1. Introduction

Soybean (

Glycine max (L.) is one of the main agricultural crops in the world and plays a key role in food, feed and biofuel production. Brazil is the largest producer, where soybean is grown on approximately 45.9 million hectares and had an output of over 147 million tons in the 2023/2024 growing season [

1]. Efforts have been concentrated to find more effective alternative inputs for soybean production, with minimal environmental impact [

2]. In this context, bioinputs seem promising. As part of the transition strategy to a more ecological agriculture, the large-scale commercial use of these products has been intensified in Brazil [

3]. Bioinputs are formulations of elements of biological origin that can include microorganisms, plant extracts, organic compounds, among others, which promote plant growth, increase resistance to pests and diseases and improve soil quality [

4].

For soybean, bioinputs have several environmental benefits that make crops safer and more resilient. These inputs can play an important role in reducing dependence on agrochemicals (fertilizers and pesticides), in conserving natural resources and in mitigating environmental impacts on agriculture [

5]. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct further research on the inclusion of bioinputs in agriculture, and clear public policies must be created to stimulate and promote their use in the tropics. Some of the main bioinputs are inoculants containing beneficial microorganisms, e.g., a number of genera of bacteria such as

Bradyrhizobium,

Bacillus,

Priestia,

Pseudomonas and

Azospirillum, known as plant growth promoters. These microorganisms have beneficial effects on plants and colonize the rhizosphere as well, which improves their performance under adverse environmental conditions[

6,

7].

The inoculation of soybean seeds with

Bradyrhizobium spp. strains promotes biological nitrogen fixation in the soil. By this technique, up to 94% of the plant nitrogen demand, equivalent to approximately 300 kg N ha

-1, can be met. These inputs reduce the dependence on synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, resulting in savings of approximately US

$3.2 billion [

8].

Inoculants that contain

Bacillus subtilis and

Priestia megaterium strains produce different organic acids capable of solubilizing phosphorus combined with calcium, aluminum and iron in the soil, and make P readily available to plants. These two strains were isolated in different agricultural areas in the country, where cereal cultivation prevails [

9]. Another phosphorus-solubilizing genus in the soil is

Pseudomonas, which is a quite common soil bacterium. The bacterium

Priestia aryabhattai, native to the Caatinga biome [

10], can improve plant resistance to abiotic stresses, e.g., drought, salinity and extreme temperatures [

11]. These advantages are particularly relevant in the context of adaptation to climate change, with its increasing challenges for plants. These microorganisms are capable of hydrating roots and influencing the plant physiology, enabling plants to respond better to water scarcity.

Azospirillum spp. are free-living soil bacteria that have the capacity to fix biological nitrogen symbiotically with plants. However, they are mainly known for other mechanisms, such as the production of phytohormones (e.g., indole-3-acetic acid - IAA) that influence plant growth and development, especially of the roots, thus optimizing the efficiency of water and nutrient use. These bacteria are recommended for inoculation of a wide range of species, particularly of the

Poaceae family, and are commonly used in maize cultivation [

12]. For legumes, e.g., bean and soybean, it is recommended to co-inoculate

Azospirillum spp. with

Bradyrhizobium sp. to improve crop performance, in an approach to meet the current demand for a sustainable and regenerative agriculture [

13]. In view of the benefits of inoculants, the use of this type of bioinput is on the rise in Brazil [

3]. With a view to enabling producers to optimize the use of this technology, the development of new technologies and the definition of recommendations for the main crops in the country are vitally important. In this context, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of co-inoculation of growth-promoting bacteria of the genera

Azospirillum spp.,

Pseudomonas spp.,

Priestia spp. and

Bacillus spp. combined with

Bradyrhizobium spp. on newly emerged soybean plantlets.

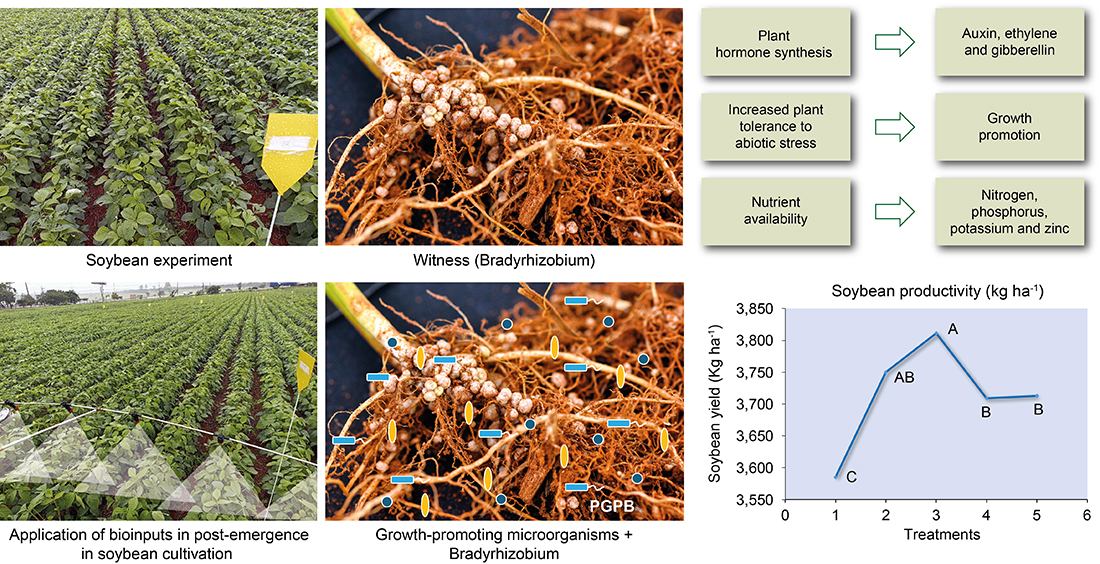

2. Results

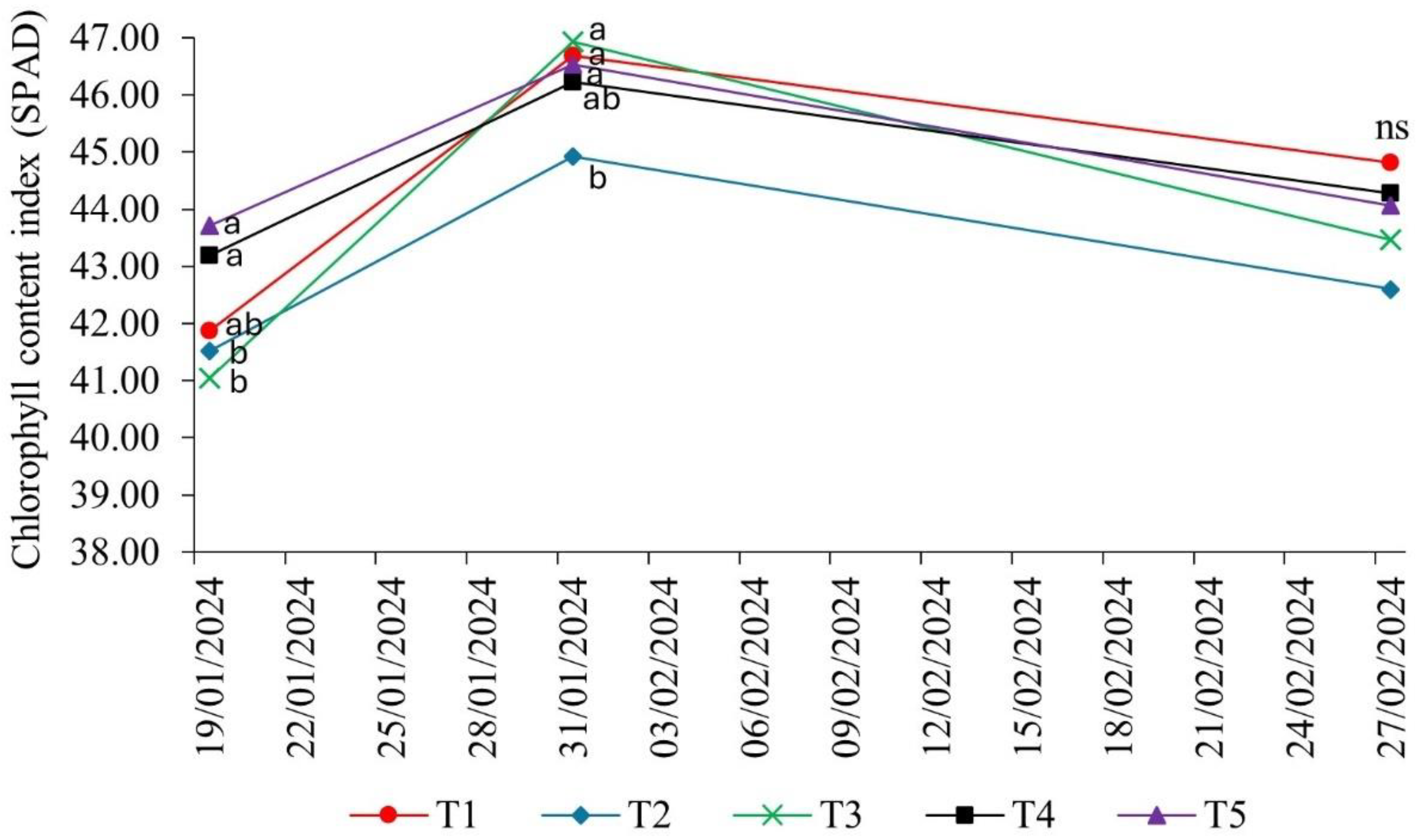

2.1. Chlorophyll Content Index (SPAD) in Response to Bioinputs

The chlorophyll content index (soil-plant analysis development - SPAD value) of soybean was influenced by the presence of

Bradyrhizobium elkanii associated with growth-promoting microorganisms. In the vegetative stages of the crop, the index differed significantly between the treatments, except in the reproductive stage R6 (full grain filling - 02/27/2024) (

Figure 1).

In the reproductive stage R3 (early pod development - 01/19/2024), chlorophyll contents were highest in treatment T4 (P. aryabhattai; B. haynesii; B. circulans) and T5 (P. megaterium - BRM 119; B. subtilis - BRM 2084), i.e., both included representatives of the genera Bacillus and Priestia.

In the phenological stage R4 (pod filling – 01/31/2024), the SPAD index was lowest in T2 (A. brasilense - CNPSo 2083; CNPSo 2084), while in the other treatments, no statistical differences were observed. These results indicated that the influence of complementary inoculation with growth-promoting bacteria on chlorophyll indices in soybean can vary, depending on the microorganisms associated in the different phenological stages of the crop.

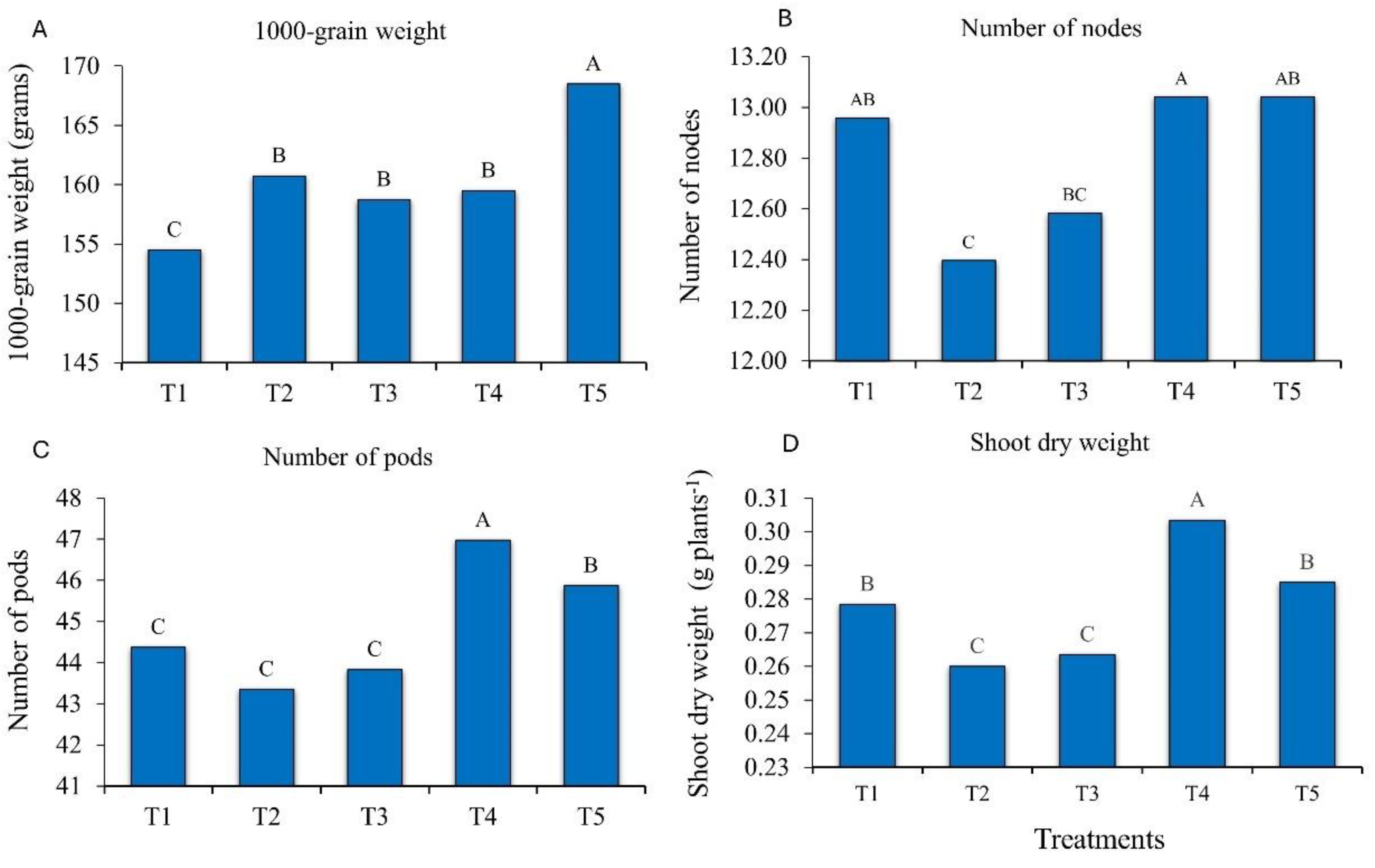

2.2. Development of Soybean Plants in Response to Bioinputs

The treatments with bioproducts containing

Bacillus and

Priestia increased the mean values of agronomic traits, namely of 1000-grain weight, number of nodes, number of pods and shoot dry weight (

Figure 2). These results reinforce the positive effect of

Bacillus and

Priestia application on soybean growth and agronomic performance. For the variable 1000-grain weight, inoculation with

P. megaterium and

B. subtilis (T5) resulted in a mean weight increase of 8.49%, compared to the control (

Figure 2A). For the variable plant height, no statistical differences were observed between the evaluated treatments. The plants were tallest (84.06 cm) in the treatment with

P. aryabhattai;

B. haynesii; and

B. circulans (T4), compared with the control (81.81 cm).

In the soybean plants inoculated with T4 and with

P. megaterium and

B. subtilis (T5), the variable number of nodes increased. However, this treatment did not differ from the control (check without complementary inoculation with growth-promoting microorganisms) (

Figure 2C).

The number of pods increased when the plants were inoculated with

P. aryabhattai;

B. haynesii and

B. circulans (T4), with an increase from 44 pods per plant in the control to 47, which reinforces the positive influence of these bacteria on plant development (

Figure 2D).

Shoot dry weight was significantly higher in plants inoculated with

P. aryabhattai;

B. haynesii and

B. circulans (T4). The pattern was the same as for number of pods, with an increase from 0.28 g plants

-1 in the control (T1), to 0.30 g plants

-1 in T4, i.e., an increase of 500 kg ha

-1 (

Figure 2E).

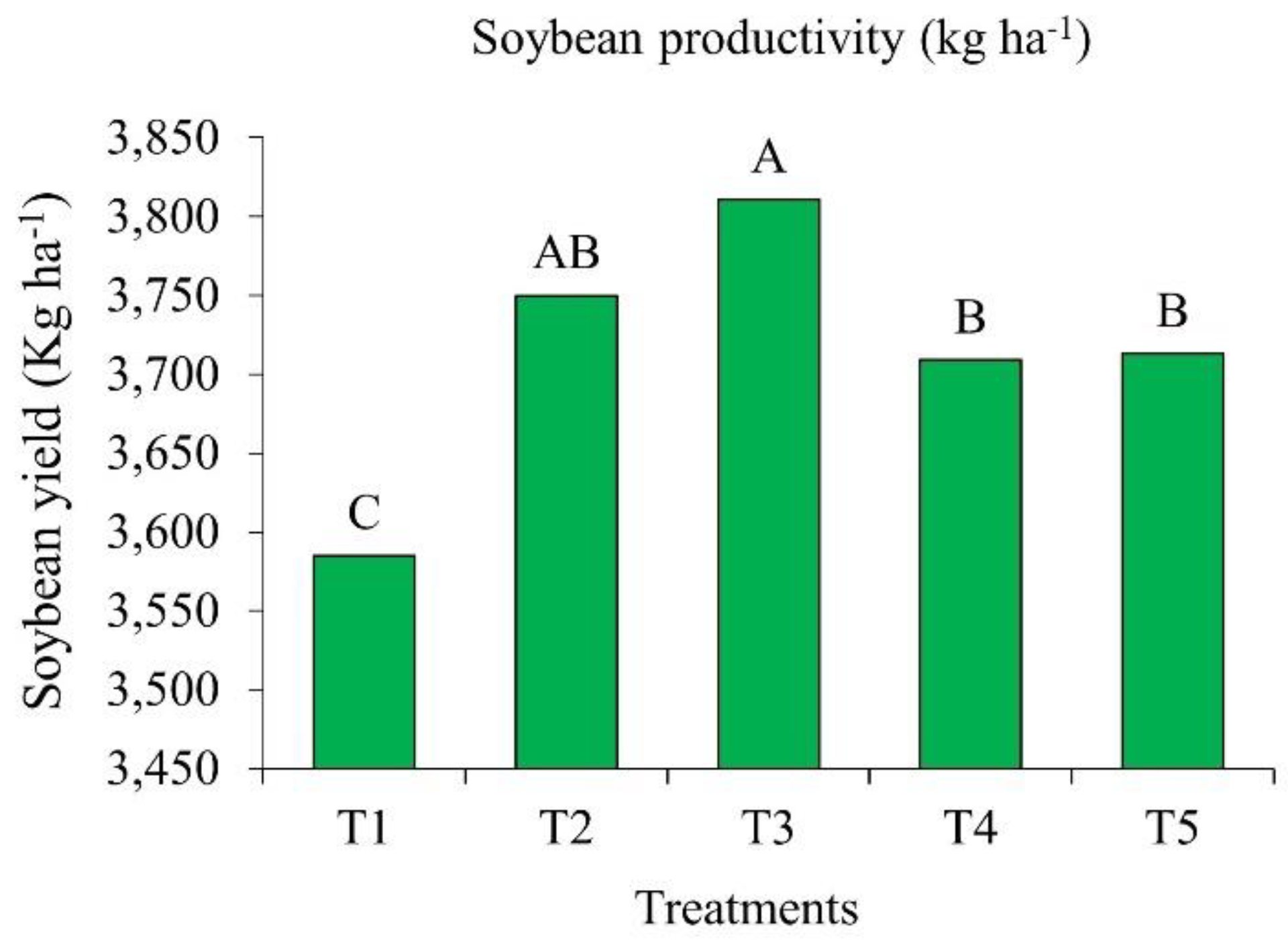

2.3. Soybean Yield in Response to Bioinputs

All products containing growth-promoting bacteria of the genera

Azospirillum, Pseudomonas,

Priestia and

Bacillus, when applied to emerged soybean, increased grain yield, compared to the control (

Figure 3). In T2 and T3, with

Azospirillum and

Priestia inoculation, grain yields were significantly higher than in the other treatments.

Treatment T2, inoculated after emergence with A. brasilense strains CNPSo 2083 and CNPSo 2084, produced 3,750 kg ha-1, which represents an increase of 165 kg ha-1 per hectare compared to the control. On the other hand, T3, treated with P. fluorescens strain CNPSo 2719 and A. brasilenses strains CNPSo 2083 and CNPSo 2084, yielded 3,811 kg ha-1, i.e., an increase of 226 kg ha-1 per hectare in relation to the control.

3. Discussion

3.1. Influence of Growth-Promoting Bacteria on the Chlorophyll Content Index (SPAD) in Soybean

Inoculation with bacteria that promote phosphorus uptake increases chlorophyll levels of inoculated plants [

14]. This is the case with bacteria of the genera

Bacillus and

Priestia, which are classified as solubilizers of inorganic phosphates[

15,

16]. They are capable of releasing phosphate adsorbed in the soil and making it available to plants. This reduces the need for future fertilization, prevents excessive phosphorus accumulation and minimizes economic and environmental impacts, such as pollution by eutrophication [

17].

Chlorophyll pigments are fundamental indicators to be considered in cultivation systems, since these molecules are responsible for photosynthesis, the process by which plants convert sunlight into chemical energy [

18]. Chlorophyll levels are generally positively related to the plant nitrogen content. Although phosphorus is not a component of the chlorophyll molecule, it provides energy for the active uptake of nitrogen (N), which is a constituent of the porphyrin ring of the molecule, as described by Taiz & Zeiger [

19].

Therefore, inoculation of soybean with

Bradyrhizobium elkanii along with complementary application of phosphorus solubilizers of the genera

Bacillus and

Priestia raises chlorophyll levels. In a study on soybean development, Costa et al. [

20] observed that chlorophyll, an indicator of plant adaptability and growth in different environments, responded positively to higher rates of a

B. subtilis-based product, in comparison with the control treatment, both in the early stage of development, at 15 DAS, and at 45 DAS, and for both tested cultivars.

Lima et al. [

21] evaluated the yield of maize inoculated with

B. subtilis, with and without nitrogen fertilization, and found higher chlorophyll levels in the treatments with than those without inoculation. Similarly, Costa et al. [

20] observed an increase in the SPAD chlorophyll index in soybean leaves in response to higher

B. subtilis rates.

3.2. Soybean Growth and Development after Application of Growth-Promoting Microorganisms

The use of beneficial microorganisms in cultivation systems contributes to sustainable agriculture, resulting in improved crop growth, development and grain yield, without damaging the environment. Inoculation with bacteria of the genera

P. megaterium and

B. subtilis can result in more robust and heavier grains, contributing to an increase in 1000-grain weight. Similar results were found by Lima & Busso [

22], who evaluated the use of

P. megaterium and

B. subtilis in the treatment of hybrid maize seeds in the second crop. They observed increases in 1000-grain weight in response to rising rates of these microorganisms.

Growth-promoting bacteria also have beneficial effects on plants through different mechanisms of action, whether direct (biological nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, phytohormone production) or indirect (siderophore and biofilm production) [

23]. These bacteria can produce phytohormones such as auxins, cytokinins and gibberellins, which stimulate cell division and stem elongation, favoring the formation of new nodes. This effect can be observed in response to inoculation with

P. aryabhattai;

B. haynesii;

B. circulans (T4) and

P. megaterium and

B. subtilis (T5), evaluated in this study.

In an evaluation of soybean seeds inoculated with growth-promoting microorganisms, Mattos [

24] observed that only

B. subtilis promoted an increase in the number of nodes per plant, from the control without inoculation, with 16.20 nodes, to a total of 17.70 productive nodes on inoculated plants.

In the evaluation of soybean growth and development in response to bioinputs, monitoring the number of pods is of utmost importance. These data can contribute to make the production management more efficient, allowing more accurate decisions and, consequently, better agronomic results. It is worth mentioning that although the number of pods per plant is an important variable, it can vary depending on a variety of factors, such as genetics, environment, biotic and abiotic factors and management practices.

The results indicated that inoculation with bacteria of the genera

P. aryabhattai;

B. haynesii and

B. circulans were the most efficient in increasing number of pods in soybean. Contrary results were reported by Silvestrine et al. [

25], who observed no significant effect on number of pods per soybean plant in response to phosphate fertilization and inoculation with

Bacillus sp. in the field.

Another important variable in crop development is shoot dry weight, which is an indicator of the plant dry weight and reflects the total amount of organic matter a plant produces. The increase in dry weight in plants treated with complementary inoculation with microorganisms (P. aryabhattai; B. haynesii; B. circulans) indicated a more robust growth and development than of the control plants, inoculated only with Bradyrhizobium elkanii at planting. In addition, the higher dry weight production can be reflected in a higher straw dry weight, which is important for soil cover and protection against erosion.

Priestia aryabhattai;

B. haynesii and

B. circulans seem to be promising for use in agriculture, due to the vast range of benefits these bacteria can confer to plants, ranging from increased resistance to abiotic stresses, such as drought, to nutrient availability [

26]. Park et al. [

27] found that a strain of

P. aryabhattai increased soybean and rice growth significantly. By scanning microscopy, they also observed that the strain colonized the roots successfully within two days after inoculation, which resulted in greater shoot length than in the control treatment.

3.3. Effect of Supplemental Application of Growth-Promoting Bacteria on Soybean Grain Yield

Complementary inoculation is an advantageous alternative for producers, as it increases crop yield and also contributes to the sustainability of the system. This technique improves the efficiency of nitrogen fixation by plants and reduces the need for synthetic nitrogen fertilizers. In this way, not only input costs can be reduced, but the negative impacts on the environment associated with an excessive use of chemical fertilizers, such as soil and water pollution, can also be minimized.

The results of the combined use of

B. elkanii and

A. brasilense in soybean are promising Benintende et al. [

28], in that mean yield increases of 7.7% have been reported [

13]. In two growing seasons and at four locations (Londrina and Ponta Grossa in Paraná, where populations of

Bradyrhizobium spp. were already established, and Rio Verde and Cachoeira Dourada in Goiás, without previous populations of these bacteria), the same authors observed higher yields at all locations in response to this combination, compared to

Bradyrhizobium spp. inoculation only and equal to fertilization with 200 kg N ha

-1 in the treatment without inoculants.

4. Materials and Methods

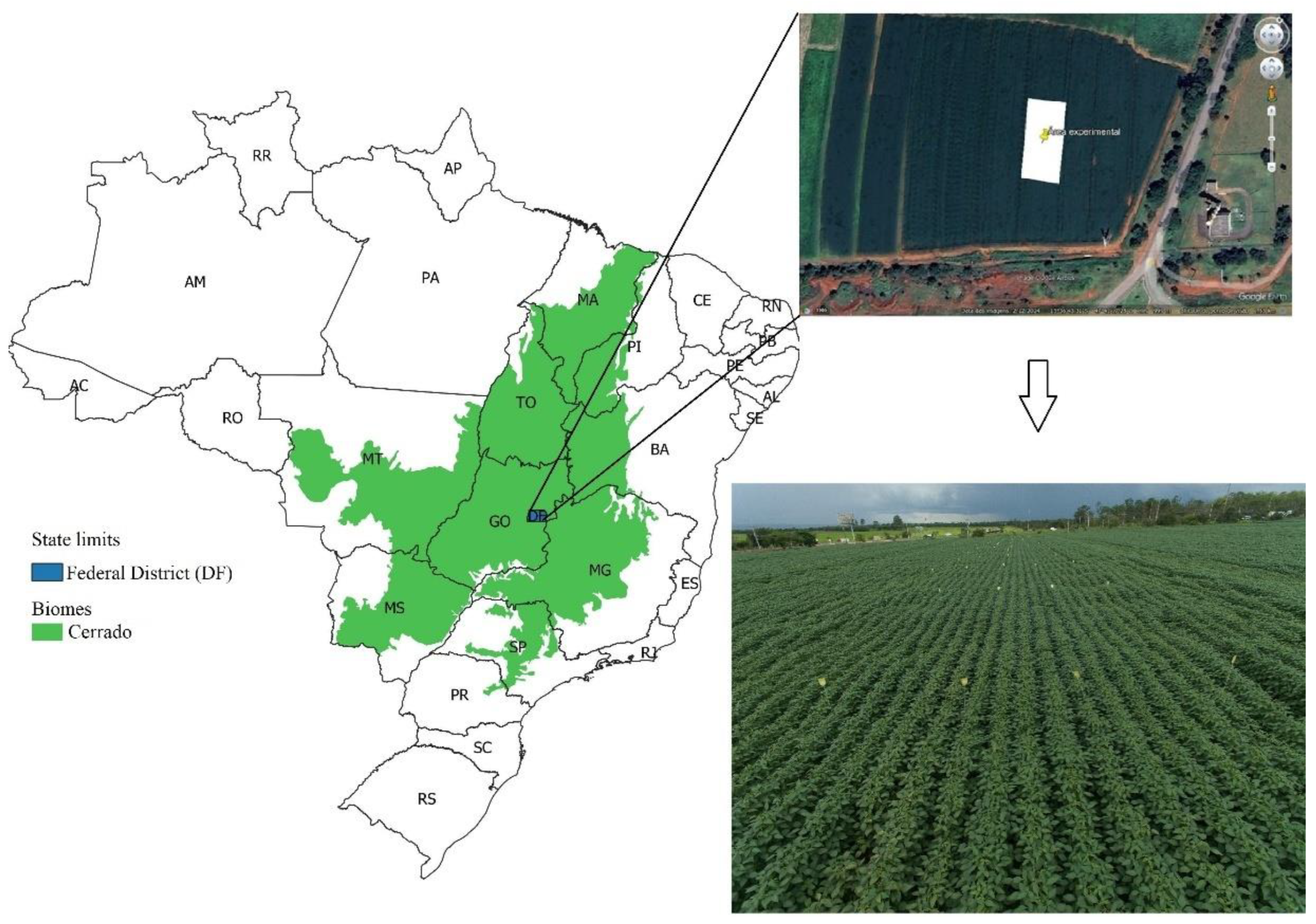

4.1. Experimental Area

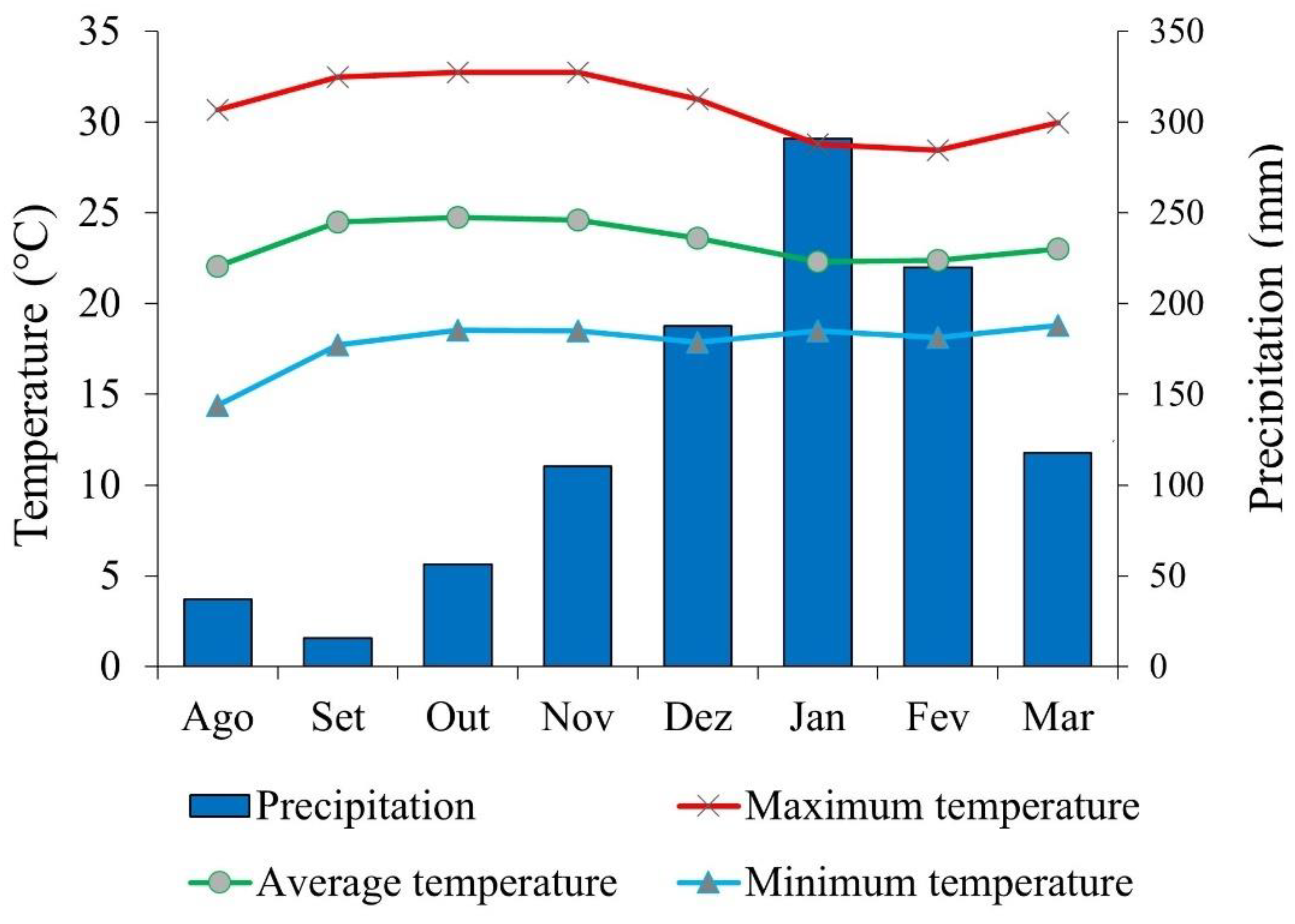

The study was carried out in the experimental area of Embrapa Cerrados, in Planaltina, Distrito Federal (15°36’38.82” S, 47°42’13.63” W; 980 m asl.) Soybean was planted on December 1, 2023 and harvested on March 22, 2024 (

Figure 1).

Figure 4.

Location of the experimental area.

Figure 4.

Location of the experimental area.

In 2023, cumulative rainfall at the meteorological station near the experimental area was 791 mm. During the soybean cycle (December 2023 to March 22, 2024), cumulative rainfall was 773 mm (

Figure 2). The maximum, mean and minimum temperatures in the same period were 30.88; 23.39 and 17.80 ºC, respectively (

Figure 5). The regional climate was classified as Aw (Köppen’s classification). The soil was identified as a Red Latosol with a clayey texture. Prior to the installation of the experiment, soil chemical and physical properties (0-20 and 20-40 cm layers) were determined (

Table 1).

4.2. Experimental Design

The experiment was arranged in a randomized block design, with four replications. The five treatments consisted of formulations of commercial products with different bacteria, namely: T1 - Control (without inoculation), T2 - Azospirillum brasilense strains CNPSo 2083 and CNPSo 2084, T3 - Pseudomonas fluorescens strain CNPSo 2719; Azospirillum brasilense strains CNPSo 2083 and CNPSo 2084, T4 - Priestia aryabhattai strain CBMAI 1120; Bacillus haynesii strain CCT 7926; Bacillus circulans strain CCT 0026 and T5 - Priestia megaterium strain BRM 119; Bacillus subtilis strain BRM 2084. The experimental area of 600 m2 (60 x 10 m) was divided into 20 plots.

4.3. Management and Application Time

Soybean cultivar BRS 7080 IPRO was used. In all treatments, the seeds were inoculated with Bradyrhizobium elkanii, strains SEMIA 5019 and SEMIA 587 (200 ml of the commercial product for 100 kg of seeds), immediately before sowing, by means of an electric concrete mixer.

The products were applied to soybean plants in stage V5/V6, with a CO

2 pressurized backpack sprayer at a constant boom sprayer pressure of 3.0 kgf cm

-2. The spraying was done with a five-nozzle boom that covered all five rows of a plot, applied at a height of 0.50 m above the target. The rates of each commercial product were defined according to the manufacturers' recommendations for soybean. Although the products met the expiration date, the bacterial colonies were counted as described by Bettiol et al. [

29].

Before planting, fertilization (150 kg ha-1 potassium chloride (K2O) and 200 kg ha-1 monoammonium phosphate (MAP)) was broadcast in the planting row.

The phytosanitary management consisted of specific products applied during the crop cycle, according to the technical recommendations for soybean. Herbicide was applied once after emergence, and insecticides and fungicides twice. The following commercial products were applied: imazethapyr (100 g a.i./L) at a rate of 0.5 L ha-1; glyphosate (480 g a.i./L) at 3 L ha-1; and clethodim (240 g a.i./L) at a rate of 0.3 L ha-1. The inseticides, thiamethoxam + lambda-cyhalothrin (141 + 106 g a.i./L) were applied at a rate of 0.3 L ha-1; pyriproxyfen (100 g a.i./L) at 0.25 L ha-1; chlorpyrifos (480 g a.i./L) at 1 L ha-1; and acetamiprid (150 g a.i/Kg) at 0.15 Kg ha-1; and the fungicides trifloxystrobin + tebuconazole (100 + 200 g a.i./L) at 0.75 L ha-1 and bixafem + prothioconazole + trifloxystrobin (125 + 175 + 150 g a.i./L) at 0.5 L ha-1.

4.4. Chlorophyll Index Determination (SPAD)

The chlorophyll index was determined in the phenological stages R3, R4 and R6 with a portable electronic chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502 Plus, Konica Minolta). This device determines the relative amount of chlorophyll by measuring absorbance at two wavelengths (650 nm - red light and 940 nm - infrared light).

The third trifoliate of the upper third of the plant was used for the measurements. Six measurements per trifoliate were made to compute the mean values of each plant. Per treatment and replication, five randomly selected uniform plants were evaluated.

4.5. Determination of Yield and Grain Yield Components

Grain yield was evaluated by manually harvesting the plants growing in 2m of the three central rows of each plot. In addition to yield, the following yield components were measured: plant height, number of nodes, number of pods, shoot dry weight and 1000-grain weight. Grain yield was estimated after mechanical threshing of the pods and weighing the grain of the areas considered for evolution of each plot, assuming a moisture content of 13%.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

The data were subjected to analysis of variance and, in case of significance of the treatments, the means were compared by Duncan’s test (p<0.05), using the statistical package R (R Development Core Team, 2014).

5. Conclusions

All products containing growth-promoting bacteria of the genera Azospirillum, Pseudomonas, Priestia, and Bacillus when applied to emerged soybean promoted higher grain yield compared to the control. This demonstrates the potential of these bacteria to improve crop yields. Among the evaluated commercial formulations, those containing Azospirillum brasilense induced the highest gains in grain yield. In terms of 1,000-grain weight, number of pods, and shoot dry matter, the bacterial species P. aryabhattai, B. haynesii, B. circulans, P. megaterium, and B. subtilis achieved the best results. However, plant height was not affected by the evaluated bioproducts, indicating that the beneficial effects were concentrated on characteristics directly related to grain yield. These results reinforce the potential use of these growth-promoting bacteria as an effective strategy by which soybean yield can be increased, without negatively affecting other agronomic aspects of the crop.

Author Contributions

Data acquisition, J.M.P.B; H.R.H; Conceptualization, R.L.M; methodology, R.L.M; G.C.S; S.R.M.A; F.B.R.J; writing—original draft preparation, G.C.S.; writing—review and editing, R.L.M; G.C.S; S.R.M.A; F.B.R.J; A.M.C; supervision, R.L.M; funding acquisition, R.M.L and A.M.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Distrito Federal (FAP-DF), grant number 00193-00002627/2022-62.

Data Availability Statement

not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Núbia Maria Corrêa for her help with the application of the bioproducts in the experimental area, and Ironei Rodrigues de Sousa, for his help in conducting the experiment and data acquisition. I would also like to thank the company BIOTROP, for the partnership.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Conab - Boletim da Safra de Grãos. Available online: http://www.conab.gov.br/info-agro/safras/graos/boletim-da-safra-de-graos (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Rocha, T.M.; Marcelino, P.R.F.; Da Costa, R.A.M.; Rubio-Ribeaux, D.; Barbosa, F.G.; da Silva, S.S. Agricultural Bioinputs Obtained by Solid-State Fermentation: From Production in Biorefineries to Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.C. Bioinsumos na cultura da soja; Embrapa: Brasília, DF, 2022; ISBN 978-65-87380-96-4. [Google Scholar]

- BRASIL. Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento (MAPA). Decreto nº 10.375, de 26 de maio de 2020. Institui o Programa Nacional de Bioinsumos e o Conselho Estratégico do Programa Nacional de Bioinsumos. Diário Oficial da União. 27 de maio de 2020, p. 105-106.

- Vidal, M.C.; Saldanha, R.; Veríssimo, M.A.A. Bioinsumos: o programa nacional e a sua relação com a produção sustentável. In: Sanidade vegetal: uma estratégia global para eliminar a fome, reduzir a pobreza, proteger o meio ambiente e estimular o desenvolvimento econômico sustentável. 1.ed, CIDASC: Florianópolis, Brasil, 2020, p.382-409.

- Naylor, D.; Coleman-Derr, D. Drought Stress and Root-Associated Bacterial Communities. Frontiers in plant science 2018, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalal, A.; Oliveira, C.E. da S.; Bastos, A. de C.; Fernandes, G.C.; de Lima, B.H.; Furlani Junior, E.; de Carvalho, P.H.G.; Galindo, F.S.; Gato, I.M.B.; Teixeira Filho, M.C.M. Nanozinc and Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria Improve Biochemical and Metabolic Attributes of Maize in Tropical Cerrado. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hungria, M.; Franchini, J.C.; Campo, R.J.; Graham, P.H. The importance of nitrogen fixation to soybean cropping in South Amer-ica. Nitrogen Fixation in Agriculture, Forestry, Ecology, and the Environment 2005, 4, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Abreu, C.S. de; Figueiredo, J.E.F.; Oliveira-Paiva, C.A.; Santos, V.L. dos; Gomes, E.A.; Ribeiro, V.P.; Barros, B. de A.; Lana, U.G. de P.; Marriel, I.E. Maize Endophytic Bacteria as Mineral Phosphate Solubilizers. Genet Mol Res 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavamura, V.N.; Santos, S.N.; Silva, J.L. da; Parma, M.M.; Avila, L.A.; Visconti, A.; Zucchi, T.D.; Taketani, R.G.; Andreote, F.D.; Melo, I.S. de Screening of Brazilian Cacti Rhizobacteria for Plant Growth Promotion under Drought. Microbiol Res 2013, 168, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, D.; Raikhy, G.; Kumar, D. Chemical Elicitors of Systemic Acquired Resistance—Salicylic Acid and Its Functional Ana-logs. Current Plant Biology 2019, 17, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadore, R.; Netto, A.P.C.; Reis, E.F.; Ragagnin, V.A.; Freitas, D.S.; Lima, T.P.; Rossato, M.; D’Abadia, A.C.A. Híbridos de milho inoculados com Azospirillum brasilense sob diferentes doses de nitrogênio. Revista Brasileira de Milho e Sorgo 2016, 15, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Nogueira, M.A.; Araujo, R.S. Co-Inoculation of Soybeans and Common Beans with Rhizobia and Azospirilla: Strat-egies to Improve Sustainability. Biol Fertil Soils 2013, 49, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi-Zecchin, V.J.; Mógor, Á.F.; Ruaro, L.; Röder, C. Crescimento de mudas de tomateiro (Solanum lycopersicum) estimu-lado pela bactéria Bacillus amyloliquefaciens subsp. plantarum FZB42 em cultura orgânica. Revista de Ciências Agrárias 2015, 38, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dahmani, M.A.; Desrut, A.; Moumen, B.; Verdon, J.; Mermouri, L.; Kacem, M.; Coutos-Thévenot, P.; Kaid-Harche, M.; Bergès, T.; Vriet, C. Unearthing the Plant Growth-Promoting Traits of Bacillus Megaterium RmBm31, an Endophytic Bacterium Isolated From Root Nodules of Retama Monosperma. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, S. da C.; Nakasone, A.K.; do Nascimento, S.M.C.; de Oliveira, D.A.; Siqueira, A.S.; Cunha, E.F.M.; de Castro, G.L.S.; de Souza, C.R.B. Isolation and Characterization of Cassava Root Endophytic Bacteria with the Ability to Promote Plant Growth and Control the in Vitro and in Vivo Growth of Phytopythium Sp. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2021, 116, 101709. [Google Scholar]

- Pavinato, P.S.; Rocha, G.C.; Cherubin, M.R. Acúmulo de fosforo no solo em áreas Agrícolas no Brasil: Diagnostico Atual e Potencialidades Futuras. NPCT (Nutrição De Planta Ciências E Tecnologia), Comunicado Técnico Nº 9, Piracicaba, SP- março, 2021.

- Taiz L, Zeiger E, Moller IM, Murphy A. Fisiologia e desenvolvimento vegetal. 6.ed. Artmed, Porto Alegre, 2017, p.1-888.

- Taiz, L.; Zeiger, E.; Oliveira, P.L. Fisiologia Vegetal, Edição: Paulo Luiz de Oliveira; 5.ed. Artmed, Porto Alegre, 2013, p. 1-918.

- Costa, L.C.; Tavanti, R.F.R.; Tavanti, T.R.; Pereira, C.S. Desenvolvimento de cultivares de soja após inoculação de estirpes de Bacillus subtilis. Nativa 2019, 7, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.; Nunes, L.A.P.L.; Figueiredo, M.V.B.; Araújo, F.F.; Lima, L.M.; Araújo, A.S.F. Bacillus subtilis e adubação nitrogenada na produtividade do milho. Agraria 2011, 6, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.P.A. de; Buso, W.H.D. Uso de biomaphos no tratamento de sementes de hibridos de milho culti-vado na safrinha. Revista Mirante 2022, 15, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. , Singh, V.; Pal, K. Importance of microorganisms in agriculture. In: Climate and Environmental changes: Impact, Challenges and Solutions, 1, 93-117, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mattos, M. Promoção do crescimento de soja a partir da inoculação de sementes com microrganismos não noduladores. Trabalho de conclusão de curso (graduação), Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul, Cerro Largo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil, 2017. https://rd.uffs.edu.br/bitstream/prefix/1877/1/MATTOS.pdf (Acesso 30 de Novembro de 2024).

- Silvestrini, G.R.; da Rosa, E.J.; Corrêa, H.C.; Dal Magro, T.; Silvestre, W.P.; Pauletti, G.F.; Conte, E.D. Potential Use of Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria in Soybean Culture. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.L.; Ferreira, J.S.; Brandão, M.H.; Moreira, A.C.S.; Cunha, W.V. da Efeito da aplicação de Bacillus aryabhattai no cresci-mento inicial do feijoeiro sob diferentes capacidades de campo. Revista do Comeia 2020, 2, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.-G.; Mun, B.-G.; Kang, S.-M.; Hussain, A.; Shahzad, R.; Seo, C.-W.; Kim, A.-Y.; Lee, S.-U.; Oh, K.Y.; Lee, D.Y.; et al. Bacillus Aryabhattai SRB02 Tolerates Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress and Promotes the Growth of Soybean by Modulating the Produc-tion of Phytohormones. PLoS One 2017, 12, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Benintende, S.; Uhrich, W.; Herrera, M.; Gangge, F.; Sterren, M.; Benintende, M. Comparación entre coinoculación con Brady-rhizobium japonicum y Azospirillum brasilense e inoculación simple con Bradyrhizobium japonicum en la nodulación, creci-miento y acumulación de N en el cultivo de soja. AgriScientia 2010, 27, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettiol W, Morandi MAB, Pinto ZV, Lucon CMM (2022) Controle de qualidade e conformidade de produtos e fermentados à base de Bacillus spp.: proposta metodológica. Embrapa (Comunicado Técnico 59), Jaguariúna, p 15. https://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digit al/bitstream/item/239978/1/Bettiol-Controle-qualidade-2022-2. pdf. Accessed 2 Nov 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).