Submitted:

05 December 2023

Posted:

07 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Maintenance and Cultivation of Bacteria

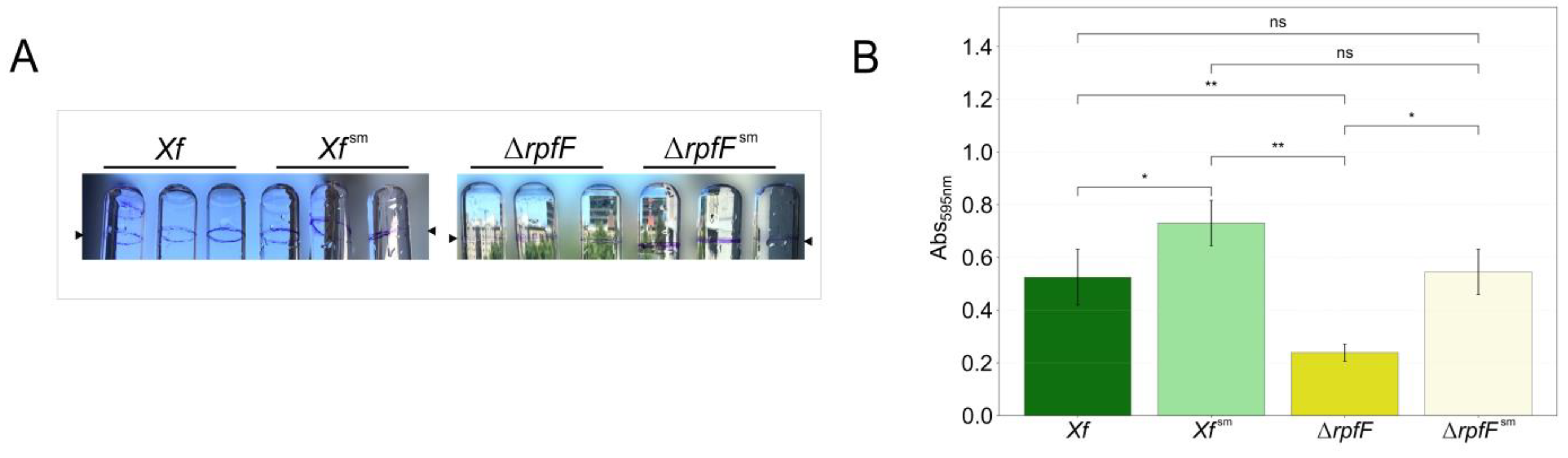

X. fastidiosa Biofilm Measurement

Analysis of Metabolites of the Supernatant of X. fastidiosa Cultures by Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

LCMS Data Processing and Analysis

Integration of Metabolites and Gene Set for Functional Annotation of Exometabolomes

Bioinformatic Analysis

Cooperative Metabolic Interactions between X. fastidiosa and P. phytofirmans

3. Results

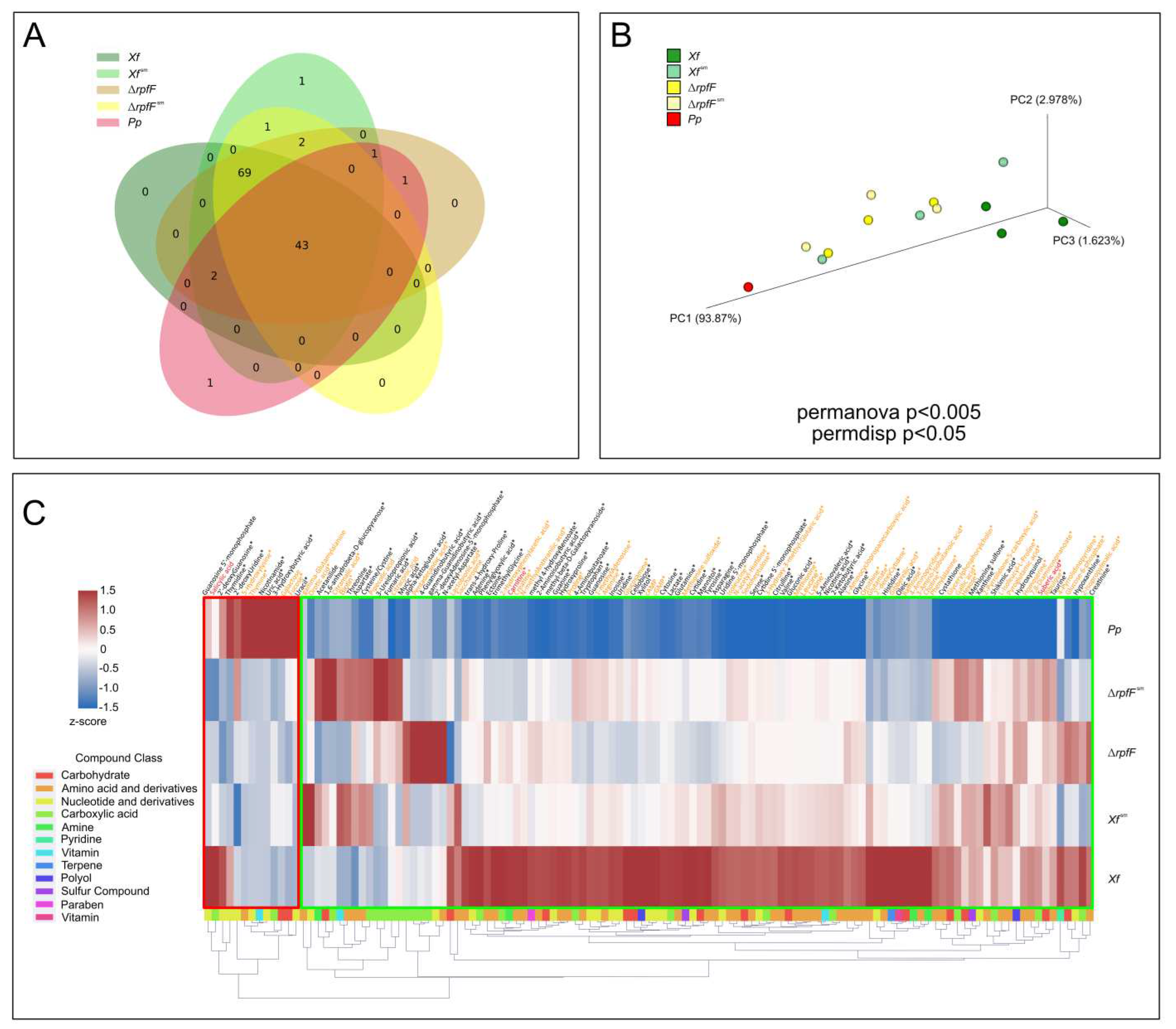

P. phytofirmans Interacts with X. fastidiosa through its Exometabolome

Exometabolome Variation among X. fastidiosa Strains in Response to P. phytofirmans

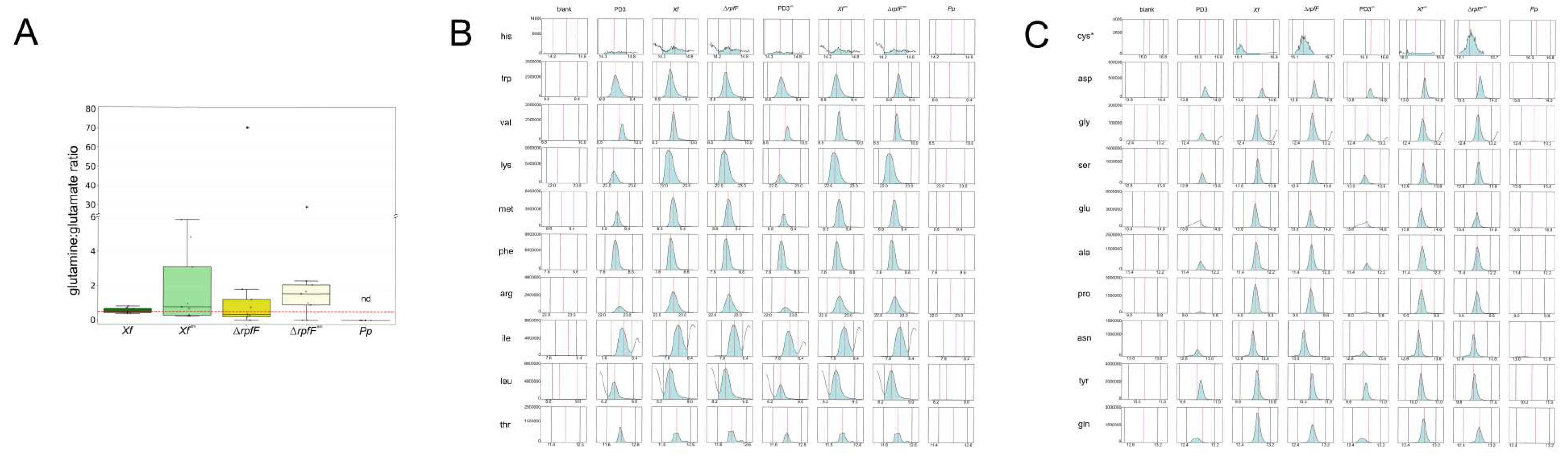

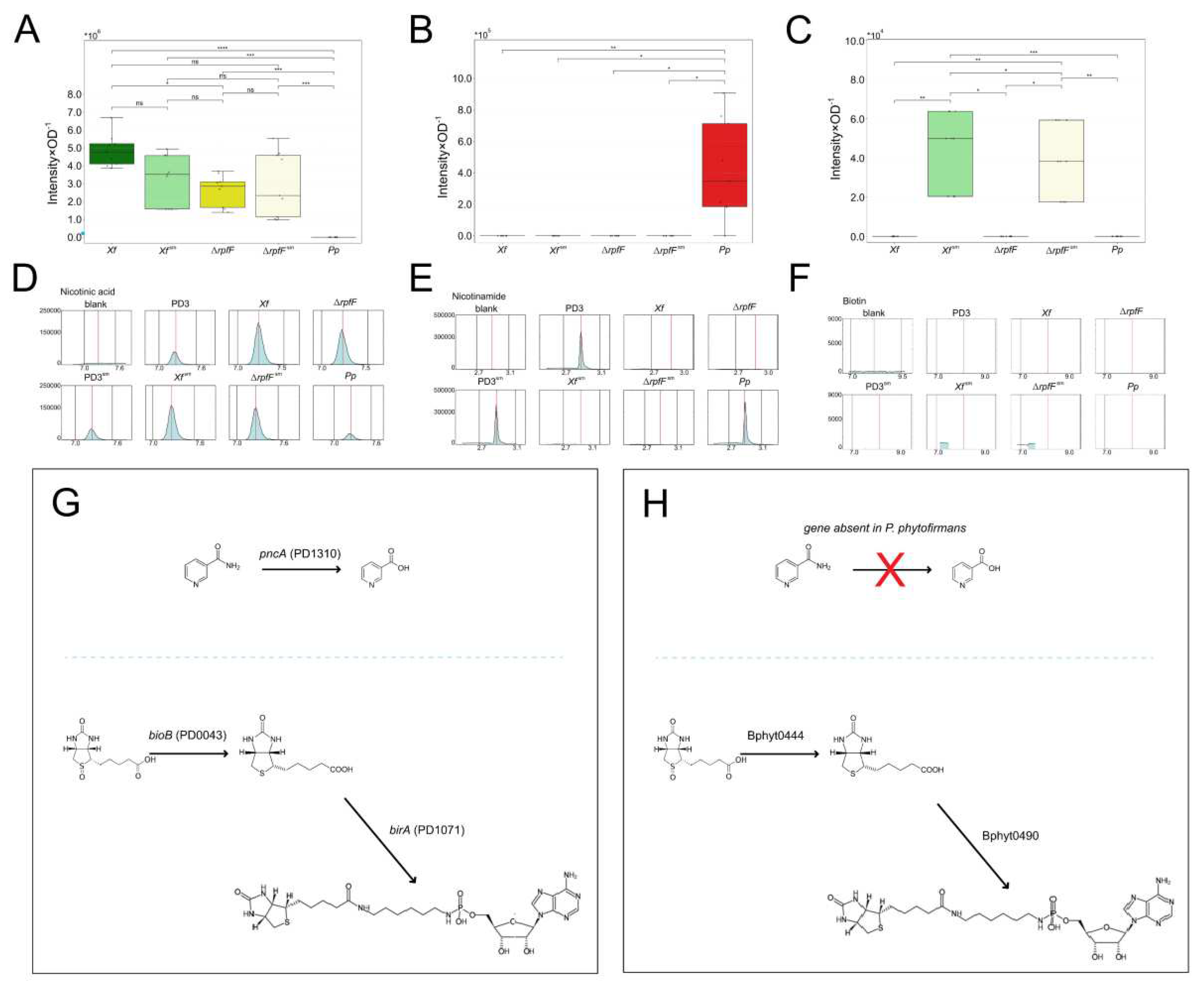

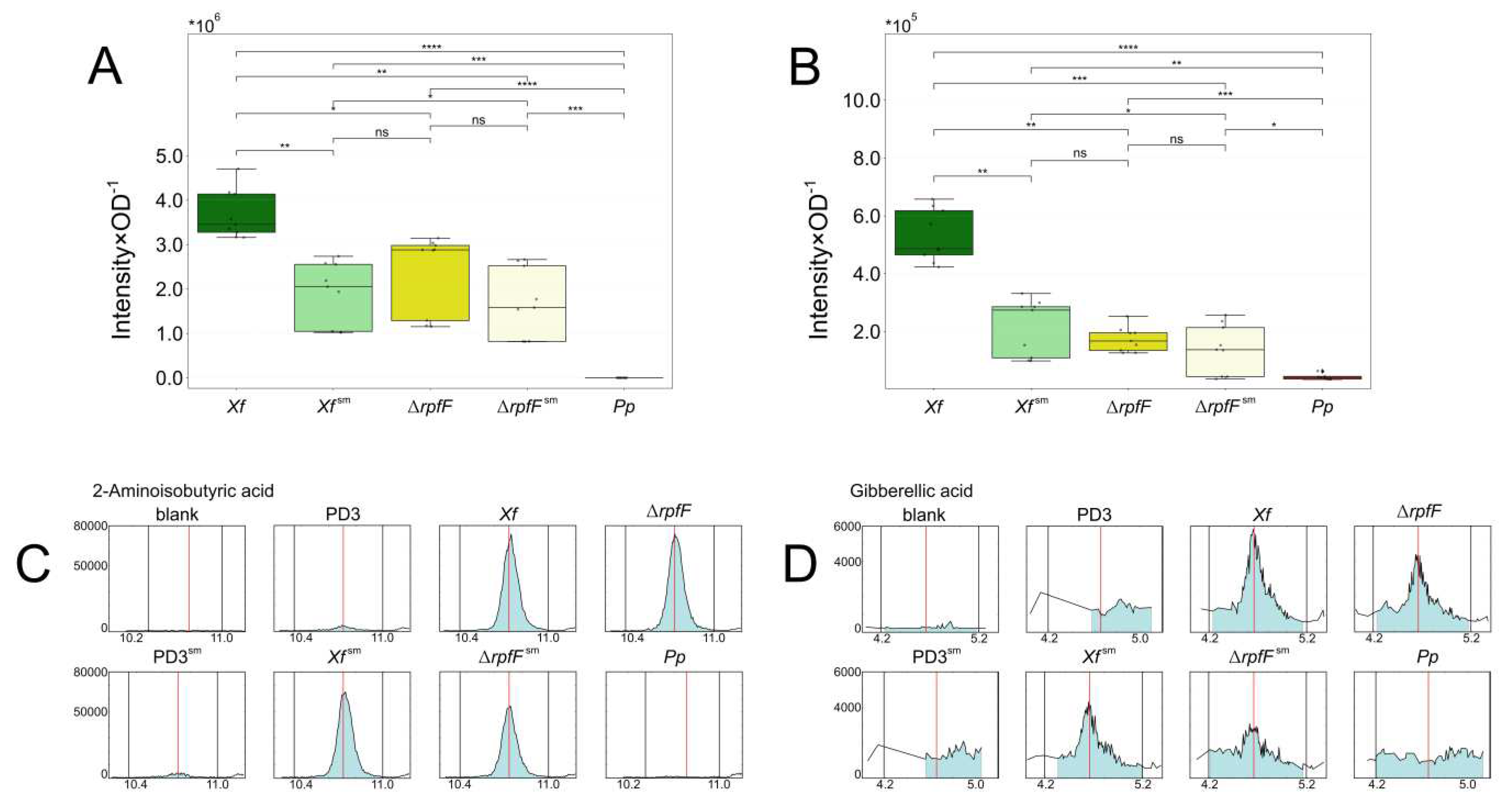

X. fastidiosa Secretes High Amounts of Amino Acids and Vitamins

Two Plant Hormones are Exclusively Secreted by X. fastidiosa

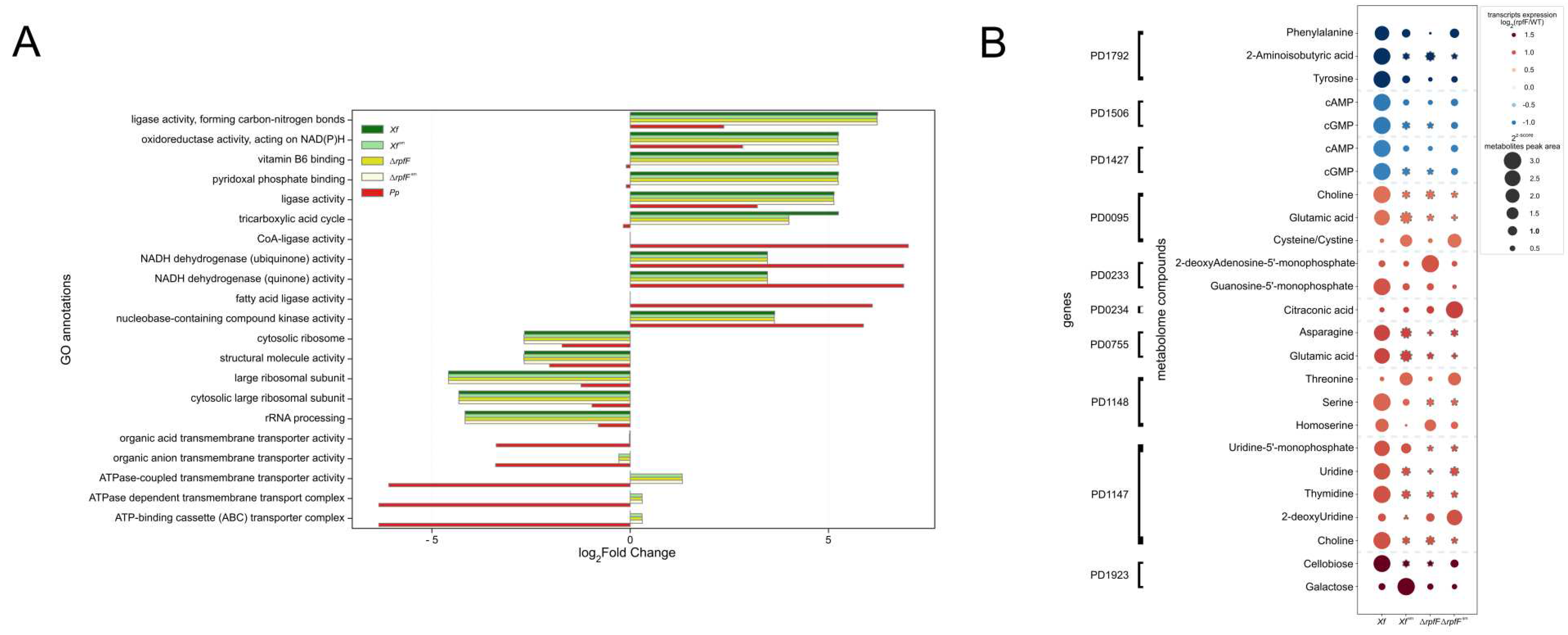

Exometabolome, genome, and transcriptome integration for X. fastidiosa and P. phytofirmans

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sicard, A.; Zeilinger, A. R.; Vanhove, M.; Schartel, T. E.; Beal, D. J.; Daugherty, M. P.; Almeida, R. P. P., Xylella fastidiosa: Insights into an Emerging Plant Pathogen. Annual Review of Phytopathology, Vol 56 2018, 56, 181-202.

- Chatterjee, S.; Almeida, R. P.; Lindow, S., Living in two worlds: the plant and insect lifestyles of Xylella fastidiosa. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2008, 46, 243-71. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Li, J. L.; Lindow, S. E., RpfF-dependent regulon of Xylella fastidiosa. Phytopathology 2012, 102, (11), 1045-53. [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, M.; Yokota, K.; Antonova, E.; Garcia, A.; Beaulieu, E.; Hayes, T.; Iavarone, A. T.; Lindow, S. E., Promiscuous Diffusible Signal Factor Production and Responsiveness of the Xylella fastidiosa Rpf System. MBio 2016, 7, (4).

- Roper, C.; Castro, C.; Ingel, B., Xylella fastidiosa: bacterial parasitism with hallmarks of commensalism. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2019, 50, 140-147. [CrossRef]

- Rapicavoli, J.; Ingel, B.; Blanco-Ulate, B.; Cantu, D.; Roper, C., Xylella fastidiosa: an examination of a re-emerging plant pathogen. Mol Plant Pathol 2018, 19, (4), 786-800. [CrossRef]

- Morris, C. E.; Moury, B., Revisiting the Concept of Host Range of Plant Pathogens. Annual Review of Phytopathology, Vol 57, 2019 2019, 57, 63-90.

- Parniske, M., Uptake of bacteria into living plant cells, the unifying and distinct feature of the nitrogen-fixing root nodule symbiosis. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2018, 44, 164-174. [CrossRef]

- Nagel, R.; Turrini, P. C.; Nett, R. S.; Leach, J. E.; Verdier, V.; Van Sluys, M. A.; Peters, R. J., An operon for production of bioactive gibberellin A(4) phytohormone with wide distribution in the bacterial rice leaf streak pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola. New Phytol 2017, 214, (3), 1260-1266. [CrossRef]

- Ankrah, N. Y. D.; Wilkes, R. A.; Zhang, F. Q.; Aristilde, L.; Douglas, A. E., The Metabolome of Associations between Xylem-Feeding Insects and their Bacterial Symbionts. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2020, 46, (8), 735-744. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Masoudi, A.; Li, H.; Gu, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, M.; Yu, Z.; Liu, J., Microbial community structure and niche differentiation under different health statuses of Pinus bungeana in the Xiong'an New Area in China. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 913349. [CrossRef]

- De Silva, N. I.; Brooks, S.; Lumyong, S.; Hyde, K. D., Use of endophytes as biocontrol agents. Fungal Biol Rev 2019, 33, (2), 133-148. [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, L. L.; Allard, P. M.; Dilarri, G.; Codesido, S.; Gonzalez-Ruiz, V.; Queiroz, E. F.; Ferreira, H.; Wolfender, J. L., Metabolomic- and Molecular Networking-Based Exploration of the Chemical Responses Induced in Citrus sinensis Leaves Inoculated with Xanthomonas citri. J Agr Food Chem 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ryffel, F.; Helfrich, E. J. N.; Kiefer, P.; Peyriga, L.; Portais, J. C.; Piel, J.; Vorholt, J. A., Metabolic footprint of epiphytic bacteria on Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. Isme J 2016, 10, (3), 632-643. [CrossRef]

- Zaini, P. A.; Nascimento, R.; Gouran, H.; Cantu, D.; Chakraborty, S.; Phu, M.; Goulart, L. R.; Dandekar, A. M., Molecular Profiling of Pierce's Disease Outlines the Response Circuitry of Vitis vinifera to Xylella fastidiosa Infection. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 771. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. L.; Sun, M. C.; Chong, S. L.; Si, J. P.; Wu, L. S., Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Approaches Deepen Our Knowledge of Plant-Endophyte Interactions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Cariddi, C.; Saponari, M.; Boscia, D.; De Stradis, A.; Loconsole, G.; Nigro, F.; Porcelli, F.; Potere, O.; Martelli, G. P., Isolation of a Xylella fastidiosa strain infecting olive and oleander in Apulia, Italy. J Plant Pathol 2014, 96, (2), 425-429.

- Desprez-Loustau, M.-L.; Balci, Y.; Cornara, D.; Gonthier, P.; Robin, C.; Jacques, M.-A., Is Xylella fastidiosa a serious threat to European forests? Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research 2020, 94, (1), 1-17.

- Krugner, R.; Sisterson, M. S.; Backus, E. A.; Burbank, L. P.; Redak, R. A., Sharpshooters: a review of what moves Xylella fastidiosa. Austral Entomol 2019, 58, (2), 248-267. [CrossRef]

- Saponari, M.; Loconsole, G.; Cornara, D.; Yokomi, R. K.; De Stradis, A.; Boscia, D.; Bosco, D.; Martelli, G. P.; Krugner, R.; Porcelli, F., Infectivity and transmission of Xylellua fastidiosa by Philaenus spumarius (Hemiptera: Aphrophoridae) in Apulia, Italy. J Econ Entomol 2014, 107, (4), 1316-9. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. J.; Reyes-Caldas, P.; Mann, M.; Seifbarghi, S.; Kahn, A.; Almeida, R. P. P.; Béven, L.; Heck, M.; Hogenhout, S. A.; Coaker, G., Bacterial Vector-Borne Plant Diseases: Unanswered Questions and Future Directions. Molecular Plant 2020, 13, (10), 1379-1393. [CrossRef]

- Roper, M. C.; Greve, L. C.; Warren, J. G.; Labavitch, J. M.; Kirkpatrick, B. C., Xylella fastidiosa requires polygalacturonase for colonization and pathogenicity in Vitis vinifera grapevines. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2007, 20, (4), 411-419.

- Nascimento, R.; Gouran, H.; Chakraborty, S.; Gillespie, H. W.; Almeida-Souza, H. O.; Tu, A.; Rao, B. J.; Feldstein, P. A.; Bruening, G.; Goulart, L. R.; Dandekar, A. M., The Type II Secreted Lipase/Esterase LesA is a Key Virulence Factor Required for Xylella fastidiosa Pathogenesis in Grapevines (vol 6, 18598, 2016). Sci Rep-Uk 2016, 6.

- Feitosa, O. R.; Stefanello, E.; Zaini, P. A.; Nascimento, R.; Pierry, P. M.; Dandekar, A. M.; Lindow, S. E.; da Silva, A. M., Proteomic and Metabolomic Analyses of Xylella fastidiosa OMV-Enriched Fractions Reveal Association with Virulence Factors and Signaling Molecules of the DSF Family. Phytopathology 2019, 109, (8), 1344-1353. [CrossRef]

- Block, A.; Li, G. Y.; Fu, Z. Q.; Alfano, J. R., Phytopathogen type III effector weaponry and their plant targets. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2008, 11, (4), 396-403. [CrossRef]

- Kvitko, B. H.; Collmer, A., Discovery of the Hrp Type III Secretion System in Phytopathogenic Bacteria: How Investigation of Hypersensitive Cell Death in Plants Led to a Novel Protein Injector System and a World of Inter-Organismal Molecular Interactions Within Plant Cells. Phytopathology 2023. [CrossRef]

- Van Sluys, M. A.; Monteiro-Vitorello, C. B.; Camargo, L. E.; Menck, C. F.; Da Silva, A. C.; Ferro, J. A.; Oliveira, M. C.; Setubal, J. C.; Kitajima, J. P.; Simpson, A. J., Comparative genomic analysis of plant-associated bacteria. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2002, 40, 169-89. [CrossRef]

- De La Fuente, L.; Merfa, M. V.; Cobine, P. A.; Coleman, J. J., Pathogen Adaptation to the Xylem Environment. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2022, 60, 163-186. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawana, A.; Adeolu, M.; Gupta, R. S., Molecular signatures and phylogenomic analysis of the genus Burkholderia: proposal for division of this genus into the emended genus Burkholderia containing pathogenic organisms and a new genus Paraburkholderia gen. nov. harboring environmental species. Front Genet 2014, 5, 429. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessitsch, A.; Coenye, T.; Sturz, A. V.; Vandamme, P.; Barka, E. A.; Salles, J. F.; Van Elsas, J. D.; Faure, D.; Reiter, B.; Glick, B. R.; Wang-Pruski, G.; Nowak, J., Burkholderia phytofirmans sp. nov., a novel plant-associated bacterium with plant-beneficial properties. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology 2005, 55, 1187-1192.

- Mitter, B.; Petric, A.; Shin, M. W.; Chain, P. S.; Hauberg-Lotte, L.; Reinhold-Hurek, B.; Nowak, J.; Sessitsch, A., Comparative genome analysis of Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN reveals a wide spectrum of endophytic lifestyles based on interaction strategies with host plants. Front Plant Sci 2013, 4, 120. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miotto-Vilanova, L.; Jacquard, C.; Courteaux, B.; Wortham, L.; Michel, J.; Clement, C.; Barka, E. A.; Sanchez, L., Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN Confers Grapevine Resistance against Botrytis cinerea via a Direct Antimicrobial Effect Combined with a Better Resource Mobilization. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 1236. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baccari, C.; Antonova, E.; Lindow, S., Biological Control of Pierce's Disease of Grape by an Endophytic Bacterium. Phytopathology 2019, 109, (2), 248-256. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindow, S.; Koutsoukis, R.; Meyer, K. M.; Baccari, C., Control of Pierce's disease of grape with Paraburkholderia phytofirmans PsJN in the field. Phytopathology 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sue, T.; Obolonkin, V.; Griffiths, H.; Villas-Boas, S. G., An Exometabolomics Approach to Monitoring Microbial Contamination in Microalgal Fermentation Processes by Using Metabolic Footprint Analysis. Appl Environ Microb 2011, 77, (21), 7605-7610. [CrossRef]

- Drenos, F., Mechanistic insights from combining genomics with metabolomics. Curr Opin Lipidol 2017, 28, (2), 99-103. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Bao, Z. X.; Zhao, P. J.; Li, G. H., Advances in the Study of Metabolomics and Metabolites in Some Species Interactions. Molecules 2021, 26, (11).

- Villas-Boas, S. G.; Noel, S.; Lane, G. A.; Attwood, G.; Cookson, A., Extracellular metabolomics: a metabolic footprinting approach to assess fiber degradation in complex media. Analytical biochemistry 2006, 349, (2), 297-305. [CrossRef]

- Villas-Boas, S. G.; Mas, S.; Akesson, M.; Smedsgaard, J.; Nielsen, J., Mass spectrometry in metabolome analysis. Mass Spectrom Rev 2005, 24, (5), 613-46. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, K. L.; Almeida, R. P.; Purcell, A. H.; Lindow, S. E., Use of a green fluorescent strain for analysis of Xylella fastidiosa colonization of Vitis vinifera. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003, 69, (12), 7319-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, K. L.; Almeida, R. P. P.; Purcell, A. H.; Lindow, S. E., Cell-cell signaling controls Xylella fastidiosa interactions with both insects and plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101, (6), 1737-1742. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frommel, M. I.; Nowak, J.; Lazarovits, G., Growth Enhancement and Developmental Modifications of in Vitro Grown Potato (Solanum tuberosum spp. tuberosum) as Affected by a Nonfluorescent Pseudomonas sp. Plant Physiol 1991, 96, (3), 928-36.

- Weilharter, A.; Mitter, B.; Shin, M. V.; Chain, P. S. G.; Nowak, J.; Sessitsch, A., Complete Genome Sequence of the Plant Growth-Promoting Endophyte Burkholderia phytofirmans Strain PsJN. J Bacteriol 2011, 193, (13), 3383-3384. [CrossRef]

- King, E. O.; Ward, M. K.; Raney, D. E., Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. J Lab Clin Med 1954, 44, (2), 301-7.

- Zaini, P. A.; De La Fuente, L.; Hoch, H. C.; Burr, T. J., Grapevine xylem sap enhances biofilm development by Xylella fastidiosa. FEMS microbiology letters 2009, 295, (1), 129-134. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, B. P.; Northen, T. R., Dealing with the unknown: metabolomics and metabolite atlases. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2010, 21, (9), 1471-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Sun, T.; Wang, T.; Ruebel, O.; Northen, T.; Bowen, B. P., Analysis of Metabolomics Datasets with High-Performance Computing and Metabolite Atlases. Metabolites 2015, 5, (3), 431-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumner, L. W.; Amberg, A.; Barrett, D.; Beale, M. H.; Beger, R.; Daykin, C. A.; Fan, T. W. M.; Fiehn, O.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J. L.; Hankemeier, T.; Hardy, N.; Harnly, J.; Higashi, R.; Kopka, J.; Lane, A. N.; Lindon, J. C.; Marriott, P.; Nicholls, A. W.; Reily, M. D.; Thaden, J. J.; Viant, M. R., Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis. Metabolomics 2007, 3, (3), 211-221. [CrossRef]

- Gower, J. C., Some Distance Properties of Latent Root and Vector Methods Used in Multivariate Analysis. Biometrika 1966, 53, 325-&. [CrossRef]

- Erbilgin, O.; Rubel, O.; Louie, K. B.; Trinh, M.; Raad, M.; Wildish, T.; Udwary, D.; Hoover, C.; Deutsch, S.; Northen, T. R.; Bowen, B. P., MAGI: A Method for Metabolite Annotation and Gene Integration. ACS Chem Biol 2019, 14, (4), 704-714. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkel, D., Docker: lightweight linux containers for consistent development and deployment. Linux journal 2014, 2014, 2.

- Gotz, S.; Garcia-Gomez, J. M.; Terol, J.; Williams, T. D.; Nagaraj, S. H.; Nueda, M. J.; Robles, M.; Talon, M.; Dopazo, J.; Conesa, A., High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36, (10), 3420-3435. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoriev, I. V.; Nordberg, H.; Shabalov, I.; Aerts, A.; Cantor, M.; Goodstein, D.; Kuo, A.; Minovitsky, S.; Nikitin, R.; Ohm, R. A.; Otillar, R.; Poliakov, A.; Ratnere, I.; Riley, R.; Smirnova, T.; Rokhsar, D.; Dubchak, I., The genome portal of the Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, (Database issue), D26-32. [CrossRef]

- Delcher, A. L.; Phillippy, A.; Carlton, J.; Salzberg, S. L., Fast algorithms for large-scale genome alignment and comparison. Nucleic Acids Res 2002, 30, (11), 2478-2483. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelini, S.; Balakrishnan, B.; Parolo, S.; Matone, A.; Mullaney, J. A.; Young, W.; Gasser, O.; Wall, C.; Priami, C.; Lombardo, R.; Kussmann, M., A reverse metabolic approach to weaning: in silico identification of immune-beneficial infant gut bacteria, mining their metabolism for prebiotic feeds and sourcing these feeds in the natural product space. Microbiome 2018, 6, (1), 171. [CrossRef]

- Levy, R.; Borenstein, E., Reverse Ecology: from systems to environments and back. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012, 751, 329-45. [PubMed]

- Carr, R.; Borenstein, E., NetSeed: a network-based reverse-ecology tool for calculating the metabolic interface of an organism with its environment. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, (5), 734-5. [CrossRef]

- Levy, R.; Borenstein, E., Metabolic modeling of species interaction in the human microbiome elucidates community-level assembly rules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, (31), 12804-9. [CrossRef]

- Kreimer, A.; Doron-Faigenboim, A.; Borenstein, E.; Freilich, S., NetCmpt: a network-based tool for calculating the metabolic competition between bacterial species. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, (16), 2195-7. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T. J.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S. Q.; Li, Q. L.; Shoemaker, B. A.; Thiessen, P. A.; Yu, B.; Zaslavsky, L.; Zhang, J.; Bolton, E. E., PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, G. M.; Moran, N. A., Heritable symbiosis: The advantages and perils of an evolutionary rabbit hole. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, (33), 10169-76. [CrossRef]

- Flynn, K. J.; Dickson, D. M. J.; Al-Amoudi, O. A., The ratio of glutamine:glutamate in microalgae: a biomarker for N-status suitable for use at natural cell densities. Journal of Plankton Research 1989, 11, (1), 165-170. [CrossRef]

- Hibi, M.; Fukuda, D.; Kenchu, C.; Nojiri, M.; Hara, R.; Takeuchi, M.; Aburaya, S.; Aoki, W.; Mizutani, K.; Yasohara, Y.; Ueda, M.; Mikami, B.; Takahashi, S.; Ogawa, J., A three-component monooxygenase from Rhodococcus wratislaviensis may expand industrial applications of bacterial enzymes. Commun Biol 2021, 4, (1).

- Salazar-Cerezo, S.; Martinez-Montiel, N.; Garcia-Sanchez, J.; Perez, Y. T. R.; Martinez-Contreras, R. D., Gibberellin biosynthesis and metabolism: A convergent route for plants, fungi and bacteria. Microbiol Res 2018, 208, 85-98. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, P.; Morgat, A.; Axelsen, K. B.; Muthukrishnan, V.; Coudert, E.; Aimo, L.; Hyka-Nouspikel, N.; Gasteiger, E.; Kerhornou, A.; Neto, T. B.; Pozzato, M.; Blatter, M. C.; Ignatchenko, A.; Redaschi, N.; Bridge, A., Rhea, the reaction knowledgebase in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, (D1), D693-D700. [CrossRef]

- Caspi, R.; Billington, R.; Keseler, I. M.; Kothari, A.; Krummenacker, M.; Midford, P. E.; Ong, W. K.; Paley, S.; Subhraveti, P.; Karp, P. D., The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes - a 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, (D1), D445-D453. [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C. A.; Blake, J. A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J. M.; Davis, A. P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S. S.; Eppig, J. T.; Harris, M. A.; Hill, D. P.; Issel-Tarver, L.; Kasarskis, A.; Lewis, S.; Matese, J. C.; Richardson, J. E.; Ringwald, M.; Rubin, G. M.; Sherlock, G.; Consortium, G. O., Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000, 25, (1), 25-29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gene Ontology, C.; Aleksander, S. A.; Balhoff, J.; Carbon, S.; Cherry, J. M.; Drabkin, H. J.; Ebert, D.; Feuermann, M.; Gaudet, P.; Harris, N. L.; Hill, D. P.; Lee, R.; Mi, H.; Moxon, S.; Mungall, C. J.; Muruganugan, A.; Mushayahama, T.; Sternberg, P. W.; Thomas, P. D.; Van Auken, K.; Ramsey, J.; Siegele, D. A.; Chisholm, R. L.; Fey, P.; Aspromonte, M. C.; Nugnes, M. V.; Quaglia, F.; Tosatto, S.; Giglio, M.; Nadendla, S.; Antonazzo, G.; Attrill, H.; Dos Santos, G.; Marygold, S.; Strelets, V.; Tabone, C. J.; Thurmond, J.; Zhou, P.; Ahmed, S. H.; Asanitthong, P.; Luna Buitrago, D.; Erdol, M. N.; Gage, M. C.; Ali Kadhum, M.; Li, K. Y. C.; Long, M.; Michalak, A.; Pesala, A.; Pritazahra, A.; Saverimuttu, S. C. C.; Su, R.; Thurlow, K. E.; Lovering, R. C.; Logie, C.; Oliferenko, S.; Blake, J.; Christie, K.; Corbani, L.; Dolan, M. E.; Drabkin, H. J.; Hill, D. P.; Ni, L.; Sitnikov, D.; Smith, C.; Cuzick, A.; Seager, J.; Cooper, L.; Elser, J.; Jaiswal, P.; Gupta, P.; Jaiswal, P.; Naithani, S.; Lera-Ramirez, M.; Rutherford, K.; Wood, V.; De Pons, J. L.; Dwinell, M. R.; Hayman, G. T.; Kaldunski, M. L.; Kwitek, A. E.; Laulederkind, S. J. F.; Tutaj, M. A.; Vedi, M.; Wang, S. J.; D'Eustachio, P.; Aimo, L.; Axelsen, K.; Bridge, A.; Hyka-Nouspikel, N.; Morgat, A.; Aleksander, S. A.; Cherry, J. M.; Engel, S. R.; Karra, K.; Miyasato, S. R.; Nash, R. S.; Skrzypek, M. S.; Weng, S.; Wong, E. D.; Bakker, E.; Berardini, T. Z.; Reiser, L.; Auchincloss, A.; Axelsen, K.; Argoud-Puy, G.; Blatter, M. C.; Boutet, E.; Breuza, L.; Bridge, A.; Casals-Casas, C.; Coudert, E.; Estreicher, A.; Livia Famiglietti, M.; Feuermann, M.; Gos, A.; Gruaz-Gumowski, N.; Hulo, C.; Hyka-Nouspikel, N.; Jungo, F.; Le Mercier, P.; Lieberherr, D.; Masson, P.; Morgat, A.; Pedruzzi, I.; Pourcel, L.; Poux, S.; Rivoire, C.; Sundaram, S.; Bateman, A.; Bowler-Barnett, E.; Bye, A. J. H.; Denny, P.; Ignatchenko, A.; Ishtiaq, R.; Lock, A.; Lussi, Y.; Magrane, M.; Martin, M. J.; Orchard, S.; Raposo, P.; Speretta, E.; Tyagi, N.; Warner, K.; Zaru, R.; Diehl, A. D.; Lee, R.; Chan, J.; Diamantakis, S.; Raciti, D.; Zarowiecki, M.; Fisher, M.; James-Zorn, C.; Ponferrada, V.; Zorn, A.; Ramachandran, S.; Ruzicka, L.; Westerfield, M., The Gene Ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 2023, 224, (1).

- Ionescu, M.; Zaini, P. A.; Baccari, C.; Tran, S.; da Silva, A. M.; Lindow, S. E., Xylella fastidiosa outer membrane vesicles modulate plant colonization by blocking attachment to surfaces. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, (37), E3910-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolka, M. B.; Martins, D.; Winck, F. V.; Santoro, C. E.; Castellari, R. R.; Ferrari, F.; Brum, I. J.; Galembeck, E.; Coletta, H. D.; Machado, M. A.; Marangoni, S.; Novello, J. C., Proteome analysis of the plant pathogen Xylella fastidiosa reveals major cellular and extracellular proteins and a peculiar codon bias distribution. Proteomics 2003, 3, (2), 224-237. [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, R. P.; Martyn, A.; Kopriva, S., Exometabolomic Profiling of Bacterial Strains as Cultivated Using Arabidopsis Root Extract as the Sole Carbon Source. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2018, 31, (8), 803-813.

- Louie, K. B.; Bowen, B. P.; Cheng, X.; Berleman, J. E.; Chakraborty, R.; Deutschbauer, A.; Arkin, A.; Northen, T. R., "Replica-extraction-transfer" nanostructure-initiator mass spectrometry imaging of acoustically printed bacteria. Anal Chem 2013, 85, (22), 10856-62. [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, M. P.; Rashed, A.; Almeida, R. P. P.; Perring, T. M., Vector preference for hosts differing in infection status: sharpshooter movement and Xylella fastidiosa transmission. Ecol Entomol 2011, 36, (5), 654-662. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A. E., The B vitamin nutrition of insects: the contributions of diet, microbiome and horizontally acquired genes. Curr Opin Insect Sci 2017, 23, 65-69. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhi, W.; Qu, H.; Lin, H.; Jiang, Y., Application of alpha-aminoisobutyric acid and beta-aminoisobutyric acid inhibits pericarp browning of harvested longan fruit. Chem Cent J 2015, 9, (1), 54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phinney, B. O., Growth Response of Single-Gene Dwarf Mutants in Maize to Gibberellic Acid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1956, 42, (4), 185-189. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Hershey, D. M.; Wang, L.; Bogdanove, A. J.; Peters, R. J., An ent-kaurene-derived diterpenoid virulence factor from Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola. New Phytologist 2015, 206, (1), 295-302. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergine, M.; Nicolì, F.; Sabella, E.; Aprile, A.; De Bellis, L.; Luvisi, A., Secondary Metabolites in Plant Interaction. Pathogens 2020, 9, (9).

- Novelli, S.; Gismondi, A.; Di Marco, G.; Canuti, L.; Nanni, V.; Canini, A., Plant defense factors involved in Olea europaea resistance against Xylella fastidiosa infection. J Plant Res 2019, 132, (3), 439-455. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, G. J.; Kang, S. M.; Hamayun, M.; Kim, S. K.; Na, C. I.; Shin, D. H.; Lee, I. J., Burkholderia sp KCTC 11096BP as a newly isolated gibberellin producing bacterium. Journal of Microbiology 2009, 47, (2), 167-171. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, J. L.; Araujo, W. L.; Lacava, P. T., The diversity of citrus endophytic bacteria and their interactions with Xylella fastidiosa and host plants. Genetics and Molecular Biology 2016, 39, (4), 476-491. [CrossRef]

- Caserta, R.; Souza-Neto, R. R.; Takita, M. A.; Lindow, S.; Souza, A., Ectopic expression of Xylella fastidiosa rpfF conferring production of diffusible signal factor in transgenic tobacco and citrus alters pathogen behavior and reduces disease severity. Molecular plant-microbe interactions : MPMI 2017.

| Bacteria | Strain | Original Host | Origin | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xylella fastidiosa | Temecula1 Wild Type (WT) |

Vitis vinifera | Temecula, California, EUA | [27,40] |

| ΔrpfF | - | - | [41] | |

| Paraburkholderia phytofirmans | PsJN | Allium cepa | Ontario, Canada | [42,43] |

| compound name | gene id | reciprocal score | e-score reaction-to-gene | database id reaction-to-gene | e-score gene-to-reaction | database id gene-to-reaction | MAGI score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Aminoisobutyric acid | PD0094 | 2.00 | 200.00 | ALANINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | ALANINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 1.58 |

| PD1696 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RXN-16659 | 200.00 | RXN-16659 | 1.58 | |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RXN-16649 | 200.00 | RXN-16649 | 1.58 | ||

| PD1823 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:20249 | 200.00 | RHEA:20249 | 1.58 | |

| PD1864 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:11224 | 200.00 | RHEA:11224 | 1.58 | |

| PD1865 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:23374 | 200.00 | RHEA:23374 | 1.58 | |

| Alanine | PD1864 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:11224 | 200.00 | RHEA:11224 | 6.33 |

| PD1823 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:20249 | 200.00 | RHEA:20249 | 6.33 | |

| PD0094 | 2.00 | 200.00 | ALANINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | ALANINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 | |

| Arginine | PD0116 | 2.00 | 34.19 | ARGININE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 32.31 | ARGININE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 4.01 |

| Asparagine | PD1947 | 2.00 | 200.00 | ASPARAGINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | ASPARAGINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 |

| Aspartate | PD0089 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:12228 | 200.00 | RHEA:12228 | 6.33 |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:11375 | 200.00 | RHEA:11375 | 6.33 | ||

| PD0166 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:22630 | 200.00 | RHEA:22630 | 6.33 | |

| PD0291 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:10932 | 200.00 | RHEA:10932 | 6.33 | |

| PD0868 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:25877 | 200.00 | RHEA:25877 | 6.33 | |

| PD0946 | 2.00 | 200.00 | ASPARTATE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | ASPARTATE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 | |

| PD1273 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:23777 | 200.00 | RHEA:23777 | 6.33 | |

| PD1274 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:20015 | 200.00 | RHEA:20015 | 6.33 | |

| PD1627 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:15753 | 200.00 | RHEA:15753 | 6.33 | |

| Biotin | PD0043 | 2.00 | 140.61 | 2.8.1.6-RXN | 145.10 | 2.8.1.6-RXN | 5.80 |

| PD1071 | 2.00 | 58.42 | RHEA:31118 | 62.94 | RHEA:31118 | 4.66 | |

| 2.00 | 58.42 | BIOTINLIG-RXN | 62.94 | BIOTINLIG-RXN | 4.66 | ||

| PD1494 | 2.00 | 167.61 | DETHIOBIOTIN-SYN-RXN | 165.73 | DETHIOBIOTIN-SYN-RXN | 1.51 | |

| Cysteine | PD0655 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:13285 | 200.00 | RHEA:13285 | 6.33 |

| PD1812 | 2.00 | 156.15 | RHEA:20400 | 154.24 | RHEA:20400 | 5.93 | |

| PD1841 | 2.00 | 143.27 | ACSERLY-RXN | 137.99 | ACSERLY-RXN | 5.77 | |

| PD0118 | 2.00 | 134.13 | RHEA:19398 | 132.24 | RHEA:19398 | 5.71 | |

| 2.00 | 134.13 | RHEA:25159 | 132.24 | RHEA:25159 | 5.71 | ||

| PD0690 | 2.00 | 133.98 | RXN0-308 | 132.09 | RXN0-308 | 5.71 | |

| PD0287 | 2.00 | 126.84 | CYSTEINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 124.08 | CYSTEINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 5.62 | |

| Gibberellic acid | PD0286 | 0.01 | 0.89 | RHEA:36115 | 7.41 | RHEA:25891 | 0.43 |

| PD0716 | 0.01 | 0.54 | RHEA:36115 | 159.33 | RHEA:13804 | 0.38 | |

| Nicotinic acid | PD0393 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:36166 | 200.00 | RHEA:36166 | 6.33 |

| PD1310 | 2.00 | 42.72 | RHEA:14545 | 40.84 | RHEA:14545 | 4.26 | |

| Glutamic acid | PD0650 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:17130 | 200.00 | RHEA:17130 | 6.33 |

| PD0654 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:18052 | 200.00 | RHEA:18052 | 6.33 | |

| PD0399 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:18633 | 200.00 | RHEA:18633 | 6.33 | |

| PD2062 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:11613 | 200.00 | RHEA:11613 | 6.33 | |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:15504 | 200.00 | RHEA:15504 | 6.33 | ||

| PD1358 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:16574 | 200.00 | RHEA:16574 | 6.33 | |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:14329 | 200.00 | RHEA:14329 | 6.33 | ||

| PD1266 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:23746 | 200.00 | RHEA:23746 | 6.33 | |

| PD0089 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:12228 | 200.00 | RHEA:12228 | 6.33 | |

| PD0839 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:24385 | 200.00 | RHEA:24385 | 6.33 | |

| PD1447 | 2.00 | 200.00 | GMP-SYN-GLUT-RXN | 200.00 | GMP-SYN-GLUT-RXN | 6.33 | |

| PD1848 | 2.00 | 200.00 | GLURS-RXN | 200.00 | GLURS-RXN | 6.33 | |

| PD1026 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:45804 | 200.00 | RHEA:45804 | 6.33 | |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:16170 | 200.00 | RHEA:16170 | 6.33 | ||

| PD0851 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:14908 | 200.00 | RHEA:14908 | 6.33 | |

| PD0785 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:15136 | 200.00 | RHEA:15136 | 6.33 | |

| PD2063 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:12131 | 200.00 | RHEA:12131 | 6.33 | |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:32192 | 200.00 | RHEA:32192 | 6.33 | ||

| 2.00 | 200.00 | GLUTAMATE-SYNTHASE-FERREDOXIN-RXN | 200.00 | GLUTAMATE-SYNTHASE-FERREDOXIN-RXN | 6.33 | ||

| PD0398 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:18633 | 200.00 | RHEA:18633 | 6.33 | |

| PD0170 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:21735 | 200.00 | RHEA:21735 | 6.33 | |

| PD0296 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:14879 | 200.00 | RHEA:14879 | 6.33 | |

| PD0541 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:15890 | 200.00 | RHEA:15890 | 6.33 | |

| PD0110 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:13239 | 200.00 | RHEA:13239 | 6.33 | |

| PD0655 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:13285 | 200.00 | RHEA:13285 | 6.33 | |

| Glutamine | PD1447 | 2.00 | 200.00 | GMP-SYN-GLUT-RXN | 200.00 | GMP-SYN-GLUT-RXN | 6.33 |

| PD0584 | 2.00 | 200.00 | GLUTAMINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | GLUTAMINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 | |

| PD2063 | 2.00 | 200.00 | GLUTAMATE-SYNTHASE-FERREDOXIN-RXN | 200.00 | GLUTAMATE-SYNTHASE-FERREDOXIN-RXN | 6.33 | |

| Glycine | PD1750 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:15482 | 200.00 | RHEA:15482 | 6.33 |

| PD0620 | 2.00 | 200.00 | GCVMULTI-RXN | 200.00 | GCVMULTI-RXN | 6.33 | |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | GCVP-RXN | 200.00 | GCVP-RXN | 6.33 | ||

| PD1810 | 2.00 | 200.00 | GCVMULTI-RXN | 200.00 | GCVMULTI-RXN | 6.33 | |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | GCVP-RXN | 200.00 | GCVP-RXN | 6.33 | ||

| PD0827 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:17453 | 200.00 | RHEA:17453 | 6.33 | |

| PD0704 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:19938 | 200.00 | RHEA:19938 | 6.33 | |

| PD0844 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:13557 | 200.00 | RHEA:13557 | 6.33 | |

| PD0773 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RXN0-7068 | 200.00 | RXN0-7068 | 6.33 | |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RXN0-7082 | 200.00 | RXN0-7082 | 6.33 | ||

| PD0841 | 2.00 | 170.04 | GLYCINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 168.01 | GLYCINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.06 | |

| PD0840 | 2.00 | 164.75 | GLYCINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 162.87 | GLYCINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.02 | |

| Histidine | PD1267 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:20641 | 200.00 | RHEA:20641 | 6.33 |

| PD1772 | 2.00 | 60.65 | RHEA:20641 | 58.79 | RHEA:20641 | 4.66 | |

| PD1270 | 2.00 | 26.76 | HISTIDINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 24.84 | HISTIDINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 3.76 | |

| Isoleucine | PD1437 | 2.00 | 200.00 | ISOLEUCINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | ISOLEUCINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 |

| Leucine | PD1230 | 2.00 | 200.00 | LEUCINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | LEUCINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 |

| Lysine | PD0404 | 2.00 | 200.00 | LYSINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | LYSINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 |

| PD1514 | 2.00 | 69.38 | RXN-1961 | 78.45 | RXN-1961 | 4.86 | |

| PD2000 | 2.00 | 55.90 | RHEA:15944 | 53.31 | RHEA:15944 | 1.14 | |

| Methionine | PD1590 | 2.00 | 200.00 | METHIONINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | METHIONINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RXN-16165 | 200.00 | RXN-16165 | 6.33 | ||

| Phenylalanine | PD1911 | 2.00 | 200.00 | PHENYLALANINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | PHENYLALANINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 |

| PD0665 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RXN-15898 | 200.00 | RXN-15898 | 1.58 | |

| Proline | PD1635 | 2.00 | 200.00 | PROLINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | PROLINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 |

| Serine | PD0612 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:26437 | 200.00 | RHEA:26437 | 6.33 |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:10532 | 200.00 | RHEA:10532 | 6.33 | ||

| PD1750 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:15482 | 200.00 | RHEA:15482 | 6.33 | |

| PD1318 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RXN0-2161 | 200.00 | RXN0-2161 | 6.33 | |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | SERINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | SERINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 | ||

| PD0613 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:26437 | 200.00 | RHEA:26437 | 6.33 | |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:10532 | 200.00 | RHEA:10532 | 6.33 | ||

| Threonine | PD1916 | 2.00 | 200.00 | THREONINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | THREONINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 |

| Tryptophan | PD0612 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:10532 | 200.00 | RHEA:10532 | 6.33 |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:26437 | 200.00 | RHEA:26437 | 6.33 | ||

| PD0613 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:10532 | 200.00 | RHEA:10532 | 6.33 | |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:26437 | 200.00 | RHEA:26437 | 6.33 | ||

| PD1650 | 2.00 | 47.82 | TRYPTOPHAN--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 45.82 | TRYPTOPHAN--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 4.38 | |

| Tyrosine | PD0665 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RXN-15898 | 200.00 | RXN-15898 | 6.33 |

| PD0132 | 2.00 | 33.23 | TYROSINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 31.35 | TYROSINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 3.98 | |

| Valine | PD0102 | 2.00 | 200.00 | VALINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 200.00 | VALINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.33 |

| compound name | gene id | reciprocal score | e-score reaction-to-gene | database id reaction-to-gene | e-score gene-to-reaction | database id gene-to-reaction | MAGI score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cysteine | Bphyt_3930 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:13285 | 200.00 | RHEA:13285 | 6.33 |

| Bphyt_4072 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RXN-17172 | 200.00 | RXN-17172 | 6.33 | |

| Bphyt_2579 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RXN-15881 | 200.00 | RXN-15881 | 6.33 | |

| 2.00 | 200.00 | RXN0-308 | 200.00 | RXN0-308 | 6.33 | ||

| Bphyt_3068 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:28784 | 200.00 | RHEA:28784 | 6.33 | |

| Bphyt_0110 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:13285 | 200.00 | RHEA:13285 | 6.33 | |

| Bphyt_3953 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:13285 | 200.00 | RHEA:13285 | 6.33 | |

| Bphyt_2579 | 2.00 | 177.70 | RXN-14385 | 175.79 | RXN-14385 | 6.13 | |

| Bphyt_2510 | 2.00 | 175.50 | CYSTEINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 171.77 | CYSTEINE--TRNA-LIGASE-RXN | 6.10 | |

| Gibberellic acid | Bphyt_5231 | 0.01 | 18.39 | RXN-14318 | 39.82 | RXN-16827 | 0.23 |

| 0.01 | 18.39 | RXN-14317 | 39.82 | RXN-16827 | 0.23 | ||

| 0.01 | 18.39 | RXN-7617 | 39.82 | RXN-16827 | 0.23 | ||

| Nicotinamide | Bphyt_5413 | 2.00 | 200.00 | RHEA:16150 | 200.00 | RHEA:16150 | 6.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).