Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

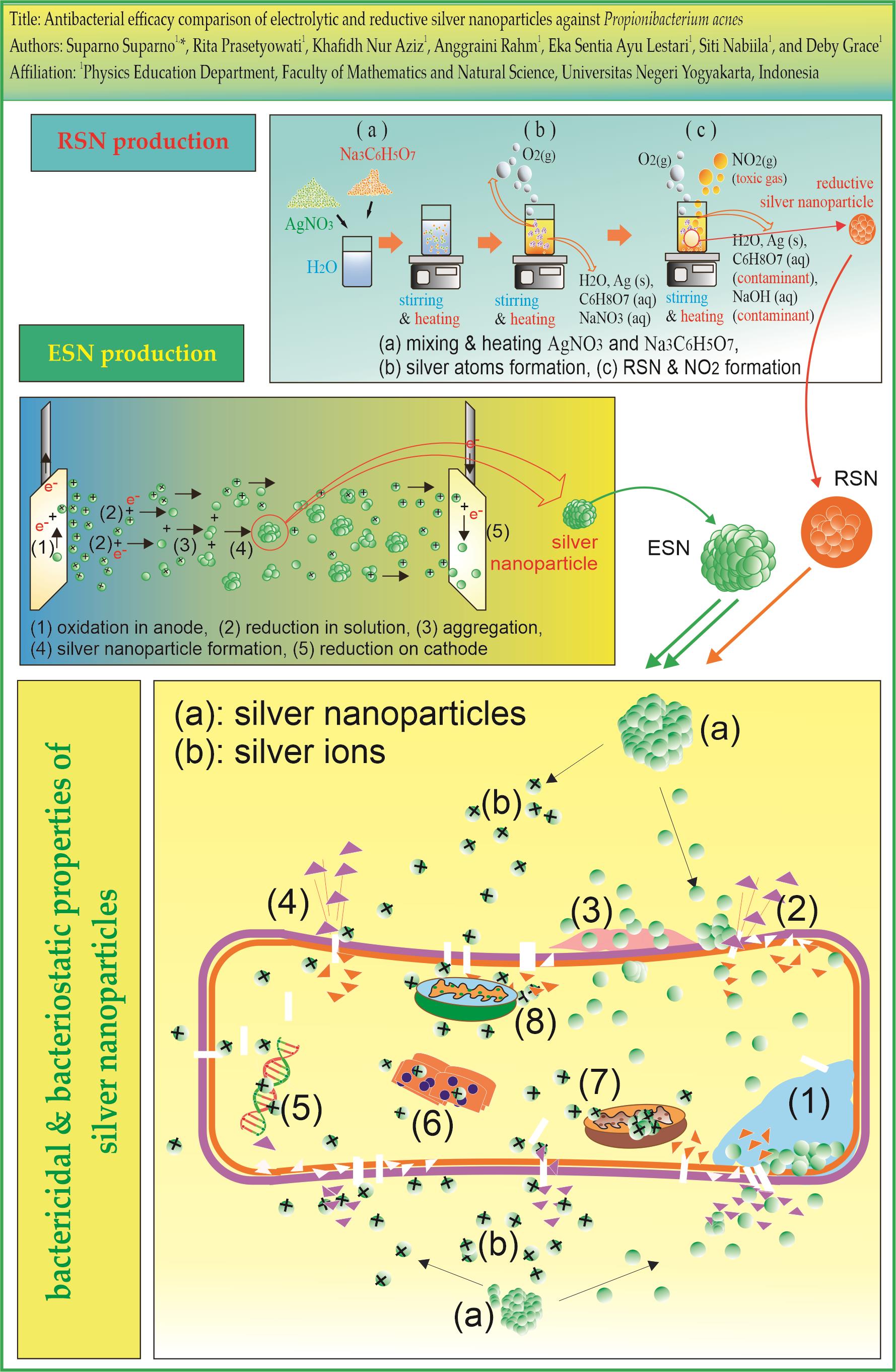

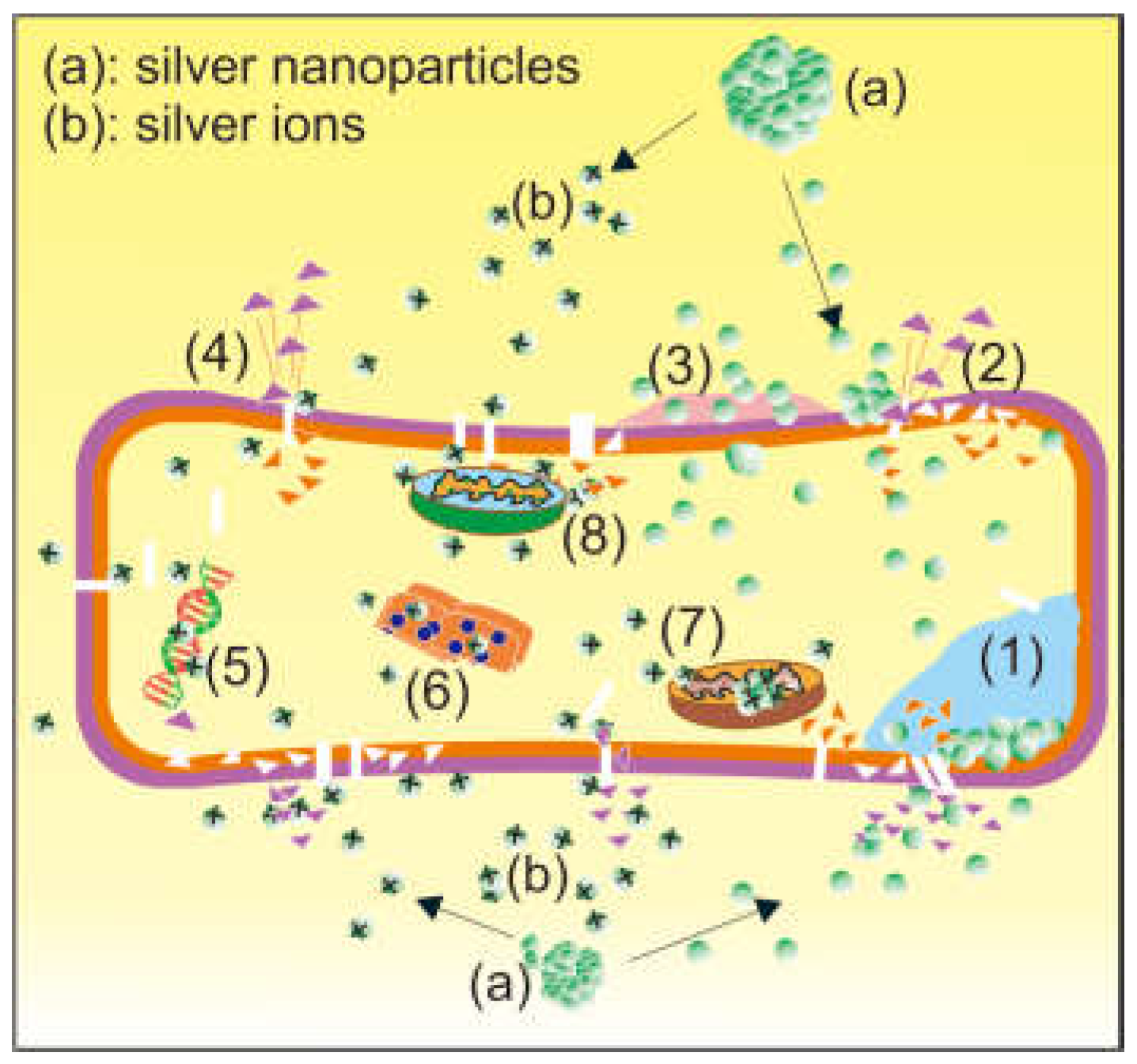

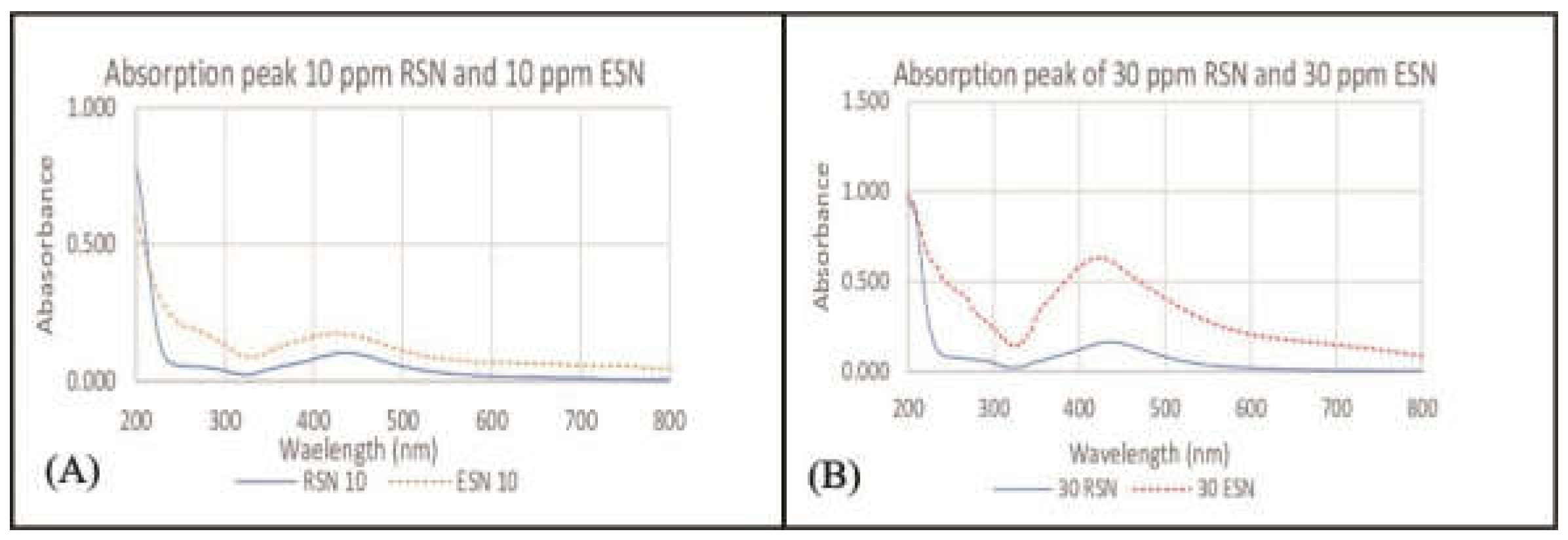

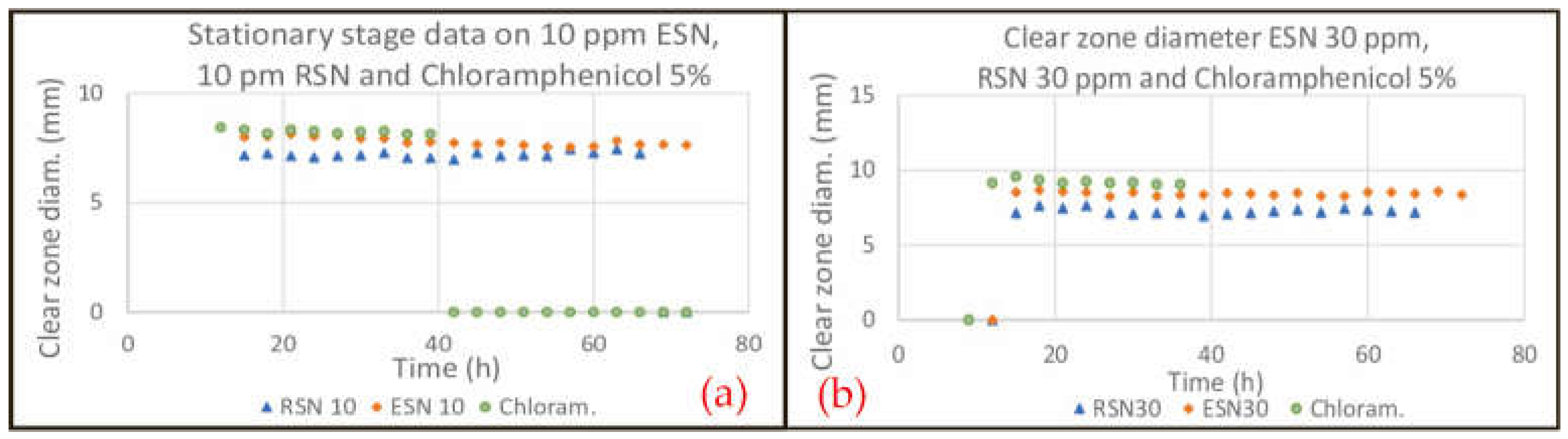

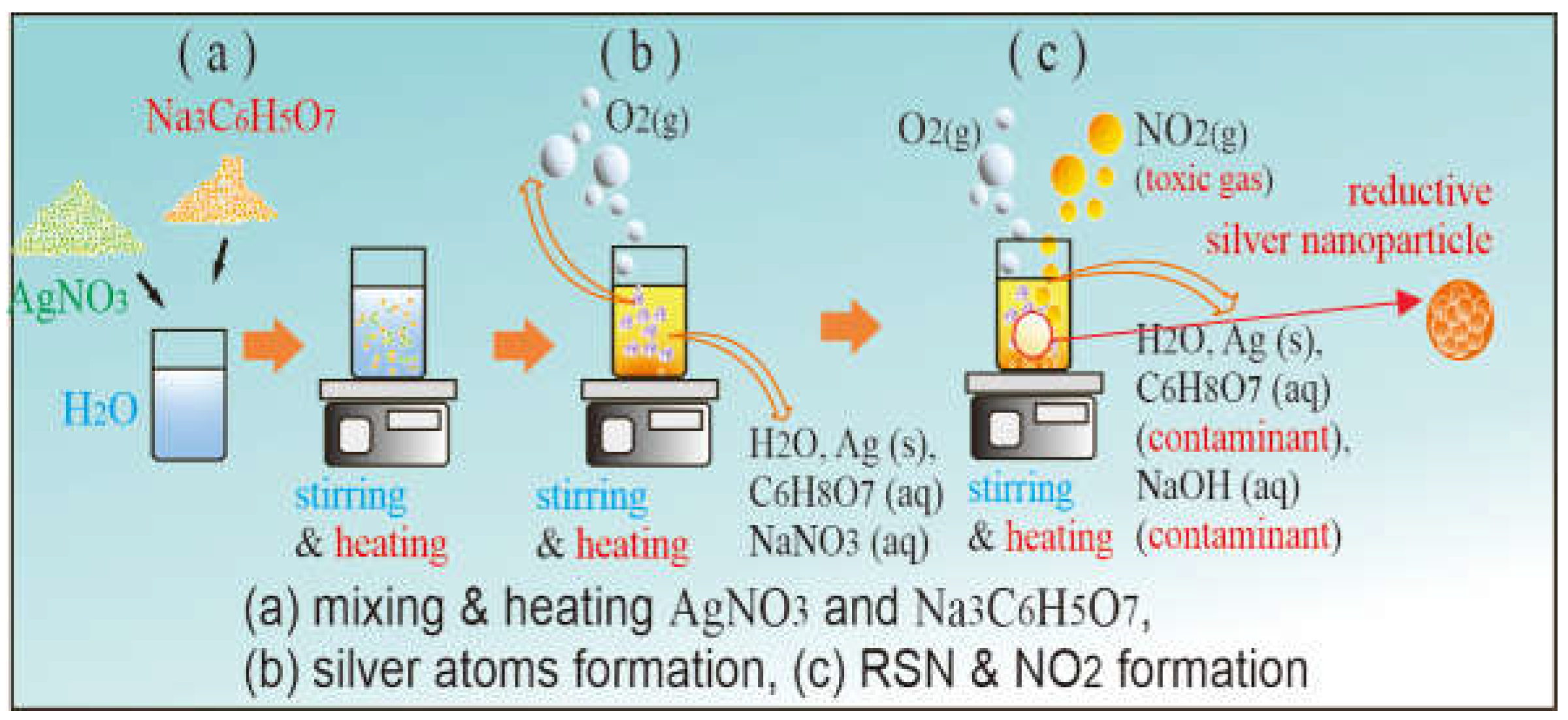

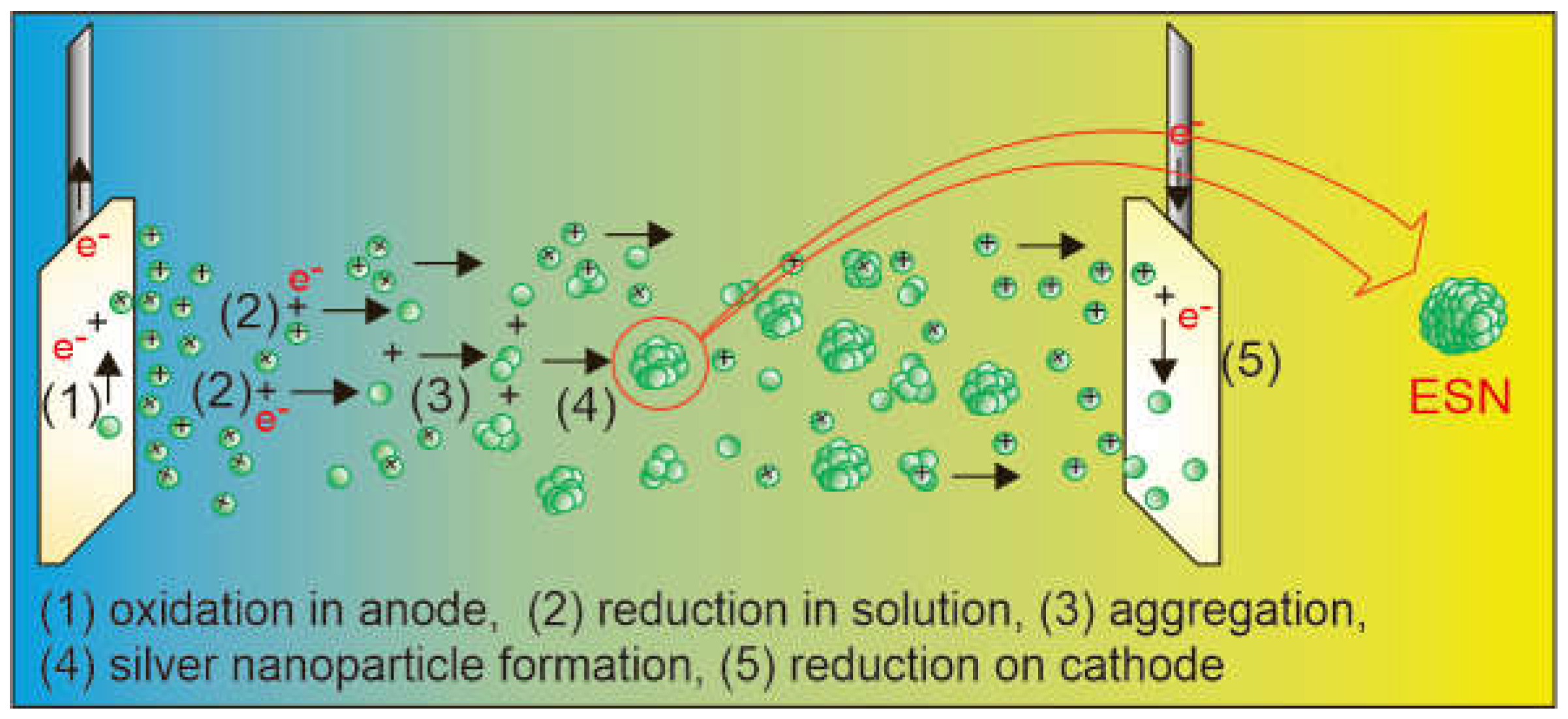

The increasing interest in developing silver nanoparticles as antibiotic raw materials has attracted much attention, as the most common reduction and electrolysis techniques produce the toxic gas byproduct nitrogen dioxide. This paper reports a successful effort to develop a modified toxic-free electrolysis technique to produce electrolytic silver nanoparticles (ESN). A comparison of the physical and biological properties of ESN and reductive silver nanoparticles (RSN) was made. The presence of silver atoms in the solution was determined using a UV visible spectrometer and absorption peaks were found at 425 nm (ESN) and 437 nm (RSN). The particle size in solution was determined using dynamic light scattering and the diameter was found to be approximately 40 nm (for ESN) and 70 nm (for RSN). Antibacterial efficacy and power to prevent the development of bacterial resistance against Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) were assessed using the Kirby-Bauer method. Statistical analysis of clear zone diameter data showed that unlike RSN, the efficacy of ESN increased with higher concentrations. The efficacy of ESN and RSN is relatively lower than Chloramphenicol 5% because it is measured in different concentration units (ESN and RSN in ppm and Chloramphenicol in %). By using a calibration curve, the efficacy of 5% Chloramphenicol can be equated to 0.005% ESN. In addition, P. acnes developed strong resistance to Chloramphenicol, weak resistance to RSN and showed no resistance to ESN. These findings underscore the extraordinary potential of ESN as a raw material for future antibiotics.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

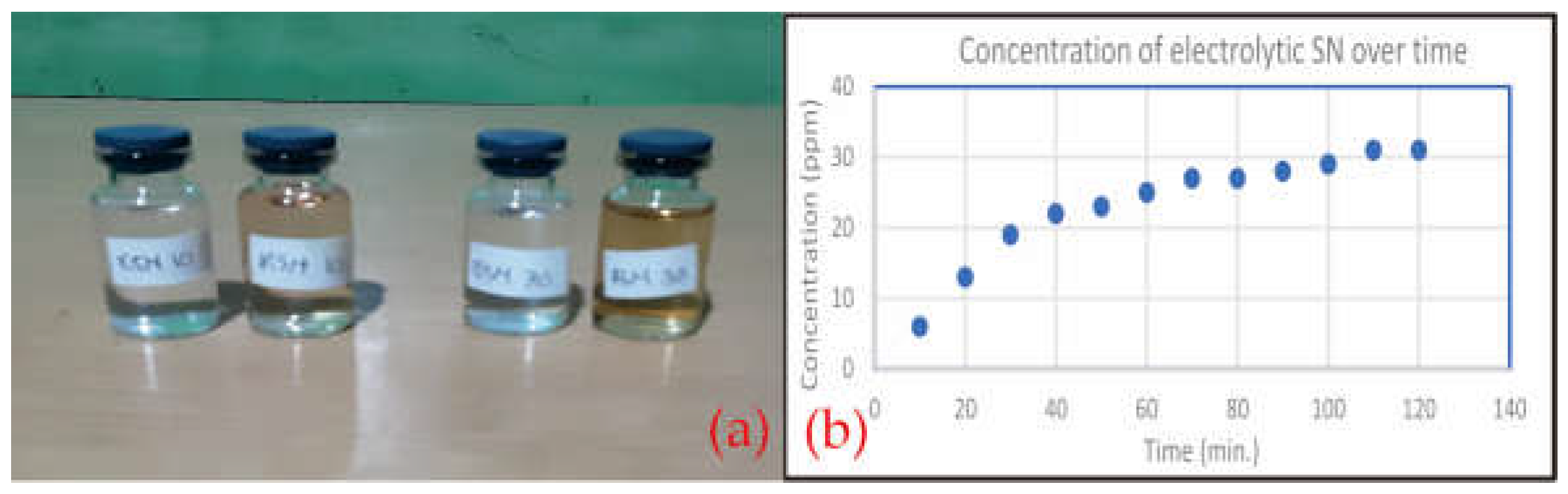

2.1. Comparison of Solution Colours

2.2. Silver Content in Solution

2.3. Particle Size Comparison

2.4. Efficacy and Power to Prevent Resistance

3. Discussions

3.2. Comparison of Solution Colours

3.2. Silver Content in Solution

3.3. Particle Size Comparison

3.4. Efficacy and Power to Prevent Resistance

4. Material and Method

4.1. RSN Production

4.2. ESN Production

4.3. Observation of Solution Colour

4.4. Detection of Silver in Solution

4.5. Particle Size Determination

4.6. Antibacterial Activity Observation

5. Conclusion

References

- Breijyeh Z and Karaman R 2023 Design and Synthesis of Novel Antimicrobial Agents Antibiotics 12. [CrossRef]

- Lei J, Sun L C, Huang S, Zhu C, Li P, He J, Mackey V, Coy D H and He Q Y 2019 The antimicrobial peptides and their potential clinical applications Am J Transl Res 11.

- Patangia D V., Anthony Ryan C, Dempsey E, Paul Ross R and Stanton C 2022 Impact of antibiotics on the human microbiome and consequences for host health Microbiologyopen 11. [CrossRef]

- Fair R J and Tor Y 2014 The Rise of Antibiotic Resistance Perspect Medicin Chem 6. [CrossRef]

- Reding C, Catalán P, Jansen G, Bergmiller T, Wood E, Rosenstiel P, Schulenburg H, Gudelj I and Beardmore R 2021 The Antibiotic Dosage of Fastest Resistance Evolution: Gene Amplifications Underpinning the Inverted-U Mol Biol Evol 38. [CrossRef]

- Muteeb G 2023 Nanotechnology—A Light of Hope for Combating Antibiotic Resistance Microorganisms 11. [CrossRef]

- Pila G, Segarra D and Cerna M 2023 Antibacterial effect of Cannabidiol oil against Propionibacterium acnes, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis and level of toxicity against Artemia salina Bionatura 8.

- Achermann Y, Goldstein E J C, Coenye T and Shirtliffa M E 2014 Propionibacterium acnes: From Commensal to opportunistic biofilm-associated implant pathogen Clin Microbiol Rev 27. [CrossRef]

- Bronnec V, Eilers H, Jahns A C, Omer H and Alexeyev O A 2022 Propionibacterium (Cutibacterium) granulosum Extracellular DNase BmdE Targeting Propionibacterium (Cutibacterium) acnes Biofilm Matrix, a Novel Inter-Species Competition Mechanism Front Cell Infect Microbiol 11. [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon N, Kamat V A, Lerner B, Perez M and Bhansali S 2019 The Use of Lab on a Chip Devices to Evaluate Infectious Biofilm Formation and Assess Antibiotics and Nano Drugs Treatments ECS Meeting Abstracts MA2019-01. [CrossRef]

- Suparno S, Ayu Lestari E S and Grace D 2024 Antibacterial activity of Bajakah Kalalawit phenolic against Staphylococcus aureus and possible use of phenolic nanoparticles Sci Rep 14 19734. [CrossRef]

- Tan Z, Deng J, Ye Q and Zhang Z 2022 The Antibacterial Activity of Natural-derived Flavonoids Curr Top Med Chem 22. [CrossRef]

- Girma A 2023 Alternative mechanisms of action of metallic nanoparticles to mitigate the global spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria The Cell Surface 10. [CrossRef]

- Singh I, Mazhar T, Shrivastava V and Singh Tomar R 2022 Bio-assisted synthesis of bi-metallic (Ag-Zn) nanoparticles by leaf extract of Azadirachta indica and its antimicrobial properties International Journal of Nano Dimension 13. [CrossRef]

- Prasad S R, Teli S B, Ghosh J, Prasad N R, Shaikh V S, Nazeruddin G M, Al-Sehemi A G, Patel I and Shaikh Y I 2021 A Review on Bio-inspired Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: Their Antimicrobial Efficacy and Toxicity Engineered Science 16. [CrossRef]

- Liao C, Li Y and Tjong S C 2019 Bactericidal and cytotoxic properties of silver nanoparticles Int J Mol Sci 20. [CrossRef]

- Pletikapić G, Žutić V, Vinković Vrček I and Svetličić V 2012 Atomic force microscopy characterization of silver nanoparticles interactions with marine diatom cells and extracellular polymeric substance Journal of Molecular Recognition vol 25. [CrossRef]

- Veeraraghavan V P, Periadurai N D, Karunakaran T, Hussain S, Surapaneni K M and Jiao X 2021 Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from aqueous extract of Scutellaria barbata and coating on the cotton fabric for antimicrobial applications and wound healing activity in fibroblast cells (L929) Saudi J Biol Sci 28. [CrossRef]

- Lethongkam S, Paosen S, Bilhman S, Dumjun K, Wunnoo S, Choojit S, Siri R, Daengngam C, Voravuthikunchai S P and Bejrananda T 2022 Eucalyptus-Mediated Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles-Coated Urinary Catheter Inhibits Microbial Migration and Biofilm Formation Nanomaterials 12. [CrossRef]

- Durán N, Durán M, de Jesus M B, Seabra A B, Fávaro W J and Nakazato G 2016 Silver nanoparticles: A new view on mechanistic aspects on antimicrobial activity Nanomedicine 12. [CrossRef]

- Hume S L, Chiaramonti A N, Rice K P, Schwindt R K, MacCuspie R I and Jeerage K M 2015 Timescale of silver nanoparticle transformation in neural cell cultures impacts measured cell response Journal of Nanoparticle Research 17. [CrossRef]

- Gordon O, Slenters T V, Brunetto P S, Villaruz A E, Sturdevant D E, Otto M, Landmann R and Fromm K M 2010 Silver coordination polymers for prevention of implant infection: Thiol interaction, impact on respiratory chain enzymes, and hydroxyl radical induction Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54. [CrossRef]

- Thammawithan S, Talodthaisong C, Srichaiyapol O, Patramanon R, Hutchison J A and Kulchat S 2022 Andrographolide stabilized-silver nanoparticles overcome ceftazidime-resistant Burkholderia pseudomallei: study of antimicrobial activity and mode of action Sci Rep 12. [CrossRef]

- Li A, Zheng N and Ding X 2022 Mitochondrial abnormalities: a hub in metabolic syndrome-related cardiac dysfunction caused by oxidative stress Heart Fail Rev 27. [CrossRef]

- Raisanen A L, Mueller C M, Chaudhuri S, Schatz G C and Kushner M J 2022 A reaction mechanism for plasma electrolysis of AgNO3forming silver nanoclusters and nanoparticles J Appl Phys 132. [CrossRef]

- Naderi-Samani E, Razavi R S, Nekouee K and Naderi-Samani H 2023 Synthesis of silver nanoparticles for use in conductive inks by chemical reduction method Heliyon 9. [CrossRef]

- Yantcheva N S, Karashanova D B, Georgieva B C, Vasileva I N, Stoyanova A S, Denev P N, Dinkova R H, Ognyanov M H and Slavov A M 2019 Characterization and application of spent brewer’s yeast for silver nanoparticles synthesis Bulgarian Chemical Communications 51.

- Wahab S, Khan T, Adil M and Khan A 2021 Mechanistic aspects of plant-based silver nanoparticles against multi-drug resistant bacteria Heliyon 7. [CrossRef]

- Roy A, Bulut O, Some S, Mandal A K and Yilmaz M D 2019 Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Biomolecule-nanoparticle organizations targeting antimicrobial activity RSC Adv 9. [CrossRef]

- Sadiq M U, Shah A, Haleem A, Shah S M and Shah I 2023 Eucalyptus globulus Mediated Green Synthesis of Environmentally Benign Metal Based Nanostructures: A Review Nanomaterials 13. [CrossRef]

- Ezealisiji K M, Noundou X S and Ukwueze S E 2017 Green synthesis and characterization of monodispersed silver nanoparticles using root bark aqueous extract of annona muricata linn and their antimicrobial activity Applied Nanoscience (Switzerland) 7. [CrossRef]

- J. Kasprowicz M, Gorczyca A and Janas P 2016 Production of Silver Nanoparticles Using High Voltage Arc Discharge Method Curr Nanosci 12. [CrossRef]

- Hidayah A N, Triyono D, Saputra A B, Herbani Y, Isnaeni I and Suliyanti M M 2019 Stabilization of Au-Ag Nanoalloys with Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) as Capping Agent Journal of Physics: Conference Series vol 1191. [CrossRef]

- Amer S S, Mamdouh W, Nasr M, ElShaer A, Polycarpou E, Abdel-Aziz R T A and Sammour O A 2022 Quercetin loaded cosm-nutraceutical electrospun composite nanofibers for acne alleviation: Preparation, characterization and experimental clinical appraisal Int J Pharm 612. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Danial A, Koh S P, Abdullah R and Azali A 2020 Evidence of potent antibacterial effect of fermented papaya leaf against opportunistic skin pathogenic microbes Food Res 4. [CrossRef]

- de Mello M S and Oliveira A C 2021 Challenges for adherence to bacterial resistance actions in large hospitals Rev Bras Enferm 74. [CrossRef]

- Kaidi S, Belattmania Z, Bentiss F, Jama C, Reani A and Sabour B 2022 Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using alginate from the brown seaweed laminaria ochroleuca: Structural features and antibacterial activity Biointerface Res Appl Chem 12. [CrossRef]

- Jia Z, Li J, Gao L, Yang D and Kanaev A 2023 Dynamic Light Scattering: A Powerful Tool for In Situ Nanoparticle Sizing Colloids and Interfaces 7. [CrossRef]

- Alhamadani Y and Oudah A 2022 Study of the Bacterial Sensitivity to different Antibiotics which are isolated from patients with UTI using Kirby-Bauer Method Journal of Biomedicine and Biochemistry. [CrossRef]

- Singhal K K, Mukim M, Dubey C K and Nagar J C 2020 An Updated Review on Pharmacology and Toxicities Related to Chloramphenicol Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research and Development 8. [CrossRef]

- Huffman C F 1959 Dairy Feeds and Drug Additives as Related to Cattle Efficiency and Public Health J Dairy Sci 42. [CrossRef]

- Najafi A, Khoeini M, Khalaj G and Sahebgharan A 2021 Synthesis of silver nanoparticles from electronic scrap by chemical reduction Mater Res Express 8. [CrossRef]

- Zanjage A and Khan S A 2021 Ultra-fast synthesis of antibacterial and photo catalyst silver nanoparticles using neem leaves JCIS Open 3. [CrossRef]

- Subramanyam G K, Gaddam S A, Kotakadi V S, Gunti H, Palithya S, Penchalaneni J and Challagundla V N 2023 Green Fabrication of silver nanoparticles by leaf extract of Byttneria Herbacea Roxb and their promising therapeutic applications and its interesting insightful observations in oral cancer Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 51. [CrossRef]

- Chernii S, Selin R, Tretyakova I, Dovbiy Y, Pekhnyo V, Rotaru A, Chernii V, Kovalska V and Mokhir A 2023 Synthesis and photophysical properties of indolenine styrylcyanine dye and its carboxyl-labeled derivative Biointerface Res Appl Chem 13. [CrossRef]

- Rasheed Z, Alharbi A, Alrakebeh A, Almansour K, Almadi A, Almuzaini A, Salem M, Aloboody B, Alkobair A, Albegami A, Alhomaidan H T, Rasheed N, Alqossayir F M, Musa K H, Hamad E M and Al Abdulmonem W 2022 Thymoquinone provides structural protection of human hemoglobin against oxidative damage: Biochemical studies Biochimie 192. [CrossRef]

- Kiani Nejad Z, Mirzaei-Kalar Z and Khandar A A 2021 Synthesis of ZnFe2O4@SiO2 nanoparticles as a pH-sensitive drug release system and good nano carrier for CT-DNA binding J Mol Liq 339. [CrossRef]

- Seweryn J, Biesdorf J, Boillat P and Schmidt T J 2015 Neutron Radiography of PEM Water Electrolysis Cells ECS Meeting Abstracts MA2015-03. [CrossRef]

- Manconi M, Manca M L, Caddeo C, Cencetti C, di Meo C, Zoratto N, Nacher A, Fadda A M and Matricardi P 2018 Preparation of gellan-cholesterol nanohydrogels embedding baicalin and evaluation of their wound healing activity European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 127. [CrossRef]

- Sacher E 2022 A Pragmatic Perspective of the Initial Stages of the Contact Killing of Bacteria on Copper-Containing Surfaces Appl Microbiol 2. [CrossRef]

- Xiao L, Hui F, Tian T, Yan R, Xin J, Zhao X, Jiang Y, Zhang Z, Kuang Y, Li N, Zhao Y and Lin Q 2021 A Novel Conductive Antibacterial Nanocomposite Hydrogel Dressing for Healing of Severely Infected Wounds Front Chem 9. [CrossRef]

- Ning Q, Wang D, An J, Ding Q, Huang Z, Zou Y, Wu F and You J 2022 Combined effects of nanosized polystyrene and erythromycin on bacterial growth and resistance mutations in Escherichia coli J Hazard Mater 422. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Zhu H, Shen Y, Zhang W and Zhang L 2019 Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles of different particle size against Vibrio Natriegens PLoS One 14. [CrossRef]

- Arip M, Selvaraja M, Mogana R, Tan L F, Leong M Y, Tan P L, Yap V L, Chinnapan S, Tat N C, Abdullah M, Dharmendra K and Jubair N 2022 Review on Plant-Based Management in Combating Antimicrobial Resistance - Mechanistic Perspective Front Pharmacol 13. [CrossRef]

- Mu R, Zhang H, Zhang Z, Li X, Ji J, Wang X, Gu Y and Qin X 2023 Trans-cinnamaldehyde loaded chitosan based nanocapsules display antibacterial and antibiofilm effects against cavity-causing Streptococcus mutans J Oral Microbiol 15. [CrossRef]

- Dreno B, Foulc P, Reynaud A, Moyse D, Habert H and Richet H 2005 Effect of zinc gluconate on propionibacterium acnes resistance to erythromycin in patients with inflammatory acne: In vitro and in vivo study European Journal of Dermatology 15.

- Nakase K, Nakaminami H, Takenaka Y, Hayashi N, Kawashima M and Noguchi N 2017 Propionibacterium acnes is developing gradual increase in resistance to oral tetracyclines J Med Microbiol 66. [CrossRef]

- Pico P, Nathanael K, Lavino A D, Kovalchuk N M, Simmons M J H and Matar O K 2023 Silver nanoparticles synthesis in microfluidic and well-mixed reactors: A combined experimental and PBM-CFD study Chemical Engineering Journal 474. [CrossRef]

- Zabiszak M, Nowak M, Taras-Goslinska K, Kaczmarek M T, Hnatejko Z and Jastrzab R 2018 Carboxyl groups of citric acid in the process of complex formation with bivalent and trivalent metal ions in biological systems J Inorg Biochem 182. [CrossRef]

| Concentration (ppm) | ESN | RSN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter (nm) | PDI | Diameter (nm) | PDI | |

| 10 | 40.3 | 0.0533 | 74 | 0.2848 |

| 30 | 39.9 | 0.0642 | 74.6 | 0.2948 |

| 1 | Chloramphenicol (%) | ESN (ppm) | RSN (ppm) | P two-tail value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 5 | 10 | - | 4.81x10-18 |

| 3 | 5 | 30 | - | 3.91x10-8 |

| 4 | 5 | - | 10 | 2.4 x10-9 |

| 5 | 5 | - | 30 | 4.61x10-16 |

| 6 | - | 10 | 10 | 2.26x10-13 |

| 7 | - | 30 | 30 | 7.91x10-20 |

| 8 | - | 30:10 | - | 3.22x10-14 |

| 9 | - | - | 30:10 | 0.254671 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).