1. Introduction

Healthy aging is largely influenced by a nutritious diet and moderate exercise. When combined with smoking cessation and moderate alcohol consumption, these habits provide substantial physical and emotional benefits to patients. Individual longevity depends on approximately 30% genetics, with the remaining 70% being influenced by personal choices [

1,

2]. Oral health significantly impacts the quality of life, affecting one’s ability to eat, speak, and socialize comfortably [

3]. Regular dental checkups, proper oral hygiene, and lifestyle adjustments can help prevent or manage oral health issues in the elderly population.

Oral health is closely associated to systemic health [

4]. Oral diseases can increase the levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the blood, leading to chronic inflammation, shorter telomeres, and decreased mitochondrial function [

5,

6,

7]. This association is particularly significant in high-risk populations, as it affects major organs, such as the kidneys, liver, heart, and brain, and contributes to aging and cancer [

8,

9,

10].

Bone marrow defects of the jaw (BMDJ) can develop after dental procedures, connecting the immune and bone systems through cytokines such as RANTES/CCL5, which are often overexpressed in fatty degenerative osteonecrosis of the jawbone (FDOJ). Apical periodontitis, a prevalent inflammatory condition in older adults, can lead to tooth loss and systemic issues such as cardiovascular diseases [

11]. Moreover, undiagnosed asymptomatic conditions pose a risk to systemic health [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Dental implants are essential for treating oral diseases and restoring oral function, especially as human life expectancy increases. Implant success depends on osseointegration, during which the implant surface bonds directly with the surrounding bone tissue [

16]. Advances in implant surface technology and biomaterials have improved osseointegration outcomes, leading to faster healing and a reduced risk of implant failure [

17].

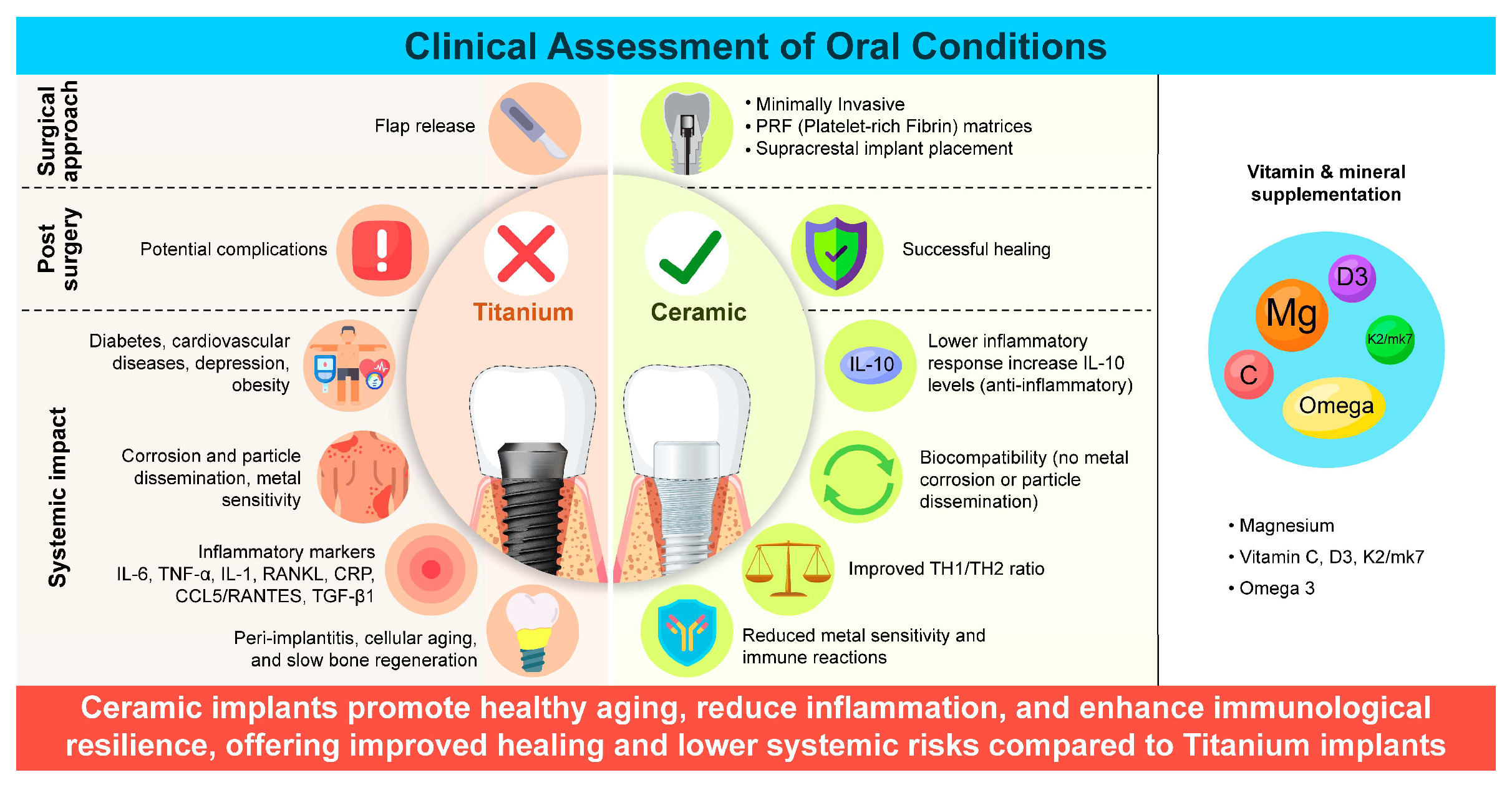

However, complications such as peri-implantitis—a destructive inflammatory condition affecting the tissues around dental implants—can arise because of a weaker soft tissue–implant interface [

18,

19,

20]. Positive outcomes have been observed with ceramic dental implants, where a focus on oral hygiene and vitamin supplementation reduced pro-inflammatory marker levels and improved patient health [

5,

21,

22] (

Figure 1).

This study underscores the importance of oral health in systemic conditions and highlights how informed decision-making can enhance the quality of life, prevent aging-related issues, and reduce the healthcare burden.

Figure 1.

Clinical assessment of oral conditions and systemic factors, such as immune response and inflammation, influencing the success of titanium and ceramic dental implants.

Figure 1.

Clinical assessment of oral conditions and systemic factors, such as immune response and inflammation, influencing the success of titanium and ceramic dental implants.

2. Detailed Case Description

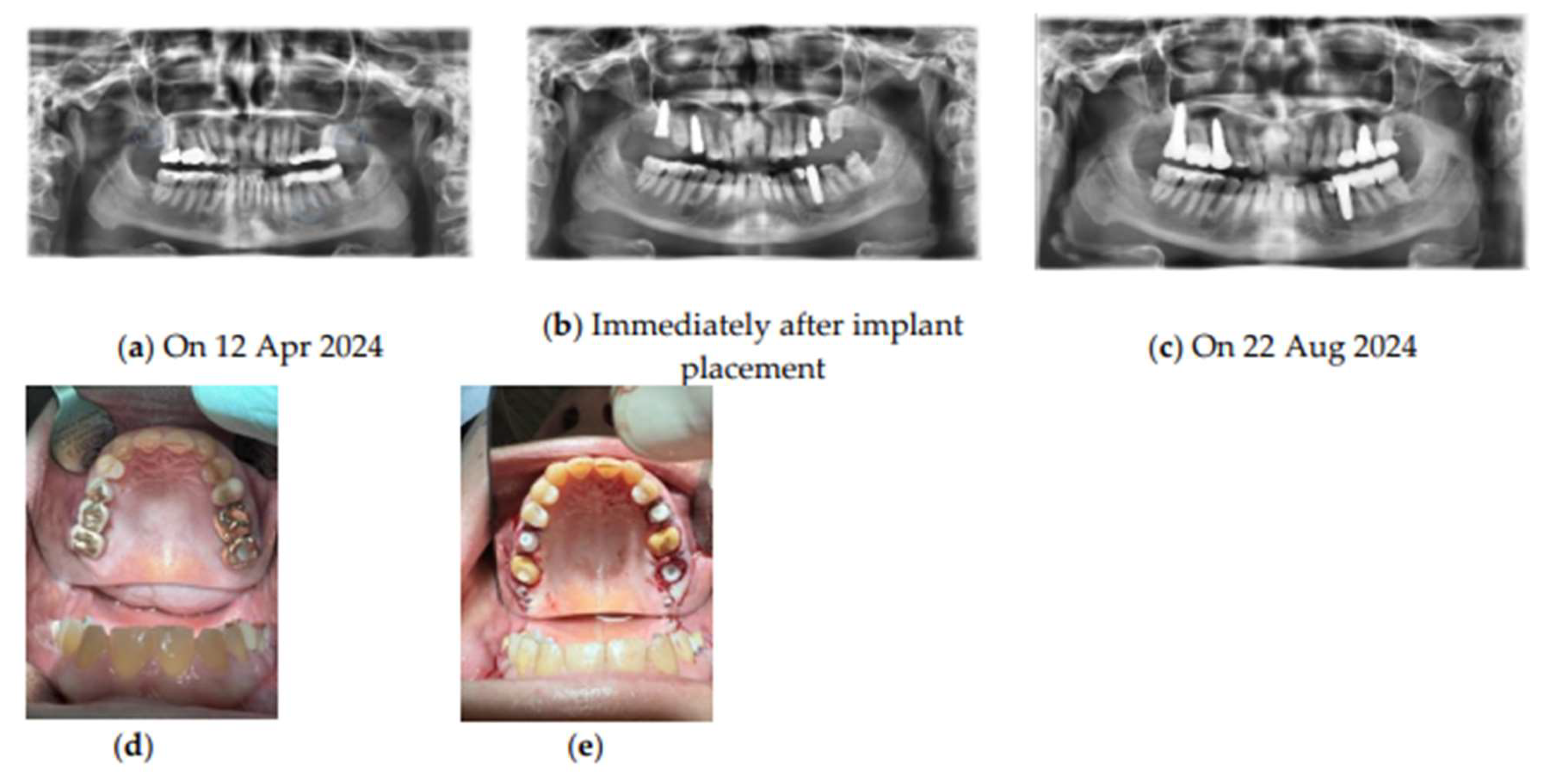

Here, we report the case of a 53-year-old female who underwent immediate or late ceramic implant placement in April 2023 and was monitored for four months using radiographs and medical records. All implants were placed supracrestally in the maxilla and mandible. The patient required implant placement for several reasons, including metal sensitivity, tooth loss due to decay, periapical lesions in the root canal-treated teeth, misfit of crowns/bridges or prostheses, and periodontal destruction. Informed consent for treatment the use of anonymized data for publication were obtained from the patient. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Declaration of Helsinki.

Blood analyses and radiography were performed before and after the final prosthetic restoration (

Figure 2). The patient required implant placement for a single missing tooth, for those with corroded amalgam, gold, or metal crowns/bridges, for poorly fitted restorations, cracks, secondary caries, or periapical cysts in root canal-treated teeth.

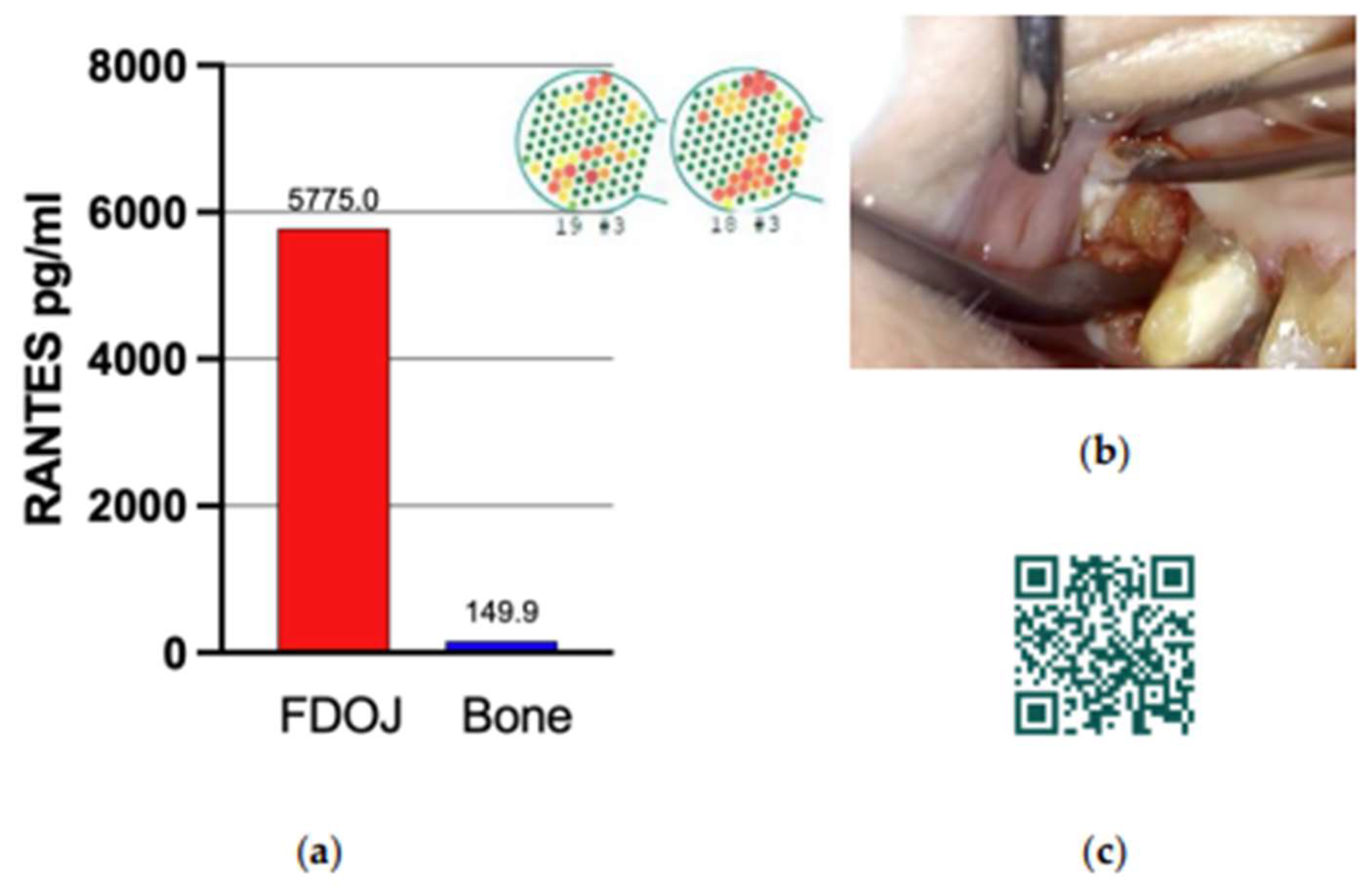

The presence of BMDJ associated with osteoimmune dysregulation was observed preoperatively using panoramic radiography and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT)/digital volume tomography (DVT) and confirmed with trans-alveolar ultrasonic (CaviTAU) examination to address the diagnostic limitations of conventional methods. Postoperatively, the local expression levels of C–C motif chemokine 5 (CCL5)—also known as regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted (RANTES)—were determined using samples excised from the patient’s jawbone [

6,

22,

23] (

Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Timeline and overview of the treatment protocol with SDS ceramic implant placement. Radiographic images taken (a) Before implant placement showing FDOJ regions indicated by blue circles at tooth positions 18–19, 35, and 28–29, (b) Immediately after implant placement, and (c) Months after implant placement. (d-e) Teeth condition during initial observation (d), Immediately after implant placement (e). Abbreviations: SDS, Swiss Dental Solutions; FDOJ, fatty degenerative osteonecrosis of the jawbone.

Figure 2.

Timeline and overview of the treatment protocol with SDS ceramic implant placement. Radiographic images taken (a) Before implant placement showing FDOJ regions indicated by blue circles at tooth positions 18–19, 35, and 28–29, (b) Immediately after implant placement, and (c) Months after implant placement. (d-e) Teeth condition during initial observation (d), Immediately after implant placement (e). Abbreviations: SDS, Swiss Dental Solutions; FDOJ, fatty degenerative osteonecrosis of the jawbone.

Figure 3.

RANTES/CCL5 expression in FDOJ. (a) FDOJ regions at tooth positions 18–19, shown in CaviTAU preoperative imaging. Red and yellow areas indicate low-density bone, whereas green areas represent healthy bone. The blue bar represents normal RANTES expression levels, and the red bar indicates overexpression values. (b) Clinical view after surgical assessment, showing fatty bone characterized by yellow coloration and soft consistency. (c) QR code linking to the surgical protocol for FDOJ assessment. Abbreviations: FDOJ, fatty degenerative osteonecrosis of the jawbone.

Figure 3.

RANTES/CCL5 expression in FDOJ. (a) FDOJ regions at tooth positions 18–19, shown in CaviTAU preoperative imaging. Red and yellow areas indicate low-density bone, whereas green areas represent healthy bone. The blue bar represents normal RANTES expression levels, and the red bar indicates overexpression values. (b) Clinical view after surgical assessment, showing fatty bone characterized by yellow coloration and soft consistency. (c) QR code linking to the surgical protocol for FDOJ assessment. Abbreviations: FDOJ, fatty degenerative osteonecrosis of the jawbone.

2.1. Surgical Procedure

Following clinical examination, CBCT was performed to assess the underlying bone and complete the diagnosis. Mineral and vitamin intake was prescribed for 4 weeks, both pre- and post-operatively (

Table 1). Daily doses of magnesium, vitamins C and D3, K2/mk7, and omega 3 were administered. We focused on the plasma concentration of vitamin D and its ratio to that of vitamin K2/mk7 (vitamin D 10,000 IU to 100 lg K2/mk7). Surgery was performed when vitamin D levels were between 70–100 ng/mL and LDL-cholesterol was ≤120 mg/dL to ensure appropriate systemic conditions for bone healing after surgery [

24]. The infusion protocol on the day of operation comprised 2.4 g co-amoxicillin in 50–100 mL NaCl. In the first 72 h post operation, the patient received daily infusions of 7,5 g vitamin C (118 g ascorbic acid, Pascoe), procaine (2 mL, 2% in 500 mL of Ringer B. Braun solution), zinc sulfate (23%, 43 mg in 100 mL NaCl; Sigma-Aldrich), magnesium sulfate (20%, 8 mmol; Bichsel), sodium bicarbonate (8.4%; Sintetica, Mendrisio), and vitamin B12 (1 mL/mg; Sintetica) in accordance with the Swiss Biohealth Concept [

25] and previous studies [

26,

27].

Pain was controlled with 600 mg ibuprofen, if needed. The implants were placed using a minimally invasive technique without vertically releasing the incisions under local anesthesia (articaine 40 mg/mL with epinephrine 10 mg/mL; Sanofi, Vernier, Switzerland). All implants were placed by the same surgeon, and rigorous inspection and curettage of the surgical sites were performed. Advanced platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) produced by low-speed centrifugation (Mectron Deutschland Vertriebs GmbH, Cologne, Germany) was placed at the surgical site, and over and around the implant [

28]. Augmentation of the alveolar ridge was based on the defect size. A non-resorbable monofilament suture (Atramat 4-0, Mednaht GmbH, Bochum, Germany) was used to stabilize the PRF matrices and reposition the flaps.

Table 1.

Pre- and post-operative mineral and vitamin supplementation.

Table 1.

Pre- and post-operative mineral and vitamin supplementation.

| Nutrient |

Pro Sachet |

% NRV* |

| Vitamin C |

450 mg |

563 |

| Vitamin D3 |

25 µg (1000 I.E.)#

|

500 |

| Vitamin K2/mk7 |

12 µg |

16 |

| Magnesium |

250 mg |

67 |

| Omega-3-fatty acids |

250 mg |

** |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester |

140 mg |

** |

| Docosahexaenoic acid ethyl ester |

60 mg |

** |

| Others |

calcium ascorbate, cholecalciferol, menaquinone-7, gelatin, microcrystalline cellulose, ethyl cellulose, fruit aroma |

** |

2.2. FDOJ Interventions:

FDOJ surgery involved making incisions in the gingiva and bone to expose the affected area (

Figure 2). The dead tissue, debris, and diseased bone were surgically removed. Local anesthesia was prolonged by applying a procaine-soaked compress to the treated area for 20 min, followed by thorough disinfection with ozone [

29]. The bone defects were repaired using PRF, and the wound was closed with absorbable sutures. After wound closure, liquid i-PRF was injected for additional enrichment of endogenous growth factors for regeneration (

Figure 3).

2.3. Analysis of IgG Glycans and Biological Age

IgG

N-glycan profiles were assessed before and four months after treatment (GlycanAge, England) following the method described by Krištić et al. [

30]. IgG was isolated from 100 μL of plasma using protein G plates, followed by

N-glycan release by PNGase F digestion, labeling with 2-AB fluorescent dye, and purification. The labeled

N-glycans were separated using hydrophilic interaction chromatography (UPLC), data eprocessing involved log transformation and batch correction. A predictive GlycanAge model was developed using multivariate analysis and was validated through random subsampling. Additional analyses were performed to explore the relationship between glycosylation and age. Variations in IgG Fc glycosylation, which influence immune function, have been linked to inflammation and biological aging, which is supported by reduced glycosylation in certain aging syndromes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess biological age and glycosylation following oral surgery. Consequently, the results were compared with standard telomere length measurements obtained from peripheral leukocyte DNA (T/S ratio) via quantitative PCR in the participants of an ongoing prospective study by our group. Individual outcomes were benchmarked against age-specific data obtained from Ganzimmun Diagnostics AG (Mainz, Germany).

2.4. Blood Tests

Peripheral blood was drawn before and after treatment to analyze the TH1/TH2 ratio and IL-10 serum levels using standard laboratory techniques. Blood samples were sent to the Institut für Medizinische Diagnostik (Berlin, Germany) for hematological analysis.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test was performed to assess significant differences in the means of hematological parameters, telomere length (n=6, from the ongoing prospective study), and IgG N-glycan profiles (n=1, this case report) pre-intervention and 4 months post-intervention for IgG N-glycan, and 3 weeks for leukocyte DNA (T/S ratio). An estimated plot was generated from the collected data to interpret the intervention effects visually. The graph displays the mean values of the measurements, with error bars representing standard deviation. The significance level was set at 95% (P < 0.05) to obtain valuable insights into the effects of the intervention.

2.6. Treatment Outcomes and Clinical Relevance

Three immediate implants (immediately after tooth extraction) and one late implant (at least three months after tooth removal) were placed. No abnormalities in wound healing and no signs of infection, necrosis, or adverse reactions were observed at any time point. No material loss was observed; no abnormal premature surgical intervention was required during the healing period. After four months, the patient underwent oral rehabilitation, including prosthetic treatment, and the implant survival rate (i.e., implant staying in place) was 100%.

The SDS tissue-level implant allowed for 3-dimensional maintenance of the mesial and distal alveolar ridges as well as an ideal emergence profile for the crown (

Figure 2, 4d–e, 5d–e). In addition, the implant shape provided a space between the implant and buccal lamella, which was filled with PRF. Adequate vascular supply and lack of compressive forces in the alveolar space resulted in new bone formation and mucosal keratinization without requiring additional surgical augmentation [

21].

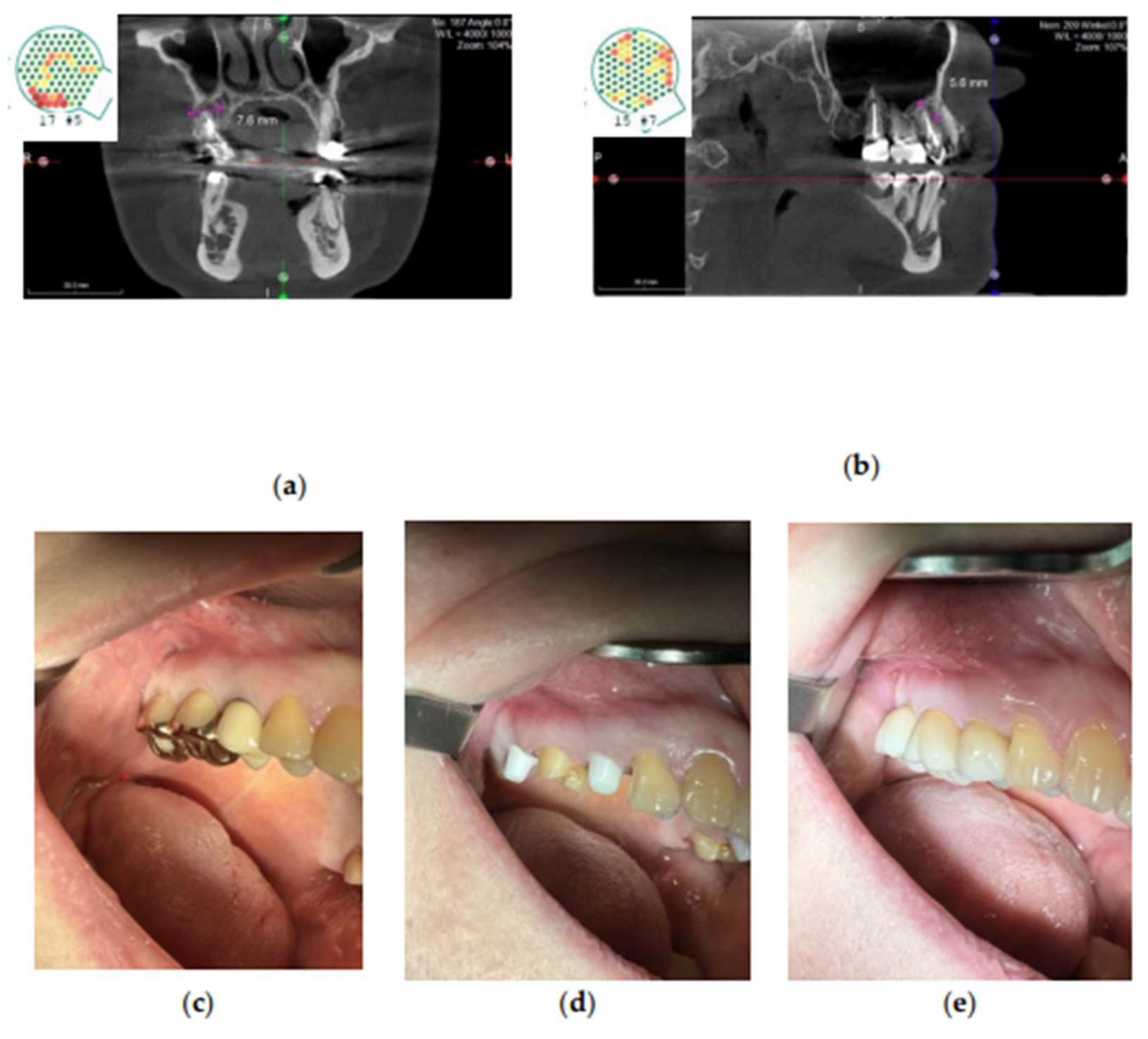

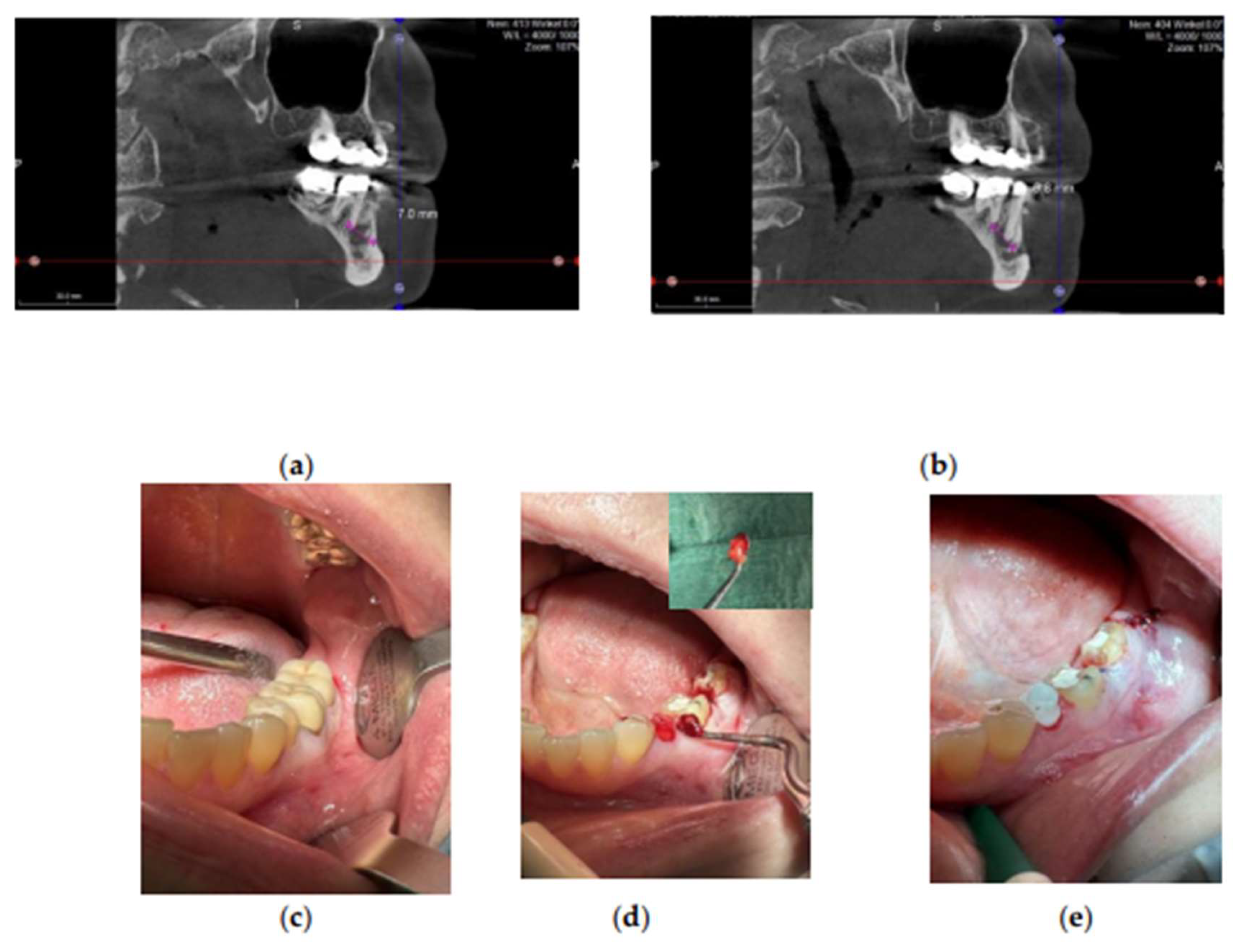

Figure 4.

Apical periodontitis associated with the root-treated tooth region 15–17. (a-b) FDOJ at the apical region marked by pink lines, shown in CaviTAU pre-operative imaging. Red and yellow areas indicate low-density bone, whereas green areas represent healthy bone. (c-e) Clinical view before implant placement (c), after implant preparation (d), and after prosthetic rehabilitation (e). Abbreviations: FDOJ, fatty degenerative osteonecrosis of the jawbone.

Figure 4.

Apical periodontitis associated with the root-treated tooth region 15–17. (a-b) FDOJ at the apical region marked by pink lines, shown in CaviTAU pre-operative imaging. Red and yellow areas indicate low-density bone, whereas green areas represent healthy bone. (c-e) Clinical view before implant placement (c), after implant preparation (d), and after prosthetic rehabilitation (e). Abbreviations: FDOJ, fatty degenerative osteonecrosis of the jawbone.

Figure 5.

Apical periodontitis associated with the root tooth region 35. (a-b) FDOJ at the apical region marked by pink lines. (c–e) Clinical view before implant placement (c), during FDOJ removal (d), and immediately after implant placement (e). Abbreviations: FDOJ, fatty degenerative osteonecrosis of the jawbone.

Figure 5.

Apical periodontitis associated with the root tooth region 35. (a-b) FDOJ at the apical region marked by pink lines. (c–e) Clinical view before implant placement (c), during FDOJ removal (d), and immediately after implant placement (e). Abbreviations: FDOJ, fatty degenerative osteonecrosis of the jawbone.

Post-operative hematochemical and inflammatory parameters improved significantly, with IL-10 levels increasing from 760 pg/mL to 1800 pg/mL (P = 0.0017) and TH1/TH2 Ratio from 0.6 to 6.1. These findings suggest that dental treatment positively influences the inflammatory response, indicating an active immune response to surgical trauma. This is a normal part of the healing process that protects against infections and promotes tissue repair [

31,

32].

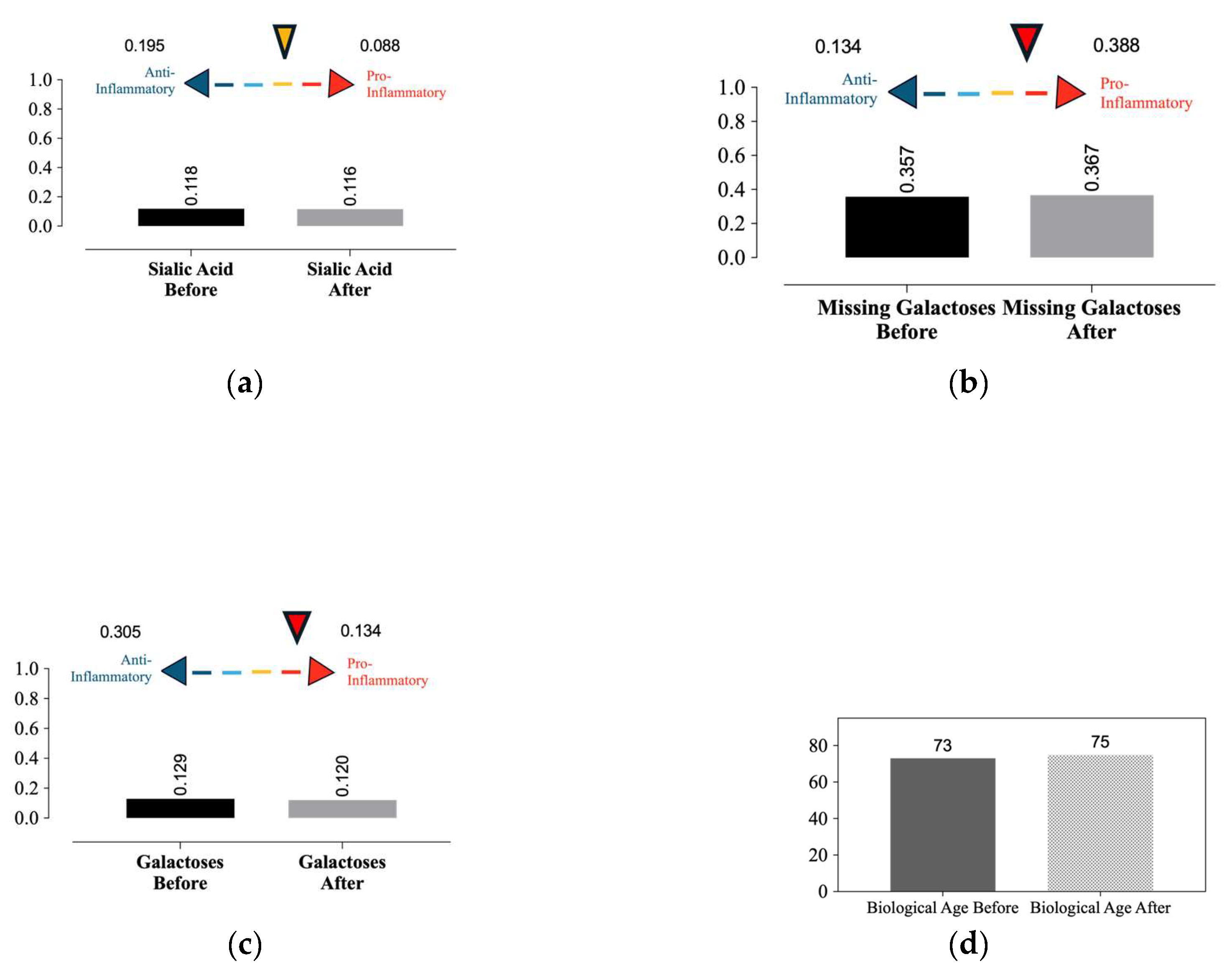

After 4-month period, biological aging increased from 73 to 75 years, as assessed by variations in glycan structures. Additionally, two protective indices against chronic inflammation—the presence of two galactoses and sialic acid—decreased from 0.129 to 0.120 and from0.118 to 0.116, respectively. Conversely, the missing galactose index increased from 0.357 to 0.367. Collectively, these results support the determination of aging and its effects on health during healing (

Figure 6).

Moreover, the overlap metrics with disease-specific glycans revealed a significant overlap in glycan indices between patients and those with coronary artery disease or perimenopause. There was also a notable overlap with increased risk of hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [

30]. However, further research with larger sample sizes is required to establish statistically significant changes in these parameters.

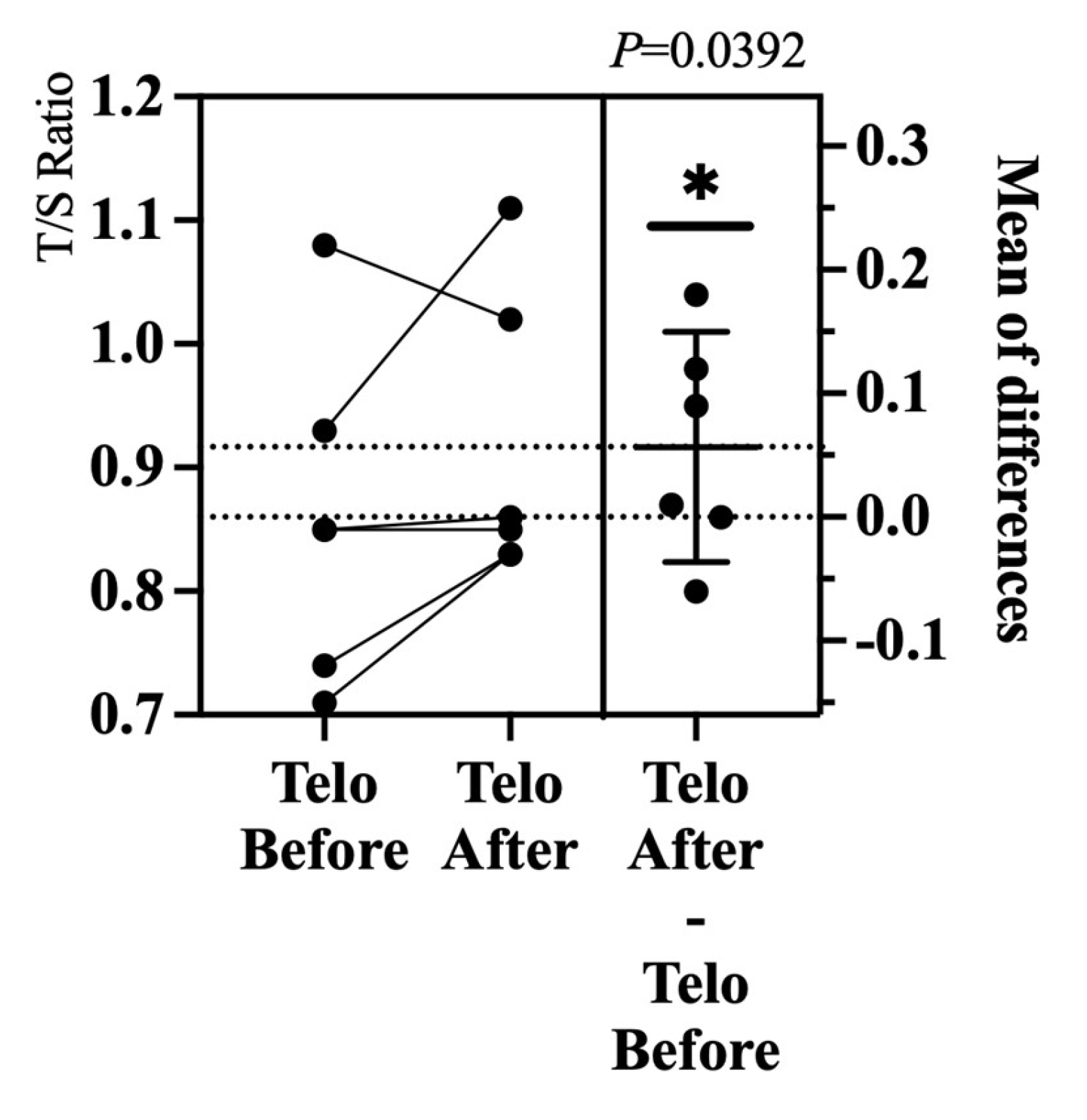

In comparison to an ongoing prospective study that follows the same surgical protocol and inclusion criteria, but measures telomere length through the T/S ratio obtained from peripheral leukocyte DNA, a significant increase in telomere length was observed (from 0.86 to 0.92, P= 0.0392) (

Figure 7). These findings suggest that surgery may enhance cellular health by increasing telomere length, indicating that implant placement contributes to a favorable inflammatory profile and potentially benefits the patients’ immune responses and overall health.

3. Discussion

Maintenance of oral health is crucial for healthy aging [

33]. Clinical strategies should prioritize the early diagnosis and prevention of biofilm-related diseases and promote bone preservation and soft tissue management. This case report highlights the importance of such approaches to achieve sustainable treatment success in both hard and soft tissues, potentially reducing the immune burden, improving patient satisfaction and overall health, and enhancing longevity.

Successful outcomes in implantology are related to implant osseointegration, long-term stability, and masticatory function. This depends on various factors related to the implant, patient, and operator [

34]. The placement of the implant in immunologically uncompromised alveolar bones is an important factor. We assessed the bone pre-operatively using transalveolar ultrasound (CaviTAU) to detect otherwise hidden pathophysiological changes such as those in the inferior region of tooth 35 and around wisdom tooth 18. These changes are characterized by low bone density and overexpression of the chemokines CCL5/RANTES [

35]. In the FDOJ, local ischemia can occur after tooth extraction. Without adequate blood supply, this leads to an imbalance in bone regeneration. Under these conditions, bone marrow mesenchymal cells are more likely to differentiate into adipocytes than that into osteoblasts, resulting in the formation of necrotic fatty tissue that fills the trabecular region of the bone. The FDOJ is often concealed beneath the intact cortical bone [

36,

37].

Histological assessment of the FDOJ confirmed overexpression of the chemokine CCL5/RANTES, a marker found in breast cancer, osteosclerosis, neurodegenerative lesions, and chronic fatigue syndrome [

6]. This suggests its role in systemic inflammatory disorders and disruption of regulatory processes. A minimally invasive surgical approach combined with thorough alveolar bone cleaning and PRF application helps restore homeostasis and promote bone formation.

Since 2013, aging research has focused on the decline in organismal function during adulthood. Despite its arbitrary classification, three criteria must be met for each hallmark of aging: (1) time-dependent changes associated with aging; (2) the ability to accelerate aging by enhancing the hallmark; and (3) most importantly, the potential to decelerate, halt, or reverse aging through therapeutic interventions targeting the hallmark. This study does not advocate for surgical protocols as anti-aging therapies but emphasizes that oral diseases must be addressed, as they can impair cellular function, leading to senescence and worsening systemic conditions, particularly in high-risk patients such as those with diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, or cancer.

Surgical trauma can induce cellular senescence, a normal response to stress and damage, followed by immune clearance. However, during biological aging or in the presence of chronic diseases, this clearance can be reduced, making senescence pathogenic due to the excessive secretion of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic factors. In the present case, the patient was 20 years older than her chronological age. Consequently, the host immune response, which is initially aimed at resolving or containing ongoing inflammation, may ultimately overwhelm the immune system over time. A clinical strategy that combines physical examination and medical history with preoperative assessment of biological age and immunomodulatory cytokines leads to more predictable outcomes [

11]. We explored biomarkers associated with cell aging, inflammation, TH1/TH2 Ratio and IL-10 levels. All oral infection sites were removed in a single procedure, with prompt restoration of oral and masticatory functions.

Previous studies have shown a positive correlation between telomere length, cellular energy performance, and the balance of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines following ceramic implant placement [

5]. These implants were used in the same treatment protocol as described here, emphasizing oral hygiene and vitamin supplementation for patients with non-adapted metal-alloy restorations, periapical cysts, and peri-implantitis related to titanium implants. This study highlights the potential benefits of ceramic implants in improving cellular health and modulating inflammatory responses. Consequently, ceramic implants may offer better outcomes, particularly in patients with metal hypersensitivity [

21,

38,

39].

Inflammation increases during aging (‘‘inflammaging’’), with systemic manifestations and local pathological phenotypes including arteriosclerosis, neuroinflammation, osteoarthritis, and intervertebral disc degeneration [

40]. In association with enhanced inflammation, immune function declines [

41]. T cell populations entail hyperfunction of pro-inflammatory TH1, defective immunosurveillance (with a negative impact on the elimination of virus-infected, malignant, or senescent cells), loss of self-tolerance (with a consequent age-associated increase in autoimmune diseases), and reduced maintenance and repair of biological barriers, all of which together favor systemic inflammation [

42].

This study has certain limitations that must be addressed. First, the reduction in proinflammatory markers after the therapeutic protocol suggests an overall health improvement, although the changes may result from systemic alterations rather than solely from ceramic implant placement, warranting further investigation into the correlation between cytokine release and inflammation.

Second, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the variations in glycan profiles and their relationship with biological age as indicators of systemic disease risk after ceramic implant placement. While acknowledging the limitations of this study, including the need for a larger experimental group and a longer follow-up period, future research may yield different results or confirm that glycan variation is not the optimal test for determining biological age after oral surgical intervention. Another limitation is the increased cost of tests for the patient, which might be difficult to implement in routine clinical practice, although it sheds light on the correlation between oral infections and systemic disease.

This study provides insights into the biocompatibility and long-term implications of ceramic dental implants. Further collaborative efforts and clinical studies are vital to develop advanced treatment options for all implant types, thereby enhancing treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a comprehensive evaluation of inflammatory biomarkers, telomere length, and glycan structures provided crucial insights into regenerative capacity and cellular aging. Although biomarkers are essential to measure progress, they are not the ultimate targets for achieving success. Advancements in the understanding of these factors could lead to therapeutic interventions that promote healthy aging, reduce inflammation, and support immunological sustainability. Moreover, this study highlights the importance of addressing the association between weakening of the immune system and oral disease progression. A deeper understanding of the effects of ceramic implants on patient health and tissue regeneration is vital to improve implant osseointegration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.; methodology, E.S., F.S and F.N.; software, E.S.; formal analysis, E.S. and F.S.; clinical assessment, F.S.; resources, E.S. and U.V.; data curation, E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.; writing—review and editing, F.S., C.S. and J.L.; visualization, E.S.; supervision, J.L.; project administration, E.S.; funding acquisition, U.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ceramics & Biological Dentistry Foundation (CBDF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki, with informed consent obtained. As it is a single case report and not generalizable research under HRA (Article 3a), ethics committee approval was not required per EKOS Ethikkommission Ostschweiz guidelines. www.sg.ch/home/gesundheit/ethikkommission.html

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient involved in this report. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Whittemore, K.; Vera, E.; Martínez-Nevado, E.; Sanpera, C.; Blasco, M.A. Telomere shortening rate predicts species life span. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 15122–15127. (Epub Jul 8 2019). PMID: 31285335, PMCID: PMC6660761. [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, K.; Fossel, M. Editorial: Telomere length and species lifespan. Front Genet 2023, 14, 1199667. PMID: 37139235, PMCID: PMC10150125. [CrossRef]

- Tavares, M.; Lindefjeld Calabi, K.A.; San Martin, L. Systemic diseases and oral health. Dent Clin North Am 2014, 58, 797–814. (Epub Aug 7 2014). PMID: 25201543. [CrossRef]

- Schick, F.; Lechner, J.; Notter, F. Linking dentistry and chronic inflammatory autoimmune diseases - Can oral and jawbone stressors affect systemic symptoms of atopic dermatitis? A case report. Int Med Case Rep J 2022, 15, 323–338. PMID: 35782227, PMCID: PMC9242433. [CrossRef]

- Schnurr, E.; Volz, K.U.; Mosetter, K.; Ghanaati, S.; Hueber, R.; Preussler, C. Interaction of telomere length and inflammatory biomarkers following zirconia implant placement: A case series. J Oral Implantol 2023, 49, 524–531. PMID: 38349660. [CrossRef]

- Lechner, J.; Rudi, T.; von Baehr, V. Osteoimmunology of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IL-6, and RANTES/CCL5: A review of known and poorly understood inflammatory patterns in osteonecrosis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2018, 10, 251–262. PMID: 30519117, PMCID: PMC6233471. [CrossRef]

- Settem, R.P.; Honma, K.; Stafford, G.P.; Sharma, A. Protein-linked glycans in periodontal bacteria: Prevalence and role at the immune interface. Front Microbiol 2013, 4, 310. PMID: 24146665, PMCID: PMC3797959. [CrossRef]

- Kapila, Y.L. Oral Health’s inextricable connection to systemic health: Special populations bring to bear multimodal relationships and factors connecting periodontal disease to systemic diseases and conditions. Periodontol 2000 2021, 87, 11–16. PMID: 34463994, PMCID: PMC8457130. [CrossRef]

- Lechner, J.; von Baehr, V.; Schick, F. RANTES/CCL5 signaling from jawbone cavitations to epistemology of multiple sclerosis - Research and case studies. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis 2021, 11, 41–50. PMID: 34262389, PMCID: PMC8275106. [CrossRef]

- Lechner, J.; Schulz, T.; Lejeune, B.; von Baehr, V. Jawbone cavitation expressed RANTES/CCL5: Case studies linking silent inflammation in the jawbone with epistemology of breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press); Dove Med. Press 2021, 13, 225–240. PMID: 33859496, PMCID: PMC8044077. [CrossRef]

- Froum, S.J.; Hengjeerajaras, P.; Liu, K.-Y.; Maketone, P.; Patel, V.; Shi, Y. The link between periodontitis/peri-implantitis and cardiovascular disease: A systematic literature review. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2020, 40, e229–e233. [CrossRef]

- Feuerriegel, G.C.; Burian, E.; Sollmann, N.; Leonhardt, Y.; Burian, G.; Griesbauer, M.; Bumm, C.; Makowski, M.R.; Probst, M.; Probst, F.A.; et al. Evaluation of 3D MRI for early detection of bone edema associated with apical periodontitis. Clin Oral Investig 2023, 27, 5403–5412. (Epub Jul 18 2023). PMID: 37464086, PMCID: PMC10492681. [CrossRef]

- Cotti, E.; Schirru, E. Present status and future directions: Imaging techniques for the detection of periapical lesions. Int Endod J 2022, 55, Suppl 4, 1085–1099. (Epub Sep 20 2022). PMID: 36059089. [CrossRef]

- Figdor, D. Apical periodontitis: A very prevalent problem. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002, 94, 651–652. PMID: 12464886. [CrossRef]

- Diederich, J.; Schwagten, H.; Biltgen, G.; Lechner, J.; Müller, K.E. Reduction of inflammatory RANTES/CCL5 serum levels by surgery in patients with bone marrow defects of the jawbone. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2023, 15, 181–188. PMID: 37705670, PMCID: PMC10496923. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Ryu, J.S.; Shimono, M.; Lee, K.W.; Lee, J.M.; Jung, H.S. Differential healing patterns of mucosal seal on zirconia and titanium implant. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 796. PMID: 31333481, PMCID: PMC6616312. [CrossRef]

- French, D.; Ofec, R.; Levin, L. Long term clinical performance of 10 871 dental implants with up to 22 years of follow-up: A cohort study in 4247 patients. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2021, 23, 289–297. (Epub Mar 25 2021). PMID: 33768695, PMCID: PMC8359846. [CrossRef]

- Roccuzzo, A.; Weigel, L.; Marruganti, C.; Imber, J.C.; Ramieri, G.; Sculean, A.; Salvi, G.E.; Roccuzzo, M. Longitudinal assessment of peri-implant diseases in patients with and without history of periodontitis: A 20-year follow-up study [Internet]. Int J Oral Implantol (Berl) 2023. Available online: http://ClinicalTrials.gov, 16, 211–222.

- Berglundh, T.; Mombelli, A.; Schwarz, F.; Derks, J. Etiology, pathogenesis and treatment of peri-implantitis: A European perspective. Periodontol 2000 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 38305506. [CrossRef]

- Jansson, L.; Guan, T.; Modin, C.; Buhlin, K. Radiographic peri-implant bone loss after a function time up to 15 years. Acta Odontol Scand 2022, 80, 74–80. (Epub Jul 30 2021). PMID: 34330198. [CrossRef]

- Schnurr, E.; Sperlich, M.; Sones, A.; Romanos, G.E.; Rutkowski, J.L.; Duddeck, D.U.; Neugebauer, J.; Att, W.; Sperlich, M.; Volz, K.U.; et al. Ceramic implant rehabilitation: Consensus statements from joint congress for ceramic implantology: Consensus statements on ceramic implant. J Oral Implantol 2024, 50, 435–445. PMID: 38867376. [CrossRef]

- Lechner, J.; von Baehr, V.; Notter, F.; Schick, F. Osseointegration and osteoimmunology in implantology: Assessment of the immune sustainability of dental implants using advanced sonographic diagnostics: Research and case reports. J Int Med Res 2024, 52, 3000605231224161. PMID: 38259068, PMCID: PMC10807457. [CrossRef]

- Lechner, J.; Von Baehr, V. RANTES and fibroblast growth factor 2 in jawbone cavitations: Triggers for systemic disease? Int J Gen Med 2013, 6, 277–290. [CrossRef]

- Ghanaati, S.; Choukroun, J.; Volz, U.; Hueber, R.; Mourão, C.A.B.; Sader, R.; Kawase-Koga, Y.; Mazhari, R.; Amrein, K.; Meybohm, P.; et al. One hundred years after vitamin D discovery: Is there clinical evidence for supplementation doses? Int J Growth Factors Stem Cells Dent 2020, 3, 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Swiss Biohealth Academy. The Swiss biohealth Concept®. Available online: https://www.swiss-biohealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2021_Swiss-Biohealth-Concept-de-web.pdf (accessed on Jul 27, 2023).

- Alkhouri, S.; Smeets, R.; Stolzer, C.; Burg, S.; Volz, K.U.; Gosau, M.; Henningsen, A. Does placement of one-piece zirconia implants influence crestal bone loss? Retrospective evaluation 1 year after prosthetic loading. Int J Oral Implantol (Berl) 2023, 16, 43–51.

- Schnurr, E.; Volz, K.U. Die Beziehung zwischen oralen Infektionen, Biokorrosion und systemischer Gesundheit: Ein Behandlungskonzept. Available online: https://sportaerztezeitung.com/rubriken/therapie/13828/oralen-infektionen-biokorrosion-und-systemischer-gesundheit/ (accessed on Apr 17, 2023).

- Ghanaati, S.; Booms, P.; Orlowska, A.; Kubesch, A.; Lorenz, J.; Rutkowski, J.; Landes, C.; Sader, R.; Kirkpatrick, C.; Choukroun, J. Advanced platelet-rich fibrin: A new concept for cell-based tissue engineering by means of inflammatory cells. J Oral Implantol 2014, 40, 679–689. [CrossRef]

- Domb, W.C. Ozone therapy in dentistry. A brief review for physicians. Interv Neuroradiol 2014, 20, 632–636. (Epub Oct 17 2014). PMID: 25363268, PMCID: PMC4243235. [CrossRef]

- Krištić, J.; Vučković, F.; Menni, C.; Klarić, L.; Keser, T.; Beceheli, I.; Pučić-Baković, M.; Novokmet, M.; Mangino, M.; Thaqi, K.; et al. Glycans are a novel biomarker of chronological and biological ages. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014, 69, 779–789. (Epub Dec 10 2013). PMID: 24325898, PMCID: PMC4049143. [CrossRef]

- Nickenig, H.J.; Schlegel, K.A.; Wichmann, M.; Eitner, S. Expression of interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha in soft tissue over ceramic and metal implant materials before uncovering: A clinical pilot study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2012, 27, 671–676. PMID: 22616062.

- Kany, S.; Vollrath, J.T.; Relja, B. Cytokines in inflammatory disease. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 6008. [CrossRef]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W.; et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat Med 2019, 25, 1822–1832. (Epub Dec 5 2019). PMID: 31806905, PMCID: PMC7147972. [CrossRef]

- Esplin, K.C.; Tsai, Y.W.; Vela, K.; Diogenes, A.; Hachem, L.E.; Palaiologou, A.; Cochran, D.L.; Kotsakis, G.A. Peri-implantitis induction and resolution around zirconia versus titanium implants. J Periodontol 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 39003566. [CrossRef]

- Lechner, J.; Schmidt, M.; von Baehr, V.; Schick, F. Undetected jawbone marrow defects as inflammatory and degenerative signaling pathways: Chemokine RANTES/CCL5 as a possible link between the jawbone and systemic interactions? J Inflamm Res 2021, 14, 1603–1612. [CrossRef]

- Tencerova, M.; Kassem, M. The bone marrow-derived stromal cells: Commitment and regulation of adipogenesis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2016, 7, 127. PMID: 27708616, PMCID: PMC5030474. [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, Y.; Ono, W.; Ono, N. Toward marrow adipocytes: Adipogenic trajectory of the bone marrow stromal cell lineage. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 882297. PMID: 35528017, PMCID: PMC9075612. [CrossRef]

- Müller-Heupt, L.K.; Schiegnitz, E.; Kaya, S.; Jacobi-Gresser, E.; Kämmerer, P.W.; Al-Nawas, B. The German S3 guideline on titanium hypersensitivity in implant dentistry: Consensus statements and recommendations. Int J Implant Dent 2022, 8, 51. [CrossRef]

- Thiem, D.G.E.; Stephan, D.; Kniha, K.; Kohal, R.J.; Röhling, S.; Spies, B.C.; Stimmelmayr, M.; Grötz, K.A. Correction: German S3 guideline on the use of dental ceramic implants. Int J Implant DentInt J Implant Dent 2023, 9, 2. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. (Epub Jan 3 2023). PMID: 36599349. [CrossRef]

- Mogilenko, D.A.; Shpynov, O.; Andhey, P.S.; Arthur, L.; Swain, A.; Esaulova, E.; Brioschi, S.; Shchukina, I.; Kerndl, M.; Bambouskova, M.; et al. Comprehensive profiling of an aging immune system reveals clonal GZMK+ CD8+ T cells as conserved hallmark of inflammaging. Immunity 2021, 54, 99–115.e12. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, E.; Gómez de Las Heras, M.M.; Gabandé-Rodríguez, E.; Desdín-Micó, G.; Aranda, J.F.; Mittelbrunn, M. The role of T cells in age-related diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22, 97–111. (Epub Jun 7 2021). PMID: 34099898. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).