1. Introduction

The application of neural network approximation in management science and economics is now gaining popularity and becoming widely accepted as an estimation methodology with a predictive edge in out of sample forecasting. The importance of more accurate forecasting for better decision making in economics and management science cannot be overstated, particularly given the volatility in emerging markets and the recent financial crisis of 2007 - 2008, widely considered by many economists to have been the most serious financial crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The large advances in data-driven modelling techniques, such as applications built on machine learning, which combine elements from computational statistics, mathematical optimization, pattern recognition, predictive analytics and artificial intelligence are transforming everyday life. Intuitively, the movements of the macro-economy, which central banks are particularly interested in (Bank of England 2024), must be the outcome of microeconomic decisions and interactions. In this paper we introduce the practical aspects of machine intelligence and how new developments in predictive modelling and machine learning, that analyze current and historical facts to make predictions about future values can guide decision-making for central bankers, monetary policymakers, economics and management science more widely.

It is a commonly held belief among macroeconomists that there exists a long-run relationship between the growth rate of the money supply and the growth rate of prices, i.e., inflation. This belief forms the foundation for monetary policymaking at the world's central banks, and hence is extraordinarily important for the conduct of public policy. Its importance makes it one of the most tested hypotheses in economics. Yet, the mechanism through which money affects an economy's overall, average price level, is necessarily complex - as complex as the economies themselves. The mechanism almost surely is not linear, and the short-run dynamics may disguise the long-run relationship, complicating statistical tests of the relationship. Linkages need not be univariate, and fluctuations in other variables, including the growth rate of productivity, and international economic conditions, may affect the near- and medium-term correspondence between money growth and inflation. Such interactions raise the possibility that the correspondence may be both nonlinear and time-varying, perhaps with complexity beyond capture in parametric frameworks. Bachmeier et al. (2007), for example, soundly rejects both linear autoregressive univariate, and vector-autoregressive multivariate models. This current study explores the proposition that there exists a dynamic, long-run relationship between the money supply and increases in prices. In addition to the economic analysis, our study contributes to the operational researchers’ long-standing interest in nonparametric methods with potentially unbounded degrees of input memory, namely, the artificial intelligence method of neural networks. In general, artificial intelligence is a consortium of data-driven methodologies which include artificial neural networks, genetic algorithms, fuzzy logic, probabilistic belief networks and machine learning as its components. We have witnessed a phenomenal impact of this data-driven consortium of methodologies in many areas of study, the economic and management fields being no exception; see for example, Dia (2001), Binner et al. (2004a, b), Zhang and Qi (2005), Bodyanskiy and Popov (2006), Curry (2007) and Cao (2012). The main reason for the large growth in the popularity in the application of this class of nonlinear models is the persistent failure of linear models to capture non-linear dynamic relationships embedded in real world data. Thus, we derive forecasts of the US price level using this powerful nonlinear method, largely unexploited in this problem domain.

A standard result of most textbook macroeconomic models which include money and prices is that changes in the money supply lead, eventually, to proportionate changes in the price level. Friedman and Schwartz (1970) present an analysis of the correlation between US money and prices over a span of more than a hundred years to provide a simple approach to monetary policy - stabilization of the growth of the money stock at a low level, whilst Barnett (1997) paints a very clear picture of the monetarist stance in the States in the early 1980s in his description of the “broken road”. Forecasts showed that the rise in growth of M2 from under 10% to over 30% between late 1982 and early 1983 was bound to result in renewed stagflation, i.e. recession accompanied by high interest rates and rising inflation. Evidence from Nelson (2003) argues that both the mean and the dynamics of inflation in present-day models are governed by money growth. Since January 2012, monetary policy has played a more formal role in determining the US inflation rate over the longer run, and hence the Federal Open Market Committee can specify a longer-run target for inflation, see

http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20120125c.htm for further details on the US monetary policy mandate. Maintaining inflation at the rate of 2 percent is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve's statutory mandate. Communicating this inflation goal clearly to the public helps keep longer-term inflation expectations firmly anchored, thereby fostering price stability and moderate long-term interest rates and enhancing the Monetary Policy Committee's ability to promote maximum employment in the face of significant economic disturbances.

Standard econometric methodology using traditional cointegration techniques to investigate the long run relationship between money supply and the price level has yielded a vast literature of empirical evidence. However, McCallum (1993) demonstrates that a cointegrating relationship may not be found, even if one does exist, if there are any improvements in the payment’s technology over time. To overcome this limitation, as outlined above, we advocate the artificial intelligence technique of artificial neural networks (ANN) as our preferred alternative approach because, theoretically, ANNs should be able to model nonstationary processes without requiring any preliminary transformation, although practically, pre-processing to reduce nonstationarity improves performance, see, e.g., Virili and Freisleben, 2000; Curry, 2007 and an interesting discussion on nonstationarity in Giles et al (2001). In essence, this approach to modelling helps to define the parameter space in a framework similar to a regime switching model where the regimes themselves are nonlinear relationships.

The purpose of this study is to contrast the performance of macroeconomic forecasts using artificial neural networks to those made by the methods using human judgement that we represent by the Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF). The SPF is the oldest quarterly survey of macroeconomic forecasts in the United States. The survey began in 1968 and was conducted by the American Statistical Association and the National Bureau of Economic Research. The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia took over the survey in 1990. The Survey of Professional Forecasters' official web page offers the actual releases, documentation, mean and median forecasts of all the respondents as well as the individual responses from each economist; the latter are kept confidential with the use of identification numbers.

We assess the performance of a recurrent neural network (RNN) equipped with a multi-staged memory mechanism in forecasting US inflation using data spanning January 1970 to May 2024. The research focuses on addressing the question: Can an RNN forecast inflation turning points—periods where a shift in policy stance is required—more accurately than conventional methods? Specifically, we aim to determine whether critical predictive signals embedded in historical data can enable the model to identify these turning points with greater precision. To test this, the RNN is trained and validated on data from January 1970 to December 2022. After the training phase, the model’s parameters are frozen, and it is tasked with producing rolling forecasts for the out-of-sample test period spanning January 2023 to May 2024. The RNN generates step-ahead forecasts from t+1 to t+15 as the forecast progresses through the out-of-sample period, offering insights into both short-term and medium-term inflation dynamics during potential turning points.

2. The US Data and Forecasting Framework

We begin with an overview of the data.

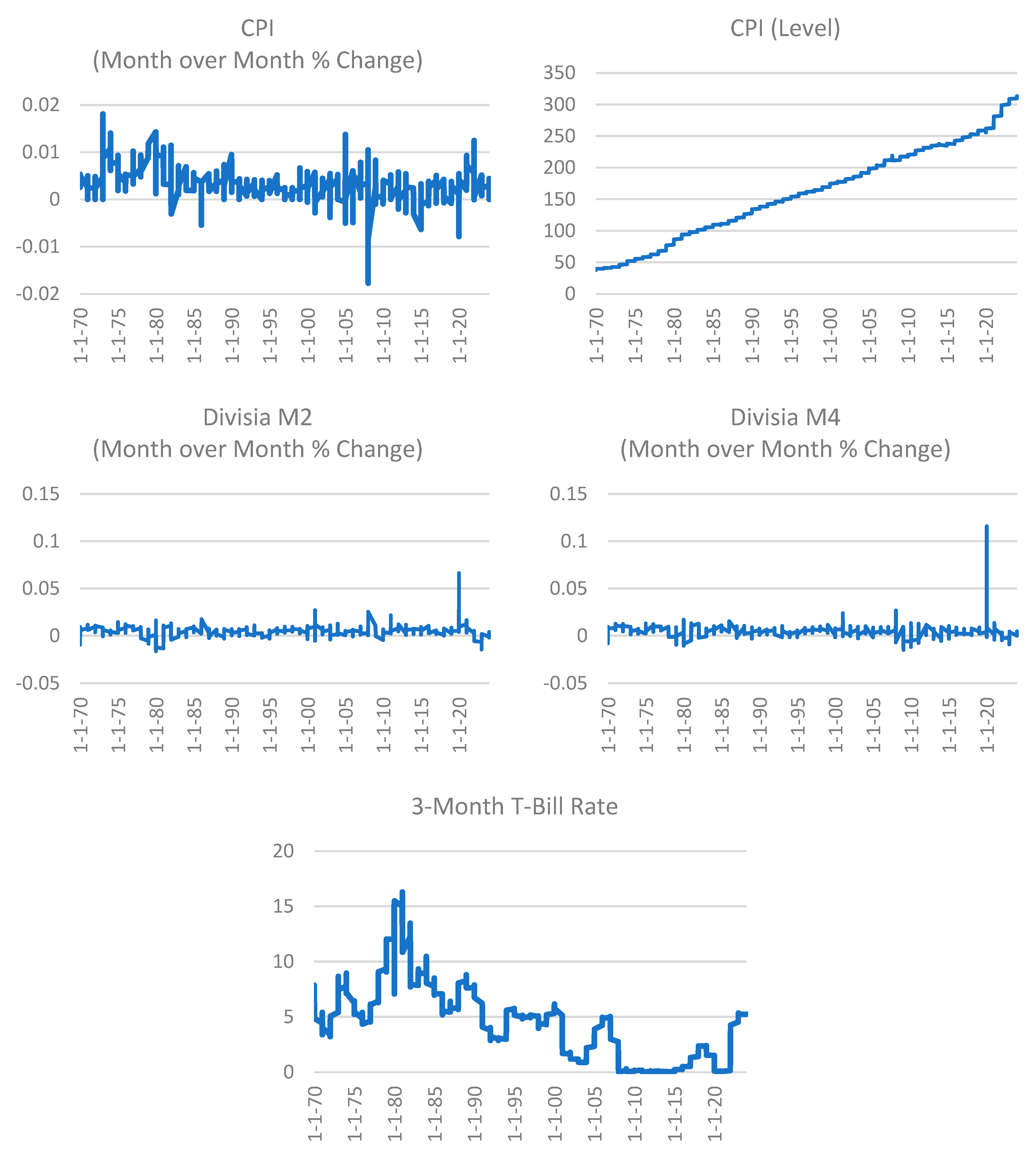

Figure 1 shows the month over month percentage change and level of the US consumer price index (CPI), the month over month percentage change US monetary aggregate Divisia M4 (DM4) and Divisia M2 (DM2), as well as the 3-month T-Bill Rate. Divisia M4 is a broad money measure published by the Center for Financial Stability, CFS, New York, and now widely accepted in central banking circles.

1 Divisia M2 use applies the same Divsia monetary aggregation method to monetary assets include in the US Federal Reserve’s M2 definition.

In 2021, Dixon outlined a simple method for predicting inflation in the short-run, using the simple arithmetic of annual inflation: the level of “headline” annual inflation

equals the sum of the most recent twelve-months month-on-month (mom) inflation

:

This is an approximation which ignores the compounding of inflation but is accurate given that mom inflation is small, i.e. the average over 1993-2024 is 0.17% per month. The change in inflation each month is then simply:

New inflation “drops in” and the old inflation “drops out”. Thus, for the 12 months for t=1…12, we know exactly what will be dropping “out” of the headline, because it has already happened (which is why we did not put the expectation on this term). Hence, we know half the story of inflation for the next year, because it has already happened. The task for predicting the headline inflation over the next twelve months thus reduces to predicting the “other half”, the new mom inflation over those months.

3. The Multi-Recurrent Network Methodology

Machine learning techniques are concerned with general pattern recognition or the construction of universal function approximators, Cybenko (1989) that can detect relations in the data in situations where no obvious patterns exist. The power of neural network approximations is summarized in the well-known theorem of Hornik et al. (1989) that says, essentially, a neural network can approximate all probability density functions supported compactly on the real numbers. In view of Dorsey’s (Dorsey, 2000, pp 30 - 31) contention that standard econometric methods have provided no concrete evidence one way or the other to explain the link between money growth and rate of growth of prices, inflation, in an early application for the USA which examined these key macroeconomic indicators; we believe neural networks offer more promise in the context of econometric modelling than standard linear models. In essence, this approach to modelling helps to define the parameter space in a framework akin to a regime-switching model where the regimes themselves are nonlinear relationships. This is an unusual tool in this context, although the application of neural networks in the field of economics and finance is growing in popularity, as indicated by the diverse range of applications surveyed in Binner et al. (2004a, b, 2005, 2010, 2018, 2025, forthcoming). A key limitation of the traditional neural network models used for modelling inflation used by Gazely and Binner (2000), Dorsey (2000) and Binner et al. (2005) for modelling inflation, is that they are based on the feed-forward multilayered perceptron (FF-MLP) trained with standard backpropagation (Rumelhart et al 1986). Although the limitations of the backpropagation algorithm are well-publicized, it is the feed forward nature of the architecture that restricts the types and robustness of temporal dependencies that can be learned and represented by these models. Typically, historical input information has to be provided in the form of a temporal input window, which must be pre-determined, e.g., a six-month input window would require the previous six-monthly values for each explanatory variable to be made available to enable the target variable to predict at the required forecast horizon. Determining the optimum input window size must be empirically established and the forward-only flow of information further restricts these models to acting as non-linear auto-regressive (NLAR) models. If either a moving average component or previous output behavior is essential to the task being learned, then more complex architectures are required that incorporate some form of feedback in the connections between neurons. Hence, we build upon our previous successes (Kelly et al. 2024; Tepper et al 2016; Orojo et al (2019, 2023)) with a subset of RNNs referred to as multi-recurrent networks (MRNs), see Ulbricht (1994) and Dorffner (1996).

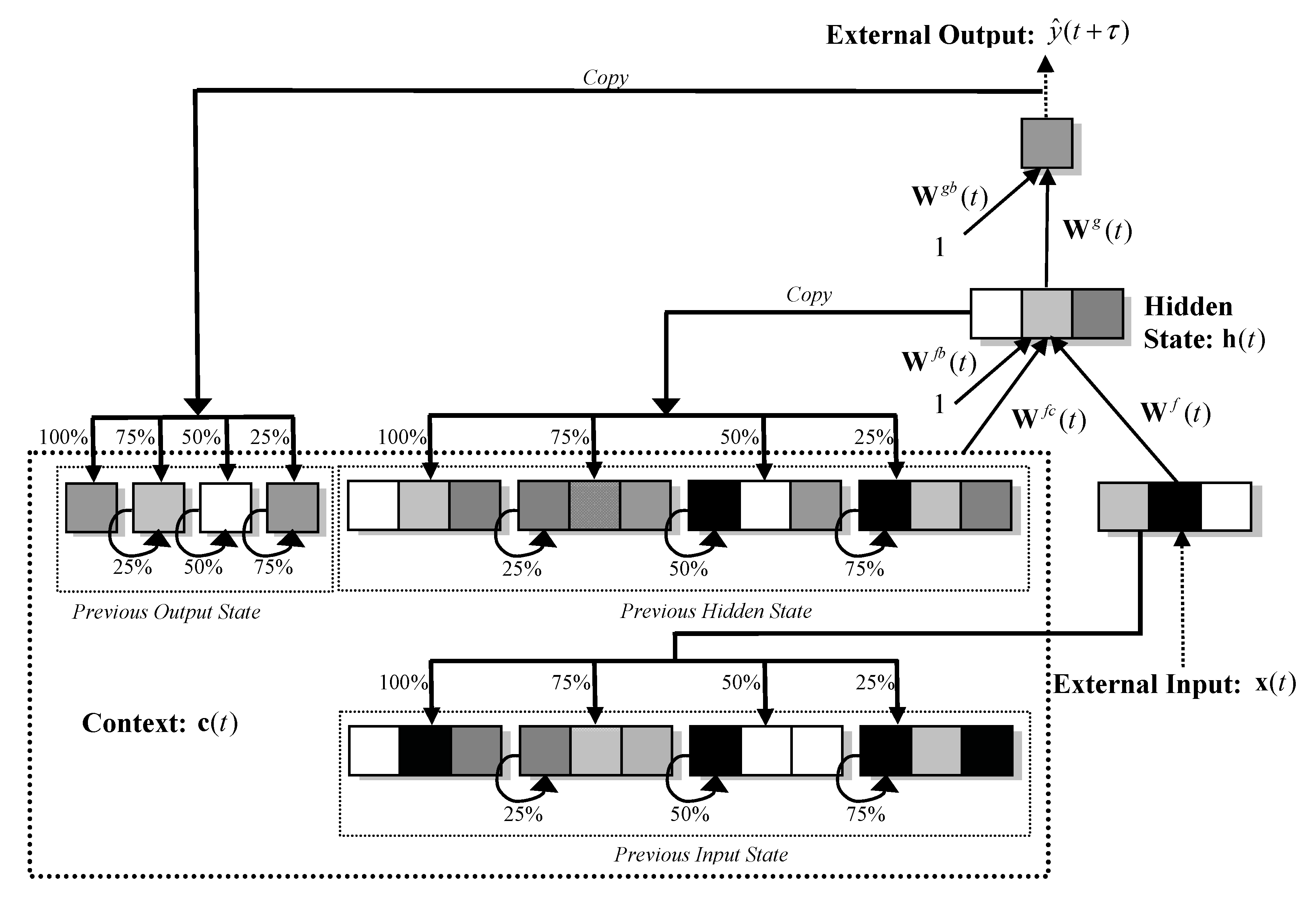

3.1. The Multi-Recurrent Network (MRN)

This class of RNN extends the traditional FF-MLP architecture to include recurrent connections that allow network activations to feedback as inputs to units within the same or preceding layer(s). Such internal memories enable the RNN to construct dynamic internal representations of temporal order and dependencies which may exist within the data. Units that receive feedback values are often referred to as context or state units. Also, assuming non-linear activation functions are used, the universal function approximation properties of FF-MLPs naturally extends to RNNs. These properties have led to wide appeal of RNNs for modelling time-series data, Ulbricht (1994); Moshiri, et al. (1999); Tenti (1996); Tino et al (2001); Binner et al. (2004a, b); Binner et al (2010), Cao et al (2012) and Tepper et al. (2016).

The MRN architecture is shown in

Figure 1 and can be expressed generally as:

where

denotes the

predicted month-on-month percentage change in inflation for a particular forecast horizon,

, where we explore horizons τ=1 to 16. As described in

Section 2 and later in this Section, the external input vector

x consists of between two to five input variables representing combinations of: the previous month-on-month percentage change in inflation, natural log of the price level, 3-month treasury bill secondary market rate, and month-on-month growth rates (%) for DM2 or DM4.

c (the context vector) forms a complex internal memory state vector that is the concatenation of the: previous hidden state vector (

h; previous output vector (

and the previous external input vector, (

x. We extend each allowable feedback by additional banks of context units (memory banks) on the input layer. The number of additional memory banks relates directly to the degree of granularity at which past and current information is integrated and stored and enables the network to implement a form of sluggish state-based memory to inform decision making over variable-width time delays. Following Ulbricht (1994), Binner et al (2010), Tepper et al (2016) and Orojo et al (2023), we use

memory banks where

as experience has shown that moving beyond this does not lead to enhanced performance for the problems addressed.

c represents an internal memory of varying rigidity; that is some context units will represent information from very recent time steps and thus change rapidly whilst others will represent information further back in time and change much more slowly. To achieve this, the unit values fed back from the hidden and output layers are combined, to varying degrees, with their respective context units,

, in the input layer (as determined by the weighting values applied to its recurrent links). The influence of the previous context unit values is determined by the weighting values applied to the self-recurrent links. When the weighting on the recurrent links is greater than those on the self-recurrent links then more flexible memories are formed storing more recent information at the expense of historical information stored in the context units. Conversely, if the weighting values on the self-recurrent links are greater than those on the layer recurrent links then more rigid memories are formed since more historical information is preserved in the context units at the expense of the more recent information being fed back from subsequent layers.

It is these layer- and self-recurrent link ratios that collectively implement a sluggish state memory whereby network outputs (or decisions) are based on variable integrations of recent and distant past unit activations from the input, hidden and output layers. This weighted integration of current and past information can be generally expressed as follows:

where

, refers to context unit

i at time

t;

denotes either an output activation, hidden unit activation or external input value at time

t-1;

refers to the connection strength of the recurrent link from

to

where

where

;

refers to context unit

i at time

t-1; and finally

refers to the connection strength of the self-recurrent link for

where

.

x is the external vector of input variables.

is the weight matrix connecting the external input vector to the hidden layer;

is the weight matrix connecting the context vector to the hidden layer;

is the weight matrix between a single constant input unit (equal to 1) and the hidden layer (representing the hidden threshold or bias term);

is the weight matrix connecting the hidden layer to the output layer and

is the weight matrix between a single constant unit (equal to 1) and the output layer (again representing the output threshold or bias term); The vector function

f and function

g return the activation vectors from the hidden and output layers, respectively. We apply the hyperbolic tangent function,

, to the inner products performed for

f to compute the hidden unit values as shown below for a single hidden unit,

:

where

The number of hidden units is a significant hyper-parameter for this model and is empirically. Finally, we apply the identity function,

, for the inner products performed for

g to compute the output unit values as shown below for a single output unit,

:

where

We use back propagation-through-time (BPTT), (Werbos, 1990; Williams and Peng, 1990), to minimize the following mean-squared-error (MSE) measure:

where

, refers to the number of input patterns and

, the number of output units. BPTT is an efficient gradient-descent learning algorithm for training RNNs where weight changes are determined by a sequence, or time-lag, of input observations rather than a single observation. Input data were scaled to zero mean and unit variance. To facilitate convergent learning, a linearly decaying learning rate and momentum schedule are used for all training experiments with an initial learning rate of

0.0001 and momentum term of

0.95. This provides an effective time varying learning rate that guarantees convergence of stochastic approximation algorithms and has proven effective for temporal domains, for example, see Lawrence et al. (2000). To minimize the onset of over-fitting, in addition to the ensemble-based methodology discussed later, we apply L2 weight regularization during training with the lambda constant set at

0.001. We generate independent training sequences directly from the time-series using a time window, whose lag size is empirically established (120 months for the US inflation problem tackled here). The MRN context units are initialized to known values at the beginning of each sequence of data and each element within a sequence is processed sequentially by the network. Although this restricts the MRN to behave as a finite memory model and means that the MRN must first learn to ignore the first context values of each sequence, it allows for efficient randomized learning.

Although such RNNs and variants thereof have enjoyed some success for the time-series problem domains we tread with cautious optimism. Due to the additional recurrency, such models inherently contain large degrees of freedom (weights) which may require many training cases to constrain. Also, gradient descent-based learning algorithms are notoriously difficult at finding the optimum solution the architecture is theoretically capable of representing: Bengio et al. (1994) and Sharkey, et al. (2000). However, the embedded memory architecture within the MRN may compensate for this deficiency, as demonstrated recently by Tepper et al. (2016) and more recently by Orojo et al (2023). For a comprehensive account of the strengths and limitations of both feedforward and recurrent neural networks and how to optimize them, please see the classic textbook by Goodfellow et al (2016).

Figure 2.

Multi-recurrent Network Architecture.

Figure 2.

Multi-recurrent Network Architecture.

3.2. The MRN Forecasting Methodology

Based on the feature set used, we construct the following three types of MRN:

- (a)

simple MRN consisting of three input variables: the month-on-month percentage change in inflation (cpi_percmom, the auto-regressive term), the natural log of the price level (ln_cpi_level) and 3-Month Treasury Bill Secondary Market Rate (dtb3)

- (b)

intermediate MRN which includes a) plus the month-on-month growth rate (%) for the Divisia monetary measure DM4 (dm4_percmom)

- (c)

complex MRN which includes b) plus the month-on-month growth rate (%) for the Divisia monetary measure DM2 (dm2_percmom)

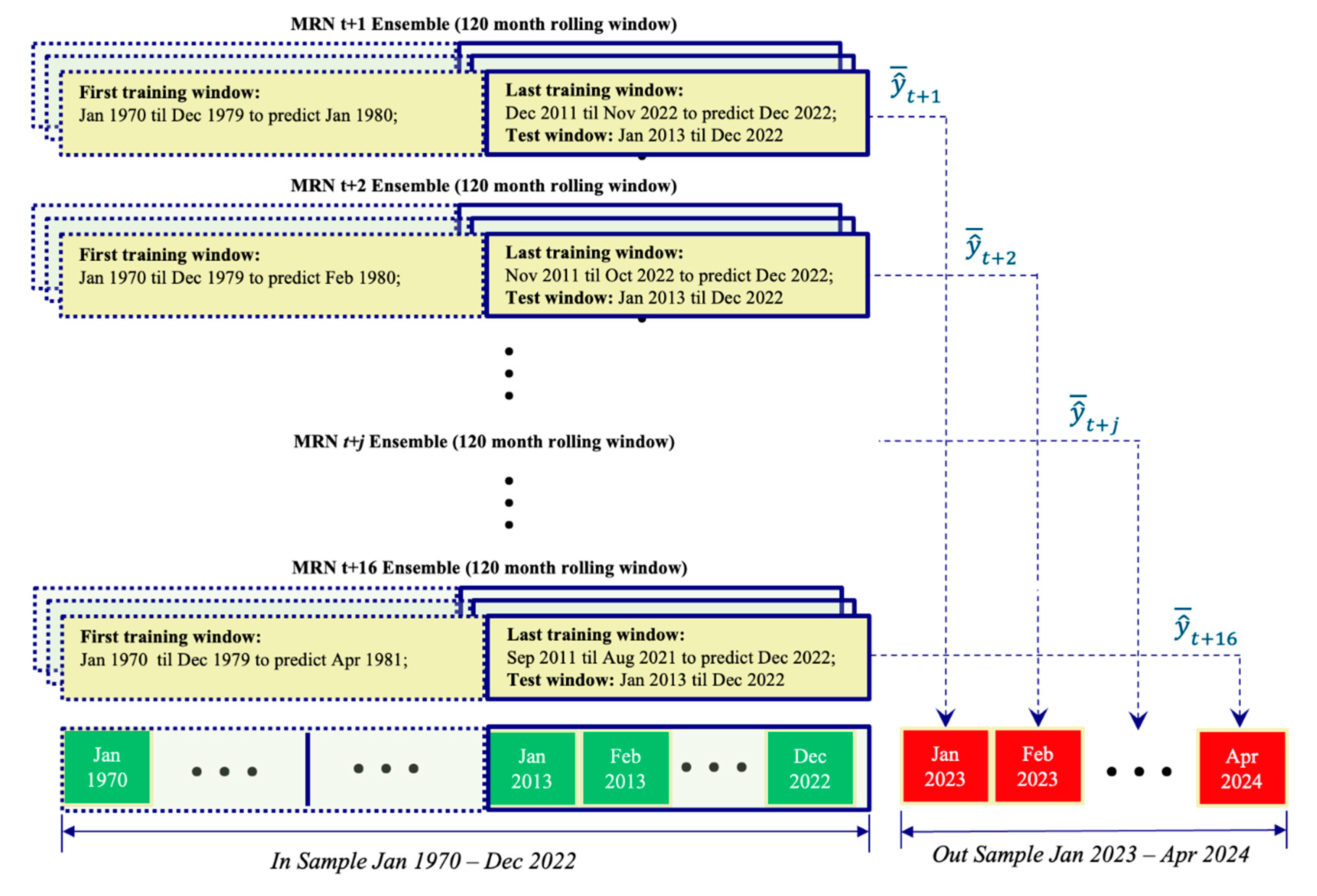

For each of the above feature sets, we develop a set of sixteen MRN ensembles where each MRN has a monthly input lag structure spanning 10 years; a single hidden layer with 50 non-linear units and is assigned to predict a particular forecast horizon of the month-on-month percentage change in inflation (i.e. t+1, t+2,…, or t+16). Each ensemble consists of five independently trained MRNs fitted to the in-sample period of January 1970 – December 2022 and then evaluated on the out-sample period of January 2023 to April 2024 (thus a total of 80 MRNs were generated for each of the three feature sets). As mentioned earlier, a series of independent training sequences of 120 months are generated directly from the time-series and presented in a random fashion to each MRN during the training process, where the context units are initialized to some known value at the beginning of each sequence, and the forecast generated in response to the last observation in the training sequence being stored as the prediction for that particular sequence.

The out-sample forecast for each trained MRN is generated in response to being sequentially fed the first out-of-sample input window containing observations from January 2013 until December 2022. The MRNs trained to predict t+1 are responsible for the January 2023 forecast, the models trained to predict t+6 are responsible for June 2023 forecast and so on. Each prediction is an average of the respective five MRNs associated with the dedicated forecast horizon. During the out-sample period, no further parameter estimates are obviously allowed. As the sequential input window slides across time, only new input observations are passed through the network as they become available. This forecasting methodology is depicted in

Figure 4 below.

Figure 4.

Multi-recurrent Network Architecture.

Figure 4.

Multi-recurrent Network Architecture.

This is analogous to an SPF making long term forecasts at the end of December 2022 based only on rules they have derived from studying observations between January 1970 and December 2022.

4. Results

4.1. Forecast Evaluation Metrics

Forecast evaluation metrics are essential tools for assessing the accuracy and predictive value of different forecasting methods. Each metric provides a distinct perspective on forecast performance, allowing for a comprehensive comparison across models. Here are detailed descriptions of each metric used in this evaluation:

A higher Improvement score suggests a more effective forecast, with a maximum possible value of 1 indicating perfect improvement over the random walk.

4.2. Analysis of Forecast Evaluation Metrics Table

The table below compares five forecasting methods, i.e., simple MRN, intermediate MRN, complex MRN, average MRN, and SPF, across these evaluation metrics. The average MRN method demonstrates the lowest RMSE and MAE, signifying the smallest average forecast errors. It also achieves the lowest Theil’s U (0.104), which suggests that it closely aligns with actual values and performs significantly better than a random walk. The high Improvement score of 0.896 for average MRN reflects an almost 90% reduction in forecast error over the baseline, indicating a substantial predictive advantage.

The simple MRN model also performs well, with an Improvement score of 0.876 and a Theil’s U of 0.124, suggesting it is nearly as accurate as average MRN. Meanwhile, intermediate MRN and complex MRN exhibit slightly higher error metrics and Theil’s U values, indicating that these models are somewhat less accurate. The SPF model, while showing moderate performance, has a relatively higher Theil’s U of 0.152, suggesting its forecast accuracy is less favorable compared to average MRN and simple MRN. Overall, average MRN is the best-performing model in terms of accuracy and predictive value, with simple MRN following closely behind. These models demonstrate a significant improvement over the random walk, making them reliable choices for forecast applications.

Table 1.

Forecast Model Evaluation Statistics.

Table 1.

Forecast Model Evaluation Statistics.

| Forecast Method |

RMSE |

MAE |

Theil U Statistic |

Improvement over Random Walk |

|

simpleMRN

|

0.472 |

0.373 |

0.124 |

0.876 |

|

intermediateMRN

|

0.637 |

0.600 |

0.167 |

0.833 |

|

complexMRN

|

0.627 |

0.553 |

0.164 |

0.836 |

|

averageMRN

|

0.395 |

0.360 |

0.104 |

0.896 |

|

SPF

|

0.580 |

0.459 |

0.152 |

0.848 |

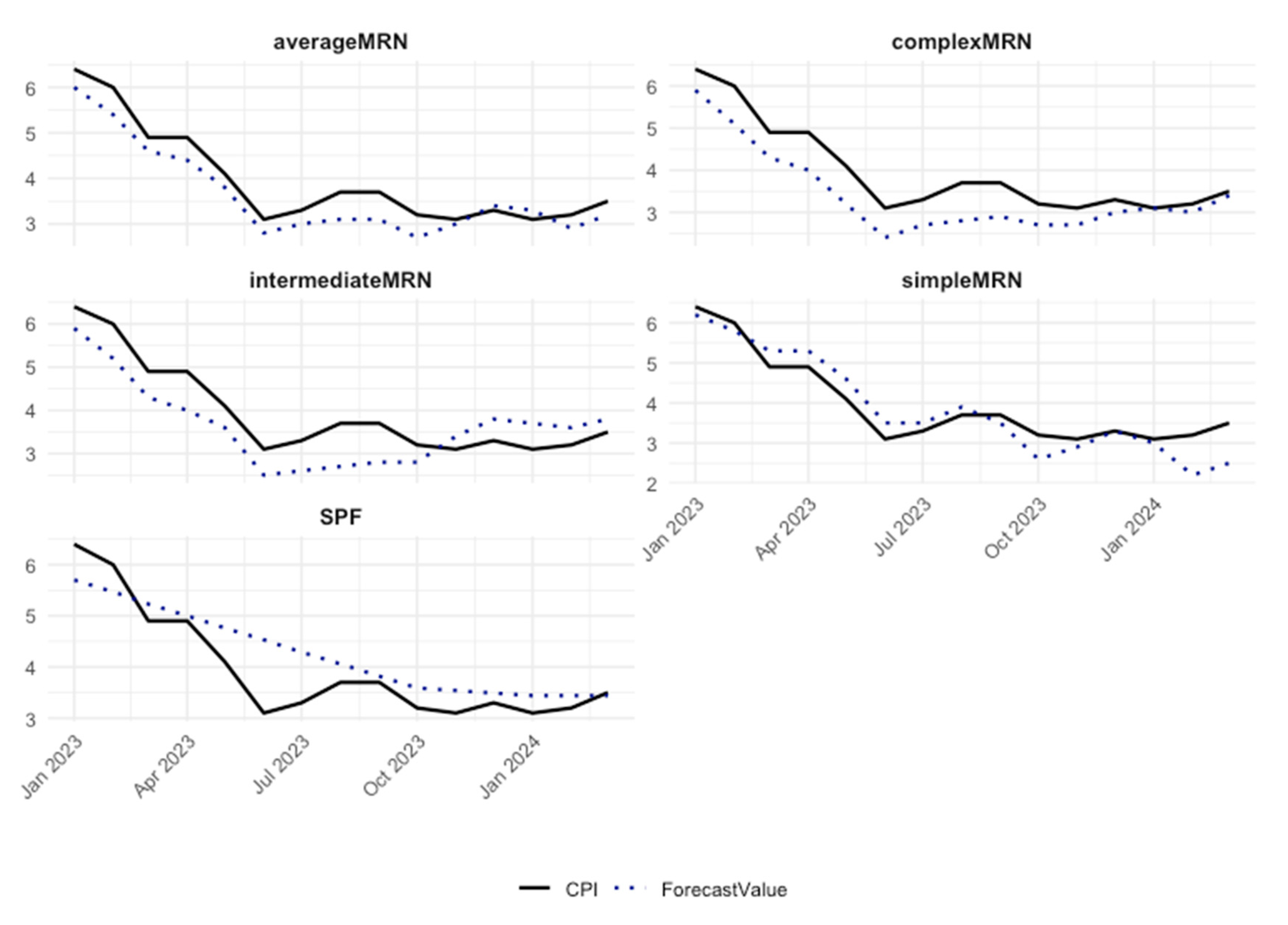

4.3. Comparison of CPI and Forecasts Over Time

Figure 3 plots a comparison of each forecasting model against the observed inflation rate over the test period. It is noteworthy that all MRN forecasts predict that inflation would return near to target level in May 2024 as opposed to the survey of professional forecasters’ prediction of October 2024. This is of policy relevance given that the Federal Reserve has come under criticism for waiting too long to lower key policy rates. The timing of the policy decision to adjust interest rates clearly matters and the timing of strategies to move quickly or slowly does have some important advantages and disadvantages, as explained by Kristin Forbes at a Bosten Federal Reserve Bank conference in 2023. Those central banks that acted more aggressively in interest rate setting after the pandemic in 2022, such as the US Federal Reserve, “hares” achieved both bigger reductions in inflation and less labour market pain. More aggressive action may have helped strengthen the central banks credibility, and thus made it less likely that inflation become entrenched. The alternative approach of responding slowly in interest rates increases, namely the “tortoise strategy” that is, “tighten a little, see how it's affecting the labor market, see how that's feeding through into inflation and then see if you need to do more, …….. allows entities to adjust and reduces the risk that something breaks.” Kristen Forbes, (2023).

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

This study highlights the potential of multi-recurrent networks (MRNs) in improving inflation forecasting, particularly during critical turning points where policy adjustments are necessary. By training and validating the MRNs on historical data spanning January 1970 to December 2022 and testing their performance on out-of-sample data from January 2023 to May 2024, we demonstrate their ability to forecast inflation dynamics with greater precision than conventional methods such as the Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF).

Our results indicate that MRNs, particularly the average MRN model, outperform both traditional methods and simpler neural network variants across key forecast evaluation metrics, including RMSE, MAE, and Theil’s U. The average MRN model not only achieves the most accurate forecasts but also predicts inflation turning points more effectively, enabling earlier detection of economic conditions requiring policy changes. Notably, MRNs forecasted inflation returning to target levels by May 2024, a substantially earlier timeline than SPF predictions, underscoring their relevance for real-time policy decision-making. Researchers who are trying to develop better models for forecasting the economy often use the SPF as a benchmark. If a researcher can build a model that forecasts better than the SPF, they would have made a major breakthrough, according to Croushore and Stark (2019). Evidence presented here does appear to show that it is possible to consistently outperform the SPF using a multi-recurrent neural network.

This research highlights the advantages of MRNs in capturing nonlinear, dynamic, and time-varying relationships in macroeconomic data, offering a robust alternative to traditional econometric models. By leveraging their ability to incorporate multi-staged memory mechanisms and long-term dependencies, MRNs demonstrate a predictive edge in identifying inflationary trends and turning points, critical for effective monetary policymaking.

So why is this important? Central Banks around the world need to put remedial measures in place at least 24 months ahead of any impending perturbation or significant deviation from policy targets. Given the time to adjust to policy, Central Banks and monetary policymakers need to have reliable early warning systems and forecasting methods available to prevent impending crises before they happen. Our class of neural networks provide clear evidence that turning points in US inflation can be predicted more effectively. We believe that the MRN is a powerful tool in this context. The MRN should form a part of any toolbox in the economics and management science profession where early warning signals are needed to detect and inform managers and policymakers of impending crises. The novelty of this work lies in the type of relationships that can be modelled, given the increasing quantity of granular micro and high frequency data that are available to economists and management scientists. Universal approximators at the heart of the artificial intelligence revolution, may be used to uncover nuanced relationships between variables and account for heterogeneity among agents. These tools may herald a new modelling paradigm at the micro and macro level as data driven approaches such as machine learning allow an inductive approach.

In conclusion, MRNs represent a significant advancement in the toolkit available to central banks and policymakers for economic forecasting. Their superior performance in predicting inflation turning points highlights their potential to inform timely and effective policy interventions, paving the way for more responsive and data-driven decision-making in the face of economic uncertainty. Future work could expand on these findings by exploring additional macroeconomic variables and integrating complementary machine learning approaches, such as ensemble models or hybrid techniques, to further enhance forecast accuracy. Moreover, extending the application of MRNs to different economic contexts and time horizons could provide deeper insights into their utility across various policy scenarios.

References

- Bachmeier, L., Leelahanon, S. and Li, Q. (2007) Money growth and inflation in the United States, Macroeconomic Dynamics 11, 113127.

- Bank of England (2024) One Bank Research Agenda, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/bank-of-england-agenda-for-research.

- Barnett, W.A., (1997) Which Road Leads to Stable Money, Economic Journal, pp. 1171-1185.

- In Barnett, W; How Faulty Monetary Statistics Undermine the Fed: A., (2012) Getting it Wrong; Barnett, W.A., (2012) Getting it Wrong: How Faulty Monetary Statistics Undermine the Fed, the Financial System and the Economy. Cambridge, MA. MIT Press.

- Belongia, M.T., (1996) Measurement Matters: Some Recent Results in Monetary Economics Re-Examined, Journal of Political Economy, pp. 1083-1065.

- In Belongia, M; Theory and Practice: T. and Binner J.M., Eds, (2000) Divisia monetary aggregates; Belongia, M.T. and Binner J.M., Eds, (2000) Divisia monetary aggregates: Theory and Practice, Palgrave MacMillan, ISBN, 0-333-64744-0.

- In Bengio, Y; 157-166: , Simard.P., Frasconi.P., (1994) Learning long-term dependencies with gradient descent is difficult, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 5 (2); Bengio, Y., Simard.P., Frasconi.P., (1994) Learning long-term dependencies with gradient descent is difficult, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 5 (2): 157-166.

- Binner, J.M., Bissoondeeal R.K., Valcarcel V. and Jones B.E., (2025, forthcoming) Identifying monetary policy shocks with Divisia mmoney in the United Kingdom, Macroeconomic Dynamics, forthcoming.

- Binner, J.M., Chaudhry S.M., Kelly L.J. and Swofford, J.L., (2018) Risky monetary aggregates for the USA and UK, Journal of International Money and Finance. 89, 127 – 138.

- In Binner J; comparative evidence from neural network and vector error-correction forecasting models. Contemporary Economic Policy, 22 (2): M., Gazely A.M., Chen S.H. and Chie, B.T., (2004a) Financial innovation and Divisia money in Taiwan; pp. 213–224. Binner J.M., Gazely A.M., Chen S.H. and Chie, B.T., (2004a) Financial innovation and Divisia money in Taiwan: comparative evidence from neural network and vector error-correction forecasting models. Contemporary Economic Policy, 22 (2), pp. 213-224. ISSN 1074-3529.

- In Binner J; 978-1-84950-303-7: M., Kendall, G. and Chen, S.H., (2004b) Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Economics and Finance, in Advances in Econometrics, 19, pp, 127 – 144. Thomas B. Fomby and R. Carter Hill Emerald Publishing, ISSN: 0731- 9053,, eISBN; ISBN 978-0-7623-1150-7. Binner J.M., Kendall, G. and Chen, S.H., (2004b) Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Economics and Finance, in Advances in Econometrics, 19, pp, 127 – 144. Thomas B. Fomby and R. Carter Hill Emerald Publishing, ISSN: 0731- 9053, ISBN 978-0-7623-1150-7, eISBN: 978-1-84950-303-7.

- Binner J.M., Bissoondeeal R.K., Elger T. and Mullineux A.W., (2005) A comparison of linear forecasting models and neural networks; an application to Euro inflation and Euro Divisia. Applied Economics, 37, 665-680.

- Binner J.M., Tino P, Tepper J.T., Anderson R.G., Jones B and Kendall G. (2010) Does money matter in inflation forecasting? Physica A, Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 389, 4793-4808. ISSN 0378-4371.

- Bodyanskiy Y. and Popov S., (2006), Neural network approach to forecasting of quasiperiodic financial time series, European Journal of Operational Research, 175, 1357 - 1366.

- Cao B., Ewing B.T., Thompson M.A., (2012) Forecasting wind speed with recurrent neural networks, European Journal of Operational Research, 221, 148-154.

- Croushore D. and Stark T., (2019) Fifty years of the professional forecasters, Federal Research Bank of Philadelphia Research Department.

- In Cybenko, G; 303 – 314: , (1989). Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoid function. Mathematics of Control, Signals and Systems, 2; Cybenko, G., (1989). Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoid function. Mathematics of Control, Signals and Systems, 2: 303 – 314.

- In Curry B; Some technical considerations: , (2007) Neural networks and seasonality; Curry B., (2007) Neural networks and seasonality: Some technical considerations. European Journal of Operational Research, 179, 267-274. ISSN 0377-2217.

- Darken, C. and Moody, J.E., (1991) Note on learning rate schedules for stochastic optimization. In R.P. Lippman, J.E., Moody, and D.S. Touretzky (Eds) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol 3, pp 832 – 838.

- Dia H., (2001) An object-oriented neural network approach to traffic forecasting, European Journal of Operational Research, 131, 253 – 261.

- Dixon H., (2021) The simple arithmetic of inflation. Using “drop-in” and “drop-out” for exploring future short-run inflation scenarios. Box A, pages 23-24, UK Economic Outlook – Summer 2021. NIESR.

- In Dorffner, G; 447-468: (1996) “Neural networks for time series processing,” Neural Network World 6 (4); Dorffner, G. (1996) “Neural networks for time series processing,” Neural Network World 6 (4):447-468.

- In Dorsey, R; Better Forecasts of Future Inflation? in Divisia Monetary Aggregates; Theory and Practice. Chapter 2: E., (2000), Neural Networks with Divisia Money; pp. 12–28. ISBN 0-333-64744-0. Dorsey, R. E., (2000), Neural Networks with Divisia Money: Better Forecasts of Future Inflation? in Divisia Monetary Aggregates; Theory and Practice. Chapter 2, pp 12-28. Eds. Belongia M.T. and Binner J.M., Palgrave Macmillan Press Ltd. ISBN 0-333-64744-0.

- In Elman, J; 179-211: , (1990), Finding structure in time, Cognitive Science 14; Elman, J., (1990), Finding structure in time, Cognitive Science 14: 179-211.

- In Friedman, M; Columbia University Press: and Schwartz, A.J., (1970) Monetary Statistics of the United States, New York; Friedman, M. and Schwartz, A.J., (1970) Monetary Statistics of the United States, New York: Columbia University Press.

- In Gazely A; Evidence from three countries: M. and Binner J.M., (2000), A neural network approach to the Divisia index debate; Gazely A.M. and Binner J.M., (2000), A neural network approach to the Divisia index debate: Evidence from three countries, Applied Economics, 32, 1607-1615.

- Giles C.L. Lawrence S., and Tsoi A.C., (2001), Noisy Time Series Prediction using a Recurrent Neural Network and Grammatical Inference. Machine Learning, Volume 44, Number 1/2, July/August, pp. 161–183.

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., and Courville, A., (2016). Deep Learning; Adaptive Computation and Machine Learning Series, MIT Press, London, Cambridge, Massachusetts, ISBN 978-0-262-035613.

- Hornik, K., Stinchcombe M., and H., (1989). Multi-layer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Networks, Vol 2, (5), 359-366.

- In Jordan, M; Concept-Learning, IEEE Press, Piscataway NJ: , (1986), Attractor dynamics and parallelism in a connectionist sequential machine, in: J. Diederich (Ed.), Artificial Neural Networks; p. 112. Jordan, M., (1986), Attractor dynamics and parallelism in a connectionist sequential machine, in: J. Diederich (Ed.), Artificial Neural Networks: Concept-Learning, IEEE Press, Piscataway NJ, 1990, pp. 112 - 127. Also, Proceedings of the 8th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 1986, pp. 531-545.

- Kelly L.J., Binner J.M., and Tepper J.A., Do monetary aggregates improve inflation forecasting in Switzerland? Journal of Management Policy and Practice, North American Business Press, April, 25[1], 124-133.

- Lawrence, S., Giles, C.L., Fong, S., (2000). Natural language grammatical inference with recurrent neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 12, 126 - 140.

- In McCallum, B; Some critical issues: T. (1993) Unit roots in macroeconomic time series; McCallum, B.T. (1993) Unit roots in macroeconomic time series: Some critical issues. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly, Vol. 79/2, Spring.

- Moshiri S., Cameron, N. and Scuse, D., (1999) Static, dynamic and hybrid ANN models in forecasting inflation, Computational Economics, 14, 219 – 235.

- Nelson, E., (2003) The future of monetary aggregates in monetary policy analysis, CEPR Discussion paper number 3897.

- Orojo, O., Tepper, J.A., Mcginnity, T. M., and Mahmud, M., (2019) A Multi-recurrent Network for Crude Oil Price Prediction Networks. 2019 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), 2019, pp. 2940-2945. [CrossRef]

- Orojo, O., Tepper, J.A., Mcginnity, T.M. and Mahmud, M., (2023). The Multi-Recurrent Neural Network for State-Of-The-Art Time-Series Processing. Procedia Computer Science. 222. 488 -498. [CrossRef]

- In Pearlmutter B; a survey: A., (1995) Gradient calculations for dynamic recurrent neural networks; Pearlmutter B.A., (1995) Gradient calculations for dynamic recurrent neural networks: a survey, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 6, 1212 – 1228.

- In Rumelhart D; Foundations: E., Hinton G.E., and Williams R.A., (1986) Learning internal representations by error propagation, in D.E. Rumelhart and J.L. McClelland, Eds, Parallel distributed processing: Explorations in the micro processing of cognition, Volume 1; p. 318. Rumelhart D.E., Hinton G.E., and Williams R.A., (1986) Learning internal representations by error propagation, in D.E. Rumelhart and J.L. McClelland, Eds, Parallel distributed processing: Explorations in the micro processing of cognition, Volume 1: Foundations, pp 318 – 362 Cambridge Massachusetts, MIT Press.

- Sharkey N., Sharkey A. and Jackson S., (2000) Are SRNs sufficient for modelling language acquisition? In P. Broeder and J.M.J. Murre Eds Models of language acquisition: inductive and deductive approaches pp 35 – 54, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- Sermpinis G., Konstantinos T., Andreas B., Karathanasopoulos C., Efstratios F. G. Dunis, C. (2013), Forecasting foreign exchange rates with adaptive neural networks, using radial-basis functions and Particle Swarm Optimization European Journal of Operational Research, 225, 528-540.

- Tenti P., (1996) Forecasting foreign exchange rates using recurrent neural networks, Applied Artificial Intelligence, 10, 567 – 581.

- Tepper, J.A., Shertil, M.S. and Powell H.M., (2016) On the importance of sluggish state memory for learning long term dependency, Knowledge Based Systems, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Tino, P., Horne, B.G., and Giles C.L., (2001), Attractive Periodic Sets in Discrete Time Recurrent Networks (with Emphasis on Fixed Point Stability and Bifurcations in Two–Neuron Networks), Neural Computation, 13(6), pp. 1379-1414.

- In Ulbricht, C; Proceedings of the Twelfth National Conference in Artificial Intelligence, AAAI Press/MIT Press, Cambridge, MA: (1994) “Multi-recurrent networks for traffic forecasting,” in; pp. 883–888. Ulbricht, C. (1994) “Multi-recurrent networks for traffic forecasting,” in: Proceedings of the Twelfth National Conference in Artificial Intelligence, AAAI Press/MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1994, pp. 883-888.

- Virili, F., & Freisleben, B., (2000). Nonstationarity and data preprocessing for neural network predictions of an economic time series. In Neural Networks, 2000. IJCNN 2000, Proceedings of the IEEE-INNS-ENNS International Joint Conference on (Vol. 5, pp. 129-134). IEEE.

- Werbos (1990), Backpropagation through time: what it does and how to do it, in Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 78, no. 10, pp. 1550-1560, Oct. 1990. [CrossRef]

- In Williams, R; 490–501: J., and Peng, J., (1990). An efficient gradient-based algorithm for on-line training of recurrent network trajectories. Neural computation, 2[4]; Williams, R. J., and Peng, J., (1990). An efficient gradient-based algorithm for on-line training of recurrent network trajectories. Neural computation, 2[4]:490–501, 1990. 19.

- Zhang G.P. and Qi M., (2005) Neural network forecasting for trend and seasonal time series, European Journal of Operational Research, 160, 501- 514.

Note

| 1 |

See Belongia and Binner (2000) for details on the construction and interpretation of evidence on the macroeconomic performance of Divisia monetary aggregates for eleven countries. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).