Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

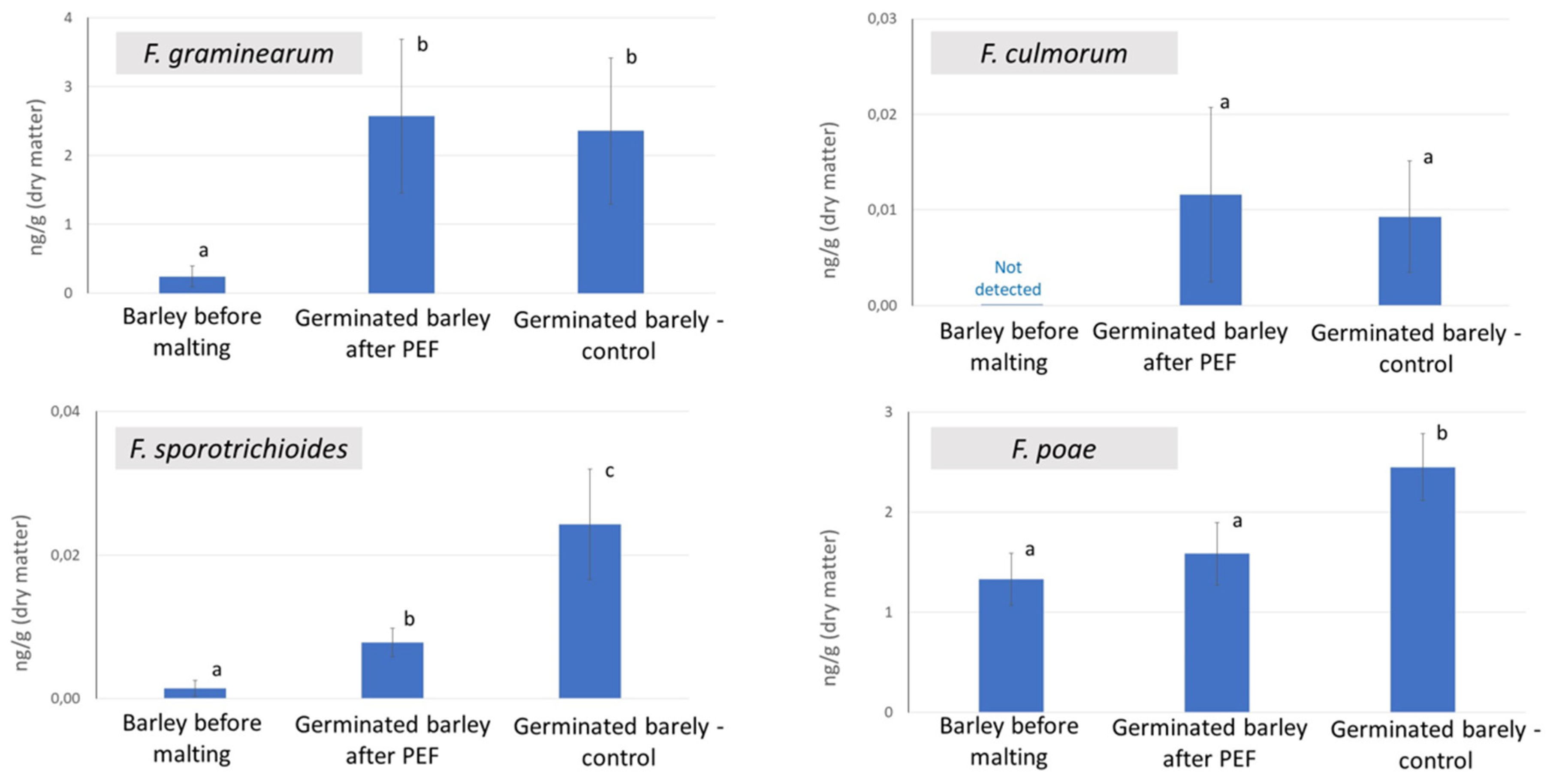

2.1. Analysis of Fusarium Fungi

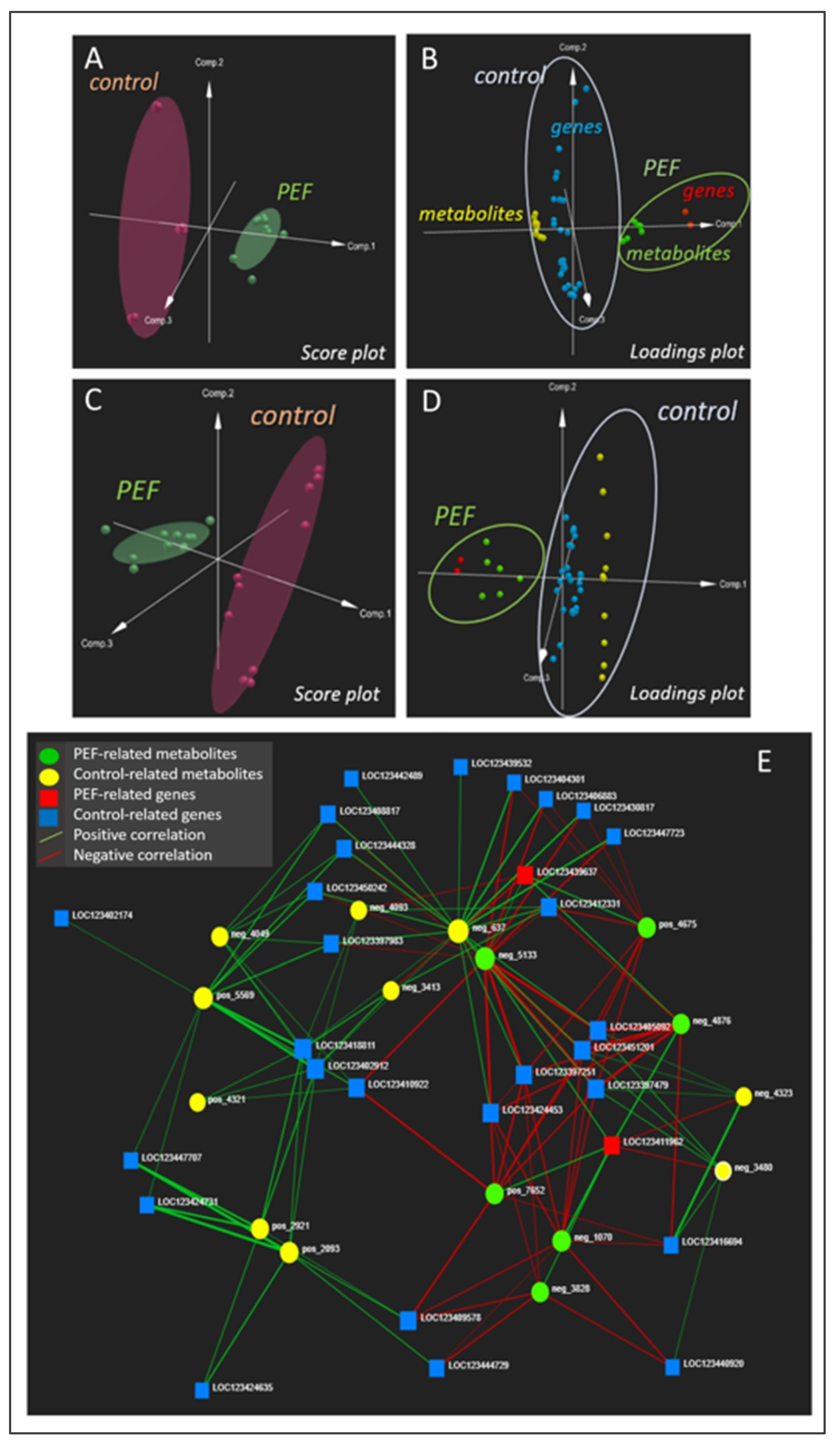

2.2. Multi-omics analysis and data processing

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Material

3.2. PEF Treatment and Barely Malting

3.3. Analysis of Fungal DNA

3.4. RNA Isolation for Transcriptomics

3.5. NGS Analysis and Data Treatment

3.6. Isolation of Metabolites

3.7. Metabolomics Analysis

3.8. Variables Filtration at the Single-Omics Level

3.9. Multi-Omics Data Integration

4. Conclusions

- In the PEF-treated samples, upregulation of gene encoding the vegetative gp1-like protein, previously described as barley protective factor against Fusarium disease and abiotic stress, have been found. At the same time, upregulation of metabolites from the class of flavonoids, (methylsulfanyl)prop-2-enoates, triterpenoid glycosides and indole alkaloids, previously described as important factors in the Fusarium pathogen defense, have been demonstrated. The PEF-induced upregulation of these genes/metabolites is well correlated with the apparent and statistically significant decrease in F. sporotrichioides and F. poae in germinated barley after the PEF treatment.

- On the other hand, overexpression of some Fusarium defense factors was observed also in the control samples. These include the genes encoding ethylene response factor 3-like, putrescine hydroxycinnamoyltransferase 3-like, and dirigent protein 21-like. This trend may be related to the slight increase occurrence of F. culmorum and F. graminearum in germinated barley after the PEF intervention.

- It should be noted that when working with natural material, which naturally contains the representation of several Fusarium species, a clear interpretation of transcriptomic and metabolomic data in relation to the decrease/increase of fungal pathogens is very difficult. To confirm or refute the hypotheses raised on the basis of these pilot correlations and to correctly interpret the biochemical context, follow-up studies that include the variability of the input material (e.g., different barley varieties with different resistance/susceptibility to fungal diseases or different input levels of Fusarium pathogens, ideally single species) need to be performed. Nevertheless, the current study undoubtedly demonstrates the practical application of the recently published protocol of data-driven multi-omics and has provided the first important results on which future follow-up research can be built.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kanehisa Laboratories KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg/.

- Ramirez-Gaona, M.; Marcu, A.; Pon, A.; Guo, A.C.; Sajed, T.; Wishart, N.A.; Karu, N.; Djoumbou Feunang, Y.; Arndt, D.; Wishart, D.S. YMDB 2.0: A Significantly Expanded Version of the Yeast Metabolome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D440–D445, doi:10.1093/nar/gkw1058. [CrossRef]

- Plant Metabolic Network PlantCyc Available online: https://plantcyc.org/.

- SRI International MetaCyc Available online: https://plantcyc.org/.

- Wang, M.; Carver, J.J.; Phelan, V. V; Sanchez, L.M.; Garg, N.; Peng, Y.; Nguyen, D.D.; Watrous, J.; Kapono, C.A.; Luzzatto-Knaan, T.; et al. Sharing and Community Curation of Mass Spectrometry Data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 828–837, doi:10.1038/nbt.3597. [CrossRef]

- Cytoscape Consortium Cytoscape Available online: https://cytoscape.org/.

- Patel, M.K.; Pandey, S.; Kumar, M.; Haque, M.I.; Pal, S.; Yadav, N.S. Plants Metabolome Study: Emerging Tools and Techniques. Plants 2021, 10, doi:10.3390/plants10112409. [CrossRef]

- Vinay, C.M.; Udayamanoharan, S.K.; Prabhu Basrur, N.; Paul, B.; Rai, P.S. Current Analytical Technologies and Bioinformatic Resources for Plant Metabolomics Data. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 15, 561–572, doi:10.1007/s11816-021-00703-3. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.A.; Strack, D. Phytochemistry Meets Genome Analysis, and Beyond. Phytochemistry 2003, 62, 815–816, doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00712-4. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, H.-Z.; Chen, D.-K.; Zeng, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.-L.; Yao, N. PlantMetSuite: A User-Friendly Web-Based Tool for Metabolomics Analysis and Visualisation. Plants 2023, 12, doi:10.3390/plants12152880. [CrossRef]

- Stranska, M.; Uttl, L.; Bechynska, K.; Hurkova, K.; Behner, A.; Hajslova, J. Metabolomic Fingerprinting as a Tool for Authentication of Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.) Biomass Used in Food Production. Food Chem. 2021, 361, 130166, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130166. [CrossRef]

- Lancova, K.; Hajslova, J.; Poustka, J.; Krplova, A.; Zachariasova, M.; Dostalek, P.; Sachambula, L. Transfer of Fusarium Mycotoxins and ‘Masked’ Deoxynivalenol (Deoxynivalenol-3-Glucoside) from Field Barley through Malt to Beer. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2008, 25, 732–744, doi:10.1080/02652030701779625. [CrossRef]

- Prusova, N.; Dzuman, Z.; Jelinek, L.; Karabin, M.; Hajslova, J.; Rychlik, M.; Stranska, M. Free and Conjugated Alternaria and Fusarium Mycotoxins during Pilsner Malt Production and Double-Mash Brewing. Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130926, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130926. [CrossRef]

- Scheibenzuber, S.; Dick, F.; Bretträger, M.; Gastl, M.; Asam, S.; Rychlik, M. Development of Analytical Methods to Study the Effect of Malting on Levels of Free and Modified Forms of Alternaria Mycotoxins in Barley. Mycotoxin Res. 2022, 38, 137–146, doi:10.1007/s12550-022-00455-1. [CrossRef]

- Behner, A.; Palicova, J.; Hirt-Tobolkova, A.; Prusova, N.; Stranska, M. Pulsed Electric Field Induces Significant Changes in the Metabolome of Fusarium Species and Decreases Their Viability and Toxigenicity. Submitt. to Toxins 2024.

- Palicova, J.; Chrpova, J.; Tobolkova, A.; Ovesna, J.; Stranska, M. Effect of Pulsed Electric Field on Viability of Fusarium Micromycetes. Cereal Res. Commun. 2024, doi:10.1007/s42976-024-00561-z. [CrossRef]

- Karabín, M.; Jelínek, L.; Průšová, N.; Ovesná, J.; Stránská, M. Pulsed Electric Field Treatment Applied to Barley before Malting Reduces Fusarium Pathogens without Compromising the Quality of the Final Malt. LWT 2024, 206, 116575, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2024.116575. [CrossRef]

- Bollina, V.; Kumaraswamy, G.K.; Kushalappa, A.C.; Choo, T.M.; Dion, Y.; Rioux, S.; Faubert, D.; Hamzehzarghani, H. Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics Application to Identify Quantitative Resistance-Related Metabolites in Barley against Fusarium Head Blight. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2010, 11, 769–782, doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00643.x. [CrossRef]

- Karre, S.; Kumar, A.; Dhokane, D.; Kushalappa, A.C. Metabolo-Transcriptome Profiling of Barley Reveals Induction of Chitin Elicitor Receptor Kinase Gene (HvCERK1) Conferring Resistance against Fusarium Graminearum. Plant Mol. Biol. 2017, 93, 247–267, doi:10.1007/s11103-016-0559-3. [CrossRef]

- Chamarthi, S.K.; Kumar, K.; Gunnaiah, R.; Kushalappa, A.C.; Dion, Y.; Choo, T.M. Identification of Fusarium Head Blight Resistance Related Metabolites Specific to Doubled-Haploid Lines in Barley. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 138, 67–78, doi:10.1007/s10658-013-0302-8. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, L.; Li, T. Linking Multi-Omics to Wheat Resistance Types to Fusarium Head Blight to Reveal the Underlying Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, doi:10.3390/ijms23042280. [CrossRef]

- Anzano, A.; Bonanomi, G.; Mazzoleni, S.; Lanzotti, V. Plant Metabolomics in Biotic and Abiotic Stress: A Critical Overview. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 503–524, doi:10.1007/s11101-021-09786-w. [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Sun, J.; Shabbir, S.; Khattak, W.A.; Ren, G.; Nie, X.; Bo, Y.; Javed, Q.; Du, D.; Sonne, C. A Review of Plants Strategies to Resist Biotic and Abiotic Environmental Stressors. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 165832, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165832. [CrossRef]

- Prusova, N.; Karabin, M.; Jelinek, L.; Chrpova, J.; Ovesna, J.; Svoboda, P.; Dolezalova, T.; Behner, A.; Hajslova, J.; Stranska, M. Pulsed Electric Field Reduces Fusarium Micromycetes and Mycotoxins during Malting. Toxins, Accepted for publication. 2024.

- Ewald, J.D.; Zhou, G.; Lu, Y.; Kolic, J.; Ellis, C.; Johnson, J.D.; Macdonald, P.E.; Xia, J. Web-Based Multi-Omics Integration Using the Analyst Software Suite. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 1467–1497, doi:10.1038/s41596-023-00950-4. [CrossRef]

- Castro Aviles, A.; Alan Harrison, S.; Joseph Arceneaux, K.; Brown-Guidera, G.; Esten Mason, R.; Baisakh, N. Identification of QTLs for Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight Using a Doubled Haploid Population Derived from Southeastern United States Soft Red Winter Wheat Varieties AGS 2060 and AGS 2035. Genes (Basel). 2020, 11, doi:10.3390/genes11060699. [CrossRef]

- Treutter, D. Significance of Flavonoids in Plant Resistance and Enhancement of Their Biosynthesis. Plant Biol. 2005, 7, 581–591, doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-873009. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Fu, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, X.-N.; San, M.M.; Oo, T.N.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X. Triterpenoids and Their Glycosides from Glinus Oppositifolius with Antifungal Activities against Microsporum Gypseum and Trichophyton Rubrum. Molecules 2019, 24, doi:10.3390/molecules24122206. [CrossRef]

- Wiart, C.; Kathirvalu, G.; Raju, C.S.; Nissapatorn, V.; Rahmatullah, M.; Paul, A.K.; Rajagopal, M.; Sathiya Seelan, J.S.; Rusdi, N.A.; Lanting, S.; et al. Antibacterial and Antifungal Terpenes from the Medicinal Angiosperms of Asia and the Pacific: Haystacks and Gold Needles. Molecules 2023, 28, doi:10.3390/molecules28093873. [CrossRef]

- Ghannoum, M.; Arendrup, M.C.; Chaturvedi, V.P.; Lockhart, S.R.; McCormick, T.S.; Chaturvedi, S.; Berkow, E.L.; Juneja, D.; Tarai, B.; Azie, N.; et al. Ibrexafungerp: A Novel Oral Triterpenoid Antifungal in Development for the Treatment of Candida Auris Infections. Antibiotics 2020, 9, doi:10.3390/antibiotics9090539. [CrossRef]

- Sobiyi, O.K.; Sadgrove, N.J.; Magee, A.R.; Van Wyk, B.-E. The Ethnobotany and Major Essential Oil Compounds of Anise Root (Annesorhiza Species, Apiaceae). South African J. Bot. 2019, 126, 309–316, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2019.07.014. [CrossRef]

- Labbé, C.; Faini, F.; Villagrán, C.; Coll, J.; Rycroft, D.S. Antifungal and Insect Antifeedant 2-Phenylethanol Esters from the Liverwort Balantiopsis Cancellata from Chile. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 247–249, doi:10.1021/jf048935c. [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Magwanga, R.O.; Guo, X.; Kirungu, J.N.; Lu, H.; Cai, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion (MATE) Family in Gossypium Raimondii and Gossypium Arboreum and Its Expression Analysis Under Salt, Cadmium, and Drought Stress. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2018, 8, 2483–2500, doi:10.1534/g3.118.200232. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Lim, C.W.; Lee, S.C. The Pepper Late Embryogenesis Abundant Protein, CaDIL1, Positively Regulates Drought Tolerance and ABA Signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01301. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Liu, D.; Sun, J.; Tao, J. Herbaceous Peony Tryptophan Decarboxylase Confers Drought and Salt Stresses Tolerance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 162, 345–356, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.03.013. [CrossRef]

- Candat, A.; Paszkiewicz, G.; Neveu, M.; Gautier, R.; Logan, D.C.; Avelange-Macherel, M.-H.; Macherel, D. The Ubiquitous Distribution of Late Embryogenesis Abundant Proteins across Cell Compartments in Arabidopsis Offers Tailored Protection against Abiotic Stress. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 3148–3166, doi:10.1105/tpc.114.127316. [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, K.E.; Nishimura, N.; Hitomi, K.; Getzoff, E.D.; Schroeder, J.I. Early Abscisic Acid Signal Transduction Mechanisms: Newly Discovered Components and Newly Emerging Questions. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 1695–1708, doi:10.1101/gad.1953910. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Luan, S. ABA Signal Transduction at the Crossroad of Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses. Plant. Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 53–60, doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02426.x. [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.M.; Melcher, K.; Teh, B.T.; Xu, H.E. Abscisic Acid Perception and Signaling: Structural Mechanisms and Applications. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2014, 35, 567–584, doi:10.1038/aps.2014.5. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.R.; Varela, C.L.; Pires, A.S.; Tavares-da-Silva, E.J.; Roleira, F.M.F. Synthetic and Natural Guanidine Derivatives as Antitumor and Antimicrobial Agents: A Review. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 138, 106600, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2023.106600. [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Polyamines and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 26–33, doi:10.4161/psb.5.1.10291. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Deng, L.; Meng, J.; Niu, L.; Pan, L.; Lu, Z.; Cui, G.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, W. Transcriptomic and Metabolic Analyses Reveal the Mechanism of Ethylene Production in Stony Hard Peach Fruit during Cold Storage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, doi:10.3390/ijms222111308. [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, G.J.; Mao, Q.; Yan, Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y.; Ren, J.; Guo, P.; Liu, A.; Chen, S. Role of Melatonin in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi-Induced Resistance to Fusarium Wilt in Cucumber. Phytopathology® 2020, 110, 999–1009, doi:10.1094/PHYTO-11-19-0435-R. [CrossRef]

- Berrocal-Lobo, M.; Molina, A. Ethylene Response Factor 1 Mediates Arabidopsis Resistance to the Soilborne Fungus Fusarium Oxysporum. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2004, 17, 763–770, doi:10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.7.763. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Li, R.; Yang, J.; Yao, Z.; Cao, S. Ethylene Response Factor ERF022 Is Involved in Regulating Arabidopsis Root Growth. Plant Mol. Biol. 2023, 113, 1–17, doi:10.1007/s11103-023-01373-1. [CrossRef]

- Pilate, G.; Dejardin, A.; Leple, J.-C. Chapter 1 - Field Trials with Lignin-Modified Transgenic Trees. Lignins 2012, 61, 1–36, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-416023-1.00001-X. [CrossRef]

- Shadle, G.; Chen, F.; Srinivasa Reddy, M.S.; Jackson, L.; Nakashima, J.; Dixon, R.A. Down-Regulation of Hydroxycinnamoyl CoA: Shikimate Hydroxycinnamoyl Transferase in Transgenic Alfalfa Affects Lignification, Development and Forage Quality. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 1521–1529, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.03.022. [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, C.; Bilkova, A.; Jackson, P.; Dabravolski, S.; Riber, W.; Didi, V.; Houser, J.; Gigli-Bisceglia, N.; Wimmerova, M.; Budínská, E.; et al. Dirigent Proteins in Plants: Modulating Cell Wall Metabolism during Abiotic and Biotic Stress Exposure. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 3287–3301, doi:10.1093/jxb/erx141. [CrossRef]

- Gasper, R.; Effenberger, I.; Kolesinski, P.; Terlecka, B.; Hofmann, E.; Schaller, A. Dirigent Protein Mode of Action Revealed by the Crystal Structure of AtDIR6. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 2165–2175, doi:10.1104/pp.16.01281. [CrossRef]

- Naguib, D.M. Comparative Lipid Profiling for Studying Resistance Mechanism against Fusarium Wilt. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019, 108, 101421, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmpp.2019.101421. [CrossRef]

- Reyna, M.; Peppino Margutti, M.; Villasuso, A.L. Lipid Profiling of Barley Root in Interaction with Fusarium Macroconidia. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 166, 103788, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.06.001. [CrossRef]

- Kuźniak, E.; Gajewska, E. Lipids and Lipid-Mediated Signaling in Plant–Pathogen Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, doi:10.3390/ijms25137255. [CrossRef]

- Stranska, M.; Lovecka, P.; Vrchotova, B.; Uttl, L.; Bechynska, K.; Behner, A.; Hajslova, J. Bacterial Endophytes from Vitis Vinifera L. – Metabolomics Characterization of Plant-Endophyte Crosstalk. Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, e2100516, doi:10.1002/cbdv.202100516. [CrossRef]

| Gene No | PEF-induced upregulation/downregulation | Gene ID | Gene interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PEF-related | LOC123411962 | vegetative cell wall protein gp1-like |

| 2 | PEF-related | LOC123439637 | late embryogenesis abundant protein (LEA) EMB564-like |

| 3 | Control-related | LOC123440920 | metallothionein like protein |

| 4 | Control-related | LOC123416694 | ethylene responce factor C3-like |

| 5 | Control-related | LOC123405092 | putrescine hydroxycinnamoyltransferase 3-like |

| 6 | Control-related | LOC123451201 | dirigent protein 21-like |

| 7 | Control-related | LOC123397479 | small polypeptide DEVIL 5-like |

| 8 | Control-related | LOC123412331 | metallothionein like protein |

| 9 | Control-related | LOC123418811 | cytochrom b561 and DOMON domain containing protein |

| 10 | Control-related | LOC123402912 | putative cell wall protein |

| 11 | Control-related | LOC123410922 | codeine O-demethylase-like |

| 12 | Control-related | LOC123444328 | subtilisin-like protease SBT 5.6 |

| 13 | Control-related | LOC123397983 | pectin esterase-like |

| 14 | Control-related | LOC123408817 | skin secretory protein xP2-like |

| 15 | Control-related | LOC123450242 | xyloglucan endotransglycosilase |

| 16 | Control-related | LOC123430817 | 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase 12-like |

| 17 | Control-related | LOC123404301 | phosphoribulokinase |

| 18 | Control-related | LOC123447723 | calmodulin calcium-dependent NAD kinase |

| 19 | Control-related | LOC123406883 | peroxidase 5-like |

| 20 | Control-related | LOC123442489 | lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase 1-like |

| 21 | Control-related | LOC123439532 | acyl transferase 7-like |

| 22 | Control-related | LOC123424453 | indole-2 monooxygenase-like |

| 23 | Control-related | LOC123397251 | protein BIG grain 1-like |

| 24 | Control-related | LOC123424731 | peroxidase 2-like |

| 25 | Control-related | LOC123447707 | photosystem II reaction center W protein |

| 26 | Control-related | LOC123424635 | senescene associated gene 20-like |

| 27 | Control-related | LOC123444729 | expansin A2 |

| 28 | Control-related | LOC123409578 | pathogenesis related protein 1-like |

| 29 | Control-related | LOC123402174 | photosystem II 5 kDa protein, chloroplastic like |

| Met. No | Trend | Met. ID | Summary formula | Systematic name | Onthology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PEF-related | neg_3828 | C32H22O10 | (1) | flavonoid derivative |

| 2 | PEF-related | neg_1070 | C12H14O3S | (2) | (methylsulfanyl)prop-2-enoate derivative |

| 3 | PEF-related | pos_7652 | C39H66O8 | (3) | triterpenoid glycoside derivative |

| 4 | PEF-related | pos_4675 | C24H27N3O4S | (4) | tetrahydroisoquinoline derivative |

| 5 | PEF-related | neg_4876 | C35H52N4O6 | (5) | methylguanidine derivative |

| 6 | PEF-related | neg_5133 | C42H54N4O5 | (6) | indole derivative |

| 7 | Control-related | neg_3480 | C27H46NO7P | (7) | phospholipide |

| 8 | Control-related | neg_4323 | C35H69NO4 | (8) | ceramide |

| 9 | Control-related | neg_4093 | C35H63N2O3P | (9) | phosphorous acid derivative |

| 10 | Control-related | neg_4049 | C32H56N6O4 | (10) | N-acylpiperidines |

| 11 | Control-related | neg_3413 | C27H46N6O4 | (11) | piperidinecarboxamide derivative |

| 12 | Control-related | neg_637 | C8H20N2O5 | (12) | aminoalcohol |

| 13 | Control-related | pos_2093 | C17H32O3 | (13) | sesquiterpenoid derivative |

| 14 | Control-related | pos_2921 | C19H28N2O4 | (14) | phenylmethylamine derivative |

| 15 | Control-related | pos_4321 | C43H68N8O10 | (15) | cyclic depsipeptide derivative |

| 16 | Control-related | pos_5569 | C34H53NO4 | (16) | prostaglandin derivative |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).