Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

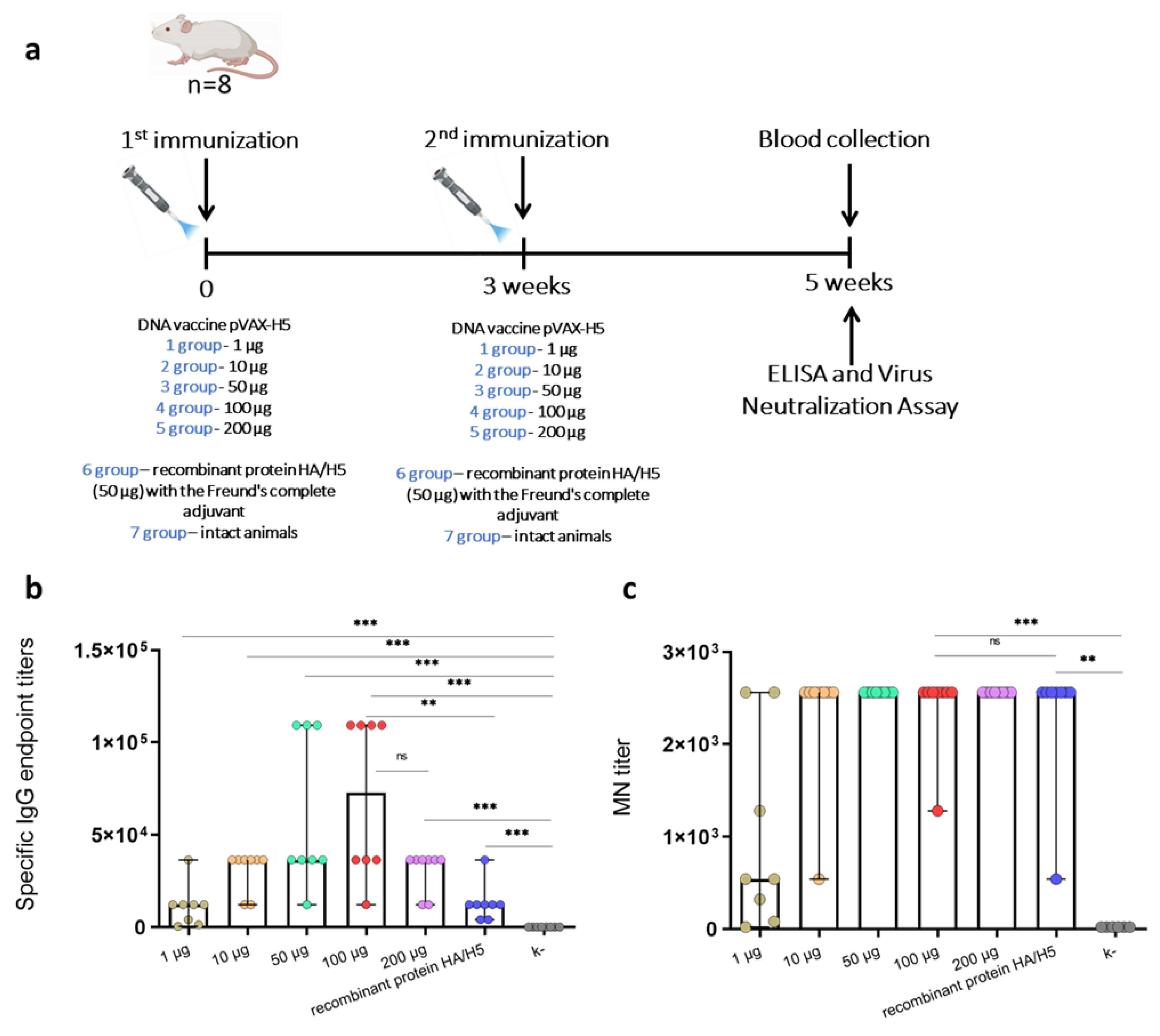

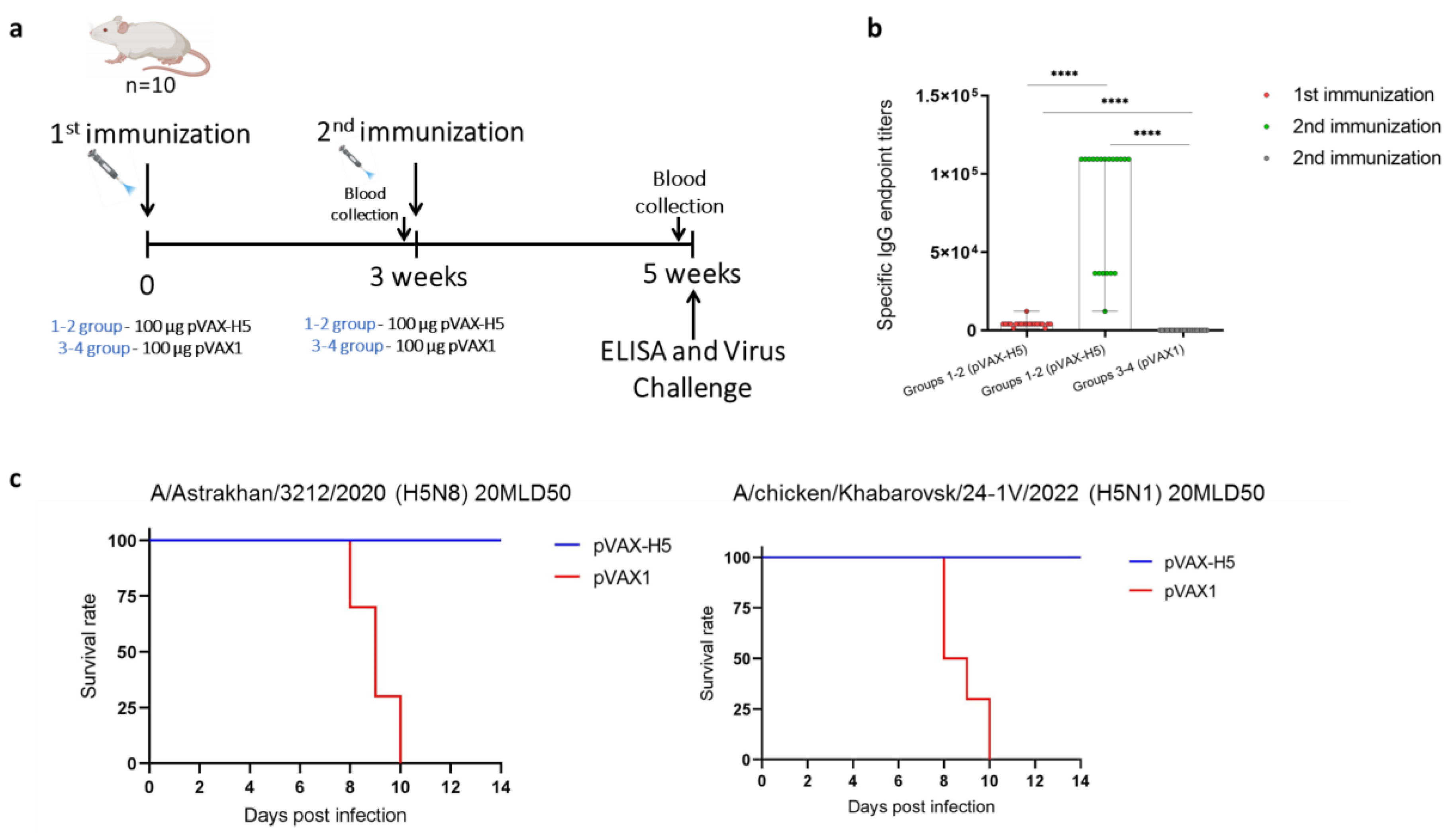

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5 clade 2.3.4.4b viruses are widespread in wild and domestic birds, causing severe economic damage to the global poultry industry. Moreover, viruses of this clade can adapt to mammals, posing a potential pandemic threat. With the constant evolution and change of dominant strains of H5 clade 2.3.4.4b, it is important to investigate the cross-reactivity of available and developing vaccine preparations. In this study, the immuno-genicity of the previously developed DNA vaccine encoding a modified hemagglutinin of influ-enza A/turkey/Stavropol/320-01/2020 (H5N8) virus, administered by jet injection at doses of 1, 10, 50, 100 and 200 μg, was investigated. The highest titer of specific to recombinant hemagglutinin antibodies was detected in the group of animals injected with 100 µg of DNA vaccine. The cross-reactivity study of sera of animals immunized with 100 µg of DNA vaccine in microneutralization assay against strains A/chicken/Astrakhan/321-05/2020 (H5N8), A/chicken/Komi/24-4V/2023 (H5N1), A/chicken/Khabarovsk/24-1V/2022 (H5N1) and A/chicken/Voronezh/193-1V/2024 (H5N1) showed the formation of cross-neutralizing antibodies. Moreover, the study of protective properties showed that the DNA vaccine prevented morbidity and mortality of animals after infection with both homologous strain A/Astrakhan/3212/2020 (H5N8) and heterologous strain A/chicken/Khabarovsk/24-1V/2022 (H5N1).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains of Viruses, Bacteria, Cell Cultures

2.2. Development of DNA Vaccine pVAX-H5

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.5. HI and Microneutralization Assays

2.6. Challenge Studies

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fukuyama, S.; Kawaoka, Y. The pathogenesis of influenza virus infections: the contributions of virus and host factors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011, 23, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, Á.; Colvin, C.L.; McLaughlin, E. What can we learn from historical pandemics? A systematic review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 2024, 342, 116534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zeng, X.; Cui, P.; Yan, C.; Chen, H. Alarming situation of emerging H5 and H7 avian influenza and effective control strategies. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.; Mini, M.; Zaawari, A.; Banerjee, A.; Bage, R. N.; Jha, T. From avian to human: understanding the cross-species transmission and the global spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza. The Evidence 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, M.P.G.; Barton Behravesh, C.; Cunningham, A.A.; Adisasmito, W.B.; Almuhairi, S.; Bilivogui, P.; Bukachi, S.A.; Casas, N.; Cediel Becerra, N.; Charron, D.F.; et al. The panzootic spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 sublineage 2.3.4.4 b: a critical appraisal of One Health preparedness and prevention. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramuwidyatama, M.G.; Indrawan, D.; Boeters, M.; Poetri, O.N.; Saatkamp, H.W.; Hogeveen, H. Economic impact of highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreaks in Western Java smallholder broiler farms. Prev Vet Med. 2023, 212, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhirnov, O.P.; Lvov, D.K. Avian flu: «for whom the bell tolls»? Vopr Virusol. 2024, 69, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiba, S.; Kiso, M.; Yamada, S.; Someya, K.; Onodera, Y.; Yamaguchi, A.; Matsunaga, S.; Jounai, N.; Yamayoshi, S.; Takeshita, F.; Kawaoka, Y. Protective effects of an mRNA vaccine candidate encoding H5HA clade 2.3.4.4b against the newly emerged dairy cattle H5N1 virus. eBioMedicine 2024, 109, 105408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Isolation of avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses from humans--Hong Kong, May-December 1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997, 46, 1204–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Hatta, M.; Gao, P.; Halfmann, P.; Kawaoka, Y. Molecular basis for high virulence of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses. Science 2001, 293, 1840–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focosi, D.; Maggi, F. Avian Influenza Virus A(H5Nx) and Prepandemic Candidate Vaccines: State of the Art. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for avian influenza A(H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2024, 27 September 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/cumulative-number-of-confirmed-human-cases-for-avian-influenza-a (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Xie, R.; Edwards, K.M.; Wille, M.; Wei, X.; Wong, S.S.; Zanin, M.; El-Shesheny, R.; Ducatez, M.; Poon, L.L.M.; Kayali, G.; Webby, R.J.; Dhanasekaran, V. The episodic resurgence of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5 virus. Nature 2023, 622, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Assessment of risk associated with recent influenza A(H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b viruses 21 December 2022. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/influenza/avian-and-other-zoonotic-influenza/h5-risk-assessment-dec-2022.pdf?sfvrsn = a496333a_1&download = true (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Pyankova, O.G.; Susloparov, I.M.; Moiseeva, A.A.; Kolosova, N.P.; Onkhonova, G.S.; Danilenko, A.V.; Vakalova, E.V.; Shendo, G.L.; Nekeshina, N.N.; Noskova, L.N.; et al. Isolation of clade 2.3.4.4b A(H5N8), a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus, from a worker during an outbreak on a poultry farm, Russia, December 2020. Euro Surveill. 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisfeld, A.J.; Biswas, A.; Guan, L.; Gu, C.; Maemura, T.; Trifkovic, S.; Wang, T.; Babujee, L.; Dahn, R.; Halfmann, P. J.; et al. Pathogenicity and transmissibility of bovine H5N1 influenza virus. Nature 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrough, E.R.; Magstadt, D.R.; Petersen, B.; Timmermans, S.J.; Gauger, P.C.; Zhang, J.; Siepker, C.; Mainenti, M.; Li, G.; Thompson, A.C.; et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4 b virus infection in domestic dairy cattle and cats, United States, 2024. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024, 30, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Sage, V.; Werner, B.D.; Merrbach, G.A.; Petnuch, S.E.; O'Connell, A.K.; Simmons, H.C.; McCarthy, K.R.; Reed, D.S.; Moncla, L.H.; Bhavsar, D.; et al. Pre-existing H1N1 immunity reduces severe disease with bovine H5N1 influenza virus. bioRxiv, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, A.; Alfaro-Núñez, A.; de Mora, D.; Armas, R.; Olmedo, M.; Garcés, J.; Garcia-Bereguiain, M. A. First case of human infection with highly pathogenic H5 avian influenza a virus in South America: a new zoonotic pandemic threat for 2023? J Travel Med. 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulit-Penaloza, J. A.; Brock, N.; Belser, J. A.; Sun, X.; Pappas, C.; Kieran, T. J.; Basu Thakur, P.; Zeng, H.; Cui, D.; Frederick, J.; et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus of clade 2.3.4.4 b isolated from a human case in Chile causes fatal disease and transmits between co-housed ferrets. Emerg Microbes Infect 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwhab, E.M.; Beer, M. Panzootic HPAIV H5 and risks to novel mammalian hosts. npj Viruses 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Xiao, H.; Martin, S.R.; Coombs, P.J.; Liu, J.; Collins, P.J.; Vachieri, S.G.; Walker, P.A.; Lin, Y.P.; McCauley, J.W.; et al. Enhanced human receptor binding by H5 haemagglutinins. Virology 2014, 456-457, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, A.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; Richard, M. Cross-Reactivity Conferred by Homologous and Heterologous Prime-Boost A/H5 Influenza Vaccination Strategies in Humans: A Literature Review. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Wu, Q.; Rezaei, N.; Jiang, S.; Pan, C. Potential cross-species transmission of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5 subtype (HPAI H5) viruses to humans calls for the development of H5-specific and universal influenza vaccines. Cell Discov. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuyama, W.; Reynolds, P.; Haddock, E.; Meade-White, K.; Quynh Le, M.; Kawaoka, Y.; Feldmann, H.; Marzi, A. A single dose of a vesicular stomatitis virus-based influenza vaccine confers rapid protection against H5 viruses from different clades. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinova, V.R.; Rudometov, A.P.; Karpenko, L.I.; Ilyichev, A.A. mRNA vaccine platform: mRNA production and delivery. Russ J Bioorg Chem. 2023, 49, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagigi, A.; Douradinha, B. Have mRNA vaccines sentenced DNA vaccines to death? Expert Rev. Vaccines 2023, 22, 1154–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, R.A.; Fuhr, R.; Smolenov, I.; Mick Ribeiro, A.; Panther, L.; Watson, M.; Senn, J.J.; Smith, M.; Almarsson, Ӧ.; Pujar, H.S. mRNA vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 influenza viruses of pandemic potential are immunogenic and well tolerated in healthy adults in phase 1 randomized clinical trials. Vaccine 2019, 37(25), 3326–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Parkhouse, K.; Kirkpatrick, E.; McMahon, M.; Zost, S.J.; Mui, B.L.; Tam, Y.K.; Karikó, K.; Barbosa, C.J.; Madden, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Nucleoside-modified mRNA immunization elicits influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies. Nat Commun. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, E.; Pardi, N.; Parkhouse, K.; Mui, B.L.; Tam, Y.K.; Weissman, D.; Hensley, S.E. Nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccination partially overcomes maternal antibody inhibition of de novo immune responses in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo, C.P.; Bolton, M.J.; Le Sage, V.; Ye, N.; Furey, C.; Muramatsu, H.; Alameh, M.G.; Pardi, N.; Drapeau, E.M.; Parkhouse, K.; et al. A multivalent nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccine against all known influenza virus subtypes. Science 2022, 378, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zeng, X.; Ren, W.; Liao, P.; Zhu, B. Protective efficacy of a universal influenza mRNA vaccine against the challenge of H1 and H5 influenza A viruses in mice. mLife 2023, 2, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooij, P.; Grødeland, G.; Koopman, G.; Andersen, T.K.; Mortier, D.; Nieuwenhuis, I.G.; Verschoor, E.J.; Fagrouch, Z.; Bogers, W.M.; Bogen, B. Needle-free delivery of DNA: Targeting of hemagglutinin to MHC class II molecules protects rhesus macaques against H1N1 influenza. Vaccine 2019, 37, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Yu, L.; Teng, Q.; Li, X.; Jin, Z.; Qu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhao, K. Enhance immune response to H9 AIV DNA vaccine based on polygene expression and DGL nanoparticle encapsulation. Poult Sci. 2023, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Lan, H.; Teng, Q.; Li, X.; Jin, Z.; Qu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Kang, H.; Yin, T.H.; Li, Z.; Zhao, K. An immune-enhanced multivalent DNA nanovaccine to prevent H7 and H9 avian influenza virus in mice. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023, 251, 126286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, J.; Ingrao, F.; Rauw, F.; Lambrecht, B. Protection conferred by an H5 DNA vaccine against highly pathogenic avian influenza in chickens: The effect of vaccination schedules. Vaccine 2024, 42, 1487–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eman, M.E.; Saad, M.A.; Maha, A.G.; Zaki, F.F.; Soliman, Y.A. A novel DNA vaccine coding for H5 and N1 genes of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 subtype. IJVSBT 2020, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mady, W.H.M.; Liu, B.; Huang, D.; Arafa, A.; Hassan, M.K.; Aly, M.M.; Chen, P.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, H. Construction and protective efficacy of Egy-H5 DNA Vaccine from local Egyptian STRAIN H5N1 using codon optimized HA gene. Hosts and Viruses 2017, 4, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Patel, A.; Tursi, N.J.; Zhu, X.; Muthumani, K.; Kulp, D.W.; Weiner, D.B. Harnessing Recent Advances in Synthetic DNA and Electroporation Technologies for Rapid Vaccine Development Against COVID-19 and Other Emerging Infectious Diseases. Front Med Technol. 2020, 2, 571030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisakov, D.N.; Kisakova, L.A.; Borgoyakova, M.B.; Starostina, E.V.; Taranov, O.S.; Ivleva, E.K.; Pyankov, O.V.; Zaykovskaya, A.V.; Shcherbakov, D.N.; Rudometov, A.P.; et al. Optimization of In Vivo Electroporation Conditions and Delivery of DNA Vaccine Encoding SARS-CoV-2 RBD Using the Determined Protocol. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisakov, D.N.; Belyakov, I.M.; Kisakova, L.A.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Tigeeva, E.V.; Karpenko, L.I. The use of electroporation to deliver DNA-based vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2023, 23, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma-Feliciano, C.; Chapman, R.; Hooper, J.W.; Elma, K.; Zehrung, D.; Brennan, M.B.; Spiegel, E.K. Improved DNA Vaccine Delivery with Needle-Free Injection Systems. Vaccines 2023, 11, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslow, J.N.; Kwon, I.; Kudchodkar, S.B.; Kane, D.; Tadesse, A.; Lee, H.; Park, Y.K.; Muthumani, K.; Roberts, C.C. DNA Vaccines for Epidemic Preparedness: SARS-CoV-2 and Beyond. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupferschmidt, K. Bird flu spread between mink is a ‘warning bell’. Science 2023, 379, 316–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidik, S.M. Bird flu outbreak in mink sparks concern about spread in people. Nature 2023, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agüero, M.; Monne, I.; Sánchez, A.; Zecchin, B.; Fusaro, A.; Ruano, M.J.; Del Valle Arrojo, M.; Fernández-Antonio, R.; Souto, A.M.; Tordable, P.; et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infection in farmed minks, Spain, October 2022. Euro Surveill. 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijks, J.M.; Hesselink, H.; Lollinga, P.; Wesselman, R.; Prins, P.; Weesendorp, E.; Engelsma, M.; Heutink, R.; Harders, F.; Kik, M.; et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus in Wild Red Foxes, the Netherlands, 2021. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021, 27, 2960–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puryear, W.; Sawatzki, K.; Hill, N.; Foss, A.; Stone, J.J.; Doughty, L.; Walk, D.; Gilbert, K.; Murray, M.; Cox, E.; et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Outbreak in New England Seals, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023, 29, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchenko, V.Y.; Panova, A.S.; Kolosova, N.P.; Gudymo, A.S.; Svyatchenko, S.V.; Danilenko, A.V.; Vasiltsova, N.N.; Egorova, M.L.; Onkhonova, G.S.; Zhestkov, P.D.; et al. Characterization of H5N1 avian influenza virus isolated from bird in Russia with the E627K mutation in the PB2 protein. Sci Rep. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurana, S.; King, L.R.; Manischewitz, J.; Posadas, O.; Mishra, A.K.; Liu, D.; Beigel, J.H.; Rappuoli, R.; Tsang, J.S.; Golding, H. Licensed H5N1 vaccines generate cross-neutralizing antibodies against highly pathogenic H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b influenza virus. Nat Med. 2024, 30, 2771–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinova, V.R.; Rudometov, A.P.; Rudometova, N.B.; Kisakov, D.N.; Borgoyakova, M.B.; Kisakova, L.A.; Starostina, E.V.; Fando, A.A.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Tigeeva, E.V.; et al. DNA Vaccine Encoding a Modified Hemagglutinin Trimer of Avian Influenza A Virus H5N8 Protects Mice from Viral Challenge. Vaccines 2024, 12, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudometova, N.B.; Fando, A.A.; Kisakova, L.A.; Kisakov, D.N.; Borgoyakova, M.B.; Litvinova, V.R.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Tigeeva, E.V.; Vahitov, D.I.; Sharabrin, S.V.; et al. Immunogenic and Protective Properties of Recombinant Hemagglutinin of Influenza A (H5N8) Virus. Vaccines 2024, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultankulova, K.T.; Argimbayeva, T.U.; Aubakir, N.A.; Bopi, A.; Omarova, Z.D.; Melisbek, A.M.; Karamendin, K.; Kydyrmanov, A.; Chervyakova, O.V.; Kerimbayev, A.A.; et al. Reassortants of the Highly Pathogenic Influenza Virus A/H5N1 Causing Mass Swan Mortality in Kazakhstan from 2023 to 2024. Animals 2024, 14, 3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudymo, A.; Onkhonova, G.; Danilenko, A.; Susloparov, I.; Danilchenko, N.; Kosenko, M.; Moiseeva, A.; Kolosova, N.; Svyatchenko, S.; Marchenko, V.; et al. Quantitative Assessment of Airborne Transmission of Human and Animal Influenza Viruses in the Ferret Model. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, N.; Esaki, M.; Kojima, I.; Khalil, A.M.; Osuga, S.; Shahein, M.A.; Okuya, K.; Ozawa, M.; Alhatlani, B.Y. Phylogenetic Characterization of Novel Reassortant 2.3.4.4b H5N8 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses Isolated from Domestic Ducks in Egypt During the Winter Season 2021–2022. Viruses 2024, 16, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Lim, J.M.; Yu, B.; Song, S.; Neeli, P.; Sobhani, N.; Pavithra, K.; Bonam, S.R.; Kurapati, R.; Zheng, J.; Chai, D. The next-generation DNA vaccine platforms and delivery systems: advances, challenges and prospects. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1332939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milder, F.J.; Jongeneelen, M.; Ritschel, T.; Bouchier, P.; Bisschop, I.J.M.; de Man, M.; Veldman, D.; Le, L.; Kaufmann, B.; Bakkers, M.J.G.; et al. Universal stabilization of the influenza hemagglutinin by structure-based redesign of the pH switch regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juraszek, J.; Milder, F.J.; Yu, X.; Blokland, S.; van Overveld, D.; Abeywickrema, P.; Tamara, S.; Sharma, S.; Rutten, L.; Bakkers, M.J.G.; Langedijk, J.P.M. Engineering a cleaved, prefusion-stabilized influenza B virus hemagglutinin by identification and locking of all six pH switches. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Recommendations for influenza vaccine composition. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-influenza-programme/vaccines/who-recommendations (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Marchenko, V.Yu.; Svyatchenko, S.V.; Onkhonova, G.S.; Goncharova, N.I.; Ryzhikov, A.B.; Maksyutov, R.A.; Gavrilova, E.V. Review on the Epizootiological Situation on Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza around the World and in Russia in 2022. Problems of Particularly Dangerous Infections, 2023; 1, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Hu, J. DNA Vaccines: Their Formulations, Engineering and Delivery. Vaccines 2024, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werninghaus, I.C.; Hinke, D.M.; Fossum, E.; Bogen, B.; Braathen, R. Neuraminidase delivered as an APC-targeted DNA vaccine induces protective antibodies against influenza. Mol Ther. 2023, 31, 2188–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Liao, R.; He, D.; Xu, L.; Chen, T.; Xiao, Q.; Luo, M.; Chen, Y.; et al. Airway applied IVT mRNA vaccine needs specific sequence design and high standard purification that removes devastating dsRNA contaminant. bioRxiv, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabrin, S.V.; Bondar, A.A.; Starostina, E.V; Kisakov, D.N.; Kisakova, L.A.; Zadorozhny, A.M.; Rudometov, A.P.; Ilyichev, A.A.; Karpenko, L.I. Removal of Double-Stranded RNA Contaminants During Template-Directed Synthesis of mRNA. Bull Exp Biol Med 2024, 176, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikó, K.; Muramatsu, H.; Ludwig, J.; Weissman, D. Generating the optimal mRNA for therapy: HPLC purification eliminates immune activation and improves translation of nucleoside-modified, protein-encoding mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portal, M.M.; Pavet, V.; Erb, C.; Gronemeyer, H. Human cells contain natural double-stranded RNAs with potential regulatory functions. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015, 22, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombetta, C.M.; Perini, D.; Mather, S.; Temperton, N.; Montomoli, E. Overview of Serological Techniques for Influenza Vaccine Evaluation: Past, Present and Future. Vaccines 2014, 2, 707–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, G.; Medini, D.; Borgogni, E.; Zedda, L.; Bardelli, M.; Malzone, C.; Nuti, S.; Tavarini, S.; Sammicheli, C.; Hilbert, A.K.; et al. Adjuvanted H5N1 vaccine induces early CD4+ T cell response that predicts long-term persistence of protective antibody levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009, 106, 3877–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Velden, M.V.; Aichinger, G.; Pollabauer, E.M.; Low-Baselli, A.; Fritsch, S.; Benamara, K.; Kistner, O.; Muller, M.; Zeitlinger, M.; Kollaritsch, H.; et al. Cell culture (Vero cell) derived whole-virus non-adjuvanted H5N1 influenza vaccine induces long-lasting cross-reactive memory immune response: Homologous or heterologous booster response following two dose or single dose priming. Vaccine 2012, 30, 6127–6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furey, C.; Scher, G.; Ye, N.; Kercher, L.; DeBeauchamp, J.; Crumpton, J.C.; Jeevan, T.; Patton, C.; Franks, J.; Rubrum, A.; et al. Development of a nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccine against clade 2.3.4.4b H5 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Nat Commun. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, S.; Kiso, M.; Yamada, S.; Someya, K.; Onodera, Y.; Yamaguchi, A.; Matsunaga, S.; Uraki, R.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Yamayoshi, S.; Takeshita, F.; Kawaoka, Y. An mRNA vaccine candidate encoding H5HA clade 2.3.4.4b protects mice from clade 2.3.2.1a virus infection. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Vervaeke, P.; Gao, Y.; Opsomer, L.; Sun, Q.; Snoeck, J.; Devriendt, B.; Zhong, Z.; Sanders, N. N. Immunogenicity and biodistribution of lipid nanoparticle formulated self-amplifying mRNA vaccines against H5 avian influenza. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Viruses | Ferret reference serum | |||||

| A/gyrfalcon/Washington/41088-6/2014 | A/Astrakhan/3212/2020 | A/chicken/Nghe An/27VTC/2018 | A/dalmatian pelican/Astrakhan/213-2V/2022 | A/chicken/Khabarovsk/24-1V/2022 | ||

| Reference antigens | Subtype | Subclade | ||||

| 2.3.4.4c | 2.3.4.4b | 2.3.4.4f | 2.3.4.4b | 2.3.4.4b | ||

| A/gyrfalcon/Washington/ /41088-6/2014 |

H5N8 | 320 | 640 | 640 | 640 | 320 |

| A/Astrakhan/3212/2020 | H5N8 | 80 | 160 | 80 | 80 | 160 |

| A/chicken/NgheAn /27VTC/2018 |

H5N6 | 320 | 640 | 640 | 640 | 320 |

| A/dalmatian pelican/Astrakhan/ 213-2V/2022 |

H5N1 | 160 | 320 | 320 | 320 | 320 |

| A/chicken/Khabarovsk/24-1V/2022 | H5N1 | 20 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 320 |

| A/chicken/Astrakhan/ 32105/2020 | H5N8 | 80 | 160 | 80 | 80 | 160 |

| A/chicken/Voronezh/193-1V/2024 | H5N1 | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 | 160 |

| A/turkey/Stavropol/320-01/2020 | H5N8 | 80 | 80 | <20 | 40 | 80 |

| A/chicken/Komi/24-4V/2023 | H5N1 | 320 | 320 | <20 | 160 | 160 |

| Serum code | A/chicken/Astrakhan/321-05/2020 (H5N8) | A/chicken/Komi/24-4V/2023 (H5N1) | A/chicken/Khabarovsk/24-1V/2022 (H5N1) | A/chicken/Voronezh/193-1V/2024 (H5N1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1280 | 640 | 40 | 640 |

| 2 | 1280 | 160 | 40 | 320 |

| 3 | 640 | 320 | 80 | 640 |

| 4 | 2560 | 640 | 40 | 1280 |

| 5 | 2560 | 640 | 40 | 640 |

| 6 | 1280 | 320 | 40 | 640 |

| 7 | 640 | 320 | 80 | 640 |

| 8 | 640 | 320 | 80 | 1280 |

| 9 | 1280 | 320 | 80 | 640 |

| 10 | 1280 | 640 | 40 | 640 |

| Control (+)* | 2560 | 1280 | 640 | 2560 |

| Control (-)** | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 |

| HA | 10 | 44 | 88 | 99 | 104 | 152 | 153 | 170 | 338 | 462 | 463 | 503 | 519 | 548 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/turkey/Stavropol/320-01/2020 (H5N8) | I | H | R | A | D | P | Y | N | L | N | L | D | S | M |

| A/chicken/Astrakhan/321-05/2020 (H5N8) | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| A/Astrakhan/3212/2020 (H5N8) | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| A/chicken/Khabarovsk/24-1V/2022 (H5N1) | T | Q | . | N | . | . | . | D | I | K | . | Y | . | . |

| A/chicken/Komi/24-4V/2023 (H5N1) | . | . | E | . | G | . | H | . | . | . | . | . | . | I |

| A/chicken/Voronezh/193-1V/2024 (H5N1) | . | . | . | D | . | S | . | . | . | . | I | . | N | I |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).