1. Introduction

Fabry disease (FD) is a progressive, X-linked inherited disorder characterized by a decrease or deficiency in α-galactosidase enzyme activity, resulting in various symptoms [

1]. Symptoms include skin lesions, peripheral neuropathy, stroke, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, renal failure, and other complications [

1]. The signs and symptoms of this progressive disease typically begin in childhood and include skin lesion, gastrointestinal symptoms, and peripheral neuropathy. End-organ involvement, including kidney dysfunction, and cardiac involvement typically in adulthood [

2].

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) was approved for the treatment of FD in the USA and EU in 2001 and in Japan in 2004. Newborn screening (NBS) for FD has been performed since August 2006 in the western region of Japan [

3]. The prevalence of FD in Japan was previously reported to be 1/7057 [

4].

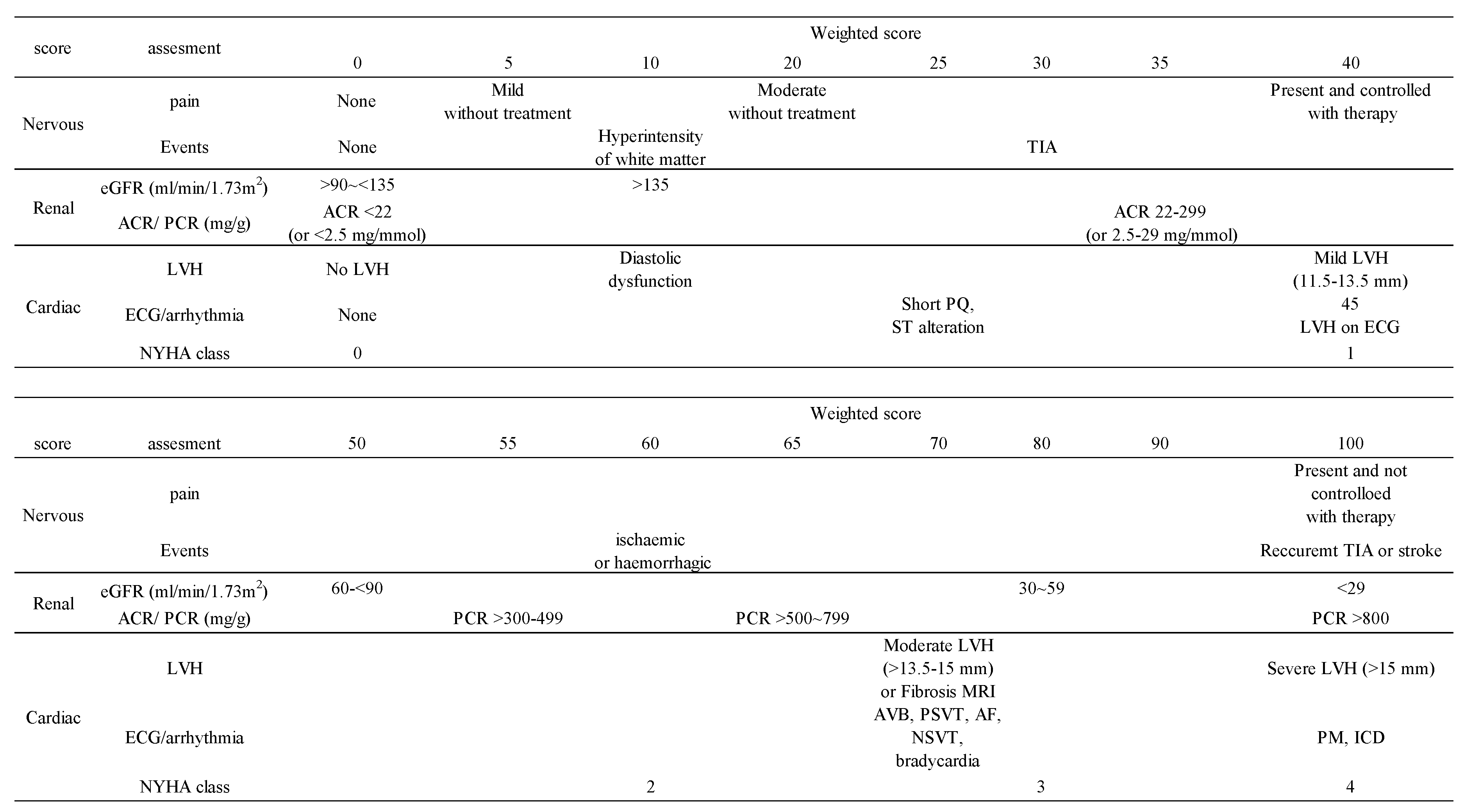

Two disease severity scoring system for FD, the Maintz Severity Score Index (MSSI) and Fabry Disease Severity Scoring System (DS3), have been validated [

5,

6]. These two scores provide an index of disease severity at a single point, and do not allow evaluation of the clinical course over time. Clinical stability of treated patients is indicative of the efficacy of ERT, and untreated patients who became clinically unstable may need to be initiated on treatment with ERT. FAbry STabilization indEX (FASTEX) scores are an innovative tool for the assessment of FD symptoms and measures clinical deterioration as the score increases [

7]. FASTEX is proposed that may allow quick and easy estimation of disease stability or progression for FD in adults. Accurate assessment of clinical stability and evaluation of ERT efficacy is essential, even if clinical symptoms are poor in pediatric patients with FD. However, the effectiveness of FASTEX in pediatric FD patients has not yet been examined.

Therefore, the present study investigated the potential of FASTEX as a tool to assess the effectiveness of treatment for pediatric FD patients.

2. Materials and Methods

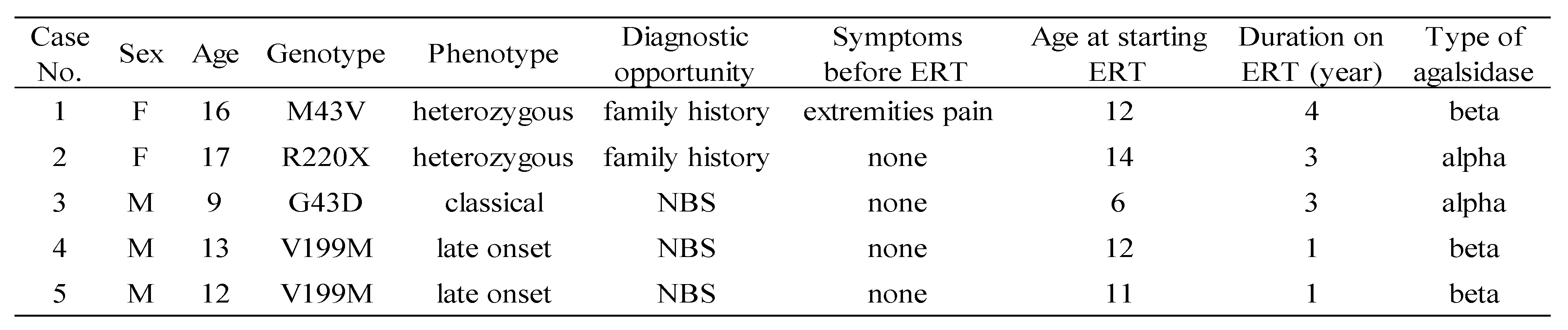

We conducted FASTEX scoring on 5 FD cases receiving ERT at our department by September 2022 (1 classical-type male, 2 late-onset males, and 2 heterozygous females). Average age at the start of treatment was 11 years, and the average duration of treatment was 3.4 years. The characteristics of these cases are shown in

Table 1.

We used FASTEX to evaluate the following domains: nervous system; pain, cerebrovascular events, renal; proteinuria and/or urinary albumin excretion, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and cardiac; echocardiography parameters, electrocardiograph parameters, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class (

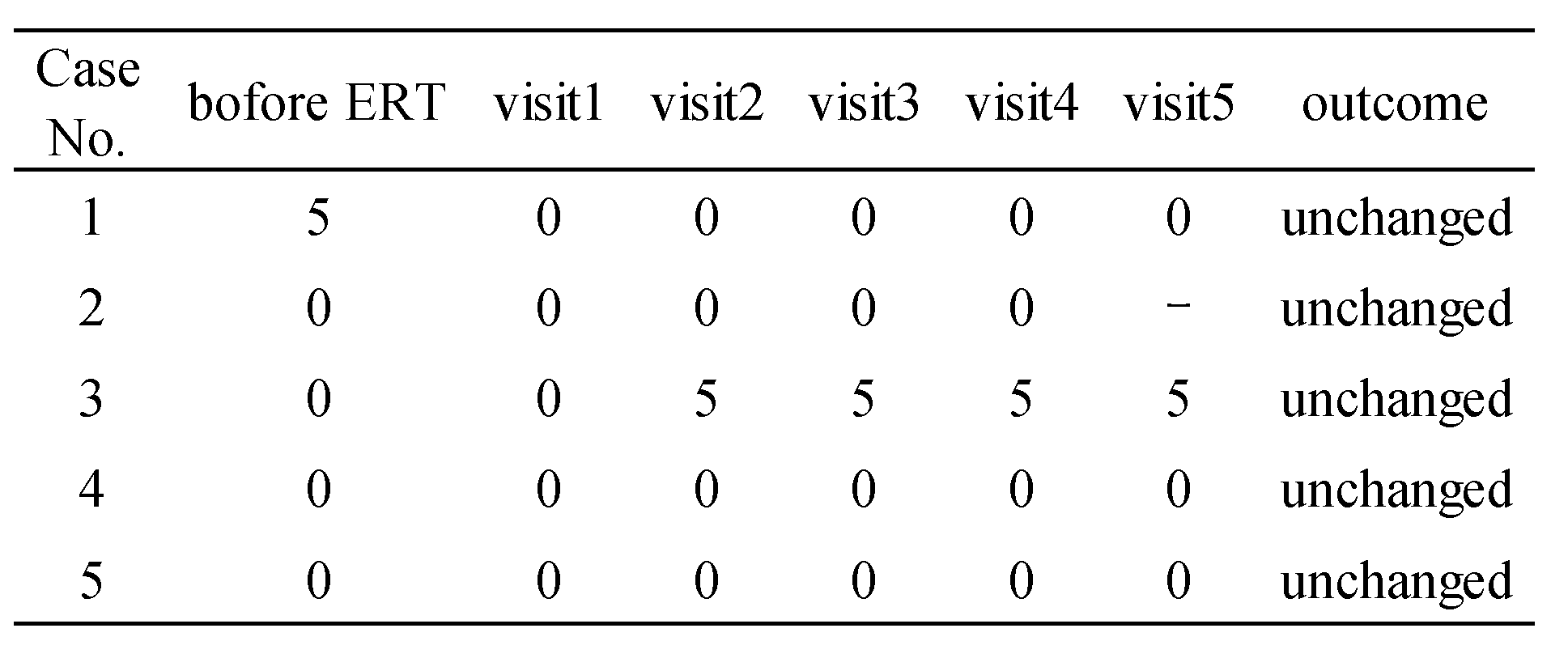

Table 2). We performed FASTEX scoring before and every six months to one year after the initiation of treatment (

Table 3). We defined a change in score of 20% or less from the baseline as clinically unchanged.

3. Results

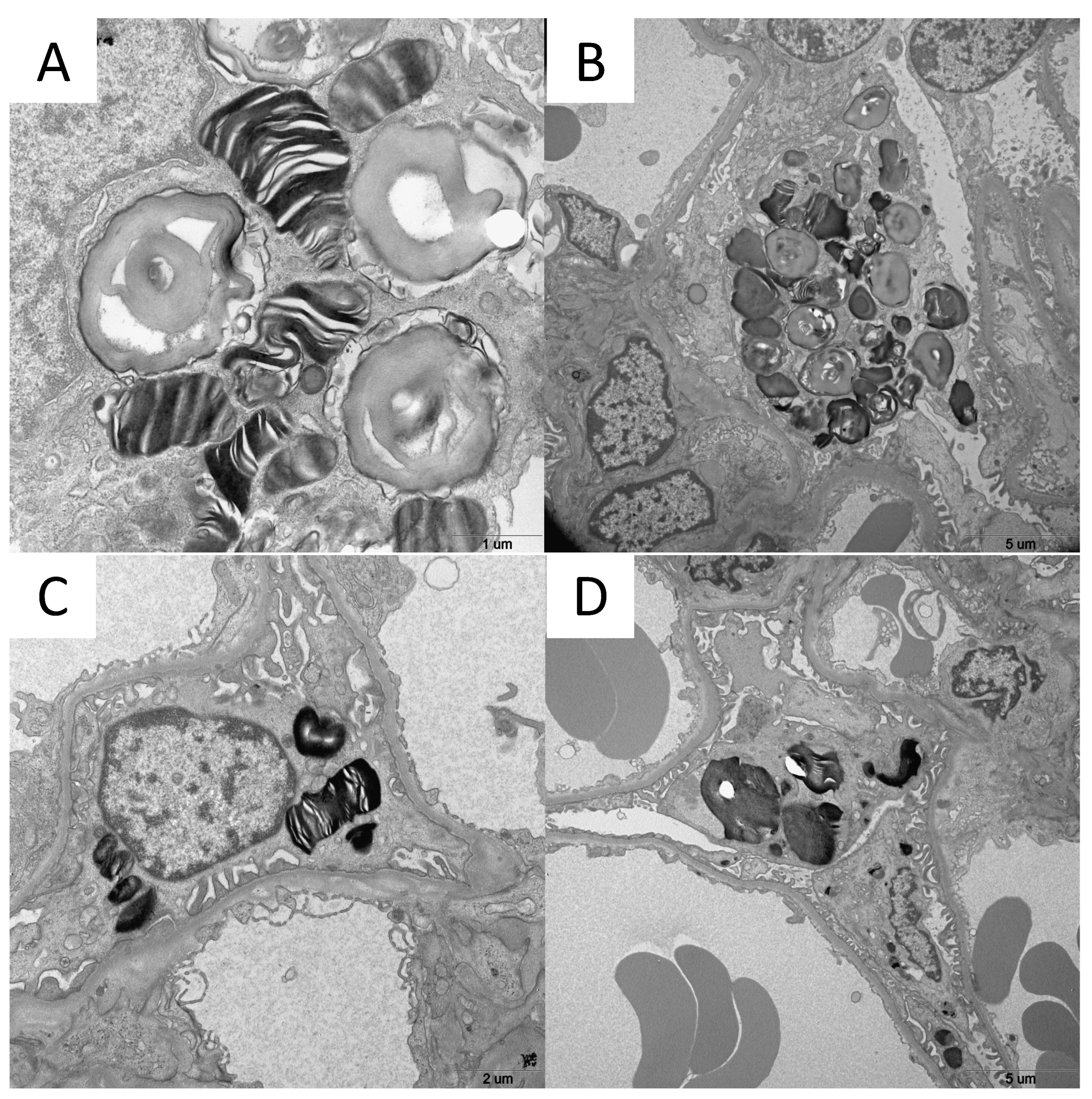

Case 1 was a 16-year-old girl. She had a family history of FD, was diagnosed, and

GLA gene testing revealed the M43V variant. She had mild leg pain on exercise, urinalysis indicated Mulberry bodies, and renal biopsy showed Gb3 accumulation in podocytes by electron microscopy (

Figure 1-A). ERT with agalsidase beta was initiated at the age of 12 years. Pain in the extremities improved after the initiation of ERT, and FASTEX scores decreased from 5 to 0.

Case 2 was a 17-year-old girl. She had a family history of FD, was diagnosed, and

GLA gene testing revealed the R220X variant. Urinalysis indicated Mulberry bodies and renal biopsy showed Gb3 accumulation in podocytes by electron microscopy (

Figure 1-B). ERT with agalsidase alpha was initiated at the age of 14 years. No changes were observed in symptoms following the initiation of ERT and FASTEX scores were 0.

Case 3 was a 9-year-old boy. He was diagnosed with FD as a result of NBS and GLA gene testing revealed the G43D variant. The initiation of ERT was scheduled once FD symptoms manifested. Mulberry bodies were noted on urinalysis prior to treatment initiation. ERT with agalsidase alpha was started at the age of 6 years. No clinical symptoms were observed before ERT; however, pain in the extremities developed during ERT. FASTEX scores increased from 0 to 5 before ERT for peripheral neuropathy. However, there was no further increase during ERT and, thus, he was judged to be clinically unchanged.

Cases 4 and 5, a 13-year-old boy and 12-year-old boy, were siblings. They were diagnosed as a result of NBS and GLA gene testing revealed the V199M variant. Renal biopsy identified zebra bodies in podocytes by electron microscopy (

Figure 1-C and 1-D) and ERT was started at the ages of 12 and 11 years. There were no clinical manifestations during ERT and FASTEX scores were 0.

4. Discussion

The present study examined the effectiveness of FASTEX for evaluating pediatric FD treated with ERT. The obtained results showed that scores did not increase in heterozygous FD females (cases 1 and 2) or late-onset FD males (cases 4 and 5). Although the male with classical-type FD (case 3) developed neuropathic pain during ERT, he was judged to be clinically unchanged based on his FASTEX scores. These results suggest that FASTEX is inadequate for evaluating pediatric FD during ERT. FASTEX assesses neurological, cardiac, and renal symptoms [

7]; however, the clinical symptoms of pediatric FD include neuropathic pain and gastrointestinal dysfunction [

8,

9].

On the other hand, biomarkers associated with FD, such as Lyso-Gb3, which are considered to be diagnostically useful [

10], have been shown to rapidly decrease after the initiation of ERT [

11]. In addition, the formation of anti-drug antibodies to enzyme preparations adversely affects the decline in biomarkers [

11]. The positive rate of antidrug antibodies is as high as 57% in classical-type FD patients, and Lyso-Gb3 levels do not markedly decrease in antibody-positive patients, in contrast to antibody-negative patients [

12], suggesting that the monitoring of antidrug antibodies is also important for male patients with classical-type FD, such as case 3. Therefore, the measurement of biomarkers and anti-drug antibodies may be more useful for evaluating the treatment course of pediatric FD patients after the initiation of ERT than FASTEX scoring. However, these measurements are not currently covered by the national health insurance system in Japan.

In addition, FD has variable symptoms and is a progressive disease [

13]. Organ damage may be irreversible if treatment is delayed [

14]. A previous study reported that the duration of time between the onset and diagnosis of FD ranged between 25 and 36 years, with FD being diagnosed in patients in their 40s, even though it develops in teenagers [

15]. Some regions in Japan have begun to detect FD through NBS and, thus, the number of pediatric FD patients is expected to increase in the future. The guidelines for FD suggest the initiation of ERT for males with classical-type FD who develop pain in the extremities and late-onset FD males and heterozygous FD females with organ damage [

1,

16]. However, in the future, FD patients identified in NBS may begin ERT before symptoms develop.

Based on the present results, FASTEX evaluations of asymptomatic FD patients detected in NBS and receiving ERT may be insufficient. New methods, such as biomarkers and pediatric-specific scoring, need to be developed for the management of FD from childhood when clinical symptoms are less likely to appear.

5. Conclusions

FASTEX is a good tool for evaluating FD, but may be insufficient for assessing treatment effects in pediatric FD cases. New evaluation methods for pediatric cases are required, particularly those identified in NBS.

Author Contributions

Nobuhiko KOGA: Writing – original draft. Takahito INOUE: Writing – original draft. Noriko UESUGI; Investigation; review and editing. Shinichiro NAGAMITSU: Investigation; review and editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its retrospective nature using existing medical records with no additional intervention or patient contact required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all patients involved in the study to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Germain DP. Fabry disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010; 5: 30.

- Ramaswami U. Fabry disease in children and response to enzyme replacement therapy: results from the Fabry Outcome Survey. Clin Genet. 2012: 81: 485–490. [CrossRef]

- Sawada T. Newborn screening for Fabry disease in the western region of Japan. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2020; 22: 100562. [CrossRef]

- Inoue T. Newborn screening for Fabry disease in Japan: prevalence and genotypes of Fabry disease in a pilot study. J Hum Genet. 2013; 58: 548–552. [CrossRef]

- Whybra C. The Mainz Severity Score Index: a new instrument for quantifying the Anderson-Fabry disease phenotype, and the response of patients to enzyme replacement therapy. Clin Genet. 2004; 65: 299-307. [CrossRef]

- Giannini EH. A validated disease severity scoring system for Fabry disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2010; 99: 283-290. [CrossRef]

- Mignani R. FAbry STabilization indEX (FASTEX): an innovative tool for the assessment of clinical stabilization in Fabry disease. Clin Kidney J. 2016; 9: 739–747. [CrossRef]

- Laney DA. Fabry disease in infancy and early childhood: a systematic literature review. Genet Med. 2015; 17: 323-330. [CrossRef]

- Hopkin RJ. Characterization of Fabry Disease in 352 Pediatric Patients in the Fabry Registry. Pediatr Res. 2008; 64(5): 550-555. [CrossRef]

- Rombach SM. Plasma globotriaosylsphingosine: diagnostic value and relation to clinical manifestations of Fabry disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010; 1802(9): 741-748. [CrossRef]

- Sakuraba H. Plasma lyso-Gb3: a biomarker for monitoring fabry patients during enzyme replacement therapy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018; 22: 843-849. [CrossRef]

- Tsukimura T. Anti-drug antibody formation in Japanese Fabry patients following enzyme replacement therapy. Mol Genet Metab. 2020: 100650. [CrossRef]

- Eng CM. Fabry disease: baseline medical characteristics of a cohort of 1765 males and females in the Fabry Registry. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007; 30: 184-192. [CrossRef]

- Van der Veen SJ. Early start of enzyme replacement therapy in pediatric male patients with classical Fabry disease is associated with attenuated disease progression. Mol Genet Metab. 2022: 163-169. [CrossRef]

- Paim-Marques L. Frequency of Fabry disease in a juvenile idiopathic arthritis cohort. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2021:12; 19(1):91. [CrossRef]

- Okuyama T. Practical guideline for the management of Fabry disease 2020. 1st ed.: Diagnosis and Treatment. 2020. [in Japanese].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).