Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

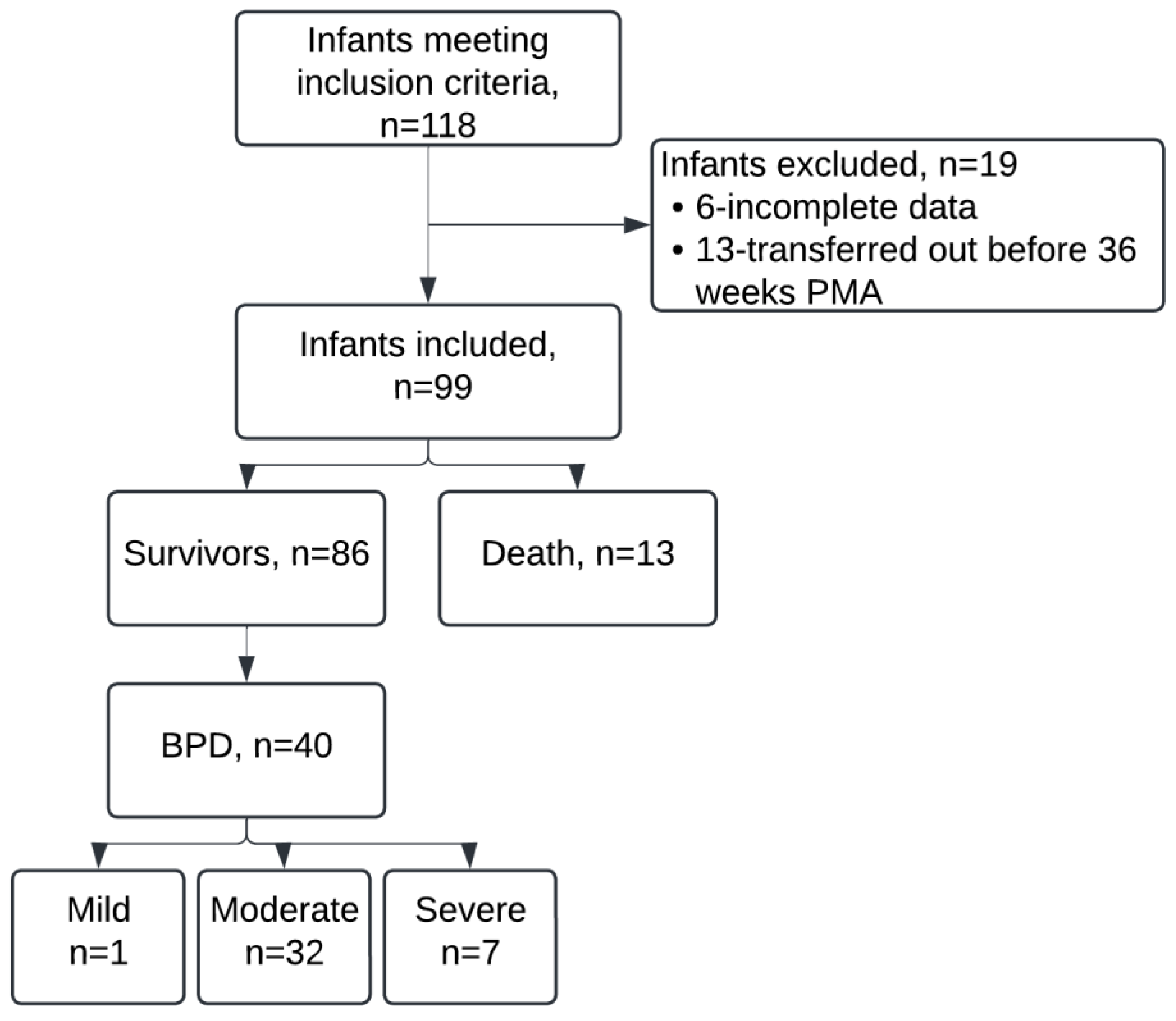

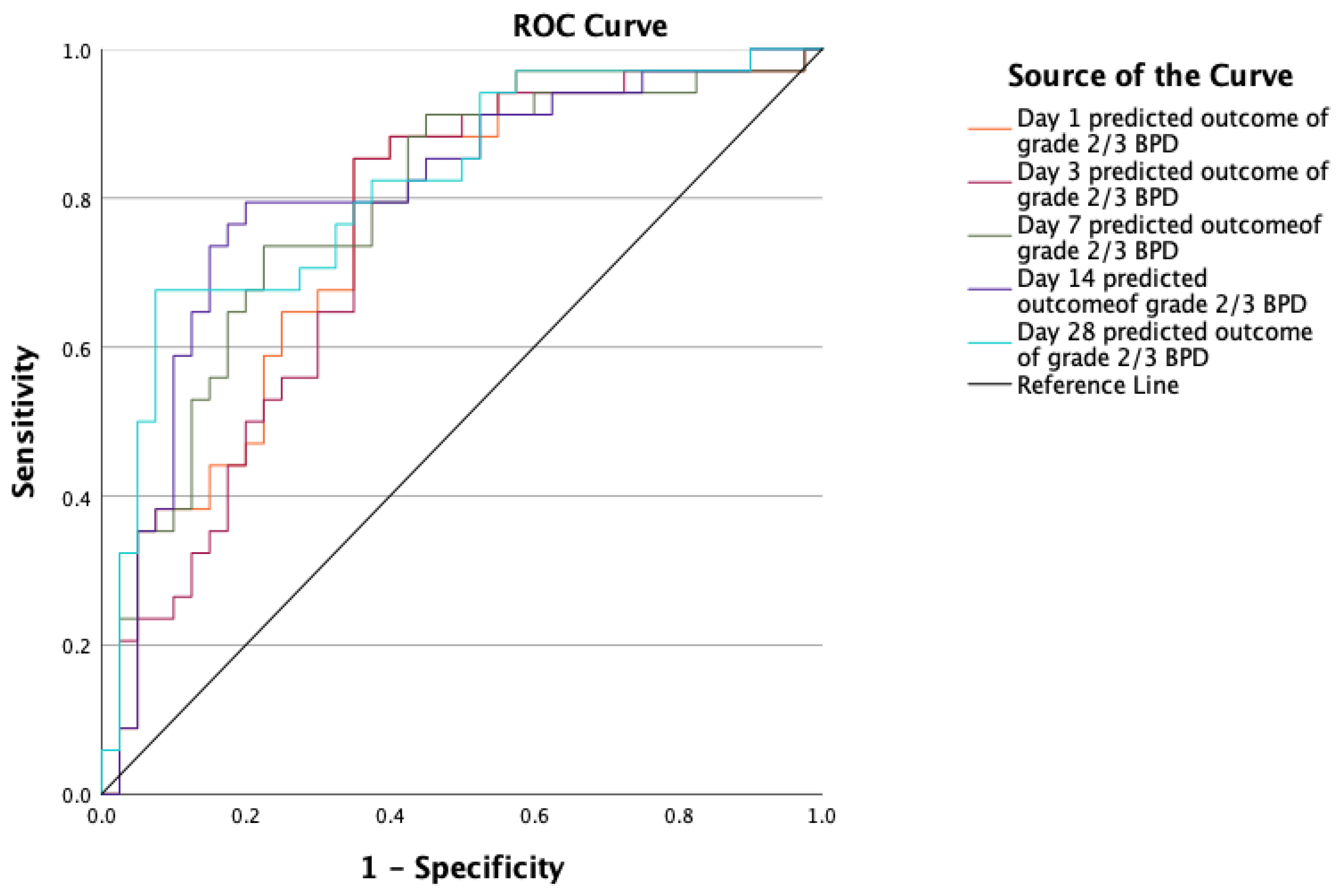

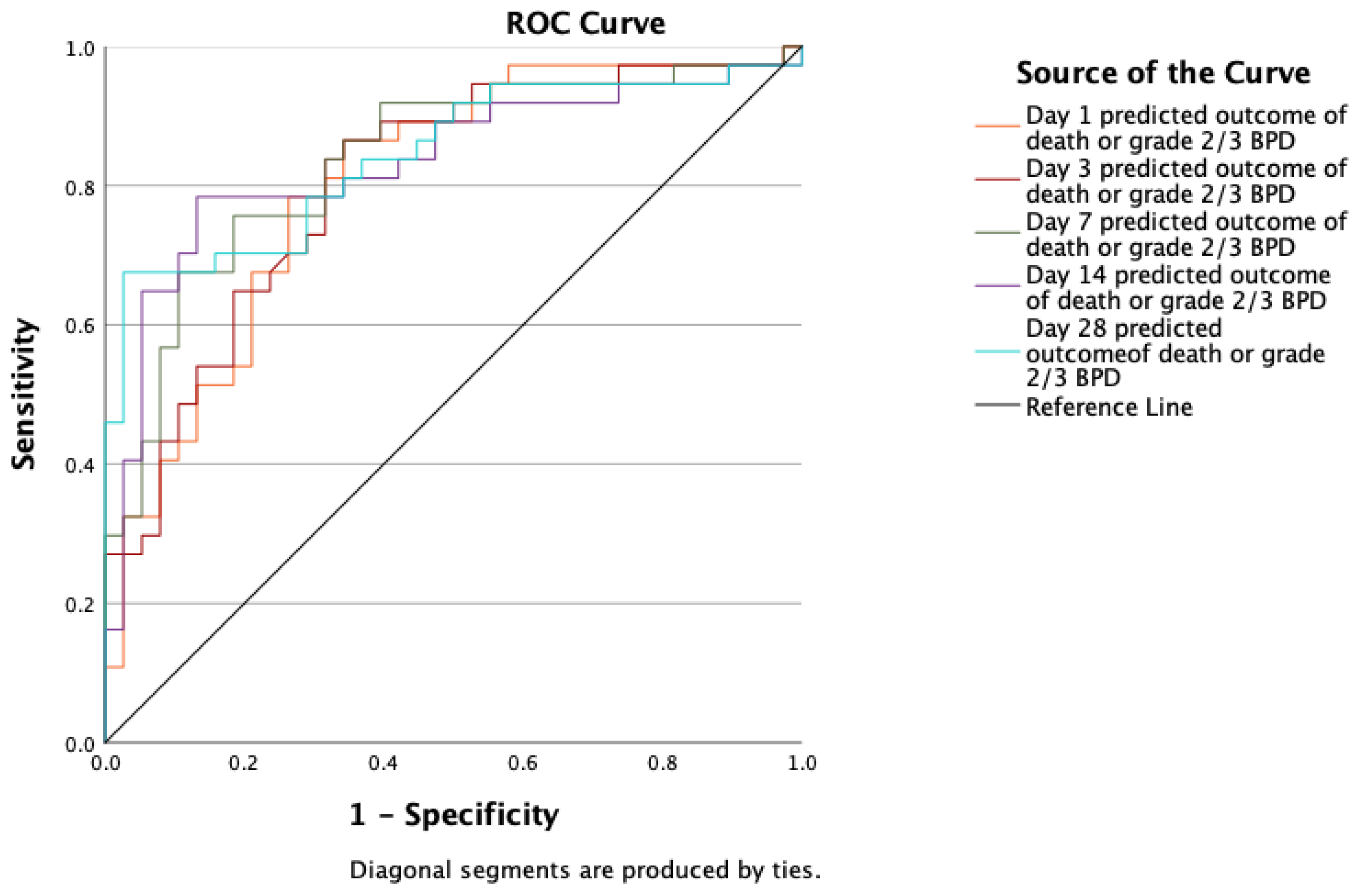

Background/Objectives: The numerical risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and/or death could be estimated using the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) BPD outcome estimator 2022 in extremely low gestational age (ELGA) infants during the first 4 weeks of life to facilitate prognostication, and centre specific targeted improvement interventions. However, 2022 NICHD BPD outcome estimator’s performance in Canadian setting has not been validated. Our objective is to validate the NICHD BPD outcome estimator 2022 in predicting death and or moderate to severe BPD at 36 weeks in less than 29 weeks infants admitted to NICU. Methods: A retrospective observational study (March 2022–August 2023) was conducted on both inborn and outborn preterm infants excluding neonates with major congenital anomalies. Infants were classified into five groups based on the predicted risk of death or moderate-to-severe BPD (<10%, 10-20%, 20-30%, 30-40%, ≥50%) followed by noting observed outcomes from unit’s database. A Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve was used to assess the accuracy of the NICHD BPD outcome estimator 2022, with an area under curve (AUC) >0.7 defined a priori as an acceptable predictive accuracy for local use. Results: Among 99 infants included, 13 (13.1%) died, and 40 (40.4%) developed BPD. Median gestational age was 26 weeks, and median birth weight was 914 grams. Twenty-three infants (23.2%) received postnatal steroids. The AUC values for death or moderate to severe BPD on days 1, 3, 7, 14, and 28 were 0.803, 0.806, 0.837, 0.832, and 0.843, respectively. The AUC values for moderate to severe BPD alone on those days were 0.766, 0.746, 0.785, 0.807 and 0.818 respectively. Conclusions: The 2022 BPD estimator accurately predicted the death and /or moderate to severe BPD on Days 1, 3, 7, 14 and 28 of life. This tool could serve as a valid adjunct to facilitate discussion between clinicians and families on initiating time-sensitive targeted interventions to prevent or alter the course of BPD.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Respiratory Support

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jobe, A.H.; Bancalari, E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2001, 163, 1723-1729. [CrossRef]

- CNN. Annual Report. https://www.canadianneonatalnetwork.org/portal/Portals/0/Annual%20Reports/2022%20CNN%20Annual%20Report.pdf. 2022.

- Parikh, S.; Reichman, B.; Kusuda, S.; Adams, M.; Lehtonen, L.; Vento, M.; Norman, M.; Laura; Isayama, T.; Hakansson, S.; et al. Trends, Characteristic, and Outcomes of Preterm Infants Who Received Postnatal Corticosteroid: A Cohort Study from 7 High-Income Countries. Neonatology 2023, 120, 517-526. [CrossRef]

- Alagappan, A.; Malloy, M.H. Systemic hypertension in very low-birth weight infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: incidence and risk factors. 1998.

- Vyas-Read, S.; Varghese, N.P.; Suthar, D.; Backes, C.; Lakshminrusimha, S.; Petit, C.J.; Levy, P.T. Prematurity and Pulmonary Vein Stenosis: The Role of Parenchymal Lung Disease and Pulmonary Vascular Disease. 2022.

- Malloy, K.W.; Austin, E.D. Pulmonary hypertension in the child with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Pulmonol 2021, 56, 3546-3556. [CrossRef]

- Lagatta, J.; Murthy, K.; Zaniletti, I.; Bourque, S.; Engle, W.; Rose, R.; Ambalavanan, N.; Brousseau, D. Home Oxygen Use and 1-Year Readmission among Infants Born Preterm with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia Discharged from Children's Hospital Neonatal Intensive Care Units. 2020.

- Manti, S.; Galdo, F.; Parisi, G.F.; Napolitano, M.; Decimo, F.; Leonardi, S.; Miraglia Del Giudice, M. Long-term effects of bronchopulmonary dysplasia on lung function: a pilot study in preschool children's cohort. J Asthma 2021, 58, 1186-1193. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, E.G.; Clouse, B.J.; Hasenstab, K.A.; Sitaram, S.; Malleske, D.T.; Nelin, L.D.; Jadcherla, S.R. Infant Pulmonary Function Testing and Phenotypes in Severe Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Pediatrics / 2018, 141. [CrossRef]

- Majnemer, A.; Riley, P.; Shevell, M.; Birnbaum, R.; Greenstone, H.; Coates, A.L. Severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia increases risk for later neurological and motor sequelae in preterm survivors. Dev Med Child Neurol 2000, 42, 53-60. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.C.; Morris, B.H.; Wrage, L.A.; Vohr, B.R.; Poole, W.K.; Tyson, J.E.; Wright, L.L.; Ehrenkranz, R.A.; Stoll, B.J.; Fanaroff, A.A.; et al. Extremely low birthweight neonates with protracted ventilation: mortality and 18-month neurodevelopmental outcomes. J Pediatr 2005, 146, 798-804. [CrossRef]

- Short, E.J.; Kirchner, H.L.; Asaad, G.R.; Fulton, S.E.; Lewis, B.A.; Klein, N.; Eisengart, S.; Baley, J.; Kercsmar, C.; Min, M.O.; et al. Developmental sequelae in preterm infants having a diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia: analysis using a severity-based classification system. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007, 161, 1082-1087. [CrossRef]

- Short, E.J.; Klein, N.K.; Lewis, B.A.; Fulton, S.; Eisengart, S.; Kercsmar, C.; Baley, J.; Singer, L.T. Cognitive and academic consequences of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and very low birth weight: 8-year-old outcomes. Pediatrics 2003, 112, e359. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease, C.; Prevention. Economic costs associated with mental retardation, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, and vision impairment--United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004, 53, 57-59.

- Htun, Z.T.; Schulz, E.V.; Desai, R.K.; Marasch, J.L.; McPherson, C.C.; Mastrandrea, L.D.; Jobe, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Postnatal steroid management in preterm infants with evolving bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol 2021, 41, 1783-1796. [CrossRef]

- Barrington, K.J. The adverse neuro-developmental effects of postnatal steroids in the preterm infant: a systematic review of RCTs. BMC pediatrics. 2001, 1, 1. [CrossRef]

- Lemyre, B.; Dunn, M.; Thebaud, B. Postnatal corticosteroids to prevent or treat bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants. Paediatr Child Health 2020, 25, 322-331. [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.J.; Pramanik, A.K.; FETUS, C.O.; NEWBORN. Postnatal Corticosteroids to Prevent or Treat Chronic Lung Disease Following Preterm Birth. Pediatrics 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sweet, D.G.; Carnielli, V.; Greisen, G.; Hallman, M.; Ozek, E.; Te Pas, A.; Plavka, R.; Roehr, C.C.; Saugstad, O.D.; Simeoni, U.; et al. European Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Respiratory Distress Syndrome - 2019 Update. Neonatology 2019, 115, 432-450. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, E.A.; Wiener, L.E.; Rysavy, M.A.; Dysart, K.C.; Gantz, M.G.; Eichenwald, E.C.; Greenberg, R.G.; Harmon, H.M.; Laughon, M.M.; Watterberg, K.L.; et al. Assessment of Corticosteroid Therapy and Death or Disability According to Pretreatment Risk of Death or Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Extremely Preterm Infants. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2312277. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.W.; Mainzer, R.; Cheong, J.L.Y. Systemic Postnatal Corticosteroids, Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia, and Survival Free of Cerebral Palsy. JAMA pediatrics. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kanagaraj, U.; Tan, J.; Soraisham, A.; Lodha, A.; Shah, P.; Kulkarni, T.; Shivananda, S. Postnatal Steroids Use for Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in a Quaternary Care NICU. Am J Perinatol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, R.G.; McDonald, S.A.; Laughon, M.M.; Tanaka, D.; Jensen, E.; Van Meurs, K.; Eichenwald, E.; Brumbaugh, J.E.; Duncan, A.; Walsh, M.; et al. Online clinical tool to estimate risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2022. [CrossRef]

- Laughon, M.M.; Langer, J.C.; Bose, C.L.; Smith, P.B.; Ambalavanan, N.; Kennedy, K.A.; Stoll, B.J.; Buchter, S.; Laptook, A.R.; Ehrenkranz, R.A.; et al. Prediction of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia by Postnatal Age in Extremely Premature Infants. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2011, 183, 1715-1722. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, E.A.; Dysart, K.; Gantz, M.G.; McDonald, S.; Bamat, N.A.; Keszler, M.; Kirpalani, H.; Laughon, M.M.; Poindexter, B.B.; Duncan, A.F.; et al. The Diagnosis of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Very Preterm Infants. An Evidence-based Approach. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019, 200, 751-759. [CrossRef]

- Onland, W.; Cools, F.; Kroon, A.; Rademaker, K.; Merkus, M.P.; Dijk, P.H.; Van Straaten, H.L.; Te Pas, A.B.; Mohns, T.; Bruneel, E.; et al. Effect of Hydrocortisone Therapy Initiated 7 to 14 Days After Birth on Mortality or Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia Among Very Preterm Infants Receiving Mechanical Ventilation. JAMA 2019, 321, 354. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.W.; Davis, P.G.; Morley, C.J.; McPhee, A.; Carlin, J.B.; Investigators, D.S. Low-dose dexamethasone facilitates extubation among chronically ventilator-dependent infants: a multicenter, international, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 75-83. [CrossRef]

- Dugas, M.A.; Nguyen, D.; Frenette, L.; Lachance, C.; St-Onge, O.; Fougeres, A.; Belanger, S.; Caouette, G.; Proulx, E.; Racine, M.C.; et al. Fluticasone inhalation in moderate cases of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics 2005, 115, e566-572. [CrossRef]

- Arnon, S.; Grigg, J.; Silverman, M. Effectiveness of budesonide aerosol in ventilator-dependent preterm babies: a preliminary report. Pediatr Pulmonol 1996, 21, 231-235. [CrossRef]

- CNN. Abstractor's Manual. 2024, 107.

- David W. Hosmer, S.L. Assessing the Fit of the Model. In Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd Ed ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, 2000; pp. 160-164.

- Romijn, M.; Dhiman, P.; Finken, M.J.J.; van Kaam, A.H.; Katz, T.A.; Rotteveel, J.; Schuit, E.; Collins, G.S.; Onland, W.; Torchin, H. Prediction Models for Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Infants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr 2023, 258, 113370. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, T.C.; Batey, N.; Luu, K.L.; Prayle, A.; Sharkey, D. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia prediction models: a systematic review and meta-analysis with validation. Pediatr Res 2023, 94, 43-54. [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.K.; Davis, P.G. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia outcome estimator in current neonatal practice. Acta Paediatrica 2021, 110, 166-167. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Mascarenhas, D.; Nanavati, R. Risk Calculator for Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Neonates: A Prospective Observational Study. Indian J Pediatr 2024, 91, 781-787. [CrossRef]

- Srivatsa, B.; Srivatsa, K.R.; Clark, R.H. Assessment of validity and utility of a bronchopulmonary dysplasia outcome estimator. Pediatr Pulmonol 2023, 58, 788-793. [CrossRef]

- Kinkor, M.; Schneider, J.; Sulthana, F.; Noel-Macdonnell, J.; Cuna, A. A Comparison of the 2022 Versus 2011 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Web-Based Risk Estimator for Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. J Pediatr Clin Pract 2024, 14, 200129. [CrossRef]

- Cuna, A.; Lagatta, J.M.; Savani, R.C.; Vyas-Read, S.; Engle, W.A.; Rose, R.S.; DiGeronimo, R.; Logan, J.W.; Mikhael, M.; Natarajan, G.; et al. Association of time of first corticosteroid treatment with bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants. Pediatr Pulmonol 2021, 56, 3283-3292. [CrossRef]

- Cuna, A.; Lewis, T.; Dai, H.; Nyp, M.; Truog, W.E. Timing of postnatal corticosteroid treatment for bronchopulmonary dysplasia and its effect on outcomes. Pediatr Pulmonol 2019, 54, 165-170. [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V.V.; Bandyopadhyay, T.; Nanda, D.; Bandiya, P.; Ahmed, J.; Garg, A.; Roehr, C.C.; Nangia, S. Assessment of Postnatal Corticosteroids for the Prevention of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Neonates: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2021, 175, e206826. [CrossRef]

- Harmon, H.M.; Jensen, E.A.; Tan, S.; Chaudhary, A.S.; Slaughter, J.L.; Bell, E.F.; Wyckoff, M.H.; Hensman, A.M.; Sokol, G.M.; DeMauro, S.B. Timing of postnatal steroids for bronchopulmonary dysplasia: association with pulmonary and neurodevelopmental outcomes. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association 2020, 40, 616-627. [CrossRef]

| Gestational age at birth, weeks | 26(25-28) |

| 22-24 weeks | 18(18.2) |

| 25-26 weeks | 38(38.4) |

| 27-28 weeks | 43(43.4) |

| Birth weight, grams, | 914(755-1069) |

| Male | 57(57.6) |

| Outborn | 22(22.2) |

| Antenatal betamethasone (Partial or complete) | 86(86.9) |

| Suspected Chorioamnionitis | 24(24.2) |

| C-Section delivery | 68(68.7) |

| APGAR 1 min, | 5(2-,6) |

| APGAR 5 min, | 6(6- 8) |

| Intubation and Ventilation during resuscitation | 62(62.6) |

| SNAPPE II1, | 27(18- 42) |

| SNAPPE II1 > 20 | 60(60.6) |

| Variable | n(%) |

|---|---|

| Mortality | 13(13.1) |

| Moderate or severe BPD | 40(40.4) |

|

32(32.3) |

|

7(7.1) |

| ROP Stage ≥ 3 right or left | 33(33.3) |

| ROP treated, right or left | 8(8.8) |

| PDA treated (medical or surgical) | 42(42.4) |

| Pneumothorax | 5(5.1) |

| Surgical NEC | 14(14.1) |

| IVH Grade ≥ 3 | 29(29.3) |

| PVL grade >2 | 9(9.1) |

| Spontaneous intestinal perforation | 3(3.0) |

| Discharge-Survival without major morbidity1 | 25(25.3) |

| Discharge Oxygen | 2(2.3) |

| Discharge Monitor | 46(53.5) |

| Discharge ostomy | 11(12.8) |

| Discharge gavage | 37(43.0) |

| Discharge Tracheostomy | 1(1.2) |

| Discharge Gastrostomy | 11(12.8) |

| Discharge Non-invasive ventilation | 3(3.5) |

| Discharge Continuous positive airway pressure | 3(3.5) |

| Discharge-Technology dependency2 | 55(64.0) |

| Variable | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 28 | At 36 weeks PMA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fio2≥ 22% | 37/87 (42.5) | 49/87 (56.3) | 54/89 (60.7) | 57/85 (67.1) | 48/82 (58.5) | 15/86 (17.4) | |

| Fio2, median (IQR) | 21 (21,25.75) | 23 (21,26) | 23 (21,30) | 26.5 (21,34) | 24 (21,30) | 21 (21,25.5) | |

| Respiratory support | HFV | 12/87 (13.8) | 17/87 (19.5) | 24/89 (27) | 20/85 (23.5) | 15/82 (18.3) | 5/86 (5.8) |

| CMV | 43/87 (49.4) | 29/87 (33.3) | 17/89 (19.1) | 13/85 (15.2) | 6/82 (7.3) | 2/86 (2.3) | |

| NIPPV | 7/87 (8) |

22/87 (25.3) | 25/89 (28.1) | 22/85 (25.9) | 30/82 (36.6) | 4/86 (4.6) | |

| CPAP | 24/87 (27.6) | 18/87 (20.7) | 22/89 (24.7) | 28/85 (33) | 16/82 (19.5) | 13/86 (15.1) | |

| HFNC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/85 (1.2) | 11/82 (13.4) | 15/86 (17.4) | |

| LFNC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/86 (1.2) | |

| No respiratory support | 1/87 (1.2) | 1/87 (1.2) | 1/89 (1.1) | 1/85 (1.2) | 4/82 (4.9) | 46/86 (53.5) | |

| Estimated risk of Grade 2/3 BPD using the calculator | AUC | 95% CI for AUC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10% | 10-19% | 20-29% | 30-39% | 40-49% | ≥50% | |||

| Day 1 (n=87) | 4/25 (16%) | 7/20 (35%) | 8/17 (47.1%) | 11/17 (64.7%) | 4/7 (57.1%) | 0/1 | 0.766 | 0.657-0.875 |

| Day 3 (n=87) | 2/24 (8.3%) | 8/17 (47.1%) | 10/20 (50%) | 5/11 (45.5%) | 2/6 (33.3%) | 7/9 (77.8%) | 0.746 | 0.633-0.860 |

| Day 7 (n=89) | 3/25 (12%) | 6/20 (30%) | 6/10 (60%) | 7/11 (63.6%) | 10/18 (55.6%) | 3/5 (60%) | 0.785 | 0.678-0.891 |

| Day 14 (n=85) | 3/23 (13%) | 9/26 (34.6%) | 2/3 (66.7%) | 7/10 (70%) | 4/10 (40%) | 11/13 (84.6%) | 0.807 | 0.703-0.911 |

| Day 28 (n=82) | 2/20 (10%) | 9/29 (31%) | 9/12 (75%) | 2/2 (100%) | 1/2 (50%) | 15/17 (88.2%) | 0.818 | 0.720-0.916 |

| Estimated risk of death or Grade 2/3 BPD using the calculator | AUC | 95% CI for AUC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10% | 10-19% | 20-29% | 30-39% | 40-49% | ≥50% | |||

| Day 1 (n=87) | 2/21 (9.5%) | 5/15 (33.3%) | 9/14 (64.3%) | 9/12 (75%) | 7/11 (63.6%) | 13/14 (92.9%) | 0.803 | 0.703-0.903 |

|

Day 3 (n=87) |

2/23 (8.7%) | 6/16 (37.5%) | 9/14 (64.3%) | 7/10 (70%) | 6/8 (75%) | 14/16 (87.5%) | 0.806 | 0.707-0.905 |

| Day 7 (n=89) | 2/19 (10.5%) | 6/19 (31.6%) | 6/13 (46.2%) | 8/10 (80%) | 6/7 (85.7%) | 19/21 (90.5%) | 0.837 | 0.745-0.930 |

| Day 14 (n=85) | 2/20 (10%) | 5/23 (21.7%) | 5/7 (71.4%) | 4/6 (66.7%) | 9/10 (90%) | 16/19 (84.2%) | 0.832 | 0.734-0.930 |

| Day 28 (n=82) | 2/20 (10%) | 9/27 (33.3%) | 8/12 (66.7%) | 2/3 (66.7%) | 2/2 (100%) | 17/18 (94.4%) | 0.843 | 0.751-0.935 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).