Submitted:

25 January 2024

Posted:

26 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

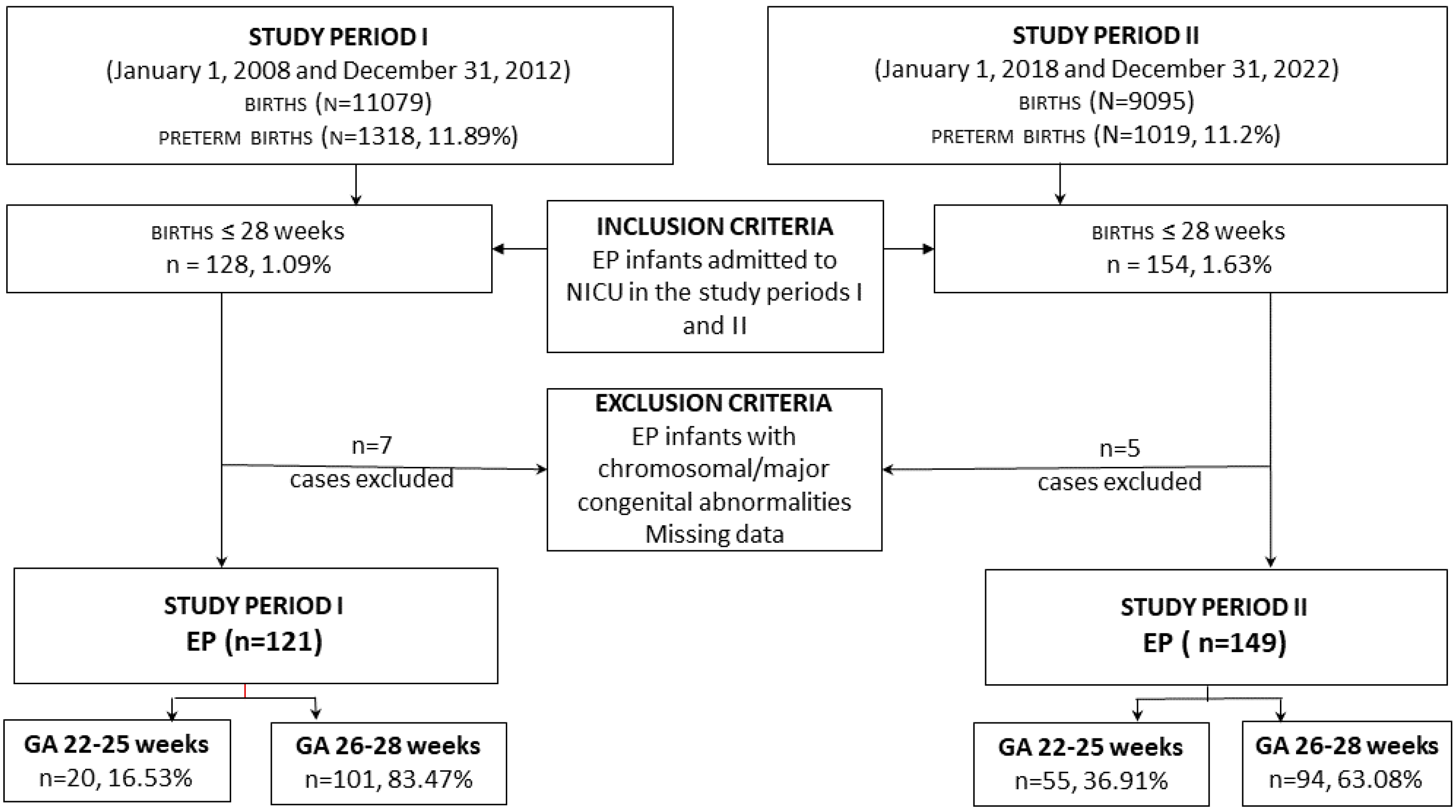

2.1. Study group. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.2. Study design and data acquisition

2.3. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline demographic characteristics

3.2. Delivery room stabilization

3.3. RDS management (surfactant and mechanical ventilation)

3.3.1. Surfactant

3.3.2. Mechanical ventilation

3.4. Outcomes (survival/deaths and morbidities)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kong X, Xu F, Wu R, et al. Neonatal mortality and morbidity among infants between 24 to 31 complete weeks: a multicenter survey in China from 2013 to 2014. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16(1):174. [CrossRef]

- Anderson JG, Baer RJ, Partridge JC, et al. Survival and Major Morbidity of Extremely Preterm Infants: A Population-Based Study. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20154434. [CrossRef]

- Lundgren p, Morsin, E, Hård A-L, et al. National cohort of infants born before 24 gestational weeks showed increased survival rates but no improvement in neonatal morbidity. Acta Paediatr. 2022; 111: 1515– 1525.

- Siffel C, Hirst AK, Sarda SP, Kuzniewicz MW, Li DK. The clinical burden of extremely preterm birth in a large medical records database in the United States: Mortality and survival associated with selected complications. Early Hum Dev. 2022;171:105613. [CrossRef]

- Bell EF, Hintz SR, Hansen NI, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Mortality, In-Hospital Morbidity, Care Practices, and 2-Year Outcomes for Extremely Preterm Infants in the US, 2013-2018. JAMA. 2022;327(3):248-263.

- Edstedt Bonamy AK, Zeitlin J, Piedvache A, et al. Epice Research Group. Wide variation in severe neonatal morbidity among very preterm infants in European regions. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019;104(1):F36-F45. [CrossRef]

- Perkins GD, Neumar R, Monsieurs KG, et al; International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation-Review of the last 25 years and vision for the future. Resuscitation. 2017;121:104-116. [CrossRef]

- Kattwinkel J, Niermeyer S, Nadkarni V, et al. Resuscitation of the newly born infant: an advisory statement from the Pediatric Working Group of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 1999;40(2):71-88. [CrossRef]

- Phillips B, Zideman D, Wyllie J, Richmond S, van Reempts P; European Resuscitation Council. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2000 for Newly Born Life Support. A statement from the Paediatric Life Support Working Group and approved by the Executive Committee of the European Resuscitation Council. Resuscitation. 2001;48(3):235-9. [CrossRef]

- International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) consensus on science with treatment recommendations for pediatric and neonatal patients: pediatric basic and advanced life support. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):e955-77. [CrossRef]

- American Heart Association. 2005 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) of pediatric and neonatal patients: pediatric basic life support. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):e989-1004. [CrossRef]

- Tan A, Schulze A, O'Donnell CP, Davis PG. Air versus oxygen for resuscitation of infants at birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 200;2005(2):CD002273.

- Saugstad, OD. Oxygen toxicity at birth: the pieces are put together. Pediatr Res 2003; 789–783. [CrossRef]

- Saugstad OD, Vento M, Ramji S, Howard D, Soll RF. Neurodevelopmental outcome of infants resuscitated with air or 100% oxygen: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neonatology. 2012;102(2):98-103. [CrossRef]

- Wyllie J, Bruinenberg J, Roehr CC, Rüdiger M, Trevisanuto D, Urlesberger B. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 7. Resuscitation and support of transition of babies at birth. Resuscitation. 2015 Oct;95:249-63.

- Aziz K, Lee CHC, Escobedo MB, et al. Part 5: Neonatal Resuscitation 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Pediatrics 2021;147(Suppl 1). e2020038505E. [CrossRef]

- Yamada NK, Szyld E, Strand ML, et al. American Heart Association and American Academy of Pediatrics. 2023 American Heart Association and American Academy of Pediatrics Focused Update on Neonatal Resuscitation: An Update to the American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2024;149(1):e157-e166. [CrossRef]

- Sweet D, Bevilacqua G, Carnielli V, et al. Working Group on Prematurity of the World Association of Perinatal Medicine; European Association of Perinatal Medicine. European consensus guidelines on the management of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. J Perinat Med. 2007;35(3):175-86.

- Sweet DG, Carnielli VP, Greisen G, et al. European Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Respiratory Distress Syndrome: 2022 Update. Neonatology. 2023;120(1):3-23. [CrossRef]

- Jensen EA, Dysart K, Gantz, M.G. The diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very preterm infants: An evidence-based approach. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 2019;200: 751–759. [CrossRef]

- Engle WA; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Age terminology during the perinatal period. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1362-1364.

- Papile, LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: A study of infants with birth weights less than 1500 gm. J. Pediatr. 1978;92:529–534. [CrossRef]

- Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann. Surg. 1978; 187:1.

- Gillam-Krakauer M, Reese J. Diagnosis and Management of Patent Ductus Arteriosus. Neoreviews. 2018;19:e394–e402. [CrossRef]

- Hong EH, Shin YU, Cho H. Retinopathy of prematurity: a review of epidemiology and current treatment strategies. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2022;65(3):115-126. [CrossRef]

- Hayes R, Hartnett J, Semova G, et al. Infection, Inflammation, Immunology and Immunisation (I4) section of the European Society for Paediatric Research (ESPR). Neonatal sepsis definitions from randomised clinical trials. Pediatr Res. 2023;93(5):1141-1148.

- Higgins BV, Baer RJ, Steurer MA, Karvonen KL, Oltman SP, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL, Rogers EE. Resuscitation, survival and morbidity of extremely preterm infants in California 2011-2019. J Perinatol. 2023 Sep 9.

- Fogarty M, Osborn DA, Askie L, et al. Delayed vs early umbilical cord clamping for preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(1):1-18. [CrossRef]

- Yoon SJ, Lim J, Han JH et al. Impact of neonatal resuscitation changes on outcomes of very-low-birth-weight infants. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9003. [CrossRef]

- Kavurt S, Baş AY, İşleyen F, Durukan Tosun M, Ulubaş Işık D, Demirel N. Short-term outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants in a tertiary neonatal intensive care unit in Türkiye. Turk J Pediatr. 2023;65(3):377-386. [CrossRef]

| Period I (2008–2012) | Period II (2018–2022) | |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery room respiratory management | ||

| Neonatal resuscitation algorithm | 2005/2010 | 2015/2020 |

| Delayed cord clamping | No | In infants who do not require extensive resuscitation |

| FiO2 for initiating resuscitation | 100% (<100% since 2011) | 30–100% |

| SpO2 (%) at 5 min | No target SpO2 | Target SpO2 80–85% |

| PPV | Elective | Non-breathing preterm infants |

| nCPAP (alveolar recruitment) | No/yes, since 2012, PEEP 5 cmH2O | Yes, PEEP > 6 cm H2O |

| Intubation in the delivery room | Elective intubation | When needed |

| RDS management | ||

| Antenatal steroids | Yes | Yes |

| Surfactant prophylaxis | Yes | Only in the special situation |

| Rescue Surfactant | Yes | Early rescue - the first option |

| Dose of surfactant | 100–200 mg/kg | 200 mg/kg |

| Surfactant delivery | Conventional/INSURE | LISA/INSURE |

| nCPAP | after MV | First intention |

| MV modes | Conventional, HFOV | Lung protective ventilation TVT |

| Caffeine | No | Yes |

| Study Group (n = 270) | p‒value | OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period I 2008–2012 (n = 121) (n = 20; 22–25 w) (n = 101; 26–28 w) |

Period II 2018–2022 (n = 149) (n = 55; 22–25 w) (n = 94; 26–28 w) |

|||

|

Male (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

51/42.1 6/30.0 45/44.6 |

86/57.7 32/58.2 54/57.4 |

0.011* 0.031* 0.773 |

1.41(1.08–1.85) 2.39 (1.03–2.56) 1.28 (0.98–1.89) |

|

GA, weeks median (IQR) ‡ 22–25 w 26–28 w |

27 (26–28) 25 (25–25) 27 (26–28) |

26 (25–27.5) 24 (24–25) 27 (26–28) |

<0.001* <0.001* 0.814 |

- |

|

BW, g, median (IQR) ‡ 22–25 w 26–28 w |

880 (750–960) 650 (512.5–797.5) 900 (800–980) |

800 (650–990) 620 (590–700) 950 (800–1000) |

0.114 0.488 0.190 |

- |

|

SGA, (N/%) † 22–25 w 26–28 w |

20/16.5 6/30.0 14/13.9 |

18/12.1 1/1.8 17/18.1 |

0.298 <0.001* 0.423 |

0.83 (0.59–1.16) 0.24 (0.14–0.42) 1.17 (0.78–1.78) |

|

Singleton (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

113/93.4 18/90.0 95/94.1 |

126/84.6 43/78.2 83/88.3 |

0.024* 0.251 0.156 |

0.38 (0.17–0.90) 0.48 (0.13–185) 0.66 (0.34–1.28) |

|

Outborn (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

28/23.1 1/5.0 27/26.7 |

19/12.8 3/5.5 16/17.0 |

0.025* 0.939 0.103 |

0.69 (0.48–0.99) 1.02 (0.57–1.83) 0.72 (0.48–1.10) |

|

Inborn (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

93/76.9 19/95.0 74/73.3 |

130/87.2 52/94.5 78/83.0 |

0.025* 0.939 0.103 |

1.43 (1.08–1.89) 0.94 (0.16–5.32) 1.29 (0.97–1.71 |

|

Prenatal care (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

17/14.0 4/20.0 13/12.9 |

91/61.1 27/49.4 64/68.1 |

<0.001* 0.024* <0.001* |

4.08(2.60–6.40) 2.82(1.04–7.62) 4.42(2.66–7.33) |

|

Maternal hypertension (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

32/26.4 8/40.0 24/23.8 |

13/8.7 2/3.6 11/11.7 |

<0.001* <0.001* 0.028* |

0.56(0.43–0.71) 0.23(0.13–0.42) 0.70(0.53–0.92) |

|

Maternal diabetes (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

6/5.0 1/5.0 5/5.0 |

4/2.7 0/0 4/4.3 |

0.327 0.098 0.818 |

0.72(0.44–1.24) - 0.93(0.51–1.69) |

|

Chorioamnionitis (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

10/8.3 4/20.0 6/5.9 |

15/10.1 7/12.7 8/8.6 |

0.601 0.438 0.477 |

1.14(0.69–1.87) 0.67(0.28–1.67) 1.23 (0.66–2.29) |

|

Prenatal steroids (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

66/54.5 11/55.0 55/54.5 |

91/61.1 32/58.2 59/62.8 |

0.281 0.809 0.242 |

1.16 (0.89–1.51) 1.10 (0.52–2.33) 1.18 (0.90–1.54) |

|

Tocolysis (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

17/14.0 5/25.0 12/11.9 |

26/17.4 10/18.2 16/17.0 |

0.450 0.520 0.339 |

1.16 (0.78–1.72) 0.75 (0.32–1.73) 1.24 (0.79–1.95) |

|

PROM > 18 hours (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

35/28.9 5/25.0 30/29.7 |

45/30.2 19/34.5 26/27.7 |

0.820 0.440 0.754 |

1.03 (0.77–1.39) 1.41 (0.58–3.43) 0.95 (0.71–1.28) |

|

Vaginal delivery (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

81/66.9 13/65.0 68/67.3 |

75/50.3 26/47.3 49/52.1 |

0.006* 0.179 0.030* |

0.67 (0.50–0.90) 0.58 (0.26–1.30) 0.73 (0.54–0.98) |

| Study Group (n = 270) | p‒value | OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period I 2008–2012 (n = 121) (n = 20; 22–25 w) (n = 101; 26–28 w) |

Period II 2018–2022 (n = 149) (n = 55; 22–25 w) (n= 94; 26–28 w) |

|||

|

DCC (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

0/0 0/0 0/0 |

23/15.4 4/7.3 19/20.2 |

<0.001* 0.331 <0.001* |

- |

|

Apgar score 5 min, median (IQR) ‡ 22–25 w 26–28 w |

7 (5–8) 6.5 (6.25–7) 7 (6–8) |

7 (5–8) 5 (4–7) 7.5 (6–8) |

0.883 0.513 0.020* |

- |

|

Cord pH median (IQR) ‡ 22–25 w 26–28 w |

7.21 (6.98–7.30) 7.23 (6.98–7.28) 7.19 (6.98–7.31) |

7.27 (7.12–7.32) 7.21 (7.10–7.28) 7.29 (7.21–7.33) |

0.002* 0.871 <0.001* |

- |

|

FiO2 (%), median (IQR) ‡ 22–25 w 26–28 w |

100 (50–100) 100 (40–100) 100 (50–100) |

40 (30–100) 77.5 (40–100) 40 (30–60) |

<0.001* 0.409 <0.001* |

- |

|

SpO2 (%) 5 min, median (IQR) ‡ 22–25 w 26–28 w |

83 (77.5–88) 80 (69–87.5) 83 (78–88) |

80 (70–86) 75 (67–80) 82 (77.5–88) |

0.004* 0.017* 0.541 |

- |

|

nCPAP ≥ 6cmH2O (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

23/19.0 3/15.0 20/19.8 |

83/55.7 20/36.4 63/67.0 |

<0.001* 0.078 <0.001* |

2.75 (1.87–4.03) 2.51 (0.81–7.72) 3.00 (2.01–4.47) |

|

PPV (N%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

90/74.4 18/90.0 72/71.3 |

74/49.7 45/81.8 29/30.9 |

<0.001* 0.400 <0.001* |

0.53 (0.38–0.74) 0.58 (0.16–2.19) 0.43 (0.31–0.60) |

|

Intubation (delivery room) (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

79/65.3 20/100.0 59/58.4 |

64/43.0 42/76.4 22/23.4 |

<0.001* 0.016* <0.001* |

0.60 (0.45–0.80) - 0.51(0.38–0.67) |

|

HGB (g/dl) at birth median (IQR) ‡ 22–25 w 26–28 w |

15.2 (14.2–16.45) 14.8 (13.65–17.07) 15.3 (14.3–16.45) |

15.5 (14.7–16.65) 15.8 (14.7–16.8) 15.4 (14.67–16.5) |

0.058 0.097 0.346 |

- |

| Study Group (n = 270) | p-value | OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period I 2008–2012 (n = 121) (n = 20; 22–25 weeks) (n = 101; 26–28weeks) |

Period II 2018–2022 (n = 149) (n = 55; 22–25 weeks) (n= 94; 26–28weeks) |

|||

| Surfactant | ||||

|

Surfactant dose (mg/kg), median (IQR)‡ 22–25 w 26–28 w |

100 (100–120) 120 (100–120) 100 (100–120) |

200 (200–200) 200 (200–200) 200 (200–200) |

<0.001* <0.001* <0.001* |

- |

|

Surfactant administration (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

67/55.4 9/45.0 58/57.4 |

133/89.3 54/98.2 79/84.0 |

<0.001* <0.001* <0.001* |

2.30 (1.82–2.91) 6.42 (3.42–12.03) 1.75 (1.37–2.24) |

|

Surfactant prophylaxis (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

25/20.7 6/30.0 19/18.8 |

35/23.5 18/32.7 17/18.1 |

0.580 0.826 0.897 |

1.10 (0.79–1.53) 1.10 (0.48–2.50) 0.98 (0.69–1.38) |

|

Rescue Surfactant (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

42/34.7 3/15.0 39/38.6 |

98/65.8 36/65.5 62/66.0 |

<0.001* <0.001* <0.001* |

2.03 (1.52–2.70) 6.14 (1.96–19.21) 1.71 (1.28–2.27) |

|

Conventional surfactant (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

49/40.5 6/30.0 43/42.6 |

48/32.2 36/65.5 12/12.8 |

0.160 0.006* <0.001* |

0.82 (0.63–1.07) 2.97 (1.28–6.88) 0.53 (0.42–0.67) |

|

INSURE (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

18/14.9 3/15.0 15/14.9 |

26/17.4 8/14.5 18/19.1 |

0.571 0.961 0.426 |

1.11 (0.76–1.63) 0.97 (0.34–2.78) 1.17 (0.78–1.74) |

|

LISA (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

0/0 0/0 0/0 |

59/39.6 10/18.2 49/52.1 |

<0.001* 0.041* <0.001* |

- - - |

|

Caffeine (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

0/0 0/0 0/0 |

149/100.0 55/100.0 94/100.0 |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 |

- - - |

| Mechanical ventilation strategies | ||||

|

Need of MV at 72 h (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

119/98.3 20/100.0 99/98.0 |

87/58.4 51/92.7 36/38.3 |

<0.001 0.221 <0.001 |

0.05 (0.01–0.21) - 0.04 (0.01–0.18) |

|

SIMV(N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

69/58.0 10/50.0 59/59.6 |

49/55.7 20/39.2 28/32.2 |

0.742 0.415 0.042 |

- |

|

HFOV (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

50/42.0 10/50.0 40/40.4 |

39/44.3 31/60.8 8/21.6 |

0.742 0.415 0.042 |

1.04 (0.82–1.32) 1.37 (0.65–2.86) 0.80 (0.66–0.98) |

|

VTV (N/%)† 22–25 w 26–28 w |

0/0 0/0 0/0 |

67/76.1 44/86.3 23/62.2 |

<0.001* <0.001* <0.001* |

- |

|

Duration of MV, hours, median (IQR)‡ 22–25 w 26–28 w |

148 (49–345) 48 (17–172) 196 (73–372) |

220 (72–408) 312 (90–480) 124.5 (35.2–238.5) |

0.299 0.001* 0.072 |

- |

| . | Study Group (n = 270) | p-value | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008–2012 (n = 121) (n = 20; 22–25 w) (n = 101; 26–28w) |

2018–2022 (n = 149) (n = 55; 22–25 w) (n = 94; 26–28w) |

|||

| PTX, n (%) 22–25 w 26–28 w |

13/10.7 2/10.0 11/10.9 |

8/5.4 4/7.3 4/4.3 |

0.102 0.705 0.083 |

0.70 (0.49–1.01) 0.78 (0.27–2.60) 0.68 (0.49–0.96) |

| BPD, n (%) 22–25 w 26–28 w |

41/33.9 4/20.0 37/36.6 |

46/30.9 24/43.6 22/23.4 |

0.600 0.063 0.045* |

0.93 (0.70–1.22) 2.38 (0.88–6.42) 0.75 (0.57–0.98) |

| NEC, n (%) 22–25 w 26–28 w |

21/17.4 4/20.0 17/16.8 |

34/22.8 15/27.3 19/20.2 |

0.269 0.528 0.546 |

1.22 (0.84–1.76) 1.36 (0.52–3.56) 1.12 (0.77–1.63) |

| IVH all, n (%) 22–25 w 26–28 w |

53/43.8 13/65.0 40/39.6 |

39/26.2 23/41.8 16/17.0 |

0.002* 0.077 <0.001* |

0.66 (0.51–0.86) 0.50 (0.22–1.11) 0.61 (0.48–0.79) |

| IVH grade 1–2, n (%) 22–25 w 26–28 w |

16/13.2 3/15.0 13/12.9 |

18/12.1 6/10.9 12/12.8 |

0.779 0.635 0.983 |

0.94 (0.64–1.39) 0.77 (0.28–2.12) 0.99 (0.66–1.49) |

| IVH grade 3 – 4 (severe), n (%) 22–25 w 26–28 w |

37/30.6 10/50.0 27/26.7 |

21/14.1 17/30.9 4/4.3 |

0.001* 0.131 <0.001* |

0.62 (0.48–0.80) 0.56 (0.27–1.18) 0.52 (0.42–0.64) |

| PVL, n (%) 22–25 w 26–28 w |

17/14.0 3/15.0 14/13.9 |

12/8.1 4/7.3 8/8.5 |

0.114 0.316 0.240 |

0.74 (0.52–1.03) 0.58 (0.23–1.51) 0.79 (0.56–1.12) |

| PDA, n (%) 22–25 w 26–28 w |

52/43.0 8/40.0 44/43.6 |

47/31.5 16/29.1 31/33.0 |

0.053 0.377 0.130 |

0.77 (0.59–0.99) 0.71 (0.33–1.50) 0.81 (0.62–1.06) |

| Sepsis/probable sepsis, n (%) 22–25 w 26–28 w |

33/27.3 7/35.0 26/25.7 |

32/21.5 13/23.6 19/20.2 |

0.270 0.332 0.362 |

0.85 (0.63–1.13) 0.67 (0.31–1.45) 0.86 (0.64–1.16) |

| ROP≥2 n (%) 23–25 w 26–28 w |

22/18.2 5/25.0 17/16.8 |

27/18.1 16/29.1 11/11.7 |

0.990 0.731 0.310 |

0.99 (0.71–1.41) 1.17 (0.48–2.81) 0.83 (0.59–1.16) |

| NICU, days, median (IQR) † 22–25 w 26–28 w |

16 (5.5–26) 8.5 (2.25–30.25) 17 (7–26) |

22 (14–32) 24 (10–35) 22 (15–31) |

0.002* 0.082 0.005* |

- |

| Deaths, n (%) 22–25 w 26–28 w |

50/41.3 13/65.0 37/36.2 |

41/27.5 25/45.5 16/17.0 |

0.017* 0.138 0.002* |

0.72 (0.56–0.94) 0.55 (0.25–1.23) 0.65 (0.50–0.83) |

| Early death (0–6 days) (n/%) 22–25 w 26–28 w |

31/25.6 9/45.0 22/21.8 |

23/15.4 14/25.5 9/9.6 |

0.038* 0.107 0.020* |

0.73 (0.55–0.96) 0.54 (0.26–1.12) 0.68 (0.51–0.89) |

| Composite outcome (N/%) 22–25 w 26–28 w |

97/80.2 18/90.0 79/78.2 |

99/66.4 49/89.1 50/53.2 |

0.012* 0.912 <0.001* |

0.65(0.46–0.94) 0.93 (0.26–3.29) 0.68 (0.51–0.89) |

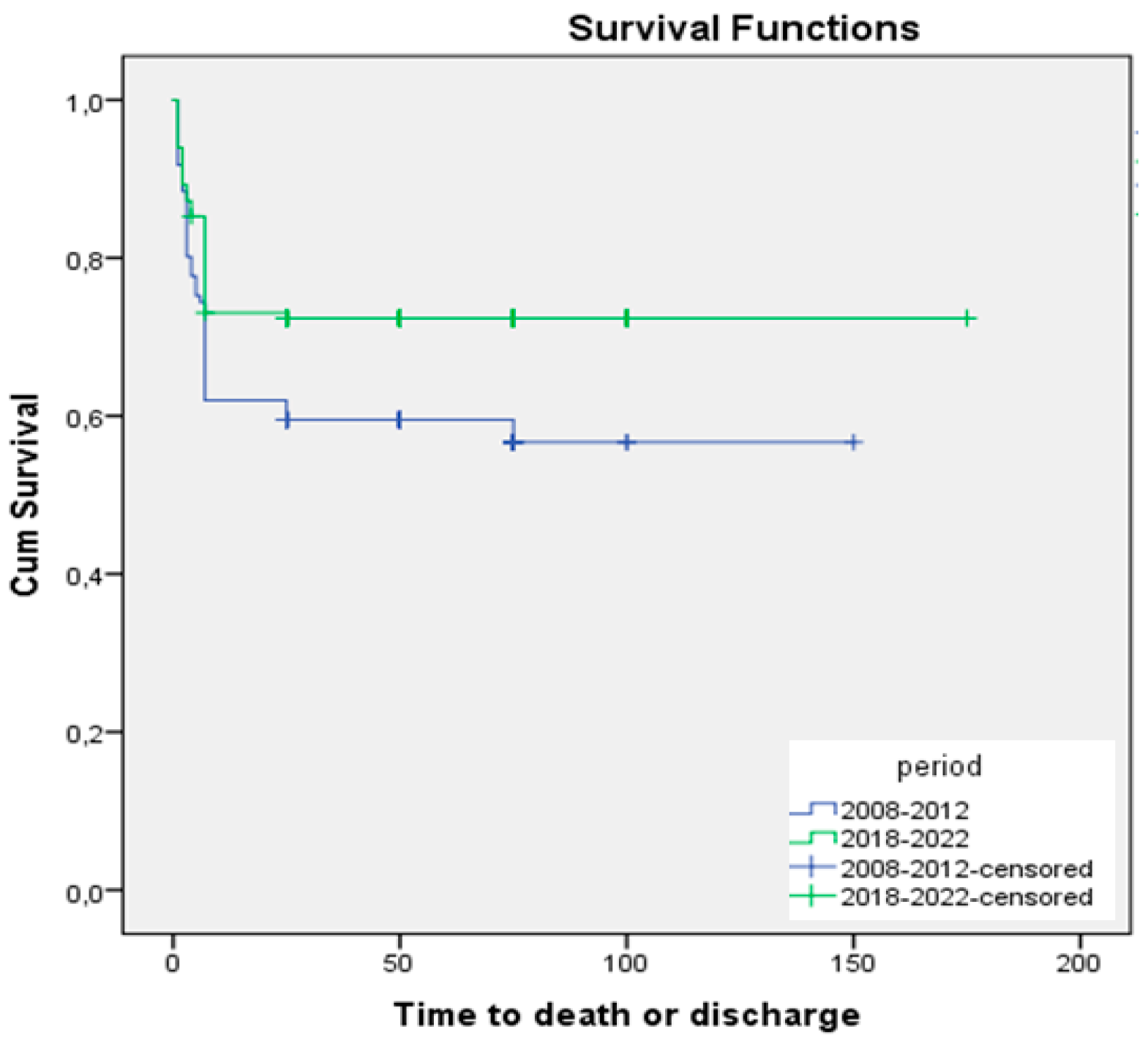

| Period | N of deaths/N of cases | Mean ± SD (95% CI) | Median ± SD (95% CI) | Chi-square | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008–2012 | 50/121 | 89.3 ± 6.6 (76.3–102.3) | 59.0 ± 2.2 (54.8–63.2) | 5.782 | 0.016 |

| 2018–2022 | 41/149 | 127.9 ± 6.2 (115.7–140.2) | 64.0 ± 3.1 (57.8–70.2) |

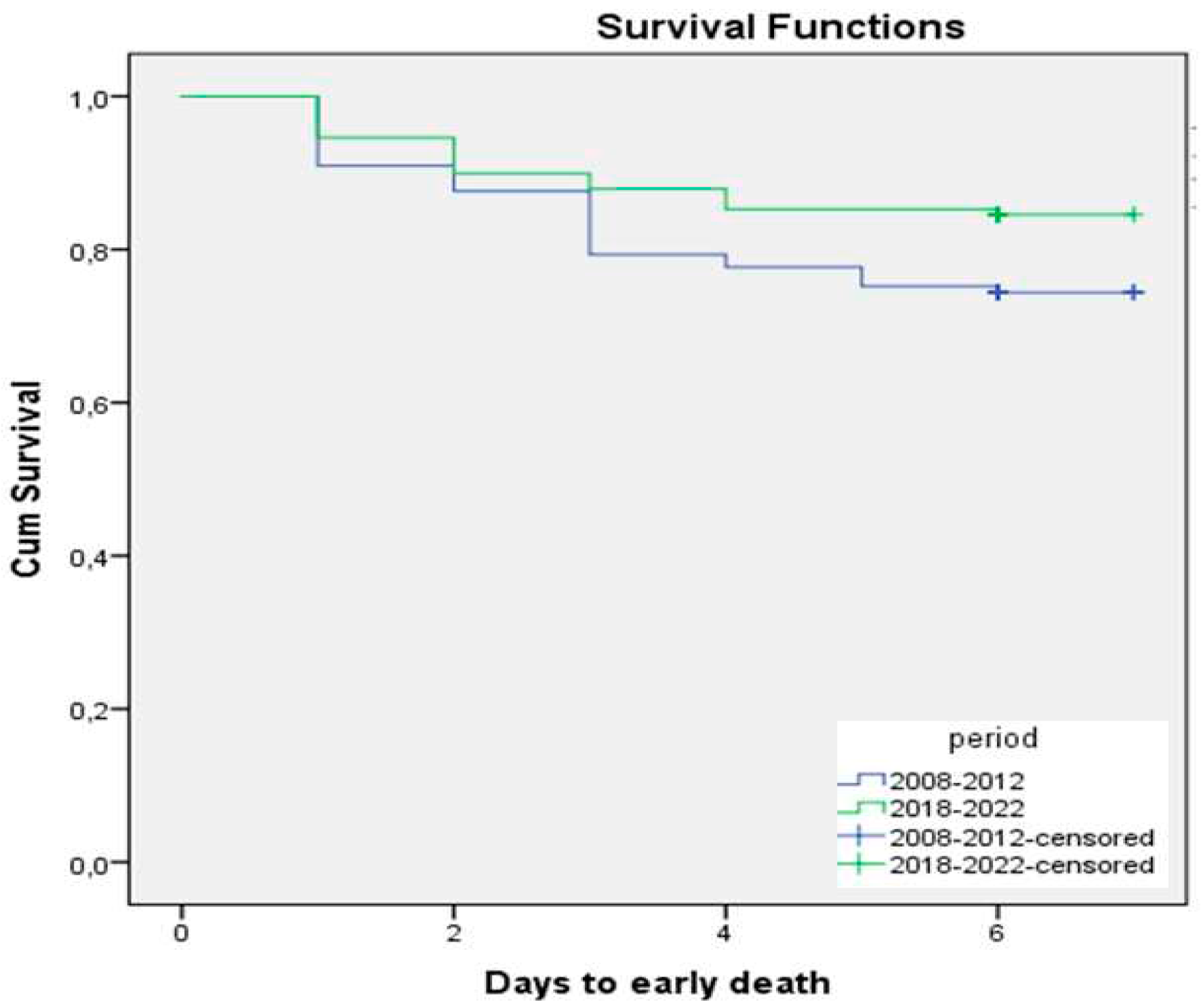

| Period | No of deaths/No of cases | Mean ± SD (95% CI) | Chi-square | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008–2012 | 31/121 | 5.8 ± 0.2 (5.5–6.2) | 4.176 | 0.041 |

| 2018–2022 | 23/149 | 6.3 ± 0.1 (6.0–6.6) |

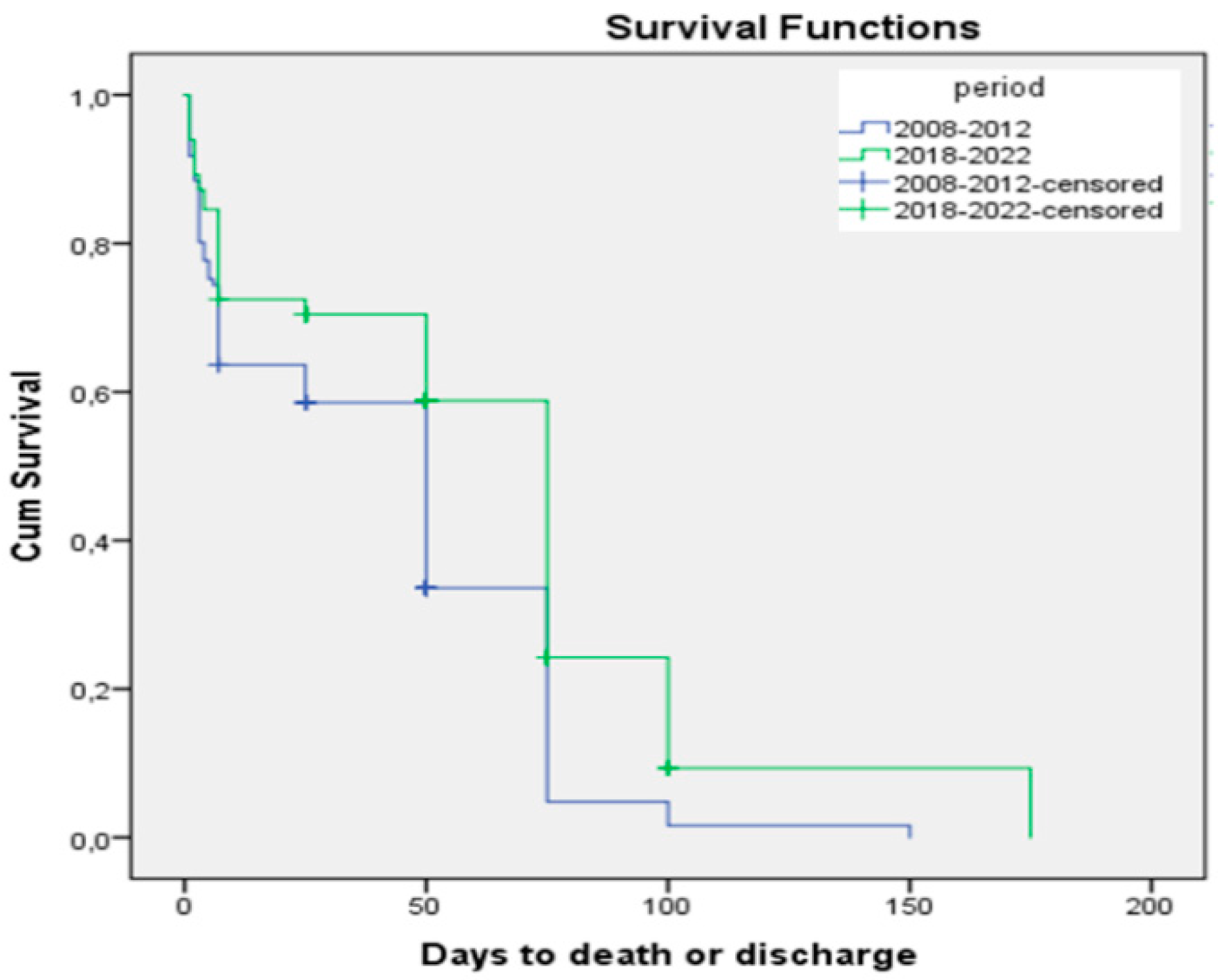

| Period | N of EP with composite outcome/N of cases | Mean ± SD (95% CI) | Median ± SD (95% CI) | Chi-square | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008–2012 | 97/121 | 42.4 ± 3.3 (36.0–48.8) | 50.0 ± 4.5 (41.1–58.89) | 17.403 | 0.00003 |

| 2018–2022 | 99/149 | 64.6 ± 4.7 (55.3–74.0) | 75.0 ± 3.2 (68.8–81.2) |

| 2008–2012 period | 2012–2022 period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | 95.0% CI | p | 95 % CI | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||

| GA | 0.643 | 0.746 | 1.608 | 0.744 | 0.691 | 1.303 |

| BW | 0.037* | 0.995 | 1.000 | 0.955 | 0.998 | 1.002 |

| Prenatal steroids | 0.005* | 1.315 | 4.790 | 0.131 | 0.846 | 3.616 |

| Outborn | 0.042* | 0.161 | 0.969 | 0.142 | 0.060 | 1.499 |

| Vaginal delivery | 0.593 | 0.600 | 2.444 | 0.318 | 0.716 | 2.798 |

| Apgar at 5minute | 0.206 | 0.943 | 1.313 | 0.494 | 0.736 | 1.159 |

| Alveolar recruitment | 0.749 | 0.439 | 3.142 | 0.006* | 1.458 | 9.665 |

| Intubation at birth | 0.491 | 0.562 | 3.317 | 0.172 | 0.688 | 8.139 |

| Surfactant | 0.129 | 0.001 | 2.476 | 0.031* | 0.001 | 0.730 |

| Severe IVH | 0.001* | 0.130 | 0.609 | 0.133 | 0.223 | 1.219 |

| BPD | 0.000* | 3.356 | 26.648 | 0.000* | 6.017 | 79.616 |

| NEC | 0.061 | 0.964 | 4.980 | 0.015* | 1.197 | 5.401 |

| Surfactant dose | 0.145 | 0.942 | 1.009 | 0.031* | 0.971 | 0.999 |

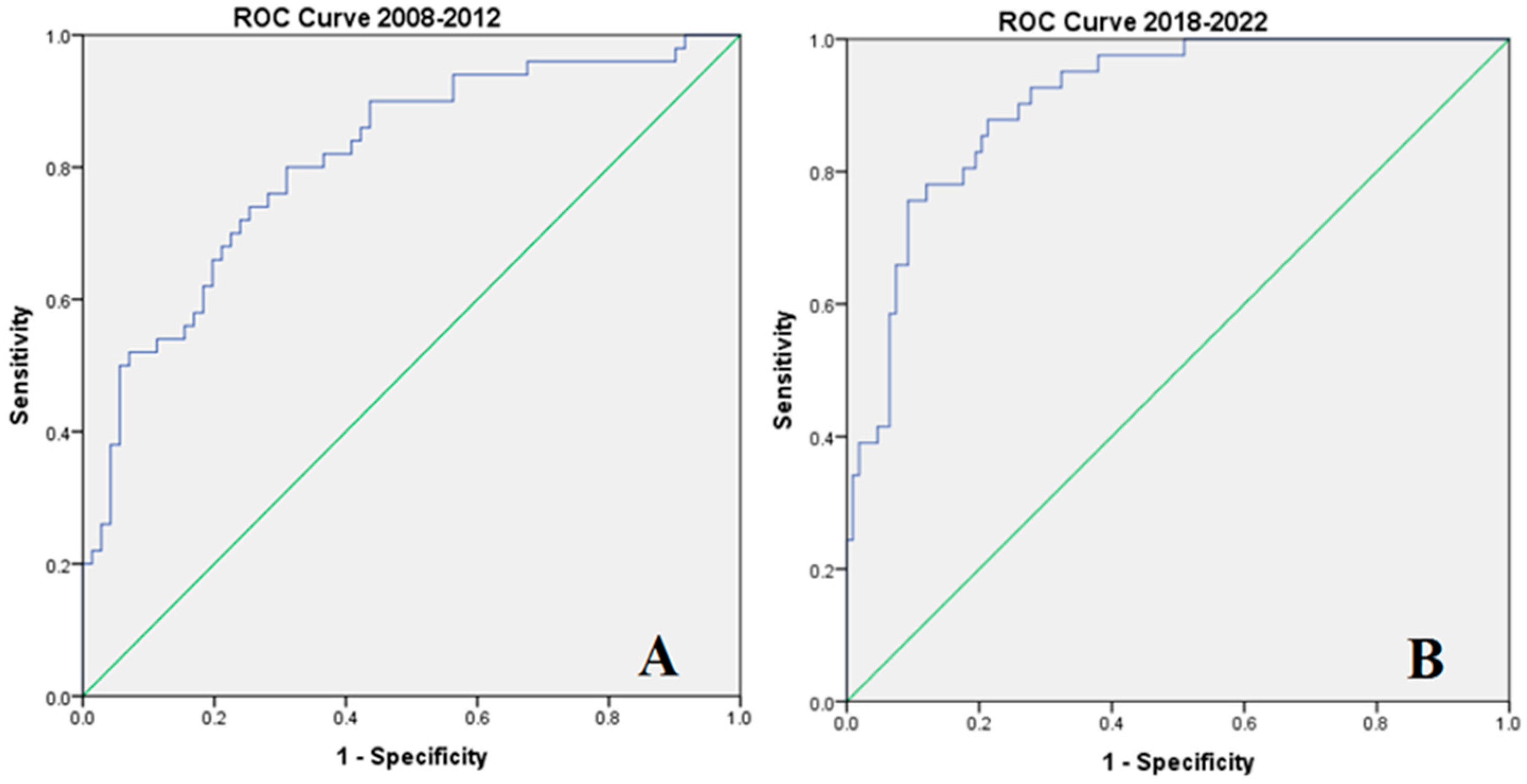

| AUC | 0,811 + /-0,040 | 0,733 | 0,889 | 0.907+/-0.024 | 0.859 | 0.955 |

| Chi-square | 97,609 | 122.368 | ||||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).