Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a central role in immune regulation and tolerance. The transcription factor FOXP3 is a master regulator of Tregs in both humans and mice. Mutations in FOXP3 lead to the development of IPEX syndrome in humans and the scurfy phenotype in mice, both of which are characterized by fatal systemic autoimmunity. Additionally, Treg dysfunction and FOXP3 expression instability have been implicated in non-genetic autoimmune diseases, including graft-versus-host disease, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis. Recent investigations have explored FOXP3 expression in allergic diseases, revealing Treg alterations in food allergies, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. This review examines the multifaceted roles of FOXP3 and Tregs in health and various pathological states including autoimmune disorders, allergic diseases, and cancer. Additionally, this review focuses on the impact of recent technological advancements in facilitating Treg-mediated cell and gene therapy approaches, including CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing. The critical function of FOXP3 in maintaining immune homeostasis and tolerance to both self-antigens and alloantigens has been emphasized. Considering the potential involvement of Tregs in allergic diseases, pharmacological interventions and cell-based immunomodulatory strategies may offer promising avenues for developing novel therapeutic approaches in this field.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

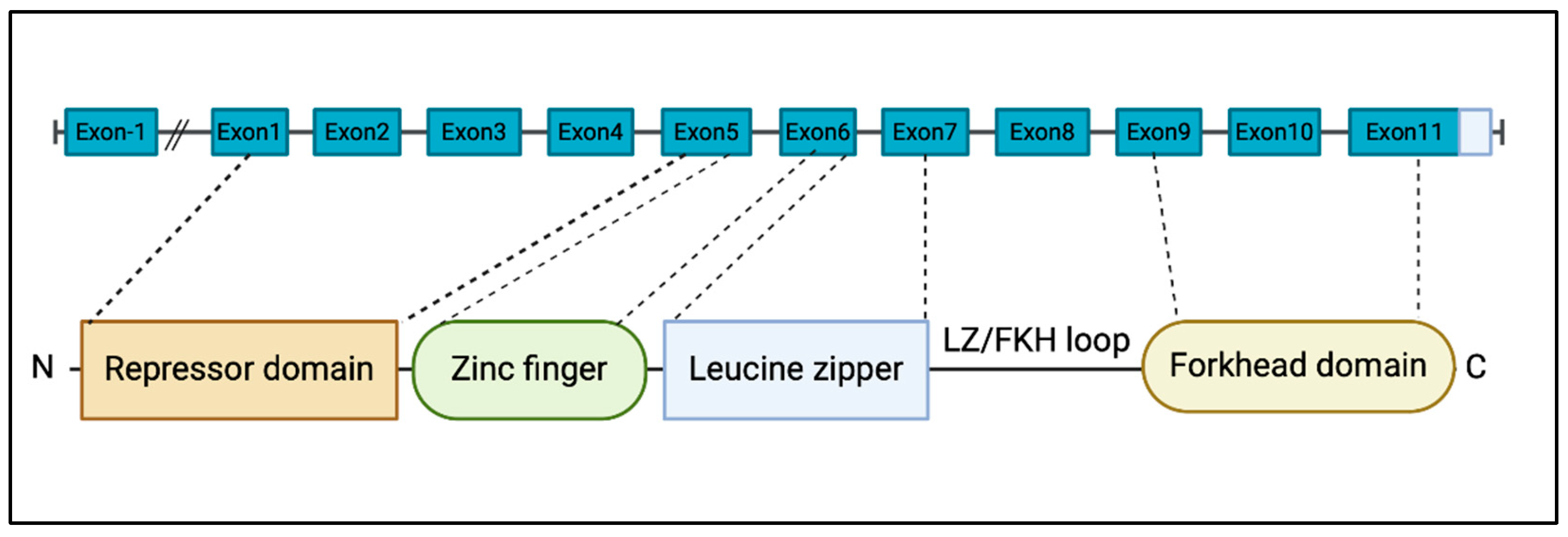

2. Molecular Features of FOXP3

3. FOXP3 expression in Tregs and Teffs

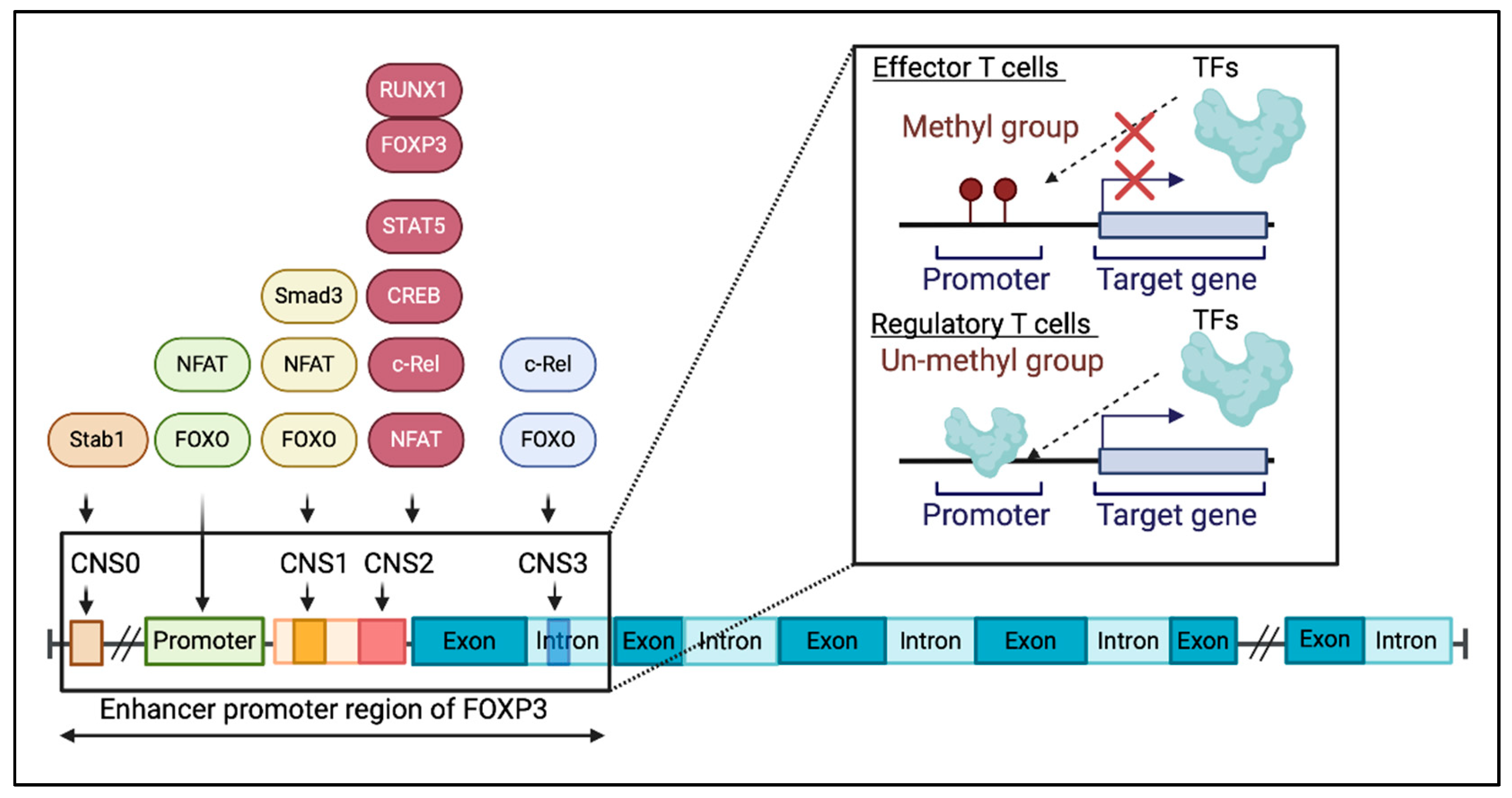

3.1. FOXP3 Expression in Tregs

3.2. Activation-Induced FOXP3 Expression in T Cells

4. FOXP3 Gene Mutations Are Associated with IPEX Syndrome

5. FOXP3, Implications in Autoimmune Disorders

5.1. T1D

5.2. IBD

5.3. Multiple Sclerosis and Myasthenia Gravis

6. The Role of FOXP3 in Transplantation

6.1. The Role of FOXP3 in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

6.2. The Role of FOXP3 in Solid Organ Transplantation

7. The Role of FOXP3 in Allergic Disease

7.1. The Role of Tregs in Food Allergy

7.2. The Role of Tregs in Various Allergic Disease (Asthma, Atopic Dermatitis and Urticaria)

8. The Role of FOXP3 in Cancer

8.1. The Role of FOXP3 Expression in Cancer Cell

8.2. The Role of Tregs in the Tumor Microenvironment

9. Treg Cell Therapy

9.1. Engineered Tregs

9.2. CAR-Treg

10. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sakaguchi, S.; Miyara, M.; Costantino, C.M.; Hafler, D.A. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in the human immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2010, 10, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudensky, A.Y. Regulatory T cells and Foxp3. Immunol Rev 2011, 241, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, E.W.; Brosens, J.J.; Gomes, A.R.; Koo, C.Y. Forkhead box proteins: tuning forks for transcriptional harmony. Nat Rev Cancer 2013, 13, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, B.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Berezov, A.; Xu, C.; Gao, Y.; Li, Z. , et al. Structural and biological features of FOXP3 dimerization relevant to regulatory T cell function. Cell Rep 2012, 1, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.P.; Sollars, V.E.; Belalcazar Adel, P. Domain requirements for the diverse immune regulatory functions of foxp3. Mol Immunol 2011, 48, 1932–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhairavabhotla, R.; Kim, Y.C.; Glass, D.D.; Escobar, T.M.; Patel, M.C.; Zahr, R.; Nguyen, C.K.; Kilaru, G.K.; Muljo, S.A.; Shevach, E.M. Transcriptome profiling of human FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Hum Immunol 2016, 77, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadlon, T.J.; Wilkinson, B.G.; Pederson, S.; Brown, C.Y.; Bresatz, S.; Gargett, T.; Melville, E.L.; Peng, K.; D’Andrea, R.J.; Glonek, G.G. , et al. Genome-wide identification of human FOXP3 target genes in natural regulatory T cells. J Immunol 2010, 185, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Veeken, J.; Glasner, A.; Zhong, Y.; Hu, W.; Wang, Z.M.; Bou-Puerto, R.; Charbonnier, L.M.; Chatila, T.A.; Leslie, C.S.; Rudensky, A.Y. The Transcription Factor Foxp3 Shapes Regulatory T Cell Identity by Tuning the Activity of trans-Acting Intermediaries. Immunity 2020, 53, 971–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delacher, M.; Simon, M.; Sanderink, L.; Hotz-Wagenblatt, A.; Wuttke, M.; Schambeck, K.; Schmidleithner, L.; Bittner, S.; Pant, A.; Ritter, U. , et al. Single-cell chromatin accessibility landscape identifies tissue repair program in human regulatory T cells. Immunity 2021, 54, 702–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi, S.; Sakaguchi, N.; Asano, M.; Itoh, M.; Toda, M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol 1995, 155, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hori, S.; Nomura, T.; Sakaguchi, S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science 2003, 299, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontenot, J.D.; Gavin, M.A.; Rudensky, A.Y. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 2003, 4, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, D.L.; Mahmud, S.A.; Sjaastad, L.E.; Williams, J.B.; Spanier, J.A.; Simeonov, D.R.; Ruscher, R.; Huang, W.; Proekt, I.; Miller, C.N. , et al. Thymic regulatory T cells arise via two distinct developmental programs. Nat Immunol 2019, 20, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herppich, S.; Toker, A.; Pietzsch, B.; Kitagawa, Y.; Ohkura, N.; Miyao, T.; Floess, S.; Hori, S.; Sakaguchi, S.; Huehn, J. Dynamic Imprinting of the Treg Cell-Specific Epigenetic Signature in Developing Thymic Regulatory T Cells. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, U.; Werner, J.; Schildknecht, K.; Schulze, J.J.; Mulu, A.; Liebert, U.G.; Sack, U.; Speckmann, C.; Gossen, M.; Wong, R.J. , et al. Epigenetic immune cell counting in human blood samples for immunodiagnostics. Sci Transl Med 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, S.E.; Crome, S.Q.; Crellin, N.K.; Passerini, L.; Steiner, T.S.; Bacchetta, R.; Roncarolo, M.G.; Levings, M.K. Activation-induced FOXP3 in human T effector cells does not suppress proliferation or cytokine production. Int Immunol 2007, 19, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ioan-Facsinay, A.; van der Voort, E.I.; Huizinga, T.W.; Toes, R.E. Transient expression of FOXP3 in human activated nonregulatory CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol 2007, 37, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, C.L.; Ochs, H.D. IPEX is a unique X-linked syndrome characterized by immune dysfunction, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, and a variety of autoimmune phenomena. Curr Opin Pediatr 2001, 13, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatila, T.A.; Blaeser, F.; Ho, N.; Lederman, H.M.; Voulgaropoulos, C.; Helms, C.; Bowcock, A.M. JM2, encoding a fork head-related protein, is mutated in X-linked autoimmunity-allergic disregulation syndrome. J Clin Invest 2000, 106, R75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildin, R.S.; Ramsdell, F.; Peake, J.; Faravelli, F.; Casanova, J.L.; Buist, N.; Levy-Lahad, E.; Mazzella, M.; Goulet, O.; Perroni, L. , et al. X-linked neonatal diabetes mellitus, enteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy. Nat Genet 2001, 27, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, B.R.; Buist, N.R.; Stenzel, P. An X-linked syndrome of diarrhea, polyendocrinopathy, and fatal infection in infancy. J Pediatr 1982, 100, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacchetta, R.; Barzaghi, F.; Roncarolo, M.G. From IPEX syndrome to FOXP3 mutation: a lesson on immune dysregulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2018, 1417, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzaghi, F.; Amaya Hernandez, L.C.; Neven, B.; Ricci, S.; Kucuk, Z.Y.; Bleesing, J.J.; Nademi, Z.; Slatter, M.A.; Ulloa, E.R.; Shcherbina, A. , et al. Long-term follow-up of IPEX syndrome patients after different therapeutic strategies: An international multicenter retrospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018, 141, 1036–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, S.K.; Walsh, T.; Casadei, S.; Eckert, M.M.; Allenspach, E.J.; Hagin, D.; Segundo, G.; Lee, M.K.; Gulsuner, S.; Shirts, B.H. , et al. Molecular diagnosis of childhood immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, and enteropathy, and implications for clinical management. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022, 149, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cepika, A.M.; Sato, Y.; Liu, J.M.; Uyeda, M.J.; Bacchetta, R.; Roncarolo, M.G. Tregopathies: Monogenic diseases resulting in regulatory T-cell deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018, 142, 1679–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornvold, M.; Amundsen, S.S.; Stene, L.C.; Joner, G.; Dahl-Jorgensen, K.; Njolstad, P.R.; Ek, J.; Ascher, H.; Gudjonsdottir, A.H.; Lie, B.A. , et al. FOXP3 polymorphisms in type 1 diabetes and coeliac disease. J Autoimmun 2006, 27, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, C.M.; Peakman, M.; Tree, T.I.M. Regulatory T cell dysfunction in type 1 diabetes: what’s broken and how can we fix it? Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1839–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, J.N.; Omer, O.S.; Tasker, S.; Lord, G.M.; Irving, P.M. Regulatory T-cell therapy in Crohn’s disease: challenges and advances. Gut 2020, 69, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zozulya, A.L.; Wiendl, H. The role of regulatory T cells in multiple sclerosis. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2008, 4, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danikowski, K.M.; Jayaraman, S.; Prabhakar, B.S. Regulatory T cells in multiple sclerosis and myasthenia gravis. J Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.; Komai, K.; Mise-Omata, S.; Iizuka-Koga, M.; Noguchi, Y.; Kondo, T.; Sakai, R.; Matsuo, K.; Nakayama, T.; Yoshie, O. , et al. Brain regulatory T cells suppress astrogliosis and potentiate neurological recovery. Nature 2019, 565, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, A. NMDAR-directed CAAR T cells show promise for autoimmune encephalitis. Nat Rev Immunol 2023, 23, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crunkhorn, S. CAAR T cells to treat encephalitis. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2024, 23, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, K.; Mielke, S.; Ahmadzadeh, M.; Kilical, Y.; Savani, B.N.; Zeilah, J.; Keyvanfar, K.; Montero, A.; Hensel, N.; Kurlander, R. , et al. High donor FOXP3-positive regulatory T-cell (Treg) content is associated with a low risk of GVHD following HLA-matched allogeneic SCT. Blood 2006, 108, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, E.H.; Laport, G.; Xie, B.J.; MacDonald, K.; Heydari, K.; Sahaf, B.; Tang, S.W.; Baker, J.; Armstrong, R.; Tate, K. , et al. Transplantation of donor grafts with defined ratio of conventional and regulatory T cells in HLA-matched recipients. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncarolo, M.G.; Gregori, S.; Bacchetta, R.; Battaglia, M.; Gagliani, N. The Biology of T Regulatory Type 1 Cells and Their Therapeutic Application in Immune-Mediated Diseases. Immunity 2018, 49, 1004–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.M.; Chen, P.; Uyeda, M.J.; Cieniewicz, B.; Sayitoglu, E.C.; Thomas, B.C.; Sato, Y.; Bacchetta, R.; Cepika, A.M.; Roncarolo, M.G. Pre-clinical development and molecular characterization of an engineered type 1 regulatory T-cell product suitable for immunotherapy. Cytotherapy 2021, 23, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mfarrej, B.; Tresoldi, E.; Stabilini, A.; Paganelli, A.; Caldara, R.; Secchi, A.; Battaglia, M. Generation of donor-specific Tr1 cells to be used after kidney transplantation and definition of the timing of their in vivo infusion in the presence of immunosuppression. J Transl Med 2017, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Truong, N.; Grossman, W.J.; Haribhai, D.; Williams, C.B.; Wang, J.; Martin, M.G.; Chatila, T.A. Allergic dysregulation and hyperimmunoglobulinemia E in Foxp3 mutant mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005, 116, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narula, M.; Lakshmanan, U.; Borna, S.; Schulze, J.J.; Holmes, T.H.; Harre, N.; Kirkey, M.; Ramachandran, A.; Tagi, V.M.; Barzaghi, F. , et al. Epigenetic and immunological indicators of IPEX disease in subjects with FOXP3 gene mutation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023, 151, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gool, F.; Nguyen, M.L.T.; Mumbach, M.R.; Satpathy, A.T.; Rosenthal, W.L.; Giacometti, S.; Le, D.T.; Liu, W.; Brusko, T.M.; Anderson, M.S. , et al. A Mutation in the Transcription Factor Foxp3 Drives T Helper 2 Effector Function in Regulatory T Cells. Immunity 2019, 50, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noval Rivas, M.; Chatila, T.A. Regulatory T cells in allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016, 138, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgerson, T.R.; Linane, A.; Moes, N.; Anover, S.; Mateo, V.; Rieux-Laucat, F.; Hermine, O.; Vijay, S.; Gambineri, E.; Cerf-Bensussan, N. , et al. Severe food allergy as a variant of IPEX syndrome caused by a deletion in a noncoding region of the FOXP3 gene. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 1705–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, A.; Garcia, M.A.; Lyu, S.C.; Bucayu, R.; Kohli, A.; Ishida, S.; Berglund, J.P.; Tsai, M.; Maecker, H.; O’Riordan, G. , et al. Peanut oral immunotherapy results in increased antigen-induced regulatory T-cell function and hypomethylation of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3). J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014, 133, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paparo, L.; Nocerino, R.; Cosenza, L.; Aitoro, R.; D’Argenio, V.; Del Monaco, V.; Di Scala, C.; Amoroso, A.; Di Costanzo, M.; Salvatore, F. , et al. Epigenetic features of FoxP3 in children with cow’s milk allergy. Clin Epigenetics 2016, 8, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Bartolome-Casado, R.; Xu, C.; Bertocchi, A.; Janney, A.; Heuberger, C.; Pearson, C.F.; Teichmann, S.A.; Thornton, E.E.; Powrie, F. Immune microniches shape intestinal T(reg) function. Nature 2024, 628, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provoost, S.; Maes, T.; Van Durme, Y.M.; Gevaert, P.; Bachert, C.; Schmidt-Weber, C.B.; Brusselle, G.G.; Joos, G.F.; Tournoy, K.G. Decreased FOXP3 protein expression in patients with asthma. Allergy 2009, 64, 1539–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roesner, L.M.; Floess, S.; Witte, T.; Olek, S.; Huehn, J.; Werfel, T. Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells are expanded in severe atopic dermatitis patients. Allergy 2015, 70, 1656–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fyhrquist, N.; Lehtimaki, S.; Lahl, K.; Savinko, T.; Lappetelainen, A.M.; Sparwasser, T.; Wolff, H.; Lauerma, A.; Alenius, H. Foxp3+ cells control Th2 responses in a murine model of atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2012, 132, 1672–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.S.; Sui, J.F.; Chen, X.H.; Ran, X.Z.; Yang, Z.F.; Guan, W.D.; Yang, T. Detection of CD4+ CD25+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in peripheral blood of patients with chronic autoimmune urticaria. Australas J Dermatol 2011, 52, e15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, F.; Ladoire, S.; Mignot, G.; Apetoh, L.; Ghiringhelli, F. Human FOXP3 and cancer. Oncogene 2010, 29, 4121–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, M.; Seki, N.; Toh, U.; Hattori, S.; Kawahara, A.; Yamaguchi, T.; Koura, K.; Takahashi, R.; Otsuka, H.; Takahashi, H. , et al. FOXP3 expression in tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes is associated with breast cancer prognosis. Mol Clin Oncol 2013, 1, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, T.; Liu, R.; Zhang, H.; Chang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zheng, P.; Liu, Y. FOXP3 is a novel transcriptional repressor for the breast cancer oncogene SKP2. J Clin Invest 2007, 117, 3765–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curiel, T.J.; Coukos, G.; Zou, L.; Alvarez, X.; Cheng, P.; Mottram, P.; Evdemon-Hogan, M.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; Zhang, L.; Burow, M. , et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med 2004, 10, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Nishikawa, H.; Wada, H.; Nagano, Y.; Sugiyama, D.; Atarashi, K.; Maeda, Y.; Hamaguchi, M.; Ohkura, N.; Sato, E. , et al. Two FOXP3(+)CD4(+) T cell subpopulations distinctly control the prognosis of colorectal cancers. Nat Med 2016, 22, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluestone, J.A.; Buckner, J.H.; Fitch, M.; Gitelman, S.E.; Gupta, S.; Hellerstein, M.K.; Herold, K.C.; Lares, A.; Lee, M.R.; Li, K. , et al. Type 1 diabetes immunotherapy using polyclonal regulatory T cells. Sci Transl Med 2015, 7, 315ra189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.M.R.; Muller, Y.D.; Bluestone, J.A.; Tang, Q. Next-generation regulatory T cell therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019, 18, 749–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluestone, J.A.; McKenzie, B.S.; Beilke, J.; Ramsdell, F. Opportunities for Treg cell therapy for the treatment of human disease. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1166135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M.; Stabilini, A.; Migliavacca, B.; Horejs-Hoeck, J.; Kaupper, T.; Roncarolo, M.G. Rapamycin promotes expansion of functional CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells of both healthy subjects and type 1 diabetic patients. J Immunol 2006, 177, 8338–8347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, H.; Safinia, N.; Grageda, N.; Thirkell, S.; Lowe, K.; Fry, L.J.; Scotta, C.; Hope, A.; Fisher, C.; Hilton, R. , et al. A Rapamycin-Based GMP-Compatible Process for the Isolation and Expansion of Regulatory T Cells for Clinical Trials. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2018, 8, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawitzki, B.; Harden, P.N.; Reinke, P.; Moreau, A.; Hutchinson, J.A.; Game, D.S.; Tang, Q.; Guinan, E.C.; Battaglia, M.; Burlingham, W.J. , et al. Regulatory cell therapy in kidney transplantation (The ONE Study): a harmonised design and analysis of seven non-randomised, single-arm, phase 1/2A trials. Lancet 2020, 395, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, S.E.; Alstad, A.N.; Merindol, N.; Crellin, N.K.; Amendola, M.; Bacchetta, R.; Naldini, L.; Roncarolo, M.G.; Soudeyns, H.; Levings, M.K. Generation of potent and stable human CD4+ T regulatory cells by activation-independent expression of FOXP3. Mol Ther 2008, 16, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passerini, L.; Rossi Mel, E.; Sartirana, C.; Fousteri, G.; Bondanza, A.; Naldini, L.; Roncarolo, M.G.; Bacchetta, R. CD4(+) T cells from IPEX patients convert into functional and stable regulatory T cells by FOXP3 gene transfer. Sci Transl Med 2013, 5, 215ra174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Passerini, L.; Piening, B.D.; Uyeda, M.J.; Goodwin, M.; Gregori, S.; Snyder, M.P.; Bertaina, A.; Roncarolo, M.G.; Bacchetta, R. Human-engineered Treg-like cells suppress FOXP3-deficient T cells but preserve adaptive immune responses in vivo. Clin Transl Immunology 2020, 9, e1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Nathan, A.; Shipp, S.; Wright, J.F.; Tate, K.M.; Wani, P.; Roncarolo, M.G.; Bacchetta, R. A novel FOXP3 knockout-humanized mouse model for pre-clinical safety and efficacy evaluation of Treg-like cell products. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2023, 31, 101150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borna, S.; Lee, E.; Sato, Y.; Bacchetta, R. Towards gene therapy for IPEX syndrome. Eur J Immunol 2022, 52, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, M.; Lee, E.; Lakshmanan, U.; Shipp, S.; Froessl, L.; Barzaghi, F.; Passerini, L.; Narula, M.; Sheikali, A.; Lee, C.M. , et al. CRISPR-based gene editing enables FOXP3 gene repair in IPEX patient cells. Sci Adv 2020, 6, eaaz0571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honaker, Y.; Hubbard, N.; Xiang, Y.; Fisher, L.; Hagin, D.; Sommer, K.; Song, Y.; Yang, S.J.; Lopez, C.; Tappen, T. , et al. Gene editing to induce FOXP3 expression in human CD4(+) T cells leads to a stable regulatory phenotype and function. Sci Transl Med 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, A.J.; Lin, D.T.S.; Gillies, J.K.; Uday, P.; Pesenacker, A.M.; Kobor, M.S.; Levings, M.K. Optimized CRISPR-mediated gene knockin reveals FOXP3-independent maintenance of human Treg identity. Cell Rep 2021, 36, 109494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Liu, J.; Lee, E.; Perriman, R.; Roncarolo, M.G.; Bacchetta, R. Co-Expression of FOXP3FL and FOXP3Delta2 Isoforms Is Required for Optimal Treg-Like Cell Phenotypes and Suppressive Function. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 752394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, M.J.; Tune, M.K.; Cabrera, J.C.; Torres-Castillo, J.; He, M.; Feng, Y.; Doerschuk, C.M.; Dang, H.; Beltran, A.S.; Hagan, R.S. , et al. Characterization of the MT-2 Treg-like cell line in the presence and absence of forkhead box P3 (FOXP3). Immunol Cell Biol 2024, 102, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, A.J.; Haque, M.; Ward-Hartstonge, K.A.; Uday, P.; Wardell, C.M.; Gillies, J.K.; Speck, M.; Mojibian, M.; Klein Geltink, R.I.; Levings, M.K. PTEN is required for human Treg suppression of costimulation in vitro. Eur J Immunol 2022, 52, 1482–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Osada, E.; Manome, Y. Non-canonical NFKB signaling endows suppressive function through FOXP3-dependent regulatory T cell program. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, K.G.; Hoeppli, R.E.; Huang, Q.; Gillies, J.; Luciani, D.S.; Orban, P.C.; Broady, R.; Levings, M.K. Alloantigen-specific regulatory T cells generated with a chimeric antigen receptor. J Clin Invest 2016, 126, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, K.N.; Piret, J.M.; Levings, M.K. Methods to manufacture regulatory T cells for cell therapy. Clin Exp Immunol 2019, 197, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, K.N.; Ivison, S.; Hippen, K.L.; Hoeppli, R.E.; Hall, M.; Zheng, G.; Dijke, I.E.; Aklabi, M.A.; Freed, D.H.; Rebeyka, I. , et al. Cryopreservation timing is a critical process parameter in a thymic regulatory T-cell therapy manufacturing protocol. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 1216–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, N.A.; Lamarche, C.; Hoeppli, R.E.; Bergqvist, P.; Fung, V.C.; McIver, E.; Huang, Q.; Gillies, J.; Speck, M.; Orban, P.C. , et al. Systematic testing and specificity mapping of alloantigen-specific chimeric antigen receptors in regulatory T cells. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangamo Therapeutics. Safety & Tolerability Study of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Reg Cell Therapy in Living Donor Renal Transplant Recipients. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04817774: 2021.

- Pierini, A.; Iliopoulou, B.P.; Peiris, H.; Perez-Cruz, M.; Baker, J.; Hsu, K.; Gu, X.; Zheng, P.P.; Erkers, T.; Tang, S.W. , et al. T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptor promote immune tolerance. JCI Insight 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, X.; Alvarez Calderon, F.; Wobma, H.; Gerdemann, U.; Albanese, A.; Cagnin, L.; McGuckin, C.; Michaelis, K.A.; Naqvi, K.; Blazar, B.R. , et al. Human OX40L-CAR-T(regs) target activated antigen-presenting cells and control T cell alloreactivity. Sci Transl Med 2024, 16, eadj9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).