1. Introduction

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology aims to establish a direct link between the brain and external devices. It has the potential to assist, enhance, or restore sensorimotor and cognitive functions, improving the quality of life for individuals with disabilities.[

1] The first structured attempt to create an EEG-based Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) was made by J. Vidal in 1973. He utilized EEG, a non-invasive method originally introduced by Hans Berger, to record the evoked electrical activity of the cerebral cortex through the intact skull.[

2] Brain-computer interface (BCI) technology can be used to treat post-stroke patients by capturing signals from the brain's neural activity with specialized equipment and converting them into commands that a computer can understand.[

3] Over time, the applications of BCI technology have grown, including uses such as brain fingerprinting for lie detection, detecting drowsiness to improve workplace performance, measuring reaction times, controlling virtual reality, operating quadcopters and video games, and managing humanoid robots.[

2,

4]

To achieve our goal in Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology, we need to access brain activity and connect it to our device to visualize its function, much like how EEG represents brain activity as a graph on paper. EEG, or Electroencephalography, involves recording the electrical activity of the brain and presenting it as a graph. EEG provides valuable insights into various brain states and is used to diagnose and manage conditions such as epilepsy, drowsiness, coma, brain injuries, strokes, tumors, behavioral changes, and other neurological disorders.[

5]

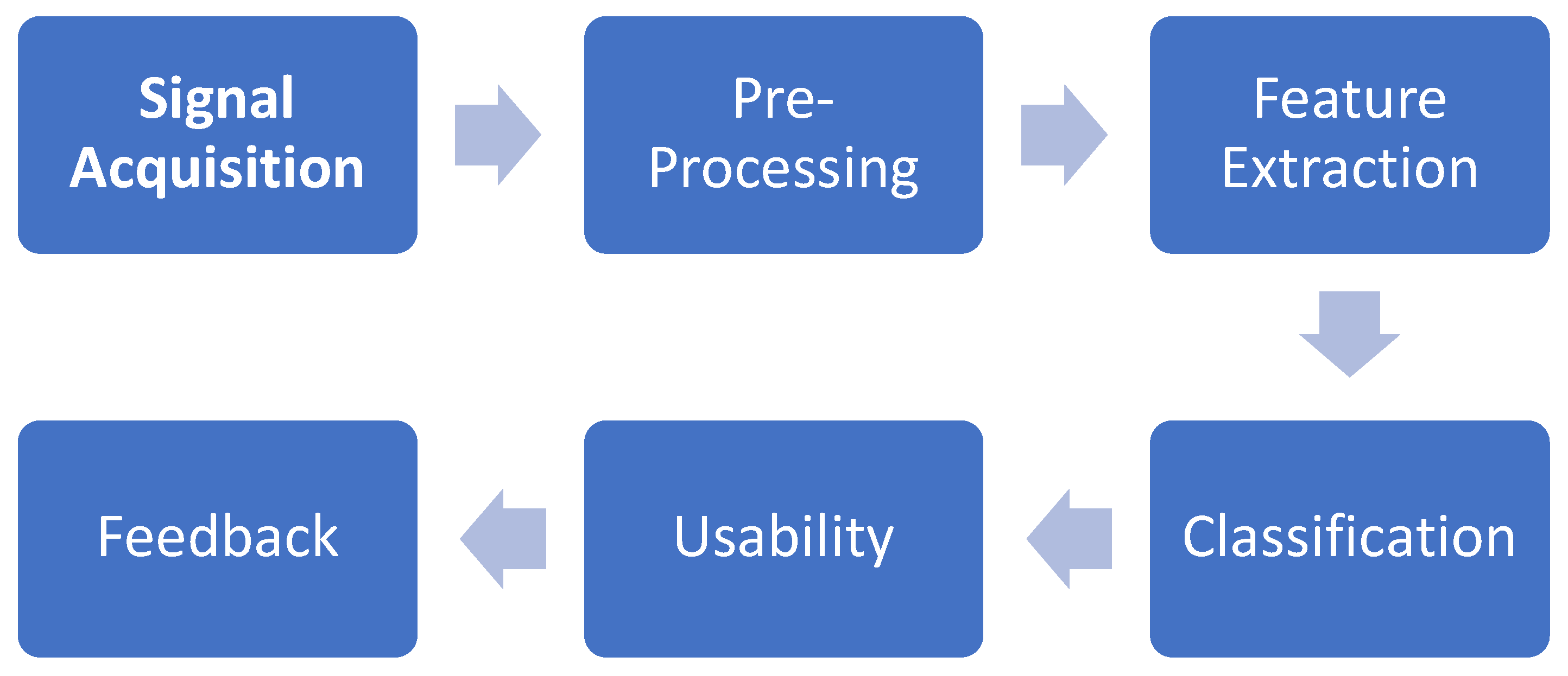

The Brain-computer interface system involves four modules: signal acquisition, pre-preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification.[

6] The first stage involves acquiring the EEG data. The second stage applies well-known processes such as temporal and spatial filtering. The third stage focuses on extracting meaningful features that characterize the selected paradigm. In the classifier stage, a control command is generated using these features extracted from the acquired signal.[

7,

8]

Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) have demonstrated significant potential in motor rehabilitation, especially for individuals with conditions such as stroke, spinal cord injuries, and paraparesis. Numerous applications have been developed that integrate BCIs with EEG technology.

a) Stroke Rehabilitation: BCIs detect movement intentions from the brain, providing feedback to retrain the brain's motor circuits. Studies indicate that BCI-driven

neurofeedback can enhance neuroplasticity, aiding recovery of motor functions such as hand and limb movements.[

4,

9,

10]

b) Upper/Lower Limb Sensorimotor Restoration: For individuals with severe paralysis, BCIs can restore motor function by bypassing damaged neural pathways. These systems can control robotic prosthetics or stimulate paralyzed limbs using neuromuscular electrical

stimulation (ESTIM). Portable and user-friendly BCI designs are critical for enabling real-world applications.[

11,

12]

Key Methods and Techniques:

a) Motor Imagery (MI): Encourages patients to imagine movements, stimulating relevant motor areas in the brain and supporting recovery.[

13]

b) Neurofeedback: Provides real-time visual or sensory feedback during therapy, enhancing the learning process.[

10,

14,

15]

c) Robotic Assistance: BCI-driven exoskeletons and prosthetic limbs enable controlled movements, assisting patients in regaining independence.[

3,

11,

16]

Main paradigms: EEG based BCI systems typically use two main paradigms:

a) Exogenous (Evoked): These use external stimuli like visual or auditory cues (e.g., SSVEP and P300) to evoke brain responses.

b) Endogenous (Spontaneous): These rely on the brain’s self-regulation, like

Motor Imagery (MI), which involves

imagining movement without external triggers.[

16]

2. Materials and Methods

For this review, a detailed literature search was conducted across multiple databases, including IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, Sensor, and Web of Science, using broad search terms like "brain-computer interfaces" (BCI), "Brain Signal acquisition", “Motor Imagery”, “feature extraction", and "EEG". Publications from 2010 onward were considered. Initially, many EEG-related papers were retrieved, but to refine the search, a criterion was applied to exclude works primarily focused on EEG.

The search yielded 223 publications, which were then imported into Mendeley to remove duplicates. After screening the remaining 189 papers based on their titles and abstracts, 96 relevant studies were selected for this review. These studies were focused on BCI development, while those that only discussed theoretical aspects of EEG were excluded.

2.1. Brain Signal Generation

The intricate complexity of the brain has long intrigued scientists, with Santiago Ramón y Cajal making seminal contributions that established him as the "father of modern neuroscience.[

17]" Cajal's pioneering research on the cellular architecture and connectivity of the nervous system culminated in the neuron doctrine, which remains foundational to contemporary neuroscience. This doctrine challenged Camillo Golgi's reticular theory, which posited the nervous system as a continuous network, by demonstrating that nerve cells are discrete anatomical and functional units. Cajal's exceptional ability to deduce dynamic neuronal properties from static observations reflects his profound intellectual acumen and creativity. [

6,

18,

19,

20]

Brain electrical activity is recorded either intracellularly or extracellularly based on electrode placement. Extracellular recordings, corresponding to action potentials (APs), capture signals along axons with frequencies ranging from 100 Hz to 10 kHz and durations of a few milliseconds. [

21]The amplitude of these APs, ranging from 50 to 500 μVpp, depends on the distance between the electrode tip and the recording site [

6].

2.2. Types of Brain Waves in BCIs

a) Delta Waves: Delta waves, with a frequency below 4 Hz, are commonly observed in babies but decrease as they age. In adults, delta rhythms are typically seen only during deep sleep and are uncommon while awake. When delta activity is detected in awake adults, it is usually considered abnormal and may be associated with neurological disorders.[

22]

b) Theta waves: Theta waves (4–8 Hz) are important for overall brain activity and are commonly found in the parietal and temporal lobes. First identified by Wolter and Dovey in 1944, these waves can be used to predict a person's level of attention.[

22] Theta waves are important for predicting self-injurious behavior in women. They are connected to several mental states, including creative thinking, deep meditation, light sleep, daydreaming, and the transition between wakefulness and sleep. Theta waves are also linked to focused attention when solving tasks.[

5]

c) Alpha Waves: Alpha waves, oscillating at 8–13 Hz with amplitudes of 20–100 µV, originate in the occipital lobe and result from synchronized thalamic activity, often triggered by eye closure. Detected in 95% of healthy adults, they have higher amplitudes posteriorly (15–50 µV) and lower in frontal regions.[

23]

Alpha waves, a key feature of brain activity, are employed in BCIs for tasks like relaxation and logical thinking. These systems can convert brain signals into computer commands with high accuracy, offering promising clinical applications. [

24,

25]

By engaging in specific tasks, such as word-based activities, alpha waves can be modulated to create binary communication options, which has proven effective in accurately distinguishing between different intentions [

24]

It is important to note that the α and μ (mu) rhythms share similar frequency ranges, but the μ rhythm is specifically associated with motor cortex activity and is typically non-sinusoidal in nature.[

26] The Motor Brain waves mean α and μ can be interfere with some factor such as External stimulator paradigm, inner talk, and error related potential.

d) Beta Wave: Beta waves are usually observed in the frontal lobe but can appear in other areas when a person is focused or thinking deeply. They have an amplitude of 5–20 μV and occur when the mind is highly active. While alpha waves dominate when the body is relaxed, beta waves increase with heightened emotional or mental activity. In stress or tension, alpha wave amplitude decreases and beta frequency rises, indicating increased alertness or excitement in the brain.[

27]

e) Gamma Wave: Gamma waves, with frequencies ranging from 30 to 80 Hz, are characterized by low amplitude and are rarely detected in EEG signals. Gamma rhythm is associated with motor functions, higher cognitive processes, and the perception of stimuli and memory. [

23]

Some studies showed that EEG signals activities related to sensorimotor rhythms based on MI-BCI systems in the motor cortex area are alpha (a) or mu (m) and beta (14–30 Hz) rhythms.[

28,

29,

30] While, In 2023, Said Abenna et al. conducted a trial involving Delta waves, achieving an accuracy of over 90%.[

31]

Table 1.

Types of Brain Waves in EEG and their frequency and occurrence.[

26].

Table 1.

Types of Brain Waves in EEG and their frequency and occurrence.[

26].

| Rhythm |

Frequency Range |

Occurrence |

| D |

< 4 Hz |

Newborn, Deep sleep |

| Q |

4-8 Hz |

Focused attention, deep meditation, light sleep |

| A |

8–13 Hz |

Relaxation and logical thinking |

| B |

13-30 Hz |

Heightened emotional or mental activity |

| G |

30 < Hz |

Associated with motor functions, higher cognitive processes, and the perception of stimuli and memory |

2.3. Control Signals in BCIs

A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) aims to interpret a user's intentions by monitoring brain activity. Brain signals encompass multiple simultaneous phenomena related to cognitive tasks, many of which remain unclear and their origins unknown. However, certain brain signals have been decoded to the extent that individuals can learn to control them consciously, enabling BCI systems to interpret these signals as control inputs for their intentions.[

22]

The external stimulation paradigm refers to how brain waves can be influenced by external stimuli, such as auditory, visual, or somatosensory inputs. Notable examples include Event-Related Potentials (ERP) and Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials (SSVEP). [

7]

a) One of the most studied ERPs in BCIs is the P300, which is characterized by a positive deflection in the signal occurring around 300 ms after an unexpected stimulus and is mainly measured in the parietal lobe. [

10,

26]

b) Visual Evoked Potential (VEP) is the brain's reaction to visual stimulation, representing the process of visual information handling in the brain. A specific form, Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP), occurs in response to a modulated visual stimulus with a frequency above 6 Hz. SSVEP signals are recorded from the visual cortex using scalp electrodes, with the strongest signals typically detected in the occipital region. Recent research has increasingly focused on SSVEP as a crucial element in Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems due to its stability and reliability.[

7,

32,

33,

34]

BCI systems using external stimulation paradigms have advantages but face limitations. Hybrid BCIs address these by combining multiple paradigms, significantly improving performance. For example, integrating P300 and SSVEP enabled a high-speed speller capable of processing over 100 command codes..[

26]

2.4. Motor Imagery

Motor imagery (MI) involves the mental rehearsal of movement, where an individual consciously engages with the motor representation of an action, including the intention and preparatory processes that are typically unconscious during actual movement [

26]. This process includes imagining specific movements, such as those of the left or right hand, which generates brain signals with distinct temporal and spectral features, making the imagined movements identifiable.[

26,

35] The key physiological markers of motor imagery (MI) are event-related desynchronization (ERD) and event-related synchronization (ERS). These are defined as changes in power within specific frequency bands compared to a baseline period.[

36] For instance, imagining the movement of the left hand reduces the power of the β rhythm in EEG signals over the right motor cortex. This reduction, referred to as event-related desynchronization (ERD), serves as a neural marker for left-hand imagery. Similarly, imagining right-hand movements induces corresponding changes over the left motor cortex [

37,

38,

39]

It has shown that MI-based BCIs can also be used in virtual reality, neurorehabilitation, and robotic devices. For instance, MI-EEG-based BCIs have shown success in controlling robotic arms and exoskeletons, providing prosthetic control for individuals with motor impairments. The potential of MI BCIs has also been explored for post-stroke rehabilitation. Robotic systems using MI-BCIs can guide rehabilitation exercises, helping patients recover motor function more effectively.[

34]

2.5. Signal acquisition

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) enable direct communication between the brain and external devices by interpreting neural signals. Brain signal acquisition methods include:

1) Non-invasive techniques: such as electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG), which prioritize safety and accessibility but have limited spatial resolution.[

40,

41,

42]

1-1) EEG (Electroencephalography): Electrodes are placed on the scalp to measure averaged neuronal signals from various brain regions. EEG systems are portable, affordable, and offer good temporal resolution but have limited spatial resolution due to the interference of physical barriers like the skull and scalp. EEG is also prone to artifacts, such as those from muscle activity or eye movements.[

10,

41,

43,

44]

1-2) MEG (Magnetoencephalography): MEG records neuronal activity through magnetic fields. It offers better spatial resolution than EEG and retains high temporal resolution, making it useful for detecting brain activity with greater accuracy.[

2,

43]

1-3) fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging): fMRI creates 3D brain maps by detecting changes in magnetic fields related to blood oxygenation, providing full brain scans. It offers high spatial resolution but has lower temporal resolution than EEG and MEG, as it measures blood flow rather than direct neural activity.[

2,

45,

46] For example, Amanda Kaas et al. demonstrated a novel somatosensory imagery-based fMRI BCI, achieving high-accuracy single-trial decoding of left-foot versus right-hand imagery.[

47]

1-4) FNIRS (Functional Near Infrared Spectroscopy): This method uses photons to detect oxygenation changes in hemoglobin in cortical areas, offering insights into brain activity. fNIRT (Functional Near Infrared Topography) extends this by creating 3D brain images.[

2,

43,

48,

49] For instance, M. Javad Khan et al. in their trial found that using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) for detecting drowsiness in a passive BCI achieved high classification accuracy.[

48]

1-5) Other Techniques: Additional methods include PET (Positron Emission Tomography), SPECT (Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography), and CT (Computerized Tomography), all of which provide various types of brain imaging with varying levels of resolution.[

2,

50]

2) Invasive methods, like electrocorticography (ECoG) and intracortical recordings, which provide superior signal quality but involve surgical risks.[

6] ECoG surpasses EEG by recording neural activity directly from the cortical surface, reducing tissue damage, offering high spatial resolution with broad brain coverage, and ensuring stability through tolerance to movement. These features make it a robust tool for neuroscience research and clinical applications.[

51]

After the acquisition of Brain signals of motor imagery, it is necessary to process them for BCI application. An EEG-based BCI system for motor imagery (MI) signal recognition processes the acquired signals in multiple stages: pre-processing, feature extraction, feature selection, classification, and performance evaluation.[

6,

43]

Figure 1.

BCI EEG based signal processing.

Figure 1.

BCI EEG based signal processing.

2.6. Preprocessing

Since EEG data is often affected by artifacts such as muscle activity, eye blinks, or movement, pre-processing is a crucial first step to filter out these internal and external disturbances. Effective pre-processing techniques can significantly enhance the quality of EEG signals and improve the performance of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems. Widely used pre-processing techniques for EEG signals include:[

22]

2.6.1. Digital Filters

- Low-pass filters: To remove high-frequency noise.

- High-pass filters: To eliminate low-frequency noise.

- Notch filters: To suppress specific frequency bands, like powerline interference.

2.6.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is widely used across various research fields, including electromyography (EMG), to reduce the dimensionality of sensor data and streamline subsequent analyses. Through an orthogonal rotation, PCA transforms a set of input data channels into a corresponding number of linearly uncorrelated variables, known as Principal Components (PCs). Each PC is calculated to account for the maximum possible portion of the remaining data variance in succession. [

52]

2.6.3. Independent Component Analysis (ICA)

ICA separates independent sources in mixed signals and is often used for artifact removal. Some studies suggest that artifact suppression techniques can sometimes distort the power spectrum of the underlying neural activity, potentially affecting the accuracy of EEG signal interpretation. [

22]

2.6.4. Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD)

EMD is a widely used method for breaking down complex, nonlinear, and non-stationary signals. This technique does not make any assumptions about the input data. In EMD, the signal is separated into several intrinsic modes and a residual. These modes, referred to as Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs), represent the signal's underlying components. [

53,

54]

2.6.5. Normalization

Normalizing the EEG signals can help reduce variability between sessions, making it easier to compare data across different trials.[

55]

2.6.6. Artifact Removal Techniques

- Model-based Methods: Such as linear models to identify and remove artifacts caused by muscle movements or eye blinks.[

56]

- Machine Learning Approaches: Utilizing neural networks to detect and eliminate artifacts effectively.[

57]

2.6.7. Time-Frequency Analysis

- Wavelet Transform: This method allows for simultaneous analysis of signals in both time and frequency domains, providing a richer representation of the EEG data.[

58]

2.6.8. Segmentation and Averaging

- Segmentation: Dividing the signal into smaller segments to facilitate detailed analysis and reduce the impact of artifacts.[

59]

- Averaging: Taking the average of multiple trials to minimize noise and enhance signal clarity.[

60]

By incorporating these pre-processing techniques, including various filtering methods, the quality of EEG signals can be significantly improved, leading to better performance in BCI applications.

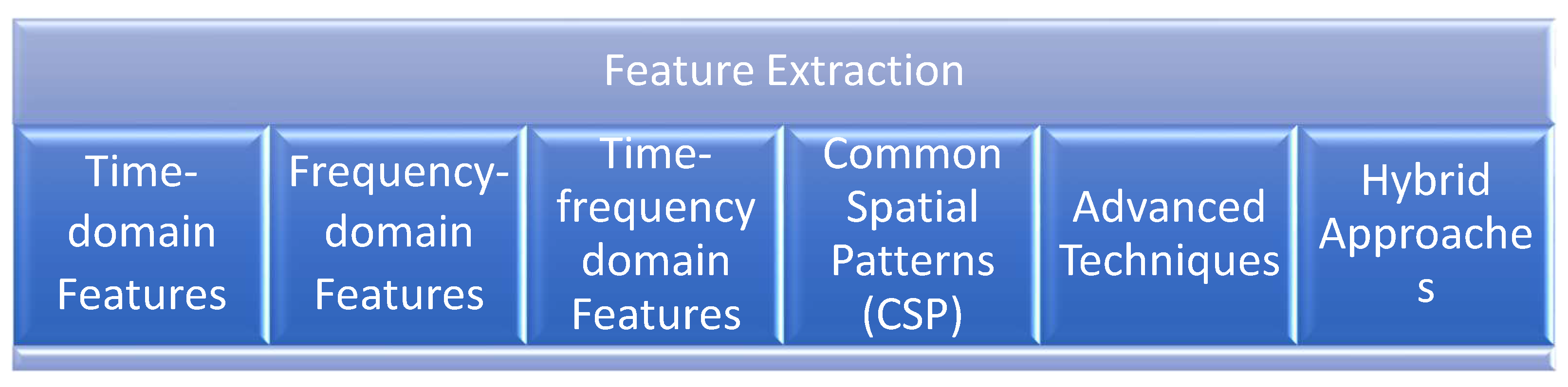

2.7. Feature Extraction Techniques

EEG-based BCI systems extract meaningful information from complex EEG data by applying feature extraction techniques to signals recorded during specific mental tasks.[

43] These extracted features are then used to train classifiers to identify patterns. However, EEG signals are highly non-stationary and affected by various factors like the subject's mental state, session variability, and noise. Additionally, the oscillatory components of EEG signals have distinct, non-stationary characteristics, making accurate classification challenging. As a result, selecting the right feature extraction method is essential to improve the performance of EEG-based BCI systems.

Feature extraction is a critical step in the development of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), as it involves identifying and isolating the most relevant information from electroencephalogram (EEG) signals. Five prominent techniques used in BCI feature extraction are Time Domain Features, Frequency Domain Features, Time Frequency Domain features, Common Spatial Pattern (CSP), and Advanced Techniques.[

61]

Figure 2.

Methods of Features extraction are used in BCI.

Figure 2.

Methods of Features extraction are used in BCI.

2.7.1. Time-Domain Features

Time-domain analyses have long been utilized in the study of brain activity. Most EEG acquisition devices currently available collect data in the time domain. Various techniques are employed to analyze EEG signals within this domain, including:[

27,

43]

2.7.1.1)

Event-Related Potential (ERP): Event-related potentials (ERPs) are low-voltage EEG changes triggered by specific events or stimuli, offering a noninvasive method to study the psychophysiological aspects of sensory, cognitive, and motor activities. They are time-locked to the stimulus, enabling precise measurement of stimulus processing and response times with exceptional temporal resolution. However, ERPs have low spatial resolution and cannot reliably pinpoint the origin of brain activity. Despite this, they are valuable for tracking changes in ERP components over time and space, which aids in adaptive strategies for detecting variable ERPs.[

43]

2.7.1.2)

Statistical features: Statistical characterization of data – mean, standard deviation, mean square error are commonly needed in EEG signal analysis due to their low computational cost. Also, might deviations of the normal distribution be needed, via the mean skewness, and kurtosis error.[

43,

61]

2.7.1.3)

Hjorth feature: This feature introduced in 1970 by Hjorth and It Analyze signal features according to three parameters: activity, mobility, and complexity. In 2021 Seyed Mohammad Mehdi Safi and et al. used this method to detect Alzheimer’s disease more earlier through EEG signals.[

54]

2.7.2. Frequency-Domain Features

Frequency-domain features have proven to be more effective than time-domain features for automatic emotion recognition using EEG. Frequency-domain features are widely used in EEG-based brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) as they analyze amplitude and power variations across different frequency bands. [

61]

2.7.2.1)

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is one of the most commonly used techniques for frequency-domain analysis, particularly for extracting features from short EEG signal segments in emotion recognition tasks [

5,

27]. Also, FFT is a reliable method for signal processing in the form of a sine wave as EEG signals.[

62]

2.7.2.2)

Discrete Fourier Transform and Short-Time Fourier Transform: In the context of EEG-based emotion identification, various Fourier Transform techniques are widely employed, including the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) [

43]. For instance, in 2020, Anton Yudhana et al. applied FFT to identify emotions based on EEG signals [

62].

2.7.3. Time-Frequency Domain

Time-frequency domain enables simultaneous analysis of a signal in both time and frequency domains, providing a detailed representation of its features. The wavelet transform is a prominent technique for such analysis. Other commonly used models for time-frequency domain analysis are also available and will be elaborated on in the next section.[

43,

61] This approach addresses the limitations of conventional time and frequency-domain methods, which are ineffective for analyzing non-stationary EEG signals due to their inability to capture dynamic temporal and frequency details.[

27]

2.7.3.1)

Auto Regressive: AR models are based on the idea that signals tend to be correlated over time or across other dimensions, such as space. This correlation allows for predicting future signal values based on past observations. [

61] Autoregressive (AR) methods are computationally efficient, but they are susceptible to artifacts, which restrict their practical use in Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems.[

63] In this model, the observed data x(n) is derived from a linear system with a transfer function H(z) and is processed through an Autoregressive (AR) model of order p, as described by the equation:[

43]

where ap(i) represents the AR coefficients, x(n) is the observed data, and v(n) is the white noise excitation. This model is effective in characterizing EEG signals, with AR coefficients serving as valuable features for analyzing these signals.[

64]

2.7.3.2)

Wavelet Transform (WT): The Wavelet Transform (WT) is a powerful method for analyzing signals, using a "mother wavelet" as a reference for transformation ([

7]; [

65]). WT works by using large windows for low frequencies and small windows for high frequencies, allowing it to capture both time and frequency details. Two common types used in EEG analysis are the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) and Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT). DWT is more popular because it efficiently breaks signals into parts representing different frequencies while keeping time information. For example, Z.T. Al-Qaysi et al. (2024) and Ebru Sayilgan et al. (2021) both used DWT for feature extraction in their studies.[

7,

66]And Piyush Kant et al. by using Continuous wavelet transform (CWT) organized the signals into two separate bands Mu (8-14Hz) and Beta (15-30Hz) frequency bands.[

67]

2.7.4. Common Spatial Patterns (CSP)

H. Ramoser introduced the Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) method to classify multi-channel EEG data, such as for tasks like imagining hand movements. CSP is widely used in motor imagery-based brain-computer interface (MI-BCI) systems to extract features by applying spatial filtering. This technique maximizes the variance of one class while minimizing that of another, making it easier to distinguish between classes.[

28]

CSP's accuracy depends on electrode placement, as some areas of the scalp capture brain activity better than others. Applying dimensionality reduction before CSP can further enhance its performance.[

43,

61,

68] Researchers have developed several CSP variations to improve its effectiveness, focusing on better channel selection, targeting specific frequency bands, and introducing regularization techniques. For example, Nanxi Yu et al. (2022) proposed Deep CSP (DCSP) to optimize objective functions, while Vasilisa Mishuhina et al. (2021) used a spatio-spectral method to boost CSP performance. [

68,

69] Other advanced CSP methods include Regularized CSP for Selected Subjects (SSRCSP), Spatially Regularized CSP (SRCSP), CSP with Tikhonov Regularization (TRCSP), and CSP with Weighted Tikhonov Regularization (WTRCSP).[

63]

2.7.5. Advanced techniques

Advance techniques leverage machine learning and deep learning methods to enhance the performance of EEG-based Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems. These techniques draw inspiration from the human brain's ability to learn and adapt through interconnected neural pathways.

Deep Learning Models: One of the most prominent approaches in this category is Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). CNNs are designed to automatically learn hierarchical features from raw EEG data, enabling them to capture complex patterns that traditional methods may overlook. An Artificial Neural Network (ANN) typically consists of several layers: an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each layer contains neurons that process the data, allowing the model to learn increasingly abstract representations of the input signals [

70,

71].

For example, Kundu et al. utilized CNNs to detect the P300 signal in EEG data, demonstrating the model's capability to extract both spatial and temporal features effectively. Their CNN architecture included two layers specifically designed to focus on these aspects, facilitating improved detection accuracy of cognitive responses [

72,

73]. The ability of CNNs to process large volumes of data and learn directly from the raw signals makes them particularly well-suited for applications in EEG analysis, where the data can be highly variable and complex.

Moreover, the integration of advanced techniques such as transfer learning and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) can further enhance the performance of deep learning models. Transfer learning allows models trained on large datasets to be fine-tuned for specific tasks with limited data, while RNNs are effective in capturing temporal dependencies in sequential data, making them ideal for analyzing time-series EEG signals. [

72]

2.7.6. Hybrid Approaches

Hybrid approaches in feature extraction involve the integration of multiple techniques to leverage their individual strengths and enhance overall performance in EEG analysis. By combining different feature extraction methods, researchers can create a more comprehensive representation of EEG signals, which can lead to improved classification accuracy and robustness in Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems. One effective strategy is the integration of time-domain and frequency-domain features. Time-domain features capture the temporal characteristics of EEG signals, such as amplitude variations and waveform patterns, which are crucial for understanding the immediate brain responses to stimuli. On the other hand, frequency-domain features analyze the power and distribution of EEG signals across different frequency bands, providing insights into the underlying oscillatory brain activity. For instance, a hybrid model might first extract time-domain features such as Mean Absolute Value (MAV) and Root Mean Square (RMS) to assess the signal's instantaneous characteristics. Subsequently, frequency-domain analysis could be performed using techniques like Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to identify dominant frequency components and their power spectra. By merging these two sets of features, the model can capture both short-term dynamics and long-term frequency patterns, leading to a richer and more informative feature set. Furthermore, hybrid approaches can also incorporate spatial features derived from methods like Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) or Independent Component Analysis (ICA). These spatial techniques can help isolate brain activity from noise and artifacts, enhancing the quality of the extracted features. By integrating spatial, temporal, and frequency-domain features, researchers can develop a multi-faceted representation of EEG signals that captures the complexity of brain activity during various cognitive tasks. Additionally, machine learning algorithms can be employed to optimize the selection and weighting of these combined features. Techniques such as feature selection algorithms or ensemble learning methods can be utilized to identify the most relevant features and reduce dimensionality, ensuring that the model remains efficient while maximizing performance. In summary, hybrid approaches offer a powerful strategy for feature extraction in EEG analysis by combining the strengths of various techniques. This comprehensive representation not only enhances the performance of BCI systems but also paves the way for more sophisticated applications in neurofeedback, emotion recognition, and cognitive state monitoring. [

74,

75,

76]

2.8. Feature Classification

In a Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) system, classification is a crucial step where the system interprets the user's intentions based on processed brain activity data, which has been transformed into a set of features [

14,

77]. Accurate classification enables effective communication between the user and the BCI, allowing for real-time control of devices and applications.

EEG-based BCI tasks are typically classified using a diverse range of classifiers, including:

2.8.1. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA)

A statistical approach that finds a linear combination of features to separate two or more classes of objects. LDA is effective for datasets where classes are linearly separable and is often used in applications like emotion recognition. [

78]

2.8.2. Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (QDA)

Similar to LDA but allows for quadratic decision boundaries, making it suitable for cases where class distributions differ significantly.[

79]

2.8.3. Kernel Fisher Discriminant (KFD)

An extension of LDA that utilizes kernel methods to handle non-linear separations, enhancing performance in complex datasets. [

80]

2.8.4. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

Developed by Vladimir Vapnik, is a supervised machine learning method designed to handle both linear and nonlinear regression and classification tasks. [

13] SVMs have been successfully applied to various fields, including face detection and recognition, disease diagnosis, and text recognition. Known for their intuitive design and strong theoretical foundation, SVMs have proven highly effective in numerous applications.[

27] Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a method that finds the best line or boundary to separate different groups of data. It focuses on key points, called support vectors, to draw the boundary and ignores other points.[

64] SVM makes sure the boundary is as far as possible from the closest points of each group for clear separation. If the data is too complex for a straight line, SVM uses a technique called a kernel to change the data’s shape, making it easier to separate into groups.[

27].[

28]

2.8.5. Learning Vector Quantization (LVQ)

A prototype-based method that classifies data by comparing it to a set of prototypes. LVQ is particularly effective for pattern recognition tasks in EEG data. [

81]

2.8.6. k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN)

A non-parametric method that classifies data points based on the majority class of their nearest neighbors. k-NN is simple to implement and can be effective for small datasets but may struggle with larger, high-dimensional data.[

82]

2.8.7. Decision Trees (DT)

A model that uses a tree-like graph of decisions and their possible consequences. Decision trees are intuitive and easy to interpret, making them suitable for exploratory data analysis.[

14]

2.8.8. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are a powerful machine learning technique inspired by the structure and function of the human brain. ANNs consist of interconnected nodes (neurons) that process data and learn from it. The architecture of an ANN typically includes three main layers:

- Input Layer: Receives raw data, such as EEG signals, images, or text.

- Hidden Layers: Perform complex mathematical operations to identify patterns. The number of hidden layers can vary, with deeper networks often yielding better performance.

- Output Layer: Produces the final classification or prediction based on the processed data.

The connections between nodes are weighted, allowing the network to learn and adapt through training. The performance of an ANN is influenced by parameters such as weights, biases, batch size, and learning rate. During training, the network's error is calculated by comparing predicted outputs with actual outcomes, and backpropagation is employed to adjust weights for improved accuracy [

27,

73].

2.8.8.1. Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)

A type of feedforward artificial neural network that consists of multiple layers of neurons. MLPs are capable of learning complex relationships and patterns within the data through backpropagation, making them suitable for a variety of classification tasks.[

83]

2.8.8.2. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are particularly effective for analyzing EEG signals in BCI applications. They excel in tasks such as detecting fatigue, classifying sleep stages, identifying stress, processing motor imagery, and recognizing emotions. CNNs process brain signals to uncover underlying semantic patterns, enhancing the interpretation of neural activity [

43].

A typical CNN architecture consists of several layers:

Input Layer: Accepts the raw EEG data.

Convolutional Layer: Applies convolution operations to extract features from the input data.

Activation Layer: Introduces non-linearity into the model, allowing it to learn complex patterns.

Pooling Layer: Reduces the dimensionality of the feature maps, retaining essential information while decreasing computational load.

Fully Connected Layer: Connects all neurons from the previous layer to the output layer, providing the final classification.

For example, Alwasiti Haider et al. [

84] utilized a CNN encoder comprising a 7×7 convolutional layer with four dense blocks to classify features effectively in their study.

2.8.8.3. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are specifically designed for processing sequential data, making them ideal for tasks where the order of the input data matters. Unlike traditional feedforward neural networks, RNNs have connections that loop back on themselves, allowing them to maintain a memory of previous inputs. This architecture enables RNNs to identify temporal patterns and dependencies, which is crucial for analyzing time-series data such as EEG signals.

In the context of EEG classification, RNNs can capture the dynamics of brain activity over time, making them particularly effective for tasks like emotion recognition, motor imagery classification, and cognitive state detection. By leveraging their ability to remember past information, RNNs can improve the accuracy of predictions, especially in applications where the timing and sequence of brain activities are significant.

However, standard RNNs can struggle with long-term dependencies due to issues like vanishing gradients. This limitation can hinder their performance in scenarios where information from earlier time steps is essential for understanding current data. [

85,

86]

2.8.8.4. Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs)

Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs) are a specialized type of RNN designed to overcome the limitations of standard RNNs in learning long-term dependencies. LSTMs incorporate a unique architecture featuring memory cells and gating mechanisms that regulate the flow of information. This allows them to retain relevant information over extended sequences while discarding irrelevant data.

The main components of an LSTM include: [

87]

- Forget Gate: Determines what information to discard from the cell state.

- Input Gate: Decides which new information to add to the cell state.

- Output Gate: Controls what information to output from the cell state.

This architecture makes LSTMs particularly suitable for recognizing cognitive states and imagined movements in EEG signals, where the context of earlier brain activity can significantly influence current interpretations. For example, in applications such as brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), LSTMs can effectively differentiate between various mental tasks by analyzing how brain activity evolves over time. [

88]

2.8.8.5. Deep Belief Networks (DBNs)

Deep Belief Networks (DBNs) are composed of multiple layers of stochastic, latent variables, typically organized in a hierarchical manner. They are trained using a layer-wise pretraining approach, which helps in learning complex features from the data effectively. Each layer in a DBN learns to represent the data at different levels of abstraction, enabling the network to capture intricate patterns. DBNs are particularly useful for dimensionality reduction and preprocessing before classification tasks. By compressing the input data into a more manageable form while retaining essential features, DBNs can enhance the performance of subsequent classification models. In EEG applications, DBNs can help in extracting meaningful features from high-dimensional EEG data, facilitating better classification of cognitive states, mental tasks, or emotional responses. [

89]

2.8.8.6. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [

90] are a class of machine learning frameworks consisting of two neural networks: a generator and a discriminator. The generator creates synthetic data, while the discriminator evaluates the authenticity of the generated data against real data. This adversarial process continues until the generator produces data that is indistinguishable from real data. [

91]

In the context of EEG signal classification, GANs can be particularly valuable when real data is scarce. By generating synthetic EEG data that mimics real brain activity, GANs can augment training datasets, improving the performance of classification models. This capability is especially beneficial in applications where obtaining labeled EEG data is challenging or expensive, such as in clinical settings or specialized research studies. [

92]

Moreover, GANs can also be employed to create diverse data scenarios, helping models generalize better in real-world applications. This makes them a powerful tool for enhancing the robustness and accuracy of classification systems in brain-computer interfaces. [

93]

2.9. EEG-Based Output Units or Usability

Electroencephalogram (EEG)-based BCIs offer a promising method for controlling external devices, particularly for individuals with severe motor disabilities. These systems translate brain signals into control commands, enabling users to interact with their environment and assistive devices [

94].

Once the user's intent is classified, it is passed to the execution layer for error approximation. This approximation, based on the device's current state, is used to adjust the actuator to minimize any errors. The execution layer is highly device-specific and may utilize either feedforward or feedback control systems.[

94,

95]

2.10. Shared Control

Shared control combines the user's brain signals with the robotic device’s actions, reducing the need for constant input and making the device move more smoothly. It processes the robot’s data and the user's signals to adjust things like speed. This system is useful in assistive technologies for people with motor impairment, helping them control devices independently. If the user needs help with navigation, the system takes over, while still allowing the user full control when needed. The system also ensures safety by interpreting unclear commands and adapting to new environments.[

16,

94,

96]

3. Conclusions

This review examined the potential of EEG-based Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) utilizing endogenous paradigms, particularly motor imagery (MI). The authors explored various aspects of BCI development, including signal acquisition, processing techniques, and potential applications in neurorehabilitation and assistive technology.

Key findings and takeaways from the review include:

a) Endogenous paradigms such as MI provide user-controlled BCI systems by leveraging self-regulation of brain activity without the need for external stimuli.

b) Non-invasive EEG caps offer an affordable alternative for brain signal acquisition, making them suitable for broader applications despite slightly lower accuracy compared to brain-implanted arrays.

c) Signal processing techniques encompassing pre-processing, feature extraction, and classification are essential for interpreting EEG data and enabling precise control of external devices.

d) Motor imagery (MI) uses imagined movements to produce distinguishable brain patterns, facilitating BCIs in identifying users’ intended actions.

BCIs hold significant promise in:

a) Neurorehabilitation: Empowering individuals with motor impairments to regain control through therapy and prosthetics driven by BCIs.

b) Assistive technology: Providing innovative interfaces for communication and environmental interaction.

The review also highlights the importance of further research and development in BCI technology. Areas for future exploration include:

a) Improved performance: Enhancing the accuracy, speed, and reliability of BCI systems.

b) Advanced feature extraction methods: Utilizing machine learning and deep learning techniques to extract more comprehensive features from EEG data.

c) Hybrid BCIs: Combining different paradigms and feature extraction methods to achieve optimal performance.

d) Brain-machine interfaces (BMIs): Expanding BCI applications beyond control interfaces to facilitate two-way communication between the brain and external devices.

By addressing these challenges and pursuing further research, EEG-based BCIs have the potential to revolutionize various fields, improving the lives of individuals with disabilities and offering novel ways to interact with the world around us.

References

- Hiremath S, V. , Chen W, Wang W, Foldes S, Yang Y, Tyler-Kabara EC, et al. Brain computer interface learning for systems based on electrocorticography and intracortical microelectrode arrays. Front Integr Neurosci. 2015;9:1–10.

- Saha S, Mamun KA, Ahmed K, Mostafa R, Naik GR, Darvishi S, et al. Progress in Brain Computer Interface: Challenges and Opportunities. Front Syst Neurosci. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2021.

- Hramov AE, Maksimenko VA, Pisarchik AN. Physical principles of brain–computer interfaces and their applications for rehabilitation, robotics and control of human brain states. Phys Rep. 2021;918:1–133.

- Ming Z, Bin W, Fan J, Jie C, Wei T. Application of brain-computer interface technology based on electroencephalogram in upper limb motor function rehabilitation of stroke patients. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research. 2024;28:581–6.

- Phanikrishna VB, Jaya Prakash A, Pławiak P, Professor A, Vellore V. A Brief Review on EEG Signal Pre-processing Techniques for Real-Time Brain-Computer Interface Applications. 2014.

- Salahuddin U, Gao PX. Signal Generation, Acquisition, and Processing in Brain Machine Interfaces: A Unified Review. Front Neurosci. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2021.

- Sayilgan E, Yüce YK, İŞler Y. Evaluation of mother wavelets on steady-state visually-evoked potentials for triple-command brain-computer interfaces. Turkish Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences. 2021;25:2263–79.

- Arı E, Taçgın E. Input Shape Effect on Classification Performance of Raw EEG Motor Imagery Signals with Convolutional Neural Networks for Use in Brain—Computer Interfaces. Brain Sci. 2023;13.

- Mane R, Chouhan T, Guan C. BCI for stroke rehabilitation: Motor and beyond. J Neural Eng. 2020;17.

- Lechner A, Ortner R, Guger C. Feedback strategies for BCI based stroke rehabilitation: Evaluation of different approaches. Biosystems and Biorobotics. 2014;7:507–12.

- Bockbrader, M. Upper limb sensorimotor restoration through brain–computer interface technology in tetraparesis. Curr Opin Biomed Eng. Elsevier B.V.; 2019. p. 85–101.

- Schmitt MS, Wright JD, Triolo RJ, Charkhkar H, Graczyk EL. The experience of sensorimotor integration of a lower limb sensory neuroprosthesis: A qualitative case study. Front Hum Neurosci. 2023;16.

- Sharma R, Kim M, Gupta A. Motor imagery classification in brain-machine interface with machine learning algorithms: Classical approach to multi-layer perceptron model. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2022;71:103101.

- Varsehi H, Firoozabadi SMP. An EEG channel selection method for motor imagery based brain–computer interface and neurofeedback using Granger causality. Neural Networks. 2021;133:193–206.

- Singh J, Ali F, Gill R, Shah B, Kwak D. A Survey of EEG and Machine Learning-Based Methods for Neural Rehabilitation. IEEE Access. 2023;11:114155–71.

- Padfield N, Camilleri K, Camilleri T, Fabri S, Bugeja M. A Comprehensive Review of Endogenous EEG-Based BCIs for Dynamic Device Control. Sensors. MDPI; 2022.

- Zeng, H. What is a cell type and how to define it? Cell. Elsevier B.V.; 2022. p. 2739–55.

- Di Bella DJ, Domínguez-Iturza N, Brown JR, Arlotta P. Making Ramón y Cajal proud: Development of cell identity and diversity in the cerebral cortex. Neuron [Internet]. 2024;112:2091–111. Available from. [CrossRef]

- de Castro F, Merchán MA. Editorial: The major discoveries of cajal and his disciples: Consolidated milestones for the neuroscience of the XXIst century. Front Neuroanat. Frontiers Research Foundation; 2016.

- Lui JH, Hansen D V., Kriegstein AR. Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell. Elsevier B.V.; 2011. p. 18–36.

- Gidon A, Zolnik TA, Fidzinski P, Bolduan F, Papoutsi A, Poirazi P, et al. Dendritic action potentials and computation in human layer 2/3 cortical neurons. Science (1979) [Internet]. 2020;367:83–7. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Nicolas-Alonso LF, Gomez-Gil J. Brain computer interfaces, a review. Sensors. 2012. p. 1211–79.

- Banach K, Małecki M, Rosół M, Broniec A. Brain-computer interface for electric wheelchair based on alpha waves of EEG signal. Bio-Algorithms and Med-Systems. 2021;17:165–72.

- Nishifuji S, Yasunaga K, Matsubara A, Nakashima S. Brain Computer Interface Using Response of Alpha Wave to Word Task. 2021 IEEE 10th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE). 2021. p. 244–7.

- Zhao H, Wang H, Liu C, Li C. Brain-computer interface design using alpha wave. ProcSPIE [Internet]. 2010. p. 75000G. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Saibene A, Caglioni M, Corchs S, Gasparini F. EEG-Based BCIs on Motor Imagery Paradigm Using Wearable Technologies: A Systematic Review. Sensors. MDPI; 2023.

- Houssein EH, Hammad A, Ali AA. Human emotion recognition from EEG-based brain–computer interface using machine learning: a comprehensive review. Neural Comput Appl. Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH; 2022. p. 12527–57.

- Pawan, Dhiman R. Machine learning techniques for electroencephalogram based brain-computer interface: A systematic literature review. Measurement: Sensors. 2023;28.

- Aldea R, Eva OD. Detecting sensorimotor rhythms from the EEG signals using the independent component analysis and the coefficient of determination. ISSCS 2013 - International Symposium on Signals, Circuits and Systems. 2013.

- Wang K, Tian F, Xu M, Zhang S, Xu L, Ming D. Resting-State EEG in Alpha Rhythm May Be Indicative of the Performance of Motor Imagery-Based Brain–Computer Interface. Entropy. 2022;24.

- Abenna S, Nahid M, Bouyghf H, Ouacha B. An enhanced motor imagery EEG signals prediction system in real-time based on delta rhythm. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2023;79:104210.

- Cecotti H, Graser A. Convolutional Neural Networks for P300 Detection with Application to Brain-Computer Interfaces. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2011;33:433–45.

- Nicolas-Alonso LF, Gomez-Gil J. Brain computer interfaces, a review. Sensors. 2012. p. 1211–79.

- Palumbo A, Gramigna V, Calabrese B, Ielpo N. Motor-imagery EEG-based BCIs in wheelchair movement and control: A systematic literature review. Sensors. MDPI; 2021.

- Kumar S, Sharma A, Tsunoda T. Brain wave classification using long short-term memory network based OPTICAL predictor. Sci Rep. 2019;9.

- Zhong Y, Yao L, Pan G, Wang Y. Cross-Subject Motor Imagery Decoding by Transfer Learning of Tactile ERD. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering. 2024;32:662–71.

- Resalat SN, Saba V. A Study of Various Feature Extraction Methods on a Motor Imagery Based Brain Computer Interface System. 2016.

- Gwon D, Ahn M. Alpha and high gamma phase amplitude coupling during motor imagery and weighted cross-frequency coupling to extract discriminative cross-frequency patterns. Neuroimage. 2021;240.

- Deng H, Li M, Li J, Guo M, Xu G. A robust multi-branch multi-attention-mechanism EEGNet for motor imagery BCI decoding. J Neurosci Methods. 2024;405.

- Grau C, Ginhoux R, Riera A, Nguyen TL, Chauvat H, Berg M, et al. Conscious brain-to-brain communication in humans using non-invasive technologies. PLoS One. 2014;9.

- Liu H, Wei P, Wang H, Lv X, Duan W, Li M, et al. An EEG motor imagery dataset for brain computer interface in acute stroke patients. Sci Data. 2024;11.

- Erat K, Şahin EB, Doğan F, Merdanoğlu N, Akcakaya A, Durdu PO. Emotion recognition with EEG-based brain-computer interfaces: a systematic literature review. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024.

- Mridha MF, Das SC, Kabir MM, Lima AA, Islam MR, Watanobe Y. Brain-computer interface: advancement and challenges. Sensors. MDPI; 2021.

- Mahmoud Saadabi, DM. Non-Invasive Brain-Computer Interface Technology (BCI) Modalities and Implementation: A Review Article and Assimilation of BCI Models. Annals of Advanced Biomedical Sciences. 2021;4.

- Rui Z, Gu Z. A Review of EEG and fMRI Measuring Aesthetic Processing in Visual User Experience Research. Comput Intell Neurosci. Hindawi Limited; 2021.

- Mazrooyisebdani M, Nair VA, Loh PL, Remsik AB, Young BM, Moreno BS, et al. Evaluation of changes in the motor network following bci therapy based on graph theory analysis. Front Neurosci. 2018;12.

- Kaas A, Goebel R, Valente G, Sorger B. Topographic Somatosensory Imagery for Real-Time fMRI Brain-Computer Interfacing. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;13.

- Khan MJ, Hong K-S. Passive BCI based on drowsiness detection: an fNIRS study. Biomed Opt Express. 2015;6:4063.

- Buccino AP, Keles HO, Omurtag A. Hybrid EEG-fNIRS asynchronous brain-computer interface for multiple motor tasks. PLoS One. 2016;11.

- Zhu Y, Xu K, Xu C, Zhang J, Ji J, Zheng X, et al. PET mapping for brain-computer interface stimulation of the ventroposterior medial nucleus of the thalamus in rats with implanted electrodes. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2016;57:1141–5.

- Xie Y, Peng Y, Guo J, Liu M, Zhang B, Yin L, et al. Materials and devices for high-density, high-throughput micro-electrocorticography arrays. Fundamental Research. KeAi Communications Co.; 2024.

- Artoni F, Delorme A, Makeig S. Applying dimension reduction to EEG data by Principal Component Analysis reduces the quality of its subsequent Independent Component decomposition. Neuroimage. 2018;175:176–87.

- Rilling G, Flandrin P, Gonçalvès P. ON EMPIRICAL MODE DECOMPOSITION AND ITS ALGORITHMS.

- Safi MS, Safi SMM. Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease from EEG signals using Hjorth parameters. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2021;65.

- Apicella A, Isgrò F, Pollastro A, Prevete R. On the effects of data normalization for domain adaptation on EEG data. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;123:106205.

- Mohammadpour M, Rahmani V. A Hidden Markov Model-based approach to removing EEG artifact. 2017 5th Iranian Joint Congress on Fuzzy and Intelligent Systems (CFIS). 2017. p. 46–9.

- Stalin S, Roy V, Shukla PK, Zaguia A, Khan MM, Shukla PK, et al. A Machine Learning-Based Big EEG Data Artifact Detection and Wavelet-Based Removal: An Empirical Approach. Math Probl Eng. 2021;2021:2942808.

- Adeli H, Zhou Z, Dadmehr N. Analysis of EEG records in an epileptic patient using wavelet transform. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;123:69–87.

- Barlow, JS. Methods of analysis of nonstationary EEGs, with emphasis on segmentation techniques: a comparative review. Journal of clinical neurophysiology. 1985;2:267–304.

- Mouraux A, Iannetti GD. Across-trial averaging of event-related EEG responses and beyond. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26:1041–54.

- Pawar D, Dhage S. Feature Extraction Methods for Electroencephalography based Brain-Computer Interface: A Review. 2020.

- Yudhana A, Muslim A, Wati DE, Puspitasari I, Azhari A, Mardhia MM. Human emotion recognition based on EEG signal using fast fourier transform and K-Nearest neighbor. Advances in Science, Technology and Engineering Systems. 2020;5:1082–8.

- Sadiq MT, Yu X, Yuan Z. Exploiting dimensionality reduction and neural network techniques for the development of expert brain–computer interfaces. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;164:114031.

- Rasheed, S. A Review of the Role of Machine Learning Techniques towards Brain–Computer Interface Applications. Mach Learn Knowl Extr. MDPI; 2021. p. 835–62.

- Djamal EC, Fadhilah H, Najmurrokhman A, Wulandari A, Renaldi F. Emotion brain-computer interface using wavelet and recurrent neural networks. International Journal of Advances in Intelligent Informatics. 2020;6:1–12.

- Al-Qaysi ZT, Suzani MS, Bin Abdul Rashid N, Ismail RD, Ahmed MA, Wan Sulaiman WA, et al. A Frequency-Domain Pattern Recognition Model for Motor Imagery-Based Brain-Computer Interface. Applied Data Science and Analysis. 2024;2024:82–100.

- Kant P, Laskar SH, Hazarika J, Mahamune R. CWT Based Transfer Learning for Motor Imagery Classification for Brain computer Interfaces. J Neurosci Methods. 2020;345.

- Nanxi Yu 1 2, Rui Yang 1, and Mengjie Huang 1,*. Deep Common Spatial Pattern Based Motor Imagery Classification with Improved Objective Function. 2022.

- Mishuhina V, Jiang X. Complex common spatial patterns on time-frequency decomposed EEG for brain-computer interface. Pattern Recognit. 2021;115:107918.

- Kaushalya Kumarasinghea b,∗, NKDT. DeeplearninganddeepknowledgerepresentationinSpikingNeural NetworksforBrain-ComputerInterfaces. 2020.

- Alwasiti H, Yusoff MZ, Raza K. Motor Imagery Classification for Brain Computer Interface Using Deep Metric Learning. IEEE Access. 2020;8:109949–63.

- Kundu S, Ari S. P300 based character recognition using convolutional neural network and support vector machine. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2020;55:101645.

- Trakoolwilaiwan T, Behboodi B, Lee J, Kim K, Choi J-W. Convolutional neural network for high-accuracy functional near-infrared spectroscopy in a brain–computer interface: three-class classification of rest, right-, and left-hand motor. Neurophotonics. 2017;5:1.

- Sun Z, Huang Z, Duan F, Liu Y. A Novel Multimodal Approach for Hybrid Brain-Computer Interface. IEEE Access. 2020;8:89909–18.

- Chugh N, Aggarwal S. Hybrid Brain–Computer Interface Spellers: A Walkthrough Recent Advances in Signal Processing Methods and Challenges. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 2023;39:3096–113.

- Liu Z, Shore J, Wang M, Yuan F, Buss A, Zhao X. A systematic review on hybrid EEG/fNIRS in brain-computer interface. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2021;68:102595.

- Yadav D, Yadav S, Veer K. A comprehensive assessment of Brain Computer Interfaces: Recent trends and challenges. J Neurosci Methods. 2020;346:108918.

- Dos Santos EM, San-Martin R, Fraga FJ. Comparison of subject-independent and subject-specific EEG-based BCI using LDA and SVM classifiers. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2023;61:835–45.

- Ozkan Y, Barkana BD. Multi-class Mental Task Classification Using Statistical Descriptors of EEG by KNN, SVM, Decision Trees, and Quadratic Discriminant Analysis Classifiers. 2020 IEEE 5th Middle East and Africa Conference on Biomedical Engineering (MECBME). IEEE; 2020. p. 1–6.

- Li M, Zhang P, Yang G, Xu G, Guo M, Liao W. A fisher linear discriminant analysis classifier fused with naïve Bayes for simultaneous detection in an asynchronous brain-computer interface. J Neurosci Methods. 2022;371:109496.

- Djamal EC, Abdullah MY, Renaldi F. Brain computer interface game controlling using fast fourier transform and learning vector quantization. Journal of Telecommunication, Electronic and Computer Engineering (JTEC). 2017;9:71–4.

- Alom MK, Islam SMR. Classification for the P300-based brain computer interface (BCI). 2020 2nd international conference on advanced information and communication technology (ICAICT). IEEE; 2020. p. 387–91.

- Rasheed, S. A review of the role of machine learning techniques towards brain–computer interface applications. Mach Learn Knowl Extr. 2021;3:835–62.

- Alwasiti H, Yusoff MZ, Raza K. Motor Imagery Classification for Brain Computer Interface Using Deep Metric Learning. IEEE Access. 2020;8:109949–63.

- Setiawan SA, Djamal EC, Nugraha F, Kasyidi F. Brain-Computer Interface of Emotion and Motor Imagery Using 2D Convolutional Neural Network—Recurrent Neural Network. 2022 5th International Conference on Information and Communications Technology (ICOIACT). IEEE; 2022. p. 391–6.

- Yang S-H, Huang J-W, Huang C-J, Chiu P-H, Lai H-Y, Chen Y-Y. Selection of essential neural activity timesteps for intracortical brain–computer interface based on recurrent neural network. Sensors. 2021;21:6372.

- Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput [Internet]. 1997;9:1735–80. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Selvi AO, Ferikoğlu A, GÜZEL D. Classification of P300 based brain computer interface systems using longshort-term memory (LSTM) neural networks with feature fusion. Turkish Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences. 2021;29:2694–715.

- Wang S, Luo Z, Zhao S, Zhang Q, Liu G, Wu D, et al. Classification of EEG Signals Based on Sparrow Search Algorithm-Deep Belief Network for Brain-Computer Interface. Bioengineering. 2023;11:30.

- Goodfellow I, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial nets. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2014;27.

- Fahimi F, Dosen S, Ang KK, Mrachacz-Kersting N, Guan C. Generative adversarial networks-based data augmentation for brain–computer interface. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2020;32:4039–51.

- Song Y, Yang L, Jia X, Xie L. Common spatial generative adversarial networks based EEG data augmentation for cross-subject brain-computer interface. arXiv preprint arXiv:210204456. 2021.

- Fahimi F, Zhang Z, Goh WB, Ang KK, Guan C. Towards EEG generation using GANs for BCI applications. 2019 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical & Health Informatics (BHI). IEEE; 2019. p. 1–4.

- Tariq M, Trivailo PM, Simic M. EEG-Based BCI Control Schemes for Lower-Limb Assistive-Robots. Front Hum Neurosci. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2018.

- Rico-Azagra J, Gil-Martínez M. Feedforward of measurable disturbances to improve multi-input feedback control. Mathematics. 2021;9.

- Qasim M, Ismael OY. Shared Control of a Robot Arm Using BCI and Computer Vision. Journal Europeen des Systemes Automatises. 2022;55:139–46.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).