1. Introduction

The management of VTE, [

1] has become increasingly complex since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with a heightened risk of thrombotic complications, including both venous and arterial thrombosis, attributed to a prothrombotic state driven by excessive inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and hypercoagulability [

2,

3,

4]. COVID-19 patients, particularly those hospitalized, are at increased risk for VTE events such as DVT and PE, with incidents documented even in cases receiving standard prophylactic anticoagulation [

5,

6].

One characteristic feature in COVID-19 patients is microvascular pulmonary thrombosis and in situ thrombosis, suggesting a form of thrombotic microangiopathy, which complicates clinical management [

7]. Management strategies for VTE in COVID-19 typically involve anticoagulation, with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) as the commonly used initial treatment due to its efficacy and safety profile [

8,

9]. However, the optimal anticoagulation dosage and duration remain contentious, with some guidelines advocating for intermediate or therapeutic doses in critically ill patients to reduce thrombotic complications [

4,

10,

11]. Recent research has highlighted that COVID-19 can exacerbate DVT progression, especially among patients undergoing anticoagulant therapy. This risk appears particularly elevated in individuals with distal DVT or those who have completed a shorter, three-month course of anticoagulation. These findings suggest that the interplay between COVID-19 and DVT, especially under anticoagulation treatment, may require more prolonged or intensive management strategies to mitigate the risk of thrombotic complications in affected patients [

12].

Systemic corticosteroids, particularly dexamethasone, have also been utilized to reduce mortality in severe COVID-19 cases by mitigating the hyperinflammatory response associated with advanced disease stages [

13,

14]. This anti-inflammatory approach has shown benefits in reducing mortality, especially in patients requiring oxygen therapy or mechanical ventilation.

This study aims to retrospectively evaluate the efficacy of anticoagulant and corticosteroid regimens in reducing mortality among patients diagnosed with DVT and COVID-19. Data were analyzed from patients treated at a high-complexity hospital over a follow-up period of 6 months. Variables analyzed include sex, age, baseline and peak INR levels, baseline and peak platelet counts, maximum D-dimer levels, and Sepsis-Induced Coagulopathy (SIC) scores. Control groups without COVID-19 or PE were included to provide rigorous comparisons, thereby reducing potential confounding factors and enabling a more precise evaluation of the relationship between treatments and mortality outcomes [

15,

16].

2. Materials and Methods

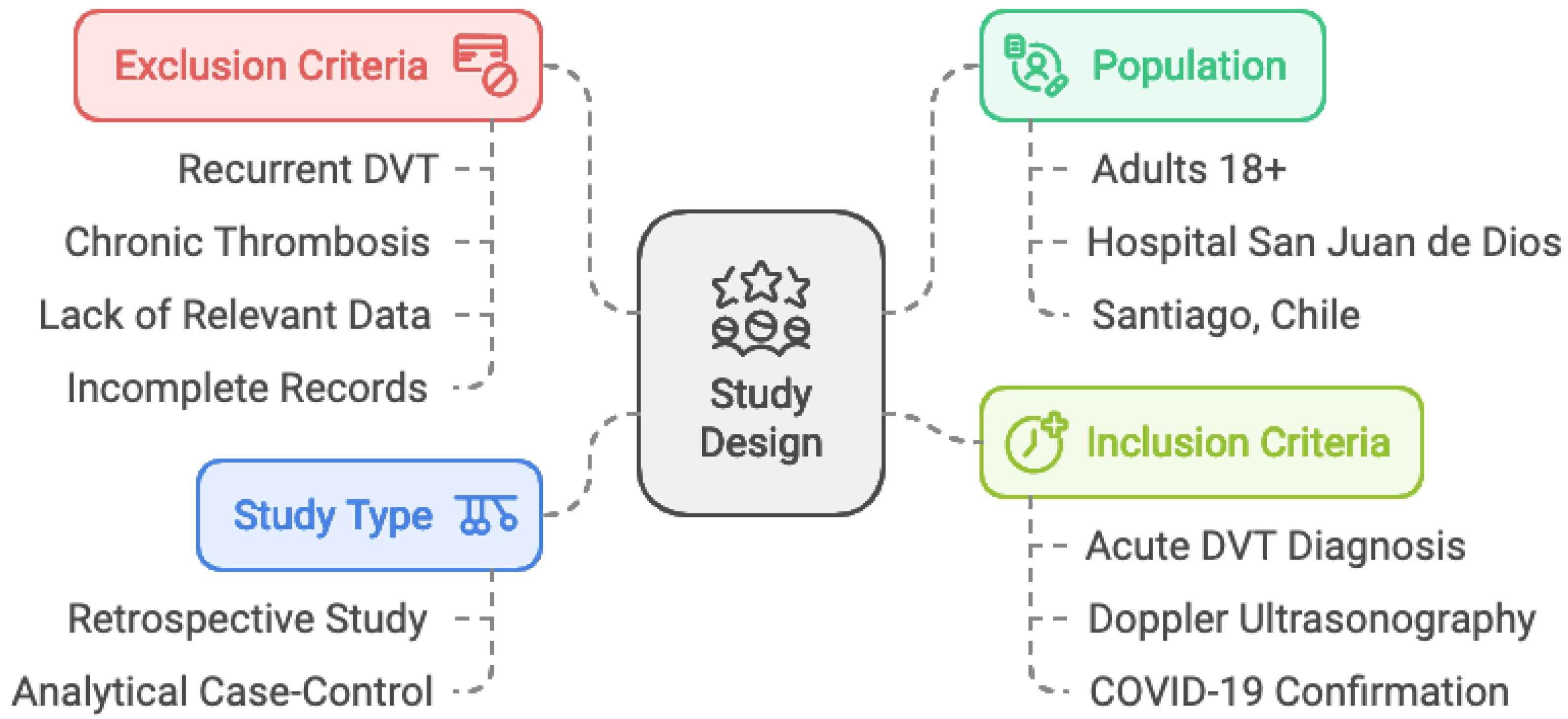

2.1. Study Design

This study is a retrospective, analytical case-control study conducted at Hospital San Juan de Dios, a high-complexity hospital. The study aimed to evaluate the impact of anticoagulant and corticosteroid therapies on mortality in patients with DVT and COVID-19. A six month follow-up period was used to analyze the outcomes of patients with and without COVID-19 and PE, focusing on the association between treatment regimens, progression to PE, and mortality.

2.2. Selection of Cases and Controls

The study population included adult patients (18 years or older) who were admitted to the hospital between June 2016 and July 2022, with a diagnosis of acute DVT confirmed by Doppler ultrasonography of the lower extremities. Patients were categorized into three main treatment groups: anticoagulants, corticosteroids with anticoagulants, and prophylaxis/no anticoagulation. The control group consisted of patients who had DVT but did not have COVID-19, while patients with COVID-19 but no DVT were excluded from the analysis. Exclusion criteria included patients with recurrent DVT episodes, chronic thrombosis, incomplete medical records, or missing key laboratory data such as INR levels, platelet count, or D-dimer levels.To ensure rigorous comparisons, the study also included a subgroup analysis based on baseline demographic characteristics (age, sex) and co-morbidities, adjusting for potential confounders in treatment efficacy [

16].

2.3. Data Collection

The study was approved by the hospital’s Scientific Ethics Committee (CEC), adhering to the Helsinki Declaration and Chilean patient rights laws. Given the retrospective nature of the study, anonymized data was used, and informed consent was waived by the CEC.

Patient data were extracted from electronic medical records and included demographic variables (age, sex), baseline and peak INR levels, baseline and peak platelet counts, maximum D-dimer levels, and Sepsis-Induced Coagulopathy (SIC) scores [

17]. Additionally, the data collected included the presence or absence of PE and COVID-19 diagnosis during hospitalization, treatment regimens (anticoagulants and corticosteroids), and patient mortality outcomes, including the cause of death and time to mortality. See

Figure 1.

The SIC score was calculated conservatively, using a SOFA score of zero for all patients. The SIC score was derived by summing INR and platelet count scores as follows:

-

INR score:

- a.

0 points if INR ≤ 1.1

- b.

1 point if INR > 1.2 and ≤ 1.4

- c.

2 points if INR > 1.4

-

Platelet count score:

- a.

0 points if platelet count (PLT) ≥ 150

- b.

1 point if PLT ≥ 100 and < 150

- c.

2 points if PLT < 100

The SIC score was derived by summing these two parameters for each patient.

2.4. Diagnosis of PE and DVT

Patients with suspected acute DVT underwent lower extremity venous Doppler ultrasound using a vascular transducer. The diagnosis of acute DVT was confirmed if the following criteria were met: 1) absence of compressibility in at least one segment of the deep venous system, accompanied by another sign of altered distal venous flow, or 2) visible thrombus associated with dilation of the same segment of the deep venous system, along with a sign of altered distal venous flow.

Patients with a clinical suspicion of PE underwent pulmonary artery computed tomography angiography (CTA). CTA was performed using both 16- and 64-slice scanners, following the injection of 70-90 mL of isosmolar contrast medium. The bolus tracking technique was employed with a trigger threshold set between 160 and 250 HU in the pulmonary arterial trunk. Images were reconstructed with a slice thickness of 1 mm in both pulmonary and mediastinal windows. Radiological reports were reviewed, and the location of the PE was classified based on the site of the most proximal luminal defect.

2.5. Clinical Management Guidelines

In the management of DVT and PE, full-dose dalteparin was administered, with dosage adjustments based on weight and renal function. Specifically, dalteparin was given at a dose of 100 UI/kg, twice daily, via subcutaneous injection, with a maximum dose of 10,000 UI twice daily. In cases of renal impairment (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min), unfractionated heparin was administered at a therapeutic dose, aiming for an activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) target of 1.5 to 2 times the control value.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using R software (v. 4.2.3) within RStudio (v. 1.2.5033).

Descriptive Statistics: Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the study population. Continuous variables, such as age, INR levels, and SIC scores, were described using measures of central tendency and variation, including mean, standard deviation, and range. Categorical variables, such as sex, were summarized with frequency distributions [

24,

26]. We summarize the statistical analysis approach in

Figure 2.

Effect of Demographic Characteristics: To address potential confounding effects of demographic factors like age and sex, these variables were included in all analyses. Stratified analyses and interaction terms in regression models were utilized to explore differences in treatment efficacy across demographic subgroups [

16,

18].

2.7. Treatment Comparison

ANOVA: To assess differences in continuous outcomes (e.g., survival time, INR levels) across treatment groups, adjusting for demographic covariates such as age and sex. Post-hoc comparisons were conducted to identify specific group differences [

16].

Survival Analysis: Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to compare survival rates across treatment groups. The log-rank test was used to assess the statistical significance of differences between groups. A stratified analysis based on age and sex was performed to examine whether treatment effects varied across different demographic subgroups [

19,

20].

Cox Proportional-Hazard Models: Cox regression models were fitted to estimate hazard ratios for mortality. These models included demographic covariates (e.g., age, sex) and interaction terms to assess the potential modifying effects of these factors on treatment outcomes [

18,

21].

2.8. Logistic Regression for PE Conversion and Mortality

Logistic Models: Binary logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) for outcomes such as PE conversion and mortality. Age, sex, and other demographic factors were included as covariates to control for their influence on the outcomes. Interaction terms between treatments and demographic characteristics were tested to explore any differential effects [

18].

Fisher’s Exact Test: This test was used to evaluate the significance of coefficient estimates, especially for small sample sizes, and adjustments were made for demographic characteristics [

18].

2.9. Analysis of INR and SIC Scores

Effect on Mortality: Logistic regression and Cox proportional-hazards models were used to evaluate the impact of baseline INR levels, SIC scores, and changes in INR (ΔINR) on mortality. These models included age and sex as covariates, ensuring that the conclusions accounted for potential demographic confounding. Subgroup analyses were performed to identify differential effects based on age and sex [

16].

Categorization and Threshold Effects: INR and SIC were analyzed both as continuous variables and by categorizing them into clinically relevant thresholds. The analysis examined how these variables influenced mortality outcomes across different demographic groups [

16,

22].

2.10. Relationships Between Treatments, Causes of Death, PE and COVID-19 Status

Overall Treatment and Cause of Death: Calculate the distribution of death causes across different treatments.

Separating by PE Status: Identify any patterns in death causes specific to patients with and without PE.

Separating by COVID-19 Status: Examine if COVID-19 status affects the distribution of death causes with respect to treatment types.

Effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals were reported for all tests, with Bonferroni correction applied to account for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 [

23,

24].

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 300 patients were included in the study, with a mean age of 65.3 years (SD ± 15.4), and 55.3% were male.

Table 1 provides a summary of the baseline characteristics. Patients were grouped by their treatment regimens, and no significant differences were found in baseline characteristics, including sex, age, INR levels, platelet counts (PLT), and SIC scores across the treatment groups (p > 0.05). The majority of patients received anticoagulant therapy (40.3%), while 22.7% received corticosteroids, and 37.0% were under prophylaxis or received no anticoagulation treatment. See

Table 1.

3.2. Clinical Outcomes and Treatment Comparisons

The overall mortality rate across all patients was 30.7%. The survival analysis revealed significant differences between treatment groups (log-rank p = 0.01). Patients treated with anticoagulants alone had a mortality rate of 20.8%, compared to 29.6% in those treated with a combination of anticoagulants and corticosteroids. When comparing survival times using ANOVA, there were significant differences across the treatment groups (p = 0.02), with patients receiving both anticoagulants and corticosteroids showing longer survival times compared to those who received anticoagulants alone (post-hoc pairwise comparison p < 0.05). Age was found to be a significant covariate influencing mortality risk (p < 0.05).

3.3. PE vs. No PE

Patients who developed PE had a significantly higher mortality rate (40.2%) compared to those without PE (25.4%) (log-rank p < 0.001). Survival analysis demonstrated shorter survival times in patients without PE (median survival = 2.3 months) compared to those with PE (median survival = 5.7 months). Interaction analysis showed that the effect of PE on mortality was more pronounced in patients who did not receive anticoagulation treatment (p < 0.05), suggesting that anticoagulant therapy had a protective effect against mortality in PE patients.

3.4. COVID-19 vs. No COVID-19

The mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with COVID-19 (38.5%) compared to non-COVID-19 patients (21.8%) (log-rank p < 0.001). COVID-19-positive patients had a shorter survival time (median survival = 1.55 months) compared to those without COVID-19 (median survival = 4 months). Interaction analysis revealed that the combination of anticoagulants and corticosteroids significantly improved survival in COVID-19 patients (p < 0.05), whereas non-COVID-19 patients did not show significant differences between treatment groups.

3.5. Interactions Between PE, COVID-19, and Treatments

A significant association was observed between COVID-19 status and PE development. Interestingly, contrary to previous findings [

5,

8,

27], COVID-19-positive patients were significantly less likely to develop PE (OR = 0.383, p = 0.00004). Specifically, in our data, when neither COVID-19 nor PE was present, there were 139 cases. In contrast, 133 cases were observed where COVID-19 was absent, but PE was present. Among COVID-19-positive individuals, 82 cases had no PE, while 30 cases exhibited both conditions. This unexpected trend warrants further investigation, particularly concerning the influence of treatments and preventive measures administered to COVID-19 patients.

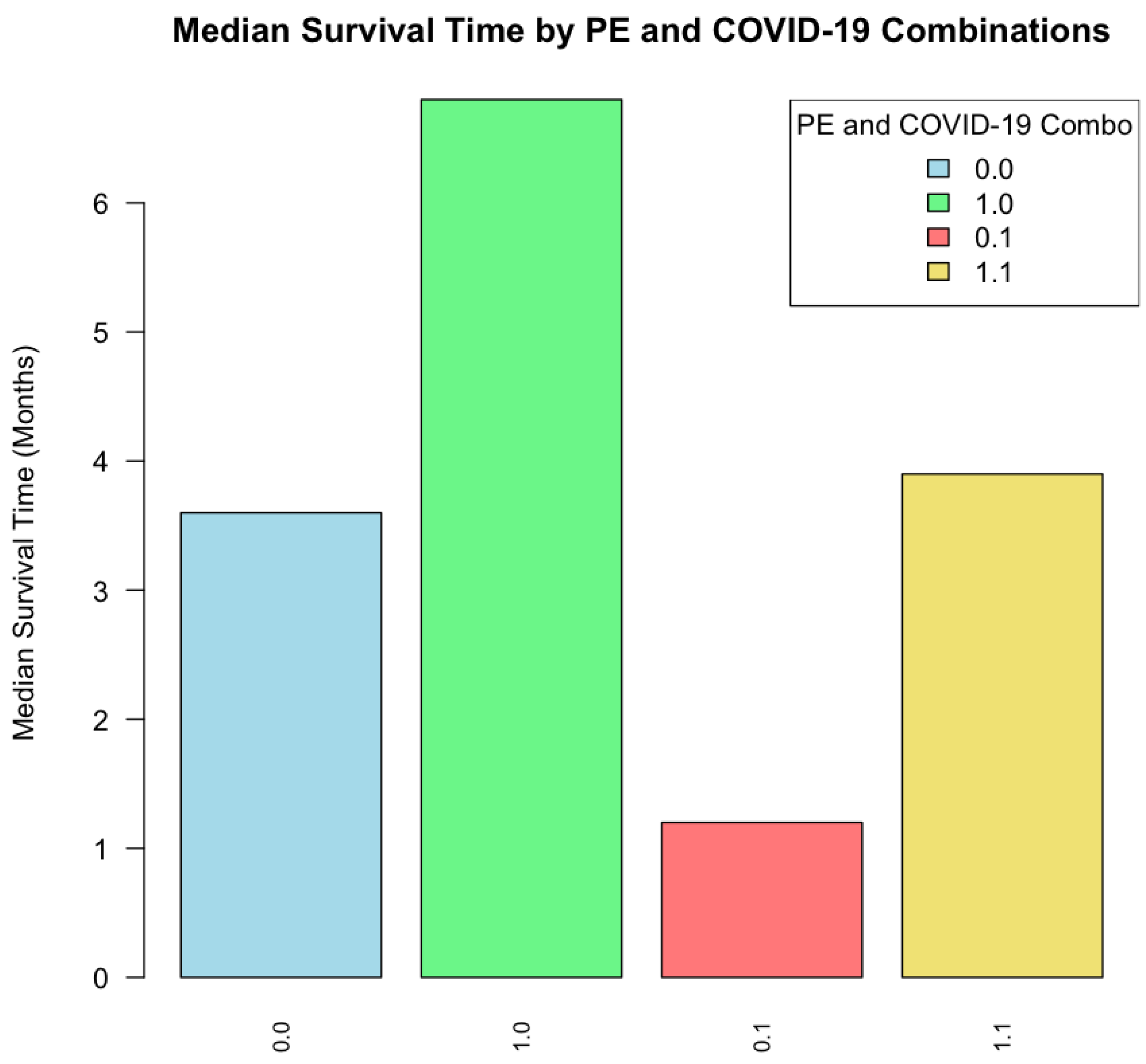

When analyzing the interactions between PE and COVID-19 status, patients with both PE and COVID-19 had the highest mortality rate (45.8%) compared to patients with only PE (33.7%) or only COVID-19 (30.1%). The combined presence of PE and COVID-19 was not associated with the shortest median survival (3.9 months), but it was obtained in COVID-19 positive without PE (1.2 months). See

Figure 3.

Regarding median survival time, as reference when No Treatment recorded it was 0.75 months, the longest was 4 months, for anticoagulants, while for Corticosteroid it was 0.9 months and for Prophylaxis 2 months. Pairwise Comparison between Anticoagulants Only vs. Prophylaxis or No Treatment is lowly significant (p = 0.088) but vs. Corticosteroid or No Treatment is significant.

In terms of treatment interactions, anticoagulant therapy was associated with improved survival outcomes in patients with either PE or COVID-19 (median survival 9 months vs. 1.49 without treatment), but the effect was strongest in those with both conditions (4.5 months vs. 0.2 with Prophylaxis). Patients treated with anticoagulants or corticosteroids had significantly lower mortality in both PE and COVID-19 subgroups (log-rank p < 0.01 for both). Furthermore, prophylaxis or no anticoagulation was associated with poorer outcomes, particularly in patients with both PE and COVID-19, with a mortality rate of 55.3% in this group (p < 0.001).

These results suggest that anticoagulant and corticosteroid therapy is essential in improving survival outcomes, especially in patients with PE, COVID-19, or both conditions. Interaction effects highlight the need for personalized treatment strategies, as certain combinations of conditions and treatments may dramatically affect patient survival. See

Table 2. Survfit curves for different PE-COVID-19-Treatment combinations, as well as R codes for survival and Cox Proportional-Hazard Models in

Supplementary Material.

3.6. Cox Proportional-Hazard Models

The Cox proportional hazards model statistics indicate a good fit and predictive accuracy for the Cox proportional hazards model. The concordance index (0.634, SE = 0.032) suggests a moderate level of agreement between predicted and observed survival outcomes. Significant values in the likelihood ratio test (χ

2 = 27.03, p = 0.0007), Wald test (χ

2 = 32.18, p = 0.00009), and score (logrank) test (χ

2 = 36.73, p = 0.00001) confirm that the model’s covariates collectively have a strong impact on survival, underscoring the relevance of the variables included in predicting patient outcomes. See coefficient statistics in

Table 3.

It reveals significant associations between certain variables and survival outcomes:

COVID-19 Status: COVID-19 status shows a significant hazard ratio of 2.709 (p = 0.002), indicating that patients with COVID-19 have a significantly higher risk of mortality. This finding suggests that COVID-19 substantially increases mortality risk in this patient cohort.

-

Treatment Type:

- a.

Corticosteroids show a reduced hazard ratio but it is not significant,

- b.

Anticoagulation is associated with a reduced hazard ratio of 0.4219 (p = 0.037), suggesting a protective effect on survival.

- c.

Prophylaxis shows a highly reduced hazard ratio of 0.129 (p = 0.00006), suggesting a high protective effect on survival. Patients receiving anticoagulants or prophylactic treatment have a lower risk of mortality compared to other groups.

Sex: sex effect was lowly significant (p = 0.073) as evidence of a low tendency to higher risk of mortality in men than in women.

Age: it doesn’t significantly impact survival after adjusting for other variables.

PE Status: PE status also did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.369), indicating that it may not independently affect mortality risk in this analysis.

3.7. Associations Between Variables

Pearson’s correlation analysis indicated a significant positive correlation between baseline INR levels and SIC scores (r = 0.48, p < 0.001). Similarly, elevated SIC scores were associated with increased mortality (OR: 1.89, 95% CI: 1.43-2.50). The correlation analysis for age demonstrated a positive correlation with mortality (r = 0.39, p < 0.01), highlighting its importance as a covariate.

Chi-square tests showed a significant association between COVID-19 status and PE conversion (χ

2 = 15.62, p < 0.001), with patients infected by COVID-19 more likely to develop PE. Logistic regression further confirmed this association (OR: 3.47, 95% CI: 2.01-5.97). See

Table 4.

3.8. Effect of INR and SIC Scores on Mortality

Logistic regression models revealed that higher baseline INR levels and higher SIC scores were independently associated with increased mortality (p < 0.01 for both). After adjusting for demographic characteristics (age, sex), the adjusted odds ratios remained significant, with the odds of mortality increasing by 1.72 (95% CI: 1.29–2.28) for every unit increase in SIC score.

3.9. Relationship Between SIC Scores and Mortality

Patients with higher SIC scores had significantly elevated mortality rates. Specifically, those with an SIC score of 2 or more had a mortality rate of 41.7%, compared to 23.5% for patients with an SIC score of less than 2 (log-rank p < 0.001). Cox proportional-hazard analysis confirmed that each unit increase in SIC score was associated with a 2.03-fold increase in mortality risk (HR: 2.03, 95% CI: 1.49–2.76, p < 0.001).

Patients with SIC scores that included both elevated INR levels (INR > 1.4) and low platelet counts (<100,000/µL) exhibited the highest mortality risk, with a mortality rate of 46.5%. In contrast, patients with normal platelet counts and INR levels had a mortality rate of 19.2%, indicating that the combination of elevated SIC components (INR and platelets) significantly increases mortality risk (p < 0.01 for interaction effect).

3.10. INR and SIC Score Changes During the Study Period

In addition, patients who experienced a substantial increase in INR levels during the study period (ΔINR > 0.3) demonstrated higher mortality rates (HR: 2.15, 95% CI: 1.48–3.13, p < 0.01). This effect was more pronounced in older patients and males, further suggesting the need for demographic-specific management strategies.

3.11. Relationships Between Treatments, Causes of Death, PE and COVID-19 Status

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7 give a summary of the relationships observed between treatments and causes of death, with further separation by PE and COVID-19 status.

Anticoagulants Only treatment has the highest association with cancer-related deaths (OR 3.2 p <0.05, higher than observed with other treatments), particularly in non-PE patients. COVID-19 deaths are more prevalent in those who received no anticoagulation or prophylaxis only treatments (OR 15.6 p <0.001), especially among COVID-19 positive patients.

Sepsis is primarily associated with the anticoagulants only treatment in non-PE patients (OR 6.2 p <0.01) without COVID-19 (OR 2.2), but it is less common in COVID-19 positive patients. Corticosteroids are linked to increased cancer-related mortality (OR 1.45 less significant), being particularly pronounced in PE patients.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

This study examined the effects of anticoagulant and corticosteroid therapies on survival and PE risk in patients with deep DVT and COVID-19. Among 300 patients analyzed, those receiving anticoagulants showed significantly improved survival compared to those on corticoids or prophylaxis treatment.

The apparently contradictory result associating COVID-19 status and PE development in a negative way is explained by two facts. First, anticoagulation treatment was protective against PE, especially in COVID-19 patients, highlighting the potential for anticoagulants to mitigate COVID-19-associated thrombotic complications [

14,

25]. Second, the high proportion of COVID-19 patients treated with prophylaxis with high success.

In addition, from Cox Proportional-Hazards model, COVID-19 status and prophylactic treatment emerge as the most influential factors on survival, with COVID-19 increasing mortality risk, and prophylactic treatment potentially offering protective benefits, higher than observed for anticoagulants.

Although our analysis of causes of death by treatment type and PE+COVID-19 status reveals that anticoagulants are associated with increased odds of cancer-related death or sepsis death in non-PE patients, it doesn’t evidence the protective role against thrombosis-related mortality [

17]. Studies report inconsistent evidence regarding its effectiveness in reducing thrombosis-related mortality, especially given the varying baseline risks of thrombosis across patient populations and phases of the pandemic. In particular, anticoagulant use in cancer patients with COVID-19 or other comorbidities, like sepsis, can increase bleeding risks, which may inadvertently elevate mortality rates in these groups due to complications unrelated to thrombosis prevention [

26,

27]. In contrast, corticosteroids were linked to increased cancer-related mortality, likely due to immunosuppression. This effect was particularly pronounced in PE patients. Corticosteroids are known to dampen immune responses, potentially increasing susceptibility to infections and exacerbating underlying malignancies, which aligns with findings linking corticosteroids to adverse outcomes in cancer patients under immunosuppressive therapies [

26].

4.2. Comparison with Previous Studies

These findings resonate with existing evidence that corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone, improve survival in critically ill COVID-19 patients, albeit with varying effects on secondary infections [

28,

29]. Additionally, the benefits of anticoagulants in preventing VTE in COVID-19 patients are well-documented, particularly for patients with elevated d-dimer levels [

9,

30]. Our study extends this knowledge by highlighting how these treatments interact with clinical markers, such as SIC scores, and by emphasizing the influence of demographic factors like age and sex on survival outcomes, as shown in previous studies [

31,

32].

4.2. Clinical Implications

The significant associations observed between COVID-19 status, PE, and anticoagulation treatment align with studies emphasizing the necessity for individualized therapeutic approaches, given the increased risk of PE in COVID-19 patients, timely anticoagulation therapy could mitigate some of the life-threatening complications associated with COVID-19-related thrombosis [

3,

9]. Additionally, our findings suggest that demographic factors, such as age and sex, may also play a role in modifying treatment efficacy, which could indicate that personalized treatment strategies based on these variables may further optimize outcomes [

31,

32].

Moreover, the analysis of SIC scores, which were conservatively estimated by considering a SOFA score of zero, highlighted a clear relationship between higher SIC scores and increased mortality. Patients with elevated SIC scores exhibited significantly worse survival outcomes, reinforcing the importance of closely monitoring coagulation markers like INR and platelet count to manage patient risk more effectively [

10,

33].

Anticoagulants and Mortality: Numerous studies have demonstrated that therapeutic anticoagulation can reduce the risk of thrombotic events and, in some cases, lower mortality rates among hospitalized COVID-19 patients, especially those with elevated d-dimer levels or on mechanical ventilation. For instance, the HEP-COVID trial found that therapeutic doses of anticoagulants significantly reduced thrombosis and had a lower mortality rate compared to prophylactic doses in high-risk patients [

34,

35,

36]. This aligns with our study’s findings, where anticoagulant use was associated with reduced deaths from thrombotic complications.

Corticosteroids and Mortality: Corticosteroids, widely used for their anti-inflammatory properties, have also shown varying effects on COVID-19 outcomes. According to the RECOVERY trial, corticosteroids significantly reduced mortality among critically ill COVID-19 patients by mitigating hyperinflammatory responses, although the benefit varied based on timing and dosage [

37,

38,

39]. In our study, corticosteroids were associated with deaths primarily due to secondary infections, which aligns with the known increased risk of sepsis associated with corticosteroid use due to immunosuppression [

40,

41,

42].

Thrombotic Complications and Sepsis: COVID-19 patients are at high risk for both thrombotic and septic complications due to the virus’s impact on the immune and coagulation systems. Literature supports that anticoagulation strategies can prevent these outcomes, though they must be balanced against bleeding risks, particularly in critically ill patients [

7,

43]. The ATTACC and ACTIV-4a trials reported mixed outcomes for severely ill patients receiving anticoagulation, highlighting the complexity of managing thrombotic and septic risks in this population [

9,

44].

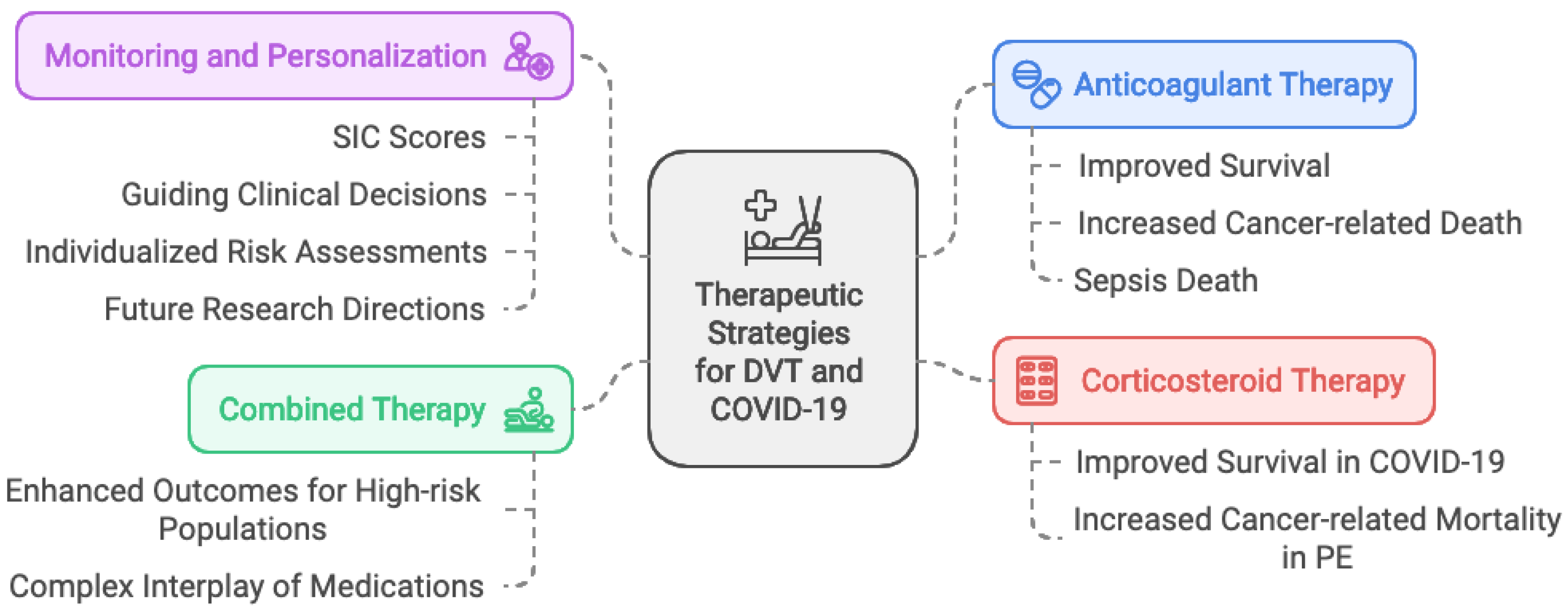

4.3. Limitations

This study’s retrospective design introduces potential biases, as treatment was not randomized. Additionally, conservative SIC score estimates and residual confounding factors may limit the generalizability of our findings, especially in smaller treatment subgroups. Future studies in larger, prospective cohorts are needed to validate these findings and explore how patient characteristics can further refine treatment strategies. See

Figure 4.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that anticoagulant and corticosteroid therapies were significantly associated with survival outcomes and the progression to PE in patients with DVT and COVID-19. This supports the notion that an integrated therapeutic approach for this specific subgroup of patients could enhance outcomes in high-risk populations. Monitoring coagulation markers like SIC scores proved valuable in predicting patient outcomes and guiding clinical decisions, highlighting the importance of personalized treatment planning.

Our findings reveal differentiated associations of these therapies with causes of mortality, with anticoagulants linked to an increased risk of cancer- or sepsis-related deaths in non-PE patients, while corticosteroids were associated with higher cancer-related mortality, particularly in PE patients. This complex interplay of medications and their effects on mortality rates underscore the need for individualized risk assessments for thrombosis and aligns with updated recommendations that stress a cautious approach to anticoagulation and immunosuppressive therapy in high-risk patients. The observed associations between therapy, SIC scores, and mortality suggest that tailoring treatment to each patient’s risk profile may optimize survival outcomes, especially in those facing complex thrombotic and infectious challenges. Future research should validate these findings in larger cohorts and explore the mechanisms by which tailored therapeutic strategies might further improve patient-specific outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Survfit curves with 95% confidence intervals for different PE - COVID-19 - Treatment combinations; Table S2: Data used for this study; File S3: R codes for survival models and analysis; File S4: R codes for Cox Proportional-Hazard Models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, R.A. and G.B-M..; software, R.A.; validation, G.B-M., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript..

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the CEC (Scientific Ethics Committee) of Hospital San Juan de Dios (protocol code 167, version 2, approved on December 9, 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived by the CEC of Hospital San Juan de Dios due to the fact we worked with anonymized data and the design of our study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Head Office of the Critical Patient Unit and the Imaging Unit for facilitating access to the database necessary for the realization of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kahn, S.R.; et al. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Thromb. Res. 2014, 134, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Iba, T.; Levy, J.H. COVID-19: A new challenge for thrombosis and hemostasis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1321–1322. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, S.R.; et al. The Post-thrombotic Syndrome: A Review of the Current Literature. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 17, 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S.; Qin, M.; Shen, B.; et al. Association of Cardiac Injury with Mortality in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, A.C.; et al. VTE prophylaxis with intermediate-dose anticoagulation in acutely ill medical patients. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 2572–2581. [Google Scholar]

- Klok, F.A.; Kruip, M.J.H.A.; van der Meer, N.J.M.; et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 2020, 191, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilaloglu, S.; Aphinyanaphongs, Y.; Jones, S.; et al. Thrombosis in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in a New York City Health System. JAMA 2020, 324, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linschoten, M.; Peters, S. COVID-19 and Cardiovascular Disease: A Global Perspective. Eur. Heart J. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The ATTACC, ACTIV-4a, and REMAP-CAP Investigators. Therapeutic Anticoagulation with Heparin in Noncritically Ill Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 790–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thachil, J.; Tang, N.; Gando, S.; et al. ISTH Interim Guidance on Recognition and Management of Coagulopathy in COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, A.C.; Levy, J.H.; Ageno, W.; et al. Scientific and Standardization Committee Communication: Clinical Guidance on the Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Jiajun, W.; Zhang, P.; Ma, X. The impact of COVID-19 on the prognosis of deep vein thrombosis following anticoagulation treatment: A two-year single-center retrospective cohort study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horby, P.; et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 384, 693–704. [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng, C.H.; et al. Impact of anticoagulation on mortality in COVID-19 patients with DVT. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 2435–2442. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, D.G. Practical Statistics for Medical Research; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood, B.R.; Sterne, J.A.C. Essential Medical Statistics, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Science Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F.E. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, W.E.; et al. Analysis of Survival Data. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2006, 15, 491–507. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum, D.G.; Klein, M. Survival Analysis: A Self-Learning Text, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Therneau, T.M.; Grambsch, P.M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A. An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Multiple significance tests: The Bonferroni method. BMJ 1995, 310, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z. Abnormal Coagulation Parameters are Associated with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Lei, X.; Zhao, H.; et al. Evaluation of COVID-19 Mortality and Adverse Outcomes in US Patients With or Without Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuker, A.; Tseng, E.K.; Nieuwlaat, R.; et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 Guidelines for Management of Venous Thromboembolism: Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized and Nonhospitalized Patients with COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby, P.; Lim, W.S.; et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Olivé, I.; Sintes, H.; Radua, J.; et al. COVID-19 and Pulmonary Embolism: A Review of the Literature. Thromb. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moores, L.K.; Tritschler, T.; Brosnahan, S.; et al. Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of VTE in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019. Chest 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Yu, Y.; Xu, J.; et al. Clinical Course and Outcomes of Critically Ill Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A Single-Centered, Retrospective, Observational Study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadkarni, G.N.; Lala, A.; Bagiella, E.; et al. Anticoagulation, Bleeding, Mortality, and Pathology in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llitjos, J.F.; Leclerc, M.; Chochois, C.; et al. High Incidence of Venous Thromboembolic Events in Anticoagulated Severe COVID-19 Patients. J. Thromb-Haemost. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, A.C. The HEP-COVID Trial. Heart Int. 2021, 15, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, A.C; Goldin, M.; Giannis, D.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Therapeutic-Dose Heparin vs Standard Prophylactic or Intermediate-Dose Heparins for Thromboprophylaxis in High-risk Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19: The HEP-COVID Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA International Medicine. 2021, 181, 1612–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrandis, R; Sierra, P.; Gomez-Luque, A.; et al. COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis. New evidence. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim (Engl Ed). 2022, 71, 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- González-Castro, A; Fito, E.C.; Fernández, A.; et al. Impact of corticosteroid therapy on the survival of critical COVID-19 patients admitted into an intensive care unit. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim (Engl Ed). 2022, 69, 110–121.

- The RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monedero, P; Gea, A.; Castro, P; et al. Early corticosteroids are associated with lower mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2021, 25, 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Loeches, I.; Torres, A. Corticosteroids for CAP, influenza and COVID-19: when, how and benefits or harm? European Respiratory Review. 2021, 30, 200346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, A. Recent Data about the Use of Corticosteroids in Sepsis—Review of Recent Literature. Biomedicines. 2024, 12, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Heng, G.; Zhang, J, R.; et al. Association between corticosteroid use and 28-day mortality in septic shock patients with gram-negative bacterial infection: a retrospective study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023, 10, 1276181.

- Afshar, Z.M.; Pirzaman, A.T.; Hosseinzadeh, R.; et al. Anticoagulant therapy in COVID-19: A narrative review. Clin Transl Sci. 2023, 16, 1510–1525. [Google Scholar]

- The REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4a, and ATTACC Investigators. Therapeutic Anticoagulation with Heparin in Critically Ill Patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).