1. Introduction

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are common among children1). Of the various RTIs, upper respiratory tract infections present as common cold caused by viral infections2), and the rate of occurrence is quite high, especially among children2). Moreover, viruses have been detected in many in-patients with respiratory infectious diseases3)4)5)6).

Multiplex real-time PCR has been used in recent years for the survey of viral pathogens in RTIs 3)6); it has enabled the rapid and simultaneous detection of various viruses 7)8)9).

Despite its high sensitivity, the simultaneous detection of multiple viruses remains a challenge, leading to potential difficulties in interpretation.

This study aimed to use quantitative multiplex PCR in pediatric patients admitted to our hospital due to respiratory infections to not only identify the types of viruses but also compare the quantity of each virus in cases where multiple viruses are detected, thereby enabling a comprehensive analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Collection

From April 2022 to March 2023, we surveyed all pediatric cases of RTI that were admitted to the pediatric department of Kawasaki Medical School Hospital.

We obtained nasopharyngeal samples from the patients and recorded their age, sex, presence of underlying conditions, and the diseases that led to their hospitalization.

2.2. Nucleic Acid Isolation and RT-qPCR Tests

Real-time PCR was performed using FTD Respiratory Pathogens 21® (RIKEN Genesis). It determined the cycle threshold (Ct) values for 20 respiratory viruses, including influenza (A/B), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rhinovirus, coronavirus NL63, 229E, OC43, HKU1, parainfluenza virus 1,2,3, human metapneumovirus (A/B), influenza A (H1N1), adenovirus, bocavirus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, enterovirus, and parechovirus1).

2.3. Evaluation of Ct Values

With reference to previous reports2), we classified the Ct values. Specifically, Ct values below 25 were classified as "very high," Ct values between 25 and 30 were considered "high," Ct values between 30 and 35 were "moderate," and Ct values 36 or above were classified as "low."

If more than one virus was detected in a patient, the virus with the lowest Ct value was considered the main virus. In other words, if the Ct values for two detected viruses were "very high" and "moderate," the virus with the "Very high" Ct value was considered the main virus.

3. Results

3.1. Background of the Cases under Consideration

Table 1 presents the background of the cases under consideration. The total number of patients included in the study was 77, with a median age of 1 year. Among them, 41 were male and 36 were female.

Among the cases under consideration, 17 cases (22.1%) had underlying medical conditions as shown on the slides. Acute pneumonia was the most common disease that led to their hospitalization.

Other prevalent conditions included acute bronchiolitis (16 patients), asthmatic bronchitis (12 patients), and bronchial asthma (9 patients). Diseases causing expiratory wheezing were predominant.

For conditions causing expiratory wheezing, we categorized the diseases based on the presence or absence of fever or the use of steroids.

3.2. Detected Viruses

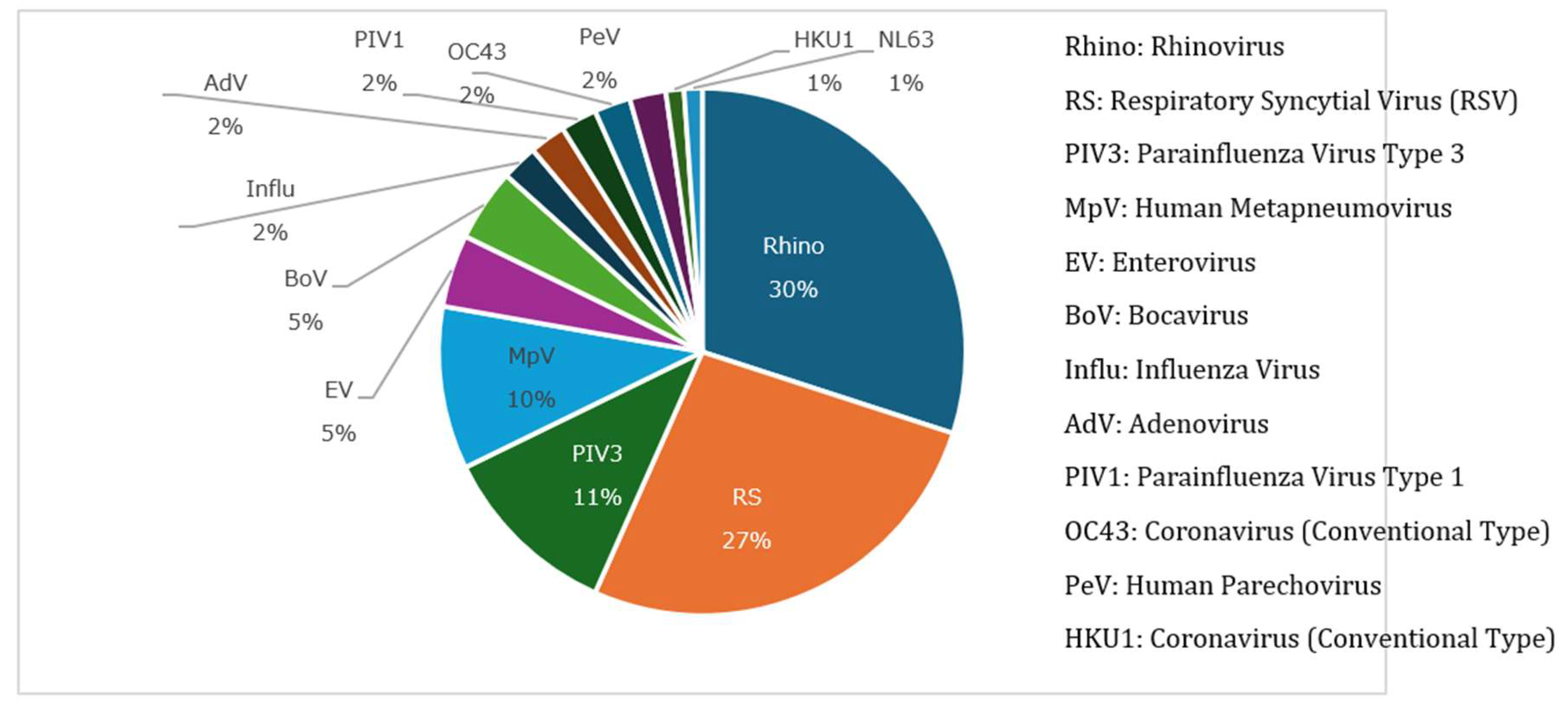

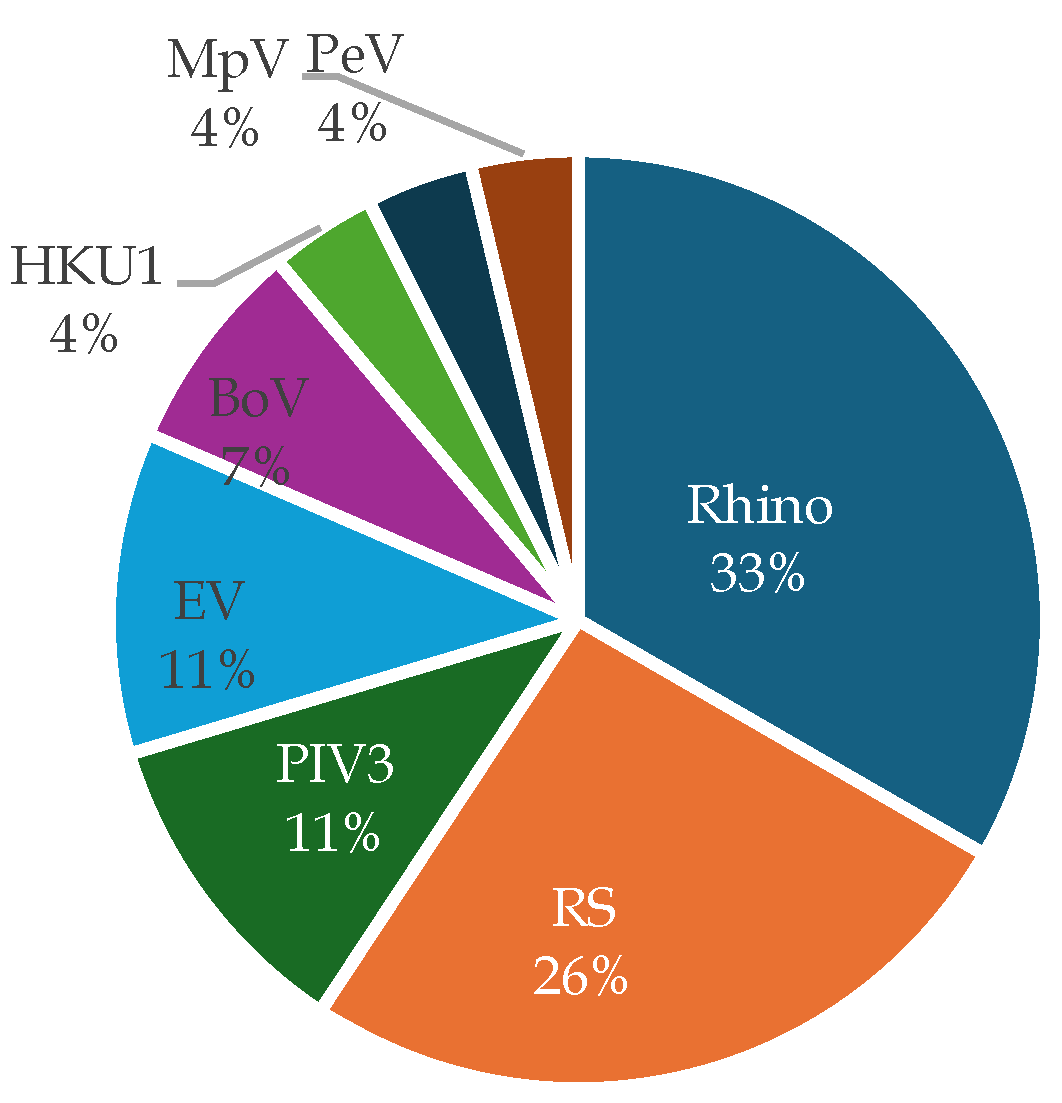

The types of viruses detected in the samples are shown in

Figure 2. Some forms of the virus were detected in 87% of the cases. The viruses detected, in descending order of frequency, were rhinovirus in 30%, RSV in 27%, parainfluenza type 3 in 11%, and human metapneumovirus in 10%.

Figure 1.

Some form of virus was detected in 87% of the total cases. The viruses detected, in descending order of frequency, were rhinovirus at 30%, RSV at 27%, parainfluenza type 3 at 11%, and human metapneumovirus at 10%.

Figure 1.

Some form of virus was detected in 87% of the total cases. The viruses detected, in descending order of frequency, were rhinovirus at 30%, RSV at 27%, parainfluenza type 3 at 11%, and human metapneumovirus at 10%.

3.3. Cases with Multiple Detected Viruses and Their Background

The cases with multiple viruses and their background are shown in

Table 2.

Among the 67 cases in which viruses were detected, 18 (26.9%) had multiple viruses. The median age for such cases was 1 year, and no significant difference in sex distribution was seen compared to that in all the cases. Although the proportion of patients with underlying medical conditions was equivalent to the overall cases at 22.2%, all underlying conditions were related to bronchial asthma.

Bronchial asthma was the most common disease leading to hospitalization in patients with multiple detections, accounting for 66.7% of all bronchial asthma cases.

Other diseases associated with expiratory wheezing, such as acute bronchiolitis and asthmatic bronchitis, were also prevalent. However, only one among all the cases of acute pneumonia showed multiple virus detections.

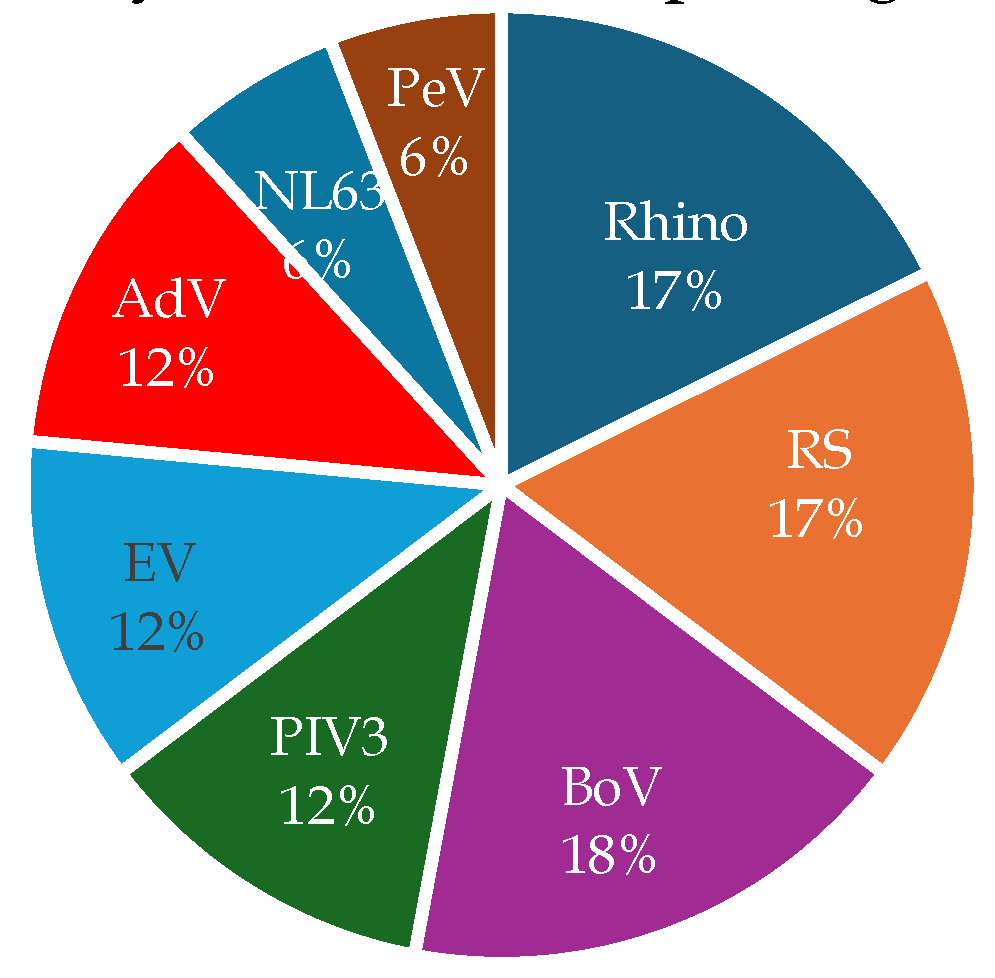

3.4. Virus Profiles in Cases with Multiple Viruses (n = 44)

Virus profiles in cases where multiple viruses were detected are shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. As shown in

Figure 2, among the viruses identified as 'main,' such as rhinovirus, RS, and parainfluenza type 3, no significant difference was seen in their overall proportions.

On the other hand, some viruses were identified as 'non-main,' in addition to rhinovirus, RS, and parainfluenza type 3, such as bocavirus and adenovirus, as indicated in

Figure 3, Notably, the viruses detected as 'non-main,' meaning those with lower viral loads, would require careful interpretation regarding whether they are causative pathogens.

4. Discussion

Multiplex PCR assays have recently been developed for clinical settings and have become increasingly popular. However, most of them provide qualitative results, that is, positive or negative results3). Therefore, the evaluation of pathogens in a child is still difficult when multiple viruses are present. Multiple viruses have been reported to be found in hospitalized children4)5); the detection rate of multiple viruses in samples taken from hospitalized children with respiratory diseases ranges from 18% to 42.5%.

Kouni et al. reported microarray data in which 70.1% were viruses; RS virus types A and B (56.6%) were the most identified, followed by parainfluenza virus (PIV) (29.7%) and rhinovirus (RV) (18.4%)4). Although the results showed some differences in the detection rate, the types of viruses detected frequently were almost the same as those in our reports.

Martin et al. reported quantitative PCR data for detecting viruses in samples taken from children treated for respiratory illness at their hospital; 63% of the children were detected with at least one virus. RS was the most frequently detected (25%), followed by influenza (Flu) A and adenovirus (AdV). Since rhinovirus was not included in this qPCR, the distribution of detected viruses did not differ to some degree5).

Furthermore, these reports investigated the presence of multiple viruses (i.e., co-infection) in a child. Kouni’s report showed that 42.5% of children were infected with more than two viruses. The most frequent pattern of co-infection was RSVA-RSVB (27.2%), followed by RSV–INFL (11.8%) and RSV–RV (10.6%)4). In another report, multiple viruses were detected in 18% of the enrolled children. Among them, the most common co-infection was Ad⁄-RSV(23.3%), followed by RS-CoV (16.5%) and AdV-Flu A (13.6%). RS viruses are common not only in single infections but also in multiple infections.

In a previous report, many viruses, including RV, were investigated, but the PCR used was not quantitative. Therefore, they were unable to identify the viruses that were the main pathogens among the multiple viruses. In later reports, PCR was quantitative and RV, one of the main pathogens, was found predominant in single-detection as well as in multiple detections, as in the previous report and in our current report. Furthermore, the relationships between co-infections and the severity of respiratory diseases were referred to in both past reports, although the opinion was different between them at that time.

Compared to these reports, we investigated many viruses, including RV, using quantitative PCR and focused not on the severity, but on the types of respiratory diseases, such as obstructive respiratory diseases, including bronchial asthma, acute bronchiolitis, and asthmatic bronchitis. For example, many respiratory viruses, which cause a type of obstructive respiratory disease, have been detected in adult patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease6)7). Furthermore, the frequency of detection is reportedly influenced by the severity of FEV17). Obstructive respiratory conditions may lead to viral invasion.

However, the evaluation of whether the detected viruses are real pathogens or just carriages is difficult when multiple viruses are detected in one person. Gazeau et al. reported the diagnoses of 44 hospitalized patients with various respiratory manifestations based on a quantitative PCR assay, and all but one, who were detected at less than 35 Ct (high values), were consistent with the clinical history8).

As described previously, we referred to the standard in Gazeau’s reports for the evaluation of viral load; therefore, the values of Ct are very important. In the present study, most viruses were detected as both main and non-main viruses.

Whether the detected viruses are real pathogens is difficult to judge when multiple viruses are detected in one person, unless qPCR assays are performed.

There are two limitations in our study. First, it was a single-center study. Therefore, the number of children enrolled was low. Moreover, quantitative PCR is not as popular as qualitative PCR owing to its high cost. Hence, a detailed analysis using a qualitative approach, such as our data, is considered very important. Second, there was no standard Ct in qPCR to determine whether the detected viruses were genuine pathogens. Therefore, we had to refer to a previous report2). Taken together, a more detailed investigation, including a comparison between the values of Ct and clinical courses, would be required in the future.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we analyzed the viral etiological agents responsible for respiratory tract diseases. The most prevalent identified virus was SARS-CoV-2, which was significantly more common in adults, regardless of sex. Although the spread of COVID-19 has been a major public health concern, SARS-CoV-2 may not be the only pathogen responsible for respiratory infections. Other viruses, such as adenovirus, rhinovirus, metapneumovirus, enteroviruses, and influenza, have been detected more frequently in mono-infections as well as in co-infections (mainly with SARS-CoV-2). Notably, respiratory tract coinfections, depending on the patient’s immune system status and comorbidities, usually result in a worse prognosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.; methodology, A.K., K.W., M.K., I.W., and A.B.; statistical analysis, J.W.; table and figure preparation, J.W., M.K., and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; and writing—review and editing, K.W. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Medicine Institute (internal funding).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require approval from a bioethics committee. It was part of routine diagnostics in a medical laboratory. All patients completed a laboratory form providing consent for the collection of material for testing and for the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Informed Consent Statement

The study was part of routine diagnostics in a medical laboratory. The samples used for the scientific research were analyzed anonymously. Viral genetic material was the object of interest, and human material was not analyzed.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the staff of the department of pediatrics, Kawasaki Medical Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mandell, L.A. Etiologies of acute respiratory tract infections. Clin Infect Dis 2005, 41, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terho Heikkinen; Asko Järvinen. Lancet. The common cold 2003, 361, 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Anshu Kumar; Ashish Bahal; Lavan Singh; S.M. Ninawe; Naveen Grover; Neha Suman. Utility of multiplex real-time PCR for diagnosing paediatric acute respiratory tract infection in a tertiary care hospital. Med J Armed Forces India (Epub 2021 Jul 31). 2023, 79, 286–291. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hien T., Pham; Phuc T.T., Nguyen; Sinh T., Tran; Thuy, T.B. Phung. Clinical and Pathogenic Characteristics of Lower Respiratory Tract Infection Treated at the Vietnam National Children’s Hospital. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2020, 2020, 7931950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora De Conto; Francesca Conversano; Maria Cristina Medici; Francesca Ferraglia; Federica Pinardi; Maria Cristina Arcangeletti; Carlo Chezzi; Adriana Calderaro. Epidemiology of human respiratory viruses in children with acute respiratory tract infection in a 3-year hospital-based survey in Northern Italy. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis (Epub 2019 Jan 17). 2019, 94, 260–267. [CrossRef]

- Anuja, A. Sonawane; Jayanthi Shastri; Sandeep B. Bavdekar. Respiratory Pathogens in Infants Diagnosed with Acute Lower Respiratory Tract Infection in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Western India Using Multiplex Real Time PCR. Indian J Pediatr (Epub 2019 Jan 14). 2019, 86, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirta Mesquita Ramirez; Miria Noemi Zarate; Leonidas Adelaida Rodriguez; Victor Hugo Aquino. Performance evaluation of Biofire Film Array Respiratory Panel 2.1 for SARS-CoV-2 detection in a pediatric hospital setting. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0292314. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morad Guennouni; Meriem Rachidi; Toufik Benhoumich; Hind Bennani; Mounir Bourrous; Fadl Mrabih Rabou Maoulainine; Said Younous; Mohamed Bouskraoui; Nabila Soraa. Epidemiology of Respiratory Pathogens in Children with Severe Acute Respiratory Infection and Impact of the Multiplex PCR Film Array Respiratory Panel: A 2-Year Study. Int J Microbiol 2021, 2021, 2276261. [CrossRef]

- Adv Virol. 2017:2017:1324276. Epub 2017 Aug 29. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).