Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

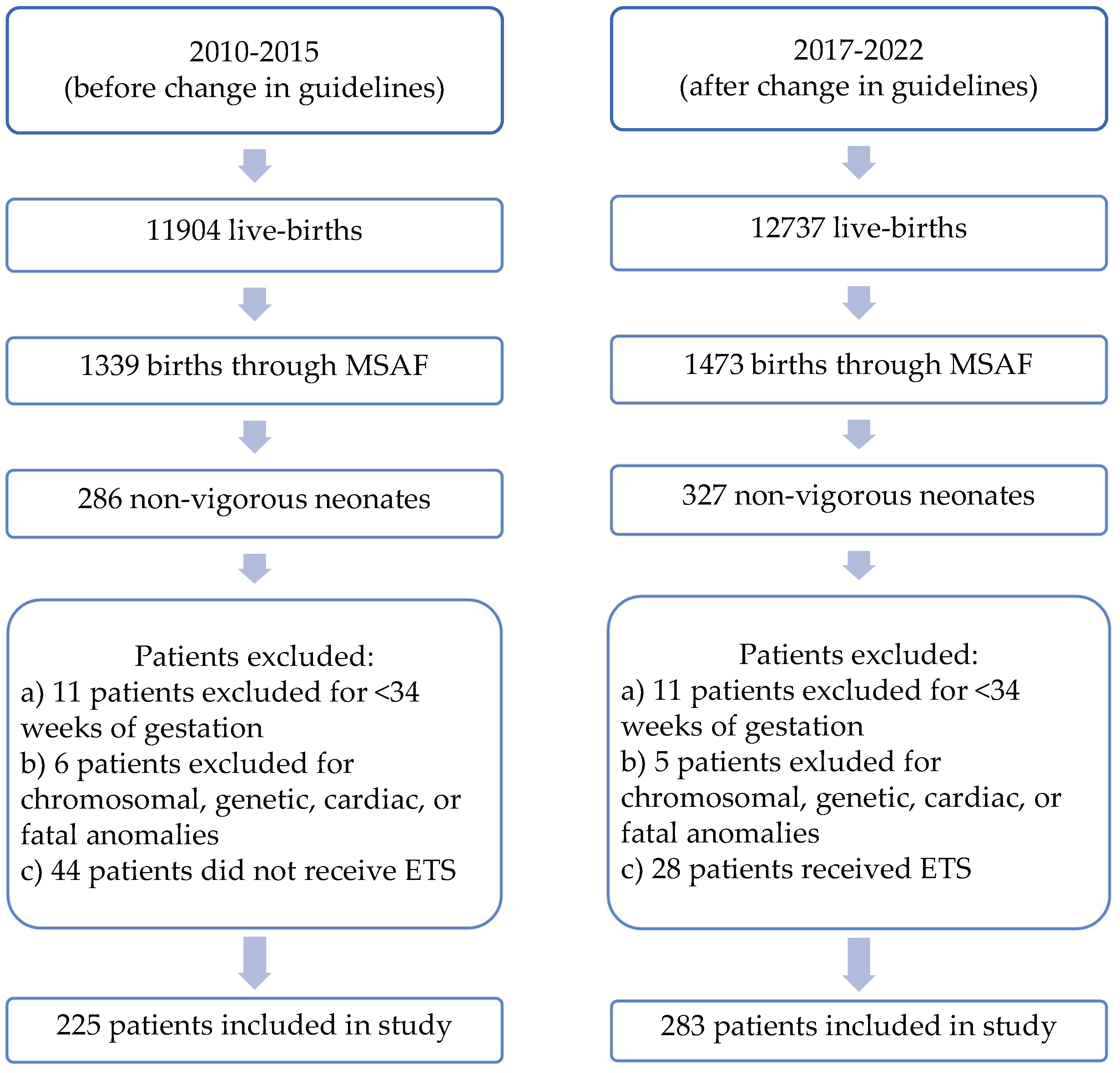

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPAP | Continuous positive airway pressure |

| PPV | Positive Pressure Ventilation |

| ECMO | Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| ETT | Endotracheal tube |

| iNO | Inhaled nitric oxide |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| MAS | Meconium aspiration syndrome |

| MSAF | Meconium-stained amniotic fluid |

| NICU | Neonatal intensive care unit |

| NRP | Neonatal resuscitation program |

| PPHN | Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn |

| SEM | Standard error of mean |

References

- Kalra, V.; et al. Neonatal outcomes of non-vigorous neonates with meconium-stained amniotic fluid before and after change in tracheal suctioning recommendation. J Perinatol 2022, 42, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurdakok, M. Meconium aspiration syndrome: do we know? Turk J Pediatr 2011, 53, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rawat, M.; et al. Approach to Infants Born Through Meconium Stained Amniotic Fluid: Evolution Based on Evidence? Am J Perinatol 2018, 35, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Lee, H.C. Revisiting the Latest NRP Guidelines for Meconium: Searching for Clarity in a Murky Situation. Hosp Pediatr 2020, 10, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Textbook of Neonatal Resuscitation; Weiner, G.M., Zaichkin, J., Eds.; American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Lakshminrusimha, S.; et al. Tracheal suctioning improves gas exchange but not hemodynamics in asphyxiated lambs with meconium aspiration. Pediatr Res 2015, 77, 347–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, M.; et al. Neonatal Outcomes since the Implementation of No Routine Endotracheal Suctioning of Meconium-Stained Nonvigorous Neonates. Am J Perinatol 2024, 41, 1366–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phattraprayoon, N.; Tangamornsuksan, W.; Ungtrakul, T. Outcomes of endotracheal suctioning in non-vigorous neonates born through meconium-stained amniotic fluid: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2021, 106, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikou, M.; et al. Routine Tracheal Intubation and Meconium Suctioning in Non-Vigorous Neonates with Meconium-Stained Amniotic Fluid: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisanuto, D.; et al. Tracheal suctioning of meconium at birth for non-vigorous infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2020, 149, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.N.; et al. Effect of endotracheal suctioning just after birth in non-vigorous infants born through meconium stained amniotic fluid: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E.M.; et al. NICU Admissions for Meconium Aspiration Syndrome before and after a National Resuscitation Program Suctioning Guideline Change. Children (Basel) 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, V.K.; et al. Change in neonatal resuscitation guidelines and trends in incidence of meconium aspiration syndrome in California. J Perinatol 2020, 40, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldhafeeri, F.M.; et al. Have the 2015 Neonatal Resuscitation Program Guidelines changed the management and outcome of infants born through meconium-stained amniotic fluid? Ann Saudi Med 2019, 39, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, P.; Gupta, A.G. Impact of the Revised NRP Meconium Aspiration Guidelines on Term Infant Outcomes. Hosp Pediatr 2020, 10, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oommen, V.I.; et al. Resuscitation of non-vigorous neonates born through meconium-stained amniotic fluid: post policy change impact analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2021, 106, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiruvolu, A.; et al. Delivery Room Management of Meconium-Stained Newborns and Respiratory Support. Pediatrics 2018, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | 2010-2015 | 2017-2022 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infants born through MSAF | 1339 | 1473 | - |

| MSAF patients that were born non-vigorous (%) | 225 (16.8%) | 283 (19.2%) | 0.71 |

| Gestational age | 39 3/7 ± 2 days | 38 6/7 ± 6 days | 0.13 |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.28 ± 0.69 | 3.27 ± 0.65 | 0.77 |

| Male gender | 120 (53%) | 133 (47%) | 0.16 |

| Multiple gestation | 2 (0.9%) | 6 (2.1%) | 0.28 |

| Apgar score 1 minute [Median (IQR)] | 4(2-6) | 3(2-5) | 0.32 |

| Apgar score 5 minute [Median (IQR)] | 7(6-8) | 7(6-8) | 0.08 |

| Apgar score 10 minute [Median (IQR)] | 8(7-8) | 8(6-8) | 0.21 |

| Cord pH | 7.16 ± 0.13 | 7.19 ± 0.12 | 0.07 |

| C-section | 132 (58.7%) | 166 (58.7%) | 0.99 |

| Vaginal delivery | 93 (41.3%) | 117 (41.3%) | |

| General anesthesia for delivery | 36 (16%) | 40 (14%) | 0.57 |

| Spinal/Epidural anesthesia for delivery | 119 (53%) | 153 (54%) |

| Outcomes for non-vigorous patients born through MSAF | 2010-2015 (n=225) |

2017-2022 (n=283) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients admitted to NICU | 179 (80%) | 241 (85%) | 0.68 (0.43-1.08) | 0.10 |

| Patients admitted to Newborn Nursery | 46 (20%) | 42 (15%) | 1.47 (0.93-2.34) | 0.10 |

| Non-vigorous patients diagnosed with MAS | 66 (29.3%) | 59 (19.7%) | 1.58 (1.05-2.36) | 0.03* |

| Non-vigorous patients diagnosed with PPHN | 20 (8.9%) | 7 (2.5%) | 3.85 (1.60-9.27) | 0.003* |

| Non-vigorous patients who received iNO | 10 (4.4%) | 16 (5.7%) | 0.78 (0.35-1.75) | 0.54 |

| Non-vigorous patients who required ETT | 73 (32.4%) | 103 (36.4%) | 0.83 (0.58-1.21) | 0.35 |

| Non-vigorous patients who required chest compressions | 15 (6.7%) | 14 (4.9%) | 1.37 (0.65-2.91) | 0.41 |

| Non-vigorous patients who required epinephrine | 4 (1.8%) | 6 (2.1%) | 0.84 (0.23-3.00) | 0.78 |

| Non-vigorous patients who required surfactant | 17 (7.6%) | 9 (3.2%) | 2.49 (1.09-5.69) | 0.03* |

| Patients who required supplemental O2 | 69 (30.7%) | 80 (28.3%) | 1.12 (0.76-1.65) | 0.56 |

| Patients who required CPAP support | 13 (5.8%) | 7 (2.5%) | 2.42 (0.95-6.17) | 0.06 |

| Patients who required non-invasive ventilation support | 19 (8.4%) | 20 (6.7%) | 1.21 (0.63-2.33) | 0.56 |

| Patients who required conventional ventilator support | 45 (20%) | 44 (14.7%) | 1.36 (0.86-2.15) | 0.19 |

| Patients who required High Frequency Jet ventilator support | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0.63 (0.06-6.96) | 0.70 |

| Patients who required High Frequency Oscillator ventilator support | 10 (4.4%) | 8 (2.8%) | 1.60 (0.62-4.12) | 0.33 |

| Patients who required mechanical ventilation | 56 (24.9%) | 54 (19.1%) | 1.41 (0.92-2.15) | 0.12 |

| Mean ventilator days [per patient] ± SEM | 2.27 ± 0.3 | 2.26 ± 0.32 | 0.98 | |

| Median ventilator days [per patient] (IQR) | 2 (1-2) | 2 (1-3) | ||

| Patients who required non-invasive mechanical ventilation (%) | 101 (44.9%) | 107 (37.8%) | 1.34 (0.94-1.91) | 0.11 |

| Mean days on non-invasive respiratory support [per patient] ± SEM | 5.31 ± 2.36 | 4.62 ± 0.65 | 0.65 | |

| Median days on non-invasive respiratory support [per patient] (IQR) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-5) | ||

| Number of patients requiring ECMO | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.4%) | 0.25 (0.01-5.26) | 0.37 |

| Number of patient deaths (%) | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (1.1%) | 0.42 (0.04-4.03) | 0.45 |

| Length of stay | 17.96 ± 1.88 | 14.53 ± 1.44 | 0.14 | |

| *p-value <0.05 | ||||

| CPAP: Continuous positive airway pressure. ECMO: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ETT: Endotracheal Tube. iNO: inhaled nitric oxide. IQR: Interquartile range. MAS: Meconium aspiration syndrome. MSAF: Meconium-stained amniotic fluid. NICU: Neonatal intensive care unit. PPHN: Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. SEM: Standard error of mean. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).