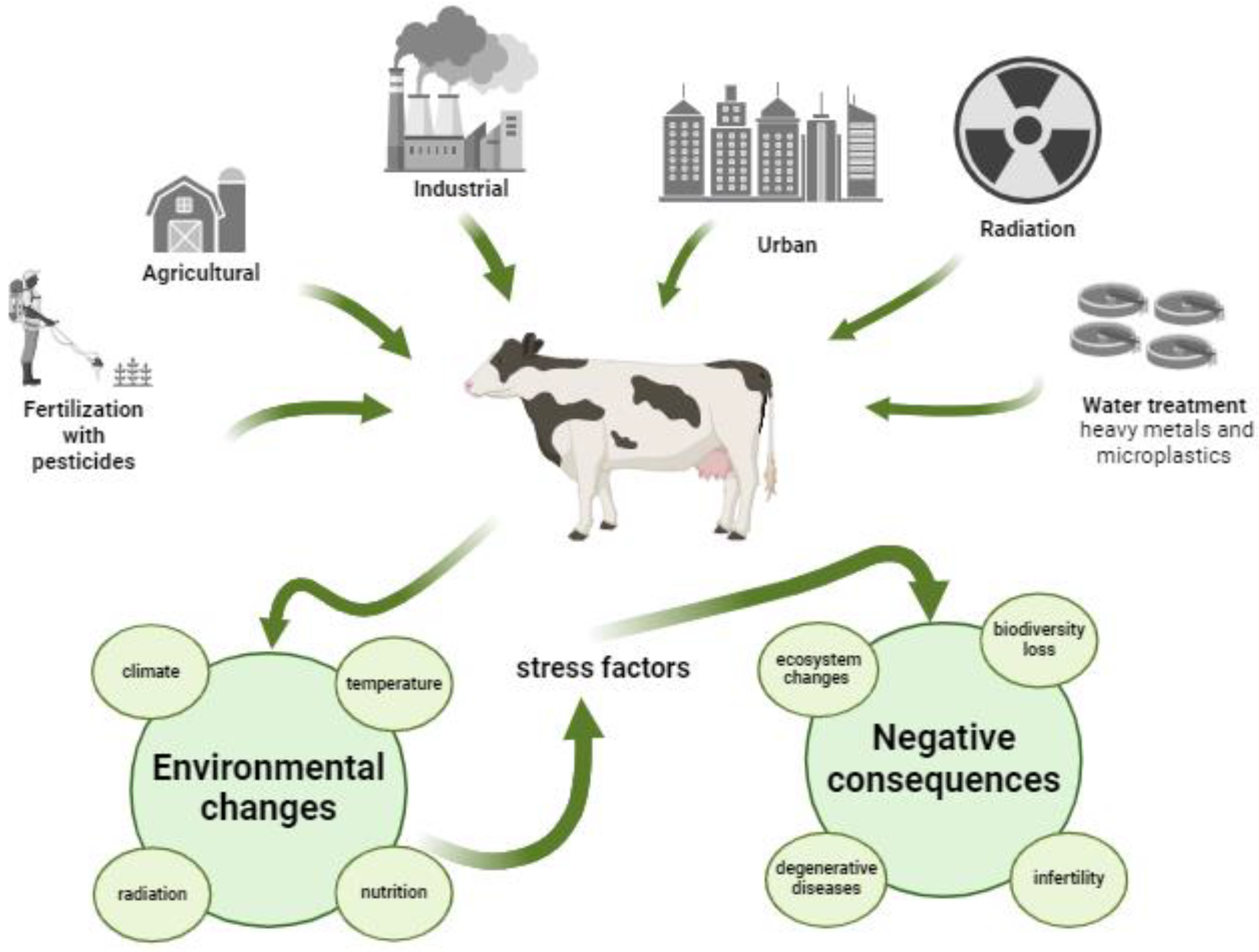

1. Introduction

2. Technological Applications to Improve Fertility

2.1. Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART)

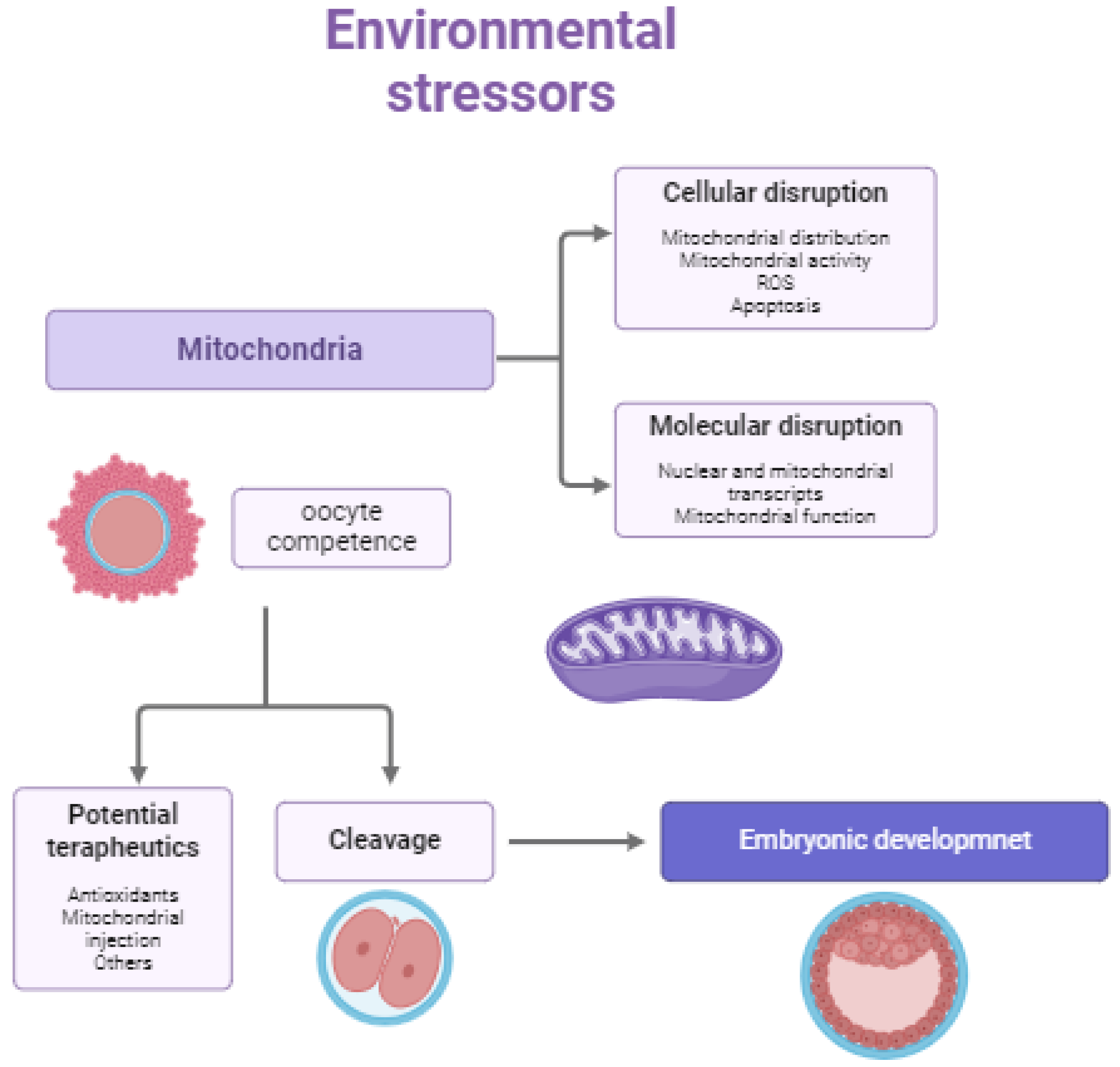

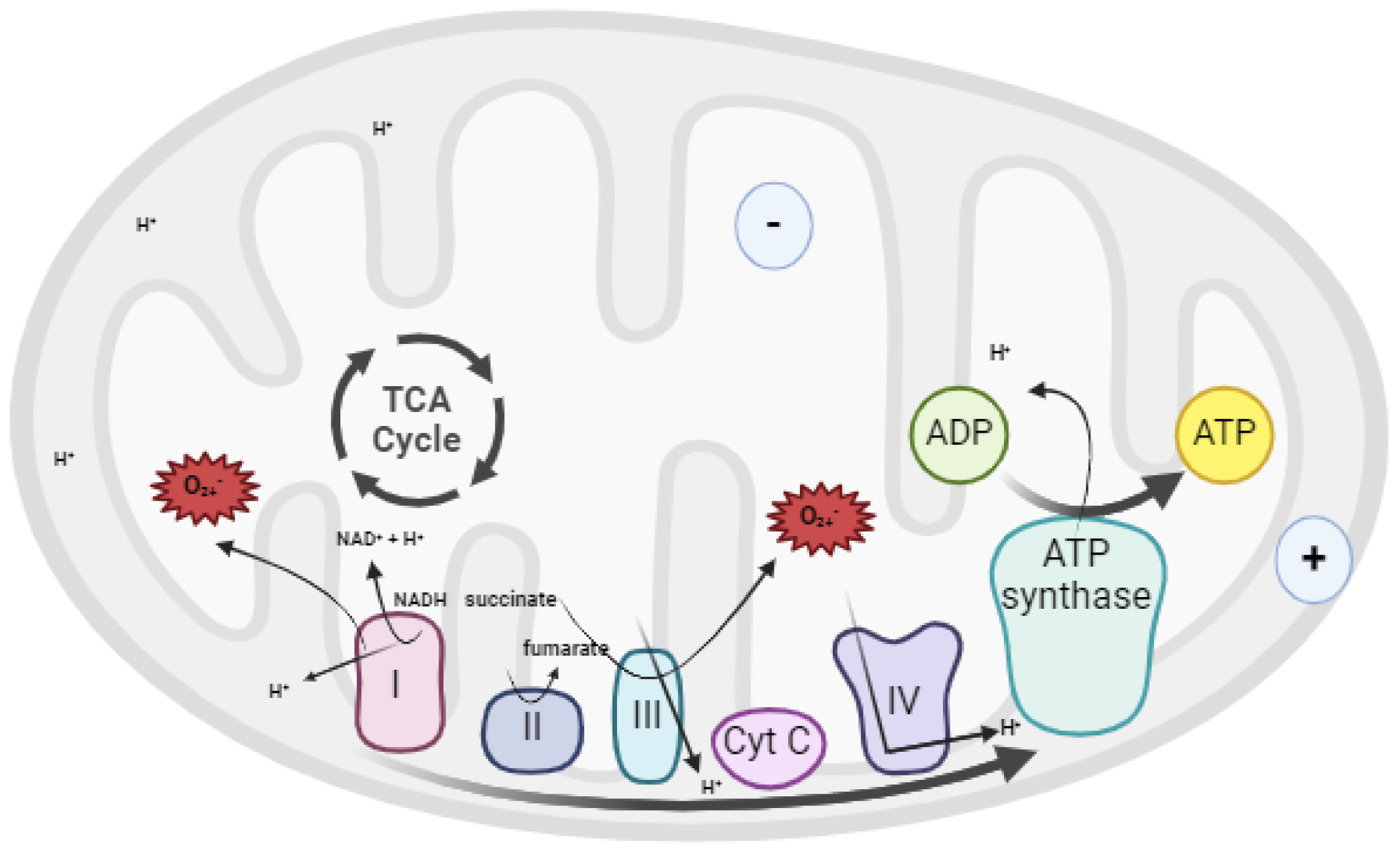

3. The Role of Mitochondria in Gametes Functionality

4. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Gametes and Embryos

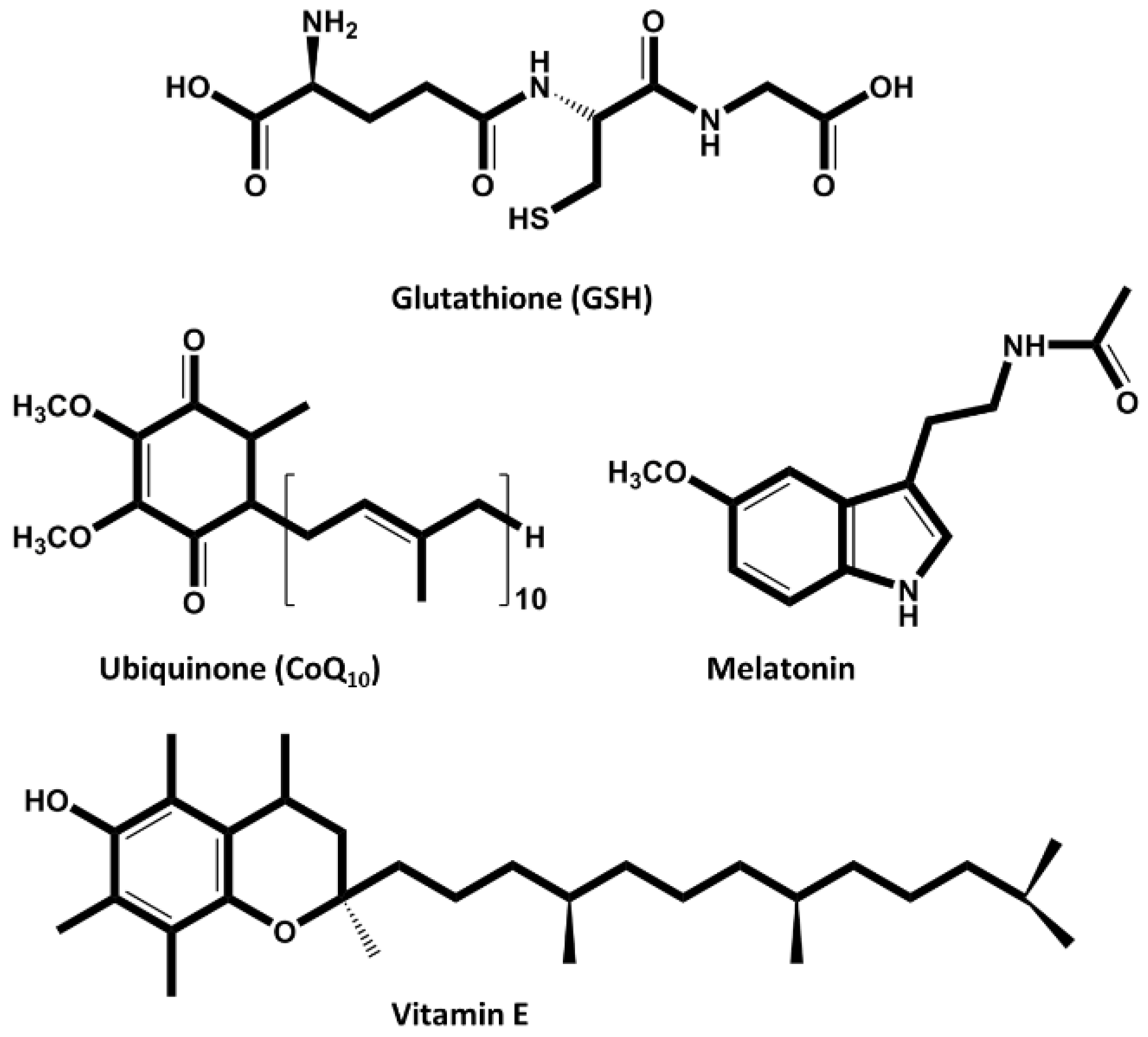

5. Antioxidants in the Reproductive Medicine

5.1. Endogenous Antioxidants

5.2. Exogenous Antioxidants

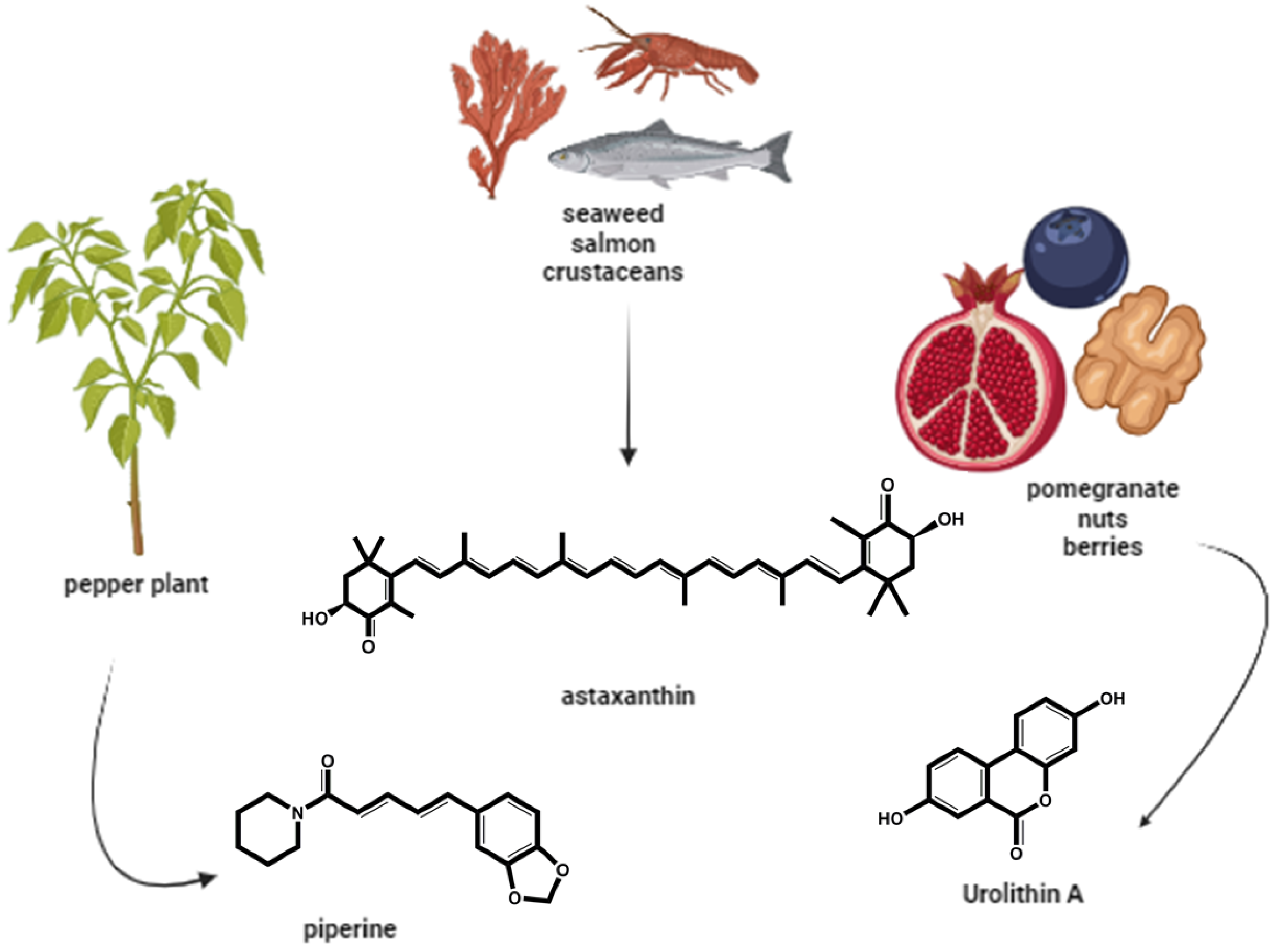

5.2.1. Naturally-Occurring Antioxidants

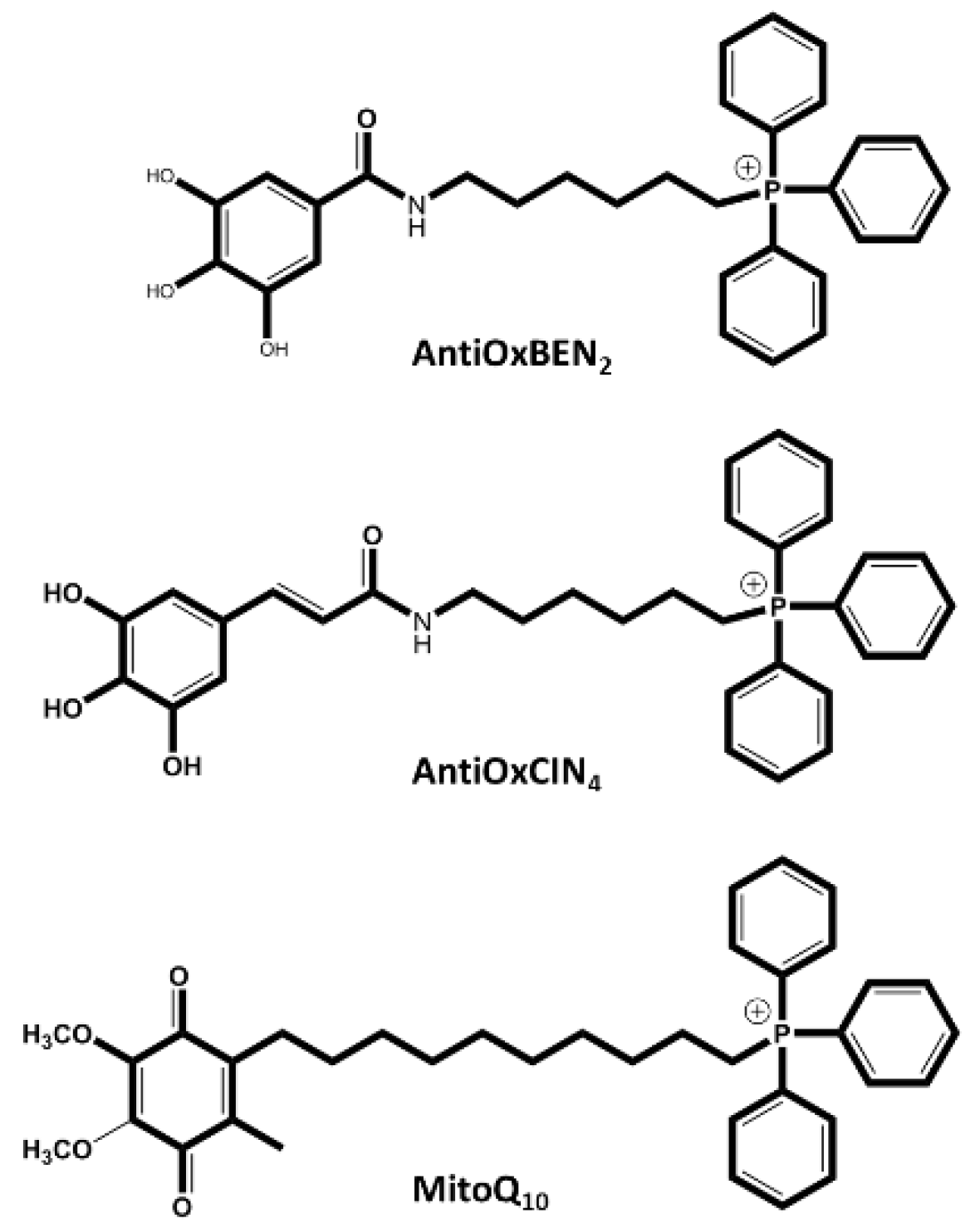

5.2.2. Synthetic Mitochondriotropic Antioxidants

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luoma, J. Challenged Conceptions: Environmental Chemicals and Fertility. In Proceedings of the Understanding Environmental Contaminants and Human Fertility: Science and Strategy; Stanford University School of Medicine’s: Stanford, October 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Canipari, R.; De Santis, L.; Cecconi, S. Female Fertility and Environmental Pollution. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 8802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, D.; Mao, R.; Wang, D.; Yu, P.; Zhou, C.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Nie, Y.; Liao, H.; Peng, C. Association of Plasma Metal Levels with Outcomes of Assisted Reproduction in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Biol Trace Elem Res 2024, 202, 4961–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lou, H.; Zhang, L.; Moreira, J.P.; Jin, F. Exposure of Women Undergoing In-Vitro Fertilization to per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Evidence on Negative Effects on Fertilization and High-Quality Embryos. Environmental Pollution 2024, 359, 124474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, A.; Boni, R.; Tosti, E. Gamete Quality in a Multistressor Environment. Environ Int 2020, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, R.; Marques, C.C.; Pimenta, J.; Barbas, J.P.; Baptista, M.C.; Diniz, P.; Torres, A.; Lopes-da-Costa, L. Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) Directed to Germplasm Preservation. In Advances in Animal Health, Medicine and Production; Springer International Publishing, 2020; pp. 199–215.

- Sakali, A.-K.; Bargiota, A.; Bjekic-Macut, J.; Macut, D.; Mastorakos, G.; Papagianni, M. Environmental Factors Affecting Female Fertility. Endocrine 2024, 86, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaPointe, S.; Lee, J.C.; Nagy, Z.P.; Shapiro, D.B.; Chang, H.H.; Wang, Y.; Russell, A.G.; Hipp, H.S.; Gaskins, A.J. Air Pollution Exposure in Vitrified Oocyte Donors and Male Recipient Partners in Relation to Fertilization and Embryo Quality. Environ Int 2024, 193, 109147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Z. Symposium Review: Reduction in Oocyte Developmental Competence by Stress Is Associated with Alterations in Mitochondrial Function. J Dairy Sci 2018, 101, 3642–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.R.; Schoevers, E.J.; Roelen, B.A.J. Usefulness of Bovine and Porcine IVM/IVF Models for Reproductive Toxicology. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2014, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gameiro, S. Infertility. In Encyclopedia of Mental Health: Second Edition; Elsevier Inc., 2016; pp. 375–383 ISBN 9780123970459.

- Kiesswetter, M.; Marsoner, H.; Luehwink, A.; Fistarol, M.; Mahlknecht, A.; Duschek, S. Impairments in Life Satisfaction in Infertility: Associations with Perceived Stress, Affectivity, Partnership Quality, Social Support and the Desire to Have a Child. Behavioral Medicine 2020, 46, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkodziak, P.; Wozniak, S.; Czuczwar, P.; Wozniakowska, E.; Milart, P.; Mroczkowski, A.; Paszkowski, T. Infertility in the Light of New Scientific Reports – Focus on Male Factor. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine 2016, 23, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, A.A.; Reijo Pera, R.A. Infertility. Brenner’s Encyclopedia of Genetics: Second Edition 2013, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskins, A.J.; Chavarro, J.E. Diet and Fertility: A Review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018, 218, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Peng, W.F.; Hu, X.J.; Zhao, Y.X.; Lv, F.H.; Yang, J. Global Genomic Diversity and Conservation Priorities for Domestic Animals Are Associated with the Economies of Their Regions of Origin. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawer, A.; Sychrová, E.; Labohá, P.; Raška, J.; Jambor, T.; Babica, P.; Sovadinová, I. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals Rapidly Affect Intercellular Signaling in Leydig Cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2020, 404, 115177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendelman, M.; Roth, Z. Incorporation of Coenzyme Q10 into Bovine Oocytes Improves Mitochondrial Features and Alleviates the Effects of Summer Thermal Stress on Developmental Competence. Biol Reprod 2012, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capela, L.; Leites, I.; Romão, R.; Lopes-Da-costa, L.; Pereira, R.M.L.N. Impact of Heat Stress on Bovine Sperm Quality and Competence. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, J.L.M.R.; Van Soom, A.; Opsomer, G.; Goovaerts, I.G.F.; Bols, P.E.J. Reduced Fertility in High-Yielding Dairy Cows: Are the Oocyte and Embryo in Danger? Part II. Mechanisms Linking Nutrition and Reduced Oocyte and Embryo Quality in High-Yielding Dairy Cows. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2008, 43, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Tripathi, S.K.; Gupta, P.S.P.; Mondal, S. Nutritional and Metabolic Stressors on Ovine Oocyte Development and Granulosa Cell Functions in Vitro. Cell Stress Chaperones 2018, 23, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hm Viana, J. 2020 Statistics of Embryo Production and Transfer in Domestic Farm Animals; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, C.; Lazzari, G. Practical Aspects of IVM/IVF in Cattle. Anim Reprod Sci 1996, 42, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker Gaddis, K.L.; Dikmen, S.; Null, D.J.; Cole, J.B.; Hansen, P.J. Evaluation of Genetic Components in Traits Related to Superovulation, in Vitro Fertilization, and Embryo Transfer in Holstein Cattle. J Dairy Sci 2017, 100, 2877–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaginuma, H.; Funshima, N.; Tanikawa, N.; Miyamura, M.; Tsuchiya, H.; Noguchi, T.; Iwata, H.; Kuwayama, T.; Shirasuna, K.; HAMANO, S. Improvement of Fertility in Repeat Breeder Dairy Cattle by Embryo Transfer Following Artificial Insemination: Possibility of Interferon Tau Replenishment Effect. Journal of Reproduction and Development 2019, 65, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funeshima, N.; Noguchi, T.; Onizawa, Y.; Yaginuma, H.; Mitamura, M.; Tsuchiya, H.; Iwata, H.; Kuwayama, T.; Hamano, S.; Shirasuna, K. The Transfer of Parthenogenetic Embryos Following Artificial Insemination in Cows Can Enhance Pregnancy Recognition via the Secretion of Interferon Tau. Journal of Reproduction and Development 2019, 65, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, P.J. Realizing the Promise of IVF in Cattle—an Overview. Theriogenology 2006, 65, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, L.G.B.; Dikmen, S.; Ortega, M.S.; Hansen, P.J. Postnatal Phenotype of Dairy Cows Is Altered by in Vitro Embryo Production Using Reverse X-Sorted Semen. J Dairy Sci 2017, 100, 5899–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, J.L.M.R.; Rizos, D.; Sturmey, R.; Bossaert, P.; Gutierrez-Adan, A.; Van Hoeck, V.; Valckx, S.; Bols, P.E.J. Intrafollicular Conditions as a Major Link between Maternal Metabolism and Oocyte Quality: A Focus on Dairy Cow Fertility. Reprod Fertil Dev 2012, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Malhi, P.S.; Adams, G.P.; Mapletoft, R.J.; Singh, J. Oocyte Developmental Competence in a Bovine Model of Reproductive Aging. Reproduction 2007, 134, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Gupta, S.; Sharma, R. Oxidative Stress and Its Implications in Female Infertility - A Clinician’s Perspective. Reprod Biomed Online 2005, 11, 641–650. [Google Scholar]

- Song, P.; Liu, C.; Sun, M.; Liu, J.; Lin, P.; Wang, A.; Jin, Y. Oxidative Stress Induces Bovine Endometrial Epithelial Cell Damage through Mitochondria-Dependent Pathways. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Said, T.M.; Bedaiwy, M.A.; Banerjee, J.; Alvarez, J.G. Oxidative Stress in an Assisted Reproductive Techniques Setting. Fertil Steril 2006, 86, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, R.F.; Annes, K.; Ispada, J.; de Lima, C.B.; dos Santos, É.C.; Fontes, P.K.; Gouveia Nogueira, M.F.; Milazzotto, M.P. Corrigendum to “Oxidative Stress Alters the Profile of Transcription Factors Related to Early Development on in Vitro Produced Embryos” (Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity (2017) 2017 (1502489). Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.G.; Hasler, J.F. A 100-Year Review: Reproductive Technologies in Dairy Science. J Dairy Sci 2017, 100, 10314–10331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, R.; Marques, C. Produção e Transferência de Embriões: Uma Técnica Em Expansão; Vida Rural, 2017. 1892. 28-29.

- Verberckmoes, S.; Soom, A. Van; De Kruif, A. Intra-Uterine Insemination in Farm Animals and Humans. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2004, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, L.H.A. The Development of in Vitro Embryo Production in the Horse. Equine Vet J 2018, 50, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, K. Assisted Reproductive Techniques in Mares. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2018, 53, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inhorn, M.C.; Patrizio, P. Infertility around the Globe: New Thinking on Gender, Reproductive Technologies and Global Movements in the 21st Century. Hum Reprod Update 2014, 21, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Tao, J.; Chai, M.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, G.; He, C.; Xie, L.; Ji, P.; Dai, Y.; et al. Melatonin Improves the Quality of Inferior Bovine Oocytes and Promoted Their Subsequent IVF Embryo Development: Mechanisms and Results. Molecules 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizos, D.; Clemente, M.; Bermejo-Alvarez, P.; de La Fuente, J.; Lonergan, P.; Gutiérrez-Adán, A. Consequences of In Vitro Culture Conditions on Embryo Development and Quality. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2008, 43, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.M.; Marques, C.C. Animal Oocyte and Embryo Cryopreservation. Cell Tissue Bank 2008, 9, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, M.; Ito, J.; Shirasuna, K.; Kuwayama, T.; Iwata, H. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Regulate Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Porcine Embryos. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Palermo, G.D.; Neri, Q. V.; Rosenwaks, Z. To ICSI or Not to ICSI. Semin Reprod Med 2015, 33, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, E.M.; Maclellan, L.J.; Stokes, J.A.E. In Vitro Culture of Embryos from Horses. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press Inc., 2019; Vol. 2006, pp. 219–227.

- Bedoschi, G.; Roque, M.; Esteves, S.C. ICSI and Male Infertility: Consequences to Offspring. In Male Infertility; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 767–775. [Google Scholar]

- Duranthon, V.; Chavatte-Palmer, P. Long Term Effects of ART: What Do Animals Tell Us? Mol Reprod Dev 2018, 85, 348–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes, J.H.F.; Nonato-Junior, I.; Sanches, B.V.; Ereno-Junior, J.C.; Uvo, S.; Barreiros, T.R.R.; Oliveira, J.A.; Hasler, J.F.; Seneda, M.M. Comparison of Embryo Yield and Pregnancy Rate between in Vivo and in Vitro Methods in the Same Nelore (Bos Indicus) Donor Cows. Theriogenology 2009, 71, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, S.; Block, J.; Seidel, G.E.; Brink, Z.; McSweeney, K.; Farin, P.W.; Bonilla, L.; Hansen, P.J. Pregnancy Rates of Lactating Cows after Transfer of in Vitro Produced Embryos Using X-Sorted Sperm. Theriogenology 2013, 79, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, É.; Marques, C.C.; Pimenta, J.; Jorge, J.; Baptista, M.C.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Pereira, R.M.L.N. Anti-Aging Effect of Urolithin a on Bovine Oocytes in Vitro. Animals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi, H.; Takahashi, T.; Takahashi, E.; Tezuka, N.; Nakahara, K.; Takahashi, K.; Kurachi, H. Aged Mouse Oocytes Fail to Readjust Intracellular Adenosine Triphosphates at Fertilization. Biol Reprod 2005, 72, 1256–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, R.M.; Marques, C.C.; Baptista, M.C.; Vasques, M.I.; Horta, A.E.M. Embryos and Culture Cells: A Model for Studying the Effect of Progesterone. Anim Reprod Sci 2009, 111, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Munck, N.; Janssens, R.; Segers, I.; Tournaye, H.; Van De Velde, H.; Verheyen, G. Influence of Ultra-Low Oxygen (2%) Tension on in-Vitro Human Embryo Development. Human Reproduction 2019, 34, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Rieger, D.; Mastenbroek, S.; Meintjes, M.; Janssens, R.; Catt, J.; Morbeck, D.; Mortimer, D.; Fawzy, M.; Alikani, M.; et al. ‘There Is Only One Thing That Is Truly Important in an IVF Laboratory: Everything’ Cairo Consensus Guidelines on IVF Culture Conditions. Reprod Biomed Online 2020, 40, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, D.; Cohen, J.; Mortimer, S.T.; Fawzy, M.; McCulloh, D.H.; Morbeck, D.E.; Pollet-Villard, X.; Mansour, R.T.; Brison, D.R.; Doshi, A.; et al. Cairo Consensus on the IVF Laboratory Environment and Air Quality: Report of an Expert Meeting. In Proceedings of the Reproductive BioMedicine Online; Elsevier Ltd, June 1 2018; Vol. 36; pp. 658–674. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, C.C.; Santos-Silva, C.; Rodrigues, C.; Matos, J.E.; Moura, T.; Baptista, M.C.; Horta, A.E.M.; Bessa, R.J.B.; Alves, S.P.; Soveral, G.; et al. Bovine Oocyte Membrane Permeability and Cryosurvival: Effects of Different Cryoprotectants and Calcium in the Vitrification Media. Cryobiology 2018, 81, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, J.I.; Rutherford\, A.J.; Killick, S.R.; Maguiness, S.D.; Partridge, R.J.; Leese, H.J. Human Tubal Fluid: Production, Nutrient Composition and Response to Adrenergic Agents. Human Reproduction vol 1997, 12, 2451–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, M.; Ferreira, F.C.; Marques, C.C.; Batista, M.C.; Oliveira, P.J.; Lidon, F.; Duarte, S.C.; Teixeira, J.; Pereira, R.M.L.N. Effect of Urolithin A on Bovine Sperm Capacitation and In Vitro Fertilization. Animals 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.C.; Marques, C.C.; Baptista, M.C.; Pimenta, J.; Teixeira, J.; Montezinho, L.; Cagide, F.; Borges, F.; Oliveira, P.J.; Pereira, R.M.L.N. Effect of a Novel Hydroxybenzoic Acid Based Mitochondria Directed Antioxidant Molecule on Bovine Sperm Function and Embryo Production. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, M.L.M.; Day, M.L.; Morris, M.B. Redox Regulation and Oxidative Stress in Mammalian Oocytes and Embryos Developed in Vivo and in Vitro. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.P.; Amaral, A.; Baptista, M.; Tavares, R.; Campo, P.C.; Peregrín, P.C.; Freitas, A.; Paiva, A.; Almeida-Santos, T.; Ramalho-Santos, J. Not All Sperm Are Equal: Functional Mitochondria Characterize a Subpopulation of Human Sperm with Better Fertilization Potential. PLoS One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Mabalirajan, U. Rejuvenating Cellular Respiration for Optimizing Respiratory Function: Targeting Mitochondria. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2016, 310, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, D.C.; Fan, W.; Procaccio, V. Mitochondrial Energetics and Therapeutics. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 2010, 5, 297–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, A.; Smitz, J.E.J.; Sukhikh, G.T.; Mazunin, I. The Role of Mitochondria in Oocyte Maturation. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, J.S.; D’Imprima, E.; Vonck, J. Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Complexes. In; 2018; pp. 167–227.

- Schofield, J.H.; Schafer, Z.T. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species and Mitophagy: A Complex and Nuanced Relationship. Antioxid Redox Signal 2021, 34, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Lv, B.; Zhang, J.; Ni, B.; Xue, Z. Mitochondria: The Panacea to Improve Oocyte Quality? Ann Transl Med 2019, 7, 789–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, R.J.; Whiting, S.; De Iuliis, G.N.; McClymont, S.; Mitchell, L.A.; Baker, M.A. Electrophilic Aldehydes Generated by Sperm Metabolism Activate Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and Apoptosis by Targeting Succinate Dehydrogenase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 33048–33060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, R.J.; Gibb, Z.; Baker, M.A.; Drevet, J.; Gharagozloo, P. Causes and Consequences of Oxidative Stress in Spermatozoa. Reprod Fertil Dev 2016, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppers, A.J.; De Iuliis, G.N.; Finnie, J.M.; McLaughlin, E.A.; Aitken, R.J. Significance of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species in the Generation of Oxidative Stress in Spermatozoa. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2008, 93, 3199–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, M.; Sousa, A.P.; Fernandes, R.; Ferreira, A.F.; Almeida-Santos, T.; Ramalho-Santos, J. Aging-Related Mitochondrial Alterations in Bovine Oocytes. Theriogenology 2020, 157, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J. Impact of Oxidative Stress on Male and Female Germ Cells: Implications for Fertility. Reproduction 2020, 159, R189–R201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Showell, M.G.; Brown, J.; Clarke, J.; Hart, R.J. Antioxidants for Female Subfertility. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigami, M. Superoxide Dismutase. Nippon rinsho. Japanese journal of clinical medicine 1998, 56 Suppl 3, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Stress: Concept and Some Practical Aspects. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, C.; Teng, S.; Saunders, P.T.K. A Single, Mild, Transient Scrotal Heat Stress Causes Hypoxia and Oxidative Stress in Mouse Testes, Which Induces Germ Cell Death. Biol Reprod 2009, 80, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, A.; Gad, A.; Salilew-Wondim, D.; Prastowo, S.; Held, E.; Hoelker, M.; Rings, F.; Tholen, E.; Neuhoff, C.; Looft, C.; et al. Bovine Embryo Survival under Oxidative-Stress Conditions Is Associated with Activity of the NRF2-Mediated Oxidative-Stress-Response Pathway. Mol Reprod Dev 2014, 81, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, R.F.; Annes, K.; Ispada, J.; De Lima, C.B.; Dos Santos, É.C.; Fontes, P.K.; Nogueira, M.F.G.; Milazzotto, M.P. Oxidative Stress Alters the Profile of Transcription Factors Related to Early Development on in Vitro Produced Embryos. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, A.; Fukushima, Y.; Yamamoto, A.; Amatsu, Y.; Chen, X.; Nishigori, M.; Yoshioka, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Koshiba, T.; Watanabe, T. Increased ROS Levels in Mitochondrial Outer Membrane Protein Mul1-deficient Oocytes Result in Abnormal Preimplantation Embryogenesis. FEBS Lett 2024, 598, 1740–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, T.T.; Lysiak, J.J. Oxidative Stress: A Common Factor in Testicular Dysfunction. J Androl 2008, 29, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, C.; Scarlata, E. Oxidative Stress and Reproductive Function: The Protection of Mammalian Spermatozoa against Oxidative Stress. Reproduction 2022, 164, F67–F78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neha, K.; Haider, M.R.; Pathak, A.; Yar, M.S. Medicinal Prospects of Antioxidants: A Review. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 178, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, G.J.; Hempstock, J.; Jauniaux, E. Oxygen, Early Embryonic Metabolism and Free Radical-Mediated Embryopathies. Reprod Biomed Online 2003, 6, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, A.; Eckert, A. Brain Aging and Neurodegeneration: From a Mitochondrial Point of View. J Neurochem 2017, 143, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.A.J.; Hartley, R.C.; Cochemé, H.M.; Murphy, M.P. Mitochondrial Pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2012, 33, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, G.; Aiello Talamanca, A.; Castello, G.; Cordero, M.D.; D’Ischia, M.; Gadaleta, M.N.; Pallardó, F. V.; Petrović, S.; Tiano, L.; Zatterale, A. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction across Broad-Ranging Pathologies: Toward Mitochondria-Targeted Clinical Strategies. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, K.; Imai, A.; Sato, S.; Nishino, K.; Watanabe, S.; Somfai, T.; Kobayashi, E.; Takeda, K. Effects of Reduced Glutathione Supplementation in Semen Freezing Extender on Frozen-Thawed Bull Semen and in Vitro Fertilization. Journal of Reproduction and Development 2022, 68, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeoye, O.; Olawumi, J.; Opeyemi, A.; Christiania, O. Review on the Role of Glutathione on Oxidative Stress and Infertility. J Bras Reprod Assist 2018, 22, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, R.M.; Baptista, M.C.; Vasques, M.I.; Horta, A.E.M.; Portugal, P.V.; Bessa, R.J.B.; Silva, J.C. e; Pereira, M.S.; Marques, C.C. Cryosurvival of Bovine Blastocysts Is Enhanced by Culture with Trans-10 Cis-12 Conjugated Linoleic Acid (10t,12c CLA). Anim Reprod Sci 2007, 98, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.-H.; Zhao, X.-L.; Tian, W.-Q.; Zan, L.-S.; Li, Q.-W. Effects of Vitamin E Supplementation in the Extender on Frozen-Thawed Bovine Semen Preservation. Animal 2011, 5, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkoun, B.; Galas, L.; Dumont, L.; Rives, A.; Saulnier, J.; Delessard, M.; Rondanino, C.; Rives, N. Vitamin E but Not GSH Decreases Reactive Oxygen Species Accumulation and Enhances Sperm Production during In Vitro Maturation of Frozen-Thawed Prepubertal Mouse Testicular Tissue. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIKI, E. Interaction of Ascorbate and A-Tocopherol. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1987, 498, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horowitz, S. Coenzyme Q10 One Antioxidant, Many Promising Applications. Alternative & Complementary Therapies 2009, 9, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernster, L.; Forsmark, P.; Nordenbrand1, K. The Mode of Action of Lipid-Soluble Antioxidants in Biological Membranes. Relationship between the Effects of Ubiquinol and Vitamin E as Inhibitors of Lipid Peroxidation in Submitochondrial Particles. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, R.M.; Seli, E. Mitochondria as Therapeutic Targets in Assisted Reproduction. Human Reproduction 2024, 39, 2147–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oroian, M.; Escriche, I. Antioxidants: Characterization, Natural Sources, Extraction and Analysis. Food Research International 2015, 74, 10–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarria, D.; Silva, T.; MagalhãesE Silva, D.; Remiaõ, F.; Borges, F. Lessons from Black Pepper: Piperine and Derivatives Thereof. Expert Opin Ther Pat 2016, 26, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, A.K.; Ray, A.K.; Mishra, S.K. Molecular and Pharmacological Aspects of Piperine as a Potential Molecule for Disease Prevention and Management: Evidence from Clinical Trials. Beni Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Lee, D.Y.; Lim, J.H.; Oh, W.K.; Park, J.T.; Park, S.C.; Cho, K.A. Piperine: An Anticancer and Senostatic Drug. Frontiers in Bioscience - Landmark 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.; Oliveira, A.; Lindon, F.; Oliveira, P.O.; Teixeira, J.; Pereira, R.M.L.N. ;. Effect of the Natural Antioxidant Piperine on Maturation of Bovine Oocyte Production and Embryo Production. In Proceedings of the XIV Congresso Ibérico sobre Recursos Genéticos Animais; Vila Real, 2024. p. 104.

- Teixeira, J.; Oliveira, C.; Amorim, R.; Cagide, F.; Garrido, J.; Ribeiro, J.A.; Pereira, C.M.; Silva, A.F.; Andrade, P.B.; Oliveira, P.J.; et al. Development of Hydroxybenzoic-Based Platforms as a Solution to Deliver Dietary Antioxidants to Mitochondria. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopoldini, M.; Russo, N.; Toscano, M. The Molecular Basis of Working Mechanism of Natural Polyphenolic Antioxidants. Food Chem 2011, 125, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food Sources and Bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr 2004, 79, 727–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.R.; Li, S.; Lin, C.C. Effect of Resveratrol and Pterostilbene on Aging and Longevity. BioFactors 2018, 44, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, D.; Gao, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jia, R.; Bai, Y.; Shi, D.; Lu, F. Effects of Astaxanthin on the Physiological State of Porcine Ovarian Granulose Cells Cultured In Vitro. Antioxidants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, S.; Alyasin, A.; Saedi, M.; Nekoonam, S.; Khodarahmian, M.; Moeini, A.; Amidi, F. Astaxanthin Ameliorates Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Reproductive Outcomes in Endometriosis Patients Undergoing Assisted Reproduction: A Randomized, Triple-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Chen, F.; Lei, J.; Li, Q.; Zhou, B. Activation of the MiR-34a-Mediated SIRT1/MTOR Signaling Pathway by Urolithin A Attenuates d-Galactose-Induced Brain Aging in Mice. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 1269–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amico, D.; Andreux, P.A.; Valdés, P.; Singh, A.; Rinsch, C.; Auwerx, J. Impact of the Natural Compound Urolithin A on Health, Disease, and Aging. Trends Mol Med 2021, 27, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.; Marques, C.C.; Baptista, M.C.; Pimenta, J.; Teixeira, J.; Cagide, F.; Borges, F.; Montezinho, L.; Oliveira, P.; Pereira, R.M.L.N. Beneficial Effect of Mitochondriotropic Antioxidants on Oocyte Maturation and Embryo Production. Eur J Clin Invest 2020, 50, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauskela JS MitoQ--a Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant. IDrugs 2007, 10, 399–412.

- Marei, W.F.A.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Pintelon, I.; Mohey-Elsaeed, O.; Bols, P.E.J.; Leroy, J.L.M.R. Mitochondria-Targeted Therapy Rescues Development and Quality of Embryos Derived from Oocytes Matured under Oxidative Stress Conditions: A Bovine in Vitro Model. Human Reproduction 2019, 34, 1984–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzeyli, M.H.; Amidi, F.; Shamsara, M.; Nazarian, H.; Eini, F.; Shirzeyli, F.H.; Zolbin, M.M.; Novin, M.G.; Joupari, M.D. Exposing Mouse Oocytes to Mitoq during in Vitro Maturation Improves Maturation and Developmental Competence. Iran J Biotechnol 2020, 18, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhawagah, A.R.; Donato, G.G.; Poletto, M.; Martino, N.A.; Vincenti, L.; Conti, L.; Necchi, D.; Nervo, T. Effect of Mitoquinone on Sperm Quality of Cryopreserved Stallion Semen. J Equine Vet Sci 2024, 141, 105168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Câmara, D.R.; Ibanescu, I.; Siuda, M.; Bollwein, H. Mitoquinone Does Not Improve Sperm Cryo-resistance in Bulls. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2022, 57, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, J.; Cagide, F.; Benfeito, S.; Soares, P.; Garrido, J.; Baldeiras, I.; Ribeiro, J.A.; Pereira, C.M.; Silva, A.F.; Andrade, P.B.; et al. Development of a Mitochondriotropic Antioxidant Based on Caffeic Acid: Proof of Concept on Cellular and Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Models. J Med Chem 2017, 60, 7084–7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.; Cagide, F.; Teixeira, J.; Amorim, R.; Sequeira, L.; Mesiti, F.; Silva, T.; Garrido, J.; Remião, F.; Vilar, S.; et al. Hydroxybenzoic Acid Derivatives as Dual-Target Ligands: Mitochondriotropic Antioxidants and Cholinesterase Inhibitors. Front Chem 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfeito, S.; Oliveira, C.; Fernandes, C.; Cagide, F.; Teixeira, J.; Amorim, R.; Garrido, J.; Martins, C.; Sarmento, B.; Silva, R.; et al. Fine-Tuning the Neuroprotective and Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Profile of Multi-Target Agents Designed to Prevent Progressive Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 167, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.; Basit, F.; Willems, P.H.G.M.; Wagenaars, J.A.; van de Westerlo, E.; Amorim, R.; Cagide, F.; Benfeito, S.; Oliveira, C.; Borges, F.; et al. Mitochondria-Targeted Phenolic Antioxidants Induce ROS-Protective Pathways in Primary Human Skin Fibroblasts. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 163, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, R.; Cagide, F.; Tavares, L.C.; Simões, R.F.; Soares, P.; Benfeito, S.; Baldeiras, I.; Jones, J.G.; Borges, F.; Oliveira, P.J.; et al. Mitochondriotropic Antioxidant Based on Caffeic Acid AntiOxCIN4 Activates Nrf2-Dependent Antioxidant Defenses and Quality Control Mechanisms to Antagonize Oxidative Stress-Induced Cell Damage. Free Radic Biol Med 2022, 179, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, C.; Videira, A.J.C.; Veloso, C.D.; Benfeito, S.; Soares, P.; Martins, J.D.; Gonçalves, B.; Duarte, J.F.S.; Santos, A.M.S.; Oliveira, P.J.; et al. Cytotoxicity and Mitochondrial Effects of Phenolic and Quinone-based Mitochondria-targeted and Untargeted Antioxidants on Human Neuronal and Hepatic Cell Lines: A Comparative Analysis. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira FC; Sousa A; Marques CC; Baptista MC; Teixeira J; Cagide F; Borges F; Oliveira P; Pereira RMLN Effect of a Mitochondriotropic Antioxidant Based on Caffeic Acid (AntiOxCIN4) on Spermatozoa Capacitation and in Vitro Fertilization (Poster). In Proceedings of the Congresso CIISA “Inovação em Pesquisa Animal, Veterinária e Biomédica” - 10-11 novembro; 2022. Pp 10.

- Lourenço B; Ferreira F; Marques CC; Batista MC; Teixeira J; Cagide F; Borges F; Oliveira P; Pereira RMLN Natural Derived Mitochondriotropic Molecules Improve Embryo Quality and Cryosurvival (Poster). In Proceedings of the XIII CONGRESO IBÉRICO SERGA/SPREGA SOBRE RECURSOS GENÉTICOS ANIMALES - 21-23 outubro; 2022.

- Lourenço, B. Effect of Mitochondriotropic Molecules in Reducing Oxidative Stress in Assisted Reprodution Techniques (Tese de Mestrado), Universidade de Lisboa - Faculdade de Ciências: Lisboa, 2020.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).