Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

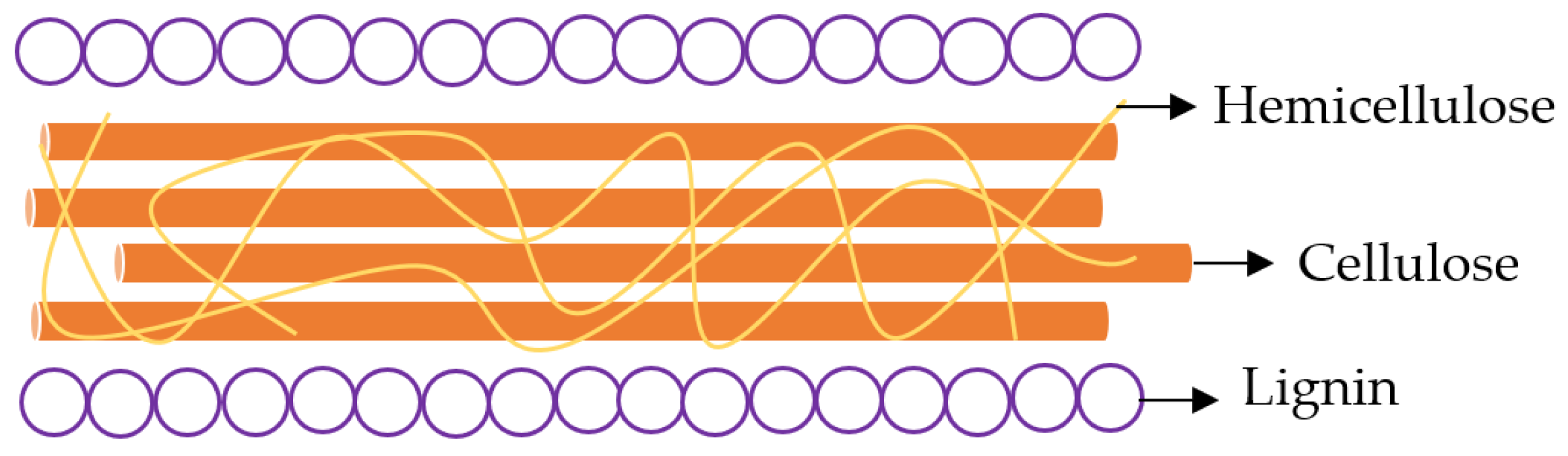

1. Introduction

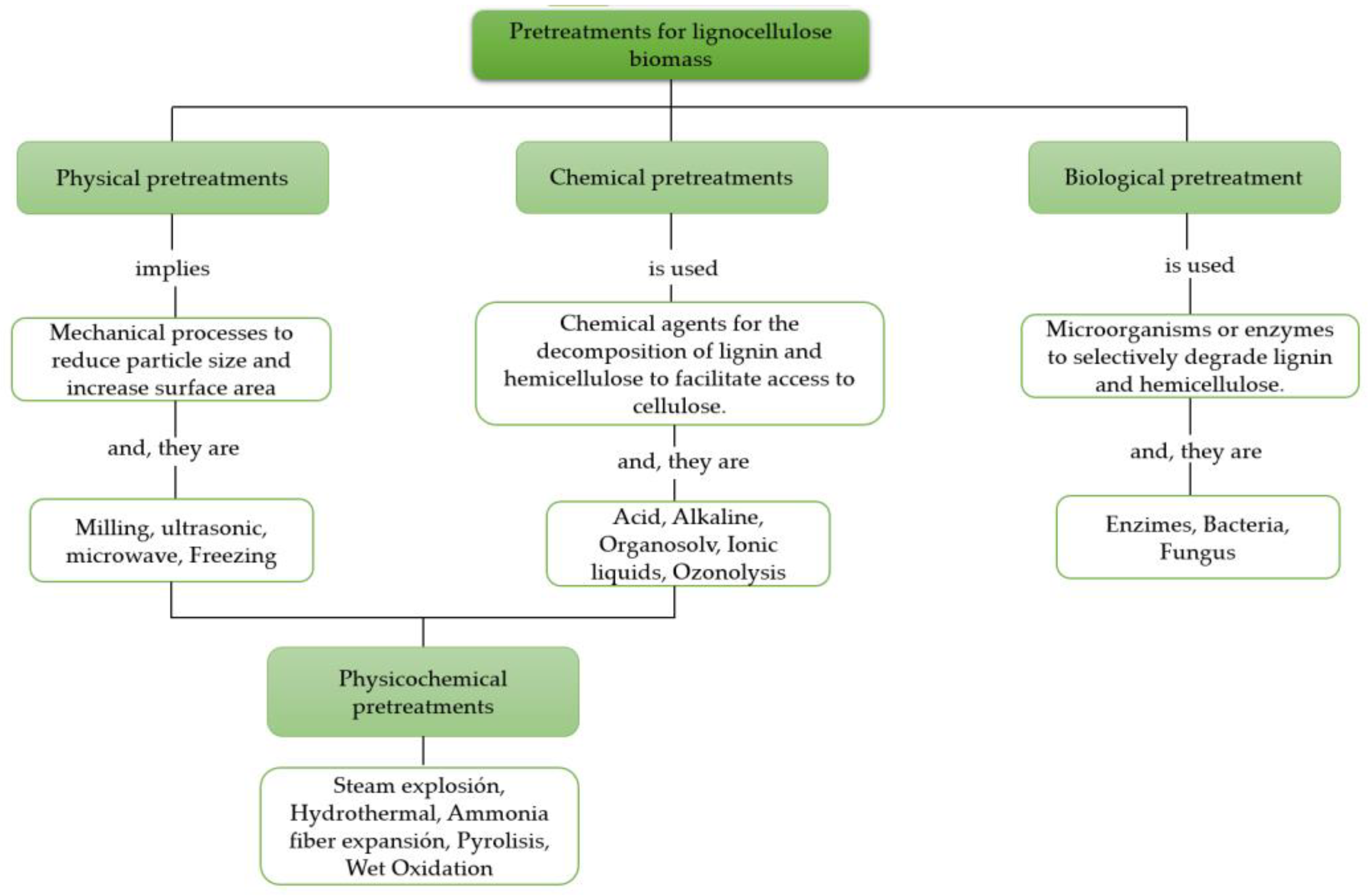

2. Main physical pretreatments for lignocellulose biomass

2.1. Milling pretreatment

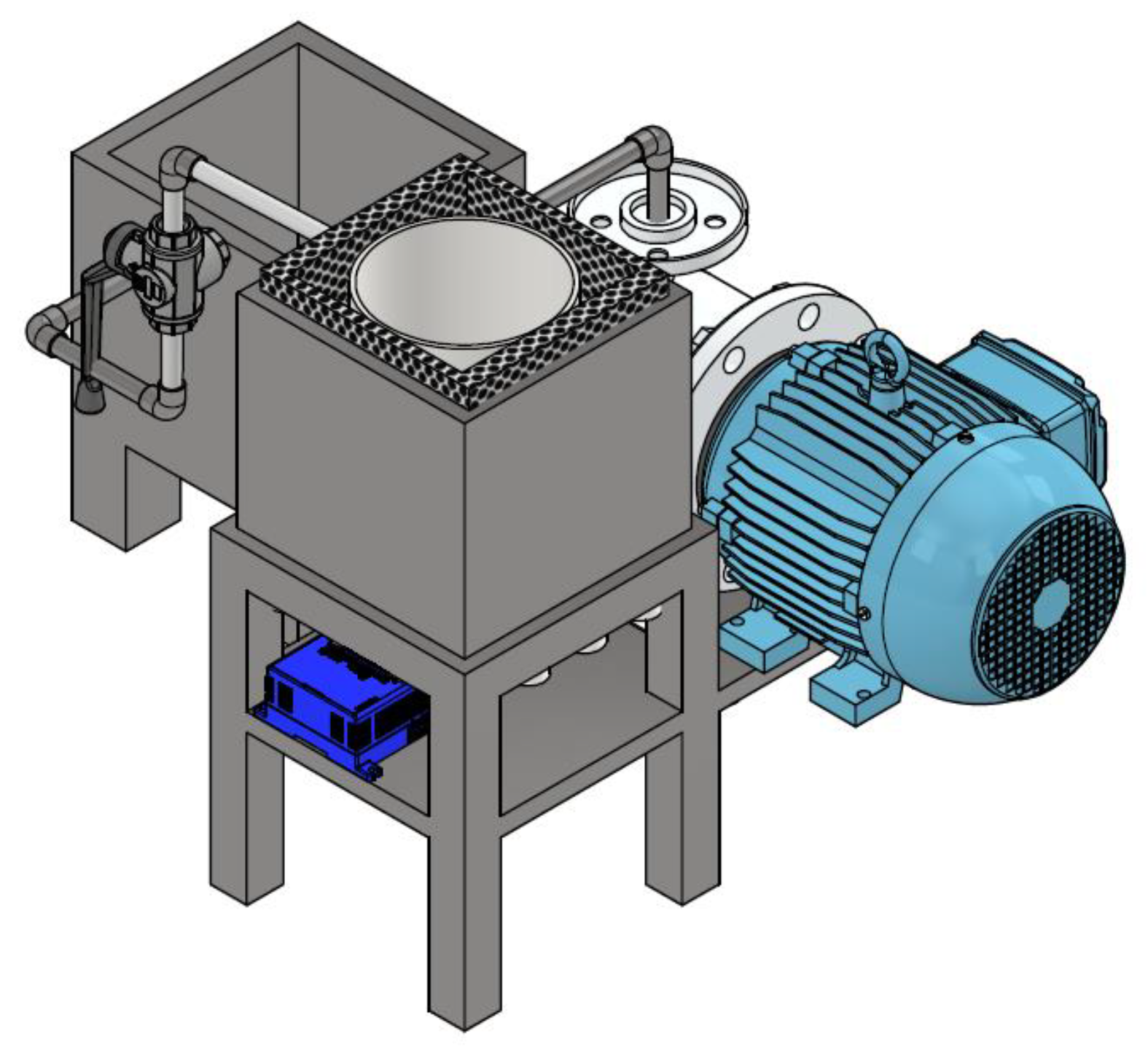

2.2. Ultrasonic pretreatment

2.3. Microwave pretreatment

3. Physical pretreatment applications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Galbe and O. Wallberg, “Pretreatment for biorefineries: a review of common methods for efficient utilisation of lignocellulosic materials,” Biotechnol Biofuels, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 294, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. U. Hernández-Beltrán, I. O. Hernández-De Lira, M. M. Cruz-Santos, A. Saucedo-Luevanos, F. Hernández-Terán, and N. Balagurusamy, “Insight into Pretreatment Methods of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Increase Biogas Yield: Current State, Challenges, and Opportunities,” Applied Sciences, vol. 9, no. 18, p. 3721, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Ojo, “An Overview of Lignocellulose and Its Biotechnological Importance in High-Value Product Production,” Fermentation, vol. 9, no. 11, p. 990, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Banu J, S. Sugitha, S. Kavitha, Y. Kannah R, J. Merrylin, and G. Kumar, “Lignocellulosic Biomass Pretreatment for Enhanced Bioenergy Recovery: Effect of Lignocelluloses Recalcitrance and Enhancement Strategies,” Front Energy Res, vol. 9, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Baruah et al., “Recent Trends in the Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Value-Added Products,” Front Energy Res, vol. 6, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Bajpai, “Background and General Introduction,” 2016, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- S. Singh et al., “Comparison of Different Biomass Pretreatment Techniques and Their Impact on Chemistry and Structure,” Front Energy Res, vol. 2, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. Kumar, D. M. Barrett, M. J. Delwiche, and P. Stroeve, “Methods for Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Efficient Hydrolysis and Biofuel Production,” Ind Eng Chem Res, vol. 48, no. 8, pp. 3713–3729, Apr. 2009. [CrossRef]

- N. Das, P. K. Jena, D. Padhi, M. Kumar Mohanty, and G. Sahoo, “A comprehensive review of characterization, pretreatment and its applications on different lignocellulosic biomass for bioethanol production,” Biomass Convers Biorefin, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 1503–1527, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Jędrzejczyk, E. Soszka, M. Czapnik, A. M. Ruppert, and J. Grams, “Physical and chemical pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass,” in Second and Third Generation of Feedstocks, Elsevier, 2019, pp. 143–196. [CrossRef]

- C. Arce and L. Kratky, “Mechanical pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass toward enzymatic/fermentative valorization,” iScience, vol. 25, no. 7, p. 104610, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. W. Sitotaw, N. G. Habtu, A. Y. Gebreyohannes, S. P. Nunes, and T. Van Gerven, “Ball milling as an important pretreatment technique in lignocellulose biorefineries: a review,” Biomass Convers Biorefin, vol. 13, no. 17, pp. 15593–15616, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. R. C. Fortunato, R. A. da S. San Gil, L. B. Borre, R. da R. O. de Barros, V. S. Ferreira-Leitão, and R. S. S. Teixeira, “Influence of Planetary Ball Milling Pretreatment on Lignocellulose Structure,” Bioenergy Res, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 2068–2080, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen et al., “Structure–property–degradability relationships of varisized lignocellulosic biomass induced by ball milling on enzymatic hydrolysis and alcoholysis,” Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 36, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Brodeur, E. Yau, K. Badal, J. Collier, K. B. Ramachandran, and S. Ramakrishnan, “Chemical and Physicochemical Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass: A Review,” Enzyme Res, vol. 2011, pp. 1–17, May 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Broda, D. J. Yelle, and K. Serwańska, “Bioethanol Production from Lignocellulosic Biomass—Challenges and Solutions,” Molecules, vol. 27, no. 24, p. 8717, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Naresh Kumar, R. Ravikumar, S. Thenmozhi, M. Ranjith Kumar, and M. Kirupa Shankar, “Choice of Pretreatment Technology for Sustainable Production of Bioethanol from Lignocellulosic Biomass: Bottle Necks and Recommendations,” Waste Biomass Valorization, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 1693–1709, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. I. Gavrila et al., “Ultrasound-Assisted Alkaline Pretreatment of Biomass to Enhance the Extraction Yield of Valuable Chemicals,” Agronomy, vol. 14, no. 5, p. 903, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Bussemaker and D. Zhang, “Effect of Ultrasound on Lignocellulosic Biomass as a Pretreatment for Biorefinery and Biofuel Applications,” Ind Eng Chem Res, vol. 52, no. 10, pp. 3563–3580, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- “Combined Ultrasonic and Enzyme treatment of Lignocellulosic Feedstock as Substrate for Sugar Based Biotechnological Applications,” Jul. 01, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Mahmoodi-Eshkaftaki, M. R. Rafiee, and M. Mahmoudi, “Efficiency of Ultrasonic Pretreatment on Improving Biodegradability of Tomato Wastes and Increasing Biohydrogen Production,” Bioenergy Res, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 2590–2603, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Sun, Y. Xu, Y. Ding, Y. Gu, Y. Zhuang, and X. Fan, “Effect of Ultrasound Pretreatment on the Moisture Migration and Quality of Cantharellus cibarius Following Hot Air Drying,” Foods, vol. 12, no. 14, p. 2705, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Pilli, P. Bhunia, S. Yan, R. J. LeBlanc, R. D. Tyagi, and R. Y. Surampalli, “Ultrasonic pretreatment of sludge: A review,” Ultrason Sonochem, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1–18, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Zhengbin He, Zijian Zhao, Fei Yang, and Songlin Yi, “Effect of ultrasound pretreatment on wood prior to vacuum drying,” Maderas. Ciencia y tecnología, 2014.

- M. Rokicka, M. Zieliński, M. Dudek, and M. Dębowski, “Effects of Ultrasonic and Microwave Pretreatment on Lipid Extraction of Microalgae and Methane Production from the Residual Extracted Biomass,” Bioenergy Res, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 752–760, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Guan and Q. Tian, “Ultrasonic pretreatment for Enhancing Sludge disintegration and Resource Utilization: A mini review,” E3S Web of Conferences, vol. 393, p. 01008, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Marta et al., “Evaluation of Ultrasound Pretreatment for Enhanced Anaerobic Digestion of Sida hermaphrodita,” Bioenergy Res, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 824–832, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. M. D. Nora and C. D. Borges, “Ultrasound pretreatment as an alternative to improve essential oils extraction,” Ciência Rural, vol. 47, no. 9, 2017. [CrossRef]

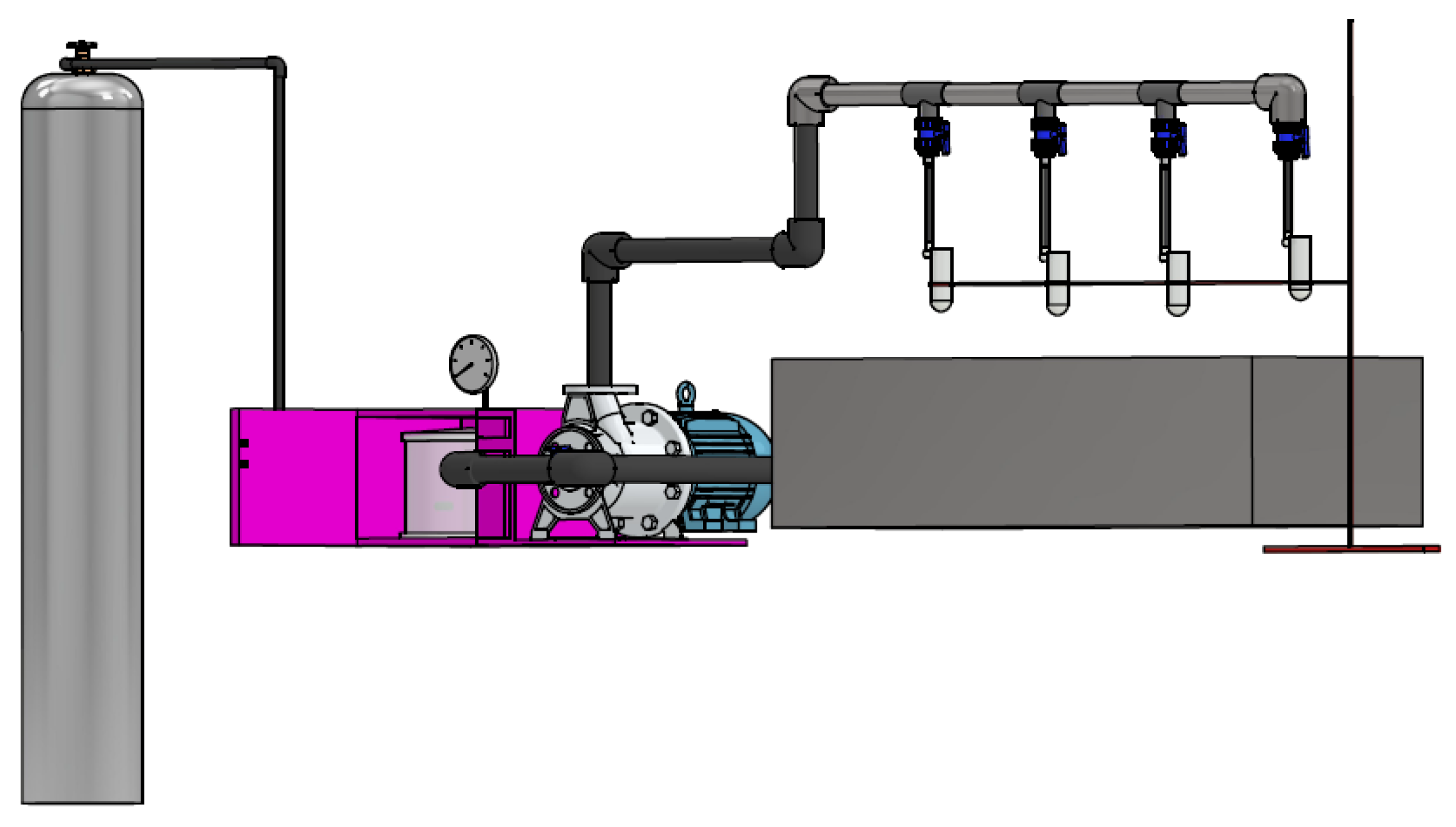

- P. A. Ramirez Cabrera, A. S. Lozano Pérez, and C. A. Guerrero Fajardo, “Innovative Design of a Continuous Ultrasound Bath for Effective Lignocellulosic Biomass Pretreatment Based on a Theorical Method,” Inventions, vol. 9, no. 5, p. 105, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Mikulski and G. Kłosowski, “High-pressure microwave-assisted pretreatment of softwood, hardwood and non-wood biomass using different solvents in the production of cellulosic ethanol,” Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 19, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- SALEEM ETHAIB, R. OMAR, S. M. M. KAMAL, and D. R. A. BIAK, “MICROWAVE-ASSISTED PRETREATMENT OF LIGNOCELLULOSIC BIOMASS: A REVIEW,” Journal of Engineering Science and Technology, 2015.

- N. D. Jablonowski, M. Pauly, and M. Dama, “Microwave Assisted Pretreatment of Szarvasi (Agropyron elongatum) Biomass to Enhance Enzymatic Saccharification and Direct Glucose Production,” Front Plant Sci, vol. 12, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Lozano Pérez, J. J. Lozada Castro, and C. A. Guerrero Fajardo, “Application of Microwave Energy to Biomass: A Comprehensive Review of Microwave-Assisted Technologies, Optimization Parameters, and the Strengths and Weaknesses,” Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, vol. 8, no. 3, p. 121, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Hoang et al., “Insight into the recent advances of microwave pretreatment technologies for the conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into sustainable biofuel,” Chemosphere, vol. 281, p. 130878, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Mikulski and G. Kłosowski, “Delignification efficiency of various types of biomass using microwave-assisted hydrotropic pretreatment,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 4561, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Fernandes, L. Cruz-Lopes, B. Esteves, and D. V. Evtuguin, “Microwaves and Ultrasound as Emerging Techniques for Lignocellulosic Materials,” Materials, vol. 16, no. 23, p. 7351, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. X. Chin, C. H. Chia, S. Zakaria, Z. Fang, and S. Ahmad, “Ball milling pretreatment and diluted acid hydrolysis of oil palm empty fruit bunch (EFB) fibres for the production of levulinic acid,” J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng, vol. 52, pp. 85–92, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. S. da Silva, H. Inoue, T. Endo, S. Yano, and E. P. S. Bon, “Milling pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse and straw for enzymatic hydrolysis and ethanol fermentation,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 101, no. 19, pp. 7402–7409, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- X. Bai, G. Wang, Y. Yu, D. Wang, and Z. Wang, “Changes in the physicochemical structure and pyrolysis characteristics of wheat straw after rod-milling pretreatment,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 250, pp. 770–776, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang et al., “Comparison of various pretreatments for ethanol production enhancement from solid residue after rumen fluid digestion of rice straw,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 247, pp. 147–156, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B.-J. Gu, J. Wang, M. P. Wolcott, and G. M. Ganjyal, “Increased sugar yield from pre-milled Douglas-fir forest residuals with lower energy consumption by using planetary ball milling,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 251, pp. 93–98, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhu et al., “Efficient sugar production from sugarcane bagasse by microwave assisted acid and alkali pretreatment,” Biomass Bioenergy, vol. 93, pp. 269–278, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhu, D. J. Macquarrie, R. Simister, L. D. Gomez, and S. J. McQueen-Mason, “Microwave assisted chemical pretreatment of Miscanthus under different temperature regimes,” Sustainable Chemical Processes, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 15, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Mikulski, G. Kłosowski, A. Menka, and B. Koim-Puchowska, “Microwave-assisted pretreatment of maize distillery stillage with the use of dilute sulfuric acid in the production of cellulosic ethanol,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 278, pp. 318–328, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kumar and P. Verma, “Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Pretreatment of Rice Straw with FeCl3 in Combination with H3PO4 for Improving Enzymatic Hydrolysis,” in Advances in Plant & Microbial Biotechnology, Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2019, pp. 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Tsegaye, C. Balomajumder, and P. Roy, “Optimization of microwave and NaOH pretreatments of wheat straw for enhancing biofuel yield,” Energy Convers Manag, vol. 186, pp. 82–92, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Ramadoss and K. Muthukumar, “Mechanistic study on ultrasound assisted pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse using metal salt with hydrogen peroxide for bioethanol production,” Ultrason Sonochem, vol. 28, pp. 207–217, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Nakashima, Y. Ebi, N. Shibasaki-Kitakawa, H. Soyama, and T. Yonemoto, “Hydrodynamic Cavitation Reactor for Efficient Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass,” Ind Eng Chem Res, vol. 55, no. 7, pp. 1866–1871, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- John, J. Pola, and A. Appusamy, “Optimization of Ultrasonic Assisted Saccharification of Sweet Lime Peel for Bioethanol Production Using Box–Behnken Method,” Waste Biomass Valorization, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 441–453, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Velmurugan and K. Muthukumar, “Ultrasound-assisted alkaline pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse for fermentable sugar production: Optimization through response surface methodology,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 112, pp. 293–299, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. Zhang, J. He, Z. Liu, and Z. Yu, “Combinations of mild physical or chemical pretreatment with biological pretreatment for enzymatic hydrolysis of rice hull,” Bioresour Technol, vol. 100, no. 2, pp. 903–908, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Increased Surface Area | High Energy Consumption |

| Reduced Crystallinity | Capital Costs |

| Improved Processing Efficiency | Potential for Over-Milling |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Variability in Results |

| Eco-Friendly | Limited Effect on Some Biomass Types |

| Type of Mill | Descriptions |

|---|---|

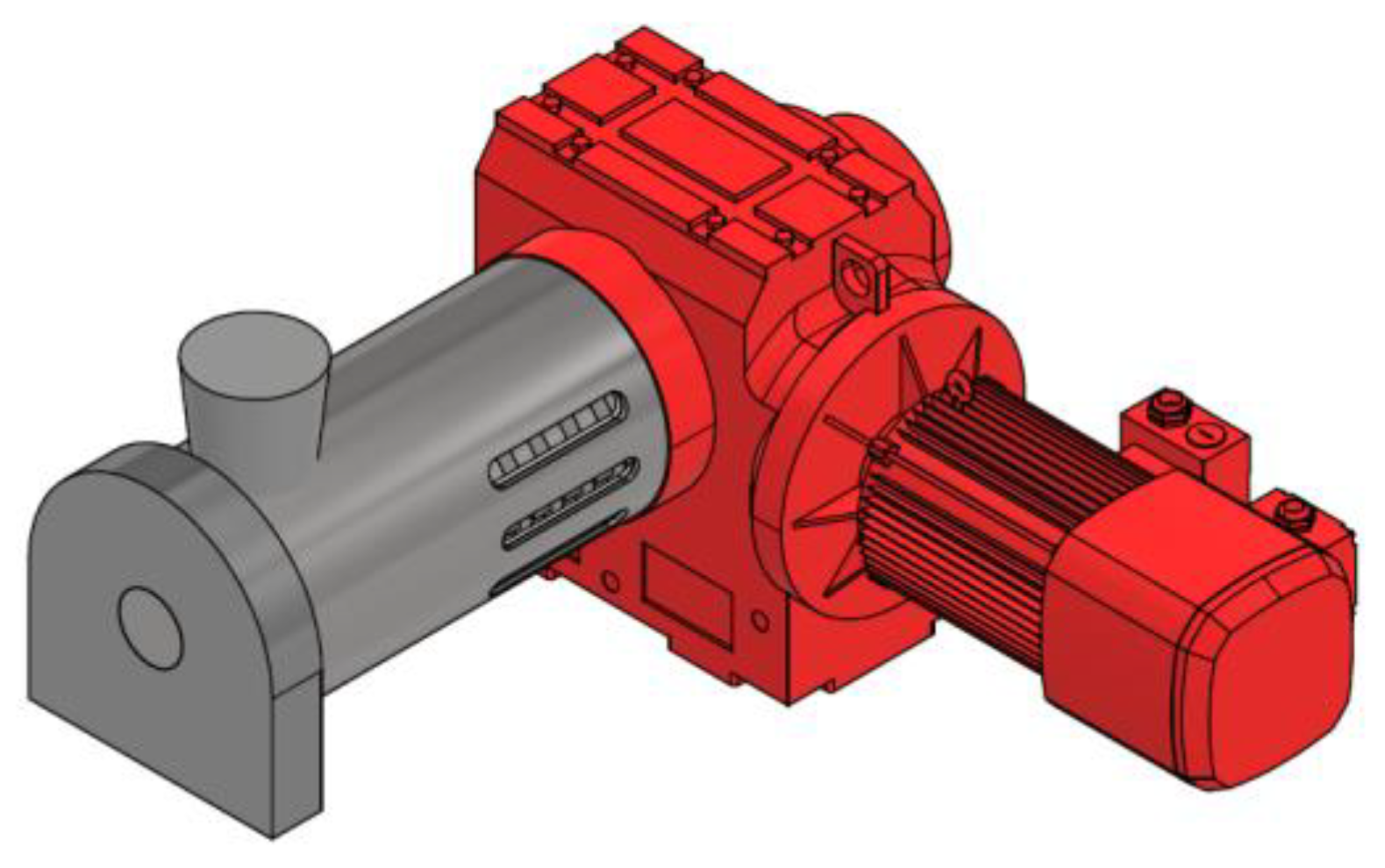

| Knife mill | It is a specialized mill for dry biomass milling where the size of the biomass is reduced with the contact of the static and rotating blades that passes through a sieve to finally be stored in a tank. The efficiency of the mill depends on the moisture content of the biomass, the drier the biomass, the more efficient the cutting and shearing. |

| Hammer mill | It works with a tangential feeding of the biomass to the hammers of the rotor that are in charge of driving the biomass, sending it rotating towards a breaker plate where it is crushed and has an exit towards a sieve. In this process, it is recommended that the biomass has low humidity because it reduces its efficiency. |

| Roll mill | The system works with rollers that rotate in different directions in opposite directions, where they grind by means of compression and tearing mechanisms. The system ensures continuous and constant shredding by introducing biomass between the cylinders. For this type of mill, it is suggested to use brittle and fibrous biomass because when using wet biomass, it can stick to the rollers. |

| Centrifugal mill | This mill works with cutting and breaking mechanisms using a motor with blades that rotate at high speed in a milling chamber. The biomass enters through the upper part of the mill, and when it comes into contact with the blades, it is reduced in size. When cut, the particles are thrown towards the walls of the chamber, which is made of mesh and does not allow the biomass to come out until it is at a very small size. |

| Ball mill | It consists of a cylinder with a central shaft, which rotates at high revolutions, producing size reduction by tearing through friction forces created between the balls inside the cylinder and the cylinder itself. When the speed is low and gradually increases, the biomass reaches the highest centrifugal force and falls thanks to gravity, reducing the particle size through breakage as an additional process. However, ideally the speed should be high enough for the biomass to be distributed throughout the milling chamber to ensure that the process is efficient. |

| Rod mill | This mill has the same characteristics as the previous one, however, the steel balls are replaced by steel rods which reduce the size with abrasion and impact. It is most commonly used for further processing such as pyrolysis and char production. |

| Types of Microwave | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| MAE | It is a technique that combines conventional extraction processes with the energy emitted by microwaves. It is used to improve the extraction of compounds from biomass. It increases the efficiency of solvent extraction by rapidly heating the biomass. It is ideal for polysaccharides and phenolic compounds extraction processes. Also, it requires less reaction time, less solvent and lower costs. |

| MAP | It is a technique of thermal degradation at controlled temperatures and pressures using microwave energy. The efficiency of this process is higher than a conventional pyrolysis process because the heating is done in a uniform way thanks to the microwaves, reducing the reaction time and improving the quality of the product. Also, the heating speeds are faster. |

| MAHT | In this process the biomass is treated with water under high temperature and pressure conditions coming from the microwave. It is a process that has significant lignin reductions and improves biomass availability and yield. Microwave technology helps with uniform and rapid heating to improve mixing and efficiency. It also allows control of parameters such as temperature, time, type of catalyst, amount of biomass, and microwave power. There are different processes ranging from 180°C to 1400°C. |

| MAAH | This technique combines microwave energy with acid catalysts to hydrolyze cellulose into fermentable sugars. Using microwave pretreatment allows the kinetics of the reaction to be accelerated, resulting in higher sugar yields in shorter periods of time compared to traditional methods. |

| High-pressure microwave-assisted | This method employs high pressure coupled with microwave energy to enhance the delignification process of various types of biomass. Studies indicate that the use of high-pressure solvents can significantly increase cellulose content and reduce lignin. The effectiveness of this pretreatment is influenced by factors such as pressure, temperature and duration of treatment. |

| Microwave-assisted organosolv | This process uses organic solvents together with microwave energy to extract lignin from biomass efficiently. The organosolv method can selectively dissolve lignin while cellulose and hemicellulose remain unchanged. |

| Type of pretreatment | Feedstock | Conditions | Results | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ball milling | Oil palm empty fruit bunch | Time: 12 hours | Hidrolisis yield :53.9% levulinic acid | [37] |

| Wet disk milling | Sugar cane bagasse/straw | 20 cycles | Crystanility index: 28/21 % and hydrolisis yield: 44.7/59.5 % | [38] |

| Rod milling | Wheat straw | Times: 30 – 240 minutes | Rod-milling pretreatment reduces the thermal stability of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin in pyrolysis. The most efficient process takes 30 min | [39] |

| Ball milling | Rice straw | Time: 120 minutes | Ball milling pretreatment allowed to obtain ethanol yield of 116.65 mg/g (2.5% digested residues) and 147.42 mg/g (10% digested residues) | [40] |

| Milling | Wood fiber | 0.50–2.15 kWh/kg for 7–30 min at 270 rpm | Product recovered: Glucose and xylose 24.45–59.67 % and 11.92–23.82 % |

[41] |

| Microwave pretreatment | Sugarcane bagasse | Domestic microwave, power output: 1600 W and times between 3-10 minutes | The yields of reducing sugars obtained were higher with microwave-assisted pretreatment and the duration time was shorter. | [42] |

| Microwave pretreatment | Raw Miscanthus | Temperature: 200°C with H2SO4 | Sugar recovery: 73-89% Increases sugar recovery by 17 times higher than conventional heating process. Hemicelullosa reduction: 16 a 25 % |

[43] |

| Microwave pretreatment | Maize distillery stillage | 300 W, 54 PSI, 15 min | 75.8% reducing sugars yield | [44] |

| Microwave pretreatment | Rice straw | 250 mM FeCl3, 3% H3PO4 155 ◦C, 20 min | 98.9% glucan conversion | [45] |

| Microwave pretreatment | Wheat straw | 1.5% NaOH, 160 ◦C, 15 min | Removal of 69.49% lignin and 38.34% of hemicellulose, 74.15% of cellulose recovery, reducing sugars yield of 718 mg/g | [46] |

| Ultrasound | Sugarcane bagasse | 50% amplitude, 70% duty cycle at 75 ◦C, 60 min | 78.72% delignification and 94% holocellulose recovery | [47] |

| Ultrasound | Corn stover | HC-sodium percarbonate, 30 ◦C, 60 min | Relatively higher yield of xylose following enzymatic hydrolysis | [48] |

| Ultrasound assisted dilute acid hydrolysis | Sweet lime peel | Residence time (20e60 min) with sonicator power and frequency of 750 W, and 20 kHz | 181.5 mg/g of reducing sugars and was produced with maximum ethanol yield of 64% | [49] |

| Ultrasound | Sugarcane bagasse | (400 W, 24 kHz)assisted alkali treatment(2.89% NaOH, 70.158C, 47.42min) | 92% reducing sugar yield | [50] |

| Ultrasound | Rice hull | (250 W, 30min) followed by Pleurotusostreatus treatment for 18days | 32% reducing sugar yield | [51] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).