1. Introduction

As the global population rises and the need for sustainable construction grows, the building sector has significantly contributed to energy consumption [

1,

2]. Cement production generates much CO

2 [

3]. According to the current data, global concrete production is about 24 billion tons per year, which leads to a worldwide emission of 7-10% of CO

2 into the atmosphere [

4,

5]. Using natural resources such as river sand, gravel, clay, limestone, and cement is a key factor in global warming and climate change [

6], producing waste and potentially harmful atmosphere [

7]. Therefore, finding a new raw material to reduce carbon emissions and construction costs and replace existing building materials is urgently needed.

In the 1970s, foreign countries accelerated the research on fiber concrete. Due to the high cost of high elastic modulus fiber, the affordable low elastic modulus fiber became the main research object, including the resource-rich plant fiber. Yun et al. [

8] discussed the impact of different doses of natural plant fiber on the compressive strength of plant fiber cement materials. On the other hand, Niu and Kim [

9] introduced an innovative method for making cement-based composites from corn stalk plants. Katman et al. [

10] explored the substitution of cement in concrete with 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% wheat straw ash as an environmentally friendly alternative. Saad et al. [

11] developed a plaster composite of wheat straw and used it as an insulating heat material in buildings. Ren et al. [

12] found a new type of straw block with wheat straw fiber, sand, and cement applied to the solar greenhouse wall.

As seen from the above, straw fiber composite material has many advantages. Wang et al. [

13] studies revealed that 46.88 wt% cellulose sugar can be extracted from 15 g corn stalk. Therefore, Xie et al. [

14] demonstrated that untreated agricultural waste fibers affected Portland cement's hydration and plant fibers' use in the cement-based composite and prolonged the hardening time of cement. To resolve those issues, Bederina et al. [

15] research showed that using hot water to treat barley straw can improve the performance of lightweight composite concrete. Maglad, A. M et al. [

16] discussed that burning wheat and corn stalks into straw ash improves the engineering performance of cement-based composite material.

In addition, as the world's largest agricultural country, China produces more than 900 million tons of straw every year, including corn straw, wheat straw, and rice straw [

17]. Agricultural waste straws are burned or discarded after each harvest, causing severe environmental pollution. Therefore, the organic combination of the two can reduce carbon emissions and construction costs.

However, current research on using agro-waste straw fiber blocks in wall structures to combine the composite action of mechanical and physical properties of agro-waste straw fiber blocks, such as corn straw fiber blocks and wheat straw fiber blocks, is still limited. Research on this issue has not been carried out from the perspective of combining the properties of the different agro-waste fibers, such as corn stalk fibers and wheat straw fibers from the perspective of combining the properties of the different agro-waste fibers, such as corn stalk fibers and wheat straw fibers, has not been carried out. Therefore, it is imperative and urgent to study the performance of composite straw fiber in corn and wheat straw fiber.

A series of standard compressive and flexural strength tests were carried out to investigate the mechanical performance of WCSFCC and analyze the impact of the agro-waste straw fibers treated method, cement grade, and dosage of straw ashes on it. A detailed discussion of the physical and mechanical behaviors of the WCSFCC high-pressure brick was performed. Furthermore, the cost and application of the WCSFCC materials to produce high-pressure bricks were discussed. The findings may assist the designer of WCSFCC high-pressure bricks in eco-friendly construction.

2. Material and Experiment

2.1. Material Used

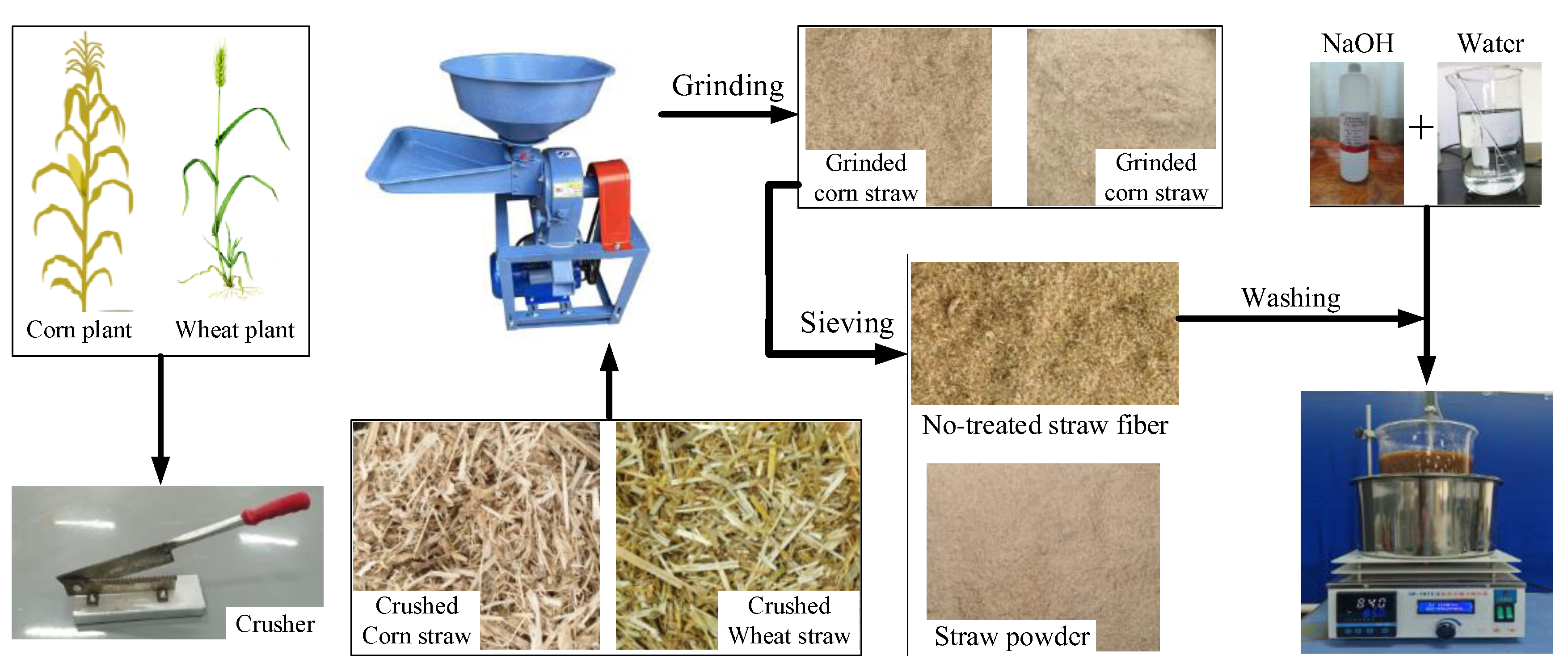

(1) Corn and wheat straws were purchased from local farmers. The straws were selected during purchase and then cut and crushed by the appropriate machine, as shown in

Figure 1. The crushed straw fiber size was < 5 mm. After sieving, the straw fibers (particle size > 0.6 mm) were washed with an Alkaline solution, dried, and employed for experiments.

(2) Cement: Purchase P.O42.5 grade cement, P.O52.5 grade cement, and white cement P.W 52.5 grade (with whiteness > 90%) from a local factory.

(3) Silica fume is a model HN-016 that contains more than 98% of SiO2 from Henno company.

(4) Water: The water/cement ratio (W/C) was 0.5.

(5)NaOH (Sodium hydroxide) bought from Wabcan Company. The NaOH concentration is 0.2002 mol/L, meeting the Chinese specification GB/T601-2016 [

18].

2.2. Straw Fiber Pretreatment

Current literature on corn stalks and wheat shows they contain large amounts of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Cellulose and hemicellulose hydrolyze in water and release monosaccharides, such as glucose, xylose, arabinose, and galactose, collectively called cellulosic sugar [

19,

20]. Previous research [

14] demonstrated that untreated agricultural waste affects Portland cement's hydration and plant fibers used in the cement-based composite, prolonging the hardening time of cement. Therefore, it is imperative to pretreat the straw fiber.

This study mixed 100 g of straw fiber with 5 wt% NaOH and 2.5 L of water. It was stirred thoroughly, heated to 85℃, and maintained boiling and mixing for 1 hour. as illustrated in

Figure 1.

The agro-waste straw fibers will be rinsed with water several times until they have a neutral pH. The fibers will be dried in air at room temperature ( 25℃± 2℃), as shown in

Figure 2.

2.3. Specimen

As summarized in

Table 2, nine straw fiber cementitious mixtures were designed to analyze the effect of the straw powder, cement grade, straw ashes, and straw ashes in the WCSFCC. In the variable of straw powder, Ord1-Wheat refers to the composite with mixed wheat straw fiber and powder and ordinary Portland PO 42.5 and silica fume. In contrast, Ord1-Corn refers to the composite mixed with corn straw fiber, corn straw powder, ordinary Portland PO 42.5, and silica fume. Moreover, the mix Ord1-Wheat+Corn denotes the composite mixed with wheat and corn straw fiber, wheat and corn straw powder, ordinary Portland PO 42.5, and silica fume. The white cement P.W-52.5 and ordinary Portland PO 52.5 were used as replacements for the cement ordinary Portland PO 42.5 in the mixture Ord1-Wheat+Corn to obtain the mixtures W-Wheat+Corn and Ord2-Wheat+Corn, respectively. In the variable of straw ash, 3wt% straw ashes (wheat and corn) were used to replace the wheat and corn straw powders contained in the mix Ord1-Wheat+Corn. So, the mixtures Ord1-B-Wheat+Corn, Ord2-B-Wheat+Corn, and W-B-3-Wheat+Corn were referred to as the wheat and corn straw fiber cementitious contained 3wt% straw ash mixed with ordinary Portland PO 42.5, ordinary Portland PO 52.5, and with cement P.W-52.5, respectively. The straw ash dosage was increased from 3wt% to 5wt% with an increasing rate of 1wt%. The mixes W-B-4-Wheat+Corn and W-B-5-Wheat+Corn were the wheat and corn straw fiber cementitious with 4wt% and 5wt% straw ashes, respectively. Those samples were compared with each other.

2.4. Experimental Device and Method

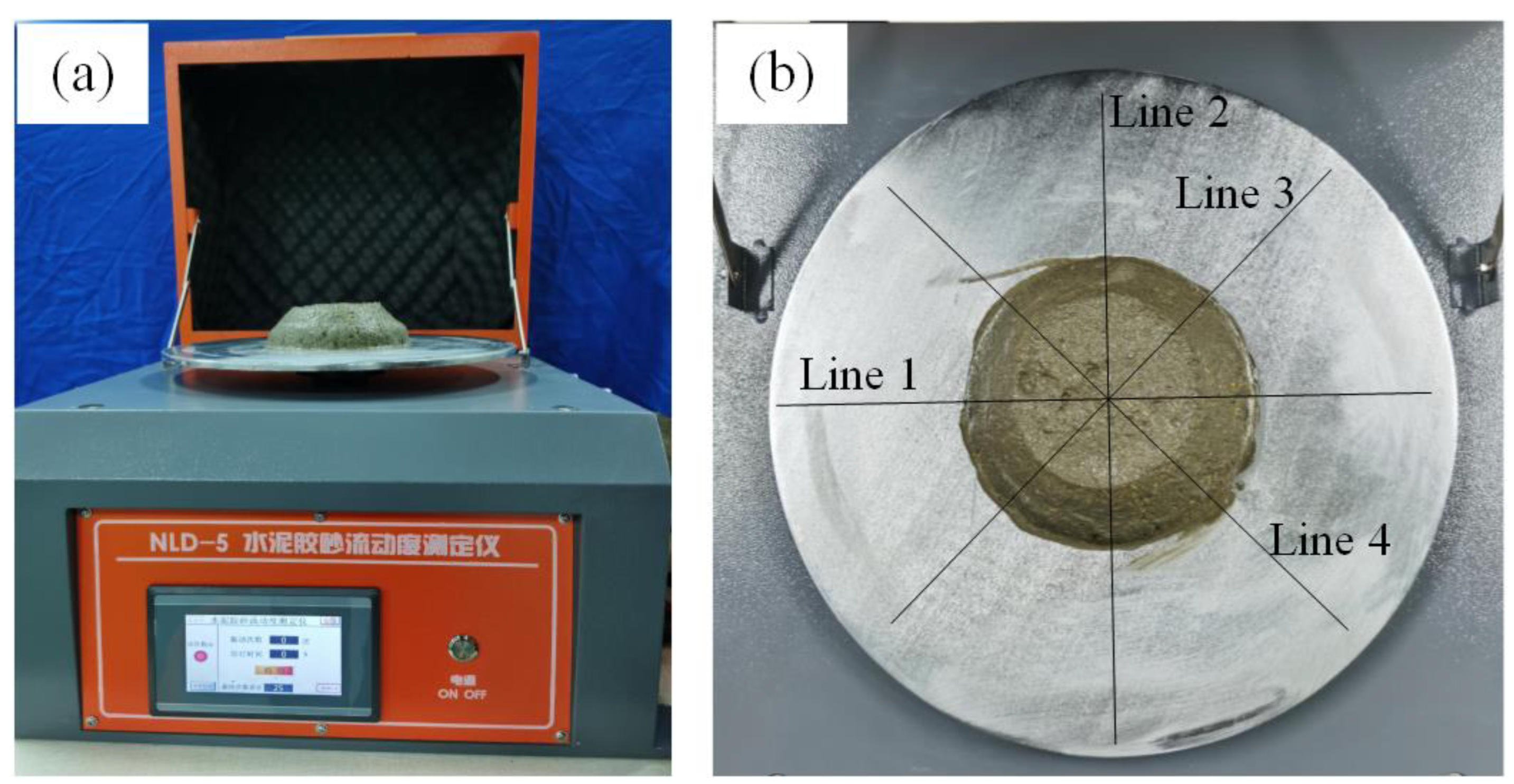

The different straw fiber cementitious composites were mixed with a water/cement ratio of 0.5. The fresh WCSFCC's workability was tested according to the standard ASTM C1437 [

21]. The fresh WCSFCC was filled in the flow test mold in two layers, where each layer was compacted using the tamping rod with 20 strokes. The mold was removed, and the flow table was jolted 25 times within 15 seconds. The diameter of the WCFSCCC mortar was measured in two directions perpendicular to each other, and the average flow value and standard deviation were calculated.

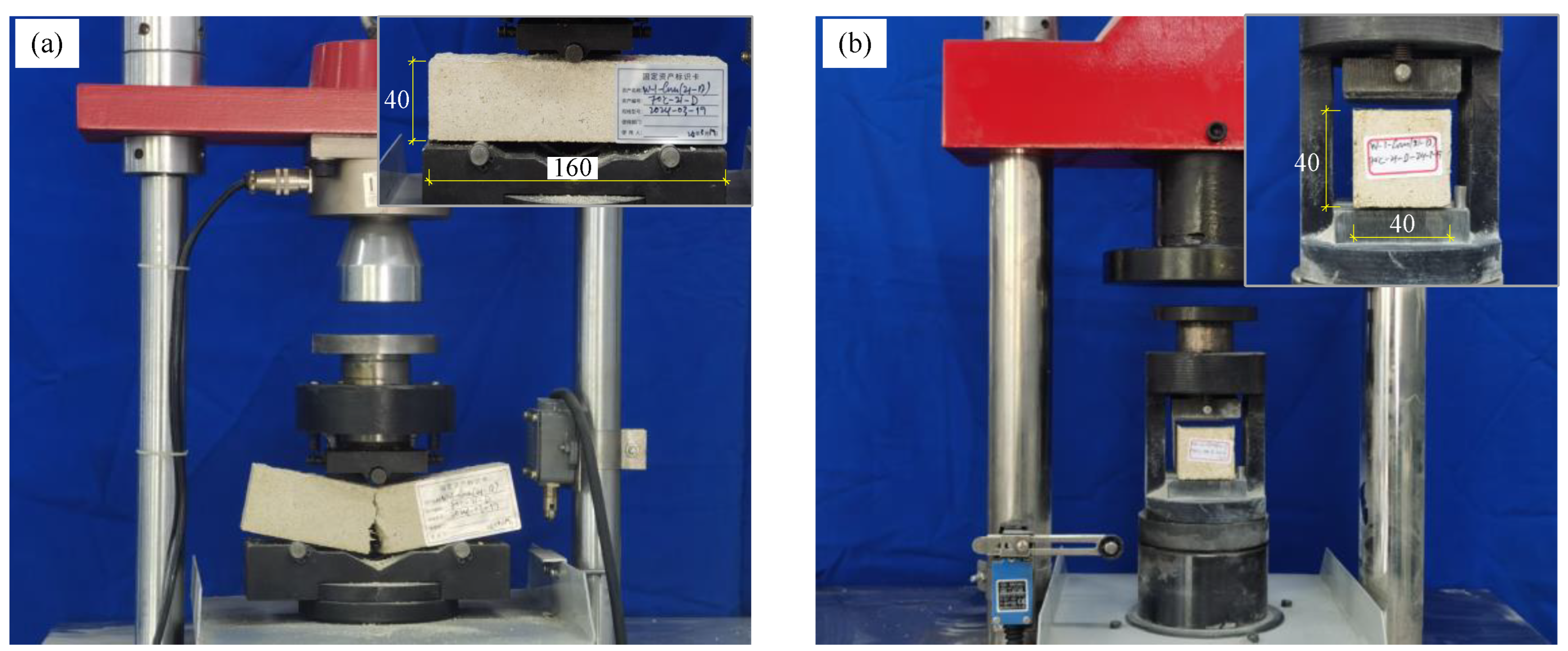

According to Standard GB/T50081–2019 [

22], 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm samples were used for the flexural strength test. After removing the curing box, the specimens were dried in the oven for 96 h at 70℃. At the curing age, the samples were removed from the oven and soaked in water for 24 hours. They were again dried at 100℃ for 24h. The samples' sizes and the weight were measured, and the dry density was determined. The samples of sizes 40 mm × 40 mm × 40 mm were adopted for the compressive strength test. Flexural and compressive strength tests of the straw fiber cementitious composite samples were tested at 14d, 21d, and 28d. Pressure machine WAY-300B with a 3000 kN load capacity was used to complete the flexural and compressive strength tests with the loading rate of 0.05 MPa/s and 0.5 MPa/s for the flexural and compressive strength tests, respectively, as shown in

Figure 3. The flexural and compressive strengths are the arithmetic average of the measurement values of three samples. The standard deviation of each mixture at different curing ages was summarized in

Table 2.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Workability

Figure 4 presents the behavior of WCSFCC fresh material after removing the flow cone. The WCSFCC mix was observed to settle uniformly and maintain its shape. This flowability indicates the correct water content in the mixes, which means suitable workability.

Table 1 summarises the flow test results of each mixture. The results of the straw fiber cementitious mixtures with straw powders ranged between 114-120 mm, with the corresponding standard deviation ranging from ± 0.6 mm to ± 0.77 mm. The flow value of the mixture with wheat was higher than that of the corn. These results could be attributed to the increase in the specific surface area of the wheat fibers and powders compared to corn. The property of the corn straw particles to absorb water is highlighted in the mix. A significant flow value of the mixture Odr1-Wheat+Corn is attributed to the high ratio of the corn fibers and powders in the mix. Increasing the cement grade in the mixture decreased the flow value of WCSFCC. This phenomenon should be attributed to the higher specific surface area developed by the high-grade cement. When the straw powder was replaced with the straw ash, the flow value of the mixture decreased with the cement grade. These findings should be attributed to the higher specific surface area of the straw ash compared to the straw powder. The increase in the straw ashes considerably reduced the workability of WCSFCC.

3.2. Mechanical Properties

As shown in

Table 2, the flexural and compressive strengths of the straw fiber cementitious composites are influenced by the straw fibers, cement grade, straw ashes, and dosage of straw ashes. In the variable of straw fibers, the strength of the mixing of wheat and corn straw fiber cementitious is lower than the strength of wheat straw and corn stalk mixes. The main reason is that the mixed properties and proportion of different straw powders affect the mechanical properties of WCSFCC. The cement quantity or cement grade can be changed to solve this problem. First, high-grade cement was used to resolve the lower mechanical properties of WCSFCC. The findings showed that adopting high-grade cement increased the compressive strength of WCSFCC to 14.33% and 56.62% for white cement and P.0 52.5, respectively. However, it could be noted that using high-grade cement could increase the price of the mixing. Therefore, the straw powders in the mixes are burned to improve the mechanical properties of WCSFCCs [

16]. The results proved that replacing the straw powders with the straw ashes effectively ameliorated the mechanical properties of WCSFCC, with the compressive strength ranging between 11.48 MPa and 19 MPa at 28 days of age, while the flexural strength of WCSFCC was raised to 7.0 times at 28 days of age. The impact of straw ash dosage on the WCSFCC was analyzed. The findings demonstrated that increasing the straw ash rates decreased the mechanical properties of the WCSFCC. Furthermore, for the WCSFCC brick design, adopting 5 wt% straw ash is enough for the design requirements.

3.3. Dry Density

The dry density values increased with the curing age of each specimen, as illustrated in

Table 2. It was shown that changing the cement grade increased the dry density of WCSFCC. The reason is that using high-grade cement improves the compactness of the mixing due to its higher specific surface area. On the other hand, the analysis of the results demonstrated that replacing the portion of the cement with the straw ash increased the dry density of WCSFCC. This denoted that the rate of porosity was reduced. The results show that increasing the dosage of the straw ash decreases the dry density. Those findings required the research conclusions of Khan et al. [

23]. The straw ash dosage changes and optimizes the WCSFCC structure, making the mixtures lighter and have a lower density.

4. Cost of WCSFCC High-Pressure Brick

The reform of insulation materials and the large-scale application of building energy levels elevate the environmental priority of building projects. Straw fiber cementitious application has been widely recognized and has broad application prospects. Wheat production in China is ranked first globally, with an annual output of over 130.2 million tons [

24]. However, most government policies in China are to establish a wheat straw for returning to the fields to raise the utilization rate. Given the current situation, only about 2% of the straw is applied. Straw fiber utilization is still concentrated in power generation and food packaging, causing environmental pollution. Corn's annual production output in China is about 288.84 million tons in 2023 [

25,

26]. Due to its irregular shape and heavy volume, direct incineration in the field is liable to lead to soil compaction, which reduces the moisture storage, distribution, and adequate water of the field and consequently affects the overall ecosystem of the field, leading to increased risk of fires. Therefore, both the utilization rate of these straws and government policies are essential subjects of the research. For example, using straw fibers to develop straws into masonry materials resolves the disposal problem of straw fiber, which has a high carbon and high specific energy accumulation.

It is advised to take these factors into account when evaluating the cost of straw fiber cementitious high-pressure brick masonry: specifically, the costs of wheat straw and corn straw, treatment cost, and high-pressure brick masonry and the savings of various components in the construction process, rather than just the low cost of the high-pressure brick material.

This is because after high-pressure molding, the quality of high-pressure brick masonry is good, and the quantities of water, steel bars, short fiber, and volume are significantly reduced; these benefits are unmatched by traditional brick-and-concrete composite walls. The field-laden handling of brick masonry construction is quick and easy, with lower labor costs. In addition, wheat and corn straw fiber cementitious high-pressure brick masonry is environmentally friendly and energy-efficient, leading to additional long-term health benefits.

5. Application Field of WCSFCC

Overall, wheat and corn straw fiber cementitious composite high-pressure bricks comprise a potential, sustainable, and economical approach to satisfy the requirement of green buildings.

WCSFCC possesses sustainable characteristics such as low-embodiment energy and low-carbon emission, which is recoverable at a trivial cost. In this study, wheat and corn straws were identified as agricultural wastes with great potential and structural advantages and were developed as eco-friendly raw materials of brick masonry for remarkable performance. WCSFCC high-pressure bricks exhibit unique efficiency in terms of sustainability performance, which includes a decrease in manufacturing energy absorption, prevention of the emission of carbon dioxide, reduction of the dead load, conservation of harmful spectacles, enhancement of the life-cycle efficiency, and the advantages of simple and zero-cost kindling.

This study presented the physical and mechanical properties of WCSFCC, which varied regardless of the straw fiber and powder pretreatment method and the cement grade adopted. Therefore, straw fiber composite material can be used for load-bearing, non-load-bearing, and mixed wall structures depending on different circumstances, such as load-bearing conditions and wall structures. Based on the findings presented in

Table 2 and the masonry structure specification standard [

27,

28], WCSFCC with straw powder is suitable for producing high-pressure brick for non-load-bearing walls. However, straw fiber composite with straw ashes is ideal for producing high-pressure brick for load-bearing walls. Moreover, the straw fiber cementitious composite with straw powder can be used as insulation material.

6. Conclusions and Outlook

This experiment mainly studied the mechanical and physical properties of WCSFCC, discussed the influence of straw fibers, cement grade, straw ashes, and dosage of straw ashes on the mechanical properties and dry density, workability, and analyzed the cost of WCSFCC high-pressure brick, summarized as follows:

The findings showed that the cement grade and the straw ashes influenced the workability of WCSFCC. Excess water influences the condensation and hardening time of the mixture in the flowability tests. Therefore, low w/c is recommended to manufacture the WCSFCC high-pressure brick competently.

Adding straw ash to the straw fiber cementitious mixture improved the compressive strength from 11.48 MPa to 19 MPa at 28 days of age, while the flexural strength of WCSFCC was raised to 7.0 times at 28 days. Meanwhile, exploring the influence of the dosage of straw ashes on the experimental results, we found that 3 wt% straw ash meets design requirements.

The dry density of the mixtures using straw ash is higher than that of straw powder due to the reduction of the porosity rate. However, increasing the straw ash dosage decreased the dry density of the mixtures. The dosing of straw ash changes and optimizes the WCSFCC structure, making the samples lighter and lower density.

Using straw fiber cementitious high-pressure brick masonry is more economical. Specifically, the lower costs of wheat straw and corn straw, treatment lower cost, and labor costs. In addition, from the perspective of sustainable development, it is more beneficial to the environment and health.

It is recommended that the WCSFCC high-pressure brick with straw powder be used for non-load-bearing walls as thermal insulation material, and the WCSFCC high-pressure brick with straw ashes should be used for load-bearing walls.

Although the experiment proved that using straw ashes in the straw fiber cementitious could improve the mechanical properties of high-pressure bricks, many problems remain, such as high-pressure brick sizes and WCSFCC high-pressure brick masonry structures. Complementary experimental tests, such as the thermal and acoustic properties of the WCSFCC high-pressure bricks, should be further established. Numerical simulations should be performed based on the existing mechanical and physical properties to verify whether the theoretical value coincides with the experimental conclusions. At the same time, the application of different types of bricks in the wall should be further verified in the industrial production process.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the mechanism, driving effect, and improvement path of infrastructure digitization on urban resilience in the Shanxi Province funding program (202204031401079).

References

- Amiri, A.; Ottelin, J.; Sorvari, J. Are LEED-certified buildings energy-efficient in practice? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo, O.; Rivela, B.; Neila, J. The challenge of sustainable building renovation: assessment of current criteria and future outlook. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.J.; Jhatial, A.A.; Rid, Z.A.; Rind, T.A.; Sandhu, A.R. Marble Powder as Fine Aggregates in Concrete. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2019, 9, 4105–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheel, N.; Ibrahim, M.H.W.; Adesina, A.; Kennedy, C.; Shar, I.A. Mechanical performance of concrete incorporating wheat straw ash as partial replacement of cement. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2020, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.S.S.; Senjyu, T.; Ibrahimi, A. M.; Ahmadi, M.; Howlader, A.M. A managed framework for energy-efficient building. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 21, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shad, R.; Khorrami, M.; Ghaemi, M. Developing an Iranian green building assessment tool using decision making methods and geographical information system: case study in Mashhad city. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M. Growth and sustainability trends in the buildings sector in the GCC region with particular reference to the KSA and UAE, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, K.K.; Hossain, M.S.; Han, S.; Seunghak, C. Rheological, mechanical properties, and statistical significance analysis of shotcrete with various natural fibers and mixing ratios. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Kim, B.H. Method for Manufacturing Corn Straw Cement-Based Composite and Its Physical Properties. Materials, 2022, 15, 3199.

- Katman, H.Y.B.; Khai, W.J.; Bheel, N.; Kırgız, M.S.; Kumar, A.; Khatib, J.; Benjeddou, O. Workability, Strength, Modulus of Elasticity, and Permeability Feature of Wheat Straw Ash-Incorporated Hydraulic Cement Concrete. Buildings 2022, 12, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzem, L.S.; Bellel, N. Thermal and Physico-Chemical Characteristics of Plaster Reinforced with Wheat Straw for Use as Insulating Materials in Building. Buildings 2022, 12, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Guo, S.; Sun, J. Study on the hygrothermal properties of a Chinese solar greenhouse with a straw block north wall. Energy Build. 2019, 193, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, C.Q.; Chang, J.; Yin, Q.Q.; Huang, W.W.; Liu, Y.; Dang, X.W.; Gao, T.Z.; Lu, F.S. Effect of physicochemical pretreatments plus enzymatic hydrolysis on the composition and morphologic structure of corn straw. Renew. Energy, 2019, 138: 502–508.

- Xie, X.L.; Gou, G.J.; Wei, X.; Zhou, Z.W.; Jiang, M.; Xu, X.L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Hui, D. Influence of pretreatment of rice straw of straw fiber filled cement based composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 113, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bederina, M.; Belhadj, B.; Ammari, M.S.; Gouilleux, A.; Makhloufi, Z.; Montrelay, N.; Quéneudéc, M. Improvement of the properties of a sand concrete containing barley straws treatment of the barley straws. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 115, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglad, A.M.; Amin, M.; Zeyad, A.M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Agwa, I.S. Engineering Properties of Ultra-High Strength Concrete Containing Sugarcane Bagasse and Corn Stalk Ashes. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 3196–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.Y.; Song, S.Q.; Yang, J.W. Comparative Environmental Evaluation of Straw Resources by LCA in China. Adv. Mat. Sc. Eng. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Standard of the People's Republic of China. Chemical reagent - Preparations of reference titration solutions GB/T601-2016, GB601-2016. Beijing, People's Republic of China, 2017.

- Coronado, M.; Montero, G.; Garcia, C.; Torres, R.; Vazquez, A.R.; Ayala, J.; Leon Perez, L.; Romero, E. Cotton stalks for power generation in Baja California, Mexico by SWOT analysis methodology. Energy Sustain. 2015, 195, 75–86.

- Korjenic, A.; Zach, J.; Hroudová, J. The use of insulating materials based on natural fibers in combination with plant facades in building constructions. Energy Build. 2016, 116, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1437-07. Standard Test Method for Flow of Hydraulic Cement Mortar; ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2009.18.

- National Standard of the People's Republic of China. Standard for test methods of concrete physical and mechanical properties, GB/T 50081–2019. Beijing, China: Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China, 2019.

- Khan, M.S.; Ali, F.; Zaib, M.A. A Study of Properties of Wheat Straw Ash as a Partial Cement Replacement in the Production of Green Concrete. J. Sc. Technol. 2019, 3, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.J.; Zhou, Y.; Xin, W.L.; Wei, Y.Q.; Zhang, J.L.; Guo, L.L. Wheat breeding in northern China: Achievements and technical advances. The Crop Journal, 2019, 7, 718-729.

- General Administration of Customs of the People's Republic of China. Customs Statistics http://www.customs.gov.cn/.

- Luo, N.; Meng, Q.F.; Feng, P.Y.; Qu, Z.R.; Yu, Y.H.; Liu, D.L.; Müller, C.; Wang, P. China can be self-sufficient in maize production by 2030 with optimal crop management. Nature Communications, 2023, 14, 1-11.

- ASTM C90-16a. Standard Specification for Loadbearing Concrete Masonry Units. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2017.

- National Standard of the People's Republic of China.General code for masonry structures, GB55007-2021. Beijing, China: Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).