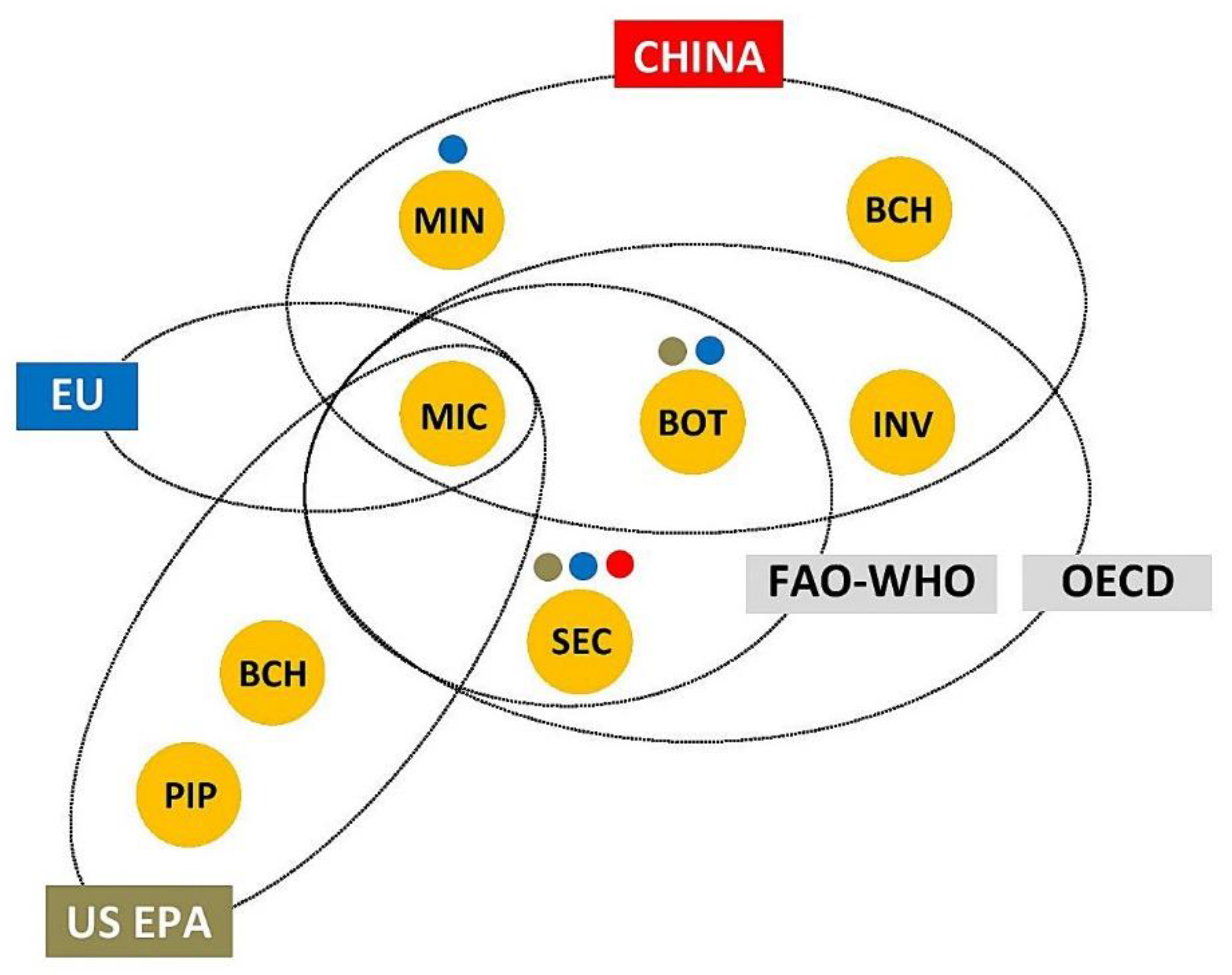

1. Introduction

Crop plants are threatened by a variety of pests, harmful organisms that reduce their productivity, such as animal pests (insects, mites, nematodes, molluscs and some vertebrates), microbial plant pathogens (bacteria, fungi, viruses), and weeds [

1]. Considering that crop losses due to the pests can be substantial (higher than 80% in some crops) pest control measures are required. The use of synthetic chemical pesticides for this purpose has increased dramatically since the mid-20

th century. The application of synthetic pesticides improved crop yield and quality, boosted food security and increased farmers' income [

2,

3]. On the other hand, the widespreadl adoption of synthetics has also led to negative outcomes such as development of pest resistance to pesticides, adverse effects on beneficial and non-target organisms, environmental contamination and increased risks to human health [

4,

5].

Growing public demands for environmentally-friendly, safe and sustainable crop pest management, along with increasingly stringent pesticide regulatory requirements has boosted the interest for pesticides of biological origin – biopesticides - as an alternative to synthetic chemicals [

6,

7,

8]. Biopesticides are not a novelty in pest control and crop protection. Several plant-based products (e.g. nicotine, pyrethrum, rotenone) were commercialized for use against animal pests in Western Europe and the United States during the 19

th and early 20

th centuries [

9,

10]. After the World War II development of biopesticides continued, albeit in the shadow of a large-scale production and use of synthetic chemical pesticides. The most important commercialized biopesticides included the products based on the entomopathogenic bacterium

Bacillus thuringiensis Berliner, fermentation products from soil actinomycetes, mycopesticides based on the entomopathogenic fungi

Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo) Vuillemin and

Metarhizium anisopliae (Metschnikoff), as well as azadirachtin and other plant-based products derived from the neem tree (

Azadirachta indica A. Juss). Despite ongoing development, biopesticides had a minor role in crop protection. However, since the late 20

th anderaly 21

th centuries, the biopesticide sector has experienced faster growth in the global market, compared to the sector of synthetic pesticides [

6,

7,

11].

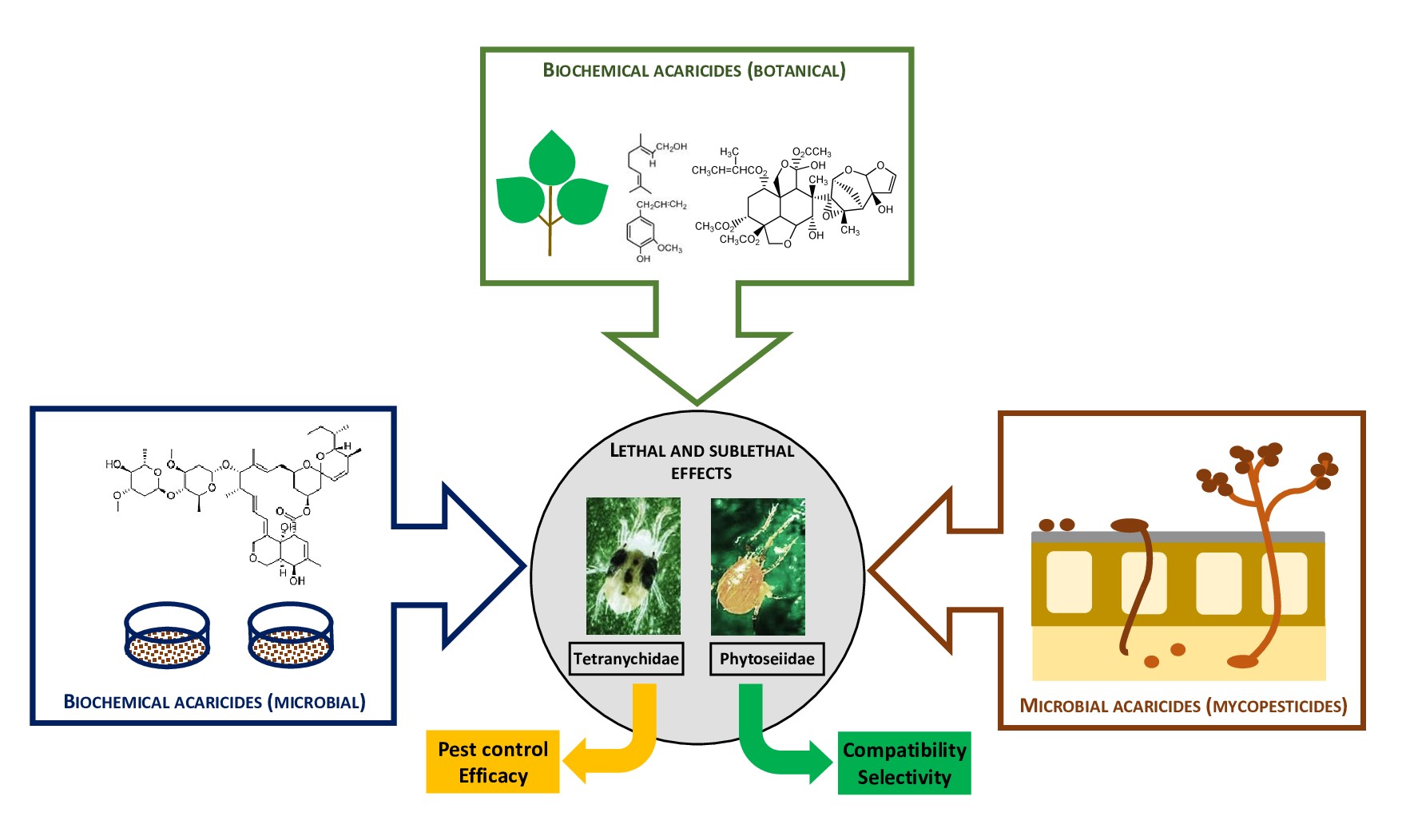

The family of spider mites (Tetranychidae) includes several major pests of crop plants, which the most important being the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch, the citrus red mite, Panonychus citri (McGregor), and the European red mite, Panonychus ulmi (Koch). Economically important pests are also found in other mite families, such as Eriophyidae [citrus rust mite, Phyllocoptruta oleivora (Ashmead), and coconut mite, Aceria guerreronis Kiefer], Tarsonemidae [broad mite, Polyphagotarsonemus latus (Banks), and cyclamen mite, Phytonemus pallidus (Banks)], and Tenuipalpidae (flat mites, Brevipalpus spp).

Acaricides, pesticide products used against plant-feeding mites, remain a vital component of integrated pest management (IPM) programs in crop protection. It should be noted that a considerable number of active substances used against mites are actually insecto-acaricides, i.e. their spectra of toxic activity include both insects and mites. This overlap occurs because these substances typically act on molecular target sites common to both insects and mites [

12,

13,

14,

15]. In this review we use the term acaricide to refer to all pesticides intended to control mites, regardless of whether they are also labeled for insect control. In the context of IPM, the crucial point is acaricide selectivity i.e. their compatibility with natural enemies (predatory mites and insects) used as biological control agents (BCA) of tetranychid and other plant-feeding mites. Among contemporary acaricides there are not so many products of biological origin. Considering recent trends in global pesticide market, however, an increase in the number of acaricidal products of biological origin (bioacaricides) could be expected. This review will focus on properties and effects of contemporary bioacaricide products intended for use in crop protection. To do the review on bioacaricides, however, we first need to clarify what we actually talk about when we talk about biopesticides in the modern world?

4. Side Effects of Bioacaricides on Predatory Mites

The IPM paradigm in crop protection defines pesticide selectivity as compatibility of pesticides with natural enemies of plant-feeding pests, and it is based on evaluation of detrimental effects of pesticides on natural enemies as the BCAs of the pests [

121]. The most important BCAs of spider mites and other plant-feeding mites, as well as some insect pests (whiteflies, thrips) are predatory mites of the family Phytoseiidae. Among more than 30 commercialized phytoseiids, the major species are

Amblyseius swirskii Athias-Henriot,

Neoseiulus californicus (Garman),

Neoseiulus cucumeris (Oudemans) and

Phytoseiulus persimilis Athias-Henriot, which account for 60% of the global market [

122]. The selectivity of pesticides with the BCA has two aspects. Physiological selectivity is based on toxicokinetic and toxicodynamic mechanisms that ensure a lower sensitivity of the BCAs compared to harmful species. Ecological selectivity is the result of limiting the exposure of the BCA to pesticides in time and space [

121,

123].

Various methods have been used for the evaluation of pesticide selectivity. Since the 1970s the Working Group (WG) “Pesticides and Beneficial Organisms” of the International Organization for Biological Control – Western Palearctic Regional Section (IOBC-WPRS) has developed standardized methods for over 30 beneficial species, natural enemies of insect and mite crop pests, and has tested nearly 400 pesticides [

124,

125]. The IOBC methods constitute a programme for sequential testing of pesticide effects on beneficials in which the decision to perform field trials depends on the outcome of laboratory bioassays. A harmless classification implies that further testing is not necessary i.e. pesticide is considered compatible [

126,

127]. Initial toxicity bioassay is carried out on glass plates where the most susceptible life stage is exposed to fresh deposite of pesticides applied at the highest recommended rates (the “worst case” scenario). The other laboratory bioassays include modification such as exposure of less susceptible stages on leaves or leaf discs (extended laboratory bioassay), exposure to field aged pesticide residues (persistence bioassay) [

124,

128].

In the laboratory bioassays, the IOBC ranking for classifying harmfulness is based on reduction in beneficial capacity, as a consequence of mortality and reduced fecundity. It is expressed by the coefficient of toxicity or the total effect (

E, %), calculated using the formula:

E = 100% - (100% - M) ×

R, where

M is the percentage of mortality corrected for mortality in the control, and

R is the ratio between the number of eggs produced by treated females and the number of eggs produced by females in the control [

129]. Instead of the number of eggs laid (fecundity), in some studies [

130,

131,

132] the number of hatched eggs (fertility) was recorded.

The IOBC ranking includes four categories, based on the values of

E (%): 1 = harmless (

E < 30%), 2 = slightly harmful (

E = 30-80%), 3 = moderately harmful (

E = 80-99%), and 4 = harmful (E > 99%). If a pesticide is classified in categories 2-4, further testing in semi-field and field trials is necessary. To calculate

E in these trials the effects of pesticides on population size and dynamics are recorded, and a pesticide is considered harmless (

E < 25%) slightly harmful (

E = 25-50%), moderately harmful (

E = 50-75%), and harmful (

E > 75%) [

128].

The IOBC-WPRS database on effects of plant protection products on beneficial arthropods (set up in the early 2000s, currently under revision) compiled data concerning the compatibility of pesticides and beneficials, published in scientific journals and proceedings of the WG conferences, as well as in the reports on regulatory testing in the European Union. The database includes 1768 test results on the selectivity of 379 pesticides to 16 phytoseiid species [

125,

133]. Acaricides are represented with 567 results for 98 compounds. Besides acaricides, other pesticides have also been evaluated, including 143 herbicides and 111 fungicides, as well as 27 insecticides. With 346 tested pesticides (76% of total results and 60% of acaricide results) the species

Typhlodromus pyri Scheuten stands out among phytoseiids (followed by

P. persimilis,

Amblyseius andersoni (Chant) and

Euseius finlandicus (Oudemans). The predominance of

T. pyri is mainly a consequence of its status as an indicator species since over 86% of the results originate from reports on the regulatory testing of pesticides in European Union [

133].

The database contains test results of 11 bioacaricides and 10 phytoseiid mites with a total of 65 results (55 from laboratory bioassays and 10 from field trials), 69% of which are for

T. pyri. Among bioacaricides, more than a half of the results refer to abamectin, spinosad and

B. bassiana (

Table 3a). In laboratory bioassays abamectin was shown mostly to be moderately harmful to harmful, with the expected variation in results depending on predator species and/or abamectin concentrations. The persistence bioassay showed that compatibility could be achieved by exposure of

N. californicus to residues aged at least 15 days. In field trials abamectin was slightly harmful to

A. swirskii and harmless to

T. pyri. Spinosad results were similar to abamectin results, while

B. bassiana was slightly harmful or harmless to

T. pyri and other phytoseiids (

Table 3b).

Most of the data on compatibility of acaricides with phytoseiid mites have not come from the IOBC-WPRS database. A number of papers were not included in the database because they used methods that more or less deviate from the standard characteristics [

124,

125]. The experimental design of many other studies, carried out almost exclusively on leaves or leaf discs, have included new species of phytoseiid mites, different developmental stages, a greater number of acaricide concentrations, new ways of exposure and new toxicity parameters and endpoints [

123,

134]. Concentrations lower than the recommended ones have also been tested, and some of the studies have been carried out to estimate LC

50 and the other LCs. In addition to mortality for eggs, juveniles and/or adults, many studies include assessment of sublethal effects of pesticides on developmental time, fecundity, fertility, and other life history traits of phytoseiid mites. Different ways of exposure to pesticides have been applied in the bioassays individually or in combinations, such as triple exposure: a combination of direct treatment, residual exposure and feeding of predators with treated prey. Some studies also included evaluation of comparative toxicity predator-prey [

130,

135,

136,

137,

138]. In addition to the total effect and the IOBC classification of toxicity, new parameters and criteria for compatibility evaluation were introduced. Beers & Schmidt [

139] and Schmidt-Jeffris & Beers [

140] proposed that the effect of acaricides is expressed by calculating the cumulative effect on the survival of treated females, their fecundity and fertility (egg hatching), as well as on the survival of hatched larvae. For predator-prey comparisons, the selectivity index is calculated as the difference between the cumulative effects of acaricides on predator and prey.

Recently, the evaluation of compatibility of pesticides with phytoseiid mites has increasingly been based on laboratory bioassays that estimate their effect at the population level. In the demographic bioassay the effect is expressed by a change in the value of the intrinsic rate of population increase (

rm) as a consequence of the pesticide impact on developmental time, fecundity, longevity and other life history traits of the mites. The demographic bioassay is based on construction of the life table from data on survival and reproduction. Two types of the life table have been used: the female fertility life table, constructed from data on female survival and fertility (production of female offspring) [

141,

142] and the age-stage two-sex life table, which includes juvenile development and survival data for both sexes, and female fecundity [

143].

Examples of the aforementioned studies are presented in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7. Most of the results of these studies refer to abamectin, spinosad and azadirachtin. In addition to the four major commercialized species of global importance (

A. swirskii, N. californicus, N. cucumeris and

P. persimilis) these studies have included the other important phytoseiid species, such as

Galendromus occidentalis (Nesbitt),

Neoseiulus womersleyi (Schicha),

Phytoseiulus macropilis (Banks) and

Phytoseiulus longipes Evans. Both commercialized and native strains have been evaluated. Mycopesticides based on

B. bassiana and

H. thompsonii were mostly compatible with phytoseiids (

Table 4).

Table 4.

Examples of evaluation of the compatibility of microbial bioacaricides (mycopesticides) and phytoseiid mites in various laboratory bioassays; Comp = compatibility conclusion: + positive (compatible); - negative (not compatible).

Table 4.

Examples of evaluation of the compatibility of microbial bioacaricides (mycopesticides) and phytoseiid mites in various laboratory bioassays; Comp = compatibility conclusion: + positive (compatible); - negative (not compatible).

| Mycopesticides |

Phytoseiid mites |

|

Methodology |

Comp |

References |

| |

Exposure |

Endpoints |

|

Beauveria bassiana GHA |

Amblyseius swirskii |

c |

rc; Td-re |

Sf, Fec, Fer |

+ |

[144] |

|

|

Beauveria bassiana ATCC 74040 |

Neoseiulus californicus |

n |

rc; Td-re |

Se, Sf, Fec, Fer, E ● |

- |

[130] |

|

| |

Phytoseiulus persimilis |

n |

rc; Td-re |

Se, Sf, Fec, Fer, E ● |

+ |

[132] |

|

| Hirsutella thompsonii |

Phytoseiulus longipes |

n |

rc; Td-re |

Sf, Fec, Fer, E, IOBC

|

+ |

[145] |

|

| |

|

|

rc; Tre (4-31) |

|

+ Tre (10) |

|

|

Abamectin and milbemectin proved to be not compatible after direct treatment followed by residual exposure and consumption of treated prey. Abamectin was considered compatible mostly when predatory mites were exposed to its aged residues. This is an example of ecological selectivity that can be achieved by temporal separation between acaricides and phytoseiids [

123]. Spinosad results were variable; similar to abamectin, its low persistence allowed ecological compatibility (

Table 5). Azadirachtin was shown to be compatible with phytoseiids, regardless of the route of exposure, while pyrethrum was not compatible after direct treatment and residual exposure. Similar to abamectin and spinosad, low persistence of oxymatrine allowed its compatibility (

Table 6). In research that includes LC

50 as one of the bioassay endpoints [

137,

146,

147] conclusions were made based on the comparison of the LC

50 values with the recommended concentrations.

Table 5.

Examples of evaluation of the compatibility of microbial biochemical acaricides and phytoseiid mites in various laboratory bioassays; Comp = compatibility conclusion: + positive (compatible); - negative (not compatible); → further research needed .

Table 5.

Examples of evaluation of the compatibility of microbial biochemical acaricides and phytoseiid mites in various laboratory bioassays; Comp = compatibility conclusion: + positive (compatible); - negative (not compatible); → further research needed .

| Bioacaricides |

Phytoseiid mites |

|

Methodology |

Comp |

References |

| |

Exposure |

Endpoints |

| abamectin |

Amblyseius swirskii |

n |

rc, rc+/-; Td-re |

Se, Sl, Sf, Fec, LC50

|

→ |

[146] |

| |

Euseius scutalis |

n |

rc, rc+/-; Td-re |

Se, Sl, Sf, Fec, LC50

|

→ |

[147] |

| |

Galendromus occidentalis |

c |

rc; Tre (3-37) |

Sf, Fec, Fer, E, IOBC

|

+ Tre (6) |

[148] |

| |

Neoseiulus barkeri |

c |

rc, rc+/-; Tre (0) |

Sf, Fec, Fer, LC50, E, IOBC ● |

+ |

[149] |

| |

Neoseiulus californicus |

c |

rc; Tre (0-21) |

Sf |

+ Tre (7) |

[150] |

| |

|

n |

rc; Tre (0-21) |

Sf ● |

+ Tre (7) |

[151] |

| |

|

c |

rc; Td-re + Tp |

Sf, Fec, Fer, SI ● |

- |

[138] |

| |

Neoseiulus cucumeris |

n |

rc, rc+/-; Tre (0) |

Sf, LC50 ● |

+ |

[152] |

| |

|

c |

rc; Tre (0) |

Sf |

- |

[153] |

| |

Neoseiulus fallacis |

c |

rc; Td-re + Tp |

Sf, Fec, Fer, SI ● |

- |

[138] |

| |

Phytoseiulus longipes |

n |

rc; Td-re |

Sf, Fec, Fer, E, IOBC

|

- |

[145] |

| |

|

|

rc; Tre (4-31) |

|

+ Tre (10) |

|

| |

Phytoseiulus persimilis |

c |

rc; Tre (3-37) |

Sf, Fec, Fer, E, IOBC

|

+ Tre (14) |

[148] |

| |

|

n |

rc; Td-re |

Sf, Fec, Fer, E, IOBC

|

- |

[131] |

| |

|

c |

rc; Tre (0-21) |

Sf |

+ Tre (14) |

[150] |

| |

|

c |

rc; Td-re + Tp |

Sf, Fec, Fer, SI ● |

- |

[138] |

| milbemectin |

Neoseiulus womersleyi |

n |

rc; Td-re |

Sel-a, Sf, Fec ● |

- |

[154] |

| |

Phytoseiulus persimilis |

n |

rc; Td-re |

Sel-a, Sf, Fec ● |

- |

[155] |

| spinosad |

Amblyseius swirskii |

n |

rc, rc+/-; Td-re |

Se, Sl, Sf, Fec, LC50

|

- |

[156] |

| |

Galendromus occidentalis |

n |

rc; Td-re + Tp |

Se, Sf, Fec |

+ |

[136] |

| |

Kampimodromus aberrans |

n |

rc; Tre (0) |

Sf, Fec, Fer, E

|

- |

[157] |

| |

Neoseiulus cucumeris |

c |

rc; Tre (0-6) + Tp |

Sf, IOBC

|

+ Tre (4) |

[158] |

| |

Neoseiulus fallacis |

n |

rc, rc+/-; Td-re + Tp |

Se, Sf, Fec, LC50

|

→ |

[137] |

| |

|

n |

rc; Tre (0), Tp |

Sel-a, Sf, Fec |

- |

[159] |

| |

Phytoseiulus persimilis |

n |

rc; Td-re |

Sf, Fec, Fer, E, IOBC

|

+ |

[131] |

| |

Typhlodromus montdorensis |

c |

rc; Tre (0-6) + Tp |

Sf, IOBC

|

+ Tre (5) |

[158] |

Table 6.

Examples of evaluation of the compatibility of botanical biochemical acaricides and phytoseiid mites in various laboratory bioassays; Comp = compatibility conclusion: + positive (compatible); - negative (not compatible).

Table 6.

Examples of evaluation of the compatibility of botanical biochemical acaricides and phytoseiid mites in various laboratory bioassays; Comp = compatibility conclusion: + positive (compatible); - negative (not compatible).

| Bioacaricides |

Phytoseiid mites |

|

Methodology |

Comp |

References |

| |

Exposure |

Endpoints |

| azadirachtin |

Amblyseius andersoni |

n |

rc, Td-re |

Sf, Fec, E

|

+ |

[160] |

| |

Neoseiulus barkeri |

c |

rc, Tre (0) |

Sf, Fec, Fer, E, IOBC

|

+ |

[149] |

| |

Neoseiulus californicus |

n |

rc; Td-re |

Se, Sf, Fec, Fer, E ● |

+ |

[130] |

| |

|

c |

rc; Td-re |

Sf, Fec, Fer |

+ |

[161] |

| |

Neoseiulus cucumeris |

c |

rc; Td, Tre (0) + Tp |

Sel-a, Sf, Fec |

+ |

[162] |

| |

Phytoseiulus longipes |

n |

rc; Td-re |

Sf, Fec, Fer, E, IOBC

|

+ |

[145] |

| |

|

|

rc; Tre (4-31) |

|

+ Tre (4) |

|

| |

Phytoseiulus macropilis |

c |

rc; Td-re |

Sf, Fec, Fer |

+ |

[161] |

| |

Phytoseiulus persimilis |

c |

rc; Td, Tre (0) + Tp |

Sel-a, Sf, Fec |

+ |

[149] |

| |

|

n |

rc; Td-re |

Se, Sf, Fec, Fer, E ● |

+ |

[132] |

| oxymatrine |

Phytoseiulus longipes |

n |

rc; Td-re |

Sf, Fec, Fer, E, IOBC

|

- |

[145] |

| |

|

|

rc; Tre (4-31) |

|

+ Tre (10) |

|

| pyrethrum |

Amblyseius andersoni |

n |

rc, Td-re |

Se, Sf, Fec, E

|

- |

[160] |

| |

Neoseiulus californicus |

n |

rc; Td-re |

Se, Sf, Fec, Fer, E ● |

- |

[130] |

| |

Phytoseiulus persimilis |

n |

rc; Td-re |

Se, Sf, Fec, Fer, E ● |

- |

[132] |

| rosemary oil |

Phytoseiulus persimilis |

c |

rc, rc+/-; Td-re, Tre (0) |

Sf, LC50 ● |

+ |

[107] |

| soybean oil |

|

n |

rc; Td-re |

Se, Sf ● |

+ |

[135] |

| + fatty acids |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| + caraway oil |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Investigation of the comparative toxicity to predators and their prey has an important place in this evaluation of the selectivity of bioacaricides. This type of investigation is the basis for assessing physiological selectivity [

123]. The lower comparative toxicity to phytoseiids, however, does not itself ensure compatibility. If the bioacaricide significantly reduces the prey population, the lack of food can cause decline and disappearance of the predator population and followed by an outbreak of the prey population [

163]. Also, the consequences of approximately equal harmfulness of the recommended concentrations for predator and prey should be interpreted depending on the level of harmful effect of a bioacaricide. Bergeron & Schmidt-Jeffris [

138], for example, calculated abamectin selectivity indices for

N. fallacis,

N. californicus and

P. persimilis to be zero. These values resulted from approximately equal but high harmfulness (96 - 100%) for both predators and their prey (

T. urticae), so this bioacaricide is not rated as compatible. The predator-prey comparison using LC

50 as the endpoint requires additional interpretation of the results, because significantly lower toxicity for the predator compared to the prey has practical significance if the LC

50 for the predator is higher than the recommended concentration [

152]. When investigating physiological selectivity, the phenomenon of acaricide resistance should be taken into account as well [

123]. Regarding bioacaricides, the only example is resistance to abamectin and milbemectin, widespread in

T. urticae populations [

164] and also observed in other tetranychids [

165,

166].

Evaluations using demographic bioassays (

Table 7) showed that the recommended concentrations of several tested bioacaricides reduce population growth of phytoseiid mites. Lower concentrations can also cause reduction, as shown by the treatment of

Phytoseius plumifer (Canestrini & Fanzago) with abamectin applied at LC

20 against adult females [

167]. On the other hand, the finding that low concentrations do not cause reduction [

168,

169] should be interpreted bearing in mind the recommended concentrations. Comparative demographic studies would allow a deeper insight, but there have been no examples of such research with bioacaricides.

Table 7.

Examples of evaluation of the compatibility of bioacaricides and phytoseiid mites in demographic bioassays (rm = the intrinsic rate of increase: ↓ = reduction, ns = non significant effect).

Table 7.

Examples of evaluation of the compatibility of bioacaricides and phytoseiid mites in demographic bioassays (rm = the intrinsic rate of increase: ↓ = reduction, ns = non significant effect).

| Bioacaricides |

Phytoseiid mites |

|

Methodology |

Effect on rm

|

References |

|

Beauveria bassiana GHA |

Phytoseiulus persimilis |

c |

rc, ATlt, F0

|

↓ |

[170] |

| Hirsutella thompsonii |

Phytoseiulus longipes |

n |

rc, ATlt, F0

|

↓ |

[145] |

| abamectin |

Phytoseiulus longipes |

n |

rc, ATlt, F0

|

↓ |

[145] |

| |

Neoseiulus baraki |

n |

rc, Flt, F0 F1 |

↓ F0

|

[171] |

| |

Phytoseius plumifer |

n |

LC10, 20, Flt, F1

|

↓ LC20

|

[167] |

| milbemectin |

Amblyseius swirskii |

n |

LC5, 15, 25, ATlt, F1

|

ns |

[169] |

| azadirachtin |

Neoseiulus baraki |

n |

rc, Flt, F0 F1

|

ns |

[171] |

| |

Phytoseiulus longipes |

n |

rc, ATlt, F0

|

↓ |

[145] |

| geraniol + citronellol |

Neoseiulus californicus |

c |

LC10, 20, ATlt, F1

|

ns |

[168] |

| + nerolidol + farnesol |

|

|

|

|

|

| oxymatrine |

Phytoseiulus longipes |

n |

rc, ATlt, F0

|

↓ |

[145] |

An alternative and less labour- and time-consuming approach for assessing effects at the population level is based on the calculation of the instantaneous rate rate of increase (

ri) from the number of live individuals at the beginning and the end of bioassay [

172]. Using this approach Tsolakis & Ragusa [

135] compared the effects of a commercial mixture of vegetable and essential oils and potassium salts of fatty acids on population growth of

T. urticae and

P. persimilis; the biopesticide significantly reduced the

ri values of the former but not of the latter species. Lima et al. [

173] observed significant reduction of the

ri values following treatment of

Neoseiulus baraki (Athias-Henriot) with abamectin, while Silva et al. [

149] found no reduction in

Neoseiulus barkeri Hughes treated with abamectin and azadirachtin.

The aforementioned examples show that life history traits have been in the focus of evaluation of sublethal effects of bioacaricides on phytoseiids. Few studies have been focused on evaluation of behavioral effects. Lima et al. [

174] investigated repellence (avoiding acaricide without making direct contact with its residues) and irritancy (moving away from the treated area after making the contact) of azadirachtin for

N. baraki and found significant effects. The authors emphasized that these effects on walking behavior potentially reduce the exposure of predators, but also can cause their dispersal and decrease the efficiency of biological control. On the other hand, Bostanian et al. [

136] and Beers & Schmidt-Jeffris [

175] observed low level of repellency of spinosad on

G. occidentalis. Bioacaricides can also affect feeding and reproduction behavior of phytoseiid mites. Investigations of the effects on

N. baraki revealed that azadirachtin impaired copulation [

176] and abamectin lowered the attack rate [

177], while both bioacaricides impaired prey location [

178]. These effects hinder predator-prey interaction and can compromise biological control.

The largest amount of data on the effects of acaricides on phytoseiids comes from laboratory bioassays. Therefore, the extrapolation of the results from laboratory to field is of fundamentally important, especially for the IOBC-WPRS programme for sequential testing. Translating laboratory results to field conditions has been a major challenge considering that laboratory bioassays most often do not take into account complexity and variability of environmental factors, heterogeneity of spray coverage in time and space, indirect effects through food supply, population dynamics [

123,

179]. In addition to these general limitations, the IOBC-WPRS testing has been critically discussed regarding the realism of the “worst case” scenario, and a rigid implementation of the trigger values for toxicity classification, which may affect accuracy of predictions drawn from the laboratory bioassay alone [

180,

181,

182]. Methodological issues aside, the usefulness of the IOBC database is limited by the need to evaluate compatibility of pesticides (acaricides) with predatory species and strains important in local environments [

123,

179,

182].

Investigating compatibility in greenhouse and/or field trials is necessary, not only because of the problems that arise when extrapolating results from the laboratory. The compatibility of acaricides with phytoseiids should be tested and proven under realistic conditions of the complex action of various factors. Large-scale field trials enable an assessment of the long-term impact of operational factors (timing, procedures and amounts of acaricide application, predator augmentation, habitat management measures) and biological-ecological factors (trophic relationships and interactions, migrations, host plant features, refugia) on the dynamics of predator and prey populations and the effectiveness of biological control under variable environmental conditions. On the other hand, the complexity and variability of factors in the field can make it difficult to interpret the results and draw clear conclusions [

123,

180,

182].

There have been not many examples of studies evaluating the compatibility of bioacaricides and phytoseiids in greenhouse and/or field trials. In some of these studies, the dynamics of both predator and prey populations was monitored in order to explore possibility of combining predator activity and bioacaricide application. Greenhouse trials showed that mycopesticides could be successfully applied against

T. urticae in combination with

P. persimilis release on tomato plants [

75] and

N. californicus release on rose plants [

183], as well as against mixed infestation of chrysanthemums with

T. urticae and the western flower thrips,

Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande), in combination with

A. swirskii and

N. cucumeris [

184]. Also, spinosad application at rates recommended for thrips control was compatible with

P. persimilis release against

T. urticae on ivy geranium [

185]. On the other hand, application of spinosad in an apple orchard was detrimental to

Kampimodromus aberrans (Oudemans), a predator of

P. ulmi [

157].

In other studies only the predator population was monitored. Jacas Miret and Garcia-Mari [

186] rated abamectin as moderately harmful and azadirachtin as harmless to

Euseius stipulatus (Athias-Henriot) following treatments in a citrus orchard. Castagnoli et al. [

160] conducted field trials in an apple orchard in which azadirachtin and pyrethrum were applied twice on a bi-weekly basis. Azadirachtin did not affect population of

A. andersoni; pyrethrum significantly reduced the population density after the second treatment, but the population recovered in a few days. Miles and Dutton [

187] investigated the effects of single and repeated applications of spinosad on phytoseiid populations in vines and apples. Maximum reduction of 43% and 21% was found in

T. pyri and

K. aberrans populations in vines, respectively, and 41% in

A. andersoni population in apples, after single treatment of spinosad. Repeated application caused maximum reduction of 75% in

A. andersoni population in apples, and this effect was rated as harmful. On the other hand, de Andrade et al. [

115] found no significant population reduction in

Iphiseoides zuluagai Denmark & Muma (a predator of the citrus leprosis mite,

Brevipalpus yothersi Baker) treated with oxymatrine in a commercial citrus grove.

Considering the advantages and limitations of different types of bioassays, a complementary approach to the evaluation of selectivity [

123,

160,

180], which integrates laboratory and field data, is needed as a sustainable solution for exploiting physiological and/or ensuring ecological selectivity. This integrative approach implies more further research in the IPM context, on an expanded range of evaluated bioacaricides and phytoseiid species and strains, both commercialized and native.