1. Introduction

Variational principles are the basis for the axiomatic formulation of most sections of physics; for example, in mechanics it is Hamilton's principle, in optics it is Fermat's principle, and in thermodynamics there are even two of them. These are Prigogine's principles of minimum entropy production (MinEPP) [

1,

2] and Ziegler's principles of maximum entropy production (MEPP) [

3,

4]. A nonequilibrium isolated system relaxes to equilibrium producing entropy, and in equilibrium the entropy production is zero, and the entropy is maximum. An open system, depending on the boundary conditions, can relax in either the direction of equilibrium or the direction of nonequilibrium state; during relaxation to equilibrium, entropy increases and entropy is produced, while during relaxation to nonequilibrium, entropy decreases and negentropy is produced. (For more details, see [

5]). Therefore, in this case the second law is determined by the algebraic sum of the entropy and negentropy productions [

5], and the processes in the system depend on the ratio of these productions, since when the entropy production is greater than the negentropy production (here we mean their absolute values), the system relaxes freely, and otherwise the system relaxes forcedly under the action of the corresponding thermodynamic force. Thus, the laws of the Thermodynamics of nonequilibrium processes (TNF) for free and forced relaxation will be different, and accordingly, the variational principles will be different. Ziegler considered MEPP a generalization of the principle of maximum entropy (the second law), i.e. "... a more accurate version of the fundamental law of thermodynamics" [

4], indeed, it follows from MEPP that not only σ ≥ 0, but also dσ ≤ 0. The latter condition was shown for the Rayleigh gas in [

6]. Thus, MEPP is, following Ziegler, a more rigorous formulation of the second law for forced relaxation. In [

7] it is stated that "MEPP forces the system to choose not only the most probable of its possible macrostates, but also the most probable trajectory of movement to this macrostate." Indeed, if the second law speaks of an increase in entropy during relaxation, then MEPP requires that at each subsequent point of the relaxation curve the entropy production be greater than the value at the previous point. Thus, MEPP is a more complete (strict) formulation of the second law. MinEPP was formulated by the Belgian school of thermodynamics headed by I. Prigogine. Despite their considerable efforts, they failed to expand the scope of application of MinEPP, which is applicable in linear thermodynamics in sufficient proximity to equilibrium. Thus, in TNP, there are two diametrically opposed principles - the principle of minimum and maximum entropy production. It is clear that the same value cannot be both minimum and maximum for one thermodynamic object. This state of affairs requires a detailed explanation. Martyushev in [

8] believes that it is impossible to contrast these principles, since they relate to different thermodynamic states, but he did not indicate which states. This work is devoted to the analysis of the original works of the authors of these principles, with the aim of determining the conditions and states in which the principles under study are realized. In order to then create these conditions and states in a model system, with the aim of determining in this system the states under which both principles will be realized in one thermodynamic system under different conditions.

2. Minimum Entropy Production Principle (MinEPP)

In the linear thermodynamics of irreversible processes, I. Prigogine in 1945-1947 formulated the principle of minimum entropy production (MinEPP) [

1]. This principle states that in a system in which thermodynamic flows are related to forces by a linear relationship, and kinetic coefficients are symmetrical, when some of the forces are kept constant. a necessary sufficient condition for stationarity is the minimum production of entropy [

2].

Prigogine connected the increase in entropy (second law) with the direction of time [

9]. This is due to the requirement of system stability, i.e. entropy serves as a Lyapunov function. Entropy is a Lyapunov function for isolated systems. Thermodynamic potentials, such as Helmholtz or Gibbs free energy, are also Lyapunov functions, but for different “boundary conditions” (such as externally maintained values of temperature and volume of the system or temperature and pressure, respectively ). Thus, the second law of thermodynamics is a consequence of the stability of the system.

The next important theorem, valid for systems near equilibrium, is the theorem on the minimum entropy production - MinEPP [

1,

2]. This theorem states that the production of entropy by a system in a stationary state sufficiently close to equilibrium is minimal. For systems whose state changes over time (and subject to the same boundary conditions), the entropy production is greater, i.e. in a system in a dynamic relaxing state, the production of entropy is greater than in a stationary nonequilibrium state [

2]. MinEPP imposes even stricter boundary conditions on the system than linear equations

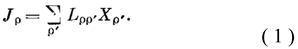

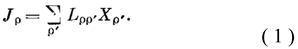

where Jρ and Xρ’ are, respectively, the thermodynamic flow and force, Lρρ’ are the kinetic coefficients. This theorem is valid only within the framework of a theory expressed by strictly linear equations, i.e. it is satisfied only by systems, deviations from equilibrium, of which there are so few and the phenomenological coefficients of the corresponding equations Lррʹ can be considered constant quantities. When given boundary conditions do not allow the system to reach thermodynamic equilibrium, (i.e., a state in which it no produces entropy and dS = 0), the system stops in a state of “minimum dissipation” and produces a minimum of entropy.

3. MinEPP in an Exactly Solvable Rayleigh Gas Model

Thus, Prigogine’s theorem is applicable for relaxations from a nonequilibrium state to the direction of equilibrium states close to equilibrium (linear approximation). To verify this, let us consider the production of entropy in the Rayleigh gas (small admixture of heavy particles in a thermostat of light particles) upon relaxation of the initial nonequilibrium distribution function (DF) to the final equilibrium one. In a Rayleigh gas, due to the low concentration of the heavy component and the large difference in the masses of the particles of the mixture, the establishment of equilibrium in the heavy component is a slow process and occurs against the background of the Maxwellian distribution particles of thermostat. In [

10], the integral of elastic collisions of hard spheres into the L. Boltzmann equation by expansion in powers (

mL/m)

1/2, where m

L and m of the masses of particles of the thermostat and the impurity, respectively, is reduced to the form of the Fokker–Planck differential operator of the form

with initial and boundary conditions

where

F(x,τ) is the DF of heavy particles,

ϕ(x) is the initial DF,

x = ε/kTL,

τ = t/τR are dimensionless energies and time,

ε is the energy of heavy particles,

TL is the temperature of the thermostat, τ

R is the relaxation time of the Rayleigh gas [

9]. Solution (2) with initial and boundary conditions (3) has the form [

10]

where

Lm1/2(x) are the Laguerre polynomials,

Γ(m) is the gamma function, n

0 is the initial number of particles. Solution (4) is applicable for almost all x with the exception of

(mL/m)1/2˃x˃(m/mL)1/2, where the Fokker–Planck equation (2) is not applicable. Having defined the entropy according to Boltzmann in the form

where

k is Boltzmann’s constant, for the change in entropy we obtain

Substituting (4) into (6) we have

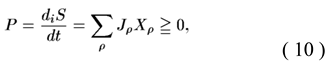

Expression (8) describes the production of entropy during relaxation of the initial nonequilibrium DF to equilibrium. As can be seen from (8), the production of entropy, in accordance with the second law, in the process of relaxation from a nonequilibrium to an equilibrium state, is positive and, in accordance with MinEPP, decreases, reaching a minimum zero value in equilibrium at τ → ∞. If the initial DF is equilibrium, i.e. ϕ(x) = , then σ(τ) = 0.

From expression (8) it is obvious that σ(τ) is concave and dσ/dτ ˂ 0, therefore each point is a local minimum. and σ(∞) is the absolute minimum, equal to zero.

Thus, upon relaxation from an arbitrary (non-equilibrium) state to an equilibrium state, entropy increases with minimal entropy production. Since the system under consideration is isolated, its final state is equilibrium and there are no conditions for obtaining a stationary nonequilibrium state. This state will be realized when considering an open system in paragraph 6.

4. The Principle of Maximum Entropy Production (MEPP)

The maximum entropy production principle (MEPP) was formulated by G. Ziegler in 1961 [

4]. “Numerous experimental investigations spanning over sixty years ( !

P.T. ) have failed to comprehensively validate any of the existing solid-liquid interface (SLI) growth instability models. With the MEPP model, for the first time, breakdown conditions are predicted with a fair degree of accuracy for a number of binary alloys where no previous theoretical model had predictability” [

11] (p.1). However, the literature does not always indicate its scope of applicability. Ziegler's principle is valid for non-stationary systems relaxing to their stationary state, i.e. when a nonstationary system relaxes to its stationary state, it obeys MEPP [

6]. “The Maximum Entropy Production Principle (MEPP) stands out as the overarching principle governing life phenomena in nature. However, its explanatory power beyond heuristics remains controversial. On the one hand, MEPP has been successfully applied mainly to non-living systems that are far from thermodynamic equilibrium. On the other hand, the basic assumptions underlying MEPP's theoretical underpinnings and range of applicability increase the potential for conflicting interpretations." [

12] (p.4). To determine the scope of applicability of MEPP, we need to consider under what conditions MEPP was proven.

Entropy production is a dynamic characteristic, and thermodynamics, although the name contains the word “dynamics,” it does not have an obvious dependence on time.

Therefore, F. Morse, in his monograph “Thermophysics,” called the section of physics known to us – “Thermodynamics” as “Thermostatics”. It became true thermodynamics after nonequilibrium processes began to be studied in it. And we know it now as “Thermodynamics nonequilibrium processes” (TNP), it is based on transport equations, the same as in kinetics, i.e. flows are linear functions of thermodynamic forces (1). Proportionality coefficients are kinetic coefficients that do not depend on flows and forces. The dependence of flows on forces (1) is the central dependence in TNP, therefore K. Eckart called it the thermodynamic equation of motion.

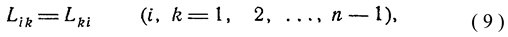

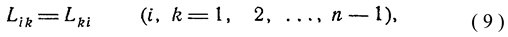

An important role in the development of linear TNP was played by proportionality coefficients between flows and forces, the so-called kinetic coefficients of phenomenological equations (1). The property of invariance under time reversal expresses the fact that the mechanical equations of particle motion are symmetrical with respect to time. This means that when the sign of all velocities changes, the particles will travel in the opposite direction to the trajectories they had previously traversed. Based on this microscopic property of the equations, L. Onsager formulated a macroscopic theorem, the reciprocity relation

Reciprocity relations (2) were derived by L. Onsager in 1931. “Relationships of this type have been proposed and discussed by many authors. The earliest of them belongs to W. Thomson (Lord Kelvin) and concerns thermoelectric phenomena.” [

3]. Subsequently, they were generalized by H. Casimir [

13] to the case of vector and tensor forces, as well as to thermodynamic forces that change their sign when the sign of time is reversed [

14].

It should be noted here that Onsager himself considered the reciprocity relation to be the relation of W. Thompson (Lord Kelvin): “Despite this, he (Lord Kelvin.

P.T.) cautiously considered his reciprocity relation (9) a hypothesis, subject to confirmation or refutation by experimental way, since it could not be completely deduced from fundamental principles by methods known at that time. Currently, Thomson's relation is generally respected and accepted because it has been confirmed within the error of the best measurements" [

15] (p.406). However, only Onsager obtained theoretical evidence of reciprocity relations [

15]. Therefore, at present (8) is known to us as the “Onsager reciprocity relation,” but it would be fair to call it the “Kelvin–Onsager reciprocity relation.”

Of course, the discovery of the reciprocity relation was an important milestone in the history of thermodynamics, despite its apparent simplicity, it has a deep physical meaning, which is still not fully understood. Onsager also believed that the variational principles in TNP should follow from the reciprocity condition [

15]. The variational principle following from the reciprocity relations is also discussed in [

16]. Ziegler in [

3] showed that the reciprocity relations could be interpreted as the principle of the greatest dissipation power, which in the modern understanding corresponds to the MEPP [

3].

In continuum mechanics, where MEPP was first formulated, systems are considered whose state is determined by the mechanical coordinates of position

xk (

k = 1, 2, ...

n) and temperature

θ > 0. The change in

xk is a purely irreversible process, and the change in θ – reversible. As noted above, Ziegler's principle (MEPP) states that when a non-stationary nonequilibrium system relaxes to its stationary state, it obeys the principle of maximum entropy production [

3]. It should be noted that the principle of maximum entropy generation rate or MERR is applicable in both linear and nonlinear regions. In [

4] (p. 415) it is assumed that “if, according to the second law, every closed system tends to a state of maximum entropy, then this assumption does not seem unreasonable for the system, under the influence of given forces

Xki, to change its state in such a way that inside it, at every moment, a maximum of entropy was produced.” This intuitive statement in this or another form is given in many works [

16,

17]. This statement implies that MEPP does not contradict the second law, but does not mean that the second law and MEPP are identical. After all, to fulfill the second law, it is enough for

σ(τ) to be positive. For example, the second law is satisfied during the relaxation of a nonequilibrium state into an equilibrium state, when the production of entropy, in accordance with Prigogine’s principle, is minimal (see paragraph 1).

It is also worth noting Ziegler's interesting idea about the “macroscopic observer”. According to Ziegler, flow changes in entropy occur under the control of a macroscopic observer, and changes in entropy within the system are inaccessible to a macroscopic observer. Moreover, “in a thermodynamic process, any flow in phase space that is not controlled by a macroscopic observer reduces information about the state of the microstate and therefore increases entropy” [

3]. Ziegler calls this formulation the phase version of the second law of thermodynamics. The value of this formulation is that it connects the production of entropy with internal microprocesses and statements about “reduction of information” and “non-observability of entropy production” require more detailed consideration and physical understanding.

Reversible entropy changes are always introduced into the system from outside, so they are controllable and can be characterized quantitatively. The production of entropy in a system is almost always characterized qualitatively; it was enough that it was produced, but in what quantity was not determined experimentally. Although H - Boltzmann's theorem is both a qualitative and quantitative characteristic of the entropy produced by the system. It is clear to us now that the H - theorem is of microscopic confirmation of the second law, but at that time the connection between the entropy produced and the H - theorem was not known. When Ziegler spoke about the impossibility of determining an irreversible quantity, he apparently had in mind its experimental determination.

The formalization of the Prigogine and Ziegler criteria is based on the phenomenological representation of entropy production in the form of a product of thermodynamic forces and flows.

This representation of entropy production, as well as the requirement of a linear relationship between them, reduces the generality of the consideration.

Endres also argues that “MEPP appears to contradict the minimum entropy production principle (MinEPP) promoted by Onsager, Prigogine and others” [

19] (p.1). On the other hand, [

8] argues that MEPP and MinEPP cannot be contrasted because they refer to different system states and are executed under different conditions. Each of these principles has its own compelling justification. For example, in [

20] a microscopic derivation of MinEPP is given in the mode of linear response of the system to an external disturbance, and in [

21] an experimental confirmation of MEPP is given. From the above it is clear that both principles are observed in physical systems, for various states [

8], and for which states it will be shown below.

5. MEPP in an Exactly Solvable Model of a Rayleigh Gas with Sources

In [

10], one of the authors, together with prof. Osipov A.I. (MSU) obtained time-dependent (dynamic) expressions for entropy production in open and isolated systems. Dynamic expressions for entropy production will allow you to determine the conditions and processes under which MinEPP and MEPP are performed.

In order to determine the conditions for the implementation of MinEPP and MEPP, analytical solutions are required for an open system in which stationary nonequilibrium states can be realized, and also consider the relaxation of the system from one nonequilibrium state to another nonequilibrium state.

In [

5], we obtained a solution to the Fokker–Planck equation with sources, i.e. for an open system. Let us use the results of [

5] to analyze the conditions for the implementation of MinEPP and MEPP.

To analyze the Ziegler principle, let us consider the relaxation of the initial equilibrium distribution function of Rayleigh particles into the final nonequilibrium stationary distribution under the influence of external sources of particles. As an external source, we will choose a δ-shaped source of heavy particles. This source introduces monoenergetic heavy particles with energy x

0 into the system, which, then colliding with thermostat particles, form the current distribution function. To prevent particles from accumulating in the system, we will introduce a “chemical” reaction to remove particles from the thermalized system with the current DF. The Fokker–Planck equation in this case has the form

with initial and boundary conditions (3), where x

0 = ε

0 /

kT

L – dimensionless energy of particles

δ – source,

ϕ(x) = – initial equilibrium distribution function,

ε0 – energies of particles δ – source, k – Boltzmann constant, n

0 - the initial number of particles, K - is the chemical reaction constant and η - is the power of the δ source. For this model, we obtained an analytical solution in the form of an expansion in Laguerre polynomials and showed the entropy balance in [

9]. Provided that the number of particles is balanced

n0 = η/K, with the initial equilibrium DF, this solution has the form

Having defined the entropy according to Boltzmann in the form (5) for the change in entropy, we obtain (6). Substituting (11) into (6) we have

By calculating the contributions to the change in entropy from the Fokker–Planck operator, the chemical reaction and the δ source, they were obtained in [

5]. Here we are interested in the contribution to the change in entropy from the Fokker–Planck term, namely

As noted above, the Fokker–Planck equation was derived from the collision integral of the Boltzmann equation. Therefore, the term from the Fokker–Planck equation in the change in entropy contains the production of entropy. As can be seen from (14), this change in entropy consists of two parts: the first is a reversible change in entropy due to the removal (at

x0 > 3/2) of energy into the thermostat; the second is the irreversible production of entropy

In a steady state, the Fokker–Planck operator provides a constant flow of entropy into the thermostat (for

x0 > 3/2) and constantly produces entropy. As can be seen (16), the entropy production of a stationary state is a convex function of time and each point σ(τ) is a local maximum, and σ(∞) is an absolute maximum, equal to

Thus, during relaxation from an equilibrium state to a nonequilibrium stationary state, the production of entropy, in accordance with the Ziegler principle, is maximum

6. Discussion

When a nonequilibrium isolated system relaxes into an equilibrium state, as shown here, the entropy production is minimal. This means, that in an isolated system, Prigogine’s theorem is satisfied in both linear and nonlinear thermodynamics, since we did not introduce thermodynamic flows and forces, and therefore there is no requirement for a linear connection between them.

In an open system, during relaxation from an equilibrium state to a nonequilibrium state, the entropy production is maximal. If the relaxation of a nonequilibrium isolated system to an equilibrium state is called free relaxation, then MinEPP is satisfied during free relaxation. Accordingly, relaxation from an equilibrium state to a nonequilibrium state can be called forced relaxation, then MEPP is satisfied during forced relaxation. Thus, the equilibrium state of the system in the phase space of states of the system is a point of attraction for all nonequilibrium states [

8]. This is an essential aspect of this problem, emphasized by Planck [

22].

It should be noted that MinEPP is also satisfied in the case of relaxation of the system from a state far from equilibrium (with lower entropy) to a state close to equilibrium (with higher entropy), i.e. during relaxation from one nonequilibrium state to another (see paragraph 3). In such processes, the production of entropy fully satisfies the conditions of minimum production according to Prigogine. Similarly, MEPP is satisfied by relaxation from a state close to equilibrium (with more entropy) to a state far from equilibrium (with less entropy).